Abstract

In our previous studies of varying osmotic diuresis, UT-A1 urea transporter increased when urine and inner medullary (IM) interstitial urea concentration decreased. The purposes of this study were to examine 1) whether IM interstitial tonicity changes with different urine urea concentrations during osmotic dieresis and 2) whether the same result occurs even if the total urinary solute is decreased. Rats were fed a 4% high-salt diet (HSD) or a 5% high-urea diet (HUD) for 2 wk and compared with the control rats fed a regular diet containing 1% NaCl. The urine urea concentration decreased in HSD but increased in HUD. In the IM, UT-A1 and UT-A3 urea transporters, CLC-K1 chloride channel, and tonicity-enhanced binding protein (TonEBP) transcription factor were all increased in HSD and decreased in HUD. Next, rats were fed an 8% low-protein diet (LPD) or a 0.4% low-salt diet (LSD) to decrease the total urinary solute. Urine urea concentration significantly decreased in LPD but significantly increased in LSD. Rats fed the LPD had increased UT-A1 and UT-A3 in the IM base but decreased in the IM tip, resulting in impaired urine concentrating ability. The LSD rats had decreased UT-A1 and UT-A3 in both portions of the IM. CLC-K1 and TonEBP were unchanged by LPD or LSD. We conclude that changes in CLC-K1, UT-A1, UT-A3, and TonEBP play important roles in the renal response to osmotic diuresis in an attempt to minimize changes in plasma osmolality and maintain water homeostasis.

Keywords: UT-A3 urea transporter, CLC-K1 chloride channel, TonEBP transcription factor

the ut-a1 urea transporter plays a key role in urine concentration in mammals (21). In our previous studies, Sprague-Dawley rats made diabetic with streptozotocin had a great increase in UT-A1 abundance in both inner medullary (IM) base and tip to conserve water despite the ongoing osmotic diuresis (2, 12, 13). In contrast, diabetic Brattleboro rats (which lack vasopressin) did not increase UT-A1 protein abundance, and vasopressin-treated diabetic Brattleboro rats increased UT-A1 protein abundance more than nondiabetic vasopressin-treated Brattleboros (14). This suggests that vasopressin and another factor (or factors) work together to increase UT-A1 abundance.

Rats with NaCl diuresis induced by feeding of a high-salt diet also had a significant increase in UT-A1 abundance in both portions of the IM. However, rats with urea diuresis induced by feeding of urea did not increase UT-A1 abundance in either portion of IM, regardless of the severity of the osmotic diuresis (12). Rats with diabetes or NaCl diuresis have relatively decreased urea in the total urinary solute since the excretion of other solutes (glucose or NaCl) is increased, whereas rats fed a high-protein or -urea diet have an increase of urea in the total urinary solute, suggesting that UT-A1 is increased when urine urea concentration is low. Consistent with this, rats with diabetes or a high-salt diet did not increase UT-A1 abundance in either IM tip or base when urea was added to their diet (12).

NaCl and urea are the two major solutes in the renal IM. Cl− is reabsorbed by the thin ascending limb through the CLC-K1 chloride channel; with Na+ following due to the electrical gradient, resulting in NaCl reabsorption (28, 30). Urea is reabsorbed from the terminal IM collecting duct (IMCD) through the UT-A1 and UT-A3 urea transporters, with urine urea concentration reflecting IM interstitial urea concentration (12, 24).

Urea evenly distributes between extra- and intracellular fluid. In contrast, NaCl mainly exists in extracellular fluid, causing hypertonic stress to the cells. We hypothesized that the changes in the solute composition of the IM interstitium induced by different urine urea concentrations might affect IM interstitial tonicity, which in turn regulates UT-A1 and UT-A3 urea transporter abundance, since the tonicity-enhanced binding protein (TonEBP) regulates UT-A1 and UT-A3 transcription (17).

In this study, we examined the abundance and intracellular distribution of UT-A1, UT-A3, CLC-K1, and the TonEBP transcription factor in NaCl diuresis induced by a high-salt diet (HSD), which decreases urine and IM interstitial urea concentration, and urea diuresis induced by a high-urea diet (HUD), which mimics urine urea from a high-protein diet and increases urine and IM interstitial urea concentration. We also examined whether the same result occurs if the total urinary solute is decreased as with a low-protein diet (LPD), which decreases urine and IM interstitial urea concentration, and a low-salt diet (LSD), which increases urine and IM interstitial urea concentration.

METHODS

Animal preparation.

All animal protocols were approved by the Catholic University of Korea Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Orient Bio, Seongnam, Korea), weighing 125–200 g, received free access to a standard diet (Testdiet 5001, Purina, Richmond, IN) containing 23% protein and 1.05% NaCl. All rats received free access to water throughout the study except for the last several hours before death to exclude the variables that may be induced by the latest water-drinking.

Two approaches were used to increase or decrease urine volume. The first was to induce osmotic diuresis with NaCl or urea. To induce NaCl diuresis, rats were fed a HSD containing a total of 4% NaCl diet where 3% NaCl was added to the standard powdered diet (which contains 1.05% NaCl) for 2 wk. To induce urea diuresis, rats were fed the standard diet to which 5% urea was added (HUD) for 2 wk. Rats receiving either the HSD or HUD were compared with control rats receiving the standard test diet.

In the second approach, to reduce urine volume by decreasing urea excretion, rats were fed a LPD containing 8% protein and 1.05% NaCl (AIN93G, 8% modified protein+ 1.05% NaCl, Feedlab, Gyeonggi, Korea) for 2 wk. To reduce urine volume by decreasing NaCl excretion, rats were fed a LSD containing 0.4% NaCl and 23% protein (Testdiet 570B, Purina) for 2 wk. Rats receiving either the LPD or LSD were compared with control rats on the standard diet.

Two days before death, rats were put into metabolic cages (Techniplat, Buguggiate, Italy) and a 24-h urine collection was obtained to measure urine volume, osmolality (Fiske 2400 osmometer, Advanced Instruments, Norwood, MA), and urea concentration (Hitachi 7600-110 autoanalyzer, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). After 2 wk, rats were fully anesthetized with Zoletil 50 (1.0 μ/g ip, Virbac Laboratories, Carros, France), killed, and venous blood was collected to measure blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and osmolality.

Tissue preparation for Western blot analysis.

One kidney from each rat was used for Western blotting and the other kidney for immunohistochemistry. Kidneys were removed and dissected into IM tip and base at 4°C. Fresh kidney tissues were homogenized in a glass tissue grinder in ice-cold isolation buffer (10 mM triethanolamine, 250 mM sucrose, pH 7.6, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 2 mg/ml PMSF), and then SDS was added to a final concentration of 1% for Western blot analysis of the total cell lysate. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, the protein concentration was determined by a modified Lowry method (Bio-Rad DC protein assay reagent, Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). The appropriate amount of each sample was diluted in a Tris-glycine/SDS sample buffer (125 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 10% glycerol, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.02% bromophenol blue) and heated at 100°C for 3 min (12).

Western blot analysis.

Western blotting was performed as described previously (12–14). Briefly, proteins (10–20 μg/lane) were size separated by SDS-PAGE using 6 or 10% polyacrylamide gels and electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad) at 100 mV for 1 h. To confirm the equivalent protein loading and transfer, the membranes were stained with Ponceau S. The membranes were pageed with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST; 0.2 M Tris, 1.37 M NaCl, 0.5% Tween 20, pH 7.6) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST at 4°C overnight. The membranes were extensively washed four times with TBST and treated for 2 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad), which was diluted in 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST to a final dilution of 1:3,000. The blots were washed with TBST and then detected using a Western blotting luminol reagent kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The resulting membranes were exposed to Kodak BioMax Light film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY), and the films were developed with GBX developer and replenisher (Eastman Kodak).

Tissue preparation for immunohistochemistry.

The kidneys were preserved by in vivo perfusion through the abdominal aorta. Deeply anesthetized animals were initially perfused briefly with PBS, osmolality 298 mosmol/kgH2O (pH 7.4), to rinse away all blood. This was followed by perfusion with a periodate-lysine-2% paraformaldehyde (PLP) solution for 10 min. After perfusion, the kidneys were removed and cut into 1- to 2-mm-thick slices that were further fixed by immersion in PLP solution overnight at 4°C. The tissue sections were cut transversely through the entire kidney at a thickness of 50 μm using a vibratome (Pelco 102, series 1000, Technical Products International, St. Louis, MO) and processed for immunohistochemical studies using a horseradish peroxidase preembedding technique.

Immunohistochemistry: preembedding procedure.

Fifty-micrometer tissue sections were washed three times in PBS containing 50 mM NH4Cl for 15 min. Before incubation with the primary antibodies, the sections were pretreated with a graded series of ethanol or not pretreated with ethanol and then incubated for 4 h with PBS containing 1% BSA, 0.05% saponin, and 0.2% gelatin (solution A). The tissue sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in solution A. After several washes with PBS containing 0.1% BSA, 0.05% saponin, and 0.2% gelatin (solution B), the tissue sections were incubated for 2 h in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG Fab fragment (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) which was diluted 1:100 in PBS containing 1% BSA (solution C). The tissues were rinsed, first in solution B, and then in 0.05 M Tris buffer (pH 7.6). To detect horseradish peroxidase, the sections were incubated in 0.1% 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) in 0.05 M Tris buffer for 5 min. Then, H2O2 was added to a final concentration of 0.01% and the incubation was continued for 10 min. The sections were washed three times in 0.05 M Tris buffer, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and embedded in Poly/Bed 812 resin (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). The sections were examined with a light microscope.

Antibodies.

To detect UT-A1, a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against a peptide based on rat renal UT-A was used (12–14). UT-A3 was detected by a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a NH2-terminal peptide of UT-A3 (3). CLC-K1 expression was detected using a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against a peptide sequence from rat CLC-K (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). TonEBP expression was detected using a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against TonEBP (16). Mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used as a loading control.

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± SD (n), where n indicates the number of rats studied. To test for statistically significant differences between two groups, an unpaired Student's t-test was used. To test for statistically significant differences among three or more groups, an ANOVA was used followed by a one-way ANOVA test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Physiological parameters.

Table 1 shows urinary solute amount, urea, osmolality, volume, and plasma urea and osmolality. Total urinary solute excretion was increased in rats fed a HSD or HUD and decreased in rats receiving the LPD or LSD. Urea excretion was increased in HUD-fed rats, decreased in LPD-fed rats, and maintained in rats receiving the HSD or LSD. The relative amount (percentage) of urea in the total urinary solute and the urine urea concentration were significantly decreased by the HSD (due to relatively increased NaCl excretion) and LPD (due to decreased urea excretion) from 47 to 27 and 11%, while significantly increased by the HUD (due to increased urea excretion) and LSD (due to relatively decreased NaCl excretion) from 47 to 61 and 57%.

Table 1.

Urine and blood chemistries

| CTR | HSD | HUD | LPD | LSD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total urinary solute, mmol·day−1·100 g BW−1 | 1,890±2.0 | 14.1±3.9* | 16.0±2.9* | 4.8±0.7* | 6.6±0.8* |

| Urea excretion, mmol·day−1·100 g BW−1 | 4.5±0.8 | 3.8±1.0 | 9.8±1.9* | 0.5±0.1* | 3.7±0.5 |

| Urea in urinary solute, % | 47.3±3.9 | 27.5±1.4* | 61.1±2.1* | 10.3±2.0* | 57.0±1.9* |

| Urine urea concentration, mmol/l | 891±79 | 305±91* | 1,236±125* | 81±40* | 1,164±182* |

| Urine osmolality, mosmol/kgH2O | 1,890±192 | 1,119±359* | 2,022±171 | 776±298* | 2,082±343 |

| Urine volume, ml·day−1·100 g BW−1 | 5.1±0.9 | 12.8±1.1* | 8.0±1.6*† | 6.8±2.1* | 3.3±0.7* |

| BUN, mg/dl | 15.0±2.0 | 19.3±2.4* | 26.7±5.0* | 7.8±1.7* | 12.7±1.6 |

| Posm, mosmol/kgH2O | 318±5 | 330±8* | 330±6* | 300±3* | 317±7 |

Values are means ± SD; n = 6 for experimental groups; n = 12 for controls for 2 experiments combined. CTR, control; HSD, high-salt diet; HUD, high-urea diet; LPD, low-protein diet; LSD, low-salt diet; BW, body wt. Total urinary solute = Uosm (mmol) × urine volume (liters) ÷ BW (g) × 100 (g) ÷ day.

P < 0.05 vs. control.

P < 0.05, HUD vs. HSD.

Urine osmolality was lowest in the LPD group but also decreased with the HSD. Urine osmolality was maintained with the HUD and LSD. Urine volume was increased with both HSD and HUD. However, osmotic diuresis was more severe in HSD rats than in those receiving the HUD. The urine volume of the LSD rats was significantly decreased. On the other hand, the rats fed the LPD had a significant increase in urine volume.

BUN was significantly increased with the HUD and HSD, decreased in LPD rats, and maintained in rats receiving the LSD. Plasma osmolality was significantly increased in HSD and HUD rats, decreased in LPD rats, and maintained in LSD rats.

Effect of osmotic diuresis induced by HSD or HUD on UT-A1, UT-A3, CLC-K1, and TonEBP proteins.

UT-A1 abundance was significantly increased in both the IM tip (166% of control) and base (135% of control) due to an increase in the 117-kDa glycoprotein form in HSD rats (Fig. 1A). In contrast, in HUD rats, UT-A1 abundance was significantly decreased in both the IM tip (81% of control) and base (54% of control), again due to a decrease in the 117-kDa glycoprotein form (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Western blot analysis of UT-A1 urea transporter in the inner medullary (IM) base and tip of rats fed a high-salt diet (HSD; A) and high-urea diet (HUD; B). Blots, probed with a specific antibody to UT-A, show the characteristic 117- and 97-kDa glycoprotein forms of UT-A1. Top: Western blot image. Bottom: summary of densitometric analysis of the total groups with each 117- and 97- kDa band density averaged for each group. CTR, control. Values are means ± SD; n = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05, experimental vs. control.

Consistent with previous Western blot analyses (11), immunohistochemical staining shows that UT-A1 immunoreactivity was increased in the IM of HSD rats (Fig. 2, E and H) and decreased in HUD rats (Fig. 2, F and I). UT-A2 immunoreactivity, seen in descending thin limbs in the inner stripe of the outer medulla, was not changed in HSD rats (Fig. 2B), while significantly increased in HUD rats (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Light micrographs of 50-μm-thick vibratome sections illustrating immunostaining for UT-A in the rats fed a HSD and HUD. A–C: outer medulla (OM). D–F: inner medullary base (IMb). G–I: inner medullary tip (IMt). UT-A1 immunoreactivity (D–I) in the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD; asterisks) was increased in HSD, while decreased in HUD. UT-A2 labeling (A–C) is observed in the descending thin limb (DTL; arrowheads) in the OM. Bars = 500 μm (A–C) and 20 μm (D–I).

UT-A3 abundance was significantly increased in both the IM tip (122% of control) and base (180% of control) in HSD rats, due mainly to changes in the 67- and 44-kDa isoform, respectively (Fig. 3A). In contrast, UT-A3 was significantly decreased in both portions of the IM (59% in IM base, 69% in IM tip) in HUD rats (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of UT-A3 urea transporter in the IM base and tip of rats fed a HSD (A) and HUD (B). Blots show the characteristic 67- and 44-kDa glycoprotein forms of UT-A3. Top: Western blot image. Bottom: summary of densitometric analysis of the total groups with each 67- and 44- kDa band density averaged for each group. Values are means ± SD; n = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05, experimental vs. control.

CLC-K1 abundance in both portions of the IM was significantly increased in HSD (127% of control in IM base, 180% of control in IM tip) (Fig. 4A), while significantly decreased in HUD (53% of control in IM base, 61% of control in IM tip) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Western blot analysis of CLC-K1 chloride channel in the IM base and tip of kidneys from rats fed a HSD (A) and HUD (B). Blots were probed with a specific antibody to CLC-K. Top: Western blot image. Bottom: summary of densitometric analysis. Values are means ± SD; n = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05, experimental vs. control.

TonEBP abundance was significantly increased in the IM tip of HSD rats (120% of control) (Fig. 5A), while significantly decreased in HUD rats (81% of control) (Fig. 5B). Even though TonEBP abundance in the IM base was not statistically different from controls in either HSD or HUD rats by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5, A and B), the immunoreactivity and nuclear localization of TonEBP in both portions of the IM (especially in IMCD cells) were increased with HSD (Fig. 6, B and E) and decreased with HUD (Fig. 6, C and F).

Fig. 5.

Western blot (top) and densitometric analysis (bottom) of tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein (TonEBP) in IM base and tip from rats fed a HSD (A) and HUD (B). Values are means ± SD; n = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05, experimental vs. control.

Fig. 6.

Immunohistochemical localization of TonEBP in rats fed a HSD and HUD. Asterisks indicate the IMCD. A–C: IMb. D–F: IMt. Bars = 20 μm.

Effect of decrease in total urinary solute induced by LPD or LSD on UT-A1, UT-A3, CLC-K1, and TonEBP proteins.

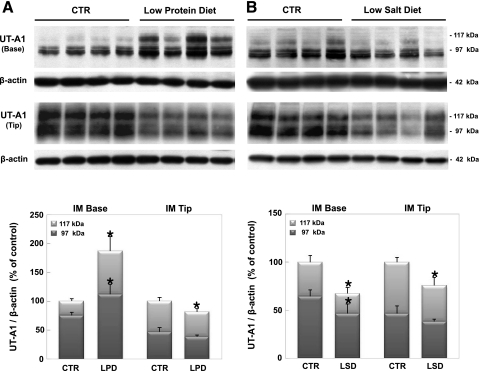

In LPD-fed rats, there was a significant increase in UT-A1 abundance in the IM base (187% of control), but a significant decrease in UT-A1 abundance in the IM tip (81% of control) due to changes in the 117-kDa glycoprotein form (Fig. 7A). On the other hand, a significant decrease in UT-A1 abundance in both portions of the IM occurred (67% of control in IM base, 75% of control in IM tip) in LSD rats (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Western blot analysis of UT-A1 urea transporter in the IM base and tip of rats fed a low-protein diet (LPD; A) and low-salt diet (LSD; B). Blots, probed with a specific antibody to UT-A, show the characteristic 117- and 97-kDa glycoprotein forms of UT-A1. Top: Western blot image. Bottom: summary of densitometric analysis of the total groups with each 117- and 97- kDa band density averaged for each group. Values are means ± SD; n = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05, experimental vs. control.

Immunostaining of UT-A in the kidneys from LPD-fed rats shows the reversal of the normal corticomedullary UT-A1 gradient; the maximal immunoreactivity is at the IM base (Fig. 8B) rather than at the IM tip (Fig. 8E). On the other hand, UT-A immunoreactivity in the kidneys from LSD-fed rats was decreased in both the base (Fig. 8C) and tip (Fig. 8F) of the IM.

Fig. 8.

Light micrographs of 50-μm-thick vibratome sections illustrating immunostaining for UT-A1 in rats fed a LPD and LSD. UT-A1 immunoreactivity is seen in the IMCD (asterisks). A–C: IMb. D–F: IMt. Note the reversal of the normal corticomedullary gradient of UT-A1 immunoreactivity in LPD. Bars = 10 μm.

Although UT-A3 abundance in IM base was significantly increased (128% of control), due to an increase in the 67-kDa glycoprotein, a significant decrease in UT-A3 abundance in the IM tip (81% of control) was observed in LPD rats (Fig. 9A). On the other hand, there was a significant decrease in UT-A3 abundance in the IM base (37% of control) and a significant decrease in the IM tip (63% of control) due to a decrease in the 67-kDa glycoprotein in LSD rats (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Western blot analysis of UT-A3 urea transporter in the IM base and tip of rats fed a LPD (A) and LSD (B). Blots show the characteristic 67- and 44-kDa glycoprotein forms of UT-A3. Top: Western blot image. Bottom: summary of densitometric analysis of the total groups with each 67- and 44- kDa band density averaged for each group. Values are means ± SD; n = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05, experimental vs. control.

There was no change in CLC-K1 abundance in both portions of the IM in LPD and LSD rats (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Western blot analysis of CLC-K1 chloride channel in the IM base and tip of kidneys from rats fed a LPD (A) and LSD (B). Blots were probed with a specific antibody to CLC-K. Top: Western blot image. Bottom: summary of densitometric analysis. The abundance of CLC-K1 in both portions of IM was unchanged by LPD and LSD. Values are means ± SD; n = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05, experimental vs. control.

Neither TonEBP abundance nor immunoreactivity was significantly changed in either LPD or LSD rats (Figs. 11 and 12). The intracellular distribution of TonEBP was also unchanged in the IM cells from rats fed either LPD or LSD. However, some decrease in TonEBP immunoreactivity in the cytoplasm of IMCD cells in LPD was observed (Fig. 12E).

Fig. 11.

Western blot (top) and densitometric analysis (bottom) of TonEBP in IM base and tip from rats fed a LPD (A) and LSD (B). Values are means ± SD; n = 6 rats/group. *P < 0.05, experimental vs. control.

Fig. 12.

Differential interference contrast (DIC) micrographs on 50-μm-thick vibratome sections illustrating immunostaining for TonEBP in rats fed a LPD and LSD. Asterisks point to the IMCD. A–C: IMb. D–F: IMt. Bar = 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

Animals need to rapidly adjust urine osmolality during changes in water and solute intake to maintain plasma osmolality and water homeostasis. Urea and NaCl are the two major solutes that contribute to urine and inner medullary osmolality.

Changes in UT-A1, UT-A3, CLC-K1, and TonEBP in rats fed a HSD.

The rats fed the HSD had a significant decrease in urine urea concentration and in urine osmolality. Although we did not measure interstitial urea or NaCl concentrations in the present study, we previously found a correlation between urine and IM interstitial urea concentrations (12). If IM interstitial urea concentration in HSD rats is low, an increase in NaCl concentration is needed to achieve the same interstitial osmolality as in control rats. Therefore, the increase in CLC-K1 abundance in HSD may be for the promotion of NaCl delivery from the ascending thin limb to the IM interstitium. It is well known that there is an increase in Na-K-2Cl transporter (NKCC2)/BSC1 abundance when sodium delivery to the thick ascending limb is increased (6, 12), suggesting that CLC-K1 abundance may also be upregulated by increased sodium delivery to the ascending thin limb. If the rats with a HSD with low urine urea concentrations have reduced IM interstitial urea and increased NaCl concentrations, it may cause hypertonic stress to the surrounding cells. In turn, TonEBP would enhance the transcription of genes encoding proteins responsible for the accumulation of intracellular organic osmolytes to prevent the shrinkage of the cells (5, 11, 15, 16). Consistent with this hypothesis, the abundance and nuclear localization of TonEBP were increased in the IM of rats fed a HSD. Finally, the increase in UT-A1 and UT-A3 abundance in NaCl diuresis may be explained by hypertonicity-induced, TonEBP-mediated upregulation, since the TonEBP regulates UT-A1 and UT-A3 transcription (17).

Why does a hypertonic (sodium-rich) IM interstitium reabsorb urea? Some in vitro studies have suggested mutually protective roles for these two solutes (18, 23, 27, 33). It is important for the urine concentration to increase osmolality, minimizing the increase in tonicity in the medullary interstitium. If urea is added to the medullary interstitium, the osmolality can be further increased without increasing tonicity because urea evenly distributes to both extracellular and intracellular fluid. In fact, mammals can concentrate urine more effectively than lower class vertebrates such as reptiles or birds, which do not accumulate urea in the renal medulla (4, 19).

Changes in UT-A1, UT-A3, CLC-K1, and TonEBP in rats fed a HUD.

Long-term suppression of endogenous vasopressin with water diuresis induced by feeding of 10% sugar water for 2 wk decreased UT-A1 abundance (14). In this study, osmotic diuresis induced by feeding of 5% HUD significantly decreased UT-A1 abundance, which suggests that the decrease in UT-A1 abundance can occur not only in the absence of vasopressin but also with a high plasma vasopressin level (25).

The rats fed the HUD had a significant increase of urea in the total urinary solute and urine urea concentration since the increase in the total urinary solute was due to an increased excretion of urea. If the high urine urea concentration correlates with a high IM interstitial urea concentration (12), then the rats fed the HUD would not have to increase interstitial NaCl concentration to achieve the same osmolality as control rats.

On the other hand, osmotic diuresis induced by any substance causes increased sodium delivery to the loops of Henle by inhibiting sodium reabsorption from the proximal tubule (20). Therefore, the decrease in CLC-K1 in HUD fed rats may occur to restrict sodium reabsorption from the ascending thin limb to the IM interstitium. The likely consequence of this would be a decreased tonicity of the IM interstitium, decreased abundance of TonEBP (32), and decreased TonEBP-mediated transcription of UT-A1 and UT-A3 (17).

The urinary solute was not different between the rats that received the HSD and those receiving the HUD. The urine volume in the HUD rats, however, was significantly less than in the HSD rats, although still higher than the urine volume of the control rats. This suggests that an appropriate amount of urea is required for urine concentration.

Changes in UT-A1, UT-A3, CLC-K1, and TonEBP in rats fed a LPD.

The rats fed a LPD for 2 wk had a significant decrease in the total urinary solute, but a significant increase in urine volume because of significantly impaired urine concentrating ability. They had a significant decrease in the percentage of urea in the total urinary solute and urine urea concentration, mirroring the responses seen in rats fed the HSD for 2 wk. However, the responses to these similar urinary conditions were very different on a protein level: 1) UT-A1 and UT-A3 abundance was increased in the IM base and decreased in the IM tip with the LPD, whereas UT-A1 and UT-A3 were increased in both the tip and base in HSD-fed rats; 2) the increase in CLC-K1 and TonEBP abundance observed in HSD did not occur in the LPD rats, suggesting that the changes in UT-A1 and UT-A3 abundance observed in the LPD rats was not mediated by TonEBP.

Previous studies showed that feeding rats a LPD for 2 wk induced vasopressin-stimulated urea permeability in rat initial IMCD, which causes a reversal of the normal urinary urea concentration gradient so that the maximum IM urea concentration is at the base of the IM, rather than at the papillary tip (1, 9). In addition, feeding rats a LPD for 3 wk induces sodium-dependent active urea transport in the initial IMCD (10, 22). Mathematical simulations suggest that increases in urea reabsorption across the initial IMCD would decrease maximal concentrating ability by decreasing delivery of urea to the deep IM interstitium (31). Thus the changes in UT-A1 and UT-A3 in LPD fed rats may be an attempt to save urea from excretion rather than for the enhancement of urinary concentrating ability. Urea is the end product of protein metabolism in mammals, but in some species urea can diffuse or be transported across the intestinal lumen (8, 26), where it is split by bacteria and used as a nitrogen source for protein synthesis (7).

The immunohistochemical findings in the present study are consistent with the result from our previous Western blot experiment (12, 29). The increase in UT-A2 protein will increase intrarenal urea recycling during antidiuresis when the medullary interstitial urea concentration is high, thereby preventing the loss of urea from the medulla and maintaining medullary interstitial osmolality (12, 29).

Changes in UT-A1, UT-A3, CLC-K1, and TonEBP in rats fed a LSD.

The rats fed the a LSD had a significant decrease in the total urinary solute and urine volume. The percentage of urea in the total urinary solute and urine urea concentration were significantly increased due to relatively decreased NaCl content. If the high urine urea concentration correlates with a high IM interstitial urea concentration, then the NaCl concentration in the IM interstitium does not need to be high to achieve the desired interstitial osmolality. In contrast to rats fed HUD where CLC-K1 and TonEBP abundances were decreased, the rats fed the LSD had no changes in CLC-K1 and TonEBP. This somewhat different result may be due to a decreased delivery of NaCl to the ascending thin limb of Henle, which makes it unnecessary to restrict NaCl transport from the ascending thin limb to the IM interstitium.

Summary.

During osmotic diuresis, animals try to achieve the same plasma osmolality as control animals by adjusting the composition of the urinary solute and osmolality to maintain water homeostasis. If the low urine urea concentration correlates with a low IM interstitial urea concentration (12) in the rats fed a HSD, then interstitial NaCl concentration would likely increase. This increase could lead to an increase in TonEBP, which in turn may increase UT-A1 and UT-A3, since UT-A1 and UT-A3 transcription is regulated by TonEBP (17). The increase in UT-A1 and UT-A3 would increase urea reabsorption into the interstitium. Conversely, if IM interstitial urea concentration is high, consistent with the high urine urea concentration in rats fed a urea diet (12), they would tend to decrease IM interstitial NaCl concentration, which could decrease TonEBP, UT-A1, and UT-A3 and limit urea accumulation in the IM interstitium. In contrast, rats fed a LPD reabsorb urea to save it from excretion, rather than to enhance urine concentrating ability, as evidenced by the reversal of the normal IM urea gradient (1, 9).

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (R13-2002-005-03001-0) through the Medical Research Center for Cell Death Disease Research Center at The Catholic University of Korea and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01-DK-41707.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work have been published in abstract form (J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 113A, 2007) and presented at the Renal Week 2007 Meeting, San Francisco, CA, October 31–November 5, 2007.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashkar ZM, Martial S, Isozaki T, Price SR, Sands JM. Urea transport in initial IMCD of rats fed a low-protein diet: functional properties and mRNA abundance. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 268: F1218–F1223, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardoux P, Ahloulay M, Maout SL, Bankir L, Trinh-Trang-Tan MM. Aquaporin-2 and urea transporter-A1 are up-regulated in rats with type I diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 44: 637–645, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blount MA, Klein JD, Martin CF, Tchapyjnikov D, Sands JM. Forskolin stimulates phosphorylation and membrane accumulation of UT-A3. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1308–F1313, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun EJ, Reimer PR. Structure of avian loop of Henle as related to countercurrent multiplication system. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 255: F500–F512, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai Q, Ferraris JD, Burg MB. High NaCl increase TonEBP/OREBP mRNA and protein by stabilizing its mRNA. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F803–F807, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ecelbarger VA, Terris J, Hoyer JR, Nielsen S, Wade JB, Knepper MA. Localization and regulation of the rat renal Na+-K+-Cl− cotransporter, BSC-1. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 271: F619–F628, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuller MF, Reeds PJ. Nitrogen cycling in the gut. Annu Rev Nutr 18: 385–411, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue H, Kozlowski SD, Klein JD, Bailey JL, Sands JM, Bagnasco SM. Regulated expression of renal and intestinal UT-B urea transporter in response to varying urea load. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F451–F458, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isozaki T, Gillin AG, Swanson CE, Sands JM. Protein restriction sequentially induces new urea transport processes in rat initial IMCDs. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 266: F756–F761, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isozaki T, Lea JP, Tumlin JA, Sands JM. Sodium-dependent net urea transport in rat initial IMCDs. J Clin Invest 94: 1513–1517, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeon US, Kim JA, Shee MR, Kwon HM. How tonicity regulates genes: story of TonEBP transcriptional activator. Acta Physiol 187: 241–247, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim D, Klein JD, Racine S, Murrell BP, Sands JM. Urea may regulate urea transport protein abundance during osmotic diuresis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F188–F197, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim D, Sands JM, Klein JD. Changes in renal medullary transport proteins during uncontrolled diabetes mellitus in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F303–F309, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim D, Sands JM, Klein JD. Role of vasopressin in diabetes mellitus-induced changes in medullary transport proteins involved in urine concentration in Brattleboro rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F760–F766, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HW, Kim WY, Song HK, Yanf CW, Han KH, Kwon HM, Kim J. Sequential expression of NKCC2, TonEBP, aldose reductase, and urea transporter-A in developing mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F269–F277, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyakawa H, Woo SK, Dahl SC, Handler JS, Kwon HM. Tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein, a Rel-like protein that stimulates transcription in response to hypertonicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 2538–2542, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakayama Y, Peng T, Sands JM, Bagnasco SM. The TonE/TonEBP pathway mediates tonicity-responsive regulation of UT-A urea transporter expression. J Biol Chem 275: 38275–38280, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neuhofer W, Muller E, Burger-Kentischer A, Fraek ML, Thurau K, Beck F. Pretreatment with hypertonic NaCl protects MDCK cells against high urea concentrations. Pflügers Arch 435: 407–414, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimura H, Koseki C, Imai M, Braun EJ. Sodium chloride and water transport in the thin descending limb of Henle of the quail. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 257: F994–F1002, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okusa MD, Ellison DH. Physiology and pathophysiology of diuretic action. In: The Kidney: Physiology and Pathophysiology, edited by Seldin DW and Giebisch G. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2000, p. 2877–2922.

- 21.Sands JM, Layton HE. Urine concentrating mechanism and its regulation. In: The Kidney: Physiology and Pathophysiology, edited by Seldin DW and Giebisch G. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2000, p. 1175–1216.

- 22.Sands JM, Martial S, Isozaki T. Active urea transport in the rat initial inner medullary collecting duct: functional characterization and initial expression cloning. Kidney Int 49: 1611–1614, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos BC, Chevaile A, Herbert MJ, Zagajeski J, Gullans SR. A combination of NaCl and urea enhances survival of IMCD cells to hyperosmolality. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F1167–F1173, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt-Nielsen B, Graves B, Roth J. Water removal and solute additions determining increases in renal medullary osmolality. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 244: F472–F482, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shayakul C, Smith CP, Mackenzie HS, Lee WS, Brown D, Hediger MA. Long-term regulation of urea transporter expression by vasopressin in Brattleboro rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F620–F627, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart GS, Fenton RA, Thevenod F, Smith CP. Urea movement across mouse colonic plasma membrane is mediated by UT-A urea transporters. Gastroenterology 126: 765–773, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian W, Cohen DM. Urea inhibits hypertonicity-inducible TonEBP expression and action. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F904–F912, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uchida S In vivo role of CLC chloride channels in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F802–F808, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wade JB, Lee AJ, Liu J, Ecelbarger CA, Mitchell C, Bradford AD, Terris J, Kim GH, Knepper MA. UT-A2: a 55-kDa urea transporter protein in thin descending limb of Henle's loop whose abundance is regulated by vasopressin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F52–F62, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waldegger S, Jentsch TJ. From tonus to tonicity: physiology of CLC chloride channels. J Am Soc Nephrol 11:1331–1339, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wexler A, Kalaba RE, Marsh DJ. Three dimensional anatomy and renal concentrating mechanism. I. Modeling results. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F368–F383, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woo SK, Dahl SC, Handler JS, Kwon HM. Bidirectional regulation of tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein in response to changes in tonicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F1006–F1012, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang A, Tian W, Cohen DM. Urea protects from the proapoptotic effect of NaCl in renal medullary cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F345–F352, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]