Abstract

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to determine the relationship between type of eating occasion based on need state segments experienced by 200 midlife women (46 ± 6 years) and food group, nutrient, and energy intake. Women completed an Eating Occasion Questionnaire for 3 eating occasions over a 3-day period for which they maintained diet records. Cluster analysis segmented 559 eating occasions into six need states. Energy, total fat, and cholesterol consumption per occasion were highest in “routine family meal” occasions of which more than 60% were dinner and eaten at home with their children. The percentage of eating occasions in which fruits/vegetables were eaten was also highest in “routine family meal,” followed by “healthy regimen.” More than half of “indulgent escape” eating occasions occurred away from home and about one-third were experienced as a snack. Saturated fat and sweets intakes were the highest in the “indulgent escapes” occasions. Eating occasions experienced by women according to needs surrounding the occasion should be considered when developing tailored interventions to improve intake.

Keywords: Eating occasions, Need State, Food group, Midlife women, Segmentation, Energy and fat intake, Situational context

Introduction

This report describes 6 types of eating occasions experienced by midlife women according to needs surrounding the occasion. Situational context with regard to need state may contribute to differences in food group, nutrient and energy intake across type of eating occasion.

Women tend to experience a gradual increase in weight with age (Field, Willett, Lissner, & Colditz, 2007; Gonzalez, White, Kristal, & Littman, 2006; Sternfeld et al., 2004). For women in midlife, an inverse relationship exists between total energy expenditure and age (Roberts & Dallal, 2005; Tooze et al., 2007) which may help to explain age-related increases in weight. Since weight gain has negative effects on risk for chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and prehypertension (Sullivan, Wyatt, Marrato, Hill, & Ghushchyan, 2005; Yang et al., 2007), eating and exercise habits need to be modified to prevent weight gain with age.

Need states of individuals have been defined by market researchers as inner and outer influences (or triggers) that impact food purchase or consumption decisions (Riley & Leith, 1998). In this study, need states comprise the eating occasion and all internal and external drivers interpreted by the individual as perceived needs surrounding the eating occasion. Therefore need states may be based on rational and/or emotional needs underlying food choice within specific situations. Previous studies have examined perceptions of specific needs and their relationship to eating behavior. For example, Gilhooly et al. (2007) identified the need for overweight women to satisfy cravings with foods with high energy density and fat content, and low protein and fiber contents. For many women, the need to provide food for families was impacted by limited availability of time and resulted in the use of daily time management strategies such as planning and coordination with implications for food choice (Jabs et al., 2007). In an experimental situation, Pliner and Mann (2004) showed that women responded to a need to conform to social norms by eating quantities of food according to what they thought others had consumed. Impulsivity, which can be defined as the tendency to think, control and plan insufficiently, was linked to greater food intake in women (Guerrieri et al., 2007). In cross-sectional studies, the need to satisfy hunger with palatable foods contributed to greater energy intake in women (Green & Blundell, 1996) and eating frequency was positively correlated with intakes of total carbohydrate and sugars and total energy intake (Drummond, Crombie, Cursiter, & Kirk, 1998).

Procedures involving segmentation of audiences have been applied to health communication, predictiveness of health behaviors or weight status, and dietary patterns (Albrecht & Bryant, 1996; Contento et al., 1993; Davison & Birch, 2002; Staten, Birnbaum, Jobe, & Elder, 2006). While these procedures have not been applied previously to need states regarding eating occasions, they may be a useful tool to identify and describe underlying needs based on distinct eating occasions affecting food choice among midlife women.

The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between the types of eating occasions based on need state segments experienced by midlife women and food group, nutrient, and energy intake. Identifying these relationships may improve our ability to create effective intervention strategies to address eating behaviors and obesity prevention among midlife women by targeting specific needs within eating occasions.

Methods

Study design

The data reported in this study were part of a larger cross-sectional study conducted in two phases where attitude data about food and anthropometric data were collected from women as well as information about eating occasions. Data reported here pertain to eating occasions only.

Qualitative data were collected in the first phase to develop a need state questionnaire (Eating Occasion Questionnaire) for administration in the second phase. Initially, qualitative data were collected using the think aloud method (Ericsson & Simon, 1993) from 12 women in their home while they prepared a meal or in a restaurant while they ordered and ate a meal. Results were used to develop focus group questions for a series of 7 focus group interviews (n = 34 women) conducted to provide data to develop the Eating Occasion Questionnaire (Vue, Degeneffe, & Reicks, In press). Focus group findings indicated that women experienced need states dominated by lower order or functional needs such as coping with stress, balancing intake across occasions, meeting external demands of time and effort, and maintaining a routine. Need states with a higher level of emotional involvement included food as a means for reinforcing family identity, social expression and celebration. The questionnaire was pre-tested, revised and used in the second phase of the study along with collection of 3-day diet records. The study protocol was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board utilizing informed consent procedures.

Sample

Respondents learned about the study through advertisements, flyers and notices distributed through newsletters, campus bulletin boards, and city and local newspapers. Women were screened according to inclusion criteria via the telephone prior to scheduling outpatient visits. Inclusion criteria included being a healthy volunteer, a woman between the ages of 35 and 55 years, and not following a medically prescribed or vegan diet. Exclusion criteria included having existing chronic medical conditions (cancer, stroke, diabetes, heart disease, chronic respiratory disease, renal disease), and being pregnant or breastfeeding.

Data collection

Dietary intake (3-day diet records)

Women initially met with a researcher at a convenient location (home, community center, or General Clinical Research Center (GCRC), University of Minnesota). They were assigned three days for which to complete food records so that records were evenly distributed across all days of the week and months of the year. Women were given a carry-all bag containing a 3-ring notebook including instructions, record forms and Eating Occasion Questionnaires organized by day, a digital camera, laminated placemat, and microcassette recorder. They were asked to carry the bag with them throughout the 3-day recording period. For each eating occasion, women were asked to first take a digital photograph immediately before and after eating using the laminated placemat to center the food/beverage items. After taking the photographs, women were asked to complete the food record as well as verbally record answers to a series of questions into a microcassette recorder. Questions were provided on a small laminated cue card regarding each food consumed (type, source, brand, quantity (fl. oz, weight, cups, etc, and dimensions), how it was prepared, and if all food in the photograph was consumed during the eating occasion). Women were also asked to record the time, day and location of each eating occasion. At a second meeting with a researcher at the GCRC, the woman returned the equipment, digital images, and audiotape. A registered dietitian examined the photographs and listened to the tape recordings and followed up with clarifying questions as needed to maximize accuracy of the food record. Nutritionist 5 software (First DataBank, San Bruno, CA) was used by research assistants to calculate total energy and nutrient intake. A registered dietitian checked 10% of the diet records for accuracy.

Foods consumed during the 3-day period were classified into nine food groups (US FDA & DHHS, 2002); fruits/vegetables, dairy/calcium-rich foods, fast food, meal-type convenience foods, non-meal-type convenience foods, supplement/meal replacements, carbonated soft drinks, dairy sweets, and non-dairy sweets. Fruits/vegetables were grouped according to those listed in the fruits and vegetables groups in MyPyramid (USDA, 2005). This group included raw, frozen, cut, canned, or dried fruits/vegetables, mixed, boiled, or drained vegetables, 100% fruit juice, and mixture such as canned spaghetti tomato sauce and beef stew. Dairy/calcium-rich foods included milk, cheese, yogurt, and calcium fortified orange juice because these foods represented the main sources of dietary calcium for women (Gao, Wilde, Lichenstein & Tucker, 2006). Fast food was food purchased at fast food restaurants regardless of where it was consumed. Commercially packaged foods with minimum preparation needed at home and frozen dinners were considered convenience foods according to meal-type or non-meal-type. Examples of meal-type convenience foods included frozen pizza, mashed potato mix, and canned chicken gravy. Those of non-meal-type were hot cocoa mix and lemonade prepared from frozen concentrate. Foods in the supplements/meal replacement group included diet bars/powders/drinks and meal supplements. Dairy sweets included ice cream, frozen yogurt, and yogurt, while non-dairy sweets were cakes, pastries, tortes, cookies, gelatin, puddings, and frozen cakes. Some foods were classified into more than two groups and their intake was counted more than twice. For example, yogurt purchased at a fast food restaurant was counted three times as dairy/calcium-rich food, fast food, and dairy sweets.

Eating Occasion Questionnaire

Women were asked to complete an Eating Occasion Questionnaire for one eating occasion each day of the 3-day period for which they were keeping food records immediately after recording their food/beverage intake. The occasions were assigned to balance occasions across breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks and days of the week across all women. Women were asked to rate their agreement with 129 statements about need states using Likert-style 6 point strongly disagree-strongly agree scales. The statements were phrases based on several dimensions such as convenience, taste, health, comfort, etc. which completed the prefaces “I wanted to…” (needs) and “I wanted something that…” (benefits). Sample needs statements included: “control/limit my calorie intake,” “do other things while eating,” or “satisfy hunger”. Sample benefits statements were: “has fiber,” “tastes fresh,” or “is really indulgent.” Questions about situational context involving the presence of others, who prepared the food, preparation and eating times, and activities engaged in during the occasion were included in the Eating Occasion Questionnaire. The questionnaire also asked respondent to rate their level of satisfaction (1=very dissatisfied and 6=very satisfied) with the food consumed in the occasion based on several dimensions including overall satisfaction, taste, ease and amount of time required for acquiring, planning, preparation, eating, and clean-up, healthfulness, presence of beneficial nutrients, avoidance of ingredients that were bad for them, appeal to others present, price, satisfaction of hunger, and comfort.

Data analysis

Common variables used in cluster detection algorithms for consumer market segmentation include demographic, product usage, and attitudinal information. In this analysis, the variables were responses to need statements from women regarding needs surrounding eating occasions. It is desirable to select variables that have the potential to be useful both analytically and in the interpretation of resulting clusters, and also to be limited in number to facilitate the computation. Therefore, principal components analysis (PCA) was used to reduce the large number of original need statements (n=129) in the Eating Occasion Questionnaire to a smaller subset (n=90) for use as variables in the cluster analysis. The principal component analysis extracted broad components according to various dimensions such as the need to address health, convenience, and concern about price and portability, and to nurture, reward oneself, enjoy food, and maintain tradition and weight (Table 1). Components with an eigenvalue > 1 were retained (Kaiser & Caffrey, 1965). Internal consistency reliability of each component was assessed by determining Cronbach’s α coefficients (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Need statements (n=90) belonging to nine components having a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.70 or above were identified as the variables that were used in the cluster analysis.

Table 1.

Nine components according to needs resulting from principal components analysis

| Need statements by component for a total of 559 eating occasions1, 2 | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| Address health (17 items, α=.92) | |

| Is healthy to eat | 0.79 |

| Provides specific vitamins/minerals/nutrients | 0.75 |

| Eat responsibly | 0.74 |

| Nurture family (14 items, α=.94) | |

| Feel appreciated by others/family | 0.81 |

| Make children happy | 0.79 |

| Show my love for others | 0.77 |

| Reward/indulge (15 items, α=.88) | |

| Have a brief escape from the day | 0.74 |

| Reward myself | 0.65 |

| Feel better – less sad/stressed/angry | 0.63 |

| Enjoy taste (9 items, α=0.89) | |

| Is really flavorful | 0.76 |

| Really tastes great | 0.75 |

| Looks appetizing | 0.69 |

| Address need for convenience (12 items, α=.88) | |

| Minimize preparation effort | 0.79 |

| Not have to think/put forth effort | 0.70 |

| Is not time consuming | 0.70 |

| Address price concern (6 items, α=.86) | |

| Be thrifty/frugal | 0.85 |

| Save money | 0.84 |

| Stay on a budget | 0.77 |

| Maintain tradition (6 items, α=.83) | |

| Reconnect with the past | 0.61 |

| Maintain a habit/tradition | 0.61 |

| Reminds me of the past | 0.61 |

| Have portable food/beverage (5 items, α=.76) | |

| Is portable | 0.74 |

| Can be eaten with hands | 0.71 |

| Take food along with me to other places | 0.66 |

| Maintain weight (6 items, α=.79) | |

| Use willpower to keep from overeating | 0.70 |

| Control/limit my calorie intake | 0.65 |

| Stick to a diet | 0.65 |

A total of 90 need statements were grouped into 9 components, only 3 need statements are shown for each component according to ranking by factor loading.

Statements not italicized represent needs (I wanted to…), while statements in italics represent needs expressed as benefits from eating (I wanted something that…).

Each woman (n=200) completed one Eating Occasion Questionnaire for one meal/snack per day for a three day period for a total of 600 eating occasions. Data preparation steps included isolating and removing 41 occasions with excessive constant ratings on the needs statements (≥ 15 of the same consecutive responses) resulting in data from 559 eating occasions for use in the cluster analysis. Although all need statement variables were measured on the same Likert style 6 point scale, all variables were standardized to mean zero and standard deviation (SD) one (SAS PROC STANDARD) to avoid having variables with larger variances exert greater influence in calculating the clusters.

The FASTCLUS procedure in SAS using the nonhierarchical k-means method for clustering was used to perform the cluster analysis on the standardized data (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). The procedure calculated Euclidean-based distances equal to the square root of the sum of squared values for all variables. The ‘maxcluster=’ option in the FASTCLUS procedure was used to try several values (ranging from 3 to 8) for maximum clusters. Table 2 shows cluster summary statistics for the 6 cluster solution selected for use in this study. The root mean square (RMS) SD provided a measure of the average distance between each member of the cluster. The distance to the nearest cluster values indicated a reasonable separation between cluster centroids. The distance ratios for each cluster (distance to the nearest cluster/RMS SD) indicated that the 6 cluster solution was comprised of well-separated clusters comprised of homogeneous members.

Table 2.

Summary statistics for 6 cluster solution

| 6 Cluster solution | Frequency (Number of occasions) | RMS SD1 | Distance to the nearest cluster2 | Distance ratio3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 160 | 0.85 | 4.8 | 5.7 |

| 2 | 46 | 0.92 | 7.3 | 8.0 |

| 3 | 114 | 0.84 | 5.9 | 7.0 |

| 4 | 116 | 0.87 | 4.8 | 5.6 |

| 5 | 60 | 0.91 | 6.4 | 7.0 |

| 6 | 63 | 0.94 | 6.3 | 6.7 |

RMS = root mean square, SD = standard deviation = average distance between each member of the cluster

Measure of the separation between cluster centroids (mean and SD)

Distance to the nearest cluster/RMS SD

The 6 cluster solution contained a number of well-populated clusters which were well-separated in terms of key need statement variables. Table 3 provides an example of key need statement variables identified for two need segments based on examination of the centroid means of each need statement variable for each cluster; the same summary was completed for the remaining 4 need segments (data not shown). Since the major categorizing influences were needs and benefits within the distinct clusters of eating occasions, representative labels were based on researchers’ interpretation of need profiles. Canonical Discriminant Analysis in SAS (PROC DISCRIM) was used to check the validity of the choice of the 6 cluster solution for the need states segmentation.

Table 3.

Need statement summary for two example segments

| Need/Benefit Statements1 Defining Need State | Mean for Need State Segment | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Routine Family Meal (n = 60 occasions or 11% of total occasions) | ||

| Statements describing need state: | ||

| Serve others what is expected | 1.54 | 1.32 |

| Feel appreciated by others/family | 1.43 | 1.00 |

| Create/maintain a family tradition | 1.42 | 1.12 |

| Show my love for others | 1.41 | 1.08 |

| Connect with others/family | 1.34 | 0.77 |

| Have a pleasant meal with others | 1.23 | 0.72 |

| Everyone will eat without complaints | 1.21 | 0.98 |

| Creates family ties | 1.20 | 1.19 |

| Is a favorite with someone in the family | 0.92 | 0.84 |

| Statements not describing need state: | ||

| Have some personal time alone | −0.55 | 0.31 |

| Have a brief escape from the day | −0.65 | 0.60 |

| Indulgent Escape (n = 63 occasions or 11% of total occasions) | ||

| Statements describing need state: | ||

| Is really indulgent | 1.25 | 0.84 |

| Treat myself | 1.12 | 0.84 |

| Have a brief escape from the day | 0.86 | 0.85 |

| Is fun to eat | 0.82 | 0.57 |

| Statements not describing need state: | ||

| Stick to a diet | −0.66 | 0.47 |

| Is low in calories | −0.72 | 0.56 |

| Is low in fat/cholesterol | −0.77 | 0.70 |

| Provides specific vitamins / minerals / nutrients | −0.81 | 0.75 |

| Has fiber | −0.83 | 0.62 |

Statements not italicized represent needs (I wanted to…), while statements in italics

represent needs expressed as benefits from eating (I wanted something that…).

Associations between need states segments and categorical variables were examined by Pearson’s chi-square test. Since the expected frequencies in some cells of the crosstabulations were less than 5, we carried out exact tests that have high reliability, regardless of sample size, distribution, or large numbers of cells with low frequency (or zero). First, overall associations between six need states segments and a categorical variable were examined by using a 6 × X table. To identify which proportions were significantly different, 15 separate 2 × 2 crosstabulations were done between all the possible combinations of six need states segments. The significance level of these post-hoc chi-square tests was adjusted by dividing 0.05 by 15 and set at P < 0.003. Energy and fat intakes per eating occasion were compared between need states segments by Mann-Whitney’s U test with Bonferroni’s inequality. Statistical Analysis Software (SAS version 9.1, Cary, NC) was used to conduct the principal components and cluster analyses. All other analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 14.0J, Chicago, IL).

Results

A total of 213 women were enrolled in the study. Nine women did not complete data collection components due to illness or lack of time. Data from 4 women with constant ratings for a significant portion of another unrelated set of questions (≥ 15 of the same consecutive responses) were also excluded from the analyses resulting in usable data from a total of 200 women. Mean age ± standard deviation was 46 ± 6 years. Women were mostly white, the majority was married and living in a home with 2 adults, while 29% lived alone. About one third had ≥ one child 13–18 yrs of age, one fourth had ≥ one child 6–12 yrs of age, and one fifth had ≥ one child under the age of 6. Almost all were employed full or part time, and about 67% had a 4 yr college degree or a postgraduate degree.

The k-means cluster analysis identified 6 distinct need categories or ‘need’ states based on how the occasions grouped together. Specific eating occasions were clustered into categories and described by the profile of needs that women experienced surrounding the occasion and the benefits they sought in the foods they selected for the occasion. Each need state is described based on the pattern of needs and benefits that distinguish them from one another and the distribution of eating occasions by segments in the following narrative interpretation.

Routine Family Meal (11% - 60 occasions of the 559 total occasions)

In the “Routine family meal” need state, the priority is fulfilling the woman’s perceived role as meal provider for her family. It is likely to be a routine family dinner, but one of the few times that the family gathers and communicates with one another. Meal preparation serves as an expression of love, with the preparer seeking appreciation from her family. The foods served need to be acceptable to all members to avoid complaints and maintain harmony. Many times, this results in the woman having to serve foods acceptable to the tastes of the children.

Healthy Regimen (28% - 160 occasions of the 559 total occasions)

In the “Healthy regimen” need state, women proactively place a high priority on health and nutrition. This means actively trying to balance food intake within and across meals, eat foods with positive nutrients, and avoid foods with ingredients that are “bad-for-you.” From an emotional standpoint, women derive a sense of well being in feeling they are caring for themselves and not feeling guilty for what they have eaten.

Comforting Personal Time (21% - 116 occasions of the 559 total occasions)

In the “Comforting personal time” need state, the priority is having a moment of quality personal time. The individual is seeking to refresh herself generally through having a moment alone and having something comforting to eat. The foods selected are likely to be routine choices and personal favorites, but they also need to meet practical constraints with respect to being somewhat healthful, convenient, and a good value.

Fast Fueling (21% - 114 occasions of the 559 total occasions)

In the “Fast fueling” need state, the priority is on eating immediately and quickly. To satisfy these needs, women choose foods that need no preparation. The occasions reflect a compromising mindset of having to “grab” something readily available and easy to eat during a busy day thereby avoiding or minimizing any disruption of other activities in which they are engaged.

Family Ritual (8% - 46 occasions of the 559 total occasions)

In the “Family ritual” need state, the priority is on strengthening a sense of family identity among its members. These meals carry ritualistic aspects in the foods served and in the situation. Memories of the past and the individual’s own childhood likely serve as a basis for the teaching and continuation of traditions from generation to generation, and may also serve as a means of connecting the family to its cultural /ethnic heritage.

Indulgent Escape (11% - 63 occasions of the 559 total occasions)

In the “indulgent escape” need state, the priority is in seeking a brief diversion from the day’s activities and stresses through eating. The woman regards the occasion as a reward or break in the day, and seeks food options that are indulgent and can command her full attention.

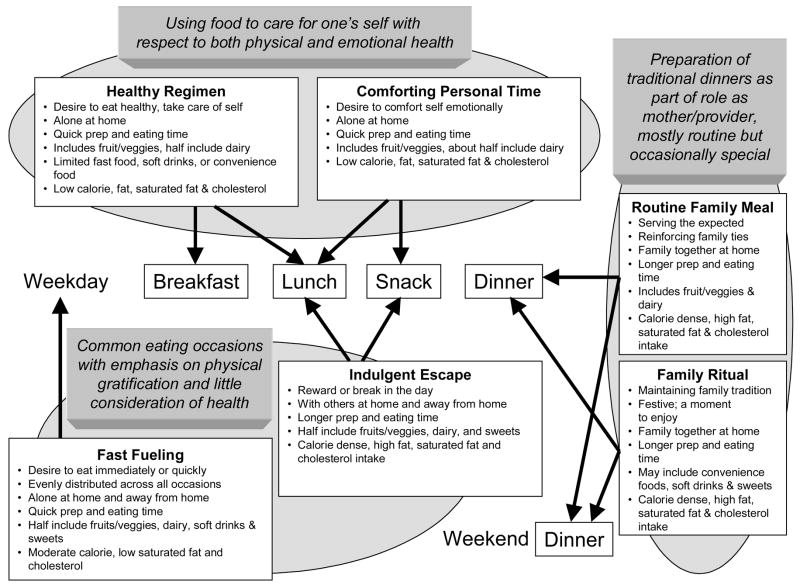

Figure 1 shows a general graphic representation of the need state segments, with descriptive information about each segment and the relationship to intake and situational context, such as whether others were present or the location of the meal/snack. The remaining tables present numerical data regarding relationships between the need state segments and intake and situational context.

Fig. 1.

Cluster descriptions and correlates

“Routine family meal” and “family ritual” eating occasions tended to be experienced at dinner while “healthy regimen” eating occasions were often experienced at breakfast and lunch (Table 4). Post hoc chi-square analysis (separate 2 × 2 chi-square tests) showed that a higher proportion of “routine family meal” occasions was experienced at dinner than were all other types of occasions except for “family ritual” occasions, while a higher proportion of “family ritual” occasions was experienced at dinner than were “healthy regimen” and “comforting personal time” occasions. Post hoc chi-square analysis also showed that a significantly higher proportion of “healthy regimen” eating occasions were experienced at breakfast than were “routine family meals” eating occasions. “Comforting personal time” and “indulgent escape” eating occasions were experienced most often at lunch and snack time, respectively. Post hoc chi-square analysis showed that a higher proportion of “comforting personal time” and “indulgent escape” eating occasions were experienced as a snack than were “routine family meals” eating occasions. “Indulgent escape” occasions were also more often experienced as a snack than were “family ritual” eating occasions. The frequency of the “fast fueling” eating occasions was equally distributed among all the meal/snack types.

Table 4.

Characteristics of eating occasions by six need state segments

| Type of meala | Day of weekb | Placec | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | Snack | Weekday (Mon-Thu) | Weekend (Fri-Sun) | At home | Away from home | |||||||||

| Need state segments | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Routine family meal (N = 60) | 7 | 11.7 | 12 | 20.0 | 37 | 61.7 | 4 | 6.7 | 31 | 51.7 | 29 | 48.3 | 45 | 75.0 | 15 | 25.0 |

| Healthy regimen (N = 160) | 58 | 36.3 | 54 | 33.8 | 26 | 16.3 | 22 | 13.8 | 124 | 77.5 | 36 | 22.5 | 102 | 63.8 | 58 | 36.3 |

| Comforting personal time (N = 116) | 30 | 25.9 | 40 | 34.5 | 16 | 13.8 | 30 | 25.9 | 86 | 74.1 | 30 | 25.9 | 69 | 59.5 | 47 | 40.5 |

| Fast fueling (N = 114) | 25 | 21.9 | 30 | 26.3 | 34 | 29.8 | 25 | 21.9 | 79 | 69.3 | 35 | 30.7 | 65 | 57.0 | 49 | 43.0 |

| Family ritual (N = 46) | 11 | 23.9 | 11 | 23.9 | 21 | 45.7 | 3 | 6.5 | 24 | 52.2 | 22 | 47.8 | 34 | 73.9 | 12 | 26.1 |

| Indulgent escape (N = 63) | 10 | 15.9 | 19 | 30.2 | 14 | 22.2 | 20 | 31.7 | 43 | 68.3 | 20 | 31.7 | 31 | 49.2 | 32 | 50.8 |

| Total | 141 | 25.2 | 166 | 29.7 | 148 | 26.5 | 104 | 18.6 | 387 | 69.2 | 172 | 30.8 | 346 | 61.9 | 213 | 38.1 |

Pearson’s chi-square = 88.226, P = 0.000.

Pearson’s chi-square = 21.448, P = 0.001.

Pearson’s chi-square = 13.156, P = 0.022.

About three-fourths of “healthy regimen” and “comforting personal time” eating occasions were experienced on a weekday whereas nearly half of “routine family meal” and “family ritual” eating occasions were on weekends. Post hoc chi-square analysis showed that the distribution of “healthy regimen” eating occasions between weekday and weekend was significantly different from those of “routine family meal” and “family ritual” eating occasions. About three-fourths of “routine family meal” and “family ritual” eating occasions occurred at home but more than half of “indulgent escape” eating occasions occurred away from home. However, post hoc chi-square tests did not indicate significant differences in eating at home or away from home between any pair of six need states segments.

Post hoc chi-square analysis showed that a higher proportion of “healthy regimen,” “comforting personal time,” and “fast fueling” eating occasions (~ 87%) were experienced when the women were alone than were “family ritual” and “indulgent escape” eating occasions (Table 5). On the other hand, a higher proportion of “routine family meal” eating occasions (65%) were experienced when women were with other adult and child family members than were all other types of occasions except for “family ritual” occasions. Post hoc chi-square analysis also showed that a higher proportion of “family ritual” eating occasions (34.8%) was experienced when women were with child family members than were “comforting personal time” occasions (8.6%).

Table 5.

Situational context of eating occasions by six need state segments

| Need state segments | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Routine family meal (N = 60) | Healthy regimen (N = 160) | Comforting personal time (N = 116) | Fast fueling (N = 114) | Family ritual (N = 46) | Indulgent escape (N = 63) | |||||||

| No. of people present | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Adult family members** | ||||||||||||

| 1 adult1 | 21 | 35.0 | 138 | 86.3 | 101 | 87.1 | 100 | 87.7 | 24 | 52.2 | 40 | 63.5 |

| ≥ 2 adults | 39 | 65.0 | 22 | 13.8 | 15 | 12.9 | 12 | 12.3 | 22 | 47.8 | 23 | 36.5 |

| Child family members** | ||||||||||||

| No children | 24 | 40.0 | 134 | 83.8 | 106 | 91.4 | 96 | 84.2 | 30 | 65.2 | 52 | 82.5 |

| ≥ 1 child2 | 36 | 60.0 | 26 | 16.3 | 10 | 8.6 | 18 | 15.8 | 16 | 34.8 | 11 | 17.5 |

| Who prepared the food* | ||||||||||||

| Participant | 42 | 89.4 | 129 | 93.5 | 83 | 92.2 | 75 | 90.4 | 33 | 89.2 | 26 | 74.3 |

| Others | 5 | 10.6 | 9 | 6.5 | 7 | 7.8 | 8 | 9.6 | 4 | 10.8 | 9 | 25.7 |

| Preparation time** | ||||||||||||

| No time | 2 | 3.3 | 20 | 12.5 | 29 | 25.0 | 28 | 24.6 | 3 | 6.5 | 8 | 12.7 |

| Under 5 minutes | 8 | 13.3 | 54 | 33.8 | 45 | 38.8 | 48 | 42.1 | 5 | 10.9 | 15 | 23.8 |

| 5–10 minutes | 6 | 10.0 | 46 | 28.8 | 20 | 17.2 | 17 | 14.9 | 9 | 19.6 | 11 | 17.5 |

| More than 11 minutes | 44 | 73.3 | 40 | 25.0 | 22 | 19.0 | 21 | 18.4 | 29 | 63.0 | 29 | 46.0 |

| Eating time** | ||||||||||||

| Under 15 minutes | 7 | 11.7 | 79 | 49.4 | 53 | 45.7 | 56 | 49.1 | 6 | 13.0 | 18 | 28.6 |

| 16–20 minutes | 13 | 21.7 | 37 | 23.1 | 28 | 24.1 | 29 | 25.4 | 15 | 32.6 | 17 | 27.0 |

| More than 21 minutes | 40 | 66.7 | 44 | 27.5 | 35 | 30.2 | 29 | 25.4 | 25 | 54.3 | 28 | 44.4 |

Including herself.

Under the age of 18. Pearson’s chi-square test,

P < 0.05;

P < 0.001.

The percentage of eating occasions in which the food was prepared by others was the highest in “indulgent escape” eating occasions (about 26%). However, post hoc chi-square tests did not indicate significant differences in who prepared the food between any pair of six need states segments. For more than half of “fast fueling” and “comforting personal time” eating occasions, respectively, women decided what to eat immediately before eating (not shown in Table). Post hoc chi-square analysis showed that the proportion of eating occasions in which preparation time was under five minutes was higher in “healthy regimen,” (~34%) “comforting personal time,” (~39%) and “fast fueling” (~42%) eating occasions than in “routine family meal” (~13%) and “family ritual” (~11%) eating occasions. In addition, the proportion of occasions where prep time was less than five minutes was also higher for “comforting personal time” and “fast fueling” eating occasions than for “indulgent escape” (~24%) occasions. The proportion of eating occasions in which prep time was under five minutes was also higher in “fast fueling” occasions than in “healthy regimen” occasions.

Eating time was the longest in “routine family meal” occasions where ~67% of the occasions were longer than 21 minutes. Post hoc chi-square analysis showed that a significant difference in distribution of eating times was observed between “routine family meal” occasions and “healthy regimen,” “comforting personal time,” and “fast fueling” occasions and between “family ritual” occasions and “healthy regimen” and “fast fueling” occasions.

The proportion of eating occasions for which women were very satisfied with the food they ate overall was the highest for “family ritual” (50%) eating occasions, followed by “healthy regimen” (48%), “indulgent escape” (41%), “comforting personal time” (37%), “routine family meal” (37%), and “fast fueling” (21%) eating occasions (Table 6). For the dimension of taste, the proportion of eating occasions for which women were very satisfied with the food they ate was the highest for “family ritual” (48%) eating occasions and the lowest for “fast fueling” (26%) eating occasions. For ease of acquiring, amount of planning required, ease of preparation, ease of eating, ease of clean-up, amount of time required to prepare, amount of time required to eat, and amount of time required to clean-up, satisfaction was lowest for “routine family meal” eating occasions. The proportion of eating occasions for which women were very satisfied with the healthfulness of the food they ate, presence of beneficial nutrients, avoidance of ingredients that were bad for them, and appeal to others present were highest for “healthy regimen” eating occasions. The proportion of eating occasions for which women were very satisfied with the price of the food they ate, satisfaction of hunger, appeal to others present, and comfort were lowest for “fast fueling” eating occasions. For slightly less than half of the “indulgent escape” eating occasions, women were very satisfied with the comfort derived from the food they ate.

Table 6.

Satisfaction with the food eaten on the occasion by six need state segments1

| Need state segments | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Routine family meal (N = 60) | Healthy regimen (N = 160) | Comforting personal time (N = 116) | Fast fueling (N = 114) | Family ritual (N = 46) | Indulgent escape (N = 63) | |||||||

| No. of people who were “very satisfied” | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Overall satisfaction*** | 22 | 36.7 | 76 | 47.5 | 43 | 37.1 | 24 | 21.1 | 23 | 50.0 | 26 | 41.3 |

| Taste*** | 26 | 43.3 | 73 | 45.6 | 46 | 39.7 | 30 | 26.3 | 22 | 47.8 | 25 | 39.7 |

| Ease of acquiring** | 22 | 36.7 | 97 | 60.6 | 81 | 69.8 | 55 | 48.2 | 25 | 54.3 | 35 | 55.6 |

| Amount of planning required*** | 22 | 36.7 | 98 | 61.3 | 87 | 75.0 | 60 | 52.6 | 26 | 56.5 | 37 | 58.7 |

| Ease of preparation** | 26 | 43.3 | 103 | 64.4 | 89 | 76.7 | 65 | 57.0 | 27 | 58.7 | 38 | 60.3 |

| Ease of eating*** | 23 | 38.3 | 105 | 65.6 | 88 | 75.9 | 59 | 51.8 | 28 | 60.9 | 38 | 60.3 |

| Ease of clean-up*** | 23 | 38.3 | 101 | 63.1 | 86 | 74.1 | 64 | 56.1 | 26 | 56.5 | 36 | 57.1 |

| Amount of time required to prepare** | 26 | 43.3 | 102 | 63.8 | 89 | 76.7 | 65 | 57.0 | 24 | 52.2 | 35 | 55.6 |

| Amount of time required to eat* | 25 | 41.7 | 99 | 61.9 | 75 | 64.7 | 54 | 47.4 | 24 | 52.2 | 37 | 58.7 |

| Amount of time required to clean-up*** | 20 | 33.3 | 100 | 62.5 | 86 | 74.1 | 66 | 57.9 | 26 | 56.5 | 34 | 54.0 |

| Healthfulness of the food*** | 15 | 25.0 | 86 | 53.8 | 58 | 50.0 | 20 | 17.5 | 21 | 45.7 | 4 | 6.3 |

| Presence of beneficial nutrients*** | 13 | 21.7 | 78 | 48.8 | 47 | 40.5 | 18 | 15.8 | 19 | 41.3 | 3 | 4.8 |

| Avoidance of ingredients that were bad*** | 11 | 18.3 | 77 | 48.1 | 40 | 34.5 | 17 | 14.9 | 18 | 39.1 | 5 | 7.9 |

| Appeal to others present*** | 28 | 46.7 | 23 | 14.4 | 22 | 19.0 | 11 | 9.6 | 14 | 30.4 | 20 | 31.7 |

| Price** | 18 | 30.0 | 72 | 45.0 | 55 | 47.4 | 34 | 29.8 | 21 | 45.7 | 26 | 41.3 |

| Satisfaction of hunger*** | 26 | 43.3 | 86 | 53.8 | 61 | 52.6 | 41 | 36.0 | 25 | 54.3 | 24 | 38.1 |

| Comfort derived from the food*** | 14 | 23.3 | 31 | 19.4 | 31 | 26.7 | 18 | 15.8 | 14 | 30.4 | 27 | 42.9 |

Satisfaction was assessed by a 6 point scale where “1” means “very dissatisfied” and “6” means “very satisfied.” Pearson’s chi-square test

(6×6),

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

During 77% and 25% of “routine family meal” eating occasions, women were engaged in conversation with others and caring for others, respectively. Women worked during about one-fourth of the “fast fueling” eating occasions and watched television during about one-third of “indulgent escape” eating occasions.

The proportion of eating occasions in which fruits/vegetables were eaten was high in “routine family meal” and “healthy regimen” eating occasions and low in “fast fueling” and “indulgent escape” occasions (Table 7). The proportion of eating occasions in which dairy/calcium-rich foods was eaten was high in “comforting personal time” and “indulgent escape” eating occasions. Energy, total fat, and cholesterol intake per eating occasion were the highest in “routine family meal” occasions which differed significantly from “healthy regimen,” “comforting personal time,” and “fast fueling” occasions (Table 8).

Table 7.

The number (%) of eating occasions in which food intake from nine food groups was observed

| Need state segments | Routine family meal | Healthy regimen | Comforting personal time | Fast fueling | Family ritual | Indulgent escape | Chi-sq test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food group | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | P1 |

| Fruits/vegetables | 48 | 80.0 | 119 | 74.4 | 79 | 68.1 | 63 | 55.3 | 31 | 67.4 | 35 | 55.6 | 0.001 |

| Dairy/calcium-rich foods | 26 | 43.3 | 79 | 49.4 | 65 | 56.0 | 55 | 48.2 | 23 | 50.0 | 37 | 58.7 | 0.465 |

| Fast food | 2 | 3.3 | 2 | 1.3 | 3 | 2.6 | 7 | 6.1 | 2 | 4.3 | 3 | 4.8 | 0.347 |

| Convenience foods (meal type) | 6 | 10.0 | 13 | 8.1 | 7 | 6.0 | 12 | 10.5 | 6 | 13.0 | 3 | 4.8 | 0.539 |

| Convenience foods (non-meal type) | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 5.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.019 |

| Supplements/meal replacements | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 8.8 | 6 | 5.2 | 2 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.6 | 0.007 |

| Carbonated soft drinks | 6 | 10.0 | 9 | 5.6 | 13 | 11.2 | 18 | 15.8 | 6 | 13.0 | 6 | 9.5 | 0.156 |

| Sweets (dairy) | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 3.1 | 3 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 6.3 | 0.050 |

| Sweets (non-dairy) | 2 | 3.3 | 10 | 6.3 | 8 | 6.9 | 13 | 11.4 | 8 | 17.4 | 13 | 20.6 | 0.003 |

Exact test (two-tailed).

Table 8.

Median, 25 and 75 percentiles of energy and nutrient intake per occasion by need state segments

| Intake per occasion | Energy (kcal) | Total fat (g) | Saturated fat (g) | Cholesterol (mg) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Need state segments | N | Median | 25% | 75% | Median | 25% | 75% | Median | 25% | 75% | Median | 25% | 75% |

| Routine family meal | 60 | 664 | 408 | 928a | 25.2 | 12.4 | 40.2a | 7.0 | 4.0 | 13.2a | 75.4 | 22.4 | 140.3a |

| Healthy regimen | 160 | 384 | 278 | 497b | 11.8 | 4.6 | 18.5b | 3.0 | 1.3 | 5.9b | 15.0 | 2.3 | 56.7b |

| Comforting personal time | 116 | 393 | 225 | 567b | 13.2 | 5.8 | 23.7bc | 4.3 | 1.4 | 7.7bc | 26.2 | 0.0 | 76.3bc |

| Fast fueling | 114 | 439 | 250 | 705bc | 13.3 | 4.9 | 24.1bc | 3.8 | 1.4 | 7.7bc | 21.6 | 4.4 | 61.3bc |

| Family ritual | 46 | 591 | 391 | 816ac | 19.2 | 11.6 | 33.5ac | 5.1 | 3.8 | 11.0ac | 59.3 | 22.5 | 146.3a |

| Indulgent escape | 63 | 591 | 391 | 816ac | 24.0 | 11.2 | 43.4a | 7.4 | 3.2 | 15.8a | 58.1 | 11.4 | 128.9ac |

Significantly differed between different superscript letters by Mann-Whitney’s U test, P < 0.003.

Discussion

Segmentation analysis resulted in six eating need state segments driven by needs which were consistent with observations regarding situational context and dietary intake representing both positive and negative aspects of dietary behavior. For example, occasions which were commonly experienced at home at a dinner meal with others were higher in calories and fat but were more likely to contain fruits and vegetables. The observations regarding needs within occasions, accompanying intake and situational context had some similarities to findings of others with implications for interventions to change intake and reduce risk for overweight and obesity in midlife women.

“Indulgent escape” occasions were more likely to occur as a snack or lunch vs. dinner or breakfast with about 64% being eaten alone. These findings support the priority described for this need state regarding a desire to take a break from activities or to relieve stress. For these occasions, intake of energy, saturated fat, sweets, and dairy/calcium rich foods was high, while intake of fruits and vegetables was low compared to other occasions. Several studies have shown that more indulgent foods are consumed as coping mechanisms to relieve stress or to satisfy cravings. A laboratory study showed that stressed emotional eaters ate more sweet high fat food and a more energy-dense food than unstressed and non-emotional eaters (Oliver, Wardle, & Gibson, 2000). Another study considered the nature of craving in 108 healthy women between the ages of 20 and 37 and showed that chocolate and ice cream were highest on the list of foods craved (Rodin et al., 1991). Gilhooly et al. (2007) identified high energy density and fat content, and low protein and fiber contents as characteristics of craved foods. A link was also made between mood regulation and intake of sweet food by women in a study by Barkeling et al. (2002). In addition to links between mood, stress and eating behaviors, a correlation between higher BMI and more perceived stress and emotional eating was observed in a US population of which 65% were midlife women (Delahanty et al., 2002).

More than half of “indulgent escape” eating occasions experienced by women in our study occurred away from home which may have contributed to their higher calorie level. According to nationwide surveys of food consumption, meals and snacks based on food prepared away from home contained more calories per eating occasion (Guthrie, Lin, & Frazao, 2002). About one third of “indulgent escape” occasions in our study were experienced by women while watching television which may predispose women to greater risk for overweight. Johnson et al. (2006) found associations between eating and snacking while watching television and obesity after adjusting for demographic variables, smoking, physical activity, and depression among women veterans.

“Fast fueling” occasions experienced by women in our study were also likely to occur away from home, while the woman was alone and involved eating fast food. Eating during these occasions caused women to compromise on dimensions of taste and comfort to satisfy the need for convenience and utility. Needs surrounding these types of occasions are likely to be driven by ‘time scarcity’ or the feeling of not having enough time (Jabs & Devine, 2006). Jabs and Devine (2006) implicated time scarcity as a reason underlying changes in food consumption patterns such as a decrease in food preparation at home, an increase in the consumption of fast foods, and a decrease in family meals. The percentage of eating occasions in which energy dense foods such as fast food and carbonated soft drinks was consumed was the highest in “fast fueling” eating occasions. In those eating occasions, the percentage of women who were very satisfied with price was the lowest. A French study suggested that an energy dense diet would be preferentially selected when the budget for food was low (Darmon, Ferguson, & Briend, 2003).

“Routine family meal” occasions were more likely to be dinner meals compared to other meals with 60% involving a meal eaten with children. These occasions were also highest in energy, total fat, and cholesterol intake per occasion consistent with findings from NHANES III data which showed that the presence of children in the household was associated with significantly higher adjusted total fat and saturated fat consumption for adults (Laroche et al., 2007). In addition, in 65% of the occasions, adult family members were present. In another study, simply eating with one other person increased the average amount ingested in meals by 44% and with more people present the average meal size grew even larger (De Castro, 1997). Meals eaten with others contained more carbohydrate, fat, protein, and total calories (De Castro & De Castro, 1989). Also, intake was higher when others present were better known or more familiar to the subject, such as a family member or close friend (Stroebele & De Castro, 2004). Eating with friends and family may be relaxing and cause people to linger to enjoy conversation; thereby increasing meal duration. Eating time was the longest in the “routine family meal” eating occasions with 67% involving a meal taking more than 21 minutes. Since “routine family meal” occasions were more substantial, it was also likely that they would include fruits and vegetables more often than other types of occasions. Fruit and vegetable consumption was positively associated with social norms and social networks which were assessed by items such as how many of their family and friends eat at least five servings of fruits and vegetables a day and whether the participant had a spouse or partner (Emmons et al., 2007). While intake of calories and fat may be higher in these occasions, the consumption of fruits and vegetables is positive given that several studies have shown an association between greater intake of fruits and vegetables and lower risk for obesity. For example in a cross-sectional study with Portuguese adults, the odds favoring obesity in women decreased with consumption of fruits (Moreira & Padrão, 2006) and fruit and vegetable intake was inversely associated with excess weight in a US multiethnic population (Maskarinec et al., 2006). More than half of the eating occasions in the current study included fruits and vegetables regardless of type of eating occasion. This may be unique to our sample since 95% had some college education and fruit and vegetable intake has been shown to be associated with education level in women (Ward et al., 2007).

The percentage of eating occasions in which supplements/meal replacements were consumed was the highest in “healthy regimen” eating occasions. In those occasions, around 50% of women were very satisfied with “healthfulness of the food” and “presence of beneficial nutrients.” According to research on consumer attitudes, the best predictors for willingness to use functional foods were the perceived reward and the necessity for such foods (Urala & Lähteenmäki, 2007).

Limitations of this study include several known problems with cluster analysis (Tan, Steinbach, & Kumar, 2006). They include the sensitivity to outliers, dependence of the cluster solutions on initial partition (cluster seeds), and the inability to handle non globular shaped clusters (clusters of different sizes and densities). Elimination of constant raters among the respondents helped to manage the outlier problem. Repeated searches for different cluster solution with randomly selected seeds helped to minimize the dependence of cluster analysis results on initial seed choices. When the numbers of clusters sought from the data is high, the k-means method is usually successful at finding pure sub clusters thereby averting the anticipated problem with non globular clusters.

Our convenience sample did not represent the average midlife woman in the US, therefore limiting generalizability of the findings. Many participants were recruited on a university campus so their education level was higher than a general population. While women were instructed to complete need state questions immediately after eating, we could not confirm that this was the case, thus representing a limitation to this study. In addition, limitations also include the possibility of recording errors regarding food intake, however, a pictorial as well as verbal report was used to enhance accuracy. We were able to categorize foods into many groups based on previous classification (US FDA & DHHS, 2002; USDA, 2005); however, we were not able to find existing studies that had easily categorized foods according to convenience. In addition, food categorization varied by studies, making it difficult to compare results (Malik, Schulze, & Hu, 2006).

The type of food eaten and energy and fat intake were significantly different by eating occasions according to needs surrounding the occasion. Segmenting eating occasions therefore represents another way to approach the need to tailor interventions according to individual needs and situational context. For example, “indulgent escape” occasions represented high risk situations for overconsuming energy and fat. A high proportion of these occasions were consumed alone for snack or lunch. Therefore, public health nutrition strategies could target needs within these situations to reduce energy and fat intake among midlife women. Education regarding appropriate portion sizes for indulgent foods and stress management may also be key elements of public health nutrition strategies for these situations.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by R21-DK067296-02, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and in part by M01-RR00400 National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albrecht TL, Bryant C. Advances in segmentation modeling for health communication and social marketing campaigns. Journal of Health Communication. 1996;1:65–80. doi: 10.1080/108107396128248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK. Cluster Analysis. Newbury Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Barkeling B, Linné Y, Lindroos AK, Birkhed D, Rooth P, Rössner S. Intake of sweet foods and counts of cariogenic microorganisms in relation to body mass index and psychometric variables in women. International Journal of Obesity. 2002;26:1239–1244. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contento IR, Basch C, Shea S, Gutin G, Zybert P, Michela JL, Rips L. Relationship of mothers’ food choice criteria to food intake of preschool children: identification of family subgroups. Health Education Quarterly. 1993;20:243–259. doi: 10.1177/109019819302000215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmon N, Ferguson E, Briend A. Do economic constraints encourage the selection of energy dense diets? Appetite. 2003;41:315–322. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(03)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Birch LL. Obesigenic families: parents’ physical activity and dietary intake patterns predict girls’ risk of overweight. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolism and Disorders. 2002;26:1186–1193. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Castro JM. Socio-cultural determinants of meal size and frequency. British Journal of Nutrition. 1997;77:S39–54. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Castro JM, De Castro ES. Spontaneous meal patterns of humans: influence of the presence of other people. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1989;50:237–247. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delahanty LM, Williamson DA, Meigs JB, Nathan DM, Hayden D The DDP Research Group. Psychological and behavioral correlates of baseline BMI in the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1992–1998. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.11.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond SE, Crombie NE, Cursiter MC, Kirk TR. Evidence that eating frequency is inversely related to body weight status in male, but not female, non-obese adults reporting valid dietary intakes. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 1998;22:105–112. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons KM, Barbeau EM, Guthheil C, Stryker JE, Stoddard AM. Social influences, social context, and health behaviors among working-class, multi-ethnic adults. Health Education & Behavior. 2007;34:315–334. doi: 10.1177/1090198106288011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson KA, Simon HA. Protocol Analysis: Verbal Reports as Data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Field AE, Willett WC, Lissner L, Colditz GA. Dietary fat and weight gain among women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Obesity. 2007;15:967–976. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Wilde PE, Lichtenstein AH, Tucker KL. Meeting adequate intake dietary calcium without dairy foods in adolescents aged 9 to 18 years (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2002) Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:1759–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhooly CH, Das SK, Golden JK, McCrory MA, Dallal GE, Saltzman E, Kramer FM, Roberts SB. Food cravings and energy regulation: the characteristics of craved foods and their relationship with eating behaviors and weight change during 6 months of dietary energy restriction. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31:1849–1858. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez AJ, White E, Kristal A, Littman AJ. Calcium intake and 10-year weight change in middle-aged adults. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SM, Blundell JE. Effect of fat- and sucrose-containing foods on the size of eating episodes and energy intake in lean dietary restrained and unrestrained females: potential for causing overconsumption. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1996;50:625–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrieri R, Nederkoorn C, Stankiewicz K, Alberts H, Geschwind N, Martijn C, Jansen A. The influence of trait and induced state impulsivity on food intake in normal-weight healthy women. Appetite. 2007;49:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie JF, Lin BH, Frazao E. Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977–78 versus 1994–96: changes and consequences. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2002;34:140–150. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs J, Devine CM, Bisogni CA, Farrell TJ, Jastran M, Wethington E. Trying to find the quickest way: employed mothers’ constructions of time for food. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2007;39:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J, Devine CM. Time scarcity and food choices: an overview. Appetite. 2006;47:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KM, Nelson KM, Bradley KA. Television viewing practices and obesity among women veterans. Journal of Genetics and Internal Medicine. 2006;21:S76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser HF, Caffrey J. Alpha factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30:1–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02289743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche HH, Hofer TP, Davis MM. Adult fat intake associated with the presence of children in households: findings from NHANES III. Journal of American Board of Family Medicine. 2007;20:9–15. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.01.060085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84:274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskarinec G, Tanaka Y, Pagano I, Carlin L, Goodman MT, Marchand LL, Nomura AMY, Wilkins LR, Kolonel LN. Trends and dietary determinants of overweight and obesity in a multiethinic population. Obesity. 2006;14:717–726. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira P, Padrão P. Educational, economic and dietary determinants of obesity in Portuguese adults: a cross-sectional study. Eating Behaviors. 2006;7:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver G, Wardle J, Gibson EL. Stress and food choice: a laboratory study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62:853–865. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200011000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P, Mann N. Influence of social norms and palatability on amount consumed and food choice. Appetite. 2004;42:227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley N, Leith A. Understanding need states and their role in developing successful marketing strategies. International Journal of Marketing Research. 1998;40:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SB, Dallal GE. Energy requirements and aging. Public Health Nutrition. 2005;8:1028–1036. doi: 10.1079/phn2005794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J, Mancuso J, Granger J, Nelbach E. Food cravings in relation to body mass index, restraint and estradiol levels: a repeated measures study in healthy women. Appetite. 1991;17:177–185. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(91)90020-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staten LK, Birnbaum AS, Jobe JB, Elder JP. A typology of middle school girls: audience segmentation related to physical activity. Health Education Behavior. 2006;33:66–80. doi: 10.1177/1090198105282419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternfeld B, Wang H, Quesenberry CP, Abrams B, Everson-Rose SA, Greendale GA, Matthews KA, Torrens JI, Sowers M. Physical activity and changes in weight and waist circumference in midlife women: Findings from the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;169:912–922. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebele N, De Castro JM. Effect of ambience on food intake and food choice. Nutrition. 2004;20:821–838. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PW, Wyatt HR, Morrato EH, Hill JO, Ghushchyan V. Obesity, inactivity, and the prevalence of diabetes and diabetes-related cardiovascular comorbidities in the U.S., 2000–2002. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1599–1603. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan P-N, Steinbach M, Kumar V. Introduction to Data Mining. Boston, MA: Pearson Addison Wesley; 2006. Cluster analysis: basic concepts and algorithms. [Google Scholar]

- Tooze JA, Schoeller DA, Subar SF, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A, Troiano RP. Total daily energy expenditure among middle-aged men and women: the OPEN Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;86:382–287. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.2.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urala N, Lähteenmäki L. Consumers’ changing attitudes towards functional foods. Food Quality and Preference. 2007;18:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, MyPyramid Food Guidance System. USDA Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion; Alexandria, VA: 2005. [Accessed 12-12-07]. < www.mypyramid.gov>. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration, & US Department of Health and Human Services. Code of Federal Regulations, Reference amounts customarily consumed per eating occasion. 2002. 21 CFR Ch.1 (4-1-02 Edition) pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vue H, Degeneffe D, Reicks M. Needs driving food choice in specific eating occasions for midlife women. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.09.009. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward H, Tarasuk V, Mendelson R, McKeown-Eyssen G. An exploration of socioeconomic variation in lifestyle factors and adiposity in the Ontario Food Survey through structural equation modeling. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007;4:8–19. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Shu XO, Gao YT, Zhang S, Li H, Zheng W. Impacts of weight change on prehypertension in middle-aged and elderly women. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31:1818–1825. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]