Abstract

A synthesis of cat auditory cortex (AC) organization is presented in which the extrinsic and intrinsic connections interact to derive a unified profile of the auditory stream and use it to direct and modify cortical and subcortical information flow. Thus, the thalamocortical input provides essential sensory information about peripheral stimulus events, which AC redirects locally for feature extraction, and then conveys to parallel auditory, multisensory, premotor, limbic, and cognitive centers for further analysis. The corticofugal output influences areas as remote as the pons and the cochlear nucleus, structures whose effects upon AC are entirely indirect, and has diverse roles in the transmission of information through the medial geniculate body and inferior colliculus. The distributed AC is thus construed as a functional network in which the auditory percept is assembled for subsequent redistribution in sensory, premotor, and cognitive streams contingent on the derived interpretation of the acoustic events. The confluence of auditory and multisensory streams likely precedes cognitive processing of sound. The distributed AC constitutes the largest and arguably the most complete representation of the auditory world. Many facets of this scheme may apply in rodent and primate AC as well. We propose that the distributed auditory cortex contributes to local processing regimes in regions as disparate as the frontal pole and the cochlear nucleus to construct the acoustic percept.

1. Introduction

A century of experimental work has not defined the unique contribution of auditory cortex (AC) to hearing, nor explained how it accomplishes this functional mission, nor identified its precise limits. Much data describes its tonotopic (Schreiner et al., 2000) or binaural (Ehret, 1997) organization, or their absence (Schreiner, 1992), and the properties of single cells in some AC layers (e.g., layer IV) are known in detail (Smith and Populin, 2001), whereas those of cells in other layers (II) remain largely unexplored (Mitani et al., 1985). The data confirm indisputable AC participation in sound localization (Neff et al., 1975), binaural processing (Stecker et al., 2005), representational plasticity (Moucha et al., 2005), and experience related reorganization (Pollok et al., 2005), though its specific contribution relative to that of subcortical structures remains obscure. Likewise, there is substantial data on the primary area, AI, for several species (Winer, 1992), and far less on other tonotopic and non-primary, non-tonotopic areas, whose distinguishing anatomical features are largely unknown (Wallace et al., 1991), as are the relations between them.

It is timely nonetheless to summarize basic themes as an impetus to understanding AC function and framing future questions. This analysis concentrates on cat area AI except in a few instances where other fields with a cochleotopic representation are considered; less can be said about the non-primary areas, and a principled comparative perspective that includes humans and other primates on an equal footing will entail further study. This account is concerned less with matters of theory (serial or hierarchical processing, parallel or distributed networks, etc.) than in identifying circuits, cells, and connections enabling essential AC operations. A core premise is that monosynaptic AC influence extends to diverse sites in the medial geniculate body (MGB), inferior colliculus (IC), and amygdala, to name just three of many targets. The many corticofugal connections and the highly divergent network of corticocortical circuitry merit the appellation of distributed auditory cortex.

2. Mechanisms

This exposition relies primarily on connections for two reasons. First, functionality requires connections and circuits to implement its roles. Second, only a mere fraction of the total possible connections link auditory structures, thus constraining function.

2.1. Connections

The extrinsic connections of MGB and AC origin are summarized. Patterns of neuronal architecture (Fig. 1A) or intralaminar AC circuitry (Mitani and Shimokouchi, 1985) are known only in AI. The term, network, refers to the convergent and divergent projections that link areas and nuclei serially and hierarchically; many circuits are likely chemically specific, as in other modalities (Briggs and Callaway, 2001), and their roles remain to be enumerated. These diverse connectional networks support the idea of distributed AC functional processing. Too little is known about intrinsic and intralaminar AC connections to warrant specific functional conclusions.

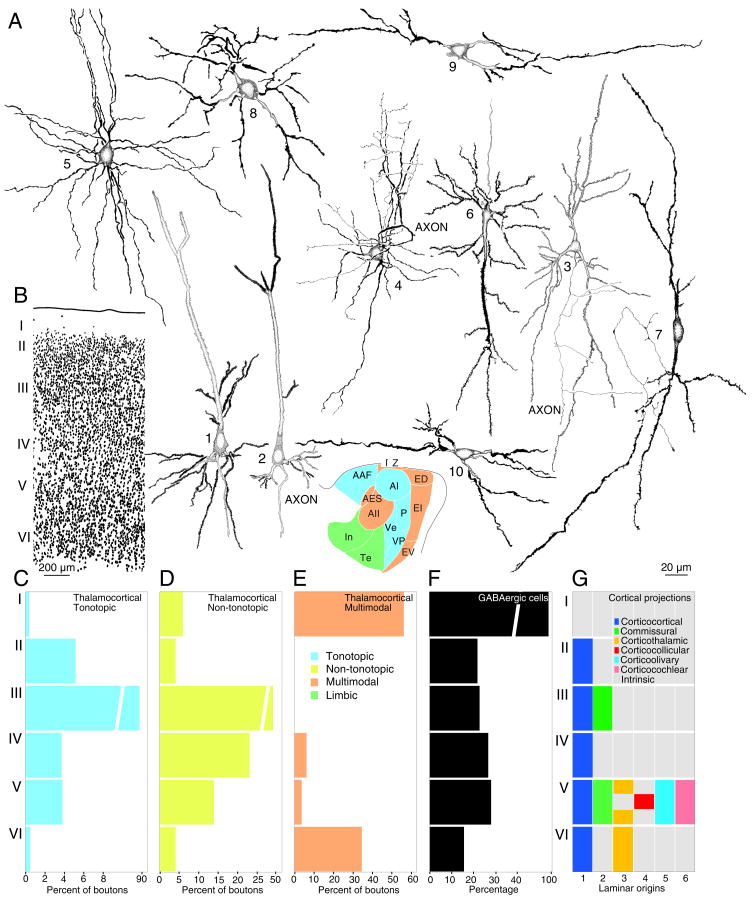

Fig. 1.

Some basic anatomical features of cat auditory cortex (AC) area AI (primary AC). (A) Major cell types include glutamatergic pyramidal cells (1–3), GABAergic basket (4) and multipolar (5) neurons, spinous inverted pyramidal cells (6), bipolar cells (7), small multipolar neurons (8), and horizontal cells in layers I (9) and VI (10). Many more subtypes are found in morphological studies limited largely to AI (Winer, 1992). Golgi-Cox impregnation, 140 μm thick section, planachromat, N.A. 0.95, ×1000. (B) AI cytoarchitecture shows a prominent layer I, a dense concentration of layer II cells, smaller layer IV cells, and columnar somatic arrangements in deeper layers. Nissl preparation, 30 μm thick celloidin embedded section, planapochromat, N.A. 0.65, ×500. (C–E) Laminar distribution of thalamocortical boutons after medial geniculate body (MGB) deposits of biotinylated dextran amines (Huang and Winer, 2000). Abscissa, bouton percentages/layer in pia-white matter traverses. (C) After ventral division tracer deposits, labeling is concentrated in layer III. (D) MGB dorsal division deposits had a wider laminar dispersion. (E) Medial division deposits had a bilaminar AC pattern. (F) The proportion of γ-aminobutyric acid-containing (GABAergic) AI cells is lamina specific. Antisera to GABA, 30 μm thick frozen section (Prieto et al., 1994b). (G) The laminar origins of six AI projection systems (1–6). While these origins overlap, few such neurons project to multiple subcortical targets (Wong and Kelly, 1981); gray background, intrinsic and local projections (Read et al., 2001), also present within the colored regions. 1: unpublished observations; 2: Code and Winer (1985); 3: Winer and Prieto (2001); 4: Winer (2005); 5: Schofield and Coomes (2004); 6: Schofield and Coomes (2005). For abbreviations, see the list.

2.1.1. Thalamocortical network

The spatial layout of characteristic frequency (CF) is perhaps the most thoroughly analyzed axis of MGB and AC functional organization. Complete CF maps are found in the MGB ventral division and the associated rostral pole nucleus (Imig and Morel, 1985a; Imig and Morel, 1985b), with CF in the dorsal (Aitkin and Dunlop, 1968) and medial (Aitkin, 1973) divisions partial or far less ordered. The projection topography of the dorsal and medial division to AC is, however, as ordered as that of the ventral division (Lee and Winer, 2005). Thus, even nuclei and areas without tonotopy have topographic extrinsic connections. The two MGB CF representations may contribute in AC to five (cat) (Clarey et al., 1992) or three (monkey) (Brugge and Reale, 1985) CF maps, implying that one TC role is the creation of new CF representations for emergent computations (Lee et al., 2004b; Lee et al., 2004a).

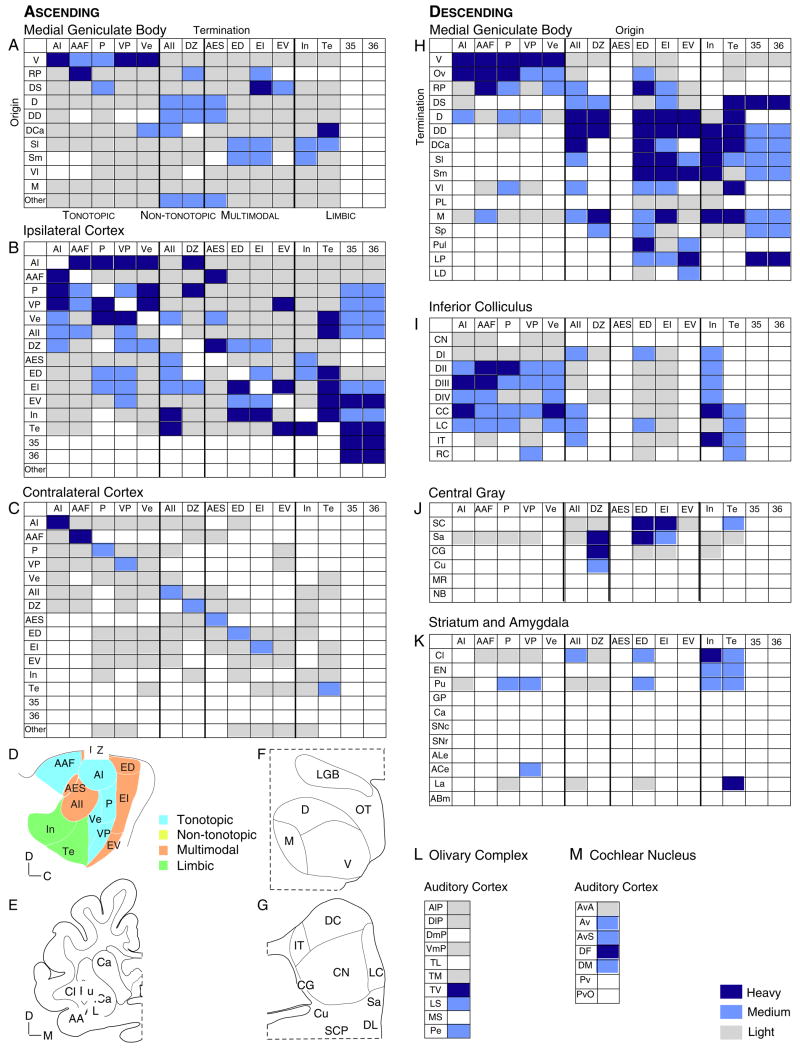

Thalamocortical (TC) projections constitute a network since they are topographic and largely reciprocal (single MGB divisions project to several AC areas, which in turn each project to multiple MGB targets) and because they entail bidirectional connections with the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN) (Crabtree, 1998). Several MGB divisions also project to the amygdala to establish auditory-limbic relations (Shinonaga et al., 1994). Thus, nuclei contributing to the several TC streams often receive reciprocal corticofugal projections, all AC areas receive MGB input (Huang and Winer, 2000), and thalamic connections may synchronize auditory, attentional, and limbic processes.

Each MGB division projects to unique areal and laminar targets: ventral division cells end primarily in tonotopic fields and in layer III chiefly (Fig. 1C:3), the medial division projects to all AC areas (Fig. 2A:M) and beyond, targeting layers I and VI mainly (Fig. 1E), and dorsal division cells (Fig. 2A:DS,D,DD,Sl,Sm) terminate preferentially in non-tonotopic areas and end in most layers (Fig. 1D). This implies TC areal selectivity and laminar stream segregation suggesting that MGB divisions may drive and modulate AC areas uniquely (Sherman and Guillery, 1998). The morphological diversity of TC axons supports this idea, with some layer I endings unexpectedly the largest (Huang and Winer, 2000). Input to AI alone is clustered and focal. Though the synaptic target of single TC axons is unknown, they may reach a diverse population of postsynaptic cells (Smith and Populin, 2001), a pattern permitting the accurate transmission of specific stimulus features and differential concurrent integration patterns between functional domains (Miller et al., 2002). All MGB divisions have comparable projection topography with similar spatial source and target relationships (Lee and Winer, 2005).

Fig. 2.

AC extrinsic connections. Ascending (A–C) and descending (H–M) projections. (A) The areal distribution of thalamocortical axons is widespread (Huang and Winer, 2000). (B) Ipsilateral corticocortical long range projections suggest that the tonotopic areas (AI, AAF, P, VP, Ve) are a group, that the non-primary areas (AII, AES, DZ) have a wide range of weaker inputs which largely exclude multisensory and limbic sources; and that limbic (In, Te) and multisensory areas (ED, EI, EV) are independent of the tonotopic areas and have mutual and reciprocal inputs with one another (unpublished observations). (C) The commissural projections are smaller and more reciprocal than those of the corticocortical system (unpublished observations). (D) Cat AC areas (Lee and Winer, 2005). (E) Cat basal forebrain subdivisions (Beneyto and Prieto, 2001). (F) Cat MGB subdivisions (Winer, 1992). (G) Cat inferior colliculus subdivisions (Winer, 2005). (H) Corticothalamic projections are as specific and focal as thalamocortical projections (A) (Winer et al., 2001). (I) Corticocollicular projections show modest central nucleus input and non-primary AC projections as topographic as those of the primary areas (Winer et al., 1998). (J) Central gray input arises largely from multisensory and non-primary AC (Winer et al., 1998). (K) Corticostriatal and corticoamygdaloid input is as specific as that of the corticothalamic streams (Beneyto and Prieto, 2001). (L) Rodent corticoolivary (Schofield and Coomes, 2004) and (M) corticocochlear projections (Schofield and Coomes, 2005) are target-specific.

2.1.2. Corticocortical network

The auditory, multisensory, and limbic-related MGB streams are elaborated and extended in AC by the corticocortical (COR; Fig. 2B) and commissural (CM; Fig. 2C) systems which, together, constitute ~85% of extrinsic AC input (Lee et al., 2004b; Lee et al., 2004a). Several principles have emerged in studies of AC COR connectivity in cat (Lee et al., 2004b) and marmoset (de la Mothe et al., 2006). Each area projects to many, even all, ipsilateral fields. Areas with ordered CF representations have strong connections with similarly ordered fields, and weaker connections with other areas. Projections within an area are the largest single input, in accord with analyses of local connectivity (Read et al., 2001). Fewer than five areas form the bulk of the COR projection to a given field. Supra- and infragranular layers contribute to the COR system, but have origins restricted to specific AC sources and targets (Fig. 1G:1). Infragranular projections are common in areas with clear CF, while some fields have mixed convergence patterns, e.g., area AII receives input from three supra-, three infra-, and seven bilaminar sources. Areal and laminar COR connections are highly divergent and do not have a simple serial pattern.

In the macaque, long range COR projections contribute to two parallel streams (Fig. 3F) that link AC and extraauditory cortex (Rauschecker and Tian, 2000). A dorsal pathway (‘where’) projects from core (tonotopic) and belt (adjoining) areas to the posterior parietal cortex. A second stream (‘what’) arises from the belt areas and targets parabelt areas, which project to temporal fields T2/T3. Both streams converge in prefrontal areas 8a, 46, 10, and 12, perhaps for global integration.

Fig. 3.

The distributed AC and its extrinsic relations. (A) The ascending (black) and descending (blue) auditory systems. (B) The multimodal limb targets primarily non-tonotopic AC areas (Bowman and Olson, 1988a), which are linked to tonotopic areas via corticocortical input (Bowman and Olson, 1988b). Vestibular and somatic sensory influence reaches MGB subdivisions (Blum et al., 1979) which project widely to AC and beyond (Winer and Morest, 1983). (C) The premotor relations with nigral, striatal, and paralemniscal areas might coordinate skeletal (Olazábal and Moore, 1989) and smooth muscle (Winer, 2006) and vocalization-related pathways (Feliciano et al., 1995) in auditory and multimodal behaviors. (D) The plasticity-associated limb is related to nucleus basalis (NB/SI) input to AC (Kamke et al., 2005). Perirhinal cortex targets both MGB (chiefly non-lemniscal) and AC (all areas) extensively (Witter and Groenewegen, 1986). (E) The AC input to the amygdala (Al) and central gray (CG) allows access to many extraauditory sites (Clascá et al., 2000). (F) In the macaque, convergent input to the prefrontal cortex may represent parallel acoustic object recognition and localization streams, respectively (Rauschecker and Tian, 2000); frontal lobe influence likewise reaches wide expanses of the supratemporal plane (Jones and Powell, 1970). Input from the multimodal suprageniculate nucleus (Sl) to the frontal lobe (?) is of unknown significance (Kobler et al., 1987). Relations with the thalamic reticular nucleus (Crabtree, 1998) and the effects of ventral tegmental stimulation on AC plasticity (Bao et al., 2001) have been omitted for reasons of space. See text for discussion.

2.1.3. Commissural network

The CM pathway in cat (Lee et al., 2004a) and marmoset (de la Mothe et al., 2006) is highly reciprocal, often clustered and focal, and nearly an order of magnitude smaller than the COR network. Projections arise in, and target, fewer fields than the COR system (Fig. 2C). Some inputs have unexpected origins, e.g. from non-tonotopic areas to fields with a CF gradient, and the converse, though heterotopic projections are relatively smaller. Layers III and V are the exclusive laminar origins (Code and Winer, 1985), with layer III in certain areas only and other areas having bilaminar origins; these diverse laminar patterns do not permit a comprehensive functional interpretation. However, the CM system may cooperate with TC (Middlebrooks and Zook, 1983) and interhemispheric (Imig and Brugge, 1978) binaural interactions.

2.1.4. Corticofugal network

The traditional view that the corticofugal (COF) projections are primarily engaged in feedback (Winer, 2006) has been modified by studies of their diverse physiological influences on MGB (Villa et al., 1991) and IC (Jen et al., 2001) and anatomical investigations with sensitive axoplasmic tracers reveal considerable morphologic variety (Bajo et al., 1995). COF projections terminate in many ascending auditory stations as specifically and selectively (Fig. 2H–M) as does the afferent system, and their size and many origins imply that parallel descending streams embody a distributed network. COF projections arise from layers V and VI only, involve pyramidal cells exclusively (Prieto and Winer, 1999; Winer and Prieto, 2001), are primarily glutamatergic (Kharazia et al., 1996), and their axon morphology is origin- and target-specific (Winer et al., 1999; Winer, 2005).

The corticothalamic system is the largest COF projection, with all MGB divisions receiving input (Fig. 2H). Some polysensory and limbic-related AC areas project to almost all MGB divisions, while the tonotopic areas have more focal input to MGB areas with similar functional attributes. Projections from AI layers Va, Vc, and VI may form parallel COF pathways (Fig. 1G) (Winer, 2006).

The corticocollicular projection is relatively smaller and targets chiefly the IC dorsal and lateral (external) cortex (Winer et al., 1998), both of which are extralemniscal nuclei (Coleman and Clerici, 1987). Rodents may receive more input to the central nucleus (Saldaña et al., 1996) than cats (Winer et al., 1998) and monkeys (FitzPatrick and Imig, 1978). Projections to the central gray and amygdala (Romanski and LeDoux, 1993) constitute an auditory-limbic interface complementary to the thalamolimbic input (Shinonaga et al., 1994). Other targets are the ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body, lateral superior olive, and dorsal cochlear nucleus (Schofield and Coomes, 2004, 2005); these projections decrease in size (but not density) with distance from AC.

Premotor targets include the striatum (from most AC areas) (Reale and Imig, 1983), the pontine nuclei (all areas), and the bat paralemniscal midbrain (Schuller et al., 1991). Corticopontine input is highly focal and divergent (Perales et al., 2006), whereas corticocollicular and corticothalamic projections are more continuous (Winer, 2005).

2.2. Neurochemistry

Distributed processing embodies interactions between extrinsic and intrinsic projections. The intricate laminar differences in local circuit neurons suggest that each AC layer is modulated locally in complex ways that remain to be defined (Sutter and Loftus, 2003). Neurons accumulating γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) represent ~20–25% of cells in monkey sensory and motor cortex (Hendry et al., 1987) and cat AC (Prieto et al., 1994b) (Fig. 1F) and likely project to targets within <1–2 mm (Kisvárday et al., 1993). Intrinsic axons of pyramidal cells (Winer, 1984; Mitani and Shimokouchi, 1985) make local, presumptively glutamatergic contributions (Prieto and Winer, 1999).

2.2.1. Gamma aminobutyric acid

The proportion of GABAergic neurons (Fig. 1F) ranges from >90% (layer I) to 16% (VI) to 25% (IV) (Prieto et al., 1994b). Puncta (axon terminals) are also layer- and cell-specific (Prieto et al., 1994a). Some GABAergic types occur in many layers (small multipolar or bipolar cells) and others in one (layer II extraverted multipolar cells) or two layers (horizontal cells in layers I and VI; Fig. 1A:9,10). Some GABAergic neurons have morphologic variants (small, medium, and large multipolar cells), others are distinguished only biochemically (visual cortex bipolar cell subtypes) (Peters and Harriman, 1988), and some have synaptic specializations (chandelier cells) (De Carlos et al., 1987) or unique targets (basket cells) (Kisvárday et al., 2002) or dendritic specializations (inverted pyramidal cells; Fig. 1A:6) (Winer and Prieto, 2001). In monkey visual cortex, each chemically and morphologically specific layer VI cell type (Briggs and Callaway, 2001) may represent a subclass; if so, the phenotypic range of neocortical interneurons may be immense. Such local arrangements likely provide key contributions to circuits for feature extraction in the several intercortical functional streams described below.

2.2.2. Acetylcholine

The nucleus basalis (Jones et al., 1976) is the main extrinsic cholinergic input to AC, though a few AC cells are immunopositive, and all layers receive immunostained axons (Kamke et al., 2005). The widespread cholinergic AC innervation suggests roles (Metherate et al., 2005) complementary to the serotonergic (Descarries et al., 1975) and noradrenergic (Descarries et al., 1977) systems.

3. Functional profile

The distributed AC elaborates several processes begun in the auditory brain stem, and may initiate new operations. These might include the creation of new areas and CF maps; emergent processing regimes might arise from direct and indirect limbic connections, and massive COF projections to the MGB and IC.

3.1. Audition

The formation of multiple, interdependent AC feature maps may be a major task of the TC system. Thus, the MGB contributions to CF maps in areas AI and AAF (anterior auditory field) are ~98% independent (Lee et al., 2004b). Since the MGB contains only two complete CF maps (Imig and Morel, 1984, 1985a), interspersed TC cells contribute to these independent representations, and few cells diverge to both areas.

A second facet of distributed AC organization is that all extrinsic areal connections —tonotopic, non-tonotopic, multisensory, and limbic affiliated —are highly, and equally, topographic (Lee and Winer, 2005). This shared internal metric may coordinate processing across five primary and eight non-primary areas.

3.2. Multisensory processing

The AC has a distributed role in multisensory processing as well as in hearing. Five auditory or periauditory cortical areas have visual input (Bowman and Olson, 1988a); AC abuts visual and polysensory areas (Stein and Meredith, 1993); there are direct visual influences on AC neurons (Schroeder et al., 2001); AC has COR projections to multisensory areas (Mellott et al., 2004); and COF auditory influences reach the visual thalamus (Winer et al., 2001) and midbrain (Winer et al., 1998). Collectively, these several, often reciprocal, influences suggest a web of relations among multisensory areas and nuclei. Unlike the apparent AC emergence of multiple CF maps, the multisensory relations appear early as somatic sensory input to the cochlear nucleus (Young et al., 1995) or as visual interactions with sound localization (Heffner and Heffner, 1992), or as crosstalk between the IC and the superior colliculus (García del Caño et al., 2006)

3.3. Limbic function

Robust corticoamygdaloid input may mediate visceromotor and appetitive behavior (Romanski and LeDoux, 1993), while the central gray projection could shape defensive and agonistic processes (Brandão et al., 1988). These pathways also have reciprocal and extended connections with the distributed AC. Thus, divergent projections reach IC subdivisions with robust and reciprocal central gray connections (Kipps et al., 2005). Likewise, corticogeniculate input targets MGB divisions receiving parahippocampal input (Witter and Groenewegen, 1986) and which have strong reciprocal amygdaloid connections (Shinonaga et al., 1994). This enables monosynaptic auditory corticoamygdaloid and disynaptic and reciprocal corticothalamoamygdaloid and corticoamygdalothalamic streams. The distributed AC is thus ultimately confluent with the extended amygdala (Swanson and Petrovich, 1998). Without such neural mechanisms it is difficult to envision how rapid and specific auditory–limbic interactions are enabled and coordinated.

3.4. Premotor

Motor activity influenced by audition includes somatic, visceral, vocal behavior, and movement planning components. Acoustic startle and its inhibition are shaped by sensory input that requires integration across these four domains. AC input to the putamen arises from primary, non-primary, multisensory, and limbic related fields (Beneyto and Prieto, 2001) and might affect motor set and cognitive aspects of movement planning. Corticocollicular projections target IC subdivisions (Winer et al., 1998) with robust substantia nigra input (Olazábal and Moore, 1989) and corticofugal AC axons end in the adjoining intralaminar nuclei (Winer et al., 2001), which modulate global TC excitability and vigilance (Steriade, 1997). Moreover, AC projections to the superior colliculus may synchronize pinna, eye, and head movements (Diamond et al., 1969; Berman and Payne, 1982).

Visceromotor tone might reflect AC input to central gray (Winer et al., 1998) subdivisions implicated in agonistic and defensive behavior (Graeff et al., 1993); such input arises from insular (Clascá et al., 1997), but not temporal, cortex, confirming their independence and suggesting parallel descending pathways (Winer, 2005, 2006).

AC input to the paralemniscal zone can affect bat vocalizations (Schuller et al., 1997). Corticopontine projections arise from all AC regions, consistent with the view that AC tonotopic, non-tonotopic, multisensory, and limbic areas each influence premotor control (Perales et al., 2006). An even more direct role is postulated for AC input to olivocochlear cells (Mulders and Robertson, 2000).

3.5. Cognitive networks

When essential spatiotemporal information has been extracted, what becomes of these perceptual computations? Serial models do not require a terminus, and the extraauditory affiliations of primate AC extend far into the frontal lobe (Fig. 3F), with specific stepwise parietofrontal and temporofrontal progressions arising from particular MGB domains (Romanski et al., 1999). A third supratemporal stream ends in areas 8B, 9, 10, and 12; and area 22 in the superior temporal sulcus and associated cortex target frontal lobe areas 10, 12, and 25. Frontotemporal streams then influence broad supratemporal territories (Jones and Powell, 1970). Imaging studies have extended the limits of primate auditory, auditory–visual, frontal, and prefrontal areas (Poremba et al., 2003), though the connectivity sequence remains incomplete. Projections from the bat suprageniculate nucleus to frontal cortex (Fig. 3F:Sl) might convey multisensory information for extraauditory processes (Kobler et al., 1987).

4. Themes

Two signal features of AC anatomical organization are the breadth and diversity of its connections and the intricacy of its local circuits. The range of its extrinsic projections —from the cochlear nucleus to the frontal pole —suggests that the distributed AC may have manifold functional roles.

4.1. Representation and computation

Human AC must decode many natural and synthetic languages and sounds, a capacity whose substrates are enigmatic. How do the network elements represent auditory experience? Some areas have conserved CF organization and narrow tuning curves (Clarey et al., 1992), systematic binaural representation (Middlebrooks and Zook, 1983), and mainly auditory input (Winer and Schreiner, 2005); this is the classical lemniscal system (Fig. 3A: black). Other areas have weak CF organization, broad tuning curves, non-topographic representation of aurality and other features, and strong polysensory or limbic inputs related only indirectly to hearing (Winer and Morest, 1983). Lemniscal forebrain damage causes spatial and spectral deficits (Jenkins and Masterton, 1982); extralemniscal trauma affects integrative tasks such as the extraction of patterns embedded in noise (Neff et al., 1975). This suggests that certain AC areas have primarily a representational role, whereas areas without such topographies remain available for rapid functional reassignment. The model predicts, and the data confirm, that corticocortical connections are divergent, convergent, and often reciprocal (Lee et al., 2004b); that relatively weak areal relations are the norm (Lee and Winer, 2005); that no area dominates another (Lee et al., 2004a); that resident neural circuitry enables areas to respond to new demands flexibly and with appropriate computational capacity (Winer et al., 2005); and that all extrinsic connections obey common topographic principles for purposes of representational coherence (Lee and Winer, 2005).

This present, four-part scheme envisions that families or small suites of areas rapidly forge and dissolve computational alliances to meet new perceptual demands. It requires that most AC areas are tonotopically uncommitted (Schreiner and Cynader, 1984), and supports the idea that population coding optimizes the cooperative capacity of transient or weak ad hoc and adventitious connectivity between areas or small neural ensembles (Furukawa et al., 2000).

4.2. Plasticity and auditory function

The question remains as to the role(s) of the corticofugal system(s). The usual candidates are: feedback, reciprocity, parity, executive control, and hegemony (Winer, 2006). None is entirely satisfactory; all are descriptive rather than analytic. For example, why should feedback be necessary if spiral ganglion cells faithfully encode peripheral dynamic changes more rapidly than AC cells can? If reciprocity is important, what computations in AC proscriptively direct the MGB or IC as to the import of afferent signals? If so, from where does AC derive, and how does it seriate, such instructions? How does parity operate when the AC influences target areas, e.g., the pontine nuclei, whose relations to AC are remote and most indirect? If the AC exerts executive control, then what purpose is served by the corticostriatal connections, which can hardly be said to be executive in any sense? If the corticofugal system is hegemonic, then why are vast caudal brain stem territories, e.g., the anteroventral cochlear nucleus, the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body, the lateral lemniscal nuclei, devoid of such input? Finally, if a role of AC is to instantiate plasticity in subcortical dependencies, does this mean that species without AC are incapable of such plasticity, and that those with a large neocortex enjoy more of it? What processes enable and disable the commands that initiate, sustain, and terminate plasticity? If AC engenders subcortical plasticity, what process limits its dispersion, and what global mechanism coordinates the plasticity from area to area and from area to nucleus so that the plasticity itself is coherent? Answers to these and related questions will clarify the many roles of the distributed auditory cortex.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. J.J. Prieto for drawing Fig. 1A. We appreciate Dr. C.E. Schreiner’s helpful comments. We are grateful to D.T. Larue for assistance with the figures. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 DC02319-28.

Abbreviations

- AA

amygdala, anterior nucleus

- AAF

anterior auditory field

- ABl

amygdala, basolateral nucleus

- ABm

amygdala, basomedial nucleus

- ACe

amygdala, central nucleus

- AD

dorsal cochlear nucleus, anterior part

- AES

anterior ectosylvian sulcus area

- AI

A1, auditory cortex, primary area

- AII

auditory cortex, second area

- AL

lateral field of belt AC

- Al

amygdala, lateral nucleus

- ALe

ansa lenticularis

- AlP

anterolateral periolivary nucleus

- AV

anterior ventral thalamic nucleus

- Av

anteroventral cochlear nucleus

- Ava

anteroventral cochlear nucleus, anterior division

- AvS

anteroventral cochlear nucleus, small cell cap

- Ca

caudate nucleus

- Cb

cerebellum

- CC

caudal cortex of the IC

- CE

cuneate nucleus, external subdivision

- CG

central gray

- CL

caudal lateral AC

- Cl

claustrum

- CM

caudal medial AC

- CN

central nucleus of the IC

- Cu

cuneiform nucleus

- CR

cuneiform nucleus, rostral part

- D

dorsal nucleus of the MGB or dorsal

- DC

dorsal cortex of IC

- DCa

caudal dorsal nucleus of the MGB

- DCN

dorsal cochlear nucleus

- DD

deep dorsal nucleus of the MGB

- DF

dorsal cochlear nucleus, fusiform cell layer

- DI-DIV

layers I-IV of IC dorsal cortex

- DL

dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus

- DlP

dorsolateral periolivary nucleus

- DM

dorsal cochlear nucleus, molecular layer

- DmP

dorsomedial periolivary nucleus

- DS

dorsal superficial nucleus of the MGB

- DZ

dorsal auditory zone

- ED

posterior ectosylvian gyrus, dorsal part

- EI

posterior ectosylvian gyrus, intermediate part

- EI

posterior ectosylvian gyrus, intermediate part

- EN

entopeduncular nucleus

- EP

posterior ectosylvian gyrus

- EV

posterior ectosylvian gyrus, ventral part

- GP

globus pallidus

- Hip

hippocampus

- Hyp

hypothalamus

- ICa

internal capsule

- IL

intermediate nucleus of lateral lemniscus

- IlN

intralaminar thalamic nucleus

- In

insular cortex

- IO

inferior olive

- IT

intercollicular tegmentum

- L

limitans nucleus

- LC

lateral cortex of the IC

- LD

lateral dorsal nucleus

- LGN

lateral geniculate nucleus

- LP

lateral posterior nucleus

- LS

lateral superior olive

- LT

lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body

- LV

lateral vestibular nucleus

- M

medial division of the MGB or medial

- MCP

middle cerebellar peduncle

- MGd

dorsal division of MGB

- MGv

ventral division of MGB

- ML

medial field of belt AC

- MR

mesencephalic reticular formation

- MS

medial superior olive

- MT

medial nucleus of the trapezoid body

- NB/SI

nucleus basalis/substantia innominata

- OT

optic tract

- Ov

pars ovoidea of the ventral division of the MGB

- P

auditory cortex, posterior area

- PB

parabelt cortex

- Pd

posterodorsal division of the DCN

- Pe

periolivary nuclei

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PL

posterior limitans nucleus

- Pl

paralemniscal area

- PN

pontine nuclei

- PP

posterior parietal cortex

- Pt

pretectum

- Pu

putamen

- Pul

pulvinar nucleus

- Pv

cochlear nucleus, posteroventral part

- PvA

posteroventral cochlear nucleus, anterior part

- PvO

posteroventral cochlear nucleus, octopus cell area

- R

rostral auditory area or rostral

- RP

rostral pole of MGB

- Sa

nucleus sagulum

- SC

superior colliculus

- SCP

superior cerebellar peduncle

- Sl

suprageniculate nucleus, lateral part

- Sm

suprageniculate nucleus, medial part

- SN

substantia nigra

- SNc

substantia nigra, pars compacta

- SNr

substantia nigra, pars reticulata

- Sp

subparafascicular and suprapeduncular nuclei

- Te

temporal cortex

- TL

trapezoid body, lateral nucleus

- TM

trapezoid body, medial nucleus

- TRN

thalamic reticular nucleus

- TV

trapezoid body, ventral nucleus

- V

pars lateralis of the MGB ventral division or ventral

- T2/T3

areas 2 and 3 of temporal cortex

- Ve

auditory cortex, ventral area

- Ver

cerebellar vermis

- Vl

ventrolateral nucleus of the MGB

- VmP

ventromedial periolivary nucleus

- VP

auditory cortex, ventral posterior area

- VSN

spinal trigeminal nucleus

- VST

spinal trigeminal tract

- VT

ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body

- I-VI

layers of AC

- 35

parahippocampal cortex, area 35

- 36

parahippocampal cortex, area 36

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aitkin LM. Medial geniculate body of the cat: responses to tonal stimuli of neurons in medial division. J Neurophysiol. 1973;36:275–283. doi: 10.1152/jn.1973.36.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin LM, Dunlop CW. Interplay of excitation and inhibition in the cat medial geniculate body. J Neurophysiol. 1968;31:44–61. doi: 10.1152/jn.1968.31.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajo VM, Rouiller EM, Welker E, Clarke S, Villa AEP, de Ribaupierre Y, de Ribaupierre F. Morphology and spatial distribution of corticothalamic terminals originating from the cat auditory cortex. Hearing Res. 1995;83:161–174. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)00199-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Chan VT, Merzenich MM. Cortical remodelling induced by activity of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. Nature. 2001;412:79–83. doi: 10.1038/35083586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneyto M, Prieto JJ. Connections of the auditory cortex with the claustrum and endopiriform nucleus in the cat. Brain Res Bull. 2001;54:485–498. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman N, Payne BR. Contralateral corticofugal projections from the lateral, suprasylvian and ectosylvian gyri in the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1982;47:234–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00239382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum PS, Abraham LD, Gilman S. Vestibular, auditory and somatic input to the posterior thalamus of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1979;34:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00238337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman EM, Olson CR. Visual and auditory association areas of the cat’s posterior ectosylvian gyrus: thalamic afferents. J Comp Neurol. 1988a;272:15–29. doi: 10.1002/cne.902720103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman EM, Olson CR. Visual and auditory association areas of the cat’s posterior ectosylvian gyrus: cortical afferents. J Comp Neurol. 1988b;272:30–42. doi: 10.1002/cne.902720104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandão ML, Tomaz C, Borges PC, Coimbra NC, Bagri A. Defense reaction induced by microinjections of bicuculline into the inferior colliculus. Physiol Behav. 1988;44:361–365. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs F, Callaway EM. Layer-specific input to distinct cell types in layer 6 of monkey primary visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3600–3608. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03600.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugge JF, Reale RA. Auditory cortex. In: Peters A, Jones EG, editors. Cerebral Cortex, volume 4, Association and Auditory Cortices. Plenum Press; New York: 1985. pp. 229–271. [Google Scholar]

- Clarey JC, Barone P, Imig TJ. Physiology of thalamus and cortex. In: Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research, volume 2, The Mammalian Auditory Pathway: Neurophysiology. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1992. pp. 232–334. [Google Scholar]

- Clascá F, Llamas A, Reinoso-Suárez F. Insular cortex and neighboring fields in the cat: a redefinition based on cortical microarchitecture and connections with the thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1997;384:456–482. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970804)384:3<456::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clascá F, Llamas A, Reinoso-Suárez F. Cortical connections of the insular and adjacent parieto-temporal fields in the cat. Cerebral Cort. 2000;10:371–399. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Code RA, Winer JA. Commissural neurons in layer III of cat primary auditory cortex (AI): pyramidal and non-pyramidal cell input. J Comp Neurol. 1985;242:485–510. doi: 10.1002/cne.902420404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JR, Clerici WJ. Sources of projections to subdivisions of the inferior colliculus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1987;262:215–226. doi: 10.1002/cne.902620204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree JW. Organization in the auditory sector of the cat’s thalamic reticular nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1998;390:167–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carlos JA, Lopez-Mascaraque L, Ramon y Cajal-Agueras S, Valverde F. Chandelier cells in the auditory cortex of monkey and man: a Golgi study. Exp Brain Res. 1987;66:295–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00243306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Mothe L, Blumell S, Kajikawa Y, Hackett TA. Cortical connections of the auditory cortex in marmoset monkeys: core and medial belt regions. J Comp Neurol. 2006;496:27–71. doi: 10.1002/cne.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L, Beaudet A, Watkins KC. Serotonin nerve terminals in adult rat neocortex. Brain Res. 1975;100:563–588. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L, Watkins KC, Lapierre Y. Noradrenergic axon terminals in the cerebral cortex of rat: topometric ultrastructural analysis. Brain Res. 1977;133:197–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90759-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond IT, Jones EG, Powell TPS. The projection of the auditory cortex upon the diencephalon and brain stem of the cat. Brain Res. 1969;15:305–340. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(69)90160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehret G. The auditory cortex. J Comp Physiol A. 1997;181:547–557. doi: 10.1007/s003590050139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano M, Saldaña E, Mugnaini E. Direct projections from the rat primary auditory neocortex to nucleus sagulum, paralemniscal regions, superior olivary complex and cochlear nuclei. Auditory Neurosci. 1995;1:287–308. [Google Scholar]

- FitzPatrick KA, Imig TJ. Projections of auditory cortex upon the thalamus and midbrain in the owl monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1978;177:537–556. doi: 10.1002/cne.901770402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa S, Xu L, Middlebrooks JC. Coding of sound-source location by ensembles of cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1216–1228. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01216.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García del Caño G, Gerrikagoitia I, Alonso-Cabria A, Martínez-Millán L. Organization and origin of the connection from the inferior to the superior colliculi in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:716–731. doi: 10.1002/cne.21107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeff FG, Silveira MCL, Nogueira RL, Audi EA, Oliveira RMW. Role of amygdala and periaqueductal gray in anxiety and panic. Behav Brain Res. 1993;58:123–131. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90097-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner RS, Heffner HE. Visual factors in sound localization in mammals. J Comp Neurol. 1992;317:219–232. doi: 10.1002/cne.903170302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry SHC, Schwark HD, Jones EG, Yan J. Numbers and proportions of GABA-immunoreactive neurons in different areas of monkey cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1503–1519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-05-01503.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CL, Winer JA. Auditory thalamocortical projections in the cat: laminar and areal patterns of input. J Comp Neurol. 2000;427:302–331. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001113)427:2<302::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig TJ, Brugge JF. Sources and terminations of callosal axons related to binaural and frequency maps in primary auditory cortex of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1978;182:637–660. doi: 10.1002/cne.901820406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig TJ, Morel A. Topographic and cytoarchitectonic organization of thalamic neurons related to their targets in low-, middle-, and high-frequency representations in cat auditory cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1984;227:511–539. doi: 10.1002/cne.902270405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig TJ, Morel A. Tonotopic organization in lateral part of posterior group of thalamic nuclei in the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1985a;53:836–851. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.3.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig TJ, Morel A. Tonotopic organization in ventral nucleus of medial geniculate body in the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1985b;53:309–340. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen PHS, Sun X, Chen QC. An electrophysiological study of neural pathways for corticofugally inhibited neurons in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus of the big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus. Exp Brain Res. 2001;137:292–302. doi: 10.1007/s002210000637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins WM, Masterton RB. Sound localization: effects of unilateral lesions in central auditory system. J Neurophysiol. 1982;47:987–1016. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.47.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Powell TP. An anatomical study of converging sensory pathways within the cerebral cortex of the monkey. Brain. 1970;93:793–820. doi: 10.1093/brain/93.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Burton H, Saper CB, Swanson LW. Midbrain, diencephalic and cortical relationships of the basal nucleus of Meynert and associated structures in primates. J Comp Neurol. 1976;167:385–420. doi: 10.1002/cne.901670402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamke MR, Brown M, Irvine DRF. Origin and immunolesioning of cholinergic basal forebrain innervation of cat primary auditory cortex. Hear Res. 2005;206:89–106. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharazia VN, Phend KD, Weinberg RJ, Rustioni A. Excitatory amino acids in corticofugal projections: microscopic evidence. In: Conti F, Hicks TP, editors. Excitatory Amino Acids and the Cerebral Cortex. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1996. pp. 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kipps KA, Larue DT, Winer JA. Reciprocal connections between the inferior colliculus and the central gray. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2005;30:164.110. [Google Scholar]

- Kisvárday Z, Beaulieu C, Eysel U. Network of GABAergic large basket cells in cat visual cortex (area 18): implication for lateral disinhibition. J Comp Neurol. 1993;327:398–415. doi: 10.1002/cne.903270307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisvárday ZF, Ferecskò AS, Kovács K, Buzás P, Budd JML, Eysel U. One axon-multiple functions: specificity of lateral inhibitory connections by large basket cells. J Neurocytol. 2002;31:255–264. doi: 10.1023/a:1024122009448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobler JB, Isbey SF, Casseday JH. Auditory pathways to the frontal cortex of the mustache bat, Pteronotus parnellii. Science. 1987;236:824–826. doi: 10.1126/science.2437655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Winer JA. Principles governing auditory forebrain connections. Cerebral Cort. 2005;15:1804–1814. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Schreiner CE, Imaizumi K, Winer JA. Tonotopic and heterotopic projection systems in physiologically defined auditory cortex. Neuroscience. 2004a;128:871–887. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CC, Imaizumi K, Schreiner CE, Winer JA. Concurrent tonotopic processing streams in auditory cortex. Cerebral Cort. 2004b;14:441–451. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellott JG, Larue DT, Winer JA, Lomber SG. Projections of the posterior (PAF) auditory field to the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (AES) contributing to sound localization in the cat. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2004;29:529. [Google Scholar]

- Metherate R, Kaur S, Kawai H, Lazar R, Liang K, Rose HJ. Spectral integration in auditory cortex: mechanisms and modulation. Hearing Res. 2005;206:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks JC, Zook JM. Intrinsic organization of the cat’s medial geniculate body identified by projections to binaural response-specific bands in the primary auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 1983;3:203–225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-01-00203.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Escabí MA, Read HL, Schreiner CE. Spectrotemporal receptive fields in the lemniscal auditory thalamus and cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:516–527. doi: 10.1152/jn.00395.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani A, Shimokouchi M. Neuronal connections in the primary auditory cortex: an electrophysiological study in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1985;235:417–429. doi: 10.1002/cne.902350402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani A, Shimokouchi M, Itoh K, Nomura S, Kudo M, Mizuno N. Morphology and laminar organization of electrophysiologically identified neurons in primary auditory cortex in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1985;235:430–447. doi: 10.1002/cne.902350403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moucha R, Pandya PK, Engineer ND, Rathbun DL, Kilgard MP. Background sounds contribute to spectrotemporal plasticity in primary auditory cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2005;162:417–427. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-2098-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders WHAM, Robertson D. Evidence for direct cortical innervation of medial olivocochlear neurones in rats. Hear Res. 2000;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff WD, Diamond IT, Casseday JH. Behavioral studies of auditory discrimination: Central nervous system. In: Keidel WD, Neff WD, editors. Handbook of Sensory Physiology, volume V, part 2, Auditory System, Anatomy, Physiology (Ear) Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1975. pp. 307–400. [Google Scholar]

- Olazábal UE, Moore JK. Nigrotectal projection to the inferior colliculus: horseradish peroxidase, transport and tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemical studies in rats, cats, and bats. J Comp Neurol. 1989;282:98–118. doi: 10.1002/cne.902820108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perales M, Winer JA, Prieto JJ. Focal projections of cat auditory cortex to the pontine nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497:959–980. doi: 10.1002/cne.20988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Harriman KM. Enigmatic bipolar cell of rat visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1988;267:409–432. doi: 10.1002/cne.902670310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollok B, Schnitzler I, Stoerig P, Mierdorf T, Schnitzler A. Image-to-sound conversion: experience-induced plasticity in auditory cortex of blindfolded adults. Exp Brain Res. 2005:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poremba A, Saunders RC, Crane AM, Cook M, Sokoloff L, Mishkin M. Functional mapping of the primate auditory system. Science. 2003;299:568–572. doi: 10.1126/science.1078900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto JJ, Winer JA. Layer VI in cat primary auditory cortex (AI): Golgi study and sublaminar origins of projection neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1999;404:332–358. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990215)404:3<332::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto JJ, Peterson BA, Winer JA. Laminar distribution and neuronal targets of GABAergic axon terminals in cat primary auditory cortex (AI) J Comp Neurol. 1994a;344:383–402. doi: 10.1002/cne.903440305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto JJ, Peterson BA, Winer JA. Morphology and spatial distribution of GABAergic neurons in cat primary auditory cortex (AI) J Comp Neurol. 1994b;344:349–382. doi: 10.1002/cne.903440304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauschecker JP, Tian B. Mechanisms and streams for processing of “what” and “where” in auditory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11800–11806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read HL, Winer JA, Schreiner CE. Modular organization of intrinsic connections associated with spectral tuning in cat auditory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8042–8047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131591898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reale RA, Imig TJ. Auditory cortical field projections to the basal ganglia of the cat. Neuroscience. 1983;8:67–86. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanski LM, LeDoux JE. Information cascade from primary auditory cortex to the amygdala: corticocortical and corticoamygdaloid projections of temporal cortex in the rat. Cerebral Cort. 1993;3:515–532. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.6.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanski LM, Bates JF, Goldman-Rakic PS. Auditory belt and parabelt projections to the prefrontal cortex in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1999;403:141–157. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990111)403:2<141::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña E, Feliciano M, Mugnaini E. Distribution of descending projections from primary auditory neocortex to inferior colliculus mimics the topography of intracollicular projections. J Comp Neurol. 1996;371:15–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960715)371:1<15::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR, Coomes DL. Projections from the auditory cortex to the superior olivary complex in guinea pigs. Euro J Neurosci. 2004;19:2188–2200. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR, Coomes DL. Auditory cortical projections to the cochlear nucleus in guinea pigs. Hearing Res. 2005;199:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner CE. Functional organization of the auditory cortex: maps and mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1992;2:516–521. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90190-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner CE, Cynader MS. Basic functional organization of second auditory cortical field (AII) of the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1984;51:1284–1305. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.6.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner CE, Read HL, Sutter ML. Modular organization of frequency integration in primary auditory cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:501–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder CE, Lindsley RW, Specht C, Marcovici A, Smiley JF, Javitt DC. Somatosensory input to auditory association cortex in the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1322–1327. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller G, Covey E, Casseday JH. Auditory pontine grey: connections and response properties in the horseshoe bat. Euro J Neurosci. 1991;3:648–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller G, Fischer S, Schweizer H. Significance of the paralemniscal tegmental area for audio-motor control in the moustached bat, Pteronotus p. parnellii: the afferent and efferent connections of the paralemniscal area. Euro J Neurosci. 1997;9:342–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. On the actions that one nerve cell can have on another: distinguishing “drivers” from “modulators”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7121–7126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinonaga Y, Takada M, Mizuno N. Direct projections from the non-laminated divisions of the medial geniculate nucleus to the temporal polar cortex and amygdala in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1994;340:405–426. doi: 10.1002/cne.903400310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Populin LC. Fundamental differences between the thalamocortical recipient layers of the cat auditory and visual cortices. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:508–519. doi: 10.1002/cne.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker GC, Harrington IA, Macpherson EA, Middlebrooks JC. Spatial sensitivity in the dorsal zone (area DZ) of cat auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:1267–1280. doi: 10.1152/jn.00104.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BE, Meredith MA. The Merging of the Senses. MIT Press; Cambridge: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M. Thalamic substrates and disturbances in states of vigilance and consciousness in humans. In: Steriade M, Jones EG, McCormick DA, editors. Thalamus, volume II, Experimental and Clinical Aspects. Elsevier Science Ltd; Amsterdam: 1997. pp. 721–742. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter ML, Loftus WC. Excitatory and inhibitory intensity tuning in auditory cortex: evidence for multiple inhibitory mechanisms. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2629–2647. doi: 10.1152/jn.00722.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Petrovich GD. What is the amygdala? Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa AEP, Rouiller EM, Simm GM, Zurita P, de Ribaupierre Y, de Ribaupierre F. Corticofugal modulation of the information processing in the auditory thalamus of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1991;86:506–517. doi: 10.1007/BF00230524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace MN, Kitzes LM, Jones EG. Chemoarchitectonic organization of the cat primary auditory cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1991;86:518–526. doi: 10.1007/BF00230525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA. The pyramidal cells in layer III of cat primary auditory cortex (AI) J Comp Neurol. 1984;229:476–496. doi: 10.1002/cne.902290404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA. The functional architecture of the medial geniculate body and the primary auditory cortex. In: Webster DB, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research, volume 1, The Mammalian Auditory Pathway: Neuroanatomy. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1992. pp. 222–409. [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA. Three systems of descending projections to the inferior colliculus. In: Winer JA, Schreiner CE, editors. The Inferior Colliculus. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2005. pp. 231–247. [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA. Decoding the auditory corticofugal systems. Hearing Res. 2006;212:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Morest DK. The medial division of the medial geniculate body of the cat: implications for thalamic organization. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2629–2651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02629.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Prieto JJ. Layer V in cat primary auditory cortex (AI): cellular architecture and identification of projection neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2001;434:379–412. doi: 10.1002/cne.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Schreiner CE. The central auditory system: a functional analysis. In: Winer JA, Schreiner CE, editors. The Inferior Colliculus. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2005. pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Larue DT, Huang CL. Two systems of giant axon terminals in the cat medial geniculate body: convergence of cortical and GABAergic inputs. J Comp Neurol. 1999;413:181–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Diehl JJ, Larue DT. Projections of auditory cortex to the medial geniculate body of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 2001;430:27–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Larue DT, Diehl JJ, Hefti BJ. Auditory cortical projections to the cat inferior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1998;400:147–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer JA, Lee CC, Imaizumi K, Schreiner CE. Challenges to a neuroanatomical theory of forebrain auditory plasticity. In: Syka J, Merzenich MM, editors. Plasticity of the Central Auditory System and Processing of Complex Acoustic Signals. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2005. pp. 109–127. [Google Scholar]

- Witter MP, Groenewegen HJ. Connections of the parahippocampal cortex in the cat. III. Cortical and thalamic efferents. J Comp Neurol. 1986;252:1–31. doi: 10.1002/cne.902520102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong D, Kelly JP. Differentially projecting cells in individual layers of the auditory cortex: a double-labeling study. Brain Res. 1981;230:362–366. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ED, Nelken I, Conley RA. Somatosensory effects on neurons in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:743–765. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]