Abstract

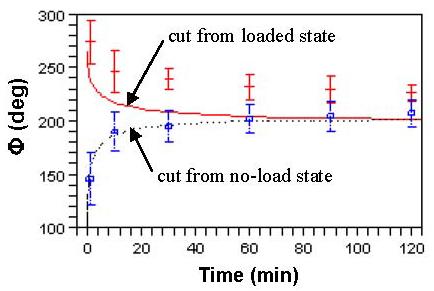

An artery ring springs open into a sector after a radial cut. The opening angle characterizes the residual strain in the unloaded state, which is fundamental to understanding stress and strain in the vessel wall. A recent study revealed that the opening angle decreases with time if the artery is cut from the loaded state, while it increases if the cut is made from the no-load state due to viscoelasticity. In both cases, the opening angle approaches the same value in 3 hours. This implies that the characteristic relaxation time is about 10,000 sec. Here, the creep function of a generalized Maxwell model (a spring in series with six Voigt bodies) is used to predict the temporal change of opening angle in multiple time scales. It is demonstrated that the theoretical model captures the salient features of the experimental results. The proposed creep function may be extended to study the viscoelastic response of blood vessels under various loading conditions.

Keywords: relaxation, creep, viscoelastic, blood vessel

1 Introduction

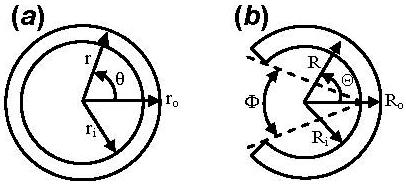

The residual strain in an unloaded artery (Fig. 1(a)) can be released by making a radial cut. The zero-stress state is then revealed as an open sector (Fig. 1(b)). The angle subtended by two radii connecting the midpoint of the inner wall to its tips is typically defined as the opening angle and has been used to characterize the residual strain.

Fig. 1.

An artery at the (a) no-load and (b) zero-stress state. ri and ro, Ri and Ro, are the inner and outer radii in the (r, θ, z) and (R, Θ, Z) coordinate systems, respectively, and Φ denotes the opening angle.

The residual strain plays an important role in homogenizing the transmural wall stress [1-4] and has been well studied [4-6]. Rehal et al. [6] pointed out that measured opening angle can be affected by arterial viscoelasticity. They found that the opening angle (30 min after cut) decreases significantly as duration of the no-load state increases. Interestingly, Rehal et al. [6] showed that artery opening angle decreases with time if the ring is cut from the loaded state, while it increases if the cut is made from the no-load state. In both cases, the opening angle asymptotically reaches the same value within 3 hours.

Rehal et al. [6] revealed an important feature of the arterial viscoelasticity; i.e., it takes up to 10,000 seconds to cover the creep process. As a first approximation, they adopted the Kelvin (standard linear solid) model to fit their data. However, creep mainly occurs within one decade of time and the rate-insensitive hysteresis behavior of living soft tissues cannot be considered in a Kelvin model [3]. In this regard, continuous spectrum functions and generalized Maxwell models that cover multiple time scales should be utilized to predict viscoelastic behavior of biomaterials [3, 7-9].

In this study, we adopt a generalized Maxwell model to predict the creep of porcine coronary arteries over several decades of time (0.1-5,000 sec). It will be shown that the temporal evolution of opening angle can be predicted well with the linear viscoelastic model.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Experimental Data

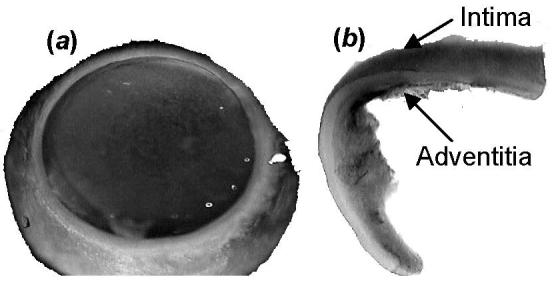

The dimensions of artery rings were measured at room temperature following the procedure described in Rehal et al. [6]. Basically, the heart was excised and placed in a cold saline bath immediately after the pig was sacrificed. The left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery was cannulated and perfused at physiological pressure of 100 mmHg with the catalyzed silicone elastomer. After the elastomer hardened, the LAD was cut transversely into rings (length of ∼1 mm) and placed in a Ca2+-free Krebs solution aerated with 95% O2-5% CO2 [6], maintaining the elastomer in the lumen. The ring was photographed in the loaded state as shown in Fig. 2(a).

Fig. 2.

Photographs of a porcine coronary artery at the (a) loaded state with hardened elastomer in the lumen and (b) zero-stress state where opening angle is larger than 180°.

For one pair of rings, one ring was cut from loaded state and the open sector was photographed immediately (about 1 min) and followed for 2 hours. The second ring was cut after the elastomer was removed for 30 min. Photographs of the open sector were taken at the same time points. A typical open sector is shown in Fig. 2(b). A total of 6 pairs of rings were examined.

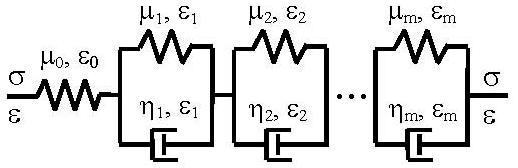

2.2 Creep Recovery

We consider a generalized Maxwell body where a spring with elastic modulus μ0 is connected serially with m Voigt elements (springs in parallel with dashpots, Fig. 3). In the i-th Voigt body, the spring has an elastic modulus μi and the dashpot has a viscous coefficient ηi (i = 1, …, m). Under a constant stress load σ0, the creep function J(t) is the responsive strain ε(t) divided by σ0 [3, 10]:

| (1) |

where t denotes time.

Fig. 3.

A generalized Maxwell viscoelastic model (a linear spring in serial with m Voigt elements).

To reduce model parameters, we assume τi = ηi/μi = ρi−1τ (where i−1 indicates a power) and μi = μ0/[β(1+β)i−1] which imply that the characteristic frequencies form a geometric series and the elastic moduli of each Voigt element are interrelated, see Zhang et al. [21] for rationalization. As a result, the reduced creep function can be obtained as:

| (2) |

where τ is a characteristic relaxation time, ρ characterizes the gap between successive relaxation times, β = μ0/μ1, and J(∞) = (1+β)m/μ0.

For a ring cut from loaded state, the strain decreases first elastically as a step, followed by a creep process. The creep recovery can be described by the superposition principal [10]. Suppose the loaded artery was under a stress σ0 in the circumferential direction and the viscous stress has been fully relaxed (Fig. 2(a)), the corresponding strain is (Eqs. (1) and (2)):

| (3) |

Starting from t = 0, the ring is cut open and a stress −σ0 induces a new strain (using Eqs. (1) and (2)) given by:

| (4) |

The total strain recovery εr(t) after the radial cut (stress is completely released) is:

| (5) |

Note that for m = 1, the model in Fig. 3 is mathematically equivalent to a spring in parallel with a Maxwell body [3, 11]. Therefore, the Kelvin model considered by Rehal et al. [6] is a special case of the generalized Maxwell model in Eq. (5).

For a ring cut from no-load state, the analysis assumes the following three steps: 1) the loaded artery is fully relaxed (stress is σ0 at t = 0−); 2) no-load state is obtained after elastomer removal (stress is σ1 from t = 0+ to t = t1 = 1800 sec); 3) the ring is cut open at t = t1 and all stress is released. It is noted that the second step is an approximation (i.e., not strictly under constant stress).

According to the superposition principal [10], the strain recovery in the artery after the radial cut can be written as:

| (6) |

where εn(t) → 0 when t → ∞ (fully recovered zero-stress state). The substitution of Eqs. (2)-(5) into Eq. (6) results in

| (7) |

where ε1 = σ1J(∞) is the residual strain due to residual stress σ1.

We will show that the strain recovery history can be used to predict the temporal evolution of opening angle observed in experiments.

2.3 Artery Opening Angle

The artery is assumed to be incompressible. The loaded state is a tube with a circular cross section (Fig. 1(a)). The circumferential stretch ratio at the inner surface is:

| (8) |

and at the outer surface is:

| (9) |

where ri and ro are inner and outer radii at loaded state, Ci and Co are inner and outer circumferences at fully relaxed zero-stress state, respectively.

In the generalized Maxwell model, linear stress-strain relation is expected. However, arteries are known to exhibit nonlinear constitutive behavior [3]. Recently, Zhang and Kassab [12] proposed to absorb the material nonlinearity with a new strain measure in the two-dimensional case. The same idea was then extended to the three-dimensional Hooke's law [13] where the logarithmic-exponential (log-exp) strain was defined as (no shear deformation):

| (10) |

where λi are stretch ratios, n is a constant that characterizes the material nonlinearity, and J1 is the first invariant of the right Cauchy-Green deformation tensor:

| (11) |

The second Piola-Kirchhoff stress and the log-exp strain in the circumferential direction can be written as [13]:

| (12) |

where c's are elastic moduli with respect to the log-exp strains.

As an estimate, we assume Dzz ≈ 0 (λz ≈ 1). This implies that the artery was axially relaxed. In such a case, Drr = −Dθθ (λr = 1/λθ) according to Eq. (10). The circumferential strain becomes

| (13) |

It is noted that Eq. (12) can naturally reduce to a one-dimensional linear model (Sθθ ∝ ε). Other models using Green strain measure (e.g., Fung model) can be used approximately since the strain is small (thus stress-strain relation can be linearized) during the creep process.

The open sector is characterized by an opening angle Φ (Fig. 1(b)). Considering the volumetric incompressibility condition λθλzλr = 1, the cross-sectional wall area A0 can be calculated by [1, 14]:

| (14) |

where Li and Lo are inner and outer circumferences of the sector (not fully relaxed). Equation (14) yields the opening angle expressed by

| (15) |

For given A0, Li and Lo, Φ can be computed from Eq. (15). It was found that the change of these measures is negligible 2 hours after the radial cut. Thereafter, the artery is assumed to be fully relaxed; i.e., Li = Ci, Lo = Co, and Φ = Φ0 at t = 7,200 sec. The stretch ratio of the open sector λθ(t) = L(t)/C is equal to the circumference at a given time over that at the fully relaxed state, which differs from that at the loaded state (Eqs. (8) and (9)). The strain is computed with Eq. (13).

3 Results

Table 1 shows the dimensions of six pairs of rings measured in experiments (L1-L6 were cut from loaded state, N1-N6 were cut from no-load state). The biological variability is reflected by the standard deviations (SD).

Table 1.

Measured dimensions of porcine left anterior descending artery rings. L and N refer to the loaded and no-load states. ri and ro denote inner and outer radii at loaded state. Ci/Co, and Φ0 are inner/outer circumferences, and opening angle at fully relaxed zero-stress state.

| Ring # | ri (mm) | ro (mm) | Ci (mm) | Co (mm) | Φ0 (deg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 1.58 | 1.74 | 6.46 | 6.30 | 215.7 |

| L2 | 1.58 | 1.73 | 6.28 | 6.16 | 223.3 |

| L3 | 1.36 | 1.48 | 5.35 | 5.20 | 229.2 |

| L4 | 1.29 | 1.41 | 5.41 | 5.14 | 236.1 |

| L5 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 4.67 | 4.49 | 232.7 |

| L6 | 1.01 | 1.10 | 4.24 | 4.12 | 220.9 |

| N1 | 1.56 | 1.72 | 6.55 | 6.50 | 194.1 |

| N2 | 1.55 | 1.70 | 6.03 | 6.05 | 212.3 |

| N3 | 1.37 | 1.51 | 5.50 | 5.29 | 227.2 |

| N4 | 1.28 | 1.41 | 5.25 | 5.21 | 201.7 |

| N5 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 4.27 | 4.23 | 194.0 |

| N6 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 3.83 | 3.79 | 213.7 |

| mean | 1.31 | 1.44 | 5.32 | 5.21 | 216.7 |

| SD | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 14.3 |

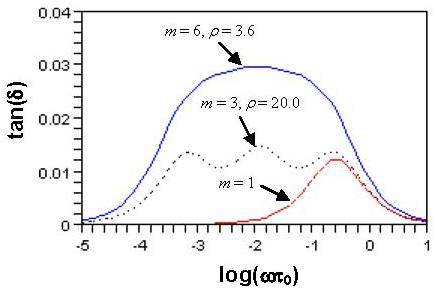

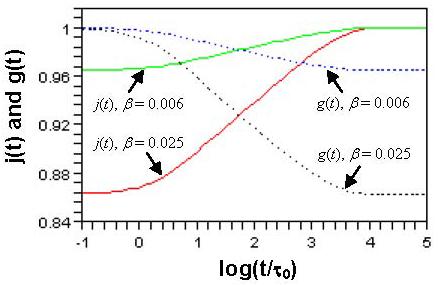

To determine how many Voigt elements are needed to cover the creep time scale, consider the internal friction tan(δ); i.e., the mechanical loss defined as tangent of the lag phase angle δ between the responsive strain and the applied oscillatory stress with angular frequency ω [10]. Figure 4 shows that for m = 1 the model covers mainly one decade of time, but for m = 3 (ρ = 20.0) and m = 6 (ρ = 3.6) it covers almost four decades of time (−4 < log(ωτ0) < 0, τ0 = 1.0 sec is a normalization factor). Here, we choose m = 6 (ρ = 3.6, τ = 4.0 sec) to obtain a smooth tan(δ) curve, as shown by the solid line in Fig. 4. The creep functions for β = 0.025 and β = 0.006 are shown in Fig. 5. The above choice (see Figs. 4 and 5) is consistent with the results that creep or relaxation of blood vessels is significant in the range of 0.1 sec < t < 5,000 sec [3, 6, 8, 15-19].

Fig. 4.

The plots of tan(δ) versus log(ωτ0) of the generalized Maxwell model for τ = 4.0 sec and β = 0.025. Note that τ0 = 1.0 sec has been used to nondimensionalize the abscissa.

Fig. 5.

Reduced creep function j(t) and reduced relaxation function g(t) for m = 6, ρ = 3.6, τ = 4.0 sec.

To use the log-exp strain, we consider a typical nonlinearity parameter n = 1.45 for porcine LAD artery [20]. Under the loaded state, the strain ε0 in Eqs. (3) and (5) is evaluated at r = ri and r = ro by Eqs. (8), (9) and (13) using the mean values in Table 1. The results are εa = 1.43 (inner surface) and εb = 3.87 (outer surface). The mid-wall stretch ratio is λa = 2π(ri+ro)/(Ci+Co) = 1.64. Since the average strain (across wall thickness) at the no-load state is zero (i.e., λθ = 1), we estimate the residual strain ε1 by scaling the strain difference from the loaded state back to the no-load state: εc ≈ (εa−εb)/(2λa) = −0.74 at the inner surface and εd ≈ (εb−εa)/(2λa) = 0.74 at the outer surface (assuming a linear transmural distribution).

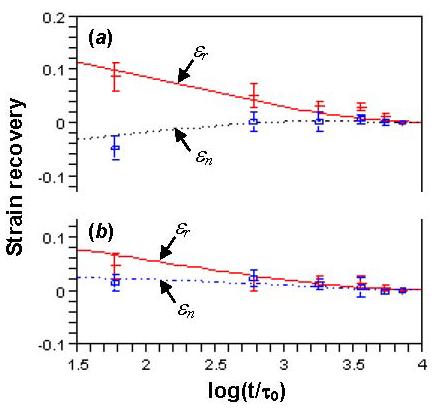

The values of ε0 = εa in Eq. (5) and ε1 = εc in Eq. (7) are considered first. Figure 6(a) shows the strain recovery at the inner surface for six pairs of artery rings cut from loaded state and no-load state (time starts immediately after the cut, data are shown as mean±SD). It is seen that strain is small (large elastic strain has been released instantly). The strains of rings cut from loaded state decrease, while the strains of rings cut from no-load state increase with time. They tend to zero after 120 min (log(t/τ0) = 3.86). Figure 6(b) shows the strain evolution at the outer surface (withε0 = εb and ε1 = εd in Eqs. (5) and (7)). It reveals that strains decrease when rings are cut from loaded state, but they almost do not change when the cut is from no-load state. It was found that β = 0.025 and β = 0.006 are good predictors of the strain evolutions at the inner and outer surfaces, respectively, as shown in Fig. 6. The different choices of β for inner and outer surfaces imply that we treat the arterial wall as a heterogeneous material.

Fig. 6.

The strain recovery after the radial cut at the (a) inner surface with β = 0.025 and (b) outer surface with β = 0.006. εr (Eq. (5)) and εn (Eq. (7)) are theoretical predictions with m = 6, ρ = 3.6, τ = 4.0 sec.

Using the theoretical strains εr and εn in Fig. 6, we computed λθ(t) according to Eq. (13). Then Li and Lo were obtained by L(t) = Cλθ(t). The Φ(t) was calculated by Eq. (15) (A0 = 0.78 mm2 is the average result derived from Eq. (14) with λz = 1, ri ≈ 1.31, ro ≈ 1.44, Li ≈ 5.32, Lo ≈ 5.21 in unit of mm, and Φ ≈ 216.7°, see Table 1) and compared with experimental measurements in Fig. 7. The model captures the trend of Φ(t), but predicts smaller values. The possible reasons are discussed below.

Fig. 7.

Temporal evolution of opening angles measured in experiments and predicted by the model.

4 Discussion

For a linear viscoelastic model, the relaxation and creep functions are related by a convolution [3, 10]. This relation can be used to obtain reduced relaxation function g(t) from j(t), or vice versa. The g(t) derived from the convolution (using Laplace transform [10]) has been shown in Fig. 5 with j(t). It can be numerically proved that the relaxation times in g(t) also form a geometric series, with the same ρ characterizing the gap between successive frequencies. The use of j(t) or g(t) to fit experimental result depends on how the data are obtained (creep or relaxation test). It is noted that the parameters μ0, τ, m, ρ, and β in this study should be interpreted similarly as those in Zhang et al. [21], where a generalized Maxwell model was proposed for relaxation function instead of creep function.

The arterial wall is known to be heterogeneous and may be treated mechanically as a two-layer composite made of intima-media and adventitia [3, 8, 22, 23]. The intima is mainly a single layer of endothelial cells and its mechanical property is usually ignored. The media contains smooth muscle cells, elastin and collagen fibrils. The adventitia largely consists of collagen fibers, ground substance, fibroblasts and fibrocytes. Taking into account the arterial wall structure, the finding that viscosity is larger at the inner surface (β = 0.025) than the outer surface (β = 0.006) as shown in Fig. 6 is consistent with the fact that viscous behavior is due to the presence of smooth muscle cells [24]. It should be noted that this approach does not adopt an explicit two-layer model and the heterogeneity of the vessel wall is considered only by fitting the viscoelastic model to strains at inner and outer surfaces separately.

We made several assumptions that warrant discussion. First, the geometry of the artery ring was assumed to be ideal as shown in Fig. 1, but the actual shape can be quite different; e.g., Fig. 2. Second, the open sector after one radial cut was taken to be zero-stress state as a first order approximation. Third, the strain and creep process in the axial direction were neglected. Fourth, the effect of smooth muscle tone, which may considerably change the viscoelasticity at physiological conditions, was not considered. Fifth, the fitting of the viscoelastic model was done in the range of small strains and thus needs to be validated under physiological state. In addition, some parameters were arbitrarily chosen (e.g., τ and β were adjusted manually until theoretical results closely match experimental data, see Fig. 6). A rigorous least square method is desirable for better representation. These factors may be responsible for the smaller predicted opening angle (Fig. 7). On the other hand, considering the scatter of biological data, the modeling correctly captures the trend that the opening angle of porcine coronary arteries increases or decreases with time when the ring is cut from the loaded or no-load states.

Although the Maxwell viscoelastic model is well known, this is the first time the number of parameters is reduced by considering the relations τi = ηi/μi = ρi−1τ and μi = μ0/[β(1+β)i−1] in conjunction with the creep experimental data of a porcine coronary artery. Thus, the essence of experiments on temporal change of opening angle [6, 25, 26] can be explained by the viscoelastic model. This is an assessment of the model's utility to capture the salient features of arterial viscoelasticity.

It is important to obtain reliable material properties considering the influence of loading history. Carew et al. [27] has noted that cyclic preconditioning does not necessarily reset the strain history. A period of 24 hours of resting time is suggested between cyclic tests which are useful for fitting tan(δ). Since the zero-stress state is closely related to wall microstructure [28, 29] and the viscosity changes with remodeling [24, 30], we hypothesize that viscoelasticity is an important factor of vascular health and disease. A mathematical model similar to that developed by Rachev et al. [14] will be important to understand the relationship between physiology and mechanics. In future studies, more accurate results can be obtained by solving the boundary value problem with the viscoelastic constitutive equation.

In summary, we propose a generalized Maxwell model which captures the creep behavior of porcine LAD arteries. An advantage of the model is that the number of parameters does not increase with the number of Voigt bodies considered. This is because “intrinsic” relations between relaxation times and elastic moduli have been taken into consideration, see [21] for detailed interpretation. It is well known that the inclusion of too many parameters typically results in difficulties for data curve fitting. The temporal variations of opening angles of arteries cut from the loaded and no-load states were shown to be predictable from the strain recovery history. Theoretical and experimental results are in good qualitative agreement. Although the expressions of g(t) and j(t) are based on a linear stress-strain relation, the quasi-linear theory [3, 7, 31] still applies once these functions are determined. Besides, these functions can be modified to account for rate-sensitive hysteresis by changing the series of elastic moduli [21]. This means that the creep or relaxation function may be used to study the viscoelastic behavior of various soft tissues under general boundary conditions.

A full analysis of the boundary value problem requires detailed knowledge of elastic property, viscous behavior, and geometry for the vessel wall which are still unavailable. Here, we idealized the creep process to capture the salient mechanical responses under a large range of loadings. We are continuing to develop a model which is as simple as possible (with fewer parameters) and this study is a step towards a more complete viscoelastic model in the future.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported in part by the National Institute of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant 2 R01 HL055554-11 and HL84529. The authors would like to thank the Associate Editor for his helpful comments to improve the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chuong CJ, Fung YC. On Residual Stresses in Arteries. J. Biomech. Eng. 1986;108:189–192. doi: 10.1115/1.3138600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaishnav RN, Vossoughi J. Residual Stress and Strain in Aortic Segments. J. Biomech. 1987;20:235–239. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fung YC. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. 2nd ed. Springer; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rachev A, Greenwald SE. Residual Strains in Conduit Arteries. J. Biomech. 2003;36:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo XM, Lu X, Kassab GS. Transmural Strain Distribution in the Blood Vessel Wall. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circul. Physiol. 2005;288:H881–H886. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00607.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rehal D, Guo XM, Lu X, Kassab GS. Duration of No-Load State Affects Opening Angle of Porcine Coronary Arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circul. Physiol. 2006;290:H1871–H1878. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00910.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funk JR, Hall GW, Crandall JR, Pilkey WD. Linear and Quasi-Linear Viscoelastic Characterization of Ankle Ligaments. J. Biomech. Eng. 2000;122:15–22. doi: 10.1115/1.429623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holzapfel GA, Gasser TC, Stadler M. A Structural Model for the Viscoelastic Behavior of Arterial Walls: Continuum Formulation and Finite Element Analysis. Eur. J. Mech. A-Solids. 2002;21:441–463. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iatridis JC, Wu JR, Yandow JA, Langevin HM. Subcutaneous Tissue Mechanical Behavior Is Linear and Viscoelastic Under Uniaxial Tension. Connect. Tissue Res. 2003;44:208–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Findley WN, Lai JS, Onaran K. Creep and Relaxation of Nonlinear Viscoelastic Materials. Dover; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orosz M, Molnarka G, Monos E. Curve Fitting Methods and Mechanical Models for Identification of Viscoelastic Parameters of Vascular Wall - A Comparative Study. Med. Sci. Monit. 1997;3:599–604. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Kassab GS. A Bilinear Stress-Strain Relationship for Arteries. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1307–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Wang C, Kassab GS. The Mathematical Formulation of a Generalized Hooke's Law for Blood Vessels. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3569–3578. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rachev A, Stergiopulos N, Meister JJ. Theoretical Study of Dynamics of Arterial Wall Remodeling in Response to Changes in Blood Pressure. J. Biomech. 1996;29:635–642. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka TT, Fung YC. Elastic and Inelastic Properties of the Canine Aorta and Their Variations along the Aortic Tree. J. Biomech. 1974;7:357–370. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(74)90031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Recchia FA, Byrne BJ, Kass DA. Sustained Vessel Dilation Induced by Increased Pulsatile Perfusion of Porcine Carotid Arteries in Vitro. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1999;166:15–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veress AI, Vince DG, Anderson PM, Cornhill JF, Herderick EE, Kuban BD, Greenberg NL, Thomas JD. Vascular Mechanics of the Coronary Artery. Z. Kardiol. 2000;89:92–100. doi: 10.1007/s003920070106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silver FH, Snowhill PB, Foran DJ. Mechanical Behavior of Vessel Wall: A Comparative Study of Aorta, Vena Cava, and Carotid Artery. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2003;31:793–803. doi: 10.1114/1.1581287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berglund JD, Nerem RM, Sambanis A. Viscoelastic Testing Methodologies for Tissue Engineered Blood Vessels. J. Biomech. Eng. 2005;127:1176–1184. doi: 10.1115/1.2073487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, Zhang W, Kassab GS. The Validation of a Generalized Hooke's Law for Coronary Arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circul. Physiol. 2008;294:H66–H73. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00703.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang W, Chen HY, Kassab GS. A Rate Insensitive Linear Viscoelastic Model for Soft Tissues. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3579–3586. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu X, Yang J, Zhao JB, Gregersen H, Kassab GS. Shear Modulus of Porcine Coronary Artery: Contributions of Media and Adventitia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circul. Physiol. 2003;285:H1966–H1975. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00357.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, Garcia M, Lu X, Lanir Y, Kassab GS. Three-Dimensional Mechanical Properties of Porcine Coronary Arteries: A Validated Two-Layer Model. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circul. Physiol. 2006;291:H1200–H1209. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01323.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armentano RL, Graf S, Barra JG, Velikovsky G, Baglivo H, Sanchez R, Simon A, , RH, Levenson J. Carotid Wall Viscosity Increase Is Related to Intima-Media Thickening in Hypertensive Patients. Hypertension. 1998;31:534–539. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han HC, Fung YC. Species Dependence of the Zero-Stress State of Aorta - Pig Versus Rat. J. Biomech. Eng. 1991;113:446–451. doi: 10.1115/1.2895425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frobert O, Gregersen H, Bjerre J, Bagger JP, Kassab GS. Relation between Zero-Stress State and Branching Order of Porcine Left Coronary Arterial Tree. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circul. Physiol. 1998;275:H2283–H2290. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carew EO, Barber JE, Vesely I. Role of Preconditioning and Recovery Time in Repeated Testing of Aortic Valve Tissues: Validation Through Quasilinear Viscoelastic Theory. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2000;28:1093–1100. doi: 10.1114/1.1310221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu SQ, Fung YC. Relationship between Hypertension, Hypertrophy, and Opening Angle of Zero-Stress State of Arteries Following Aortic Constriction. J. Biomech. Eng. 1989;111:325–335. doi: 10.1115/1.3168386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu X, Zhao JB, Wang GR, Gregersen H, Kassab GS. Remodeling of the Zero-Stress State of Femoral Arteries in Response to Flow Overload. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circul. Physiol. 2001;280:H1547–H1559. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valenta J, Svoboda J, Valerianova D, Vitek K. Residual Strain in Human Atherosclerotic Coronary Arteries and Age Related Geometrical Changes. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 1999;9:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vena P, Gastaidi D, Contro R. A Constituent-Based Model for the Nonlinear Viscoelastic Behavior of Ligaments. J. Biomech. Eng. 2006;128:449–457. doi: 10.1115/1.2187046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]