Abstract

NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease), associated with obesity and the cardiometabolic syndrome, is an important medical problem affecting up to 20% of western populations. Evidence indicates that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a critical role in NAFLD initiation and progression to the more serious condition of NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis). Herein we hypothesize that mitochondrial defects induced by exposure to a HFD (high fat diet) contribute to a hypoxic state in liver and this is associated with increased protein modification by RNS (reactive nitrogen species). To test this concept, C57BL/6 mice were pair-fed a control diet and HFD containing 35% and 71% total calories (1 cal≈4.184 J) from fat respectively, for 8 or 16 weeks and liver hypoxia, mitochondrial bioenergetics, NO (nitric oxide)-dependent control of respiration, and 3-NT (3-nitrotyrosine), a marker of protein modification by RNS, were examined. Feeding a HFD for 16 weeks induced NASH-like pathology accompanied by elevated triacylglycerols, increased CYP2E1 (cytochrome P450 2E1) and iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase) protein, and significantly enhanced hypoxia in the pericentral region of the liver. Mitochondria from the HFD group showed increased sensitivity to NO-dependent inhibition of respiration compared with controls. In addition, accumulation of 3-NT paralleled the hypoxia gradient in vivo and 3-NT levels were increased in mitochondrial proteins. Liver mitochondria from mice fed the HFD for 16 weeks exhibited depressed state 3 respiration, uncoupled respiration, cytochrome c oxidase activity, and mitochondrial membrane potential. These findings indicate that chronic exposure to a HFD negatively affects the bioenergetics of liver mitochondria and this probably contributes to hypoxic stress and deleterious NO-dependent modification of mitochondrial proteins.

Keywords: cytochrome c oxidase, hypoxia, liver, mitochondria, nitric oxide, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

Abbreviations: CYP2E1, cytochrome P450 2E1; DAB, diaminobenzidine; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone; HFD, high fat diet; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; JC-1, 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazol carbo-cyanine iodide; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; 3-NT, 3-nitrotyrosine; PAPA NONOate, 1-propanamine, 3-(2-hydroxy-2-nitroso-1-propylhydrazino); RCR, respiratory control ratio; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species

INTRODUCTION

NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease), a key component of the cardiometabolic syndrome, has emerged as one of the most common aetiologies of chronic liver disease. NAFLD can progress from simple fatty liver (i.e. steatosis) to more severe conditions such as NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis), and cirrhosis, if left untreated. Estimates place the prevalence of NAFLD in the general U.S.A. population at 20%, with the more severe form, NASH, present at 3–5% [1,2]. Even more startling is the fact that NAFLD is present in pediatric populations, with prevalence estimated at 2–10% among children and adolescents in the U.S.A. and Asian countries [3]. NASH is characterized histologically by macrosteatosis, inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and pericellular fibrosis in zone 3 of the liver lobule. Insulin resistance, disrupted fatty acid metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and dysregulation of adipocytokine networks are proposed to be critical factors in the development of NASH. The interaction between these factors is, however, not well understood, which has slowed progress in developing a clear molecular understanding of NASH pathogenesis. In this study, we propose that a loss in control over the regulation of oxygen supply and demand in the liver may be a major contributory factor for the initiation and progression of this complex disease pathology.

The concept that hypoxia may play a critical role in the aetiology of liver diseases is well established in other pathologies associated with steatosis. For example, Arteel et al. [4,5] demonstrated that chronic and acute alcohol exposure causes hypoxia in the pericentral region of the liver presumably due to increased O2 consumption in response to alcohol metabolism and through the release of vasoconstrictive eicosanoids from Kupffer cells. More recently, chronic hypoxia has been implicated as a contributing factor in liver injury in response to obstructive sleep apnea [6], which has also been linked to the cardiometabolic syndrome and NASH [7]. Savransky et al. [6] found that chronic intermittent hypoxia in combination with a HFD (high fat diet) induces inflammation and lipid peroxidation in mice, with increased steatosis observed in the hypoxia exposure group. In the present study, it was hypothesized that the interaction of hypoxia with secondary insults or ‘stressors’ such as a HFD may be responsible for the progression from simple steatosis to NASH. What has not been examined, however, is whether exposure to a HFD alone is sufficient to induce liver injury, mitochondrial dysfunction, and hypoxia without the additional stressor of whole body O2 deprivation.

Currently, NASH pathogenesis is proposed to occur in response to fat accumulation in hepatocytes coupled with mitochondrial dysfunction, which may be manifested by disrupted fatty acid oxidation, depressed bioenergetics and increased oxidative stress arising from enhanced generation of ROS (reactive oxygen species) and RNS (reactive nitrogen species) [8]. Indeed, one key functional change to liver mitochondria in animal models of obesity-induced fatty liver disease is the inability to maintain sufficient ATP levels. This may result from impaired electron transport and/or increased proton leak across the inner mitochondrial membrane, which dissipates the membrane potential and decreases the capacity for ATP synthesis [9]. Hepatic mitochondria of NASH patients exhibit para-crystalline inclusions in mega-mitochondria [10], increased mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) mutations [11] and lower respiratory complex activities [12]. Studies show that alcohol-induced fatty liver disease is also associated with depressed activity of the respiratory chain via damage to the mtDNA and ribosomes [13,14]. Moreover, we have found alcohol-dependent changes in the mitochondrial proteome [15] and alterations in NO (nitric oxide) signalling in the mitochondrion [16,17]. A role for NO in controlling O2 gradients within tissues and the response to hypoxia has been proposed [18,19]. These mechanisms appear to involve the interaction of NO with mitochondria, and in both the hypoxic stress associated with cardiac failure and alcohol-dependent steatosis, the respiratory chain becomes more sensitive to NO [16,20]. Specifically, NO-dependent inhibition of hepatic mitochondrial respiration is increased following chronic alcohol consumption [16,17], whereas alterations in mitochondrial sensitivity to NO have not been examined in NAFLD or NASH.

Taken together, the results support the hypothesis that defects in mitochondrial bioenergetics play a key role in the progression from simple steatosis to the more severe condition of NASH. Herein, we propose that mitochondrial dysfunction, hypoxic stress and increased protein modifications due to increased ROS and RNS are linked and contribute to the pathophysiology of NASH. In the present study, we tested this hypothesis by feeding C57BL/6 mice a HFD for 8 or 16 weeks and examined the bioenergetics of liver mitochondria and extent of liver hypoxia. Accordingly, studies were undertaken to determine whether the responsiveness of mitochondrial respiration to inhibition by NO was altered by chronic exposure to a HFD.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Chemicals were of the highest quality available and purchased from Sigma–Aldrich unless stated otherwise. PROLI NONOate and PAPA NONOate [1-propanamine, 3-(2-hydroxy-2-nitroso-1-propylhydrazino)] were obtained from Alexis Biochemicals, pimonidazole hydrochloride was from Chemicon International, and JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazol carbo-cyanine iodide) from Invitrogen. Control diets and the HFD were purchased from Dyets (Bethlehem, PA, U.S.A.).

Dietary feeding protocol

Male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, U.S.A.) and fed a HFD containing 71% total calories (1 cal≈4.184 J) as fat, 11% as carbohydrate, and 18% as protein [21]. The control diet contained 35% total calories as fat, 47% as carbohydrate, and 18% as protein. The control diet and HFD are nutritionally adequate, calorifically equivalent (1 kcal/ml), and contain equal amounts of fat as olive and safflower oil with excess corn oil added to the HFD. Mice were maintained on diets for 8 or 16 weeks and handled in accordance with recommendations in the ‘Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’ (NIH publication 86-23 revised 1985). These studies were approved by the UAB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were anaesthetized for liver perfusion procedures using a 50 mg/kg (intraperitoneal) dose of sodium pentobarbital. Animals were monitored daily and weighed weekly, and they showed no pain or distress during the feeding regimen or the experimental procedures.

Liver histology and triacylglycerol measurements

Formalin-fixed liver samples were processed for heamatoxylin-eosin staining and evaluated for steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, and Mallory bodies by a hepatologist that was blind to the experiment. Triacylglycerol content was measured in liver homogenates using the triacylglycerol-GPO reagent set kit (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunohistochemistry for pimonidazole and 3-NT (3-nitrotyrosine)

Liver hypoxia was assessed using the hypoxia marker pimonidazole [4]. Mice were injected with pimonidazole (60 mg/kg in saline, intraperitoneal) and after 1 h, blood and unbound pimonidazole were cleared from the liver by perfusion with warm Gey's Balanced Salt solution. Livers were harvested and processed for immunohistochemistry. Formalin-fixed liver sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through incubations in graded ethanol concentrations. Sections were blocked for 10 min with 5% (w/v) BSA in a TBS-T (Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20) solution and incubated with pimonidazole-1MAb1 conjugated with FITC (1:50 dilution) for 1 h. After washes, slides were incubated for 1 h with anti-FITC conjugated with HRP (horseradish peroxidase), and bound antibody was visualized with DAB (diaminobenzidine) chromagen followed by counterstaining with haematoxylin. Positive pimonidazole protein adduct staining was visualized by brown staining, and the area and intensity of staining were quantified using Simple PCI software (Hamamatsu Corporation, Sewickley, PA, U.S.A.).

Immunohistochemistry for 3-NT was performed essentially as described above and in [17]. Deparaffinized and rehydrated liver sections were subjected to antigen retrieval in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by immersion of the slides in 3% (v/v) H2O2 for 10 min, and tissues were blocked for 1 h at room temperature (25 °C) with 10% (v/v) goat serum in a 1% (w/v) BSA/TBS-T solution. Sections were incubated for 2 h at room temperature in a humidified chamber with rabbit polyclonal 3-NT antibody (a gift from Dr. Alvaro Estevez, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, U.S.A.) at a 1:150 dilution. Following incubation, tissues were washed in TBS-T and incubated with secondary antibody at a 1:200 dilution and bound antibody was visualized with DAB chromagen. Quantification for 3-NT staining was done as described for pimonidazole protein adduct immunohistochemistry.

Immunofluorescence for iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase)

Levels of iNOS protein in liver were assessed by immunofluorescence as described in [17] with the following modifications. OCT-embedded frozen liver sections were fixed in ice-cold acetone for 5 min followed by blocking in 2% (w/v) BSA solution in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. After washes with PBS, tissues were incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit polyclonal iNOS antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, U.S.A.) diluted 1:150. Following incubation, tissues were washed in PBS and incubated with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor® 594 (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, U.S.A.) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were washed with PBS and mounted using VECTASHIELD® mounting medium with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Vector Labs) to visualize nuclei. Images were taken and analysed using a Leica fluorescent microscope with IPLAB Spectrum (BD Biosciences Bioimaging, Scanalytics, Rockville, MD, U.S.A.) with the intensity of fluorescence quantified as described for immunohistochemistry.

Immunoblotting for CYP2E1 (cytochrome P450 2E1) protein and 3-NT in mitochondrial proteins

CYP2E1 protein levels were measured by immunoblotting using 1:1000 dilution of anti-CYP2E1 antibody (Chemicon International) followed by 1:10000 dilution of secondary antibody. Levels of 3-NT in mitochondrial proteins were measured using a 1:1000 dilution of anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY, U.S.A.) followed by 1:10000 dilution of secondary antibody. Protein bands were visualized using chemiluminescence detection. Immunoreactive protein bands and total protein on duplicate stained gels were quantified using Quantity One image analysis software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.).

Preparation of liver mitochondria and respiration measurements

Coupled liver mitochondria were prepared by differential centrifugation of liver homogenates [15] using an ice-cold mitochondria isolation medium containing 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA and 5 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5. Protease inhibitors were added to the isolation buffer to prevent protein degradation. Respiration rates were measured using a Clark-type O2 electrode as described previously [15]. Mitochondria were incubated in respiration buffer containing 130 mM KCl, 3 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2. State 3 and 4 respiration rates and the RCR (respiratory control ratio, calculated as the ratio of state 3 to state 4 respiration rates) were measured with the oxidizable substrates succinate/rotenone (15 mM/5 μM) or glutamate/malate (5 mM each), and ADP (0.5 mM) was added to initiate state 3 respiration. Uncoupler-stimulated respiration was measured in the presence of FCCP (carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone) (1 μM).

Mitochondrial respiratory complex activities and membrane potential measurements

Cytochrome c oxidase activity was measured using a standard spectrophotometric method [22], which monitors oxidation of ferrocytochrome c at 550 nm. Complex I activity (i.e. NADH dehydrogenase) was determined by measuring the rotenone-sensitive rate of oxidation of NADH initiated by coenzyme Q1 [23], and citrate synthase activity was measured as described in [15].

JC-1 is a cationic dye that accumulates within the mitochondrial matrix and is used to assess alterations in membrane potential [24]. In the presence of a high negative membrane potential, JC-1 forms red fluorescent aggregates (emission 590 nm), whereas under depolarized conditions it exists as green monomers (emission 530 nm). Mitochondria (0.5 mg/ml) were incubated with 2 μM JC-1 in respiration buffer with and without 1 μM FCCP for 20 min at 37 °C, and the red/green fluorescence ratio was determined.

NO-dependent control of respiration

The effect of exogenous NO on mitochondrial respiration was investigated using a closed dual-chamber oxygraph respirometer (Oroboros, Innsbruck, Austria) with chamber stoppers modified to house a NO sensor (ISO-NOP, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, U.S.A.) for simultaneous measurement of O2 and NO concentrations [25]. The O2 sensor signal, calibrated in 100% air-equilibrated respiration buffer, was converted into μM by the Oroboros DatLab software using the O2 solubility of the buffer and the daily barometric pressure. The NO sensor was calibrated with the fast releasing NO donor PROLI NONOate (t1/2=1.3 s) over a concentration range of 1.25–5.0 μM at low O2 levels. Sensor signal in nA was recorded with a free radical analyser (Apollo 4000, WPI, Sarasota, FL, U.S.A.) and converted into μM NO using the generated NO calibration curve.

Mitochondria (0.5 mg/ml) were injected into air-equilibrated respiration buffer (∼200 μM O2), and succinate/rotenone (15 mM/5 μM) and ADP (0.5 mM) were added to initiate state 3 respiration. After a stable baseline respiration rate was obtained, the NO donor PAPA NONOate (5 μM, t1/2=15 min) was added at 160 μM O2 (∼80% O2 saturation), which resulted in NO release and a progressive inhibition of respiration (see Figure 5A). NO traces were corrected for baseline and aligned with the corresponding O2 traces in order to plot O2 consumption rates, calculated as derivatives of the O2 concentration against time traces, and normalized to the maximum respiration rate as a function of NO concentration (see Figure 5B) [16].

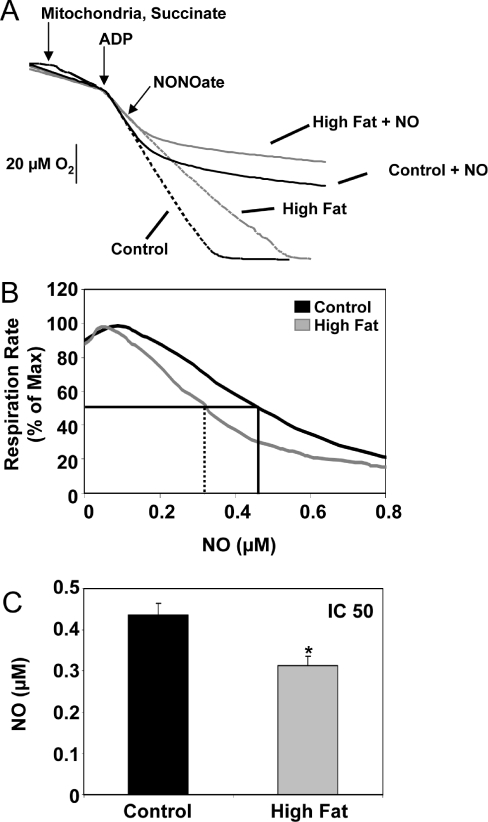

Figure 5. Effect of HFD on NO-dependent inhibition of mitochondrial respiration.

(A) A representative respiration experiment using mitochondria (0.5 mg/ml) from liver of control (black lines) and HFD (grey lines) mice in the presence of succinate/rotenone (15 mM/5 μM) and ADP (0.5 mM). Oxygen traces are shown in the presence of PAPA NONOate (5.0 μM, solid lines), added to the chamber at 80% O2 (at the arrow) and in its absence (dotted lines). Note that there was no difference in the rate and amount of NO produced between groups (results not shown). (B) Representative traces of respiration rate, % of maximum, as a function of NO concentration using mitochondria from liver of control (black) and HFD (grey) mice. Both O2 and NO concentrations are measured simultaneously for the entire duration of each experimental run. (C) The concentration of NO that causes a 50% decrease in mitochondrial respiration rate (i.e. IC50) for control and HFD groups is shown. Results obtained from traces shown in (B) (control, black line, IC50=solid line and HFD, grey line, IC50=dashed line). Values are expressed as the means±S.E.M. for six pairs of mice. *P<0.05, compared with control.

Statistics

Values are reported as means±S.E.M. for 3–6 animals per group. Significant differences (P<0.05) between control and HFD groups were obtained using Student's paired t test.

RESULTS

Feeding a HFD causes NASH

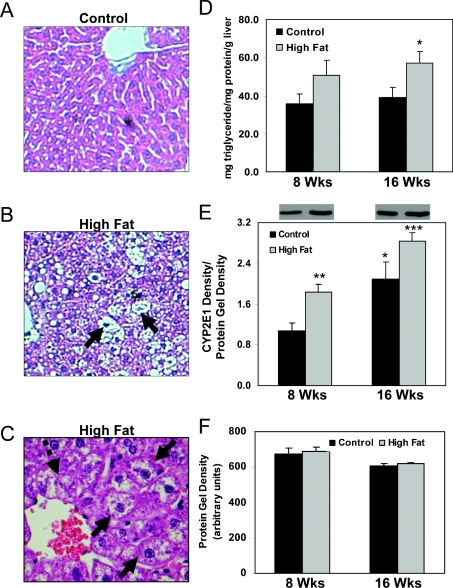

Mice were fed a control diet or HFD in a pair-fed isocaloric fashion for 8 or 16 weeks. Livers from mice on the control diet exhibited no pathology (Figure 1A). These findings are in agreement with those from previous studies conducted by our laboratories using the same control liquid diet [17]. In contrast, livers from mice fed a HFD showed an accumulation of macro- and micro-vesicular fat at both the 8 (results not shown) and 16 week time points (Figure 1B), which was associated with increased liver triacylglycerol content (Figure 1D) and CYP2E1 protein (Figure 1E) as compared with controls. Steatosis was accompanied by hepatocyte ballooning and Mallory bodies in zone 3 of the liver lobule (Figure 1C), which are hallmark features of NASH. These results are consistent with earlier observations from Lieber et al. [21], who reported the development of NASH-like features in rats fed the same HFD.

Figure 1. Effect of HFD on liver histology, triacylglycerol measurements and CYP2E1 protein levels.

Representative liver sections from mice maintained for 16 weeks on control (A, 20×) or a HFD (B, 20× and C, 40×). (C) Ballooned hepatocytes (three solid arrows) and Mallory bodies (one broken arrow) were observed in zone 3 of HFD-fed mouse livers. (D) Quantification of liver triacylglycerol content. P=0.07, compared with control at 8 weeks; *P<0.05, compared with control at 16 weeks. (E) Quantification of CYP2E1 protein levels. Representative Western blots from each group are shown above the bar graph in (E). Levels of immunoreactive CYP2E1 protein were normalized to total protein run on duplicate gels stained with SyproRuby protein stain (Invitrogen). *P<0.05, compared with control at 8 weeks; **P<0.01, compared with control at 8 weeks; ***P<0.01, compared with HFD at 8 weeks. (F) Quantification of total protein on duplicate protein-stained gels used for CYP2E1 Western blots. Note there were no differences in total protein between control and HFD groups. Values represent the means±S.E.M. for 4–6 pairs of mice.

Feeding a HFD increases liver hypoxia

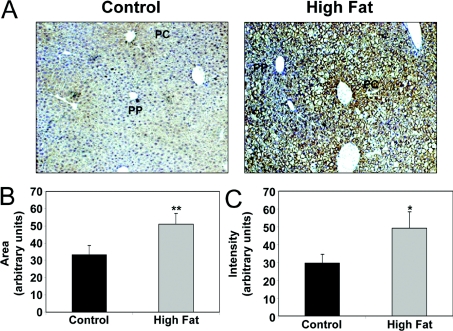

Hypoxia has been implicated as a causative factor in alcohol-induced fatty liver disease [4,5]; however, whether hypoxia is also associated with NAFLD and NASH is not known. The hypoxia marker pimonidazole was used to determine the extent of liver hypoxia. Figure 2(A) shows the patterns of pimonidazole adduct formation (brown) against a haematoxylin nuclear counterstain (blue) in representative control and HFD livers at 16 weeks. Under normal conditions the most hypoxic region of the liver is the pericentral region or zone 3. HFD feeding for 16 weeks increased pimonidazole binding in zone 3 and extended staining into the midzonal and periportal regions when compared with control livers (Figure 2A). Liver hypoxia was also increased by feeding a HFD for 8 weeks, although to a lesser extent (results not shown). The area of pimonidazole staining in livers from HFD mice was significantly increased by 40% over that observed in controls (Figure 2B). Similarly, a HFD significantly increased the intensity of labelled cells compared with controls by approx. 60% (Figure 2C). These results are indicative of increased liver hypoxia in mice fed a HFD.

Figure 2. Effect of HFD on liver hypoxia.

(A) Representative photomicrographs depicting patterns of pimonidazole adduct formation (brown) against a haematoxylin-nuclear counterstain (blue) in liver sections of mice fed either a control diet or HFD for 16 weeks. Increased staining for the pimonidazole adducts demonstrates increased tissue hypoxia in the HFD group as compared with control. Image analysis demonstrated increased area (B) and intensity (C) of pimonidazole adducts in liver from HFD group compared with control. Note: PP, periportal or zone 1 region of liver lobule; PC, pericentral or zone 3 region of liver lobule. Values represent the means±S.E.M. for three pairs of mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, compared with control.

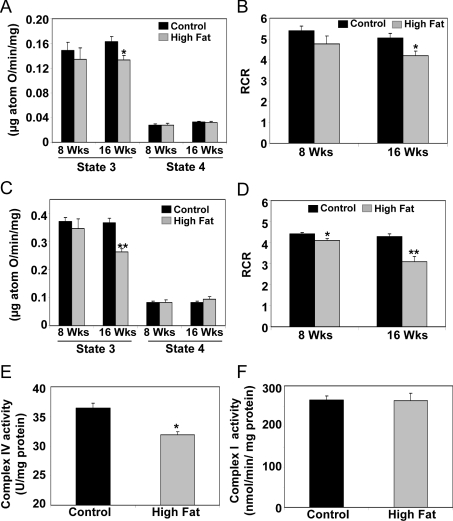

Feeding a HFD causes mitochondrial dysfunction

Feeding a HFD resulted in alterations in mitochondrial function (Figure 3). While respiration was largely unaffected by feeding a HFD for 8 weeks, state 3 respiration was significantly decreased at 16 weeks with a slight increase in state 4 respiration (Figures 3A and 3C). This decrease in state 3 respiration translated into a significant decrease in the RCR (Figures 3B and 3D). Moreover, feeding a HFD for 16 weeks significantly decreased complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) activity (Figure 3E), whereas complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) activity (Figure 3F) was unaffected by feeding a HFD. There was no difference in citrate synthase activity, a commonly used mitochondrial marker enzyme, between groups at 16 weeks (control, 0.845±0.05 and HFD, 0.804±0.027 μmol/min per mg of protein, P=0.39). No change in citrate synthase activity indicates that the higher levels of hepatic triacylglycerol in the HFD group had no effect on the overall content or purity of isolated mitochondria used for functional assays.

Figure 3. Effect of HFD on respiratory rates, RCR and respiratory complex activities in liver mitochondria.

State 3 and 4 respiration was measured and the RCR was determined using either glutamate/malate (A and B) or succinate (C and D) as oxidizable substrates in freshly isolated mitochondria. (E) Complex IV activity was measured by monitoring the rate of oxidation of fully reduced cytochrome c at 550 nm. (F) Complex I activity was assessed by measuring the rotenone-sensitive rate of oxidation of NADH initiated by coenzyme Q1. Complex I and IV activities were measured at the 16 week feeding time point. Values are expressed as the means±S.E.M. for six pairs of mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, compared with control.

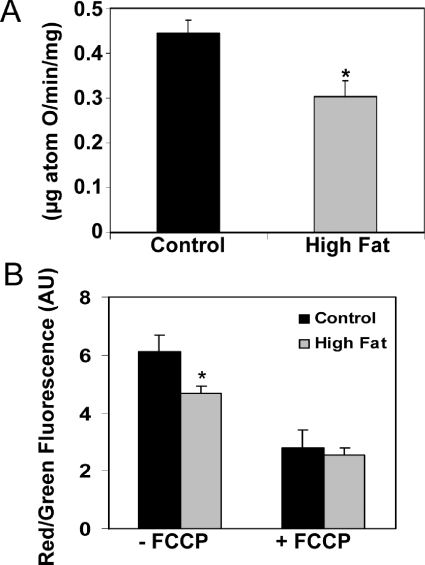

Mitochondrial function was further evaluated by assessing uncoupled respiration and the mitochondrial membrane potential. At 16 weeks, uncoupled respiration, i.e. respiration in the presence of FCCP, was significantly decreased in mitochondria from HFD mice compared with controls (Figure 4A). Feeding a HFD for 16 weeks also decreased the red/green fluorescence ratio of the membrane potential sensitive dye JC-1, indicating impairment in the ability of mitochondria to fully develop a membrane potential (Figure 4B). There was no difference in JC-1 fluorescence between control and HFD groups when mitochondria were uncoupled with FCCP, indicating that the HFD-dependent decrease was not due to inherent differences in mitochondria that would have affected baseline measurements or uptake of JC-1. Taken together, these data suggest that feeding a HFD causes mitochondrial dysfunction at the level of the respiratory chain.

Figure 4. Effect of HFD on uncoupler-stimulated respiration and the membrane potential in liver mitochondria.

(A) Oxygen consumption was measured in freshly isolated mitochondria in the presence of succinate/rotenone (15 mM/5 μM) and the uncoupler FCCP (1 μM). (B) Membrane potential was reported by the red/green fluorescence ratio of JC-1 in freshly isolated coupled (−FCCP) and uncoupled (+FCCP) mitochondria. Both uncoupled respiration and membrane potential are shown for the 16 week feeding time point. Values are expressed as the means±S.E.M. of six pairs of mice. *P<0.05, compared with control. AU, absorbance units.

HFD increases the sensitivity of mitochondrial respiration to inhibition by NO

The effect of a HFD on NO-dependent inhibition of liver mitochondria respiration was assessed with high-resolution respirometry. Oxygen traces from a representative experiment are shown in Figure 5(A). After mitochondria and succinate/rotenone were added to the respiration chamber, state 3 respiration was initiated by the addition of ADP (0.5 mM). When the O2 concentration reached approximately 160 μM (i.e. 80% of the initial O2 concentration), the NO donor PAPA NONOate (5 μM) was added to the respiration chamber (Figure 5A). In the absence of the NO donor, a constant rate of O2 consumption was observed until O2 was depleted (Figure 5A, dashed lines), whereas addition of the NO donor resulted in inhibition of mitochondrial respiration in both control and HFD groups (Figure 5A, solid lines). It should be pointed out that respiration rates were restored to pre-NO rates in both groups upon the addition of the NO scavenger oxyhaemoglobin (results not shown, and reported in [16,17]). Additionally, there was no difference in NO production from PAPA NONOate in mitochondrial suspensions from control and HFD groups, indicating no difference in NO consumption between groups (results not shown).

To determine whether there was a difference in the sensitivity of mitochondrial respiration to inhibition by NO between control and HFD groups, respiration rate, calculated as the instantaneous derivative of the O2 concentration versus time traces shown in Figure 5(A), was plotted as a function of NO concentration, which was recorded following the bolus addition of PAPA NONOate with the NO sensor (not shown) (Figure 5B). There was no significant difference in NO-dependent inhibition of respiration between liver mitochondria from control and HFD groups at 8 weeks (results not shown). In contrast, at 16 weeks there was a statistically significant increase in the degree of NO-dependent inhibition of respiration in HFD mitochondria compared with controls (Figure 5B). The NO concentration required to cause a 50% inhibition in respiration (i.e. IC50) fell significantly from 0.436±0.029 μM in control mitochondria to 0.314±0.022 μM in HFD mitochondria (P=0.04) (Figure 5C).

HFD increases iNOS protein and 3-NT levels in liver

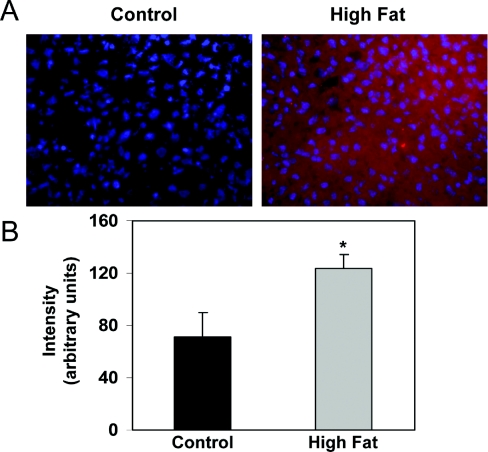

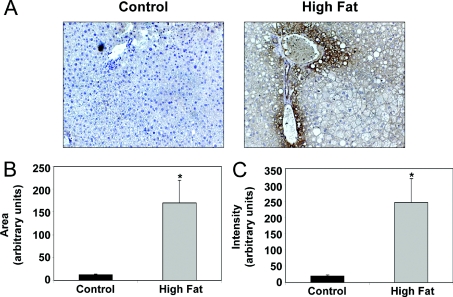

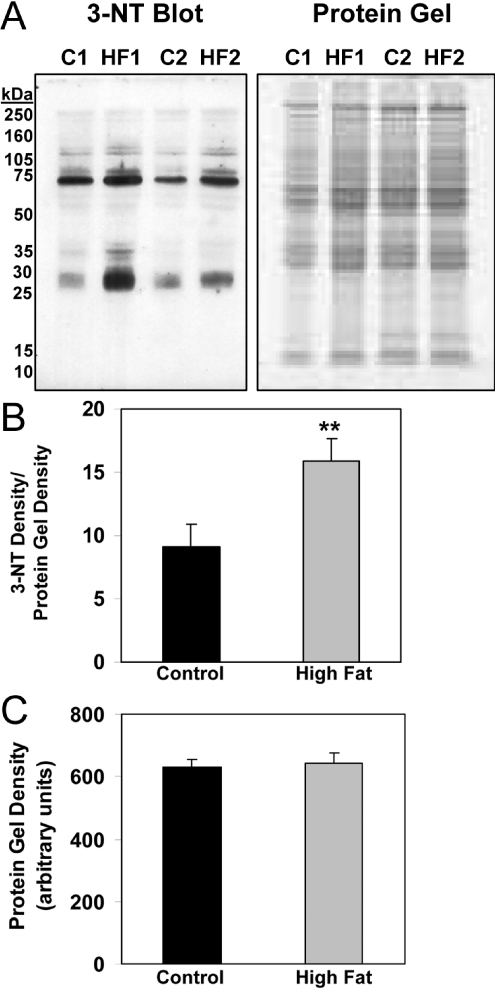

NO-dependent inhibition of respiration has been shown to increase superoxide (O2●−) production from the respiratory chain and in turn could lead to greater levels of peroxynitrite (ONOO−) formation [26]. This oxidant can modify proteins in the respiratory chain, leading to decreased activity [27]. Interestingly, nitration of tyrosine has been reported to be increased in the livers of NASH patients [28] and ob/ob mice with severe steatosis [29]. Similarly, iNOS levels are increased in liver of ob/ob mice; however, the impact of a HFD on hepatic iNOS expression is not known. While iNOS protein was detected in control livers, significantly higher levels of iNOS protein were detected in livers of HFD mice at 16 weeks (Figure 6). In concert, we examined the effect of feeding a HFD on 3-NT formation. A small amount of 3-NT was detected in livers from control animals, whereas there was significant 3-NT staining in the livers of mice fed the HFD for 16 weeks (Figure 7A). Both the area and intensity of 3-NT staining were significantly increased in response to a HFD compared with control (Figures 7B and 7C). Interestingly, the gradient of 3-NT immunoreactivity parallels that observed for the hypoxia gradient in vivo (Figure 2), suggesting a link between hypoxia and increased nitrative stress. Moreover, as predicted, 3-NT levels were elevated within mitochondrial proteins isolated from livers of the HFD group compared with controls (Figure 8).

Figure 6. Effect of HFD on iNOS protein levels in liver.

(A) Representative photomicrographs demonstrating the extent of iNOS staining (red) against a DAPI-nuclear counterstain (blue) in liver sections of mice fed either a control or HFD for 16 weeks. Increased red staining shows elevated tissue levels of iNOS protein in the HFD group as compared with the control. Image analysis demonstrated increased intensity (B) of iNOS staining in liver from HFD groups compared with control. There was no statistically significant difference in the area of iNOS staining between control and HFD groups (results not shown). Values represent the means±S.E.M. for four pairs of mice. *P<0.05, compared with control.

Figure 7. Effect of HFD on 3-NT levels in liver.

(A) Representative photomicrographs depicting patterns of 3-NT staining (brown) against a haematoxylin nuclear counterstain (blue) in liver sections of mice fed either a control diet or HFD for 16 weeks. Increased brown staining demonstrates increased tissue 3-NT levels in the HFD group as compared with control. Image analysis demonstrated increased area (B) and intensity (C) of 3-NT staining in liver from the HFD group compared with control. Values represent the means±S.E.M. for five pairs of mice. *P<0.05, compared with control.

Figure 8. Effect of HFD on 3-NT levels in liver mitochondrial proteins.

(A) Representative Western blots depicting the extent of nitration in mitochondrial proteins from mice fed either a control or HFD for 16 weeks. Representative Western blots for two separate pairs of mice are shown along with their duplicate stained total protein gels. (B) Quantification of 3-NT levels in mitochondrial proteins. Levels of nitrated proteins were normalized to total protein. (C) Quantification of total protein was performed on duplicate gels, stained with SyproRuby protein stain, used for 3-NT Western blots. Note there were no differences in total protein between control and HFD groups. Values represent the means±S.E.M. for three pairs of mice. **P<0.01, compared with control.

DISCUSSION

Elucidating the specific molecular mechanisms responsible for NAFLD and NASH has been slow because of the limitations associated with existing experimental animal models [30]. Currently, the most widely used models to study NAFLD are genetically altered rodent models, e.g. the obese ob/ob mouse and fa/fa rat. While these models, with defects in leptin physiology, develop severe steatosis, NASH does not occur unless animals are challenged with endotoxin [31] or fed a methionine/choline-deficient diet [32]. Similarly, even though wild-type mice fed a methionine/choline-deficient diet develop histologic markers of NASH, this model induces an extreme nutritional deficiency not observed in NASH patients, thus limiting mechanistic comparisons. To address this problem, Lieber et al. [21] developed an experimental model in which rats were fed a HFD that contains 71% total calories as fat. Rats fed on this diet for 3 weeks developed several of the key features of NAFLD, including steatosis, inflammation, and increased CYP2E1 protein levels, whereas hepatocyte ballooning and Mallory bodies were not observed.

In the present study, we adapted this long-term HFD feeding model to C57BL/6 mice to investigate the role of hypoxia and bioenergetic defects in the development of NAFLD and NASH. In the current study, feeding mice a HFD ad libitum produces macro- and micro-steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, and Mallory bodies, which are accompanied by increased liver triacylglycerol concentrations and CYP2E1 protein levels (Figure 1). It is likely that feeding a HFD increases CYP2E1 levels in response to elevated liver concentrations of ketones and fatty acids that serve as inducers and substrates of P450 enzymes [33]. Importantly, hepatic CYP2E1 levels are increased in NASH patients [34]. These observations demonstrate that feeding wild-type mice a HFD reproduces the important histologic and biochemical features observed in NASH patients, strengthening the rationale for using a self-administration (i.e. voluntary) dietary feeding approach to study the molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and NASH.

Accompanying these histologic features of NASH were significant defects in mitochondrial function. In the present study, feeding a HFD for 16 weeks significantly decreased mitochondrial state 3 respiration and the RCR. Cytochrome c oxidase activity and uncoupler-stimulated respiration were also decreased by a HFD (Figures 3 and 4). These observations suggest that chronic exposure to a HFD damages mitochondria such that the rate at which mitochondria synthesize ATP via oxidative phosphorylation may be depressed, resulting in a bioenergetic defect. Importantly, our results support reports of decreased respiratory complex activities in liver biopsy samples taken from NASH patients compared with normal liver [12]. In contrast, in liver mitochondria from ob/ob mice, state 3 respiration and respiratory control are only impaired when substrate is limited to the respiratory chain [9]. On the basis of this, we propose that the dietary approach used in the current study more accurately models the molecular changes that occur in human disease pathogenesis.

These new findings raise an important point with regard to the need to translate what appears to be a modest change in respiratory chain function to the pathobiology of NASH. While it is apparent that the mitochondrial depolarization observed in the HFD group cannot be directly linked to a defect in cytochrome c oxidase, it is possible that alterations in mitochondrial thresholds of respiratory chain enzymes occurred in response to the metabolic stress induced by chronic exposure to a HFD. Specifically, it is likely that under conditions of pathological stress, in this instance NASH, the bioenergetic demands on mitochondria are increased for repair and detoxification, while at the same time the threshold capacity of the respiratory chain complexes is limited. In support of this concept, we and others have shown a similar decrease in state 3 respiration (approximately 25%) following chronic alcohol consumption, which is associated with the inability of mitochondria to meet the energetic demands of the tissue [15,35]. For example, it has been shown that decreased activity in respiratory chain complexes results in much lower ATP synthesis in the liver [35]. Importantly, this may be connected directly to pathology because the inability to maintain sufficient ATP levels has been linked to increased hepatocyte death when steatotic hepatocytes are placed under low O2 partial pressures [36]. It is proposed that the same holds true in the present study, as we observed increased liver injury coupled with hypoxia in the HFD group. Therefore, when ATP synthesis is depressed this would increase the susceptibility of hepatocytes to cell death, especially when ATP needs are increased acutely in the NASH patient. Moreover, this is important as a loss in the capacity for maintenance of hepatic ATP levels may ultimately predispose liver to permanent damage, due to a depression in the anabolic processes responsible for replacing damaged and/or lost cellular components.

One consequence of impaired mitochondrial functioning in the HFD group may be perturbations in the physiological O2 gradient within the liver between the portal and central vein circulations leading to hypoxia. Specifically, we postulate that the inefficient mitochondria damaged by chronic exposure to a HFD will be required to have increased O2 consumption in vivo to maintain adequate ATP levels in the liver tissue. Previous studies in experimental models of alcoholic fatty liver disease have shown induction of a ‘hypermetabolic state’ and enhanced tissue hypoxia in response to increased O2 uptake coupled to ethanol oxidation [37]. By analogy, chronic exposure to a HFD can also be expected to induce a ‘hypermetabolic state’ in the liver due to continued delivery of free fatty acids to damaged mitochondria. As a result of these events, damaged mitochondria and increased free fatty acid load, the O2 gradient within the liver lobule would be steepened due to increased mitochondrial O2 consumption in upstream periportal hepatocytes (i.e. O2-rich cells surrounding the portal vein), placing the downstream pericentral hepatocytes (i.e. O2-poor cells surrounding the central vein) under a more severe degree of hypoxia, as shown in Figure 2.

An association between hypoxia and steatotic liver injury is strengthened by observations of an inverse correlation between the degree of steatosis and blood flow in the hepatic microcirculation [38]. Accordingly, as fat accumulates in the cytosol, this increases hepatocyte size (i.e. ballooning), which will reduce the size of the hepatic sinusoid and reduce blood flow, thereby rendering downstream hepatocytes hypoxic. This scenario is likely in the present study as ballooned hepatocytes were observed in the liver from HFD mice. Indeed, several studies have shown that steatotic livers have a significantly reduced tolerance to ischemia-reperfusion injury following transplantation, which can be linked to bioenergetic defects and hypoxic stress [39].

Interestingly, the interaction of the signalling molecule NO with the mitochondrial respiratory chain has been implicated as an important physiological indicator for how cells respond to hypoxic stress [19,40]. Specifically, NO reversibly inhibits mitochondrial respiration at cytochrome c oxidase via competition with O2 at the haem-binuclear center of the enzyme [41,42]. It has been proposed that one function of this ‘NO-cytochrome c oxidase signalling’ interaction is to regulate O2 gradients within cells and tissues via limiting O2 consumption in actively respiring mitochondria [43]. Theoretically, this would have the effect of extending O2 gradients within tissues and preventing hypoxia. In the present study, we observed that NO was a more potent inhibitor of respiration in mitochondria isolated from livers of HFD-fed animals as compared with controls. Mitochondria isolated from HFD mice required 25% less NO to obtain 50% inhibition of respiration compared with the control group (Figure 5), which is consistent with our previous studies in the alcohol hepatotoxicity model [16,17]. On the basis of this, one might predict that this increased sensitivity of mitochondrial respiration to inhibition by NO would lead to increased local O2 partial pressure and concomitantly decreased hypoxia due to inhibition of mitochondrial O2 consumption. However, we did not observe this, but found enhanced hypoxia in the pericentral region of liver from HFD-fed animals, presumably in response to decreased mitochondrial efficiency in damaged mitochondria.

One possible explanation for the inability of increased NO sensitivity of mitochondria to attenuate liver hypoxia during pathological states could be related to induction of additional NO targets or ‘sinks’ in hepatocytes, such that NO is unable to target mitochondria and inhibit respiration even though the intrinsic sensitivity of mitochondrial respiration to inhibition by NO is increased by chronic exposure to a HFD. For example, increased free fatty acid delivery to mitochondria is predicted to increase O2 consumption and stimulates O2●− production as a consequence of increased reduction of the respiratory chain complexes [44]. Accordingly, increased formation of O2●− in response to increased fatty acid load, impaired electron transport, and/or increased CYP2E1 in the HFD group would effectively decrease free NO concentrations in the cell via enhanced formation of ONOO−, as shown by increased 3-NT in whole liver and within the mitochondrial compartment. This may be especially pertinent, as the distribution of 3-NT paralleled that of hypoxia in the pericentral region of the liver. Erusalimsky and Moncada [18] have also suggested that one consequence of NO-mediated inhibition of respiration is to divert O2 to non-mitochondrial O2-requiring targets, which themselves could be increased in response to hypoxia and/or other pathological conditions. One potential target for NO and O2 may be CYP2E1, which was induced by a HFD and known to be localized to the pericentral zone of the liver. The interaction of NO with CYPs (cytochrome P450s) would result in decreased free NO concentrations and essentially block the ability of NO to increase local O2 partial pressure in vivo. This concept is supported by studies demonstrating that L-arginine infusion improves hepatic microcirculation and oxyhaemoglobin status, whereas these parameters are worsened in steatotic liver when NO production is blocked by infusion of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester [38].

Another issue of relevance to this study concerns the O2 partial pressure dependence of O2●− and NO production in tissues in vivo, especially during hypoxia. Recent studies have shown that ROS/RNS generation is O2 dependent [45,46], but it is important to note that O2 is present under conditions of hypoxia and that nitration mechanisms can arise from O2-independent mechanisms such as the metabolism of nitrite by peroxidases [47]. There have been a number of measurements of protein modification of ROS/RNS under conditions associated with hypoxia, which can be linked to not only the generation of reactive species but also stability and turnover of the protein adducts [48,49]. This concept is based on the view that there is a combination of effects that lead to the accumulation of post-translationally modified proteins by ROS/RNS-dependent mechanisms, which is supported by the present study. The key events that contribute to the accumulation of modified proteins are the increased localized production of ROS in the mitochondrion, which is enhanced as the respiratory chain complexes become more reduced and when tissue oxygenation decreases. Similarly, another critical aspect to this is that many of the ROS/RNS-metabolizing enzymes or processes are energy requiring, and their efficiency will therefore be decreased during hypoxia. Finally, the repair mechanisms that either remove specific modifications such as nitration or process damaged proteins are also energy requiring. Taken together, this combination of effects is predicted to result in a higher rate of formation of oxidized/modified proteins and a lower rate of protein turnover.

In summary, previous studies have proposed that the interaction of NO with cytochrome c oxidase is a regulated and physiologically relevant pathway that functions to control ROS formation for redox signalling and maintain O2 gradients in tissues [19]. However, during pathologic conditions, such as NAFLD and NASH, a loss in control of this pathway occurs in response to impaired mitochondrial function. We propose that while NO-dependent inhibition of respiration may be an adaptive and protective mechanism in healthy tissues under normoxic or mildly hypoxic conditions, this function of NO is maladaptive in pathologic conditions associated with damaged mitochondria and/or low O2 concentrations. Specifically, damaged mitochondria exposed to low O2 will be under a greater reductive stress and it is under these conditions that the interaction of NO with mitochondria may be pathologic, because ROS and RNS formation is enhanced and ATP production is compromised [19]. Therefore, we propose that there is a failure in the ability of NO to regulate respiration in vivo when mitochondria are damaged, which results in a dysregulation of O2 gradients in steatotic liver. The consequence of this is enhanced hypoxia that, when coupled with mitochondrial dysfunction, may place hepatocytes under bioenergetic and reductive stress, which contributes to the pathogenesis of liver disease in the NASH patient.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Tim R. Nagy, University of Alabama at Birmingham, for helpful information on diets and husbandry issues, Dr Alvaro G. Estevez, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY, U.S.A., for kindly providing the 3-NT antiserum, and Dr Balu K. Chacko, Dr Michelle Fanucchi and Ms Telisha Millender-Swain, University of Alabama at Birmingham, for assistance in immunohistochemistry and immunofluoresence experiments.

FUNDING

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) [grant numbers AA13395 (V. D. U.), AA15172 (S. M. B.) and DK73775 (S. M. B.)] and by NIH-funded University of Alabama at Birmingham Clinical Nutrition Research Center [grant number DK56336, pilot project to S. M. B.)]. A. L. K. is supported by a NIH Research Supplement to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research linked to parent grant AA15172.

References

- 1.Farrell G. C., Larter C. Z. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:S99–S112. doi: 10.1002/hep.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruhl C. E., Everhart J. E. Epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver. Clin. Liver Dis. 2004;8:501–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papandreou D., Rousso I., Mavromichalis I. Update on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children. Clin. Nutr. 2007;26:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arteel G. E., Iimuro Y., Yin M., Raleigh J. A., Thurman R. G. Chronic enteral ethanol treatment causes hypoxia in rat liver tissue in vivo. Hepatology. 1997;25:920–926. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arteel G. E., Raleigh J. A., Bradford B. U., Thurman R. G. Acute alcohol produces hypoxia directly in rat liver tissue in vivo: role of Kupffer cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 1996;271:G494–G500. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.3.G494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savransky V., Bevans S., Nanayakkara A., Li J., Smith P. L., Torbenson M. S., Polotsky V. Y. Chronic intermittent hypoxia causes hepatitis in a mouse model of diet-induced fatty liver. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G871–G877. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00145.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jouet P., Sabate J. M., Maillard D., Msika S., Mechler C., Ledoux S., Harnois F., Coffin B. Relationship between obstructive sleep apnea and liver abnormalities in morbidly obese patients: a prospective study. Obes. Surg. 2007;17:478–485. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mantena S. K., King A. L., Andringa K. K., Eccleston H. B., Bailey S. M. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of alcohol- and obesity-induced fatty liver diseases. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2008;44:1259–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavin K. D., Yang S., Lin H. Z., Chatham J., Chacko V. P., Hoek J. B., Walajtys-Rode E., Rashid A., Chen C. H., Huang C. C., Wu T. C., Lane M. D., Diehl A. M. Obesity induces expression of uncoupling protein-2 in hepatocytes and promotes liver ATP depletion. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:5692–5700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caldwell S. H., Swerdlow R. H., Khan E. M., Iezzoni J. C., Hespenheide E. E., Parks J. K., Parker W. D., Jr Mitochondrial abnormalities in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 1999;31:430–434. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawahara H., Fukara M., Tsuchishima M., Takase S. Mutation of mitochondrial DNA in livers from patients with alcoholic hepatitis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:S54–S60. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez-Carreras M., Del Hoyo P., Martin M. A., Rubio J. C., Martin A., Castellano G., Colina F., Arenas J., Solis-Herruzo J. A. Defective hepatic mitochondrial respiratory chain in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2003;38:999–1007. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cahill A., Stabley G. J., Wang X., Hoek J. B. Chronic ethanol consumption causes alterations in the structural integrity of mitochondrial DNA in aged rats. Hepatology. 1999;30:881–888. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel V. B., Cunningham C. C. Altered hepatic mitochondrial ribosome structure following chronic ethanol consumption. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;398:41–50. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkatraman A., Landar A., Davis A. J., Chamlee L., Sanderson T., Kim H., Page G., Pompilius M., Ballinger S., Darley-Usmar V., Bailey S. M. Modification of the mitochondrial proteome in response to the stress of ethanol-dependent hepatotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:22092–22101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkatraman A., Shiva S., Davis A. J., Bailey S. M., Brookes P. S., Darley-Usmar V. M. Chronic alcohol consumption increases the sensitivity of rat liver mitochondrial respiration to inhibition by nitric oxide. Hepatology. 2003;38:141–147. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venkatraman A., Shiva S., Wigley A., Ulasova E., Chhieng D., Bailey S. M., Darley-Usmar V. M. The role of iNOS in alcohol-dependent hepatotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:565–73. doi: 10.1002/hep.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erusalimsky J. D., Moncada S. Nitric oxide and mitochondrial signaling: from physiology to pathophysiology. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27:2524–2531. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiva S., Oh J. Y., Landar A. L., Ulasova E., Venkatraman A., Bailey S. M., Darley-Usmar V. M. Nitroxia: the pathological consequence of dysfunction in the nitric oxide-cytochrome c oxidase signaling pathway. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2005;38:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brookes P. S., Zhang J., Dai L., Zhou F., Parks D. A., Darley-Usmar V. M., Anderson P. G. Increased sensitivity of mitochondrial respiration to inhibition by nitric oxide in cardiac hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001;33:69–82. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieber C. S., Leo M. A., Mak K. M., Xu Y., Cao Q., Ren C., Ponomarenko A., DeCarli L. M. Model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;79:502–509. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wharton D. C., Tragoloff A. Cytochrome oxidase from beef heart mitochondria. Methods Enzymol. 1967;10:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramachandran A., Levonen A. L., Brookes P. S., Ceaser E., Shiva S., Barone M. C., Darley-Usmar V. Mitochondria, nitric oxide, and cardiovascular dysfunction. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2002;33:1465–1474. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reers M., Smith T. W., Chen L. B. J-aggregate formation of a carbocyanine as a quantitative fluorescent indicator of membrane potential. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4480–4486. doi: 10.1021/bi00232a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doeller J. E., Isbell T. S., Benavides G., Koenitzer J., Patel H., Patel R. P., Lancaster J. R., Jr, Darley-Usmar V. M., Kraus D. W. Polarographic measurement of hydrogen sulfide production and consumption by mammalian tissues. Anal. Biochem. 2005;341:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Packer M. A., Porteous C. M., Murphy M. P. Superoxide production by mitochondria in the presence of nitric oxide forms peroxynitrite. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 1996;40:527–534. doi: 10.1080/15216549600201103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radi R., Cassina A., Hodara R. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite interactions with mitochondria. Biol. Chem. 2002;383:401–409. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanyal A. J., Campbell-Sargent C., Mirshahi F., Rizzo W. B., Contos M. J., Sterling R. K., Luketic V. A., Shiffman M. L., Clore J. N. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: association of insulin resistance and mitochondrial abnormalities. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1183–1192. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Ruiz I., Rodriguez-Juan C., Diaz-Sanjuan T., Martinez M. A., Munoz-Yague T., Solis-Herruzo J. A. Effects of rosiglitazone on the liver histology and mitochondrial function in ob/ob mice. Hepatology. 2007;46:414–423. doi: 10.1002/hep.21687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koteish A., Mae Diehl A. Animal models of steatohepatitis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2002;16:679–690. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang S. Q., Lin H. Z., Lane M. D., Clemens M., Diehl A. M. Obesity increases sensitivity to endotoxin liver injury: implications for the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:2557–2562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahai A., Malladi P., Pan X., Paul R., Melin-Aldana H., Green R. M., Whitington P. F. Obese and diabetic db/db mice develop marked liver fibrosis in a model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: role of short-form leptin receptors and osteopontin. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G1035–G1043. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00199.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lieber C. S. CYP2E1: from ASH to NASH. Hepatol. Res. 2004;28:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalasani N., Gorski J. C., Asghar M. S., Asghar A., Foresman B., Hall S. D., Crabb D. W. Hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 activity in nondiabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2003;37:544–550. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham C. C., Coleman W. B., Spach P. I. The effects of chronic ethanol consumption on hepatic mitochondrial energy metabolism. Alcohol Alcohol. 1990;25:127–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a044987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey S. M., Cunningham C. C. Effect of dietary fat on chronic ethanol-induced oxidative stress in hepatocytes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1999;23:1210–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bradford B. U., Rusyn I. Swift increase in alcohol metabolism (SIAM): understanding the phenomenon of hypermetabolism in liver. Alcohol. 2005;35:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ijaz S., Yang W., Winslet M. C., Seifalian A. M. The role of nitric oxide in the modulation of hepatic microcirculation and tissue oxygenation in an experimental model of hepatic steatosis. Microvasc. Res. 2005;70:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caraceni P., Domenicali M., Vendemiale G., Grattagliano I., Pertosa A., Nardo B., Morselli-Labate A. M., Trevisani F., Palasciano G., Altomare E., Bernardi M. The reduced tolerance of rat fatty liver to ischemia reperfusion is associated with mitochondrial oxidative injury. J. Surg. Res. 2005;124:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooper C. E., Giulivi C. Nitric oxide regulation of mitochondrial oxygen consumption II: molecular mechanism and tissue physiology. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2007;292:C1993–C2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00310.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown G. C. Nitric oxide regulates mitochondrial respiration and cell functions by inhibiting cytochrome oxidase. FEBS Lett. 1995;369:136–139. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00763-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cleeter M. W., Cooper J. M., Darley-Usmar V. M., Moncada S., Schapira A. H. Reversible inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, by nitric oxide. Implications for neurodegenerative diseases. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:50–54. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas D. D., Liu X., Kantrow S. P., Lancaster J. R., Jr The biological lifetime of nitric oxide: implications for the perivascular dynamics of NO and O2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:355–360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011379598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.St-Pierre J., Buckingham J. A., Roebuck S. J., Brand M. D. Topology of superoxide production from different sites in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44784–44790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffman D. L., Salter J. D., Brookes P. S. Response of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation to steady-state oxygen tension: implications for hypoxic cell signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;292:H101–H108. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00699.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson M. A., Baumgardner J. E., Good V. P., Otto C. M. Physiological and hypoxic O2 tensions rapidly regulate NO production by stimulated macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2008;294:C1079–C1087. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00469.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schopfer F. J., Baker P. R., Freeman B. A. NO-dependent protein nitration: a cell signaling event or an oxidative inflammatory response? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arteel G. E., Kadiiska M. B., Rusyn I., Bradford B. U., Mason R. P., Raleigh J. A., Thurman R. G. Oxidative stress occurs in perfused rat liver at low oxygen tension by mechanisms involving peroxynitrite. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;55:708–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Venkatraman A., Landar A., Davis A. J., Ulasova E., Page G., Murphy M. P., Darley-Usmar V., Bailey S. M. Oxidative modification of hepatic mitochondria protein thiols: effect of chronic alcohol consumption. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G521–G527. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00399.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]