Abstract

A 25-year-old man presents to the emergency department with a toothache. During the evaluation, the physician determines that the patient has been taking large doses of over-the-counter acetaminophen along with an acetaminophen–hydrocodone product for the past 5 days. His daily dose of acetaminophen has been 12 g per day (maximum recommended dose, 4 g per day). He has no other medical problems and typically consumes two beers a day. The patient has no symptoms beyond his toothache, is not icteric, and has no hepatomegaly or right-upper-quadrant tenderness. His serum acetaminophen concentration 8 hours after the most recent dose is undetectable. His serum alanine aminotransferase concentration is 75 IU per liter, his serum bilirubin concentration is 1.2 mg per deciliter (20.5 μmol per liter), and his international normalized ratio (INR) is 1.1. The emergency department physician contacts the regional poison-control center, which recommends treatment with acetylcysteine.

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM

Acetaminophen (known as paracetamol outside the United States) is a commonly used analgesic and antipyretic agent, and its use is one of the most common causes of poisoning worldwide.1 According to poison centers in the United States, acetaminophen poisoning was responsible for more than 70,000 visits to health care facilities and approximately 300 deaths in 2005.2 Acetaminophen poisoning can be due to ingestion of a single overdose (usually as an attempt at self-harm) or ingestion of excessive repeated doses or too-frequent doses, with therapeutic intent. Repeated supratherapeutic ingestion is increasingly recognized as a significant clinical problem.3,4

Regardless of whether it occurs as a result of a single overdose or after repeated supratherapeutic ingestion, the progression of acetaminophen poisoning can be categorized into four stages: preclinical toxic effects (a normal serum alanine aminotransferase concentration), hepatic injury (an elevated alanine aminotransferase concentration), hepatic failure (hepatic injury with hepatic encephalopathy5), and recovery. This categorization is useful because each stage has a different prognosis and is managed differently. Transient liver injury may develop in patients who are treated during the preclinical stage, but they recover fully.3,6 Patients who are not treated until hepatic injury has developed have a variable prognosis,3,4 and patients who present with hepatic failure have a mortality rate of 20 to 40%.4,7

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND EFFECT OF THER APY

When taken in therapeutic doses, acetaminophen is safe. Studies in animals have shown that most of a single dose (>90%) is metabolized by glucuronidation or sulfation to nontoxic metabolites8 (Fig. 1A). Approximately 5% of a therapeutic dose is metabolized by cytochrome P450 2E1 to the electrophile N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI).8 NAPQI is extremely toxic to the liver, possibly as a result of covalent binding to proteins and nucleic acids.9 However, NAPQI is rapidly detoxified by interaction with glutathione to form cysteine and mercapturic acid conjugates.10 As long as sufficient glutathione is present, the liver is protected from injury. Overdoses of acetaminophen (either a single large ingestion or repeated supra-therapeutic ingestion) can deplete hepatic glutathione stores and allow liver injury to occur.11

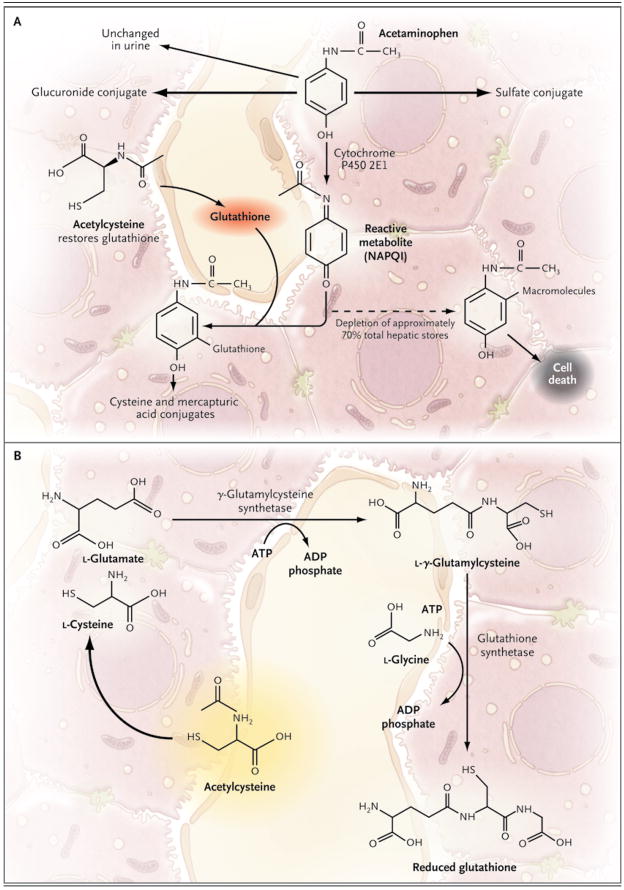

Figure 1. The Metabolism of Acetaminophen and the Synthesis of Glutathione.

The primary pathways for acetaminophen metabolism (Panel A) are glucuronidation and sulfation to nontoxic metabolites. Approximately 5% of a therapeutic dose is metabolized by cytochrome P450 2E1 to the electrophile N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). NAPQI is extremely toxic to the liver. Ordinarily, NAPQI is rapidly detoxified by interaction with glutathione to form cysteine and mercapturic acid conjugates. If glutathione is depleted, NAPQI interacts with various macromolecules, leading to hepatocyte injury and death. Glutathione is synthesized from the amino acids cysteine, glutamate, and glycine by means of the pathway shown in Panel B. Glutamate and glycine are present in abundance in hepatocytes; the availability of cysteine is the rate-limiting factor in glutathione synthesis. However, cysteine itself is not well absorbed after oral administration. Acetylcysteine, in contrast, is readily absorbed and rapidly enters cells, where it is hydrolyzed to cysteine, thus providing the limiting substrate for glutathione synthesis.

Acetylcysteine (also known as N-acetylcysteine) prevents hepatic injury primarily by restoring hepatic glutathione (Fig. 1B).10 In addition, in patients with acetaminophen-induced liver failure, acetylcysteine improves hemodynamics and oxygen use,12 increases clearance of indocyanine green (a measure of hepatic clearance),13 and decreases cerebral edema.14 The exact mechanism of these effects is not clear, but it may involve scavenging of free radicals or changes in hepatic blood flow.12,15

CLINICAL EVIDENCE

In the late 1960s, clinicians recognized that acute acetaminophen overdose caused a dose-related liver injury and that without treatment many patients die.16 Studies in animals described the metabolism of acetaminophen to NAPQI and showed that as long as hepatic glutathione was present, toxic effects could be prevented.10,17 Soon there were reports that methionine18 and cysteamine19 (two medications known to restore hepatic glutathione) could prevent acetaminophen-induced hepatic injury. Use of these agents resulted in dramatic increases in survival, but the side effects (flushing, vomiting, and “misery”18) associated with these therapies led researchers to seek alternative treatments.

Acetylcysteine was first suggested as an anti-dote for acetaminophen toxicity in 1974.20 Subsequently, several case series described good outcomes for patients with acetaminophen overdose who were treated on the basis of the presence of a toxic blood concentration with either intravenous21,22 or oral6,23–25 acetylcysteine. The largest of these was a study involving 2540 patients and oral acetylcysteine.6 The study showed that aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase concentrations rose to above 1000 IU per liter in 6.1% of patients who were treated within 10 hours after ingestion and in 26.4% of those treated between 10 and 24 hours after ingestion. This was a marked improvement as compared with the findings in historical controls, and this and similar studies led to the widespread acceptance of acetylcysteine for the prevention of hepatic injury due to acetaminophen overdose.

Two small studies have evaluated the efficacy of acetylcysteine in patients in whom acetaminophen-induced hepatic failure had already developed; both used the intravenous agent. In a retrospective study involving 98 patients, treatment with acetylcysteine was associated with a 21% reduction in mortality, as compared with standard therapy.26 This was followed by a randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving 50 patients that showed a 28% reduction in mortality.14

Larger trials, or trials in other clinical settings, have not been performed. For example, there are no systematic studies evaluating the usefulness of acetylcysteine for patients who have hepatic injury but not hepatic failure. Nonetheless, the efficacy and apparent safety of this agent, as demonstrated in the two small studies,14,26 have led to widespread use of acetylcysteine therapy in almost all cases of acetaminophen-induced liver injury. A 2006 Cochrane review of the available data concluded that acetylcysteine “should be given to patients with overdose” but acknowledged that the quality of the evidence is limited.27

CLINICAL USE

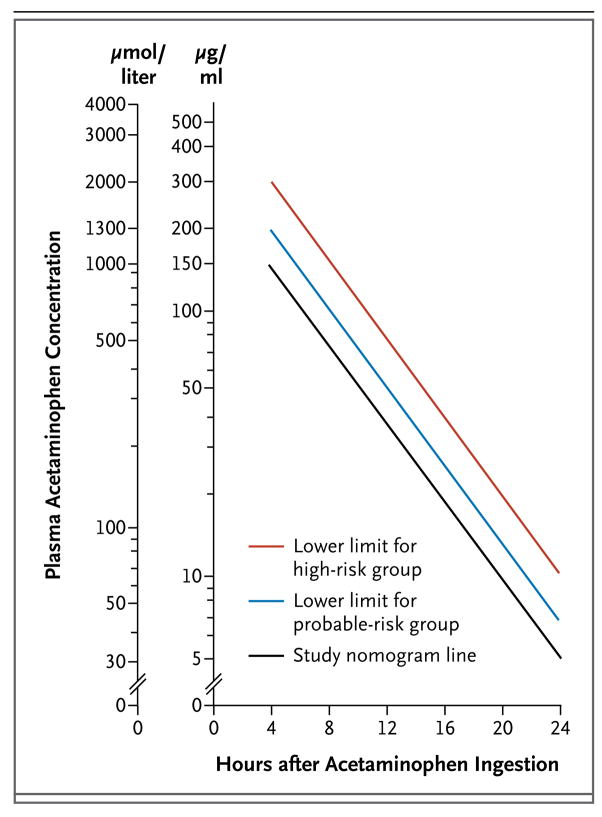

The first studies of acetylcysteine therapy involved patients who presented to a health care facility within 24 hours after a single acute ingestion of acetaminophen and had a plasma concentration above the “study line” (also known as the “possible toxicity” line) on the Rumack–Matthew nomogram (Fig. 2).6,22,23,28 Patients who have a timed serum acetaminophen concentration (i.e., as measured between 4 hours and 24 hours after ingestion) that falls above the study line on this nomogram are considered to be at risk for toxic effects, even if no clinical or laboratory evidence of hepatic injury is present. Most poison centers in the United States would recommend treatment for such patients. Several centers in the United States and in many other countries recommend treatment only for patients who have a serum concentration that falls above the “probable toxicity” line, which starts at 200 μg per milliliter 4 hours after ingestion.

Figure 2. The Rumack–Matthew Nomogram.

The Rumack–Matthew nomogram, first published in 1975, was developed to estimate the likelihood of hepatic injury due to acetaminophen toxicity for patients with a single ingestion at a known time. To use the nomogram, the patient’s plasma acetaminophen concentration and the time interval since ingestion are plotted. If the resulting point is above and to the right of the sloping line, hepatic injury is likely to result and the use of acetylcysteine is indicated. If the point is below and to the left of the line, hepatic injury is unlikely. Patients with repeated supratherapeutic ingestion, or with an unknown time of ingestion, cannot be evaluated with the use of the Rumack–Matthew nomogram.

Patients for whom the time of ingestion is unknown cannot be risk-stratified with the use of the Rumack–Matthew nomogram. For example, a “therapeutic” serum concentration of 20 μg per milliliter would fall above the threshold for treatment if the ingestion occurred more than 16 hours before the concentration was measured. In such cases, I believe that it is prudent to administer acetylcysteine to any patient who may have taken an overdose and who has a measurable acetaminophen concentration until risk stratification can be performed (i.e., until the time of ingestion is determined), until the patient meets the criteria for stopping, or until the course is completed. This approach, however, is not standard practice for all poison-control centers.

Similarly, patients with a history of repeated supratherapeutic ingestion cannot be risk-stratified with the Rumack–Matthew nomogram. My colleagues and I at the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center recommend treating such patients with acetylcysteine if they have a supra-therapeutic serum acetaminophen concentration (>20 μg per milliliter), even if their alanine aminotransferase concentration is normal. We also recommend treatment for any patient with an elevated alanine aminotransferase concentration and a history of ingesting more than 4 g of acetaminophen per day. Such approaches are not standard in all centers. In addition, on the basis of data from two small clinical studies, acetylcysteine is generally recommended in patients with established hepatic failure.11,14

The choice of oral or intravenous administration depends on the clinical scenario; to my knowledge, no clinical trials comparing the two routes in adults have been performed. Oral administration is convenient for patients with pre-clinical toxic effects or hepatic injury, but in many patients, vomiting or altered mental status may preclude oral therapy. Patients who are treated for hepatic failure should receive intravenous therapy.

The optimal route of administration for pregnant patients has been debated.29 In pregnancy, high hepatic extraction of the oral dose may mean that very low concentrations of acetylcysteine are available to the fetus. Nevertheless, there is experience with the use of oral acetylcysteine after maternal acetaminophen overdose.30 Furthermore, acetylcysteine concentrations in the fetus are similar to maternal systemic concentrations during oral treatment, suggesting that the fetus will have therapeutic levels.31 There are no compelling clinical or pharmacokinetic data to suggest that intravenous administration is better than oral administration for pregnant patients. Acetylcysteine is in Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy category B (meaning that there are no data from adequate and well-controlled studies of safety in this population, but studies in animals have not suggested any effect on the fetus).

According to current FDA-approved protocols for the treatment of acute acetaminophen ingestion, oral acetylcysteine is given as a loading dose of 140 mg per kilogram of body weight, with maintenance doses of 70 mg per kilogram that are repeated every 4 hours for a total of 17 doses.6 The intravenous loading dose is 150 mg per kilogram over a period of 15 to 60 minutes, followed by an infusion of 12.5 mg per kilogram per hour over a 4-hour period, and finally an infusion of 6.25 mg per kilogram per hour over a 16-hour period.21 The dose does not require adjustment for renal or hepatic impairment or for dialysis.

Although these standard protocols are based on a prespecified duration of therapy, many toxicologists believe that the defined oral course (72 hours) is often too long and that the defined intravenous course (20 hours) may be too short for patients in whom hepatic injury develops or for those who have ingested massive amounts of acetaminophen. Therefore, our poison center recommends that practitioners base the treatment course on clinical end points. Many toxicologists would recommend repeating the measurements of alanine aminotransferase and acetaminophen concentrations as the patient approaches the end of the 16-hour infusion period and continuing treatment if the alanine aminotransferase concentration is elevated or if the acetaminophen concentration is measurable. Rechecking the alanine aminotransferase and serum acetaminophen concentrations is particularly important if the patient presents more than 8 hours after ingestion, has an elevated alanine aminotransferase concentration at the time treatment is started, or has a very high acetaminophen concentration (>300 μg per milliliter).

In general, patients are hospitalized in an acute care facility for acetylcysteine therapy. However, outpatient therapy may be considered for patients with a confirmed accidental, repeated supratherapeutic ingestion, a supratherapeutic serum acetaminophen concentration (I use a threshold of <70 μg per milliliter), and no more than low-grade elevation of the alanine aminotransferase concentration (<3 times the upper limit of the reference range for the laboratory). If the patient has no adverse effects associated with the oral loading dose, he or she can be discharged with three maintenance doses to be taken every 4 hours. The patient should be reevaluated 12 hours after the loading dose, and treatment can be discontinued if the patient meets the criteria for stopping therapy (i.e., the alanine aminotransferase concentration is decreasing, and the serum acetaminophen concentration is undetectable). Patients may be treated with oral acetylcysteine on a psychiatric (i.e., nonmedical) ward if they meet criteria for outpatient treatment and can be given their maintenance doses every 4 hours. Patients treated with oral acetylcysteine should be monitored for vomiting, and the dose should be repeated if the patient vomits within 60 minutes after any dose.6

Patients receiving intravenous acetylcysteine for liver failure should be hospitalized in a critical care unit. Monitoring should include frequent blood-pressure measurements, measurement of oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, and close nursing observation for hypoglycemia and signs of infection. Liver and renal function should also be monitored, but there is little use in obtaining blood samples for testing more often than every 12 hours. Treatment is continued until the hepatic encephalopathy resolves and the alanine aminotransferase and creatinine concentrations and INR have substantially improved or until the patient receives a liver transplant.

Oral acetylcysteine is inexpensive; a full 18-dose course will cost the pharmacy less than $50 (in 2005 U.S. dollars).32 However, this does not include the nursing required to ensure administration or the costs of the antiemetic agents that are often required. Intravenous acetylcysteine is also relatively inexpensive (approximately $470 for a full course32), but there are additional costs for preparation of the medications and intravenous administration.

ADVERSE EFFECTS

Acetylcysteine has an unpleasant smell and taste, and vomiting is common with oral administration. However, in a large study at a poison center, only 5% of patients ultimately required intravenous therapy because they could not tolerate the oral agent.33 In adults, even very high doses of oral acetylcysteine are not associated with severe toxic effects.34

The most commonly reported adverse effects of intravenous acetylcysteine are anaphylactoid reactions, including rash, pruritus, angioedema, bronchospasm, tachycardia, and hypotension. Kerr et al. reported that approximately 15% of patients who were treated with intravenous acetylcysteine had an anaphylactoid reaction within 2 hours after the initial infusion and that increasing the infusion time from 15 to 60 minutes did not alter the rate of adverse events.35 Other common adverse effects included vomiting and flushing. However, administration of the drug was discontinued in only 2% of patients because of an adverse reaction. Retrospective studies identified adverse effects in approximately 5% of cases.33,36

Recommendations for the treatment of adverse effects during acetylcysteine therapy have been proposed.37 According to these recommendations, no treatment is necessary for flushing alone. Patients with urticaria should be treated with diphenhydramine. Those with angioedema, hypotension, or respiratory symptoms (e.g., bronchospasm) should be treated with diphenhydramine, corticosteroids, and bronchodilators for bronchospasm. The acetylcysteine infusion should be stopped, but it can be restarted at a slower rate 1 hour after the administration of diphenhydramine if symptoms do not recur.37 Alternatively, patients with severe symptoms who do not have liver failure can be treated with oral acetylcysteine.

The most severe adverse effects occur with erroneous dosing of intravenous acetylcysteine in children. These effects include cerebral edema38,39 and hyponatremia (due to administration in 5% dextrose).40 There are rare reports of deaths due to anaphylactoid reactions.41,42

AREAS OF UNCERTAINT Y

The initial studies of intravenous administration of acetylcysteine demonstrated the efficacy of a 20-hour regimen, whereas studies of oral administration evaluated a 72-hour regimen. This discrepancy has led to the question, “How long is long enough?” Several reports have described truncation of oral acetylcysteine therapy in some patients. One study reported good outcomes among patients who were treated with a 20-hour course that was started within 8 hours after ingestion of acetaminophen.43 In three other studies (two retrospective and one prospective), patients were treated until the acetaminophen concentration was undetectable and the serum alanine aminotransferase activity was normal. In these studies, most patients received at least 20 hours of therapy.44–46 These studies suggest that patients who receive early treatment may be candidates for a shorter course of therapy; however, the most appropriate duration of therapy is not clear.

The clinical studies of acetylcysteine therapy have evaluated either treatment of preclinical toxic effects (based on the Rumack–Matthew nomogram) or therapy in patients with established hepatic failure. As a result, explicit data for the earlier stage of hepatic injury without hepatic failure are not available. We believe that patients who present with hepatic injury and detectable acetaminophen concentrations should be treated at least until the acetaminophen has been eliminated. The role of treatment is less clear for patients who have no measurable acetaminophen concentration but have hepatic injury without hepatic failure. Our poison center recommends treatment based on the evidence that acetylcysteine is effective early, for the prevention of hepatic injury, as well as late, for treatment of hepatic failure. Therefore, it seems logical that patients with a presentation between these two extremes would also benefit.

GUIDELINES

There are several guidelines describing the use of acetylcysteine for acute acetaminophen poisoning. The United Kingdom National Health Service guideline recommends treating patients who have acute acetaminophen overdose and a serum acetaminophen concentration above the probable-toxicity line (the line that begins at 200 μg per milliliter at 4 hours after ingestion) and high-risk (alcoholic or malnourished) patients who have a serum concentration above a high-risk line that begins at 100 μg per milliliter at 4 hours.47 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends acetylcysteine therapy for acetaminophen poisoning, but it does not suggest indications or support any treatment protocol.48 The American College of Emergency Physicians recommends acetylcysteine therapy for any patient with acute acetaminophen ingestion and a timed serum concentration above the line that begins at 150 μg per milliliter at 4 hours, as well as for any patient with liver injury or liver failure.49

RECOMMENDATIONS

Although in many cases acute acetaminophen poisoning is a straightforward problem, the vignette illustrates a common situation for which there are no clear answers. Published protocols have focused on patients with acetaminophen poisoning who present with a toxic acetaminophen concentration and without liver injury. These patients will do well as long as they receive timely acetylcysteine therapy. Patients who present with liver failure have a less favorable prognosis, but it is clear that acetylcysteine treatment improves their chance of surviving. The best treatment for the patient who cannot be risk-stratified with the use of the Rumack–Matthew nomogram, or who has hepatic injury without hepatic failure, is less well defined.

On the basis of the established benefit of acetylcysteine therapy in other specific settings, I favor treatment of the patient described in the vignette. I would choose oral therapy and administer the loading dose of 140 mg per kilogram in the emergency department. Since the patient does not appear to have intended to harm himself and is clinically well, I would discharge him from the emergency department with additional doses of 70 mg per kilogram to be taken every 4 hours. I would recommend that he be seen in the outpatient clinic 12 hours after discharge in order to obtain a repeat measurement of alanine aminotransferase activity; if it is clearly decreasing, his therapy can be terminated before he completes a course of 17 doses.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Heard reports receiving grant support from McNeil Consumer Products, Cumberland Pharmaceuticals, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (training grant DA020573). No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

I thank the Medical Toxicology Fellows of the Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center and Dr. Richard Dart for their thoughtful review and suggestions.

Footnotes

This Journal feature begins with a case vignette that includes a therapeutic recommendation. A discussion of the clinical problem and the mechanism of benefit of this form of therapy follows. Major clinical studies, the clinical use of this therapy, and potential adverse effects are reviewed. Relevant formal guidelines, if they exist, are presented. The article ends with the author’s clinical recommendations.

References

- 1.Gunnell D, Murray V, Hawton K. Use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) for suicide and nonfatal poisoning: worldwide patterns of use and misuse. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000;30:313–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai MW, Klein-Schwartz W, Rodgers GC, et al. 2005 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ national poisoning and exposure database. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006;44:803–932. doi: 10.1080/15563650600907165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daly FF, O’Malley GF, Heard K, Bogdan GM, Dart RC. Prospective evaluation of repeated supratherapeutic acetaminophen (paracetamol) ingestion. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:393–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiødt FV, Rochling FA, Casey DL, Lee WM. Acetaminophen toxicity in an urban county hospital. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1112–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710163371602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trey C, Davidson CS. The management of fulminant hepatic failure. In: Popper H, Schaffner F, editors. Progress in liver disease. Vol. 3. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1970. pp. 282–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smilkstein MJ, Knapp GL, Kulig KW, Rumack BH. Efficacy of oral N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen overdose: analysis of the national multicenter study (1976 to 1985) N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1557–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812153192401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makin AJ, Wendon J, Williams R. A 7-year experience of severe acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity (1987–1993) Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1907–16. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90758-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jollow DJ, Thorgeirsson SS, Potter WZ, Hashimoto M, Mitchell JR. Acet-aminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. VI. Metabolic disposition of toxic and non-toxic doses of acetaminophen. Pharmacology. 1974;12:251–71. doi: 10.1159/000136547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR, Potter WZ, Davis DC, Gillette JR, Brodie BB. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. II. Role of covalent binding in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973;187:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell JR, Jollow DJ, Potter WZ, Gillette JR, Brodie BB. Acetaminophen- induced hepatic necrosis. IV. Protective role of glutathione. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973;187:211–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potter WZ, Thorgeirsson SS, Jollow DJ, Mitchell JR. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. V. Correlation of hepatic necrosis, covalent binding and glutathione depletion in hamsters. Pharmacology. 1974;12:129–43. doi: 10.1159/000136531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison PM, Wendon JA, Gimson AES, Alexander GJM, Williams R. Improvement by acetylcysteine of hemodynamics and oxygen transport in fulminant hepatic failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1852–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106273242604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devlin J, Ellis AE, McPeake J, Heaton N, Wendon JA, Williams R. N-acetyl-cysteine improves indocyanine green extraction and oxygen transport during hepatic dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:236–42. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199702000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keays R, Harrison PM, Wendon JA, et al. Intravenous acetylcysteine in paracetamol induced fulminant hepatic failure: a prospective controlled trial. BMJ. 1991;303:1026–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6809.1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones AL. Mechanism of action and value of N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of early and late acetaminophen poisoning: a critical review. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36:277–85. doi: 10.3109/15563659809028022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson DG, Eastham WN. Acute liver necrosis following overdose of paracetamol. Br Med J. 1966;2:497–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5512.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell JR, Jollow DJ, Potter WZ, Davis DC, Gillette JR, Brodie BB. Acetaminophen-induced hepatic necrosis. I. Role of drug metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1973;187:185–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prescott LF, Sutherland GR, Park J, Smith IJ, Proudfoot AT. Cysteamine, methionine, and penicillamine in the treatment of paracetamol poisoning. Lancet. 1976;2:109–13. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)92842-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prescott LF, Newton RW, Swainson CP, Wright N, Forrest AR, Matthew H. Successful treatment of severe paracetamol overdosage with cysteamine. Lancet. 1974;1:588–92. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prescott LF, Matthew H. Cysteamine for paracetamol overdosage. Lancet. 1974;1:998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prescott LF, Park J, Ballantyne A, Adriaenssens P, Proudfoot AT. Treatment of paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning with N-acetylcysteine. Lancet. 1977;2:432–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prescott LF, Illingworth RN, Critchley JA, Stewart MJ, Adam RD, Proudfoot AT. Intravenous N-acetylcystine: the treatment of choice for paracetamol poisoning. BMJ. 1979;2:1097–100. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6198.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rumack BH, Peterson RC, Koch GG, Amara IA. Acetaminophen overdose: 662 cases with evaluation of oral acetylcysteine treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:380–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.141.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rumack BH. Acetaminophen overdose in young children: treatment and effects of alcohol and other additional ingestants in 417 cases. Am J Dis Child. 1984;138:428–33. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1984.02140430006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rumack BH, Peterson RG. Acetaminophen overdose: incidence, diagnosis, and management in 416 patients. Pediatrics. 1978;62:898–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison PM, Keays R, Bray GP, Alexander GJ, Williams R. Improved outcome of paracetamol-induced fulminant hepatic failure by late administration of acetylcysteine. Lancet. 1990;335:1572–3. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91388-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brok J, Buckley N, Gluud C. Interventions for paracetamol (acetaminophen) overdose. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD003328. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003328.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smilkstein MJ, Bronstein AC, Linden C, Augenstein WL, Kulig KW, Rumack BH. Acetaminophen overdose: a 48-hour intravenous N-acetylcysteine treatment protocol. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:1058–63. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81352-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bizovi KE, Smilkstein MJ. Acetaminophen. In: Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS, editors. Goldfrank’s toxicologic emergencies. 7. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2002. pp. 480–501. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riggs BS, Bronstein AC, Kulig K, Archer PG, Rumack BH. Acute acetaminophen overdose during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:247–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horowitz RS, Dart RC, Jarvie DR, Bearer CF, Gupta U. Placental transfer of N-acetylcysteine following human maternal acetaminophen toxicity. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35:447–51. doi: 10.3109/15563659709001226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Acetylcysteine (Acetadote) for acetaminophen overdosage. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2005;47:70–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yip L, Dart RC, Hurlbut KM. Intravenous administration of oral N-acetylcysteine. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:40–3. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199801000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller LF, Rumack BH. Clinical safety of high oral doses of acetylcysteine. Semin Oncol. 1983;10(Suppl 1):76–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerr F, Dawson A, Whyte IM, et al. The Australasian Clinical Toxicology Investigators Collaboration randomized trial of different loading infusion rates of N-acetylcysteine. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:402–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kao LW, Kirk MA, Furbee RB, Mehta NH, Skinner JR, Brizendine EJ. What is the rate of adverse events after oral N-acetylcysteine administered by the intravenous route to patients with suspected acetaminophen poisoning? Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:741–50. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(03)00508-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey B, McGuigan MA. Management of anaphylactoid reactions to intravenous N-acetylcysteine. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:710–5. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70229-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailey B, Blais R, Letarte A. Status epilepticus after a massive intravenous N-acetylcysteine overdose leading to intracranial hypertension and death. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hershkovitz E, Shorer Z, Levitas A, Tal A. Status epilepticus following intravenous N-acetylcysteine therapy. Isr J Med Sci. 1996;32:1102–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sung L, Simons JA, Dayneka NL. Dilution of intravenous N-acetylcysteine as a cause of hyponatremia. Pediatrics. 1997;100:389–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Appelboam AV, Dargan PI, Knighton J. Fatal anaphylactoid reaction to N-acetylcysteine: caution in patients with asthma. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:594–5. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.6.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynard K, Riley A, Walker BE. Respiratory arrest after N-acetylcysteine for paracetamol overdose. Lancet. 1992;340:675. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92211-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yip L, Dart RC. A 20-hour treatment for acute acetaminophen overdose. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2471–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200306123482422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Betten DP, Cantrell FL, Thomas SC, Williams SR, Clark RF. A prospective evaluation of shortened course oral N-acetylcysteine for the treatment of acute acetaminophen poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:272–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woo OF, Mueller PD, Olson KR, Anderson IB, Kim SY. Shorter duration of oral N-acetylcysteine therapy for acute acetaminophen overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:363–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsai CL, Chang WT, Weng TI, Fang CC, Walson PD. A patient-tailored N-acetylcysteine protocol for acute acetaminophen intoxication. Clin Ther. 2005;27:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Management of acute paracetamol poisoning: guidelines agreed by the UK National Poisons Information Service 1998 (supplied to accident and emergency centres in the United Kingdom by the Paracetamol Information Centre in collaboration with the British Association for Accident and Emergency Medicine). London: National Poisons Information Service, 1998.

- 48.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Acetaminophen toxicity in children. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1020–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolf SJ, Heard K, Sloan EP, Jagoda AS. Clinical policy: critical issues in the management of patients presenting to the emergency department with acetaminophen overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:292–313. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]