Abstract

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii has two apically localized flagella that are maintained at an equal and appropriate length. Assembly and maintenance of flagella requires a microtubule-based transport system known as intraflagellar transport (IFT). During IFT, proteins destined for incorporation into or removal from a flagellum are carried along doublet microtubules via IFT particles. Regulation of IFT activity therefore is pivotal in determining the length of a flagellum. Reviewed is our current understanding of the role of IFT and signal transduction pathways in the regulation of flagellar length.

Keywords: Chlamydomonas, flagellar length, cilia, intraflagellar transport, signal transduction

1. Introduction

Cells are able to carefully measure and regulate not only their own size but also that of their organelles. This regulation of size and thus volume is essential for cellular viability and reflects the changing environment of the cell. For example, the size and number of peroxisomes varies depending on the nutrients available for metabolism [1]. Regulation of organelle size is perhaps most apparent in the regulation of flagellar (ciliary) length. Cilia and/or flagella are microtubule-based organelles that project from the surface of cells. Cilia and flagella are identical in structure and in this review are considered to be interchangeable terms. The exquisite control that cells have over flagellar length is perhaps best demonstrated by the unicellular eukaryote Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Chlamydomonas maintains its two apically localized flagella at an equal length. In addition, within a population of cells there is little variation in flagellar length.

In contrast to mammalian systems, flagella are not essential for viability in Chlamydomonas. This key difference has allowed the generation of a number of mutants that are defective in flagellar assembly and/or function. These flagellar mutants have been useful in both classical genetic studies and complementation analysis in stable diploids. Complementation of a number of flagellar defects has also been observed in temporary quadriflagellate dikaryons formed by cell fusion during mating. For example, when cells with paralyzed flagella were mated with wild-type cells, the mutant flagella began to beat within a few minutes [2, 3, 4]. Moreover, the ease of isolation and purification of flagella from Chlamydomonas and the subsequent fractionation of flagella into its separate components has allowed not only the assignment of proteins to various structures that comprise the axoneme but also identification of the role they play in flagellar assembly and function [5].

The building block for flagella is the 9 + 2 microtubular axoneme. The basal body, a complex comprised of triplet microtubules present at the base of each flagellum, serves as the template for nucleation of the 9 outer doublet microtubules. Localization of the basal bodies, and thus the flagella, within the cell is regulated by a complex fibrous structure that connects the basal bodies not only to each other but to the nucleus and the rootlet microtubules of the cell body [6, 7]. Two singlet microtubules, known as the central pair, are present within the center of the axoneme. Dynein arms bind to the outer doublet microtubules and interact with adjacent doublet microtubules resulting in flagellar bending and thus motility. The outer doublet microtubules also provide the binding site for the radial spokes, a complex array of proteins that together with the central pair function to regulate flagellar motility [5].

2. Assembling a flagellum and intraflagellar transport

When flagella are removed from cells by mechanical shear or chemical stress, the cells immediately begin to grow new flagella [8]. This regenerative process occurs with deceleratory kinetics. The initial rate of flagellar elongation is rapid (~0.4 µm/min) but as the flagella approach their pre-deflagellation length the rate of flagellar growth slows (~0.15 – 0.2 µm/hour) [8]. As the flagella elongate, axonemal precursors are incorporated at the distal tip (i.e., the plus or fast-growing end of the microtubules) of flagella [9, 10]. Because these organelles do not contain the machinery for protein synthesis, ciliary proteins must be transported from their site of synthesis in the cell body to the flagella using a microtubule-based transport system known as intraflagellar transport (IFT).

IFT, first identified in Chlamydomonas, is the bidirectional movement of particles along the length of the flagella [11]. Biochemical analysis of IFT particles revealed that they are composed of two large multiprotein complexes, complex A and complex B [12]. Complex A consists of 4 proteins while 12 – 13 proteins interact to form complex B [12, 13, 14]. IFT particles together with the motor proteins FLA10 kinesin II and cytoplasmic dynein Dhc1b travel along the doublet microtubules underneath the flagellar membrane to transport flagellar proteins into and out of these organelles respectively [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20].

3. Active control of flagellar length in Chlamydomonas

In 1969, Rosenbaum et al. made the seminal observation that Chlamydomonas dynamically monitors flagellar length thus ensuring equality between the two flagella [8]. This active regulation of flagellar length was demonstrated by the deflagellation of cells under conditions sufficient to remove only one flagellum from individual cells, resulting in a population of “long-zero” cells. The remaining flagellum of the long-zero cells immediately began to shorten to an intermediate length while the amputated flagellum elongated. Once the amputated flagellum and the shortening flagellum reached comparable lengths, they then continued to elongate together until their pre-deflagellation length was obtained [8]. In some cells the shortening flagella overshot the point where disassembly should cease, causing the elongating flagellum to stop growing. The regrowth of this flagellum remained arrested until the resorbing flagellum had returned to the length of the elongating flagellum. Thus if the intact flagellum was resorbed to a point where its length was shorter than that of the elongating flagellum, growth of the elongating flagellum was suspended until the two flagella were at comparable lengths. This result suggests that cells dynamically monitor the length of each flagellum and actively enforce length equality between the two flagella.

The length of flagella is not controlled simply by regulating the pool size of flagellar proteins. When deflagellation (both flagella amputated) and regeneration occur in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, cells regenerate flagella that are one-half the pre-deflagellation length indicating that cells maintain a cytoplasmic pool of flagellar precursors [8]. A large cytoplasmic pool of ciliary precursors has been found in sea urchin embryos [21] and in the ciliate Tetrahymena [22].

Regulation of flagellar length in Chlamydomonas can also be manipulated pharmacologically [23]. For example, flagellar length is inversely related to the osmolarity of the culture medium, as osmolarity increased, flagellar length the decreased [24]. A number of other agents were subsequently shown to induce flagellar shortening such as the anesthetics halothane and lidocaine [25, 26], the cytoskeletal drugs colchicine and cytochalasin D [27] and the methylxanthines, isobutyl methylxanine (IBMX) [28] and caffeine [29]. Consistent with a role for IBMX as an inhibitor of phosphodiesterases, incubation of cells with H8 (an inhibitor of cyclic nucleotide protein kinases) also induced flagellar resorption [30]. Moreover, an elongation of the A microtubule and the concomitant accumulation of fibrous material at the tips of flagella was observed in response to increases in cAMP in Chlamydomonas gametes [31]. cAMP has also been observed to regulate the length of the primary cilium of MDCK cells [32]. Incubation of MDCK cells with a cell permeable analog of dibutyryl cAMP or with an activator of adenylyl cyclase resulted in cilia whose length was twice that of control cells. Incubation of cells with lithium chloride, a compound with the potential to affect multiple target proteins, induced elongation of flagella [30, 33, 34]. Finally, calcium has also been shown to play an important role in the regulation of the assembly state of flagella. Incubation of cells with various calcium chelating agents such as EGTA, pyrophosphate, or citrate resulted in the arrest of flagellar motility and the disassembly and absorption of flagella into the cell body at a rate of 0.1 µm/min [35, 36]. This shortening of flagella was fully and rapidly reversible by the re-addition of calcium to the culture medium [35].

4. Mutants of flagellar length control in Chlamydomonas

The most compelling evidence for the active control of flagellar length, however, is the behavior of mutants that can no longer regulate length [37, 38, 39]. To date, two classes of flagellar length mutants have been obtained. The first class includes six mutants with short flagella (shf) [38, 40, 41]. These shf mutants define three genes: SHF1 (three alleles), SHF2 (two alleles), and SHF3 (one allele). shf mutants have flagella that are of equal length but are only six µm long compared to the 12 µm long flagella of wild-type cells (Fig. 1, shf2). Although some paralyzed flagellar mutants with dynein arm defects also have short flagella, the shf mutants are motile and have no obvious defects in waveform [40, 41]. All of the shf mutants contained a cytoplasmic pool of flagellar precursors and were able to regenerate flagella with wild-type kinetics [38, 41]. Examination of flagellar lengths in temporary quadriflagellate dikaryons formed from shf x wild-type matings revealed that shf mutants are recessive to wild-type. The short flagella of these quadriflagellates elongated to wild-type length within minutes after cell fusion [41]. Double mutants containing various combinations of the shf alleles revealed that some allelic combinations resulted in a short flagella phenotype whereas others resulted in a flagellaless phenotype [41]. In addition, some shf1 and shf2 alleles have an additional temperature-sensitive phenotype. When grown at the permissive temperature, each of these mutants has short flagella; upon shifting to the restrictive temperature, however, the mutants are unable to assemble flagella after cell division suggesting an additional defect in flagellar assembly [41].

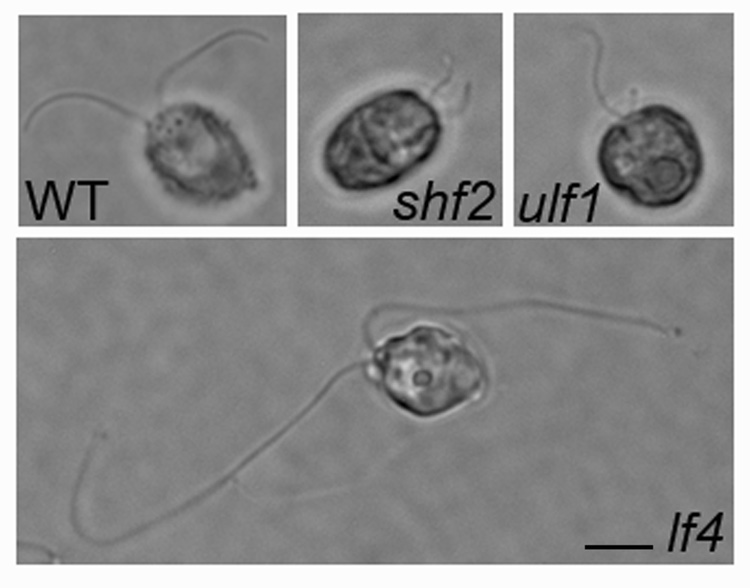

Figure 1. Flagellar phenotypes of mutants defective in length control.

Vegetatively growing cells were fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde and examined by phase contrast microscopy. Wild-type cells assemble two flagella that are equal in length (WT; wild-type); Short flagella mutants assemble two flagella that are equal in length but approximately half the length of wild-type cells (shf2). Unequal length mutants assemble one long and one short flagellum (ulf1). Long flagella mutants assemble two flagella that are two to three times wild-type length (lf4). Bar = 6 µm.

The second class of mutants includes both the long flagella (lf) and the unequal flagellar length (ulf) mutants [37, 39, 42, 43, 44]. To date, 21 lf/ulf mutants have been obtained by either chemical, UV, or insertional mutagenesis. These 21 lf/ulf mutants define four genes: LF1, LF2, LF3, and LF4. Interestingly, null alleles of LF2 (ulf2) and LF3 (ulf1/ulf3) have a different flagellar phenotype than the hypomorphic alleles of these genes [43, 45, 46]. While the hypomorphic alleles assembly excessively long flagella, most ulf cells are flagellaless or assemble only stumpy flagella. A small proportion of ulf cells, however, have one flagellum of wild-type or longer length and one stumpy flagellum (Fig. 1, ulf1) [43, 45, 46]. The flagellaless phenotype of ulf1 and ulf2 suggests that in addition to their role in the regulation of flagellar length, the gene products of LF2 and LF3 also function in flagellar assembly [45, 46]. In contrast to the short, stumpy flagella of ulf mutants, lf mutants have flagella that are often two to three times longer than wild-type (Fig. 1, lf4) [37, 42, 44]. Unlike wild-type or shf mutants, lf mutants have a considerable variation in flagellar length from cell to cell within a population.

Like the shf mutants, rescue of the long-flagella defect in all lf mutant strains by the cytoplasm of wild-type cells was observed in dikaryon experiments. Within minutes after mating, the lf flagella shortened to the length of the wild-type flagella indicating that some component(s) of the wild-type cytoplasm can “measure” flagellar length and actively lengthen (in the case of shf mutants) or shorten (in the case of lf mutants) flagella of abnormal length [42, 44].

In light of the rescue of the long-flagella phenotype in wild-type/lf temporary dikaryons and in stable diploids constructed from different lf mutants (e.g., lf1/lf2), it is surprising that the lf phenotype was not rescued in temporary dikaryons formed from lf × lf matings [42]. Dikaryons formed by lf × lf matings maintained either long flagella or only partially shortened flagella. The absence of rescue among lf/lf dikaryons suggests that this process might require formation of a protein complex that occurs in a cyclic manner and requires progression through a cell cycle.

Consistent with the suggestion that the LF gene products act in a complex, a new synthetic phenotype was observed with double mutants generated from any combination of lf1, and hypomorphic alleles of lf2 or lf3. Instead of the long flagella assembled by single mutants, the double mutants had flagella that are unequal in length [42, 45, 46]. In addition to their inability to sense and regulate flagellar lengths, lf1 and some lf2 and lf3 alleles regenerate flagella very slowly after amputation. This regeneration defect cosegregates with the lf phenotype and is discernable by a variable lag in the initiation of flagellar regeneration [42, 44]. The inability to regenerate flagella is surprising since the lf defect causes excessive assembly of flagella. Flagellar outgrowth in these mutants in the presence of cycloheximide suggests that the regeneration defect is not simply due to the absence of the precursor pool, although this could not be established for lf1 or lf2-1 due to their extreme regeneration defect [42]. In addition, the lf4 mutation in double mutant combinations was able to restore normal flagellar regeneration to lf1 mutants but not to lf2 mutants [44]. This result suggests that the wild-type gene product of LF4 is required to prevent flagellar assembly in the lf1 mutant. This implies that LF4p functions to stop flagellar assembly or alternatively to induce flagellar disassembly. These results are consistent with a model whereby cells are continually assembling flagella. Length would be controlled, in this model, by the transient activation of a disassembly program to return flagella to the desired length after flagella assemble past a genetically-determined optimal length.

lf1, lf2, and lf3 are capable of undergoing the long-zero response (i.e., they could sense and rectify inequality in flagellar length) [42]. If one flagellum was amputated the cells began to shorten their remaining long flagellum while the amputated flagellum regrew. These results suggest that both the signal and the mechanism for flagellar shortening are intact in these lf mutants. Interestingly, the rate of elongation of the amputated flagellum exceeded the rate of flagellar regeneration when both flagella were amputated. These results suggest that for hypomorphic lf mutants, regeneration of one flagellum is fundamentally different from the regeneration of two flagella. This difference could lie in the initial absorption and re-utilization of flagellar components in the long-zero cells that would be absent in cells with both flagella removed [47].

5. Genes involved in the regulation of flagellar length

Recently, a number of studies have begun to identify proteins that when mutated or their levels decreased by RNA interference (RNAi) have defects in assembling flagella of an appropriate length. Consistent with the pharmacological evidence that signal transduction plays a pivotal role in the regulation of flagellar length, the majority of these proteins are involved in signaling pathways.

5.1 Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 (GSK3)

One of the first signal transduction proteins shown to play a role in the regulation flagellar length was GSK3. The identification of GSK3 came from the observation that incubation of wild-type cells with mM concentrations of lithium chloride stimulated flagellar elongation in Chlamydomonas [30, 33, 34]. This elongation of flagella could occur in part by the partial recruitment of the cell body pool of flagellar precursors into flagella [33, 34]. Prolonged exposure to lithium (i.e., 24 hours) resulted in the resorption of flagella [34]. Examination of GSK3 (a known target for inhibition by lithium) revealed it was a flagellar component whose enzyme activity was inhibited by lithium [34]. Although the majority of GSK3 is present in cell bodies, a subfraction localizes to flagella where it interacts in a phosphate-dependent manner with the axoneme [34]. Examination of GSK3 during flagellar assembly revealed an increase in the level of the tyrosine phosphorylated and therefore presumably active form of GSK3 in flagella. The level of tyrosine phosphorylated GSK3 peaked by 5 min after the onset of regeneration, and then quickly returned to the pre-deflagellation level [34]. Further evidence for a role for GSK3 in the regulation of flagellar assembly comes from knock-down of GSK3 expression by RNAi. Using this method, GSK3 levels were decreased to 40% of control cells and resulted in the inability of the RNAi cells to assemble flagella [34]. Moreover, recent studies have demonstrated the requirement for GSK3β in the maintenance of primary cilia [48]. These observations suggest that GSK3 activity functions to regulate the assembly state of flagella.

5.2 NIMA-related kinases

NIMA-related kinases (NRK) have been implicated in the regulation of flagellar length in both Chlamydomonas and Tetrahymena [49, 50]. In Chlamydomonas, the NIMA-related kinase Cnk2p is a negative regulator of flagellar length [49]. Analysis of an ectopically expressed HA-tagged Cnk2p allowed its localization to punctate structures within flagella. Ectopic expression of HA-Cnk2p resulted in cells with short flagella reminiscent of shf mutants. Conversely, knock-down of Cnk2p levels by RNAi induced a long-flagella phenotype. Further analysis of the short flagella phenotype of HA-Cnk2p suggested that an increase in the levels of Cnk2p induced more rapid flagellar disassembly. Similar to the role of Cnk2p in the regulation of flagellar length in Chlamydomonas, at least 4 NIMA-related kinases have been implicated in the regulation of ciliary length in Tetrahymena [50]. Overexpression of GFP-tagged Nrk1p resulted in a small decrease in the length of a subset of cilia. A more significant decrease in ciliary length was observed with GFP-Nrk2p, GFP-Nrk17p, and GFP-Nrk30p. Although single and double mutants of Nrk1p and Nrk2p had no discernable effect on ciliary length, a kinase-dead version of Nrk2p resulted in longer cilia. Taken together these results are consistent with a model for the continual assembly of flagella and that length is controlled by the regulated disassembly of these organelles.

5.3 Inositol 1,3,4,5,6-pentakiphosphate 2-kinase (Ipk1)

In mammalian systems, defects in the assembly and function of nodal cilia during development result in randomization of left-right (LR) asymmetry. A similar loss of LR asymmetry was observed in zebrafish when the levels of Ipk1 were decreased by the injection of an antisense morpholino oligionucleotide that prevents translation of ipk1 (an inositol kinase that phosphorylates inositol 1,3,4,5,6-pentakiphosphate to generate inositol hexakiphosphate) mRNA [51]. Although ciliary ultrastructure of the ipk1MO1 embryos was grossly normal, these cilia did not beat and were shorter than in wild-type embryos [52]. The co-injection of the wild-type Ipk1 mRNA with the antisense morpholino resulted in rescue of the motility defect. This rescue was not seen when the antisense morpholino was co-injected with a kinase-dead version of the Ipk1 mRNA [52]. These results suggest that the kinase activity of Ipk1 is required for normal functioning of cilia. GFP-tagged Ipk1 localizes to both centrosomes and basal bodies. Similar to the apparently normal structure of Ipk1MO1 cilia, there was no gross centrosomal defect observed in embryos injected with the Ipk1 antisense morpholino [52]. Taken together these results suggest a role for inositol signaling in the regulation of ciliary length and function in zebrafish embryos. Interestingly, lithium has also been reported to inhibit the activity of inositol monophosphatases thus effectively depleting the inositol pool in cells. In light of these results, it is tempting to speculate that the lithium-induced elongation and subsequent disassembly of flagella in Chlamydomonas occurs not only by inhibition of GSK3 but also by affecting inositol pools within the cell bodies.

5.4 ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein (LdARL-3A)

A role for the ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein, LdARL-3A, in the regulation of flagellar length in Leishmania comes from studies utilizing overexpression of enzymatically inactive forms of LdARL-3A [53, 54]. ARLs are small G proteins that are members of the ras superfamily and as such transit between a GDP and GTP bound form. Although ARLs are enzymatically inactive in the GDP bound state, the exchange of GDP for GTP results in enzymatic activation. Overexpression of a GTPase-deficient version of LdARL-3A in wild-type strains resulted in cells that assembled short flagella [53, 54]. Similar results were obtained when a GDP-blocked form of LdARL-3A was overexpressed [54]. Although the function of LdARL-3A is currently unknown, homologs in mammals have been shown to regulate the polymerization of tubulin [55]. Although further work is necessary to determine how LdARL-3A regulates flagellar length, one possible mechanism is through direct effects on tubulin.

5.5 Mitotic-Centromere-Associated Kinesin (MCAK)-like Kinesin 13 (LmjKIN1–2)

While the activity of kinesin II is required for anterograde IFT and thus for the building and maintenance of flagella, members of the kinesin 13 family, which depolymerize microtubules, have recently emerged as playing a role in the regulation of flagellar length. This was first demonstrated by the localization of GFP-tagged LmjKIN1–2 to flagella in Leishmania [56]. As flagella are dynamic organelles that are constantly undergoing assembly and disassembly at the tip, it is interesting that LmjKIN1-2 was enriched at both the apical and basal ends of flagella. As one might expect for a member of the kinesin 13 family, the overexpression of LmjKIN1–2 resulted in the assembly of short flagella [56]. To confirm that this short flagella phenotype was in fact due to the depolymerization of axonemal microtubules, the amino acids of the KLD domain (essential for depolymerization activity) were mutagenized to alanines. In contrast to the short flagella phenotype seen with wild-type LmjKIN1-1, cells overexpressing ΔKLD/AAAs assembled flagella that were longer than wild-type [56]. Consistent with these results, long flagella were also observed when LmjKIN1–2 levels were decreased by RNAi. These studies are the first to demonstrate that the direct regulation of the polymerization state of axonemal microtubules can influence flagellar length.

5.6 cALK

The Chlamydomonas aurora-like protein kinase (cALK) is essential for the regulated disassembly of flagella prior to mitosis or in response to environmental changes such as loss of calcium from the medium. Knockdown of cALK protein levels by RNAi resulted in the cells unable to excise their flagella [57]. In response to internal (cell cycle) or external (pH shock) cues, cALK undergoes phosphorylation. Subsequently, cells were examined under various conditions where flagella are either not assembled, such as in cells grown on agar plates, or flagellaless mutants and during regulated disassembly of flagella following gametic cell-cell fusion or removal of calcium from the medium. Under all of these conditions, cALK was phosphorylated [57]. This phosphorylation of cALK was inhibited by treatment of cells with the protein kinase inhibitor, staurosporine, which prevented flagellar excision by pH shock [57]. Taken together these results suggest that cALK and its phosphorylation are essential in the regulated disassembly of flagella.

During the regulated disassembly of flagella, disassembly of the axoneme is stimulated over its basal rate [58]. In addition, cells increase the amount of empty (i.e., devoid of anterograde cargo) IFT particles that enter the flagellum. This increase in IFT particles would allow for the efficient return of the disassembled flagellar components to the cell body, thus resulting in the rapid resorption of flagella. During the course of these studies, Pan et al., made the interesting observation that regulated disassembly of flagella is fundamentally different from enforcement of length. When calcium was removed from the medium of lf4 cells, cALK phosphorylation and the kinetics of flagellar shortening were similar to that observed for wild-type cells [58]. These results highlight the complexity of regulating the assembly state of flagella from maintaining flagella of appropriate length to inducing their rapid disassembly.

5.7 LF1

As described above, a mutation in the LF1 gene of Chlamydomonas results in cells that assemble flagella two to three times wild-type length. LF1p function is not necessary for flagellar assembly following cell division. When lf1 mutants are deflagellated, however, they can not re-assemble new flagella [59]. These results suggest that an as yet unidentified protein expressed during cell division can replace the requirement for LF1p in flagellar assembly. LF1p is a novel protein that is glycine-rich (21%), and contains no putative functional motifs [59]. Interestingly, the C-terminal half of LF1p is dispensable for its function. Transformants expressing only the N-terminal half of LF1p assemble flagella that are wild-type in length [59]. Surprising for a protein involved in the regulation of the assembly state of flagella, the LF1 transcript is not upregulated during flagellar assembly. As most if not all flagellar genes are upregulated during assembly of flagella [44], this result suggested that LF1p is not a component of flagella. In fact, little if any LF1p is present in flagella. Instead, HA-tagged LF1p was localized to punctate regions within the cell body [59].

5.8 LF3

Like lf1 mutants, hypomorphic alleles of LF3 assemble flagella that are abnormally long [42]. The flagella of null alleles of LF3 (lf3-5/ulf1/ulf3), however, are unequal in length and contain prominent bulges or swellings at the tips (Fig. 1; ulf1) [45]. Although the flagella of lf3–5 are short at the beginning of the light cycle, they steadily elongate to abnormal lengths during the day. These results suggest that in addition to the loss in length control, null alleles of LF3 have an additional assembly defect that slows down the rate of elongation. Moreover, the loss of flagellar equality suggests that there might be differences inherent between the two flagella. Ultrastructural analysis of lf3–5 revealed the presence of linear arrays of particles similar to IFT particles [45]. This accumulation of IFT particles was confirmed by the demonstration of significant increases in IFT motor proteins and particle proteins in the flagella of lf3–5 compared to wild-type. In contrast, there was little difference between the levels of axonemal proteins in lf3–5 and wild-type flagella. Although LF3p is a novel protein, analysis of its sequence suggests the presence of a putative leucine zipper motif, transmembrane domains, and a PEST sequence. The LF3 transcript is not upregulated during flagellar assembly and HA-tagged LF3p localizes to punctate regions within the cell body similar to those observed with LF1p [45]. Fractionation of LF3p from cell body extracts by sucrose density sedimentation revealed that LF3p co-sediments with LF1p at an 11S fraction [45]. The similar localization, synthetic phenotype in lf1 lf3 double mutants, and co-sedimentation of LF1p with LF3p suggests that these proteins might regulate flagellar length in part by the formation of an LF1p-LF3p protein complex.

5.9 LF2

LF2 encodes a cyclin-dependent protein kinase related kinase (CDK-related kinase) [46]. LF2p lacks the typical PSTAIRE motif (utilized by CDKs for binding their regulatory subunit – cyclin) and instead has a unique sequence, PDVVVRE. The closest homolog for LF2p is the CDK-related kinase rat PNQARLE whose function is unknown; however, it is expressed in testis where flagella assembly of sperm occurs [60]. Hypomorphic alleles of LF2 assemble long flagella [44]. In the complete absence of LF2 function, however, cells assemble flagella of unequal length [46]. Similar to LF1 and LF3, the transcript for LF2 is also not upregulated during flagellar assembly suggesting that LF2p is not a flagellar component. Much like LF1p and LF3p, LF2p localizes to punctate regions in the cell body and sediments with LF1p, and LF3p at an 11S fraction upon sucrose density sedimentation [46]. Consistent with a genetic interaction between these LF genes, the LF2 transcript is significantly decreased in both lf3 null mutants and double mutants containing a hypomorphic allele of lf3 or lf2 [46]. Similarly, the LF3 transcript is decreased both in lf2 null mutants or double mutants generated from lf3 or lf2 [45]. An interaction between LF2p, LF1p, and LF3p was also demonstrated by yeast two hybrid analyses [46]. Although the kinase activity of LF2p does not appear to be regulated by a cyclin, it is intriguing to consider that LF1p and/or LF3p could serve as a binding partner to regulate the enzyme activity of LF2p.

5.10 LF4 and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases

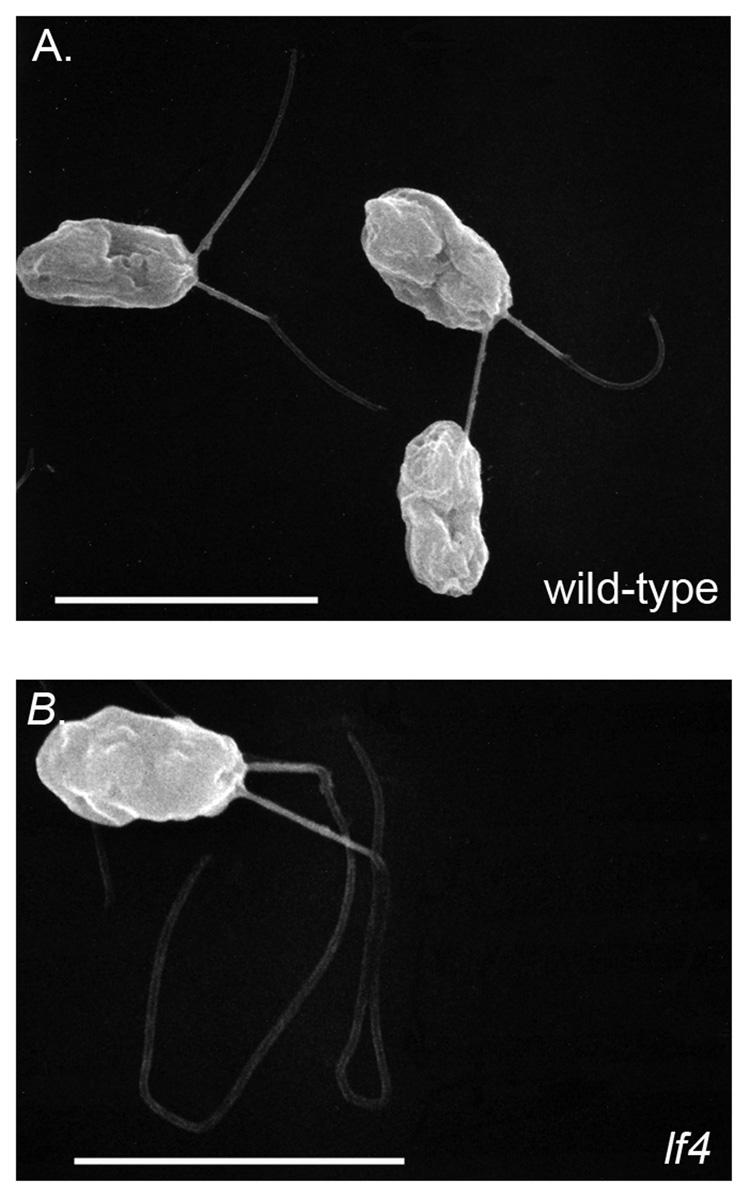

All alleles of lf4 were generated by insertional mutagenesis and are accompanied by deletions and other sequence re-arrangements within the LF4 gene [60]. In contrast to the null alleles of lf2 and lf3, which assemble flagella that are unequal in length, all lf4 alleles assemble abnormally long flagella of equal length (Fig. 1, compare ulf1 with lf4; Fig. 2). The excessive assembly of flagella in the absence of a gene product for LF4 suggests that LF4p functions either to stop flagellar assembly or alternatively to induce resorption once flagellar growth exceeds its functional limits. In contrast to LF1, LF2, and LF3, the transcript for LF4 is upregulated during flagellar assembly suggesting that LF4p is a component of flagella [61]. Examination of flagella isolated from either wild-type cells or the lf4 mutant revealed a single polypeptide present in flagella of wild-type cells and missing from the lf4 flagella. These results confirm that lf4 is a null mutation and that the wild-type protein is a flagellar component.

Figure 2. Scanning electron microscopy of wild-type and lf4 mutant.

Vegetatively growing cells were fixed and prepared for scanning electron microscopy using conventional methods. The flagella assembled by the lf4 mutant (b) are approximately twice the length of the wild-type cells (a). Bar = 10 µm.

LF4 encodes a novel mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase that belongs to the ERK superfamily of MAP kinases. The closest homolog for LF4p is MOK (MAPK/MAK/MRK overlapping kinase) a kinase of unknown function [62]. More support for the role of MAP kinases in the regulation of flagellar assembly comes from studies utilizing Leishmania. Mutants that were null for a MAP kinase kinase (LmxMKK) assembled abnormally short flagella [63]. Whether the short flagella phenotype of the LmxMKK null cells reflects a direct role for LmxMKK on the enforcement of length is not clear. It is possible that the length defect in LmxMKK null cells is a consequence of the inability to assemble a normal flagellum as evidenced by the multiple structural defects observed in these short flagella. Subsequent studies identified a MAP kinase, LmxMPK3, that when deleted generated a flagellar phenotype similar to that seen with LmxMKK (i.e., short flagella). Moreover, LmxMPK3 was a substrate for phosphorylation by LmxMKK both in vitro and in vivo. While LmxMPK3 was identified as a phosphoprotein purified from wild-type cells, it was not detectable in purified phosphoproteins from LmxMKK null cells [64]. Finally, a second MAP kinase, LmxMPK9, has been identified that when deleted results in cells that assemble flagella 2 µm longer than wild-type. Interestingly, overexpression of wild-type LmxMPK9 results in the assembly of short flagella. These observations suggest that LmxMPK9 could affect flagellar length in a manner similar to LF4, i.e., by inducing resorption or disassembly of flagella (65).

6. Models for length control

A number of models have been proposed to explain the mechanisms used to control flagellar length. The simplest of these models is the limiting or quantal synthesis model, which proposes that one or more key components of the flagella is synthesized in a defined, limiting amount. Flagellar length therefore, would be directly proportional to the quantity of protein synthesized. Although there is evidence for the limited synthesis of a key axonemal component in sea urchins (i.e., tetkin A) [66], the presence of a pool of flagellar precursors and the demonstration that components of this pool can be readily used to generate flagella in the absence of protein synthesis argue against this model in Chlamydomonas [8].

Another model suggests that some property inherent to the flagellum itself regulates the length of this organelle. This “self-limiting” model is based on the observation that flagellar assembly occurs at the distal tip of the flagellum and with deceleratory kinetics [67]. According to this model as the flagellum grows flagellar precursors must diffuse over an ever increasing distance. Thus the rate of flagellar elongation would be directly proportional to the length of the flagellum. [67]. The discovery of IFT and its essential role in the assembly and maintenance of flagella led to the incorporation of IFT into these models. In particular the observation that the number of IFT particles in a flagellum is independent of the length of the flagellum led to the development of a balance-point model [10]. In this model, the length of flagella is regulated by the attainment of a state in which flagellar assembly by IFT is balanced with disassembly [10, 68]. The deceleratory kinetics of flagellar regeneration after deflagellation is consistent with these self-limiting models. In addition, the self-limiting model is consistent with the effect observed when a cell loses one flagellum (i.e., the long-zero response). It is likely, therefore, that the balance-point model proposed by Wallace and Rosenbaum [10] provides an essential foundation for a model of how cells regulate the length of flagella. Still unexplained, however, is the observation that rapid distal elongation of the flagella can occur, for example, after chemically-induced shortening of wild-type flagella or elongation of shf flagella after mating with wild-type cells [41, 42, 44]. Moreover, an important and often overlooked observation from studies using lf/wt dikaryons is that only the lf flagella undergo appreciable changes in length. There is no discernable change in the wild-type flagella. This observation suggests that length is not regulated by averaging the distribution of available flagellar components into available flagella. If this was the case, then wild-type flagella should have elongated, which was not observed.

If regulation of flagellar length is not inherent to the process of flagellar elongation, then perhaps some component of the flagellar apparatus mediates this function. One obvious candidate would be the basal bodies, which could act as the entry site for transport and assembly into the flagellum. In fact, the transitional fibers of the basal body have been identified as a docking site for IFT particles prior to entry into the flagellum [69]. Moreover, one could imagine that the physical interaction between basal bodies (mediated by striated fibers) plays an important role in the communication between flagellar pairs allowing detection of flagellar inequality [6, 7].

The increasing number of proteins that can regulate flagellar length and are components of signal transduction pathways, however, suggests that protein modification by signaling ultimately regulates the assembly state of flagella. This regulation could occur by the direct modification of structural components of flagella. Alternatively, regulation of flagellar length could occur by modifications to one or more IFT particle proteins that would affect cargo loading or the number of IFT particles entering or exiting a flagellum. It is likely that these possible mechanisms for the regulation of flagellar length are not mutually exclusive. Instead, we propose that there are multiple mechanisms involved in flagellar length regulation.

Finally, in order for signaling pathways to regulate flagellar length, these pathways must be activated. One possibility is that the ultimate initiator in the regulation of flagellar length could be an activity inherent within the flagellum. For example, electrophysiological studies of flagellar currents in Chlamydomonas have identified calcium channels that appear to be distributed along the length of the flagella [70]. Perhaps basal bodies in conjunction with calcium-binding proteins are able to detect differences in intraflagellar calcium levels and regulate lengthening or shortening of the flagellum to minimize any discrepancies. Further examination will be required to determine whether any of these possibilities are correct. It is likely, however, that regulation of flagellar length will involve not only regulation of flagellar assembly and disassembly by IFT (i.e., the balance-point model) but also the regulation of multiple signal transduction pathways that direct the assembly or disassembly of the flagellum.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Dorothy Turetsky (OSU-CHS) and Pete Lefebvre (U MN) for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yan M, Rayapuram N, Subramani S. The control of peroxisome number and size during division and proliferation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewin RA. Mutants of C. Moewussii with impaired motility. J Gen Microbiol. 1954;11:358–363. doi: 10.1099/00221287-11-3-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luck D, Piperno G, Ramanis Z, Huang B. Flagellar mutants of Chlamydomonas: Studies of radial spoke-defective strains by dikaryon and revertant analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:3456–3460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang B, Piperno G, Ramanis Z, Luck DJL. Radial spokes of Chlamydomonas flagella: genetic analysis of assembly and function. J Cell Biol. 1981;88:80–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.88.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutcher SK. Flagellar assembly in two hundred and fifty easy-to-follow steps. Trend Genet. 1995;11:398–304. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright RL, Chojnacki B, Jarvik JW. Abnormal basal-body number, location, and orientation in a striated fiber-defective mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:1697–1707. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.6.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright RL, Salisbury J, Jarvik JL. A nucleus-basal body connector in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii that may function in basal body localization or segregation. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1903–1912. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.5.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenbaum JL, Moulder JE, Ringo DL. Flagellar elongation and shortening in Chlamydomonas. The use of cycloheximide and colchicine to study the synthesis and assembly of flagellar proteins. J Cell Biol. 1969;41:600–619. doi: 10.1083/jcb.41.2.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson KA, Rosenbaum JL. Polarity of flagellar assembly in Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1605–1611. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall WF, Rosenbaum JL. Intraflagellar transport balances continuous turnover of outer doublet microtubules: implications for flagellar length control. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:405–414. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozminski KG, Johnson KA, Forscher P, Rosenbaum JL. A motility in the eukaryotic flagellum unrelated to flagellar beating. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5519–5523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piperno G, Mead K. Transport of a novel complex in the cytoplasmic matrix of Chlamydomonas flagella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4457–4462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Col DG, Diener DR, Himelblau AL, Beech PL, Fuster JC, Rosenbaum JL. Chlamydomonas Kinesin-II-dependent intraflagellar transport (IFT): IFT particles contain proteins required for ciliary assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans sensory neurons. J Cell Biol. 1998;141 doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.993. 993-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piperno G, Siuda E, Henderson S, Segil M, Vaananen H, Sassaroli M. Distinct mutants of retrograde intraflagellar transport (IFT) share similar morphological and molecular defects. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1591–1601. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozminski KG, Beech PL, Rosenbaum JL. The Chlamydomonas kinesin-like protein FLA10 is involved in motility associated with the flagellar membrane. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1517–1527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pazour GJ, Dickert BL, Witman GB. The DHC1b (DHHC2) isoform of cytoplasmic dynein is required for flagellar assembly. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:473–481. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porter ME, Bower R, Knott JA, Byrd P, Dentler W. Cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain 1b is required for flagellar assembly in Chlamydomonas. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:693–712. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Signor D, Wedaman KP, Orozco JT, Dwyer ND, Bargmann I, Rose LS, Scholey JM. Role of a class DHC1b dynein in retrograde transport of IFT motors and IFT raft particles along cilia, but not dendrites, in chemosensory neurons of living Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:519–530. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piperno G, Mead K, Henderson S. Inner dynein arms but not outer dynein arms require the activity of kinesin homologue protein KHP1FLA10 to reach the distal part of flagella in Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:371–379. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin H, Diener DR, Geimer S, Cole DG, Rosenbaum JL. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) cargo: IFT transports flagellar precursors to the tip and turnover products to the cell body. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:255–266. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auclair W, Siegel BW. Cilia regeneration in the sea urchin embryo: Evidence for a pool of ciliary proteins. Science. 1966;154:913–915. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3751.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rannestad J. The regeneration of cilia in partially deciliated Tetrahymena. J Cell Biol. 1974;93:615–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.63.3.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefebvre PA, Rosenbaum JL. Regulation of the synthesis and assembly of ciliary and flagellar proteins during regeneration. Ann Rev Cell Biol. 1986;2:517–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.02.110186.002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solter KM, Gibor A. The relationship between tonicity and flagellar length. Nature. 1978;275:651–652. doi: 10.1038/275651a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telser A. The inhibition of flagellar regeneration in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by inhalational anesthetic halothane. Exp Cell Res. 1977;107:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(77)90406-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snell WJ, Buchanan M, Clausell A. Lidocaine reversibly inhibits fertilization in Chlamydomonas: a possible role for calcium in sexual signaling. J Cell Biol. 1982;94:607–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.3.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dentler WL, Adams C. Flagellar microtubular dynamics in Chlamydomonas: Cytochalasin D induces periods of microtubule shortening and elongation; and colchicine induces disassembly of the distal but not proximal, half of the flagellum. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:1289–1298. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.6.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefebvre PA, Silflow CD, Wieben ED, Rosenbaum JL. Increased levels of mRNAs for tubulin and other flagellar proteins after amputation or shortening of Chlamydomonas flagella. Cell. 1980;20:469–477. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90633-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartfiel G, Amrhein N. The action of methylxanthines on motility and growth of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and other flagellated algae. Is cyclic AMP involved? Biolchem Physiol Pflanzen. 1976;169:531–556. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuxhorn J, Daise T, Dentler WL. Regulation of flagellar length in Chlamydomonas. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1998;40:133–146. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)40:2<133::AID-CM3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pasquale SM, Goodenough UW. Cyclic AMP functions as a primary sexual signal in gametes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2279–2292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Low SH, Roche PA, Anderson HA, van Ijzendoorn SCD, Zhang M, Mostov KE, Weimbs T. Targeting of SNAP-23 and SNAP-25 in polarized epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3422–3430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura S, Takino H, Kojima MK. Effect of lithium on flagellar length in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Cell Struct Funct. 1987;12:369–374. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson NF, Lefebvre PA. Regulation of flagellar assembly by glycogen synthase kinase 3 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:1307–1319. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.5.1307-1319.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lefebvre PA, Nordstrom SA, Moulder JE, Rosenbaum JL. Flagellar belongation and shortening in Chlamydomonas IV. Effects of flagellar detachment, regeneration, and resorption on the induction of flagellar protein synthesis. J Cell Biol. 1978;78:8–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.78.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quader H, Cherniack J, Filner P. Participation of calcium in flagellar shortening and regeneration in Chlamydomonas reinhardii. Exp Cell Res. 1978;113:295–301. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(78)90369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McVittie A. Flagellum mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Gen Microbiol. 1972;71:525–540. doi: 10.1099/00221287-71-3-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarvik JW. Size-control in the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii flagellum. J Protozool. 1988;35:570–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1988.tb04154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lefebvre PA, Asleson CM, Tam LW. Control of flagellar length in Chlamydomonas. Seminars Dev Biol. 1995;6:317–323. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jarvik JW, Reinhardt FD, Kuchka MR, Adler SA. Altered flagellar size control in shf-1 short-flagella mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Protozool. 1984;31:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuchka MR, Jarvik JW. Short-flagella mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics. 1987;115:685–691. doi: 10.1093/genetics/115.4.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barsel S-E, Wexler DE, Lefebvre PA. Genetic analysis of long flagella mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Genetics. 1988;118:637–648. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.4.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tam L-W, Lefebvre PA. Cloning of flagellar genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by DNA insertional mutagenesis. Genetics. 1993;135:375–384. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asleson CM, Lefebvre PA. Genetic analysis of flagellar length control in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: A new long-flagella locus and extragenic suppressor mutations. Genetics. 1998;148:693–702. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.2.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tam L-W, Dentler WL, Lefebvre PA. Defective flagellar assembly and length regulation in LF3 null mutants in Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:597–607. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tam L-W, Wilson NF, Lefebvre PA. LF2 encodes a CDK-related kinase that regulates flagellar length and assembly in Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:819–829. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lefebvre PA, Nordstrom SA, Moulder JE, Rosenbaum JL. Flagellar elongation and shortening in Chlamydomonas IV. Effects of flagellar detachment, regeneration, and resorption on the induction of flagellar otein synthesis. J Cell Biol. 1978;78:8–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.78.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thoma CR, Frew IJ, Hoerner CR, Montani M, Moch H, Krek W. pVHL and GSK3β are components of a primary cilium-maintenance signalling network. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:588–595. doi: 10.1038/ncb1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradley BA, Quarmby LM. A NIMA-related kinase, Cnk2p, regulates both flagellar length and cell size in Chlamydmonas. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3317–3326. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wloga D, Camba A, Rogowski K, Manning G, Jerka-Dziadosz M, Gaertig J. Members of the NIMA-related kinase family promote disassembly of cilia by multiple mechanisms. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2799–2810. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarmah B, Latimer AJ, Appel B, Wente SR. Inositol polyphosphates regulate zebrafish left-right asymmetry. Dev Cell. 2005;9:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarmah B, Winfrey VP, Olson GE, Appel B, Wente SR. A role for the inositol kinase Ipk1 in ciliary beating and length maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19843–19848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706934104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cuvillier A, Redon F, Antonine J-C, Chardin P, DeVos T, Merlin G. LdARL-3A, a Leishmania promastigote-specific ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein, is essential for flagellum integrity. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2065–2074. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.11.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahin A, Espiau B, Marchand C, Merlin G. Flagellar length depends on LdARL-3A GTP/GDP unaltered cycling in Leishmania amazonensis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;157:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou C, Cunningham L, Marcus AI, Li Y, Kahn RA. Arl2 and Arl3 regulate different microtubule-dependent processes. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2476–2487. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blaineau C, Tessier M, Dubessay P, Tasse L, Crobu L, Pages M, Bastien P. A novel microtubule-depolymerizing kinesin involved in length control of a eukaryotic flagellum. Curr Biol. 2007;17:778–782. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pan J, Wang Q, Snell WJ. An aurora kinase is essential for flagellar disassembly in Chlamydomonas. Dev Cell. 2004;6:445–451. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pan J, Snell WJ. Chlamydomonas shortens its flagella by activating axonemal disassembly, stimulating IFT particle trafficking and blocking anterograde cargo loading. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nguyen RL, Tam L-W, Lefebvre PA. The LF1 gene of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii encodes a novel protein required for flagellar length control. Genetics. 2005;169:1415–1424. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wohlbold L, Larochelle S, Liao JC, Livshits G, Singer J, Shokat KM, Fisher RP. The cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) family member PNQALRE/CCRK supports cell proliferation but has no intrinsic CDK-activating kinase (CAK) activity. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:546–554. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.5.2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berman SA, Wilson NF, Haas NA, Lefebvre PA. A novel MAP kinase regulates flagellar length in Chlamydomonas. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1145–1149. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miyata Y, Akashi M, Nishida E. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel member of the MAP kinase superfamily. Genes Cells. 1999;4:299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wiese M, Kuhn D, Grunfelder CG. Protein kinase involved in flagellar-length control. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:769–777. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.4.769-777.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Erdmann J, Scholz A, Melzer IM, Schmetz C, Wiese M. Interacting protein kinases involved in the regulation of flagellar length. Mol Biol Celll. 2006;17:2035–2045. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bengs F, Scholz A, Kuhn D, Wiese M. LmxMPK9, a mitogen-activated protein kinase homologue affects flagellar legnth in Leishmania mexicana. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1606–1615. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stephens RE. Quantal tektin synthesis and ciliary length in sea-urchin embryos. J Cell Sci. 1989;92:403–413. doi: 10.1242/jcs.92.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jarvik JW. Size-control in the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii flagellum. J Protozool. 1988;35:570–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1988.tb04154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marshall WF, Qin H, Brenni MR, Rosenbaum JL. Flagellar length control system: Testing a simple model based on intraflagellar transport and turnover. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:270–278. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deane JA, Cole DG, Seeley ES, Diener DR, Rosenbaum JL. Localization of intraflagellar transport protein IFT52 identifies basal body transitional fibers as the docking site for IFT particles. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1586–1590. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beck C, Uhl R. On the localization of voltage-sensitive calcium channels in the flagella of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:1119–1125. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.5.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]