Abstract

The dynamic effects of low-frequency biasing on spontaneous otoacoustic emissions (SOAEs) were studied in human subjects under various signal conditions. Results showed a combined suppression and modulation of the SOAE amplitudes at high bias tone levels. Ear-canal acoustic spectra demonstrated a reduction in SOAE amplitude and growths of sidebands while increasing the bias tone level. These effects varied depending on the relative strength of the bias tone to a particular SOAE. The SOAE magnitudes were suppressed when the cochlear partition was biased in both directions. This quasi-static modulation pattern showed a shape consistent with the first derivative of a sigmoid-shaped nonlinear function. In the time domain, the SOAE amplitudes were modulated with the instantaneous phase of the bias tone. For each biasing cycle, the SOAE envelope showed two peaks each corresponded to a zero-crossing of the bias tone. The temporal modulation patterns varied systematically with the level and frequency of the bias tone. These dynamic behaviors of the SOAEs are consistent with the shifting of the operating point along the nonlinear transducer function of the cochlea. The results suggest that the nonlinearity in cochlear hair cell transduction may be involved in the generation of SOAEs.

I. INTRODUCTION

An intriguing feature of our inner ear is that it can produce sounds even without acoustic stimulation. These self-generated tonal noises from the inner ear, called spontaneous otoacoustic emissions (SOAEs), have long been thought to reflect the active feedback from the outer hair cell (OHC) activities (Gold, 1948). It is speculated that these cells are on the verge of self-sustained oscillation to maximize their sensitivity. This indicates that at the auditory threshold the cochlear partition is under-damped and the cellular structures undergo autonomous resonance. Due to sporadically irregular arrangements of these cells, e.g., an extra row or a few missing ones (Lonsbury-Martin et al., 1988), or perhaps a reduced efferent control from the upper auditory system (Braun, 2000), these oscillations from some particular locations in the cochlea become large enough and eventually escape the boundary of the inner ear, so that they can be recordable in the ear canal. When these oscillatory waves propagate out of the inner ear, part of the mechanical energy may be reflected at the stapes footplate in the middle ear back to their generating sites in the inner ear thus forming a standing wave that could be amplified after multiple roundtrips (Shera, 2003). Despite the complex mechanisms of SOAE generation, the presence of low-level SOAEs is naturally related to the normal function of cochlear OHCs.

Since the discovery of otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) in humans (Kemp, 1978), SOAEs are found in many species, e.g., frogs (Palmer and Wilson, 1982), monkeys (Martin et al., 1985), guinea pigs (Ohyama et al., 1991), and birds (Manley and Taschenberger, 1993). The drastic differences in the anatomical structures of inner ears between these species indicate that the modes of sound propagation in these ears are different. However, the functions of these different ears are the same, i.e., transferring mechanical energy into neural signals. A common element in these inner ears is the hair cell where acoustical vibrations are converted into electrical voltages, or mechano-electrical transduction. It has been found that the stereocilia of the reptile hair cells are capable of spontaneous movement (Martin et al., 2003). Additional evidences, such as abolishment of SOAEs in humans (McFadden and Plattsmier, 1984) and lizards (Stewart and Hudspeth, 2000) by aspirin known for altering hair cell transduction, also point to a common process involved in the generation of SOAEs in different species. It seems likely that there may be a universal mechanism, i.e., hair cell transduction, responsible for the production of SOAEs. Studying the characteristics of SOAEs can provide a window for looking into normal auditory hair cell functions and their relation to the “active process” in the inner ear.

It is well-known that the cochlear transduction is highly nonlinear as it is widely observed that suppression and distortion are typical when two tones with different frequencies (f1, f2, f1<f2) are presented to the ear. Thus, using an external tone to influence the internally generated tonal sounds becomes a rather interesting approach to study the features of SOAEs (Zurek, 1981; Schloth and Zwicker, 1983; Rabinowitz and Widin, 1984). It has been shown (Frick and Matthies, 1988, Norrix and Glattke, 1996) that an external tone presented near the SOAE frequency can suppress the SOAE and generate distortion products (DPs). The effects of very low frequency external tones on SOAEs have not been studied, but it is known that these tones can produce suppression of other types of OAEs, such as transient evoked OAEs (Zwicker, 1981) and distortion products (Frank and Kössl, 1996; Scholz et al., 1999; Bian et al., 2002). Systematic investigations with a low-frequency tone revealed that it can produce an amplitude modulation (AM) of the distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) due to biasing of the cochlear partition (Bian, 2004 and 2006; Bian et al., 2004). These manipulations of cochlear mechanics are consistent with the consequences of modulating a saturating nonlinear system which could be attributed to the OHC transduction. Quantifying the cochlear transducer function (FTr) using DPOAEs can provide a noninvasive means for acquiring information of cochlear mechanics which is critical for possible clinical applications (Bian and Scherrer, 2007). Since the SOAEs may reflect the inner ear mechanical activities below or at hearing threshold where the cochlear transducer gain is highest, it is hypothesized that biasing the cochlear partition could reduce the gain and thus modulate the SOAE magnitudes. If this was true, the relation between the AM of SOAE and the bias tone could allow a cochlear FTr to be derived. Therefore, to test the hypothesis, experiments were carried out on human subjects to study the effects of low-frequency biasing on SOAEs. Here, the dynamical effects on the SOAE amplitudes are reported.

II. METHODS

A. Experimental procedures

A total of 57 healthy students attending at the Arizona State University (ASU) were screened for possessing large synchronized SOAEs (ILO92, Otodynamics) to participate in the study. The subject selection criteria were set as the following: 1) at least one SOAE in one ear was 20 dB above noise floor, and 2) the spacing between two adjacent SOAEs was greater than 300 Hz to avoid possible interference. All the participating subjects were verified to have normal hearing thresholds from 250 to 8000 Hz. Their middle- and outer-ear functions were normal based on a middle ear impedance test and an otoscopy. All these screening and pre-experimental tests were performed in the audiology clinic of the Department of Speech and Hearing Science. The experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board on human research subjects at the ASU. Data were collected from eleven ears from a total of 10 qualified subjects. The ear-canal acoustical signal was measured with a calibrated probe microphone (Etymotic Research, ER-10B+) which was inserted into the ear canal with an immittance probe tip (ER-34). One port on the ER-10B+ system was coupled with a silicon front tube (ER1-21) and the other was plugged. The bias tone was produced from an 8.5 mm insertion earphone (HA-FX55, JVC) which was connected to the ER-10B via the front tube. The ear canal acoustic signal was recorded while presenting the bias tone at frequencies ranging from 25 to 100 Hz. At each bias tone frequency, the peak level of the bias tone was attenuated automatically from about 2 ~ 4 Pa to 0 in 41 steps. The whole recording session was repeated after a 20 minute break. The purpose of the second trial was to check for variation in the SOAEs over time and the repeatability of the effects of the low-frequency modulation.

B. Signal Processing and data acquisition

The ear-canal acoustic signal was recorded using a software developed in LabVIEW (v.8, National Instruments, NI) similar to previously described (Bian and Scherrer, 2007). Briefly, a 1s long bias tone with 10ms onset/offset ramps and a 0.1s flat tail (Fig. 1B) was output to a channel on a 24-bit dynamic signal acquisition (DAQ) and generation cards (PXI-4461, NI). The initial bias tone level (Lbias) was set by observing a complete suppression of the largest SOAE. The Lbias was attenuated automatically from the initial level to 0 Pa in 41 steps with smaller steps at higher intensities. For most subjects, the bias tone frequency (fbias) was set at 25, 32, 50, 75, and 100 Hz in random order to modulate the SOAEs. Data were collected via an input channel on the same DAQ card. Both the input and output channels were synchronized with an onboard clock and triggered with a digital pulse. For each biasing step, the ear-canal acoustic signal was amplified 20 dB by the build-in preamplifier on the ER-10B+, averaged 8–12 times depending on the size of the SOAE, and digitized at 204.8 kHz for off-line analysis in Matlab (Math Works).

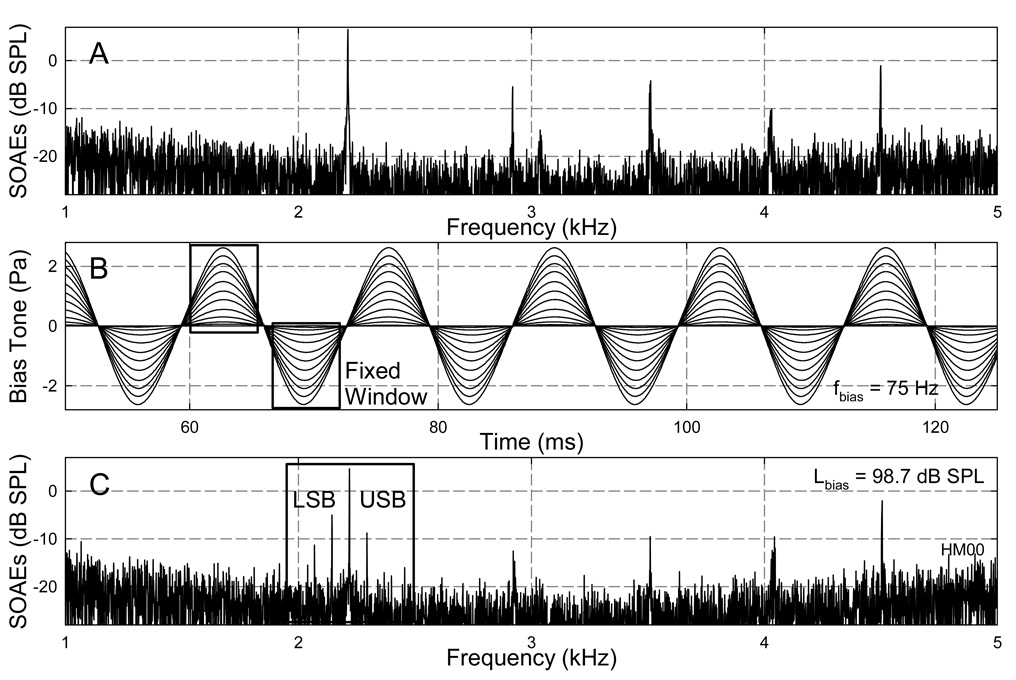

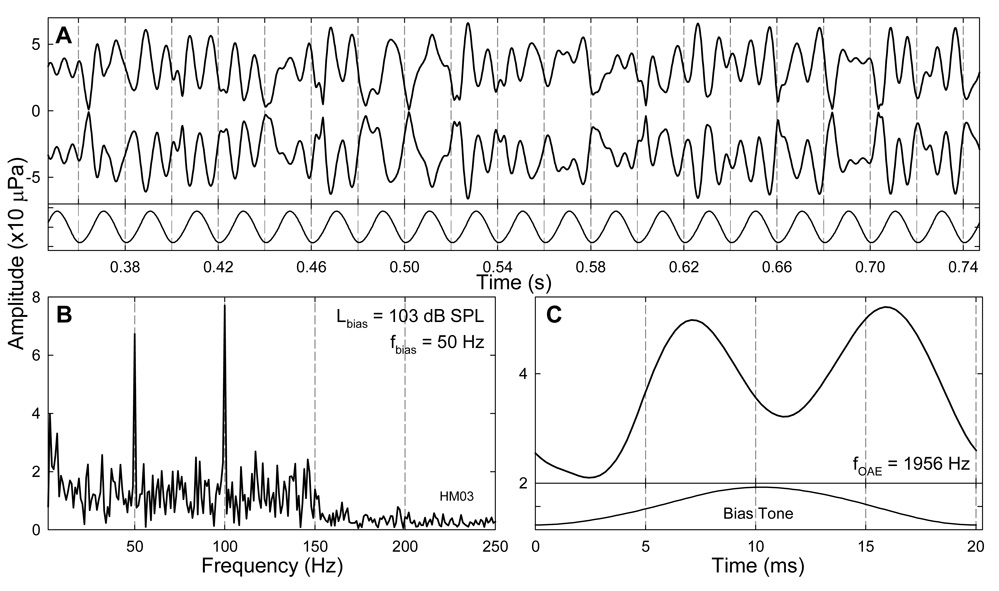

Fig. 1. Ear-canal acoustic spectra and bias tones.

A: Spectrum of the ear canal acoustics without bias tone showing five major SOAE components. B: Samples of a 75-Hz bias tone with series of amplitudes. Rectangles indicate the fixed FFT windows centered at the peaks and troughs of the bias tones to obtain SOAE amplitudes for the quasi-static modulation pattern. C: Spectrum of an ear-canal acoustic signal with the presence of a bias tone showing modulation sidebands. A rectangular window centered at the CDT frequency covering multiple sideband components around the CDT was used obtain a temporal SOAE envelope via IFFT. USB: upper sideband; LSB: lower sideband.

C. Data analysis

The spectral feature of the SOAEs was extracted from a fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the high-pass filtered (at 400 Hz) ear-canal acoustic signal (Fig. 1A and 1C). Since the low-frequency modulation of SOAEs is reflected by the presence of lower and upper sidebands (LSBs and USBs) around the emission components, the amplitudes of two LSBs and two USBs were measured for each OAE component. System distortions could be ruled out, because no sidebands could be observed in a 2-cc coupler when a 2 kHz probe tone was presented below 50 dB SPL with the presence of a bias tone at 106 dB SPL. The quasi-static modulation patterns (Bian and Chertoff, 2006) of SOAEs were derived from short-time FFTs with windows fixed at the peaks and troughs of the bias tone (Fig. 1B) assuming static cochlear responses at these moments. The length of the FFT window was so determined that it was shorter than 1/2 biasing cycle and the SOAE frequency was centered in a frequency bin. The SOAE amplitudes for two adjacent bias tone peak or trough sequences were paired to form the positive and negative parts of the quasi-static modulation pattern. These patterns then were averaged across 22 to 88 pairs of peaks and troughs for different biasing frequencies. The dynamic or temporal features of the SOAEs were obtained from a spectral windowing method (Fig. 1C). For a specific SOAE, the complex spectrum of the ear canal signal was rectangular-windowed at the positive SOAE frequency including 3~4 sidebands on each side and inverse fast Fourier transformed (IFFT) to recover the amplitude envelope of the SOAE. The instantaneous SOAE amplitude was examined with the bias tone waveform obtained from low-pass filtering at 400 Hz.

III. RESULTS

A. General characteristics of SOAEs

From the 114 ears of 57 subjects who were screened for SOAEs, 11 ears from 10 subjects were qualified for participating in the experiments. As can be noted from Table I, there were six females and four males with ages ranging from 18 to 34 (mean age: 24). Most of them, except two, had SOAEs in both ears. Except subject HM25, low-frequency modulation of SOAEs was measured from only one side. The data were collected from the right ears of seven subjects and the left ears of four subjects. Since the characteristics of SOAEs were highly dependent on each individual ear, the features of SOAEs are described on a case by case basis. Among the 11 ears (Table I), the number of SOAEs in each ear ranged from 1 to 5 components with an average of 3 SOAEs/ear. Averaged across ears, the absolute differences between the SOAE amplitudes obtained at the two trials were less than 1.75 dB. If consider the change as an increase or a decrease for each component, the average change in SOAE amplitudes was a negligible decrease (−0.02 dB). Therefore, the data obtained at the two trials were combined in reporting. There was also a frequency shift during the low-frequency biasing which will be reported in a separate paper. In the present report, only the effects on the amplitudes of the SOAEs are considered.

Table I.

Characteristics of qualified subjects.

| Subject | Gender | Sides | Side(s) used | Age | Num of SOAEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HM00 | F | Both | R | 27 | 5 |

| HM03 | F | Both | R | 22 | 5 |

| HM16 | F | Single | R | 23 | 1 |

| HM17 | F | Both | R | 24 | 2 |

| HM25 | M | Both | L, R | 34 | 3, 5 |

| HM36 | F | Both | L | 18 | 4 |

| HM46 | F | Both | L | 19 | 2 |

| HM47 | M | Single | R | 26 | 1 |

| HM48 | M | Both | L | 19 | 2 |

| HM54 | M | Both | R | 28 | 5 |

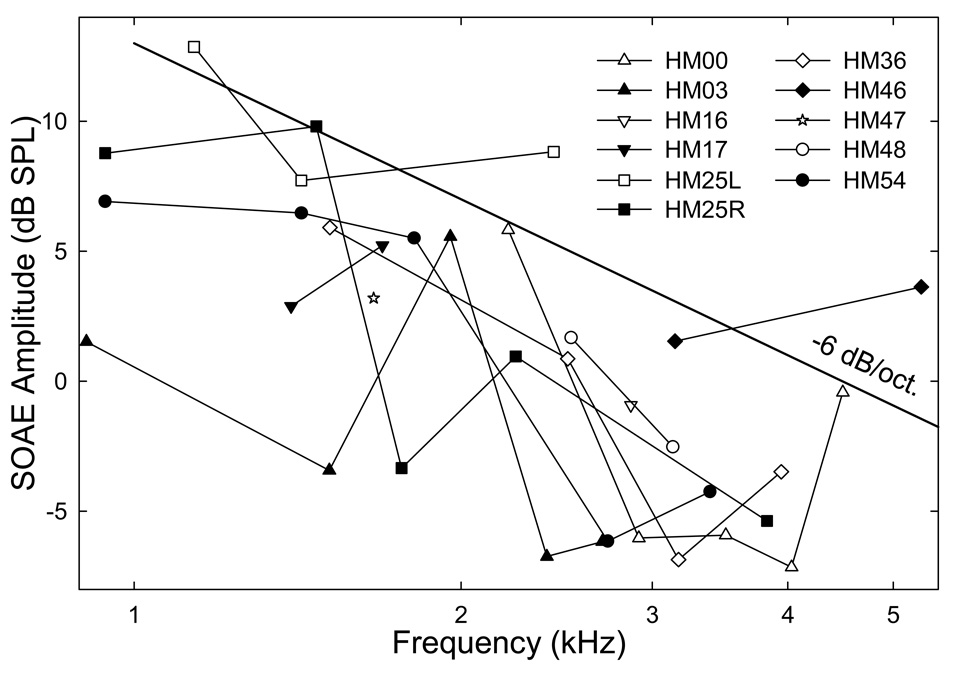

The amplitude and frequency distributions of these SOAEs averaged across the two trials for each ear are illustrated as a form of “SOAE-gram” (Fig. 2). As can be seen, the amplitudes of SOAEs ranged from −7 to 13 dB SPL across subjects. Within a single subject, the variation of SOAEs amplitude was smaller, and the amplitude difference between two adjacent SOAEs was less than 15 dB. The amplitude of SOAEs averaged across all components was greater than −3 dB SPL. The frequency range of the SOAEs covered from about 900 to 5500 Hz. For subjects with multiple SOAE components, the averaged frequency spacing was about 764 Hz with a minimal spacing of as small as 290 Hz in the left ear of subject HM25. From Fig. 2, there is a trend can be observed, i.e., the SOAE amplitudes were higher in the low-frequencies and lower in the higher frequencies showing a form of a low-pass filter. The slope of the low-pass filter was roughly −6 dB/octave.

Fig. 2. SOAE-grams.

The amplitudes and frequencies of the SOAEs for each subject are displayed with a line marked by symbols. Data represent an average of the two trials. A trend can be observed from the data: SOAE amplitudes are inversely related to their frequencies. The dark line indicates the slope of the trend: −6 dB/octive.

B. Spectral effects

1. Suppression of SOAE and generation of sidebands

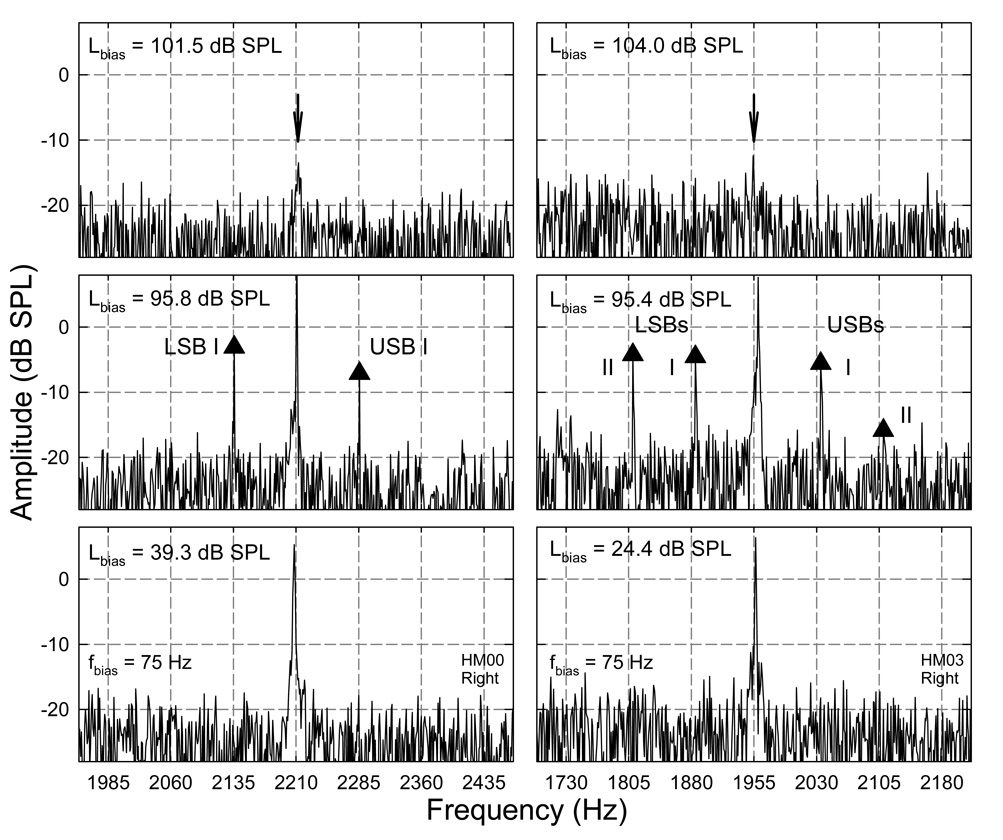

In the spectral domain, the effects of low-frequency biasing were expressed as reductions in SOAE amplitudes and generations of sidebands (Fig. 3). When the Lbias was high enough, the SOAE could be completely suppressed (top panels). While the Lbias was decreased, the SOAE amplitude started to recover and multiple sidebands appeared on both sides. The number and sizes of the sidebands varied depending on the signal conditions, such as, the Lbias, the fbias, and the original SOAE level. There could be single or double sidebands on each side of the SOAE component (Fig. 3 middle row) indicating different temporal modulation characteristics. The sidebands presented at the spectral positions of integer multiples of the fbias from the SOAE frequency. In most of the observations, the sidebands that had a spectral spacing of fbias from the SOAE component (sidebands I) were the largest in magnitude. The sidebands 2fbias from the SOAE in either LSB or USB were smaller than sidebands I, but larger than other more distant sidebands. Thus, the analysis was focused on these two sidebands. As the Lbias further decreased, the SOAE amplitudes fully recovered, and sidebands also diminished (bottom).

Fig. 3. Spectral representation of low-frequency biasing on SOAEs: suppression and modulation.

Each column corresponds to a subject. Panels at the bottom show that there is no effect on the SOAE when the Lbias is very low. Middle row indicate the presence of AM of the SOAEs at moderately high Lbias indicated by the generation of spectral sidebands around the SOAE components. Sidebands are labeled as I and II based on their frequency spacing with the SOAE. Note: the difference in the number of sidebands between the two subjects. Top row: suppression of the SOAEs when the Lbias is very high. Arrows point to the suppressed SOAEs.

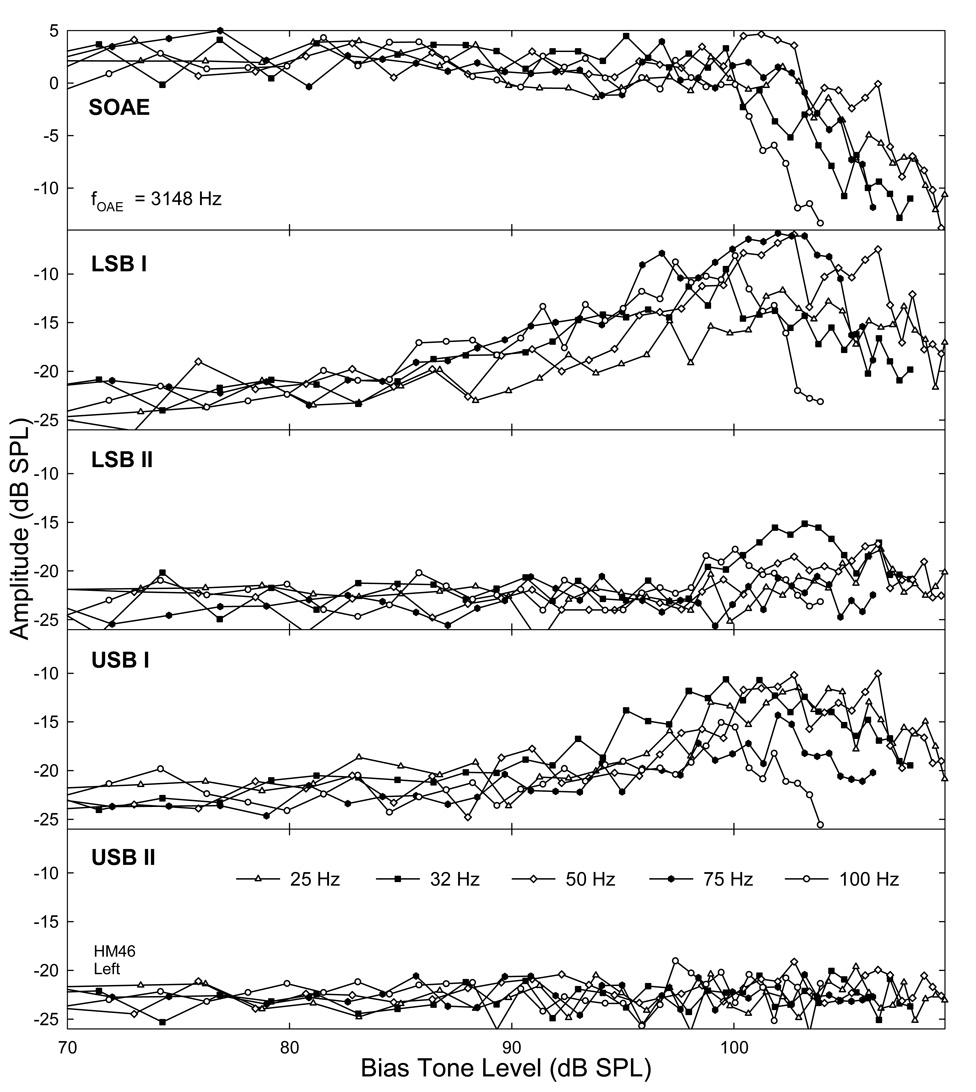

These opposite changes in the amplitudes of SOAE and its sidebands as functions of increasing Lbias were better observed in Fig. 4. As the example showed, the SOAE amplitude remained relatively stable with less than 5 dB fluctuations when the bias tone was below 100 dB SPL. Above this Lbias, the SOAE amplitude became suppressed (top). The rate of decline in the SOAE depended on the fbias, i.e., faster for higher biasing frequencies than lower frequencies. For example, the SOAE amplitude reduced at a 3 dB/dB rate at 100 Hz fbias compared to 1 dB/dB at 25 Hz. The growths of sidebands started at much lower biasing levels (lower four panels). The LSB I began to increase at about 80 dB SPL, and reached a peak at 102 dB SPL Lbias while USB I peaked at 98 dB SPL. The peak amplitudes of sidebands I (usually −5 to −10 dB SPL) were higher than those of sidebands II (< −10 dB SPL), and the LSBs were larger than their counterparts in USB. For about a 10–15 dB range of Lbias above 80 dB SPL, the sidebands increased at rates slower than 1 dB/dB without suppressing the SOAE noticeably. After the sidebands reached their peaks, it was evident that the SOAE often reduced more than 3 to 5 dB. When the SOAE was drastically suppressed and diminished, the sidebands showed a roll-over and eventually fell back to the noise floor. The biasing levels corresponding to the onsets and the peaks of the sidebands were lower for higher biasing frequencies, suggesting that these bias tones were more effective in suppressing and modulating the emissions.

Fig. 4. Opposite biasing effects on the magnitudes of an SOAE and its sidebands.

Top panel: suppression of SOAEs as Lbias exceeds about 100 dB SPL. Each line represents an average across the two trials. Lower four panels show the effect of Lbias on the SOAE sidebands. The sideband amplitudes increase with Lbias and reach their maximal value above 100 dB SPL biasing level where the SOAEs are significantly suppressed. Note the differences between various bias tone frequencies.

2. Effects of fbias and SOAE frequencies

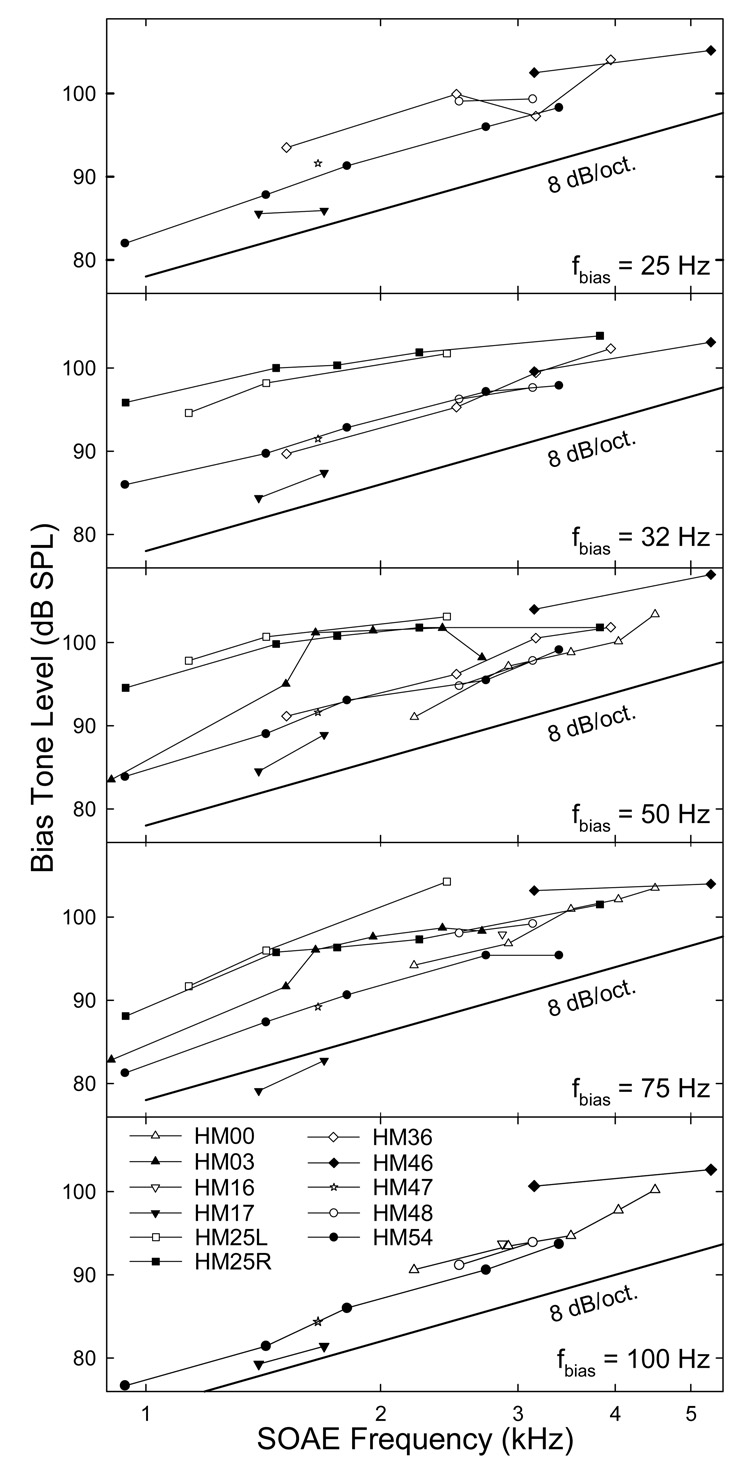

Since the SOAEs were larger and less variable compared to their sidebands, the effects of the fbias were examined by measuring the suppression of the SOAEs. Because the peaks of the sidebands corresponded to a 3- to 5-dB reduction in the SOAE amplitude, a 5-dB suppression of SOAE was used as a criterion to evaluate these frequency effects. For each SOAE, the Lbias required to produce a 5-dB reduction in the SOAE magnitude was obtained from the SOAE suppression curve like those in the top panel of Fig. 4. For each subject, the values derived from the two trials were averaged to form a 5-dB iso-suppression contour representing the effectiveness of the bias tone in suppressing and modulating the SOAEs at different frequencies (Fig. 5). A general trend could be observed that it required higher sound pressures to induce the same extent suppression of SOAEs at higher frequencies. This trend held for all biasing frequencies regardless the sizes of SOAEs. The slope of the iso-suppression curve seemed shallower for larger SOAEs. However, for most subjects with modest SOAE magnitudes the iso-suppression curves approached a slope of about 8 dB/octave with increasing SOAE frequency. If observing each subject closely, it could be found that the SOAE suppression curves shifted downwards as the fbias increased. This indicated that lower frequency bias tones were less efficient in suppressing the SOAEs, thus higher biasing levels were used.

Fig. 5. 5-dB iso-suppression curves.

Each data point represents the Lbias required to produce a 5-dB reduction in the SOAE amplitude. The curves imply the efficiencies of the bias tone on SOAEs at different frequencies. For a bias tone with fixed frequency, it is more effective in suppressing SOAEs with lower frequencies. The change in the ability of the bias tone to suppress the SOAEs is predicted by the darker line in each panel which has a slope of 8 dB/octave. Data reflect an average across the two trials.

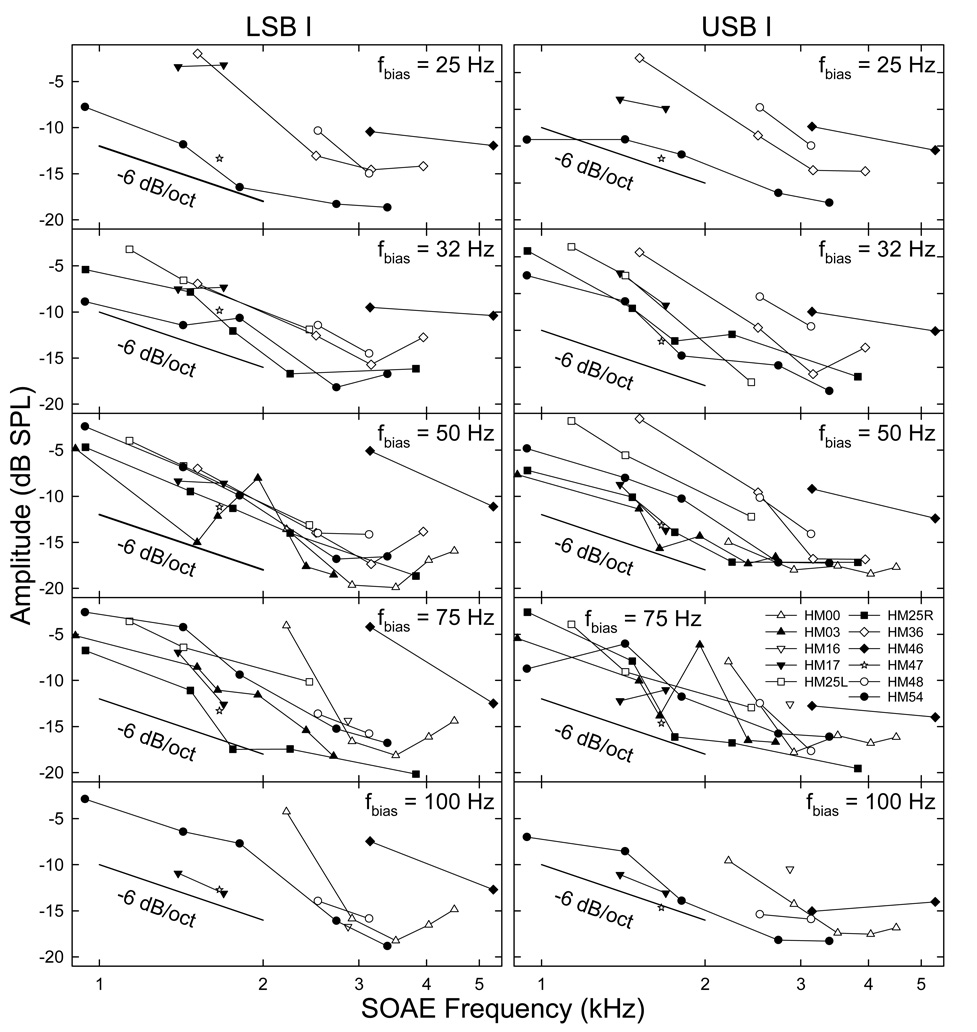

Because the extent of temporal AM in SOAE can be represented by the magnitudes of the sidebands, the peak levels of sidebands I were measured for all SOAE components to form a sideband vs. SOAE frequency function (Fig. 6). The maximal sideband I amplitudes for different SOAEs decreased with increasing SOAE frequencies. Except the upper end of the SOAE frequency range, the slope of these sideband-frequency functions approached a slope of −6 dB/octave, similar to the SOAE-grams (Fig. 2). For frequencies greater than about 4 kHz, the slope became shallower, because of the smaller SOAE amplitudes and limited power of the low-frequency bias tone in this region. Compared to Fig. 2 where the amplitudes of the SOAEs were more random for a single subject, the maximal sidebands for these SOAEs tended to decline more monotonically towards high frequencies. In other words, these maximal sidebands were not quite parallel to their corresponding SOAE-grams. This seemed to suggest that the sizes of the sidebands was more related to the influence of the bias tone than the SOAE amplitude.

Fig. 6. Maximal sidebands I amplitudes.

Each data point reflects the highest sideband amplitude a bias tone can produce. SOAEs with lower frequencies show larger sidebands. This correlates with the distribution of the original SOAE amplitudes (Fig. 2). The dark line in each panel indicate the slope of this trend (−6 dB/octave). Data reflects an average across the two trials.

C. Mechanical effects

1. Quasi-static modulation patterns

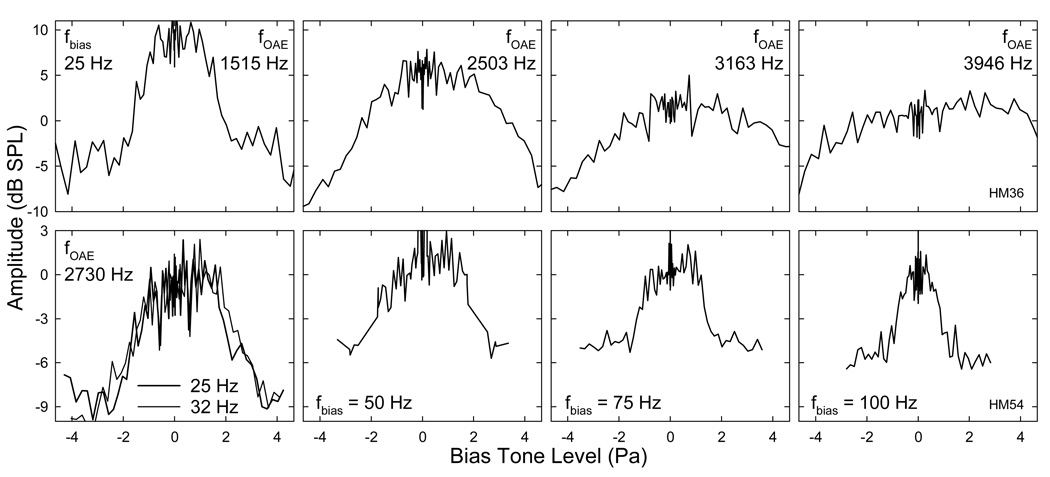

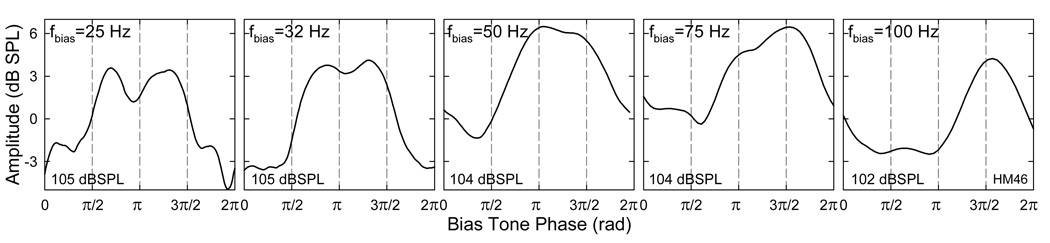

The influence of mechanical biasing of the cochlear partition on the SOAE amplitudes was examined by measuring the modulation patterns. Two types of SOAE modulation patterns were derived: quasi-static and temporal modulation patterns. The quasi-static modulation pattern represented the effect of biasing the cochlear partition in different directions as the SOAE magnitude was measured at opposing extremes of the bias tone. This modulation patterns generally demonstrated a bell-shape which varied with both SOAE and bias tone frequencies (Fig. 7). The SOAE magnitude showed a maximum near 0 Pa biasing pressure and reduced with increasing the pressure in either direction. At the peak region of the modulation pattern, the SOAE was unstable and showed an up to 6 dB fluctuation. When the SOAE became suppressed, the amplitude fluctuation was also limited. The maximal reduction in SOAE amplitude or modulation depth, represented by the difference between the peak and trough of the pattern, was often more than 10 dB. For a single bias tone of a fixed frequency, the modulation pattern varied with the frequencies of SOAEs (Fig. 7 top panels). The modulation pattern became flatter and wider towards higher SOAE frequencies. This is consistent with the limited power of the low-frequency bias tone in high frequency region where the suppression only occurred at very high biasing levels. Focusing on a single SOAE component (Fig. 7 bottom), there was an effect of the fbias on the quasi-static modulation pattern. The reduction of SOAE amplitude became more abrupt and the modulation patterns were narrowed for higher fbias. Such a variation in the modulation pattern was due to the more effective suppression by higher-frequency bias tones.

Fig. 7. Quasi-static modulation patterns.

Top row: effects of a fixed bias tone on SOAEs with different frequencies. The amplitudes of SOAEs show a bell shape. The modulation depth (height of the pattern) reduces and the width of the pattern increase with the SOAE frequency. Bottom row: effect of fbias on the modulation pattern. The modulation width becomes narrower with the increase in fbias because of the increased relative strength of the bias tone with respect to the SOAE. Data reflects an average across the two trials. Note: the fluctuations of SOAE amplitudes at the peak regions of the modulation patterns.

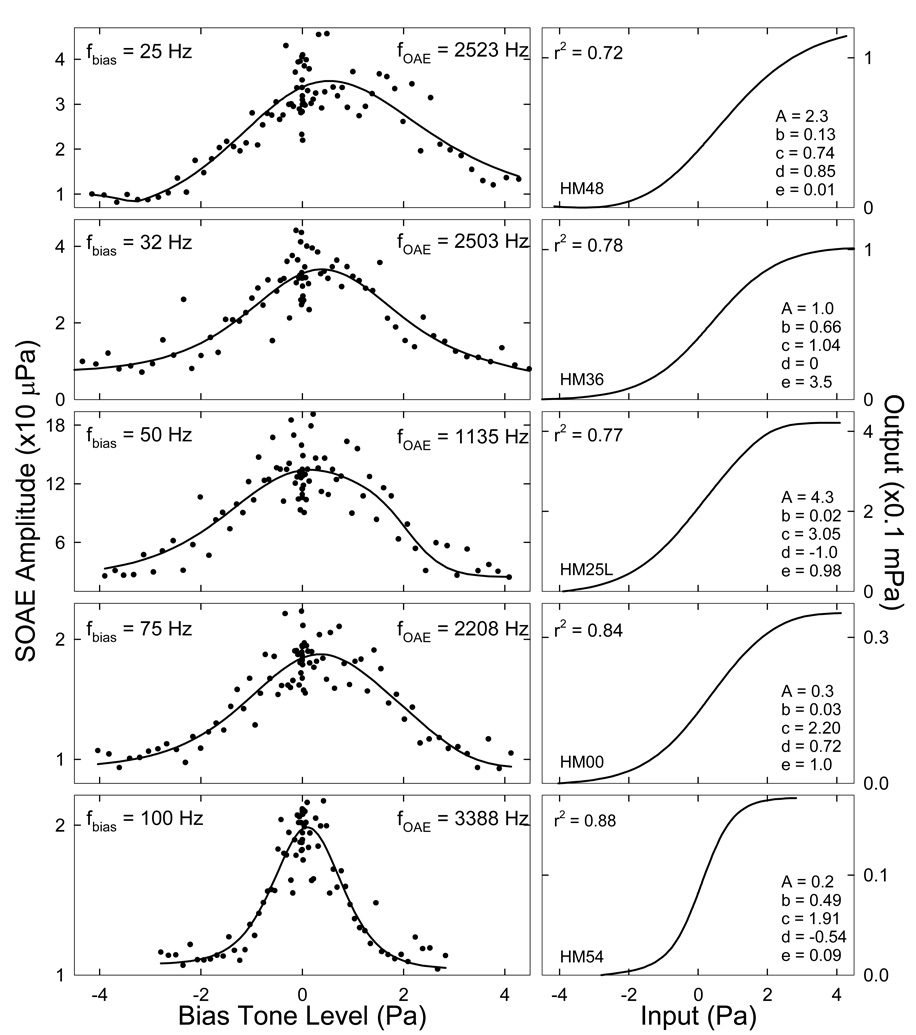

Suppression of SOAE when the cochlear partition was displaced in either direction was consistent with a saturating nonlinearity where the gain is reduced at the extremes of the input. The bias-tone induced motion of the cochlear partition could most likely affect the hair cell transduction channels. Thus, the shape of the modulation pattern was self-explanatory for the cause of SOAE suppression, i.e., the modulation of the cochlear transducer gain by shifting the operating point. Therefore, the modulation pattern was modeled and fit with the first derivative of the hair cell FTr in the form of a second-order Boltzmann function (Bian et al., 2002):

| (1) |

where G is the first derivative of a Boltzmann function FTr = A/[1+M(1+N)], x is the cochlear partition displacement represented by the biasing pressure at the peaks and troughs, A is a scaling factor, b and d are parameters relating to the slope of the transducer curve, c and e are constants setting the transducer operating point. Representations of the model fit and the FTr parameters for each fbias are illustrated in Fig. 8. The correlation coefficients (r2) for the fits ranged from about 0.7 to 0.9. The derived Boltzmann functions (right panels) all consisted of a sigmoid shape with slight variations in slope and symmetry.

Fig. 8. Quasi-static modulation patterns and cochlear FTr.

The SOAE amplitudes as a function of the peak level of the bias tones at each frequency (scattered points) are fit with the first derivative of a second-order Boltzmann function (Eq. 1). The correlation coefficients (r2) of the fits (solid lines) range from 0.72 to 0.88. The shapes of the derived cochlear FTr are similar despite small variations. The obtained Boltzmann parameters are indicated in the right panels. Data reflect an average across the two trials.

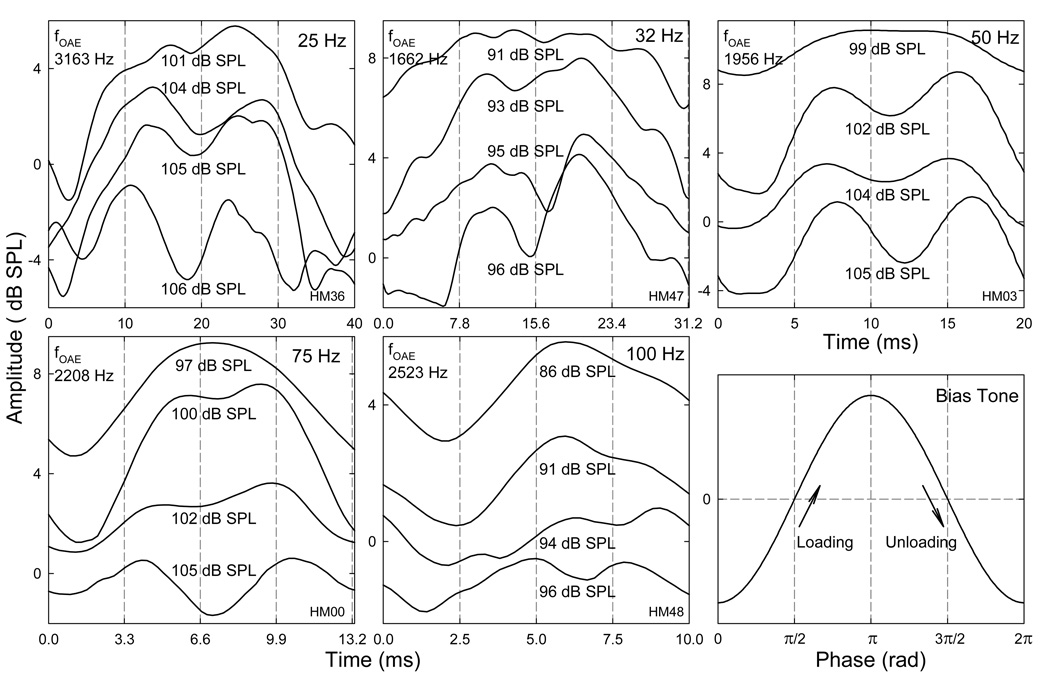

2. Temporal (period) modulation pattern

Another aspect of mechanical alteration of SOAE was the temporal modulation of emission amplitudes. Because the SOAE magnitudes were quite small (< 5 dB SPL in most cases), the SOAE envelopes obtained from IFFT were subject to contaminations from random noise and acoustic emissions from multiple reflections in the cochlear capsule. As shown in Fig. 9A, the SOAE appeared to be noisy and irregular. With careful comparison with the bias tone (lower trace), it was not difficult to notice that the SOAE envelope peaked twice within each biasing cycle starting with a trough. Such a periodicity was confirmed by a spectral analysis of the SOAE envelope (Fig. 9B). Two large peaks appeared at the fbias (50 Hz) and 2fbias (100 Hz) suggesting that there was a regularity repeating in one and one half basing cycle. To reduce the noise and other contaminations, segments of the SOAE envelope corresponding to 20 ~ 86 biasing periods were averaged to produce a period modulation pattern (Fig. 9C). Since only the bias tones with high levels can effectively modulate the emissions, the period modulation patterns obtained from the top 20 biasing levels (a 15 dB range) were averaged across the two trials and examined. The most typical period modulation pattern consisted of two peaks each corresponding to the zero-crossings of the bias tone with a short delay. Each half of the period modulation pattern marked by a large peak was similar to the bell-shaped first derivative of the cochlear FTr (Fig. 8 left).

Fig. 9. Temporal modulation of SOAE.

A: Temporal envelope obtained from IFFT of the spectral contents around the SOAE. Referenced to the bias tone (lower trace), it is noticeable that two SOAE peaks present within one biasing cycle (between two vertical dashed grid lines). B: Spectrum of the SOAE envelope in panel A. Note: two large peaks present at fbias (50 Hz) and 2fbias (100 Hz) indicating that a temporal pattern repeats once and twice in every biasing cycle. C: Period modulation pattern derived from averaging the SOAE envelope over 44 biasing cycles. The SOAE amplitude shows two peaks each correlates to a zero-crossing of the bias tone (lower trace).

As the Lbias reduced, the SOAE period modulation patterns showed progressive variations (Fig. 10). The most noticeable change was the decrease in the depth of the notch between the two SOAE peaks which was induced by the positive biasing extreme (lower right panel). As a result of the decreased suppression of SOAE at the positive biasing peak, the two SOAE peaks began to merge (top curves). Moreover, the SOAE still remained to be suppressed at the negative biasing extremes, but with smaller modulation depths. These different modulation patterns could be a source for the variation in the number and sizes of the sidebands around the SOAE component (Fig. 3). The single-peaked period modulation pattern was similar to a simple sinusoidal AM signal which contained only one sideband on each side of the SOAE. Using the bias tone as a reference, it was noted that the delay of the second SOAE peak appeared smaller and even lead the zero-crossing of the falling biasing pressure.

Fig. 10. Period modulation patterns.

Note: the systematic change in the period modulation pattern of SOAE as the Lbias varies in each panel. As Lbias decreases (from bottom trace to top), the SOAE amplitude increases with merging of the two peaks. Each half of the bottom traces is similar to the first derivative of the Boltzmann function. The bias tone phase is shown in the lower right panel for a reference. Loading: a monotonic increase in biasing pressure; Unloading: a monotonic decrease in the instantaneous biasing pressure.

The effect of the fbias on the SOAE period modulation pattern was a transition from a double peaked pattern to a single peaked one (Fig. 11). At high bias tone levels, as the fbias increased, the first SOAE peak corresponding to the loading of cochlear partition became considerably delayed and merged with the second peak (Fig. 11 middle panels and Fig. 10 lower middle panel). At the highest fbias (100 Hz), the first SOAE peak was suppressed so much that it never recovered. In this case, the period modulation pattern only contained a single SOAE peak that was related to the unloading of the cochlear partition. Thus, for fast biasing of the cochlear structures, increasing in the biasing pressure or loading would produce more suppression than decreasing the pressure or unloading. Consider the sequence of events within one biasing cycle, the delay of the first peak was due to the prolonged suppression from the negative maximal biasing pressure, and biasing in the positive direction was less effective. This unevenness in SOAE suppression and modulation depending on the directions of cochlear partition motion was a consequence of the asymmetry in cochlear transduction (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8) where biasing in the negative pressure direction yielded smaller SOAE amplitudes which could be translated into more compression in the cochlear FTr.

Fig. 11. Effect of the fbias on the period modulation pattern.

As the fbias increases, the period modulation pattern demonstrates a merging of the two peaks, further delay and suppression of the first peak. This represents a transition from the double peaked pattern to a single peaked one which implies a reduction in the number of sidebands in the frequency domain. Note: at 100 Hz fbias, the SOAE remains to be suppressed throughout the loading process and released during unloading. The first suppression phase is a delayed effect of displacing the cochlear partition in the negative pressure direction.

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Spectral features of SOAEs

The general properties of the SOAEs measured in the present study include 1) 1/10 of the subjects, esp., females, have large SOAEs, 2) if present in an ear, usually there are on average about three SOAE components, 3) for majority (64%) of the subjects, SOAEs are found in both ears, with a higher occurrence in the right ears, and 4) the SOAEs frequencies are distributed in the range from 0.9 to 5 kHz in a spectral shape of a low-pass filter with a −6 dB/octave slope (Fig. 2). These descriptive features are inline with many observations (see Probst et al., 1991 for a review). The observed spectral characteristic of a low-pass filter in SOAE amplitudes is consistent with the studies in infants, young, and older adults (Lonsbury-Martin et al., 1991; Braun, 2006). The 6-dB/octive reduction rate of SOAE amplitude with increasing frequency is in close agreement with the results of some large scale investigations (Moulin et al., 1993; Penner et al., 1993). It is naturally supposed that this filtering effect is a result of the reverse transmission of the middle and outer ears. However, the middle and outer ear are band-pass filters with center frequency located around 2~3 kHz (Aibara, et al., 2001; Whittemore et al., 2004). Anatomic evidences showed that the cochlear hair cell irregularities, such as extra or missing OHCs and microstructural changes in these cells, are prominent in the low- and mid-frequency region (Lonsbury-Martin et al., 1988). From a developmental perspective, there could be more immature OHCs that are innervated with afferent or reciprocal fibers in the apical cochlear partition (Pujol, 2001; Thiers et al., 2002) where the efferent synapses are sparse (Guinan et al., 1984). The lack of efferent control over these OHCs in the low-frequency region could be the basis for the generation of SOAEs and the low-pass filter shape in their frequency-amplitude distribution. This could account for the developmental reduction in SOAE amplitudes and downward shift in SOAE frequencies (Burns et al., 1994; Braun, 2006). Therefore, the appearances of the SOAEs provide clues for their underlying generating mechanisms.

B. Suppression and modulation: a nonlinear mechanism

Until the present study, there has been no report on the low-frequency modulation of SOAEs. The major findings of the present study are the suppression of SOAE amplitudes, the generation of multiple sidebands around SOAE components, and the phase-dependent AM of SOAE. These results are parallel to studies on low-frequency biasing of DPOAEs in both experimental animals (Frank and Kössl, 1996; Bian et al., 2002, 2004; Bian, 2004, 2006) and humans (Scholz et al., 1999; Bian and Scherrer, 2007). The details of the suppression and modulation of the SOAEs, in particular, are quite similar to the results obtained from the cubic difference tone (2f1-f2, CDT). For example, suppression with Lbias, presence of single or multiple sidebands, the bell-shaped quasi-static modulation pattern,and the two peaked period modulation pattern are common in both SOAE and CDT. Similar phenomena have been found with other types of OAEs, such as stimulus-frequency OAEs (Neely, et al., 2005) and tone-burst evoked OAEs (Zwicker, 1981). In the latter study, “suppression period patterns” with a progressive change from two amplitude maxima to a single peak when decreasing the level of a low-frequency suppressor was observed. This observation is similar to the period modulation patterns shown in Fig. 10. This suggests that these different OAEs may share the same generating mechanisms: the nonlinear transduction processes of the cochlear OHCs.

In addition, this generating mechanism can be evident by the nonlinear interference between externally presented acoustic signals and the SOAEs. For example, investigations on the interaction of an external tone with SOAEs have shown that they can be suppressed (Zurek, 1981; Rabinowitz and Widin, 1984; Bargones and Burns, 1988) and DPOAEs can be generated (Frick and Matthies, 1988; Norrix and Glattke, 1996), esp., when the external tone frequency is below the SOAE. One finding of the present study is that the suppression of SOAEs occurs more effectively if the bias tone is closer in frequency to the SOAE (Fig. 4 and Fig. 7). This reflects that the SOAEs maybe generated locally on the cochlear partition due to the tonotopic tuning property and the hair cell transducer channels are saturated when the external stimulus reaches the SOAE generating site. The results of Rabinowitz and Widin (1984) that when the suppressor tone is set at 500 Hz, the level required to reduce the SOAE at 1350 Hz is above 70 dB SPL is inline with the 100 dB SPL for bias tones at or below 100 Hz (Fig. 4 top). The slopes of about 6~8 dB/octave on the iso-suppression and maximal sideband curves (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6) are consistent with the iso-modulation function in a recent study on low-frequency biasing of DPOAEs (Marquart et al., 2007) and correlated with the tail of suppression tuning curves measured from SOAEs (Zurek, 1981; Bargones and Burns, 1988). These nonlinear interactions could generate more spectral and temporal information that are necessary for sensitive detection of sound.

Another finding indicates that the AM occurs prior to suppression as marked by the appearance of sidebands (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Indeed, this is similar to the results of Norrix and Glattke (1996) that when the suppressor frequency (fs) is carefully placed closely below the frequency of an SOAE (fOAE), a DPOAE can be generated at 2fs-fOAE. In addition, when the SOAE is suppressed the DPOAE magnitude reaches a peak similar to Fig. 4. This DPOAE can be considered as an LSB II, i.e., fOAE -2(fOAE-fs), if the cochlear transducer is thought to be modulated by the beats (fOAE-fs) created by the two tones (Brown 1994; van der Heijden, 2005). When the suppressor tone is shifted more than an octave below the SOAE in the case of the low-frequency biasing, the hair cells at the SOAE generating site should be modulated at the fs. The sidebands should present at fOAE-n·fs, where n is an integer (Bian, 2006). This has been verified by direct observations of two-tone suppression on basilar membrane (BM) vibration (Rhode and Cooper, 1993) and auditory nerve (Temchin et al., 1997) that the response of the characteristic frequency (CF) was reduced with the presence and growth of the spectral components at fCF±n·fs. Such opposite behaviors of CF response and its sidebands occur with an AM of the CF (fs ≪ fCF). These observations suggest that the sensory hair cells could phase-lock to a lower frequency component in the incoming acoustic stimuli comparing to their own CF. In the time domain, this is probably crucial for a slower operation of the hair cells and the rest of the auditory system to preserve energy. Beats and roughness observed by Long (1998) also were occasionally reported by the subjects in the present study. Compared with the spectral and temporal features of the AM of SOAEs (Fig. 3 and Fig. 9), these perceptual consequences are not difficult to understand. Whether the DPs or simply the sidebands from AM are used for sensitive sound detection, they are all generated by the nonlinearity in the hair cell transducers. Therefore, suppression and distortion are spectral representations of the temporal actions of the sensory hair cells.

Because SOAEs are generated from the intrinsic processes of the inner ear, they tend to be influenced by any subtle changes in the cellular environment of the hair cells. This sensitivity of SOAEs is demonstrated by the amplitude fluctuation when the bias tone level is low (Fig. 4 top and Fig. 7). The amplitude variability of SOAE is much higher than the DPOAEs with similar magnitudes and under similar biasing conditions (Bian and Scherrer, 2007). Without biasing, variability in SOAE amplitude is common (Lind and Randa, 1990; Burns, 1994; Smurzynski and Probst, 1998). This instability of SOAEs implicates that they are products of some dynamic processes of the hair cell transduction, possibly a limit-cycle oscillation of the stereocillial bundles (Talmadge et al., 1991; Nadrowski, et al., 2004). The instability and spontaneous oscillation of the hair cell transduction channels seem necessary so that any sound induced change in the cochlear fluid pressure could modulate the amplitude and frequency of the movement of the hair bundles to provide a high sensitivity. In normal subjects, hearing thresholds at the SOAEs frequencies are indeed lower than other frequencies (Long and Tubis, 1988) that could cause the well-known “microstructures” in high-resolution audiograms.

C. Period modulation patterns

The period modulation pattern shows two peaks each corresponds to a zero-crossing of the bias tone. Variations from the typical pattern are often found in three aspects: 1) merging of the two SOAE amplitude peaks with reducing biasing levels, 2) suppression of the first peak but not the second while increasing fbias, and 3) delays of the SOAE peaks (Fig. 10 and Fig. 11). These changes in period modulation pattern determine the size and number of the spectral sidebands. Merging of the SOAE peaks indicates that BM displacement or stereocilial movement in the positive sound pressure direction is less effective in suppressing the SOAE than the opposite direction (Fig. 7 top). This asymmetry was observed in “low-side” suppression of the CF response on the BM (Rhode and Cooper, 1993) where a displacement towards scala tympani (ST) reduced the CF vibration more than the other direction. Moving the BM towards ST could push more OHC transduction channels into closed state, thus reducing the mechanical responses of the cells that produce SOAEs. In comparison, displacing the BM towards scala vestibuli (SV) can enhance the electrically evoked OAEs (Kirk and Yates, 1998).

For faster biasing, esp., at 100 Hz, suppression of SOAE during the displacements towards ST seems to prolong and prevent the SOAE amplitude from recovering when the cochlear partition returns to its resting position (Fig. 11). Such a period modulation pattern is similar to the period histogram of auditory nerve response during low-frequency suppression (Cai and Geisler, 1996). This prolonged effect probably correlates with the 5 – 10 ms time constant for the recovery of SOAE from a suppression produced by a high frequency tone (Schloth and Zwicker, 1983). The mechanism of the multi-millisecond recovery time is unclear, perhaps due to the slow adaptation of the motor proteins in the OHC stereocilia. There is also a short delay of the SOAE peaks relative to the zero-crossings of the bias tone, esp., at high Lbias and low fbias (Fig. 10). This delay (≤ 1 ms) indicates that the mechanism responsible for the suppression takes time to activate, possibly via a feedback to adjust the hair cell transducer gain (Bian et al., 2004). Schloth and Zwicker (1983) also noticed that there was a less than 2 ms delay in the suppression and recovery of SOAEs. Moreover, it is shown that a suppressor should be placed 1–2 ms prior to an emission evoking click to take effect (Harte et al., 2005). However, this time dependency of SOAE modulation is complicated by the bias tone level and frequency, e.g., the second peak can occur earlier than the zero-crossing in the unloading phase (Fig. 10).

VI. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Subjects with relatively large SOAEs were selected to receive low-frequency modulation under various signal conditions. The results showed a combined suppression and modulation of the SOAE amplitudes at high biasing levels. In the spectral domain, reduction in SOAE amplitude was observed with the generation and growth of sidebands when the Lbias was increased. For a fixed bias tone, the extent of suppression and behavior of modulation for an SOAE varied depending on the frequency and amplitude of the particular SOAE. The ability of the bias tone to suppress and modulate SOAE decreased with the frequency of SOAEs at a 6–8 dB/octave rate. The quasi-static modulation patterns of SOAEs demonstrated a bell-shape which was associated with the first derivative of a nonlinear FTr of the cochlea. In the time domain, SOAEs showed an AM depending on the phase of the bias tone. Within a biasing cycle, the SOAE envelope peaked twice near the zero-crossings of the bias tone. This typical period modulation pattern varied systematically with the Lbias and fbias. The temporal behaviors of SOAE amplitudes reflect a time-dependent shifting of the operating point on the cochlear FTr. These comparable results to a recent observation on low-frequency biasing of DPOAEs in humans (Bian and Scherrer, 2007) suggest that the cochlear nonlinearity inherited with the hair cell transduction could be involved in the generation of SOAEs. More research are needed to elucidate the relation between the cochlear nonlinearity and other mechanisms (e.g., Shera, 2003) in the formation of SOAEs. The influence of SOAEs on the accuracy of estimating the cochlear FTr should be determined for possible clinical applications of the low-frequency biasing technique.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Assistance from Nicole Scherrer in recruiting subjects is appreciated. The authors thank the clinical staff in the Department of Speech and Hearing Science at ASU for sharing their equipment and the subject for participating in the study. This work was supported by a grant (R03 DC006165) from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the NIH.

Footnotes

PACS numbers: 43.64Jb, 43.64.Kc, 43.64.Bt [BLM]

REFERENCES

- Aibara R, Welsh JT, Goode RL. Human middle-ear sound transfer function and cochlear input impedance. Hear. Res. 2001;152:100–109. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargones JY, Burns EM. Suppression tuning curves for spontaneous otoacoustic emissions in infants and adults. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1988;83:1809–1816. doi: 10.1121/1.396515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L. Spectral fine-structures of low-frequency modulated distortion product otoacoustic emissions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006;119:3872–3885. doi: 10.1121/1.2200068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L. Cochlear compression: Effects of low-frequency biasing on quadratic distortion product otoacoustic emission. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004;116:3559–3571. doi: 10.1121/1.1819501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L, Chertoff ME. Modulation patterns and hysteresis: Probing cochlear dynamics with a bias tone. In: Nuttall AL, Ren T, Gillespie P, Grosh K, de Boer E, editors. Auditory Mechanisms: Processes and Models. Singapore: World Scientific; 2006. pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bian L, Scherrer NM. Low-frequency modulation of distortion product otoacoustic emissions in humans. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007;122:1681–1692. doi: 10.1121/1.2764467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L, Chertoff ME, Miller E. Deriving a cochlear transducer function from low-frequency modulation of distortion product otoacoustic emissions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002;112:198–210. doi: 10.1121/1.1488943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L, Linhardt EE, Chertoff ME. Cochlear hysteresis: Observation with low-frequency modulated distortion product otoacoustic emissions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004;115:2159–2172. doi: 10.1121/1.1690081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M. A retrospective study of the spectral probability of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions: Rise of octave shifted second mode after infancy. Hear.Res. 2006;215:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M. Inferior colliculus as candidate for pich extraction: multiple support from statistics of bilateral spontaneous otoacoustic emissions. Hear.Res. 2000;145:130–140. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM. Modulation of the hair cell motor: A possible source of odd-order distortion. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1994;96:2210–2215. doi: 10.1121/1.410161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns EM, Campbell SL, Arehart KH. Longitudinal measurements of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions in infants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1994;95:385–394. doi: 10.1121/1.408330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Geisler CD. Suppression in auditory-nerve fibers of cats using low-side suppressors. II. Effect of spontaneous rates. Hear. Res. 1996;96:113–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank G, Kössl M. The acoustic two-tone distortions 2fl-f2 and f2-fl and their possible relation to changes in the operating point of the cochlear amplifier. Hear. Res. 1996;98:104–115. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick LR, Matthies ML. Effects of external stimuli on spontaneous otoacoustic emissions. Ear Hear. 1988;9:190–197. doi: 10.1097/00003446-198808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold T. Hearing. II. The physical of the basis of the action of the cochlea. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B. 1948;135:492–498. [Google Scholar]

- Guinan JJ, Jr, Warr WB, Norris BE. Topographic organization of the olivocochlear projections from the lateral and medial zones of the superior olivary complex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1984;226:21–27. doi: 10.1002/cne.902260103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte JM, Elliott SJ, Kapadia S, Lutman ME. Dynamic nonlinear cochlear model predictions of click-evoked otoacoustic emission suppression. Hear. Res. 2005;207:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp DT. Stimulated acoustic emissions from within the human auditory system. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1978;64:1386–1391. doi: 10.1121/1.382104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk DL, Yates GK. Enhancement of electrically evoked oto-acoustic emissions associated with low-frequency stimulus bias of the basilar membrane towards scala vestibuli. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998;104:1544–1554. doi: 10.1121/1.424365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind O, Randa JS. Spontaneous otoacoustic emissions: incidence and short-time variability in normal ears. J. Otolaryngol. 1990;19:252–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsbury-Martin BL, Cutler WM, Martin GK. Evidence for the influence of aging on distortion-product otoacoustic emissions in humans. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1991;89:1749–1759. doi: 10.1121/1.401009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsbury-Martin BL, Martin GK, Probst R, Coats A. Spontaneous otoacoustic emissions in a nonhuman primate: II. Cochlear anatomy. Hear. Res. 1988;33:69–94. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GR. Perceptual consequences of the interactions between spontaneous otoacoustic emissions and external tones. I. Monaural diplacusis and aftertones. Hear. Res. 1998;119:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GR, Tubis A. Investigations into the nature of the association between threshold microstructure and otoacoustic emissions. Hear. Res. 1988;36:125–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley GA, Taschenberger G. Spontaneous otoacoustic emissions from a bird: a preliminary report. In: Duifhuis H, Horst JW, van Dijk P, van Netten SM, editors. Biophysics of Hair Cell Sensory Systems. Singapore: World Scientific; 1993. pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt T, Hensel J, Mrowinski D, Scholz G. Low-frequency characteristics of human and guinea pig cochleae. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007;121:3628–3638. doi: 10.1121/1.2722506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GK, Lonsbury-Martin BL, Probst R, Coats A. Spontaneous otoacoustic emissions in the nonhuman primate: a survey. Hear. Res. 1985;20:91–95. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(85)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Bozovic D, Choe Y, Hudspeth AJ. Spontaneous oscillation by hair bundles of the bullfrog′s sacculus. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:4533–4548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04533.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D, Plattsmier HS. Aspirin abolishes spontaneous otoacoustic emissions. Hear. Res. 1984;16:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Moulin A, Collet L, Morgan A. Interrelations between transiently evoked otoacoustic emissions, spontaneous otoacoustic emissions and acoustic distortion products in normally hearing subjects. Hear. Res. 1993;65:216–233. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90215-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadrowski B, Martin P, Jülicher F. Active hair bundle motility harnesses noise to operate near an optimum of mechanosensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acd. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:12195–12200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403020101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely ST, Johnson TA, Garner CA, Gorga MP. Stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions measured with amplitude-modulated suppressor tones. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005;118:2124–2127. doi: 10.1121/1.2031969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrix LW, Glattke TJ. Distortion product otoacoustic emissions created through the interaction of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions and externally generated tones. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1996;100:945–955. doi: 10.1121/1.416206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama K, Wada H, Kobayashi T, Takasaka T. Spontaneous otoacoustic emissions in the guinea pig. Hear. Res. 1991;56:111–121. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90160-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AR, Wilson JP. Spontaneous and evoke acoustic emissions in the frog Rena esculenta. J. Physiol. (London) 1982;324:66P. [Google Scholar]

- Penner MJ, Glotzbach L, Huang T. Spontaneous otoacoustic emissions: measurement and data. Hear. Res. 1993;68:229–237. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90126-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst R, Lonsbury-Martin BL, Martin GK. A review of otoacoustic emissions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1991;89:2017–2067. doi: 10.1121/1.400897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol R. Neural anatomy of the cochlea: development and plasticity. In: Jahn AF, Santos-Sacchi J, editors. Physiology of the Ear. 2nd Ed. Singular, NY: 2001. pp. 515–528. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinnowitz WM, Windin GP. Interaction of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions and external sounds. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1984;76:1713–1720. doi: 10.1121/1.391618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhode WS, Cooper NP. Two-tone suppression and distortion product on the basilar membrane in the hook region of cat and guinea pig cochleae. Hear. Res. 1993;66:31–45. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci AJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Active hair bundle motion linked to fast transducer adaptation in auditory hair cells. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7131–7142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07131.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloth E, Zwicker E. Mechanical and acoustical influences on spontaneous oto-acoustic emissions. Hear. Res. 1983;11:285–193. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(83)90063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz G, Hirschfelder A, Marquardt T, Hensel J, Mrowinski D. Low-frequency modulation of the 2f1-f2 distortion product otoacoustic emissions in the human ears. Hear. Res. 1999;130:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shera CA. Mammalian spontaneous otoacoustic emissions are amplitude-stabilized occhlear standing waves. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2003;114:224–262. doi: 10.1121/1.1575750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smurzynski J, Probst R. The influence of disappearing and reappearing spontaneous otoacoustic emissions on one subject’s threshold microstructure. Hear. Res. 1998;115:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CE, Hudspeth AJ. Effects of salicylates and aminoglycosides on spontaneous otoacoustic emissions in the Tokay gecko. Proc. Natl. Acd. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:454–459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmadge CL, Tubis A, Wit HP, Long GR. Are spontaneous otoacoustic emissions generated by self-sustained cochlear oscillators? J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1991;89:2391–2399. doi: 10.1121/1.400958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temchin AN, Rich NC, Ruggero MA. Low-frequency suppression of auditory nerve responses to characteristic tones. Hear. Res. 1997;113:29–56. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00129-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiers FA, Burgess BJ, Nadol JB., Jr Reciprocal innervation of outer hair cells in a human infant. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2002;3:269–278. doi: 10.1007/s101620020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden M. Cochlear gain control. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005;117:1223–1233. doi: 10.1121/1.1856375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore KR, Merchant SN, Poon BB, Rosowski JJ. A normative study of tympanic membrane motion in humans using a laser Doppler vibrometer (LDV) Hear. Res. 2004;187:85–104. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurek PM. Spontaneous narrowband acoustic signals emitted by human ears. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1981;69:514–523. doi: 10.1121/1.385481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker E. Masking-period patterns and cochlear acoustical responses. Hear. Res. 1981;4:195–202. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(81)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]