Abstract

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is comprised of uniquely differentiated brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC). Oftentimes, it is of interest to replicate these attributes in the form of an in vitro model, and such models are widely used in the research community. However, the BMEC used to create in vitro BBB models de-differentiate in culture and lose many specialized characteristics. These changes are poorly understood at a molecular level, and little is known regarding the consequences of removing BMEC from their local in vivo microenvironment. To address these issues, suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) was used to identify 25 gene transcripts that were differentially-expressed between in vivo and in vitro BMEC. Genes affected included those involved in angiogenesis, transport and neurogenesis, and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) verified transcripts were primarily and significantly downregulated. Since this panel of genes represented those BMEC characteristics lost upon culture, we used it to assess how culture manipulation, specifically BMEC purification and barrier induction by hydrocortisone, influenced the quality of in vitro models with reference to the quantitative in vivo gene panel. Puromycin purification of BMEC elicited minimal differences compared with untreated BMEC as assessed by qPCR. In contrast, qPCR-based gene panel analysis after induction with hydrocortisone indicated a modest shift of 10 of 23 genes towards a more “in vivo-like” gene expression profile, which correlated with improved barrier phenotype. Genomic analysis of BMEC de-differentiation in culture has thus yielded a functionally diverse set of genes useful for comparing the in vitro and in vivo BBB.

Keywords: blood-brain barrier, genomics, in vitro BBB model, puromycin, hydrocortisone, endothelial cell

Introduction

The microvessels within the brain are comprised of specialized endothelial cells (EC) that display distinct attributes as compared to the EC found throughout the majority of the body. A single layer of tightly adjoined brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC) form the lumen of capillaries and effectively blocks the free diffusion of solutes between the blood and the brain. The impermeable nature of brain microvessels has resulted in them being called the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Although the BBB possess barrier properties, it is also endowed with selective transport systems that provide the brain with necessary nutrients. In addition, BMEC interact intimately with other brain cells of the neurovascular unit and hence can act as mediators between blood and brain. As a result of these functional attributes, the BBB plays an important role in a number of neurological diseases and hampers drug delivery efforts by preventing access to the brain.

The study of these and other aspects of the BBB can be facilitated by in vitro models. Such models often consist of a monolayer of BMEC grown on a porous membrane, effectively dividing a culture chamber into two compartments, representing the blood and brain. However, data generated from in vitro systems has to be carefully interpreted since cultured BMEC tend to lose many of their in vivo characteristics, and it is unclear to what extent the de-differentiation is occurring. A good deal of this de-differentiation has been attributed to the removal of BMEC from their microenvironment within the brain. In addition to the barrier-forming BMEC, astrocytes, neurons and pericytes are intimately associated with the microvessels and are responsible for inducing various aspects of the BBB phenotype. As a result, astrocytes and their conditioned medium have been shown to increase gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) activity, tight junction complexity, and barrier properties in cultured BMEC (Rubin et al. 1991). Neurons co-cultured with BMEC increased GGT activity and decreased the flux of dopamine through a BMEC monolayer (Tontsch and Bauer 1991). Less data exist that describe the exact influence of pericytes on BMEC, but they can improve barrier properties. In addition, soluble factors have been shown to improve in vitro BBB model properties. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) (Rubin et al. 1991) and glucocorticoids, such as hydrocortisone (HC) (Calabria et al. 2006; Hoheisel et al. 1998) and dexamethasone (Grabb and Gilbert 1995), have been successful in partially reinstating barrier properties for in vitro BMEC. Another important component of the in vivo microenvironment is blood flow and associated shear stress. Recent genomic studies employing a dynamic in vitro BBB have demonstrated that flow regulates glucose metabolism and the oxidative environment of the BMEC (Desai et al. 2002; Marroni et al. 2003). Unfortunately, the BBB properties of in vitro models continue to fall short of their in vivo counterpart despite the aforementioned enhancements.

The loss of in vivo BBB characteristics is often assessed by monitoring properties such as transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER), small molecule permeability, enzyme activity, and transporter expression. TEER is a useful technique to gauge the barrier properties of in vitro BBB models. The TEER in cultured BMEC monocultures is often 100 Ω×cm2 or lower (Calabria et al. 2006; Rubin et al. 1991), well below the value of nearly 1500 Ω×cm2 observed in the brain (Butt et al. 1990). Transcellular permeability to small molecule tracers such as fluorescein and sucrose can also yield valuable information regarding barrier integrity. While barrier properties are an oft-used measure to assess the characteristics of in vitro BBB models, several morphological and biochemical criteria have also been employed. The quality of the tight junctions has been evaluated by monitoring the expression levels and localization of various junctional proteins, such as zonula occluden, occludin, and claudin-5 (Calabria et al. 2006; Forster et al. 2005). Enzymatic activities such as those of GGT and alkaline phosphatase are also sometimes evaluated. Finally, the expression levels of BBB-resident transporters such as glucose transporter GLUT-1 (Boado et al. 1994) and the efflux transporter p-glycoprotein have been investigated (Gaillard et al. 2000). Taken together, the effects of culture manipulation and refinement on in vitro BBB model quality are often evaluated using a small number of discrete phenotypic and molecular characteristics, but from these measurements alone it is difficult to determine the magnitude of departure from the in vivo situation.

Thus, we have chosen to use a global profiling technique to simultaneously measure multiple BBB attributes in a single experiment to answer questions regarding the extent of BMEC de-differentiation in culture. While many studies have used genomics and other global profiling techniques to investigate how the introduction of inductive factors, inductive cells, and flow can affect BMEC characteristics in side-by-side culture comparisons (Calabria and Shusta 2006; Marroni et al. 2003), little has been done to link the findings to the in vivo transcriptome and determine how well these changes actually reconstitute the in vivo BBB. To address this shortcoming, we used suppression subtractive hybridization to, for the first time, directly compare various in vitro situations directly to the in vivo BBB. We identified a host of BMEC genes whose expression levels were dramatically changed when comparing the in vivo and in vitro BBB, many of which had not previously been shown to be altered upon in vitro culture. The resulting gene panel, representing the differences between in vivo and in vitro gene expression, was then utilized to evaluate effects of puromycin purification on BMEC. The expression profiles indicate that puromycin treatment is a useful method to obtain purified BMEC in culture without dramatically altering gene expression. Finally, hydrocortisone induction of BMEC was investigated using the gene panel, and this treatment was successful in partially restoring barrier properties and the in vivo gene expression profile.

Materials and methods

Isolation of rat brain microvessels for mRNA recovery

Brains were removed from male rats (220-250 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and stored in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) on ice. The remainder of the isolation took place in a cold room at 4°C. The meninges were removed and the cortices were dissected away from the surrounding tissue. The cortices were homogenized using a Dounce tissue grinder and homogenized material was filtered through a 210 mm nylon mesh to remove larger vessels. The flow-through was centrifuged in a 20% w/v dextran solution at 5000 × g for 15 min at 4°C in a swinging bucket rotor. The fatty top layer was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in DMEM. This solution, primarily containing microvessels and red blood cells, was filtered through a 44 μm nylon mesh. The microvessels retained on the nylon mesh were washed thoroughly with DMEM and were free of adjoining material when examined by microscopy. These microvessel preparations were then used for poly A+ RNA isolation as described below.

Isolation and culture of rat brain microvascular endothelial cells

An enzymatic isolation strategy was performed as previously described to isolate BMEC for in vitro culture (Calabria et al. 2006). Briefly, brain cortices were obtained from male rats (220-250 g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and digested in a mixture of 0.7 mg/mL type 2 collagenase and 39 U/mL DNase I (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ, USA) in DMEM for 1.25 h at 37°C. A microvessel enriched pellet was obtained by re-suspending the digested material in a 20% w/v bovine serum albumin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and DMEM solution and centrifuging at for 8 min at 1,000 × g and 4°C in a swinging bucket rotor. This pellet was further digested in a solution of 1 mg/mL collagenase/dispase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and 39 U/mL DNase I in DMEM for 1 h at 37°C. Purified microvessels were then isolated using a continuous 33% Percoll (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) gradient and the cells were plated onto collagen IV/fibronectin-coated tissue culture plates or 0.4 mm polyester filters (Corning, Acton, MA, USA). Culture medium contained DMEM with 20% v/v bovine platelet-poor plasma derived serum (PDS) (Biomedical Technologies Inc., Stoughton, MA, USA), 1 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis IN, USA), 1 mg/mL heparin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and an antibiotic-antimycotic solution (100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA). Unless otherwise noted, cultures were treated for the first two days in vitro (DIV) with 4 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) to remove contaminating cell types. Culture medium was changed within 24 h of initial plating and every 2-3 days thereafter. Cultures were maintained in a 37°C incubator under humidified 5% CO2/95% air. Transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured using an EVOM voltohmmeter (World Precision Instruments, Saratosa, FL, USA) as previously described (Calabria et al. 2006).

For hydrocortisone induction experiments, BMEC were cultured on Transwell filters as described above for 3.5 DIV before switching to a serum-free medium containing a 1:1 ratio by volume of DMEM and Ham's F12 nutrient mixture, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 550 nM hydrocortisone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). BMEC were treated for 24 h (4.5 DIV total) before isolating mRNA.

Isolation of poly A+ RNA

Poly A+ RNA was isolated from freshly isolated rat brain microvessels or from cultured rat brain microvessel endothelial cells (BMEC) using the MicroPoly(A)Purist™ mRNA purification kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The yield of poly A+ RNA from microvessels was 150 ng per rat brain and from cultured BMEC, yield was 90 ng/cm2. The integrity of the mRNA samples used for the suppression subtractive hybridization procedure was confirmed by actin Northern blotting.

Immunocytochemistry and quantitative analysis of culture purities

Primary antibodies were incubated with BMEC at 20°C for 1 h. Antibodies used were rabbit anti-human von Willebrand factor (14 μg/mL; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), rabbit anti-cow glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (11 μg/mL; DAKO Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA), mouse anti-alpha actin (2 μg/mL; American Research Products, Belmont, MA, USA), and mouse anti-rat prolyl-4-hydroxylase beta (10 μg/mL; Acris Antibodies GmbH, Hiddenhausen, Germany). Secondary antibodies (Texas Red goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody, 2 μg/mL; Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse IgG antibody, 2 μg/mL; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) were incubated with primary antibody labeled samples for 1 h at 20°C. The nuclear stain 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was added to the wells for 5 min at 20°C at a concentration of 300 nM (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Photographs were acquired using an Olympus fluorescence microscope coupled with a Diagnostic Instruments Inc. camera controlled by MetaVue Version 5.0r1 software. Counting was carried out after overlaying von Willebrand factor, anti-alpha actin, and DAPI nuclear stain images from the same field in Adobe Photoshop Elements 2.0. Percentage values of culture purity were calculated by using the number of alpha-actin positive cells, unstained cells and the total number of cells (DAPI stain) in each image. Unstained cells were designated as non-endothelial due to their lack of von Willebrand factor staining. Thus, % EC = (total cells - alpha-actin positive cells - unstained cells)/total cells * 100%. At minimum, 2000 cells were counted for each labeling condition. Due to the high purity of puromycin-treated cultures, entire wells were evaluated to determine culture purity.

Suppression subtractive hybridization

Suppression subtractive hybridization was performed as previously described (Li et al. 2001; Shusta et al. 2002) using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-select cDNA subtraction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). First, mRNA samples were treated by the TURBO DNA-free™ kit to remove genomic DNA (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The brain microvessel and cultured BMEC mRNA levels were then normalized by spectrophotometry. The freshly isolated brain microvessel poly A+ RNA was then used to produce 2.0 μg of tester cDNA, and the subtraction procedure was completed using driver cDNA from cultured BMEC mRNA (to determine gene transcripts down-regulated in culture). The subtraction was also performed in the reverse direction, with the cultured BMEC mRNA used to create 2.0 μg of tester cDNA and the freshly isolated rat brain microvessel mRNA used to produce driver cDNA (to determine gene transcripts up-regulated in culture). The SSH-PCR products were cloned into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and the resultant library of cloned cDNA fragments expanded in E. coli XL1-Blue supercompetent cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Differential Southern blot hybridization was employed in a 96-well format to identify positive clones as previously described (Li et al. 2001; Shusta et al. 2002). Briefly, bacterial clones were blotted using subtracted and unsubtracted probes to enable a comparison of relative hybridization intensity (data not shown). Clones that hybridized to tester probes and not to driver probes were defined as differentially-expressed and selected for sequencing.

Isolated clones were sequenced using the standard M13 forward primer at the University of Wisconsin's Comprehensive Cancer Research Center (Madison, WI, USA). The BLAST program (NCBI, NIH) was utilized to determine gene identity using the nr database. Reported in Table 3 are the accession numbers and gene names for the corresponding matches to rat sequences. For some genes, rather than report accession number matches to known, validated mRNA from other species, we instead reported accession numbers (XM_ prefix) for the homologous rat genes that, to date, were annotated as “predicted”.

Table 3.

Panel of genes differentially-expressed upon BMEC culture.

| Gene Name | Gene Symbol | Accession no. | Expression Categorya (Reference) | Function | ΔΔCtb | Fold Changee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down-regulated in vitro | ||||||

| FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 | FLT1 | NM_019306 | 1 (Fischer et al. 1999) | Angiogenesis/Vascular | -4.4 ± 0.9 | -21 |

| Natriuretic peptide receptor 2 | NPR2 | NM_053838 | 3 (Suga et al. 1992) | Angiogenesis/Vascular | -3.2 ± 0.8 | -9 |

| Reversion-inducing-cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs | RECK | XM_233371 | 3 (Oh et al. 2001) | Angiogenesis/Vascular | -3.7 ± 0.9 | -13 |

| Myosin regulatory light chain 9 (predicted), MYRL2, MLC2 | MYL9 | XM_215905 | 2 (Hiyama et al. 2005; Li et al. 2002) | Contractile Activity | -4.9 ± 1.2 | -30 |

| AGENCOURT_27531282 NIH_MGC_254 cDNA clone | cDNA clone | CO396851 | 4 (none) | EST | -4.3 ± 0.7 | -20 |

| Blood-brain barrier specific cDNA library Rattus norvegicus cDNA clone | LKH14 | BM382806 | 1 (Li et al. 2002) | EST | -5.2d | -37 |

| Cdc42 GTPase-activating protein | CDGAP | XM_221438 | 3 (Hiyama et al. 2005) | GTPase Activator | -2.3 ± 0.7 | -5 |

| Carboxypeptidase E | CPE | NM_013128 | 2 (Enerson and Drewes 2006; Reznik et al. 1998) | Hormone Processing | -4.4 ± 0.2 | -21 |

| Interferon (alpha and beta) receptor 1 | IFNAR1 | XM_213649 | 2 (Enerson and Drewes 2006; Gomez and Reich 2003) | Immune | -4.4 ± 0.9 | -21 |

| Cleavage and polyadenylation specific factor 2d | CPSF2 | XM_216766 | 3 (Hiyama et al. 2005) | mRNA Processing | -0.7 ± 0.4c | 0 |

| Cystatin C | CST3 | NM_012837 | 2 (Enerson and Drewes 2006; Wasselius et al. 2004) | Neurogenesis | -6.9 ± 1.2 | -120 |

| Integral membrane protein 2B | ITM2B | NM_001006963 | 2 (Enerson and Drewes 2006; Hendrickx et al. 2004) | Neurogenesis | -4.2 ± 0.3 | -18 |

| N-myc downstream regulated gene 2 | NDRG2 | NM_133583 | 2 (Enerson and Drewes 2006; Hendrickx et al. 2004) | Neurogenesis | -4.6d | -24 |

| Semaphorin 3G | SEMA3G | AB190259 | 3 (Hiyama et al. 2005) | Neurogenesis | -4.2 ± 1.1 | -18 |

| Sparc/osteonectin, cwcv and kazal-like domains proteoglycan 2, testican-2 | SPOCK2 | XM_342134 | 1 (Nakada et al. 2003) | Neurogenesis | -9.2 ± 0.6 | -590 |

| ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting, alpha 2 polypeptide | ATP1A2 | NM_012505 | 1 (Betz et al. 1980) | Transport | -11.0d | -2000 |

| Blood-brain barrier specific anion transporter, BSAT1 | OATP14 | AF306546 | 1 (Li et al. 2001) | Transport | -11.4 ± 1.5 | -2700 |

| Phospholipid transfer protein | PLTP | XM_215939 | 2 (Day et al. 1994; Enerson and Drewes 2006) | Transport | -4.6 ± 1.6 | -24 |

| cis-Golgi p28, GS28, GOS-28 | GOSR1 | RNU49099 | 3 (Hendrickx et al. 2004) | Transport | -2.9 ± 1.0 | -7 |

| Chromosome 3 contig | none | NW_047658 | 5 (none) | Unknown | NT | |

| Chromosome 7 contig | none | NW_047774 | 5 (none) | Unknown | NT | |

| Up-regulated in vitro | ||||||

| Apelin, AGTRL1 ligand | APLN | NM_031612 | 3 (Kleinz and Davenport 2004) | Angiogenesis/Vascular | 6.1 ± 0.6 | 69 |

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 7, MCP-3 | CCL7 | NM_001007612 | 3 (Sun et al. 2005) | Inflammation | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 4 |

| Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 1, PAI-1 | SERPINE 1 | NM_012620 | 1 (Tran et al. 1998) | Angiogenesis/Vascular | 7.3 ± 2.0 | 160 |

| Thrombospondin 1 | TSP1 | AF309630 | 1 (Sheibani and Frazier 1998) | Angiogenesis/Vascular | 8.6 ± 0.3 | 390 |

| BBB Control Genes | ||||||

| Facilitated glucose transporter, member 1, Slc2a1 | GLUT-1 | NM_138827 | 1 (Boado et al. 1994) | Transport | -5.3 ± 0.4 | -39 |

| multidrug resistance protein 1a, Pgy1 | MDR1A | AF257746 | 1 (Gaillard et al. 2000) | Transport | -3.8 ± 1.1 | -14 |

| Transferrin receptor | TfR | M58040 | 1 (Jefferies et al. 1984) | Transport | -3.2 ± 0.9 | -9 |

NT = Not tested.

Expression category 1: Gene transcripts expressed by BMEC. Category 2: Gene transcripts expressed by peripheral EC and linked to BMEC by genomics experiments. Category 3: Gene transcripts expressed by peripheral EC. Category 4: Gene transcripts not previously shown to be expressed by EC. Category 5: Unknown open reading frame.

ΔΔCt = ΔCt(in vivo)-ΔCt(untreated in vitro) values were calculated as described in the methods section. A value of zero indicates that there is no difference between the gene expression levels of the two samples. Negative values imply lower expression in culture than in vivo samples, and positive values imply higher expression in culture. ΔΔCt values are the mean ± standard deviation of at least two independent experiments with independent mRNA samples. All values are statistically significant (p<0.05) as determined by unpaired Student's t-test unless otherwise specified.

CPSF2 was the only SSH-derived gene that was not truly differentially expressed as assessed by qPCR. Expression levels were unchanged under all conditions examined.

Gene detected by qPCR, but as a result of low expression levels in cultured BMEC samples and PCR artifacts at high cycle numbers, absolute quantitation was not possible. The numbers reported therefore represent the minimum amount by which expression was downregulated.

Quantiative ΔΔCt values were converted to approximate fold differences in gene expression by assuming 100% primer efficiency and using the equation 2ΔΔCt. A value of zero indicates that there is no difference between the gene expression levels of the two samples. Negative values imply lower expression in culture than in vivo samples, and positive values imply higher expression in culture.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed using a Bio-Rad iCycler thermal cycler and an iScript one-step qPCR kit with SYBR Green according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Each reaction was carried out with 1 ng of mRNA obtained from freshly isolated brain microvessels or from BMEC cultures. Messenger RNA samples were treated by the TURBO DNA-free™ kit to remove genomic DNA (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Gene-specific primers are shown in Table 1 and were designed using PerlPrimer software version 1.1.13. Three control genes included in the analysis encode glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1), p-glycoprotein (P-gp; MDR1A), and the transferrin receptor (TfR).

Table 1.

Quantitative PCR primers.

| Gene Symbol | Primers |

|---|---|

| APLN | F: TCTAAAGCAGGATTGAAGGG R: TCATCTGTGGAGTAAAGAGAC |

| ATP1A2 | F: CATCATATCAGAGGGTAACGA R: GATTGACTTGACTCACAGGA |

| CDGAP | F: GGGTTACGCTTAGGAATAAA R: CTTGTTGAAGTCTCTAGCCT |

| cDNA clone | F: TTTATGCTCCTCGACAGAAC R: TTGATGGCTCACTGACTAAC |

| CPE | F: AAACTCCCTCATCAACTACC R: GACAAACCCTTTAACACCTC |

| CPSF2 | F: TCAAGGATGATGGAGAAGAC R: TATGACACTGGAATCTGAAGG |

| CST3 | F: CTTGTGGCTGGAATAAACTA R: AATTTGTCTGGGACTTGGTA |

| FLT1 | F: CACTACAACCACTCCAAAGA R: TTCTGTTTCCTATGTTGCTG |

| GOSR1 | F: TGTTTGGGTCTGGTTAAGTC R: TTCTCGCAATTTCATCAGTC |

| IFNAR1 | F: TTCTGTCTTCCTGTTCTTACC R: AAAGCGGATGTTCTAAACTG |

| ITM2B | F: TCTAAGTGTGGTGTCTTTGG R: AGCAAATCTTATCTAGGAACCC |

| LKH14 | F: CAAGTAGCTTCTGGTTTCCT R: GTAGGCAGCTTATTCAAGGAT |

| MCP-3 | F: GTGAAATAGTCGCTCCTAAG R: CATTCAAATCACACCAAAGT |

| MYL9 | F: CCCAGATCCAGGAGTTTAAG R: GTAGGTCCTCCTTGTCAATG |

| NPR2 | F: CGAACTTATTGGCTCTTAGGA R: ATTGTCTGCTTGGGATTTAC |

| NDRG2 | F: GAGCATACATTCTGTCACGA R: GTTGATGAGAACAAGACCTTC |

| OATP14 | F: GATGTTCCCAAATGTTTCTG R: GTATGCCACCTAGAGATAATG |

| PLTP | F: CAAATGATCTGGACATGCTT R: AGAACAATGCTCCCAAAGTA |

| RECK | F: AAGTATCTGTGAGTTCCTGT R: AGGTATGTGTCCAGAGGTATA |

| SEMA3G | F: TAGTGGCATTTGGACTAAATCT R: TACTTCCCTAGAGGACCTTG |

| SERPINE1 | F: CGCCTTGTGTTATTTCAGAG R: CCTTTCTTTCACGCTTTCAA |

| SPOCK2 | F: CTTTGCTGTGGTCTTTATCTG R: GTGTAGAGTGAACTTGTTTCC |

| TSP1 | F: ACAACTGTCCATTCCATTAC R: CCCACATCATCTCTGTCATAG |

| BBB Control Genes | |

| GLUT-1 | F: GAGACCTCTTCCAAACTGAC R: TTCTTCTGGACTTCATTGCT |

| MDR1A | F: ATCAACTCGCAAAAGCATCC R: AATTCAACTTCAGGATCCGC |

| TfR | F: TATGGGTCTAAGTCTACAATGG R: TTAGTCTAGAAGTAGCACGG |

| Reference Genes | |

| β-actin | F: GCTACAGCTTCACCACCACA R: GCCATCTCTTGCTCGAAGTC |

| GAPDH | F: CCTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTAT R: AGCCCAGGATGCCCTTTAGT |

| RPLP0 | F: AAGACCTCTTTCTTCCAAGC R: ACATCGCTCAGGATTTCAAT |

Gene expression was normalized solely to the reference gene β-actin, after an initial study where gene expression levels were normalized to β-actin or two other commonly used reference genes, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 (RPLP0) yielded nearly identical values for all biological samples examined. Delta-delta cycle threshold values (ΔΔCt) were calculated according to the method developed by PE Applied Biosystems (Perkin Elmer). The ΔΔCt value is a difference in gene expression levels between two samples as measured by PCR cycles. The cycle threshold (Ct) was defined as the PCR cycle where fluorescence reached a defined threshold value. The normalized delta cycle threshold was calculated by subtracting the gene cycle threshold value from the β-actin cycle threshold value (ΔCt = Ctβ-actin - Ctgene). Comparative gene expression between two independent samples, or delta-delta cycle threshold, was determined by subtracting the control delta cycle threshold from the sample delta cycle threshold (ΔΔCt = ΔCtsample -ΔCtcontrol). Throughout the paper, the ΔΔCt values are reported and serve as an accurate measure of differential gene expression. Where indicated, these ΔΔCt values were converted to approximate fold differences in gene expression by assuming 100% primer efficiency and using the equation 2ΔΔCt. Duplicate or triplicate data points were used to determine all delta-delta cycle threshold values ΔΔCt and their associated error. In addition, all results were replicated in at least two separate experiments with independently derived in vivo, in vitro, puromycin-treated, or hydrocortisone-treated mRNA samples.

Results

Preparation of in vivo and in vitro samples for genomic comparison

The first goal of this study was to identify differentially-expressed gene transcripts resulting from the removal of BMEC from the brain microenvironment. As shown in Fig. 1, this was accomplished by comparing in vivo and in vitro mRNA pools using suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH). The genomic technique yielded a gene panel representing the identity of differentially-expressed genes between in vivo and in vitro BMEC, and qPCR was used to determine the corresponding comparative gene expression level profile.

FIG. 1.

Flow chart detailing the steps performed to generate the SSH-derived gene panel. Messenger RNA was isolated from rat brain microvessels to generate a sample representing BMEC gene expression within the in vivo blood-brain barrier (BBB). Messenger RNA was also isolated from cultured brain microvascular endothelial cells to generate a sample representing BMEC gene expression in the in vitro BBB. The genomic technique suppression subtractive hybridization was used to remove commonly expressed mRNA transcripts between these two samples, and to identify those transcripts that were differentially-expressed. These differentially-expressed genes comprised a gene panel representing the molecular level differences between in vivo and in vitro BMEC. The gene panel was further employed to assess the effects of two separate culture conditions. One condition involved the purification of BMEC cultures using puromycin. The other condition examined the effects of purified BMEC barrier induction with hydrocortisone. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

The first step in this procedure was to generate the starting materials for the genomic comparison (Fig. 1). Rat brain microvessels were isolated using a mechanical homogenization procedure that enabled the sample to be maintained at 4°C at all times to prevent significant changes in the transcriptome during the isolation procedure. Care was taken to ensure that this procedure yielded a very pure microvessel preparation free of adjoining material and single cells (Fig. 2A). Despite the high level of vessel purity, the brain microvessel preparation did contain pericytes in addition to BMEC as a result of the practical consequence that both cell types are enclosed within a common basement membrane. Small numbers of smooth muscle cells were also inevitably present on precapillary arterioles. However, the great majority of the contaminating fraction was pericytes, since their cellular abundance in vivo is approximately one pericyte for every 3-5 endothelial cells (Pardridge 2001). The in vivo cellular population was thus approximately 75-83% BMEC. The in vivo BBB mRNA sample isolated from these microvessels therefore contained gene transcripts from multiple cellular origins, and was an important consideration in the design of our genomics experiment as described below.

FIG. 2.

Sample preparation and validation of the suppression subtraction hybridization (SSH) procedure. (A) Purified rat brain microvessels stained with o-toluidine blue. Scale bar represents 50 μm. (B) Rat brain microvascular endothelial cells cultured for 4.0 days in vitro without puromycin treatment. Phase image was overlayed by an image of the same field immunolabeled with an antibody against α-actin (artificially colored black). Scale bar represents 50 μm. (C) Northern blotting of poly A+ RNA from freshly isolated brain microvessels (lane 1) and cultured BMEC (lane 2) using an actin probe. Bands seen at 2.1 kb correspond to β-actin and the band seen at 1.6 kb corresponds to α-actin derived from smooth muscle cells in the in vivo sample and pericytes or smooth muscle cells in the in vitro sample. (D) Verification of SSH subtraction efficiency. The GAPDH gene was amplified by PCR for the unsubtracted in vivo (lanes 1-4) and in vitro (lanes 9-12) or subtracted in vivo (lanes 5-8) and in vitro (lanes 13-16) products from the SSH procedure. The lack of significant PCR product before 33 PCR cycles in the subtracted products indicates the success of the subtraction procedure.

For the comparative in vitro sample, primary brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC) were cultured for 4.0 days in vitro (DIV) to achieve confluency. These cultures were probed for a variety of cellular markers to determine the identity and quantity of contaminating cell types, and the seeding density was tuned to achieve fractional pericyte abundance that approximated the in vivo distribution. This step was critical to ensure that the genomics analysis did not yield predominately pericyte transcripts as would be the case if pure in vitro BMEC preparations were used. The results shown in Fig. 2B and Table 2 indicate that BMEC comprised the target 69%-79% of the cell population. The primary contaminating cell type in the cultures was a-actin positive pericytes, with very small numbers of additional contaminating cell types including α-actin positive smooth muscle cells (Table 2). Poly A+ RNA was subsequently isolated from these cultures and represented the in vitro BBB sample. The quality of the in vivo and in vitro mRNA samples was analyzed by Northern blotting with an actin probe (Fig. 2C), and integrity of the mRNA was confirmed.

Table 2.

Quantitative analysis of cellular distribution in untreated BMEC cultures.

| Cell Markers | Cell Specificity | Percent Positivea |

|---|---|---|

| von Willebrand factor | Endothelium | 74±5% |

| α-actin | Pericyte | 26±5% |

| Glial fibrillary acidic protein | Astrocyte | < 1% |

| Prolyl 4-hydroxylase | Fibroblast | Not detected |

The results are the mean ± standard deviation of three culture wells from a 24-well culture plate.

Differential transcript profiling of in vivo and in vitro BMEC using SSH

In vivo and in vitro BBB mRNA samples were then compared using SSH. The subtraction was performed in both directions (in vivo minus in vitro and in vitro minus in vivo) and thus the procedure resulted in two transcript pools, one containing genes down-regulated in vitro and the other contained genes up-regulated in vitro. The success of the subtraction process was confirmed by verifying the absence of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in the subtracted pools (Fig. 2D). Subtracted gene products were then subjected to a Southern blot-based secondary screen to confirm their differentially-expressed nature (see methods for details). In total, non-exhaustive secondary screens identified 128 clones as differentially-expressed. Sequencing yielded 25 unique BMEC gene transcripts, with 21 being down-regulated and 4 being up-regulated upon in vitro culture (Table 3). Of the 21 genes down-regulated in the BMEC cultures, 17 matched known gene sequences, 2 matched rat ESTs, and 2 matched rat genomic sequence not currently annotated to contain open reading frames. All 4 of the up-regulated gene products matched known gene sequences. These differentially-regulated genes mediate a variety of cellular functions, and many have not been previously identified as having altered expression levels as a result of BMEC culture.

Validating the endothelial origin of differentially-expressed transcripts

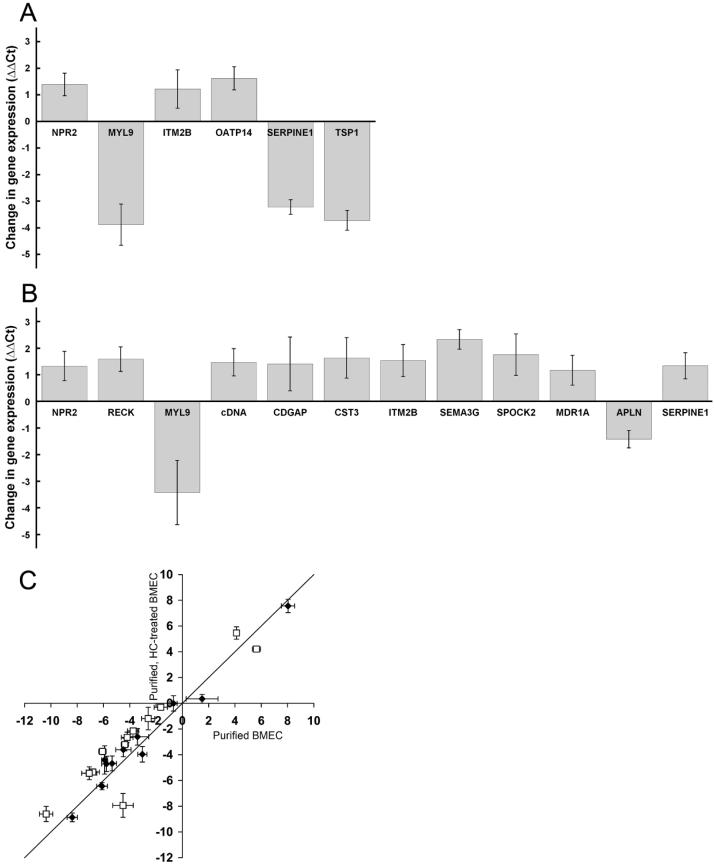

To validate the endothelial relevance of the SSH gene panel, we confirmed endothelial expression in two ways: by literature and database mining and by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) with highly purified BMEC. First, known genes and rat ESTs identified by SSH could be organized into five expression-related categories after leveraging information available both from the literature and associated datasets archived on the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO; NCBI). Seven genes have been verified to be expressed by BMEC in specific detailed investigations (ATP1A2, FLT1, LKH14, OATP14, TSP1, SERPINE1 and SPOCK2) (Expression Category 1), seven have been shown to be expressed by peripheral EC and linked to the BBB by a genomic investigation(s) (CPE, CST3, IFNAR1, ITM2B, MYL9, NDRG2 and PLTP) (Category 2), and eight have been shown to be expressed by peripheral EC (APLN, CDGAP, CPSF2, MCP-3, NPR2, P28, RECK and SEMA3G) (Category 3). One EST, a novel cDNA clone, has not previously been shown to be expressed by EC or the BBB (Category 4). The final two identified gene transcripts matched rat chromosomal sequences but did not correspond to known open reading frames (Category 5). As a further verification of BMEC transcript origin, highly purified (~100% purity by puromycin treatment) BMEC cultures were shown to express all of the genes in expression categories 1-4 by qPCR (Fig. 3 and data not shown). Thus, the pericyte normalization procedure appeared successful in generating a gene panel that was of high endothelial relevance.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of BMEC culture conditions using the gene panel and qPCR. (A) Statistically significant changes in gene expression levels between puromycin-purified (~100% BMEC) and untreated BMEC cultures (ΔΔCt, p<0.05). Gene transcripts not exhibiting statistically significant changes were excluded from the plot. (B) Statistically significant changes in gene expression levels between puromycin/hydrocortisone (HC)-treated BMEC and puromycin-treated BMEC cultures. Again, only those genes exhibiting statistically significant changes are depicted (ΔΔCt, p<0.05). (C) Comparison of gene expression levels between puromycin/HC-treated BMEC, puromycin-treated BMEC, and the in vivo BBB. Plotted are the ΔΔCt values comparing each in vitro condition to the in vivo case, with each data point representing a different gene transcript. Thus, a solid line of slope one represents equivalent gene expression levels between the two in vitro samples with reference to the in vivo case. The open squares are data points corresponding to genes with statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences in expression between the HC-treated and control culture condition, and the distance from the x-axis represents the quantitative differences in gene expression between the HC-treated BMEC and the in vivo BBB. Note that upon HC treatment, many of the open squares are shifted towards the x-axis, and hence towards in vivo gene expression levels. The solid diamonds are transcripts with statistically insignificant changes upon HC treatment, and therefore these points lie very close to the line with a slope of unity. Each value in panels A-C represents the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate biological samples. Results are representative of two independent experiments with independent mRNA samples. Throughout whole figure, positive and negative values of ΔΔCt represent genes upregulated and downregulated by indicated treatment, respectively.

Quantitative assessment of the level of differential expression

The SSH procedure resulted in the identification of a panel of genes that were differentially-regulated in BMEC when they were removed from the in vivo microenvironment and cultured. Since the SSH procedure is qualitative in nature, qPCR was employed to obtain quantitative data regarding the differences in gene regulation. Primer sets (Table 1) for 23 of the 25 gene transcripts identified by SSH (unknown open reading frame sequences were excluded) were utilized to examine relative gene expression levels. Besides the gene transcripts identified by SSH, three additional genes were added to the gene panel as controls: the glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1), p-glycoprotein (MDR1A), and the transferrin receptor (TfR). These genes were chosen based on their frequent use during in vivo and in vitro BBB characterization and because they have been previously reported to have down-regulated expression in BMEC cultures (Boado et al. 1994; Gaillard et al. 2000). Delta-delta cycle threshold (ΔΔCt) values from the in vivo and in vitro BMEC qPCR data are reported in Table 3, and the ΔΔCt values represent the quantitative differences in gene expression between the two samples in terms of a number of PCR cycles (see Materials and Methods for details). The data indicated that 18 of 23 gene products and the 3 control genes were significantly downregulated upon culture. Values of ΔΔCt for the in vivo versus in vitro comparison shown in Table 3 ranged from -11.4 to +8.6, and as a calibration, these ΔΔCt values correspond to approximate changes in fold expression levels ranging from 2700-fold downregulated to 390-fold upregulated upon BMEC culture. Only one of the SSH-identified genes (CPSF2) proved not to be reproducibly differentially-expressed between in vivo and in vitro BMEC (Table 3). The SSH gene panel therefore represents genes whose expression levels change dramatically as a result of removing BMEC from their microenvironment within the brain. In subsequent studies, the effects of different culture environments on BMEC gene expression were compared quantitatively and related back to the in vivo expression profile.

Effects of BMEC purification on the in vitro transcriptome

High purity BMEC cultures can be obtained using the protein translation inhibitor puromycin (Calabria et al. 2006; Perriere et al. 2005). Puromycin is a substrate of the efflux transporter p-glycoprotein (MDR1), which is more highly expressed in BMEC than in other contaminating cell types. The inclusion of puromycin in the culture medium therefore allows for the removal of contaminating cell types and the routine attainment of BMEC cultures with purities of 99.8% (Calabria et al. 2006). Thus, we wished to evaluate the effects of this purification method on the expression patterns within the gene panel by comparing the profiles generated by untreated versus puromycin-treated BMEC mRNA (Fig. 3A). BMEC were treated with puromycin, attained confluence after being maintained in culture for a total of 3.5 DIV, and were 99.9 ± 0.03% pure. In parallel, low purity, untreated cultures lacking puromycin (77 ± 4 % BMEC) were cultured under otherwise identical conditions for 3.5 DIV. Poly A+ RNA isolated from these cultures was subjected to qPCR with primers for 23 of the SSH-derived genes and the 3 control genes (Table 1). The ΔΔCt values resulting from puromycin treatment of BMEC indicated that 6 of the 23 genes analyzed had statistically significant changes in gene expression, and none of the 3 control genes, including MDR1, was altered. Of the 6 genes with significant differences in expression, three were down-regulated (MYL9, SERPINE1, and TSP1) as a direct result of the removal of pericytes and/or smooth muscle cells from the purified cultures. Three BMEC genes (ITM2B, NPR2, and OATP14) were upregulated upon purification, and it is important to note that these data represent true increases in BMEC gene expression and are not simply the result of the proportion of BMEC-derived mRNA being increased in the puromycin-treated case (from 77% BMEC in untreated case to ~100% BMEC in puromycin-treated case) (Fig. 3A). While subtle differences exist, the data indicates that the genomic fingerprints for untreated and puromycin-treated BMEC are quite similar.

Effects of hydrocortisone on the in vitro genomic fingerprint

Puromycin-purified BMEC cultures have previously been shown to respond optimally to hydrocortisone (HC) barrier induction (Calabria et al. 2006). While changes in the localization of several tight junction proteins have been noted (Calabria et al. 2006), little is known about the molecular level events that accompany HC induction. To gain a better understanding of how HC induces barrier properties in BMEC and to see if this treatment resulted in a more in vivo-like genotype, the gene panel expression levels were analyzed following a 24 h induction of puromycin-purified BMEC with HC. As observed previously (Calabria et al. 2006), this treatment resulted in a significantly higher TEER (139 ± 1 Ω×cm2) than control samples that were also puromycin-purified but lacking HC (38 ± 2 Ω×cm2). As shown in Fig. 3B, 12 of 23 genes had statistically significant differences in gene expression upon HC induction. The differences in the ΔΔCt values ranged from 1.2-2.3 PCR cycles (~2.3- to 5.1-fold) for the 10 upregulated genes (CDGAP, cDNA clone, CST3, ITM2B, MDR1A, NPR2, RECK, SERPINE1, SEMA3G, and SPOCK2) and 1.4-3.4 cycles (~2.70- to 10.7-fold) for the down-regulated APLN and MYL9 genes. Importantly, the changes in gene expression had the effect of moving 10 genes closer to in vivo gene expression levels in correlation with the improved barrier phenotype (Fig. 3C). Only MYL9 and SERPINE1 were differentially-regulated further from their in vivo values. Although the gene expression profile was significantly improved, the HC treatment did not restore the in vivo expression profile, and in most cases, the HC-treated BMEC expression levels were still well removed from the in vivo situation (Figure 3C, distance from the x-axis).

Discussion

By using genomics approaches, this study offers a semi-global view of changes in gene expression that occur upon removal of BMEC from the brain microenvironment and subsequent culture in vitro. Quantitative assessment of the changes in expression level indicated that the majority of the affected genes were substantially down-regulated in vitro. Moreover, affected genes included those involved in functions of high BBB importance such as transport, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis. The resultant gene panel was then used to assess the effects of two culture treatments. The first treatment of BMEC using puromycin indicated the effects of purification were minimal and could be mostly ascribed to removal of pericytes. Further treatment of purified BMEC with HC illustrated that along with a change in barrier phenotype, a fairly widespread change in genotype towards the in vivo situation was also observed. The roles of the specific genes in relation to BBB function will be discussed in more detail below.

Since microvessels represent only 0.1% of the total brain volume (Pardridge 2001), the separation of brain microvessels (BMEC) away from total brain material was required to perform accurate comparisons of in vivo and in vitro BMEC gene expression (Figure 1). In addition, the in vivo BMEC had to be isolated in such a manner that their gene expression profile was maintained. Thus, a mechanical homogenization procedure was used to obtain rat brain microvessels in an “in vivo-like” state. Although other BMEC isolation methods exist, this procedure was chosen because it maintained samples at 4°C to minimize endogenous RNase activity, required no specialized equipment, and provided relatively high yields of high quality brain microvessel mRNA with no requirement for a potentially biasing mRNA amplification step (150 ng of mRNA per rat brain). The in vitro sample used for comparisons were purposefully manipulated to contain contaminating cells, in particular pericytes. We had previously demonstrated that modulating the initial cell seeding density and the total time in culture can be used to control the percentage of contaminating cells in culture (Calabria et al. 2006). These cultures were therefore “tuned” to 69-79% BMEC, which was similar to the value found in the in vivo BMEC sample (75-83% BMEC). Normalization of the contaminating cell percentage in the in vivo and in vitro BMEC samples minimized the isolation of genes from these other cell types during the SSH procedure. As a result, the BMEC relevance of the SSH gene panel was quite high and was confirmed in several ways. First, most of the isolated genes had been previously shown to be expressed in BMEC or peripheral endothelia. Second, BMEC in highly pure cultures were shown to express all of the isolated genes. Finally, many of the genes were responsive to BMEC treatment by HC, further confirming their endothelial origin. Thus, although some of the genes may be expressed by multiple cell types at the BBB, the gene panel proved useful for evaluating BMEC function under different culture conditions.

Twenty-five genes were identified by SSH as being differentially-expressed in BMEC when these cells were removed from the brain microenvironment and cultured. Twenty-one of these clones were downregulated in vitro and four were upregulated. Quantitative PCR confirmed the differential expression of all the known genes and ESTs identified in this study except for CPSF2, whose gene expression values were not reproducibly different in culture as compared to in vivo (Table 3). The qPCR results indicated that the majority of the reported gene transcripts were not only differentially regulated, but experienced significant deviations (up to 2,700-fold) from the in vivo condition. In addition, many of the genes have not previously been identified as being differentially-expressed in BMEC cultures. The largest functional set of genes identified was related to angiogenesis and vascular functions (Table 3). One example, thrombospondin-1 (TSP1), an inhibitor of angiogenesis, is expressed by a variety of cells including BMEC (Sheibani and Frazier 1998), and was found to be upregulated in BMEC culture. Another is reversion-inducing-cysteine-rich protein with kazal motifs (RECK), which is expressed by EC, and can inhibit their migration and angiogenic properties (Oh et al. 2001), and is downregulated in cultured BMEC. A third gene, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 (FLT1), also known as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR-1), plays an important role in promoting angiogenesis and was also downregulated in vitro. Notably, two other genes were substantially downregulated and encode the transporters Na+/K+-ATPase, alpha 2 (ATP1A2) and BBB specific anion transporter (OATP14) (Betz et al. 1980; Li et al. 2001). In addition, the three control transporters, TfR, MDR1, and GLUT-1, were significantly downregulated as a result of culture. Phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) was also downregulated and has been reported to be more highly expressed at the BBB compared with liver and kidney endothelium (Li et al. 2002), where it likely functions in transferring phospholipids and antioxidants from high density lipoproteins to low density lipoproteins and endothelium (Desrumaux et al. 1999). Finally, the Golgi-associated snare (GOSR1) gene functions in the regulation of vesicle trafficking (Hay et al. 1997), and a downregulation of GOSR1 suggests there may be a general decrease in vesicular transport in cultured BMEC. Collectively, these findings are of particular importance since molecular transport is critical to BBB function.

Another subset of SSH-identified gene transcripts were of particular interest because they encode proteins that have been shown to have regulatory roles in the developing and adult CNS. Cystatin C (CysC) is an ubiquitous, secreted cysteine protease inhibitor originally identified as an abundant protein of the cerebral spinal fluid with the choroid plexus as a major site of production. This gene was down-regulated substantially upon BMEC culture, and in a previous study was identified to be one of the 25 most highly expressed transcripts at the BBB (Enerson and Drewes 2006). CysC has been reported to stimulate neural stem cell proliferation and neurogenesis in vivo (Taupin et al. 2000), in addition to promoting astrogenesis and suppressing oligodendrogenesis in vitro (Hasegawa et al. 2006), and has been linked to pathological processes such as cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral hemorrhage and Alzheimer's disease. The integral membrane protein 2b (ITM2B) was also down-regulated in vitro. ITM2B is expressed in multiple tissue types including brain, and has also been shown to be expressed in infant brain (Vidal et al. 1999) indicating a possible role in nervous system development. Peptides derived from a genetic mutant of ITM2B are found in peri-vascular amyloid deposits associated with familial British dementia (Vidal et al. 1999). Another protein potentially involved in neural cell differentiation, the N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2 (Ndrg2) (Okuda and Kondoh 1999), was downregulated to the point of the qPCR detection limit in vitro. The NDRG2 gene is part of a four member gene family whose members are involved in cell differentiation, and NDRG2 has been shown to be expressed in the embryonic ventricular zone as well as in neurogenic regions in adult brain (Okuda and Kondoh 1999). Also downregulated was sparc/osteonectin, cwcv and kazal-like domains proteoglycan 2 (SPOCK2), an extracellular protein also known as testican-2, that has functions that include regulation of protease activity (Nakada et al. 2003) and neurite outgrowth (Schnepp et al. 2005). Finally, semaphorin 3G (SEMA3G) was also identified as being downregulated in BMEC cultures and while little is known about this semaphorin isotype, it has been shown to have involvement in axonal guidance through neuropilin-2 (Taniguchi et al. 2005). All genes discussed above, except NDRG2, were shown to be expressed by a microarray study using human umbilical vein endothelial cells ((Hiyama et al. 2005), GEO database profile number GDS1760[ACCN]). Except for SEMA3G and SPOCK2, all were also linked to the BBB by a comprehensive serial analysis of gene expression study of the rat BBB (Enerson and Drewes 2006). Finally, combined with the confirmed expression of these genes by purified BMEC, these data suggest that BMEC may play an important role in the regulation of brain development and maturation, a theory that has been supported by various studies which indicate that endothelial cells can regulate neurogenesis (Shen et al. 2004). Importantly, the expression level loss of these genes indicates that the brain phenotype of in vitro BMEC is significantly altered.

The puromycin BMEC purification methodology has been shown to yield in vitro BMEC cultures that are nearly pure, and importantly, these cultures respond optimally to inducing factors like glucocorticoids and cAMP leading to increased electrical resistance and resistance to passive diffusion (Calabria et al. 2006; Perriere et al. 2005). However, to validate this approach on a more comprehensive scale, we employed the panel of differentially-expressed genes to evaluate whether or not positive or deleterious changes in gene expression resulted upon puromycin treatment. Seventeen of the 23 SSH-derived genes as well as the 3 control genes examined did not experience a significant change in gene expression as a result of the puromycin treatment. As described previously, although the BMEC expression of the MDR1 (p-glycoprotein) gene product is instrumental in the puromycin purification method, transcript levels for MDR1 were not changed by puromycin treatment (Perriere et al. 2005). The downregulation of three genes by purification (MYL9, SERPINE1, and TSP1) can be explained in large part by the removal of contaminating cell types from the cultures. Of the 6 gene transcripts that experienced significant changes due to puromycin treatment, 2 have been shown to be expressed by pericytes and smooth muscle cells, in addition to BMEC. TSP1 has been shown to be expressed by retinal pericytes (Canfield et al. 1996), and myosin regulatory light chain 9 (MYL9 or MLC2) is a protein required for cell contractile activity in both smooth muscle and nonmuscle cells including endothelium (Kumar et al. 1989). Thus, assuming contaminating cell expression of TSP1 and MYL9 was higher than that found for BMEC, one explanation for the observed downregulation is simply the removal of these cells from the culture. MYL9 has also been shown to be upregulated in brain endothelium by pulsatile flow (Desai et al. 2002), which in part could also explain the dramatic downregulation of MYL9 upon static in vitro culture compared with the in vivo situation (Table 3). Another gene whose expression was significantly downregulated in puromycin-treated BMEC is serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor (SERPINE1), also known as plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1). The SERPINE1 protein and gene expression levels have been shown to be induced by pericytic factor(s) in both brain and non-brain microvascular endothelial cells (McIlroy et al. 2006), possibly accounting for the downregulation of SERPINE1 observed when pericytes were removed using puromycin. Finally, three gene transcripts, OATP14, ITM2B and NPR2, had expression levels that increased in puromycin-treated cultures, and it appears that the contaminating cells were negative regulators of these BMEC gene products. Taken together, puromycin treatment of BMEC cultures looks to be a useful method to obtain highly pure BMEC cultures without significant change to the BMEC transcriptome.

The glucocorticoid, HC, has been shown to partially restore in vivo properties such as barrier tightness (Hoheisel et al. 1998), with optimal results seen with puromycin-purified BMEC (Calabria et al. 2006). These barrier improvements were accompanied by morphological changes and alterations in junctional structure (Calabria et al. 2006). In addition, previous studies have noted increased tight junction protein expression in immortalized BMEC as the result of glucocorticoid induction (Forster et al. 2005). To more thoroughly investigate the effects of HC induction and its ability to promote cultured BMEC to mimic their in vivo character, puromycin-purified BMEC were treated with HC and gene expression was compared to both untreated BMEC and in vivo BMEC. The treatment resulted in a 3.6-fold increase in TEER as compared to control samples, and Figure 3C demonstrates an overall shift of gene expression towards a more in vivo-like expression profile as 10 of the 12 genes having altered expression levels moved towards the in vivo situation. Three functional categories of genes identified by SSH were regulated in what appeared to be a concerted fashion in HC-treated BMEC. First, HC treatment induced neurogenesis-related gene transcripts; CST3, ITM2B, SEMA3G and SPOCK2. The capability of HC to induce expression of these genes further supports our finding that they are of BMEC origin and suggests an intriguing role for BMEC in regulation of the neurovascular unit. A second set of genes that were differentially regulated and have related functions are involved in angiogenesis. Corticosteriods are known antiangiogenic agents and SERPINE1 levels were increased by HC treatment. Physiological concentrations of SERPINE1 are proangiogenic while higher levels are antiangiogenic (Devy et al. 2002). RECK was also up-regulated after HC treatment, and has been shown to function in an antiangiogenic capacity by inhibiting several membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) (Oh et al. 2001). Also, apelin (APLN), a protein that has vasodilatation/vasoconstriction roles and has been shown to promote gastric cell proliferation in vitro (Wang et al. 2004), was downregulated by HC. Taken together, SERPINE1, RECK, and APLN all responded in a fashion that suggested HC treatment could regulate angiogenesis and/or proliferation of BMEC, possibly via regulation of the extracellular matrix, an effect that could be responsible for the BMEC tightening seen after HC treatment (Calabria et al. 2006; Hoheisel et al. 1998). Interestingly, we have shown that HC treatment does not affect the proliferation rate in these confluent cultures as assessed by BrdU incorporation (Calabria et al. 2006). In contrast, other culture manipulations such as the introduction of pulsatile flow can cause a growth arrest of brain EC, through downregulation of the cyclins (Desai et al. 2002). Thus, HC appears to be functioning in a fashion distinct from that promoted by shear stress, and these data indicate that the quantitative gene panel is comprised of transcriptome elements capable of responding to various stimuli. A third category of genes that was notable for its general lack of response to HC treatment encodes proteins that function as molecular transporters or in vesicular trafficking processes. OATP14, GLUT-1, TfR, PLTP and GOSR1 all remained unchanged by HC treatment, while MDR1A expression was increased. Finally, while HC produced a substantial shift towards the in vivo BMEC transcriptome, none of the differentially-expressed genes examined in this study had expression levels that were completely restored to their in vivo levels by HC treatment. Thus, it would likely take re-introduction of other components of the in vivo microenvironment. As mentioned earlier, other in vitro models having specialized conditions such as co-culture with perivascular brain cells or the presence of flow are in use, and our assessment of in vitro BBB models was by no means exhaustive. However, much like we employed the in vivo versus in vitro quantitative gene panel to assess the effects of puromycin and hydrocortisone on BMEC, this new tool could be used in an analogous fashion to evaluate other in vitro models by allowing direct comparison to the quantitative in vivo transcriptome. This process would also likely increase our understanding of the specific molecular level events that regulate BBB properties.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH grants AA013834 and NS052649, A.R.C. was a recipient of an NIH Biotechnology Training Program Graduate Fellowship at the University of Wisconsin.

References

- Betz AL, Firth JA, Goldstein GW. Polarity of the blood-brain barrier: distribution of enzymes between the luminal and antiluminal membranes of brain capillary endothelial cells. Brain Res. 1980;192:17–28. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boado RJ, Wang L, Pardridge WM. Enhanced expression of the blood-brain barrier GLUT1 glucose transporter gene by brain-derived factors. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;22:259–267. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AM, Jones HC, Abbott NJ. Electrical resistance across the blood-brain barrier in anaesthetized rats: a developmental study. J Physiol. 1990;429:47–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabria AR, Shusta EV. Blood-brain barrier genomics and proteomics: elucidating phenotype, identifying disease targets and enabling brain drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:792–799. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabria AR, Weidenfeller C, Jones AR, de Vries HE, Shusta EV. Puromycin-purified rat brain microvascular endothelial cell cultures exhibit improved barrier properties in response to glucocorticoid induction. J Neurochem. 2006;97:922–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield AE, Sutton AB, Hoyland JA, Schor AM. Association of thrombospondin-1 with osteogenic differentiation of retinal pericytes in vitro. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 2):343–353. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JR, Albers JJ, Lofton-Day CE, Gilbert TL, Ching AF, Grant FJ, O'Hara PJ, Marcovina SM, Adolphson JL. Complete cDNA encoding human phospholipid transfer protein from human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9388–9391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai SY, Marroni M, Cucullo L, Krizanac-Bengez L, Mayberg MR, Hossain MT, Grant GG, Janigro D. Mechanisms of endothelial survival under shear stress. Endothelium. 2002;9:89–102. doi: 10.1080/10623320212004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrumaux C, Deckert V, Athias A, Masson D, Lizard G, Palleau V, Gambert P, Lagrost L. Plasma phospholipid transfer protein prevents vascular endothelium dysfunction by delivering alpha-tocopherol to endothelial cells. Faseb J. 1999;13:883–892. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.8.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devy L, Blacher S, Grignet-Debrus C, Bajou K, Masson V, Gerard RD, Gils A, Carmeliet G, Carmeliet P, Declerck PJ, Noel A, Foidart JM. The pro- or antiangiogenic effect of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 is dose dependent. Faseb J. 2002;16:147–154. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0552com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enerson BE, Drewes LR. The rat blood-brain barrier transcriptome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:959–973. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Clauss M, Wiesnet M, Renz D, Schaper W, Karliczek GF. Hypoxia induces permeability in brain microvessel endothelial cells via VEGF and NO. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C812–820. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.4.C812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster C, Silwedel C, Golenhofen N, Burek M, Kietz S, Mankertz J, Drenckhahn D. Occludin as direct target for glucocorticoid-induced improvement of blood-brain barrier properties in a murine in vitro system. J Physiol. 2005;565:475–486. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard PJ, van der Sandt IC, Voorwinden LH, Vu D, Nielsen JL, de Boer AG, Breimer DD. Astrocytes increase the functional expression of P-glycoprotein in an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier. Pharm Res. 2000;17:1198–1205. doi: 10.1023/a:1026406528530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez D, Reich NC. Stimulation of primary human endothelial cell proliferation by IFN. J Immunol. 2003;170:5373–5381. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabb PA, Gilbert MR. Neoplastic and pharmacological influence on the permeability of an in vitro blood-brain barrier. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:1053–1058. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa A, Naruse M, Hitoshi S, Iwasaki Y, Takebayashi H, Ikenaka K. Regulation of glial development by cystatin C. J Neurochem. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay JC, Chao DS, Kuo CS, Scheller RH. Protein interactions regulating vesicle transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus in mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;89:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx J, Doggen K, Weinberg EO, Van Tongelen P, Fransen P, De Keulenaer GW. Molecular diversity of cardiac endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Physiol Genomics. 2004;19:198–206. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00143.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiyama K, Otani K, Ohtaki M, Satoh K, Kumazaki T, Takahashi T, Mitsui Y, Okazaki Y, Hayashizaki Y, Omatsu H, Noguchi T, Tanimoto K, Nishiyama M. Differentially expressed genes throughout the cellular immortalization processes are quite different between normal human fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoheisel D, Nitz T, Franke H, Wegener J, Hakvoort A, Tilling T, Galla HJ. Hydrocortisone reinforces the blood-brain properties in a serum free cell culture system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:312–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies WA, Brandon MR, Hunt SV, Williams AF, Gatter KC, Mason DY. Transferrin receptor on endothelium of brain capillaries. Nature. 1984;312:162–163. doi: 10.1038/312162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinz MJ, Davenport AP. Immunocytochemical localization of the endogenous vasoactive peptide apelin to human vascular and endocardial endothelial cells. Regul Pept. 2004;118:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar CC, Mohan SR, Zavodny PJ, Narula SK, Leibowitz PJ. Characterization and differential expression of human vascular smooth muscle myosin light chain 2 isoform in nonmuscle cells. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4027–4035. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Blood-brain barrier genomics. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:61–68. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Rat blood-brain barrier genomics. II. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:1319–1326. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000040944.89393.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marroni M, Kight KM, Hossain M, Cucullo L, Desai SY, Janigro D. Dynamic in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier. Gene profiling using cDNA microarray analysis. Methods Mol Med. 2003;89:419–434. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-419-0:419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlroy M, O'Rourke M, McKeown SR, Hirst DG, Robson T. Pericytes influence endothelial cell growth characteristics: role of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada M, Miyamori H, Yamashita J, Sato H. Testican 2 abrogates inhibition of membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases by other testican family proteins. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3364–3369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J, Takahashi R, Kondo S, Mizoguchi A, Adachi E, Sasahara RM, Nishimura S, Imamura Y, Kitayama H, Alexander DB, Ide C, Horan TP, Arakawa T, Yoshida H, Nishikawa S, Itoh Y, Seiki M, Itohara S, Takahashi C, Noda M. The membrane-anchored MMP inhibitor RECK is a key regulator of extracellular matrix integrity and angiogenesis. Cell. 2001;107:789–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda T, Kondoh H. Identification of new genes ndr2 and ndr3 which are related to Ndr1/RTP/Drg1 but show distinct tissue specificity and response to N-myc. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;266:208–215. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. Brain Drug Targeting: The Future of Brain Drug Development. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, U.K.: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Perriere N, Demeuse P, Garcia E, Regina A, Debray M, Andreux JP, Couvreur P, Scherrmann JM, Temsamani J, Couraud PO, Deli MA, Roux F. Puromycin-based purification of rat brain capillary endothelial cell cultures. Effect on the expression of blood-brain barrier-specific properties. J Neurochem. 2005;93:279–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.03020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznik SE, Salafia CM, Lage JM, Fricker LD. Immunohistochemical localization of carboxypeptidases E and D in the human placenta and umbilical cord. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:1359–1368. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LL, Hall DE, Porter S, Barbu K, Cannon C, Horner HC, Janatpour M, Liaw CW, Manning K, Morales J, et al. A cell culture model of the blood-brain barrier. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1725–1735. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnepp A, Komp Lindgren P, Hulsmann H, Kroger S, Paulsson M, Hartmann U. Mouse testican-2. Expression, glycosylation, and effects on neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11274–11280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414276200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani N, Frazier WA. Down-regulation of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 results in thrombospondin-1 expression and concerted regulation of endothelial cell phenotype. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:701–713. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.4.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Goderie SK, Jin L, Karanth N, Sun Y, Abramova N, Vincent P, Pumiglia K, Temple S. Endothelial cells stimulate self-renewal and expand neurogenesis of neural stem cells. Science. 2004;304:1338–1340. doi: 10.1126/science.1095505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shusta EV, Boado RJ, Mathern GW, Pardridge WM. Vascular genomics of the human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:245–252. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga S, Nakao K, Mukoyama M, Arai H, Hosoda K, Ogawa Y, Imura H. Characterization of natriuretic peptide receptors in cultured cells. Hypertension. 1992;19:762–765. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.6.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XT, Zhang MY, Shu C, Li Q, Yan XG, Cheng N, Qiu YD, Ding YT. Differential gene expression during capillary morphogenesis in a microcarrier-based three-dimensional in vitro model of angiogenesis with focus on chemokines and chemokine receptors. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2283–2290. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i15.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M, Masuda T, Fukaya M, Kataoka H, Mishina M, Yaginuma H, Watanabe M, Shimizu T. Identification and characterization of a novel member of murine semaphorin family. Genes Cells. 2005;10:785–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupin P, Ray J, Fischer WH, Suhr ST, Hakansson K, Grubb A, Gage FH. FGF-2-responsive neural stem cell proliferation requires CCg, a novel autocrine/paracrine cofactor. Neuron. 2000;28:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontsch U, Bauer HC. Glial cells and neurons induce blood-brain barrier related enzymes in cultured cerebral endothelial cells. Brain Res. 1991;539:247–253. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91628-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran ND, Schreiber SS, Fisher M. Astrocyte regulation of endothelial tissue plasminogen activator in a blood-brain barrier model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1316–1324. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199812000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal R, Frangione B, Rostagno A, Mead S, Revesz T, Plant G, Ghiso J. A stop-codon mutation in the BRI gene associated with familial British dementia. Nature. 1999;399:776–781. doi: 10.1038/21637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Anini Y, Wei W, Qi X, AM OC, Mochizuki T, Wang HQ, Hellmich MR, Englander EW, Greeley GH., Jr. Apelin, a new enteric peptide: localization in the gastrointestinal tract, ontogeny, and stimulation of gastric cell proliferation and of cholecystokinin secretion. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1342–1348. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasselius J, Hakansson K, Abrahamson M, Ehinger B. Cystatin C in the anterior segment of rat and mouse eyes. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004;82:68–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0420.2003.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]