Gallstone ileus is an uncommon cause of small-bowel obstruction, accounting for about 1%–4% of cases.1,2 Although the most common location for intestinal obstruction by a biliary calculus is the terminal ileum, obstruction infrequently occurs more proximally. In rare cases, gallstones migrate into the duodenum through a cholecystoduodenal fistula and become impacted, producing gastric outlet obstruction. This syndrome was originally described in 1896 by Bouveret.3 Our report describes 2 cases of Bouveret syndrome, their surgical management and clinical outcomes.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

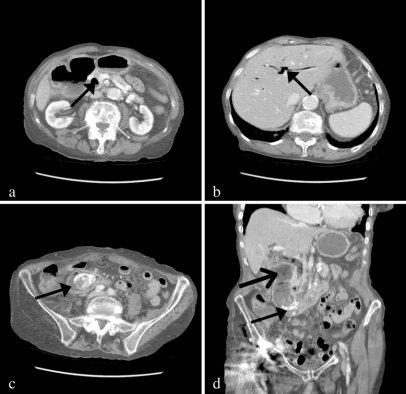

An 84-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with bilious vomiting, obstipation and epigastric pain. Her medical history included bouts of biliary colic. Physical examination revealed a frail woman with a distended abdomen and epigastric tenderness. A small calculus was palpable on digital rectal examination. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed a large fistulous tract extending from the gallbladder to the duodenal bulb, as well as a large calculus obstructing the second part of the duodenum. There was also evidence of pneumobilia with significant dilatation of the biliary tree (Fig. 1). Initial management consisted resuscitation with intravenous fluids and nasogastric decompression. The patient subsequently underwent exploratory laparotomy. A gallstone was easily palpable in the duodenum. We kocherized the duodenum before performing a duodenotomy through which we extracted a massive calculus. We did not perform a cholecystectomy or repair the cholecystoduodenal fistula. On examination of the stomach, duodenum, jejunum and ileum, we found no other stones. The patient experienced postoperative cardiac complications that were effectively stabilized in the short-term, but she went into cardiac arrest on postoperative day 7 and died.

Fig. 1. Cross-sectional images show (a) a fistula extending from the gallbladder wall to the bulb of the duodenum (arrow), (b) intrahepatic pneumobilia (arrow) and (c) a large calculus obstructing the second part of the duodenum (arrow). (d) Coronal reconstruction demonstrates a large obstructing calculus in the second part of the duodenum (thin arrow) along with a prominent cholecystoduodenal fistula (thick arrow).

Case 2

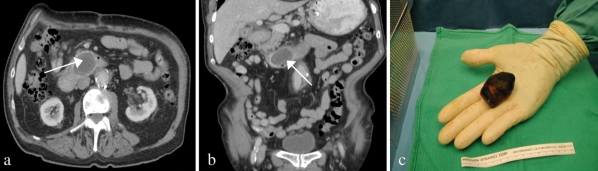

A 71-year-old man presented with a 1-week history of persistent abdominal pain associated with nausea, vomiting and obstipation. His medical history included recent acute cholecystitis, which was managed conservatively with antibiotics. His surgical history was significant for an abdominal aortic aneurysm repair 5 months before presentation. Physical examination revealed a fit patient. The abdomen was not distended but was tender in the epigastrium. Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a large gallstone impacted in the third part of the duodenum with associated pneumobilia and a large cholecystoduodenal fistula (Fig. 2). Initially, the patient received intravenous fluids and had nasogastric decompression. A laparoscopic approach to remove the obstructing gallstone was considered but not pursued because of the prior abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. We therefore performed a midline laparotomy. Through a transverse duodenotomy we extracted a 6-cm calculus from the third part of the duodenum. We then easily removed 3 smaller calculi from the gallbladder through the fistula. We did not perform a cholecystectomy or repair the cholecystoduodenal fistula. On transfer to the postanesthetic care unit, the patient was in stable condition. He was discharged on postoperative day 10.

Fig. 2. Cross-sectional image (a) and coronal reconstruction (b) demonstrate a large calculus impacted in the third part of the duodenum (arrows). (c) Intraoperative photograph shows a 6-cm gallstone, which was extracted from the second part of the duodenum.

DISCUSSION

Bouveret syndrome is a rare complication of cholelithiasis in which calculi become impacted in the duodenum, resulting in gastric outlet obstruction. Management of this condition aims to remove the obstructing gallstone. Owing to the chronic inflammatory changes, it is difficult to address gallbladder inflammation and fistula repair during the initial procedure. This notion is supported by studies showing that cholecystectomy and surgical management of the fistula carry a higher mortality and complication rate than when the gallbladder and fistula are left in situ.2 Therefore, acute treatment is often aimed at simply alleviating the obstruction. Since the cholecystoenteric fistula is usually large, recurrent complications are rare.4 A second surgery to take down the fistula and remove the gallbladder is therefore unnecessary. To remove the obstructing calculus, endoscopic,1 laparoscopic5 and open surgical approaches have been attempted.1 Although endoscopic extraction is less invasive, it often fails when the obstructing calculus is very large.1 Furthermore, fragmentation of calculi for extraction with endoscopic graspers can result in their passage to and possible obstruction of distal small bowel.1 Since gallstones that get obstructed in the duodenum tend to be quite large (> 2.5 cm), a surgical approach is the optimal treatment. The procedure of choice, as reported here, is to extract the stone, intact, through a duodenotomy and to examine the remaining bowel to identify other calculi that may cause recurrent obstruction.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. P. Colquhoun Division of General Surgery University Hospital 339 Windermere Rd., PO Box 5339 London ON N6A 5A5 fax 519 663-3906 patrick.colquhoun@lhsc.on.ca

References

- 1.Ariche A, Czeiger D, Gortzak Y, et al. Gastric outlet obstruction by gallstone: Bouveret syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol 2000;35:781-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg 1994;60:441-6. [PubMed]

- 3.Bouveret L. Stenose du pylore adhérent à la vesicule. Rev Med (Paris) 1896;16:1-16.

- 4.Naranjo A. Cholecystectomy and fistula closure versus enterolithotomy alone in gallstone ileus. Br J Surg 1997;84:634-7. [PubMed]

- 5.Malvaux P, Degolla R, De Saint-Hubert M, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of a gastric outlet obstruction caused by a gallstone (Bouveret's syndrome). Surg Endosc 2002;16:1108-9. [DOI] [PubMed]