Summary

Myogenic cells have the ability to adopt two divergent fates upon exit from the cell cycle: differentiation or self-renewal. The Notch signaling pathway is a well-known negative regulator of myogenic differentiation. Using mouse primary myoblasts cultured in vitro or C2C12 myogenic cells, we find that Notch activity is essential for maintaining the expression of Pax7, a transcription factor associated with the self-renewal lineage, in quiescent undifferentiated myoblasts after they exit the cell cycle. Stimulation of the Notch pathway by expression of a constitutively active Notch 1 or co-culture of myogenic cells with Delta like-1 (Dll1)-transfected CHO cells increases the level of Pax7. Dll1, a ligand for Notch receptor, is shed by ADAM metalloproteases in a pool of Pax7-positive C2C12 reserve cells, but it remains intact in differentiated myotubes. Dll1 shedding changes the receptor/ligand ratio and modulates the level of Notch signaling. Inhibition of Dll1 cleavage by a soluble, dominant-negative mutant form of ADAM12 leads to elevation of Notch signaling, inhibition of differentiation, and expansion of the pool of self-renewing Pax7-positive/MyoD-negative cells. These results suggest that ADAM-mediated shedding of Dll1 in a subset of cells during myogenic differentiation in vitro contributes to down-regulation of Notch signaling in neighboring cells and facilitates their progression into differentiation. We propose that the proteolytic processing of Dll1 helps achieve an asymmetry in Notch signaling in initially equivalent myogenic cells and helps sustain the balance between differentiation and self-renewal.

Keywords: proteolytic processing, Notch, Delta, disintegrin, metalloprotease, γ-secretase, Pax7, stem cells

Introduction

Skeletal muscle development and regeneration in vertebrates requires a careful balance between myogenic differentiation and the maintenance of progenitor cells (Buckingham, 2006). During embryonic development, myogenic progenitor cells give rise to myoblasts that further undergo skeletal muscle differentiation. A population of progenitor cells is set aside and later these progenitors generate satellite cells. Satellite cells are the primary stem cells of post-natal skeletal muscle (Dhawan and Rando, 2005; Collins, 2006; Shi and Garry, 2006; Zammit et al., 2006; Le Grand and Rudnicki, 2007). During muscle growth or regeneration after injury, quiescent satellite cells become activated, proliferate, and then either differentiate or return to the satellite quiescent state. The ability to adopt two divergent fates, differentiation or entry into an undifferentiated quiescent state, is maintained by myogenic cells in vitro. Studies utilizing isolated myofibers or myogenic cell cultures show that activated, proliferating satellite cells express both Pax7, a paired-box transcription factor, and MyoD, a basic helix-loop-helix myogenic determination factor. Some cells then down-regulate Pax7, maintain MyoD, and differentiate, and some cells down-regulate MyoD, maintain the expression of Pax7, and remain undifferentiated (Halevy et al., 2004; Zammit et al., 2004). Since quiescent Pax7+/MyoD− cells generated in vitro resemble quiescent satellite cells, the mechanisms regulating the generation of the pool of Pax7+/MyoD− cells may be similar to the mechanisms involved in satellite cell self-renewal (Zammit et al., 2004). Consistently, in the absence of MyoD, satellite cells show an increased propensity for self-renewal rather than differentiation, which results in a deficit in muscle regeneration (Megeney et al., 1996; Sabourin et al., 1999; Yablonka-Reuveni et al., 1999).

The Notch pathway is an evolutionary conserved signaling mechanism that plays critical roles in cell fate decisions during embryonic development and in the adult. The pathway is activated when one of the Notch ligands, a transmembrane protein present at the surface of a signal-sending cell, binds to a Notch receptor present in a signal-receiving cell. In mammals, there are five Notch ligands, (Delta-like 1, 3, and 4, and Jagged 1 and 2) and four Notch receptors (Notch 1–4). The ligand-receptor interaction is followed by the sequential cleavage of the receptor by an ADAM protease and by γ-secretase, leading to the release of the intracellular domain of Notch, NICD, from the plasma membrane and its translocation to the nucleus. Inside the nucleus, NICD forms a complex with the transcription factor CBF1 (also known as RBP-J) and the coactivator Mastermind, and it activates target gene expression (Kadesch, 2004; Bray, 2006; Hurlbut et al., 2007).

The Notch pathway is a critical regulator of myogenesis in cultured myogenic cells, in vertebrate embryos, and in post-natal regenerating muscle (Luo et al., 2005; Vasyutina et al., 2007a). Early muscle development, as well as activation of satellite cells upon muscle injury, are accompanied by activation of Notch 1 signaling (Conboy and Rando, 2002; Brack et al., 2008). Notch signals inhibit myogenesis by blocking the expression and activity of the myogenic determination factor MyoD (Kopan et al., 1994; Shawber et al., 1996; Kuroda et al., 1999; Wilson-Rawls et al., 1999). Consequently, manipulations that activate the Notch pathway inhibit myogenic differentiation and manipulations that decrease the level of Notch signaling promote differentiation. Ectopic expression of a constitutively active form of Notch 1 in myogenic cells cultured in vitro (Kopan et al., 1994; Shawber et al., 1996; Conboy and Rando, 2002) or co-culture of myogenic cells with cells overexpressing Notch ligands (Lindsell et al., 1995; Shawber et al., 1996; Jarriault et al., 1998; Kuroda et al., 1999) blocks myogenic differentiation. Overexpression of Numb, a negative regulator of Notch (Conboy and Rando, 2002; Kitzmann et al., 2006), or inhibition of γ-secretase activity (Kitzmann et al., 2006) promotes cell differentiation. Constitutive activation of Notch signaling in muscle cells during chick limb development by overexpression of Delta1 prevents MyoD expression and leads to inhibition of myogenesis in vivo (Delfini et al., 2000; Hirsinger et al., 2001). Furthermore, myoblasts lacking Stra13, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that modulates Notch signaling, exhibit increased proliferation and defective differentiation (Sun et al., 2007). Megf10, a novel multiple epidermal growth factor repeat transmembrane protein that impinges on Notch signaling stimulates myoblast proliferation and inhibits differentiation (Holterman et al., 2007).

Two recent studies have directly established that Notch signaling is critical for muscle development in the mouse. These studies also revealed that in addition to being a negative regulator of myogenic differentiation, Notch is a positive and essential regulator of muscle progenitor cells. First, Dll1 hypomorph mutant mice show premature myoblast differentiation in the embryo, depletion of progenitor cells, and severe muscle hypotrophy (Schuster-Gossler et al., 2007). Second, conditional mutagenesis of RBP-J in mice results in a similar premature differentiation, depletion of progenitor cells, and lack of muscle growth (Vasyutina et al., 2007b). Both studies indicate that Notch signaling initiated by Dll1 ligand and mediated by RBP-J is essential for maintaining a resident pool of myogenic progenitor cells and preventing their differentiation during muscle development. In the adult, Notch plays an important role in satellite cell expansion during muscle regeneration, and inadequate Notch signaling caused by reduced expression of Dll1 in aging muscle contributes to the loss of its regenerative potential (Conboy et al., 2003).

In summary, it appears that the two pools of cells that are generated simultaneously during myogenesis in vivo or in tissue culture, i.e., terminally differentiated cells and undifferentiated cells with progenitor-like properties, have opposing requirements for Notch signaling. While Notch activation must be relieved in cells progressing into differentiation, Notch signaling must be sustained (or elevated) in progenitors/self-renewing satellite cells/reserve cells to prevent their differentiation. The mechanisms responsible for the regulation of Notch activity in a population of myogenic cells are not well understood.

We and others have shown that, in certain cell systems, the extracellular domains of several Notch ligands, including Dll1, are shed from the cell surface by ADAM proteases (Ikeuchi and Sisodia, 2003; Six et al., 2003; Dyczynska et al., 2007). Ligand shedding down-regulates Notch signaling in neighboring cells (Mishra-Gorur et al., 2002) and may stimulate Notch signaling in a cell-autonomous manner (Dyczynska et al., 2007). Modulation of the Notch pathway by ligand shedding plays an important role in the developing wing in Drosophila (Sapir et al., 2005) and in cortical neurogenesis in mice (Muraguchi et al., 2007). The extent of ligand shedding and its potential role in modulating Notch signaling during myogenic differentiation has not been examined.

In this study, we show that Notch signaling is required for maintaining Pax7 expression in cultures of differentiating mouse primary myoblasts and C2C12 cells. Furthermore, stimulation of Notch activity increases expression of Pax7 and, consistent with previous reports, inhibits myogenic differentiation. Dll1 is proteolytically processed in a pool of C2C12 reserve cells that are Pax7-positive, quiescent and un-differentiated, but Dll1 remains intact in differentiated myotubes. Incubation of primary myoblasts or C2C12 cells with a soluble, dominant-negative mutant form of ADAM12 leads to inhibition of Dll1 cleavage, elevation of Notch signaling, expansion of the pool of Pax7+/MyoD− cells, and reduction of the number of Pax7+/MyoD+ cells. We propose that the proteolytic processing of Dll1, a stochastic event, helps achieve an asymmetry in Notch signaling in a pool of initially equivalent myogenic cells and helps sustain the balance between differentiation and maintenance of undifferentiated cells.

Results

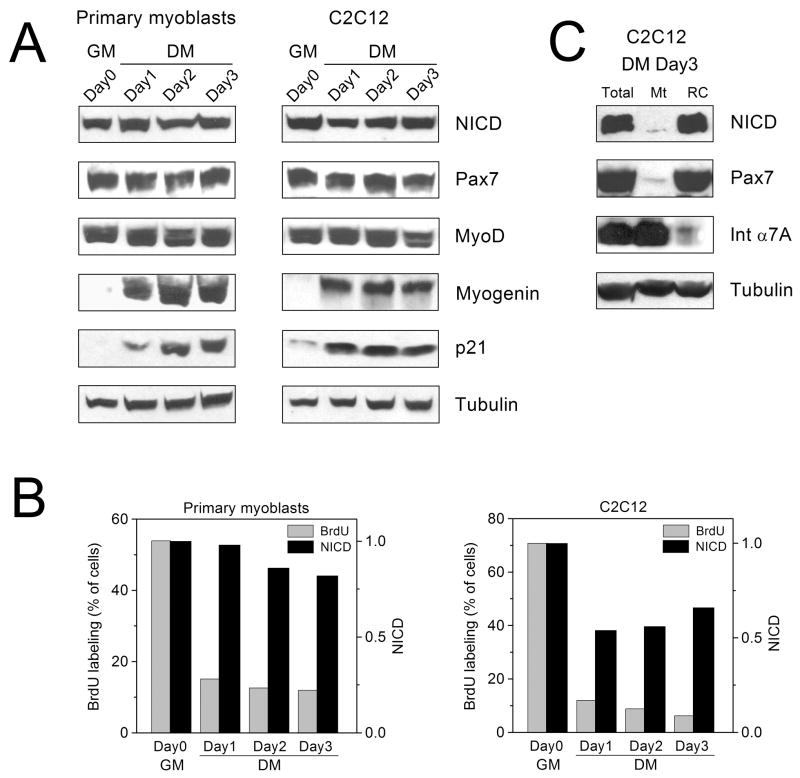

It has been shown previously that Notch is activated during satellite cell activation in vivo, and that active Notch is present in proliferating primary myoblasts in vitro, where it enhances myoblast proliferation and inhibits differentiation (Conboy and Rando, 2002). We examined the amount of active Notch in cultures of myogenic cells at the stage when most of the cells exit the cell cycle and undergo differentiation. Primary mouse myoblasts or C2C12 mouse myogenic cells were incubated in growth medium (GM) containing 10% FBS for 24–48 hours until they were 90–100% confluent, then they were transferred to differentiation medium (DM) containing 2% HS and were incubated for additional 3 days. Early differentiation markers myogenin and cell cycle inhibitor p21 increased during incubation of cells in DM, indicating that some cells progressed into differentiation (Fig. 1A). MyoD and Pax7, a marker of non-differentiating cells, were expressed in cells in GM and remained high in cells incubated in DM (Fig. 1A). The number of proliferating primary cells that incorporated BrdU after the 3-hour pulse labeling decreased from ~55% at day 0 to ~10% at day 3 in DM, and the number of BrdU-labeled C2C12 cells decreased from ~70% at day 0 to ~5% at day 3 (Fig. 1B). Importantly, the level of active Notch 1, determined by Western blotting using epitope-specific anti-Notch 1 antibody that recognizes NICD only after Notch 1 is cleaved by γ-secretase, declined much less dramatically (by ~15% in primary cells and by ~40% in C2C12 cells) between day 0 and day 3 in DM (Fig. 1A,B). After separation of Pax7− differentiated C2C12 myotubes from Pax7+ undifferentiated reserve cells at day 3, NICD was detected exclusively in the reserve cells fraction (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that there is no direct correlation between the number of proliferating cells and the total Notch activity in cultures of differentiating myogenic cells. Instead, Notch 1 remains active in a population of Pax7+ cells that have stopped proliferation and remain undifferentiated.

Figure 1. Notch activity in myogenic cells during differentiation in vitro.

Primary mouse myoblasts or C2C12 cells were incubated in growth medium until they were 90–100% confluent (GM, Day0) and then they were transferred to differentiation medium (DM, Day1–Day3). (A) The levels of active Notch 1 (NICD), Pax7, MyoD, myogenin, p21, and tubulin were determined by Western blotting. NICD was detected using epitope-specific antibody against γ-secretase-cleaved Notch 1. (B) The amount of NICD in panel A was quantified by gel densitometry and normalized to the amount of tubulin (black bars); the amount of NICD at Day0 is set as 1. Percent of BrdU-positive cells was determined after 3-hour pulse BrdU labeling (gray bars). Experiments in A and B were repeated three times with similar results, representative experiments for primary myoblasts and C2C12 are shown. (C) C2C12 cells incubated for 3 days in DM were subjected to partial trypsinization to separate myotubes (Mt, integrin α7A-positive) from reserve cells (RC, Pax7-positive). The amount of NICD in Mt and RC fractions and in total cell lysate was determined by Western blotting.

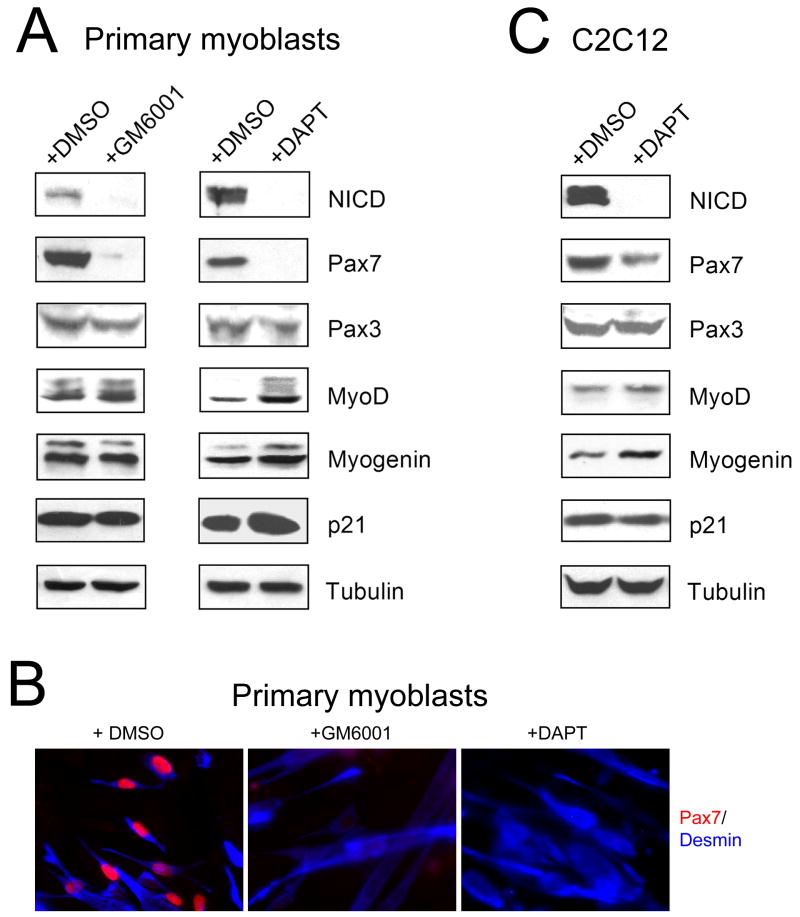

To examine the role of Notch in maintaining the pool of Pax7+ cells, primary myoblasts were incubated for 1 day in DM in the presence of GM6001, a broad-spectrum metalloproteinase inhibitor (Grobelny et al., 1992), or DAPT, a potent and selective inhibitor of γ-secretase activity (Dovey et al., 2001). GM6001, by inhibiting ADAM-mediated cleavage of Notch at the S2 site, prevents the subsequent cleavage at the S3 site by γ-secretase, whereas DAPT directly blocks cleavage and activation of Notch by γ-secretase. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 2A, both GM6001 and DAPT treatment effectively eliminated the active Notch 1, NICD. After treatment with DAPT, the levels of MyoD, myogenin, and p21 were slightly increased, consistent with stimulation of myogenic differentiation upon inhibition of Notch activity (Conboy and Rando, 2002; Kitzmann et al., 2006). Notably, both GM6001 and DAPT dramatically decreased the expression level of Pax7 (Fig. 2A,B), indicating an absolute requirement for the active Notch in the maintenance of Pax7-positive cells. Interestingly, the level of Pax3, the paralogue of Pax7 with partially overlapping functions in myogenic cells (Relaix et al., 2006; Buckingham and Relaix, 2007), was not strongly affected by DAPT treatment (Fig. 2A). Inhibition of Notch by DAPT in C2C12 cells produced similar effects, although inhibition of Pax7 expression was not as potent as in primary myoblasts (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Notch activity is essential for the maintenance of Pax7-positive cells during myogenic differentiation in vitro.

(A) Primary myoblasts, incubated in GM until 90–100% confluency, were transferred to DM and were incubated for 1 day in the presence of DMSO or 5 μM GM6001, a metalloproteinase inhibitor (left), or in the presence of DMSO or 1 μM DAPT, a γ-secretase inhibitor (right). The levels of NICD, Pax7, Pax3, MyoD, myogenin, and p21 were determined by Western blotting, tubulin is a gel-loading control. A representative experiment out of three is shown. (B) Primary myoblasts incubated for 1 day in DM in the presence of DMSO, 5 μM GM6001, or 1 μM DAPT were stained with mouse anti-Pax7 and goat anti-desmin antibodies, and then with Rhodamine Red-X conjugated anti-mouse IgG and AMCA-conjugated anti-goat IgG antibodies. (C) Confluent C2C12 cells were incubated for 1 day in DM in the presence of DMSO or 5 μM DAPT and the levels of NICD, Pax7, Pax3, MyoD, myogenin, p21, and tubulin were analyzed by Western blotting.

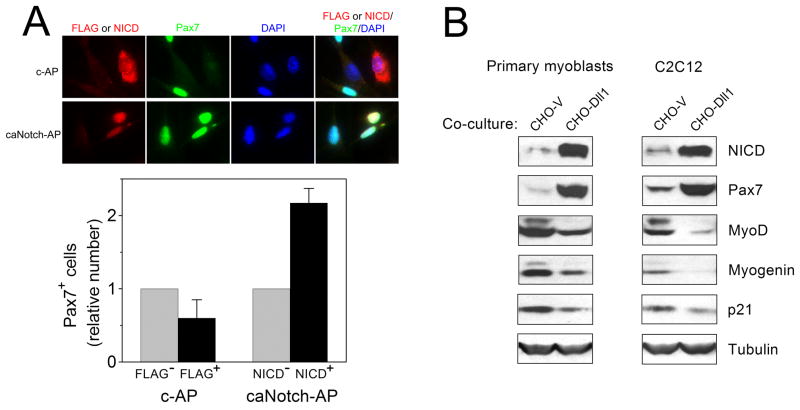

To explore whether increasing Notch activity has any effect on Pax7, we first infected primary myoblasts with retroviruses encoding a constitutively active Notch 1, caNotch. caNotch lacks a major portion of the extracellular domain and is processed to NICD in a ligand-independent manner (Ohtsuka et al., 1999). In contrast to the endogenous NICD which is very hard to visualize by immunofluorescence microscopy (Schroeter et al., 1998), the exogenous NICD can be easily detected in the nuclei of infected cells. We observed that the number of Pax7+ cells was ~2-fold higher among NICD-positive than NICD-negative cells on the same microscopic slide (Fig. 3A). Pax7 expression was not changed in cells infected with control virus (bearing a truncated, inactive Notch 1, detected with anti-FLAG antibody; Fig. 3A). In an alternative approach to stimulate the Notch pathway, primary myoblasts or C2C12 cells were co-cultured with CHO cells stably transfected with mouse Dll1 or with empty vector (Dyczynska et al., 2007). As reported previously (Lindsell et al., 1995; Shawber et al., 1996; Jarriault et al., 1998; Kuroda et al., 1999), co-culture with Dll1-transfected cells inhibited myogenic differentiation, as judged by decreased expression of MyoD and myogenin (Fig. 3B). Importantly, the level of Pax7 both in primary myoblasts and in C2C12 cells co-cultured with Dll1-transfected CHO cells was dramatically increased (Fig. 3B). Collectively, these results indicate that Notch is a critical regulator of the balance between Pax7+ and Pax7− cells.

Figure 3. Notch stimulation expands Pax7-positive cells during myogenic differentiation in vitro.

(A) Primary myoblasts were infected with retroviruses containing constitutively active mouse Notch 1 (caNotch-AP) or with control retroviruses (c-AP). One day after infection, cells were transferred to DM and, one day later, cells were fixed, co-stained with mouse anti-Pax7 and rabbit anti-cleaved Notch 1 (caNotch-AP-infected cells) or anti-FLAG antibodies (c-AP-infected cells), and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. The relative number of Pax7-positive cells among NICD-negative and NICD-positive cells (or FLAG-negative and FLAG-positive cells) on the same slide was calculated (mean ± s.e.m., n=3; at least 200 Pax7-positive cells were counted in each determination). (B) Primary myoblasts or C2C12 cells (~70% confluent) were co-cultured for 1 day with CHO cells stably transfected with mouse Dll1 (CHO-Dll1) or with empty vector (CHO-V). The levels of NICD, Pax7, MyoD, myogenin, p21, and tubulin were analyzed by Western blotting.

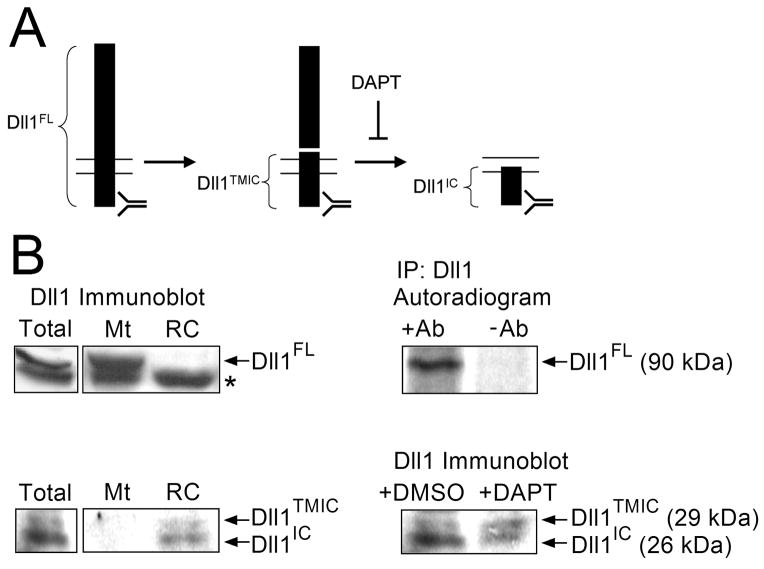

The requirement for the active Notch in Pax7-positive cells and decline of Notch activity in differentiating cells suggest that there must be a heterogeneity in Notch signaling among post-mitotic myogenic cells cultured in vitro. To get insight into possible mechanisms responsible for the heterogenic levels of Notch signaling, we examined the expression, distribution, and proteolytic processing of Dll1, a Notch ligand that plays critical roles in muscle development in vivo (Schuster-Gossler et al., 2007). Similar to the proteolytic processing of Notch, mammalian Dll1 undergoes a sequential cleavage by ADAM proteases and then by γ-secretase (Ikeuchi and Sisodia, 2003; Six et al., 2003; a diagram is depicted in Fig. 4A). The immediate consequence of ADAM-mediated shedding of the extracellular domain of Dll1 is down-regulation of Notch signaling in neighboring cells (Mishra-Gorur et al., 2002; Muraguchi et al., 2007; Sapir et al., 2005) and, possibly, activation of Notch signaling in the same cell (Dyczynska et al., 2007). We have previously observed a cleaved form of the endogenous Dll1 in cultures of primary myogenic cells (Dyczynska et al., 2007). Here, we have used cultures of C2C12 cells incubated for 3 days in DM to separate well-differentiated myotubes (Pax7-negative, low Notch activity) from reserve cells (Pax7-positive, high Notch activity; see Fig. 1C). When total cell extract was subjected to Western blotting using antibody specific for the C-terminus of Dll1, three Dll1 bands were detected: the ~90-kDa full-length form (Dll1FL), the 29-kDa ADAM-cleavage product spanning the transmembrane and the intracellular domains of Dll1 (Dll1TMIC), and the 26-kDa γ-secretase cleavage product comprising the intracellular domain and a short C-terminal segment of the transmembrane domain (Dll1IC). Remarkably, after separation into the myotube and reserve cell fractions, Dll1TMIC and Dll1IC were present only in reserve cells, and no Dll1TMIC or Dll1IC were observed in myotubes (Fig. 4B). In contrast, Dll1FL was more abundant in myotubes than in reserve cells (Fig. 4B). This indicates that the proteolytic processing of Dll1 in differentiating C2C12 cells is asymmetrical, with significantly more cleavage detected in Pax7-positive reserve cells than in Pax7-negative myotubes.

Figure 4. Proteolytic processing of Dll1 in reserve cells.

(A) Schematic diagram of the sequential cleavage of Dll1. The full-length Dll1 (Dll1FL, 90 kDa) is cleaved by an ADAM. The transmembrane and intracellular domain fragment (Dll1TMIC, 29 kDa) is then cleaved by γ-secretase and the intracellular domain (Dll1IC, 26 kDa) is released. The γ-secretase-mediated cleavage is inhibited by DAPT, the antibody recognition site is located in the intracellular domain of Dll1. (B) Left, C2C12 cells incubated in DM for 3 days were separated into myotubes and reserve cells, as in Fig. 1, lyzed, and immunoblotted with anti-Dll1 antibody. Arrows indicate Dll1FL, Dll1TMIC, and Dll1IC, respectively; asterisk marks a non-specific band (left panels). The position of Dll1FL corresponds to the position of the radioactive 90-kDa Dll1FL band detected in the immunoprecipitate from [35S]-labeled C2C12 cells (right, top). Dll1TMIC and Dll1IC contain ~10 times less cysteine and methionine residues than the full-length Dll1 and give weak signals in autoradiograms. The identities of Dll1TMIC and Dll1IC are confirmed by the relative increase in the abundance of Dll1TMIC and decrease in the abundance of Dll1IC after treatment of C2C12 cells with DAPT (right, bottom).

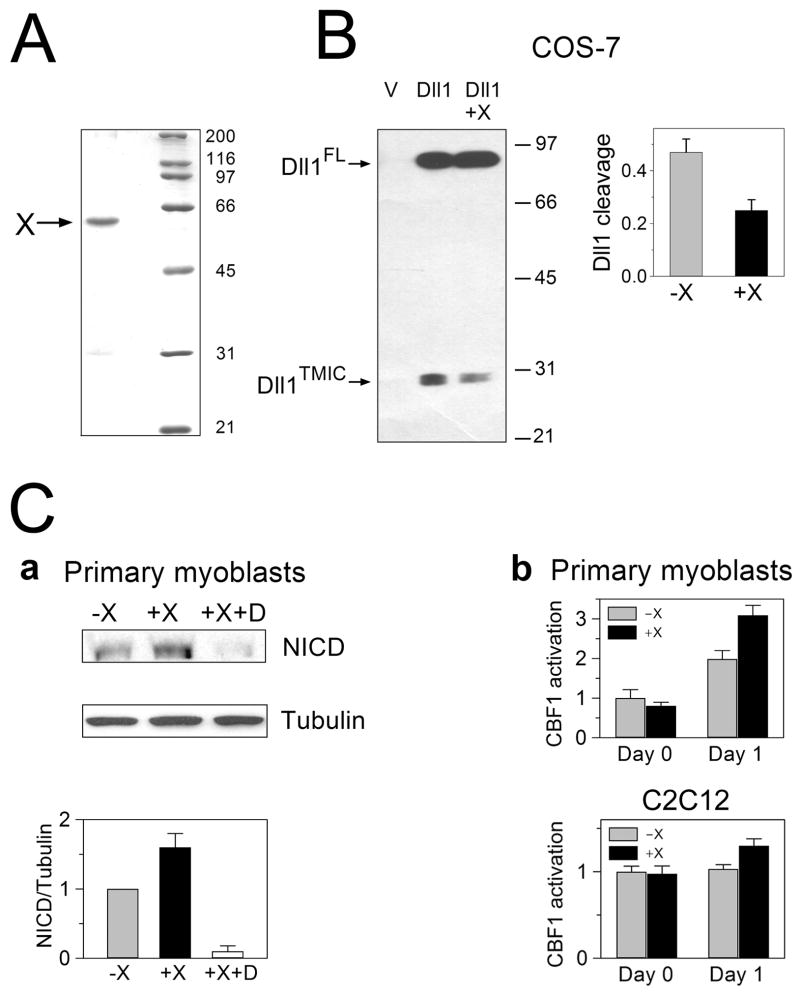

To determine whether the asymmetrical cleavage of Dll1 in Pax7-positive vs Pax7-negative cells is a mere consequence of different proteolytic activities in these two populations of cells or whether it plays a more direct, causal role in establishing an imbalance in Notch signaling and generating two pools of myotubes and reserve cells, we intended to inhibit ADAM-mediated cleavage of Dll1, the first and obligatory step in Dll1 processing. Since several different ADAM proteases expressed in myogenic cells are capable of cleaving Dll1, including ADAM9, 10, 12, and 17 (Dyczynska et al., 2007), and since ADAM10 and ADAM17 also cleave Notch (Brou et al., 2000; Hartmann et al., 2002; Mumm et al., 2000), we adopted a dominant-negative approach rather than knocking down expression of individual ADAMs or using pharmacological inhibitors of ADAM activities. We showed previously that ADAM12 cleaves Dll1 but it does not process Notch, and that ADAM12 forms complexes with Dll1 (Dyczynska et al., 2007). Here, we used the soluble extracellular domain of the catalytically inactive mutant form of ADAM12, expressed and purified from Drosophila S2 cells (recombinant protein X, Fig. 5A), to block the processing of Dll1 by endogenous ADAM proteases. When COS-7 cells were transfected to express murine Dll1, the DllFL and Dll1TMIC forms were observed in Western blots (Fig. 5B; Dll1TMIC is the predominant cleaved form and Dll1IC is poorly detected when Dll1 is overexpressed (Ikeuchi and Sisodia, 2003; Six et al., 2003; Dyczynska et al., 2007)). In the presence of exogenously added purified protein X, the extent of Dll1 cleavage was reduced by ~50% (Fig. 5B), which validated the use of protein X as a dominant-negative modulator of Dll1 cleavage. In primary myoblasts incubated for 1 day in differentiation medium containing protein X, the level of Notch signaling was increased, as demonstrated by the elevated amount of NICD (Fig. 5C.a). Furthermore, a higher transcriptional activity of the CBF1-luciferase reporter gene was observed in primary myoblasts or C2C12 cells incubated in the presence of protein X (Fig. 5C.b). Our interpretation of these results is that protein X, by binding to Dll1, prevents its cleavage by ADAMs but it does not interfere with Dll1 binding and activation of Notch in trans. Thus, higher level of Notch activity in the presence of protein X suggests that ADAM-mediated shedding of Dll1 contributes to down-regulation of Notch signaling in a pool of cells during myogenic differentiation in vitro.

Fig. 5. Soluble, catalytically-inactive extracellular domain of ADAM12 inhibits Dll1 processing and stimulates Notch signaling in myoblasts.

(A) Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel showing the recombinant, soluble, extracellular domain of mouse ADAM12 containing the E349Q mutation in the catalytic site (protein X), expressed in Drosophila S2 cells and purified from culture medium. The molecular weight markers (kDa) are shown on the right. (B) Inhibition of Dll1 cleavage by protein X. Left, COS-7 cells transfected to express Dll1 were incubated for 24 hours in the absence or presence of 2 μM protein X. Right, Cell extracts from Dll1-transfected and empty vector (V)-transfected cells were analyzed by Western blotting using antibody against the cytoplasmic domain of Dll1. Dll1FL and Dll1TMIC are indicated with the arrows, positions of the molecular weight markers are on the right. Left, The extent of Dll1 cleavage was calculated as the ratio of band intensities of Dll1TMIC and Dll1FL (mean ± s.e.m., n=3). (C) The effect of protein X on Notch signaling. (a) Top, Primary myoblasts were incubated for 1 day in DM without protein X or with 2 μM protein X, in the absence or presence of 1 μM DAPT (D). The level of active Notch, NICD, was analyzed by Western blotting using an epitope-specific antibody, tubulin is a gel-loading control. Bottom, The amount of NICD was quantified by densitometry and normalized to the amount of tubulin (mean ± s.e.m., n=3). (b) Primary myoblasts or C2C12 cells were transfected with a CBF1-luciferase reporter and pRL-TK vector, 24h after transfection cells were transferred to DM (Day 0) and incubated for additional 24h (Day 1), in the absence (gray bars) or presence (black bars) of 2 μM protein X. The relative firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay. Fold of CBF1 activation over the level at Day 0, in the absence of protein X, was calculated. The data represent the means ± s.e.m. from three measurements, the experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

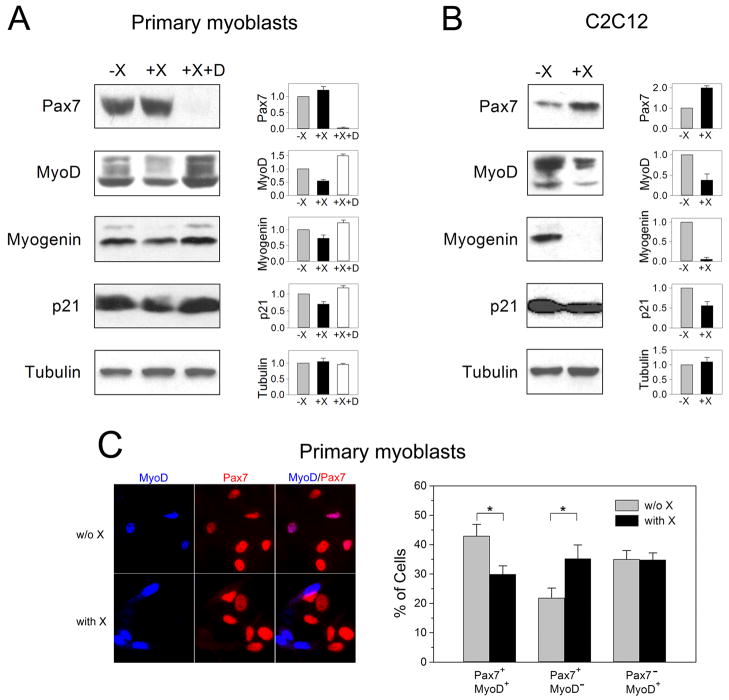

Down-regulation of Dll1 cleavage by protein X had also a negative effect on the progression through a myogenic lineage, as the total levels of MyoD, myogenin, and p21 were decreased by ~50%, 25%, and 25%, respectively (Fig. 6A). In contrast, expression of Pax7 was slightly increased after 1 day incubation of cells in differentiation medium containing protein X (Fig. 6A). The effect of protein X on the level of MyoD, myogenin, p21, and Pax7 were abolished in the presence of γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the effect of protein X was mediated through the activation of Notch signaling, as shown in Fig. 5C. Similar inhibition of MyoD, myogenin, and p21 expression and elevation of Pax7 expression was observed in C2C12 cells upon incubation of cells in DM supplemented with protein X (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, immunofluorescence analysis of cells using anti-MyoD and anti-Pax7 antibody demonstrated that protein X specifically decreased the pool of Pax7+/MyoD+ myoblasts and increased the pool of Pax7+/MyoD− myoblasts, whereas the pool of Pax7−/MyoD+ myoblasts did not seem to be affected (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that the shedding of Dll1, which is partially blocked in the presence of protein X, is important in maintaining the balance between Pax7+/MyoD+ and Pax7+/MyoD− cells.

Fig. 6. The effect of protein X on the myogenic progression and Pax7 expression.

(A) Primary myoblasts were incubated for 1 day in DM without protein X or with 2 μM protein X, in the absence or presence of 1 μM DAPT (D). Levels of Pax7, MyoD, myogenin, p21, and tubulin expression were examined by Western blotting, band intensities were quantified by densitometry and are plotted on the right. Data represent mean values ± s.e.m. from three different experiments. (B) C2C12 cells were incubated for 1 day in DM without or with 2 μM protein X, and the levels of Pax7, MyoD, myogenin, p21, and tubulin expression were examined as in panel A. (C) Left, Primary myoblasts incubated for 1 day in DM without or with 2 μM protein X were co-stained with rabbit anti-MyoD and mouse anti-Pax7 antibodies and with AMCA-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and rhodamine Red-X-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibodies. Two representative images are shown. Right, The numbers of Pax7+/MyoD+, Pax7+/MyoD−, and Pax7−/MyoD+ cells were counted in 15 different microscopic fields, 300–400 cells were analyzed for each experimental condition (without and with protein X). The data show mean values of cells counted on 3 different slides, error bars represent standard error of the mean (*, p<0.05). The experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

Discussion

This study provides an insight into the role of Notch signaling in sustaining the balance between myogenic differentiation and the maintenance of undifferentiated cells in vitro. Our studies suggest that the proteolytic processing of Dll1, a Notch ligand, plays an important role in modulation of Notch signaling and myogenic cell fate determination.

It has been previously shown that the Notch pathway is critical for satellite cell activation and myogenic precursor cell expansion in postnatal myogenesis (Conboy and Rando, 2002). New genetic evidence indicates that Notch signaling initiated by Dll1 and mediated by RBP-J is essential for maintaining a pool of myogenic progenitor cells and for preventing their differentiation during muscle development in mice (Schuster-Gossler et al., 2007; Vasyutina et al., 2007b). In accordance with these studies, we find that Notch signaling is critical in maintaining expression of Pax7, a marker of the undifferentiated state, in quiescent myoblasts in vitro. Inhibition of the Notch pathway using pharmacological inhibitors of either ADAM proteases (GM6001) or γ-secretase (DAPT) abolishes Pax7 expression, and stimulation of Notch signaling expands the pool of Pax7+ cells.

Our results differ from those obtained by Conboy and Rando, where down-regulation of Notch signaling in differentiating myoblast by retrovirally delivered Notch antagonist Numb did not have an effect on the level of Pax7 (Conboy and Rando, 2002). It is possible that application of pharmacological inhibitors of the Notch pathway in our studies might have resulted in a more complete and uniform inhibition of Notch signaling than expression of Numb. Our results are more in line with the study by Kuang et al., in which treatment of freshly isolated proliferating satellite cells with DAPT for 3 days of culture significantly reduced the total number of cells due to a decrease of the number of Pax7+/MyoD− cells (Kuang et al., 2007). While the results of Kuang et al. further support the notion that Notch signaling is vital for satellite cell expansion, our results indicate that Notch is also required to maintain Pax7 expression in a pool of quiescent myoblasts, after they exit the cell cycle. Interestingly, forced expression of Delta1 and activation of the Notch pathway during early avian myogenesis in vivo resulted in down-regulation of MyoD and complete lack of differentiated muscles, but the exit from the cell cycle was not blocked, suggesting that Notch signaling acts in post-mitotic myogenic cells to control a critical step of muscle differentiation (Delfini et al., 2000; Hirsinger et al., 2001). Thus, Notch signaling acts at multiple steps of the muscle development and regeneration processes.

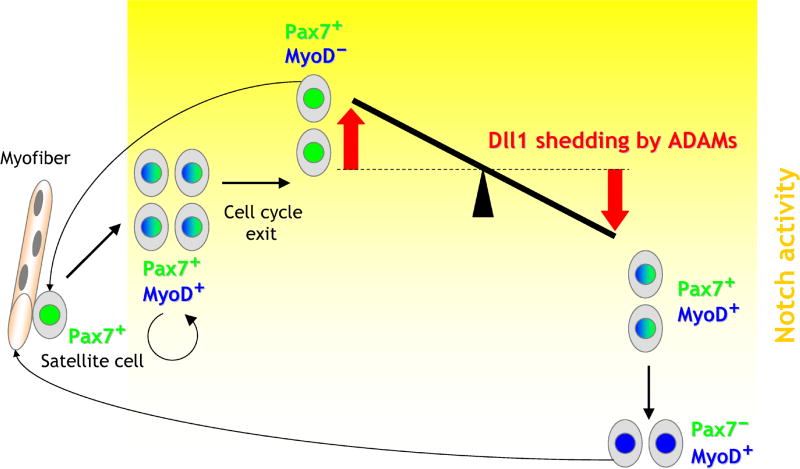

We propose a model in which the level of Notch activity plays a crucial role in cell fate determination after myoblasts exit the cell cycle (Fig. 7). According to this model, the Notch pathway is turned on in activated, proliferating satellite cells that are Pax7+/MyoD+. Upon cell cycle exit, Notch signaling is down-regulated in a subset of Pax7+/MyoD+ cells and it is maintained (or further up-regulated) in self-renewing Pax7+/MyoD− cells that replenish the pool of satellite cells. As Pax7+/MyoD+ cells progress into differentiation, they express myogenin, a negative regulator of Pax7 expression (Olguin et al., 2007), and become Pax7-negative. The loss of Pax7-positive cells in DAPT-treated cultures may thus be related to the effect of Notch on MyoD: low levels of Notch signaling promote high MyoD, induction of myogenin and, in consequence, loss of Pax7. In contrast, expansion of Pax7-positive cells observed after stimulation of the Notch pathway may be a consequence of decreased MyoD and myogenin expression. If this is the case, modulation of Pax7 expression by Notch signaling should be blunted in MyoD−/− myoblasts, a prediction that remains to be tested. To our knowledge, Pax7 is not directly regulated by any of the known Notch target genes.

Fig. 7. Proposed model of modulation of Notch activity by Dll1 shedding during myogenic differentiation.

The Notch pathway is active in proliferating Pax7+/MyoD+ cells derived from Pax7+ quiescent satellite cells. Upon exit from the cell cycle, Notch signaling is down-regulated in Pax7+/MyoD+ cells that later become Pax7−/MyoD+, progress into differentiation, and eventually fuse to give rise to myofibers. The level of Notch activity (shown as the yellow gradient) is maintained (or up-regulated) in Pax7+/MyoD− cells that replenish the pool of satellite cells. The balance between Pax7+/MyoD− and Pax7+/MyoD+ cells is maintained by Dll1 shedding by ADAM proteases in a stochastic and cell density-dependent manner. Dll1 shedding in a pool of cells leads to ligand depletion and down-regulation of Notch signaling in neighboring cells, maintenance of MyoD expression, and eventually loss of Pax7 expression. Cells in which Dll1 cleavage takes place acquire higher level of Notch activity than their neighbors, leading to down-regulation of MyoD and sustained Pax7 expression.

If the level of Notch signaling is set at different levels in Pax7−/MyoD+ and Pax7+/MyoD− cells, the question remains: How are these different levels of Notch signaling simultaneously and spontaneously achieved in two pools of initially equivalent myogenic cells? One mechanism could involve an asymmetric cell division that generates two daughter cells: one with a high Notch activity and one with a low Notch activity (Kuang et al., 2008). Numb is distributed asymmetrically during satellite cell division and it has been postulated that the cell inheriting Numb is the one that acquires low Notch activity and proceeds into differentiation (Conboy and Rando, 2002). However, Numb has been also shown to be asymmetrically segregated to cells that inherit all the older template DNA strands (Shinin et al., 2006), suggesting that Numb-receiving cells are self-renewing (according to the immortal DNA strand hypothesis; Cairns, 1975), rather than differentiating ones. Furthermore, the level of Numb increases significantly after the onset of differentiation (Conboy and Rando, 2002) and, in chick embryo, it is promoted by MyoD expression (Holowacz et al., 2006). This pattern of Numb expression suggests that Numb may reinforce, rather than initiate, the low Notch activity in differentiating cells. In addition, the results presented here and in several other reports (Lindsell et al., 1995; Shawber et al., 1996; Jarriault et al., 1998; Kuroda et al., 1999) have demonstrated that co-culture of myoblasts with Dll1- or Jagged1-overexpressing cells inhibits myogenic differentiation, suggesting that limited ligand availability rather than Numb, may be responsible for the decline of Notch activity in differentiating myogenic cells.

Recent studies indicate that satellite cells are a mixture of stem cells and committed myogenic progenitors (Collins, 2006; Kuang et al., 2007; Zammit et al., 2006) and that asymmetric division of stem cells in vivo yields one stem cell and one committed daughter cell (Kuang et al., 2007). The two daughter cells show asymmetric expression of Dll1, with higher Dll1 level (and most likely lower Notch activity) in the committed cell. This asymmetric cell division is favored by a specific stem cell niche and it occurs perpendicular to the muscle fiber, with Dll1 being expressed in the cell that maintains contact with the plasmalemma (Kuang et al., 2007). Whether such oriented cell division with asymmetric expression of Dll1 takes place in satellite cells cultured in vitro and deprived of the niche regulation is not clear. It appears that the modulation of Notch signaling among cells cultured in vitro may be achieved in large part by stochastic mechanisms (Losick and Desplan, 2008). We propose that one of these mechanisms involves the proteolytic processing of Dll1 by ADAM proteases (Fig. 7), a hypothesis supported by two observations. First, in C2C12 cells, we detect the cleaved Dll1 in undifferentiated reserve cells but not in differentiated myotubes. Second, inhibition of Dll1 processing by soluble, catalytically inactive extracellular domain of ADAM12, protein X, elevates the global Notch signaling and increases the pool of Pax7+/MyoD− cells, with the concomitant decrease of the pool of Pax7+/MyoD+ cells (Figs. 5 and 6). These studies confirm and extend our previous observations obtained for C2C12 cells, where the soluble protein X inhibited myogenic differentiation (Yi et al., 2005) and overexpression of the wild-type ADAM12 decreased MyoD expression (Cao et al., 2003).

According to the model in Fig. 7, Dll1 shedding helps establish a balance between Pax7+/MyoD+ and Pax7+/MyoD− cells after the exit from the cell cycle. Proteolytic processing of Dll1 by ADAMs in some cells leads to ligand depletion and down-regulation of Notch signaling in neighboring cells. Cells in which Dll1 cleavage takes place would acquire higher level of Notch activity than their neighbors, leading to down-regulation of MyoD. Cells in which the cleavage of Dll1 does not occur or occurs less efficiently would attain lower level of Notch signaling and maintain MyoD expression. Inhibition of Dll1 processing by soluble protein X did not seem to have a direct effect on the number of Pax7−/MyoD+ cells (Fig. 6C), and thus the balance between Pax7+/MyoD+ and Pax7−/MyoD+ cells may not be controlled by the cleavage of Dll1. Furthermore, since MyoD is a positive regulator of Delta-1 in Xenopus (Wittenberger et al., 1999), it is possible that MyoD stimulates Dll1 expression and further up-regulates Notch signaling in neighboring Pax7+/MyoD− cells. This would provide another means to increase Dll1 expression in cells with declining Notch activity, in addition to the relief of the transcriptional repression mediated by Notch (Greenwald, 1998; Wilkinson et al., 1994). Stimulation of Numb expression by MyoD (Holowacz et al., 2006), on the other hand, should down-regulate Notch and further consolidate the differences in Notch signaling among MyoD+ and MyoD− cells.

While other stochastic models of myogenic cell fate determination invoke random changes in the level of expression of the Notch pathway components, myogenic factors, or Pax7, we place the main emphasis on the proteolytic processing of Dll1 as the initial trigger of the asymmetry in Notch signaling between seemingly equivalent cells. Since Dll1 cleavage occurs at the cell surface, is cell-density dependent, and may be influenced by intracellular events (Dyczynska et al., 2007; Zolkiewska, 2008), it combines features of a stochastic, as well as regulated mechanism of Notch modulation. Finally, our model is not mutually exclusive with oriented cell division, which may be most relevant in vivo where it becomes subject to niche regulation. The extent to which Dll1 shedding contributes to the regulation of Notch signaling and myogenic cell fate determination during muscle development, growth, and regeneration in vivo remains to be determined.

Materials and Methods

Expression constructs

Dll1-pcDNA3.1 expression vector has been described previously (Dyczynska et al., 2007; 2008). Notch reporter vector containing eight CBF-1 binding sites (pJT123A) was provided by P. D. Ling (Baylor College of Medicine). caNotch-AP retroviral vector directed expression of the constitutively active mouse Notch 1 spanning the transmembrane region, the RAM23 domain, the cdc10/ankyrin repeats, and the nuclear localization signal (aa 1704–2192), and c-AP vector lacking the RAM23 and cdc10/ankyrin repeats sequences, was a negative control (Ohtsuka et al., 1999). caNotch-AP and c-AP vectors were obtained from R. Kageyama and C. Takahashi (Kyoto University).

Cells

C2C12 and COS-7 cells were obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection; Drosophila S2 cells were from Invitrogen; the retroviral packaging cell line Phoenix Eco was provided by Dr. Garry P. Nolan (Stanford University). C2C12, COS-7, and Phoenix Eco cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 under a humidified atmosphere. CHO cells stably transfected with mouse Dll1 or with empty vector were grown in F12K nutrient mixture supplemented with 10% FBS and 800 μg/ml G418, as described (Dyczynska et al., 2007). Drosophila S2 cells were cultured at 27°C in Schneider’s Drosophila medium containing 10% heat inactivated FBS. Primary myoblasts were isolated from hindlimbs and forelimbs of neonatal C57BL/6 mice (2–5 days old) as described (Rando and Blau 1994). The muscle tissue was incubated in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) with 1% collagenase II (Invitrogen), 2.4 U/ml dispase II (Roche) and 2.5 mM CaCl2 for 45 minutes at 37°C, and then passed through 100-μm nylon mesh filter (BD Biosciences). The filtrate was centrifuged, the cell pellet was suspended in Ham’ F-10 medium (Cambrex) containing 20% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, pre-plated for 30 minutes on collagen I-coated plates, and then plated on tissue culture-treated plastic plates. To stimulate differentiation, 90–100% confluent primary myoblasts or C2C12 cells were transferred to DMEM containing 2% horse serum.

Plasmid transfection and retroviral infection

Transient transfections were performed using Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacture’s protocol, one day after plating cells. For generation of retroviruses, virus packaging Phoenix Eco cells were transfected with a retroviral expression vector (15 μg plasmid DNA per 100-mm plate) using calcium phosphate precipitation method, viral supernatants were harvested 48 hours later, supplemented with 5 μg/ml polybrene, and used to infect primary myoblasts.

Protein expression and purification

Drosophila S2 cells stably transfected with the extracellular domain of ADAM12 containing the E349Q mutation (protein X) (Yi et al. 2005) were incubated for 5 days in the presence of 0.5 mM CuSO4. Culture medium was collected 5 days later, and protein X was purified by sequential chromatography on a chelating Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences) and a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose column (Qiagen) (Yi et al., 2005). The final column eluate was dialyzed against DMEM, supplemented with 2% HS or 10% FBS, and added to cells.

Cell treatments

Primary myoblasts were cultured in growth medium until 90%–100% confluency and then they were incubated for 24 hours in differentiation medium (DMEM plus 2% horse serum) with 1 μM DAPT (Calbiochem), 50 μM GM6001 (Chemicon; both dissolved in DMSO), or DMSO alone. Confluent C2C12 cells were incubated for 1 day in DM with 5 μM DAPT or DMSO. In the experiments analyzing the effect of protein X, medium was prepared by adding 2% HS (for primary myoblasts and C2C12 cells) or 10% FBS (for COS-7 cells) directly to the solution of protein X (final concentration: 2 μM) dialyzed against DMEM or to DMEM that was retrieved as the external dialysis solution. For analysis of cell proliferation, primary myoblasts or C2C12 cells were incubated with 10 μM 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) for 3 hours prior to fixation and staining with anti-BrdU antibody. For 35S-labeling, C2C12 cells were incubated for 3 days in DM and then for 16 h in methionine/cysteine-free DM containing EasyTag 200 μCi/ml Expre[35S][35S]-Protein Labeling Mix (PerkinElmer).

Separation of myotubes and reserve cells

Differentiating cultures of C2C12 cells were separated into myotubes and reserve cells essentially as described earlier (Kitzmann et al., 1998; Cao et al., 2003). C2C12 cells were incubated for 3 days in DM and subjected to mild trypsinization (0.05% trypsin and 1 mM EDTA in DPBS, 1 minute treatment). Detached myotubes were collected first and the remaining undifferentiated reserve cells were detached by 5 min incubation with 0.25% trypsin and 1 mM EDTA in DPBS. The purity of the myotube and reserve cell fractions was assessed by Western blotting with anti-integrin α7A and anti-Pax7 antibodies, respectively.

Cell co-culture experiments

Primary myoblasts or C2C12 cells were plated in 6-well plates. One day later, when cells were ~70% confluent, CHO cells stably transfected with mouse Dll1 or empty vector were added (5 × 105 cells/well) and incubated in DM without G418. Twenty four hours later, cells were washed and 300 μl of extraction buffer was added to wells.

Western blotting

Cells were incubated in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzene-sulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF), 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 mM 1,10-phenanthroline) for 15 minutes at 4°C. Cell extracts were centrifuged at 21,000×g for 15 min, supernatants were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked in DPBS containing 3% (w/v) dry milk and 0.3% (v/v) Tween 20, then incubated with primary antibodies in blocking buffer, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies and detection using the WestPico chemiluminescence kit (Pierce). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-Dll1 (H-265, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200), mouse anti-p21 (F-5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000), mouse anti-myogenin (F5D, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200), rabbit anti-MyoD (C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:500), mouse anti-MyoD (5.8A, Lab Vision, 1:500), mouse anti-Pax7 (ascites, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:250), mouse anti-Pax3 (ascites, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:500), rabbit anti-cleaved Notch 1 (Val1744, Cell Signaling, 1:500), mouse anti-α-tubulin (Sigma, 1:100,000), rabbit anti-integrin α7A (a gift from Stephen J. Kaufman, 1:2000). Secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG antibodies.

Immunofluorescence

Cells grown on glass coverslips or in plastic chamber wells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in DPBS for 20 minutes and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in DPBS for 5 min. Cells were blocked in DPBS containing 5% donkey serum (v/v) and 1% BSA (w/v), then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 1% BSA, followed by incubation with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. The primary antibodies used were: mouse anti-Pax7 (supernatant, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, 1:5), rabbit anti-MyoD (C-20, 1:50), goat anti-desmin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:50), rabbit anti-cleaved Notch 1 (Val1744, 1:50); rabbit anti-FLAG (Affinity BioReagents, 1:1000). For detection of BrdU-stained nuclei, fixed cells were treated with 70% ethanol and 50 mM glycine, pH 2.0, then with 4N HCl for 15 minutes at room temperature to denature DNA, and then cells were stained with rat anti-BrdU antibody (Abcam, 1:100). Secondary antibodies were coupled Alexa488, rhodamine Red-X or AMCA. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Coverslips were mounted on slides and examined by Axiovert 200 inverted fluorescent microscope (Zeiss).

Luciferase reporter assays

Primary myoblasts or C2C12 cells grown in 96-well plates were transfected at 60% confluency with 0.05 μg CBF1 firefly luciferase gene reporter vector and 0.005 μg Renilla luciferase (pRL-TK) vector as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Twenty four hours after transfection, cells were transferred to DM. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) at day 0 and day 1 in DM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paul D. Ling for the CBF1 reporter plasmid, Drs. R. Kageyama and C. Takahashi for the caNotch retroviral vector, Dr. Garry P. Nolan for Phoenix Eco cells, and Dr. Stephen J. Kaufman for anti-integrin α7A antibody. This work was supported by NIH grant GM065528 to AZ. This is contribution 08-345-J from Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

Abbreviations

- ADAM

protein containing a disintegrin and metalloprotease

- Dll1

Delta-like 1

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DPBS

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HS

horse serum

- AEBSF

4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride

- AMCA

7-amino-4-methylcoumarin-3-acetic acid

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DAPT

N-[N-(3,5-di-uorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester

- BrdU

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

References

- Brack AS, Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Shen J, Rando TA. A temporal switch from Notch to Wnt signaling in muscle stem cells is necessary for normal adult myogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brou C, Logeat F, Gupta N, Bessia C, LeBail O, Doedens JR, Cumano A, Roux P, Black RA, Israel A. A novel proteolytic cleavage involved in Notch signaling: the role of the disintegrin-metalloprotease TACE. Mol Cell. 2000;5:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M. Myogenic progenitor cells and skeletal myogenesis in vertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M, Relaix F. The role of Pax genes in the development of tissues and organs: Pax3 and Pax7 regulate muscle progenitor cell function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:645–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns J. Mutation selection and the natural history of cancer. Nature. 1975;255:197–200. doi: 10.1038/255197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Zhao Z, Gruszczynska-Biegala J, Zolkiewska A. Role of metalloprotease disintegrin ADAM12 in determination of quiescent reserve cells during myogenic differentiation in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6725–6738. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6725-6738.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CA. Satellite cell self-renewal. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, Smythe GM, Rando TA. Notch-mediated restoration of regenerative potential to aged muscle. Science. 2003;302:1575–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1087573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy IM, Rando TA. The regulation of Notch signaling controls satellite cell activation and cell fate determination in postnatal myogenesis. Dev Cell. 2002;3:397–409. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfini MC, Hirsinger E, Pourquie O, Duprez D. Delta 1-activated Notch inhibits muscle differentiation without affecting Myf5 and Pax3 expression in chick limb myogenesis. Development. 2000;127:5213–5224. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.23.5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan J, Rando TA. Stem cells in postnatal myogenesis: molecular mechanisms of satellite cell quiescence, activation and replenishment. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey HF, John V, Anderson JP, Chen LZ, de Saint AP, Fang LY, Freedman SB, Folmer B, Goldbach E, Holsztynska, et al. Functional γ-secretase inhibitors reduce β-amyloid peptide levels in brain. J Neurochem. 2001;76:173–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyczynska E, Sun D, Yi H, Sehara-Fujisawa A, Blobel CP, Zolkiewska A. Proteolytic processing of Delta-like 1 by ADAM proteases. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:436–444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605451200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyczynska E, Syta E, Sun D, Zolkiewska A. Breast cancer-associated mutations in metalloprotease disintegrin ADAM12 interfere with the intracellular trafficking and processing of the protein. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2634–2640. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald I. LIN-12/Notch signaling: lessons from worms and flies. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1751–1762. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobelny D, Poncz L, Galardy RE. Inhibition of human skin fibroblast collagenase, thermolysin, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase by peptide hydroxamic acids. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7152–7154. doi: 10.1021/bi00146a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevy O, Piestun Y, Allouh MZ, Rosser BW, Rinkevich Y, Reshef R, Rozenboim I, Wleklinski-Lee M, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. Pattern of Pax7 expression during myogenesis in the posthatch chicken establishes a model for satellite cell differentiation and renewal. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:489–502. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann D, de Strooper B, Serneels L, Craessaerts K, Herreman A, Annaert W, Umans L, Lubke T, Lena IA, von Figura K, Saftig P. The disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM 10 is essential for Notch signalling but not for α-secretase activity in fibroblasts. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2615–2624. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.21.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsinger E, Malapert P, Dubrulle J, Delfini MC, Duprez D, Henrique D, Ish-Horowicz D, Pourquie O. Notch signalling acts in postmitotic avian myogenic cells to control MyoD activation. Development. 2001;128:107–116. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holowacz T, Zeng L, Lassar AB. Asymmetric localization of Numb in the chick somite and the influence of myogenic signals. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:633–645. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holterman CE, Le Grand F, Kuang S, Seale P, Rudnicki MA. Megf10 regulates the progression of the satellite cell myogenic program. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:911–922. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut GD, Kankel MW, Lake RJ, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Crossing paths with Notch in the hyper-network. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi T, Sisodia SS. The Notch ligands, Delta1 and Jagged2, are substrates for presenilin-dependent “γ-secretase” cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7751–7754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200711200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarriault S, Le Bail O, Hirsinger E, Pourquie O, Logeat F, Strong CF, Brou C, Seidah NG, Israël A. Delta-1 activation of Notch-1 signaling results in HES-1 transactivation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7423–7431. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadesch T. Notch signaling: the demise of elegant simplicity. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann M, Carnac G, Vandromme M, Primig M, Lamb NJC, Fernandez A. The muscle regulatory factors MyoD and Myf-5 undergo distinct cell cycle-specific expression in muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1447–1459. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann M, Bonnieu A, Duret C, Vernus B, Barro M, Laoudj-Chenivesse D, Verdi JM, Carnac G. Inhibition of Notch signaling induces myotube hypertrophy by recruiting a subpopulation of reserve cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:538–548. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R, Nye JS, Weintraub H. The intracellular domain of mouse Notch: A constitutively activated repressor of myogenesis directed at the basic helix-loop-helix region of MyoD. Development. 1994;120:2385–2396. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Gillespie MA, Rudnicki MA. Niche regulation of muscle satellite cell self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang S, Kuroda K, Le Grand F, Rudnicki MA. Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell. 2007;129:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda K, Tani S, Tamura K, Minoguchi S, Kurooka H, Honjo T. Delta-induced Notch signaling mediated by RBP-J inhibits MyoD expression and myogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7238–7244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand F, Rudnicki MA. Skeletal muscle satellite cells and adult myogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:628–633. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsell CE, Shawber CJ, Boulter J, Weinmaster G. Jagged: a mammalian ligand that activates Notch1. Cell. 1995;80:909–917. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losick R, Desplan C. Stochasticity and cell fate. Science. 2008;320:65–68. doi: 10.1126/science.1147888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo D, Renault VM, Rando TA. The regulation of Notch signaling in muscle stem cell activation and postnatal myogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:612–622. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megeney LA, Kablar B, Garrett K, Anderson JE, Rudnicki MA. MyoD is required for myogenic stem cell function in adult skeletal muscle. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1173–1183. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra-Gorur K, Rand MD, Perez-Villamil B, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Down-regulation of Delta by proteolytic processing. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:313–324. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumm JS, Schroeter EH, Saxena MT, Griesemer A, Tian X, Pan DJ, Ray WJ, Kopan R. A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates γ-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol Cell. 2000;5:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80416-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraguchi T, Takegami Y, Ohtsuka T, Kitajima S, Chandana EP, Omura A, Miki T, Takahashi R, Matsumoto N, Ludwig A, Noda M, Takahashi C. RECK modulates Notch signaling during cortical neurogenesis by regulating ADAM10 activity. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:838–845. doi: 10.1038/nn1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka T, Ishibashi M, Gradwohl G, Nakanishi S, Guillemot F, Kageyama R. Hes1 and Hes5 as notch effectors in mammalian neuronal differentiation. EMBO J. 1999;18:2196–2207. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olguin HC, Yang Z, Tapscott SJ, Olwin BB. Reciprocal inhibition between Pax7 and muscle regulatory factors modulates myogenic cell fate determination. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:769–779. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando TA, Blau HM. Primary mouse myoblast purification, characterization, and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1275–1287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.6.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Montarras D, Zaffran S, Gayraud-Morel B, Rocancourt D, Tajbakhsh S, Mansouri A, Cumano A, Buckingham M. Pax3 and Pax7 have distinct and overlapping functions in adult muscle progenitor cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:91–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin LA, Girgis-Gabardo A, Seale P, Asakura A, Rudnicki MA. Reduced differentiation potential of primary MyoD−/− myogenic cells derived from adult skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:631–643. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapir A, Assa-Kunik E, Tsruya R, Schejter E, Shilo BZ. Unidirectional Notch signaling depends on continuous cleavage of Delta. Development. 2005;132:123–132. doi: 10.1242/dev.01546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster-Gossler K, Cordes R, Gossler A. Premature myogenic differentiation and depletion of progenitor cells cause severe muscle hypotrophy in Delta1 mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:537–542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawber C, Nofziger D, Hsieh JJ, Lindsell C, Bogler O, Hayward D, Weinmaster G. Notch signaling inhibits muscle cell differentiation through a CBF1-independent pathway. Development. 1996;122:3765–3773. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Garry DJ. Muscle stem cells in development, regeneration, and disease. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1692–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.1419406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinin V, Gayraud-Morel B, Gomes D, Tajbakhsh S. Asymmetric division and cosegregation of template DNA strands in adult muscle satellite cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:677–687. doi: 10.1038/ncb1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Six E, Ndiaye D, Laabi Y, Brou C, Gupta-Rossi N, Israel A, Logeat F. The Notch ligand Delta1 is sequentially cleaved by an ADAM protease and γ-secretase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7638–7643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230693100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Li L, Vercherat C, Gulbagci NT, Acharjee S, Li J, Chung TK, Thin TH, Taneja R. Stra13 regulates satellite cell activation by antagonizing Notch signaling. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:647–657. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasyutina E, Lenhard DC, Birchmeier C. Notch function in myogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2007a;6:1451–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasyutina E, Lenhard DC, Wende H, Erdmann B, Epstein JA, Birchmeier C. RBP-J (Rbpsuh) is essential to maintain muscle progenitor cells and to generate satellite cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007b;104:4443–4448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610647104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson HA, Fitzgerald K, Greenwald I. Reciprocal changes in expression of the receptor lin-12 and its ligand lag-2 prior to commitment in a C. elegans cell fate decision. Cell. 1994;79:1187–1198. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Rawls J, Molkentin JD, Black BL, Olson EN. Activated Notch inhibits myogenic activity of the MADS-Box transcription factor myocyte enhancer factor 2C. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2853–2862. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberger T, Steinbach OC, Authaler A, Kopan R, Rupp RA. MyoD stimulates Delta-1 transcription and triggers notch signaling in the Xenopus gastrula. EMBO J. 1999;18:1915–1922. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yablonka-Reuveni Z, Rudnicki MA, Rivera AJ, Primig M, Anderson JE, Natanson P. The transition from proliferation to differentiation is delayed in satellite cells from mice lacking MyoD. Dev Biol. 1999;210:440–455. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi H, Gruszczynska-Biegala J, Wood D, Zhao Z, Zolkiewska A. Cooperation of the metalloprotease, disintegrin, and cysteine-rich domains of ADAM12 during inhibition of myogenic differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23475–23483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413550200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit PS, Golding JP, Nagata Y, Hudon V, Partridge TA, Beauchamp JR. Muscle satellite cells adopt divergent fates: a mechanism for self-renewal? J Cell Biol. 2004;166:347–357. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit PS, Partridge TA, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. The skeletal muscle satellite cell: the stem cell that came in from the cold. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1177–1191. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6R6995.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkiewska A. ADAM proteases: ligand processing and modulation of the Notch pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2056–2068. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7586-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]