Abstract

Communication between endothelial and mural cells (smooth muscle cells, pericytes, and fibroblasts) can dictate blood vessel size and shape during angiogenesis, and control the functional aspects of mature blood vessels, by determining things such as contractile properties. The ability of these different cell types to regulate each other's activities led us to ask how their interactions directly modulate gene expression. To address this, we utilized a three-dimensional model of angiogenesis and screened for genes whose expression was altered under coculture conditions. Using a BeadChip array, we identified 323 genes that were uniquely regulated when endothelial cells and mural cells (fibroblasts) were cultured together. Data mining tools revealed that differential expression of genes from the integrin, blood coagulation, and angiogenesis pathways were overrepresented in coculture conditions. Scans of the promoters of these differentially modulated genes identified a multitude of conserved C promoter binding factor (CBF)1/CSL elements, implicating Notch signaling in their regulation. Accordingly, inhibition of the Notch pathway with γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT or NOTCH3-specific small interfering RNA blocked the coculture-induced regulation of several of these genes in fibroblasts. These data show that coculturing of endothelial cells and fibroblasts causes profound changes in gene expression and suggest that Notch signaling is a critical mediator of the resultant transcription.

Keywords: endothelial cells, fibroblasts, mural cells, microarray

heterotypic cell communication is a vital component of many organ systems, including the vasculature. Mural cells, identified as smooth muscle cells, pericytes, and fibroblasts, must interact with endothelial cells in defined ways to produce functional vessels of the appropriate size, pattern, and physiology (2, 24, 25). While the importance of these interactions is well established, how these different cells communicate with each other remains poorly understood. During blood vessel formation, endothelial cells are prompted to undergo tubulogenesis, creating a network of properly spaced lumens designed to carry blood throughout the body (4, 25). Lumen formation is followed by the recruitment of mural cells that ensheathe the vessel, providing structural support and contractile abilities that facilitate flow (4, 25). Although easy to envision, this stepwise depiction of vessel formation is an oversimplification. More accurately, during vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, endothelial and mural cells are in constant communication, and together their associations act to shape the vasculature.

Mural cells have been shown to control vessel assembly by regulating endothelial cell proliferation, migration, sprouting, and regression (8, 28, 33, 35, 38, 44, 51). Similarly, endothelial cells can modulate mural cell activities by also regulating proliferation and migration, in addition to differentiation and contractile function (7, 37, 45). Yet there is limited knowledge of the factors that regulate the communication between these cell types. Growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-B, transforming growth factor-β, and the angiopoietins have been shown to mediate vascular cell cross talk (2, 7, 24). Additionally, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their inhibitors (tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases, TIMPs) govern their communication (10, 24, 33, 44), while Notch signaling has also been shown to regulate endothelial and mural cell interactions (19, 21, 43). The importance of these mediators and those that remain undiscovered cannot be dismissed, for they are involved in regulatory cascades, which participate in altering patterns of gene expression across cell types. In fact, these mediators do not act alone, and it is a combination of signaling events emanating from endothelial cells to mural cells or vice versa that ultimately determines how these cells react (26, 53). Thus understanding the global effects these cells have on one another is important in defining the individual contributors that regulate their phenotypes.

In this study, we performed a microarray analysis on cells within a three-dimensional angiogenesis assay. We identified 323 genes that were upregulated or downregulated twofold or greater when endothelial cells and fibroblasts were cultured together versus when these cells were cultured alone. Utilizing gene ontogeny clustering, we found that genes from the integrin, blood coagulation, and angiogenesis pathways were overrepresented in cocultured cells, signifying the activation of specific pathways by this heterotypic cell interaction. Additionally, evaluation of promoter regions from differentially regulated genes identified an overabundance of conserved C promoter factor (CBF)1/CSL motifs (3, 29) linking Notch signaling to their regulation. To test the role of Notch, we blocked its functions with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT or NOTCH3 small interfering RNA (siRNA) and demonstrated that inhibition of Notch activity prevented the modulation of select genes under coculture conditions. Our results show that endothelial cell-fibroblast cell communication causes significant changes in gene expression, and further implicate Notch signaling as an important component of this transcriptional regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Primary cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from Lonza and grown in complete EBM-2 medium. Human dermal neonatal fibroblasts (HDFNs) were obtained from Cascade Biologics and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Mediatech) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone) and 100 IU/ml penicillin-streptomycin. All cultures were maintained in humidified 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Angiogenesis assays were performed as described previously (33). Cells for experiments, whether cultured alone or together, were placed in identical assay media, which consisted of EBM-2 supplemented with all “bullet kit” components except FBS, VEGF, and basic FGF and supplemented with 1% FBS and 30 ng/ml VEGF-A165 (Peprotech). For two-dimensional coculture, 6 × 104 fibroblasts were plated in a 12-well dish with 6 × 104 HUVECs and cultured for 48 h, after which RNA was harvested. γ-Secretase inhibitor DAPT (Calbiochem) was added at the time of plating to indicated samples.

To separate endothelial cells and fibroblasts, anti-platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM)-1-conjugated Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were used according to manufacturer's instructions. The separated cells were then processed for quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). We confirmed adequacy of separation by assessing cell-specific marker expression (see Fig. 3) and by replating the cells for 5 h and then counting cells that were labeled, using the endothelium-specific lectin and fibroblast-loaded tracker dye (as described for cell staining). The fibroblast population was >99% pure, and the endothelial cells were >96% pure (data not shown). For conditioned medium experiments, 6 × 104 fibroblasts and 6 × 104 endothelial cells were plated separately. Medium from these cells was collected after 24 and 48 h and added to endothelial cells and fibroblasts. The total time that cells were incubated in conditioned media was 48 h.

Cell staining.

Collagen-embedded cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde overnight and either stained with 10% hematoxylin or incubated with 10 μg/ml tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-labeled lectin (Ulex europaeus UEA-I, Sigma) for 1 h. For prelabeling fibroblasts, cells were loaded with CellTracker Dye Green CMFDA (10 μM, Molecular Probes) for 30 min in serum-free medium and used directly in angiogenesis assays. Cells were mounted in AquaMount (Lerner Labs) and visualized on a Leica DM5000B microscope.

Microarray.

Total RNA was isolated by TRIzol (Invitrogen) from cells cultured for 5 days in a three-dimensional angiogenesis assay. RNA was further purified with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and quantified, and the HUVEC and HDFN samples that were cultured alone were mixed at a 1-to-2 ratio to parallel the ratio determined in the coculture samples. The samples were then sent to Illumina (www.illumina.com) for analysis of three replicates cultured alone and mixed and three cocultured samples. Illumina performed quality control analysis on all RNA samples and subsequent cRNA RiboGreen quantitation and Agilent Bioanalyzer assessment for integrity. Sentrix Human-6 BeadChips were used for analysis (13). These BeadChips have >46,000 probes derived from human genes in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Reference Sequence (RefSeq) and UniGene databases. Data analysis was performed with BeadStudio software (Illumina) (13, 14). Genes with detection scores of >0.99 in all samples were evaluated. Rank invariant normalization was used for differential analysis with Illumina custom error model. Only genes that had differential signal intensities with P values of <0.01 were analyzed further.

qPCR.

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent and reverse transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) to generate cDNA. qPCR was performed with a StepOne PCR system (Applied Biosystems) with SYBR Green. The fold difference in transcripts was calculated by the ΔΔCT method (where CT is threshold cycle), with 18S as the internal control. After PCR, a melting curve was constructed in the range of 60–95°C to confirm the specificity of the amplification products.

Transfections with siRNA.

HDFNs were transiently transfected in a 12-well plate at 6 × 104 with Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. NOTCH3 siRNA was synthesized by IDT with the sequence AAC UGC GAA GUG AAC AUU G; GUC AAU GUU CAC UUC GCA G and used at 100 nM. Control siRNA was obtained from Invitrogen and used at equivalent concentration. Twenty-four hours after transfection, 6 × 104 HUVECs were added and incubated for 48 h.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons between qPCR data sets were made with Student's t-test. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05, and data are presented as means ± SE. Data shown are representative of at least two independent experiments performed in duplicate.

RESULTS

Endothelial cells and fibroblasts communicate during angiogenesis.

Endothelial cells and mural cells such as fibroblasts are known to interact, and we (33) along with others (8, 28, 35, 38, 44, 51) have demonstrated that this interaction has obvious consequences on blood vessel formation in vitro. Using a collagen I-based three-dimensional matrix, we cultured HUVECs with or without HDFNs in an angiogenesis assay. These fibroblasts were used to mimic naive mesenchymal cells that would take on vascular properties under coculture conditions. Fibroblasts are known to have an important role in wound healing and angiogenesis (22). In the presence of fibroblasts, endothelial cells formed a more extensive network of vessels, as can be seen by staining with hematoxylin, which lightly stains all cells, or by using an endothelial-specific lectin (Fig. 1A). No vessels were formed by fibroblasts alone, which existed in suspended monolayers in the absence of endothelial cells. The interaction of these cells, as we had anticipated, appeared to be reciprocal because the fibroblasts could be seen surrounding newly formed vessels as a consequence of recruitment (Fig. 1B). Most endothelium-derived tube structures were encased by fibroblasts, although the number of fibroblasts found around individual vessels varied. Given that these cells were physically responding to one another, we hypothesized that these interactions were causing significant changes in gene expression. We further predicted that these molecular changes would be responsible for how these cells behave toward each other, as well as producing important factors that facilitate the function of these cells in mature vessels. As a means to address this, we performed a microarray screen to identify genes that were uniquely regulated when these two cell types were cultured together under angiogenic conditions.

Fig. 1.

Angiogenesis assays reveal cell-cell communication. A: human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human dermal neonatal fibroblasts (HDFNs) were cultured alone or cocultured (Coculture) in a 3-dimensional collagen I matrix for 5 days, fixed, and stained with hematoxylin or tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-labeled endothelium-specific lectin (red) and DAPI (blue). B: triple labeling of cocultured cells with lectin (red), a preloaded cell tracker dye (green) to visualize HDFNs surrounding vessels, and DAPI (blue).

Microarray to detect genes regulated by coculturing cells in an angiogenesis assay.

For microarray analysis, we cultured cells alone or together under identical conditions in a three-dimensional angiogenesis assay and allowed vessels to form for 5 days, as shown in Fig. 1. After this, total RNA was isolated from the collagen-embedded cells. Before isolating samples for the array, we determined that the approximate ratio of endothelial cells and fibroblasts in the coculture samples at the end of the 5-day period was ∼1:2, with twice as much fibroblast RNA compared with endothelial cell RNA (data not shown). We then mixed the RNA from the two cell types cultured alone, using that same ratio (Fig. 2A), which allowed us to directly measure the amounts of transcripts on the array from comparably mixed samples. The limitation of this strategy was that it would not allow us to immediately determine in which cell type the gene expression changes were occurring, and we would potentially overlook genes whose expression was being reciprocally altered in the different cells. The microarray was performed by Illumina, using Human-6 Expression BeadChips that contained >46,000 probes derived from human genes (13). Samples were run in triplicate, and the data were averaged over the three sets. From this, we identified a total of 323 transcripts that were differentially expressed twofold or greater with P < 0.01 between the cells cultured alone versus those cocultured (Fig. 2B). Of those 323, 192 showed an increase in expression in the cocultured cells, while 131 were decreased in the cocultured sample (Supplemental Fig. S1).1

Fig. 2.

Microarray sample preparation and graph. A: diagram of method used to produce equivalent RNA samples for cells cultured alone and together. The microgram ratio of endothelial to fibroblast RNA in cocultured samples was determined to be 1:2. After angiogenesis assays, cells were collected and RNA was purified. Endothelial cell and fibroblast RNA from cells cultured separately were then mixed at a 1-to-2 ratio to produce a sample that was comparative to the cocultured sample. B: graph of the average signal intensities of genes detected on Illumina BeadChips from cRNA of cocultured samples (y-axis) vs. cRNA derived from cells cultured alone (x-axis). Gray dots represent all genes on the BeadChip, and black dots mark only those having intensities >0.99 and 2-fold differential expression with P < 0.01.

As predicted, we observed a robust difference in expression profiles between cells that were cocultured and cells cultured alone, indicating an inherent ability of these cells to modulate each other's activities. We verified the expression patterns of 55 (17% of total) of these genes by qPCR and confirmed that 52 (95%) of these transcripts exhibited differential expression that was consistent with the microarray (Supplemental Fig. S1). In evaluating these genes, we also sought to determine in which cell type transcript expression was being altered. We employed anti-PECAM-1-conjugated beads to separate the two cell populations from one another and confirmed the separation effectiveness by examining the cell-specific markers PECAM-1 for endothelial cells and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)β, which was increased threefold in the array, to detect fibroblasts (Fig. 3). Of those tested, the majority (36) were differentially regulated only in fibroblasts. Although the array was performed with RNA extracted from cells in three-dimensional collagen, we determined that these 52 genes were similarly modulated in two dimensions, where the cells were plated together or apart under identical medium conditions. Hence, overall the coculturing of these cells appeared to be sufficient to alter gene expression, and these changes did not require the morphogenic events of tube formation in a three-dimensional collagen matrix.

Fig. 3.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of genes expressed in HUVECs and HDFNs cultured alone or together. To evaluate transcript levels in individual cell types that had been cocultured, cells were separated with anti-platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM)-1-conjugated magnetic beads. Verification of separation efficiency was determined by using the cell-specific marker genes PECAM-1 for endothelial cells and PDGF receptor β (PDGFRβ) to detect fibroblasts. Note that there are barely detectable levels of expression of these marker genes in the other cell type fraction after coculture and separation. A, cells cultured alone; CO, cells cocultured and separated. *P < 0.05.

Gene ontology reveals select pathways that are stimulated by coculturing vascular cells.

As a means to assess the global changes that were occurring under coculture conditions, we utilized the Protein ANalysis THrough Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER) Classification System (www.pantherdb.org) to identify signaling pathways that were overrepresented in our list of array genes (6, 34). The array list was compared with a reference list composed of 23,481 known genes from the human genome that had previously been classified into one or more pathways. Using binomial statistics, we identified three pathways that were overrepresented from the differentially expressed genes with P values of <0.01. Shown in Table 1 are the identified pathways, the number of Homo sapiens genes placed within these pathways, the number found in the reference list, and the number found in the array data. Differential and cell type-specific expression of these pathway genes was determined by qPCR as demonstrated in Fig. 3 and shown in Table 2. The pathway with the most genes present in our array data set with the lowest P value was the integrin family with 12 members. In addition to integrin receptors, transcripts in this class included their extracellular ligands and signaling molecules (49). Several of the collagen genes (COL), the laminin β3 chain (LAMB3), integrin receptor subunits α1 (ITGA1) and α3 (ITGA3), as well as an intracellular mediator of integrin signaling LIMS2 (PINCH2) (30), were upregulated. Consistent with the overall profile of the verified array genes, the majority of these were altered in fibroblasts, with the COL5A3 splice variant showing the largest increase (15-fold). LAMB3 was the only factor that exhibited a rise in cocultured endothelial cells, whereas COL18A1 and LIMS2 displayed increases in both cell types. COL10A1, a nonfibrillar collagen (48), was the only gene in this group whose expression was decreased; however, analysis of the cells after separation revealed that although its expression decreased in fibroblasts, endothelial cells had a significant increase in this collagen isoform (2.6-fold). The upsurge in these integrin-associated genes implies that the interaction of these two cell types is a strong stimulus for the production of extracellular matrix and the signaling molecules that mediate communication between the cell and its surrounding environment. Blood vessels require a complex extracellular environment that facilitates barrier function and conveys mechanical information to these pressure-sensing cells (10, 27, 46). These results suggest that their interaction serves as a trigger, which prompts them to produce molecules needed for an intact blood vessel.

Table 1.

PANTHER classification system of overrepresented pathways

| Pathway | NCBI Homo sapiens Genes | No. in Array | No. Expected | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrin signaling | 227 | 12 | 2.42 | 0.0013 |

| Blood coagulation | 55 | 6 | 0.59 | 0.0054 |

| Angiogenesis | 229 | 11 | 2.44 | 0.0073 |

Table 2.

Pathway genes with differential expression

| Gene Symbol | Fold Up/Down | Cell Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrin pathway | ||||

| COL5A2 | +2.2 | ND | ||

| COL18A1 | +2.1 | Both‡ +1.8, +3.2 | ||

| ITGA1 | +4.2 | Fibroblast | ||

| LAMB3 | +2.5 | Endothelial | ||

| LIMS2 | +2.5 | Both‡ +1.4, +3.3 | ||

| ITGA3 | +3.4 | Fibroblast | ||

| COL7A1 | +2.6 | Fibroblast | ||

| COL11A1 | +3.4 | Fibroblast | ||

| COL1A1 | +4.3 | Fibroblast | ||

| COL5A1 | +2.7 | ND | ||

| COL5A3 | +15.6 | Fibroblast | ||

| COL10A1 | −2.6 | Fibroblast* | ||

| Blood coagulation pathway | ||||

| TFPI2 | −3.2 | Endothelial | ||

| PLAT | +2.1 | Fibroblast | ||

| SERPINE1 | +2.1 | Fibroblast† | ||

| GP1BB | +3.3 | Endothelial | ||

| F3 | +3.8 | Endothelial | ||

| HGF | −2.4 | Fibroblast | ||

| Angiogenesis pathway | ||||

| PDGFD | −2.4 | Fibroblast* | ||

| FLJ20967 | −2.2 | Fibroblast | ||

| PLA2G4A | −2.4 | Endothelial | ||

| FGFR3 | +9.6 | Both‡ +3.3, +2.3 | ||

| SFRP1 | −3.9 | Fibroblast | ||

| HSPB2 | +2.2 | Fibroblast | ||

| PDGFRB | +3.4 | Fibroblast | ||

| WNT5A | +2.5 | Fibroblast | ||

| SPHK1 | +2.8 | Fibroblast | ||

| NOTCH3 | +8.5 | Fibroblast | ||

ND, not determined.

Increased in endothelial cells (2.6-fold);

decreased in endothelial cells (2.2-fold);

increased in endothelial cells and fibroblasts, respectively.

The blood coagulation group was also found to be overrepresented within our array genes, with six genes from this class showing differential expression. Of these genes, two were upregulated in cocultured endothelial cells (F3 and GP1BB) and two were upregulated in fibroblasts (PLAT and SERPINE1). One gene was decreased in cocultured endothelial cells (TFPI2), and another was decreased in fibroblasts (HGF). The modulation of this class of factors suggests that vascular cell-cell interactions promote the activation of pathways that will be needed when blood flow commences. F3/TF or tissue factor is an initiator of the blood coagulation cascade leading to fibrin deposition and platelet activation (9), and interestingly an inhibitor of F3, tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 (TFPI-2) (5), exhibited a decrease in expression. Tissue plasminogen activator (PLAT or TPA) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (SERPINE1 or PAI-1), both important components of fibrinolysis, were increased in fibroblasts (36). Fibroblasts also induced the expression of GP1BB in endothelial cells, which is a component of the surface receptor for von Willebrand factor and mediates adhesion of platelets to damaged arterial walls (41). In addition, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), a protein with structural homology to plasminogens, was decreased in fibroblasts (47). HGF also fell under the angiogenesis pathway for its reported angiogenic capabilities.

The final overrepresented group of genes was from the angiogenesis pathway, with 11 genes from the array data set in this category and all but 1 (PLA2G4A) being modulated in fibroblasts. This pathway was somewhat expected, given that our screen utilized endothelial cells undergoing morphogenesis in the presence or absence of fibroblasts (Fig. 1). The angiogenesis group was composed of signaling mediators that included HGF and PDGF-D, both of which were repressed under coculture conditions, despite evidence that they are proangiogenic (31, 47). WNT5A, a member of the secreted Wingless/Wnt signaling family, was increased, while a soluble Wnt receptor antagonist (SFRP1) was decreased. The Wnt family has a well-established role in regulating endothelial cell activities, and so induction of WNT5A by endothelial cells in neighboring fibroblasts may serve to signal back to endothelial cells with instructional information (18, 56). Several receptors, including fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3), PDGFRβ, and NOTCH3, were increased, all of which have been linked to some aspect of vascular development. PDGFRβ is a major contributor in the recruitment of mural cells by endothelium-expressed PDGF-B (1). Its upregulation implies that endothelial cells purposely promote recruitment by modulating receptor availability. NOTCH3 has mainly been linked to governing smooth muscle maturation (11, 52), and the ability of endothelial cells to elevate its expression in mural cells indicates that it may be a mediator of endothelium-induced phenotypic modulation. Although FGFR3 has been implicated in angiogenic processes, its potential role in this circumstance is not clear (39). Its expression was increased in both endothelial cells and fibroblasts, indicating that FGF signaling could be activated bidirectionally and may exert similar effects on these cells. In addition to these ligands and receptors, the cytoplasmic protein sphingosine kinase-1 (SPHK1), which facilitates the production of sphingosine-1 phosphate, a well-described inducer of angiogenesis, was increased (32). Heat shock protein 27 (HSPB2), which is involved in migration events that facilitate angiogenesis, also was increased in fibroblasts (20, 42). The only factor from this class that was exclusively regulated in endothelial cells was cytoplasmic phospholipase A2α (PLA2G4A), which was decreased twofold. PLA2G4A hydrolyzes arachidonic acid, leading to prostaglandin production and COX-2, a proangiogenic factor (12, 54). In examining the relevance of the individual factor's expression it is important to consider that angiogenesis is a dynamic process, and that it is the balance of activator and inhibitor molecules that determines size, shape, and maturity of blood vessels. Overall, from these analyses we were able to discover specific pathways that were preferentially activated by the interaction of these two cell types. The data offer insight into how these cells communicate by revealing that certain pathways are modulated not in one but in both cell types.

Conditioned medium regulates a select few genes.

The coculture of these different cell types revealed that their presence affected gene expression of the other cell type; however, it did not tell us anything about the mediators involved in this regulation. To address this, we performed conditioned medium experiments, in which medium from one cell type was added to the other cell type and the expression of each of the genes identified in the overrepresented pathways was examined. Of the 26 genes examined, only PDGFD and HSPB2 exhibited modulation in fibroblasts by endothelial cell-conditioned medium that was consistent with our previous coculture analysis (Fig. 4). Interestingly, in two instances we observed changes in gene expression that were the opposite of what we had confirmed under coculture conditions. In fibroblasts endothelium-conditioned medium decreased COL5A3 expression, while LAMB3 levels decreased in endothelial cells on treatment with fibroblast-conditioned medium (Fig. 4). Thus these data indicate that multiple signaling mediators, which include both soluble and membrane-bound factors, regulate these genes.

Fig. 4.

Conditioned medium modulates select genes. Expression analysis by qPCR shows that endothelium-conditioned medium (HUVECs) added to fibroblasts causes a decrease in PDGFD and an increase in HSPB2 expression, similar to that observed from the array data. Fibroblast-conditioned medium (HDFNs) was used as control. In contrast, endothelium-conditioned medium reduced COL5A3 expression in fibroblasts, while fibroblast-conditioned medium downregulated the expression of LAMB3 in endothelial cells. *P < 0.05.

Promoter scans uncover a potential role for Notch in coculture-induced gene expression.

Given that certain pathways were preferentially activated by coculture conditions, we next wanted to determine whether these differentially expressed genes were governed by common transcriptional mechanisms that might be linked to these pathways. To address this, we utilized Whole Genome rVISTA to search for conserved binding elements within the promoters of array genes (16, 55). This search tool uses a database of transcription factor binding sites found in the promoter regions (5,000 bases upstream) that are conserved in the alignment of human and mouse genes. A list of genes can be screened for common elements, and the overabundance of these is statistically determined. We performed these analyses separately on genes that were upregulated and downregulated in cocultured cells, with the assumption that the regulators of these genes acting through common binding motifs would likely be activators and repressors, respectively.

In the upregulated class, the most overrepresented binding element was a CBF1 site. CBF1 (CSL/RBPJK) is a transcriptional repressor that turns into an activator when complexed with the intracellular domain of Notch receptors (3, 29). This was particularly intriguing, because NOTCH3 was strongly induced in fibroblasts by approximately ninefold and was one of the factors present in the class of angiogenesis pathway genes (Table 2). Of the 192 genes increased in the cocultured samples, 124 had identifiable conserved promoters that were screened, and of those 92 or 75% had one or more conserved CBF1 sites (Table 3). One of these was the known Notch target gene, HEYL (15), which was increased in our array >10-fold (Fig. 5 and Supplemental Fig. S1). In comparison, CBF1 sites were not found in overabundance in the genes that were downregulated. Genes with decreased expression in cocultured samples had statistically more GATA3 elements within their promoters. Of the 131 downregulated genes 104 had screenable promoters, and of those 75 (72%) had GATA3 motifs (Table 3). GATA3 has a well-described role in T-cell development and more recently has been implicated in functioning in other systems (23). While it is a known transcriptional activator, it also can repress transcription in the context of other factors (23, 57). Interestingly, it has been shown to repress VCAM-1 expression in endothelial cells (50), and therefore GATA3 might be acting predominantly in a repressive capacity under these circumstances.

Table 3.

Whole Genome rVISTA to identify overrepresented conserved binding elements

| Gene Group | Screened Promoters | Most Overrepresented Conserved Element, Total No. | No. of Genes with ≥1 Element(s) | Total No. of Hits on Genome | −log10 (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | 124 | CBF1 | 92 | 49039 | 17.414 |

| genes (192) | 389 | ||||

| Downregulated | 104 | GATA3 | 75 | 40302 | 7.8183 |

| genes (131) | 248 |

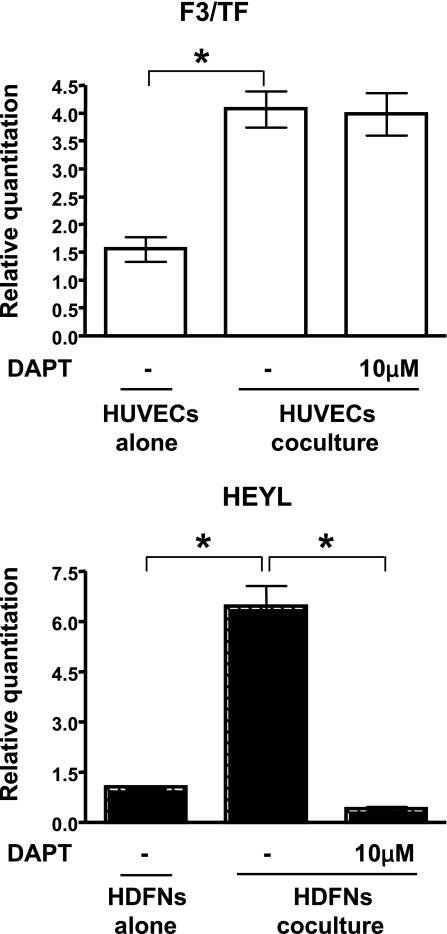

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of Notch signaling by DAPT. qPCR analysis shows expression of a representative gene that was modulated in HUVECs (F3/TF) and HDFNs (HEYL) under coculture conditions. Cocultured cells were treated with vehicle or DAPT and separated, and RNA was extracted for qPCR. Untreated cells cultured alone were used as a reference for the effects of DAPT treatment. The upregulation of HEYL was inhibited in fibroblasts by DAPT, while the increase of F3/TF in endothelial cells was not affected. *P < 0.01.

Inhibition of Notch signaling blocks endothelium-induced expression in fibroblasts.

The presence of CBF1 binding elements in so many of the upregulated genes was compelling because of the recognized importance of Notch in angiogenesis and vascular development (19). To further investigate the potential importance of these binding sites and Notch signaling in the regulation of these genes, we performed inhibitor studies to block Notch function. The γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT, which prevents cleavage of the Notch intracellular domain after ligand binding, was used to eliminate its transcriptional activity (17). Endothelial cells and fibroblasts were cultured together in the presence or absence of DAPT and separated as described above, and the expression levels of genes from the previously identified pathways (Table 2) were examined. Shown in Fig. 5 are representative graphs of these analyses. Blocking Notch signaling had no effect on genes that were either up- or downregulated in endothelial cells (Table 4). On the other hand, 8 of 16 upregulated genes in fibroblasts were strongly inhibited by disruption of Notch signaling (Table 4). Moreover, SFRP1, which was downregulated in fibroblasts by cocultured endothelial cells, remained elevated with Notch inhibition, indicating that this gene might be repressed by the Notch target genes HES/HEY, which are transcriptional repressors (15). The lack of an effect on endothelium-specific expression compared with the dramatic effect in fibroblasts implies that Notch signaling is unidirectional, with endothelial cells sending the signal that is received by fibroblasts. We were initially prompted to examine the Notch pathway because of the presence of CBF1 binding sites. Therefore we specifically scanned the pathway genes for conserved CBF1 sites and found that 24 of 26 of these genes contained CBF1 elements, yet only 8 were affected by DAPT treatment. Only TFPI2 and FLJ20967, which were downregulated in endothelial cells and fibroblasts, respectively, lacked conserved CBF1 motifs within their promoters. Hence, the presence of a CBF1 site was not sufficient to cause these genes to be regulated by Notch, indicating a context-dependent function. Overall, these data suggest that Notch activity is a critical component in establishing the expression profiles generated by the interaction of endothelial cells and fibroblasts. However, the presence of conserved CBF1 binding sites within their promoters was not a strong predictor of their ability to be regulated by Notch signaling.

Table 4.

Effect of DAPT treatment on coculture-dependent modulation

| Gene Symbol | Fold Up/Down | Cell Type | DAPT Treatment P < 0.01 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrin pathway | ||||||

| COL18A1 | +2.1 | Both | Yes/No* | |||

| ITGA1 | +4.2 | Fibroblast | Yes | |||

| LAMB3 | +2.5 | Endothelial | No | |||

| LIMS2 | +2.5 | Both | No | |||

| ITGA3 | +3.4 | Fibroblast | Yes | |||

| COL7A1 | +2.6 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| COL11A1 | +3.4 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| COL1A1 | +4.3 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| COL5A3 | +15.6 | Fibroblast | Yes | |||

| COL10A1 | −2.6 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| Blood coagulation pathway | ||||||

| TFPI2 | −3.2 | Endothelial | No | |||

| PLAT | +2.1 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| SERPINE1 | +2.1 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| GP1BB | +3.3 | Endothelial | No | |||

| F3 | +3.8 | Endothelial | No | |||

| HGF | −2.4 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| Angiogenesis pathway | ||||||

| PDGFD | −2.4 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| FLJ20967 | −2.2 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| PLA2G4A | −2.4 | Endothelial | No | |||

| FGFR3 | +9.6 | Both | No | |||

| SFRP1 | −3.9 | Fibroblast | Yes | |||

| HSPB2 | +2.2 | Fibroblast | No | |||

| PDGFRB | +3.4 | Fibroblast | Yes | |||

| WNT5A | +2.5 | Fibroblast | Yes | |||

| SPHK1 | +2.8 | Fibroblast | Yes | |||

| NOTCH3 | +8.5 | Fibroblast | Yes | |||

Blocked upregulation in fibroblasts but not in endothelial cells.

Our data indicated that Notch signaling was important for the regulation of a subset of the genes modulated in fibroblasts. Because NOTCH3 expression was increased in these cells, we tested whether NOTCH3 was directly responsible for their expression. To do this, we transfected NOTCH3-specific or control siRNA into fibroblasts cocultured with endothelial cells and then examined expression of the genes that were affected by DAPT treatment. As shown in Fig. 6, knockdown of NOTCH3 resulted in inhibition of modulation by cocultured endothelial cells of six of the eight genes. Thus these results directly demonstrate that NOTCH3 is an important component in the regulation of a subset of genes whose expression is controlled by endothelial cell-fibroblast interactions.

Fig. 6.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) to block NOTCH3 in fibroblasts. NOTCH3-specific siRNA (N3) or control siRNA (C) was transfected into HDFNs, and 24 h later HUVECs were added to indicated samples and incubated for an additional 48 h. RNA was harvested, and qPCR was performed. Top: effectiveness of the NOTCH3 siRNA to abolish its expression and that of a known target gene, HEYL. Bottom: effect of NOTCH3 knockdown on DAPT-sensitive gene expression. *P < 0.05; ns, not significant.

DISCUSSION

The interaction of the cells that make up the vasculature is important for the proper formation and function of blood vessels. Although it is well established that these heterotypic interactions are vital, there is still much to learn about the nature of their relationships. For instance, what consequence does their physical association have in gene expression patterns, and, in turn, how does this affect their ability to communicate? Our data show that endothelial cells and fibroblasts, which we used as naive mural cells, exhibit strong responses to one another in a three-dimensional model of angiogenesis. The fibroblasts robustly enhance vessel formation, inducing a more extensive vascular network, which may be due in part to enhanced morphogenesis (33). These effects of fibroblasts on endothelial cells are well known. The endothelial cells attract the fibroblasts that encase the nascent vessel in what appears to be a mimic of the in vivo circumstance, where mural cells undergo recruitment that is mediated by PDGF-B (1). But whether these fibroblasts are responding as true vascular support cells under these conditions remains to be determined.

Using this three-dimensional model of angiogenesis, we screened for genes that were regulated under these coculture conditions. As predicted, we identified a group of genes (323 with 2-fold differential expression, P < 0.01) that were uniquely regulated when endothelial cells and fibroblasts were cultured together. The manner in which we performed the array did not immediately tell us what cell type the genes were being regulated in, but in subsequent analysis it became apparent that many more genes were modulated in fibroblasts than in endothelial cells. The reason for this is not clear; however, we speculate that the endothelial cells exist in a more differentiated or mature state, while the fibroblasts are, as we intended, immature and susceptible to the influences of their cocultured neighbors. We have performed additional studies with endothelial cells cocultured with smooth muscle cells and observed that many genes modulated in fibroblasts were similarly regulated in smooth muscle cells (Supplemental Fig. S2). Moreover, human microvascular endothelial cells also regulated genes in fibroblasts (Supplemental Fig. S2). Thus possibly mural cells are more susceptible to genomic alterations, whereas endothelial cell-specific changes primarily occur through protein modifications or stability, which we would not have detected in this screen. Nevertheless, we cannot confirm this without further investigations using endothelial cells from different sources.

Although the large number of differentially expressed genes was intriguing, we wanted to understand the global changes that were occurring through these heterotypic interactions. By using the PANTHER classification system we were able to identify overrepresented pathways from this data set. The angiogenesis pathway was one class that we could have predicted. Within this group, a number of secreted factors and receptors were increased, possibly as a means to enhance communication between these cells. Indeed, PDGFRβ expression was augmented, and it plays a key role in mural cell recruitment. Other proangiogenic factors, including WNT5A and SPHK1, were also induced in fibroblasts. Given that fibroblasts can dramatically enhance vessel formation, it is not surprising that certain proangiogenic factors are increased. What makes these data compelling is that endothelial cells appear to enhance their own vessel assembly by signaling to fibroblasts that in turn secrete these proangiogenic factors. The purpose of this is uncertain; however, it is reasonable to speculate that endothelial cells may be reluctant to undergo morphogenesis in areas where mural cells are not available to produce a functional vessel. Once mural cells are present, the endothelial cells more readily form vessels via a complex system of cross talk and positive feedback.

Genes from the integrin pathway were also present in overabundance. Numerous collagen genes exhibited an increase in expression as well as integrin subunits α1 and α3. Within the vasculature, an elaborate basement membrane is created between the two cell types that is important for the integrity of the vessel wall and communication of the cells (27, 40). The induction of these genes by cell-cell interactions indicates that these cells are anticipating the need for these extracellular matrix factors. Through their unique affiliation they are able to produce the proper extracellular matrix milieu that is critical for their continued communication and function. Our data indicate that neither cell type is able to achieve this on its own. In addition, a larger than expected number of blood coagulation factors were also differentially regulated in cocultured cells, signifying again that the association of these two cell types is a trigger for the production of molecules needed later, in this case to facilitate blood movement throughout the vessels. Thus our data strongly support the notion that their interaction not only promotes the production of factors needed to build a complete blood vessel but also causes an upsurge in proteins, which will be needed for the proper function of the vasculature as a whole.

Utilization of Whole Genome rVISTA allowed us to scan the upstream promoter regions of array genes to look for overrepresented binding elements. A compelling finding was that genes upregulated under coculture conditions had an abundance of CBF1 binding elements. In accordance with this, we observed that NOTCH3 was increased ninefold in fibroblasts, suggesting that it may be a predominant regulator in these cells. In fact, utilization of the Notch inhibitor DAPT prevented the endothelium-induced increase of several fibroblast-expressed genes within the angiogenesis and integrin pathways. Furthermore, NOTCH3 knockdown also blocked the modulation of these genes. Thus these data show the importance of Notch signaling in the interaction of these two cell types and reveal that under these circumstances Notch signaling appears to be one-directional, with endothelial cells sending a signal that is received by fibroblasts. In fact, we recently have characterized the regulation of NOTCH3 by endothelial cells and have evidence that NOTCH3 signaling acts through an autoregulatory loop that requires endothelium-expressed JAGGED1 (unpublished observation).

Together, these data show that coculturing of endothelial cells and fibroblasts results in dramatic changes in gene expression that likely facilitate the proper formation and function of blood vessels. Furthermore, our findings indicate that Notch signaling is a critical mediator of endothelial cell/fibroblast-dependent transcription and directly show the requirement of this pathway for the expression of several endothelium-induced genes.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-076428 to B. Lilly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hua Liu for technical advice and critical reading of the manuscript.

Address for reprint requests and other correspondence: B. Lilly, Vascular Biology Center and Dept. of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical College of Georgia, 1459 Laney Walker Blvd., Augusta, Georgia 30912 (e-mail: blilly@mcg.edu).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev 22: 1276–1312, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circ Res 97: 512–523, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray SJ Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 678–689, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmeliet P Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 438: 932–936, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chand HS, Foster DC, Kisiel W. Structure, function and biology of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2. Thromb Haemost 94: 1122–1130, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho RJ, Campbell MJ. Transcription, genomes, function. Trends Genet 16: 409–415, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darland DC, D'Amore PA. Cell-cell interactions in vascular development. Curr Top Dev Biol 52: 107–149, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darland DC, Massingham LJ, Smith SR, Piek E, Saint-Geniez M, D'Amore PA. Pericyte production of cell-associated VEGF is differentiation-dependent and is associated with endothelial survival. Dev Biol 264: 275–288, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daubie V, Pochet R, Houard S, Philippart P. Tissue factor: a mini-review. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 1: 161–169, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis GE, Senger DR. Endothelial extracellular matrix: biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ Res 97: 1093–1107, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domenga V, Fardoux P, Lacombe P, Monet M, Maciazek J, Krebs LT, Klonjkowski B, Berrou E, Mericskay M, Li Z, Tournier-Lasserve E, Gridley T, Joutel A. Notch3 is required for arterial identity and maturation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Genes Dev 18: 2730–2735, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dormond O, Ruegg C. Regulation of endothelial cell integrin function and angiogenesis by COX-2, cAMP and protein kinase A. Thromb Haemost 90: 577–585, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan JB, Gunderson KL, Bibikova M, Yeakley JM, Chen J, Wickham Garcia E, Lebruska LL, Laurent M, Shen R, Barker D. Illumina universal bead arrays. Methods Enzymol 410: 57–73, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan JB, Yeakley JM, Bibikova M, Chudin E, Wickham E, Chen J, Doucet D, Rigault P, Zhang B, Shen R, McBride C, Li HR, Fu XD, Oliphant A, Barker DL, Chee MS. A versatile assay for high-throughput gene expression profiling on universal array matrices. Genome Res 14: 878–885, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer A, Gessler M. Delta-Notch—and then? Protein interactions and proposed modes of repression by Hes and Hey bHLH factors. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 4583–4596, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res 32: W273–W279, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geling A, Steiner H, Willem M, Bally-Cuif L, Haass C. A gamma-secretase inhibitor blocks Notch signaling in vivo and causes a severe neurogenic phenotype in zebrafish. EMBO Rep 3: 688–694, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodwin AM, Kitajewski J, D'Amore PA. Wnt1 and Wnt5a affect endothelial proliferation and capillary length; Wnt2 does not. Growth Factors 25: 25–32, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gridley T Notch signaling in vascular development and physiology. Development 134: 2709–2718, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedges JC, Dechert MA, Yamboliev IA, Martin JL, Hickey E, Weber LA, Gerthoffer WT. A role for p38MAPK/HSP27 pathway in smooth muscle cell migration. J Biol Chem 274: 24211–24219, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.High FA, Lu MM, Pear WS, Loomes KM, Kaestner KH, Epstein JA. Endothelial expression of the Notch ligand Jagged1 is required for vascular smooth muscle development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 1955–1959, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hinz B Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J Invest Dermatol 127: 526–537, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho IC, Pai SY. GATA-3—not just for Th2 cells anymore. Cell Mol Immunol 4: 15–29, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes CC Endothelial-stromal interactions in angiogenesis. Curr Opin Hematol 15: 204–209, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain RK Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat Med 9: 685–693, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin S, Hansson EM, Tikka S, Lanner F, Sahlgren C, Farnebo F, Baumann M, Kalimo H, Lendahl U. Notch signaling regulates platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 102: 1483–1491, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelleher CM, McLean SE, Mecham RP. Vascular extracellular matrix and aortic development. Curr Top Dev Biol 62: 153–188, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunz-Schughart LA, Schroeder JA, Wondrak M, van Rey F, Lehle K, Hofstaedter F, Wheatley DN. Potential of fibroblasts to regulate the formation of three-dimensional vessel-like structures from endothelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C1385–C1398, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai EC Keeping a good pathway down: transcriptional repression of Notch pathway target genes by CSL proteins. EMBO Rep 3: 840–845, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legate KR, Montanez E, Kudlacek O, Fassler R. ILK, PINCH and parvin: the tIPP of integrin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 20–31, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Fredriksson L, Li X, Eriksson U. PDGF-D is a potent transforming and angiogenic growth factor. Oncogene 22: 1501–1510, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Limaye V The role of sphingosine kinase and sphingosine-1-phosphate in the regulation of endothelial cell biology. Endothelium 15: 101–112, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, Chen B, Lilly B. Fibroblasts potentiate blood vessel formation partially through secreted factor TIMP-1. Angiogenesis 11: 223–234, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mi H, Guo N, Kejariwal A, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 6: protein sequence and function evolution data with expanded representation of biological pathways. Nucleic Acids Res 35: D247–D252, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montesano R, Pepper MS, Orci L. Paracrine induction of angiogenesis in vitro by Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. J Cell Sci 105: 1013–1024, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosesson MW Fibrinogen and fibrin structure and functions. J Thromb Haemost 3: 1894–1904, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev 84: 767–801, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozerdem U, Stallcup WB. Early contribution of pericytes to angiogenic sprouting and tube formation. Angiogenesis 6: 241–249, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parsons-Wingerter P, Elliott KE, Clark JI, Farr AG. Fibroblast growth factor-2 selectively stimulates angiogenesis of small vessels in arterial tree. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 1250–1256, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paulsson M Basement membrane proteins: structure, assembly, and cellular interactions. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 27: 93–127, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roth GJ, Yagi M, Bastian LS. The platelet glycoprotein Ib-V-IX system: regulation of gene expression. Stem Cells 14, Suppl 1: 188–193, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rousseau S, Dolado I, Beardmore V, Shpiro N, Marquez R, Nebreda AR, Arthur JS, Case LM, Tessier-Lavigne M, Gaestel M, Cuenda A, Cohen P. CXCL12 and C5a trigger cell migration via a PAK1/2-p38alpha MAPK-MAPKAP-K2-HSP27 pathway. Cell Signal 18: 1897–1905, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sainson RC, Harris AL. Regulation of angiogenesis by homotypic and heterotypic notch signalling in endothelial cells and pericytes: from basic research to potential therapies. Angiogenesis 11: 41–51, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saunders WB, Bohnsack BL, Faske JB, Anthis NJ, Bayless KJ, Hirschi KK, Davis GE. Coregulation of vascular tube stabilization by endothelial cell TIMP-2 and pericyte TIMP-3. J Cell Biol 175: 179–191, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Segal SS Regulation of blood flow in the microcirculation. Microcirculation 12: 33–45, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Serini G, Valdembri D, Bussolino F. Integrins and angiogenesis: a sticky business. Exp Cell Res 312: 651–658, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stella MC, Comoglio PM. HGF: a multifunctional growth factor controlling cell scattering. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 31: 1357–1362, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sutmuller M, Bruijn JA, de Heer E. Collagen types VIII and X, two non-fibrillar, short-chain collagens. Structure homologies, functions and involvement in pathology. Histol Histopathol 12: 557–566, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takada Y, Ye X, Simon S. The integrins. Genome Biol 8: 215, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Umetani M, Mataki C, Minegishi N, Yamamoto M, Hamakubo T, Kodama T. Function of GATA transcription factors in induction of endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21: 917–922, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villaschi S, Nicosia RF. Paracrine interactions between fibroblasts and endothelial cells in a serum-free coculture model. Modulation of angiogenesis and collagen gel contraction. Lab Invest 71: 291–299, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang T, Baron M, Trump D. An overview of Notch3 function in vascular smooth muscle cells. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 96: 499–509, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Kong D, Banerjee S, Li Y, Adsay NV, Abbruzzese J, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of platelet-derived growth factor-D inhibits cell growth and angiogenesis through inactivation of Notch-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB signaling. Cancer Res 67: 11377–11385, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wendum D, Comperat E, Boelle PY, Parc R, Masliah J, Trugnan G, Flejou JF. Cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 alpha overexpression in stromal cells is correlated with angiogenesis in human colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol 18: 212–220, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zambon AC, Zhang L, Minovitsky S, Kanter JR, Prabhakar S, Salomonis N, Vranizan K, Dubchak I, Conklin BR, Insel PA. Gene expression patterns define key transcriptional events in cell-cycle regulation by cAMP and protein kinase A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 8561–8566, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zerlin M, Julius MA, Kitajewski J. Wnt/Frizzled signaling in angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 11: 63–69, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou M, Ouyang W. The function role of GATA-3 in Th1 and Th2 differentiation. Immunol Res 28: 25–37, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.