Abstract

We recorded single hippocampal cells while rats performed a jump avoidance task. In this task, a rat was dropped onto the metal floor of a 33 cm gray wooden cube and was given a mild electric shock if it did not jump up onto the box rim in <15 s. We found that many hippocampal pyramidal cells and most interneurons discharged preferentially at the drop, the jump, or on both events. By simultaneously recording the hippocampal EEG, we found that the discharge of most of the event-related pyramidal cells was modulated by the theta rhythm and moreover that discharge precessed with theta cycles in the same manner seen for pyramidal cells in their role as place cells. The elevations of firing rate at drop and jump were accompanied by increases in theta frequency. We conclude that many of the features of event-related discharge can be interpreted as being equivalent to the activity of place cells with firing fields above the box floor. Nevertheless, there are sufficient differences between expectations from place cells and observed activity to indicate that pyramidal cells may be able to signal events as well as location.

Keywords: hippocampus, place cells, theta rhythm, acetylcholine, jump avoidance, memory

Introduction

Although previous work on the activity of hippocampal neurons in freely moving rats investigated time locking of their discharge to the occurrence of particular behavioral events (Ranck, 1973), conditioning components (Berger and Thompson, 1976) or sudden stimuli (Lin et al., 2005), the focus of recent studies has been on recordings during spatial tasks without obvious synchronizing events (O'Keefe, 2007). We therefore revisited the question of whether signals can be detected in hippocampal cell discharge at the moment of important events and, if so, whether such signals can be distinguished from place cell activity.

For this purpose, rats were taught a jump avoidance task previously used to characterize the relationship between motor activity and the theta rhythm (Vanderwolf, 1969; Vanderwolf and Cooley, 1974; Bland et al., 2006). In this task (see Fig. 1), a rat is dropped into a box and mildly shocked 15 s later unless it first jumps onto the box rim. Each trial starts when the rat is dropped into the box and ends when it jumps out, either soon enough to avoid the shock or later to escape continued shocks. In this way, it is possible to time lock single hippocampal cell discharge and the hippocampal EEG to two brief, important events. In this design, the interval between release and landing is constant and slightly longer than the constant interval between jump and arrival on the rim so that speed variations typical of running are minimized. We also looked for EEG frequency increases at jump time, as expected from previous work (Vanderwolf, 1969; Bland et al., 2006) and for possible changes at drop time. Moreover, single-cell and EEG recordings were combined to see whether the phase precession characteristic of place cell firing during locomotion through firing fields on a linear track (O'Keefe and Recce, 1993; Harris et al., 2002; Huxter et al., 2003; Zugaro et al., 2005; Geisler et al., 2007) or in an open region (Skaggs et al., 1996) was observed.

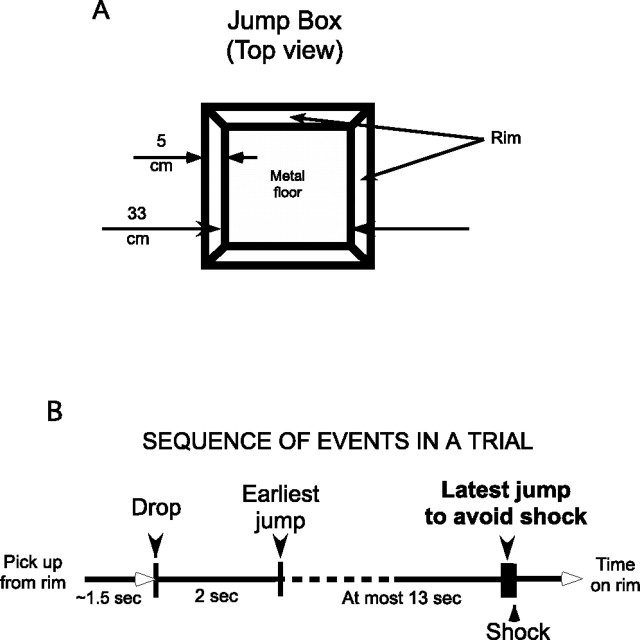

Figure 1.

Jump apparatus and trial description. A, Overhead view of the jumping box. The box is a 33 cm cube with a metal floor and a square rim 5 cm in width that the rat lands on when it jumps from the bottom. Shocks are delivered by a circuit between the metal floor and a subdermal wire implanted during surgery. B, Trial protocol. At the start of each trial except the first, the rat is picked up from the rim and dropped ∼1.5 s later onto a preselected location on the box floor. If the rat jumps out in <2 s, it is immediately dropped back into the box. If it jumps out with a latency >2.0 s and <15 s, it receives no shock on that trial. It is then allowed to spend ∼1 min on the rim before the next trial begins. After the last trial, it is returned to its home cage. If the rat does not jump within 15 s after the drop, a series of shocks are delivered at 0.5 s intervals. A total of 40 trials are given over ∼1 h.

In addition to recording during the jump task, we measured location-specific firing in two circumstances, as rats walked on the box rim between trials and as they chased food pellets on an elevated disk. We could therefore compare the fraction of cells that discharge strongly in each situation (the “active subset”) (Muller et al., 1991) and ask whether an individual cell with a strong discharge correlate in one situation was more or less likely to have a strong discharge correlate in one of the other situations. Population statistics were another way of comparing putative event-related firing with location-specific firing.

Overall, our results conform to many expectations derived from the spatial mapping view of hippocampal function. Specifically, if we take into account the speed at which the rat moves during drop and jump, our phase precession results agree with the idea that place cells reflect the operation of speed-controlled oscillators (Geisler et al., 2007). Nevertheless, we find several departures of pyramidal cell activity from the ideal place cell model that require a more complex description.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Sixteen Long–Evans hooded male rats (Charles River Laboratories) were used. They were initially housed one per cage on a natural light/dark cycle in a temperature-controlled room (20 ± 2°) with ad libitum access to food and water. Starting 1 week after arrival, they were handled daily for 1 week and food deprived to 85% of ad libitum body weight. They were then trained in the “pellet-chasing” task in the disk for 1 week and in the “jump avoidance” task for 2 weeks. One rat was removed from consideration because histology revealed an extensive lesion in the parietal cortex.

Tasks

Pellet chasing.

To provide a reference for the activity of CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells in the jump avoidance task, hungry rats were trained to forage for 25 mg food pellets randomly scattered at ∼0.33 Hz onto the surface of a 82-cm-diameter metal disk. The disk had a 5 cm rim, was elevated 70 cm above the room floor, and was otherwise open so the rat could view the complex stimuli in the 3 × 3 m recording room.

During initial sessions, rats tended to remain still but with experience moved constantly over the disk so that, after 1 week, they visited the entire floor in a few minutes and covered the accessible area several times in 12 min sessions. This behavior allowed us to estimate the time-averaged firing rate everywhere in the apparatus. Although we did not make numerical comparisons, firing rate maps (see below) on the disk and in the 76-cm-diameter cylinder used in previous work (Lenck-Santini et al., 2002) were indistinguishable. As soon as rats explored the whole apparatus and ate all pellets available during a session, they were trained in the jump avoidance task.

Jump avoidance.

This task was used previously to explore the relationship of hippocampal theta to sudden movement (Vanderwolf, 1969). In the version of jump avoidance used here, a rat was dropped from ∼38 cm into a 33 cm cubic box whose floor was equipped to deliver mild shocks (specified below) that began 15 s after the drop. To prevent or terminate shocks, the rat had to make a vertical leap of 33 cm onto a 5-cm-wide ledge with a 5-cm-high wall at the top of the box (Fig. 1). The events between drop and landing on the ledge are a trial. The rat was left on the ledge for 1 min at the end of each trial to eat previously scattered food pellets. Thus, a trial lasted ∼1 min 15 s. In a typical day, rats were given 40 trials in a session that lasted ∼1 h. We tracked rats during the 1 min intertrial intervals and accumulated position and discharge data so that we could observe location-specific firing in this circumstance as well as on the disk.

During the first 2 d of jump avoidance training, a lid was put on the box to prevent access to the floor. Rats were allowed to roam the box rim eating previously scattered food pellets, something they were used to from previous experience on the disk.

On the third day, the rats were allowed 2–3 min on the ledge and were then picked up and dropped onto the box floor. On this first trial, rats routinely remained in the box for 15 s and therefore received at least one shock. If the rat did not jump after the first shock, additional shocks were given every 2 s until a jump was made. The rat was said to “escape” on trials in which the jump was made after at least one shock was delivered; the rat was said to “avoid” on trials in which the jump was made in <15 s, before any shocks were delivered. In this initial phase, the rat was allowed 2–3 min on the ledge before the next drop. After several trials, the rat began to avoid. After 3–4 d, the rat generally avoided on 90% of the trials and the second training phase was started.

In the second phase, the rat was taught to remain stationary after the drop for at least 2 s before jumping. This behavior was obtained by reducing the amount of food and the rest time on the ledge if the rat moved before jumping or by increasing the amount of food and the rest time on the ledge if the rat stayed still before jumping. Thus, training had both appetitive and aversive components. Phase 2 consisted of 5 d of two training sessions per day. At the end of phase 2, rest time on the rim was set to 1 min if the rat stayed still; if it jumped out in <2 s, it was immediately dropped back into the box with no rest. To make it possible to sample behavior, cell activity, and the EEG from different positions, rats were dropped randomly into one of the four corners of the box on each trial. Most rats stayed at the drop position for >2 s and jumped onto the closest rim corner. In a few cases, however, the rat walked from the drop corner to a preferred corner and then jumped. In these cases, minimal pre-jump movement was established by usually dropping such a rat into its preferred corner. If drops into a different corner were rare enough, the rat would remain still before jumping to the nearest corner.

Equipment

The system combines video-based tracking of the rat's location, means to determine the drop, and jump times of a trial, a method of controlling shock delivery and an electrophysiology recording setup. The subsystems were connected to ensure correct synchronization of all events.

Detection of drop and jump times.

An accelerometer was used to determine when the rat was dropped into the box and when it jumped out. The accelerometer was attached below the metal plate that formed the bottom of the box. The plate extended 8 cm beyond each side of the box with its corners resting on 3 cm wood cubes. This arrangement reduced the rigidity of the apparatus sufficiently that either drop or jump produced an easily detected accelerometer signal. The accelerometer output was recorded on a continuous electrophysiological channel (2 kHz sampling rate) and in parallel sent to a Schmitt-trigger threshold detector. To start a trial, the experimenter reset the threshold detector and the rat was dropped. When the rat landed, the accelerometer signal triggered the threshold detector that in turn illuminated a red light-emitting diode (LED) on the box edge. Detection of the LED at its x–y position was used to start the shock-timing clock.

Shock sequence.

The shock sequence consisted of a 15 s delay after LED detection, followed by a 0.5 Hz foot-shock train that continued until the rat jumped onto the ledge. Each shock was a 100 ms series of five unipolar pulses, 20 ms in duration, whose intensity was between 0.1 and 0.5 mA. The shock amplitude was adjusted so that the rat reliably showed a reaction that included scratching, rearing, startle, exploration, or jumping. The constant current was applied between the metal box floor and a subcutaneous wire brought out through the neck skin; when the rat was hooked up, the neck electrode was attached to one side of the constant-current stimulator. The metal floor was connected to relays that allowed connection to either the other end of the stimulator during shocking or to the head-stage amplifier ground during actual recording. Thus, recordings were continuous except for the 100 ms shock series.

Electrode implantation

Surgery was performed when the rats were fully trained and avoided shock on 95–100% trials. Before surgery, rats were injected with atropine sulfate (0.25 mg/kg) to prevent respiratory distress and then anesthetized with Nembutal (45 mg/kg). The scalp was shaved, and the rat was put in a David Kopf Instruments stereotaxic instrument. A midline scalp incision was made, and the bone surface was cleaned. Miniature screws were placed above both olfactory bulbs and the right cerebellar hemisphere. A 2-mm-diameter hole was drilled above the left hippocampus centered at coordinates anteroposterior −3.8 mm and lateral −3.0 mm using the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1997).

The dura was cut, and the electrodes were lowered to dorsoventral −1.5 mm for subsequent placement (see below). The locally manufactured implant array had six independently drivable tetrodes (four twisted 25 μm wires) for single-cell recordings and two separately drivable 100 μm single-wire EEG electrodes. A ground wire was soldered to one of the miniature screws. The implant was secured to the skull and the screws with dental cement. Finally, the wounds were sutured and covered by antibiotic ointment. Rats were allowed 1 week to recover.

Electrode placement

After recovery, both EEG electrodes were moved down equally until clear theta activity was detected on each. One of the electrodes was then lowered three additional screw turns (750 μm) so that the two electrodes straddled the CA1 cell layer. This procedure generally yielded large EEG signals with the peak-to-peak theta amplitude >1 mV. The tetrodes were lowered during screening sessions on the disc until several of them showed pyramidal cell activity (criteria stated below), at which point formal recordings were started.

Recording sequence

Once several cells were detected, the following recording sequence was done: (1) session 1, pellet chasing on the disk (16 min); (2) session 2, jump avoidance task (30 min; 30–45 jumps); (3) in some instances, intraperitoneal scopolamine injections (1 mg/kg) were made just after session 2; the rat was left in its cage for 1 h and two additional sessions were performed; (4) session 3, jump avoidance task (30 min; 30–45 jumps); and (5) session 4, pellet chasing on the disk (16 min).

Data acquisition

Screening and recording were done with a cable connected to the rat's head stage. The head stage plugged into the implant and contained a X1 gain operational amplifier for each channel plus two LEDs for tracking the rat's head position. For tracking, the LEDs were located at 60 Hz in an array of pixels 1.7 cm on a side during pellet chasing on the rim of the jump avoidance box and at its bottom. The signal from each wire was amplified 10,000×, bandpass filtered, and digitized (0.3–10 kHz filtering and 32 kHz sampling frequency for unit electrodes; 0.1–300 Hz filtering and 2 kHz sampling frequency for EEG electrodes and the accelerometer). The digitized electrophysiological and accelerometer data were stored on a computer along with position information extracted by iTrack software (Bio-Signal Group) from buffers acquired with a frame grabber (DT3155; Data Translation). The tracking and electrophysiological data were acquired with a single computer using two time-sharing programs that were synchronized by recording the vertical start-of-field pulse from the camera on a channel digitized at 2 kHz.

Analyses

Spike separation.

Cell discrimination was performed off-line with a cluster-cutting program written by A. A. Fenton (Wclust). This program allows selection of displayed action potential waveforms according to voltage at different time points for each tetrode wire. Other parameters such as waveform energy and principle components can be extracted from waveform shape and used in clustering. Only cells with a peak spike amplitude of at least 200 μV on at least one tetrode wire were taken into consideration.

Standard methods (Ranck, 1973; Kubie et al., 1990) used to distinguish pyramidal cells and interneurons (theta cells) were as follows. (1) The duration of the initial negative-going peak of the extracellular waveform was between 300 and 500 μs for pyramidal cells and <250 μs for interneurons. (2) The time-averaged firing for pyramidal cells was <3.0 spikes/s and for interneurons >20.0 spikes/s. (3) Pyramidal cells generated complex spikes (action potential bursts with interspike intervals <5 ms and decrementing amplitude); interneurons never fired complex spikes.

Coherence.

Coherence is a nearest-neighbor two-dimensional autocorrelation quantity that measures the degree of organization of a spatial firing pattern (Kubie et al., 1990). Coherence is computed in two steps. First, the product–moment correlation is found between the firing rate in each pixel and the average of the rates in its nearest neighbors. Second, the z-transform of the correlation is taken.

Place cell selection.

A firing field was defined as a set of at least nine contiguous pixels in which the firing rate was above the grand mean rate. A pyramidal cell with at least one firing field and coherence >0.3 was considered a place cell.

Visualization of spatial firing patterns.

Autoscaled color-coded firing rate maps were created to visualize positional firing rate distributions (Muller and Kubie, 1987). In such maps, pixels in which no spikes occurred during the whole session are displayed as yellow. Greater-than-zero rates are coded in the color order orange, red, green, blue, and purple.

EEG analyses.

To analyze the evolution of theta activity before the jump, local hippocampal field potentials were filtered in the theta band (5–12 Hz). Because we wanted to study immobility-related theta, only trials in which the rat did not move before the jump were considered. A rat was judged to move if it visited more than five pixels in the 2 s preceding the jump.

Phase precession in the jumping task.

To determine theta phase, peaks and troughs were detected in the filtered EEG signal. The phase at each peak was considered to be 0° and at each trough 180°. Each half theta cycle was then divided into 10 equal time segments so that resolution was 18°. The temporal precession rate was obtained by first plotting the phase of each spike against time; only cells that fired >100 spikes as the phase changed over a range of at least 120° were considered. Next, the circular–linear correlation coefficient and its probability (Fisher, 1993) were computed for each cell. Cells with a correlation significance p < 0.05 were considered to show a significant phase–time correlation. The slope of the temporal precession rate was estimated by least-squares fit.

Perievent time rasters and histograms.

Pyramidal cell firing relative to the task events (drop or jump) was assessed by constructing perievent time rasters and histograms. In each trial, the spike activity of the cell was determined relative to the time of either the drop or the jump. This is done by subtracting the time stamp of each spike from the time of the “aligning event.” In a raster (see Figs. 2–6), each trial is represented on a horizontal time line, and each spike is represented by a vertical black line at the appropriate distance from the aligning drop or jump event. The time of the second, nonaligning event is shown with a red dot. A separate raster plot is made for each cell for both the drop and jump. Perievent time histograms are made by summing aligned spikes for all trials into 100 ms bins. Drop histograms are made starting 2 s before the drop until 10 s afterward. Jump histograms are made starting 10 s before the jump until 2 s afterward.

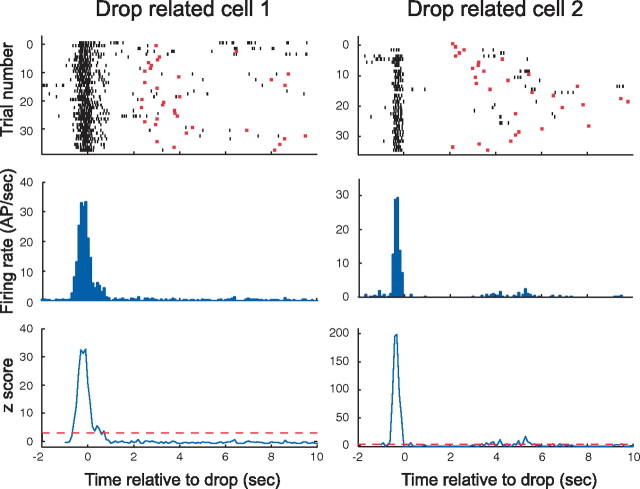

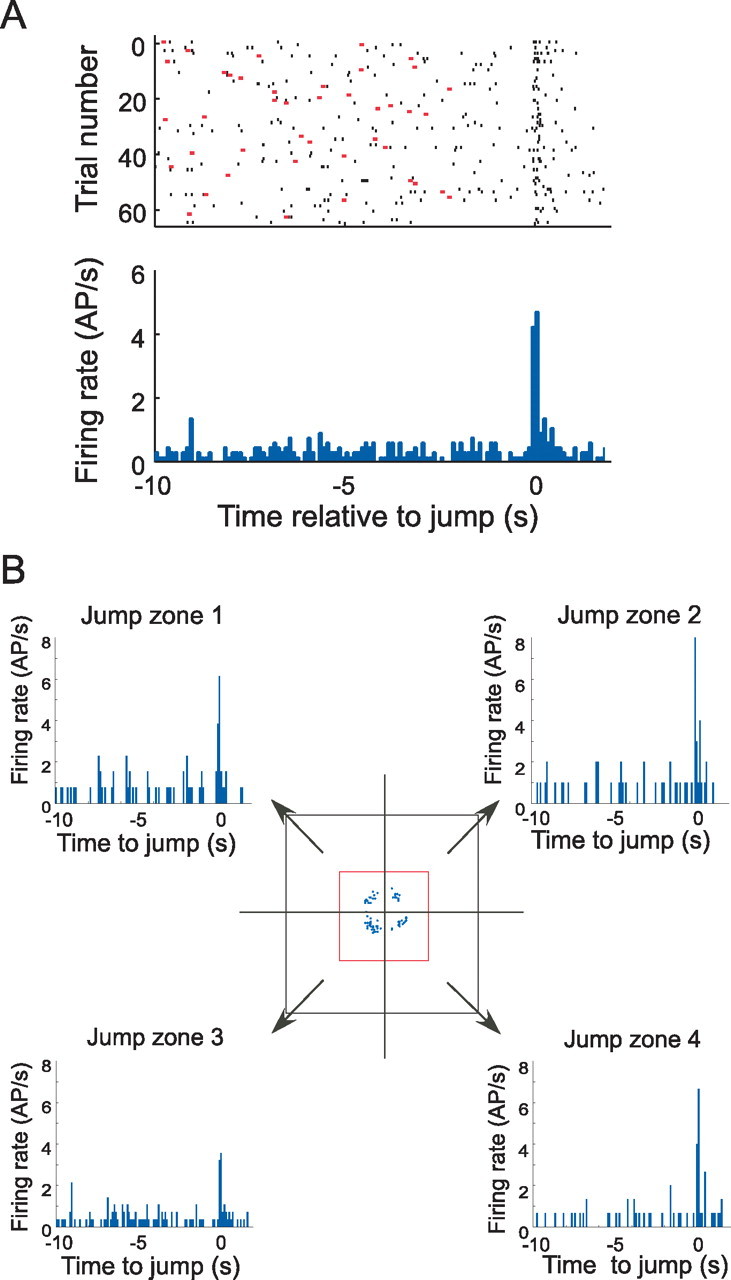

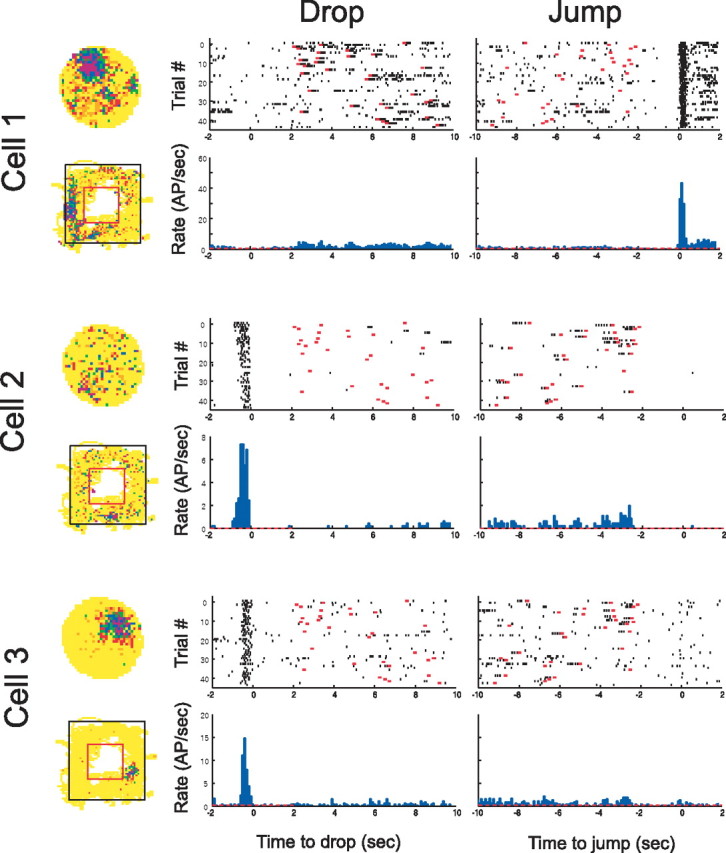

Figure 2.

Two pyramidal cells that discharge when the rat is dropped. The temporal firing pattern of each cell is plotted in three ways on a time base relative to the moment the rat lands on the box floor. The top row contains raster displays of discharge during ∼35 trials. Each short vertical black line indicates the time of an action potential (AP). The moment at which the rat jumped on each trial is marked with a red bar. Justification for calling these cells “drop related” is evident from the dense band of action potentials near t = 0 and the scarcity of action potentials at other times. The strong synchronization of discharge to the drop event is also evident from the histograms in the middle row in which each bar is the firing rate in a 100 ms bin. A statistical indication of firing specificity is given in the bottom row in which the z-score in each bin is plotted against time. The z-score is derived by comparing the rate in each bin with the rate averaged over the interval from 1 s after the drop to 1 s before the jump across all trials (see Materials and Methods). Note that the z-scores near the peaks are associated with infinitesimal probabilities that the peak rate is equal to the background rate. Although the properties of the two cells are quite similar, two interesting differences should be noted. First, cell 1 fires over an interval of ∼1.5 s, whereas the discharge of cell 2 is considerably briefer. Second, cell 1 is active before, during, and after the drop, whereas the activity of cell 2 ceases before landing.

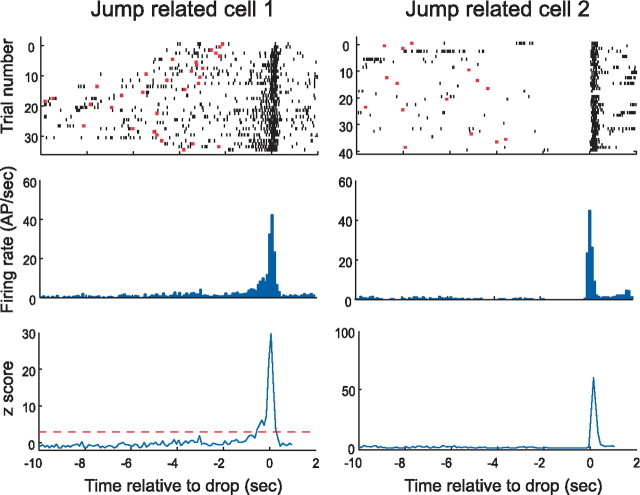

Figure 3.

Two pyramidal cells that discharge when the rat jumps. The arrangement of the panels is identical to Figure 2, except that t = 0 is now set to the moment at which the rat jumps. In the raster plots of the top row, this means that the red bars now represent the moment at which the rat is dropped. Justification for referring to such cells as “jump related” is evident from the dense action potential (AP) bands near t = 0. From the histograms, it is seen that the peak firing rate of both cells is very high (>40 spikes/s) and that the duration of rapid firing is quite brief (<0.5 s). Note also that there is a gradual increase in the discharge of cell 1 for ∼1 s before the jump. In contrast, cell 2 appears to be especially quiet in the same interval. The plots of z-score against time in the bottom row once again emphasize the extremely tight confinement of discharge to near the time of the event.

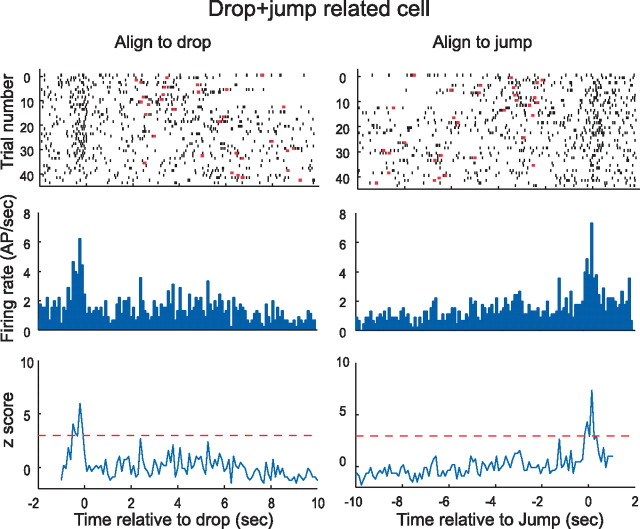

Figure 4.

An example of a pyramidal cell tuned to both drop and jump. The timescale for left column is aligned to the drop event, whereas the timescale for the corresponding right column are aligned to the jump. Except for trials for very long jump times that are not completely represented on either time base, the spike intervals are the same for a given trial in the raster plots. Note that aligning spikes to the drop event smears the peak associated with the jump event and vice versa. For this reason, the background firing during the wait time appears higher than in other examples. Note also that the peak rates (for drop and jump) are considerably lower than in the examples of Figures 2 and 3. The plots of z-score against time do not reach the astronomical values seen in Figures 2 and 3 because the peak rates are lower and the apparent background rates are higher. AP, Action potential.

Figure 5.

Lack of location specificity for event-related firing. A, Discharge of a jump-related cell shown in a raster plot (top) and a histogram (bottom). This cell fires briefly at the jump time. B, Activity of the same cell as in A divided according to the zone into which the rat was dropped. The middle diagram shows a foreshortened top view of the box and the rim onto which the rat jumps; the arrows represent the preferred landing goal when the rat is dropped into the corresponding quarter of the box. Each arrow points to a pair of panels, namely, a raster plot and a histogram. By inspection, it is seen that firing occurs preferentially at the time of the jump, regardless of the quadrant into which the rat was dropped. AP, Action potential.

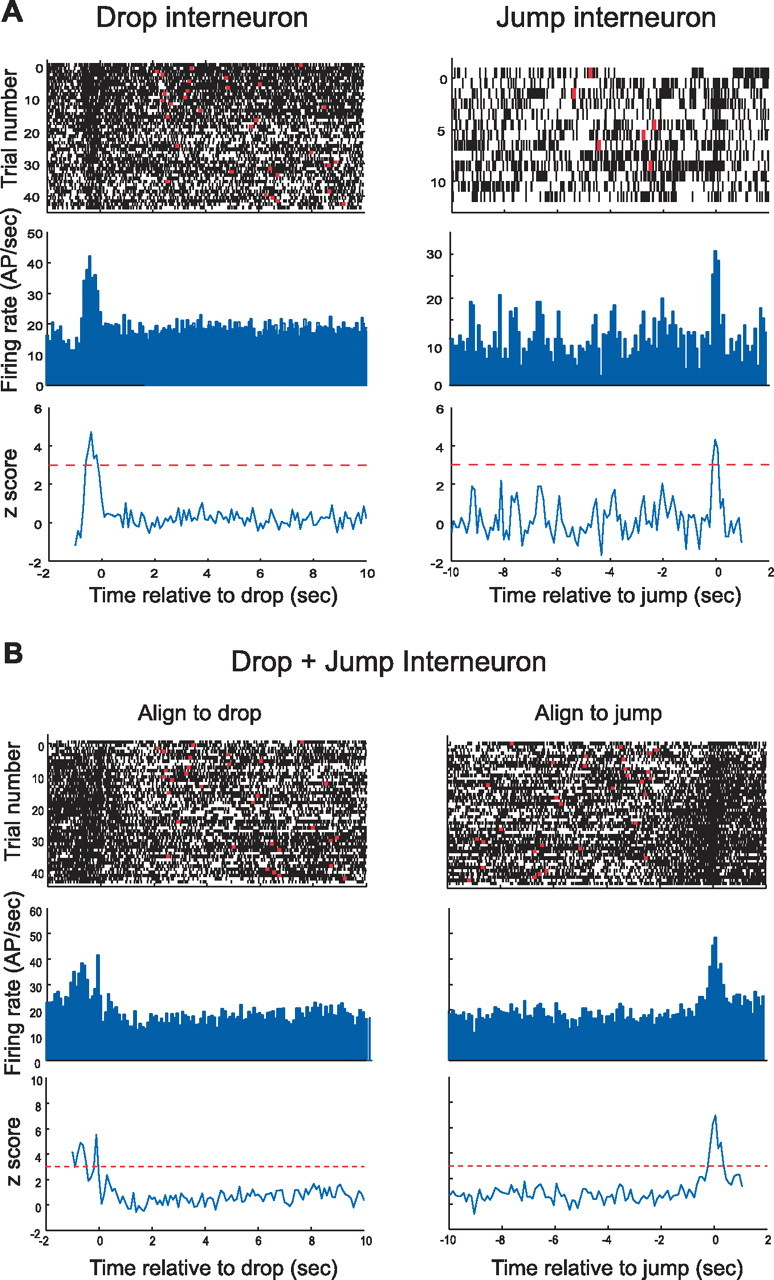

Figure 6.

Interneurons with event-related activity. The raster plot for the drop-related interneuron shows increased discharge just before and after the rat is released. Note that firing seems to be reduced just before drop time. The peak of the z-score is much lower than for most pyramidal cells, but, given a value of z = 4.8, the probability the maximum is equal to the background rate while the rat is in the box is only 7.9 × 10−7. Data for the jump interneuron are taken from a brief session, but the acceleration of firing at jump time is nevertheless evident; according to the z-score of 4.2, the probability the peak rate is equal to the background rate is 1.33 × 10−5. The drop-aligned and jump-aligned displays for this cell show that its discharge increases at both critical events. Of considerable interest is the light band in the raster plot at drop time. This cell shows a relative pause in firing just after the rat lands. AP, Action potential.

Event-related activity.

To assess the significance of event-related activity, a z-score for each 100 ms bin was computed relative to the average firing rate of the cell in the interval between 1 s after the drop to 1 s before the jump (background rate). The z-score is the bin rate minus the mean divided by the SD of the rates in the stated interval. If more than two successive bins show a z-score ≥3 during the time from 1 s before to 1 s after the event, the activity was considered to be event related. The “specificity ratio” is the peak rate at the time of the correlated event divided by the background rate. For cells whose discharge was elevated at both drop and jump, the specificity ratio is the higher of the two values.

In addition to determining the time of peak discharge rate, we also measured the time at which the rate was first judged to be higher than the background rate. To do this, we looked for the earliest group of three successive 20 ms bins in which the rate was reliably higher (p < 0.5) than the background rate and took the first of these bins as the estimate of when firing departed from activity seen at the bottom of the box. Because drop-related discharge often began as the rat was held above the landing spot for 2–3 s before being released, the maximum accepted value for the start of discharge before the event was set to 500 ms.

Results

Cell sample

A total of 246 cells were recorded from 10 rats during the jumping task, of which 207 (84%) were pyramidal cells and 39 (16%) were interneurons. Of this total, 168 (68%) were also recorded during pellet chasing on the disk. The fractions of pyramidal cells (137 of 168; 82%) and interneurons (31 of 168; 18%) seen during pellet chasing were the same as during jumping, showing that cell classification was consistent.

Event-related activity of pyramidal cells

Of the 207 pyramidal cells recorded during the jumping task, 48 (23%) showed significant event-related activity. As described in Materials and Methods, a cell was classified as a jump cell, a drop cell, or a drop+jump cell if its activity at the time of the appropriate event(s) was at least 3 SD greater than the firing rate averaged during the interval 1.0 s after the drop and 1.0 s before the jump. Of the 48 event-related pyramidal cells, 21 (44%) discharged preferentially at drop, 23 (48%) discharged preferentially at the jump, and 4 (8%) showed increased discharge at the time of both major events.

Properties of the three cell types are illustrated in Figures 2–4 and summarized in Table 1. The discharge patterns of two example drop cells are shown in Figure 2. The top row of Figure 2 contains raster displays that show, in each horizontal line, the spike activity of a cell during an individual trial. In Figure 2, the time in each trial is aligned to the instant the rat landed, each spike is represented as a short black line, and the moment at which the rat jumped is indicated with a red dot. The raster displays show that spikes for both cells were highly concentrated near landing time, although the distribution is broader for cell 1. These impressions are corroborated by the perievent spike histograms in the middle row of Figure 2 in which the discharge rate peak near drop time is evident. The bottom row of Figure 2 plots the standardized deviate (z-score) of the discharge rate in each 100 ms bin; the horizontal red lines show the 3.0 SD criterion used to separate cells with strong event-correlated firing. The extremely high peak z-values indicate that there is virtually 0 probability that the rate at drop is equal to the average rate during the waiting period on the floor. The organization of Figure 3 is the same as Figure 2, except that t = 0 for each trial is set to jump time, and the red bars indicate landing time. The tuning of the two example cells to the jump event is obvious in the raster panels, the perievent spike histograms, and in the z-score plots. An interesting feature of the activity for cell 1 is the secondary maximum after the jump peak, seen in the histogram (middle row) and z-score plot (bottom row). The origin of this phenomenon is visible in the raster plot (top row) in which there is sometimes elevated firing after the jump. This is attributable to the rat jumping into a firing field on the rim of the box on specific trials.

Table 1.

Average peak rate at the time of the drop or jump

| Peak rate at event | Background rate | Specificity ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drop cells | 16.60 | 0.64 | 42.26 |

| Jump cells | 18.20 | 1.35 | 17.53 |

| Drop + jump cells | 14.07 | 2.29 | 7.78 |

For drop + jump cells, the higher value is included in the average. The peak and background rates are arithmetic averages; the specificity ratio is the geometric mean of the individual specificity ratios. For drop + jump cells, the background rate is higher and the specificity ratio is lower than for the other types because the second event evokes firing from the cell that is included in the background rate. The background rate for jump cells is not reliably greater than for drop cells. In contrast, the specificity ratio for drop cells is significantly higher than for jump cells (t(42) = 2.36; p = 0.023).

Demonstrating the tuning of some pyramidal cells to both major events in a trial requires displaying the same data twice, first with trials in register with the landing and separately with trials in register with the jump. The firing of a drop+jump cell is depicted this way in Figure 4, in which the left column is aligned to the landing and the right column is aligned to the jump. For these cells, the magnitudes of the z-scores at event times are lower than for the example drop-only and jump-only cells. This apparent signal attenuation arises because the nonaligned event produces a secondary signal that is absent from cells with more specific discharge correlates.

The strength of the event-related signals in our pyramidal cell sample is documented in Table 1. The increased discharge rate during events relative to the background rate is on the same order of magnitude as the peak rate of place cell firing fields relative to the out-of-field rate. This strong modulation suggests that hippocampal pyramidal cell discharge may represent nonspatial as well as spatial information, in agreement with the work of Eichenbaum (2004) and others.

Timing of pyramidal cell event-related activity

We asked two questions about the time at which event-related activity generated by pyramidal cells occurs. First, we looked at the interval between an event and the average time of occurrence of the peak rate. For jump cells, the average time of the peak was −40.9 ms before the jump, suggesting that discharge is most intense just ahead of the event, although a t test did not reject the hypothesis that the peak is at t = 0 (p = 0.565; df = 22). Second, we asked when the discharge initially becomes higher than the background rate. On average, cell firing detectably accelerated 104 ms before the jump; a t test revealed that this interval is reliably >0.0 ms (p = 0.014; df = 22).

For drop cells, we found that the difference between the peak firing time and landing is considerable (−239.0 ms), suggesting that these cells are not tuned to the landing itself; a t test rejects the hypothesis that the rate peak is at t = 0 relative to landing (p = 0.00077; df = 20). It is therefore interesting that it takes the rat 280 ms to fall 38 cm, suggesting that drop cell activity is highest when the rat is released by the experimenter or at the start of free fall. According to a t test, the hypothesis that the peak rate occurs at release cannot be rejected (p = 0.732; df = 20). We also measured the time from the beginning of elevated activity to the landing. In many cases, this time was 0.5 s or more while the rat was suspended over the box just before being released. Specifically, the interval was >500 ms for 14 of 20 drop cells. Limiting the maximum to 500 ms yielded an average of 383 ms, suggesting that firing accelerated while position was constant, long before the rat fell and landed.

Are events the proper correlate of firing?

In a single trial, a rat is held 38 cm above the box floor and dropped onto a preset location on the box floor with its head pointing toward the nearest corner. A well trained rat stays very close to its landing position and waits for several seconds before it jumps to the rim at the nearest corner. In a more precise behavioral description, there are four trial segments: (1) at the start of a trial, the rat is carried to a position above the landing location; (2) the rat is dropped and falls onto the landing location; (3) the rat stays still for several seconds at the bottom of the box; and (4) the rat suddenly jumps out of the box.

In addition to changes of behavior (captive, freefall, immobility, and jump) and position at key moments in the trial, field potential recordings show that the hippocampal EEG is in the theta state during trial phases 1, 2, and 4. Thus, several features of the rat's circumstances are plausible candidates for the proper firing correlate, namely, the hippocampal EEG, location before an event, location above the floor (during an event), and finally the events themselves; we consider these in turn.

One possibility is that discharge occurs in relation to theta activity in the EEG. The duration of elevated firing near the time of the drop is, however, much briefer than the corresponding duration of elevated theta frequency. Moreover, the increase in theta frequency at jump time starts considerably before discharge accelerates above the background rate. Also, if discharge depends only on the state of the EEG, cells should not be preferentially active at one event or the other.

Second, because rats were nearly immobile before being dropped and while on the box floor before jumping, the rat's position before an event is not a strong candidate for a discharge correlate; if discharge were attributable to the rat's head occupying a firing field during immobility, activity would be maintained rather than phasic.

Third, firing might be attributable to the rat passing through the firing field of a place cell that is above the box floor. To test this possibility, rats were randomly dropped from four starting positions such that they landed facing the nearest box corner; they almost always jumped to that corner. Accordingly, the box was divided into four zones (Fig. 5), and discharge was analyzed separately for each zone as well as for the four zones combined. The composite activity for an example jump cell in all four zones is shown in Figure 5A. From Figure 5B, it is clear that the cell discharged regardless of the corner to which the rat jumped. This lack of spatial tuning argues against the idea that the observed discharge is attributable to passage of the rat through a firing field above the box floor.

To quantify the independence of putative event-related firing from location specificity, we computed the correlation between the time variation of position-independent rate and the discharge rate in each box quarter for the interval from −1.0 s before the event to 1.0 s after the event. With rate binned at 100 ms resolution, 20 rate pairs were correlated for each zone. The value of r for a one-tailed probability of 0.05 with 18 degrees of freedom is ∼0.38. For drop+jump cells, only the event with the higher peak discharge rate was considered.

Cells recorded from the first two rats in this study were not considered because they were allowed during training to walk to one or two preferred corners regardless of drop location. To preserve the requirement for rats to be still before jumping, these animals were dropped only into the preferred corners during formal recording so that cell activity at the other corners was rarely sampled. On this basis, 15 cells were eliminated during this analysis.

For the remaining 33 cells, we found that the overall and quadrant-specific firing patterns were significantly correlated for two cells at one corner, for four cells at two corners, for nine cells at three corners, and for 18 cells at all four corners; on average, a significant correlation was seen at 3.3 corners. Thus, most cells show the same event-related signal regardless of location in the environment. If the signal reflects location specificity, the supposed firing field would usually extend above most of the box floor. We conclude that the phasic discharge seen at event times may represent aspects of the events themselves and are not necessarily secondary to location-specific activity.

Event-related activity of interneurons

Of 31 interneurons recorded during jumping, 20 (65%) showed event-related activity. The probability is very low that the proportion of event-related pyramidal cells and interneurons is equal (z = 4.54; p = 0.000003). We saw one drop-related interneuron, 12 jump-related interneurons, and seven drop+jump-related interneurons; an example of each is shown in Figure 6. Note that the z-scores are not as extreme as for pyramidal cells. This is because the interneurons tend to discharge at all times with smaller relative increases at event times. An interesting feature of interneuron firing patterns are rate decreases before or after events; examples are seen before the main burst of the drop interneuron (Fig. 6A) and very near landing for the drop+jump cell (Fig. 6C) in the raster plot aligned to drop time.

A χ2 contingency test reveals that the fraction of event-related types for interneurons is different than for pyramidal cells (χ2 = 13.2; df = 2; p = 0.001), a difference based on the paucity of drop-related interneurons and the greater frequency of drop+jump interneurons. The fact that more than half the interneurons fire in relation to only the jump indicates some preservation of specificity; the fact that a higher proportion of interneurons fire at drop and jump reveals a form of convergence similar to that seen for place cell firing fields onto interneurons (Kubie et al., 1990; Marshall et al., 2002).

Because the sample contained only one pure drop-related interneuron, we combined its time of maximum discharge with those derived from the drop-related activity of the eight drop+jump interneurons. The mean peak time was 202.5 ms before landing. A t test does not reject the hypothesis that the true mean is at t = 0 relative to landing (p = 0.118; df = 7). Nevertheless, the average time was much closer to the 260 ms fall time (p = 0.875; df = 7). Thus, there is reason to believe that the primary drop correlate for interneurons as well as pyramidal cells is release rather than landing.

The mean peak time for the 12 pure jump interneurons was 92.5 ms after jump; a t test did not reject the hypothesis that the true jump time is t = 0 (p = 0.273; df = 10). The implication is that the proper correlate of jump-related interneuron activity is in fact the jump.

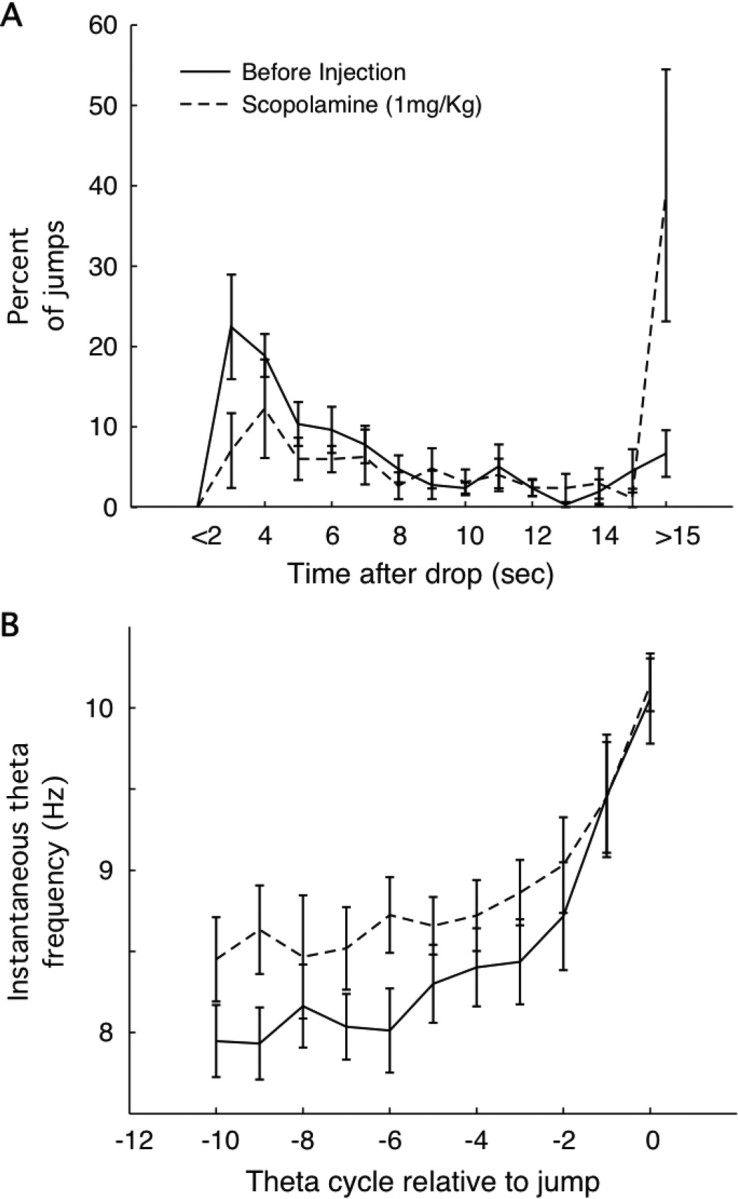

Event-related firing is modulated by the theta rhythm and shows phase precession

In agreement with previous work (Vanderwolf, 1969; Vanderwolf and Cooley, 1974), we find that hippocampal theta frequency increases as jump time approaches. Instantaneous frequency (1/peak-to-peak interval) as a function of time relative to jump is shown in Figure 7A for each of the 10 rats in the study and as an average over the rats in Figure 7B; in the average, the frequency increase is from ∼8.2 to ∼9.8 Hz during the five theta cycles before jump. For each rat, we also asked whether jumps tended to occur at a certain theta phase. According to Rayleigh vectors (Fisher, 1993), there was no relationship for the seven rats but a preferred jump phase (p < 0.05) for the other three. We saw no consistency for the preferred phase of these three rats and conclude that any relationship is likely to be weak. This result should be compared with the findings of Bland et al. (2006) who saw no preferred phase with low jumps (28 cm), a trend for a preferred phase with intermediate jumps (33 cm), and a clear preference with higher jumps (38 cm).

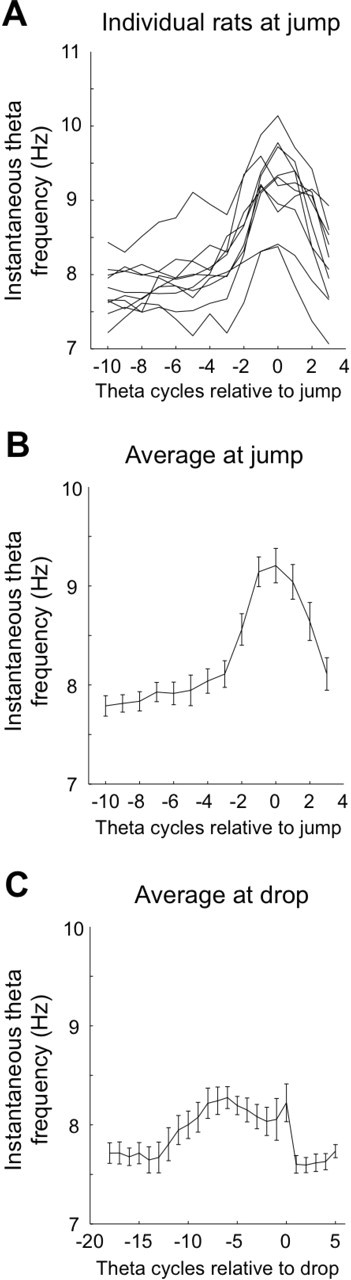

Figure 7.

Relationship between trial events and EEG frequency in the theta band. A, For each rat, the dominant frequency rises starting at approximately two theta cycles (0.25 s) before the jump. B, The same data plotted as an average across all 10 rats. C, At drop time, there is an elevation of frequency in the theta band starting at ∼13 cycles before the event. This is at the approximate time after the previous trial that the rat is picked up from the rim in preparation for the start of the next trial.

The increase of theta frequency at jump time was paralleled by a similar effect as drop time approached, although the form of the increase was more variable for individual rats (data not shown). The instantaneous frequency averaged across all rats (Fig. 7C) increased from ∼7.7 Hz as the rat was picked up (∼1.5 or ∼12 theta cycles before the drop) to ∼8.1 Hz when the rat was dropped. We presume that this synchronization could occur because the time interval from pickup to drop was rather constant. We did not look for a preferred phase at drop time because the event was not initiated by the rat.

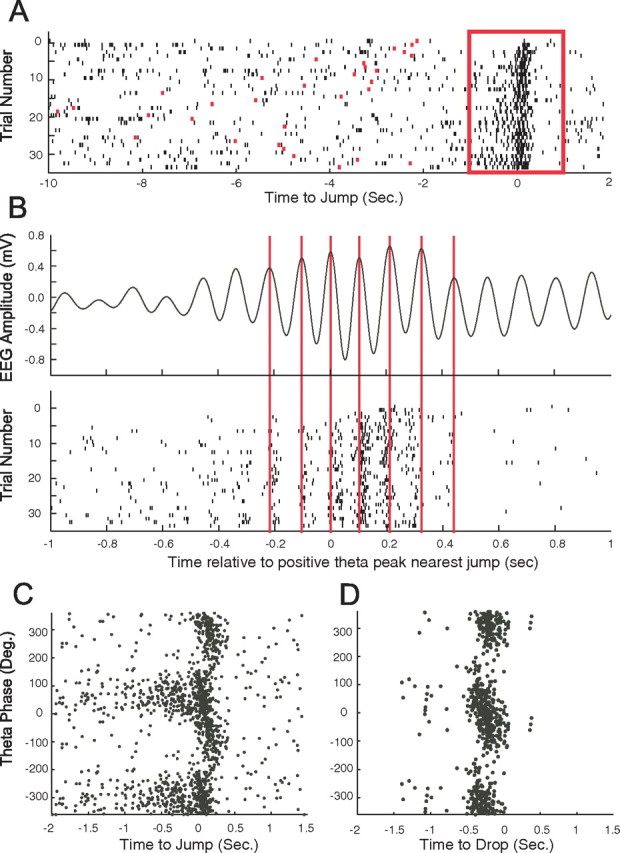

The enhancement of theta at the time of either drop or jump was associated with time modulation of event-related cell spiking. Moreover, this modulation showed the phase precession characteristic of place cell firing during walking through a firing field on a linear track (O'Keefe and Recce, 1993). In phase precession, spikes from a place cell occur at earlier phases of successive theta cycles as the rat goes through the firing field of the cell. The firing of an individual jump-related cell is shown relative to jump time in Figure 8A so that theta phase during the averaged trials is indeterminate. In Figure 8B, the time of the red box in Figure 8A has been expanded and the individual trials realigned to the positive peak of the theta cycle just before the jump. The average theta is shown in the top of Figure 8B, and a vertical red line is drawn through several positive peaks to extend to the bottom of Figure 8B. The precession effect is visible by comparing spike occurrence (small black marks) against the vertical line drawn through each positive peak of the averaged theta. A more conventional plot of the phase of each spike against the time it was fired is shown for the same cell in Figure 8C, in which the tendency of firing to precess near the time of jump is evident. We note that precession cannot be explained by the increased theta frequency as jump time approaches; by itself, the frequency effect would cause constant-rate spikes to occur later (and not earlier) on successive theta cycles. The time and phase for each spike fired by a drop-related cell is shown in Figure 8D, in which it is clear that precession may occur for such cells as well.

Figure 8.

Event-related discharge precesses on the theta phase. A, A raster plot for the activity of this jump-related cell. The box from −1.0 to 1.0 s relative to jump time is expanded in the next panels. B, The top shows the averaged EEG in the theta band after the time base was aligned to the positive peak theta peak closest to the jump. Note that the frequency increase demonstrated in Figure 7 is visible here as well. The bottom is a raster plot in which the time base for each trial is again aligned to the positive peak theta peak closest to the jump. The modulation of firing by theta cycles is made apparent in this way. Also visible is the precession of discharge with successive theta peaks as jump time approaches. Precession is demonstrated by extending vertical lines from six positive theta peaks onto the raster plot. In this way, the tendency of spikes to occur earlier on following theta peaks is emphasized. C, Conventional plot of the theta phase on which a spike occurs against the time of occurrence relative to jump for the same cell shown in A and B. Theta phase shows a clear progression toward negative values centered on jump time. For clarity, two cycles are plotted here and the next panel. D, Conventional plot of phase precession for a drop-related cell. Here, discharge precedes the event and phase changes from ∼90° at the start of discharge to approximately −90° at the end of discharge.

To estimate the occurrence of phase precession, we calculated the circular–linear correlation between spike phase and spike time for 44 cells; four cells were removed from this computation because their period of elevated discharge was less than two theta cycles. For drop+jump cells, the analysis was done only for the larger of the two event peaks. We found that the correlation coefficient was significant (p < 0.05) for 39 (89%) of the cells. Thus, the tendency for phase precession is characteristic of event-related activity.

Inspection of temporal precession for drop and jump cells suggests that the slope is steeper for jump cells as seen in the examples of Figure 8, C and D. To test this, we measured the slope for the 26 cells (14 drop and 12 jump) that discharged >100 spikes during precession. The mean slope was 0.411 ± 0.0036°/ms for drop cells and 0.851 ± 0.0144°/ms for jump cells. According to an unequal variance t test, the means are reliably different (t(24) = 3.03; p = 0.010). The higher temporal precession slope for jump cells compared with drop cells is in line with the greater theta frequency increase at jump than at drop. It is also in agreement with the shorter time between jump and arrival on the rim than between drop and landing as estimated from the ∼200 ms interval between jump and sudden deceleration of the rat's position at landing on the box rim. (Because of ringing in the accelerometer signal after jumps, we could measure jump speed only indirectly by looking at sudden changes in velocity just after jump time.)

Event-related cells and place cells

The fraction of cells that showed event-related firing (49 of 207; 24%) is significantly smaller than the fraction judged (coherence >0.3) to be place cells on the jump box rim (95 of 207; 46%); the probability these proportions are equal is low (z = 4.64; p ≪ 0.001). We saw cells that showed all four combinations of correlate. Of the 207 pyramidal cells, 19 had both event and place correlates, 76 had only a place correlate, 30 had only an event correlate, and 82 had neither correlate. According to a χ2 test, the probability a cell is event-related is apparently independent of whether it is a place cell on the jump box rim (χ2 = 1.31; df = 1; p = 0.25).

Most cells recorded during jumping were also recorded during pellet chasing on the disk (147 of 207; 71%). For 147 cells recorded on the disk, 82 (55.7%) were place cells. This is a somewhat larger fraction than on the jump box rim, but a test of proportions falls just short of significance (z = 1.55; p = 0.061); as expected, the disk place cell fraction is reliably higher than the event-related fraction. We also asked whether there was a contingency for a cell to be a place cell on the disk and either a place cell on the jump box rim or an event-related cell during jumping. Of 147 pyramidal cells, 40 were place cells on the disk and the rim, 42 were place cells on the disk only, 25 were place cells on the rim only, and 40 were not place cells is either case; a χ2 test shows that the probability of a pyramidal being a place cell in one circumstance does not predict whether it is a place cell in the other (χ2 = 1.17; p = 0.279). Similarly, of 147 pyramidal cells, 18 were place cells on the disk and event related, 42 were place cells on the disk but not event related, 25 were event related but not place cells on the disk only, and 40 had neither an event-related or place correlate; a χ2 test shows that the probability of a pyramidal cell showing event-related firing and being a place cell on the disk are independent (χ2 = 0.03; p = 0.862). Note that we saw instances of each of the eight possible cell types in the 2 × 2 × 2 categorization. Examples of the diversity of with which cells participate in the three situations are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Examples of simultaneously recorded cells with divergent firing properties in three situations. Cell 1 has a firing fields on the disk at 11:30 and a field on the left side of the rim; it is silent at drop but shows very precisely time-locked activity at jump. Cell 2 is nearly silent on both the disk and box rim but shows strong drop-related activity. Cell 3 has a large field on the disk, a small field on the right side of the box rim, and drop-related activity. In the population, all combinations of active/inactive for the three situations were seen. AP, Action potential.

The effects of scopolamine on event-related firing

Systemic injections of the muscarinic cholinergic antagonist scopolamine reduce both the firing rate and local organization of place cells (Brazhnik et al., 2003). Accordingly, we asked whether blockade of muscarinic receptors had similar effects on event-related cells. Thirty-five cells were recorded from five rats 1 h before and 1 h after a systemic injection of 1.0 mg/kg scopolamine, a nonspecific muscarinic antagonist. The average peak firing rate decreased by 36% from 18.58 to 11.79 spikes/s; a paired t test showed this effect to be very reliable (p = 0.00084; df = 34). This rate decrease was seen for both classes of event-related cells; after scopolamine, the peak rate of 17 drop cells decreased from 16.12 to 10.54 spikes/s (p = 0.0297; df = 16), and the peak rate of 18 jump cells decreased from 20.90 to 12.97 spikes/s (p = 0.0137; df = 17).

To test whether scopolamine also caused event-related firing to become less organized, we calculated a one-dimensional analog of coherence (Kubie et al., 1990). For the time range from 1 s before an event to 1 s after the event, we computed the Fisher z transform of the correlation between the firing rate in each 100 ms bin and the rate averaged in the preceding and following bins. The z transform was obtained twice for each cell, once in a predrug session and once after a scopolamine injection. The average score was 1.40 in the control session and 1.11 in the scopolamine session. A paired t test showed that this difference was very unlikely to be attributable to chance (t(34) = 2.95; p = 0.0061).

In addition to reduced and broader peak firing, peak discharge of jump-related cells shifted on average from +41 ms (after the jump start) to −207 ms (before the jump), although the shift was barely reliable (p = 0.0498; df = 17). The small shift of peak firing from −257 ms before landing before scopolamine to −307 ms after scopolamine was not significant (p = 0.678; df = 16).

Two effects of scopolamine combined to greatly reduced the number of cells that satisfied criteria for measuring the temporal precession slope. First, the number of avoidance trials was reduced (see below), limiting the number of spikes for the least-square fit. Second, the number of spikes around event times decreased, further reducing spike count. Moreover, many cells were not tested after scopolamine injections. Overall, the number of cells for which temporal precession slope could be measured decreased from 26 to 5 (three drop and two jump). Nevertheless, precession was observed for these cells after scopolamine, suggesting that it occurs with atropine-insensitive theta. The slope at drop remained shallower than at jump, but the difference was not reliable given the low number of observations.

The behavioral effects of scopolamine

Blockade of muscarinic transmission by atropine impairs performance in the jump avoidance task; the probability goes up that a rat will stay on the box floor until shocks begin (Vanderwolf, 1975). As illustrated in Figure 10A, scopolamine (1.0 mg/kg) has a similar effect; the fraction of trials with short avoidance latency goes down and the fraction of shock trials goes up. Thus, after scopolamine, the error rate increases from 7.7 to 38%. A test of proportions indicates that this change is extremely unlikely to be attributable to chance (z = 5.42; p ≈ 0).

Figure 10.

Effects of 1.0 mg/kg scopolamine on jumping behavior and theta frequency activity in the hippocampal EEG. A, Averaged over rats, the fraction of successful avoidances (jump time <15 s after drop) increases from ∼5 to ∼40%. For successful jumps, the post-scopolamine relationship between percentage and time after drop looks like a scaled-down version of the relationship before scopolamine. B, For successful jumps, the instantaneous theta band frequency increases as jump time approaches to reach ∼10.5 Hz. Interestingly, the frequency is higher at earlier times (∼1.0 s before jump).

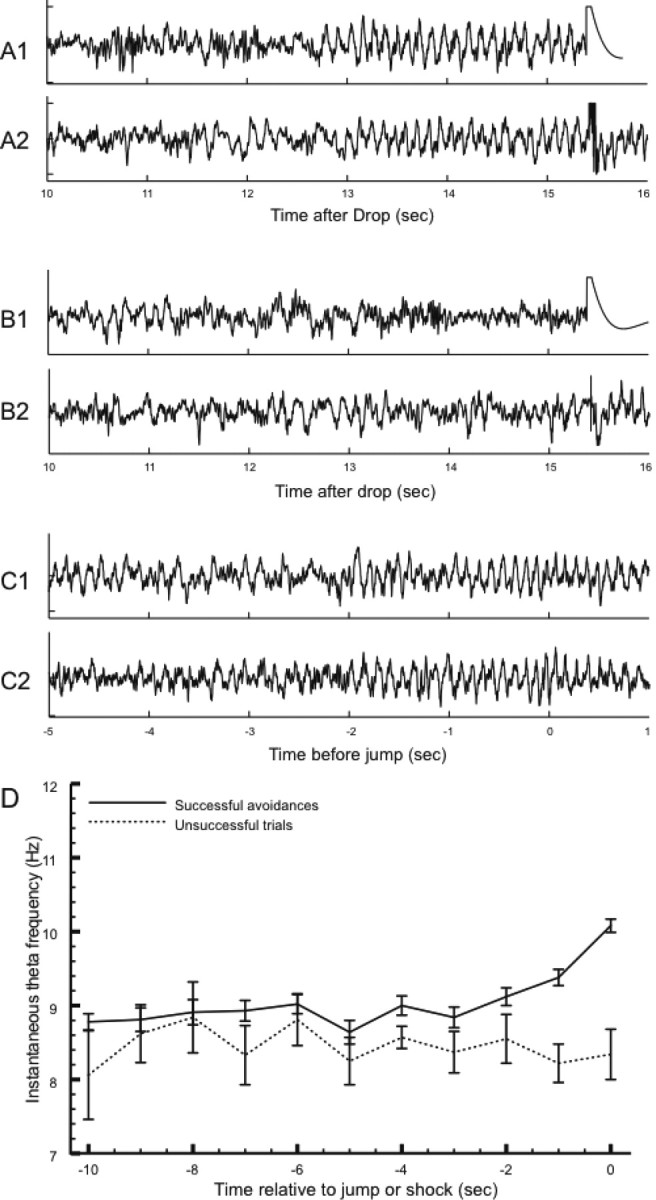

In conjunction with the increased number of errors, the form of the hippocampal EEG changes in very interesting ways. If only successful avoidance trials are analyzed after scopolamine, theta frequency reaches the same high value at the time of the jump as in the absence of the drug, but the earlier theta frequency is higher (Fig. 10B). In contrast, two different effects are seen in error trials. In some, robust theta is seen leading up to shock time, but no frequency acceleration is seen (Fig. 11A1,A2). In other trials, little power is seen in the theta band before shocks start (Fig. 11B1,B2). As implied by theta frequency as a function of time before jump during scopolamine (Fig. 10B), a frequency increase is seen on successful trials (Fig. 11C1,C2). The different theta profiles on unsuccessful versus successful trials is shown in Figure 11D.

Figure 11.

A–C, EEG records taken during escape trials (A, B) and avoidance trials (C). A, Unsuccessful trials (jump latency >15 s) during which the theta was present in the hippocampal EEG. Note that the theta frequency stays constant as the latest possible time to avoid a shock approaches. The artifact associated with shock delivery is seen at t = 15.5 s. B, Unsuccessful trials in which no coherent theta was seen with the approach of shock time. C, Successful avoidances in which theta frequency increased (see Figs. 7 and 9). Trials of the three types shown in A–C were interspersed during the session. Note that A and B are aligned to shock time, whereas C is aligned to the jump. D, Instantaneous theta frequency as a function time averaged for successful and unsuccessful trials during the same avoidance session used for the examples in A–C. The unsuccessful trials were those in which obvious theta activity was seen as the time since drop approached 15 s (see examples in A). The constancy of frequency for unsuccessful trials and the acceleration of frequency for successful trials is seen by inspection. According to a t test, the frequency of 10.08 Hz before successful jumps is reliably higher than the frequency of 8.34 Hz just before shock time (t(48) = 7.08; p = 5.5 × 10−9).

In a few sessions, we saw that the fraction of error trials (E) was in the range 0.25 < E < 0.75. In these cases, errors were randomly interspersed with successes. This sequence of successes and failures is not attributable to gradual scopolamine concentration changes at the effective site; a systematic trend to higher concentration would make error trials more likely later, whereas a trend to lower concentration would make error trials more likely earlier.

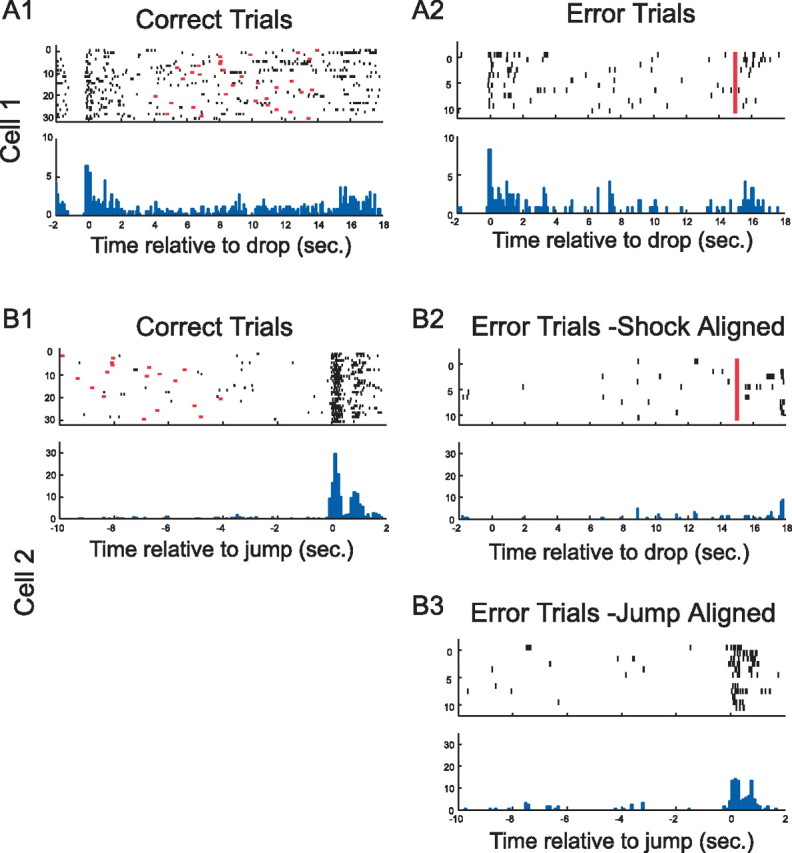

For these sessions, we inspected the firing patterns of individual cells in successful and failure trials, aligned in different ways (Fig. 12). Drop cells showed little difference between successes and failures when the activity in both were aligned to landing (Fig. 12A1,A2); such activity therefore does not predict whether the rat will avoid or escape on a given trial. In contrast, jump cells showed a clear rate acceleration on successful trials when their activity is aligned to jump (Fig. 12B1) but no such acceleration during the 15 s waiting interval in failure trials when their activity was aligned to the onset of shock (Fig. 12B2). Conversely, when jump cell activity on failure trials was realigned to the actual escape, clear excess activity was seen (Fig. 12B3). Thus, pyramidal cell activity signals the jump event or that movement through a firing field above the box floor.

Figure 12.

Pyramidal cell activity during drops and jumps for escape and avoidance trials. A1, A2 (cell 1), This drop cell discharged near the time of release regardless of whether the rat eventually escaped from shock by jumping out in >15 s (Error Trials) or avoided shock by jumping out in <15 s (Correct Trials). B1–B3 (cell 2), This jump cell showed virtually no activity when the rat failed to avoid (Error Trials − Shock Aligned) but crisp activity at jump when the rat avoided (Correct Trials). Clear activity was also seen when shock trials were aligned according to the jump made to escape (Error Trials − Jump Aligned).

Discussion

We asked whether rat hippocampal neurons fire in close temporal proximity to the major events that bracket each trial of a jump avoidance task (Vanderwolf, 1969). We found cells that showed elevated discharge at the time of the drop, the jump, and, in a few cases, at the time of both events. The signal was especially clear for pyramidal cells that were often nearly silent in the interval at the bottom of the box between drop and jump, but detectable firing accelerations were also seen for interneurons.

Events versus location

There are two competing accounts of neuronal firing correlates in the jump task. On the one hand, event-related cells may signal the drop and jump themselves; alternatively, they are better thought of as place cells that discharge when the rat goes through cell-specific firing fields. The difficulty of deciding between these viewpoints is summarized in Table 2, which lists place cell properties and corresponding aspects of cell activity in the jumping task. In each case, there is good agreement, suggesting that it is parsimonious to conclude that event-related firing is simply a variant of location-specific firing seen when the motion is abrupt and faster than walking or running (Geisler et al., 2007). Indeed, the lower temporal precession slope on drops compared with jumps has the immediate interpretation that the speed of jumps is greater than the speed of drop, in agreement with the greater increase in theta frequency seen at jump compared with drop and also with our best estimates of actual acceleration.

Table 2.

Comparison of cell discharge during place cell activity and event-related activity

| Property | Location-specific discharge | Event-related discharge |

|---|---|---|

| Stability of correlate | Yes | Yes |

| Sparsity: fraction of participating cells | 40% | 25% |

| Specificity | One firing field per cell; rarely two | Drop or jump; rarely both |

| Directionality | One way on linear track | Up or down |

| Clustering of similar cells in hippocampus | No | No |

| Peak firing rate | 5–50 spikes/s | 5–50 spikes/s |

| Firing modulation by theta | Yes | Yes |

| Precession with theta | Yes | Yes |

| Rate decreased by scopolamine | Yes | Yes |

| Precision reduced by scopolamine | Yes | Yes |

| Interneuron correlates | Multiple high-rate zones | Most fire at drop and jump |

Stability describes the constancy of cell-specific discharge pattern seen when the rat is returned to the same circumstances. Sparsity refers to the fraction of pyramidal cells in the active subset. Specificity is confinement of discharge to a small number of regions or events. Directionality is the tendency of cells to fire only when the rat walks in one direction on a one-dimensional path; it is not distinguishable from specificity for event-related activity. The lack of clustering implies that cells with different discharge correlates occur independent of distance within the pyramidal cell layer. Modulation and precession with the theta rhythm indicate that discharge covaries with theta phase. Scopolamine rate effect is as described; scopolamine effect on precision is measured by coherence or its one-dimensional analog used here. The multiple high rate zone of interneurons during spatial tasks and the tendency for interneurons to fire at drop and jump may reflect their property of receiving convergent input from multiple pyramidal cells.

In line with this reasoning is the independence of the participation of a cell (member of the active subset) in the jump-task representation, in the place cell representation on the box rim, and in the place cell representation on the disk. The three representations may be considered remappings of each other so that the active subset of cells that participates in each representation is plausibly a random selection (with replacement) from the pyramidal cell population. If the location-specific interpretation is accepted without reservation, our results demonstrate a novel feature of place cell activity, namely, that firing fields are three dimensional and may extend over only part of the distance in the z direction between box floor and rim. The notion is that individual cells fire as the rat falls or flies through a cell-specific stratum at drop or jump.

Despite the remarkable congruencies between event-related and location-specific discharge, however, several aspects of our results indicate that the representation of the jump task is distinct from representations for strongly space-related tasks. First, we found that the fraction of pyramidal cells that participate in the jump-task representation is reliably smaller than the fraction for either place representation, suggesting that the repetitive, stereotyped jump task is represented more sparsely than a spatial map. Second, we saw that most cells discharged in the same temporal pattern regardless of the box floor quadrant into which the rat was dropped or from which it jumped; according to this estimate 18 of 33 (55%) of cells showed no spatial specificity despite clear event specificity. Third, the time that activity accelerates reliably from baseline is often well before the animal is dropped or before it jumps. Fourth, precession takes place in the face of increased theta frequency at both drop and jump; on linear tracks, precession occurs while theta frequency is constant. Fourth, the selected dose of scopolamine sometimes caused a rat to fail to jump within 15 s after drop. On such trials, jump cells hardly discharged during the waiting interval, although the rat's location was on average no different than on successful trials in which firing was intense. We also note that firing accelerated when the rat escaped shock, at the time of the actual movement. These observations do not preclude firing fields above the floor, but they militate against the idea that pre-jump firing is attributable to the rat entering a field on the floor.

A third possibility, intermediate between the others, is that the pyramidal cell population represents both temporal and spatial aspects of the jump task. In this case, individual cells might represent features of both kinds in different amounts or the two kinds of aspect might be separated at the cell level. The second arrangement is reminiscent of the independent set of “object cells” whose activity depends on the rat's proximity to a vertical barrier placed in the environment (Rivard et al., 2004). Object cells appear to be place cells in a fixed environment that contains the barrier, but their discharge moves with the location of the barrier, they shut off when the barrier is removed, and they continue to fire in a second environment in which true place cells undergo remapping. The complete representation of environment plus barrier is thus an amalgam of cells with distinguishable properties. It is possible that different cells represent different aspects of the behavioral state near event time or that the discharge of individual cells is properly regarded as reflecting both events and space.

Hippocampal processing style

The similar properties of location and event representations summarized in Table 2 may be interpreted according to the multiple parallel memory system theory (White and McDonald, 2002). In part, this theory proposes that each of three different memory areas (hippocampus, striatum, and amygdala) use access from the same sensory information to generate different solutions to individual problems. Among other issues, the theory helps explain how performance by rats can be improved by lesions of a memory region that produces incorrect solutions. A second aspect of the theory is that each memory region always uses a structure-specific algorithm for solutions. This aspect of the theory can be tested by making predictions about event-related firing based on location-specific firing. For example, it is interesting to ask whether transferring the avoidance task to a circular box or one with a different appearance would induce a complete remapping of the discharge correlate of individual pyramidal cells so that only sparsity would be preserved? In previous work, increasing the height of the box enhanced the theta-band EEG frequency increase at jump time (Morris and Hagan, 1983). It would therefore be useful to see whether peak discharge rate varied monotonically with jump height or whether it was reduced by changing jump height in either direction away from the trained height; the second outcome would correspond to the finding that increasing or decreasing the distance between two salient landmarks reduces peak firing, as if the cells are “tuned” to a template of the original, familiar configuration (Fenton et al., 2000).

Hippocampal EEG, cell activity, and behavior

We observed a remarkable relationship between the state of the hippocampal EEG and behavior on individual trials after scopolamine injection. It was invariably the case that successful avoidances were preceded by clear theta activity whose frequency increased with successive cycles as jump time approached. High doses of antimuscarinic agents abolish this EEG pattern completely (Kramis et al., 1975), but, at the moderate (1.0 mg/kg) dose of scopolamine we used, successful avoidance trials were apparently randomly interspersed with trials in which the rat failed to avoid (latency, >15 s). Just as successful trials were preceded by the ramping up of theta frequency, failures were accompanied by either theta whose frequency never increased or an absence of theta.

The same pattern of random sequences of avoidances and failures was seen in two other circumstances. In one, rats were put back in the jump box at a short interval (∼2 s) over a 4 h time period (Vanderwolf and Cooley, 1974). Near the end of this strenuous protocol, rats often did not jump before the maximum 15 s interval; on such trials, there was no theta in the EEG or theta frequency remained near 8 Hz. A similar effect was seen during the onset of haloperidol action after injection (Vanderwolf, 1975). The tight coupling of hippocampal EEG pattern and behavior is seen, although the sensory conditions are constant from trial to trial, suggesting that the EEG either reflects or is a determinant of the motor program about to be executed. For jump cells, the lack of activity during failure trials indicates that the coupling extends to the single-cell level.

Conclusion

In summary, and to the extent that jump avoidance is at least in part a nonspatial task, our results strongly support the view that hippocampal processing may encode the succession of events as well as the succession of positions (Eichenbaum, 2004). A scheme for how the relevant computations can cover both the spatial and temporal domains is outlined by Samsonovich and Ascoli (2005).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS20686. We thank Matt Holzer for technical support and Dr. Norman White for valuable critical suggestions.

References

- Berger TW, Thompson RF. Neuronal substrates of classical conditioning in the hippocampus. Science. 1976;192:483–485. doi: 10.1126/science.1257783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland BH, Jackson J, Derrie-Gillespie D, Azad T, Rickhi A, Abriam J. Amplitude, frequency and phase analysis of hippocampal theta during sensorimotor processing in a jump avoidance task. Hippocampus. 2006;16:673–681. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazhnik ES, Muller RU, Fox SE. Muscarinic blockade slows and degrades the location-specific firing of hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:611–622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00611.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. Hippocampus: cognitive processes and neural representations that underlie declarative memory. Neuron. 2004;44:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton AA, Csizmadia G, Muller RU. Conjoint control of hippocampal place cell firing by two visual stimuli. I. The effects of moving the stimuli on firing field positions. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:191–209. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher NI. Statistical analysis of circular data. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Geisler C, Robbe D, Zugaro MB, Sirota A, Buzsaki G. Hippocampal place cell assemblies are speed-controlled oscillators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8149–8154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KD, Henze DA, Hirase H, Leinekugel X, Dragoi G, Czurko A, Buzsaki G. Spike trains dynamics predicts theta-related phase precession in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Nature. 2002;417:738–741. doi: 10.1038/nature00808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxter J, Burgess N, O'Keefe J. Independent rate and temporal coding in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Nature. 2003;425:828–832. doi: 10.1038/nature02058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramis R, Vanderwolf CH, Bland BH. Two types of hippocampal rhythmical slow activity in both the rabbit and the rat: relations to behavior and effects of atropine, diethyl ether, urethane, and pentobarbital. Exp Neurol. 1975;49:58–85. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(75)90195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubie JL, Muller RU, Bostock E. Spatial firing properties of hippocampal theta cells. J Neurosci. 1990;10:1110–1123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01110.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenck-Santini PP, Muller RU, Save E, Poucet B. Relationships between place cell firing fields and navigational decisions by rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9035–9047. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-09035.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Osan R, Shoham S, Jin W, Zuo W, Tsien J. Identification of network-level coding units for real-time representation of episodic experiences in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6125–6130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408233102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L, Henze DA, Hirase H, Leinekugel X, Dragoi G, Buzsaki G. Hippocampal pyramidal cell-interneuron spike transmission is frequency dependent and responsible for place modulation of interneuron discharge. J Neurosci. 2002;22(RC197):1–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-j0001.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RGM, Hagan JJ. Hippocampal electrical activity and ballistic movement. In: Seifert W, editor. Neurobiology of the hippocampus. London: Academic; 1983. pp. 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Muller RU, Kubie JL. The effects of changes in the environment on the spatial firing of hippocampal complex-spike cells. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1951–1968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01951.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller RU, Kubie JL, Bostock EM, Taube JS, Quirk GJ. Spatial firing correlates of neurons in the hippocampal formation of freely moving rats. In: Paillard J, editor. Brain and space. Oxford: Oxford UP; 1991. pp. 296–333. [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J. Hippocampal neurophysiology in the freely behaving animal. In: Andersen P, Morris RGM, Amaral DG, Bliss TV, O'Keefe J, editors. The hippocampus book. Oxford: Oxford UP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J, Recce ML. Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm. Hippocampus. 1993;3:317–330. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The brain in stereotaxic coordinates. New York: Academic; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ranck JBJ. Studies on single neurons in dorsal hippocampal formation and septum in unrestrained rats. I. Behavioral correlates and firing repertoires. Exp Neurol. 1973;41:461–531. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(73)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivard B, Li Y, Lenck-Santini PP, Poucet B, Muller RU. Representation of objects in space by two classes of hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:9–25. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsonovich AV, Ascoli GA. A simple neural network model of the hippocampus suggesting its pathfinding role in episodic memory retrieval. Learn Mem. 2005;12:193–208. doi: 10.1101/lm.85205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL, Wilson MA, Barnes CA. Theta phase precession in hippocampal neuronal populations and the compression of temporal sequences. Hippocampus. 1996;6:149–172. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:2<149::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwolf CH. Hippocampal electrical activity and voluntary movement in the rat. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1969;26:407–418. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(69)90092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwolf CH. Neocortical and hippocampal activation relation to behavior: effects of atropine, eserine, phenothiazines, and amphetamine. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975;88:300–323. doi: 10.1037/h0076211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwolf CH, Cooley RK. Hippocampal electrical activity during long-continued avoidance performance: effects of fatigue. Physiol Behav. 1974;13:819–823. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(74)90268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White NM, McDonald RJ. Multiple parallel memory systems in the brain of the rat. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2002;77:125–184. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zugaro M, Monconduit L, Buzsaki G. Spike precession persists after transient intrahippocampal perturbation. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:67–71. doi: 10.1038/nn1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]