Abstract

In rat diabetic animal models, ANG(1-7) treatment prevents the development of cardiovascular complications. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)2 is a major ANG(1-7)-generating enzyme in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and its expression is decreased by a prolonged exposure to high glucose (HG), which is reflected by lower ANG(1-7) levels. However, the underlying mechanism of its downregulation is unknown and was the subject of this study. Rat aortic VSMCs were maintained in normal glucose (NG) or HG (∼4.1 and ∼23.1 mmol/l, respectively) for up to 72 h. Several PKC and NADPH oxidase inhibitors and short interfering (si)RNAs were used to determine the mechanism of HG-induced ACE2 downregulation. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis, real-time quantitative PCR, and ANG(1-7) radioimmunodetection. At 72 h of HG exposure, ACE2 mRNA, protein, and ANG(1-7) levels were decreased (0.17 ± 0.01-, 0.47 ± 0.03-, and 0.16 ± 0.01-fold, respectively), and the expression of NADPH oxidase subunit Nox1 was increased (1.70 ± 0.2-fold). The HG-induced ACE2 decrease was reversed by antioxidants and Nox1 siRNA as well as by inhibitors of glycotoxin formation. ACE2 expression was PKC-βII dependent, and PKC-βII protein levels were reduced in the presence of HG (0.32 ± 0.03-fold); however, the PKC-βII inhibitor CG-53353 prevented the HG-induced ACE2 loss and Nox1 induction, suggesting a nonspecific effect of the inhibitor. Our data suggest that glycotoxin-induced Nox1 expression is regulated by conventional PKCs. ACE2 expression is PKC-βII dependent. Nox1-derived superoxides reduce PKC-βII expression, which lowers ACE2 mRNA and protein levels and consequently decreases ANG(1-7) formation.

Keywords: angiotensin-coverting enzyme 2/angiotensin-(1-7), NADPH oxidase, smooth muscle, vascular smooth muscle cells, glycotoxins, protein kinase C-βII

angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)2, the first human homolog of ACE described, is an integral membrane protein that functions as a carboxypeptidase, cleaving a single hydrophobic/basic residue from the COOH-terminus of its substrates (33). ACE2 hydrolyzes the potent vasoconstrictor peptide ANG II to ANG(1-7). Also, ACE2 hydrolyzes dynorphin A(1-13), apelin-13, and des-Arg9 bradykinin (36). In addition to ACE2, neprilysin has been reported to generate ANG(1-7) in vitro (25).

In the diabetic kidney, ACE2 expression is decreased by ∼50% (32), whereas loss of ACE2 accelerates diabetes-induced kidney injury (38). Decreased ACE2 expression has been reported in rat vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) treated with high glucose (HG) (18), suggesting that HG and/or glucose metabolites called glycotoxins reduce ACE2 expression, which, in turn, could amplify the vascular damage in diabetes. ANG(1-7) contributes to the antihypertensive effects produced by inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system, decreases the size of infarct and ischemic zones in experimental myocardial infarction, and prevents diabetes-induced cardiovascular dysfunction (2, 8, 12, 35). Indeed, in diabetic animal models, ANG(1-7) treatment reduces or prevents the development of diabetes-induced cardiovascular injury (2, 35).

Several biochemical mechanisms have been identified in the pathogenesis of hyperglycemia-induced vascular damage: 1) increased flux via the polyol pathway (22); 2) accelerated formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) (6, 41); 3) NADPH oxidase-associated oxidative stress (22, 27, 29); and 4) excessive PKC activation (10).

In VSMCs, expression of the polyol pathway key enzyme aldose reductase is upregulated by HG (18), and sorbitol accumulation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy and vascular injury (22). Simultaneously, AGEs are prevalent in the diabetic vasculature and contribute to the development of macrovascular complications (27, 41). AGEs are proteins or lipids that become nonenzymatically glycated in a Maillard reaction after an exposure to reducing sugars (6, 21). Polyol pathway activation and intracellular AGE accumulation lead to oxidative stress (22, 26, 27). In VSMCs, polyol pathway-dependent (29) and AGE-induced (26) increases of NADPH oxidase activity have been reported. ROS formed by NADPH oxidase are important signaling molecules (7). Many of the cellular perturbations initiated by AGEs are mediated by ROS (41).

In the arterial wall, NADPH oxidases are the main source of ROS (7, 37). In rodent VSMCs, two NADPH oxidase forms are present (9). Nox1-based oxidase, localized in calveolae, consists of membrane-bound and cytosolic regulatory components. Nox4-based oxidase, found in focal adhesions and the nucleus, is without known cytosolic subunits (4, 9). AGEs and ANG II induce Nox1 expression, whereas Nox4 is downregulated by the same treatments (26, 17). In contrast to Nox1, Nox4-derived superoxides sustain VSMC differentiation, indicating that the source and location of ROS production are of paramount importance in dictating the cellular response (4, 20, 28). Suppression of renal NADPH oxidase is considered a pharmacological target for treating diabetic nephropathy (34).

Hyperglycemia also increases intracellular levels of diacylglycerol (DAG), which activates PKC in various tissues associated with diabetic vascular complications, including the retina, aorta, heart, and renal glomeruli (10, 15, 30, 31). However, different PKC isoforms respond differently to hyperglycemia (30). In particular, PKC-βII activation has been reported to lead to various pathological effects that affect VSMC function (10). Clinical evaluations of selective PKC-βII inhibitors have revealed its beneficial effects for treating diabetic microvascular complications (1, 10, 31).

Therefore, we hypothesized that HG-induced alternations of the above-discussed biochemical mechanisms might participate in the HG-induced downregulation of ACE2 expression and the subsequent decrease of ANG(1-7) formation in rat VSMCs. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effect of inhibitors of glucose transporter (GLUT)1, NADPH oxidase, and PKC-βII on HG-induced downregulation of ACE2 and ANG(1-7) formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

FBS, medium 199 (M199), penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.05% trypsin were obtained from Mediatech. Elastase, collagenase, and d-glucose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The list of chemical inhibitors used in present study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of chemical inhibitors

| Compound | Source | Biological Effect | Final Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochalasin B | Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. C6762) | Glucose transporter inhibitor | 1 μmol/l |

| Catalase | Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. C9322) | ROS scavenger | 150–200 U/ml |

| Apocynin | Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. W508454) | NADPH oxidase inhibitor/general antioxidant | 10 μmol/l |

| Diphenyleneiodonium | Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. D2926) | NADPH oxidase inhibitor/general flavoprotein inhibitor | 1 μmol/l |

| Aminoguanidine | Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. 396494) | Advanced glycation end-product formation inhibitor | 10 μmol/l |

| Alrestatin | Tocris Bioscience (catalog no. 0485) | Aldose reductase inhibitor | 10 μmol/l |

| CG-53353 | EMD Chemicals (catalog no. 539652) | PKC-βII inhibitor | 100 nmol/l |

| Gö-6976 | EMD Chemicals (catalog no. 365250) | Conventional PKC isoform inhibitor | 1 μmol/l |

| Calphostin C | BioMol (catalog no. EI198-0100) | Nonspecific (pan) PKC inhibitor | 100 nmol/l |

Rat Aortic VSMC Isolation and Culture

Experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles Rivers, Wilmington, MA), weighing 200–250 g, were anesthetized with 60 mg/kg ip pentobarbital sodium. Under aseptic conditions, the thoracic aorta was rapidly removed and incubated for 30 min in 5 mg/ml collagenase; afterward, the adventitia and intima were dissected, and the mixture was minced. Single VSMCs were separated by an incubation in 0.25 mg/ml elastase with 5 mg/ml collagenase for two 90-min periods at 37°C with gentle shaking and then plated in 60-mm dishes (MIDSCI) in M199 containing 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin in humidified conditions under 5% CO2. Confluent cells were passaged by trypsinization with 0.05% trypsin; passages 4–5 were used for experiments. After cells reached confluence, the medium was replaced with serum-free M199 for 24 h. The next day, the medium was replaced once more with fresh serum-free M199, and cells were kept overnight before any treatment was begun. The VSMC phenotype was characterized by immunostaining using anti-smooth muscle α-actin antibody. We found that after 24 h of VSMC incubation with media containing normal glucose (NG) or plain M199, the concentration of glucose in the medium decreased from 5.5 to ∼2.8 mmol/l. Plain M199 enriched with d-glucose up to glucose concentration of 25 mmol/l was termed as HG media. In HG media, the glucose concentration decreased from 25 to ∼21.4 mmol/l within 24 h (data not shown). Therefore, 50% of the medium was replaced every 12 h to maintain the concentration of glucose at ∼4.1 (NG) and ∼23.1 mmol/l (HG). Cells were harvested for either mRNA or total protein isolation at the following time points: 0, 2, 4, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h. Collected culture medium was used for glucose concentration assay or protein extraction using iCON concentrators (Pierce Biotechnology).

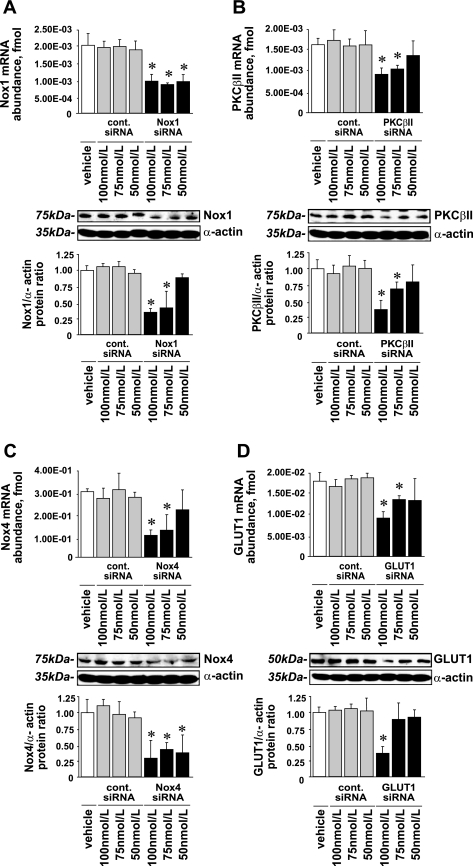

VSMC Transfection With Short Interfering RNA

SMARTpool short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for silencing the expression of target genes and cyclophilin B siRNA as a negative control were purchased from Dharmacon. All transfections were carried out using the manufacturer's protocol with DharmaFECT1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon). Briefly, VSMCs were trypsinized, counted, and plated at a density of 104 cells/cm2 in six-well plates (MIDSCI) in antibiotic-free M199 with 10% FBS and incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. The next morning, when cells had reached ∼40% confluence, the medium was replaced, and cells were transfected with 50, 75, or 100 nmol/l of SMARTpool siRNA or control siRNA using 6 μl of DharmaFECT1 reagent/well (Fig. 1). After 72 h, 1 ml of fresh medium was added; after 96 h, the transfection medium was replaced. Cells were washed twice with serum-free M199 and then subjected to NG or HG for 72 h as described above. The efficiency of siRNAs to silence target gene expression as determined by real-time quantitative PCR and Western blot analysis is shown in Fig. 1.

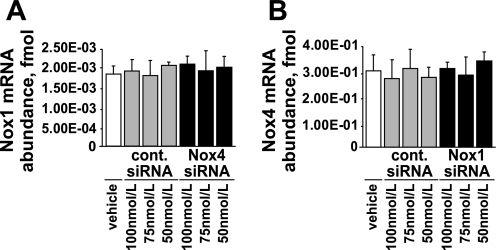

Fig. 1.

Nox1, Nox4, PKC-βII, and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) short interfering (si)RNA efficiency. Subconfluent rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) were transfected in 6-well plates with siRNA for Nox1, Nox4, PKC-βII, GLUT1, or cyclophilin B (control siRNA) for 96 h. A: Nox1 expression; B: PKC-βII expression; C: Nox4 expression; D: GLUT1 expression. Data are shown as mRNA abundance and protein levels for each target gene (means ± SE; n = 4). *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding value with control siRNA.

RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Cells were homogenized in 4 ml of RNA-Stat 60 (Tel-Test), and RNA isolation was carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA samples were precipitated with 95% ethanol and dissolved in 200 μl diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-water. To decrease genomic DNA contamination, samples were treated with DNase-I (Ambion) and stored at −80°C. For cDNA synthesis, we used 10 μl of DNA-free total RNA, 1 μl of random hexamers, and 1 μl of dNTPs with 1 μl of Superscript reverse transcriptase-III RNase H(-) (Invitrogen). Total cDNA samples were diluted in DEPC-water (1:100) and analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR on an iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories). PCR primers were designed to have ∼20 nucleotides and ∼50% or less of G/C content with a melting point lower than 62°C (Table 2). Amplification sequences were shorter than 75 nucleotides. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 μl consisting of 12.5 μl of 2× FastStart SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche Diagnostic), 2.5 μl of each primer (100 nmol/l final concentration, Integrated DNA Technologies), and 7.5 μl of cDNA (∼90–100 pg of total cDNA). We used a real-time quantitative PCR protocol with 10 min of 95°C denaturation followed by 40 amplification cycles with an annealing temperature of 62°C and extension at 65°C. Each time the melting point of the PCR product was checked to avoid nonspecific amplification. PCR efficiency for each reaction was between 96% and 100%. For exogenous controls, we used standard sequences for each cDNA of ∼90 nucleotides long, which included the amplification target and five to seven nucleotides at the 3′- and 5′-ends to allow primer annealing (Integrated DNA Technologies) in serial dilutions of 10−5 to 10−13 pmol/l. For the endogenous control, 18S RNA was used. Gene mRNA expression levels were presented as femtomoles of the target gene mRNA per 1 pmol of 18S RNA.

Table 2.

Primers designed for real-time quantitative PCR and mRNA sequence accession numbers in GenBank

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | GenBank Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18S RNA | 5′-5CCGCAGCTAGGAATAATGGA-3′ | 5′-CCCTCTTAATCATGGCCTCA-3′ | X01117 |

| ACE2 | 5′-CTTACGAGCCTCCTGTCACC-3′ | 5′-AATGCCAACCACTACCGTTC-3′ | NM_001012006 |

| PKC-β | 5′-AACGGCTTGTCAGATCCCTA-3′ | 5′-TGGTCTTCTGCTTGCTCTCA-3′ | NM_012713 |

| Nox1 | 5′-TTCCCTGGAACAAGAGATGG-3′ | 5′-CCAGCCAGTGAGGAAGAGTC-3′ | NM_053683 |

| Nox4 | 5′-CCACAGACCTGGATTTGGAT-3′ | 5′-CGGATGCATCGGTAAAGTCT-3′ | NM_053524 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; Nox, NADPH oxidase isoform.

Preparation of Cell Lysates and Conditioned Media

Cells were harvested and lysed in 250 μl of 1× RIPA lysis buffer (Upstate) containing 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM NaF, 10 μg/ml antipain, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 10 μg/ml captopril. The culture medium was collected in iCON concentrators (Pierce Biotechnology) and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 20 min. The resulting protein extract was resuspended with 250 μl of 1× RIPA buffer and is referred to as “conditioned media.” Subsequent to sonication, samples were cleared by centrifugation, and the protein concentration was determined with Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Western Blot Analysis

Equal amounts of protein per well (∼15 μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto pure nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 mm, Bio-Rad Laboratories). Membranes were blocked with primary antibodies (1:200–1:20,000) overnight at 4°C (Table 3). The next day, membranes were exposed to their respective secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:1,000–1:2,000), and films (Molecular Technologies) were developed using SuperSignal WestPico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology). The density of the bands was analyzed using NIH ImageJ software. For assurance of equal gel loading, membranes were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Pierce Biotechnology) and reprobed with anti-α-actin antibody.

Table 3.

Western blot conditions and list of antibodies used in the present study

| Antigen | Source | Host Animal | Blocking Buffer | Primary Antibody Dilution | Secondary Antibody Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-17719) | Goat | 7% milk | 1:300 | 1:1,500 |

| Nox1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-5821) | Goat | 7% milk | 1:300 | 1:1,500 |

| Nox4 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-30141) | Rabbit | 7% milk | 1:500 | 1:1,000 |

| PKC-βI | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-209) | Rabbit | 7% milk | 1:1,000 | 1:1,000 |

| Phospho-PKC-βII | Upstate (catalog no. 07-873) | Rabbit | 5% BSA | 1:1,000 | 1:1,000 |

| PKC-βII | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-210) | Rabbit | 7% milk | 1:300 | 1:1,000 |

| Phospho-EGFR | Cell Signaling Technology (catalog no. 2236) | Rabbit | 3% BSA | 1:1,000 | 1:1,000 |

| EGFR | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-03) | Rabbit | 5% milk | 1:1,000 | 1:1,000 |

| VSMC α-actin | Sigma-Aldrich (catalog no. A5228) | Mouse | 1% casein (Bio-Rad) | 1:20,000 | 1:1,000 |

| Anti-rabbit antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-2313) | Donkey | 7% milk | ||

| Anti-goat antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-2020) | Donkey | 7% milk | ||

| Anti-mouse antibody | GE Healthcare (catalog no. NXA 931) | Sheep | 7% milk |

EGFR, EGF receptor; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses, including means ± SE, were determined using GraphPad 4 software (GraphPad Software). Data were analyzed using ANOVA. The Newman-Keuls test was used for multiple comparisons. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

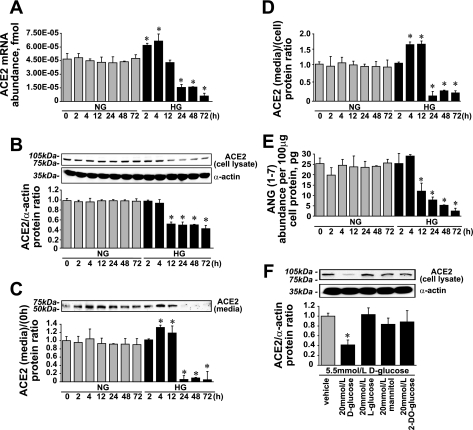

HG Decreased ACE2 mRNA Expression, ACE2 Protein, and ANG(1-7) Levels in Rat VSMCs

We have previously shown that in VSMCs, ACE2 expression is downregulated by HG (18). In present study, we confirmed this observation and performed experiments to elucidate the mechanism of HG-induced ACE2 downregulation. Initially, HG increased ACE2 mRNA expression by 1.71 ± 0.57-fold with a subsequent decrease after 12 h by >7-fold compared with NG (Fig. 2A). In cell lysates, ACE2 protein levels were reduced after 4 h of HG treatment and at 72 h reached 0.47 ± 0.03-fold of the value obtained in the presence of NG (Fig. 2B). In conditioned media within the first 12 h, ACE2 protein levels increased by 1.34 ± 0.21-fold and were almost undetectable thereafter (Fig. 2C). The ACE2 protein (media/cell) ratio reflects ACE2 shedding from cell surface, which was upregulated by 1.79 ± 0.33-fold within the first 12 h of HG treatment and was 0.25 ± 0.02-fold thereafter versus NG (Fig. 2D). ANG(1-7) levels were lowered by more than a half after 4 h of HG treatment and reached 0.16 ± 0.03-fold versus the value obtained in the presence of NG at 72 h (Fig. 2E). To eliminate the osmolar effect of 25 mmol/l d-glucose on ACE2 expression, mannitol, l-glucose, and 2-deoxyglucose were applied as osmolarity controls (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Effect of high glucose (HG) on angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)2 expression and ANG(1-7) formation. A: ACE2 mRNA expression (means ± SE; n = 9). B: ACE2 protein levels in cell lysates (means ± SE; n = 11). C: ACE2 protein levels in cultured media (means ± SE; n = 4). D: ACE2 protein (media/cell) ratio (means ± SE; n = 4). E: ANG(1-7) levels in cell lysates (means ± SE; n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding value in the presence of normal glucose (NG). F: ACE2 protein levels in cell lysates. Mannitol, l-glucose, and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DO-glucose) were used as an osmotic controls (means ± SE; n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

Inhibition of Glucose Uptake and/or Glycotoxin Accumulation by Rat VSMCs Diminished the Effect of HG on ACE2 Expression and ANG(1-7) Levels

In this experiment, we used 1 μmol/l cytochalasin B to inhibit glucose uptake (Fig. 3A), 10 μmol/l aminoguanidine to prevent the formation of AGEs (Fig. 3B), and 10 μmol/l alrestatin (an aldose reductase inhibitor) (Fig. 3C). All three compounds diminished the HG effect on ACE2 expression. Although cytochalasin B and aminoguanidine fully reversed the HG effect, alrestatin was only partially effective. Alrestatin minimized the effect of HG on ACE2 mRNA and ACE2 protein levels but did not prevent ANG(1-7) loss in the presence of HG (Fig. 3D). In addition to chemical inhibitors, we silenced GLUT1 expression (Fig. 1D), which diminished the effect of HG on ACE2 mRNA expression and protein levels (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Cytochalasin B, alrestatin, and aminoguanidine diminish the effect of HG on ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) levels. A: effect of 1 μmol/l cytochalasin B on ACE2 expression in the presence of HG. B: effect of 10 μmol/l aminoguanidine on ACE2 expression in the presence of HG. C: effect of 10 μmol/l alrestatin on ACE2 expression in the presence of HG (means ± SE; n = 3). †P < 0.05 vs. 0 h; *P < 0.05 vs. HG alone at the corresponding time points. D: effect of inhibitors on endogenous ANG(1-7) formation (means ± SE; n = 3). †P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of NG; *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of HG; #P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding treatment in the presence of NG.

Fig. 4.

GLUT1 siRNA diminishes the effect of HG on ACE2 mRNA expression and ACE2 protein levels. Shown are the effects of GLUT1 silencing on ACE2 expression in the presence of HG (means ± SE; n = 3). †P < 0.05 vs. 0 h; *P < 0.05 vs. the value at corresponding time points where cells were treated with HG alone.

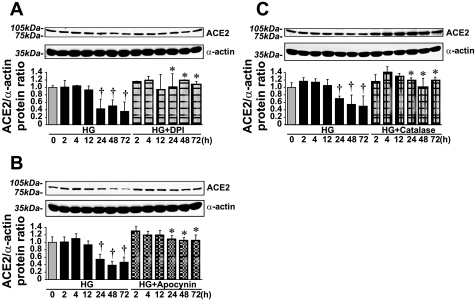

HG-Induced Downregulation of ACE2 Expression and ANG(1-7) Levels Was Minimized by NADPH Oxidase Inhibitors/General Antioxidants and Nox1 siRNA

The effect of HG on ACE2 and ANG(1-7) levels was fully reversed by the ROS scavenger catalase (150–200 U/ml), the antioxidant apocynin (10 μmol/l), and the flavoprotein inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium (DPI; 1 μmol/l) (Fig. 5). However, the very same treatments decreased ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) levels in the presence of NG (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

NADPH oxidase inhibitors/general antioxidants and catalase diminished the effect of HG on ACE2 protein levels. A: ACE2 protein levels in VSMCs treated with 1 μmol/l diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) in the presence of HG (means ± SE; n = 5). B: ACE2 protein levels in VSMCs treated with 10 μmol/l apocynin in the presence of HG (means ± SE; n = 3). C: treatment with 150–200 U/ml catalase diminished the effect of HG on ACE2 protein levels (means ± SE; n = 7). *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding value in the presence of HG alone; †P < 0.05 vs. the 0-h value.

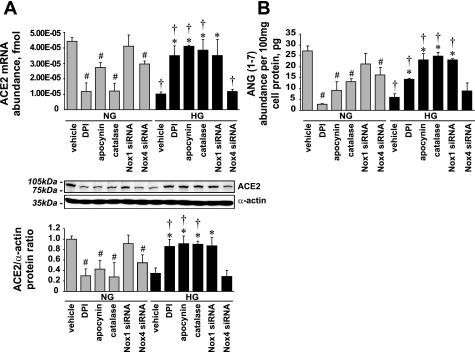

Fig. 6.

Effect of NADPH oxidase inhibitors, Nox1 and Nox4 siRNA, or catalase on ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) levels. A: ACE2 mRNA expression and protein levels (means ± SE; n = 3). B: ANG(1-7) levels (means ± SE; n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of HG; †P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding treatment in the presence of NG; #P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of NG.

Two forms of NADPH oxidase (Nox1 based and Nox4 based) are present in rodent VSMCs (9). To evaluate the contribution of each NADPH oxidase in HG-induced ACE2 downregulation, we silenced Nox1 and Nox4 expression with siRNA (Fig. 1, A and C). Nox1 siRNA did not reduce Nox 4 mRNA levels, and Nox 4 siRNA did not alter Nox 1 mRNA levels (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Specificity of Nox1 and Nox4 siRNA. A: effect of Nox4 siRNA on Nox1 mRNA expression. B: effect of Nox1 siRNA on Nox4 mRNA expression. Data are means ± SE; n = 3.

Nox4 silencing decreased ACE2 mRNA, ACE2 protein, and ANG(1-7) levels in the presence of NG (0.73 ± 0.08-, 0.55 ± 0.04-, and 0.62 ± 0.04-fold vs. vehicle, respectively) but had no effect on ACE2 expression in the presence of HG (Fig. 6). Unlike Nox4, Nox1 silencing diminished the effect of HG on ACE2 expression and increased ACE2 mRNA, ACE2 protein, and ANG(1-7) levels in the presence of HG (3.35 ± 0.5-, 2.35 ± 0.22-, and 3.47 ± 0.09-fold vs. vehicle, respectively) but did not affect ACE2 expression or ANG(1-7) levels in the presence of NG (Fig. 6).

ACE2 Expression Was PKC-βII Dependent: Effect of PKC Inhibitors and PKC-βII siRNA on ACE2 Expression and ANG(1-7) Levels

Biochemical mechanisms involved in hyperglycemia-induced vascular damage include impaired PKC-dependent intracellular signaling (10). Therefore, we tested whether PKC inhibitors would prevent HG-induced ACE2 and ANG(1-7) loss.

In the presence of HG, 100 nmol/l calphostin C (a pan PKC inhibitor) did not affect ACE2 and ANG(1-7) levels but in the presence of NG downregulated ACE2 mRNA, ACE2 protein, and ANG(1-7) levels (0.14 ± 0.03-, 0.35 ± 0.03-, and 0.35 ± 0.02-fold vs. vehicle, respectively; Fig. 8, A and C).

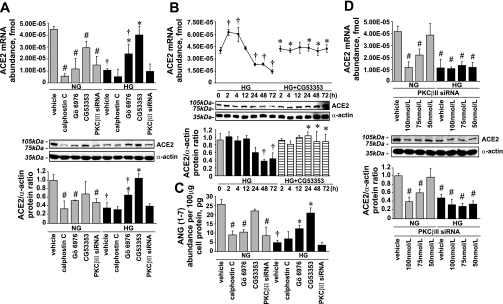

Fig. 8.

Effect of PKC inhibitors and PKC-βII siRNA on ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) levels in the presence of NG or HG. A: ACE2 mRNA expression (means ± SE; n = 3) and protein levels (means ± SE; n = 4). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of HG; †P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding treatment in the presence of NG; #P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of NG. B: ACE2 mRNA expression (means ± SE; n = 3) and protein levels (means ± SE; n = 5). *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding time point in the presence of NG; †P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of NG. C: ANG(1-7) levels in cell lysates (means ± SE; n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of HG; †P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of NG; #P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of NG. D: effect of PKC-βII silencing on ACE2 mRNA expression and protein levels in the presence of NG or HG (means ± SE; n = 3). #P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of NG.

Similar to calphostin C, 1 μmol/l Gö-6976 (a conventional PKC isoform inhibitor) downregulated ACE2 mRNA, ACE2 protein, and ANG(1-7) levels in the presence of NG (0.29 ± 0.06-, 0.57 ± 0.01-, and 0.50 ± 0.03-fold vs. vehicle, respectively). However, in the presence of HG, Gö-6976 prevented the decrease of ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) levels (Fig. 8, A and C).

The effect of HG on ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) levels was fully reversed by 100 nmol/l CG-53353 (a selective PKC-βII inhibitor), whereas in the presence of NG, CG-53353 slightly downregulated ACE2 mRNA expression (Fig. 8, A–C). To confirm the selectivity of the effect of CG-53353 on ACE2 expression, PKC-βII expression was silenced with siRNA (Fig. 1B). The effects of PKC-βII siRNA and CG-53353 on ACE2 mRNA expression, ACE2 protein, and ANG(1-7) levels were contradictory. In contrast to CG-53353, PKC-βII silencing decreased ACE2 mRNA, ACE2 protein, and ANG(1-7) levels in the presence of NG (0.35 ± 0.07-, 0.55 ± 0.02-, and 0.37 ± 0.2-fold vs. vehicle, respectively) but did not affect ACE2 levels in the presence of HG (Fig. 8, A and C). Moreover, in presence of NG, the ACE2 decrease correlated with the level of PKC-βII silencing (Fig. 8D), whereas in presence of HG, when PKC-βII was already downregulated, PKC-βII silencing had no effect on ACE2 expression.

HG Induces Nox1 and Decreases Nox4 Expression; Effect of HG on Nox1 Expression Was Diminished by Cytochalasin B, Aminoguanidine, and PKC Inhibitors But Not by PKC-βII siRNA or Alrestatin

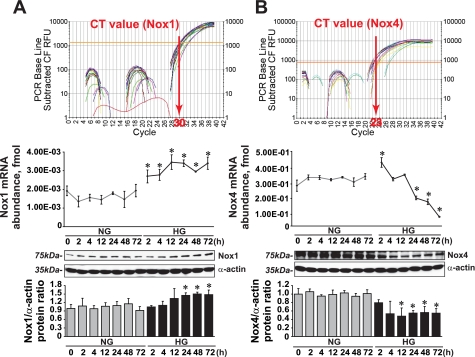

HG induced Nox1 mRNA and protein levels (1.70 ± 0.22- and 1.62 ± 0.10-fold vs. NG at 72 h, respectively) and downregulated Nox4 mRNA and protein levels (0.29 ± 0.01- and 0.43 ± 0.01-fold vs. NG at 72 h, respectively) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Effect of HG on Nox1 and Nox4 expression. A: Nox1 mRNA abundance and protein levels (means ± SE; n = 4). B: Nox4 mRNA abundance and protein levels (means ± SE; n = 3). CT, threshold cycle. *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding value in the presence of NG.

The effect of HG on Nox1 levels was diminished by 1 μmol/l cytochalasin B and 10 μmol/l aminoguanidine, whereas 10 μmol/l alrestatin had only a partial inhibitory effect (Fig. 10A). These compounds did not affect Nox1 levels in the presence of NG.

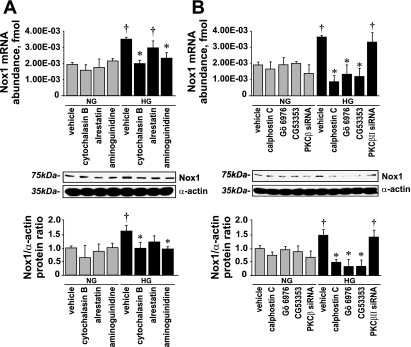

Fig. 10.

Effect of cytochalasin B, alrestatin, aminoguanidine, PKC inhibitors, and PKC-β siRNA on Nox1 expression. A: Nox1 mRNA abundance and protein levels (means ± SE; n = 5). B: Nox1 mRNA and protein levels (means ± SE; n = 4). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of HG; †P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding value in the presence of NG.

The PKC inhibitors calphostin C, Gö-6976, and CG-53353 effectively diminished the effect of HG on Nox1 expression, whereas none of the PKC inhibitors affected Nox1 expression in the presence of NG. In contrast to CG-53353, PKC-βII silencing did not affect Nox1 expression in the presence of HG (Fig. 10B).

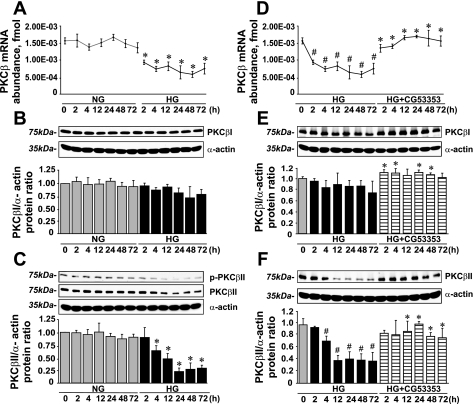

HG Decreases PKC-β mRNA Expression and Switches PKC-β Splicing Toward the PKC-βI Isoform; This Effect of HG Was Diminished by CG-53353

In rat VSMCs, both PKC-β splicing isoforms are expressed (29). Consequently, we found that HG decreased PKC-β mRNA abundance (0.47 ± 0.02-fold vs. NG; Fig. 11A) and affected PKC-β mRNA splicing toward PKC-βI. Thus, in the presence of HG, PKC-βII protein levels were decreased (0.32 ± 0.02-fold vs. NG; Fig. 11C), whereas PKC-βI levels remained unchanged (Fig. 11B). These changes in PKC-β mRNA expression and PKC-βI and PKC-βII protein levels were diminished by CG-53353 (Fig. 11, D–F).

Fig. 11.

CG-53353 diminished the effect of HG on PKC-β mRNA expression and PKC-β isoform splicing. A: PKC-β mRNA expression (means ± SE; n = 4). B: PKC-βI protein levels (means ± SE; n = 4). C: phospho- and total PKC-βII protein levels (means ± SE; n = 4). D: effect of CG-53353 on PKC-β mRNA expression in the presence of HG (means ± SE; n = 7). E and F: effect of CG-53353 on PKC-βI and PKC-βII protein levels in VSMCs in the presence of HG (means ± SE; n = 4). *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding value in the presence of NG; #P < 0.05 vs. the 0-h value.

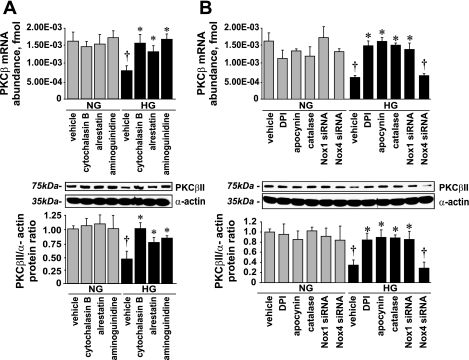

HG-Induced PKC-βII Downregulation Was Reversed by NADPH Oxidase Inhibitors/Antioxidants, Nox1 Silencing, and by Prevention of Glycotoxin Accumulation

Our data suggest that ACE2 expression is PKC-βII dependent (Fig. 8D) and HG downregulates PKC-βII levels (Fig. 11C). Therefore, we postulated that the inhibition of glycotoxin formation and/or NADPH oxidase-derived oxidative stress stimulated by glycotoxin accumulation should diminish the HG-induced PKC-βII downregulation, which subsequently reduces ACE2 expression, as previously observed (Figs. 3–6).

Cytochalasin B, alrestatin, or aminoguanidine reversed the effect of HG on PKC-βII expression (Fig. 12A) as well as DPI, apocynin, catalase, and Nox1 siRNA (Fig. 12B), whereas Nox4 silencing did not affect PKC-βII levels (Fig. 12B). Neither NADPH oxidase inhibitors, nor catalase, nor Nox1 siRNA affected PKC-βII expression in the presence of NG.

Fig. 12.

Effect of cytochalasin B, alrestatin, aminoguanidine, and NADPH oxidase inhibition on PKC-βII expression. A: PKC-β mRNA expression and PKC-βII protein levels (means ± SE; n = 5). B: PKC-β mRNA and PKC-βII protein levels (means ± SE; n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in the presence of HG; †P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding treatment in the presence of NG.

DISCUSSION

Despite great improvements in the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes, the majority of these patients still die because of the progression of diabetes-induced cardiovascular complications.

In animal models, the development of diabetic cardiovascular injury was prevented by ACE2 overexpression or by treatment with ANG(1-7), which makes ACE2 and ANG(1-7) potential pharmacological targets for the prevention/treatment of diabetes-induced cardiovascular complications (5, 8, 12, 35, 38).

ACE2 abundance/activity can be regulated via two distinct mechanisms: short term (fast), resulting from ACE2 shedding from the cell surface, and long term (slower), involving the regulation of ACE2 expression (16). In rat VSMCs, HG downregulates ACE2 expression (18). Our present results suggest that HG affects both mechanisms and results in rapid ACE2 shedding (Fig. 2, C and D) and downregulation of ACE2 mRNA expression (Fig. 2A), which subsequently decreases ANG(1-7) formation (Fig. 2E). Likewise, ACE2 expression was decreased by ∼50% in diabetic renal tubules (32).

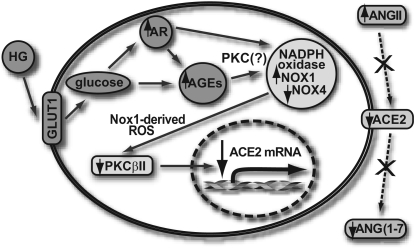

Our study was performed to elucidate the mechanism by which HG downregulates ACE2 expression in rat VSMCs. Three biochemical pathways (glycotoxin influx, NADPH oxidase-associated oxidative stress, and HG-impaired PKC signaling) were studied. The proposed mechanism of HG-induced ACE2 downregulation is shown as a diagram in Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Proposed mechanism of HG-induced ACE2 downregulation and ANG(1-7) formation. AR, aldose reductase; AGEs, advanced glycation end-products.

HG Influx and/or Glycotoxin Accumulation Initiate the Whole Cascade That Downregulates ACE2 Expression and ANG(1-7) Formation

Glycotoxin influx plays the key role in HG-induced ACE2 downregulation (Fig. 2, A and B). Silencing of GLUT1 expression (Fig. 4) or inhibition of AGEs and sorbitol formation with chemical inhibitors (Fig. 3) prevented the HG-induced changes in Nox1 (Fig. 10) and PKC-βII (Fig. 11) expression that attenuated the effect of HG on ACE2 and ANG(1-7) levels. The HG-induced decrease in ACE2 expression was not due to increased osmolarity because l-glucose, mannitol, or 2-deoxyglucose in similar concentrations as d-glucose did not alter ACE2 expression (Fig. 2F).

HG Downregulates Nox4 and Increases Nox1 Expression, and Nox1-Derived Superoxides Mediate HG-Induced ACE2 Downregulation

In our study, HG increased Nox1 and decreased Nox4 expression (Fig. 9). The HG-induced Nox1 increase was inhibited by GLUT1 siRNA, cytochalasin B, aminoguanidine, and alrestatin, suggesting the involvement of AGEs in Nox1 expression. Alrestatin was much less effective (Fig. 10A), which could be due to a posttranscriptional modification of aldose reductase, such as S-thiolation, which makes this enzyme less sensitive to inhibitors (3). Similarly to HG, ANG II (17) and AGEs (26) increase Nox1 and downregulate Nox4 expression in VSMCs, suggesting the involvement of identical pathways. Indeed, in the vascular wall, ANG II, AGEs, and HG share proinflammatory and proatherosclerotic activities (41, 29, 27).

HG and glycotoxins stimulate NADPH oxidase-dependent superoxide formation in VSMCs and cause oxidative stress (6, 22, 26, 27, 41). Our finding that the general antioxidant inhibitor apocynin, the flavoprotein inhibitor DPI, and the ROS scavenger catalase blocked the HG effect on ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) levels suggests that the effect of HG is mediated via ROS (Fig. 5). Silencing of Nox1 prevented the HG-induced decrease in ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) formation, suggesting that Nox1-derived ROS mediate this effect of HG (Fig. 6).

In contrast to Nox1, Nox 4 silencing had no effect on the HG-induced decrease in ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) production (Fig. 6). However, in the presence of NG, Nox4 silencing and NADPH oxidase inhibitors decreased ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) levels, suggesting that Nox4-derived superoxides are required for maintaining ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) formation in VSMCs (Fig. 6). In fact, Nox4-derived superoxides are required for maintaining the differentiated VSMC phenotype (4).

Contribution of HG-Impaired PKC Signaling in the Downregulation of ACE2 Expression: Distinct Effects of Different PKC Inhibitors and PKC-βII siRNA

Glycotoxin-driven Nox1 upregulation is dependent on conventional PKC isoform(s).

In our study, calphostin C [a nonspecific (pan) PKC inhibitor], Gö-6976 (a conventional PKC isoform inhibitor), and CG-53353 (a PKC-βII inhibitor) prevented the HG-induced Nox1 mRNA increase (Fig. 10B), suggesting that conventional PKC isoform(s) is(are) responsible for increased Nox1 expression, as previously reported (17). However, PKC-βII silencing did not affect Nox1 levels in the presence of HG, suggesting that PKC-βII does not mediate HG-induced Nox1 upregulation and that the effect of CG-53353 is nonspecific (Fig. 10B).

Calphostin C, Gö-6976, and CG-533353 inhibit different PKC isoforms (Table 1). Therefore, their specificity in diminishing HG-induced Nox1 upregulation must be a subject of future studies. In fact, the question of which PKC(s) is(are) responsible for NADPH oxidase activation/upregulation by HG is still an open issue (10, 15, 23, 29, 39).

HG decreases PKC-β expression and switches PKC-β isoform splicing toward PKC-βI; ACE2 expression is PKC-βII dependent.

PKC-βI and PKC-βII are splice isoforms of PKC-β mRNA (24) with opposing functions (40). It has been previously reported that PKC-βII is preferentially activated in tissues susceptible to diabetes-induced injury (11, 29, 39). However, our results demonstrate that HG downregulates PKC-β mRNA expression and switches PKC-β isoforms splicing toward PKC-βI (Fig. 11, A and B), whereas phospho-PKC-βII and total PKC-βII levels are decreased by >62% (Fig. 11C). In accordance with our observation, HG-induced PKC-βII downregulation accelerates VSMC proliferation, whereas HG does not affect PKC-βI levels (23). In the diabetic kidney cortex, the abundance of membrane-associated PKC-βII (the active form) is decreased by 50.00 ± 11.68% (42).

In the presence of NG, calphostin C, Gö-6976, and CG-53335 decreased ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) formation, suggesting that ACE2 expression is conventional PKC dependent (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, in the presence of NG, 100 nmol/l of PKC-βII siRNA produced a greater decrease in PKC-βII and ACE2 expression compared with that caused by 75 nmol/l PKC-βII siRNA (Fig. 8D), whereas 50 nmol/l PKC-βII siRNA did not affect PKC-βII expression (Fig. 1B) and subsequently did not change ACE2 expression in VSMCs (Fig. 8D). Thus, the correlation between the level of PKC-βII and ACE2 expression suggests that ACE2 expression is PKC-βII dependent (Fig. 8D).

In the presence of HG, Gö-6976 and CG-53353 diminished the ACE2 decrease, indicating that HG-induced downregulation of ACE2 expression is mediated via conventional PKC (Fig. 8A). However, PKC-βII activation/upregulation could not be responsible for HG-induced ACE2 downregulation for the following reasons: 1) PKC-βII activity/expression was downregulated in the presence of HG (Fig. 11C), and 2) PKC-βII silencing did not attenuate the HG-induced ACE2 decrease (Fig. 8D). These results suggest that the effect of the PKC-βII inhibitor CG-533353 to diminish HG-induced ACE2 downregulation is due to its nonspecific effect mediated through a non-PKC-βII-dependent pathway (Fig. 8B).

Specificity of the “selective” PKC-βII inhibitor CG-533353: protective effects of “selective” PKC-βII inhibitors could be due to their non-PKC-βII-dependent pathways.

Despite the fact that, in clinical trials, PKC-βII inhibitors have been shown to improve diabetes-induced cardiovascular damage, they are known to have other nonspecific effects. In our study, CG-53353 and PKC-βII siRNA exerted opposite effects on ACE2 and Nox1 expression and ANG(1-7) levels. Thus, in the presence of HG, CG-53353 prevented the ACE2 loss and ANG(1-7) decrease, whereas PKC-βII siRNA did not (Fig. 8, B and C). In the presence of NG, CG-53353 slightly downregulated ACE2 mRNA abundance (Fig. 8A), whereas PKC-βII siRNA decreased ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) levels (Fig. 8D), suggesting that ACE2 expression is PKC-βII dependent, whereas the CG-53353 effect on ACE2 expression in the presence of HG is PKC-βII independent. For example, the PKC-βII inhibitor LY-333531, which is undergoing a clinical trial phase III (1, 31), forms a complex with and inhibits 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase (PDK)-1, a key kinase for the insulin signaling pathway (14). DAG-dependent PKC activation is a key factor for hyperglycemia-induced vascular damage (10, 30). Insulin decreases DAG levels and slows the progression of diabetic cardiovascular complications (30) by preferentially switching the splicing of PKC-β isozymes to PKC-βII (24). Identical to insulin, in our study, CG-533353 prevented the HG-induced PKC-βII loss (Fig. 11F).

PKC-βII inhibitors may also bind with reversed orientation to different conformations of PKA (5). Alternatively, CG-53353 could block the EGF receptor (EGFR). It is marketed by EMD Chemicals as a PKC-βII/EGFR inhibitor (IC50 = 0.7 and 0.41 μM, respectively). However, the EGFR in VSMCs was dephosphorylated in the presence of HG (data not shown).

Furthermore, deletion of PKC-β isoforms in vivo reduces renal hypertrophy but not albuminuria in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse model (19), whereas LY-333531 treatment slows glomerulosclerosis development and decreases urinary protein excretion (13). Similar to LY-333531, ANG(1-7) or the ANG(1-7) analog AVE-0991 reduced proteinurea and the progression of diabetic kidney injury (2).

Conclusions

HG/glycotoxin influx downregulate ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) formation in rat VSMCs. The following is the proposed sequence of a biochemical pathway leading to this effect of HG: initially, glycotoxins (through conventional PKC) upregulate Nox1-based NADPH oxidase. Nox1-derived superoxides mediate PKC-β mRNA downregulation and PKC-βII protein loss. ACE2 mRNA expression is PKC-βII dependent, and the PKC-βII protein loss would subsequently result in the lowering of ACE2 expression and ANG(1-7) formation (Fig. 13).

Further studies using molecular tools such as siRNA are required to establish the PKC isoform(s) that is(are) involved in HG-induced Nox1 upregulation. Moreover, the role of PKC-βII in the development of diabetic cardiovascular complications and the precise target of PKC-βII inhibitors to ameliorate these complications remain to be established. Finally, a better understanding of the mechanisms regulating ACE2 expression in VSMCs and of tissue ANG(1-7) formation during hyperglycemia should allow the development of novel pharmacological strategies to prevent/treat diabetic cardiovascular complications.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-079109-04.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne M. Estes for the isolation and preparation of cultured VSMCs, Dr. Fariborz Yaghini for technical comments, Dr. George A. Cook for the kind help with real-time quantitative PCR, and Dr. David L. Armbruster for helpful editorial comments.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiello LP, Clermont A, Arora V, Davis MD, Sheetz MJ, Bursell SE. Inhibition of PKC beta by oral administration of ruboxistaurin is well tolerated and ameliorates diabetes-induced retinal hemodynamic abnormalities in patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 86–92, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benter IF, Yousif MH, Cojocel C, Al-Maghrebi M, Diz DI. Angiotensin-(1–7) prevents diabetes-induced cardiovascular dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H666–H672, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cappiello M, Amodeo P, Mendez BL, Scaloni A, Vilardo PG, Cecconi I, Dal Monte M, Banditelli S, Talamo F, Micheli V, Giblin FJ, Corso AD, Mura U. Modulation of aldose reductase activity through S-thiolation by physiological thiols. Chem Biol Interact 130–132: 597–608, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clempus RE, Sorescu D, Dikalova AE, Pounkova L, Jo P, Sorescu GP, Schmidt HH, Lassegue B, Griendling KK. Nox4 is required for maintenance of the differentiated vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 42–48, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gassel M, Breitenlechner CB, Konig N, Huber R, Engh RA, Bossemeyer D. The protein kinase C inhibitor bisindolyl maleimide 2 binds with reversed orientations to different conformations of protein kinase A. J Biol Chem 279: 23679–23690, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldin A, Beckman JA, Schmidt AM, Creager MA. Advanced glycation end products: sparking the development of diabetic vascular injury. Circulation 114: 597–605, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griendling KK, Sorescu D, Lassegue B, Ushio-Fukai M. Modulation of protein kinase activity and gene expression by reactive oxygen species and their role in vascular physiology and pathophysiology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 2175–2183, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamming I, Cooper ME, Haagmans BL, Hooper NM, Korstanje R, Osterhaus AD, Timens W, Turner AJ, Navis G, van Goor H. The emerging role of ACE2 in physiology and disease. J Pathol 212: 1–11, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilenski LL, Clempus Quinn MT RE, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Distinct subcellular localizations of Nox1 and Nox4 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 6776–6783, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Idris I, Donnelly R. Protein kinase C beta inhibition: a novel therapeutic strategy for diabetic microangiopathy. Diab Vasc Dis Res 3: 172–178, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoguchi T, Battan R, Handler E, Sportsman JR, Heath W, King GL. Preferential elevation of protein kinase C isoform beta II and diacylglycerol levels in the aorta and heart of diabetic rats: differential reversibility to glycemic control by islet cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 189: 11059–11063, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyer SN, Ferrario CM, Chappell MC. Angiotensin-(1–7) contributes to the antihypertensive effects of blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension 31: 356–361, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly DJ, Buck D, Cox AJ, Zhang Y, Gilbert RE. Effects on protein kinase C-β inhibition on glomerular vascular endothelial growth factor expression and endothelial cells in advanced experimental diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F565–F574, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komander D, Kular GS, Schuttelkopf AW, Deak M, Prakash KR, Bain J, Elliott M, Garrido-Franco M, Kozikowski AP, Alessi DR, van Aalten DM. Interactions of LY333531 and other bisindolyl maleimide inhibitors with PDK1. Structure 12: 215–226, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwan J, Wang H, Munk S, Xia L, Goldberg HJ, Whiteside CI. In high glucose protein kinase C-zeta activation is required for mesangial cell generation of reactive oxygen species. Kidney Int 68: 2526–2541, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert DW, Yarski M, Warner FJ, Thornhill P, Parkin ET, Smith AI, Hooper NM, Turner AJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha convertase (ADAM17) mediates regulated ectodomain shedding of the severe-acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2). J Biol Chem 280: 30113–30119, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lassègue B, Sorescu D, Szöcs K, Yin Q, Akers M, Zhang Y, Grant SL, Lambeth JD, Griendling KK. Novel gp91(phox) homologues in vascular smooth muscle cells: nox1 mediates angiotensin II-induced superoxide formation and redox-sensitive signaling pathways. Circ Res 88: 888–894, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavrentyev EN, Estes AM, Malik KU. Mechanism of high glucose induced angiotensin II production in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 101: 455–464, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meier M, Park JK, Overheu D, Kirsch T, Lindschau C, Gueler F, Leitges M, Menne J, Haller H. Deletion of protein kinase C-beta isoform in vivo reduces renal hypertrophy but not albuminuria in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse model. Diabetes 56: 346–354, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohazzab KM, Wolin MS. Sites of superoxide anion production detected by lucigenin in calf pulmonary artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 267: L815–L822, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Namiki M Chemistry of Maillard reactions: recent studies on the browning reaction mechanism and the development of antioxidants and mutagens. Adv Food Res 32: 115–184, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Obrosova IG Increased sorbitol pathway activity generates oxidative stress in tissue sites for diabetic complications. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 1543–1552, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel NA, Eichler DC, Chappell DS, Illingworth PA, Chalfant CE, Yamamoto M, Dean NM, Wyatt JR, Mebert K, Watson JE, Cooper DR. The protein kinase C beta II exon confers mRNA instability in the presence of high glucose concentrations. J Biol Chem 278: 1149–1157, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel NA, Apostolatos HS, Mebert K, Chalfant CE, Watson JE, Pillay TS, Sparks J, Cooper DR. Insulin regulates protein kinase CbetaII alternative splicing in multiple target tissues: development of a hormonally responsive heterologous minigene. Mol Endocrinol 18: 899–911, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice GI, Thomas DA, Grant PJ, Turner AJ, Hooper NM. Evaluation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), its homologue ACE2 and neprilysin in angiotensin peptide metabolism. Biochem J 383: 45–51, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.San Martin A, Foncea R, Laurindo FR, Ebensperger R, Griendling KK, Leighton F. Nox1-based NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide is required for VSMC activation by advanced glycation end-products. Free Radic Biol Med 242: 1671–1679, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt AM, Hori O, Brett J, Yan SD, Wautier JL, Stern D. Cellular receptors for advanced glycation end products: implications for induction of oxidant stress and cellular dysfunction in the pathogenesis of vascular lesions. Arterioscler Thromb 14: 1521–1528, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serrander L, Cartier L, Bedard K, Banfi B, Lardy B, Plastre O, Sienkiewicz A, Forro L, Schlegel W, Krause KH. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J 406: 105–114, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw S, Wang X, Redd H, Alexander GD, Isales CM, Marrero MB. High glucose augments the angiotensin II-induced activation of JAK2 in vascular smooth muscle cells via the polyol pathway. J Biol Chem 278: 30634–30641, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiba T, Inoguchi T, Sportsman JR, Heath W, Bursell S, King GL. Correlation of diacylglycerol and protein kinase C activity in rat retinal to retinal circulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 265: E783–E793, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The PKC-DRS Study Group. The effect of ruboxistaurin on visual loss in patients with moderately severe to very severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: initial results of the Protein Kinase C beta inhibitor Diabetic Retinopathy Study (PKC-DRS) multicentre randomized clinical trial. Diabetes 54: 2188–2197, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tikellis C, Johnston CI, Forbes JM, Burns WC, Burrell LM, Risvanis J, Cooper ME. Characterization of renal angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in diabetic nephropathy. Hypertension 41: 392–397, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tipnis SR, Hooper NM, Hyde R, Karran E, Christie G, Turner AJ. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem 275: 33238–33243, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tojo A, Asaba K, Onozato ML. Suppressing renal NADPH oxidase to treat diabetic nephropathy. Expert Opin Ther Targets 11: 1011–1018, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trask AJ, Ferrario CM. Angiotensin-(1–7): pharmacology and new perspectives in cardiovascular treatments. Cardiovasc Drug Rev 25: 162–174, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vickers C, Hales P, Kaushik V, Dick L, Gavin J, Tang J, Godbout K, Parsons T, Baronas E, Hsieh F, Acton S, Patane M, Nichols A, Tummino P. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem 277: 14838–14843, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei Y, Whaley-Connell AT, Chen K, Habibi J, Uptergrove GM, Clark SE, Stump CS, Ferrario CM, Sowers JR. NADPH oxidase contributes to vascular inflammation, insulin resistance, and remodeling in the transgenic (mRen2) rat. Hypertension 50: 384–391, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong DW, Oudit GY, Reich H, Kassiri Z, Zhou J, Liu QC, Backx PH, Penninger JM, Herzenberg AM, Scholey JW. Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (Ace2) accelerates diabetic kidney injury. Am J Pathol 71: 438–451, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia L, Wang H, Munk S, Frecker H, Goldberg HJ, Fantus IG, Whiteside CI. Reactive oxygen species, PKC-β1, and PKC-ζ mediate high glucose-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1280–E1288, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto M, Acevedo-Duncan M, Chalfant CE, Patel NA, Watson JE, Cooper DR. The roles of protein kinase C beta I and beta II in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Exp Cell Res 240: 349–358, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Naka Y, Schmidt AM. Glycation, inflammation, and RAGE: a scaffold for the macrovascular complications of diabetes and beyond. Circ Res 93: 1159–1169, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang L, Ma J, Gu Y, Lin S. Effects of blocking the renin-angiotensin system on expression and translocation of protein kinase C isoforms in the kidney of diabetic rats. Nephron Exp Nephrol 104: e103–e111, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]