Abstract

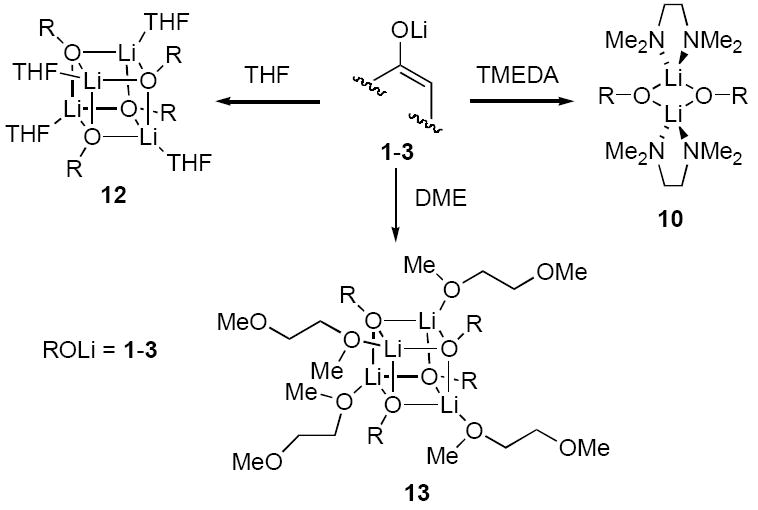

The method of continuous variation in conjunction with 6Li NMR spectroscopy was used to characterize lithium enolates derived from 1-indanone, cyclohexanone, and cyclopentanone in solution. The strategy relies on forming ensembles of homo- and heteroaggregated enolates. The enolates form exclusively chelated dimers in N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine and cubic tetramers in tetrahydrofuran and 1,2-dimethoxyethane.

Introduction

Lithium enolates are used pervasively throughout organic synthesis.1 A comprehensive survey of scaled procedures used by Pfizer Process over two decades shows that 68% of all C-C bond formations are carbanion based and 44% of these involve enolates.2,3 Even a casual survey of synthesis papers emanating from academic labs reinforces the notion that lithium enolates are indispensible.1 It may seem puzzling, therefore, that structure-reactivity relationships in enolates--the influence of solvation and aggregation on reactivity--are poorly understood when compared with other commonly used classes of organolithiums such as alkyllithiums and lithium amides.4,5,6,7,8 The primary contributions have come from Jackman and coworkers,4a,d,5 Streitwieser and coworkers,6 and several research groups focusing on methacrylate ester polymerizations.7 The limited progress toward understanding lithium enolates is glaringly simple: Despite extensive crystallographic determinations of lithium enolates,9 there are few methods for determining enolate structures in solution and none are general (vide infra). Without an understanding of solution structure, detailed mechanistic studies are not possible.10,11,12

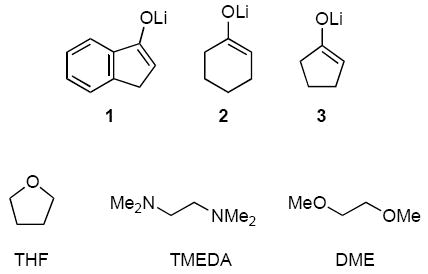

In the study described below, we characterize simple ketone enolates 1-3 coordinated by N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA), tetrahydrofuran (THF), and 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME). The strategy relies on the method of continuous variation in which ensembles of homo- and heteroaggregated enolates are monitored by 6Li NMR spectroscopy. The results illustrate how ligands influence the structures of enolates. Of greater importance, however, is that the strategy promises to be general.

Background

Structures of Lithium Enolates in Solution

Based on analogy with crystal structures of lithium enolates and related organolithiums,9,13 one might surmise that 1-3 form monomers, dimers, tetramers, or hexamers (4-7) in solution. Such a claim, however, is wrought with risk. Although crystal structures offer important views of lithium enolates, one cannot infer from crystal structures the dominance or even the existence of these forms in solution: solution aggregation numbers must be determined independently.14 Unfortunately, the structures of lithium enolates in solution are not easily examined using NMR spectroscopy because of the high inherent symmetries of 4-7 and opaque Li-O connectivities arising from the absence of scalar Li-O coupling. Consequently, structural organolithium chemists have turned to indirect methods for probing the aggregation of lithium enolates in solution. Progress reported to date is limited and easily summarized.

Colligative measurements are often used to study aggregation behavior15 and have been used to examine lithium enolates and related O-lithiated species on several occasions.16 Unfortunately, such measurements are sensitive to potentially undetectable impurities and offer dangerously simple answers when complex equilibria might be involved. In our opinion, they are of marginal use unless corroborated by an independent spectroscopic method.

Streitwieser and coworkers monitored mixed aggregate equilibria derived from lithium enolate-carbanion mixtures to study aggregation of enolates in ethereal solvents.6 Their methods are rigorous, but a reliance on UV spectroscopy and ultra-high dilution has restricted their studies to enolates derived from aromatic ketones and esters. Jackman and coworkers used 13C spin-lattice relaxation times, colligative measurements, and 7Li quadrupolar splitting constants (QSCs) to conclude that lithium phenylisobutyrate and several related hindered aromatic enolates are dimers or tetramers.5,17 More recently, Noyori and coworkers reported that addition of hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA) to lithium cyclopentenolate (3) affords the enolate dimer.18 Subsequently, Reich concluded that addition of HMPA to 3 in THF causes serial ligand substitution of a tetramer to the exclusion of detectable deaggregation.19 Noyori appears to have been misled by a flawed colligative measurement of lithium cyclopentenolate in THF reported years earlier.16c (We concur with Reich; vide infra). Jacobsen and coworkers, in a fleeting foray into organolithium chemistry, used a combination of methods (including a serial solvation akin to Reich’s approach) to show that lithium pinacolate forms a very odd trisolvated tetramer in pyridine/cyclohexane solution.20 Hindered ester enolates central to methacrylate ester polymerizations have been shown to aggregate in solution. A combination of colligative and spectroscopic measurements provide a strong circumstantial case supporting dimers and tetramers.7

We began studying lithium enolates as part of a collaboration with Sanofi-Aventis to examine the structure and reactivity of enolate 8.21 Mixtures of antipodes (R)-8 and (S)-8 afforded an ensemble of aggregates (eq 1) that could be monitored by 6Li NMR spectroscopy. Both the number of heteroaggregates and their dependencies on relative proportions of (R)-8 and (S)-8 proved highly characteristic of hexamers and inconsistent with monomers, dimers, and tetramers.

| (1) |

Method of Continuous Variation

The protocol used to characterize 8 and adapted to characterize 1-3 formally falls under the rubric of the method of continuous variation22 (also called the method of Job23), which has found widespread application in chemistry and biochemistry.24 A brief digression may be instructive.

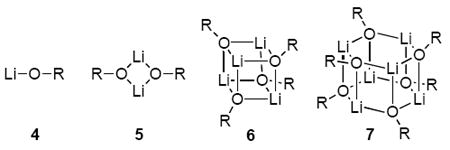

In its simplest and most prevalent usage, the method of continuous variation identifies the stoichiometry of a single complex (or aggregate) in solution. Imagine species A and B form an AB complex (eq 2). Plotting a physical property (P) that reflects the concentration of AB versus mole fraction of A (XA) affords what is often called a Job plot (Figure 1). The stoichiometry of the complex is gleaned from the position of the maximum ([AB]max) along the X-axis; an AB complex affords [AB]max at XA = 0.5. If, however, AB2 or A2B complexes are formed, the maxima appear at XA = 0.33 and 0.67, respectively. The magnitude of the equilibrium constant (Keq) is reflected in the shape of the curve: A sharp apex (solid line in Figure 1) results from Keq ≫ 1, whereas the curve (dotted line) is emblematic of Keq ≈ 1.

Figure 1.

Representative Job plot showing a physical property, P, of complex AB as a function of mole fraction (XA) of component A. [AB]max corresponds to the maximum concentration of complex AB. The solid line (—) illustrates Keq ≫ 1. The dotted curve (---) illustrates Keq ≈ 1.

| (2) |

Ensembles of Aggregates

The method of continuous variation can, in principle, be extended to complex systems in which an ensemble of AmBn aggregates is observed, and indeed some progress has been made. There are several instances in organolithium chemistry, for example, in which investigators studied heteroaggregation with the expressed purpose of demonstrating homoaggregation is probable.25 The earliest report appears to be that of Brown and coworkers in which they demonstrated a penchant for tetramer formation by showing that mixtures of methyllithium and lithium chloride afford mixed tetramers.26 Brown considered the influence of proportions on the distribution of aggregates, but the studies were largely qualitative. Günther and coworkers used mixtures of deuterated and undeuterated organolithiums to cleverly circumvent potentially costly and tedious 13C labeling of organolithiums.27 The study of sodium alkoxides by Gagne and coworkers is probably most germane to the study described below.28 1H NMR spectroscopy was used to probe ensembles of sodium alkoxide tetramers, with the symmetries of the mixed tetramers playing a significant role.29

During studies of enolate 8, we provided a general solution to the problem of monitoring and quantitating large ensembles of aggregates. We illustrate the method using the generic ensemble described by eq 3

| (3) |

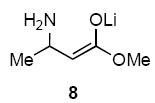

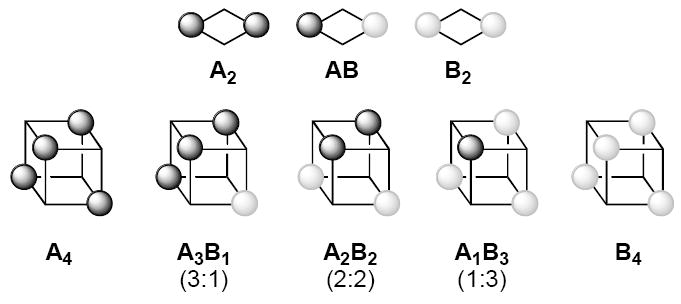

Table 1 summarizes the predicted number of spectroscopically distinct structural forms observed for monomers, cyclic dimers, cubic tetramers, and hexagonal hexamers derived from An/Bn mixtures. Because of their importance in this paper, we have included a graphical description of dimers and tetramers in Chart 1; magnetically inequivalent 6Li nuclei within each aggregate are denoted with black and grey spheres. Both the number and spectral complexity of the aggregates within the ensembles increases markedly with aggregate size. An ensemble of tetramers derived from a mixture of A4 and B4 contain a substantial number of aggregates (five) and an even larger number of discrete resonances (eight). Hexamers manifest enormous spectral complexity due to the proliferation of aggregate stoichiometries and the existence of positional isomers.

Table 1.

Spectroscopically distinguishable aggregates in binary mixtures of lithium enolates A and B.

| aggregation number | AmBn aggregates (ratio of 6Li resonances) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| monomer | A | B | |

| dimer | A2 | AB | B2 |

| tetramer | A4 | A3B1 (3:1) A2B2 (2:2) A1B3 (1:3) B4 | |

| hexamer | A6 | A5B1 (1:2:2:1) | |

| A4B2 (2:2:2) A4B2 (1:2:2:1) A4B2 (2:4) = 3 positional isomersa | |||

| A3B3 (3:3) A3B3 (3:3) A3B3 (1:1:1:1:1:1) = 3 positional isomersa | |||

| A2B4 (2:2:2) A2B4 (1:2:2:1) A2B4 (4:2) = 3 positional isomersa | |||

| A1B5 (1:2:2:1) B6 | |||

Chart 1.

Dimer and tetramer mixtures showing magnetically inequivalent lithium sites.

The populations of homo- and heteroaggregates in Table 1 are described quantitatively by eqs 4-6 where the experimentally measured components are mole fraction of A, XA, and relative NMR resonance integrations, In. The model includes provisions for non-statistical distributions (differing relative stabilities) and forms the foundation for the studies of dimeric and tetrameric enolates (N = 2 and 4) described in the next section.

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

μA and μB = chemical potentials of A and B

gp = free energy of assembly of aggregates with n subunits of A arranged in permutation, p

C = a constant30

XA = mole fraction of enolate A

In = relative integration of aggregate n31

n = aggregate label bearing n subunits of A

N = aggregation number

ϕn = a measure of relative stability of aggregate n

Results

General Methods

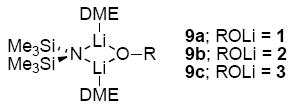

Ensembles of homo- and heteroaggregates derived from binary mixtures of lithium enolates (prepared from [6Li]LiHMDS) present challenges associated with spectral dispersion and resolution. Resolution is optimal when the chemical shift separation of the homoaggregates is large. To this end, a markedly downfield 6Li resonance renders indanone-derived enolate 1 central to the strategy. The line widths and resolution were optimized by adjusting the probe temperature although the origins of the temperature-dependencies were often not obvious. Spectra were also recorded using [6Li,15N]LiHMDS32 to detect LiHMDS-lithium enolate mixed dimers;33 only DME-solvated mixed dimers 9 (of unknown DME hapticity) were detected.34 Enolates 1-3 are structurally homogeneous in TMEDA, THF, and DME as shown by 6Li NMR spectroscopy.35 Studies using mixtures of 1 and 2 as well as 1 and 3 provided analogous results for all solvents, although cyclopentanone-derived enolate 3 is prone to form impurities. Mixtures of 1 and 2 are presented emblematically. All raw data as well as additional NMR spectra and Job plots are provided in supporting information.

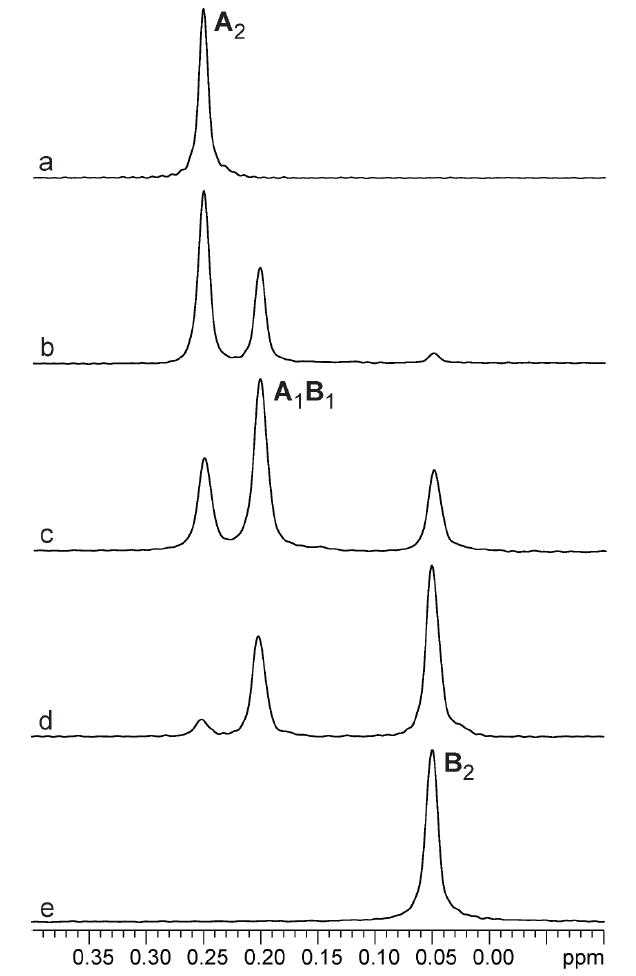

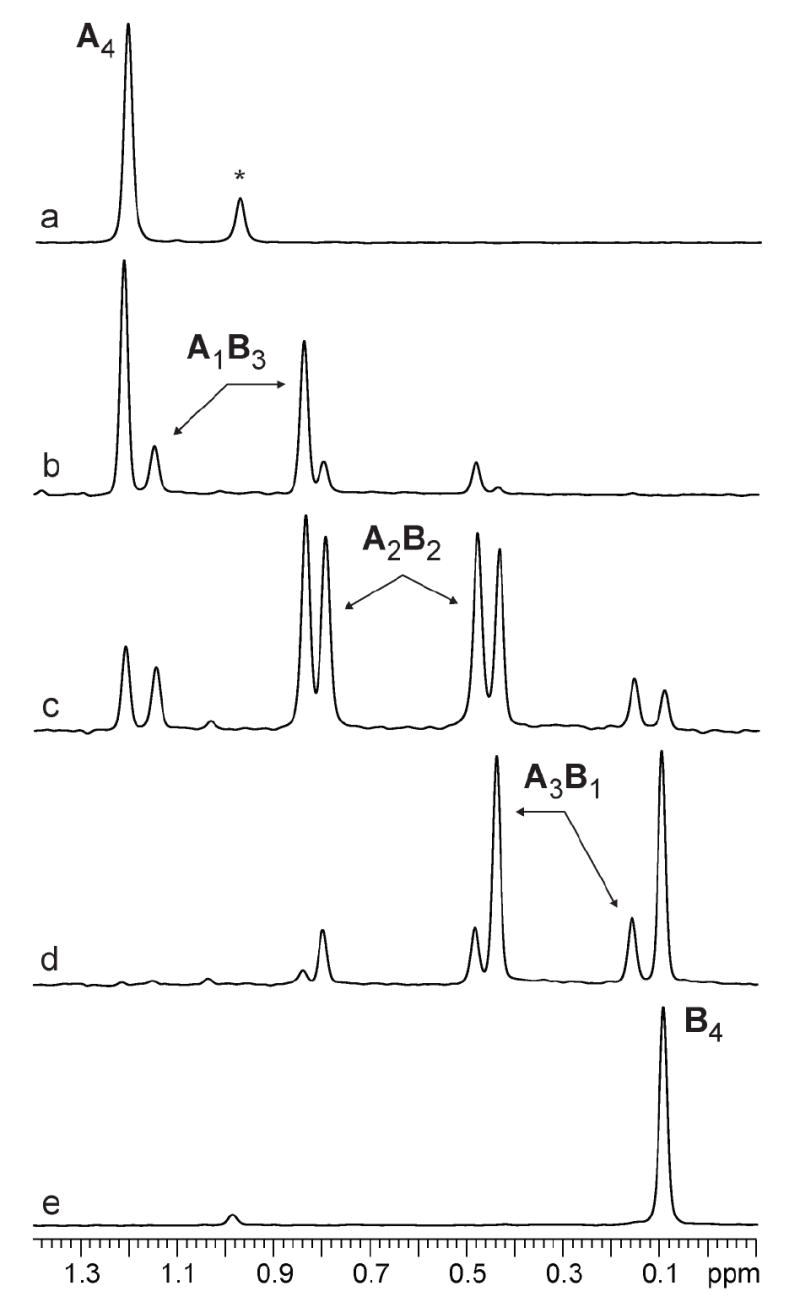

TMEDA

TMEDA-solvated enolates offer the simplest illustration of how the method of continuous variation is used to ascertain aggregate structures. 6Li NMR spectra of mixtures of enolates 1 and 2 reveal the resonances of the homo- and heteroaggregated enolates (Figure 2, LiHMDS monomer36 resonance not shown), consistent with an ensemble of dimers (Table 1 and Chart 1). Plotting relative integrations of the three enolate aggregates versus mole fraction of enolate 2 (X2) affords the Job plot in Figure 3. The curves represent a parametric fit to the data according to eqs 7 and 8. (The ϕn′s in eq 8 derive from eqs 4-6.) The experimental data correlate with a nearly statistical distribution of homo- and heterodimers as illustrated in Figure 4. The aggregate proportions are invariant over a 10-fold range of absolute enolate concentration (0.05-0.50 M), supporting a shared aggregation number for the three species.

Figure 2.

6Li NMR spectra of 0.10 M mixtures of [6Li]1 (A) and [6Li]2 (B) in 1.0 M TMEDA/toluene at -90 °C. a) X2 = 0.0; b) X2 = 0.23; c) X2 = 0.52; d) X2 = 0.79; e) X2 = 1.0.

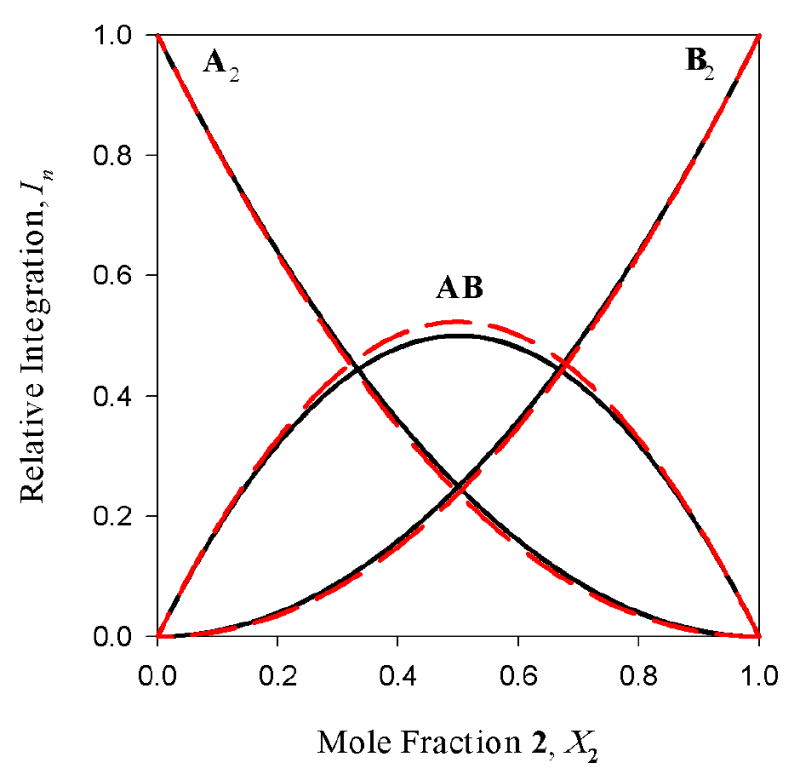

Figure 3.

Job plot showing the relative integrations versus mole fraction of 2 for 0.10 M mixtures of enolates [6Li]1 (A) and [6Li]2 (B) in 1.0 M TMEDA/toluene at -90 °C. From eqs 4-6: ϕ0 = 0.95 ϕ1 = 1.0; ϕ2 = 0.95.

Figure 4.

The best-fit curves from the Job Plot in Figure 3 (dashed lines) overlaid with that expected from a statistical distribution of dimers (solid lines).

| (7) |

| (8) |

Minor deviations of the intended mole fraction from the actual mole fraction can arise from experimental error, non-quantitative enolization, selective formation of mixed aggregates with LiHMDS, or formation of byproducts. Accordingly, we measure the mole fraction by simply integrating the 6Li resonances. A Job plot using measured mole fraction shows a marginal improvement in the parametric fit. We believe, however, that the measured mole fraction is more accurate than the intended mole fraction. We belabor this seemingly trivial point because measuring the mole fraction becomes important in some circumstances (vide infra).

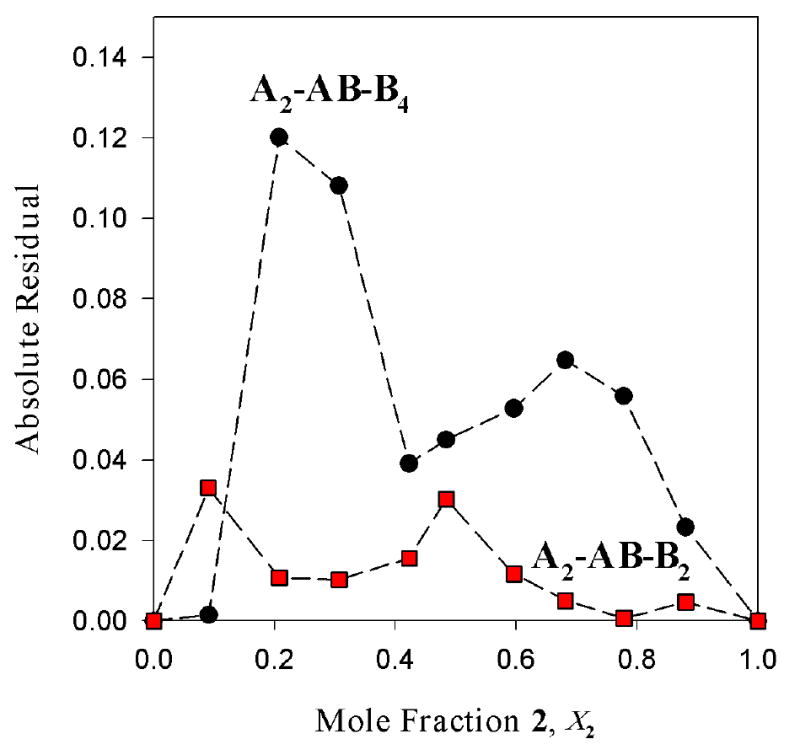

The combination of aggregate count and symmetries as well as the parametric fit attest to the existence of an ensemble of dimers. Is it possible, however, that one of the homoaggregates might not be a dimer? Can we distinguish all-dimer ensemble (A2-AB-B2) from, for example, A2-AB-B4 ensembles wherein one of the homoaggregates is a tetramer? The fit in Figure 5 to the A2-AB-B4 model is inferior to the fit to the A2-AB-B2 model in Figure 4, with the offset of the maximum in the AB curve being most readily apparent. The relative qualities of the fits in Figures 4 and 5 are easily visualized by plotting the sum of the absolute value of the residuals versus mole fraction (Figure 6) showing substantially larger deviations from the A2-AB-B4 model. These analyses are carried out routinely and included as supporting information. Supporting information also includes a considerable number of simulations (hypothetical cases) examining how incorrect models would deviate from the experimental data.

Figure 5.

Job plot showing the relative integrations versus mole fraction of 2 fit to an ensemble of A2-AB-B4 (supporting information) of 0.10 M mixtures of enolates [6Li]1 (A) and [6Li]2 (B) in 1.0 M TMEDA/toluene at -90 °C.

Figure 6.

Absolute residuals versus mole fraction of 2 for the fits of mixtures of enolates [6Li]1 (A) and [6Li]2 (B) in 1.0 M TMEDA/toluene at -90 °C to models based on A2-AB-B4 (●) and A2-AB-B2 ( ). The rms of the sum of the squares of the residuals is 0.005 for the fit to A2-AB-B2 and 0.03 for the fit to A2-AB-B4.

). The rms of the sum of the squares of the residuals is 0.005 for the fit to A2-AB-B2 and 0.03 for the fit to A2-AB-B4.

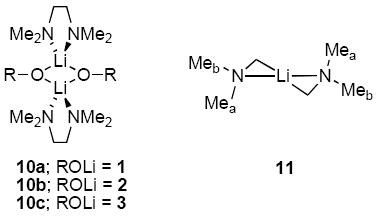

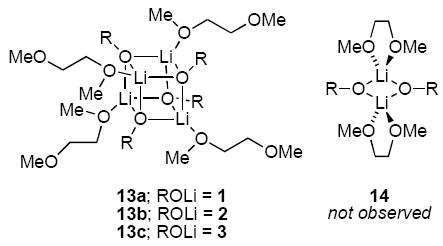

TMEDA-solvated dimers were shown to be doubly-chelated (10) by 13C NMR spectroscopy. Spectra recorded on 0.10 M solution of 1 containing 2.0 equiv of TMEDA reveal free and bound TMEDA in equal proportions as discrete resonances. (Free and η1-bound TMEDA would rapidly exchange, resulting in time averaging of the resonances.37) Further cooling to -90 °C shows decoalescences of the methyl resonances that are highly characteristic of half-chair conformer (11) in slow conformational exchange.35c,38,39 The analogous decoalescences of enolates 2 (and 3) were less convincing.

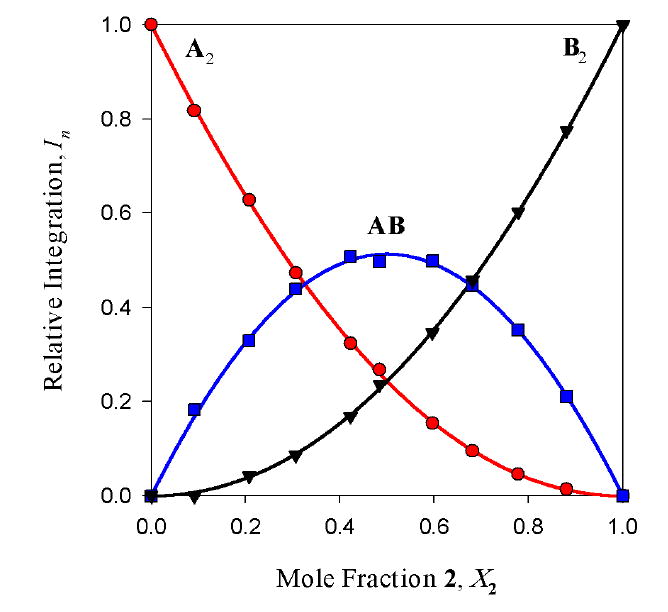

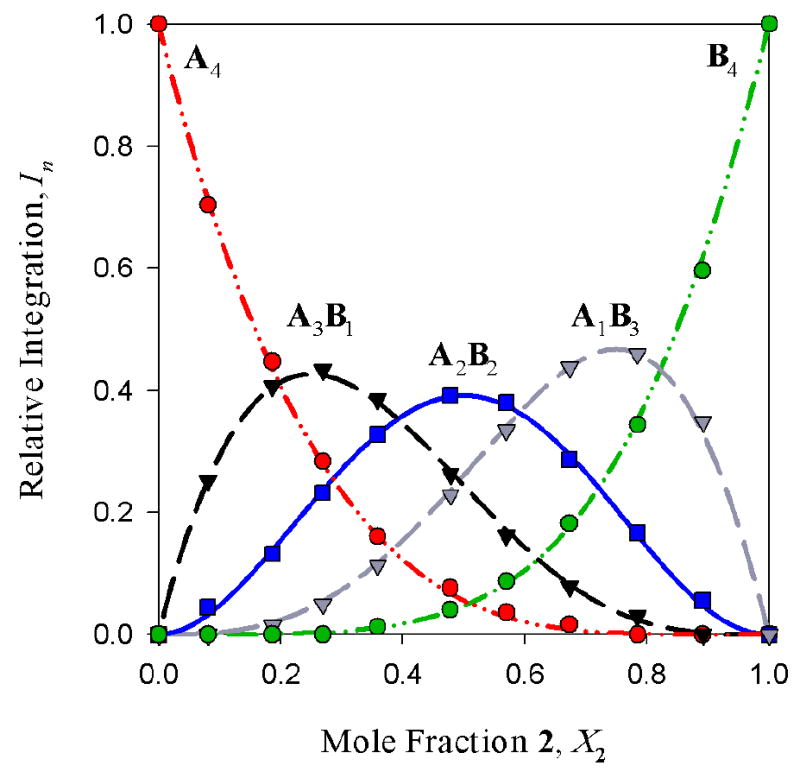

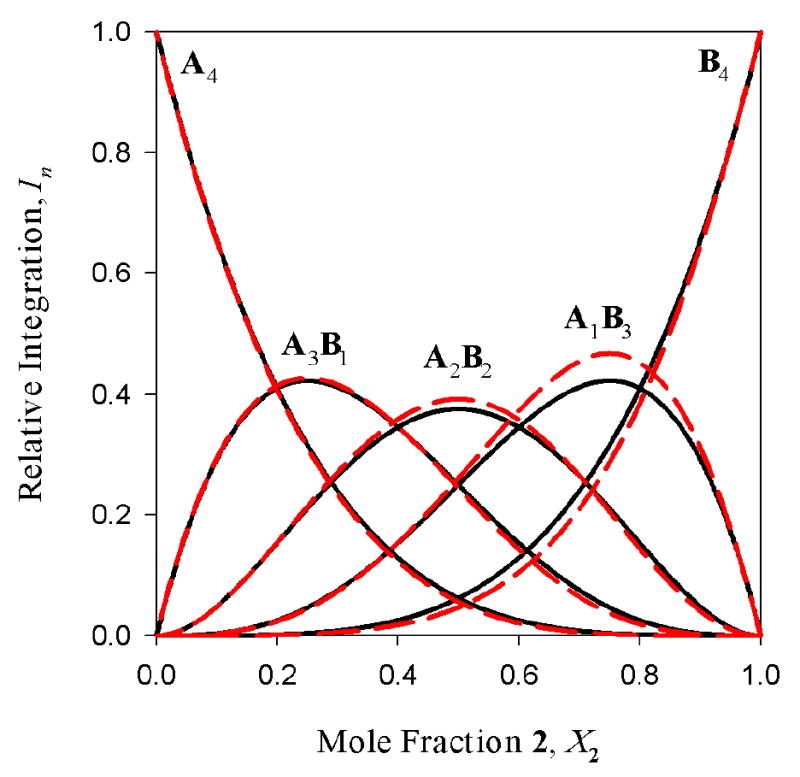

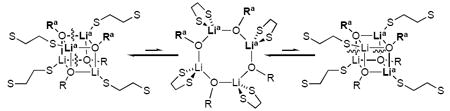

THF

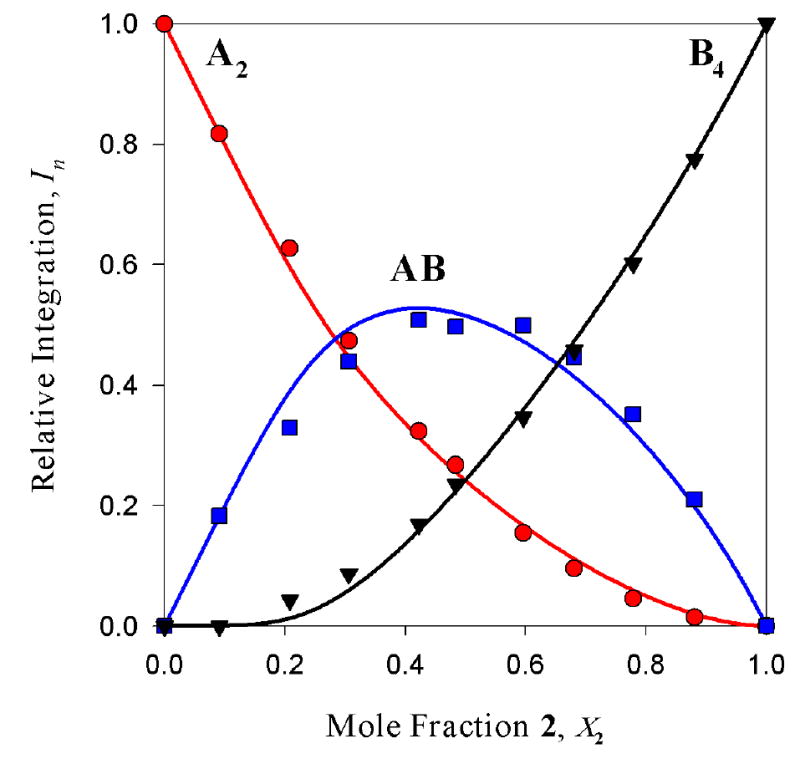

Enolates 1-3 in THF solution are shown to form tetramers 12. By example, 6Li NMR spectra of mixtures of enolates 1 and 2 (Figure 7) reveal the resonances of the two homoaggregates along with three mixed aggregates displaying highly characteristic pairs of resonances in 3:1, 2:2, and 1:3 proportions (Table 1 and Chart 1). Plotting relative integrations of the five aggregates versus measured mole fraction of enolate 2 (X2) affords the Job plot in Figure 8. The curves result from a parametric fit to the data according to eqs 9-14.21 (The ϕn′s in eqs 12-14 derive from eqs 4-6.) The aggregate ratios are invariant over a tenfold range of absolute concentrations, confirming that the three species are of the same aggregation number. A fit to an ensemble comprising four tetramers with one homoaggregated dimer reveals an inferior fit (supporting information). Superimposing the parametric fit in Figure 8 with the results anticipated for a statistical distribution of aggregates reveals a high correlation (Figure 9).

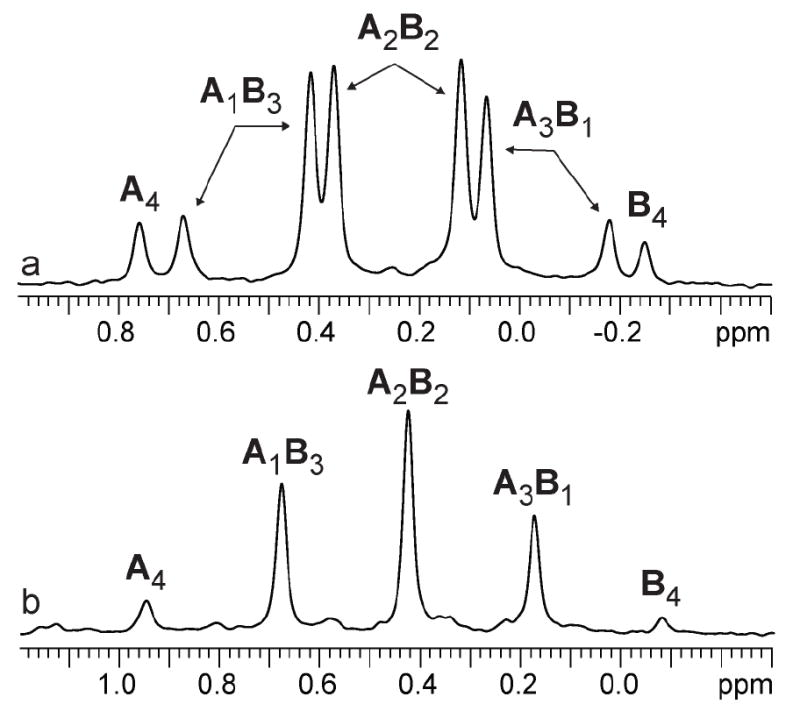

Figure 7.

6Li NMR spectra of 0.20 M mixtures of [6Li]1 (A) and [6Li]2 (B) in 2.0 M THF/toluene at -30 °C. a) X2 = 0.0; b) X2 = 0.19; c) X2 = 0.48; d) X2 = 0.78; e) X2 = 1.0. The * denotes the LiHMDS dimer.

Figure 8.

Job plot showing the relative integrations versus mole fraction of 2 in 0.20 M mixtures of enolates [6Li]1 (A) and [6Li]2 (B) in 2.0 M THF/toluene at -30 °C. From eqs 4-6: ϕ0 = 0.83; ϕ1 = 0.94; ϕ2 = 1.11; ϕ3 = 1.24; ϕ4 = 1.0.

Figure 9.

The best-fit curves from the Job Plot in Figure 8 (dashed lines) overlaid with those expected from a statistical distribution of tetramers (solid lines).

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

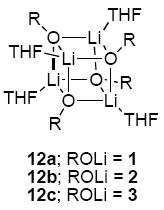

DME

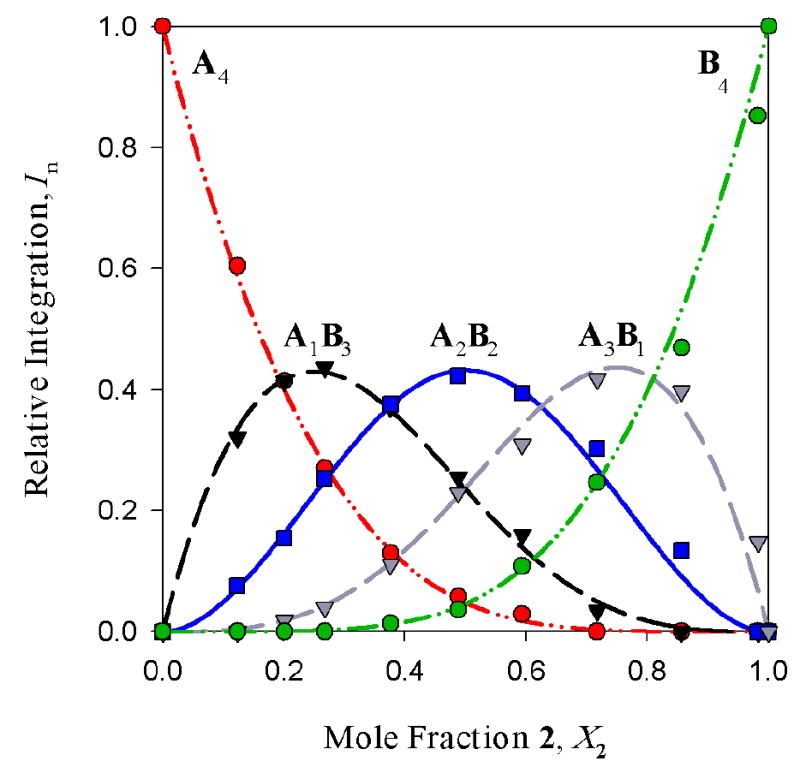

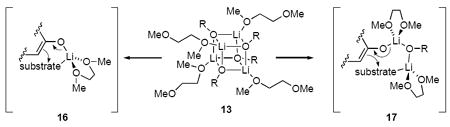

The structural studies of enolates 1-3 in DME proved challenging because of an apparent sensitivity of the enolates (or enolizations). Enolizations using 1.0 equiv of LiHMDS produced considerable impurities. Excess LiHMDS provided enolates cleanly but afforded appreciable concentrations of mixed dimers 9,33,34 which caused resolution problems. Enolate mixtures generated from 1.1 equiv of LiHMDS offered the best compromise. 6Li NMR spectra recorded on mixtures of 1 and 2 as well as 1 and 3 afford resonances characteristic of an ensemble of tetramers (Figure 10a). The resulting Job plots (necessarily using measured mole fraction because of the mixed aggregates and other minor impurities) are fully consistent with nearly statistical distributions (Figure 11). Thus, the enolates form cubic tetramers 13, presumably bearing non-chelated (η1) DME ligands.40 Chelated dimers of general structure 14 were not observed.

Figure 10.

6Li NMR spectra of 0.20 M equimolar mixture of [6Li]1 (A) and [6Li]2 (B) in 2.0 M DME/toluene. a) -105 °C; b) -30 °C.

Figure 11.

Job plot showing the relative integrations versus mole fraction of 2 in 0.20 M mixtures of enolates 1 and 2 in 2.4 M DME/toluene at -105 °C. From eqs 4-6: ϕ0 = 0.70; ϕ1 = 0.99; ϕ2 = 1.26; ϕ3 = 1.29; ϕ4 = 1.0

During efforts to optimize the resolution of the 6Li resonances, we discovered a rapid intraaggregate exchange for DME-solvated enolates--the exchange of 6Li nuclei within each aggregate41--that was not observed for their THF-solvated counterparts. Warming the probe causes the pairs of resonances corresponding to each heteroaggregate to coalesce to a single 6Li resonance--five resonances total (cf. Figures 10a and 10b). A Job plot determined at -30 °C in the limit of fast intraaggregate exchange is essentially indistinguishable from the Job plot in the slow exchange limit. The absence of a temperature dependence is notable (vide infra). A highly speculative mechanism accounting for the facile exchange via a transient cyclic tetramer is provided (eq 15).

|

(15) |

The dynamic phenomenon represented by eq 15 is unique to the DME-solvated enolates and has potentially broader implications. Ligands that readily bind in chelated or non-chelated forms are said to be hemilabile.42 When a transition state is stabilized by chelation whereas the ground state is not, the selective stabilization can afford marked rate accelerations (up to 10,000 fold).43 We suspect, therefore, that reactions of DME-solvated enolates with the standard electrophiles are accelerated by such hemilability (eq 16).

|

(16) |

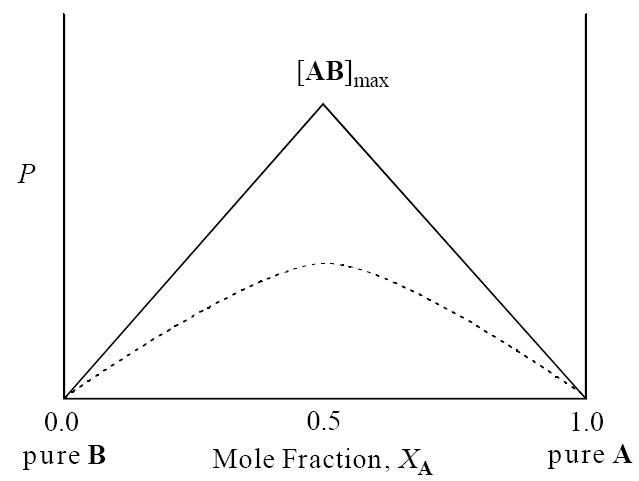

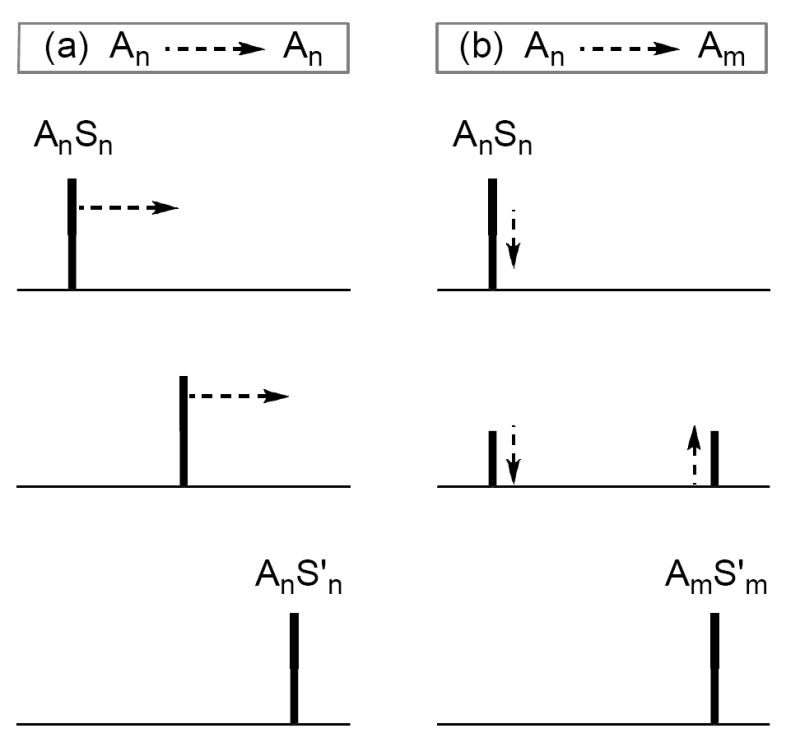

Solvent Swapping

The unexpected absence of DME-chelated dimers prompted us to turn to a simple control experiment that shows whether a change in solvent is accompanied by a change in aggregation.44 The experiment requires a measurable 6Li chemical shift difference in the two limiting forms. It is based on the rapid solvent-solvent exchange (ligand substitution) and much slower aggregate-aggregate exchange.45 By recording a series of spectra in which one coordinating solvent is incrementally replaced by a second, either of two limiting behaviors is observed: (1) If the two observable forms in the two coordinating solvents differ only by ligating solvent, the incremental solvent swap will cause the resonances to exchange by time-averaging (Figure 12a); (2) if the observable forms in the two solvents differ by aggregation number, incremental solvent swap causes one aggregate to disappear and the other to appear (Figure 12b).

Figure 12.

6Li NMR spectra anticipated if replacing solvent S by S’ causes: (A) only exchange of solvent on a common enolate aggregate (An), and (B) an aggregation change (Am for An).

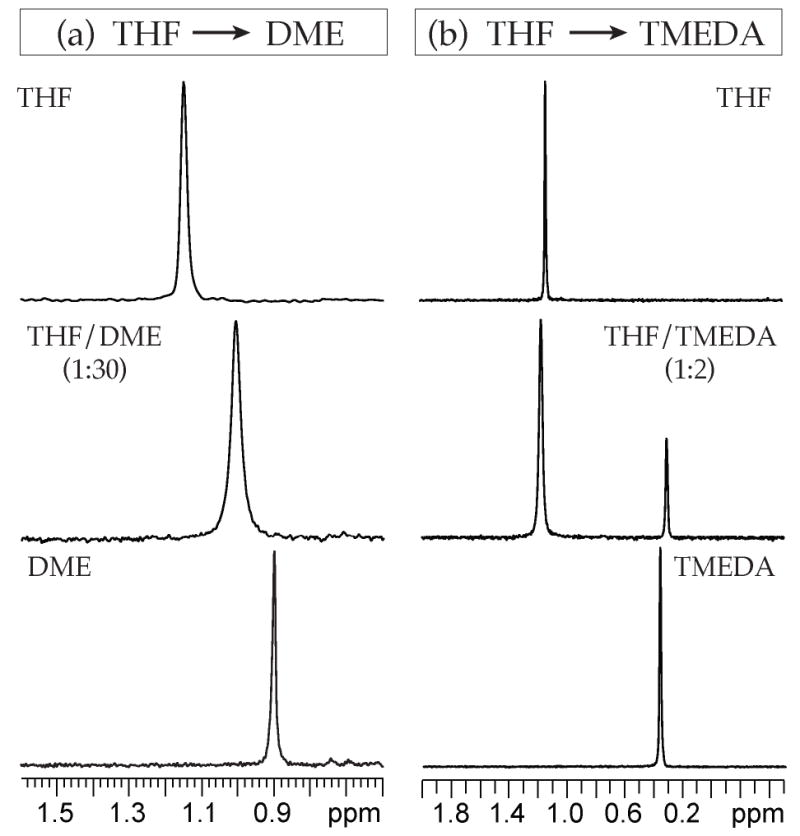

Indanone-derived enolate 1 provides high chemical shift dispersion and offers an excellent illustration of the technique. Substitution of THF with DME reveals only a time-averaged change in chemical shift (Figure 13a), supporting the assignment of enolate 1 as tetramers in both solvents. Conversely, incrementally replacing THF with TMEDA reveals the replacement of one resonance with the other, characteristic of an aggregate exchange (Figure 13b) and supporting the assignments as fundamentally different aggregated forms.46 Similarly, replacing TMEDA with DME showed discrete resonances (behavior as in Figure 12b) consistent with a solvent-dependent change in aggregation number. Moreover, DME only reluctantly converts TMEDA-solvated dimer 10a to DME-solvated tetramer 13a; ≈30:1 DME:TMEDA affords equal populations of the two aggregates.47

Figure 13.

Selected 6Li NMR spectra from solvent swap experiments using 0.10 M [6Li]1 with 3.0 M total ligand/toluene at -90 °C. A) Solvent swap between THF and DME. The mixed solvate is observed at 1:30 ratio of the two solvents. B) Solvent swap between THF and TMEDA. Both aggregation states are observed at a solvent ratio of 1:2.

Discussion

Determining the structure of organolithium species in solution has never been easy, but the problems presented by ketone enolates and related O-lithiated species are acute. Ascertaining the aggregation number invariably reduces to a problem of breaking symmetry.25 In the case of N-lithiated and C-lithiated species, this is most conveniently achieved by observing 15N-6Li and 13C-6Li scalar coupling.27a,48 For O-lithiated species, 17O-6Li coupling is of no practical value.49 We used the method of continuous variation21-25 to characterize enolates 1-3 in TMEDA, THF, and DME. The discussion begins with a synopsis of the method, which is followed by a description of the results. Our primary concern at present, however, is on developing a general solution to the problem. Accordingly, in a third section we critique the method by emphasizing subtleties that may impact future applications.

The Method of Continuous Variation

We determined the structures of lithium enolates by generating an ensemble of heteroaggregated enolates from two homoaggregated enolates (An and Bn) as described generically in eq 3. Two key observations using 6Li NMR spectroscopy--the numbers of aggregates and the symmetries of the heteroaggregates--are highly diagnostic of the standard structural forms (4-7) as described in Table 1 and Chart 1. Plotting relative aggregate integrations versus mole fraction in binary enolate mixtures affords a Job plot as exemplified by Figures 3 and 8. The curves in Figures 3 and 8 correspond to best fits to models based on eqs 4-6. The results for enolates 1-3 are summarized in Scheme 1 and discussed with some literature context as follows.

Scheme 1.

Lithium Enolate Structures

TMEDA, one of the most prevalent ligands in organolithium chemistry,50 has been shown to provide monomers, dimers, tetramers, and other more obscure structural forms.9,13 Although TMEDA shows a penchant for chelation, η1 (non-chelated) TMEDA occasionally arises.51 Crystal structures of lithium enolates reveal a distinct preference for TMEDA-chelated dimers.9,52,53 We find that enolates 1-3 all afford TMEDA-chelated dimers 10 as the only detectable forms in solution. The homo- and heteroaggregates are distributed statistically. Chelation was confirmed by 13C NMR spectroscopy.

A large crystallographic database stemming from seminal studies by Seebach and coworkers suggests that THF-solvated lithium enolates and related O-lithiated species can exist in a number of aggregation states, but THF-solvated tetramers of general structure 12 are the most prevalent.9 Cyclopentanone-derived enolate 3, for example, was one of the first two enolates characterized crystallographically, and it was shown to be tetrameric.35a Structural studies of 3 in solution are controversial. Seebach16c and Noyori18 endorse a model based on mixtures of dimers and tetramers whereas Reich concludes only tetramers exist.19 We concur with Reich; enolates 1-3 form tetramers as the only observable forms in THF.

It may be tempting to assume that DME is simply an oxygen analog of TMEDA. One could imagine the lower Lewis basicity of ethers versus amines is offset by lower steric demands of the ethers.54,55 With that said, considerable evidence suggests that DME is not always a strongly chelating ligand.43,56 DME binds to lithium in either η1 (non-chelating)40 or η2 (chelating)9,13 capacities, depending on the particular environment. With respect to ketone enolates, there is a striking paucity of representation in the crystallographic literature.34,57 We were, however, somewhat surprised to find that enolates 1-3 afford tetramers 13 to the exclusion of the corresponding chelated dimers.

Homoaggregates from Heteroaggregates

The Job plots and affiliated parametric fits are fully consistent with the assignments summarized above. We remind the reader, however, that the primary goal is to exploit an ensemble of heteroaggregates to provide insights into the structures of the homoaggregates. One might question whether the linkage between the heteroaggregates and homoaggregates is strong. As a simple example, could a mixture of homoaggregated dimer and homoaggregated tetramer (eq 17) masquerade as an ensemble of dimers? The accumulated evidence that makes such a scenario unlikely is summarized as follows.

| (17) |

The quality of the fits to the dimer and tetramer models are excellent. If an ensemble contains aggregates of differing overall aggregation numbers (as in eq 17), the Job plot would not be centrosymmetric and would appear so only by coincidence. The nearly statistical distribution of homo- and heteroaggregates certainly supports a shared aggregation number.58

A mixture of homo- and heteroaggregates of differing aggregation numbers would change with absolute concentration; control experiments detect no such concentration dependencies. We hasten to add, however, that the concentration dependencies are technically difficult experiments.

To the extent that a rogue homoaggregate of unique aggregation number results from an enthalpic effect, the equilibrium would be temperature dependent. We detected no such temperature dependencies. By example, mixtures of DME-solvated enolates 1 and 2 afforded Job plots at -30 °C and -105 °C that were indistinguishable.

Chelation of TMEDA in dimers 10a-c detected by 13C NMR spectroscopy convincingly excludes tetrasolvated tetramers, which would demand non-chelated TMEDA ligands.

As illustrated in Figures 12 and 13, replacing one solvent incrementally with another offers a simple test of whether the change in coordinated solvent also causes a change in the aggregation number. Such “solvent swapping” experiments were fully congruent with the assignments.

An ongoing study encompassing a wide array of ketone-, ester-, and carboxamide-derived enolates is allowing us to pair widely disparate enolates to form ensembles. The redundancy ensures that no single enolate is inordinately and anomalously influencing the outcome, and no surprises have appeared yet.59

Conclusion

The studies described above can be distilled to a single concept: Ensembles of homo- and heteroaggregates--the number of discrete aggregates in the ensembles, their characteristic symmetries, and the resulting Job plots--offer a view of spectroscopically opaque homoaggregates. The strategy should apply to a diverse range of lithium enolates in a variety of solvents, and, indeed, this is being pursued. We believe, however, that exploiting ensembles to probe aggregation phenomena could be useful in a much broader context.

Experimental Section

Reagents and Solvents

Substrates are commercially available. TMEDA was recrystallized as the hydrochloride salt prior to distillation.60c TMEDA, THF, and DME were distilled from solutions containing sodium benzophenone ketyl. Hydrocarbon solvents were distilled from blue solutions containing sodium benzophenone ketyl with approximately 1% tetraglyme to dissolve the ketyl. [6Li]LiHMDS and [6Li,15N]LiHMDS were prepared and recrystallized as described previously.32 Air- and moisture-sensitive materials were manipulated under argon using standard glove box, vacuum line, and syringe techniques. Samples for spectroscopic studies were prepared as described in supporting information.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures, raw data, and Job plots. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health and Sanofi-Aventis for direct support of this work.

References and Footnotes

- 1.(a) Green JR. Science of Synthesis. 8a. Georg Thieme Verlag; New York: 2005. pp. 427–486. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schetter B, Mahrwald R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:7506. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Arya P, Qin H. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:917. [Google Scholar]; (d) Caine D. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 1. Pergamon; New York: 1989. p. 1. [Google Scholar]; Martin SF. Ibid. 1:475. [Google Scholar]; (e) Plaquevent J-C, Cahard D, Guillen F, Green JR. Science of Synthesis. Vol. 26. Georg Thieme Verlag; New York: 2005. pp. 463–511. [Google Scholar]; (f) Katritzky Alan R, Taylor Richard JK., editors. Comprehensive Organic Functional Group Transformations II. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 1995. pp. 834–835. [Google Scholar]; (g) Cativiela C, Diaz-de-Villegas MD. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2007;18:569. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dugger RW, Ragan JA, Ripin DHB. Org Process Res Dev. 2005;9:253. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For other applications of lithium enolates in pharmaceutical chemistry see: Farina V, Reeves JT, Senanayake CH, Song JJ. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2734. doi: 10.1021/cr040700c.Wu G, Huang M. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2596. doi: 10.1021/cr040694k.

- 4.(a) Jackman LM, Lange BC. Tetrahedron. 1977;33:2737. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamataka K, Yamada H, Tomioka H. In: The Chemistry of Organolithium Compounds. Rappoport Z, Marek I, editors. Vol. 2. Wiley; New York: 2004. p. 908. [Google Scholar]; (c) Zabicky J. In: The Chemistry of Organolithium Compounds. Rappoport Z, Marek I, editors. Vol. 2. Wiley; New York: 2004. p. 376. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jackman LM, Bortiatynski J. Adv Carbanion Chem. 1992;1:45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Jackman LM, Lange BC. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:4494. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jackman LM, Chen X. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:8681. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jackman LM, Petrei MM, Smith BD. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:3451. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Streitwieser A. J Mol Model. 2006;12:673. doi: 10.1007/s00894-005-0045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Streitwieser A, Wang DZ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6213. [Google Scholar]; (c) Leung SS-W, Streitwieser A. J Org Chem. 1999;64:3390. doi: 10.1021/jo990075p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang DZ, Kim Y-J, Streitwieser A. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10754. [Google Scholar]; (e) Kim Y-J, Streitwieser A. Org Lett. 2002;4:573. doi: 10.1021/ol017175d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kim Y-J, Wang DZ. Org Lett. 2001;3:2599. doi: 10.1021/ol0162872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Streitwieser A, Leung SS-W, Kim Y-J. Org Lett. 1999;1:145. doi: 10.1021/ol990604b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Abbotto A, Leung SS-W, Streitwieser A, Kilway KV. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10807. [Google Scholar]; (i) Leung SS-W, Streitwieser A. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10557. [Google Scholar]; (j) Abu-Hasanayn F, Streitwieser A. J Org Chem. 1998;63:2954. [Google Scholar]; (k) Abu-Hasanayn F, Streitwieser A. J Org Chem. 1996;118:8136. [Google Scholar]; (l) Gareyev R, Ciula JC, Streitwieser A. J Org Chem. 1996;61:4589. doi: 10.1021/jo960013o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Abu-Hasanayn F, Stratakis M, Streitwieser A. J Org Chem. 1995;60:4688. [Google Scholar]; (n) Dixon RE, Williams PG, Saljoughian M, Long MA, Streitwieser A. Magn Reson Chem. 1991;29:509. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The structure and reactivity of lithium enolates during methacrylate polymerizations have garnered considerable attention and has been reviewed: Zune C, Jerome R. Prog Polymer Sci. 1999;24:631. Also, see: Baskaran D. Prog Polym Sci. 2003;28:521.

- 8.A number of physicochemical studies of lithium enolates that do not directly attest to the solution structure of the enolates have been reported. House HO, Prabhu AV, Phillips WV. J Org Chem. 1976;41:1209.Williard PG, Tata JR, Schlessinger RH, Adams AD, Iwanowicz EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:7901.Zook HD, Gumby WL. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:1386.Solladié-Cavallo A, Csaky AG, Gantz I, Suffert J. J Org Chem. 1994;59:5343.Wei Y, Bakthavatchalam R. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:2373.Wei Y, Bakthavatchalam R, Jin X-M, Murphy CK, Davis FA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:3715.Solladié-Cavallo A, Simon-Wermeister MC, Schwarz J. Organometallics. 1993;12:3743.Horner JH, Vera M, Grutzner JB. J Org Chem. 1986;51:4212.Heathcock CH, Lampe J. J Org Chem. 1983;48:4330.House HO, Gall M, Olmstead HD. J Org Chem. 1971;36:2361.Pomelli CS, Bianucci AM, Crotti P, Favero L. J Org Chem. 2004;69:150. doi: 10.1021/jo034587m.Ashby EC, Argyropoulos J. J Org Chem. 1986;51:472.Ashby EC, Argyropoulos JN, Meyer GR, Goel AB. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6788.Ashby EC, Argyropoulos JN. J Org Chem. 1985;50:3274.Ashby EC, Argyropoulos JN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:7.Ashby EC, Park WS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:1667.Zaugg HE, Ratajczyk JF, Leonard JE, Schaefer AD. J Org Chem. 1972;37:2249.Liotta CL, Caruso TC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:1599.Liu CM, Smith WJ, III, Gustin DJ, Roush WR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5770. doi: 10.1021/ja050730c.Cainelli G, Galletti P, Giacomini D, Orioli P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:7383.Yamataka H, Sasaki D, Kuwatani Y, Mishima M, Tsuno Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:9975. doi: 10.1021/jo010003+.Yamataka H, Sasaki D, Kuwatani Y, Mishima M, Tsuno Y. Chem Lett. 1997:271. doi: 10.1021/jo010003+.Mohrig JR, Lee PK, Stein KA, Mitton MJ, Rosenberg RE. J Org Chem. 1995;60:3529.Das G, Thornton ER. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1302.Palmer CA, Ogle CA, Arnett EM. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5619.Das G, Thornton ER. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5360.Partington SM, Watt CIF. J Chem Soc Perkin II Trans. 1988:983.Strazewski P, Tamm C. Helv Chim Acta. 1986;69:1041.Seebach D, Amstutz R, Dunitz JD. Helv Chim Acta. 1981;64:2622.Zook HD, Miller JA., Jr J Org Chem. 1971;31:1112.Vancea L, Bywater Macromolecules. 1981;14:1321.Rathke MW, Sullivan DF. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:3050.Lochmann L, Trekoval J. J Organomet Chem. 1975;99:329.Meyer R, Gorrichon L, Maroni P. J Organomet Chem. 1977;129:C7.Miller JA, Zook HD. J Org Chem. 1977;42:2629.

- 9.Seebach D. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1988;27:1624. [Google Scholar]; Setzer WN, Schleyer PvR. Adv Organomet Chem. 1985;24:353. [Google Scholar]; Williard PG. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Chapter 11 Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 1. Pergamon; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collum DB, McNeil AJ, Ramirez A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;49:3002. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Hsieh HL, Quirk RP. Anionic Polymerization: Principles and Practical Applications. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]; (b) Szwarc M, editor. Ions and Ion Pairs in Organic Reactions. 1 and 2 Wiley; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wardell JL. In: Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry. Chapter 2 Wilkinson G, Stone FGA, Abels FW, editors. Vol. 1. Pergamon; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]; (d) Wakefield BJ. The Chemistry of Organolithium Compounds. Pergamon Press; New York: 1974. [Google Scholar]; (e) Brown TL. Pure Appl Chem. 1970;23:447. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The rate law provides the stoichiometry of the transition structure relative to that of the reactants: Edwards JO, Greene EF, Ross J. J Chem Educ. 1968;45:381.

- 13.(a) Boche G. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1989;28:277. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gregory K, Schleyer PvR, Snaith R. Adv Inorg Chem. 1991;37:47. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mulvey RE. Chem Soc Rev. 1991;20:167. [Google Scholar]; (d) Beswick MA, Wright DS. In: Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry II. Chapter 1 Abels EW, Stone FGA, Wilkinson G, editors. Vol. 1. Pergamon; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]; (e) Mulvey RE. Chem Soc Rev. 1998;27:339. [Google Scholar]

- 14.On two occasions, for example, we have characterized species crystallographically which were not detectable in solution. Kahne D, Gut S, DePue R, Mohamadi F, Wanat RA, Collum DB, Clardy J, Van Duyne G. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:4685.Xu F, Reamer RA, Tillyer R, Cummins JM, Grabowski EJJ, Reider PJ, Collum DB, Huffman JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:11212. Also, see references in Kaufman MJ, Streitwieser A., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:6092.

- 15.(a) Davidson MG, Snaith R, Stalke D, Wright DS. J Org Chem. 1993;58:2810. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dress KR, Rolle T, Wenzel A, Bosherz G, Frommknecht N, Merkel E, Sauer WZ. Physikalische Chem. 2001;215:77. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bauer W, Winchester WR, Schleyer PvR. Organometallics. 1987;6:2371. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cheema ZW, Gibson GW, Eastham JF. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:3517. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnett EM, Moe KD. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:7288.Arnett EM, Fisher FJ, Nichols MA, Ribeiro AA. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:801.Seebach D, Bauer von W. Helv Chim Acta. 1984;67:1972.Shobatake K, Nakamoto K. Inorg Chim Acta. 1980;4:485.den Besten R, Harder S, Brandsma L. J Organomet Chem. 1990;385:153.Halaska V, Lochmann L. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 1973;38:1780.Golovanov IB, Simonov AP, Priskunov AK, Talalseva TV, Tsareva GV, Kocheshkov Dokl Adka Nauk SSSR. 1963;149:835.Simonov AP, Shigorin DN, Talalseva TV, Kocheshkov KA. Bull Acad Sci USSR Div Chem Sci. 1962;6:1056.Armstrong DR, Davies JE, Davies RP, Raithby PR, Snaith R, Wheatley AEH. New J Chem. 1999:35.Nichols MA, Leposa C. Abstracts of Papers; 38th Central Regional Meeting of the American Chemical Society; Frankenmuth, MI. May 16-20, 2006; Washington, D C: American Chemical Society; Lochmann L, Lim D. J Organomet Chem. 1973;50:9.(l) See ref 7 and 8.

- 17.Jackman LM, Scarmoutzos LM, DeBrosse CW. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5355.Jackman LM, Haddon RC. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:3687.Jackman LM, DeBrosse CW. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:4177. Also, see: Quan W, Grutzner JB. J Org Chem. 1986;51:4220.Jackman LM, Rakiewicz EF. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:1202.Jackman LM, Smith BD. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:3829. doi: 10.1021/ja00226a021.

- 18.(a) Suzuki M, Koyama H, Noyori R. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2004;77:259. [Google Scholar]; (b) Suzuki M, Koyama H, Noyori R. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:1571. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Results from Reich and coworkers study of lithium cyclopentenolate are unpublished. Corresponding studies of lithium cyclohexenolate have been reported. Biddle MM, Reich HJ. J Org Chem. 2006;71:4031. doi: 10.1021/jo0522409.

- 20.Pospisil PJ, Wilson SR, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:7585. [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) McNeil AJ, Toombes GES, Gruner SM, Lobkovsky E, Collum DB, Chandramouli SV, Vanasse BJ, Ayers TA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16559. doi: 10.1021/ja045144i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McNeil AJ, Toombes GES, Chandramouli SV, Vanasse BJ, Ayers TA, O’Brien MK, Lobkovsky E, Gruner SM, Marohn JA, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5938. doi: 10.1021/ja049245s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McNeil AJ, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5655. doi: 10.1021/ja043470s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gil VMS, Oliveira NC. J Chem Educ. 1990;67:473. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Job P. Ann Chim. 1928;9:113. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Huang CY. Method Enzymol. 1982;87:509. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)87029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hirose K. J Incl Phenom. 2001;39:193. [Google Scholar]; (c) Likussar W, Boltz DF. Anal Chem. 1971;43:1265. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Galiano-Roth AS, Michaelides EM, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:2658. [Google Scholar]; (b) Reich HJ, Goldenberg WS, Gudmundsson BÖ, Sanders AW, Kulicke KJ, Simon K, Guzei IA. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:8067. doi: 10.1021/ja010489b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gilchrist JH, Harrison AT, Fuller DJ, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4069. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hoffmann D, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:5810. [Google Scholar]; (e) Jacobson MA, Keresztes I, Williard PG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4965. doi: 10.1021/ja0479540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Novak DP, Brown TL. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:3793. [Google Scholar]; (b) Desjardins S, Flinois K, Oulyadi H, Davoust D, Giessner-Prettre C, Parisel O, Maddaluno J. Organometallics. 2003;22:4090. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Günther H. J Brazil Chem. 1999;10:241. [Google Scholar]; (b) Günther H. In: Advanced Applications of NMR to Organometallic Chemistry. Gielen M, Willem R, Wrackmeyer B, editors. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1996. pp. 247–290. [Google Scholar]; (c) Eppers O, Günther H. Helv Chem Acta. 1992;75:2553. [Google Scholar]; (d) Eppers O, Günther H. Helv Chim Acta. 1990;73:2071. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kissling RM, Gagne MR. J Org Chem. 2001;66:9005. doi: 10.1021/jo016105h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.For an early application of a Job plot to assign the stoichiometry of equilibrating titanium alkoxides, see: Weingarten H, Van Wazer JR. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:724.

- 30.We assume that the solution is ideal. For a given species, AnBN-n, C is the concentration at which the activity is equal to 1.21b

- 31.The relative integration (In) was previously referred as aggregate mole fraction (Xn, ref 21). We have changed it to avoid using two, distinctly different mole fraction terms and to include provisions for mixtures of aggregates which are not of the same aggregation number.

- 32.Romesberg FE, Bernstein MP, Gilchrist JH, Harrison AT, Fuller DJ, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:3475. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao P, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14411. doi: 10.1021/ja030168v.Zhao P, Condo A, Keresztes I, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3113. doi: 10.1021/ja030582v.Godenschwager PF, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12023. doi: 10.1021/ja074018m. (d) Also, see ref 21c.

- 34.A LiHMDS-lithium enolate mixed dimer chelated by two DME ligands has been reported. Williard PG, Hintze MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:8602.

- 35.A crystal structure of enolate 3 solvated by THF showing a cubic tetramer has been reported: Amstutz R, Schweizer WB, Seebach D, Dunitz JD. Helv Chim Acta. 1981;64:2617.(b) Crystal structures of enolate 1 solvated by 1,3-dimethyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-21H-pyrimidone DMPU showing a cubic tetramer and by TMEDA showing a doubly-chelated dimer are archived in supporting information.

- 36.Lucht BL, Bernstein MP, Remenar JF, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:10707. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wehman E, Jastrzebski JTBH, Ernsting J-M, Grove JM, van Koten G. J Organomet Chem. 1988;353:145. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fraenkel G, Chow A, Winchester WR. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:1382.Baumann W, Oprunenko Y, Günther H. Z Naturforsch. 1995;50:429.Johnels D, Edlund U. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:1647.(d) Also, see ref 3b.

- 39.6Li NMR spectra recorded on mixtures of 1 and 3 in Me2NEt, a non-chelating analog of TMEDA display a distribution of resonances characteristic of an ensemble of tetramers.

- 40.Hilmersson G, Davidsson O. J Org Chem. 1995;60:7660.Remenar JF, Lucht BL, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5567.Williard PG, Nichols MA. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1568.Barnett NDR, Mulvey RE, Clegg W, O’Neil PA. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1573.Black SJ, Hibbs DE, Hursthouse MB, Jones C, Steed JW. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1998:2199.Bruce S, Hibbs DE, Jones C, Steed JW, Thomasa RC, Williams TC. New J Chem. 2003;27:466.Hahn FE, Keck M, Raymond KN. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:1402.Henderson KW, Dorigo AE, Liu Q-Y, Williard PG. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11855.Deacon GB, Feng T, Hockless DCR, Junk PCJ, Skelton BW, Smith MK, White AH. Inorg Chim Acta. 2007;360:1364.McGeary MJ, Coan PS, Folting K, Streib WE, Caulton KG. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:1723.Coan PS, Streib WE, Caulton KG. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:5019.McGeary MJ, Cayton RH, Folting K, Huffman JC, Caulton KG. Polyhedron. 1992;11:1369.Bochkarev MN, Fedushkin IL, Fagin AA, Petrovskaya TV, Ziller JW, Broomhall-Dillard RNR, Evans WJ. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1997;36:133.Cosgriff JE, Deacon GB, Fallon GD, Gatehouse BM, Schumann H, Weimann R. Chem Ber. 1996;129:953.Deacon GB, Delbridge EE, Fallon GD, Jones C, Hibbs DE, Hursthouse MB, Skelton BW, White AH. Organometallics. 2000;19:1713.Link H, Fenske D. Z Aong Allg Chem. 1999;625:1878.Bonomo L, Solari E, Scopelliti R, Latronico M, Floriani C. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1999:2229.Rosa P, Mezailles N, Ricard L, Le Floch P. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2000;39:1823. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000515)39:10<1823::aid-anie1823>3.0.co;2-5.Iravani E, Neumuller B. Organometallics. 2005;24:842.(t) Also see ref 36.

- 41.(a) Arvidsson PI, Ahlberg P, Hilmersson G. Chem Eur J. 1999;5:1348. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bauer W. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:5450. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bauer W, Griesinger C. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:10871. [Google Scholar]; (d) DeLong GT, Pannell DK, Clarke MT, Thomas RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:7013. [Google Scholar]; (e) Thomas RD, Clarke MT, Jensen RM, Young TC. Organometallics. 1986;5:1851. [Google Scholar]; (f) Bates TF, Clarke MT, Thomas RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:5109. [Google Scholar]; (g) Fraenkel G, Hsu H, Su BM. In: Lithium: Current Applications in Science, Medicine, and Technology. Bach RO, editor. Wiley; New York: 1985. pp. 273–289. [Google Scholar]; (h) Heinzer J, Oth JFM, Seebach D. Helv Chim Acta. 1985;68:1848. [Google Scholar]; (i) Fraenkel G, Henrichs M, Hewitt JM, Su BM, Geckle MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:3345. [Google Scholar]; (j) Lucht BL, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3529. [Google Scholar]

- 42.For reviews of hemilabile ligands, see: Braunstein P, Naud F. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:680. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010216)40:4<680::aid-anie6800>3.0.co;2-0.Slone CS, Weinberger DA, Mirkin CA. Progr Inorg Chem. 1999;48:233.Lindner E, Pautz S, Haustein M. Coord Chem Rev. 1996;155:145.Bader A, Lindner E. Coord Chem Rev. 1991;108:27.

- 43.Ramirez A, Lobkovsky E, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15376. doi: 10.1021/ja030322d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ramirez A, Sun X, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10326. doi: 10.1021/ja062147h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.(a) Qu B, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9355. doi: 10.1021/ja0609654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bernstein MP, Romesberg FE, Fuller DJ, Harrison AT, Williard PG, Liu QY, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:5100. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monodentate ligands have been observed coordinated to lithium ion in the slow exchange limit only rarely and only at very low temperatures. Leading references: Arvidsson PI, Davidsson Ö. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2000;39:1467. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000417)39:8<1467::aid-anie1467>3.0.co;2-i.Sikorski WH, Reich HJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6527. doi: 10.1021/ja010053w.(c) See ref 48.

- 46.In the event that TMEDA- and THF-solvated dimers coexist, the 6Li resonances would undergo very rapid exchange even at low temperatures. See ref 36.

-

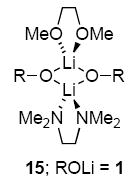

47.At low total solvent concentration (2.0 equiv per lithium) traces of TMEDA/DME mixed-solvated dimmer 15 is observed as a 1:1 pair of 6Li resonances <-115 °C. At high total solvent concentration (30 equiv per lithium). we observe time averaged dimer resonance that depends markedly on TMEDA/DME proportions, which is also consistent with mixed solvation.44

- 48.Collum DB. Acc Chem Res. 1993;26:227.Lucht BL, Collum DB. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:1035.(c) See ref 27a for leading references to 6Li-13C coupling.

- 49.The rapid relaxation of the highly quadrupolar 17O nucleus would preclude observing 6Li-17O coupling.

- 50.Snieckus V. Chem Rev. 1990;90:879.Clayden J. Organolithiums: Selectivity for Synthesis. Pergamon; New York: 2002. Langer AW Jr, editor. Polyamine-Chelated Alkali Metal Compounds. American Chemical Society; Washington: 1974. Collum DB. Acc Chem Res. 1992;25:448.

- 51.Bauer W, Klusener PAA, Harder S, Kanters JA, Duisenberg AJM, Brandsma L, Schleyer PvR. Organometallics. 1988;7:552.Köster H, Thoennes D, Weiss E. J Organomet Chem. 1978;160:1.Tecle’ B, Ilsley WH, Oliver JP. Organometallics. 1982;1:875.Harder S, Boersma J, Brandsma L, Kanters JA. J Organomet Chem. 1988;339:7.Sekiguchi A, Tanaka M. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12684. doi: 10.1021/ja030476t.Linnert M, Bruhn C, Ruffer T, Schmidt H, Steinborn D. Organometallics. 2004;23:3668.Fraenkel G, Stier M. Prepr Am Chem Soc Div Pet Chem. 1985;30:586.Ball SC, Cragg-Hine I, Davidson MG, Davies RP, Lopez-Solera MI, Raithby PR, Reed D, Snaith R, Vogl EM. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1995:2147.(i) See ref 37 and 43a,c,h.

- 52.TMEDA-solvated enolates that are not dimmers Henderson KW, Dorigo AE, Williard PG, Bernstein PR. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:1322.

- 53.A solvent-free hexameric imidate crystallizes from solutions containing TMEDA: Maetzke T, Seebach D. Organometallics. 1990;9:3032.

- 54.For early discussions of steric effects on solvation and aggregation, see: Settle FA, Haggerty M, Eastham JF. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:2076.Lewis HL, Brown TL. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:4664.Brown TL, Gerteis RL, Rafus DA, Ladd JA. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:2135. For a discussion and more recent leading references, see ref 33a.

- 55.Discussion of cone angle and steric demands of trialkylamines: Seligson AL, Trogler WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:2520.Choi M-G, Brown TL. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:1548.

- 56.Remenar JF, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5573. [Google Scholar]

- 57.We can find no examples of crystallographically-characterized homoaggregated lithium enolates solvated by DME. There are examples of the isostructural lithium aryloxides displaying a tendency to form doubly-chelated dimers. See, for example: Cole ML, Junk PC, Proctor KM, Scott JL, Strauss CR. Dalton Trans. 2006:3338. doi: 10.1039/b602706g.. Also, see 40e,f.

- 58.We hasten to add that a non-statistical distribution does not necessarily attest to differentially aggregated forms. In the case of sterically crowded aggregates, significant departure from statistical behavior (showing up as an unusual preference for mixed aggregation, for example) would not be surprising.

- 59.Liou LR, Gruver JM, Collum DB. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- 60.(a) Freund M, Michaels H. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1897;30:1374–8. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chadwick ST, Rennels RA, Rutherford JL, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:8640. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rennels RA, Maliakal AJ, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:421. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures, raw data, and Job plots. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.