Abstract

There are widespread chemosensitive areas in the brain with varying effects on breathing. In the awake goat, microdialyzing (MD) 50% CO2 at multiple sites within the medullary raphe increases pulmonary ventilation (V̇i), blood pressure, heart rate, and metabolic rate (V̇o2) (11), while MD in the rostral and caudal cerebellar fastigial nucleus has a stimulating and depressant effect, respectively, on these variables (17). In the anesthetized cat, the pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötzC), a hypothesized respiratory rhythm generator, increases phrenic nerve activity after an acetazolamide-induced acidosis (31, 32). To gain insight into the effects of focal acidosis (FA) within the preBötzC during physiological conditions, we tested the hypothesis that FA in the preBötzC during wakefulness would stimulate breathing, by increasing respiratory frequency (f). Microtubules were bilaterally implanted into the preBötzC of 10 goats. Unilateral MD of mock cerebral spinal fluid equilibrated with 6.4% CO2 did not affect V̇i, tidal volume (Vt), or f. Unilateral MD of 25 and 50% CO2 significantly increased V̇i and f by 10% (P < 0.05, n = 10, 17 trials), but Vt was unaffected. Bilateral MD of 6.4, 25, or 50% CO2 did not significantly affect V̇i, Vt, or f (P > 0.05, n = 6, 6 trials). MD of 80% CO2 caused a 180% increase in f and severe disruptions in airflow (n = 2). MD of any level of CO2 did not result in any significant changes in mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate, or V̇o2. Thus the data suggest that the preBötzC area is chemosensitive, but the responses to FA at this site are unique compared with other chemosensitive sites.

Keywords: breathing, chemosensitivity

central respiratory co2/h+ chemoreception has been traditionally attributed to sites at or near the ventrolateral medullary surface (16, 24, 27). However, studies over the last 15–20 yr indicate that the ventrolateral medullary surface is not the sole CO2/H+-sensitive area (1–3, 5, 15, 17, 21, 24, 31, 32). Electrophysiological recordings of in vitro preparations have shown that neurons in the retrotrapezoid nucleus, nucleus of the solitary tract, the medullary raphe nucleus (MRN), locus coeruleus, and the pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötzC) increase discharge frequency when the pH in the bathing solution is reduced (3, 5, 8, 14, 22, 24). Studies in anesthetized preparations that either created a focal acidosis (FA) or assessed the effects of lesions on the hypercapnic ventilatory response also support the concept of widespread chemosensitivity in the medulla, pons, and cerebellum (11, 18, 32, 33, 35, 36, 37).

While the in vivo data, under physiological conditions, suggest that chemoreceptors at multiple sites influence breathing, the observed ventilatory effects are not uniform, and the hyperpnea is small, with FA at a single site compared with the hyperpnea observed during a global brain acidosis. In the awake goat, microdialyzing (MD) hypercapnic mock cerebral spinal fluid (mCSF), which decreases extracellular fluid (ECF) pH by 0.018 in one area of the MRN, increases pulmonary ventilation (V̇i) by 12% (10), while a comparable global brain acidosis resulting from 2.5% inspired CO2 increases breathing by 100% (10). However, when a FA is produced at two or three MRN sites, V̇i increases by 30%, due mostly to increases in tidal volume (Vt) (11). This relatively small response to FA might, in part, be due to alkalosis at other chemosensitive sites during FA at one or a few sites. Accordingly, it is conceivable that the hyperpnea during global brain acidosis reflects the cumulative or additive effect of chemoreception at multiple sites, rather than a result of activation of chemoreceptors at any single site.

The preBötzC, a medullary area hypothesized to be the dominant inspiratory rhythm generator (4, 19, 23, 29, 30, 37), may also contain neurons that exhibit CO2/H+ sensitivity. Notably, an acetazolamide-induced acidosis in the preBötzC of anesthetized, vagotomized, paralyzed, and mechanically ventilated cats increases the frequency and amplitude of phrenic nerve activity (31, 32). However, the effects on breathing of increasing different levels of CO2 focally at the preBötzC of a conscious animal are unknown. Thus one objective of the present study was to establish whether FA in the preBötzC increases breathing in the conscious state. Since V̇i was increased in a dose-dependent manner during FA in the MRN (10, 11), but not in the cerebellar fastigial nucleus (CFN) (17), a second objective was to determine whether there would be a dose-dependent stimulation of breathing as a progressively more severe acidosis was created, first unilaterally and then bilaterally in the preBötzC. Furthermore, since ECF pH in the MRN decreases less than plasma pH during whole body hypercapnia (10), a third objective was to determine whether ECF pH in the preBötzC would also change less than plasma pH during whole body hypercapnia. Also, since, in the MRN (10, 11) and CFN (17), the effects on breathing were solely due to a change in Vt, a fourth objective was to determine if FA in the preBötzC would stimulate breathing through changes in Vt or respiratory frequency (f). Finally, since FA in the MRN (10, 11) and CFN (17) in the awake goat also had effects on metabolic rate (V̇o2) and heart rate (HR), a fifth objective was to determine whether FA in the preBötzC would alter V̇o2 and HR.

We hypothesized that (just as in the MRN) a MD-induced FA in the preBötC of the awake goat will increase V̇i in a dose-dependent manner, including bilateral responses greater than unilateral responses. Also, given the respiratory rhythm-generating role of the preBötzC, and data from anesthetized cats showing that a FA in this nucleus increases f (12, 31, 32), we hypothesized that FA in this nucleus in awake goats would also increase f, and that the FA would not stimulate V̇o2 and HR. Finally, we hypothesized that ECF pH in the preBötzC will (as in the MRN) decrease less than plasma pH during whole body hypercapnia.

METHODS

Physiological data were obtained on 10 adult female goats, weighing 43.3 ± 2.4 kg. Four additional goats were utilized for histological purposes only (44.1 ± 3.1 kg). Goats were housed and studied in an environmental chamber with a fixed ambient temperature and photoperiod. All goats were allowed free access to hay and water, except for periods of study. The goats were trained to stand comfortably in a stanchion during periods of study. All aspects of the study were reviewed and approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Animal Care Committee before the studies were initiated.

Surgical procedures.

Before all surgery, goats were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine and xylazine (15 and 1.25 mg/kg, respectively), intubated, and mechanically ventilated with 1.5% halothane in 100% O2. All surgeries were performed under sterile conditions. Each goat underwent an initial instrumentation surgery in which a 5-cm segment of each carotid artery was dissected from the vagus nerve and elevated subcutaneously for eventual insertion of a catheter. Electromyogram electrodes were implanted into the diaphragm to monitor muscle activity. Ceftifur sodium (Naxcel) (8 mg/kg) was administered (intramuscularly, every day) for 1 wk postoperatively to minimize infection.

After at least 2 wk of recovery, goats then underwent another surgery for the purpose of unilaterally or bilaterally implanting 70-mm-long (1.27 mm outer diameter, 0.84 mm inner diameter) stainless steel microtubules (MTs) into the preBötzC. An occipital craniotomy was created, and the dura mater was excised to expose the posterior cerebellum and the dorsal aspect of the medulla for visualization of obex. Using previously delineated coordinates of the preBötzC in goats (36, 37), the MTs were implanted 2.5–3.5 mm rostral to obex, 4–5 mm lateral to the midline, and extending 5–7 mm from the dorsal surface of the medulla.

Experienced laboratory personnel continuously monitored the goat at least 24 h after brain surgery, or until the goat reached stable conditions. Buprenorphrine hydrochloride (Buprenex) (0.005 mg/kg) was administered for pain, as needed. Each goat was also placed on a regimen of medication to minimize infection (chloremphenicol, 20 mg/kg iv, 3× per day for 3 days) and swelling (dexamethansome iv, 3× per day for 7 days, starting with 0.4 mg/kg and decreasing to 0.05 mg/kg). Every day thereafter until death, the goat was medicated with centiofur sodium and gentamyacin (Gentamax 100) (6 mg/kg im, every day).

Physiological variables.

Studies commenced 2 or more weeks after MT implantation. Inspiratory flow was measured with a pneumotach by attaching a breathing valve to a custom-fitted mask secured to the goat's muzzle. Expired air was collected in a spirometer, allowing for determination of expired volume and concentration of CO2 and O2 to calculate metabolic rate. V̇i, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), and HR were continuously recorded, both on a Grass recorder and Codas software. Rectal temperature was monitored at regular intervals.

Experimental procedures and protocol.

The MD probe (CMA Microdialysis, Solna, Sweden) that was inserted into the MT had a 70-mm shaft length and 2-mm membrane length (0.5-mm membrane diameter with a 20-kDa molecular mass cutoff) so that the 2-mm membrane penetrated the brain tissue. A FA was created by reverse MD mCSF (124 mM NaCl, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 2.0 mM CaCl2, and 26 mM NaHCO3 in sterile distilled H2O), equilibrated with either 6.4, 25, 50, or 80% CO2 that had been mixed in a tonometer heated to 39°C. The pH of the mCSF was measured before beginning dialysis and was 7.32, 6.85, 6.55, and 6.38, respectively, for the four levels of CO2. These levels of acidosis in mCSF are needed to achieve an acidosis in ECF comparable to that created by inhaling 3, 5, or 7% CO2 gas mixtures (10). Specifically, our laboratory has previously shown that MD in the MRN of awake goats with 25, 50, and 80% CO2 decreases ECF pH by 0.005, 0.01, and 0.018, respectively, when the pH electrode is 215 μM from the dialysis probe (10).1 We have also established that ECF pH does not change 1.4 mm from the dialysis probe, indicating that the acidosis is focal (10).

A FA study consisted of MD of three or four different levels of CO2 equilibrated in mCSF in a single day. The study protocol entailed a 15-min control period (no MD), followed by a 45-min period of dialyzing CO2-equilibrated mCSF into the preBötzC, and was concluded with a 15-min recovery period. Arterial blood was sampled over the last 5 min of each control, dialysis, and recovery periods. This protocol was repeated three or four times on 3 different days, with each day starting with dialysis of mCSF equilibrated with 6.4% CO2, and then dialysis of mCSF equilibrated with, in order, 25% and 50%, and in two goats 80% CO2. On the first day, the FA studies were unilateral on the left side, then on a second day, the studies were unilateral on the right side, and finally, 2–3 days later, dialysis was completed bilaterally. Ten animals had two unilateral studies, for a total of 20 trials (n = 10, 17 trials), and six animals had six bilateral studies (n = 6, 6 trials).

In the initial two goats, unilateral or bilateral FA of 80% CO2 in the preBötzC elicited a severe tachypnea and disruptions in the airflow pattern that persisted for several days thereafter. Thus FA of 80% CO2 was not studied in subsequent goats. Moreover, because we were concerned that FA, or the dialysis process per se, may cause damage to preBötzC neurons, in all subsequent goats, resting blood gases and sensitivity to elevated inspired CO2 (creating global brain acidosis) were assessed on days before and after FA. After a 15-min room air control period, a global acidosis was created by sequentially increasing inspired CO2 to 3, 5, and 7% at 5-min intervals and was then followed by a 15-min room air recovery period. Arterial blood samples were collected over the last 2 min of the control period and each level of CO2. CO2 sensitivity [ΔV̇i/Δarterial Pco2 (PaCO2)] was assessed to enable comparison between global and FA and to ensure that the goats studied had a CO2 sensitivity within the normal range, ∼1.8–2.2 l·min−1·mmHg−1.

ECF pH measurements in the preBötzC were also obtained during global acidosis (n = 5) for the purpose of comparing previous pH measurements of the MRN of awake goats (11). A custom-made metal-metal oxide pH electrode (70-mm shaft, 2-mm length-sensing tip, 0.5-mm inner diameter) (World Precision Instruments) was inserted unilaterally into a MT. A reference electrode was adhered to a shaven area of skin. Both were then connected to a pH meter (Corning 315 pH/Ion), and millivolt (pH) readings were recorded every minute. After pH was measured in vivo, the electrode was calibrated in a heated water bath (39°C) using three different buffer solutions (pH = 4, 7, and 10), and a linear calibration curve was calculated in millivolts/pH unit. This curve was then used to compute the change in ECF pH during the period when inspired CO2 was administered.

To determine whether the in vitro calibration accurately described pH in vivo, two holes were bored into the top of a 100-μl Eppendorf tube: an Ag-AgCl reference electrode (WPI) was inserted into one hole, and a pH electrode was inserted into a second hole. Another two holes were bored into the Eppendorf tube to allow for the flow of mCSF into and out of the tube. The tube was then filled with mCSF equilibrated with 6.4% CO2. mCSF equilibrated with either 6.4 or 50% CO2 was first analyzed for pH using a blood-gas analyzer and then flowed through the Eppendorf tube (50 μl/min) for 30 min. The pH in the tube was recorded at 1-min intervals. At the completion of the in vitro study, the pH electrode was calibrated as described above. The change in pH of mCSF between 6.4 and 50% CO2 was −0.810, as determined by the blood-gas analyzer, and −0.767 as determined by the in vitro calibrated pH electrode. This close agreement indicates that an accurate estimate of the changes in ECF pH was obtained in vivo.

Glutamate receptor agonist injections.

A glutamate receptor agonist applied to the preBötzC elicits a classic physiological response, manifested as an increase in f (19, 30, 37). Weeks after the completion of the FA studies, the neurotoxin ibotenic acid (IA), an irreversible glutamate receptor agonist, was injected into the preBötzC of the present group of goats to examine the plasticity of respiratory rhythmogenesis. The experimental design consisted of injecting a series of incremental, sequential volumes of IA (50 mM) that started with 500 nl and increased to 10 μl. Each injection was separated by 1 wk. After a 15-min eupneic control period, a unilateral injection of IA was made into the preBötzC through the MT. Physiological variables were monitored for 1 h, and then an identical injection was made into the contralateral MT, except that, for the 10-μl volume, the contralateral injection was made 1 wk later.

Histological studies.

After completion of all experimental protocols, the animals were euthanized (Beuthanasia), and the brain was perfused with phosphate-buffered saline solution and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The medulla was then excised and placed in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24–48 h and then placed in a 30% sucrose solution. Subsequently, the medulla was frozen and serial sectioned (25 μm) in a transverse plane and adhered to chrome alum-coated slides. The tissue was Nissl stained or stained with hematoxylin and eosin, coverslipped, and examined microscopically. The MT implantation site was identified by visualization of an area of absent or disrupted tissue and was defined as being the tip of the ventral-most aspect and middle of the MT-induced tissue disruption.

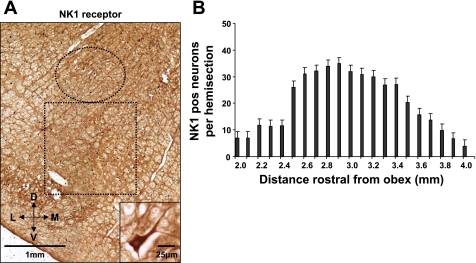

Four additional (control) goats were utilized solely to obtain histological data on the medulla of goats. These goats were killed, and the medulla was harvested and processed as above, except, in addition to the hematoxylin and eosin and Nissl staining, a series of sections were used for neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R) immunoreactivity. An anti-NK1R primary antibody was complexed with biotinylated anti-mouse secondary antibody. After the antibody antigen complex was incubated, it was localized by avidin (Vector ABC Elite) and developed with diaminobenzoate. Total and NK1R immunoreactive neurons were counted every 100 μm from 2 to 4.6 mm rostral to obex in a 1.5- by 1.5-mm area just ventral to nucleus ambiguous (NA) (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1)-expressing neurons ventral to nucleus ambiguus (NA) identify the pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötzC) in adult goats. A: a portion of a transverse section 2.9 mm rostral to obex from the medulla of a control goat. The section was processed for (NK1) immunoreactivity. The circle delineates NA, as identified by the large motoneurons. The box delineates the presumed preBötzC with a large number of NK1-immunoreactive neurons. The inset in A is a single neuron from the preBötzC. B: the high density of neurons from ∼2.5–3.5 mm rostral to obex, which we presume is the preBötzC. D, dorsal; V, ventral; L, lateral; M, medial.

Data analysis.

V̇i (l/min), f (breaths/min), Vt (liters), V̇o2 (l/min), MABP (mmHg), and HR (beats/min) of each goat were averaged into 5-min bins. All bins were divided by the 15-min control mean for normalization (percentage of control). Arterial blood was sampled in duplicate, and arterial Po2 (Torr), PaCO2 (Torr), and pH (pH units) (model 278, Bayer Diagnostics) were averaged. The mean data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA with repeated measures, where the threshold for significance was set at P ≤ 0.05 and expressed as SE about the mean. Individual significant differences were examined with the Bonferroni post hoc test and compared against the 15-min control.

RESULTS

Histology and placement of MTs.

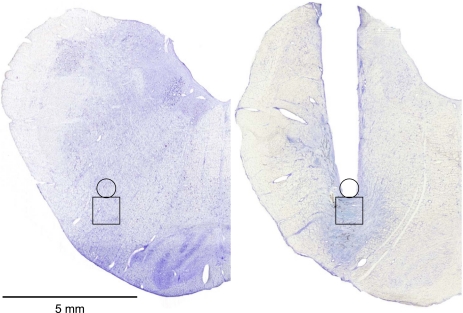

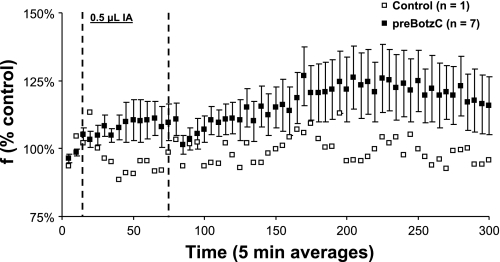

Figure 1A is from a transverse section 2.9 mm rostral to obex from a control goat's medulla. This figure illustrates a high density of NK1R-expressing neurons ventral to NA. Figure 1B agrees with our laboratory's previously published finding (36) that, ventral to NA, between 2.5 and 3.5 mm rostral to obex and 4.0 to 5.0 mm lateral to the midline, there is an unique high density of NK1R-expressing neurons, which we presume is the preBötzC. Histology completed after the goats were killed indicated that the MTs were placed between 2.5 and 3.5 mm rostral to obex, 4.0 and 5.0 mm lateral to the midline, and extending 5.0–7.0 mm from the dorsal surface, such that they were within, or ended just dorsal to, the preBötzC (Fig. 2). This location of all of the MTs was consistent with the previously reported stereotaxic definition of the preBötzC in goats (36). Physiological confirmation of correct MT placement in the goats studied herein is provided by the characteristic tachypnea (Fig. 3) in the goats when IA was injected into the preBötzC weeks after the completion of the FA studies. This tachypneic hyperpnea was dose dependent, increasing from 25 to 250% above control as the volume of IA injected increased from 0.5 to 5 μl (12).

Fig. 2.

The microtubules were placed just ventral to the dorsal edge of NA into the preBötzC. Left: Nissl stain of a control goat medulla 3 mm rostral to obex, and the box outlines the presumed preBötzC. Right: Nissl stain on a goat with bilaterally implanted microtubules. The tract of the microtubule is indicated by the area devoid of tissue. The extensive tissue disruption ventral to the tip of the microtubule is due primarily to the neurotoxin injected over weeks after completion of the focal acidosis (FA) studies reported herein. This conclusion is based on our laboratory's previous finding (see Figs. 4 and 5 in Ref. 9) that, in goats in which we followed the same design as in the present study (FA followed by injections of a neurotoxin), the tissue damage ventral to the microtubule implanted into the medullary raphe nucleus (MRN) was five times greater than in goats that only underwent FA.

Fig. 3.

The glutamate receptor agonist, ibotenic acid (IA), elicited a tachypneic hyperpnea when injected into the preBötzC of awake goats. When 0.5 μl IA was injected bilaterally into the preBötzC, there was a significant increase in respiratory frequency (f) (P = 0.002, n = 7). Note that there was no increase in f when IA was injected in an area that was dorsal and lateral to the preBötzC (control). The time point of injection is indicated by the dashed lines.

Physiological responses post-FA.

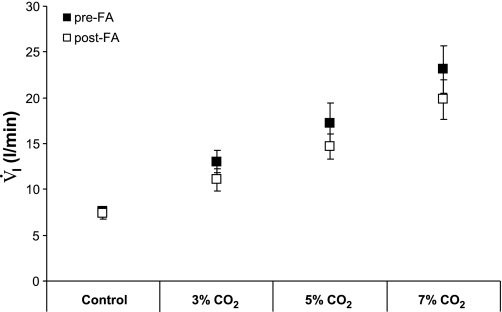

Eupneic breathing, resting PaCO2, and CO2 sensitivity (ΔV̇i/ΔPaCO2) were measured 5 days pre- and post-FA (n = 6, 12 trials). Five days post-FA, resting PaCO2 was significantly increased by 2.6 Torr (P < 0.005, Table 1), although still within normal limits (9–11, 17, 18, 36, 37). Total ventilation during eupneic breathing conditions did not differ between pre- and post-FA studies (P = 0.76), but, 5 days after FA, f was accentuated by 10.5% (P < 0.03) and Vt was decreased by 7.5% (P < 0.03). FA had no significant effect on CO2 sensitivity (P = 0.56) (Table 1) conventionally expressed as ΔV̇i/ΔPaCO2. Total ventilation during 3, 5, or 7% inspired CO2 (Fig. 4) also were not significantly (P = 0.06) different pre- vs. post-FA, but there was a trend of a lower value at each inspired CO2 fraction post-FA.

Table 1.

A focal acidosis within the pre-Bötzinger complex results in chronic respiratory effects

| Goat | V̇i, l/min |

f, breaths/min | Vt, liters | PaCO2, Torr | CO2 Sensitivity (ΔV̇i/ΔPaCO2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Average | 7.9±0.6 | 7.8±0.7 | 20.3±1.6 | 30.5±3.2* | 0.4±0.05 | 0.3±0.03* | 41.5±0.9 | 44.1±0.8* | 1.78±0.15 | 1.58±0.33 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6 animals and 12 trials. Within 5 days after focal acidosis (Post), respiratory frequency (f) and resting arterial Pco2 (PaCO2) were significantly increased, and tidal volume (Vt) was significantly decreased compared with the pre-focal acidosis (Pre) studies (

P < 0.05). V̇i, pulmonary ventilation; Δ, change.

Fig. 4.

Ventilation (V̇i) during 3, 5, and 7% CO2 did not change significantly 5 days after FA compared with preacidosis control (P > 0.05, n = 6, 12 trials).

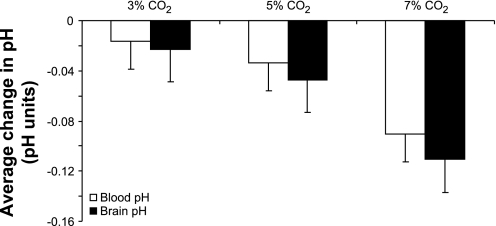

Plasma and preBötzC ECF pH measurements during whole body hypercapnia.

There was a progressive decrease in both blood and preBötzC ECF fluid pH during 3, 5, and 7% inspired CO2 (Fig. 5). There was a trend that the change in brain pH decreased more than blood pH at each level of hypercapnia; however, these differences were not significant (P > 0.05, n = 5, 12 trials).

Fig. 5.

There were progressive decreases in plasma and preBötzC extracellular fluid (ECF) during systemic acidosis. There were no significant differences in the magnitude of pH change between the blood or preBötzC ECF (P > 0.05, n = 5, 12 trials).

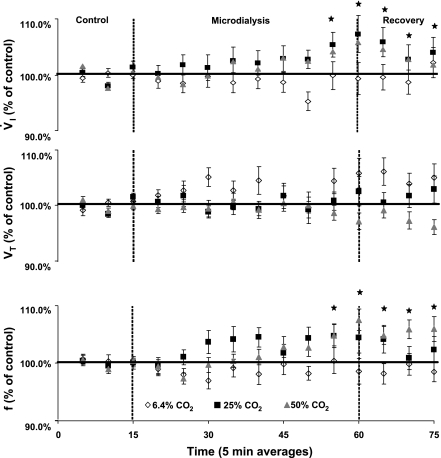

Physiological response to MD-FA in the preBötzC area.

Unilateral MD of mCSF equilibrated with 6.4% CO2 (control) had no significant effect on V̇i, f, or Vt (Fig. 6). However, MD of both 25 and 50% CO2 both significantly increased V̇i (P < 0.03 and 0.01, respectively) as a function of a significant increase in f (P < 0.01, and 0.04, respectively) maximally by 10%, most often during the last 10 min of the dialysis period (n = 10, 17 trials). V̇i and f often remained elevated during the recovery period, although both began to return to baseline in the recovery period. This temporal pattern during the recovery has been observed in our laboratory's previous studies on FA in the MRN (10, 11) and CFN (17), and we presume this pattern reflects the gradual restoration of brain pH to normal. Vt was unaffected by FA (P > 0.05, Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

A microdialysis (MD)-induced FA created unilaterally in the preBötzC with 25 and 50% CO2 equilibrated mock cerebral spinal fluid (mCSF) (n = 10, 17 trials), significantly increasing V̇i and f by 10% (P < 0.05). V̇i, tidal volume (Vt), and f were averaged into 5-min interval and expressed as a percentage of control. MD of normal, 6.4% CO2 did not affect V̇i, Vt, or f. MD of 25 and 50% CO2 significantly increased V̇i or f, but not Vt.

Bilateral MD of mCSF equilibrated with 6.4, 25, or 50% CO2 did not have any consistent and significant effect on V̇i, f, or Vt (P > 0.05, n = 6, 6 trials, Fig. 7). However, as shown in Fig. 8, in some goats bilateral MD at some levels of FA did stimulate breathing. For the group of goats, there were nonsignificant (P > 0.05) 4–8% increases in V̇i and f, but not Vt, with MD of 6.4% CO2 during the dialysis period, as well as nonsignificant 4–6% increases in V̇i and f with 50% CO2, mostly during the recovery period (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

A MD-induced FA created bilaterally in the preBötzC with 50% CO2 equilibrated mCSF (P > 0.05 n = 6, 6 trials) did not significantly increase V̇i, f, or Vt. V̇i, Vt, and f were averaged into 5-min intervals and expressed as a percentage of control. MD of normal, 6.4% CO2 or 25% CO2 did not affect V̇i, Vt, or f. MD of 50% CO2 nonsignificantly increased V̇i and f.

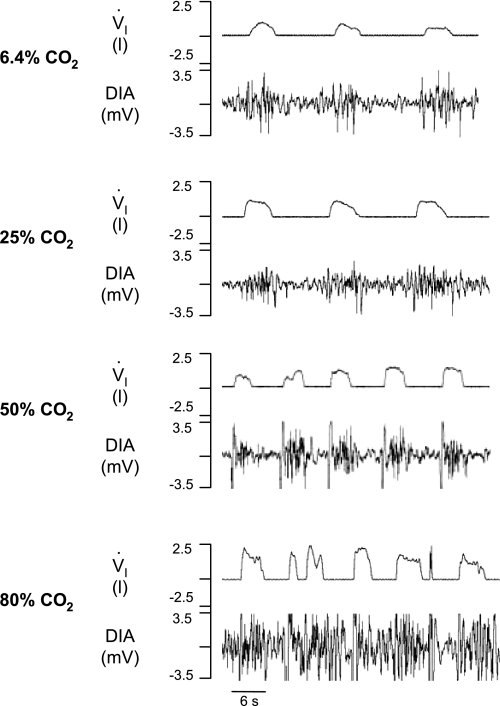

Fig. 8.

Representation of breathing pattern after bilateral dialysis of 6.4, 25, 50, and 80% CO2 in the preBötzC. First panel: control breathing; note regular V̇i and phasic diaphragm (DIA) activity. Second and third panels: breathing during 25 and 50% CO2, respectively. Fourth panel: the irregularities in V̇i and DIA activity during 80% CO2.

In one goat, a bilateral FA was created by dialyzing 80% CO2 (pH = 6.35). During dialysis, there was a prominent increase in V̇i to a level that was 180% above control (Fig. 8). Moreover, the characteristic regular inspiratory flow and diaphragm activity became very irregular (Fig. 8). For 4 days thereafter during control conditions, f continued to be 50–200% above normal, and a gasping pattern emerged. However, there were also periods of decreased V̇i, indicating possible upper airway constriction. After the fourth day, however, breathing and muscle activation patterns were normal.

In a second goat, a unilateral FA created with 80% CO2 increased f by 13%, although V̇i was relatively unchanged. However, during the entire dialysis periods, and for the subsequent days after MD, there were disruptions in the airflow pattern. Then 2 days later, almost immediately after the start of bilateral MD of 6.4% CO2, V̇i and f increased to levels 180% above control, and the disruptions in airflow pattern, as indicated by both fractionated breathing and prolonged apneas, were so severe that MD was stopped after 5 min. Based on the disruptions in the flow pattern in these two goats with dialysis of 80% CO2, unilateral and bilateral MD with 80% CO2 was discontinued in subsequent animals.

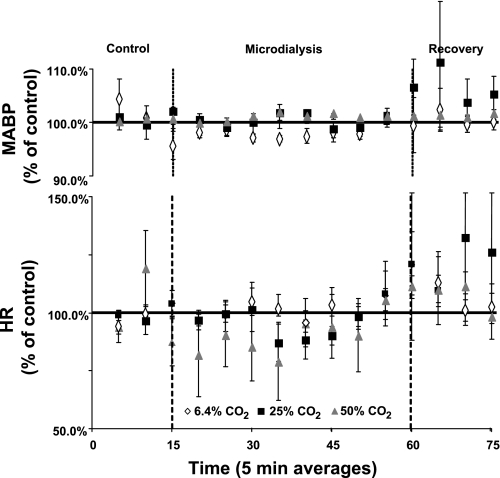

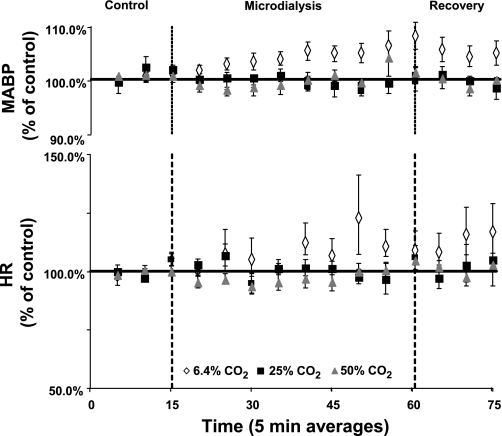

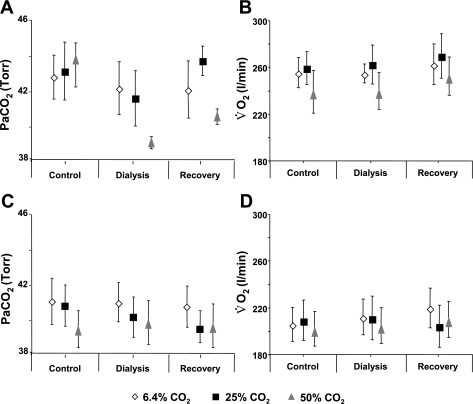

A unilateral or bilateral FA at any level did not significantly affect MABP, HR (Figs. 9 and 10), V̇o2, or PaCO2 (P > 0.05) (Fig. 11).

Fig. 9.

A MD-induced FA created unilaterally in the preBötzC with any level of CO2 equilibrated mCSF did not significantly affect mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) or heart rate (HR) (P > 0.05, n = 10, 17 trials). MABP and HR were averaged into 5-min intervals and expressed as a percentage of control.

Fig. 10.

A MD-induced FA created bilaterally in the preBötzC with any level of CO2 equilibrated mCSF did not significantly affect MABP or HR (P > 0.05, n = 6, 6 trials). MABP and HR were averaged into 5-min intervals and expressed as a percentage of control.

Fig. 11.

A MD-induced FA created unilaterally (A and B, n = 10, 17 trials) or bilaterally (C and D, n = 6) in the preBötzC did not significantly affect arterial Pco2 (PaCO2) or oxygen consumption (V̇o2) (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Major conclusions.

The present study shows that a FA in the preBötzC area of the awake goat does increase ventilation through effects on respiratory f but not Vt. However, the increase in breathing during FA is small compared with the increase during a global brain acidosis.

Functional and anatomical definition of the preBötzC.

Several studies have attempted to define the boundaries of the preBötzC. Studies in adult rats found a distinct increase in NK1R-positive neurons ventral to NA (6, 7, 34, 35). Subsequently, data from other studies suggested that a high density of somatostatin immunoreactive neurons ventral to NA accurately defined the boundaries of the preBötzC (34). To further explore “the necessary and sufficient boundaries for a functional preBötzC,” studies have recently been completed on neonatal rat medullary slices of different thicknesses (25, 26). The data indicate there is a core of rhythmogenic neurons ∼0.7 mm caudal to the facial nucleus essential for respiratory rhythmogenesis, with neurons caudal and rostral to the core that contribute to the eupneic and sigh rhythms, respectively. From these and other studies, the general consensus is that the exact boundary of the preBötzC, or boundary of the medullary neurons responsible for the eupneic respiratory rhythm, has not been established, and there is no consensus on anatomic markers that accurately define the preBötzC. However, it is generally accepted that the preBötzC includes an area ventral to NA that has a high density of NK1R- and somatostatin receptor-expressing neurons.

Previously reported data from our laboratory (36), together with data shown in Fig. 1 of this paper, establish that, in goats, there is a high density of neurokinin-1-positive neurons in an area that is just ventral to NA and medial to the spinal trigeminal nucleus, spanning a region that is 2.5–3.5 mm rostral from obex. Postmortem histology on the goats studied herein revealed that the MTs were placed within a range of 2.5–3.5 mm rostral from obex, just dorsal to the area of peak neurokinin-1-expressing neurons (Fig. 2). Since the dialysis probe was inserted 2.0 mm beyond the tip of the MT, we are confident that FA was created in the preBötzC.

Physiologically, the preBötzC can be defined by a distinct, unique tachypnic and dysrhythmic response to injection of a glutamate receptor agonist (19, 30, 37). Weeks after the completion of the FA studies, the glutamate agonist IA was injected into the preBötzC in incremental volumes over a period of 4 wk. The smallest 0.5-μl dose of IA elicited a significant tachypnea (Fig. 3), which was accentuated in a dose-dependent manner with 1 and 5 μl of IA. These data corroborate the histological findings that the MTs were correctly placed within the preBötzC. Since the MT was in the ventral portion of NA, the FA may also have occurred in a portion of NA. However, our laboratory has previously documented that, for at least dialysis within the MRN, MD, even up to 80% CO2, only creates an acidosis at a distance <1.4 mm from the dialysis probe (10). Thus we are confident that the acidosis created in this study was restricted to a small area within and surrounding the preBötzC area.

Physiological responses of an MD-FA in the preBötzC.

A FA created in the preBötzC elicits ventilatory responses that are uniquely different from the responses of a FA in the MRN (10, 11) or CFN (17) of awake goats. First, FA in the preBötzC increases breathing solely due to increases in f, and not Vt, whereas a FA in the MRN and CFN alters breathing through changes in Vt. The present data are consistent with the effects of carbonic anhydrase inhibition-induced FA in the preBötzC in anesthetized cats (31) and the effect of acidosis in the superfusate bathing a neonatal rat medullary slice containing the preBötzC (12). In both of these reduced preparations, acidosis increased phrenic burst frequency. Second, a FA in the preBötzC does not elicit nonrespiratory effects, whereas a FA in the MRN (10, 11) or CFN (17) results in significant changes in V̇o2, MABP, or HR. These first two unique effects seem consistent with the important role of the preBötzC in respiratory rhythm generation (4, 19, 23, 29, 30, 37). Third, bilateral FA with 25 and 50% CO2 in the preBötzC does not elicit any consistent or significant ventilatory response, whereas bilateral FA in the MRN elicits a greater response than a unilateral FA (10, 11). Fourth, as opposed to FA in the MRN, a FA in the preBötzC with 25 and then 50% CO2 does not elicit a significant dose-dependent increase in V̇i and f. However, in two of two goats, dialysis of 80% CO2 increased f more than dialysis of 25 and 50% CO2, which appears to suggest a dose-dependent response. It might be relevant though that, in these two goats, dialysis with 80% CO2 also caused dysrhythmic and disrupted breathing (Fig. 8) that persisted for days after dialysis. This type of response never occurred during FA in the MRN (10, 11) or the CFN (17), but these responses somewhat resemble previous findings of Solomon et al. (31) that FA in the preBötzC of anesthetized cats resulted in augmented phrenic bursts (fictive sighs) or doublet/premature phrenic bursts. In any event, it is clear that the responses to increasing levels of FA at the preBötzC differ from the responses to increasing levels of FA at the MRN and CFN. Finally, it is important to note that, days after completion of the FA studies, resting f and PaCO2 were slightly increased, and there was a trend toward reduced CO2 sensitivity compared with pre-FA studies. In our previous work of FA in the MRN and CFN, we never studied the chronic effects of FA on breathing.

We are unaware of any definite explanation for the differences in effects of FA in the preBötzC and the MRN or CFN. One potential explanation for the absence of a dose-dependent effect between 25 and 50% CO2 and/or absence of a bilateral FA effect as in the MRN is that FA may not affect the preBötzC chemosensitive neurons uniformly. This possibility is similar to the contrasting observations reported with acidifying different portions of the CFN in awake goats (17). Accordingly, FA with 25% CO2 may activate primarily chemosensitive neurons that stimulate breathing, while 50% CO2 may activate neurons that stimulate breathing and other neurons that depress breathing. Another possibility is that chemosensitive and/or rhythmogenic neurons in the preBötzC are less capable of tolerating the process of dialysis and/or FA than neurons in the MRN and CFN; thus bilateral dialysis or the extreme FA with 80% CO2 may have “injured” the neurons, resulting in the unusual findings. Finally, it is possible that absence of a hyperpnea with bilateral dialysis reflects deterioration of the rhythm generator rendered nonresponsive to CO2 because of previous exposure to FA. The small differences in breathing pre- vs. post-FA may reflect tissue damage/deterioration of the rhythm generator as a result of the FA or dialysis process per se. It is also possible that compression of the preBötzC neurons caused by implanting the MTs may have damaged the chemosensitive neurons and attenuated their response to the FA. In evaluating this potential effect, however, it is important to consider that compression and damage also occurred when MTs were implanted into the MRN and the CSF, and these differences between responses to FA at various sites cannot categorically be attributed to tissue damage. Also, despite any damage to the preBötzC neurons, there was a brisk, dose-dependent response to the IA injections, after completing the FA studies. Also important to consider is that, as explained in the Fig. 2 legend, the tissue damage shown in Fig. 2 is due primarily to the IA injections. Overall, the differences between the past and present studies seem to indicate that chemosensitive neurons in the preBötzC are inherently different from those in the MRN and CFN, or that the input of these chemoreceptors contributes differently than other chemoreceptors to the neuronal network controlling breathing.

In a previous study on awake adult goats, it was found that, when inspired CO2 was sequentially increased at 5-min intervals to 3, 5, and 7% CO2, the change in pH of ECF in the MRN was ∼50% of the change in plasma pH (10). It was speculated that the relatively lesser change in the MRN ECF pH was due to local H+ buffering mechanisms, such as an increase in blood flow to this region. In the present study, however, we found that the same protocol for inducing an acute global respiratory acidosis reduces ECF pH in the preBötzC and plasma pH equally. Others have found that intracellular acidosis during global acidosis is also not uniform over different medullary regions (14). These findings suggest that local H+ regulation is not uniform throughout the brain stem; thus, for all chemoreceptors that have equal sensitivity, the chemoreceptors at different sites in the brain stem would not contribute equally to the hyperpnea during a systemic, whole body hypercapnic acidosis. Thus the data indicate that the response to FA is indeed not uniform over many chemosensitive sites.

Past and the present studies provide insight into the issue of the need for chemoreceptors at widespread sites in the brain. Nattie et al. (4, 20, 21) have proposed that chemoreceptors at widespread sites are needed to serve different physiological functions. For example, data from their studies suggest the effect on breathing and other physiological functions is state dependent (4, 20, 21). The key findings from this study are as follows: 1) during global acidosis, ECF pH does not change the same in the preBötzC as previously found in the MRN; and 2) the ventilatory and overall physiological responses to FA in the preBötzC are not qualitatively or quantitatively the same as previously shown for other brain sites. Accordingly, the data suggest that not all chemoreceptors are specifically respiratory, and that some affect other physiological functions that are required to meet the multiple physiological needs imposed by global acidosis. Finally, it seems intuitive to have widespread chemoreceptor sites, with variable response characteristics, rather than a single site with powerful response characteristics because, with the latter scenario, a FA at a powerful site would create an alkalosis throughout the remainder of the brain.

GRANTS

The authors’ work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-25739 and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

For the present study, we attempted to measure ECF pH in the preBötzC of an awake goat during MD. Unfortunately, the pH electrodes we had used in our previous study had deteriorated and were not functional. We attempted to purchase the same type and size of the electrodes for the present study, but we were only able to obtain a larger electrode. As a result, the MTs required for insertion of both the electrodes and dialysis probe were 1.7 mm (outer diameter) compared with 1.27 mm (outer diameter) in our previous studies. We implanted the larger MTs in the preBötzC area of one goat, but the goat was sacrificed 2 days after surgery due to lack of recovery from severe postural, feeding, and respiratory defects. Histology revealed that destruction of the medulla was over nearly 3 mm surrounding the MT tract. Accordingly, because of these findings, we did not feel justified to attempt another goat, particularly since the ECF pH measurements during global brain acidosis change preBötzC pH more than global acidosis in the medullary raphe. Thus we are confident that MD in the preBötzC decreased ECF pH as much, or more than, MD in the raphe (10).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernard DG, Li A, Nattie EE. Evidence for central chemoreception in the midline raphe. J Appl Physiol 80: 108–115, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coates EL, Li A, Nattie EE. Widespread sites of brain stem ventilatory chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol 75: 5–14, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean JB, Bayliss DA, Erickson JT, Lawing WL, Millhorn DE. Depolarization and stimulation of neurons in nucleus tractus solitarii by carbon dioxide does not require chemical synaptic input. Neuroscience 36: 207–216, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman JL, Mitchell GS, Nattie EE. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu Rev Neurosci 26: 239–266, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filosa JA, Dean JB, Putnam RW. Role of intracellular and extracellular pH in the chemosensitive response of rat locus coeruleus neurones. J Physiol 541: 493–509, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray PA, Rekling JC, Bocchiaro CM, Feldman JL. Modulation of respiratory frequency by peptidergic input to rhythmogenic neurons in the preBotzinger complex. Science 286: 1566–1568, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyenet PG, Sevigny CP, Weston MC, Stornetta RL. Neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing cells of the ventral respiratory group are functionally heterogeneous and predominantly glutamatergic. J Neurosci 22: 3806–3816, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bayliss DA, Mulkey DK. Retrotrapezoid nucleus: a litmus test for the identification of central chemoreceptors. Exp Physiol 90: 247–253, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodges MR, Opansky C, Qian B, Davis S, Bonis J, Bastasic J, Leekley T, Pan LG, Forster HV. Transient attenuation of CO2 sensitivity after neurotoxic lesions in the medullary raphe area of awake goats. J Appl Physiol 97: 2236–2247, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodges MR, Klum L, Leekley T, Brozoski D, Bastasic J, Davis S, Wenninger JM, Feroah TR, Pan LG, Forster HV. Effects on breathing in awake and sleeping goats of focal acidosis in the medullary raphe. J Appl Physiol 96: 1815–1824, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodges MR, Martino P, Davis S, Opansky C, Pan LG, Forster HV. Effects on breathing of focal acidosis at multiple medullary raphe sites in awake goats. J Appl Physiol 97: 2303–2309, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson SM, Trouth CO, Smith JC. Chemosensitivity of respiratory pacemake neurons in the preBotzinger complex in vitro (Abstract). Neuroscience 24: 875, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaManna JC, Maxwell N, Xu K, Haxhiu MA. Differential expression of intracellular acidosis in rat brainstem regions in response to hypercapnic ventilation. Adv Exp Med Biol 536: 407–413, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li A, Randall M, Nattie EE. CO2 microdialysis in retrotrapezoid nucleus of the rat increases breathing in wakefulness but not in sleep. J Appl Physiol 87: 910–919, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeschcke HH, Mitchell RA, Katsaros B, Perkins JF, Konig A. Interaction of intracranial chemosensitivity with peripheral afferents to the respiratory centers. Ann N Y Acad Sci 109: 651–660 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martino PF, Hodges MR, Davis S, Opansky C, Pan LG, Krause KL, Qian B, Forster HV. CO2/H+ chemoreceptors in the cerebellar fastigial nucleus do not uniformly affect breathing of awake goats. J Appl Physiol 101: 241–248, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martino PF, Davis S, Opansky C, Krause KL, Bonis JM, Pan LG, Qian B, Forster HV. The cerebellar fastigial nucleus contributes to CO2-H+ ventilatory sensitivity in awake goats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 157: 242–251 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCrimmon DR, Monnier A, Hayashi F, Zuperku EJ. Pattern formation and rhythm generation in the ventral respiratory group. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 27: 126–131, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nattie EE, Li A. CO2 dialysis in the medullary raphe of the rat increases ventilation in sleep. J Appl Physiol 90: 1247–1257, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nattie EE, Li A. CO2 dialysis in nucleus tractus solitarius region of rat increases ventilation in sleep and wakefulness. J Appl Physiol 92: 2119–2130, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pineda J, Aghajanian GK. Carbon dioxide regulates the tonic activity of locus coeruleus neurons by modulating a proton and polyamine sensitive inward rectifier potassium current. J Neurosci 77: 723–743, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rekling JC, Feldman JL. PreBotzinger complex and pacemaker neurons: hypothesized site and kernel for respiratory rhythm generation. Annu Rev Physiol 60: 385–405, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richerson GB Response to CO2 of neurons in the rostral ventral medulla in vitro. J Neurophysiol 73: 933–944, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruangkittisakul A, Schwarzacher SW, Secchia L, Poon BY, Ma Y, Funk GD, Ballanyi K. High sensitivity to neuromodlator-activated signaling pathways at physiological [K+] of confocally imaged respiratory center neurons in on-line calibrated newborn rat brainstem slices. J Neurosci 26: 11870–11880, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruangkittisakul A, Schwarzacher SW, Secchia L, Poon BY, Ma Y, Funk GD, Ballanyi K. Generation of eupnea and sighs by a spatiochemically organized inspiratory network. J Neurosci 28: 2447–2458, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlaefke ME, Kille KF, Loeschcke HH. Elimination of central chemosensitivity by coagulation of a bilateral area on the ventral medullary surface in awake cats. Pflügers Arch 378: 231–241, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith JC, Ellenberger HH, Ballanyi K, Richter DW, Feldman JL. PreBotzinger complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science 254: 726–729, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon IC, Edelman NH, Neubauer JA. Patterns of phrenic motor output evoked by chemical stimulation of neurons located in the preBotzinger complex in vivo. J Neurophysiol 81: 1150–1161, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solomon IC, Edelman NH, O'Neal MH. CO2/H+ chemoreception in the cat pre-Botzinger complex in vivo. J Appl Physiol 88: 1996–2007, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solomon IC Focal CO2/H+ alters phrenic motor output response to chemical stimulation of cat pre-Botzinger complex in vivo. J Appl Physiol 94: 2151–2157, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song G, Poon CS. Functional and structural models of pontine modulation of mechanoreceptor and chemoreceptor reflexes. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 143: 281–292, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stornetta RL, Rosin DL, Wang H, Sevigny CP, Weston MC, Guyenet PG. A group of glutamatergic interneurons expressing high levels of both neurokinin-1 receptors and somatostatin identifies the region of the preBotzinger complex. J Comp Neurol 455: 499–512, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Stornetta RL, Rosin DL, Guyenet PG. Neurokinin-1 receptor-immunoreactive neurons of the ventral respiratory group in the rat. J Comp Neurol 434: 128–146, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wenninger JM, Pan LG, Klum L, Leekley T, Bastastic J, Hodges MR, Feroah T, Davis S, Forster HV. Small reduction of neurokinin-1 receptor-expressing neurons in the pre-Botzinger complex area induces abnormal breathing periods in awake goats. J Appl Physiol 97: 1620–1628, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wenninger JM, Pan LG, Klum L, Leekley T, Bastastic J, Hodges MR, Feroah TR, Davis S, Forster HV. Large lesions in the pre-Botzinger complex area eliminate eupneic respiratory rhythm in awake goats. J Appl Physiol 97: 1629–1636, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu F, Frazier DT. Role of the cerebellar deep nuclei in respiratory modulation. Cerebellum 1: 35–40, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]