Abstract

Background and objectives: Only rare cases of concurrent membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis (NCGN) have been reported.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: The authors report the clinical and pathologic findings in 14 patients with MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN.

Results: The cohort consisted of eight men and six women with a mean age of 58.7 yr. ANCA positivity was documented by indirect immunofluorescence or ELISA in all patients. Indirect immunofluorescence was positive in 13 patients (seven P-ANCA, five C-ANCA, one atypical ANCA). ELISA was positive in nine of 10 patients (five MPO-ANCA, three PR3-ANCA, one MPO- and PR3-ANCA). Clinical presentation included heavy proteinuria (mean 24-hr urine protein 6.5 g/d), hematuria, and acute renal failure (mean creatinine 4.4 mg/dl). Pathologic evaluation revealed MGN and NCGN, with crescents involving a mean of 32% of glomeruli. On ultrastructural evaluation, the majority of cases showed stage I or II membranous changes. Follow-up was available for 13 patients, 12 of whom were treated with steroids and cyclophosphamide. At a mean follow-up of 24.3 mo, five patients progressed to ESRD, seven had stabilization or improvement in renal function, and one had worsening renal function. Five patients, including three with ESRD, died during the follow-up period. The only independent predictor of progression to ESRD was serum creatinine at biopsy.

Conclusions: MGN with ANCA-associated NCGN is a rare dual glomerulopathy seen in patients with heavy proteinuria, acute renal failure, and active urine sediment. Prognosis is variable, with 50% of patients reaching endpoints of ESRD or death.

Membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN) is the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome in white adults, accounting for more than one third of cases (1). At the time of presentation, the majority of patients with MGN have preserved renal function (2). Microscopic evaluation of the urine sediment reveals microscopic hematuria in approximately 50% of cases; however, red blood cell casts are not a feature of this disease. Pathologically, MGN is characterized by the formation of subepithelial immune complex deposits with resultant changes to the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), most notably GBM spike formation. Approximately 75% of cases of MGN are thought to represent primary disease, whereas the remaining 25% of cases represent secondary forms of MGN, most commonly related to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), infection (i.e., hepatitis B or C virus), malignancy, or drugs. The natural history of MGN is variable, with approximately one third of patients progressing to ESRD within 10 yr (2).

Pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis (PNCGN) is characterized by glomerular necrosis and crescent formation in the absence of significant intracapillary proliferation and in the presence of no more than a “paucity” of glomerular immune complex deposits. The majority of patients with PNCGN, with or without associated systemic vasculitis, have circulating antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), which have been directly implicated in the pathogenesis of this form of glomerular injury. In contrast to patients with MGN, those with PNCGN typically present with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) and an active urine sediment with red blood cell casts (3,4). PNCGN is an aggressive disease with a 1-yr mortality rate of up to 80% in the absence of immunosuppressive therapy. The prognosis of PNCGN is dramatically improved by immunosuppressive regimens that include corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide (CY).

The occurrence of ANCA-associated NCGN and primary MGN in the same patient is rare, with only a handful of reports in the literature (5–10). Herein, we detail the clinical, pathologic, and outcome data of 14 patients with this rare dual glomerulopathy and review the previously reported cases.

Materials and Methods

Fourteen patients with renal biopsy findings of ANCA-associated NCGN and MGN were identified from the archives of the Nephropathology Laboratory of Columbia University between January 2000 and February 2008. Patients with SLE were excluded because of the potential for a mixed pattern of lupus nephritis to reveal both membranous and crescentic changes, as well as the high incidence of ANCA in patients with SLE (11).

All renal biopsies were processed according to standard techniques for light microscopy (LM), immunofluorescence (IF), and electron microscopy (EM). For each patient, 17 glass slides were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), trichrome, and Jones methenamine silver (JMS). IF was performed on 3-μm cryostat sections using polyclonal FITC-conjugated antibodies to IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, kappa, lambda, fibrinogen, and albumin (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA). IF staining intensity was graded 0 to 3+ on a semiquantitative scale. Ultrastructural evaluation was performed using a JEOL 100S or 1010 electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Patients’ medical records were reviewed for demographics, clinical features of systemic vasculitis, medication history, ANCA specificity, parameters of renal function, treatment, and outcome. The following clinical definitions were applied: renal insufficiency, serum creatinine > 1.2 mg/dl; nephrotic range proteinuria (NRP), 24-h urine protein ≥ 3 g/d; hypoalbuminemia, serum albumin ≤ 3.5 g/dl; nephrotic syndrome, NRP, hypoalbuminemia, and peripheral edema; and hematuria, >5 red blood cells per high power field on microscopic examination of the urinary sediment. The diagnosis of MGN was based on the finding of subepithelial deposits by IF or EM in >10% of the glomerular capillary loops (segmental, 10 to 50%; global, >50%)

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (Chicago, IL). Continuous variables are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. Analysis was performed using exact nonparametric tests, including (as appropriate for variable type) the Fisher exact test, the Wilcoxon rank sum test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Survival analysis (to the endpoint of ESRD) was performed using the Cox proportional hazard model (or Cox regression), with results reported as the hazard ratio or odds ratio and the 95% confidence interval (CI). For all tests, statistical significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Results

Clinical Features

The clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes of patients with MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN are summarized in Table 1. The cohort consisted of eight men and 6 women with a mean age of 58.7 yr (range 37 to 79 yr). Ten patients were white, three were black, and one was Hispanic. In 13 patients, MGN and NCGN were diagnosed simultaneously at the time of renal biopsy. In one patient (no. 14), biopsy-proven MGN preceded the development of RPGN on repeat biopsy 7 mo later. One patient (no. 7) had a 1-yr history of Wegener's granulomatosis of the respiratory tract before presentation with hematuria and proteinuria, raising the question of whether NCGN may have preceded the development of MGN; however, only one biopsy was performed.

Table 1.

Clinical data

| Characteristic | Patient

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Age (years) | 57 | 65 | 37 | 39 | 47 | 71 | 50 | 62 | 78 | 79 | 59 | 69 | 51 | 58 |

| Race | White | White | White | Black | White | White | Hispanic | Black | White | White | Black | White | White | White |

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Female | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Male | Male | Female |

| ANCA by IIF | P-ANCA | P-ANCA | P-ANCA | C-ANCA | P-ANCA | P-ANCA | C-ANCA | NA | C-ANCA | Atypical | C-ANCA | P-ANCA | P-ANCA | C-ANCA |

| ANCA specificity by ELISA | MPO | NA | MPO | PR3 | MPO | MPO | PR3 | PR3/MPO | NA | Neg | MPO | NA | NA | PR3 |

| Extrarenal manifestations of vasculitis | Hemoptysis | None | None | Panuveitis | None | None | Pulmonary nodules | None | None | None | None | Hemorrhagic duodenitis and GI bleeding | Sinusitis and epistaxis | Venulitis of liver |

| Urine protein (g/day) | 2 + on UA | 5.8 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 14 | 6.6 | 0.8 | 16 | Anuria | 3 + on UA | 3.5 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 5 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.5 | 3 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 1.4 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl): | 2.5 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 8.6 | 3 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 4 (on HD) | 8.9 | 6 | 5.4 | 8.7 | 3.1 |

| Treatment | IV CY/PRED then MMF | PRED/PO CY for 6 mo | M-PRED/PRED for 2.3 yrs/ IV CY for 6 mo | PRED/PO CY | PRED/IV CY for 2 mo | PRED/ PO CY for 1 yr | Azathioprine for 1 yr before Bx; PRED/PO CY for 1 yr | M-PRED then PRED/IV CY for 3 mo | PRED/IV CY for 2 mo | None | PRED/IV CY | M-PRED then PRED/PO CY/ PLX | NA | PRED/ IV then PO CY for 6 mo |

| Length of follow-up (months) | 38 | 101 | 28 | 66 | 2 | 46 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 0.25 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Follow-up creatinine | ESRD Died | 1.8 | 0.9 | 2.1 | ESRD Died | 2.8 | 0.8 | ESRD | 2.1 | Died | ESRD | 3.5 Died | ESRD Died | 0.8 |

| Follow-up proteinuria (g/day) | ESRD | Neg | 0.770 | 4.2 | ESRD | 0.817 | Neg | ESRD | 0.701 | ESRD | 1.1 | ESRD | 1.2 | |

ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; Bx, biopsy; CY, cyclophosphamide; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HD, hemodialysis; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPO, myeloperoxidase; M-PRED, methyl-prednisolone; neg, negative; NA, not available; PLX, plasmapheresis; PO, oral; PR3, proteinase 3; PRED, prednisone; UA, urinalysis.

ANCA testing was positive by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) and/or ELISA in all 14 patients. P-ANCA was detected by IIF in seven patients, four of whom were tested by ELISA and found to have MPO-ANCA. C-ANCA was positive in five patients, four of whom were tested by ELISA and found to have PR3-ANCA (three patients) or MPO-ANCA (one patient). Of the remaining two patients, one had both MPO- and PR3-ANCA and the other had an atypical ANCA. Six patients had extrarenal manifestations of vasculitis, including pulmonary nodules, pulmonary hemorrhage, sinusitis with epistaxis, panuveitis, hemorrhagic duodenitis with gastrointestinal bleeding, and hepatic venulitis.

None of the patients had a history of SLE or hepatitis B or C virus infection, and none were receiving a medication associated with drug-induced ANCA-associated NCGN or MGN (such as hydralazine, penicillamine, or propylthiouracil). Testing for antinuclear antibody (ANA), performed in 13 patients, was negative in 11 and weakly positive in two (nos. 2 and 5). Anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody was negative in all eight patients studied. Serum complement studies (C3 and C4) were performed in 13 patients, 11 of whom had normal levels, one had a depressed C3 (no. 5), and one had depressed C3 and C4 (no. 3). The two patients with hypocomplementemia had a negative anti-dsDNA antibody and no evidence of SLE, hepatitis, mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), or polymyositis. Anti-GBM antibody testing was negative in both patients who underwent testing (nos. 12 and 14). Past medical history included hypertension in six patients, polymyositis in two (nos. 2 and 8), prostate cancer in two (nos. 9 and 12), MCTD in one (no. 8), and gout in one (no. 5).

The majority of patients with ANCA-associated NCGN and MGN presented with RPGN and nephrotic range proteinuria (Table 1). At presentation, all of the patients had evidence of hematuria, and all but one had evidence of renal insufficiency, the single exception being patient 7, who had mild disease and had been treated with azathioprine for 1 yr before biopsy. The mean serum creatinine was 4.4 mg/dl (range 0.9 to 8.9). Proteinuria was documented in all 13 patients with available data. Among the 11 patients in whom a 24-h urine collection was available, the mean 24-h urine protein was 6.5 g/d (range 0.8 to 16 g), and nine had nephrotic range proteinuria with hypoalbuminemia, including five with edema, thus fulfilling criteria for full nephrotic syndrome. The remaining two patients had 2+ and 3+ protein on urinalysis. The mean serum albumin was 2.5 g/dl (range 1.4 to 3.5 g/dl). Peripheral edema was documented in six of the 14 patients.

Pathologic Features

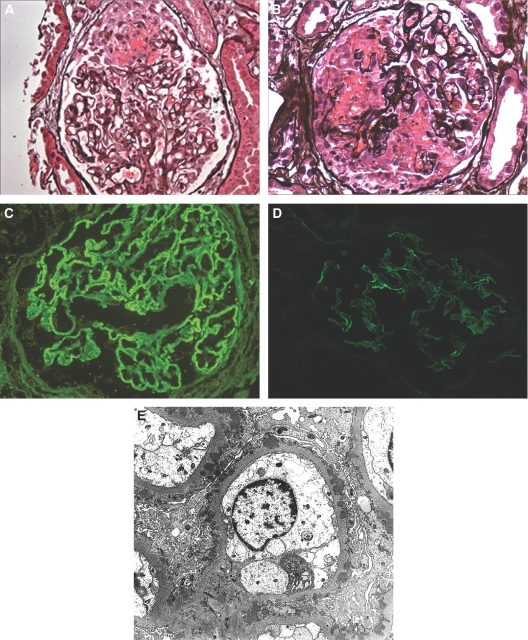

The renal biopsy findings are detailed in Table 2. Sampling for LM included a mean of 17.2 glomeruli (range 4 to 32 glomeruli), and a mean of 22.9% of glomeruli were globally sclerotic. All biopsies showed features of NCGN and MGN (Figure 1). Crescents were present in all patients (involving a mean of 32% of glomeruli), including cellular and fibrous crescents in three, exclusively cellular crescents in nine, and exclusively fibrous crescents in two. When present, cellular and fibrous crescents involved a mean of 27.1% and 23.5% of glomeruli, respectively (Figure 1, A and B). In all but one case, the crescents were accompanied by foci of fibrinoid necrosis with endocapillary and extracapillary fibrin, GBM rupture, and karyorrhexis (Figure 1, A and B). The necrotizing features involved a mean of 21% of glomeruli (range 5% to 50%). Although six cases exhibited mild mesangial hypercellularity, endocapillary proliferation was not seen in any case. Light microscopic findings of MGN, including GBM thickening and spike formation, were evident in eight cases. The degree of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis ranged from absent (two patients) to mild (affecting 1% to 25% of the cortex; five patients) to moderate (affecting 25 to 50% of the cortex; four patients) to severe (affecting > 50% of cortex; three patients). Interstitial inflammation was present in all biopsies, ranged from focal to diffuse, and was often accompanied by tubular degenerative changes. Arteriosclerosis and arteriolar hyalinosis were documented in 10 biopsies, and three had evidence of necrotizing vasculitis. In patient 14, the necrotizing vasculitis was accompanied by focal parenchymal infarction.

Table 2.

Renal biopsy findings

| Patient

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| Light microscopy | ||||||||||||||

| #gloms/#sclerotic gloms | 14/1 | 19/5 | 12/1 | 20/8 | 18/5 | 22/5 | 13/0 | 20/7 | 25/3 | 4/0 | 12/5 | 32/8 | 17/10 | 13/2 |

| % of gloms with crescents/necrosis | 29/38 | 5/0 | 16/33 | 15/5 | 83/6 | 59/5 | 15/15 | 30/15 | 33/33 | 50/50 | 41/17 | 19/19 | 24/12 | 23/31 |

| GBM spikes/vacuolization | No/no | Yes/yes | No/no | Yes/no | No/no | No/yes | Yes/no | Yes/no | No/no | No/no | Yes/yes | No/yes | No/no | Yes/yes |

| tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis | Mild | Moderate | Mild | Moderate | Moderate | Severe | None | Mild | Mild | Mild | Severe | Moderate | Severe | None |

| vascular disease | Moderate | Moderate (vasculitis) | None | Severe | mild | Moderate | Moderate | None | Moderate | Mild | Moderate | None (vasculitis) | None | Moderate (vasculitis) |

| Immunofluorescence | ||||||||||||||

| Positive immunoreactants and their intensities* | 2 + IgG, | 2 + IgG | 2 + IgG | 2 + IgG | 3 + IgG, | 2 + IgG | 1 + IgG | 2 + IgG | 1 + IgG | 3 + IgG | 2 + IgG | 1 + IgG | 2 + IgG | 2 + IgG |

| 1 + IgM | 2 + C3 | 1 + IgM | +/-C3 | 1 + IgM | 1 + IgA | 1 + IgA | +/-IgM | 1 + C3 | 1 + C3 | 1+κ | +/-C3 | 1 + C3 | 1 + C3 | |

| 1 + C3 | 2+κ | +/-IgA | 2+κ | 2 + C3 | 1 + C3 | 1 + C3 | 1 + C3 | +/-κ | 3+κ | 1+λ | 1+κ | +/-κ | 1+κ | |

| 1+κ | 2+λ | 2 + C3 | 2+λ | 2+κ | 1 + C1q | 1+κ | +/-C1q | +/-λ | 3+λ | +/-λ | +/-λ | 1+λ | ||

| 1+λ | 2+κ | 2+λ | 1+κ | 1+λ | 2+κ | |||||||||

| 2+λ | 1+λ | 1+λ | ||||||||||||

| Electron microscopy | Not performed | |||||||||||||

| % of capillary loops with subepithelial deposits | 60% | 90% | 80% | 100% | 90% | 20% | 15% | 40% | 15% | 20% | 90% | 30% | 100% | |

| Stage of MGN | I | II-III | I | II | I-II | III | II | I-II | I | I-II | I | I | II-III | |

| Mesangial deposits | Global | Rare | Segmental | None | None | None | Rare | Segmental | None | None | None | None | Segmental | |

| % Foot process effacement | 75% | 75% | 75% | 95% | 100% | 60% | 10% | 95% | 30% | 95% | 80% | 95% | 100% | |

GBM, glomerular basement membranes

Scale: trace (0.5%), 1-3+

Figure 1.

Renal biopsy findings in patients with membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated NCGN. (A) A glomerulus exhibits segmental fibrinoid necrosis, GBM rupture, and an early segmental cellular crescent. There is no evidence of glomerular basement membrane (GBM) spike formation in this patient with stage 1 MGN. (Jones methenamine silver). (B) Another glomerulus displays more extensive fibrinoid necrosis, multifocal GBM rupture, and a large cellular crescent. (Jones methenamine silver). (C) Immunofluorescence staining for IgG reveals granular global glomerular capillary wall positivity, typical of MGN. (D) Immunofluorescence staining for IgG reveals mild intensity, segmental capillary wall positivity in this patient with segmental MGN. (Magnification, ×400 in A-D). (E) Ultrastructural evaluation reveals global subepithelial electron dense deposits, the majority of which lie adjacent to GBM spikes. The findings appear most consistent with stage 2 MGN. (Magnification, ×4,000).

IF revealed granular, segmental to global glomerular capillary wall positivity in all patients for IgG (mean intensity [MI] 1.93+), kappa (MI 1.43+), and lambda (MI 1.34+) (Figure 1, C and D). Weaker staining for C3 (MI 1.15+), IgM (MI 0.87+) IgA (MI 0.83+), and C1q (MI 0.75) was detected in 13, 4, 3, and 2 patients, respectively. No patient showed IF findings that suggested a diagnosis of SLE, such as “full house” staining or “tissue ANA.” Staining for fibrinogen highlighted areas of glomerular fibrinoid necrosis. In two patients (nos. 8 and 13), there was focal, granular positivity for IgG in tubular basement membranes. No extraglomerular staining for IgG was seen in the remaining 12 cases.

EM was performed in 13 patients and showed features of MGN, including subepithelial electron dense deposits, often accompanied by GBM spikes and overlying neomembrane formation (Figure 1E). These deposits were segmental (involving 10% to 50% of glomerular capillary loops) in six patients and global (involving > 50%) in seven patients. The frequent occurrence of only segmental subepithelial deposits is different from cases of idiopathic MGN alone in which, in our experience, the deposits are usually global in distribution. The findings of MGN were classified as stage I in five patients, stage 1 to 2 in three patients, stage II in two patients, stage II-III in two patients, and stage III in one patient. Small, predominantly segmental mesangial deposits, which are often encountered in the setting of PNCGN, were seen in six patients, including one of the two patients with hypocomplementemia. Endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions were identified in two patients (nos. 3 and 8), both of whom had negative ANA and anti-dsDNA antibody. A single patient had focal extraglomerular deposits located in tubular basement membranes. The mean degree of foot process effacement was 78% (range, 10 to 100%).

Outcome

Clinical follow-up was available for all 14 patients. One patient (no. 10) refused hemodialysis or immunosuppressive therapy and died 1 wk postbiopsy. The mean duration of follow-up for the remaining 13 patients was 24.3 mo (median 8 mo; range 1 to 101 mo) (Table 1). Treatment data were available for 12 of the 13 patients, all of whom were treated with prednisone and CY (IV in six, oral in five, IV followed by oral in one). In addition, three patients also received pulse methyl-prednisolone, one received mycophenolate mofetil, and one was treated with plasmapheresis.

Despite aggressive therapy, five of the 13 patients progressed to ESRD. Three of the five patients who progressed to ESRD (nos. 1, 5, and 13) as well as a single additional patient (no. 12) died during the period of available follow-up. Among the remaining seven patients, treatment led to improvement in or stabilization of renal function in four and two patients, respectively. The single exception was patient 4, who had an increase in creatinine from 1.3 to 2.1 mg/dl over 66 mo, despite treatment with prednisone and oral CY. In all six patients with available data, treatment led to a significant decline in the degree of proteinuria. ANCA testing was repeated after treatment in seven patients, five of whom were seronegative.

On statistical analysis, the percentage of globally sclerotic glomeruli correlated with nonresponse (ESRD or worsening of serum creatinine with <50% reduction in proteinuria or remaining >2 g/d). By Cox regression analysis, the only significant risk factor for ESRD was serum creatinine at biopsy with a hazard or odds ratio of 1.11 (95% CI, 1.14 to 3.22, P = 0.015). The absence of a correlation between ESRD and the 24-h urine protein or percentage of glomeruli with crescents, open glomeruli (without necrosis or crescent formation), or any other pathologic parameter may have been due to the small sample size and type II error. Curve fitting estimation of 24-h urinary protein excretion as the dependent variable against the percentage of glomerular loops containing subepithelial deposits as the independent variable found no significant correlations, whether modeled as a linear, logarithmic, exponential, logistic, or power function. This lack of correlation may relate to the small sample size or the variable degree of concurrent ANCA glomerulonephritis, which also likely contributed to proteinuria.

Discussion

In the setting of membranous glomerulonephritis, fibrinoid necrosis and crescent formation are rarely encountered. When present, these changes suggest three diagnostic possibilities. First, a combination of crescentic and membranous glomerulonephritis is not uncommon in patients with SLE, corresponding to ISN/RPS lupus nephritis class III and V or IV and V. In the setting of lupus nephritis, the findings of membranous and crescentic changes are usually accompanied by endocapillary proliferation and subendothelial deposits. In the absence of evidence of SLE, findings of MGN with necrosis and crescent formation should raise the possibility of two potential superimposed disease processes, anti-GBM disease and ANCA-associated NCGN. Concurrent anti-GBM disease and MGN was first reported by Klassen et al. (12) in 1974, and since that time at least 20 cases have been described (13–15). In these cases, IF shows bilaminar staining of the GBM for IgG, with an inner layer of linear staining and an outer layer of granular positivity.

Coexistent MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN is a rare occurrence, with only 10 reported cases in the English literature in which clinical and pathologic findings are detailed (Table 3) (5–10). The 10 reported cases include seven men and three women with a mean age of 61 yr. In one patient, MGN preceded the development of ANCA-associated NCGN by 5 yr (7). In the remaining nine patients, MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN were diagnosed simultaneously in the same biopsy. Five patients had P-ANCA by IIF, three of whom were tested with ELISA and found to have MPO-ANCA. Three patients had C-ANCA by IIF. The remaining two patients were tested with ELISA only and were found to have MPO-ANCA. Evidence of systemic vasculitis was present in five of the 10 patients, including upper or lower respiratory tract involvement in three, skin involvement in two, and eye involvement in one (Table 3). Nine of the 10 patients were ANA negative, whereas a single patient had a weakly positive ANA (homogenous pattern) with negative anti-dsDNA antibody. All nine patients with available data had normal C3 and C4 complement levels. At presentation, nine of the 10 patients had renal insufficiency. Excluding the single patient who required HD, the mean serum creatinine was 3.7 mg/dl (median 1.7 mg/dl; range 1.1 to 13.8 mg/dl). All nine patients with urine output had proteinuria, including four with full nephrotic syndrome. Hematuria was documented in all but one patient, who was oliguric. Renal biopsy established the diagnoses of MGN and NCGN and revealed a mean percentage of glomeruli with crescents of 37% (range 11 to 73%).

Table 3.

Clinicopathologic findings in previously reported cases of MGN with ANCA-associated NCGN

| Author (ref) | Age/sex | ANCA by IIF | ANCA specificity by ELISA | Extrarenal features of vasculitis | ANA | Creatinine (mg/dl) | 24-h urine protein (g) | Albumin (g/dl) | Hematuria | % of glomeruli with crescents | MGN stage | Treatment | Length of follow-up | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaber (5) | 64/M | C-ANCA | NA | Recurrent sinusitis Otitis media Pulmonary capillaritis | Neg | 3.4 | 1.6 | NP | Yes | 11% | II-III | PRED/CY | 22 months | Resolution of pulmonary lesions, Normalization of s. Cr, Diminution of proteinuria |

| Taniguchi (6) | 68/F | NA | MPO | None | Neg | 1.45 | 1.26 | 3.2 | Yes | 55% | II | PRED | 3 months | Normalization of s. Cr |

| Kanahara (7) | 47/F | P-ANCA | MPO | Pulmonary hemorrhage | Neg | 1.1 | 5.7 | 2.9 | Yes | NP | III-IV | M-PRED then PRED/CY | 6 months | Diminution of proteinuria, Disappearance of crescents (on repeat Bx) |

| Dwyer (8) | 67/M | P-ANCA | MPO | None | Neg | HD | 7.16 | 2.7 | Yes | NP | II-III | PRED/ azathioprine | NP | ESRD |

| Dwyer (8) | 69/M | P-ANCA | MPO | Iritis | Pos | 1.47 | 0.56 | 2.6 | Yes | 23% | I | PRED/CY | NP | Normalization of s. Cr |

| Tse (9) | 30/M | C-ANCA | NA | Cutaneous vasculitis | Neg | 1.4 | 1.5 | 3.5 | Yes | 50%(1 of 2 glomeruli) | II | PRED/CY | 10 yr | Stable renal function |

| Tse (9) | 64/M | P-ANCA | NA | None | Neg | 5.8 | 10 | 3 | Yes | 23% | II | None | 2 yr | ESRD 3 months post-Bx |

| Tse (9) | 65/M | P-ANCA | NA | None | Neg | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.3 | Yes | 28% | I | PRED/CY | 5 yr | Partial recovery (s. Cr 1.5 mg/dl) |

| Tse (9) | 70/M | C-ANCA | NA | Nasal obstruction Rash | Neg | 13.8 | Oliguric | 3.9 | No | 73% | II | PRED/CY/ HD/PLX | 5 yr | Partial recovery (s. Cr 2.2 mg/dl) |

| Suwabe (10) | 68/F | NA | MPO | None | Neg | 3 | 7 | 2.5 | Yes | 31% | I-II | PRED/CY | 10 months | Partial recovery |

| (s. Cr 1.8 mg/dl, 24-h urine protein 0.5 g) |

MGN, membranous glomerulonephritis; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; NCGN, necrotizing and crescentic glomerulonephritis; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; ANA, antinuclear antibody; Bx, biopsy; CY, cyclophosphamide; HD, hemodialysis; MPO, myeloperoxidase; M-PRED, pulse methyleprednisolone; NA, not available; NP, not provided; s. Cr, serum creatinine; PLX, plasmapheresis; PRED, prednisone; UA, urinalysis

Among the 10 reported cases of MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN, induction therapy consisted of prednisone and CY in seven patients, prednisone and azathioprine in one patient, and prednisone alone in one patient (Table 3). One patient also received plasmapheresis. A single patient with diabetes mellitus and severe chronic damage on biopsy did not receive immunosuppression (9). After a mean follow-up of 38 mo (range 3 mo to 10 yr), four patients had apparent complete renal recovery (normalization of serum creatinine in two, normalization of serum creatinine with resolution of proteinuria in one, and resolution of proteinuria with disappearance of crescents in one), three had partial recovery with a decline in serum creatinine, one (who had normal creatinine at presentation) had stable renal function, and two progressed to ESRD. Of note, Table 3 does not include three examples of MGN with ANCA-associated NCGN that have been attributed to treatment with penicillamine or propylthiouracil (16,17).

There are also rare reports of concomitant MGN and crescentic glomerulonephritis in which there is no evidence of anti-GBM disease, ANCA seropositivity, or SLE (9,18), and we have seen a number of similar cases. In these cases, crescent formation may represent an unusual morphologic expression of MGN.

Our study details the clinical features, pathologic findings, and outcomes in 14 additional patients with MGN concurrent with ANCA-associated NCGN. It provides the largest reported experience with the co-existence of these two distinct disease processes. The mean age of patients at diagnosis in this study was 58.7 yr, which is higher than that reported in large series for patients with MGN alone (19) and lower than that for those with ANCA-associated NCGN alone (20). Similar to the other cases reported in the literature, in the vast majority of our patients MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN were diagnosed simultaneously at presentation. This is different from the situation of concurrent MGN and anti-GBM disease, in which MGN preceded the development of anti-GBM nephritis in close to 50% of reported cases (13,15). By definition, none of the patients in our study had SLE. Two patients had polymyositis, including one who also carried a diagnosis of MCTD. In these two patients, who showed mesangial hypercellularity and mesangial deposits, MGN was possibly secondary to polymyositis and/or MCTD (21). Two additional patients had a history of prostate carcinoma, which is rarely associated with MGN (22,23). The remaining 10 patients had no underlying condition known to be associated with MGN. The clinical presentation of patients with MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN in our cohort is relatively similar to ANCA-associated NCGN alone except for the presence of heavier proteinuria. The mean 24-h urine protein for our patients was 6.5 g, compared with 1.7 to 2.5 g in patients with ANCA disease alone (4). In the majority (77%) of cases, the membranous alterations were stage 1 or 2 and in 42% of cases were segmental, suggesting that MGN was detected in its early stages. The patients’ outcome in our cohort appears to be worse than that of other patients with MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN reported in the literature (Table 3) and that of patients with ANCA-associated NCGN alone (24,25), with 50% reaching endpoints of death or ESRD, despite similar treatments. In our cohort, ESRD correlated with a higher serum creatinine at biopsy. There was no correlation between ESRD and the percentage of glomeruli with cellular crescents or necrosis, or the percentage of open glomeruli, features known to influence outcome in pure ANCA-associated NCGN. This is likely due to the small sample size.

Our data suggest that the co-existence of MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN is rare and is likely to be coincidental. During the period from January 2000 to February 2008, the Renal Pathology Laboratory at Columbia University processed 13,022 native kidney biopsies, including 1149 cases of MGN from non-SLE patients (8.8%) and 444 cases of ANCA-associated NCGN (3.4%). On the basis of these numbers, 39 biopsies with MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN would have been predicted to occur by chance, whereas only 14 cases were actually found. Given these numbers, as well as the fact that the pathogenesis of MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN are distinct and both conditions were diagnosed simultaneously in the majority of cases, we believe that MGN with ANCA-associated NCGN represents a chance occurrence of two unrelated disease processes.

ANCA-associated NCGN has been frequently reported to occur superimposed on other glomerular disease processes, including IgA nephropathy (26), acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis (27), lupus nephritis (11), and even diabetic glomerulosclerosis (28). Recent data suggest that glomerular injury may be potentiated by synergetic effects of ANCAs and immune complex deposits. Haas and Eustace examined 126 cases of ANCA-associated PNCGN by IF and EM and found glomerular immune complex deposits, mostly confined to the mesangium, in 54% of cases (29). When present, the subepithelial and intramembranous deposits were typically few in number, although two biopsies contained numerous subepithelial deposits and likely represented ANCA-associated NCGN with MGN. Interestingly, in this study the presence of immune deposits by EM was associated with heavier proteinuria and a higher percentage of glomeruli with crescents (29). Similarly, another study compared 37 cases of ANCA-associated NCGN without deposits to eight cases with deposits by IF and found a positive correlation between the presence of deposits and the degree of proteinuria (30). On the basis of these studies and the poor outcomes in our cohort, patients with MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN are likely to have heavier proteinuria and a worse prognosis than patients with ANCA-associated NCGN alone. Of note, the presence of immune deposits has also been shown to augment glomerular injury induced by ANCA in mice (31,32).

In summary, we report the largest clinical experience to date with MGN and ANCA-associated NCGN. This dual glomerulopathy likely represents the coincidental occurrence of two separate disease processes. From the perspective of ANCA-associated NCGN, the finding of coincidental MGN appears to be associated with a greater degree of proteinuria and to have a negative impact on the already poor prognosis of this condition. Conversely, the finding of glomerular fibrinoid necrosis or crescent formation in the setting of MGN should lead to prompt testing for ANCA. The diagnosis of MGN with ANCA-associated NCGN should be considered in patients who present with RPGN and nephrotic syndrome.

Disclosures

None.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Korbet SM, Genchi RM, Borok RZ, Schwartz MM: The racial prevalence of glomerular lesions in nephrotic adults. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 647–651, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogan SL, Muller KE, Jennette JC, Falk RJ: A review of therapeutic studies of idiopathic membranous glomerulopathy. Am J Kidney Dis 25: 862–887, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamesh L, Harper L, Savage CO: ANCA-positive vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1953–1960, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M, Yu F, Zhang Y, Zhao MH: Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated vasculitis in older patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 87: 203–209, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaber LW, Wall BM, Cooke CR: Coexistence of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated glomerulonephritis and membranous glomerulopathy. Am J Clin Pathol 99: 211–215, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taniguchi Y, Yorioka N, Kumagai J, Ito T, Yamakido M, Taguchi T: Myeloperoxidase antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis and membranous glomerulonephropathy. Clin Nephrol 52: 253–255, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanahara K, Yorioka N, Nakamura C, Kyuden Y, Ogata S, Taguchi T, Yamakido M: Myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated glomerulonephritis with membranous nephropathy in remission. Intern Med 36: 841–846, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dwyer KM, Agar JW, Hill PA, Murphy BF: Membranous nephropathy and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated glomerulonephritis: A report of 2 cases. Clin Nephrol 56: 394–397, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tse WY, Howie AJ, Adu D, Savage CO, Richards NT, Wheeler DC, Michael J: Association of vasculitic glomerulonephritis with membranous nephropathy: A report of 10 cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 1017–1027, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suwabe T, Ubara Y, Tagami T, Sawa N, Hoshino J, Katori H, Takemoto F, Hara S, Aita K, Hara S, Takaichi K: Membranous glomerulopathy induced by myeloperoxidaseanti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-related crescentic glomerulonephritis. Intern Med 44: 853–858, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nasr SH, D'Agati VD, Park HR, Sterman PL, Goyzueta JD, Dressler RM, Hazlett SM, Pursell RN, Caputo C, Markowitz GS: Necrotizing and crescentic lupus nephritis with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody seropositivity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 682–690, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klassen J, Elwood C, Grossberg AL, Milgrom F, Montes M, Sepulveda M, Andres GA: Evolution of membranous nephropathy into anti-glomerular-basement-membrane glomerulonephritis. N Engl J Med 13; 290: 1340–1344, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasr SH, Ilamathi ME, Markowitz GS, D'Agati VD: A dual pattern of immunofluorescence positivity. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 19–26, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Troxell ML, Saxena AB, Kambham N: Concurrent anti-glomerular basement membrane disease and membranous glomerulonephritis: A case report and literature review. Clin Nephrol 66: 120–127, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nayak SG, Satish R: Crescentic transformation in primary membranous glomerulopathy: association with anti-GBM antibody. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 18: 599–602, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathieson PW, Peat DS, Short A, Watts RA: Coexistent membranous nephropathy and ANCA-positive crescentic glomerulonephritis in association with penicillamine. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11: 863–866, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu F, Chen M, Gao Y, Wang SX, Zou WZ, Zhao MH, Wang HY: Clinical and pathological features of renal involvement in propylthiouracil-associated ANCA-positive vasculitis. Am J Kidney Dis 49(5): 607–614, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arrizabalaga P, Sans Boix A, Torras Rabassa A, Darnell Tey A, Revert Torrellas L: Monoclonal antibody analysis of crescentic membranous glomerulonephropathy. Am J Nephrol; 18: 77–782, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cattran DC, Pei Y, Greenwood CM, Ponticelli C, Passerini P, Honkanen E: Validation of a predictive model of idiopathic membranous nephropathy: Its clinical and research implications. Kidney Int 51: 901–907, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Agati VD, Jennette JC, Silva FG. Atlas of nontumor pathology: non-neoplastic kidney diseases. Washington, DC, American Registry of Pathology-Armed Forced Institute of Pathology, 2005

- 21.Takizawa Y, Kanda H, Sato K, Kawahata K, Yamaguchi A, Uozaki H, Shimizu J, Tsuji S, Misaki Y, Yamamoto K: Polymyositis associated with focal mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with depositions of immune complexes. Clin Rheumatol 26: 792–796, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefaucheur C, Stengel B, Nochy D, Martel P, Hill GS, Jacquot C, Rossert J, GN-PROGRESS Study Group: Membranous nephropathy and cancer: Epidemiologic evidence and determinants of high-risk cancer association. Kidney Int 70: 1510–1517, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuura H, Sakurai M, Arima K: Nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy associated with metastatic prostate cancer: Rapid remission after initial endocrine therapy. Nephron 84: 75–78, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Booth AD, Almond MK, Burns A, Ellis P, Gaskin G, Neild GH, Plaisance M, Pusey CD, Jayne DR, Pan-Thames Renal Research Group: Outcome of ANCA-associated renal vasculitis: a 5-year Retrospective study. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 776–784, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogan SL, Nachman PH, Wilkman AS, Jennette JC, Falk RJ: Prognostic markers in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated microscopic polyangiitis and glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 23–32, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haas M, Jafri J, Bartosh SM, Karp SL, Adler SG, Meehan SM: ANCA-associated crescentic glomerulonephritis with mesangial IgA deposits. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 709–718, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas M: Incidental healed postinfectious glomerulonephritis: A study of 1012 renal biopsy specimens examined by electron microscopy. Hum Pathol 34: 3–10, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nasr SH, D'Agati VD, Said SM, Stokes MB, Appel GB, Valeri AM, Markowitz GS. Pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis superimposed on diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol May 28, 2008. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Haas M, Eustace JA: Immune complex deposits in ANCA-associated crescentic glomerulonephritis: A study of 126 cases. Kidney Int 65: 2145–2152, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neumann I, Regele H, Kain R, Birck R, Meisl FT: Glomerular immune deposits are associated with increased proteinuria in patients with ANCA-associated crescentic nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 524–531, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jennette JC, Xiao H, Falk RJ: Pathogenesis of vascular inflammation by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1235–1242, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao H, Heeringa P, Hu P, Liu Z, Zhao M, Aratani Y, Maeda N, Falk RJ, Jennette JC: Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies specific for myeloperoxidase cause glomerulonephritis and vasculitis in mice. J Clin Invest 110: 955–963, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]