Abstract

Angiogenesis is a hallmark of tumor development and metastasis and is now a validated target for cancer treatment. Overall, however, the survival benefits of anti-angiogenic drugs have, thus far, been rather modest, stimulating interest in developing more effective ways to combine anti-angiogenic drugs with established chemotherapies. This review discusses recent progress and emerging challenges in this field; interactions between anti-angiogenic drugs and conventional chemotherapeutic agents are examined, and strategies for the optimization of combination therapies are discussed. Anti-angiogenic drugs such as the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab can induce a functional normalization of the tumor vasculature that is transient and can potentiate the activity of co-administered chemoradiotherapies. However, chronic angiogenesis inhibition typically reduces tumor uptake of co-administered chemotherapeutics, indicating a need to explore new approaches, including intermittent treatment schedules and provascular strategies to increase chemotherapeutic drug exposure. In cases where anti-angiogenesis-induced tumor cell starvation augments the intrinsic cytotoxic effects of a conventional chemotherapeutic drug, combination therapy may increase anti-tumor activity despite a decrease in cytotoxic drug exposure. As new angiogenesis inhibitors enter the clinic, reliable surrogate markers are needed to monitor the progress of anti-angiogenic therapies and to identify responsive patients. New targets for anti-angiogenesis continue to be discovered, increasing the opportunities to interdict tumor angiogenesis and circumvent resistance mechanisms that may emerge with chronic use of these drugs.

Keywords: angiogenesis, VEGF, combination therapy, cancer treatment

Introduction

Angiogenesis is a highly regulated process, whereby new blood vessels form from pre-existing ones (1). In adult mammals, physiological angiogenesis is largely limited to the ovaries, uterus and placenta, with the turnover rate of vascular endothelial cells being very low in most other tissues. Pathophysiological angiogenesis is a characteristic of wound healing and diseased states, in particular cancer, where the number of proliferating endothelial cells increases significantly and the morphology of the vasculature is altered in multiple ways (2). For many types of tumors, as tumor cells undergo dysregulated proliferation, the tumor mass initially expands beyond the support capacity of the existing vasculature, leading to decreased levels of oxygen and nutrients and the accumulation of metabolic wastes. Tumor cells respond to this deterioration of the tumor microenvironment by up-regulating several pro-angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), placental growth factor (PLGF) and platelet-derived endothelial growth factor, which collectively activate quiescent endothelial cells and promote their migration into the tumor. This shift of the tumor microenvironment to an angiogenic state, or “angiogenic switch” (3), is an important rate-limiting factor in tumor development. Despite the active angiogenesis induced by tumor cell-derived pro-angiogenic factors, structural defects associated with the tumor vasculature often lead to inefficient blood perfusion in established tumors, which contributes to tumor hypoxia. Tumor metastasis is also regulated by angiogenesis, as well as by lymphangiogenesis, where new lymphatic vessels are formed from pre-existing ones (4). Tumor cell dissemination, the first step in tumor metastasis, requires access to both blood and lymphatic circulation. Once successfully extravasated, the survival and further colonization of the disseminated tumor cells is dependent on angiogenesis at the secondary site. Angiogenesis is thus a key factor in the development and metastasis of a variety of tumor types, and is an important hallmark of malignant disease. Moreover, angiogenesis presents unique opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer treatment, as first proposed by the late Judah Folkman more than 35 years ago (5).

The control of tumor angiogenesis is an integral part of the host defense response to tumor growth. Loss of endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors, such as endostatin and thromobospondin-1, leads to increased tumor angiogenesis and accelerates tumor growth in transgenic mouse models (6). In contrast, when angiogenesis is impaired and the expression of endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors is increased, tumors may enter a period of prolonged dormancy (7). Dormant tumors may be found in autopsy samples from trauma victims and in cancer patients that relapse after being disease-free for months or even years (8), indicating that tumors can exist as microscopic lesions for long periods of time without any clinical manifestation of disease. This dormancy may reflect the inability of these in situ tumors to disrupt or circumvent host anti-angiogenic defenses (9).

The inhibition of tumor growth by anti-angiogenic drugs has been achieved both in preclinical studies and in clinical trials, where promising anti-tumor responses have been reported for a variety of anti-angiogenic agents (Table 1) (10). Bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody and the first U.S. FDA-approved anti-angiogenesis drug, significantly increases overall survival or progression-free survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, non-small cell lung cancer and breast cancer when given in combination with conventional chemotherapeutic regimens (11–13) (Table 2). Renal cell carcinoma is a highly vascularized tumor that is associated with inactivation of the von-Hippel Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene and up-regulation of VEGF expression (14). Sunitinib, an anti-angiogenic drug that inhibits the VEGF receptor (VEGFR) tyrosine kinase, shows superior activity in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma when compared to the standard of care interferon-α treatment (15). Sunitinib is a multi-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (RTKI); it also provides significant clinical benefit for patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors, which relates, at least in part, to its c-KIT inhibitory activity (16). Sorafenib, an anti-angiogenic RTKI that also has Raf kinase inhibitory activity, has been approved for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and liver cancer (17, 18). Many other anti-angiogenic drugs are progressing through preclinical and clinical development, with more than 800 clinical trials presently underway (www.clinicaltrials.gov). Overall, however, the survival benefits of anti-angiogenic drugs have, thus far, been rather modest, leading to increased interest in developing more effective ways to combine anti-angiogenic drugs with traditional, cytotoxic chemotherapies. In this review, we discuss recent progress and some emerging challenges in the development of anti-angiogenic drugs for cancer treatment. Interactions between these novel drugs and conventional chemotherapeutic agents are examined, and strategies for the optimization of combination therapies are discussed.

Table 1.

Anti-angiogenesis agents

| Anti-angiogenesis agent | Description | |

|---|---|---|

|

Bevacizumab (Avastin) | Humanized anti-VEGF-A monoclonal antibody |

| Ranibizumab (Lucentis) | Anti-VEGF-A antibody Fab fragment | |

| Pegaptanib (Macugen) | RNA aptamer of 165-amino acid VEGF-A | |

| IMC-1121B | Human anti-VEGFR-2 monoclonal antibody | |

| DC101 | Mouse VEGFR-2-specific monoclonal antibody | |

| VEGF-Trap | Fusion protein including immunoglobulin domain of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 and human IgG1 Fc fragment | |

|

AEE788 | VEGFR-2 and EGFR inhibitor |

| Axitinib (AG-013736) | VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 inhibitor, also inhibits VEGFR-3, PDGFR-β, and c-KIT | |

| AG-013925 | VEGFR and PDGFR inhibitor | |

| Imatinib | Bcr-Abl fusion protein inhibitor, also inhibits PDGFR-β and c-KIT | |

| Vatalanib (PTK787/ZK22258) | VEGFR-2 inhibitor, also inhibits VEGFR-1, VEGFR-3 and PDGFR-β | |

| Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006, Nexavar) | Raf, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3 inhibitor, also inhibits PDGFR-β and c- KIT | |

| Semaxanib (SU5416) | VEGFR-2 inhibitor, also inhibits PDGFR | |

| SU6668 | VEGFR-2 inhibitor, also inhibits PDGFR-β, FGFR-1, and c-KIT | |

| SU11657 | VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 inhibitor, also inhibits PDGFR-α, PDGFR-β, and c-KIT | |

| Sunitinib (SU11248, Sutent) | VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 inhibitor, also inhibits PDGFR-α, PDGFR-β, and c-KIT | |

| Vandetanib (ZD6474, Zactima) | VEGFR-2 inhibitor, also inhibits VEGFR-3 and EGFR | |

| ZD2171 | VEGFR-2 inhibitor, also inhibits VEGFR-1, VEGFR-3, c-KIT, and PDGFR-β | |

| Angiostatin | Cleavage fragment of plasminogen | |

| Endostatin | Cleavage fragment of collagen XVIII | |

| Thrombospondin-1 | Extracellular glycoprotein |

Table 2.

Clinical studies of combination therapy with anti-angiogenesis treatment

| Subject | Anti-angiogenesis Treatment | Chemotherapy | Median Survival (months) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer, phase III | – | Irinotecan/fluorouracil/leucovorin | 15.6 | (11) |

| Bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) | Irinotecan/fluorouracil/leucovorin | 20.3a | ||

| Recurrent or advanced NSCLC, phase III | – | Paclitaxel/carboplatin | 10.3 | (12) |

| Bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) | Paclitaxel/carboplatin | 12.3a | ||

| Metastatic breast cancer, phase III | – | Paclitaxel | 25.2 | (13) |

| Bevacizumab (10 mg/kg) | Paclitaxel | 26.7b, c | ||

| Previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer, phase II | – | Fluorouracil/leucovorin | 13.8 | (81) |

| Bevacizumab (5 mg/kg) | Fluorouracil/leucovorin | 21.5d, e | ||

| Bevacizumab (10 mg/kg) | Fluorouracil/leucovorin | 16.1d | ||

| Previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer, phase III | – | Oxaliplatin/fluorouracil/leucovorin | 10.8 | (164) |

| Bevacizumab (10 mg/kg) | \ | 10.2b | ||

| Bevacizumab (10 mg/kg) | Oxaliplatin/fluorouracil/leucovorin | 12.9a | ||

| Previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer, phase III | – | Oxaliplatin/fluorouracil/leucovorin | 11.8 | (85) |

| Vatalanib (1250 mg) | Oxaliplatin/fluorouracil/leucovorin | 12.1b | ||

| Previously untreated NSCLC cancer, phase III | – | Carboplatin/paclitaxel | No significant difference | (86) |

| Sorafenib (400 mg) | Carboplatin/paclitaxel |

Median survival significantly different from chemotherapy alone treatment group.

No significant increase in overall survival compared to chemotherapy alone treatment group.

Progression-free survival significantly different from chemotherapy alone treatment group.

A trend of increased survival compared to chemotherapy alone treatment group.

A trend of increased survival compared to chemotherapy + bevacizumab (10 mg/kg) treatment group.

Anti-angiogenic Drugs and their Therapeutic Targets

Many genes, proteins and pathways have been identified as potential targets for anti-angiogenic agents, of which the VEGF/VEGFR signaling pathway has been studied most extensively. The binding of VEGF to VEGFR-2 is a critical step that stimulates the major pro-angiogenic activities of VEGF, including endothelial cell proliferation, migration, tube formation and capillary sprouting (19). More acute responses to VEGF include increased microvascular permeability and vasodilation (20). VEGF and VEGFR play an essential role in vascular development, as exemplified by the embryonic lethality of targeted disruptions in the genes coding for VEGF and VEGFR-2 (21). Other VEGF and VEGFR family members are important for lymphangiogenesis (22). VEGF is often over-expressed by tumors, where the vasculature shows greater sensitivity to inhibition of VEGF signaling than in normal tissues (23). Major pro-angiogenic VEGF isoforms (splicing variants) include VEGF121, VEGF165 and VEGF189, which bind with similar affinity to VEGFR but differ in their angiogenic activities (24, 25); VEGF165b is an endogenous anti-angiogenic isoform whose down-regulation in cancer is a marker of poor prognosis and metastatic potential (26, 27).

Several strategies have been employed to block VEGF/VEGFR signaling. In one approach, antibodies to VEGF or its receptor inhibit angiogenesis by blocking VEGF–VEGFR binding at the cell surface. Examples include bevacizumab, a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody (28), IMC-1121b, a human anti-VEGFR-2 monoclonal antibody, the anti-VEGF Fab fragment ranibizumab and the VEGF RNA aptamer pegaptanib (Table 1). In a second approach, the tyrosine kinase activity that is intrinsic to activated VEGFR and related pro-angiogenic receptors is inhibited by small molecule RTKIs, such as sunitinib, sorafenib, vatalanib, and axitinib (Table 1). Because of the structural similarities between VEGFR and other receptor tyrosine kinases, anti-angiogenic RTKIs often inhibit multiple tyrosine kinases (29). For example, sorafenib inhibits the tyrosine kinase activities of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, as well as those of platelet-derived growth factor-B (PDGF-B) receptor, Raf, Flt-3, and c-KIT, albeit with different affinities (30). Whereas the VEGFRs and PDGF-B receptor are important for angiogenesis, Raf kinase is central to the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway, which is constitutively activated in several human tumors, including renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and non-small cell lung cancer (31). Flt-3, a receptor tyrosine kinase that regulates hematopoiesis, is highly expressed in acute leukemia and may be a therapeutically useful target (32). c-KIT inhibition is important for the treatment of gastrointerstinal stromal tumors (33). Thus, the multiple receptor tyrosine kinase targeting activity of sorafenib provides an opportunity to interdict tumor growth by several independent mechanisms.

The tumor vasculature is frequently characterized by loss of intimate contact between pericytes and endothelial cells (34). This morphological defect may contribute to the selective vulnerability of tumor blood vessels to VEGF inhibition (35). A similar deficiency in pericyte-endothelial cell association is observed in mice with a disruption of the gene coding for PDGF-B, an endothelial cell-derived pro-angiogenic factor required for the recruitment of pericytes to immature blood vessels (36), suggesting that the PDGF-B signaling pathway may be a target for anti-angiogenesis (37). However, RIP-Tag2 pancreatic tumors, which are typically non-metastatic, develop distant metastases when grown in Pdgfb-deficient mice (38), raising the possibility that PDGF-B pathway-selective inhibitors might actually enhance tumor metastasis. Co-inhibition of VEGF and PDGF-B signaling does, however, decrease leakiness and regresses tumor blood vessels (39), which reduces the access of metastatic cells to the circulatory system and limits the potential of PDGF-B inhibition to elicit a pro-metastatic response. Further studies are required to investigate these potential differences between PDGF-B inhibition and VEGF/PDGF-B co-inhibition and their impact on tumor metastasis.

VEGF induces endothelial cell expression of delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4), a Notch receptor ligand that activates a negative-feedback mechanism to restrain the sprouting and branching of new blood vessels (40). Soluble Dll4-IgG fusion protein blocks Dll4 activity and increases tumor vascularity. Nevertheless, this treatment inhibits tumor growth, as a majority of the newly formed tumor vessels are not perfused with blood. Thus, tumor blood flow can be inhibited when excessive angiogenesis leads to the formation of dysfunctional blood vessels.

Several established drugs have been found to have anti-angiogenic activity. These include therapeutic agents that are ligands of the nuclear receptors PPARα (fibrate hypolipidemic drugs) and PPARγ (thiazolidinedione anti-diabetics), both of which are expressed in endothelial cells. Ligands of PPARγ induce anti-tumor responses associated with a decrease in tumor microvessel density and VEGFR expression, and an increase in endothelial cell expression of CD36, a receptor for the endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor thrombospondin-1 (41). Ligands of PPARα inhibit endothelial cell proliferation and tumor angiogenesis by down-regulating the expression of cytochrome P450 2C family epoxygenases, which convert arachidonic acid to epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, which are potent angiogenic lipids (42). In addition, drugs directed against oncogenes can induce anti-angiogenic responses by down-regulating pro-angiogenic factors or by directly targeting the altered expression of proto-oncogenes in tumor-associated endothelial cells (43, 44). This crosstalk between angiogenic and oncogenic signaling pathways provides a rationale for combining angiogenesis inhibitors with other targeted anticancer agents (45, 46). Additional therapeutic targets and strategies for anti-angiogenesis will likely be identified as our understanding of the cellular and molecular basis for angiogenesis increases.

Endogenous Angiogenesis Inhibitors

A large number of endogenous anti-angiogenic factors have been identified, including angiostatin, endostatin and thrombospondin-1 (47). Angiostatin is a 38-kDa fragment of plasminogen that can be secreted by a primary tumor and suppresses the growth of metastases in experimental animal models (48). Endostatin, a 20 kDa fragment of collagen XVIII and the most extensively studied endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor, regulates a variety of pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors (49) and a large downstream signaling network (50). Individuals with Down syndrome have elevated levels of circulating endostatin along with the increased gene dosage on chromosome 21, and this overexpression is associated with a very low incidence of solid tumors (51).

Thrombospondin-1 is a disulfide-linked homotrimeric adhesive glycoprotein that mediates cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions (52). It is a major component of platelet α-granules, and its release from activated platelets significantly increases plasma thrombospondin-1 levels (53). Metronomic chemotherapy (see below) substantially increases plasma thrombospondin-1 levels in tumor-bearing mice (54). Thrombospondin-1 protein can be deposited in the extracellular matrix by endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, monocytes, and some tumor cells (55). The anti-angiogenic activity of thrombospondin-1 is at least in part mediated by its endothelial cell surface receptor protein, CD36, and involves the induction of Fas ligand in proliferating endothelial cells. The latter cells undergo apoptosis when the corresponding cell surface receptor, Fas protein, is up-regulated by pro-angiogenic factors, such as VEGF, bFGF, and IL-8 (56). New tumor blood vessels, which are continuously formed via angiogenesis, have elevated levels of Fas protein compared to resting blood vessels, which helps to explain the tumor blood vessel-selectivity of thrombospondin-1. Thrombospondin-1 also inhibits the mobilization of VEGF from its extracellular matrix reservoir, suppresses endothelial cell migration, and decreases blood flow by blocking nitric oxide-induced relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells. A peptide mimetic of thrombospondin-1, ABT-510, is currently in clinical development as an angiogenesis inhibitor (57). A related endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor, thrombospondin-2, also binds to CD36 and suppresses tumor growth via an anti-angiogenic mechanism (52).

Targeting Tumor Metastasis by Anti-angiogenesis

Tumor metastasis is an important but poorly understood target of anti-angiogenesis therapy. The growth of tumor metastases, like that of the primary tumor, requires angiogenesis and can be targeted at multiple steps (Figure 1) (9). Tumors shed millions of cells into blood and lymphatic circulation in a process that requires penetration through a multi-layer barrier comprised of pericytes, base membrane and endothelial cells. Anti-angiogenesis prunes immature blood vessels and reduces vascular permeability, which, in turn, may limit the shedding of metastatic cells from the primary tumor. In patients with colorectal cancer, the number of intravasated tumor cells is positively correlated with tumor vascularity (58), suggesting that a decrease in tumor blood vessel density may translate into decreased access of tumor cells to the general circulation. Tumor cell intravasation is inhibited by low concentrations of endostatin in a chicken chorioallantoic membrane intravasation assay (59). Human tumor xenografts induce the remodeling of zebrafish vasculature and open holes in blood vessels through which tumor cells intravasate, and this process can be blocked by the anti-angiogenic RTKI semaxanib (60).

Figure 1. Inhibition of tumor metastasis by anti-angiogenic drugs.

Tumor metastases can be targeted by angiogenesis inhibitors at multiple steps. Prunning of tumor blood vessels and decreased vascular permeability following anti-angiogenic drug treatment limit the shedding of metastastic cells from the primary tumor (1). Inhibition of VEGFR-1 or VEGFR-2 suppresses the attachment of disseminated tumor cells to metastatic niches (2). Growth of avascular micrometastases to macrometastases also requires angiogenesis and can be inhibited by anti-angiogenic agents (3).

The “seed and soil” hypothesis posits that tumor cells that have entered the circulatory system need to extravasate and colonize at pre-determined locations (61). Bone marrow-derived, VEGFR-1-positive progenitor cells are a critical factor in the assembly of the premetastatic niche, where VEGFR-2-positive endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) may also be involved (62). The inhibition of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 by the anti-angiogenic RTKI sunitinib limits the attachment of tumor cells to these premetastatic sites (62). In sentinel lymph nodes of tumor-bearing mice, vascular reorganization and enrichment of blood vessels also occur before the arrival of metastatic cells (63). As noted above, micrometastases can remain dormant at secondary sites over a long period of time. Angiogenesis inhibition is proposed as the underlying mechanism that blocks the progression of these avascular micrometastases to macrometastases (64). Indeed, angiostatin was first discovered because of its anti-metastatic activity (48). EPCs are essential in providing pro-angiogenic factors critical for metastasis development, as indicated by the suppression of micrometastasis growth upon inhibition of EPC mobilization in preclinical studies (65). Moreover, selective inhibition of the vascular remodeling genes matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -2, using siRNA or small-molecule inhibitors, significantly reduces the metastatic potential of tumor cells (66). These anti-metastatic effects of anti-angiogenic agents need to be confirmed in human patients with the incorporation of metastasis monitoring into clinical studies.

Tumor hypoxia not only induces angiogenesis, but is also an important regulator of tumor cell mobility (4). Deletion of the gene encoding hypoxia-inducible fator-1α (HIF-1α) significantly reduces the metastatic potential of tumor cells in a transgenic mouse model (67).

Counterintuitively, the increase in tumor hypoxia and HIF-1α expression that accompanies sustained angiogenesis inhibition may promote tumor cell invasion and migration, as seen in some clinical studies (68, 69). This finding suggests it may be beneficial to co-inhibit HIF-1α signaling in combination with anti-angiogenesis. Considering the dominant role of metastasis in cancer mortality, long-term administration of anti-angiogenesis drugs that are effective in maintaining an anti-metastatic state could provide important clinical benefit.

Combination of Anti-angiogenics with Conventional Cancer Treatments

Despite their promising activity in patients with a variety of cancers, current anti-angiogenic treatments have provided only a modest survival benefit. Thus, there is increasing interest in combining anti-angiogenic drugs with existing therapeutic modalities. As anti-angiogenics are generally cytostatic rather than cytoreductive, combinations involving conventional cytotoxic chemotherapies may be useful for maximizing therapeutic activity. Of note, many anti-angiogenic drugs can be administered over extended periods of time safely and with manageable toxicity as compared to standard maximum tolerated dose (MTD) chemotherapies, which are often accompanied by severe adverse effects.

The low vascularity, poor organization, and abnormal morphology of the tumor vasculature leads to inefficient transport of oxygen and therapeutic drugs into tumors (70). This problem is exacerbated by the high interstitial fluid pressure within tumors, which is largely a consequence of the increased deposition of fibrin and other plasma proteins in the tumor stroma in response to the increased microvascular permeability induced by VEGF, coupled with the absence of efficient lymphatic drainage (19). The high interstitial fluid pressure not only promotes the dissemination of tumor cells to the peri-tumoral space, but may limit the delivery of chemotherapeutics into the tumor. Following anti-angiogenesis treatment, the tumor vasculature may undergo morphological normalization, whereby immature blood vessels are pruned, blood vessel tortuosity and dilation decrease, and a closer association between pericytes and endothelial cells is induced (71). Tumor blood vessel leakage, vascular permeability, and interstitial fluid pressure all decrease, which alleviates edema in cancer patients and provides an important clinical benefit (72–75). Many angiogenesis inhibitors induce these morphological and permeability changes, suggesting they represent a general response to the inhibition of VEGF signaling.

Counterintuitively, in preclinical studies of bevacizumab and certain other angiogenesis inhibitors, an increase in vascular patency has been observed, with an increase in tumor blood perfusion and drug uptake and a decrease in tumor hypoxia (76–80) (Supplementary Table 11). These improvements in overall tumor vascular function indicate that blood vessels that survive anti-angiogenic drug treatment have increased transport capability, which more than compensates for the decrease in the total number of patent blood vessels (71). This increase in vascular patency is transient, however, corresponding to a “window of opportunity” during which anti-angiogenics may be combined with classical chemotherapeutics so as to increase overall tumor cell exposure to cytotoxic drugs. In this scenario, the cytotoxic drug is the major determinant of the overall therapeutic response. The optimal dosing and scheduling of the anti-angiogenic agent becomes critical, as excessive suppression of the tumor vasculature may prematurely close the normalization window. Indeed, improved clinical responses are observed when conventional chemotherapy is combined with low dose bevacizumab as compared to high dose bevacizumab (81) (Table 2). In another example, in preclinical studies of sunitinib, interstitial fluid concentrations of the cancer chemotherapeutic drug temozolomide were increased when tumors were pretreated with sunitinib at 10 mg/kg but not at 40 mg/kg (79). To optimize the benefit of vascular normalization-enhanced tumor drug delivery, the duration of the open window during anti-angiogenesis treatment needs to be better defined, e.g., using non-invasive imaging techniques that monitor tumor blood flow (82). Chronic treatment with neutralizing antibodies to VEGF and VEGFR eventually reduces tumor blood perfusion and increases tumor hypoxia in experimental animal studies (83, 84), suggesting uninterrupted treatment with the anti-angiogenic drug, although perhaps maximally effective as a monotherapy, may not be optimal for tumor vascular normalization-enhanced combination chemotherapy (Figure 2). Intermittent anti-angiogenesis treatment schedules need to be investigated to ascertain whether, and under which conditions, repeated cycles of vascular normalization and increased drug uptake might be achieved. Furthermore, the potential of such cycles of re-normalization of tumor vasculature to facilitate tumor cell recovery from cytotoxic drug treatment during the chemotherapeutic drug-free period needs to be carefully considered. Finally, studies are needed to verify that the functional normalization and increase in drug uptake seen in preclinical studies also occurs in the clinic and contributes to the enhanced responses seen in patients treated with chemotherapy in combination with bevacizumab.

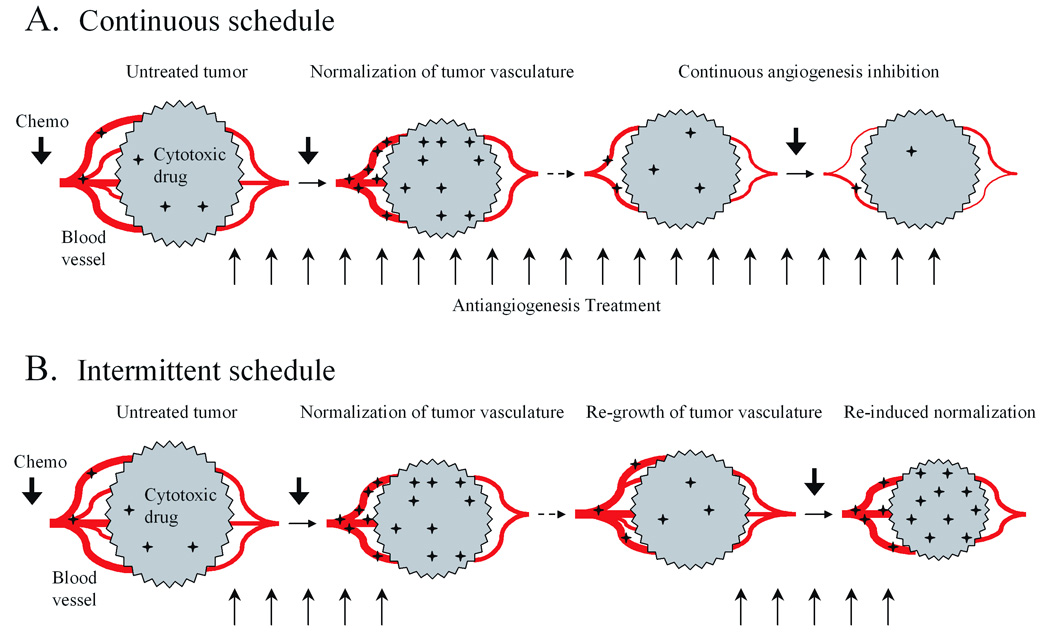

Figure 2. Effect of anti-angiogenesis treatment schedule on chemotherapeutic drug uptake by tumors.

A, some anti-angiogenic drugs induce functional normalization of tumor vasculature resulting in a transient increase in tumor drug uptake. However, continuous treatment with angiogenesis inhibitors ultimately leads to a decrease in tumor blood flow and decreased tumor uptake of co-administered cytotoxic drugs. B, intermittent anti-angiogenesis treatment schedules may allow for the recovery of tumor vascular patency between each cycle of drug administration and thereby minimize the adverse effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on the delivery of cytotoxic agents to tumors. However, the potential that such cycles of re-normalization of the tumor vasculature might facilitate tumor cell recovery from cytotoxic drug treatment needs to be carefully considered. Vertical arrows under each panel indicate repeated dosing with anti-angiogenic drugs.

In contrast to bevacizumab, the RTKIs sorafenib and sunitinib show significant anti-tumor activity as monotherapies in phase III clinical trials (15–18). However, combinations of sorafenib or vatalanib with conventional chemotherapy do not increase patient survival (85, 86) (Table 2). This raises the question of whether these RTKIs differ from the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab in their anti-angiogenic actions and/or in their ability to facilitate cytotoxic drug delivery. Similar to bevacizumab, RTKIs can induce morphological normalization of the tumor vasculature in both preclinical and clinical studies (75, 87, 88), and in some cases the functionality of individual surviving blood vessels is improved (73, 89, 90). However, whereas anti-VEGF and anti-VEGFR antibodies can induce the transient increase in tumor drug uptake and oxygenation discussed above, small-molecule anti-angiogenic RTKIs frequently elicit the opposite effects, i.e., decreased drug uptake and increased tumor hypoxia, as seen in several preclinical studies (91–95) (Supplementary Table 1). Conceivably, the lack of an increase in vascular patency of the RTKI-treated tumors could result from the use of RTKI drug doses and schedules that are designed to maximize anti-angiogenesis but are sub-optimal with respect to vascular normalization. Alternatively, intrinsic differences between the actions of VEGF neutralizing antibodies and RTKIs could be a critical factor. Of note, VEGFR-directed RTKIs simultaneously inhibit paracrine and autocrine VEGF signals (96), and in some cases could also target PDGF-B receptor tyrosine kinase activity, whereas anti-VEGF and anti-VEGFR-2 antibodies selectively block paracrine VEGF signaling. Rapid decreases in tumor blood perfusion and tumor drug uptake can occur within hours of a single dose of anti-angiogenic RTKI treatment, i.e., well before the inhibition of VEGF/VEGFR signaling leads to endothelial cell killing and the resultant morphological changes in tumor blood vessels (92, 94, 97). This suggests that the initial response to anti-angiogenic RTKI treatment involves vasoconstriction of existing tumor blood vessels, perhaps due to decreased production of nitric oxide and prostacyclins, which mediate the acute vasodilatory effects of VEGF. Studies are needed to clarify whether the distinct VEGF inhibitory actions of VEGF/VEGFR neutralizing antibodies and anti-angiogenic RTKIs lead to different effects on endothelial cell nitric oxide synthesis and nitric oxide release (98), and if the co-inhibition of PDGF-B receptor by some RTKIs alters the response of smooth muscle cells to a nitric oxide signal. In addition, although decreased vascular permeability following VEGF/VEGFR inhibition reduces tumor interstitial fluid pressure, it is unclear how this affects the extravasation of drugs into the tumor, in particular macro-molecular therapeutics.

The level of tumor oxygenation and drug uptake is primarily determined by the total number of functional blood vessels connecting to and within the tumor and by the transport efficiency of each individual blood vessel. As a result, tumor hypoxia and decreased drug uptake are both likely to result when strong anti-angiogenic RTKIs induce rapid vasoconstriction and an extensive loss of tumor blood vessels. Nevertheless, the overall therapeutic response may be improved by combining RTKIs with conventional chemoradiotherapies by using appropriately designed treatment schedules. The angiogenesis inhibitor axitinib increases tumor hypoxia without functional normalization of the tumor vasculature, which would be expected to reduce tumor cell sensitivity to radiation therapy. However, anti-tumor activity is enhanced in tumor-bearing mice when axitinib is combined with radiation treatment (91). Moreover, an improved anti-tumor response can be achieved by combining axitinib with the cancer chemotherapeutic prodrug cyclophosphamide, despite a substantial decrease in tumor uptake of the active chemotherapeutic drug (97). Enhanced anti-tumor activity is also observed in combination therapies with the anti-angiogenic RTKI vandetanib under conditions where tumor blood flow and drug uptake are both decreased (95). Clearly, in these cases, where the RTKI elicits a strong anti-angiogenic response, tumor cell exposure to the cytotoxic agent is not the sole determinant of overall anti-tumor activity. Rather, the anti-angiogenic RTKI may induce a direct anti-tumor response through angiogenesis inhibition-induced tumor cell starvation, which is independent of, but complementary to the cytotoxic response to chemo/radiotherapy (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Balance between the antitumor activity of an anti-angiogenesis inhibitor and a co-administered cytotoxic drug determines the outcome of the combination therapy.

Tumor cell exposure to cytotoxic drugs can be reduced by anti-angiogenesis treatment, but the therapeutic outcome of the combination therapy depends on the relative contribution of each treatment regimen to overall antitumor activity. A, for tumors that are highly sensitive to angiogenesis inhibition, anti-angiogenesis may dominate the therapeutic activity of the combination treatment such that anti-angiogenesis-induced tumor cell starvation enhances chemotherapeutic drug action, despite a decrease in drug uptake. B, in contrast, for tumors that have limited intrinsic responsiveness to angiogenesis inhibition, the cytotoxic drug becomes the major determinant of the overall antitumor effect, and anti-angiogenesis may compromise antitumor activity by decreasing chemotherapeutic drug uptake. Model is based on data presented elsewhere (92, 97).

The net outcome of a combination therapy is determined by the balance between the tumor cell starvation effect of the RTKI and the decrease in tumor cytotoxicity due to the decrease in chemotherapeutic drug exposure (Figure 3). When anti-angiogenesis dominates a tumor’s response to a combination therapy, optimal anti-tumor activity can be expected when a strong anti-angiogenic agent is used to maximize angiogenesis inhibition. In contrast, when the cytotoxic drug is the predominant therapeutic factor, anti-angiogenesis may compromise chemotherapeutic drug uptake and thus decrease anti-tumor activity (Figure 3B). In this case, the combination therapy needs to be designed carefully with respect to: 1) the choice of anti-angiogenic drug (e.g., anti-VEGF antibody vs. VEGFR-selective RTKI vs. multi-targeted RTKI) and its dose; and 2) the schedule of drug administration, which may involve anti-angiogenic drug treatment on either a continuous or an intermittent schedule (Figure 2). Optimization of drug sequencing will also be required, with the choice between neoadjuvant and adjuvant anti-angiogenesis treatment likely to vary with the tumor (97) and with the chemotherapeutic drug. As the functional normalization window induced by VEGF or VEGFR-neutralizing antibody ultimately closes with continued anti-angiogenesis treatment, the balance between increased tumor cell starvation and decreased cytotoxic drug exposure may also become an important determinant of the effectiveness of combination therapies that utilize this class of anti-angiogenic drugs.

In addition to the potentiation of chemotherapy by anti-angiogenesis, discussed above, the activity of anti-angiogenesis drugs can be enhanced by cytoreductive treatments. For example, both radiation treatment and chemotherapy can augment the sensitivity of tumor blood vessels to VEGF inhibition, which leads to increased growth delay of human tumor xenografts in combination therapy settings (99, 100). When administered using an MTD schedule, conventional chemotherapeutic drugs not only damage tumor cells; they also kill proliferating cells in normal tissues, which mandates the introduction of a drug-free recovery period between treatment cycles. However, during this recovery period, both tumor cells and tumor-associated endothelial cells initiate damage repair, leading to tumor regrowth and in some cases the emergence of a population of drug-resistant tumor cells, an important cause of treatment failure (101). This tumor repair process is another potential target for anti-angiogenesis. Bone marrow-derived EPCs have been detected in tumor blood vessels, although their precise contribution to tumor angiogenesis is uncertain (102, 103). In preclinical studies, anti-angiogenesis decreases the number of circulating EPCs, which are mobilized by bolus administration of cytotoxic drugs or vascular disruption agents (104–106). Blocking EPC mobilization by pretreatment with the anti-angiogenic agents DC101 or axitinib increases the anti-tumor activity of the combination treatment (106, 107). This association between circulating EPC inhibition and the efficacy of the combination treatment warrants further investigation in a clinical setting.

Another important consideration for the combination of anti-angiogenesis treatment with conventional chemotherapy is the potential for overlapping toxicities. Hypertension is a frequently observed side effect of anti-angiogenesis, which can result from the decrease in nitric oxide production that follows VEGF deprivation (108). Multi-receptor tyrosine kinase targeting could, however, lead to additional toxicities not seen with the VEGF-specific bevacizumab (109, 110), suggesting the utility of RTKIs that are more VEGFR-selective, such as axitinib (111, 112). Neutropenia has been observed in patients treated with the multi-RTKI sunitinib (113, 114), which could be mediated by its non-VEGFR inhibitory effects. Moreover, an increase in chemotherapy-associated neutropenia is seen with the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab (115). Thus, for this and other anti-angiogenic agents, the selection of drug and treatment schedule should be carefully considered when designing combination therapies that include myelosuppressive chemotherapeutic drugs.

Provascular Strategies

Pharmacokinetic modulation designed to increase tumor uptake of chemotherapeutic drug has been investigated with several agents, including botulinum toxin, nicotinamide, and various vasodilatory drugs (116). The utility of vasodilators as chemosensitizing agents depends on the functional role of smooth muscle cells in the tumor vasculature. When smooth muscle cells surrounding tumor blood vessels regulate tumor blood flow resistance, transient relaxation of these cells may temporarily increase blood flow through the tumor (117). However, as normal tissue blood vessels are highly sensitive to vasodilation, treatment of tumor-bearing mice with systemic vasodilators, such as hydralzaine, decreases blood flow resistance in normal tissues to a greater extent than in tumors, leading to a reduction in tumor blood supply and an increase in tumor hypoxia (118). Therefore, methods to selectively dilate tumor blood vessels are required, such as local low-dose radiation or the use of endothelin receptor antagonists (116). As tumor vascular patency and drug uptake decrease following chronic anti-angiogenesis treatment, intermittent administration of tumor-selective vasodilators prior to each cycle of chemotherapeutic drug treatment might be useful in transiently increasing tumor blood perfusion, thereby increasing tumor cell exposure to cytotoxic agents, while at the same time retaining the tumor cell starvation effect of continuous anti-angiogenesis treatment. In addition, when the resistance to tumor blood flow is not regulated by smooth muscle cells, systemic delivery of a vasoconstrictor, rather than a vasodilator, may be used to indirectly increase blood flow to the tumor, based on the premise that normal but not tumor blood vessels remain sensitive to vasoconstrictors (119). These treatments can increase blood pressure, which needs to be monitored carefully.

Anti-angiogenic Effects of Metronomic Chemotherapy

Metronomic chemotherapy refers to the administration of cytotoxic drugs at a lower dose but increased frequency without prolonged drug-free breaks, as compared to traditional MTD anticancer drug treatment schedules (120). Metronomic drug treatments have shown promising therapeutic activity using drug administration schedules that range from repeated administration every 6–7 days, to daily or even continuous drug treatment (120). With several cancer chemotherapeutic drugs, including cyclophosphamide, docetaxel and vinblastine, metronomic treatment schedules induce a significant anti-angiogenic response. Preclinical studies of chemotherapy-resistant tumor models have shown that tumor cell apoptosis is preceded by increased death of tumor-associated endothelial cells, indicating that endothelial cells are a primary target of metronomic chemotherapy (121). This reflects the high intrinsic sensitivity of endothelial cells to certain cytotoxic drugs (122). Toxicities to normal tissues are absent or low-grade, as seen both in preclinical and in clinical studies, indicating tumor specificity for the anti-angiogenic actions of metronomic chemotherapy (123, 124). In several preclinical studies, expression of the endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor thrombospondin-1 increases significantly during metronomic cyclophosphamide treatment, and anti-tumor activity is substantially reduced in its absence (54, 92, 125, 126). Metronomic cyclophosphamide also reduces tumor-induced immune tolerance (127), and correspondingly, synergistic anti-tumor activity results when metronomic cyclophosphamide is combined with a tumor-targeted immunotherapy (128).

Several approaches have been investigated to integrate the cytoreductive activities of conventional, MTD chemotherapy with the anti-angiogenic effects of metronomic chemotherapy. Administration of cyclophosphamide at an MTD/bolus dose followed by cyclophosphamide treatment on a metronomic schedule gives superior anti-tumor activity compared to either schedule alone in experimental animal studies (129, 130). The anti-tumor activity of metronomic cyclophosphamide can also be enhanced by intratumoral gene transfer of a cyclophosphamide-activating liver cytochrome P450 enzyme (131, 132), where liver-derived cyclophosphamide metabolites dominate the anti-angiogenic activity of the combination treatment, while drug-induced tumor cell death is substantially increased by intratumoral prodrug activation (126). Metronomic chemotherapy can also be combined with other anti-angiogenic agents. In a phase II clinical trial, co-administration of metronomic cyclophosphamide and bevacizumab resulted in superior anti-tumor activity when compared to historic controls (133). The outcome of therapies that combine small-molecule anti-angiogenic RTKIs with metronomic chemotherapy is more difficult to predict, as either increased or decreased anti-tumor activity can be achieved, with the latter response perhaps reflecting a decrease in tumor exposure to the cytotoxic drug and/or blocking of thrombospondin-1 induction in host cells (92, 129).

Surrogate Markers for Anti-angiogenesis

The toxicity-defined approach to drug dose development, commonly used for cancer chemotherapeutic drugs, may not be suitable for anti-angiogenics. For example, endostatin displays a U-shaped dose-response curve, with the conventional MTD dose being ineffective (134). In combination therapies where the efficacy of chemotherapy is enhanced by anti-angiogenic drug-induced normalization of tumor blood vessels, excessive inhibition of tumor vasculature function may decrease penetration of the co-administered chemotherapeutic drug, as discussed above. Surrogate markers are thus particularly important for monitoring anti-angiogenic activity and could help predict a given patient’s response to drug treatment (135).

One marker for tumor angiogenesis, microvessel density, is quantified by counting the number of blood vessels in a tumor section after staining with antibodies to an endothelial cell-specific marker protein, such as CD31, CD34, CD105, CD146, or von Willebrand factor (136). Tumor microvessel density is an independent prognostic factor for a variety of human tumors, where high vascular density is often associated with poor prognosis following surgery or conventional chemoradiotherapy (137). Tumor vascular density reflects the balance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors within the tumor microenvironment and is influenced by many factors including the availability of oxygen and nutrients (138). Highly vascularized tumors are generally considered to be more sensitive to a decrease in blood supply and are therefore expected to be highly responsive to anti-angiogenic drugs, while hypovascularized tumors are viewed as more hypoxia-tolerant and therefore less sensitive to anti-angiogenesis. However, poorly vascularized tumors can respond well to angiogenesis inhibition, as seen in several preclinical studies (97, 139, 140). Conceivably, treatment of such poorly vascularized tumors with anti-angiogenics may suppress an already low blood supply to the point where continued tumor growth becomes unsustainable. Further study is required to determine whether tumor microvessel density is a useful predictor of tumor response to anti-angiogenesis treatment. Changes in tumor cell density that follow drug treatment may further complicate the interpretation of tumor microvessel density measurements (138).

Blood vessel size and vascular coverage area have both been used as surrogate markers for drug-induced anti-angiogenesis. However, because tumor vasculature is often poorly perfused, more useful information about vascular function may be obtained from direct measurements of blood vessel patency. This can be achieved by intravenous injection of probe molecules, such as tomato lectin lycopersicon esculentum and the fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342, which bind to the luminal surface of endothelial cells in perfused blood vessels (tomato lectin) and to tumor cells in close proximity to these blood vessels (Hoechst 33342), respectively (78, 87, 141). High molecular weight tracers, such as fluorescence-labeled dextran, albumin, antibodies and microspheres, have also been used to detect and measure the leakiness of tumor blood vessels (38, 74, 89).

Tumor oxygenation reflects the balance between oxygen delivered to the tumor by the blood supply and its consumption in local metabolic activities, and is an important parameter for assessing the functionality of the tumor vasculature. Intratumoral oxygen levels can be measured using polarographic needle electrodes, EPR oximetry and hypoxia-specific dyes, such as pimonidazole (142). However, caution should be applied when using hypoxia-specific dyes to monitor tumor hypoxia induced by anti-angiogenesis, which can inhibit penetration of the dye itself (97). Interstitial fluid pressure, which contributes to the reduced penetration of drugs into solid tumors, can be monitored using specific needle probes (143) and may be an indicator of the effectiveness of anti-angiogenesis treatments with respect to improving drug delivery (74). Quantification of intratumoral drug concentrations provides a more direct measure of the impact of anti-angiogenesis treatments on tumor drug uptake (79, 92). For therapeutic agents with intrinsic autofluorescence (e.g. doxorubicin), intratumoral drug distribution can be visualized directly. Non-invasive imaging techniques can provide real time monitoring of fluctuations in tumor blood volume and flow rate and the accumulation of tracer molecules following anti-angiogenesis. Magnetic resonance imaging, X-ray computed tomography and ultrasound imaging provide high spatial resolution, and positron emission tomography can be used to detect both tumor blood perfusion and glucose metabolism in both preclinical and clinical studies (82).

Several other surrogate markers for anti-angiogenesis have been investigated. Pretreatment plasma levels of VEGF correlate with the survival benefit of bevacizumab treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (144). Increased VEGF and decreased soluble VEGFR-2 levels in plasma have been observed in patients treated with anti-angiogenesis drugs (75, 145). However, changes in the plasma levels of these factors may not be very informative for the measurement of therapeutic responses in tumors, given the significant contributions that normal tissues make to such changes, as revealed by a recent preclinical study (146). Circulating endothelial cells (CECs) and EPCs have been investigated as alternative blood markers for anti-angiogenic activity. Decreases in viable EPC counts in blood occur following treatment with DC101, axitinib, or metronomic chemotherapy in experimental animal models, and these changes directly correlate with anti-tumor response (106, 107, 147). In rectal cancer patients, the number of viable CECs decreases following bevacizumab treatment (145). Furthermore, in breast cancer patients treated with metronomic chemotherapy, a significant correlation was observed between clinical benefits and an increased fraction of apoptotic CECs (148). Standardized surface markers are needed before the utility of these markers can be evaluated more widely (149).

Resistance to Anti-angiogenic Drugs

Tumors may circumvent anti-angiogenesis by multiple mechanisms, which include changes in both tumor cells and in tumor-associated host stromal cells (150). Tumor-associated endothelial cells and pericytes, both of which can be primary targets of anti-angiogenesis treatment, are classically viewed as genetically stable and unlikely to develop drug resistance (151). However, more recent studies have revealed that the expression profile of tumor-associated endothelial cells is distinct from normal endothelial cells (152) and can be tumor type-dependent (153), with many tumor endothelial cells being cytogenetically abnormal (154). Tumor-associated pericytes may also show abnormal morphology and alterations in marker protein expression compared to their normal tissues counterparts (34), although it is unclear how these tumor-associated genetic or epigenetic changes might affect the sensitivity of endothelial cells or pericytes to angiogenesis inhibitors.

Resistance to VEGF inhibition can be mediated by the increased expression of other angiogenic factors. High-level expression of VEGF, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, bFGF, PDGF-A, TGFα and angiopoietin-2 has been observed in advanced human neuroblastomas (155). Continuous treatment of RIP-Tag2 tumors with antibodies to VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 initially leads to stable disease, but is followed by the development of resistance to the VEGFR blockade with up-regulation of the angiogenic factors FGF, ephrin, and angiopoietin (156). Interestingly, endostatin suppresses the expression of bFGF and ephrin-A1 (49), suggesting that the combination of this endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor with inhibitors that target VEGF signaling may suppress the development of drug resistance. Up-regulation of PLGF has been observed following VEGF deprivation using either anti-angiogenic neutralizing antibodies or RTKIs (75, 145, 146), and the efficacy of anti-VEGFR-2 treatment can be improved by combination with anti-PLGF antibody in experimental animal studies (157). Enhanced anti-angiogenic effects have also been observed by combining VEGFR inhibitors and PDGF receptor inhibitors (39, 129). In preclinical studies, crosstalk between bFGF and PDGF-B can synergistically promote tumor angiogenesis and metastasis (158), which further underscores the importance of inhibiting multiple angiogenic pathways in cancer treatment.

In addition to the above changes in the complement of angiogenic factors in response to anti-angiogenic drug treatment, the intrinsic tolerance of tumor cells to hypoxia or an acidic microenvironment, as well as hypoxia-induced tumor cell invasion and metastasis, may also increase, further limiting the efficacy of anti-angiogenesis (159). Alternatively, in some highly vascularized organs, such as brain, liver and lung, tumor cells may co-opt existing normal blood vessels and grow around them (160–162). Not only does the growth of the tumor become angiogenesis-independent, but the co-opted normal blood vessels will be less sensitive to the anti-vascular actions of anti-angiogenesis drugs, which can lead to resistance to anti-angiogenesis and can also obscure detection by techniques such as contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, which depends on the extravasation of contrast agents from leaky tumor blood vessels. Furthermore, as first observed in melanoma and subsequently reported in several other tumor types, tumor cells can form vessel-like structure by vasculogenic mimicry (163). The response of such tumor cell vascular networks to anti-angiogenesis agents is unknown, and their effects on drug delivery in combination therapy require further investigation. Given the anticipation that anti-angiogenic drugs entering into clinical practice will ultimately be given to patients long-term, it is important to understand the mechanisms of drug resistance that these drugs elicit, and whether cross-resistance amongst anti-angiogenic drugs can be anticipated.

Conclusions

Multiple therapeutic approaches have been developed to inhibit tumor angiogenesis, and better, more reliable surrogate markers are needed to assess their effectiveness in individual patients. The projected chronic administration of anti-angiogenesis drugs calls for a better understanding of their anti-tumor and anti-vascular effects and the mechanisms that may lead to drug resistance. Morphological normalization of the tumor vasculature is widely observed following angiogenesis inhibition. Preclinical studies indicate that functional improvement of tumor blood perfusion can be induced by some anti-angiogenic agents, with the potential to increase tumor cell exposure to co-administered cytotoxic drugs. However, for other anti-angiogenic drugs, tumor vascular patency decreases, leading to an increase in tumor hypoxia and a decrease in cytotoxic drug uptake. Nevertheless, anti-angiogenic drugs can serve as strong and independent anti-tumor agents, more than compensating for the decrease in cytotoxic drug exposure by angiogenesis inhibition-induced tumor cell starvation, which may lead to an increase in overall anti-tumor activity. Anti-angiogenics can interact in multiple ways with other anticancer drugs and treatment regimens, making it critical to carefully evaluate and optimize dosing and scheduling in the design of effective drug combinations.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- CECs

circulating endothelial cells

- Dll4

delta-like ligand 4

- EPCs

endothelial progenitor cells

- MTD

maximum tolerated dose

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PLGF

placental growth factor

- RTKI

receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

VEGF receptor

Footnotes

Supported in part by N.I.H. grant CA49238 (to D.J.W.)

Supplementary Table 1 presents the results of 39 preclinical and clinical studies, in which anti-angiogenics are combined with conventional chemotherapies or radiation therapies. The impact of anti-angiogenesis on tumor oxygenation, drug uptake, blood perfusion, vascular permeability, interstitial fluid pressure, and overall therapeutic activity is summarized for each study.

References

- 1.Folkman J. Angiogenesis: an organizing principle for drug discovery? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:273–286. doi: 10.1038/nrd2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baluk P, Hashizume H, McDonald DM. Cellular abnormalities of blood vessels as targets in cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86:353–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christofori G. New signals from the invasive front. Nature. 2006;441:444–450. doi: 10.1038/nature04872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sund M, Hamano Y, Sugimoto H, et al. Function of endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis as endothelium-specific tumor suppressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2934–2939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500180102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almog N, Henke V, Flores L, et al. Prolonged dormancy of human liposarcoma is associated with impaired tumor angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2006;20:947–949. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3946fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black WC, Welch HG. Advances in diagnostic imaging and overestimations of disease prevalence and the benefits of therapy. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1237–1243. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naumov GN, Akslen LA, Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in human tumor dormancy: animal models of the angiogenic switch. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1779–1787. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.16.3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis DW, Herbst R, Abbruzzese JL. Antiangiogenic cancer therapy. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rini BI. Vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy in renal cell carcinoma: current status and future directions. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1098–1106. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: a critical cytokine in tumor angiogenesis and a potential target for diagnosis and therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4368–4380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dafni H, Landsman L, Schechter B, Kohen F, Neeman M. MRI and fluorescence microscopy of the acute vascular response to VEGF165: vasodilation, hyper-permeability and lymphatic uptake, followed by rapid inactivation of the growth factor. NMR in biomedicine. 2002;15:120–131. doi: 10.1002/nbm.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wissmann C, Detmar M. Pathways targeting tumor lymphangiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6865–6868. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamba T, Tam BY, Hashizume H, et al. VEGF-dependent plasticity of fenestrated capillaries in the normal adult microvasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H560–H576. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00133.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kusters B, de Waal RM, Wesseling P, et al. Differential effects of vascular endothelial growth factor A isoforms in a mouse brain metastasis model of human melanoma. Cancer research. 2003;63:5408–5413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tozer GM, Akerman S, Cross NA, et al. Blood vessel maturation and response to vascular-disrupting therapy in single vascular endothelial growth factor-A isoform-producing tumors. Cancer research. 2008;68:2301–2311. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diaz R, Pena C, Silva J, et al. p73 Isoforms affect VEGF, VEGF165b and PEDF expression in human colorectal tumors: VEGF165b downregulation as a marker of poor prognosis. International journal of cancer. 2008;123:1060–1067. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varey AH, Rennel ES, Qiu Y, et al. VEGF 165 b, an antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoform, binds and inhibits bevacizumab treatment in experimental colorectal carcinoma: balance of pro- and antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoforms has implications for therapy. British journal of cancer. 2008;98:1366–1379. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber H-P, Novotny W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manley PW, Bold G, Bruggen J, et al. Advances in the structural biology, design and clinical development of VEGF-R kinase inhibitors for the treatment of angiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1697:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer research. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gollob JA, Wilhelm S, Carter C, Kelley SL. Role of Raf kinase in cancer: therapeutic potential of targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK signal transduction pathway. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:392–406. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markovic A, MacKenzie KL, Lock RB. FLT-3: a new focus in the understanding of acute leukemia. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1168–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sleijfer S, Wiemer E, Verweij J. Drug Insight: gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) - the solid tumor model for cancer-specific treatment. Nat Clin Prac Oncol. 2008;5:102–111. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morikawa S, Baluk P, Kaidoh T, Haskell A, Jain RK, McDonald DM. Abnormalities in pericytes on blood vessels and endothelial sprouts in tumors. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:985–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64920-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benjamin LE, Golijanin D, Itin A, Pode D, Keshet E. Selective ablation of immature blood vessels in established human tumors follows vascular endothelial growth factor withdrawal. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:159–165. doi: 10.1172/JCI5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abramsson A, Lindblom P, Betsholtz C. Endothelial and nonendothelial sources of PDGF-B regulate pericyte recruitment and influence vascular pattern formation in tumors. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1142–1151. doi: 10.1172/JCI18549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sennino B, Falcon BL, McCauley D, et al. Sequential loss of tumor vessel pericytes and endothelial cells after inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor B by selective aptamer AX102. Cancer research. 2007;67:7358–7367. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xian X, Hakansson J, Stahlberg A, et al. Pericytes limit tumor cell metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:642–651. doi: 10.1172/JCI25705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergers G, Song S, Meyer-Morse N, Bergsland E, Hanahan D. Benefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thurston G, Noguera-Troise I, Yancopoulos GD. The Delta paradox: DLL4 blockade leads to more tumour vessels but less tumour growth. Nature reviews. 2007;7:327–331. doi: 10.1038/nrc2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang H, Campbell SC, Bedford DF, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands improve the antitumor efficacy of thrombospondin peptide ABT510. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:541–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pozzi A, Ibanez MR, Gatica AE, et al. Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-alpha-dependent inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17685–17695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amin DN, Hida K, Bielenberg DR, Klagsbrun M. Tumor endothelial cells express epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) but not ErbB3 and are responsive to EGF and to EGFR kinase inhibitors. Cancer research. 2006;66:2173–2180. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Izumi Y, Xu L, di Tomaso E, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Tumour biology: Herceptin acts as an anti-angiogenic cocktail. Nature. 2002;416:279–280. doi: 10.1038/416279b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emlet DR, Brown KA, Kociban DL, et al. Response to trastuzumab, erlotinib, and bevacizumab, alone and in combination, is correlated with the level of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 expression in human breast cancer cell lines. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2007;6:2664–2674. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tonra JR, Deevi DS, Corcoran E, et al. Synergistic antitumor effects of combined epidermal growth factor receptor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2197–2207. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Folkman J. Endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors. APMIS. 2004;112:496–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm11207-0809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Reilly MS, Holmgren L, Shing Y, et al. Angiostatin: a novel angiogenesis inhibitor that mediates the suppression of metastases by a Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell. 1994;79:315–328. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Folkman J. Antiangiogenesis in cancer therapy--endostatin and its mechanisms of action. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:594–607. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdollahi A, Hahnfeldt P, Maercker C, et al. Endostatin's antiangiogenic signaling network. Mol Cell. 2004;13:649–663. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Q, Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. Mortality associated with Down's syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: a population-based study. Lancet. 2002;359:1019–1025. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawler J, Detmar M. Tumor progression: the effects of thrombospondin-1 and -2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams JC, Lawler J. The thrombospondins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bocci G, Francia G, Man S, Lawler J, Kerbel RS. Thrombospondin 1, a mediator of the antiangiogenic effects of low-dose metronomic chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12917–12922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135406100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Esemuede N, Lee T, Pierre-Paul D, Sumpio BE, Gahtan V. The role of thrombospondin- 1 in human disease. J Surg Res. 2004;122:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Volpert OV, Zaichuk T, Zhou W, et al. Inducer-stimulated Fas targets activated endothelium for destruction by anti-angiogenic thrombospondin-1 and pigment epithelium-derived factor. Nat Med. 2002;8:349–357. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westphal JR. Technology evaluation: ABT-510, Abbott. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2004;6:451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tien YW, Jeng YM, Hu RH, Chang KJ, Hsu SM, Lee PH. Intravasation-related metastatic factors in colorectal cancer. Tumor Biol. 2004;25:48–55. doi: 10.1159/000077723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nyberg P, Heikkila P, Sorsa T, et al. Endostatin inhibits human tongue carcinoma cell invasion and intravasation and blocks the activation of matrix metalloprotease-2, -9, and -13. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22404–22411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stoletov K, Montel V, Lester RD, Gonias SL, Klemke R. High-resolution imaging of the dynamic tumor cell vascular interface in transparent zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17406–17411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703446104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the 'seed and soil' hypothesis revisited. Nature reviews. 2003;3:453–458. doi: 10.1038/nrc1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaplan RN, Rafii S, Lyden D. Preparing the "soil": the premetastatic niche. Cancer research. 2006;66:11089–11093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qian CN, Berghuis B, Tsarfaty G, et al. Preparing the "soil": the primary tumor induces vasculature reorganization in the sentinel lymph node before the arrival of metastatic cancer cells. Cancer research. 2006;66:10365–10376. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holmgren L, O'Reilly MS, Folkman J. Dormancy of micrometastases: balanced proliferation and apoptosis in the presence of angiogenesis suppression. Nat Med. 1995;1:149–153. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gao D, Nolan DJ, Mellick AS, Bambino K, McDonnell K, Mittal V. Endothelial progenitor cells control the angiogenic switch in mouse lung metastasis. Science. 2008;319:195–198. doi: 10.1126/science.1150224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gupta GP, Nguyen DX, Chiang AC, et al. Mediators of vascular remodelling co-opted for sequential steps in lung metastasis. Nature. 2007;446:765–770. doi: 10.1038/nature05760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liao D, Corle C, Seagroves TN, Johnson RS. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is a key regulator of metastasis in a transgenic model of cancer initiation and progression. Cancer research. 2007;67:563–572. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cacheux W, Boisserie T, Staudacher L, et al. Reversible tumor growth acceleration following bevacizumab interruption in metastatic colorectal cancer patients scheduled for surgery. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1659–1661. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Norden AD, Young GS, Setayesh K, et al. Bevacizumab for recurrent malignant gliomas: Efficacy, toxicity, and patterns of recurrence. Neurology. 2008;70:779–787. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304121.57857.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jain RK. Delivery of molecular and cellular medicine to solid tumors. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:149–168. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Willett CG, Boucher Y, di Tomaso E, et al. Direct evidence that the VEGF-specific antibody bevacizumab has antivascular effects in human rectal cancer. Nat Med. 2004;10:145–147. doi: 10.1038/nm988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huber PE, Bischof M, Jenne J, et al. Trimodal cancer treatment: beneficial effects of combined antiangiogenesis, radiation, and chemotherapy. Cancer research. 2005;65:3643–3655. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tong RT, Boucher Y, Kozin SV, Winkler F, Hicklin DJ, Jain RK. Vascular normalization by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 blockade induces a pressure gradient across the vasculature and improves drug penetration in tumors. Cancer research. 2004;64:3731–3736. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Batchelor TT, Sorensen AG, di Tomaso E, et al. AZD2171, a pan-VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, normalizes tumor vasculature and alleviates edema in glioblastoma patients. Cancer cell. 2007;11:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dickson PV, Hamner JB, Sims TL, et al. Bevacizumab-induced transient remodeling of the vasculature in neuroblastoma xenografts results in improved delivery and efficacy of systemically administered chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3942–3950. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Segers J, Fazio VD, Ansiaux R, et al. Potentiation of cyclophosphamide chemotherapy using the anti-angiogenic drug thalidomide: Importance of optimal scheduling to exploit the 'normalization' window of the tumor vasculature. Cancer Lett. 2006;244:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wildiers H, Guetens G, De Boeck G, et al. Effect of antivascular endothelial growth factor treatment on the intratumoral uptake of CPT-11. British journal of cancer. 2003;88:1979–1986. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou Q, Guo P, Gallo JM. Impact of angiogenesis inhibition by sunitinib on tumor distribution of temozolomide. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1540–1549. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Winkler F, Kozin SV, Tong RT, et al. Kinetics of vascular normalization by VEGFR2 blockade governs brain tumor response to radiation: role of oxygenation, angiopoietin-1, and matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer cell. 2004;6:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kabbinavar F, Hurwitz HI, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Phase II, randomized trial comparing bevacizumab plus fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) with FU/LV alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:60–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weissleder R. Scaling down imaging: molecular mapping of cancer in mice. Nature reviews. 2002;2:11–18. doi: 10.1038/nrc701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Franco M, Man S, Chen L, et al. Targeted anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 therapy leads to short-term and long-term impairment of vascular function and increase in tumor hypoxia. Cancer research. 2006;66:3639–3648. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dings RP, Loren M, Heun H, et al. Scheduling of radiation with angiogenesis inhibitors anginex and avastin improves therapeutic outcome via vessel normalization. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3395–3402. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koehne C, Bajetta E, Lin E, et al. Results of an interim analysis of a multinational randomized, double-blind, phase III study in patients (pts) with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) receiving FOLFOX4 and PTK787/ZK 222584 (PTK/ZK) or placebo (CONFIRM 2) J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3508. [Google Scholar]

- 86.BayerHealthCare. News release by Bayer HealthCare. 2008. Feb 18, Bayer and Onyx provide update on phase III trial of Nexavar® in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Inai T, Mancuso M, Hashizume H, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling in cancer causes loss of endothelial fenestrations, regression of tumor vessels, and appearance of basement membrane ghosts. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:35–52. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63273-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nakamura K, Taguchi E, Miura T, et al. KRN951, a highly potent inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, has antitumor activities and affects functional vascular properties. Cancer research. 2006;66:9134–9142. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nakahara T, Norberg SM, Shalinsky DR, Hu-Lowe DD, McDonald DM. Effect of inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling on distribution of extravasated antibodies in tumors. Cancer research. 2006;66:1434–1445. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]