Abstract

Equilibrative sugar uptake in human erythrocytes is characterized by a rapid phase, which equilibrates 66% of the cell water, and by a slow phase, which equilibrates 33% of the cell water. This behavior has been attributed to the preferential transport of β-sugars by erythrocytes (Leitch JM, Carruthers A. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C974–C986, 2007). The present study tests this hypothesis. The anomer theory requires that the relative compartment sizes of rapid and slow transport phases are determined by the proportions of β- and α-sugar in aqueous solution. This is observed with d-glucose and 3-O-methylglucose but not with 2-deoxy-d-glucose and d-mannose. The anomer hypothesis predicts that the slow transport phase, which represents α-sugar transport, is eliminated when anomerization is accelerated to generate the more rapidly transported β-sugar. Exogenous, intracellular mutarotase accelerates anomerization but has no effect on transport. The anomer hypothesis requires that transport inhibitors inhibit rapid and slow transport phases equally. This is observed with the endofacial site inhibitor cytochalasin B but not with the exofacial site inhibitors maltose or phloretin, which inhibit only the rapid phase. Direct measurement of α- and β-sugar uptake demonstrates that erythrocytes transport α- and β-sugars with equal avidity. These findings refute the hypothesis that erythrocytes preferentially transport β-sugars. We demonstrate that biphasic 3-O-methylglucose equilibrium exchange kinetics refute the simple carrier hypothesis for protein-mediated sugar transport but are compatible with a fixed-site transport mechanism regulated by intracellular ATP and cell shape.

Keywords: carrier-mediated transport, transport kinetics, transport regulation

the accumulated results of more than 60 years of intensive study reveal important inconsistencies between the experimental behavior of the human erythrocyte glucose transport system and the predictions of models for carrier-mediated solute transport (4, 12, 14, 17, 34, 41, 44, 48, 52). One such inconsistency is multiphasic net and exchange sugar import in which erythrocyte sugar uptake is characterized by the rapid equilibration of 66% of the cell water space followed by the slower equilibration of the remaining cell water (20, 31, 40). The expected result is a single phase of sugar uptake. This and other inconsistencies are not explained by errors in transport determinations or data interpretation (40). Rather, factors extrinsic to the transport process appear to contribute to the operational complexity of erythrocyte sugar transport (14, 52, 53).

Erythrocyte sugar transport is mediated by the glucose transport protein GLUT1 (50) and is directly modulated by cytoplasmic ATP, although the mechanism of GLUT1 regulation is only partially resolved (10). Biphasic sugar transport is present only in ATP-containing red blood cells and is replaced by a single transport process when cytoplasmic ATP is depleted (20, 31, 40). ATP-GLUT1 interactions promote GLUT1 conformational changes (10), and it has been suggested that these changes result in ATP-dependent sugar occlusion or binding within GLUT1 cytoplasmic domains before slow sugar release into cytosol (9, 32). However, demonstrations of multiphasic equilibrium exchange transport at sugar concentrations 1,000-fold greater than red cell GLUT1 concentration are incompatible with this hypothesis (40).

The relative sizes of fast (66% cell volume) and slow (33% cell volume) 3-O-methylglucose (3MG) transport compartments correspond exactly to the equilibrium distribution of β- and α-3MG in aqueous solution (66% β:33% α), suggesting that ATP binding promotes GLUT1 preference for β-sugar (40). Transport specificity for sugar epimers is evident from studies with the glucose epimer galactose (an axial C-4 hydroxyl group), which is transported with 10-fold lower affinity than d-glucose (26). Glucose anomerization is slowed by deuterium oxide (D2O) and acidic pH (35, 47). These agents also modify steady-state sugar transport kinetics (7, 19, 51). GLUT1 specificity for sugar anomers has been studied previously, but with contradictory conclusions. Human erythrocyte β-d-glucose metabolism is faster at physiological sugar concentrations (24, 46), but α-d-glucose utilization is more rapid at subsaturating concentrations (45). Rat erythrocytes have been shown to preferentially utilize α-d-glucose (46) or β-d-glucose (22) as a glycolytic substrate. Faust (23) found that β-d-glucose penetrates human red blood cells nearly three times more rapidly than α-d-glucose. Other studies report no difference in the rate of d-glucose anomer uptake (15), that β-d-glucose is imported 1.5 times faster than α-d-glucose (49), or that α-d-glucose exit is twice as fast as β-d-glucose (39). Competition studies using unlabeled α- or β-d-glucose to inhibit radiolabeled d-glucose zero-trans uptake demonstrate identical affinity for α- and β-d-glucose (15), although we now understand that this assay is not the most discriminating test of anomeric specificity (40). The preference for 1-position fluoroanalogs is impossible to compare directly, because only β-1-deoxy-1-fluoroglucose is transported (43). The apparent inhibition constant [Ki(app)] for β-fluoroanalog isomer inhibition of sorbose import is 15 mM, whereas Ki(app) for the α-isomer is 78 mM (8). α-d-Glucose is 37% more effective than β-d-glucose in promoting GLUT1 conformational changes (3). GLUT1 tryptophan quenching by α- and β-d-glucose indicates that β-d-glucose is favored at higher temperatures, whereas α-d-glucose is preferred at lower temperatures (36).

The literature, therefore, presents multiple, contradictory reports of anomeric specificity in human red cell sugar transport. It becomes necessary, therefore, to test the anomer hypothesis with several independent methods. The present study assumes this challenge and demonstrates that GLUT1 lacks anomeric specificity regardless of intracellular ATP content.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

De-identified human blood was obtained from Biological Specialties. Porcine kidney mutarotase was purchased from Calzyme Laboratories. d-[14C]glucose and 2-deoxy-d-[3H]glucose ([3H]2DG) were purchased from Amersham. 3-O-[3H]methylglucose ([3H]3MG), d-[3H]mannose, and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemicals.

Solutions.

Kaline consisted of 150 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Lysis buffer contained 10 mM Tris·HCl and 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. Sugar-stop solution comprised ice-cold kaline containing 20 μM cytochalasin B (CCB) and 200 μM phloretin.

Red blood cells.

Red blood cells were isolated by washing whole human blood in 4 or more volumes of ice-cold kaline followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Serum and buffy coat were removed by aspiration, and the wash, centrifugation, and aspiration cycle was repeated until the buffy coat was no longer visible. Cells were resuspended in 4 volumes of sugar-free or sugar-containing kaline and incubated for 1 h at 37°C to deplete or load intracellular sugar.

Red cell ghosts.

Ghosts were formed by reversible hypotonic lysis of red blood cells. Red blood cells were suspended in 10 volumes of ice-cold lysis buffer for 10 min. Membranes were harvested by centrifugation at 27,000 g for 20 min and subjected to repeated wash/centrifugation cycles in ice-cold lysis buffer until the membranes appeared light pink (∼3 cycles). Ghosts were washed with 10 volumes of ice-cold kaline and collected by centrifugation at 27,000 g. Harvested membranes were resealed by incubation in 4 volumes of kaline ± 4 mM ATP (37°C) for 1 h and collected by centrifugation at 27,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Resealed ghosts were stored on ice until used.

Net sugar uptake.

Sugar-depleted cells or ghosts were incubated in 20 volumes of ice-cold kaline containing 100 μM unlabeled sugar and 0.5 μCi/ml labeled sugar. Uptake proceeded for 6 s to 3 h and was arrested by addition of ice-cold stop buffer followed by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 1 min. The supernatant was aspirated, and pelleted ghosts were washed with 20 volumes of stop buffer and recentrifuged, and the supernatant was aspirated. The ghost pellet was extracted with 500 μl of 3% perchloric acid and centrifuged, and samples of the clear supernatant were counted in duplicate. Zero time points were obtained by adding sugar-stop solution to ghosts, followed by sugar uptake medium. Samples were processed immediately. Radioactivity associated with cells at zero time was subtracted from all nonzero time points. Equilibrium time points were collected using an overnight incubation. All time points were normalized to the equilibrium time point. All solutions and tubes used in the assay were preincubated on ice for 30 min before the start of the experiment. Triplicate samples were processed for each time point.

Sugar equilibrium exchange uptake.

Ghosts were resealed in the presence of 1 or 2.5 mM unlabeled sugar(s) and centrifuged, and the supernatant was aspirated. Ghosts were then incubated in 20 volumes of ice-cold kaline containing the same concentration of unlabeled sugar(s) plus 0.5 μCi/ml radiolabeled sugar. Exchange proceeded for 6 s to 10 h and was stopped by the addition of ice-cold sugar stop. Ghosts were processed as described above with net sugar uptake.

Proton NMR.

Data were collected in D2O at 24°C using a 400-MHz Oxford NMR.

Sugar anomerization kinetics.

Anomerization was measured by optical rotation using a Rudolph Autopol II polarimeter. Freshly dissolved sugar (10 or 100 mM) in temperature-equilibrated kaline ± 4 mM ATP was placed in a 10-ml, 10-cm path length thermojacketed cell, and optical rotation was measured over time. For mutarotase experiments, an appropriate amount of 1,000 U/ml mutarotase in kaline was placed into the thermojacketed cell and allowed to equilibrate before addition of freshly dissolved 10 mM d-glucose in kaline.

HPLC analysis of sugar anomers.

Sugar anomers were chromatographically separated using a Bio-Rad HPX-87C column as previously described (6). The column was equilibrated on ice with distilled H2O as the mobile phase. Unlabeled sugars were detected using a Waters model 410 differential refractometer, and radiolabeled sugars were detected using a Packard 505TR flow scintillation analyzer.

Red blood cell and ghost electron microscopy.

Scanning electron microscopy of red blood cells and ghosts was carried out as previously described (40).

Data analysis and simulations.

Curve fitting was performed by nonlinear regression using the software package Kaleidagraph (version 4.04; Synergy Software, Reading, PA). Time course simulations and parameter fitting were made by fourth-order Runge-Kutta numerical integration and the method of least squares using the software program Berkeley Madonna (version 8.3.22).

Sugar transport in the presence of intracellular ATP is assumed to follow simple Michaelis-Menten kinetics where net sugar uptake sugar by a fixed site transporter (12) or an alternating carrier (63) is described by

|

(1) |

where v is unidirectional uptake of α-sugar, v

is unidirectional uptake of α-sugar, v is unidirectional uptake of β-sugar, v

is unidirectional uptake of β-sugar, v is unidirectional exit of α-sugar, and v

is unidirectional exit of α-sugar, and v is unidirectional exit of β-sugar. In expanded form, this is given as

is unidirectional exit of β-sugar. In expanded form, this is given as

|

(2) |

where S1 and S2 are intra- and extracellular sugar, respectively, superscipts α and β indicate α- and β-anomers, Kα and Kβ are carrier intrinsic affinity constants for α- and β-anomers, respectively, R is 1/Vmax for zero-trans exit of α-sugar, R

is 1/Vmax for zero-trans exit of α-sugar, R is 1/Vmax for zero-trans exit of β-sugar, R

is 1/Vmax for zero-trans exit of β-sugar, R is 1/Vmax for zero-trans entry of α-sugar, R

is 1/Vmax for zero-trans entry of α-sugar, R is 1/Vmax for zero-trans entry of β-sugar, R

is 1/Vmax for zero-trans entry of β-sugar, R is 1/Vmax for exchange transport of α-sugar, R

is 1/Vmax for exchange transport of α-sugar, R is 1/Vmax for exchange transport of β-sugar, and R

is 1/Vmax for exchange transport of β-sugar, and R = R

= R = 1/Vmax for heteroexchange transport of α- and β-sugar. Because transport is passive, the following must hold true:

= 1/Vmax for heteroexchange transport of α- and β-sugar. Because transport is passive, the following must hold true:

|

(3) |

In the absence of ATP, differential transport of anomers is lost and Eq. 2 collapses to its normal form:

|

(4) |

where K and R terms are as described above. Under these conditions, the transporter displays equal affinity and capacity for α- and β-anomers of any given sugar, and each anomer should be transported in proportion to its concentration in solution.

When S1 = S2 (equilibrium exchange) and unidirectional sugar fluxes are measured using radiolabeled sugar (Q), transport in the presence of intracellular ATP is described by Eqs. 5 and 6:

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

where Q1 and Q2 are intra- and extracellular radiolabeled sugar, respectively. When intracellular ATP is absent, differential transport of anomers is lost and Eq. 6 reduces to

|

(7) |

Under these conditions, the transporter displays equal affinity and capacity for α- and β-anomers of any given sugar, and each anomer should be transported in proportion to its concentration in solution.

Interconversion of α- and β-d-glucose by mutarotation is described by

|

(E8a) |

|

(E8b) |

where Glc is the total d-glucose concentration, α and β are the fractions of sugar that exit as α- and β-anomers, and kα and kβ are first-order rate constants for conversion of α-Glc to β-Glc and β-Glc to α-Glc, respectively. kβ/kα = 2 for d-glucose and 3MG, kβ/kα = 1.22 for [3H]3MG, and kobs = kα + kβ. Mutarotase increases kα and kβ but does not alter the relationships kβ/kα = 2 and kobs = kα + kβ.

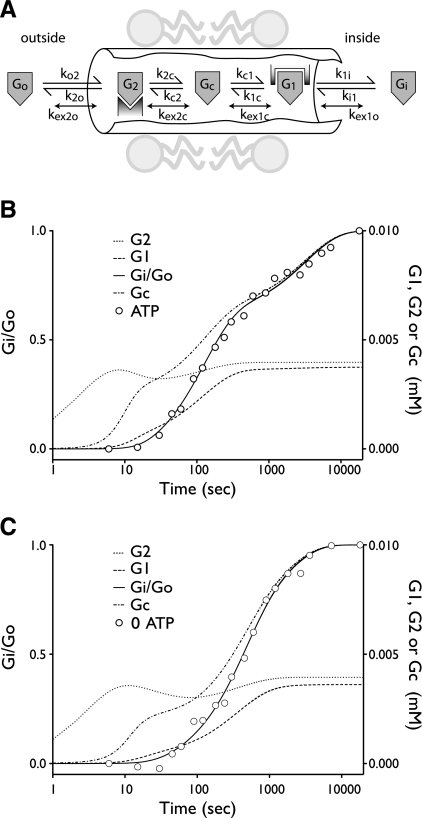

Sugar transport via a fixed site transporter displaying geminate exchange between endo- (e1) and exofacial (e2) sugar binding sites and bulk solution sugar or intersite cavity sugar is illustrated in Fig. 6. With G defined as radiolabeled sugar and S as unlabeled sugar, sugar flows (JG or JS) between interstitium (o), e2, intersite cavity (c), e1, and cytoplasm (i) are described by:

|

(E9a) |

|

(E9b) |

|

(E9c) |

|

(E9d) |

|

(E9e) |

|

(E9f) |

|

(E9g) |

|

(E9h) |

where G2 and G1 refer to the concentrations of G bound at sites 1 and 2, respectively, and Gc is the concentration of intersite cavity G. All true second-order rate constants (ko2, kc2, kc1, and ki1) are converted to pseudo first-order constants by multiplying by the GLUT1 concentration. We have simplified the solution by assuming kex = kexo2 = kex2c = kex1c = kex1i and ko2 = kc2 = kc1 = ki1. Ko = k2o/ko2 and Ki = k1i/ki1. For a passive transport system, ko2k2ckc1k1i = ki1k1ckc2k2o.

Fig. 6.

A model for ATP-dependent biphasic equilibrium exchange sugar transport in erythrocytes. A: schematic view of the erythrocyte glucose transport protein (GLUT1) translocation pathway. Exo- and endofacial sugar binding sites (e2 and e1, respectively) are connected by an intersite cavity. Reversible flows of sugar (G) between binding sites and between binding sites and bulk solvent are indicated by the appropriate rate constants. When sugar occupies e1, e2, and the central cavity (c), sugars may exchange more rapidly between bound and free states (kex). B: simulated (curves) and actual (○) exchange transport data (experimental data taken from Ref. 40) in cells containing 4 mM ATP and equilibrated in 2.5 mM 3MG. Ordinate at left, intracellular radiolabeled 3MG (Gi)/extracellular radiolabeled 3MG (Go); ordinate at right, concentrations of G bound at site 1 (G1), the intersite cavity (Gc), or site 2 (G2) in mM; abscissa, time in seconds. These simulations assume that Go is 10 μM, [GLUT1] is 10 μM, and the intersite cavity volume is 7.5 × 10−25 liter. C: data are presented as described in B except simulating data were obtained from cells lacking ATP. The results of simulations in B and C are summarized in Table 6.

RESULTS

Compartment sizes do not correlate with equilibrium anomer distributions.

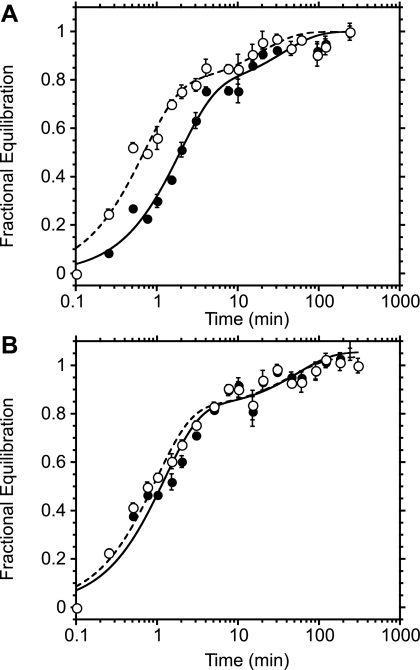

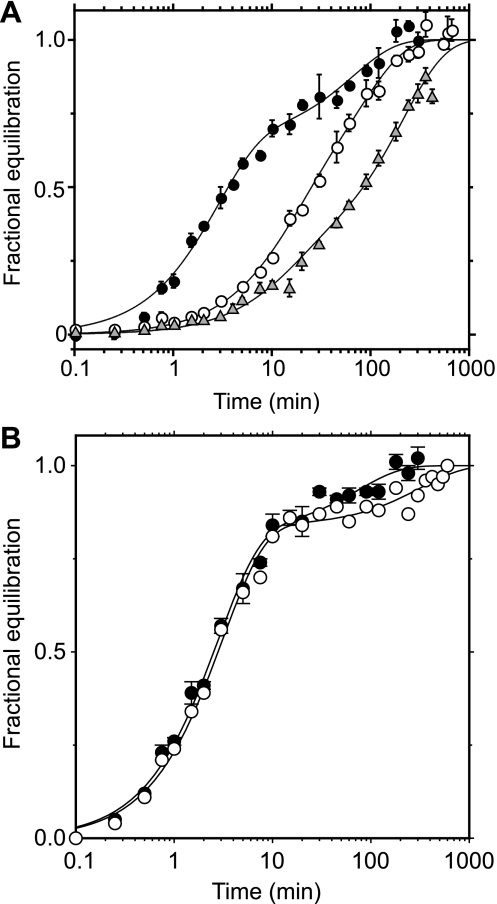

Analysis of equilibrium anomer distributions of aqueous sugars by proton NMR and by HPLC yielded similar results (Table 1). Aqueous d-glucose and 3MG are characterized by equilibrium anomer distributions of ∼66% β-sugar and 33% α-sugar. The 2-position appears to determine anomer distributions, because 2DG (missing the 2-position hydroxyl) is almost equally populated as β- and α-sugar (55 and 45%, respectively), whereas d-mannose (the 2-position epimer of d-glucose) equilibrates as 33% β- and 66% α-sugar. Exchange 3MG, d-glucose, 2DG, or d-mannose transport was examined in the presence and absence of intracellular ATP. Intracellular ATP induced biphasic transport (Fig. 1) of all sugars. Transport compartment sizes, however, did not always correlate with equilibrium anomer distributions of sugars (Table 1). The fast transport compartment was 67% of total transport space for all substrates tested. This is higher than expected for 2DG and d-mannose but is consistent with the equilibrium β-sugar contents of d-glucose and 3MG. Experiment-to-experiment variations in transport compartment sizes made it necessary to simultaneously measure exchange transport of different sugars within the same population of ghosts by dual isotope separation. Simultaneous exchange uptake measurements of 2.5 mM d-glucose and 3MG (Fig. 1A) and of d-glucose and 2DG (Fig. 1B) in ghosts resealed with ATP demonstrated that the transport compartment sizes of d-glucose, 3MG, and 2DG were not significantly different. Thus compartment sizes are not consistently related to relative equilibrium proportions of α- and β-sugars in solution.

Table 1.

Equilibrium hexose anomer and transport compartment distributions

| Sugar |

Method of Anomer Analysis |

Rapid Transport Compartment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Proton NMR |

HPLC

|

||||

| %β at Equilibrium | %β Initially | %β at Equilibrium | %β Initially | ||

| d-Glucose | 66.8 | 13.0 | 64.0 | ||

| [3H]glucose* | 69.0 | 74±7 | |||

| 3MG | 67.4 | 22.5 | 58.0,* 63.0† | 17.0 | |

| [3H]3MG‡ | 55.0 | 67±11 | |||

| 2DG | 54.6 | 75.0 | 57.0§ | 71±10 | |

| d-Mannose | 36.7 | 12.3 | 32.0§ | 54±5 | |

| Average | 67 | ||||

β-Anomer at equilibrium (expressed as %total sugar) was detected after dissolved sample was allowed to rest at room temperature for at least 48 h, whereas initial β-anomer (expressed as %total sugar) was detected within 5 min of dissolving the sample in ice-cold deuterium oxide (D2O) or kaline. The rapid transport component is the percentage of the total 3-O-methylglucose (3MG)-accessible cell space that is equilibrated by the rapid transport phase (shown as means ± SE). The size of the slow transport compartment is 100 minus rapid compartment size.

At 100 mM.

At 200 μM.

Radiolabeled substrates are amenable only to HPLC analysis due to low concentration and are available only at anomeric equilibrium.

2-Deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) and d-mannose are not baseline resolved with the HPLC method, and results were calculated by deconvoluting overlapping Gaussian peak areas.

Fig. 1.

Simultaneous exchange transport of multiple sugar substrates. Ordinate, fractional equilibration of cell water with extracellular radiolabeled sugar; abscissa, time in minutes (note log scale). Each point represents the mean ± SE of at least 3 separate determinations. A: simultaneous exchange of 2.5 mM 3-O-methylglucose (3MG; •) and 2.5 mM d-glucose (○) in red cell ghosts containing 4 mM intracellular ATP. Curves were computed by nonlinear regression assuming the biexponential form A(1 −  ) + (1 − A)(1 −

) + (1 − A)(1 −  ), where k1 and k2 are the observed rate constants for phases 1 and 2, respectively, and A is the fractional component of total uptake described by phase 1. For 3MG, k1 = 0.53 ± 0.06 min−1, k2 = 0.03 ± 0.01 min−1, and A = 0.76 ± 0.05. For d-glucose, k1 = 1.45 ± 0.2 min−1, k2 = 0.05 ± 0.02 min−1, and A = 0.78 ± 0.05. B: simultaneous exchange of 2.5 mM 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG; •) and 2.5 mM d-glucose (○) in red cell ghosts containing 4 mM intracellular ATP, 2.5 mM 2DG, and 2.5 mM d-glucose. Curves were computed by nonlinear regression assuming the biexponential form described in A. For 2DG, k1 = 0.75 ± 0.1 min−1, k2 = 0.04 ± 0.03 min−1, and A = 0.73 ± 0.07. For d-glucose, k1 = 0.93 ± 0.1 min−1, k2 = 0.04 ± 0.02 min−1, and A = 0.74 ± 0.05.

), where k1 and k2 are the observed rate constants for phases 1 and 2, respectively, and A is the fractional component of total uptake described by phase 1. For 3MG, k1 = 0.53 ± 0.06 min−1, k2 = 0.03 ± 0.01 min−1, and A = 0.76 ± 0.05. For d-glucose, k1 = 1.45 ± 0.2 min−1, k2 = 0.05 ± 0.02 min−1, and A = 0.78 ± 0.05. B: simultaneous exchange of 2.5 mM 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2DG; •) and 2.5 mM d-glucose (○) in red cell ghosts containing 4 mM intracellular ATP, 2.5 mM 2DG, and 2.5 mM d-glucose. Curves were computed by nonlinear regression assuming the biexponential form described in A. For 2DG, k1 = 0.75 ± 0.1 min−1, k2 = 0.04 ± 0.03 min−1, and A = 0.73 ± 0.07. For d-glucose, k1 = 0.93 ± 0.1 min−1, k2 = 0.04 ± 0.02 min−1, and A = 0.74 ± 0.05.

Anomerization rate is without effect on the slow phase of transport.

The anomer transport hypothesis predicts that biphasic sugar transport kinetics are observed only when the rate of sugar anomerization is significantly slower than the slowest phase of sugar transport (40). The rate of 3MG anomerization (as measured by circular dichroism, CD) is 10-fold slower than the slow phase of transport (40). d-Glucose, 2DG, and d-mannose do not have measurable CD signals. Anomerization of these sugars was measured by polarimetry. Anomerization is first-order in sugar concentration. The temperature dependence of d-glucose, 3MG, 2DG, and d-mannose anomerization is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Temperature dependence of sugar anomerization

| Sugar | Mutarotase, U/ml | [Sugar], mM |

Anomerization Rate, min−1 × 105 |

Activation Energy, kJ/mole | Slow Transport Rate, min−1 × 105

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4°C | 20°C | 37°C | 4°C | ||||

| Glucose | 0 | 10 | 509±2 | 1,840±6 | 6,156±25 | 52±1 | 4,600±2,400 |

| 100 | 462±2 | 1,679±1 | 6,720±3 | 60±2 | |||

| 1 | 10 | 5,680±20 | 10,976±54 | 33,771±180 | 45±6 | 6,900±5,300* | |

| 100 | 1,263±2 | ||||||

| 10 | 10 | 31,800±400 | 96,217±934 | 172,010±2,160 | 31±6 | ||

| 39,700±200† | |||||||

| 100 | 9,063±7 | ||||||

| 50 | 10 | 85,200±800 | |||||

| 100 | 100 | 76,000±300 | |||||

| 3MG | 0 | 10 | 458.9±1.5 | 1,622±10 | 5,014±23 | 50±1 | 1,900±1,000 |

| 100 | 498.9±0.7 | 1,562±1 | 6,167±7 | 59±3 | |||

| 10 | 10 | 411.3±2.8 | 1597±9 | 5,399±21 | 54±1 | ||

| 2DG | 100 | 3,800±5 | 13,220±9 | 59,279±86 | 65±3 | 1,600±600 | |

| Mannose | 100 | 2,292.5±10.8 | 7,332±90 | 33,936±109 | 66±4 | 3,300±1,700 | |

Lyophilized porcine kidney mutarotase was dissolved in kaline at 1,000 U/ml, and aliquots were diluted as necessary. Activation energies were calculated from Arrhenius plots.

d-Glucose exchange in the presence of extracellular and intracellular 500 U/ml exogenous mutarotase.

Anomerization in the presence of 4 mM ATP.

d-Glucose and 3MG anomerization at ice temperature were much slower than the slow rate of transport. However, the same was not true for 2DG and d-mannose. Both 2-position glucose analogs displayed accelerated anomerization kinetics relative to d-glucose, but the temperature dependence of anomerization was unchanged. For these sugars, anomerization rates may exceed the slow rate of transport. Nevertheless, these sugars were transported even more slowly than their more slowly anomerizing parent sugar, d-glucose. Thus there is no correlation between the rate of anomerization of the individual hexoses and their slow rate of uptake.

Exogenous porcine kidney mutarotase accelerates α- and β-d-glucose interconversion by as much as 1,000-fold without altering the equilibrium distribution of anomers. Mutarotase is without effect on 3MG anomerization (Table 2). d-Glucose anomerization in the presence of 50 U/ml mutarotase at 20°C is too fast to measure using manual mixing methodologies.

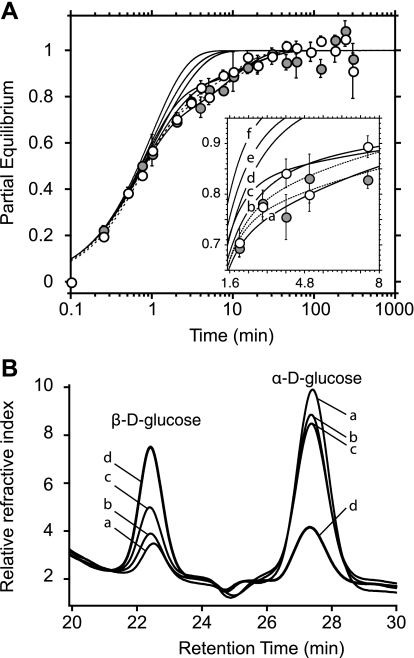

Assuming the anomer specificity hypothesis is correct, our simulations show that resealing a significant mutarotase activity within red cell ghosts will promote monophasic transport even in the presence of ATP (Fig. 2). Extracellular mutarotase should have minimal effect on transport rates and compartment sizes (the fast phase would be a little faster and larger), and transport would remain biphasic. Experimental analysis of d-glucose transport in ghosts lacking and containing 500 U/ml mutarotase ± 4 mM ATP is summarized in Fig. 2A. Predicted transport kinetics are also illustrated. Transport was biphasic in the presence of mutarotase. However, differences would be difficult to observe if mutarotase were active only in the external medium (compare data with curves b and c in Fig. 2A). Our measurements show that ATP did not inhibit mutarotase (see Table 2) and that intracellular mutarotase was indeed active. Mutarotase loaded ghosts contained greater quantities of intracellular β-d-glucose after 5-min exposure to α-d-glucose than did ghosts lacking intracellular mutarotase. This effect was inhibited by the sugar transport inhibitors CCB and phloretin (Fig. 2B, curve c), confirming that glucose must enter the cell to encounter intracellular, catalytically active mutarotase.

Fig. 2.

Effect of mutarotase on d-glucose exchange kinetics. A: ordinate, fractional equilibration of cell water with extracellular radiolabeled sugar; abscissa, time in minutes (note log scale). Transport of 2.5 mM d-glucose was measured without (•) or with (○) 500 U/ml mutarotase resealed inside ghosts containing 4 mM ATP. Each point represents the mean ± SE of at least 3 separate determinations. Dashed curves were drawn by using nonlinear regression assuming the biexponential form described in the legend to Fig. 1. When mutarotase is absent (dashed curve at far right), A = 0.71 ± 0.05, k1 = 1.4 ± 0.2 min−1, and k2 = 0.08 ± 0.03 min−1. When mutarotase is present (dashed curve at far left), A = 0.71 ± 0.06, k1 = 1.3 ± 0.2 min−1, and k2 = 0.11 ± 0.03 min−1. Transport was simulated using Eqs. 1 and 5, and anomerization was simulated using Eqs. 8a and 8b. Transport parameters were Kα = 50 mM, Kβ = 6.3 mM, Vα = 3 mM min−1, and Vβ = 5 mM min−1. Anomerization constants are (proceeding from right to left for solid curves; see inset for detail): a, 0 mutarotase, kobs = 0.005 min −1 inside and outside; b, mutarotase (500 U/ml) present outside at 10% activity, kobs(out) = 0.852 min−1, kobs(in) = 0.005 min−1; c, mutarotase present outside at full activity, kobs(out) = 8.52 min−1, kobs(in) = 0.005 min−1; d, mutarotase active both outside and inside at 10% activity, kobs(out) = kobs(in) = 0.852 min−1; e, mutarotase fully active outside and 10% active inside, kobs(out) = 8.52 min−1, kobs(in) = 0.852 min−1; and f, mutarotase fully active both outside and inside, kobs(out) = kobs(in) = 8.52 min−1. B: ordinate, change in refractive index; abscissa, retention time in minutes. HPLC chromatograms are shown of 2 mM α-d-glucose 1 h after dissolution in ice-cold kaline. The conditions were as follows: a, control d-glucose medium not exposed to ghosts (contained 13% β-sugar); b, extracellular d-glucose after incubation with ghosts resealed without exogenous mutarotase (contained 18% β-sugar); c, extracellular d-glucose after incubation with extensively washed ghosts resealed with 500 U/ml mutarotase and exposed to 10 μM cytochalasin B (CCB) plus 100 μM phloretin (contained 26% β-sugar); and d, extracellular d-glucose after incubation with extensively washed ghosts resealed with 500 U/ml mutarotase (contained 64% β-sugar).

Direct measurements of anomer transport.

If the anomer specificity hypothesis is correct, red blood cells should import a disproportional amount of β-sugar and the interstitium should lose more β-sugar during the early phase of sugar uptake. We used HPLC to separate anomers and refractive index change to measure the anomeric composition of cytosolic and interstitial sugar. The method was verified by monitoring 3MG anomerization in vitro. The initial proportion of β-3MG:α-3MG in freshly prepared “α-3MG” solutions was 20:80, and this ratio increased with time at a rate consistent with the rates of anomerization reported in Table 2.

The amount of sugar within ghosts at early times during transport from media containing 2.5 mM total initial 3MG was too small to measure by refractive index, but changes in extracellular anomer composition were measurable. Simulations suggest that the maximal difference between starting and remaining anomer content occurs at 5 min of uptake at 4°C. Our experiments show that the relative anomer content of extracellular medium was unaffected by sugar import into cells lacking or containing ATP (Table 3).

Table 3.

Analysis of extracellular 3MG anomers remaining after cellular uptake

| Uptake Time | %β Remaining | %β Model Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 min (0 mM ATP) | 63±10* | 67† |

| 5.0 min 0 mM ATP) | 64±5*, 59±1‡ | 67†, 55§ |

| 0.5 min (4 mM ATP) | 71±6* | 65†. 53§ |

| 5.0 min (4 mM ATP) | 64±4*, 57±1‡ | 54†, 42§ |

| Equilibrium ± ATP | 64±2*, 55±1‡ |

β-3MG (expressed as %total sugar; means ± SE) remaining in the extracellular medium was measured by HPLC analysis of medium following sugar uptake into red cell ghosts lacking or containing intracellular ATP. Starting total [3MG] = 2.5 mM. Predicted β-3MG (expressed as %total sugar) remaining in the extracellular medium was determined following sugar uptake into red cell ghosts lacking or containing intracellular ATP. Predicted results in the absence of ATP must match solution equilibrium anomer distributions. Results in the presence of ATP were simulated using Eq. 2 and averaged net uptake data in the presence of intracellar ATP, where the following parameters were computed using the method of least squares: Kα = 20.5 mM, Kβ = 0.15 mM, R12β = R12α = 0.25 min·l·mmol−1, R21β = R21α = 5.9 min·l·mmol−1, and Reeβ = Reeα = Reeαβ = Reeβα = 0.1 min·l·mmol−1.

Analysis of unlabeled 3MG.

Prediction based on an α:β equilibrium of 33:67 as seen for unlabeled 3MG.

Analysis of radiolabeled [3H]3MG.

Prediction based on an α:β equilibrium of 45:55 as seen for [3H]3MG (see Table 1).

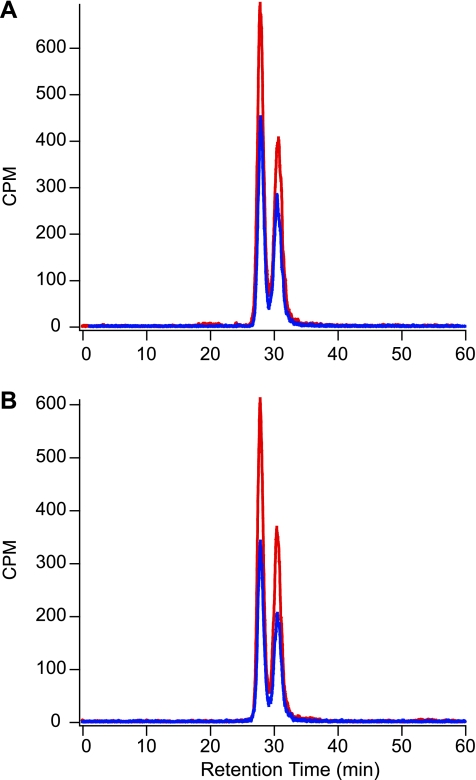

These experiments were repeated using radiolabeled 3MG that, following extraction of cytosol, was chromatographically separated into α- and β-anomers and detected using an in-line radiometric scintillation counter. Radiometric detection of cytosolic 3MG allows direct measurement of [3H]3MG anomers transported into ghosts, greatly increases signal to noise, and permits measurement of unidirectional equilibrium exchange fluxes. We routinely observed that [3H]3MG and unlabeled 3MG had different equilibrium anomer distributions (45:55 α:β vs. 33:66 α:β, respectively; see Table 3). To ensure that the extraction procedure for measuring intracellular sugar did not alter anomer proportions, we subjected medium containing freshly dissolved, unlabeled 3MG to mock cytosol extraction (lysis in ice-cold 3% perchloric acid and neutralization with sodium bicarbonate) without measurable effect on anomer ratios (20:80 β:α). Even at the earliest time points of transport, when the β- to α-anomer ratio of imported radiolabeled sugar is predicted to be greatest, there was no difference in anomeric proportions of intra- and extracellular [3H]3MG (Fig. 3 and Table 4). Thus GLUT1 is able to transport both anomers equally well.

Fig. 3.

Anomeric analysis of intracellular [3H]3MG following transport. Ordinate, counts per minute (CPM); abscissa, retention time in minutes. A: chromatograms of intracellular [3H]3MG following net uptake intervals of 30 s (blue) and 5 min (red). B: chromatograms of intracellular [3H]3MG following equilibrium exchange intervals of 30 s (blue) and 5 min (red).

Table 4.

Anomeric analysis of intracellular 3MG following uptake

| Condition | %β | %β Model | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-trans uptake (0 mM ATP) | |||

| 30 s | 53±2 | 67*, 55† | 9 |

| Zero-trans uptake (4 mM ATP) | |||

| 30 s | 56±1 | 99*, 89† | 12 |

| 5 min | 56±1 | 99*, 78† | 3 |

| Exchange uptake (0 mM ATP) | |||

| 15 s | 53±1 | 67*, 55† | 3 |

| 30 s | 51±2 | 67*, 55† | 3 |

| Exchange uptake (4 mM ATP) | |||

| 30 s | 57±1 | 96*, 97† | 3 |

| 5 min | 57±1 | 83*, 93† | 3 |

| Stock Solutions | 55±1 | 12 |

β-[3H]3MG (expressed as %total intracellular sugar) was analyzed by HPLC 15 s to 5 min after uptake medium was mixed with ghosts lacking or containing intracellular ATP. Predicted intracellular β-[3H]3MG (expressed as %total sugar) was determined upon incubation of ghosts lacking or containing intracellular ATP with uptake medium. Zero-trans uptake in the presence of ATP was approximated using Eqs. 1 and 2 and averaged net uptake data for the presence of intracellular ATP, where the following parameters were computed using the method of least squares: Kα = 20.5 mM, Kβ = 0.15 mM, R12β2 = R12α = 0.25 min·l·mmol−1, R21β = R21α = 5.9 min·l·mmol−1, and Reeβ = Reeα = Reeαβ = Reeβα = 0.1 min·l·mmol−1. Equilibrium exchange uptake in the presence of ATP was calculated using Eqs. 5 and 6 and averaged exchange uptake data for the presence of intracellular ATP, where the following parameters were computed using the method of least squares: Kα = 6.7 mM, Kβ = 0.20 mM, R12β2 = R12α =0.33 min·l·mmol−1, R21β = R21α = 16.7 min·l·mmol−1, and Reeβ = Reeα = Reeαβ = Reeβα = 0.11 min·l·mmol−1. Since transport in the absence of ATP does not display anomer specificity, zero-trans and equilibrium exchange uptake in the absence of ATP reflect the equilibrium solution distributions of sugar anomers. n, Number of experiments.

Prediction based on an α:β equilibrium of 33:67 as seen for unlabeled 3MG.

Prediction based on an α:β equilibrium of 45:55 as seen for [3H]3MG.

Exchange transport is biphasic in the presence of transport inhibitors.

If biphasic sugar exchange transport reflects fast and slow β- and α-d-glucose transport, transport inhibitors should inhibit both fast and slow phases of transport. CCB (10 μM) inhibited both fast and slow transport phases (3- to 5-fold; Fig. 4A and Table 5). 3MG exchange exit was also biphasic, and both phases were inhibited by 10 μM CCB (exit data not shown). However, phloretin (100 μM) inhibited only the fast phase (5-fold; Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of 3MG equilibrium exchange transport. Ordinate, fractional equilibration of cell water with extracellular radiolabeled 3MG; abscissa, time in minutes (note log scale). Each point represents the mean ± SE of at least 3 separate determinations. A: inhibition by intra- and extracellular inhibitors of 2.5 mM 3MG exchange in ghosts resealed with 4 mM ATP. Control (solid circles) exchange was biphasic, consistent with the filling of 2 compartments. In the presence of 10 μM CCB (shaded triangles), an endofacial transport inhibitor, transport remained biphasic and both phases of transport were inhibited nearly equally. Transport in the presence of 100 μM phloretin (open circles), an extracellular binding inhibitor was biphasic but only the fast phase was inhibited. Curves drawn through the points were computed by nonlinear regression assuming the biexponential form described in the legend to Fig. 1. Fit constants are shown in Table 5. B: cytochalasin D (CCD) modulation of 2.5 mM 3MG exchange in ghosts resealed with 4 mM ATP. Control (solid circles) exchange was biphasic, consistent with the filling of 2 compartments. In the presence of 10 μM CCD (open circles), transport remained biphasic but the slow phase of transport was inhibited (see Table 5 for fit constants).

Table 5.

Effect of inhibition on rate constants and compartment sizes during equilibrium exchange in ATP-containing cells

| Inhibitor | Rapid kobs | Slow kobs | Rapid Component Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.36±0.03 | 0.015±0.003 | 66±4 |

| Cytochalisn B (10 μM) | 0.071±0.018 (5.1) | 0.0047±0.0004* (3.2) | 26±4 |

| Phloretin (100 μM) | 0.075±0.014 (4.8) | 0.012±0.001 (1.25) | 40±7 |

| Control | 0.435±0.073 | 0.037±0.012 | 82±2 |

| Cytochalisn D (10 μM) | 0.359±0.039 (1.21) | 0.010±0.005* (3.7) | 83±1 |

All measurements were made at 2.5 mM unlabeled 3MG. All rate constants are first order, have units of min−1, and are shown as means± SE. Rapid compartment size represents the size (percentage of total 3MG-accessible space) of the exchange transport component described by the rapid transport phase and is shown as mean ± SE. The size of the component described by the slow rate constant is 100 minus rapid size. Numbers in parentheses indicate the fold inhibition of each phase relative to uninhibited cells.

Results are significantly different at the 5% level as judged by a paired Student's t-test (n = 3).

CCB is an endofacial site erythrocyte glucose transport inhibitor, whereas phloretin is an exofacial site inhibitor (38). We therefore tested the effects of a second exofacial site inhibitor, maltose (13). Extracellular maltose causes significant cell lysis at concentrations (100 mM) required for effective exchange transport inhibition. We therefore repeated transport measurements using 100 mM sucrose as an osmotic control and incorporating tracer [14C]sucrose (a nontransported sugar) into ghosts to adjust for lysis-induced loss of radioisotope during postquenching washing steps. As with phloretin, we observed significant (7-fold) inhibition of the rapid phase of sugar exchange by 100 mM maltose, but the loss of cellular integrity following long incubation in hyperosmotic medium prevented accurate determination of slow-phase kinetics in both sucrose- and maltose-treated cells.

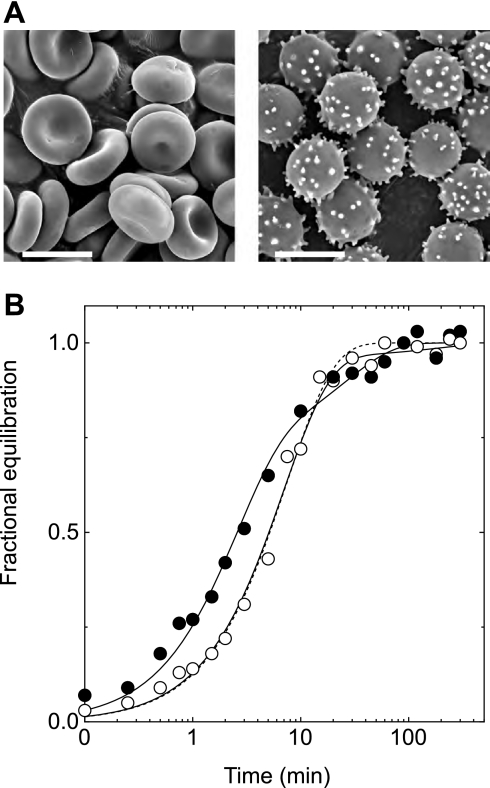

Incubation of human red blood cells with 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) caused echinocytosis (Fig. 5A) (59–61). DNP (10 mM for 10 min) abolished biphasic 3MG exchange transport (Fig. 5B) in freshly isolated red blood cells, resulting in exchange kinetics that resemble those of ATP-depleted ghosts. HPLC analysis of cytosolic nucleotides confirms that DNP treatment does not alter the AMP, ADP, or ATP contents of the red blood cell. This result suggests that altered cell shape modifies erythrocyte sugar transport.

Fig. 5.

3MG exchange in fresh red blood cells treated with and without 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP). A: scanning electron micrograph of samples of control red blood cells (left) and DNP-treated red blood cells (right) used in B. Scale bar, 7 μm. B: ordinate, fractional equilibration of cell water with 3MG; abscissa, time in minutes. Exchange transport of 2.5 mM 3MG was measured in fresh red blood cells at 4°C following 10-min treatment with DNP (○) or no treatment (•). Curves drawn through points are computed by nonlinear regression to the forms 1 − e−kt for DNP-treated cells (dashed line) and A(1 −  ) + (1 − A)(1 −

) + (1 − A)(1 −  ) for control and DNP-treated cells (solid lines). The results are k = 0.13 ± 0.01 min−1 (χ2 = 0.018) for DNP-treated cells; A = 0.74 ± 0.07, k1 = 0.41 ± 0.05 min−1, and k2 = 0.037 ± 0.01 min−1 (χ2 = 0.018) for untreated cells; and A = 0.97 ± 0.03, k1 = 0.141 ± 0.009 min−1, and k2 = 0.006 ± 0.006 min−1 (χ2 = 0.019) for DNP-treated cells. Each point represents the mean ± SE of at least 3 separate determinations.

) for control and DNP-treated cells (solid lines). The results are k = 0.13 ± 0.01 min−1 (χ2 = 0.018) for DNP-treated cells; A = 0.74 ± 0.07, k1 = 0.41 ± 0.05 min−1, and k2 = 0.037 ± 0.01 min−1 (χ2 = 0.018) for untreated cells; and A = 0.97 ± 0.03, k1 = 0.141 ± 0.009 min−1, and k2 = 0.006 ± 0.006 min−1 (χ2 = 0.019) for DNP-treated cells. Each point represents the mean ± SE of at least 3 separate determinations.

Both CCB and cytochalasin D (CCD) modify the cytoskeleton by capping the barbed ends of actin filaments, reducing the steady-state length of actin filaments and inducing the formation of actin nuclei by interacting with monomeric actin with high affinity [Kd(app) ≈ 3 μM (27)]. Unlike CCB, CCD is an extremely low-affinity inhibitor of erythrocyte glucose transport [Ki(app) ≥ 100 μM (Robichaud TK, Henderson PJ, Carruthers A, unpublished observations; Ref. 55)]. CCD was without significant effect on the rapid phase of equilibrium exchange 3MG uptake but inhibited the slow phase with Ki(app) = 4 μM (Fig. 4B and Table 5). Compartment sizes were unaffected by CCD.

DISCUSSION

The present study evaluates the hypothesis that biphasic, equilibrative sugar transport in human red blood cells results from ATP-dependent differential transport of α- and β-sugars by GLUT1. The results of experiments testing four specific predictions of the hypothesis refute this idea. We conclude that the red cell glucose transport protein GLUT1 transports α- and β-sugars with equal avidity and that biphasic sugar transport results from nucleotide-dependent regulation of the intrinsic catalytic properties of GLUT1.

The differential α- and β-sugar transport hypothesis makes four strict predictions. 1) The relative sizes of cellular transport compartments (fast and slow equilibrative volumes) is related to the relative proportions of α- and β-sugars in solution. 2) Acceleration of the rate of α- and β-sugar interconversion (anomerization) to rates that exceed the slow phase of transport will accelerate or eliminate the slow phase of transport. 3) β-3MG and β-d-glucose are transported more rapidly than α-3MG and α-d-glucose. 4) Glucose transport inhibitors must inhibit both fast transport of β-sugar and slow transport of α-sugar.

Our experiments show the following results. 1) The relative sizes of cellular transport compartments (fast and slow equilibrative volumes) are independent of the relative proportions of α- and β-sugars in solution. 2) Acceleration of the rate of α- and β-sugar interconversion (anomerization) is without effect on the slow phase of transport. 3) α- and β-3MG are transported with equal avidity by red blood cells. 4) Exofacial inhibitors of glucose transport (maltose, phloretin) inhibit the fast phase of sugar transport, an endofacial inhibitor and cytoskeleton disruptor (CCB) inhibits both fast and slow phases of transport, and a cytoskeleton disruptor (CCD) inhibits only the slow phase of transport.

Trivial explanations of biphasic transport kinetics (e.g., 3MG transport into functionally distinct populations of cells; see Ref. 40) are excluded by the simultaneous demonstrations of monophasic uridine transport and biphasic 3MG transport in ATP-loaded red cell ghosts and by the observation that extracellular uridine and 3MG equilibrate with identical total cellular volumes (40). Only two explanations remain for ATP-dependent biphasic sugar uptake: 1) biphasic kinetics reflect the intrinsic properties of the transporter when complexed with ATP (11) or 2) ATP-replete cells contain two cytoplasmic compartments separated by a diffusion barrier, and only the larger compartment is bounded by cell membrane containing functional GLUT1 (40). The smaller compartment (33% of the cell water) must also be bound by cell membrane, but in this case the membrane is either devoid of GLUT1 or contains inhibited GLUT1. The juxtaposition of the small compartment and plasma membrane is necessary to explain ENT1-mediated monophasic and rapid equilibration of erythrocyte total cell water with uridine in the presence of intracellular ATP (40).

Reduced glucose exchange between compartments could result from decreased intracellular diffusion (i.e., increased tortuosity or molecular crowding and increased cytoplasmic viscosity). However, the coefficient for sugar self-diffusion must be reduced by at least 1,000-fold to explain limited intracellular diffusion over distances of 3.5 μm or less (62). This seems untenable given estimates of intracellular tortuosity in neurons, brain, and red blood cells of 1–3 (7, 25, 29) and estimates of intracellular viscosity in red blood cells and Xenopus oocytes of 6–15 cP (16, 28). These increases in tortuosity and viscosity relative to aqueous solution could reduce intracellular glucose diffusion by as much as 20-fold but not by the necessary 1,000-fold.

Diminished glucose exchange between compartments is also consistent with an intracellular permeability barrier separating large and small intracellular compartments. We estimate the upper limit for permeation across this hypothetical barrier is 1 × 10−8 cm/s.1 However, ultrastructural studies fail to observe intracellular compartments in erythrocytes (64). Disruption of red cell membrane detergent-resistant microdomains or “lipid rafts” by methyl-β-cyclodextrin-induced cholesterol depletion is without effect on red cell sugar transport (58), suggesting either that red cell GLUT1 is excluded from membrane rafts or that GLUT1 function is unaffected by nonuniform GLUT1 distribution in the cell membrane. In summary, these considerations indicate that the membrane and cytoplasm compartmentalization hypothesis for biphasic, erythrocyte sugar transport is untenable.

If biphasic transport kinetics result from ATP modulation of the intrinsic catalytic properties of GLUT1, what is the underlying mechanism? Two hypotheses are considered. The alternating carrier model posits that the transporter isomerizes between two states: one presenting an endofacial sugar binding site (e1) to the cytoplasm, and a second presenting an exofacial sugar binding site (e2) to the interstitium (37, 42). Sugar import occurs when extracellular sugar complexes with e2 to form eS2, which then undergoes the eS2 → eS1 conformational change, and complexed sugar dissociates into cytoplasm. After reorientation of e1 → e2, the carrier is ready for another round of sugar import. The fixed-site transporter model hypothesizes that the transporter presents e1 and e2 sites simultaneously and that sugars exchange between these sites via a translocation pore (5, 52). Ligand binding studies support the latter hypothesis (13, 33), whereas analysis of available and homology-modeled crystal structures of major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters suggests either multiple, simultaneous substrate binding sites (21, 56) or a single site at any instance (1).

The alternating carrier hypothesis cannot account for ATP-dependent biphasic exchange sugar transport without invoking factors extrinsic to the carrier such as 1) the compartment hypothesis (refuted above) or 2) a time- and ATP-dependent inactivation of the carrier. The latter hypothesis is refuted by demonstrations of biphasic equilibrium exchange transport in freshly made ATP- and 3MG-containing ghosts and in ATP- and 3MG-containing ghosts allowed to rest for 10 h before transport measurement (40). The alternating carrier model also fails in other ways. For example, the model is incompatible with a large body of transport data and may also contravene basic thermodynamic principles (54). Naftalin (54) proposed a modified fixed-site transporter in which the external and internal sugar binding sites of the fixed-site transporter are connected via an internal cavity and that net sugar import involves sugar binding to the exofacial site and dissociation of bound sugar into the internal cavity, whence sugar may reassociate with the exofacial site or associate with the endofacial binding site. Dissociation from the endofacial site into cytoplasm completes the transport cycle (Fig. 6). Accelerated exchange (a hallmark of “carrier-mediated” transport; Ref. 63) is explained when the rate of movement of sugar from endo- or exofacial binding sites into the intersite cavity is accelerated when both binding sites are occupied by sugar or by the presence of intercavity sugar (54). This model builds on the principle of geminate recombination (57) and is consistent with docking studies showing that homology-modeled GLUT1 presents endo- and exofacial sugar binding sites connected by an intersite cavity (21, 56). The model is also compatible with rapid-quench glucose transport studies demonstrating that a transported sugar molecule is biochemically trapped within the GLUT1 translocation pathway when endo- and exofacial binding sites are blocked by inhibitors (9) and that GLUT1-ATP interaction increases GLUT1 sugar occlusion (32). The model is also consistent with the observation that a common membrane protein architecture can mediate both anion channel function and proton-Cl antiport (2) and thus provides a conceptual framework for coevolution of channel and transporter mechanisms from a common ancestor.

We have simulated biphasic 3MG equilibrium exchange transport in ATP-containing cells and monophasic exchange transport in ATP-free cells using such a fixed-site transport mechanism (Fig. 6). These simulations demonstrate that Kd for sugar binding to e2 is at least 10-fold lower than Kd for sugar binding to e1 and are thus consistent with the body of erythrocyte sugar transport data indicating asymmetry in transport [Km(app) for sugar uptake < Km(app) for sugar exit (54)]. Biphasic exchange kinetics are critically dependent on 1) asymmetry in binding affinity (as Kd for sugar binding to e2 approaches Kd for sugar binding to e1, the slow component of transport is accelerated and biphasic transport is lost) and 2) the rate of exchange between intersite cavity sugar and e1 or e2. This rate constant (kex) determines the rate constant for the fast component of transport, and as exchange rates fall, the fast component collapses into the slow transport component. Biphasic transport is unaffected by intersite cavity volume over the range 7.5 × 10−25 liter (the cavity volume predicted in Ref. 56) through 1.5 × 10−22 liter (the approximate volume of a single GLUT1 molecule; Ref. 56).

Our simulations (see Table 6) indicate that ATP modulates fixed-site transport by 1) increasing transport asymmetry (ATP reduces Kd for sugar binding to e2 by 2.7-fold but reduces Kd for sugar binding to e1 by only 1.7-fold) and 2) increasing the rate of exchange between bound sugar and intersite cavity sugar or bulk solvent sugars by 4.5-fold. Our simulations also suggest how endo- and exofacial inhibitors influence transport. The exofacial inhibitors maltose and phloretin inhibit the rapid phase of transport by reducing exchange (kex) between intersite cavity sugar and sugar binding sites by 10-fold. Interestingly, maltose and phloretin also act to reduce Ko for 3MG binding to e2 sites by fivefold, in part by increasing ko2. CCB inhibits rapid and slow transport by reducing kex and Ko by 27- and 10-fold, respectively. These effects on Ko are consistent with previous demonstrations indicating that single occupancy of tetrameric GLUT1 by exofacial maltose (30) or by endofacial CCB (18) allosterically increases the affinity of e2 for 3MG by as much as fivefold. CCD is without effect on the rapid phase of transport but decelerates the slow phase by reducing Ko. CCD has only very low affinity for GLUT1 (55), suggesting that its actions are mediated either by direct but low-affinity effect on GLUT1 to reduce Ko or indirectly by alterations in erythrocyte cytoskeleton. The apparent lack of affinity of CCD for GLUT1 may reflect the lack of effect of CCD on kex and the fact that previous studies did not extend transport measurements out to 60 min or longer, the time at which the slow phase of transport is observable and the effects of CCD on transport become measurable (see Fig. 4B). DNP mimics the ability of ATP depletion to modulate transport, suggesting that its effects are manifest via nonspecific membrane perturbations of GLUT1 function or that DNP displaces ATP from the GLUT1-nucleotide complex. Future studies will need to address these various possibilities.

Table 6.

Effect of modulators of GLUT1-mediated sugar transport on fixed-site transporter function

| Condition or Transport Modulator | Ko, mM | Ki, mM | kex, s−1 | ko2, s−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control ghosts* | 0.025 | 0.26 | 0.008 | 0.139 |

| ATPi (4 mM)* | 0.0093 | 0.2 | 0.0347 | 0.166 |

| Control ghosts + 4 mM ATP† | 0.0062 | 0.326 | 0.0238 | 0.239 |

| Phloretin (100 μM)† | 0.0011 | 0.111 | 0.002 | 0.588 |

| Cytochalasin B (10 μM)† | 0.0004 | 0.107 | 0.0009 | 0.329 |

| Cytochalasin D (10 μM)‡ | Reduced | No change | No change | No change |

Analysis of 3MG equilibrium exchange transport in human erythrocyte ghosts, assuming transport is mediated by a fixed-site carrier (see Fig. 6). Control, ATP-, or inhibitor-modulated exchange data were analyzed according to Eqs. 9a–9g by using a combination of Runge-Kutta numerical integration and Levenberg-Marquardt nonlinear curve fitting. These simulation assume that Go is 10 μM, [GLUT1] is 10 μM, and the intersite cavity volume is 7.5 × 10−25 liter. The resulting parameters are either affinity constants (Ko and Ki) or pseudo-first-order rate constants (kex and ko2). Ko and Ki describe the dissociation constants for 3MG binding to exo- (e2) and endofacial (e1) sites, respectively. kex and ko2 describe the rate of geminate exchange between bound and free 3MG or the rate of 3MG association with unoccupied e1 and e2, respectively.

Curve fits of data in Fig. 1, A and B, of Leitch and Carruthers (40) in which 2.5 mM 3MG equilibrium exchange 3MG uptake was measured in ATP-free (control) and ATP-containing ghosts at 4°C.

Curve fits of data in Fig. 4, A and B.

These results were not successfully modeled, because the size of the small compartment was significantly diminished in these experiments. Simulations show, however, that reduced Ko results in deceleration of the slow phase of transport.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK36081 and DK44888 and American Diabetes Association Grant 1-06-IN-04 (Gail Patrick Innovation Award supported by a generous gift from the Estate of Gail Patrick).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

We assume the small compartment is a sphere, and we calculate the permeability coefficient P as P = k/A, where k = rate constant for filling the small compartment and A = compartment surface area.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramson J, Smirnova I, Kasho V, Verner G, Kaback HR, Iwata S. Structure and mechanism of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Science 301: 610–615, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accardi A, Miller C. Secondary active transport mediated by a prokaryotic homologue of ClC Cl− channels. Nature 427: 803–807, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appleman JR, Lienhard GE. Kinetics of the purified glucose transporter. Direct measurement of the rates of interconversion of transporter conformers. Biochemistry 28: 8221–8227, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker GF, Basketter DA, Widdas WF. Asymmetry of the hexose transfer system in human erythrocytes. Experiments with non-transportable inhibitors. J Physiol 278: 377–388, 1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker GF, Widdas WF. The asymmetry of the facilitated transfer system for hexoses in human red cells and the simple kinetics of a two component model. J Physiol 231: 143–165, 1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker JO, Himmel ME. Separation of sugar anomers by aqueous chromatography on calcium- and lead-form ion-exchange columns. Application to anomeric analysis of enzyme reaction products. J Chromatogr 357: 161–181, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker PF, Carruthers A. Sugar transport in giant axons of Loligo. J Physiol 316: 481–502, 1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett JE, Holman GD, Munday KA. Structural requirements for binding to the sugar-transport system of the human erythrocyte. Biochem J 131: 211–221, 1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blodgett DM, Carruthers A. Quench-flow analysis reveals multiple phases of Glut1-mediated sugar transport. Biochemistry 44: 2650–2660, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blodgett DM, De Zutter JK, Levine KB, Karim P, Carruthers A. Structural basis of GLUT1 inhibition by cytoplasmic ATP. J Gen Physiol 130: 157–168, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carruthers A Anomalous asymmetric kinetics of human red cell hexose transfer: role of cytosolic adenosine 5′-triphosphate. Biochemistry 25: 3592–3602, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carruthers A Mechanisms for the facilitated diffusion of substrates across cell membranes. Biochemistry 30: 3898–3906, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carruthers A, Helgerson AL. Inhibitions of sugar transport produced by ligands binding at opposite sides of the membrane. Evidence for simultaneous occupation of the carrier by maltose and cytochalasin B. Biochemistry 30: 3907–3915, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carruthers A, Melchior DL. Asymmetric or symmetric? Cytosolic modulation of human erythrocyte hexose transfer. Biochim Biophys Acta 728: 254–266, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carruthers A, Melchior DL. Transport of α- and β-d-glucose by the intact human red cell. Biochemistry 24: 4244–4250, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charron FM, Blanchard MG, Lapointe JY. Intracellular hypertonicity is responsible for water flux associated with Na+/glucose cotransport. Biophys J 90: 3546–3554, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cloherty EK, Heard KS, Carruthers A. Human erythrocyte sugar transport is incompatible with available carrier models. Biochemistry 35: 10411–10421, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cloherty EK, Levine KB, Carruthers A. The red blood cell glucose transporter presents multiple, nucleotide-sensitive sugar exit sites. Biochemistry 40: 15549–15561, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cloherty EK, Levine KB, Graybill C, Carruthers A. Cooperative nucleotide binding to the human erythrocyte sugar transporter. Biochemistry 41: 12639–12651, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cloherty EK, Sultzman LA, Zottola RJ, Carruthers A. Net sugar transport is a multistep process. Evidence for cytosolic sugar binding sites in erythrocytes. Biochemistry 34: 15395–15406, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunningham P, Afzal-Ahmed I, Naftalin RJ. Docking studies show that d-glucose and quercetin slide through the transporter GLUT1. J Biol Chem 281: 5797–5803, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan YJ, Fukatsu H, Miwa I, Okuda J. Anomeric preference of glucose utilization in rat erythrocytes. Mol Cell Biochem 112: 23–28, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faust RG Monosaccharide penetration into human red blood cells by an altered diffusion mechanism. J Cell Comp Physiol 56: 103–121, 1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujii H, Miwa I, Okuda J. Anomeric preference of glucose phosphorylation and glycolysis in human erythrocytes. Biochem Int 13: 359–365, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Perez AI, Lopez-Beltran EA, Kluner P, Luque J, Ballesteros P, Cerdan S. Molecular crowding and viscosity as determinants of translational diffusion of metabolites in subcellular organelles. Arch Biochem Biophys 362: 329–338, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginsburg H Galactose transport in human erythrocytes. The transport mechanism is resolved into two simple asymmetric antiparallel carriers. Biochim Biophys Acta 506: 119–135, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goddette DW, Uberbacher EC, Bunick GJ, Frieden C. Formation of actin dimers as studied by small angle neutron scattering. J Biol Chem 261: 2605–2609, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gornicki A Changes in erythrocyte microrheology in patients with psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol 29: 67–70, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hakumaki JM, Pirttila TR, Kauppinen RA. Reduction in water and metabolite apparent diffusion coefficients during energy failure involves cation-dependent mechanisms. A proton nuclear magnetic resonance study of rat cortical brain slices. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 20: 405–411, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamill S, Cloherty EK, Carruthers A. The human erythrocyte sugar transporter presents two sugar import sites. Biochemistry 38: 16974–16983, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heard KS, Diguette M, Heard AC, Carruthers A. Membrane-bound glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and multiphasic erythrocyte sugar transport. Exp Physiol 83: 195–202, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heard KS, Fidyk N, Carruthers A. ATP-dependent substrate occlusion by the human erythrocyte sugar transporter. Biochemistry 39: 3005–3014, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helgerson AL, Carruthers A. Equilibrium ligand binding to the human erythrocyte sugar transporter. Evidence for two sugar-binding sites per carrier. J Biol Chem 262: 5464–5475, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helgerson AL, Carruthers A. Analysis of protein-mediated 3-O-methylglucose transport in rat erythrocytes: rejection of the alternating conformation carrier model for sugar transport. Biochemistry 28: 4580–4594, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isbell HS, Pigman W. Mutarotation of sugars in solution. II. Catalytic processes, isotope effects, reaction mechanisms, and biochemical aspects. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem 24: 13–65, 1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janoshazi A, Solomon AK. Initial steps of alpha- and beta-d-glucose binding to intact red cell membrane. J Membr Biol 132: 167–178, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jardetzky O Simple allosteric model for membrane pumps. Nature 211: 969–970, 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krupka RM, Deves R. Testing transport systems for competition between pairs of reversible inhibitors. J Biol Chem 255: 11870–11874, 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuchel PW, Chapman BE, Potts JR. Glucose transport in human erythrocytes measured using 13C NMR spin transfer. FEBS Lett 219: 5–10, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leitch JM, Carruthers A. ATP-dependent sugar transport complexity in human erythrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C974–C986, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lieb WR, Stein WD. New theory for glucose transport across membranes. Nat New Biol 230: 108–116, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lieb WR, Stein WD. Testing and characterizing the simple carrier. Biochim Biophys Acta 373: 178–196, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.London RE, Gabel SA. Fluorine-19 NMR studies of glucosyl fluoride transport in human erythrocytes. Biophys J 69: 1814–1818, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lowe AG, Walmsley AR. The kinetics of glucose transport in human red blood cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 857: 146–154, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malaisse-Lagae F, Malaisse WJ. Anomeric specificity of d-glucose phosphorylation and oxidation in human erythrocytes. Int J Biochem 19: 733–736, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malaisse-Lagae F, Sterling I, Sener A, Malaisse WJ. Anomeric specificity of d-glucose metabolism in human erythrocytes. Clin Chim Acta 172: 223–231, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malaisse WJ, Verbruggen I, Biesemans M, Willem R. Delayed interconversion of d-glucose anomers in D2O. Int J Mol Med 13: 855–857, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller DM The kinetics of selective biological transport. III. Erythrocyte-monosaccharide transport data. Biophys J 8: 1329–1338, 1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miwa I, Fujii H, Okuda J. Asymmetric transport of d-glucose anomers across the human erythrocyte membrane. Biochem Int 16: 111–117, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mueckler M, Caruso C, Baldwin SA, Panico M, Blench I, Morris HR, Allard WJ, Lienhard GE, Lodish HF. Sequence and structure of a human glucose transporter. Science 229: 941–945, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naftalin RJ, Rist RJ. 3-O-methyl-d-glucose transport in rat red cells: effects of heavy water. Biochim Biophys Acta 1064: 37–48, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naftalin RJ, Holman GD. Transport of sugars in human red cells. In: Membrane Transport in Red Cells, edited by Ellory JC and Lew VL. New York: Academic, 1977, p. 257–300.

- 53.Naftalin RJ, Smith PM, Roselaar SE. Evidence for non-uniform distribution of d-glucose within human red cells during net exit and counterflow. Biochim Biophys Acta 820: 235–249, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naftalin RJ Alternating carrier models of asymmetric glucose transport violate the energy conservation laws. Biophys J 95: 4300–4314, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rampal AL, Pinkofsky HB, Jung CY. Structure of cytochalasins and cytochalasin B binding sites in human erythrocyte membranes. Biochemistry 19: 679–683, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salas-Burgos A, Iserovich P, Zuniga F, Vera JC, Fischbarg J. Predicting the three-dimensional structure of the human facilitative glucose transporter glut1 by a novel evolutionary homology strategy: insights on the molecular mechanism of substrate migration, and binding sites for glucose and inhibitory molecules. Biophys J 87: 2990–2999, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salter MD, Nienhaus K, Nienhaus GU, Dewilde S, Moens L, Pesce A, Nardini M, Bolognesi M, Olson JS.The apolar channel in cerebratulus lacteus hemoglobin is the route for O2 entry and exit. J Biol Chem. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Samuel BU, Mohandas N, Harrison T, McManus H, Rosse W, Reid M, Haldar K. The role of cholesterol and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins of erythrocyte rafts in regulating raft protein content and malarial infection. J Biol Chem 276: 29319–29329, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sheetz MP, Painter RG, Singer SJ. Biological membranes as bilayer couples. III. Compensatory shape changes induced in membranes. J Cell Biol 70: 193–203, 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sheetz MP, Singer SJ. Biological membranes as bilayer couples. A molecular mechanism of drug-erythrocyte interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 71: 4457–4461, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheetz MP, Singer SJ. Equilibrium and kinetic effects of drugs on the shapes of human erythrocytes. J Cell Biol 70: 247–251, 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simpson IA, Carruthers A, Vannucci SJ. Supply and demand in cerebral energy metabolism: the role of nutrient transporters. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27: 1766–1791, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stein WD Transport and Diffusion Across Cell Membranes. New York: Academic, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Terada N, Ohno S. Dynamic morphology of erythrocytes revealed by cryofixation technique. Kaibogaku Zasshi 73: 587–593, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]