Abstract

Background

Dependences on addictive substances are substantially-heritable complex disorders whose molecular genetic bases have been partially elucidated by studies that have largely focused on research volunteers, including those recruited in Baltimore. Maryland. Subjects recruited from the Baltimore site of the Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study provide a potentially-useful comparison group for possible confounding features that might arise from selecting research volunteer samples of substance dependent and control individuals. We now report novel SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) genome wide association (GWA) results for vulnerability to substance dependence in ECA participants, who were initially ascertained as members of a probability sample from Baltimore, and compare the results to those from ethnically-matched Baltimore research volunteers.

Results

We identify substantial overlap between the home address zip codes reported by members of these two samples. We find overlapping clusters of SNPs whose allele frequencies differ with nominal significance between substance dependent vs control individuals in both samples. These overlapping clusters of nominally-positive SNPs identify 172 genes in ways that are never found by chance in Monte Carlo simulation studies. Comparison with data from human expressed sequence tags suggests that these genes are expressed in brain, especially in hippocampus and amygdala, to extents that are greater than chance.

Conclusion

The convergent results from these probability sample and research volunteer sample datasets support prior genome wide association results. They fail to support the idea that large portions of the molecular genetic results for vulnerability to substance dependence derive from factors that are limited to research volunteers.

Background

Vulnerability to substance dependence is a complex trait with strong genetic influences that are well documented by data from family, adoption and twin studies [1-4]. Twin studies support the view that much of the heritable influence on vulnerability to dependence on addictive substances from different pharmacological classes (eg nicotine and stimulants) is shared [2,3,5]. Combined data from linkage and genome wide association (GWA) datasets [6-11] suggest that most of the genetics of vulnerability to dependence on addictive substances is likely to be polygenic, arising from variants in genes whose influences on vulnerability, taken one at a time, are relatively modest. Substance-dependent individuals also differ from control individuals in personality, cognitive domains and co-occurrence of psychiatric diagnoses [1,12] (reviewed in [13]).

GWA approaches of increasing sophistication have been developed and used to identify the specific genes and genomic variants that predispose to vulnerability to substance dependence. For example, we have assembled a group of research volunteers from the Molecular Neurobiology Branch of the NIH (NIDA) intramural research program in Baltimore between 1990 and 2008 ("MNB"). We have compared allele frequencies at ca 1500, 10,000, 100,000, 500,000 and then 1,000,000 SNP markers in increasing numbers of substance dependent vs control individuals from this growing sample, including 680 substance dependent or control individuals with self reported European ancestries [6-9,11], (Drgon et al, submitted).

There is the theoretical concern that this MNB sample, and many of the other samples collected for studies of genetics of dependence on addictive substances, might be biased based on the requirement that subjects were ascertained when they volunteered for research. It is conceivable that "volunteering" might interact with heritable features of personality, cognitive, psychiatric and/or other features by which substance dependent individuals might differ from controls [1,12-25]. GWA findings in such research volunteer samples would then conceivably provide a distorted representation of findings that would otherwise be made in members of the community.

The Baltimore site of the Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) Study provides a good comparison group to probe such potential confounding features [24,26]. This study initially assembled a probability sample of individuals who represented the East Baltimore population, including many of the census tracts in which MNB research volunteers reported their home residences. ECA investigators followed substantial portions of these individuals, interviewing them four times and sampling DNA from most of the 1071 individuals from the initial sample who were interviewed in 2004–05 (see below). The repeated assessment of these individuals provides confident assessment of dependence-related phenotypes that include DSM diagnoses of substance abuse and dependence and Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) diagnoses of nicotine dependence.

We thus now report data that confirms the overlapping areas of Baltimore from which ECA and MNB subjects were sampled. We report genome wide association studies for substance dependence phenotypes for Baltimore ECA subjects. We compare these genome wide association results with those from ethnically-matched MNB research volunteers who were recruited from many of the same areas. We discuss the significance of the substantially-overlapping data that we report, as well as the limitations of the samples and datasets. These data document large molecular genetic overlaps between probability-sample and research volunteer samples for substance dependence.

Methods

ECA Sample

Subjects from the Baltimore (Eastern Baltimore Mental Health Survey) site for the Epidemiological Catchment Area Program (ECA) were ascertained as a probability sample of individuals in dwelling units within census tracts near the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions and initially interviewed in 1981 [24,26]. Subsets of these individuals were interviewed in 1982, 1993–96 and 2004–5. Diagnoses came from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS), a self-report instrument [27] whose validity and reliability has been documented in this sample [27a]. Smoking was also described using the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) [28-30]. Although many of the individuals who were > 65 in 1981 had died by the 2004–05 follow-up, self-report survey data was collected from 662 European-American respondents (63% female) during this follow-up. This subset provided good representation of the composition of the portion of the original Baltimore ECA cohort that was of this race/ethnicity. Blood for DNA extraction and for lymphocyte immortalization was obtained from 74% of these individuals, who did not differ from subjects from whom DNA was not obtained in any obvious feature that related to substance dependence [30a].

Individuals who were dependent on an abused substance were identified by DSM criteria, except for nicotine dependence which was based on FTND criteria. Eighty substance dependent individuals were identified. These individuals were matched for gender and age to eighty control individuals. These control individuals were East Baltimore ECA participants who never used any illegal drugs more then 5 times in their lives, were not dependent on any drug or alcohol, drank less than one drink per day (waves 3 and 4) drank less than 5 drinks/week (waves 1 and 2) and had FTND scores < 7. Generation and analyses of these data were approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health IRB and exempt protocols for pooled genotyping approved by the NIH Office of Human Research Subject Protection.

Comparison research volunteer sample

Data from these European-American ECA subjects was compared to data from European-American MNB research volunteers who provided informed consents, ethnicity data, drug use histories and DSMIII-R or IV diagnoses as previously described [6,31,32]. DNA in 34 pools sampled 400 "abusers" with heavy lifetime use of illegal substances and, for virtually all, DSMIII-R/IV dependence on at least one illegal abused substance and 280 "controls" who reported no significant lifetime use of any addictive substance. Generation and analyses of these data were approved by the NIH IRP (NIDA) IRB (protocol #148) and exempt protocols for pooled genotyping approved by the NIH Office of Human Research Subject Protection.

DNA preparation and assessment of allelic frequencies

DNA was prepared from blood (MNB and some ECA subjects) or cell lines (most ECA subjects) [6,31,32] and carefully quantitated. DNAs from groups of 20 individuals of the same phenotype were combined. Hybridization probes were prepared with precautions to avoid contamination, as described (Affymetrix assays 500 k [9,11,33,34]). 150 ng of pooled DNA was digested using StyI or NspI, ligated to appropriate adaptors and amplified using a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with 3 min 94°C, 30 cycles of 30 sec 94°C, 45 sec 60°C, 15 sec at 68°C and a final 7 min 68°C extension. PCR products were purified (MinEluteTM 96 UF kits, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and quantitated. Forty μg of PCR product was digested for 35 min at 37°C with 0.04 unit/μl DNase I to produce 30–100 bp fragments which were end-labeled using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and biotinylated dideoxynucleotides and hybridized to the appropriate 500 k array (Sty I or Nsp I arrays) (Mendel array sets, Affymetrix). Arrays were stained and washed as described (Affymetrix Genechip Mapping Assay Manual) using immunopure strepavidin (Pierce, Milwaukee, WI), biotinylated antistreptavidin antibody (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) and R-phycoerythrin strepavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Arrays were scanned and fluorescence intensities quantitated using an Affymetrix array scanner as described [9,11,33,34].

Chromosomal positions for each SNP were sought using NCBI (Build 36.1) and NETAFFYX (Affymetrix) data. Allele frequencies for each SNP in each DNA pool were assessed based on hybridization intensity signals from four arrays, allowing assessment of hybridization to the 12 "perfect match" cells on each array that are complementary to the PCR products from alleles "A" and "B" for each diallelic SNP on sense and antisense strands. We eliminated: i) SNPs on sex chromosomes and iii) SNPs whose chromosomal positions could not be adequately determined.

Each array was analyzed as described [9,11,33,34], with background values subtracted, normalization to the highest values noted on the array, averaging of the hybridization intensities from the array cells that corresponded to the perfect match "A" and "B" cells, calculation of "A/B ratios" by dividing average normalized A values by average normalized B values, arctangent transformations to aid combination of data from arrays hybridized and scanned on different days, and determination of the average arctangent value for each SNP from the 4 replicate arrays. A "t" statistic for the differences between abusers and controls was generated as described [9,11,33,34] for each SNP. We focused on SNPs that displayed t statistics with p < 0.05 for abuser/control differences. We sought evidence for clustering of these SNPs by focusing on chromosomal regions in which at least three of these outlier SNPs, assessed by at least two array types, lay within 25 Kb of each other. We term these clustered, nominally-positive SNPs "clustered positive SNPs", and focus our analyses on regions in which they lie.

To confirm the SNPs within the positive clusters from the current dataset, we sought convergence between data from these clustered nominally-positive SNPs and clustered nominally-positive SNPs, determined in the same way, from 1 M SNP genome wide association studies of the MNB samples (Drgon et al, submitted). To provide insights into some of the genes likely to harbor variants that contribute to individual differences in vulnerability to substance dependence, we sought candidate genes that were identified by overlapping clusters of positive SNPs from each of these samples.

We compare observed results to those expected by chance using Monte Carlo simulation trials, as described [9,11,33,34]. For each trial, a randomly-selected set of SNPs from the current dataset was assessed to see if it provided results equal to or greater than the results that we actually observed. The number of trials for which the randomly-selected SNPs displayed (at least) the same features displayed by the observed results was then tallied to generate an empirical p value. These simulations thus correct for the number of repeated comparisons made in these analyses, an important consideration in evaluating these GWA datasets. We thus focus on genes which display convergence between nominally-significant results obtained from the two dependence vs control samples. We report Monte Carlo probabilities for the observed convergence of clustered nominally positive SNPs within each gene, using simulations that correct for the number of repeated comparisons.

To assess the power of our current approach, we use current sample sizes and standard deviations, the program PS v2.1.31 [35,36] and α = 0.05. To provide controls for the possibilities that abuser-control differences observed herein were due to a) occult ethnic/racial allele frequency differences or b) noisy assays, we assessed the overlap between the results obtained here and the SNPs that displayed the largest a) allele frequency differences between African-American vs European-American control individuals and b) the largest assay "noise".

We have compared the patterns of human brain expression for the genes identified herein to those identified using a novel tool based on the distribution of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) contained in an annotated set of brain cDNA libraries (CYL, GRU et al, in preparation). Briefly, we identified 846 human cDNA libraries with cDNAs represented in dbEST. These libraries were constructed from regions of brains that appeared to display modest or no pathology. We based the analyses on two sets of criteria: 1) all entries in these libraries and 2) "more reliable" entries that display i) correct genomic orientation and either ii a) evidence for polyA tail or ii b) spliced structure (CYL, GRU et al, in preparation). For each brain region, we assessed the p-value for over-representation of expression of the dependence-associated genes using hypergeometric distribution tests with false discovery rate (FDR) corrections. Q-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

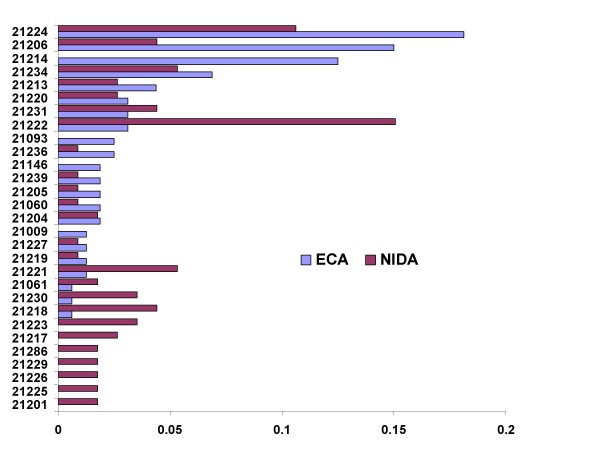

We assessed the extent to which the ECA and NIDA research volunteers came from similar Baltimore neighborhoods by comparing the distributions of available zip codes from these samples. As noted in Figure 1, there was substantial overlap between these zip code distributions, providing impetus for the comparative molecular genetic studies described below.

Figure 1.

Substantial overlaps of the zip codes in which subjects reported their residences. Fractional distributions (X axis) of zip codes (Y axis) in which ECA (solid blue bars) or MNB (dotted purple bars) subjects reported their residence. Areas from which NIDA and ECA recruitment efforts were dissimilar include 21214; Lauraville and surrounding areas and 21222, Dundalk and surrounding areas. Zip codes from which fewer than 3 individuals were recruited are not indicated.

We then assessed allele frequencies in multiple pools of DNA from substance dependent and control ECA individuals. There was modest variability among replicate arrays that assessed the same pool (standard error of the mean (SEM) 0.032) and among the different pools that assessed the same phenotype (SEM 0.033). These samples and these estimates of variance thus provided 0.9, 0.74, 0.46 and 0.21 power to detect allele frequency differences of 12.5, 10, 7.5 and 5%, respectively.

28,137 SNPs displayed "nominally positive" t values with p < 0.05 in these ECA samples. 7,620 of these nominally positive SNPs fell into 1660 clusters of at least 3 SNPs that came from both array types were separated from adjacent nominally-positive SNPs by less than 25,000 basepairs. Monte Carlo simulations reveal p < 0.00001 for this degree of clustering.

One hundred seventy two genes are identified by both 1) clusters of nominally-positive SNPs from the ECA samples and 2) overlapping clusters of nominally positive SNPs from MNB samples. We list the 126 of these genes whose nominal Monte Carlo p values are < 0.05 in Table 1. This number of genes is never identified by chance in both samples by any of 10,000 Monte Carlo simulation trials (thus, p < 0.0001). There is also overlap, to extents greater than expected by chance, with the clusters of SNPs whose allele frequencies distinguish MNB African-American polysubstance abusers from controls (p < 0.0001) [9], Japanese methamphetamine abusers from controls (p < 0.0001) [11], Taiwanese methamphetamine abusers from controls (p < 0.0007) [11] and more-frequently nicotine dependent smokers of European ancestry from less-frequently nicotine dependent smokers (p < 0.0001) [10].

Table 1.

Genes that contain overlapping clusters of nominally positive SNPs in both ECA and European-American MNB research volunteer samples that display nominal p < 0.05.

| Clust SNPs | ||||||

| gene | ch | bp | description | ECA | MNB | p |

| A2BP1 | 16 | 6,009,133 | ataxin 2-binding protein 1 | 16 | 42 | 0.0038 |

| ACCN1 | 17 | 28,364,218 | neuronal amiloride-sens cation chan 1 | 5 | 5 | 0.0240 |

| ADARB2 | 10 | 1,218,073 | RNA spec A deaminase B2 | 4 | 8 | 0.0420 |

| ADCY2 | 5 | 7,449,345 | adenylate cyclase 2 | 7 | 6 | 0.0210 |

| AGBL4 | 1 | 48,822,129 | ATP/GTP binding protein-like 4 | 3 | 8 | 0.0400 |

| AK5 | 1 | 77,520,330 | adenylate kinase 5 | 10 | 4 | 0.0090 |

| AKAP6 | 14 | 31,868,274 | A kinase anchoring protein 6 | 3 | 15 | 0.0210 |

| ALK | 2 | 29,269,144 | anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) | 6 | 10 | 0.0470 |

| ANKFN1 | 17 | 51,585,835 | ankyrin-rep Fn III dom cont 1 | 3 | 14 | 0.0130 |

| ATXN1 | 6 | 16,407,322 | ataxin 1 | 3 | 17 | 0.0120 |

| C18orf1 | 18 | 13,208,795 | chromosome 18 open reading frame 1 | 4 | 6 | 0.0440 |

| C3orf21 | 3 | 196,270,302 | chromosome 3 open reading frame 21 | 4 | 4 | 0.0380 |

| C8A | 1 | 57,093,065 | complement component 8 α polypep | 3 | 7 | 0.0180 |

| C9orf88 | 9 | 129,307,439 | Chr 9 open reading frame 88 | 4 | 4 | 0.0220 |

| CABIN1 | 22 | 22,737,765 | calcineurin binding protein 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.0220 |

| CACNA2D3 | 3 | 54,131,733 | voltage det Ca chan α2/δ3 subunit | 12 | 18 | 0.0091 |

| CCBE1 | 18 | 55,252,124 | collagen and calcium binding EGF domains 1 | 7 | 10 | 0.0090 |

| CCDC63 | 12 | 109,769,194 | coiled-coil domain containing 63 | 3 | 4 | 0.0290 |

| CD180 | 5 | 66,513,872 | CD180 molecule | 5 | 5 | 0.0051 |

| CDH13 | 16 | 81,218,079 | cadherin 13 | 18 | 65 | 0.0019 |

| CDH23 | 10 | 72,826,697 | cadherin-like 23 | 7 | 4 | 0.0380 |

| CGNL1 | 15 | 55,455,997 | cingulin-like 1 | 3 | 11 | 0.0040 |

| CHL1 | 3 | 213,650 | close homolog of L1 | 3 | 12 | 0.0103 |

| CHST11 | 12 | 103,370,614 | chondroitin 4 sulfotransferase 11 | 4 | 4 | 0.0470 |

| CIT | 12 | 118,607,981 | citron rho-interacting, serine/threonine kinase 21 | 5 | 6 | 0.0160 |

| CNTN5 | 11 | 98,397,081 | contactin 5 | 11 | 10 | 0.0390 |

| CNTNAP2 | 7 | 145,444,386 | contactin associated protein-like 2 | 22 | 9 | 0.0380 |

| CPVL | 7 | 29,001,772 | carboxypeptidase vitellogenic-like | 4 | 4 | 0.0290 |

| CRYL1 | 13 | 19,875,810 | crystalline λ1 | 4 | 5 | 0.0170 |

| CSMD1 | 8 | 2,782,789 | CUB and Sushi multiple domains 1 | 29 | 137 | 0.0014 |

| CUGBP2 | 10 | 11,087,290 | CUG triplet repeat RNA bind prot 2 | 16 | 4 | 0.0031 |

| DAB1 | 1 | 57,236,167 | disabled homolog 1 | 4 | 24 | 0.0140 |

| DLC1 | 8 | 12,985,243 | deleted in liver cancer 1 | 13 | 9 | 0.0059 |

| DNAPTP6 | 2 | 200,879,041 | DNA polymerase-transactivated protein 6 | 8 | 4 | 0.0140 |

| DOCK2 | 5 | 168,996,871 | dedicator of cytokinesis 2 | 3 | 7 | 0.0490 |

| DPP6 | 7 | 154,060,464 | dipeptidyl-peptidase 6 | 6 | 4 | 0.0250 |

| EDNRA | 4 | 148,621,575 | endothelin receptor type A | 3 | 4 | 0.0280 |

| EFCAB4B | 12 | 3,627,370 | EF-hand calcium binding domain 4B | 3 | 6 | 0.0165 |

| EPHB1 | 3 | 135,996,950 | EPH receptor B1 | 13 | 5 | 0.0090 |

| ESRRG | 1 | 214,743,211 | estrogen-related receptor γ | 3 | 14 | 0.0210 |

| EVI1 | 3 | 170,285,244 | ecotropic viral integration site 1 | 3 | 12 | 0.0047 |

| F5 | 1 | 167,750,033 | coagulation factor V | 4 | 11 | 0.0049 |

| FAM13A1 | 4 | 89,866,129 | family with seq sim 13 A1 | 6 | 4 | 0.0360 |

| FAM3C | 7 | 120,776,141 | family with sequence similarity 3 C | 6 | 4 | 0.0109 |

| FAM3D | 3 | 58,594,710 | family with sequence similarity 3 D | 7 | 4 | 0.0063 |

| FBXL17 | 5 | 107,223,348 | F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 17 | 6 | 6 | 0.0430 |

| FGD2 | 6 | 37,081,401 | FYVE, RhoGEF PH dom cont 2 | 3 | 4 | 0.0320 |

| FHIT | 3 | 59,710,076 | fragile histidine triad gene | 24 | 62 | 0.0030 |

| FLJ11151 | 16 | 12,664,438 | hypothetical protein FLJ11151 | 4 | 4 | 0.0380 |

| FLJ32682 | 13 | 45,013,433 | hypothetical protein FLJ32682 | 4 | 5 | 0.0180 |

| FN1 | 2 | 215,933,422 | fibronectin 1 | 3 | 5 | 0.0260 |

| FOXP1 | 3 | 71,087,426 | forkhead box P1 | 4 | 17 | 0.0180 |

| FREM3 | 4 | 144,717,905 | FRAS1 related extracellular matrix 3 | 4 | 6 | 0.0130 |

| FRMD4A | 10 | 13,725,718 | FERM domain containing 4A | 3 | 23 | 0.0090 |

| GABBR2 | 9 | 100,090,187 | GABA B receptor 2 | 11 | 6 | 0.0073 |

| GLIS3 | 9 | 3,817,676 | GLIS family zinc finger 3 | 13 | 18 | 0.0016 |

| GRB10 | 7 | 50,625,259 | growth factor receptor-bound protein 10 | 3 | 13 | 0.0083 |

| GRID1 | 10 | 87,349,292 | delta 1 inotropic glutamate rec | 7 | 18 | 0.0130 |

| GRIK1 | 21 | 29,831,125 | kainate 1 inotropic glutamate rec | 4 | 12 | 0.0150 |

| GTF2F2L | 4 | 148,646,691 | general transcription fact IIFpolypep 2-L | 3 | 3 | 0.0170 |

| HPSE2 | 10 | 100,208,867 | heparanase 2 | 6 | 18 | 0.0160 |

| HS3ST4 | 16 | 25,611,240 | heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfotransferase 4 | 4 | 11 | 0.0250 |

| IMPA2 | 18 | 11,971,455 | inositol(myo)-1(or 4)-monophosphatase 2 | 6 | 6 | 0.0064 |

| IQGAP2 | 5 | 75,734,905 | IQ motif cont GTPase activ prot 2 | 7 | 5 | 0.0170 |

| JAKMIP1 | 4 | 6,106,385 | janus kinase microtubule interacting protein 1 | 3 | 8 | 0.0138 |

| KCNB1 | 20 | 47,421,912 | Shab-rel volt-gated K chan 1 | 5 | 3 | 0.0190 |

| KCNIP4 | 4 | 20,339,337 | Kv channel interacting protein 4 | 13 | 9 | 0.0107 |

| KCNJ6 | 21 | 37,918,655 | inwardly-rect K chan J 6 | 3 | 8 | 0.0330 |

| KCNMA1 | 10 | 78,299,366 | large conduct Ca-act K chan M α1 | 8 | 8 | 0.0390 |

| KIAA1576 | 16 | 76,379,984 | KIAA1576 protein | 3 | 6 | 0.0260 |

| KREMEN1 | 22 | 27,799,106 | kringle cont TM prot 1 | 5 | 4 | 0.0190 |

| KSR2 | 12 | 116,389,387 | kinase suppressor of ras 2 | 5 | 4 | 0.0430 |

| LDLRAD3 | 11 | 35,922,188 | low density lipoprotein recep cl A dom cont 3 | 3 | 6 | 0.0330 |

| LTF | 3 | 46,452,500 | lactotransferrin | 3 | 4 | 0.0290 |

| MAGI1 | 3 | 65,314,946 | membr-assoc G kinase WW PDZ dom cont 1 | 6 | 9 | 0.0380 |

| MAGI2 | 7 | 77,484,310 | membrane assoc G kinase WW PDZ dom 2 | 9 | 16 | 0.0430 |

| MGC23985 | 5 | 147,252,464 | similar to AVLV472 | 3 | 7 | 0.0085 |

| MICAL2 | 11 | 12,088,714 | calponin LIM cont microtub monoxygenase 2 | 8 | 8 | 0.0120 |

| MTSS1 | 8 | 125,632,212 | metastasis suppressor 1 | 9 | 9 | 0.0050 |

| MTUS1 | 8 | 17,545,583 | mitochondrial tumor suppressor 1 | 3 | 4 | 0.0090 |

| MYO18B | 22 | 24,468,120 | myosin XVIIIB | 15 | 8 | 0.0460 |

| MYO3A | 10 | 26,263,202 | myosin IIIA | 3 | 5 | 0.0018 |

| NAALADL2 | 3 | 176,059,805 | N-Ac α-linked acidic dipeptidase-L 2 | 4 | 5 | 0.0340 |

| NFIA | 1 | 61,320,881 | nuclear factor I/A | 4 | 4 | 0.0080 |

| NLGN1 | 3 | 174,598,938 | neuroligin 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.0260 |

| OPCML | 11 | 131,790,085 | opioid binding protein/cell adhesion molecule-L | 10 | 13 | 0.0076 |

| PALM2 | 9 | 111,442,893 | paralemmin 2 | 10 | 16 | 0.0220 |

| PALM2-AKAP2 | 9 | 111,582,410 | PALM2-AKAP2 protein | 5 | 10 | 0.0021 |

| PARD3B | 2 | 205,118,761 | par-3 partitioning defective 3 homolog B | 3 | 5 | 0.0160 |

| PDE4D | 5 | 58,302,468 | cAMP spec phosphodiesterase 4D | 4 | 4 | 0.0140 |

| PKD1L2 | 16 | 79,691,991 | polycystic kidney disease 1-like 2 | 4 | 4 | 0.0060 |

| PLD5 | 1 | 240,318,895 | phospholipase D family 5 | 3 | 16 | 0.0300 |

| PRKCA | 17 | 61,729,388 | protein kinase C α | 6 | 4 | 0.0113 |

| PRKCH | 14 | 60,858,268 | protein kinase C η | 7 | 22 | 0.0300 |

| PRKG1 | 10 | 52,504,299 | cGMP dep protein kinase I | 12 | 10 | 0.0014 |

| PRPF4 | 9 | 115,077,795 | PRP4 pre-mRNA process fact 4 homol | 6 | 4 | 0.0360 |

| PSD3 | 8 | 18,432,343 | pleckstrin and Sec7 domain containing 3 | 8 | 16 | 0.0240 |

| PTPN14 | 1 | 212,597,634 | no rec prot Y phosphatase 14 | 10 | 4 | 0.0150 |

| PTPRK | 6 | 128,331,625 | recept protein tyrosine phosphatase K | 3 | 8 | 0.0062 |

| PTPRT | 20 | 40,134,806 | recept prot Y phosphatase T | 3 | 15 | 0.0190 |

| RBMS3 | 3 | 29,297,947 | sing strand RNA binding motif interact prot | 5 | 13 | 0.0230 |

| ROR2 | 9 | 93,524,705 | receptor tyrosine kinase-L orphan recept 2 | 5 | 4 | 0.0290 |

| RORA | 15 | 58,576,755 | RAR-related orphan receptor A | 4 | 9 | 0.0220 |

| SLC2A13 | 12 | 38,435,090 | solute carrier family 2 13 | 4 | 4 | 0.0086 |

| SLIT3 | 5 | 168,025,857 | slit homolog 3 | 3 | 4 | 0.0370 |

| SRGAP3 | 3 | 8,997,278 | SLIT-ROBO Rho GTPase activating protein 3 | 4 | 23 | 0.0087 |

| STK32B | 4 | 5,104,428 | serine threonine kinase 32B | 3 | 25 | 0.0011 |

| STK39 | 2 | 168,518,777 | serine threonine kinase 39 | 4 | 4 | 0.0036 |

| SYNE1 | 6 | 152,484,516 | spectrin rep cont nuclear envelope 1 | 7 | 5 | 0.0034 |

| TACC2 | 10 | 123,738,679 | transforming acidic coil-coil cont prot 2 | 3 | 9 | 0.0430 |

| TBC1D22A | 22 | 45,537,213 | TBC1 domain family 22A | 3 | 8 | 0.0270 |

| TEK | 9 | 27,099,286 | TEK tyrosine kinase, endothelial | 3 | 9 | 0.0420 |

| TG | 8 | 133,948,387 | thyroglobulin | 4 | 4 | 0.0180 |

| THSD4 | 15 | 69,220,842 | thrombospondin I dom cont 4 | 3 | 11 | 0.0063 |

| TMEM132C | 12 | 127,318,855 | transmembrane protein 132C | 5 | 13 | 0.0084 |

| TMEM132D | 12 | 128,122,224 | transmembrane protein 132D | 8 | 11 | 0.0090 |

| TMEM16D | 12 | 99,712,716 | transmembrane protein 16D | 11 | 11 | 0.0320 |

| TMTC1 | 12 | 29,545,024 | transmemb tetratricopep rep cont 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.0035 |

| TRPC4 | 13 | 37,108,795 | transient receptor potential cation channel C 4 | 8 | 4 | 0.0140 |

| TULP4 | 6 | 158,653,680 | tubby like protein 4 | 6 | 9 | 0.0076 |

| UNC5C | 4 | 96,308,712 | unc-5 homolog C | 9 | 4 | 0.0162 |

| VAMP4 | 1 | 169,938,783 | vesicle-associated membrane protein 4 | 3 | 5 | 0.0170 |

| VAPB | 20 | 56,397,651 | vesicle-assoc memb protein-assoc prot B C | 4 | 11 | 0.0034 |

| VIT | 2 | 36,777,418 | Vitrin | 3 | 9 | 0.0110 |

| ZNF365 | 10 | 63,803,957 | zinc finger protein 365 | 6 | 4 | 0.0340 |

| ZNF406 | 8 | 135,559,213 | zinc finger protein 406 | 16 | 4 | 0.0014 |

The numbers of nominally-positive SNPs that lay in clusters within the gene's exons and in 10 kb genomic flanking regions are noted for each sample. Chromosome number and initial chromosomal position for the cluster (bp, NCBI Mapviewer Build 36.1) are listed. Nominal p values for each gene are based on 10,000 Monte Carlo simulation trials. For each trial, the number of times randomly-selected segments of the genome that lie within genes are assessed for the same features displayed by the actual gene identified. Note that the very highly significant p values for the overall convergence noted between these two datasets (text) does account for multiple comparisons, while the much more modest p values for many of the individual genes (displayed here) do not. Genes that are identified by clustered nominally positive SNPs in both samples but whose gene-wise p values lie > 0.05 (perhaps, in part, due to the large size of the genes) include: C4orf13, PRKCE, UNC13C, KIAA1303, MYR8, DNAH11, ONECUT2, TGFBR3, TPD52L1, C9orf28, TMEM108, GALNT14, HECW2, NFIB, STS-1, KIAA1217, RAB3C, SNTG1, CPNE4, PTPRM, SLC39A11, MDS1, GPC5, ZNF533, NR5A2, RYR3, C8orf68, CTNNA2, GRM5, ATRNL1, ARL15, BTBD9, CNTNAP5, GALNTL4, PELI2, SNRPN, GPR98, ERC2, NFATC2, FLJ16124, GRM7, SORCS2, NPAS3, PARVB, IGL@ and LRP1B.

We would anticipate the observed, highly-significant clustering of SNPs that display nominally-positive results if many of these reproducibly-positive SNPs lay near and were in linkage disequilibrium with functional allelic variants that distinguished substance-dependent subjects from control subjects. We would not anticipate this degree of clustering if the results were solely due to chance. The Monte Carlo p values noted here are thus likely to receive contributions from both the extent of linkage disequilibrium among the clustered, nominally-positive SNPs and the extent of linkage disequilibrium between these SNPs and the functional haplotype(s) that lead to the association with substance dependence.

Neither controls for occult stratification nor for assay variability appear to provide convincing alternative explanations for most of the data obtained here. When we examined the overlap between the 7620 clustered positive SNPs from the ECA samples and: 1) the 2.5% of the SNPs for which the noise in validating studies was highest and 2) the 2.5% of SNPs that displayed the largest differences between Baltimore African-American vs European American control individuals, we found 15 and 245, respectively, vs 185 expected by chance in each case.

We evaluated evidence for preferential brain and brain regional expression of the 172 genes identified in Table 1 (body and legend). Brain libraries represented in dbEST contained ESTs that corresponded to 91% (157/172) of these genes. Expression for this set of genes (compared to all genes) displayed nominal significance in thalamus (p < 10-8), amygdale (p = 5.6 × 10-9), hippocampus (p = 2.6 × 10-5), frontal cortex (p = 0.015) and medulla (p = 0.039) using hypergeometric tests (p values were Bonferroni corrected for repeated comparisons). Assessments of the "more reliable" subset of ESTs revealed significant overexpression in whole brain (p = 2.1 × 10-7), amygdala (p = 4.4 × 10-6), hippocampus (p = 0.0011), cerebellum (p = 0.0052), thalamus (p = 0.037) and cortex (p = 0.049) (p-values were Bonferroni corrected).

Discussion

The current results 1) provide independent support for GWA results from larger samples of research volunteers studied for substance dependence phenotypes and 2) provide a control for one of the potential confounding features of this previously-studied sample. The possibility that genetic results from members of any sample of research volunteers might not represent the genetics of members of the general population is ever present. In molecular genetic studies of substance dependence, however, features that are both 1) heritable and 2) differentially present in substance dependent individuals might, a priori, be considered to be especially likely to provide confounding influences. Cognitive abilities are highly heritable. Cognitive tests in a number of samples of substance dependent individuals have indicated differences in performance (reviewed in [13]). A study in twin pairs whose members were discordant for substance use concluded that most of these cognitive differences were likely to be heritable antecedents to, not just consequences of, the use of addictive substances [37]. Cognitive abilities have been shown to interact with willingness to volunteer for and/or participate in research protocols in a number of settings [1,12,14-25]. A number of personality features are also highly heritable [38]. Neuroticism is both one of the more heritable personality features and also the personality feature that has been demonstrated to be elevated in several samples of substance dependent individuals [38]. Personality features have also been linked to willingness to volunteer for participation in research protocols [1,12,14-25]. A number of psychiatric disorders that might also be linked to differential willingness (or ability) to participate as a research volunteer are also heritable and co-occur with substance dependences at rates much greater than chance [13].

It is also important to keep a number of limitations in mind in considering the present results. 1) The preplanned approach used here demands that multiple nominally-positive SNPs from each sample tag the same genomic region that lies within a gene. Requirements that nominally positive SNPs from the current dataset come from each of the two 500 k array types add a technical control. Monte Carlo approaches that do not require specification of underlying distributions can readily judge the degree to which all of the observations made here could be due to chance. Nevertheless, there have been no unanimous criteria for declaring "replication" or "convergence" for GWA studies, a consideration worth considering in evaluating the current results. 2) The ECA samples are of modest size, limited by the numbers of substance abusing or dependent individuals in the aging Baltimore ECA cohort follow-up samples. Power calculations that document the modest power in European-Americans samples revealed even more modest power for the smaller number of African-American substance dependent individuals in this sample; we have thus not analyzed these samples. Modest power limits interpretation of negative data, substantially restricting inferences about genes identified in the more robust dataset from MNB research volunteers but not in these ECA samples. 3) There is very highly significant confidence in the overall set of convergent positive results reported here. However, the values for each gene, tested individually, provide much more modest levels of statistical assurance. 4) Focus on data from autosomes here allows us to combine data from male and female subjects, but misses potentially important contributions from sex chromosomes. 5) The individuals in the Baltimore ECA cohort were not initially sampled based on their willingness to be volunteers. However, participants needed to consent in order to be able to be followed and studied genetically. Although the overwhelming majority of the European-American participants who were followed did consent to participation in genetic studies, potential contributions that the non-consenting individuals might have made to the present results remain unknown. 6) The pooling approach that we use here provides excellent correlations between individually-genotyped and pooled allele frequency assessments in validation experiments. This approach has allowed us to use these samples without adding additional confidentiality burdens to these intensively-studied individuals. Nevertheless, estimates of allele frequencies based on pooled data represent approximations of "true" allele frequency differences that might be determined by error free individual genotyping of each participant. 7) There is no indication that the overall positive results reported here are based on the SNPs whose assays provide more noise, and no indication that occult stratification on racial/ethnic lines contributed overall to the results that we obtain here. However, we cannot totally exclude contributions of occult stratification that cannot be detected by these overall screens to findings in specific genes. 8) The convergent data derived from studies of individuals with dependence on substances in several different pharmacological classes supports the idea that many allelic variants enhance vulnerability to dependence on a number of substances. These results do not exclude additional contributions from genomic variants that influence vulnerability to specific substances. 9) We focus on identification of genes. Although associations away from annotated genes can also provide interesting results, the genes that we identify in the present work provide a number of interesting views of substance dependence. These data reinforce our observations that many of these genes are likely to contribute to brain differences that are reflected in the mnemonic aspects of addiction, and that some of them also provide tempting targets for antiaddiction therapeutics. We discuss these ideas in more detail elsewhere [12,13].

More of the genes identified here are represented among cDNAs cloned from brain libraries than is the case for all human genes. The results focus attention on expression in hippocampus, which manifests interesting roles in mnemonic processes and cerebral cortical connections that may provide additional clues to the pathophysiology of human substance dependence. Although detailed discussion of each of these groups of genes is beyond the scope of this report, it is interesting to note that about 15% of the genes enumerated in Table 1 can be related to cell adhesion mechanisms. This is a much larger fraction that the fraction of all genes, about 2%, that are identified as cell adhesion molecules in a recent bioinformatic approach to comprehensively identifying cell adhesion molecules [39], supporting overrepresentation of these genes among addiction-associated genes.

A number of the genes identified in this work are also identified in genome wide association and/or candidate gene datasets for heritable disorders or phenotypes that co-occur with addictions. As we discuss elsewhere, dependence-vulnerability GWA results overlap at levels greater than expected by chance with GWA studies of cognitive abilities, personality features, frontal lobe brain volumes and bipolar disorder [13].

Conclusion

The observations in the present dataset that the findings from a population-based sample converge strongly with those made in larger research volunteer samples are reassuring. They support the idea that many of the molecular genetic findings that we and others have previously reported are not due simply to the methods used for ascertainment of "cases" and "controls" for our studies in research volunteers. It is important to note that this overall conclusion does not exclude contributions for some of these sampling issues to findings in particular genes. Nevertheless, the findings presented here promise to add to ongoing processes for comparing GWA datasets from research volunteers to those from population based samples. For dependence on alcohol, tobacco and other drugs, as for many complex disorders, such data provides an increasingly rich basis for improved understanding and for personalization of prevention and treatment strategies.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

DSM: diagnostic and statistical manual; ECA: Epidemiological catchment area; MNB: Molecular Neurobiology Research Branch.

Authors' contributions

CJ performed data manipulation, analysis and participated in the interpretation of the results. TD participated in DNA pool preparation, data acquisition, data analysis and manuscript preparation. QRL and PWZ participated in probe synthesis and data acquisition. DW performed the DNA and DNA pool preparation and participated in data acquisition. CYL participated in data analysis. JA participated in conception of the study and worked with the ECA study. YD helped to identify participants with specific clinical characteristics. WE participated in the conception of the study, study design and funding, and interpretation of the results. GRU conceived the study, participated in study design, data analysis and drafted and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for thoughtful advice and discussion from Drs N Ialongo, C Storer and P Zandi. This research was supported financially by the NIH Intramural Research Program, NIDA, DHSS and National Institute of Mental Health grants R01-47447 and T32-14592, and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health IRB H.33.01.03.26.A2 (WE). We are also grateful to the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program's principal collaborators (D Regier, B Locke, WE and J Burke) and to Drs M Kramer, E Gruenberg, and S Shapiro from the Johns Hopkins site, supported by UO1 MH 33870.

Contributor Information

Catherine Johnson, Email: johnsoncat@intra.nida.nih.gov.

Tomas Drgon, Email: tdrgon@intra.nida.nih.gov.

Qing-Rong Liu, Email: qrliu@intra.nida.nih.gov.

Ping-Wu Zhang, Email: pwzhang@intra.nida.nih.gov.

Donna Walther, Email: dwalther@intra.nida.nih.gov.

Chuan-Yun Li, Email: lichua@nida.nih.gov.

James C Anthony, Email: janthony@msu.edu.

Yulan Ding, Email: yding@jhsph.edu.

William W Eaton, Email: weaton@jhsph.edu.

George R Uhl, Email: guhl@intra.nida.nih.gov.

References

- Uhl GR, Elmer GI, Labuda MC, Pickens RW. Genetic influences in drug abuse. In: Gloom FE, Kupfer DJ, editor. Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. New York: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 1793–2783. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Meyer JM, Doyle T, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, True W, Lin N, Toomey R, Eaves L. Co-occurrence of abuse of different drugs in men: the role of drug-specific and shared vulnerabilities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:967–972. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkowski LM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Multivariate assessment of factors influencing illicit substance use in twins from female-female pairs. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96:665–670. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20001009)96:5<665::AID-AJMG13>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True WR, Heath AC, Scherrer JF, Xian H, Lin N, Eisen SA, Lyons MJ, Goldberg J, Tsuang MT. Interrelationship of genetic and environmental influences on conduct disorder and alcohol and marijuana dependence symptoms. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:391–397. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19990820)88:4<391::AID-AJMG17>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Neale MC, Prescott CA. Illicit psychoactive substance use, heavy use, abuse, and dependence in a US population-based sample of male twins. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:261–269. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Liu QR, Walther D, Hess J, Naiman D. Polysubstance abuse-vulnerability genes: genome scans for association, using 1,004 subjects and 1,494 single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1290–1300. doi: 10.1086/324467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QR, Drgon T, Walther D, Johnson C, Poleskaya O, Hess J, Uhl GR. Pooled association genome scanning: validation and use to identify addiction vulnerability loci in two samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11864–11869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500329102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C, Drgon T, Liu QR, Walther D, Edenberg H, Rice J, Foroud T, Uhl GR. Pooled association genome scanning for alcohol dependence using 104,268 SNPs: validation and use to identify alcoholism vulnerability loci in unrelated individuals from the collaborative study on the genetics of alcoholism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:844–853. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Walther D, Hess J, Uhl GR. Addiction molecular genetics: 639,401 SNP whole genome association identifies many "cell adhesion" genes. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:918–925. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Madden PA, Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hatsukami D, Pomerleau OF, Swan GE, Rutter J, Bertelsen S, Fox L, et al. Novel genes identified in a high-density genome wide association study for nicotine dependence. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:24–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Drgon T, Liu QR, Johnson C, Walther D, Komiyama T, Harano M, Sekine Y, Inada T, Ozaki N, et al. Genome-wide association for methamphetamine dependence: convergent results from 2 samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:345–355. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Fatusin OO, Liu QR, Contoreggi C, Li CY, Buck K, Crabbe J. "Higher order" addiction molecular genetics: convergent data from genome-wide association in humans and mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Li CY, Contoreggi C, Hess J, Naiman D, Liu QR. Molecular genetics of addiction and related heritable phenotypes: genome wide association approaches identify "connectivity constellation" and drug target genes with pleiotropic effects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:318–381. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annas GJ. Reforming informed consent to genetic research. Jama. 2001;286:2326–2328. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer JE, Rezaishiraz H, Head K, Cowell J, Bepler G, Aiken M, Cummings KM, Hyland A. Obtaining DNA from a geographically dispersed cohort of current and former smokers: use of mail-based mouthwash collection and monetary incentives. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:439–446. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001696583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfante R, Reed D, MacLean C, Kagan A. Response bias in the Honolulu Heart Program. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130:1088–1100. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrand R, Vedin A, Wilhelmsson C, Wilhelmsen L. Bias due to non-participation and heterogenous sub-groups in population surveys. J Chronic Dis. 1983;36:725–728. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(83)90166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beskow LM, Burke W, Merz JF, Barr PA, Terry S, Penchaszadeh VB, Gostin LO, Gwinn M, Khoury MJ. Informed consent for population-based research involving genetics. Jama. 2001;286:2315–2321. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EW, Steinberg KK, Khoury MJ, Thomson E, Andrews L, Kahn MJ, Kopelman LM, Weiss JO. Informed consent for genetic research on stored tissue samples. Jama. 1995;274:1786–1792. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.22.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criqui MH. Response bias and risk ratios in epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:394–399. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criqui MH, Austin M, Barrett-Connor E. The effect of non-response on risk ratios in a cardiovascular disease study. J Chronic Dis. 1979;32:633–638. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durfy SJ, Bowen DJ, McTiernan A, Sporleder J, Burke W. Attitudes and interest in genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility in diverse groups of women in western Washington. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:369–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Neufeld K, Chen LS, Cai G. A comparison of self-report and clinical diagnostic interviews for depression: diagnostic interview schedule and schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry in the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:217–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan GM, Porter KS, Agelli M, Kington R. Consent for genetic research in a general population: the NHANES experience. Genet Med. 2003;5:35–42. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, Blazer DG, Hough RL, Eaton WW, Locke BZ. The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area program. Historical context, major objectives, and study population characteristics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:934–941. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790210016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO, Schneider NG. Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J Behav Med. 1989;12:159–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00846549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, O'Hara BF, Persico AM, Gorelick DA, Newlin DB, Vlahov D, Solomon L, Pickens R, Uhl GR. Genetic vulnerability to drug abuse. The D2 dopamine receptor Taq I B1 restriction fragment length polymorphism appears more frequently in polysubstance abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:723–727. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090051009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persico AM, Bird G, Gabbay FH, Uhl GR. D2 dopamine receptor gene TaqI A1 and B1 restriction fragment length polymorphisms: enhanced frequencies in psychostimulant-preferring polysubstance abusers. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:776–784. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00483-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Liu QR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Walther D, Rose JE. Molecular genetics of nicotine dependence and abstinence: whole genome association using 520,000 SNPs. BMC Genet. 2007;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl GR, Liu QR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Walther D, Rose JE, David SP, Niaura R, Lerman C. Molecular genetics of successful smoking cessation: convergent genome-wide association study results. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:683–693. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont WD, Plummer WD., Jr Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:116–128. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90005-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont WD, Plummer WD., Jr Power and sample size calculations for studies involving linear regression. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:589–601. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(98)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons MJ, Bar JL, Panizzon MS, Toomey R, Eisen S, Xian H, Tsuang MT. Neuropsychological consequences of regular marijuana use: a twin study. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1239–1250. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704002260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Widiger TA. Personality Disorders and The Five Factor Model of Personality. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Li CY, Liu QR, Zhang PW, Li XM, Wei L, Uhl GR. OKCAM: an ontology-based, human-centered knowledgebase for cell adhesion molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D251–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]