Abstract

For a long time it has been believed that lignification has an important role in host defense against pathogen invasion. Recently, by using an RNAi gene-silencing assay we showed that monolignol biosynthesis plays a critical role in cell wall apposition (CWA)-mediated defense against powdery mildew fungus penetration into diploid wheat. Silencing monolignol genes led to super-susceptibility of wheat leaf tissues to an appropriate pathogen, Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici (Bgt), and compromised penetration resistance to a non-appropriate pathogen, B. graminis f. sp. hordei. Autofluorescence of CWA regions was reduced significantly at the fungal penetration sites in silenced cells. Our work indicates an important role for monolignol biosynthetic genes in effective CWA formation against pathogen penetration. In this addendum, we show that silencing of monolignol genes also compromised penetration resistant to Bgt in a resistant wheat line. In addition, we discuss possible insights into how lignin biosynthesis contributes to host defense.

Key words: monolignol, papilla autofluorescence, methylated lignin, defense lignin, cereal

Lignification is a mechanism for disease resistant in plants.1,2 During defense responses, lignin or lignin-like phenolic compound accumulation was shown to occur in a variety of plant-microbe interactions.1,2 Plants assemble CWAs, also called papillae, at the sites of attempted penetration of biotrophic fungi such as powdery mildew.2,3 Lignin, a major component of cell walls of vascular plants, was shown to accumulate in CWAs and surrounding halo areas1–3 and is, thus, considered a first line defense against successful penetration of invasive pathogens. Lignification renders the cell wall more resistant to mechanical pressure applied during penetration by fungal appressoria as well as more water resistant and thus less accessible to cell wall-degrading enzymes.1–3

Lignification is essential for the structural integrity of plant cell walls and is crucial for plant development4 but the monomeric composition of lignin can vary depending on the developmental process: thus, defense lignin accumulated by an elicitor treatment was shown to be significantly different from lignin in vascular tissues,5 suggesting that lignin biosynthesis is differentially regulated.

Despite the importance of lignin accumulation at CWA sites, genetic evidence for the role of monolignols in cell wall-associated defense is rare either because of the indispensability of lignin for plant form or as a result of the redundancy among enzymes involved in the monolignol pathway.6 Global gene expression of defense metabolites is a primary response during plant-microbe interaction. In our study, expression of all monolignol biosynthetic genes was induced during Bgt infection in both susceptible and resistant (CWA-mediated) wheat lines.7 Transcripts of all monolignol genes were accumulated at a certain time point, 24 h post inoculation, in the resistant line, which coincided with attempted penetration of fungal appressorial germ tubes.7 Because of these observations, we sought to clarify whether silencing these genes would allow successful penetration by Bgt into the resistant line.

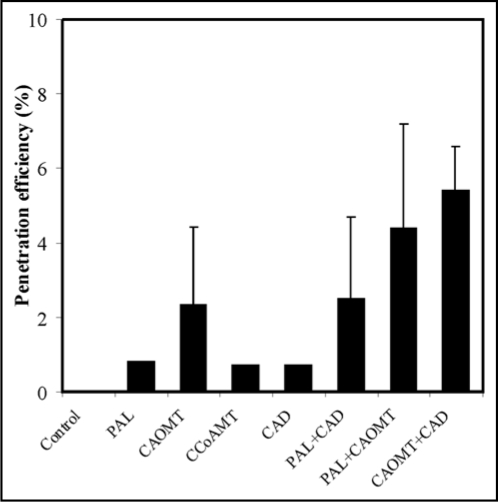

Our results demonstrate that silencing monolignol genes not only made wheat leaf tissues super-susceptible to Bgt infection7 but also compromised penetration resistance to Bgt in the resistant wheat line, albeit at a very low efficiency (Fig. 1). Individual silencing of TmPAL, TmCAOMT, TmCCoAMT and TmCAD allowed penetration; co-silencing increased its efficiency. The maximum penetration efficiency (5.4%) was obtained with TmCAOMT + TmCAD. We also observed that autofluorescence of CWA in silenced cells was reduced compared to those not silenced (data not shown). The low penetration efficiency suggested that additional isoforms of monolignol genes are involved in resistance. It may also be that papilla-mediated resistance in this line is mechanistically distinct from the susceptible line; defense compounds in addition to monolignols or their derivatives may be required.

Figure 1.

RNAi-mediated monolignol gene silencing compromises penetration resistance to Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici infection in a wheat resistant line. Penetration efficiency of Bgt in the line was evaluated by at least three independent experiments in which, as a minimum, 100 GUS-stained cells were measured. Bars represent standard errors. After 4 h of bombardment leaves were inoculated with a high density of Bgt conidia and successful entry into epidermis cells was evaluated using microscopy.

Monolignol gene silencing reduced autofluorescence intensity at CWA sites;7 co-silencing gave rise to a higher penetration efficiency and a lower autofluorescence at the CWA than did individual gene silencing in both susceptible and resistant lines. It may be that co-silencing reduces lignin flux to a greater extent than does individual silencing. Also it can not be excluded that our gene silencing might have decreased the soluble phenolic acids, monolignols or their derivatives in CWAs, which, in turn, might have affected the efficiency of the papilla to prevent fungal invasion. Soluble phenolics, which can be incorporated into lignin polymer,8 may be involved in penetration defense.9,10

Previously it was shown that suppression of F5H or CAOMT, which reside on a branch pathway converting guaiacyl (G) to syringyl (S) units, greatly reduced the S/G ratio but has little effect on total lignin content.11,12 In our study, silencing TmCAOMT was the most efficient way among all individual genes to enhance fungal penetration7 indicating that changes in S/G ratio are also an important factor for penetration. Silencing TmCAOMT was also the most effective way to allow penetration into the resistant line, which reinforced our previous hypotheses that methylated monolignol plays an important role in effective CWA formation7 and methyl unit generation is critical to for the mitigation of multiple stresses.13 CAOMT catalyzes the synthesis of synapyl alcohol, the precursor of S lignin units4,11 and CCoAMT is shown to be necessary for the formation of G rather than S lignin units.11 Our data show that silencing TmCAOMT increases penetration efficiency of Bgt compared to TmCCoAMT in resistant lines, which also supports our previous hypothesis that S lignin plays a pivotal role in CWA-mediated defense.7

In conclusion, while our study reveals the role of monolignol biosynthesis in host defense against powdery mildew infection in a monocot plant, it is not known if this pathway has a similar role in dicot. Arabidopsis mutants lacking all individual genes of monolignol biosynthesis are now available and could be used to clarify this point. Recently, it has been reported that the C3H defective mutant, ref8 Arabidopsis, which displays reduced lignin content (20–40%), altered soluble phenolics and reduced epidermal fluorescence, shows susceptibility to fungal attack.14 It is also worthy of note that, although our data indicate the importance of monolignol biosynthesis for effective CWA formation at the attempted penetration site of a fungus, how lignin polymerizes at the CWA region is not known. Since synapyl alcohol is the precursor of S lignin and our data suggest S lignin is linked with CWA-mediated defense; focusing on synapyl alcohol-specific peroxidases would be a potential approach to elucidate the regulation of lignin in defense response.

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/7688

References

- 1.Vance CP, Kirk TK, Sherwood RT. Lignification as a mechanism of disease resistance. Ann Review Phytopath. 1980;18:259–288. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholson RL, Hammerschmidt R. Phenolic compounds and their role in disease resistance. Ann Rev Phytopath. 1992;30:369–389. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeyen RJ, Carver TLW, Lyngkjaer MF. Epidermal cell papillae. In: Belanger RR, Bushnell WR, editors. The powdery mildew: a comprehensive treatise. MN, USA: APS Press; 2002. pp. 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boerjan W, Ralph J, Baucher M. Lignin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54:519–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange BM, Lapierre C, Sandermann H., Jr Elicitor induced spruce stress lignin. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1277–1287. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hückelhoven R. Cell wall-associated mechanisms of disease resistance and susceptibility. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2007;45:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.45.062806.094325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhuiyan NH, Selvaraj G, Wei Y, King J. Gene expression profiling and silencing reveal that monolignol biosynthesis plays a critical role in penetration defense in wheat against powdery mildew invasion. J Ex Bot. 2008 doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ralph J, Lundquist K, Brunow G, Lu F, Kim H, Schatz PF, Marita JM, Hatfield RD, Ralph SA, Christensen JH, et al. Lignins: natural polymers from oxidative coupling of 4-hydrxophenylpropanoids. Phytochem Rev. 2004;3:29–60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Röpenack E, Parr A, Schulze-Lefert P. Structural analysis and dynamics of soluble and cell wall-bound phenolics in a broad-spectrum resistance to the powdery mildew fungus in barley. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9013–9022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLusky SR, Bennett MH, Beale MH, Lewis MJ, Gaskin P, Mansfield JW. Cell wall alterations and localized accumulation of feruloyl-3′-methaxytyramine in onion epidermis at sites of attempted penetration by Botrytis allii are associated with actin polarization, peroxidases activity and suppression of flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant J. 1999;17:523–534. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen F, Reddy MSS, Temple S, Jackson L, Shadle G, Dixon RA. Multi-site genetic modulation of monolignol biosynthesis suggests new routes for formation of syringyl lignin and wall-bound ferulic acid in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Plant J. 2006;48:113–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Weng JK, Chapple C. Improvement of biomass through lignin modification. Plant J. 2008;54:569–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhuiyan NH, Liu W, Liu G, Selvaraj G, Wei Y, King J. Transcriptional regulation of genes involved in the pathways of biosynthesis and supply of methyl units in response to powdery mildew attack and abiotic stresses in wheat. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;64:305–318. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franke R, Hemm MR, Denault JW, Ruegger MO, Humphreys JM, Chapple C. Changes in secondary metabolism and deposition of an unusual lignin in the ref8 mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;30:47–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]