ABSTRACT

Introduction: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMFT) of the temporal bone is an unusual but distinct clinicopathologic entity. Case Report: We report the case of a 75-year-old patient with an IMFT located in the temporal bone. Symptoms included VI, X, XI, and XII cranial nerves palsies. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance images are described. The lesion was locally aggressive and outcome was fatal. IMFT was identified by analysis of postmortem specimen with histopathologic and immunohistochemical confirmation. Discussion: IMFT can be locally destructive lesions. Involvement of the skull base and cervical spine is indistinguishable from an aggressive infection or a malignant tumor and can be fatal as in our case report. The difficulties in establishing clinicopathologic diagnosis, radiological imaging characteristics, and treatment are discussed.

Keywords: Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, inflammatory pseudotumor, temporal bone, skull base

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMFT), also known as inflammatory pseudotumor, is an unusual histologically benign entity that presents clinically as invasive lesions that are rarely fatal. IMFT refers to a heterogeneous group of nonneoplastic lesions characterized by inflammatory cell infiltration and variable fibrotic reaction that can appear in different locations of the human body, although when occurring in head and neck, sites are less predictable, exhibiting local aggressiveness.1 IMFT is a rare disorder of unknown etiology that affects individuals of both sexes and of a wide range of ages and was first described in the lung.2 The upper respiratory tract is also commonly involved, with the larynx, trachea, oropharynx, and nasopharynx accounting for 11% of extrapulmonary cases.3 The remaining sites in the head and neck account for less than 5% of cases (involvement of the skull base or temporal bone is exceedingly rare). Williamson et al in 2003 only identified 10 cases,4 and we have not found more cases reviewing the PubMed online database.

IMFT must be differentiated from other infectious, granulomatous, and neoplastic lesions on the basis of histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings. Recent evidence reveals and confirms the clonal, neoplastic nature of IMFT.5 Treatment remains controversial, with excision, steroid therapy, and radiation therapy available as options depending on tumor location and behavior. Therapy should consist of surgical excision with steroids reserved for residual or intracranial disease or in patients in whom surgery is not an option.4

The purpose of this article is to report one case of IMFT located in the temporal bone with skull base extension in a 75-year-old man. The tumor exhibited aggressive features suggestive of a neoplasm. Clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic features are presented. The patient died 6 months after first presentation. Autopsy confirmed the diagnosis of IMFT of the temporal bone. The diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of IMFT are reviewed in this article.

CASE REPORT

We present the case of a 75-year-old Caucasian man with a 3- to 4-month history of severe headache with intermittent right-sided otorrhea and hearing loss. He denied previous ear infection, tinnitus, or vertigo. On examination, he was found to have a right tympanic membrane perforation with granulation tissue along the posterior portion. Otic bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal cultures were positive to Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Audiometry revealed a moderate right mixed hearing loss. Temporal bone computed tomographic (CT) scan showed opacification of the middle ear and mastoid with ossicular erosion and erosion of the tegmen tympani. The patient underwent radical tympanomastoidectomy for presumed cholesteatoma. The mass was centered in the attic region and eroded through the tegmen. There was extension into the anterior epitympanum and eustachian tube; semicircular canals and facial nerve were not involved. Histology was reported as fibrotic tissue with chronic inflammation. Postoperative evolution was satisfactory, and otorrhea and headache disappeared.

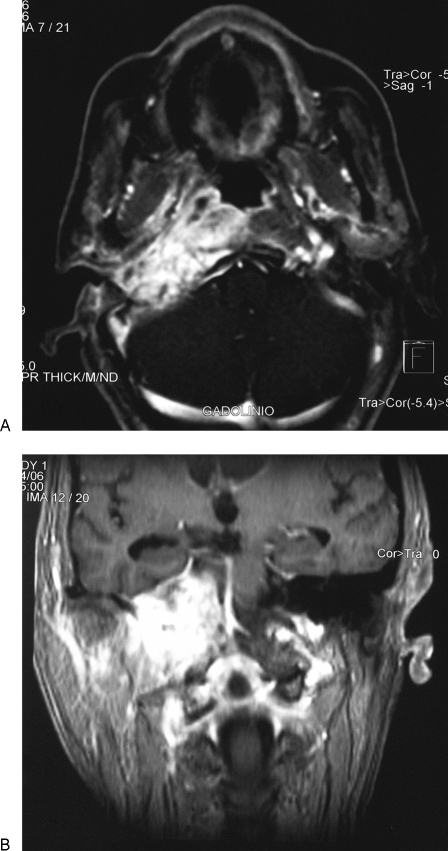

Two months later, the patient presented again with headache and right-side abducent nerve palsy (Fig. 1). Cranial and temporal bone CT showed temporal bone apex inflammatory changes and significant lateral skull base enhancement. Blood analysis showed leukocytosis (16.8 × 103, neutrophils 70.3%, lymphocytes 19.9%). Treatment was commenced with high-dose intravenous antibiotic (ceftazidime 2 g/8 hours), oral steroids (prednisolone 30 mg/d), carbamazepine (200 mg/12 hours), and omeprazole, to be taken for 6 weeks. Marked clinical improvement was observed but XII, X, and IX cranial nerve paralysis appeared 15 days later. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium (after antibiotic therapy) showed a homogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass of the right temporal bone with focal bone erosion and dural thickening into the posterior cranial fossa, and marked extension into lateral and medial skull base and cervical spine (Fig. 2). The lesion was suspicious of a skull base malignancy, and three consecutive biopsies of the cavum were performed, although they were nondiagnostic. The patient gradually deteriorated and died 2 months later.

Figure 1.

The patient presented right-side abducent nerve palsy.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium shows marked extension in posterior cranial fossa, lateral and medial skull base, and cervical spine. (A) Axial plane. (B) Coronal plane.

Autopsy Findings

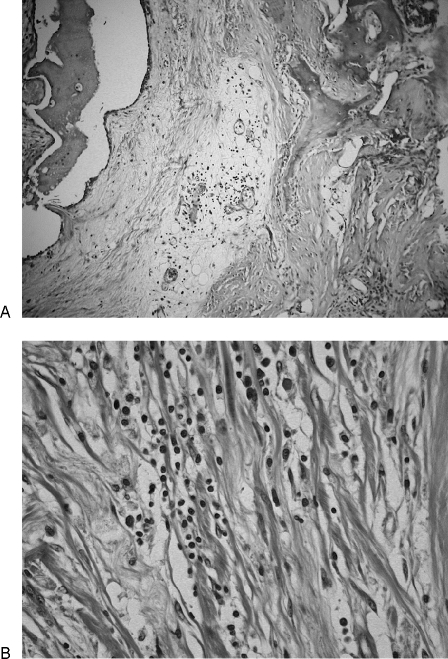

On gross examination, the lesion appeared beige to gray in color with a firm, homogenous texture, measuring 10 × 6 × 6 cm. On cut section, the tumor was fibrous with diffuse margins and invasion into the lateral and medial skull base and the posterior cranial fossa. Microscopically, characteristic findings included a few cellular foci of fibroblastic proliferations with thick collagenous fibers and sclerosis. Histopathology showed chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate with variable amounts of morphologically normal myofibroblasts, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Histiocytes were located in small microabscesses (Fig. 3). No evidence of pleiomorphism, granuloma formation, mitotic figures, or malignancy was found. Stains for mycobacteria, fungi, and viruses were negative. Immunohistochemically, myofibroblasts were not reactive with antibodies specific for bcl-2, cyclin D1, ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase), p53, and CD34. These features were consistent with an IMFT with a dense platelike collagen resembling fibrous scar tissue.

Figure 3.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification × 100. Microscopically, a few cellular foci of fibroblastic proliferations with thick collagenous fibers and sclerosis are observed. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification × 400. Fibrosis and lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate with variable amounts of morphologically normal myofibroblasts and plasma cells are shown.

DISCUSSION

IMFT of the temporal bone is an unusual lesion. Although histologically benign, IMFT is locally destructive, and it appears to have an unpredictable course. Bony erosion appears to be common, showing in the present case extension to skull base and vertebral bodies. In our case, paralysis of cranial nerves VI, IX, X, and XII showed the aggressive nature of the lesion. Facial nerve involvement also appears to be common, occurring in 44% of reported cases, although it is unusual as a presenting feature.4 In our case report, cranial nerve VII was spared.

The diagnosis of IMFT of the temporal bone is one of exclusion. Differential diagnosis variously includes malignant otitis externa, necrotizing bacterial or fungal osteomyelitis, cholesteatoma, granulomatous diseases such as histiocytosis X or eosinophilic granuloma, primary neoplasms, and metastasis. CT scanning and MRI should be performed in all cases because they are important radiological aids to delineate locally invasive extension into the skull base and the presence or absence of bony destruction.6,7 The diagnosis of a tumefactive fibroinflammatory lesion of the head and neck is made based on histological examination. Open biopsy is necessary for adequate tissue sampling and diagnosis; most authors feel that fine-needle aspiration biopsy is inadequate and is usually inconclusive.6 In our case report, a prior mastoidectomy and biopsy were performed but the histological appearance of the lesion did not have characteristics that could have directed a consideration of IMFT. The diagnosis was made only at the postmortem exam.

The pathogenesis of IMFT still remains unknown. Cytogenetic and molecular studies point to the possibility that at least some subsets of IMFT are in fact true neoplasms. Clonal rearrangements of the short arm of chromosome 2, involving the ALK receptor tyrosine kinase locus region, have been detected in up to 50% of soft tissue IMFTs.8,9 Other evidences reveal that the presence of ALK gene rearrangements and expression in the myofibroblastic component of the IMFTs are common in children and young adults and uncommon over the age of 40 years.5 In accordance with Gale et al,10 we found that the IMFT was not reactive with antibodies specific for cyclin D1, p53, bcl-2, or ALK.

Management options include corticosteroid therapy, subtotal or total surgical excision, and radiotherapy. Corticosteroid therapy may initially be successful for control, but given the variable nature and aggressive features of reported cases, definitive surgical excision should be the treatment of choice whenever possible.4 Considering the aggressive nature and complications of the disease, a more aggressive therapeutic approach may be indicated in extensive IMFT of the skull base.11 Radiotherapy is reserved for those lesions that fail to respond to steroid therapy, for cases with extensive or diffuse skull base involvement, or for recurrent or refractory disease, although its value remains unproven.4

In summary, IMFT of the temporal bone is an unusual but distinct clinicopathologic entity. Despite their benignity, they are locally destructive lesions. Involvement of the skull base and cervical spine by IMFT is usually indistinguishable from an aggressive infection or a malignant tumor and can be fatal as in our case report.

REFERENCES

- Batsakis J G, el-Naggar A K, Luna M A, Goepfert H. “Inflammatory pseudotumor”: what is it? How does it behave? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1995;104:329–331. doi: 10.1177/000348949510400415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadori M, Liebow A A. Plasma cell granulomas of the lung. Cancer. 1973;31:191–208. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197301)31:1<191::aid-cncr2820310127>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ereño C, Lopez J I, Grande J, Santaolalla F, Bilbao F J. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of the larynx. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:856–858. doi: 10.1258/0022215011909189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson R A, Paueksakon P, Coker N J. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the temporal bone. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:818–822. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200309000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenig B M. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editor. Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer, IARC Press; 2005. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour. pp. 150–151.

- Patel P C, Pellitteri P K, Vrabec D P, Szymanski M. Tumefactive fibroinflammatory lesion of the head and neck originating in the infratemporal fossa. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:216–219. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(98)90092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparotti R, Zanetti D, Bolzoni A, Gamba P, Morassi M L, Ungari M. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the temporal bone. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:2092–2096. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence B, Perez-Atayde A, Hibbard M K, et al. TPM3-ALK and TPM4-ALK oncogenes in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:377–384. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64550-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin C M, Patel A, Perkins S, Elenitoba-Johnson K S, Perlman E, Griffin C A. ALK and p80 expression and chromosomal rearrangements involving 2p23 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:569–576. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale N, Zidar N, Podboj J, Volavsek K, Luzar B. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of paranasal sinuses with fatal outcome: reactive lesion or tumour? J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:715–717. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.9.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y S, Kim S M, Chung W H, Hong S H. Inflammatory pseudotumour involving the skull base and cervical spine. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:580–584. doi: 10.1258/0022215011908298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]