Abstract

Eye-head gaze pursuit–related activity was recorded in rostral portions of the nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis (rNRTP) in alert macaques. The head was unrestrained in the horizontal plane, and macaques were trained to pursue a moving target either with their head, with the eyes stationary in the orbits, or with their eyes, with their head voluntarily held stationary in space. Head-pursuit–related modulations in rNRTP activity were observed with some cells exhibiting increases in firing rate with increases in head-pursuit frequency. For many units, this head-pursuit response appeared to saturate at higher frequencies (>0.6 Hz). The response phase re:peak head-pursuit velocity formed a continuum, containing cells that could encode head-pursuit velocity and those encoding head-pursuit acceleration. The latter cells did not exhibit head position–related activity. Sensitivities were calculated with respect to peak head-pursuit velocity and averaged 1.8 spikes/s/deg/s. Of the cells that were tested for both head- and eye-pursuit–related activity, 86% exhibited responses to both head- and eye-pursuit and therefore carried a putative gaze-pursuit signal. For these gaze-pursuit units, the ratio of head to eye response sensitivities averaged ∼1.4. Pursuit eccentricity seemed to affect head-pursuit response amplitude even in the absence of a head position response per se. The results indicated that rNRTP is a strong candidate for the source of an active head-pursuit signal that projects to the cerebellum, specifically to the target-velocity and gaze-velocity Purkinje cells that have been observed in vermal lobules VI and VII.

INTRODUCTION

Proper visual function is dependent on the accurate pointing of the fovea toward visual objects of interest. Rotations of the eyeball are the common means of accomplishing this foveation. However, head movements often accompany eye movements when large gaze shifts are required as we navigate our visual environment. Although much is known about the neuronal mechanisms involved with rotating the eyeball, less is known about the control of head movements.

The numerous motor-related inputs to the nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis (NRTP) together with functions known to date indicate that NRTP could be involved with the coordinated control of eye-and-head motor behavior. Projections to NRTP include inputs from the frontal and supplementary eye fields and the premotor and motor cortices (Brodal 1980a; Giolli et al. 2001; Hartmann-von Monakow et al. 1981; Huerta et al. 1986; Künzle and Akert 1977; Leichnetz 1986; Leichnetz et al. 1984; Shook et al. 1990; Stanton et al. 1988). Both the frontal eye field and NRTP have been shown to be involved with the control of smooth pursuit eye movements (Gottlieb et al. 1993, 1994; Keating 1991; Lynch 1987; MacAvoy 1991; Ono et al. 2004; Suzuki et al. 1999b, 2003; Yamada et al. 1996). NRTP activities related to saccadic and vergence eye movements have been observed (Crandall and Keller 1985; Gamlin and Clarke 1995), as well as responses to passive rotation of an animal (Ono et al. 2004).

The premotor and motor cortical inputs suggested the possibility that NRTP might also be involved with controlling head movements and coordinating this behavior with ocular motor functions. Such control of coordinated behavior would be especially important during the tracking of moving targets with eye-and-head gaze pursuit movements. Furthermore, the presence of a pursuit head movement signal would implicate NRTP as a source of the putative gaze and target velocity signals observed in Purkinje cell activities of the floccular region and vermal lobules VI and VII (Lisberger and Fuchs 1978; Miles and Fuller 1975; Suzuki and Keller 1988a,b).

With the above in mind, the focus of attention in this study was on the neuronal responses in NRTP that were specifically associated with active head-pursuit movements. To dissociate head-pursuit and eye-pursuit responses, task performance required maximizing one behavior while minimizing the other. Thus head-pursuit was elicited with very minimal eye movements and eye-pursuit was elicited with minimal head movements. In this manner, activity that was related specifically to head-pursuit could be distinguished from eye-pursuit responses. The results indicated that a gaze pursuit signal, composed of an active head-pursuit plus smooth eye-pursuit signals, exists in NRTP.

METHODS

Preparation

The method for implanting special titanium inserts, prefabrication of the acrylic implant, and preparation of a nonhuman primate for behavioral experiments have been detailed in Betelak et al. (2001). This method has resulted in zero implant failures and provided an extremely well-anchored implant that could withstand the stresses imposed by a study using a horizontal head-unrestrained preparation. In brief, three macaques (2 Macaca nemestrina and 1 M. mulatta) were prepared by 1) implanting titanium flange fixtures for anchors, 2) waiting several months for bone growth into the outer threads of the flange fixtures, 3) implanting scleral eye coils and attaching a prefabricated acrylic skull cap, and 4) attaching a recording chamber. All procedures were completed under aseptic conditions and isoflurane gas anesthesia. The scleral eye coils were fabricated from Teflon-covered stainless steel wire and surgically implanted under the conjunctiva at the junctions of the eye muscle insertions of the right eye (Judge et al. 1980). A titanium chamber (17 mm diam) was attached to the skull with dental acrylic cement and centered at stereotaxic anterior 6.5 mm with a 20° off vertical angle in the coronal plane. Two small-diameter transverse, stainless steel cylinders were embedded in the prefabricated acrylic pedestal to allow attachment of the head movement apparatus. All sutured incisions were treated with antibiotic ointments. During recovery, buprenex was given for analgesia, and penicillin or cefazolin was administered for prophylaxis.

Before surgical preparation, the nonhuman primates were trained to enter a primate chair from their home cages. After recovery from the surgical procedures, the animals, on a daily basis, voluntarily entered the primate chair that was placed within the experimental setup. An apparatus that permitted head movements in the horizontal plane had an immovable component that was attached to the primate chair and a movable component to which an animal's head was secured via stainless steel locking screws that mated with the two small-diameter transverse cylinders embedded in the acrylic on top of the skull. Attached to the movable component was an axle that rotated within a flange bearing that minimized resistance to rotation while maintaining the axle in a vertical position. The movable head movement assembly weighed 1.2 kg. This mass was supported by a brass collar that was attached to the axle and rested on a needle-roller thrust bearing, which minimized the frictional resistance to rotation. Horizontal head rotations were mechanically limited to ±35°. When needed, a vest, customized for each animal, could be placed to limit excessive body rotations. After each daily experimental session, the animals were taken back to their home cages for the remainder of the day. The experimental and surgical protocols were approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with the policies of The American Physiological Society and the United States Public Health Service concerning the care and use of laboratory animals.

Recording

Tungsten microelectrodes insulated with Isonel-31 were lowered within and together with a 23-gauge stainless steel guide tube to a point 10 mm dorsal to the oculomotor (IIIrd) nucleus. A Kopf stepper-motor microdrive system was used to hydraulically drive the microelectrode out of the guide tube. The location of the IIIrd nucleus, with its characteristic eye movement-related activity, was first determined to establish a stereotaxic reference structure that aided the subsequent localization of NRTP. Tracks aimed at NRTP ran ventrolateral to the IIIrd nucleus.

Paradigms

The monkeys were trained with standard conditioning techniques to fixate and track small (0.25°) laser-generated spots of light that were back-projected onto a tangent screen and moved with an X,Y-mirror galvanometer system. The tangent screen was 90 × 90° and located about 60 cm in front of the monkeys in a dark room. A red laser spot was used for eye fixation, and a green laser spot was used to indicate the positions to which a monkey was required to point their heads. An Apple Macintosh G4 computer running LabView controlled the presentation of the visual targets, monitored behavior, and rewarded correct task performance. Liquid intake was controlled for 5 days each week and was freely available on weekends. During the experimental period, the extent of liquid intake was self-determined by the animals, who received performance-dependent liquid rewards until they were satiated. Reward delivery was contingent on head and eye positions being within small electronic “windows” surrounding the position of the green and red fixation spots, respectively. Window size was dependent on target speed and could usually be set for 2–4° after a training period of several months.

Eye and head positions were determined with the magnetic-field search-coil method (Robinson 1963) with a resolution of 0.25°. Eye and head positions were independently monitored using a phase-angle coil system with two phase detectors (CNC Engineering). Eye-in-orbit position was directly monitored by securing a reference coil to the head movement apparatus that was attached to the head. The use of this eye-reference coil that was stationary with respect to the orbit (skull) together with a phase-angle system yielded an eye position signal that was not affected by the eye coil translations, relative to the primate chair (and the animal's body), that accompanied horizontal head rotations. Head position was monitored separately with a search coil attached to and centered just below the axle. For this head position coil, a second reference coil was used that was fixed to the primate chair. Gaze position was calculated as the sum of the independently measured eye and head positions.

The goal was to dissociate head and eye signals during gaze pursuit movements. To this end, two tasks were used to maximize one signal while minimizing the other signal as schematized in Fig. 1A.

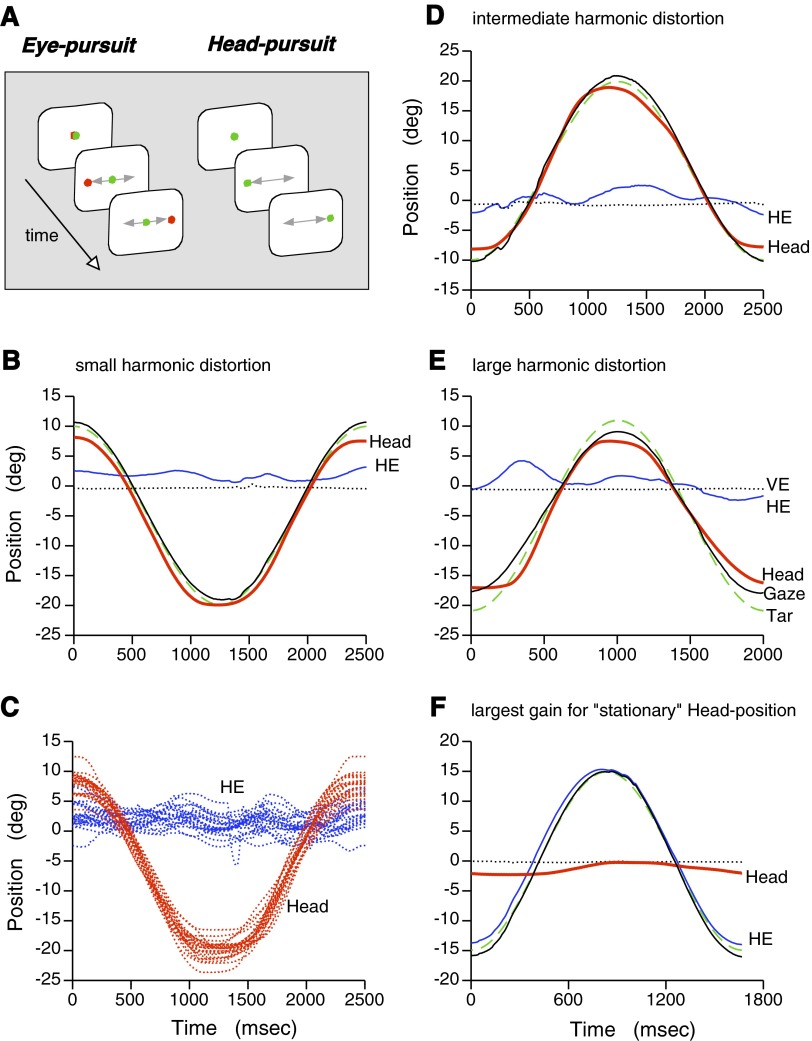

FIG. 1.

Quality of active head-pursuit movements. A: 2 tasks used to dissociate eye-pursuit activity and head-pursuit responses. For eye-pursuit, the animal was required to track a moving red target while voluntarily keeping its head (nose) directed toward a stationary green target. For head-pursuit, the green target became the moving target that the animal had to track with active head movements while maintaining the eyes stationary in the orbit. B: average position traces showing high gain and low distortion head-pursuit (red trace) with relatively small eye movements (blue trace). C: the per-trial head-pursuit movements yielding the average in B. D: average results with intermediate value for harmonic distortion of the head-pursuit behavior. E: average results with harmonic distortion toward the high end for head-pursuit. F: eye-pursuit with the largest harmonic distortion for stationary head position. For all panels: red traces, head position (Head); blue traces, horizontal eye position (HE); black traces, gaze position (Gaze), sum of head and horizontal eye positions; green dashed traces, target position (Tar); dotted traces, vertical eye position (VE). The trace labels in E apply to all panels even though only Head and HE traces were labeled in most panels.

HEAD-PURSUIT.

The monkeys were trained to pursue the green laser target with head movements while maintaining the eyes relatively stationary in the orbit. Because head and eye positions were monitored independently, electronic “windows” could be established around the target to regulate head-position and around zero-position in the orbit to minimize eye movements. Although not perfect, the monkeys were able to elicit high gain head-pursuit of the green target (Fig. 1, B–E) with very low gain eye movements. In this manner, dissociated head-pursuit neuronal activity could be maximized.

EYE-PURSUIT, STATIONARY HEAD.

Two laser spots were used with this task as illustrated in Fig. 1A (right). The animal was trained to direct its head toward a stationary green laser spot and its eyes toward a moving red laser spot. Thus the monkey voluntarily held its head stationary while eliciting smooth-pursuit eye movements. If the head was mechanically fixed, we found that the monkey attempted to move its head in addition to its eyes. This could be observed because movements of the head movement apparatus were prevented by a pinning mechanism that had a small amount of “play” that allowed an approximate ±0.25° rotation. When the head-position signal was greatly amplified, a periodic modulation in the position was observed that was in phase with the eye-pursuit movements. The interpretation of neuronal activity recorded with the head mechanically fixed would therefore be compromised by the possibility that any modulation could be caused by attempted head movements instead of or in addition to eye movements. The use of a head-related stationary (green) fixation spot explicitly directed the monkey to voluntarily keep its head stationary during eye-pursuit (example behavior shown in Fig. 1F). This more closely resembles natural primate behavior when we track moving objects of interests with our eye while (voluntarily) keeping our heads stationary with respect to our bodies. In this manner, eye-pursuit neuronal activity could be maximized and dissociated from an active head movement-related signal.

Recording and data analysis

Analog signals, filtered at 202 Hz (Frequency Devices, 8-pole Bessel), and unfiltered, discriminated neuronal pulses (Bak DIS-1) were sampled at 2 kHz per channel. Horizontal and vertical eye positions, horizontal head and target positions, the discriminated neuronal pulses, and timing pulses were stored on a magneto-optical disk (Pinnacle Micro REO-650) for later off-line analysis. Data were analyzed with a “Pentium” microcomputer using analytical software that was developed with the Forth-based ASYST (Keithley) or MatLab (MathWorks) programming environments. To gauge the quality of task performance, some behavioral data were subjected to discrete Fourier analysis to quantify harmonic distortion. Harmonic distortion was calculated as the square root of the sum of the squares of the Fourier amplitudes of the second through the eighth harmonics divided by the amplitude of the fundamental component. Neuronal activity represented in response histograms was fitted with a least-squares sinusoid for nonrectified portions of the response.

Histology

Electrolytic lesions (anodal constant current, 20 μA for 30 s) were made at selected NRTP sites. After 1–3 wk, the monkeys were deeply anesthetized and perfused rapidly through the left ventricle with 1 liter of buffered isotonic saline followed by a rapid perfusion of 2 liters and slow perfusion of 2 additional liters of buffered 10% formalin. The brain was blocked, frozen, and cut in the coronal plane in 40-μm sections. The resulting sections were stained with cresyl violet. The location of the electrolytic lesions verified that our recording sites were in rostral portions of NRTP as shown in previous studies (Suzuki et al. 1999b, 2003; Yamada et al. 1996).

RESULTS

The ability to dissociate active head-pursuit–related activity from activity related to eye movements in the same cell was dependent on obtaining head-pursuit of high gain and low distortion together with relatively minimal eye movements. That our training of the animals could result in such behavior is shown by the example of good head-pursuit in Fig. 1, B and C, where the harmonic distortion for head-pursuit averaged 4.5% and was 117.4% for eye position. The gain for head-pursuit averaged 0.98 and the gain for eye averaged 0.04. The large harmonic distortion and low gain for eye indicated that, on average, eye movements were a very small part of the eye-head gaze position trace (Fig. 1B, black “Gaze” trace). The average gain for eye-and-head gaze position was 1.003 with a harmonic distortion of 1.65%, suggesting that eye movements did contribute to improving overall gaze pursuit but their contribution was very small. The actual head-pursuit performance for 23 trials is shown in Fig. 1C.

For comparison, examples of active head-pursuit with harmonic distortions intermediate and toward the high end are shown in Fig. 1, D and E, respectively. The harmonic distortion for head-pursuit was 8.48% (eye, 68.73%) for the results shown in Fig. 1D and 12.29% (eye, 112.31%) for Fig. 1E. Overall, harmonic distortion for active head-pursuit movements averaged 8.14 ± 2.81% (SD) and ranged from 4.17 to 14.89%. The average head-pursuit gain was 0.95 (range: 0.80–1.21), whereas the gain for eye position was 0.13 (range: 0.01–0.24), supporting the conclusion that, on average, eye movements were fairly minimal during active head-pursuit movements. Conversely, during eye-pursuit, the animals were able to voluntarily keep their heads relatively stationary as shown in Fig. 1F, which presents the worst case (gain, 0.07) for average head position, which ideally should have had a gain of zero.

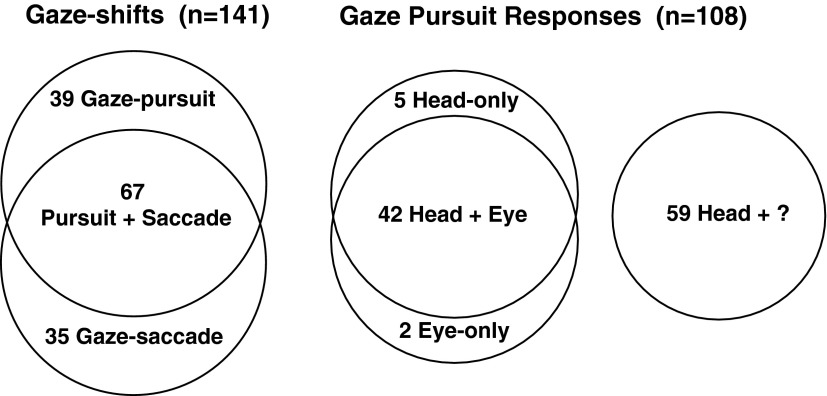

Active head movement–related modulations in NRTP activity were recorded for 141 units in three macaques (Fig. 2). Of these cells, the activities of 106 were modulated during head dominant gaze pursuit, and an overlapping subpopulation of 102 NRTP cells exhibited responses to head-and-eye gaze saccades. The overlap was comprised of 67 units that exhibited responses during both head dominant gaze pursuit and head-and-eye gaze saccades, whereas 39 units were responsive only during head-pursuit and not during rapid gaze shifts. Of the 106 NRTP cells whose activities were modulated during active head-pursuit movements, 47 were further studied during eye-pursuit, and most (42/47) were responsive during both active head-pursuit movements and also during smooth-pursuit eye movements. Active head-pursuit responses were observed in 59 cells for which isolation was lost before extensive tests could be conducted, including tests for the presence of eye movement-related activity. Because the head-pursuit task was used to search for responsive NRTP cells, the two eye-only units were undoubtedly under-representative but were included in the category of Gaze-Pursuit for completeness.

FIG. 2.

Venn diagrams showing the types of active head-pursuit–related activities recorded in NRTP. Gaze shifts include responses to head-pursuit movement (Gaze-Pursuit) and/or to relatively fast movements of the head and eyes (Gaze-Saccade). Gaze pursuit responses, a subset of the gaze shift cells that had active head-pursuit responses, plus 2 cells that exhibited smooth-pursuit eye movement responses but lacked responses to head-pursuit.

All 106 head-pursuit cells were recorded in the rostral portion of NRTP (rNRTP), wherein we have recorded smooth-pursuit eye movement responses, have shown that injection of ibotenic acid results in deficits in smooth-pursuit eye movements, and have shown that microstimulation evokes slow, pursuit-like eye movements (Suzuki et al. 1999b, 2003; Yamada et al. 1996). The focus of this study was on the 47 rNRTP cells that exhibited head movement–related modulations in activity during gaze pursuit and were tested for the presence of eye-pursuit responses.

Active head-pursuit movement cells

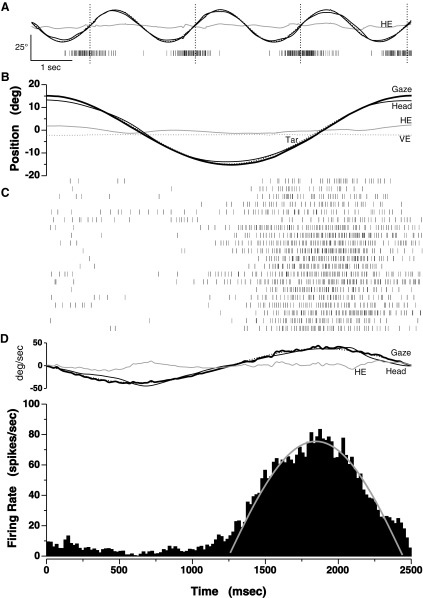

The peak responses of some rNRTP cells appeared to encode the velocity of head-pursuit movements as exemplified by the excerpt of recorded activity shown in Fig. 3A. The associated unit responses, indicated by the tick-marks in Fig. 3A, were in phase with ipsiversive (rightward) head-pursuit (vertical dotted lines). The average eye-and-head behavior and per cycle responses are shown in Fig. 3, B and C. Head-pursuit was fairly accurate with an average gain of 0.94 and a harmonic distortion of 5.2%. In contrast, eye position gain averaged only 0.08, indicating that the eyes were fairly stationary in the orbit.

FIG. 3.

Head-velocity pursuit responses of a cell in rostral portions of the nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis (rNRTP). A: several cycles of head-pursuit and the associated neuronal responses. Each tick-mark indicates the occurrence of an action potential. Dotted line, sinusoidal target motion of 0.4 Hz ± 15°. Thick line, gaze trace; medium-thick line, head position; thin line, horizontal eye position; vertical dotted lines, occurrences of peak ipsiversive head-pursuit velocity. B: average gaze (thick line), head (medium-thick line), horizontal eye (HE, thin line), and vertical eye positions (VE, dotted line) for 20 cycles of pursuit. C: raster of per-cycle neuronal responses indicated by tick-marks. D: average velocity traces and histogram indicating average response over 20 cycles. Gray curve, least-squares sinusoidal fit to the nonrectified portion of histogram. Time scale at bottom applies to B–D. The convention in this and all subsequent figures is positive position values indicate right or up positions.

The neuronal responses were consistent and clearly present on a cycle-to-cycle basis as is evident in the raster presentation in Fig. 3C. The average response histogram shown in Fig. 3D indicated that the average peak response of this rNRTP unit was approximately in phase with peak head-pursuit velocity, which occurred at 1,875 ms in Fig. 3D. The gray line indicates the least-squares fit to the histogram. Because head-pursuit lagged the target by 1.03° and the neuronal response led target velocity by 4.04°, the average peak response led peak head-pursuit velocity to the right by 5.07°. The average peak firing rate determined by the least-squares fit was 75.4 spikes/s. Average peak head velocity was ∼38°/s, equivalent to peak target velocity. Thus the sensitivity of this unit to head velocity was ∼2.0 spikes/s/°/s.

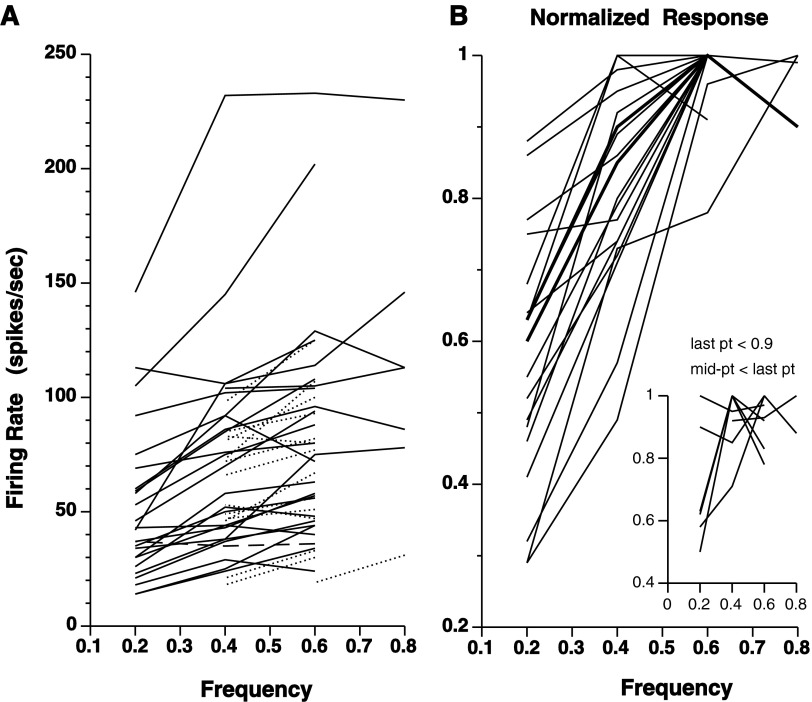

The relationship of neuronal responsiveness to the periodic frequency of head-pursuit was studied in 40 units for which responses at two or more different frequencies could be tested (Fig. 4). In most of these units (37/40), firing rate increased with increases in head-pursuit frequency over at least part of the frequency range tested. Frequency was plotted on the abscissa rather than speed because the phase distribution (Fig. 6) suggested a continuum rather than a simple dichotomy between velocity and acceleration encoding neuronal responses. That said, to reference the responses to a parameter for sensitivity calculations, peak head-pursuit velocity was used to derive a sensitivity for velocity. For 18 units that showed an increase in firing rate over three or more frequencies, the slope of the linear regression line, and thus the sensitivity re:velocity, averaged 1.2 ± 0.7 (SD) spikes/s/°/s (1.0 median). The responsiveness of one unit seemed to be independent of head-pursuit frequency (Fig. 4A, dashed line).

FIG. 4.

rNRTP head-pursuit responses as a function of frequency. A: the responses of 40 cells for a range of head-pursuit frequencies. Solid curves, results of 26 units that could be tested at ≥3 frequencies; dotted curves, results of 14 units that could be tested at only 2 frequencies; dashed curve, 1 unit without a relationship to frequency. B: averaged normalized responses. For each unit in A, the firing rates were calculated as fractions of the peak firing rate that was given a value of 1. The resultant normalized responses were averaged for each frequency yielding a representation of the rNRTP head-velocity pursuit response. For clarity, the plots were separated between those whose last data point was ≥0.9 from those (inset) with a final data value of <0.9 or with V-shaped plots.

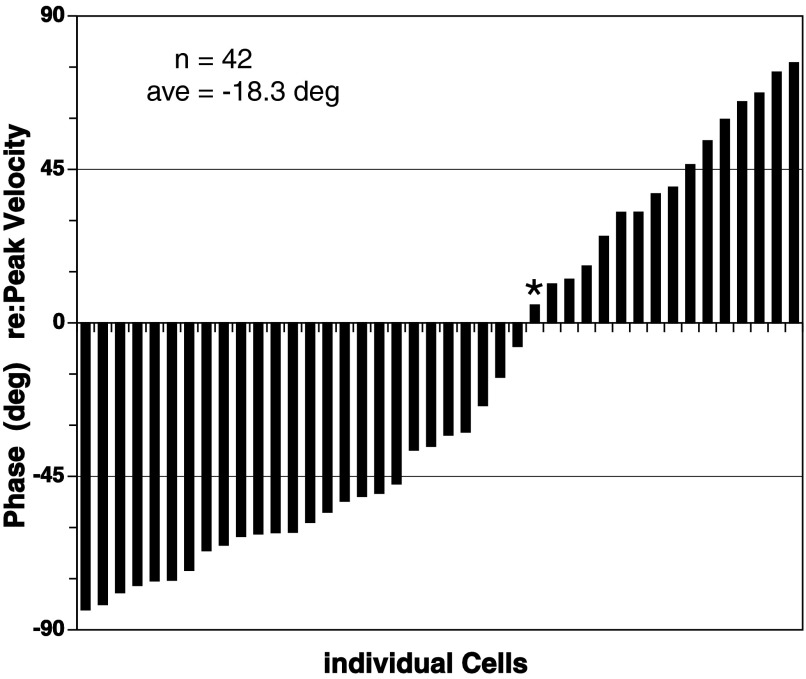

FIG. 6.

Phase distribution of head-pursuit responses re:peak head velocity. For each cell, response phases were plotted for head-pursuit at 0.4 Hz ±15°. Positive phase values indicated phase leads. *Response phase for the unit data shown in Fig. 3.

The percent change in response amplitude with increasing head-pursuit frequency was more easily seen when the data were normalized to the maximum response amplitude observed for each unit (Fig. 4B). Thus the increase in response amplitude was on the order of 10–60% when comparing the smallest and largest responses for a given cell. Because most of the units were not tested above 0.6 Hz, one can only conclude from Fig. 4B that firing rate increased with increased head-pursuit velocity at least ≤56.5°/s (peak velocity at 0.6 Hz, 15° amplitude). The limited data for higher velocities suggested that the responses might have saturated.

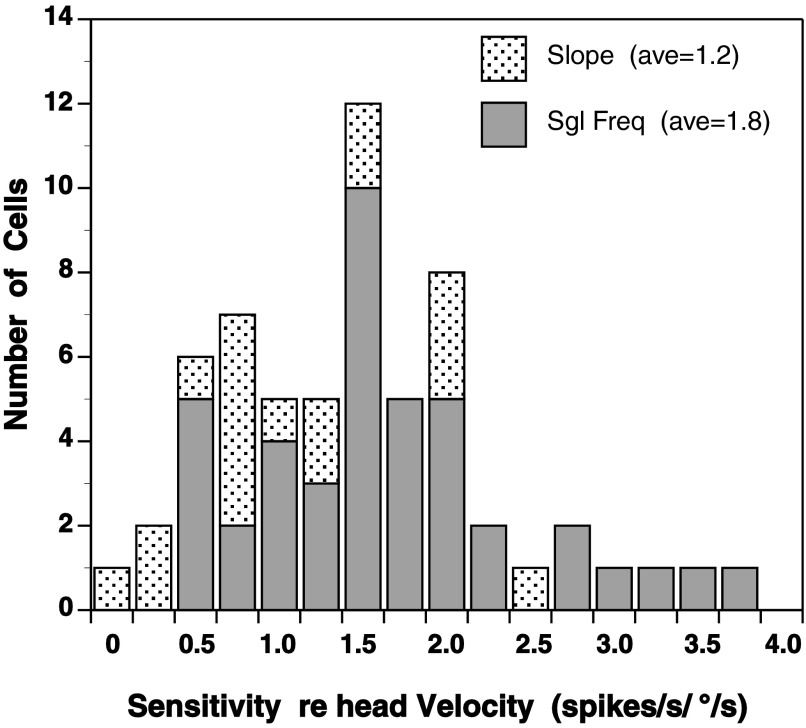

Active head-pursuit was commonly tested at 0.4 Hz ± 15° (i.e., the setting for the search stimulus). Because more data were collected with this setting than at other frequencies, a single frequency-based sensitivity for velocity was calculated and is shown in Fig. 5 as the “Sgl Freq” bar graph. Sensitivity for velocity of head-pursuit calculated in this manner for 42 cells averaged 1.8 ± 0.8 spikes/s/°/s (1.7 median). Also shown in Fig. 5 are the sensitivities calculated from the slopes of the firing rate versus velocity function for the 18 cells mentioned above (Fig. 5, Slope). Sensitivities obtained from these slopes averaged 1.2 spikes/s/°/s). Single frequency-based sensitivities ranged from 0.59 to 3.85 spikes/s/°/s. Slope-based sensitivities ranged from 0.19 to 2.55 spikes/s/°/s.

FIG. 5.

Sensitivity of rNRTP head-pursuit responses to velocity. Slope (light hatching), sensitivities determined from the slope of firing rate vs. peak velocity of head-pursuit plots; Sgl Freq (dark hatching), sensitivities determined as the ratio of peak response firing rate to 38°/s, the peak velocity of 0.4 Hz ± 15° head-pursuit movements.

Phase distribution of head-pursuit cells

The distribution of phase shifts of the neuronal responses re: velocity of head-pursuit appeared to form a continuum as shown in Fig. 6. In Fig. 6, the data were for responses observed at 0.4 Hz in the 42 cells exhibiting both head-pursuit and eye-pursuit modulations in activity. On the one hand, there were units that seemed to encode peak head-pursuit velocity as shown in Fig. 3. On the other hand, the responses of some cells were approximately in phase with peak acceleration as seen in Fig. 7. Phase re:peak head-pursuit velocity averaged −18.3 ± 51.7° (−34.5° median) and ranged from a lag of −84.1° to a lead of 76.3°.

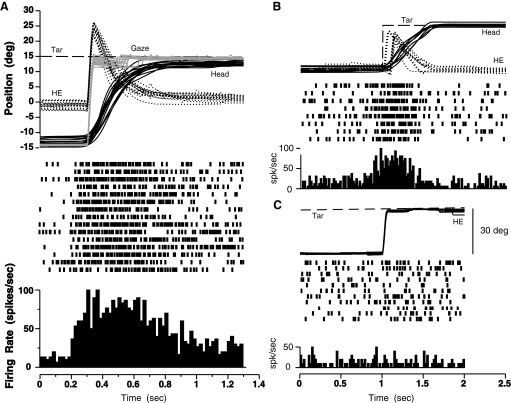

FIG. 7.

Responses of head-plus-eye pursuit neuron. A: top: activity recorded over 3 trials of active head-pursuit movements. Each tick-mark indicates the occurrence of an action potential. Eye position (dashed trace) remained fairly stationary in the orbit. Head position (solid trace) closely matched target position (dotted trace). Target motion was sinusoidal at 0.6 Hz ± 15°. Middle: average head and eye position for 12 cycles of head-pursuit and corresponding average velocity traces. Gaze (thick curve) was the sum of the average head and horizontal eye (HE, dashed curve) position traces and nearly coincident with target position (Tar, dotted trace). VE (thin curve), vertical eye position. Velocity traces analogously labeled. Bottom: neuronal response histogram averaged over 12 cycles of head-pursuit. B: analogous panel sequence for eye-pursuit movements with line representations the same as in A. Head position-in-space was voluntarily held stationary. The histogram of neuronal activity was averaged over 10 cycles of eye-pursuit movements. Time scale at bottom, in radians, also applies to the middle panels.

Although the distribution appeared to form a continuum, the distribution was not symmetrical around the peak velocity and acceleration phases: 0 and ±90°, respectively. The phase shifts between −45 and 45° numbered 16, whereas 26 were in the ranges −45 to −90° and 45–90°. If one considers the phase shifts within a 90° band centered at peak velocity (zero), 38% of the unit responses fell in this velocity-centered band. Similarly, 62% fell within a peak acceleration band. Thus, although the distribution forms a continuum, there seemed to be a tendency toward responses within 45° of peak acceleration of head-pursuit. The occurrence of peak neuronal responses near peak head-pursuit acceleration was not caused by head-position responses, because there was an absence of any head (or eye) position–related responses when the head (or eye) was directed toward stationary, eccentric fixation positions.

Head-pursuit plus eye-pursuit cells

Some rNRTP cells exhibited modulations in their activities during both head-pursuit and eye-pursuit movements as shown in Fig. 7. Peak activity in this cell was observed near the time of the ipsi-to-contraversive (rightward-to-leftward) turnabout point for both active head-pursuit (Fig. 7A) and for smooth-pursuit eye movements (Fig. 7B). As noted above, no position-related responses were observed when head (or eye) was directed toward stationary, eccentric fixation positions. For head-pursuit, eye position was fairly stable, especially near the peak in firing rate (Fig. 7A, dashed lines). Similarly, for eye-pursuit, head position was kept nearly stationary (Fig. 7B, medium-thick lines). The average peak responses were 115.0 spikes/s for head-pursuit and 96.3 spikes/s for eye-pursuit. Peak rightward head-pursuit velocity was 56°/s, resulting in a sensitivity, at this one speed, of 2.1 spikes/s/°/s. Similarly, for eye-pursuit, the sensitivity was 1.7 spikes/s/°/s. The ratio of response sensitivities to head- and eye-pursuit was 1.2.

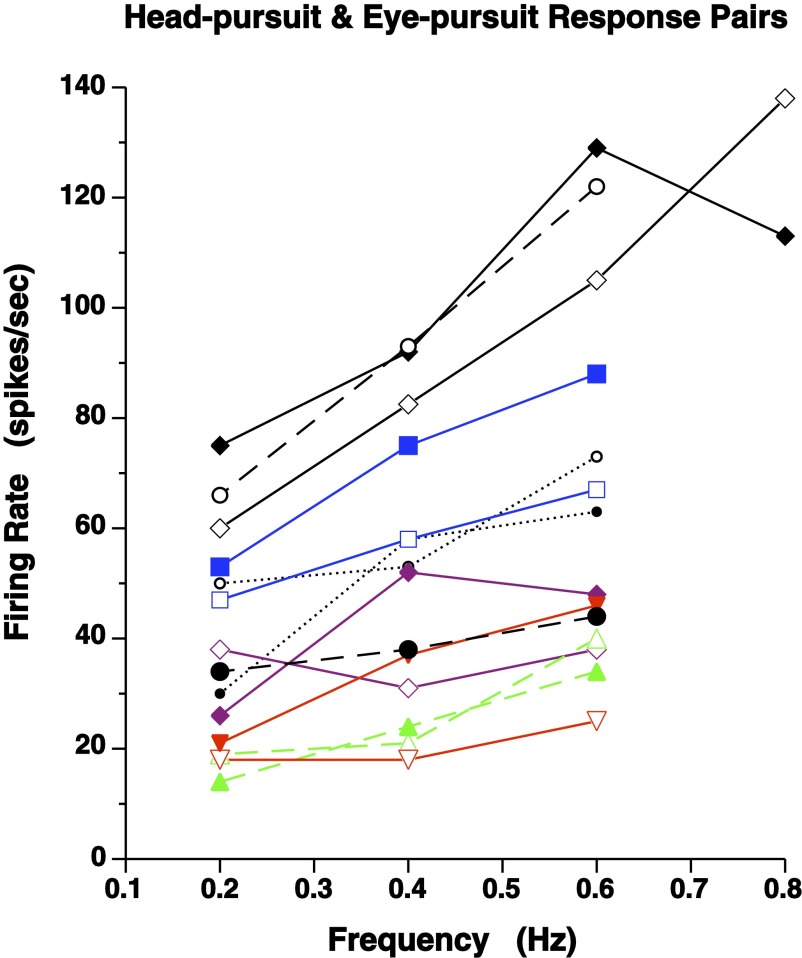

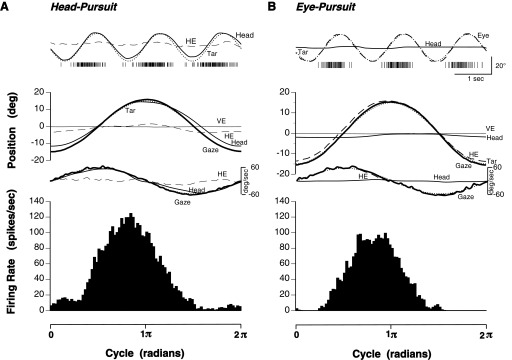

Responses to both head-pursuit and eye-pursuit could be studied over a range of frequencies in seven cells, and the results are shown in Fig. 8. To facilitate comparison, head- and eye-pursuit responses were plotted as paired curves with equivalent symbol and line types. With one exception (open diamond, dashed curves), for each pair of head-pursuit and eye-pursuit curves, firing rate increased with increases in pursuit speed.

FIG. 8.

Head- and eye-pursuit responses as a function of pursuit frequency. Seven paired graphs of responses for head-pursuit (filled symbols), with eye nearly stationary in orbit, and for eye-pursuit (open symbols), with head voluntarily held stationary. Each pair, indicated by equivalent color, symbol, and line types, applied to the same rNRTP cell. Solid lines denote larger overall response for head-pursuit than for eye-pursuit. Dashed and dotted lines indicate larger overall response for eye-pursuit than head-pursuit.

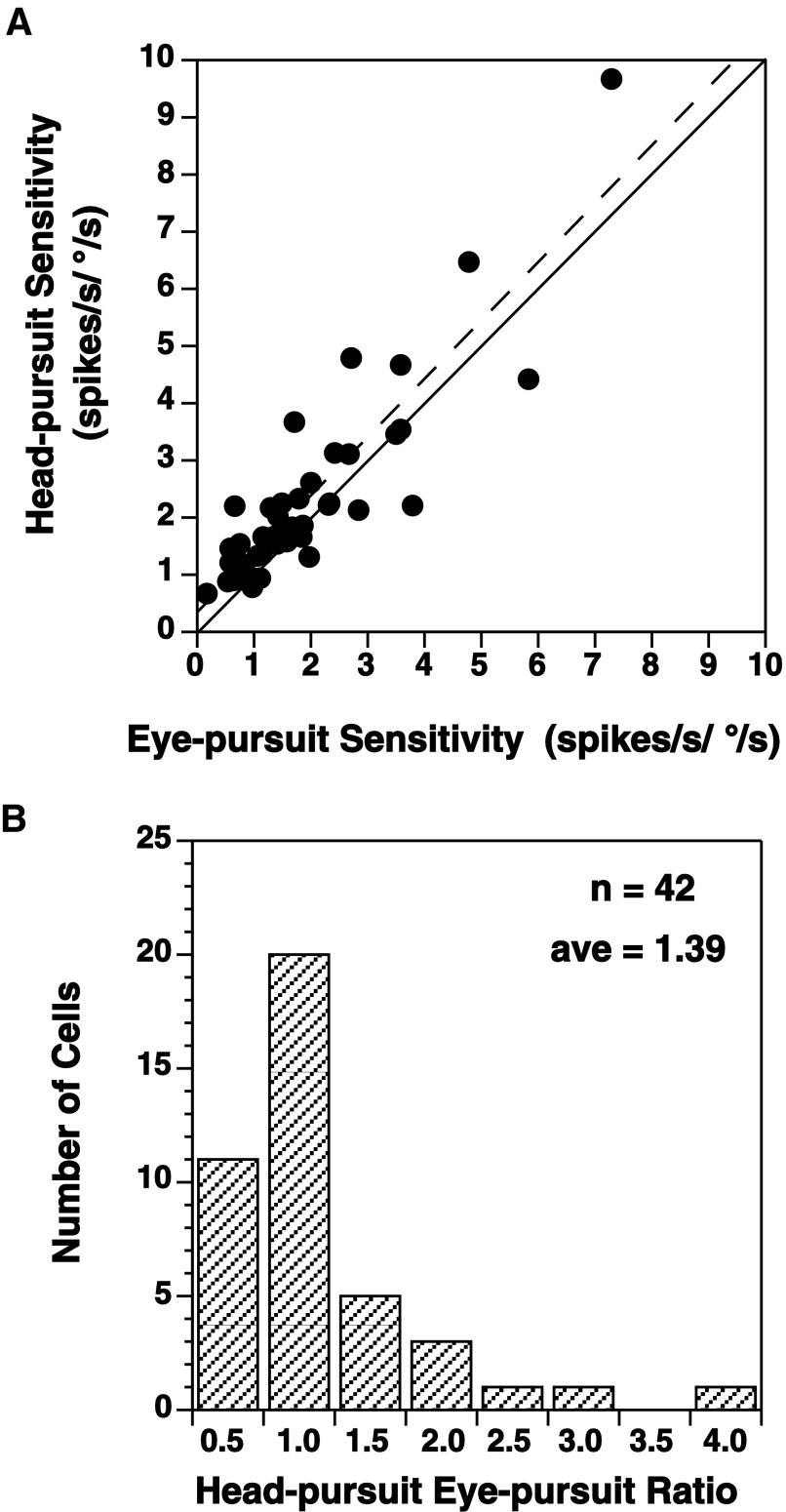

For 42 cells, the responses to both head- and eye-pursuit could be tested at the same frequency. For comparison, the sensitivities to head-pursuit were plotted against the sensitivity to eye-pursuit for each unit in Fig. 9A. Two thirds (28/42) of the points were above the equivalent sensitivities (solid) line. This was reflected in the nonzero, positive intercept of the regression (dashed) line through the data. The ratio of head-pursuit sensitivity to eye-pursuit sensitivity was calculated, and the results are presented in Fig. 9B. The ratio averaged 1.39 ± 0.67 (1.28 median) and ranged from 0.58 to 4.00.

FIG. 9.

Comparison of head-pursuit and eye-pursuit responses. A: for a given cell, response sensitivity to head-pursuit was plotted as a function of eye-pursuit sensitivity. Solid line indicates equivalent response sensitivities. Dashed line, regression line through data points. B: distribution of ratios of head-pursuit sensitivity to eye-pursuit sensitivity. Each bin contains ratio values that ranged from the labeled value to 0.01 less than the value of the next bin (e.g., bin 1.0 enumerates ratios from 1.00 to 1.49).

Direction selectivity

Rostral NRTP responses to both ipsiversive and contraversive head-pursuit were observed. Among the 42 cells that exhibited responses to both head- and eye-pursuit movements, 13 showed a direction preference for ipsiversive head-pursuit, whereas 29 were selective for contraversive head-pursuit. For an additional 59 units responsive to head-pursuit movements, directional preference could be qualitatively determined even though not enough data were collected to characterize phase, response sensitivities, or presence of an eye-pursuit response. The response preferences for these cells were ipsiversive for 37 cells and contraversive for 22 cells. Thus in total, there were 50 cells that exhibited head-pursuit responses with an ipsiversive preference and 51 units with a contraversive preference. Whether head-plus-eye pursuit units represented a different distribution favoring contraversive pursuit directions or were just undersampled remains to be determined.

Head-position effects

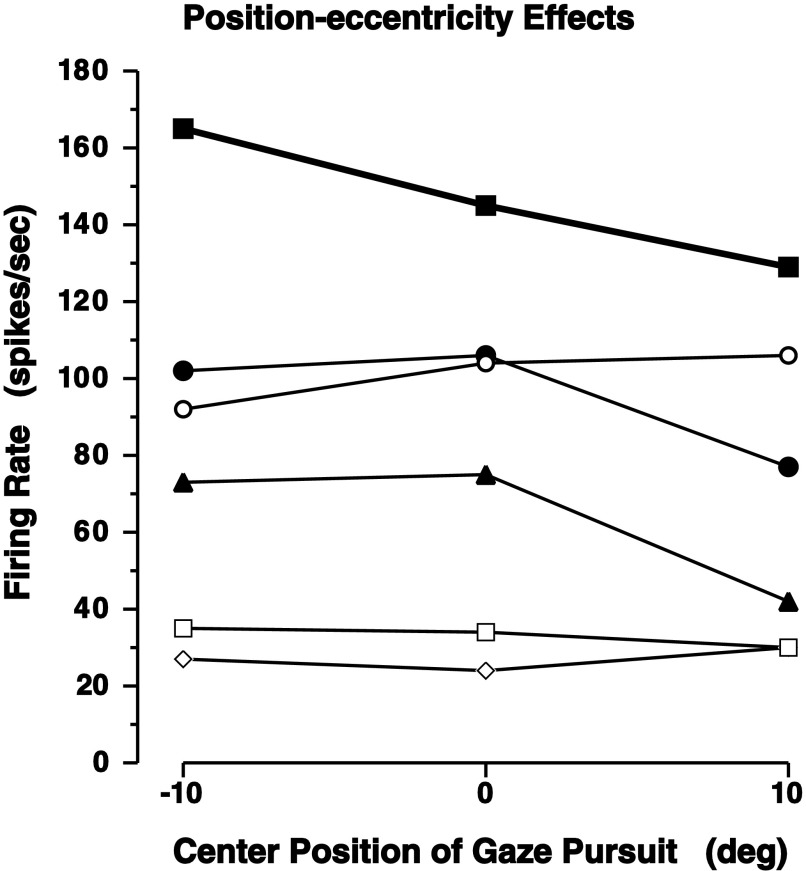

The effects of head position on the gaze pursuit responses was determined by centering the target motion at left or right 10° in addition to screen center. The motivation for this test was the observation of initial eye position effects on the responses of rNRTP units during head-restrained smooth-pursuit eye movements and on the velocity of pursuit-like slow eye movements evoked with microstimulation within rNRTP (Suzuki et al. 2003; Yamada et al. 1996). The eye position effects on eye-pursuit were observed even though no eye position responses to stationary fixation points were observed in the same cells (Suzuki et al. 2003). Analogous to the eye-pursuit study, 0.4 Hz ± 15° head-pursuit was centered at left 10°, center, and right 10°. Thus for pursuit centered at left 10°, the target moved from right 5° to left 25°. Under these conditions, the head-pursuit behavior was approximately the same, but with eccentric head position offsets, and eye position within the orbit was near 0°. Although we could not study head position effects in as much detail as the eye position effects on eye-pursuit responses, the results were suggestive and included for consistency with other studies. In this study, a position effect was suggested for three units presented in Fig. 10 with filled symbols. For the remaining three units, the center position of gaze pursuit seemed to have little (open circles) or no effect on responsiveness (open squares and diamonds). None of these units exhibited a head position per se, which was tested by requiring stationary head position directed at different eccentric target locations.

FIG. 10.

Effects of eccentricity on head-pursuit response. The center of the periodic target motion was placed at left 10°, center (0°), and right 10°. Head-pursuit gain was approximately the same for each position, but with an overall shift of the center of the pursuit movement to the left or right for eccentrically centered target motions. In all cases, head-pursuit was for sinusoidal target motions of 0.4 Hz ± 15°. Solid symbols, unit responses that appeared to exhibit some effect of head position; open symbols, units that had little or no head position effect. All of these rNRTPs did not encode head position when tested with head fixation of stationary targets.

Gaze saccade responses

Responses during rapid gaze shifts or “gaze-saccades” are shown in Fig. 11 for completeness. These responses were not analyzed in detail, because the focus of this study was on the gaze-pursuit–related responses. The recording location in rNRTP of the cells that showed gaze-pursuit and gaze-saccade responses did not differ from the location of cells exhibiting only gaze-pursuit responses. The gaze-saccade response shown in Fig. 11A was for the same unit whose gaze-pursuit response was shown in Fig. 3. Note that the duration of the response is relatively prolonged and extends beyond the end of the major step change in gaze position. This observation suggests that the response was related to the rapid head movement rather than the shorter duration saccadic eye movement. For this cell, tests for responses to eye saccades were not conducted. Shown in Fig. 11B are the gaze-saccade responses for a different cell that was tested for a response to eye saccades. There appeared to be no response to eye saccades as seen in Fig. 11C. Exactly what parameter of the head movement was encoded in the neuronal responses awaits further study.

FIG. 11.

Gaze saccade–related responses for 2 cells that also exhibited head-pursuit responses. A: activity during rapid gaze shifts for the same cell whose head-pursuit–related responses were shown in Fig. 3. Position traces and neuronal responses aligned to onset of gaze shift. Solid black line, head position; solid gray line, gaze position; dotted line, HE, horizontal eye position in the orbit; dashed line, Tar, final target position for target jump from left 15° to right 15°. B and C: neuronal activity for a different cell recorded for rapid gaze shifts and eye saccades to eccentric targets. Traces and neuronal responses aligned to target jump in B and to onset of saccadic eye movement in C. Target jump from center to right 30°.

DISCUSSION

The modulations in rNRTP activity observed during voluntary head-pursuit movements offered a relatively direct measure of the sensitivity of these cells to head movement. Because eye movements were minimal (Fig. 1), responses to passive, en bloc rotation did not have to be used to estimate a sensitivity to head movements. The observation of both eye- and head-pursuit responses on the same cell implicated the existence of an active gaze-pursuit signal in rNRTP. This observation complements those of Ono et al. (2004), who used passive rotations of the head to show that passive gaze velocity and gaze acceleration activities exist in rNRTP.

Head-pursuit responses

The majority (86%, 42/47) of the cells that were tested for responses to active head-pursuit and to eye-pursuit were responsive to both types of gaze pursuit (Fig. 2). Because the search for responsive units was conducted while the monkey elicited active head-pursuit, the results could have undersampled cells that responded only during eye-pursuit. In other words, although the majority of cells that responded to head-pursuit also responded to eye-pursuit, no conclusions can be drawn concerning whether most eye-pursuit cells also had a head-pursuit signal. With the full definition of gaze, as head-plus-eye movements, one can conclude that most head-pursuit cells were head-plus-eye and thus gaze-pursuit cells (42/47). A small minority exhibited responses only to head-pursuit (5/47) and lacked eye movement–related responses.

The modulation in rNRTP activity during active head-pursuit increased with increases in the frequency of sinusoidal pursuit (Fig. 4). This was true even for units whose response peak was near that of peak head-pursuit acceleration, indicating that these responses were not signaling head position. A saturation in the response to head-pursuit appeared to exist at ∼0.6 Hz that is analogous to the frequency near which human head-pursuit gain drops off (Barnes and Lawson 1989; Collins and Barnes 1999).

The temporal characteristics of rNRTP responses to active head-pursuit indicated a continuum of phase re:peak head velocity from cells that could encode velocity to those that could encode acceleration (Fig. 6). This is in contrast to the results, obtained with passive head movements, of Ono et al. (2004), who concluded that there were discrete subpopulations of cells that respectively encoded either head velocity or head acceleration. Whether this difference is reflective of the study of active versus passive head movements is not known. Regardless of this difference, a point to note is that our results do indicate that some rNRTP cells could encode active head-pursuit velocity and some could encode active head-pursuit acceleration, with the latter possibly being more common (the opposite observation from Ono et al. 2004).

Rather than view the responses as a dichotomy of signal types, viewing them as a continuum of temporally optimized responses that ensure the accuracy of changes in head velocity and the maintenance of head-pursuit velocity may be the functionally more pertinent consideration. The existence of the observed phase continuum in head-pursuit responses could complement head velocity responses to help counter inertia-related delays in changing head-pursuit speed and/or direction. Further study of these head-pursuit units under conditions of head-pursuit initiation would be useful in shedding more light on these issues.

The direction selectivities of the head-plus-eye pursuit units were about equally divided: 51 with contraversive and 50 with ipsiversive directional preference. This is comparable to the 56% contraversive and 44% ipsiversive directional preference of horizontal eye-pursuit unit responses previously studied in our laboratory (Suzuki et al. 2003). Ono et al. (2004) did not indicate the percentage of rNRTP units they observed with ipsiversive and contraversive direction preferences. Specific examples that they presented suggest that the eye-pursuit responses of most or all of the cells had an ipsiversive direction preference. Thus, although the degree to which our population of cells overlaps that recorded by Ono et al. (2004) is unclear, it seems that we observed more contraversive responses.

In our 2003 study of eye-pursuit responses (head restrained), the observed direction preferences included all of the eight directions tested. For this study, unrestrained head movements were limited to the horizontal plane. For consistency, elicited eye-pursuit was also constrained to the horizontal plane. Thus it is not known if there are units that carry an active head-pursuit response for pursuit in nonhorizontal planes. Our presumption is that such units exist to complement those eye-pursuit responses already observed for pursuit in nonhorizontal planes (Suzuki et al. 2003). Concerning the distribution of cells with head-plus-eye pursuit responses versus those with only an eye-pursuit response, as noted above, the latter type were probably undersampled, because we searched for pertinent responses with the active head-pursuit task.

Head-pursuit responses: what is being signaled?

Implicit in the conclusion that an active gaze-pursuit signal exists in rNRTP is the presumption that the modulations in rNRTP activity during head-pursuit were motor in nature. However, the cause of these modulations could have arisen from one of three possible sources: 1) a vestibular signal, 2) an eye-pursuit signal used to keep the eyes fairly stationary in the orbit during head-pursuit, or 3) an active head-pursuit signal that was a corollary of a head-pursuit motor command destined for the cerebellum. The first possibility would result from head movement–related activity flowing upstream from the vestibular nuclei. To our knowledge, there are no clearly defined pathways that would mediate a vestibular input to rNRTP, forcing one to speculate on indirect routing of vestibular signals via cortical structures known to project to NRTP (e.g., Giolli et al. 2001). The interpretation of head-pursuit–related modulations in rNRTP activity as an eye-pursuit signal that maintains stationary eye position in the orbit is plausible, but one that the following paragraph will argue against.

The second possibility assumes that, during active head-pursuit, the vestibulo-ocular reflexive (VOR) is functionally intact and driving the eyes in a direction opposite to the head movement. Thus to maintain the eyes stationary in the orbit, eye-pursuit movements would have to be elicited to negate the VOR. Although early studies suggested that the VOR is unaffected during gaze shifts (Bizzi et al. 1971; Dichgans et al. 1973; Morasso et al. 1973), more recent studies implicate a decrease in VOR strength during gaze shifts (Cullen et al. 2004; Guitton and Volle 1987; Laurutis and Robinson 1986; Pélisson et al. 1988; Tabak et al. 1996; Tomlinson 1990). Differences between these studies and the nature of the VOR attenuation have been nicely reviewed by Cullen et al. (2004). The notable point here is that, regardless of the degree of reported attenuation of VOR during gaze shifts, decreased VOR functionality has been observed by multiple investigators. The results of these behavioral studies have been complemented by the finding of suppression, during gaze shifts, of the head velocity responses of VOR-mediating, position-vestibular-pause (PVP) neurons in the vestibular nuclei (McCrea and Gdowski 2003; Roy and Cullen 2002). This suppression of head velocity–related PVP responses was greater for rapid gaze shifts than for gaze pursuit. However, the combined eye-head gaze pursuit was predominantly eye-pursuit in nature (Roy and Cullen 2002), leaving open the possibility that Roy and Cullen would have observed just as great a reduction in PVP head velocity responses for gaze pursuit as for rapid gaze shifts if their animals had elicited the larger head-pursuit movements used in this study. This would be consistent with the behavioral starting point that VOR eye movements are “counterproductive” during gaze pursuit movements where the goal is to foveate moving objects of interest during combined eye-head pursuit movements. The implication is that the larger the head movement, the larger the counterproductive effect of VOR eye movements and the larger the need to attenuate the VOR. While acknowledging that the evidence for VOR attenuation is not definitive, a reduced VOR drive during gaze movements would be consistent with the third possibility noted above and permit the interpretation of our observed rNRTP head-pursuit responses as being related to the head movements per se and not a result of engaging eye-pursuit to maintain stable position in the orbit.

The results presented in Figs. 2 and 11 suggest that at least some rNRTP cell responses could be explained in terms of head movements, because eye movement–related activities were not observed. To be sure, a contribution of VOR eye movement–related activities could not be ruled out for gaze saccade responses such as those shown in Fig. 11; however, the responses significantly led the VOR (Fig. 11, A and B) and seem to more closely parallel the head movement in duration. The responsiveness of some units to both gaze pursuit and gaze saccades (Fig. 2) and the lack of response to saccadic eye movements in some cells (Fig. 11C) suggest that head movement may be the movement of import with respect to the responses of the rNRTP in our recorded population. Addressing this suggestion awaits future studies.

In a separate study of fastigial nucleus activity using the same head-pursuit paradigm, but with additional vestibular and VOR testing, the amplitude of some active head-pursuit responses exceeded the response amplitudes observed during suppression of VOR eye movements and during eye-pursuit movements (Suzuki et al. 2002). The greater head-pursuit response compared with VOR-suppress or eye-pursuit responses was interpreted as the result of a nonsensory, active head-pursuit movement signal in fastigial nuclei. Presumably, the active head-pursuit responses observed in fastigial nuclei were caused by inputs from the rNRTP cells reported in this study. Although a definitive conclusion cannot be made, we believe that some of the head-pursuit responses that we observed in rNRTP cells were caused by active head movement–related motor inputs.

Head-plus-eye-pursuit responses

A key finding is that some cells in rNRTP carry both a head-pursuit signal and an eye-pursuit signal (Fig. 7). For a given unit, increases in firing rate with increases in pursuit frequency were qualitatively similar for the head-pursuit and eye-pursuit responses (Fig. 8). On average, the sensitivity of responses to head-pursuit seemed to be 39% larger than the sensitivity to eye-pursuit responses (Fig. 9). Although a portion of the greater ratio of head-pursuit to eye-pursuit sensitivity could be caused by residual eye movements during active head-pursuit movements, the contribution of these residual eye movements to the overall gain of gaze-pursuit was very small (Fig. 1) and thus cannot be an explanation for the entirety of the, on average, 39% higher head-pursuit sensitivity.

Active head-pursuit responses have been studied in the frontal eye field (FEF) (Fukushima et al. 2005), the floccular region of the cerebellum (Belton and McCrea 2000), and the medial vestibular nucleus (Roy and Cullen 2001–2003). Fukushima et al. (2005) found that 62% of the FEF cells exhibited responses to head-pursuit and eye-pursuit that seemed to make them similar to the neurons that we recorded in rNRTP. Many of these cells were not responsive to passive whole body rotation. For comparison, it would have been ideal if we could have studied responses to passive whole body rotation. Unfortunately, we did not have a vestibular turntable at the time this rNRTP study was conducted.

Fukushima et al. (2005) also reported that 25% of their FEF cells resembled gaze velocity cells as defined by their responses to passive en bloc rotations and to eye-pursuit (Lisberger and Fuchs 1978; Miles and Fuller 1975). One wonders if this latter subpopulation of FEF cells is the one that projected to the rNRTP cells that Ono et al. studied and the former (mentioned in the preceding paragraph) is a group of head-pursuit responsive FEF cells projecting to the rNRTP cells that we studied. A more definitive conclusion awaits a combined study of active head-pursuit and passive head movement responses in rNRTP. Given the anatomic projection of FEF to NRTP (e.g., Giolli et al. 2001), the responses to active head-pursuit that were observed in this study may have come from the FEF.

The studies of active head-pursuit responses in medial vestibular nucleus showed robust head-and-eye gaze pursuit responses in eye-head neurons (Roy and Cullen 2003), but they were weaker than VOR-responses in PVP neurons (Roy and Cullen 2001) and vestibular-only neurons (Roy and Cullen 2002). The head-and-eye gaze pursuit responses in eye-head neurons, which were larger than responses to passive whole body rotation in the dark, were attributed to an eye-head gaze velocity signal from the flocculus, even though Belton and McCrea (2000) did not observe head-pursuit responses in the flocculus. Given that the flocculus study used squirrel monkeys, Roy and Cullen (2003) argued that species differences could explain differences between the rhesus and squirrel monkeys concerning the floccular signals that impinge on eye-head neurons in the vestibular nucleus. Because a study of active head-pursuit responses in the rhesus floccular region is lacking, clarity about how the eye-head gaze-pursuit signal in eye-head vestibular neurons is formed remains to be established.

Head-position effects

The results suggested the possibility of an effect of initial head position on the head-pursuit response (Fig. 10). For at least three units, the amplitude of the head-pursuit response seemed to be dependent on the position in space where the head-pursuit was centered. Although the data were limited, they were included for completeness, because they were consistent with the initial eye position effects on eye-pursuit responses reported by Suzuki et al. (2003) for head-restrained preparations and with the effects of eccentric positions on the velocity of pursuit-like slow eye movements evoked with microstimulation within rNRTP (Yamada et al. 1996). The results indicate that, under three different experimental conditions, there was consistency in observing a dependence of response magnitude on head or eye eccentricity. This is true even in the absence, within the relevant neurons, of a head or eye position signal per se.

Cerebellar gaze-velocity Purkinje cells

Cells that encode both eye and head velocity responses during smooth pursuit have been recorded in Purkinje cells of the floccular region (Lisberger and Fuchs 1978; Miles and Fuller 1975) and vermal lobules VI and VII (vermis-6,7) (Suzuki and Keller 1988a,b). In these studies, responses to passive head velocity, elicited by en bloc oscillation of a head-restrained monkey, were taken as a generalized head-velocity signal. NRTP is known to project to the floccular region and to vermis-6,7 (Brodal 1980b, 1982). These anatomic observations together with the results of this study strongly suggest that rNRTP is a source, and perhaps the primary brain stem source, of an active head-pursuit signal that might exist in vermis-6,7. Whether the gaze- and target-velocity Purkinje cells in vermis-6,7 have an active head-pursuit velocity component remains to be determined, although the observation of a presumed active head-pursuit signal in fastigial nucleus would suggest its presence in vermis-6,7 (Suzuki et al. 2002).

Conclusion

The results complement observations of rNRTP neuronal responses during smooth-pursuit eye movements, microstimulation-evoked pursuit-like eye movements, deficits in smooth pursuit resulting from ibotenic acid–induced lesions, and the observed pursuit-like gaze movements evoked with microstimulation in head-unrestrained macaques (Ono et al. 2004; Suzuki et al. 1999a,b, 2003; Yamada et al. 1996). The observation of neuronal responses to both active head-pursuit and eye-pursuit generalizes rNRTP function beyond regulating smooth-pursuit eye movements to a role in controlling head-and-eye gaze-pursuit.

Head-and-eye gaze-pursuit responses were observed with voluntarily elicited head movements under conditions where the eyes were relatively stable in their orbits. The observation of head movement–related neuronal discharges in rNRTP supports the notion that this structure plays an important role in integrating a variety of motor and ocular motor signals destined for the cerebellum. Thus, besides NRTP activity related to saccadic eye movements (Crandall and Keller 1985), vergence eye movements (Gamlin and Clarke 1995), smooth-pursuit eye movements (Ono et al. 2004; Suzuki et al. 2003), and passive head movements (Ono et al. 2004), cells in rNRTP are responsive during voluntarily elicited head-pursuit movements. For the reasons given in the discussion, we think that at least some of our observed active head movement–related responses are motor in nature and presumably caused by inputs from FEF, premotor, and/or motor cortices (Giolli et al. 2001). Our results implicate rNRTP as a source of active head movement signals that presumably go to vermis-6,7 gaze-velocity and target-velocity Purkinje cells.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Eye Institute Grant EY-09082 and a Development Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness for the Department of Ophthalmology, Indiana University School of Medicine.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Rankin for surgical and general assistance, P. Giever and T. Ogino for help with data analysis, and T. Tu for computer programming. We are also grateful for the valuable suggestions and comments of the anonymous reviewers.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- Barnes and Lawson 1989.Barnes GR, Lawson JF. Head-free pursuit in the human of a visual target moving in a pseudo-random manner. J Physiol 410: 137–155, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belton and McCrea 2000.Belton T, McCrea RA. Role of the cerebellar flocculus region in the coordination of eye and head movements during gaze pursuit. J Neurophysiol 84: 1614–1626, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betelak et al. 2001.Betelak KF, Margiotti EA, Wohlford ME, Suzuki DA. An improved technique for attaching skull-anchored implants in alert non-human primates involved in long-term studies. J Neurosci Methods 112: 9–20, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzi et al. 1971.Bizzi E, Kalil RE, Tagliasco V. Eye-head coordination in monkeys: evidence for centrally patterned organization. Science 173: 452–454, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodal 1980a.Brodal P The cortical projection to the nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis in the rhesus monkey. Exp Brain Res 38: 19–27, 1980a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodal 1980b.Brodal P The projection from the nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis to the cerebellum in the rhesus monkey. Exp Brain Res 38: 29–36, 1980b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodal 1982.Brodal P Further observations on the cerebellar projections from the pontine nuclei and the nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 204: 44–55, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins and Barnes 1999.Collins CJ, Barnes GR. Independent control of head and gaze movements during head-free pursuit in humans. J Physiol 515: 299–314, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall and Keller 1985.Crandall WF, Keller EL. Visual and oculomotor signals in nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis in alert monkey. J Neurophysiol 54: 1326–1345, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen et al. 2004.Cullen KE, Huterer M, Braidwood DA, Sylvestre PA. Time course of vestibuloocular reflex suppression during gaze shifts. J Neurophysiol 92: 3408–3422, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichgans et al. 1973.Dichgans J, Bizzi E, Morasso P, Tagliasco V. Mechanisms underlying recovery of eye-head coordination following bilateral labyrinthectomy in monkeys. Exp Brain Res 17: 548–562, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima et al. 2005.Fukushima K, Kasahara S, Akao T, Kurkin SA. Discharge of pursuit neurons in frontal eye fields during active head movements. Soc Neurosci Abstr 166.6, 2005.

- Gamlin and Clarke 1995.Gamlin PDR, Clarke RJ. Single-unit activity in the primate nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis related to vergence and ocular accommodation. J Neurophysiol 73: 2115–2119, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giolli et al. 2001.Giolli RA, Gregory KM, Suzuki DA, Blanks RH, Lui F, Betelak KF. Cortical and subcortical afferents to the nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis and basal pontine nuclei in the macaque monkey. Vis Neurosci 18: 725–740, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb et al. 1993.Gottlieb JP, Bruce CJ, MacAvoy MG. Smooth eye movements elicited by microstimulation in the primate frontal eye field. J Neurophysiol 69: 786–799, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb et al. 1994.Gottlieb JP, MacAvoy MG, Bruce CJ. Neural responses related to smooth-pursuit eye movements and their correspondence with electrically elicited smooth eye movements in the primate frontal eye field. J Neurophysiol 72: 1634–1653, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton and Volle 1987.Guitton D, Volle M. Gaze control in humans: eye-head coordination during orienting movements to targets within and beyond the oculomotor range. J Neurophysiol 58: 427–459, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann-von Monakow et al. 1981.Hartmann-von Monakow K, Akert K, Künzle H. Projection of precentral, premotor and prefrontal cortex to the basilar pontine grey and to nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis in the monkey (Macaca fascicularis). Arch Suisses Neurologie 129: 189–208, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta et al. 1986.Huerta HF, Krubitzer LA, Kaas JH. Frontal eye field as defined by intracortical microstimulation in squirrel monkeys, owl monkeys, and macaque monkeys. I. Subcortical connections. J Comp Neurol 253: 415–439, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge et al. 1980.Judge SJ, Richmond BJ, Chu FC. Implantation of magnetic search coils for measurement of eye position: an improved method. Vision Res 20: 535–538, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating 1991.Keating EG Frontal eye field lesions impair predictive and visually-guided pursuit eye movements. Exp Brain Res 86: 311–323, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künzle et al. 1977.Künzle H, Akert K. Efferent connections of cortical, area 8 (frontal eye field) in Macaca fascicularis. A reinvestigation using the autoradiographic technique. J Comp Neurol 173: 147–164, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurutis and Robinson 1986.Laurutis VP, Robinson DA. The vestibulo-ocular reflex during human saccadic eye movements. J Physiol 373: 209–233, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichnetz 1986.Leichnetz GR Afferent and efferent connections of the dorsolateral precentral gyrus (area 4, hand/arm) in the macaque monkey, with comparisons to area 8. J Comp Neurol 254: 460–492, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichnetz et al. 1984.Leichnetz GR, Smith DJ, Spencer RF. Cortical projections to the paramedian tegmental and basilar pons in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 228: 388–408, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisberger and Fuchs 1978.Lisberger SG, Fuchs AF. Role of primate flocculus during rapid behavioral modification of vestibulo-ocular reflex. I. Purkinje cell activity during visually guided horizontal smooth pursuit eye movement and passive head rotation. J Neurophysiol 41: 733–763, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch 1987.Lynch JC Frontal eye field lesions in monkey disrupt visual pursuit. Exp Brain Res 68: 437–441, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAvoy et al. 1991.MacAvoy MG, Gottlieb JP, Bruce CJ. Smooth pursuit eye movement representation in the primate frontal eye field. Cereb Cortex 1: 95–102, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea and Gdowski 2003.McCrea RA, Gdowski GT. Firing behaviour of squirrel monkey eye movement-related vestibular nucleus neurons during gaze saccades. J Physiol 546: 207–224, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles and Fuller 1975.Miles FA, Fuller JH. Visual tracking and the primate flocculus. Science 189: 1000–1002, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasso et al. 1973.Morasso P, Bizzi E, Dichgans J. Adjustment of saccade characteristics during head movements. Exp Brain Res 16: 492–500, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono et al. 2004.Ono S, Das VE, Mustari MJ. Gaze-related response properties of DLPN and NRTP neurons in the Rhesus macaque. J Neurophysiol 91: 2484–2500, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pélisson et al. 1988.Pélisson D, Prablanc C, Urquizar C. Vestibuloocular reflex inhibition and gaze saccade control characteristics during eye-head orientation in humans. J Neurophysiol 59: 997–1013, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson 1963.Robinson DA A method of measuring eye movement using a scleral search coil in a magnetic field. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 10: 137–145, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy and Cullen 2001.Roy JE, Cullen KE. Selective processing of vestibular reafference during self-generated head motion. J Neurosci 21: 2131–2142, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy and Cullen 2002.Roy JE, Cullen KE. Vestibuloocular reflex signal modulation during voluntary and passive head movements. J Neurophysiol 87: 2337–2357, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy and Cullen 2003.Roy JE, Cullen KE. Brain stem pursuit pathways: dissociating visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive inputs during combined eye-head gaze tracking. J Neurophysiol 90: 271–290, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook et al. 1990.Shook BL, Schlag-Rey M, Schlag J. Primate supplementary eye field. I. Comparative aspects of mesencephalic and pontine connections. J Comp Neurol 301: 618–642, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton et al. 1988.Stanton GB, Goldberg ME, Bruce CJ. Frontal eye field efferents in the macaque monkey. II. Topography of terminal fields in midbrain and pons. J Comp Neurol 271: 493–506, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki et al. 1999a.Suzuki DA, Betelak KF, Yee RD. Head movements evoked by microstimulation of monkey nucleus reticularis tegmentis pontis (NRTP). Soc Neurosci Abstr 25: 1650, 1999a. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki and Keller 1988a.Suzuki DA, Keller EL. The role of the posterior vermis of monkey cerebellum in smooth-pursuit eye movement control. I. Eye and head movement-related activity. J Neurophysiol 59: 1–18, 1988a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki and Keller 1988b.Suzuki DA, Keller EL. The role of the posterior vermis of monkey cerebellum in smooth-pursuit eye movement control. II. Target velocity-related Purkinje cell activity. J Neurophysiol 59: 19–40, 1988b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki et al. 2002.Suzuki DA, Ogino T, Yee RD. Responses of fastigial nucleus cells to Macaque active head movements. Soc Neurosci Abstr 266.4, 2002.

- Suzuki et al. 1999b.Suzuki DA, Yamada T, Hoedema R, Yee RD. Smooth-pursuit eye-movement deficits with chemical lesions in macaque nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis. J Neurophysiol 82: 1178–1186, 1999b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki et al. 2003.Suzuki DA, Yamada T, Yee RD. Smooth-pursuit eye-movement-related neuronal activity in Macaque nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis. J Neurophysiol 89: 2146–2158, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabak et al. 1996.Tabak S, Smeets JBJ, Collewijn H. Modulation of the human vestibuloocular reflex during saccades: probing by high-frequency oscillation and torque pulses of the head. J Neurophysiol 76: 3249–3263, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson 1990.Tomlinson RD Combined eye-head gaze shifts in the primate. III. Contributions to the accuracy of gaze saccades. J Neurophysiol 64: 1873–1891, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada et al. 1996.Yamada T, Suzuki DA, Yee RD. Smooth pursuit-like eye movements evoked by microstimulation in macaque nucleus reticularis tegmenti pontis. J Neurophysiol 76: 3313–3324, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]