Abstract

The renal handling and intestinal absorption of dietary oxalate are believed to be risk factors for calcium oxalate stone formation. In this study, we have examined the time and dose effects of soluble oxalate loads on the intestinal absorption and renal handling of oxalate in six stone formers (SF) and six normal individuals (N) who consumed diets controlled in oxalate and other nutrients. Urinary and plasma oxalate changes were monitored over 24 h after ingestion of 0, 2, 4, and 8 mmole oxalate loads, containing a mixture of 12C- and 13C2-oxalate. There were significant time and dose dependent changes in urinary oxalate excretion and secretion after these loads. However, there were no significant differences between SF and N in both the intestinal absorption and the renal handling of oxalate loads, as measured by the urinary excretion of oxalate (P = 0.96) and the ratio of oxalate to creatinine clearance (P = 0.34). 13C2-oxalate absorption studies showed three of the subjects, two SF and one N, had enhanced absorption with the 8 mmole load. A clear difference in absorption was demonstrated in these individuals during the 8–24 h interval, suggesting that in these individuals there was greater oxalate absorption in the large intestine as compared to the other subjects. This enhanced absorption of oxalate warrants further characterization.

Keywords: Urolithiasis, Renal secretion, Dietary oxalate

Introduction

Calcium oxalate stone disease is a multi-factorial process resulting from an interplay of environmental and genetic factors [1]. Evidence from our laboratory indicates that approximately half of urinary oxalate is derived from the diet, a key environmental factor [2]. While the concentration of oxalate in urine will affect its super-saturation with calcium oxalate and thus stone growth, it is not clear what role the amount of oxalate ingested, the amount of oxalate absorbed, or the renal handling of oxalate play in stone formation.

We recently reported that normal individuals secrete oxalate transiently when administered soluble oxalate loads [3]. With a load containing an amount of oxalate equivalent to a serving of spinach, these individuals secreted as much oxalate as was filtered. In addition, there were no signs of oxidative stress or renal injury associated with these transient oxalate loads. In this study, we examined whether stone formers respond differently than normal individuals to such oxalate loads and have monitored intestinal absorption over time by including isotopic oxalate with the loads. We have extended the urinary collection from 6 h post-load to 24 h post-load to assess for a delayed response in the parameters measured.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Twelve healthy, non-tobacco using adults without a history of any medical disorder that could influence the absorption or excretion of oxalate participated in this study. This included six subjects (three males and three females; mean age 32 ± 4 years; age range, 28–37 years) with no history of nephrolithiasis and six individuals (three males and three females; mean age 36 ± 5 years; age range, 31–44 years) who had at least 1 stone wit the previous 12 months that on analysis contained >50% calcium oxalate. Five of the six stone formers had recurrent disease with 4–12 stones formed. Five of six normals and five of six stone formers were tested for colonization with Oxalobacter formigenes by a PCR test and all were negative. Subjects provided informed consent before participating in this study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board. All subjects had a BMI < 27. They all refrained from vigorous exercise during the course of this study.

Protocol

Subjects collected four 24 h urine specimens on self-selected diets before beginning the controlled diet. Subjects consumed for 17 days a diet controlled in its content of calories, fat, protein, carbohydrate, calcium, magnesium, sodium, phosphorus, and oxalate as previously described [3]. Diets were prepared in the metabolic kitchen of the institutional General Clinical Research Center. The calcium content was targeted at 1,000 mg/2,500 kcal and the oxalate content 150 mg/2,500 kcal. This oxalate content is within the reported range of normal oxalate intake [4]. Diets were adjusted to within 5% of these amounts, and with a ratio of calcium to oxalate in each meal >5:1. The oxalate content of all food ingested was measured by capillary electrophoresis [4]. Figure 1 outlines the protocol followed by all subjects for each oxalate load. On day 8 of the diet, subjects fasted overnight (14 h) and then voided.

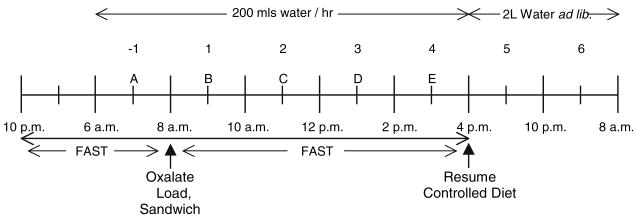

Fig. 1.

Dietary protocol followed by each subject the night before and after ingestion of an oxalate load. Urine collections are indicated by numerical numbers; “−1” refers to the fast collection. Each blood draw is indicated by an alphabetic letter. Oxalate load was taken with a turkey sandwich. Dietary protocol is described in detail in Materials and methods

They subsequently drank 400 ml of water and obtained a 2 h fasting urine collection. A blood sample was obtained at the midpoint of this collection. Subjects then ingested a sandwich consisting of two slices of white bread, 60 g of turkey, and 10 g of margarine. This meal contained 60 mg of calcium and 18 mg of oxalate. At the midpoint of this meal, subjects consumed one of four randomly assigned oxalate loads dissolved in 100 ml of water (0 mmole, 2 mmole, which contained 10% 13C2-oxalate, 4 mmole, which contained 10% 13C2-oxalate, and 8 mmole, which contained 5% 13C2-oxalate) adjusted to 70 kg body weight. Sodium oxalate from J.T. Baker Chemical Co, Phillipsburg, NJ was used to prepare 12C2- oxalic acid, and 13C2- oxalic acid was obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc, Andover, MA, USA. The utilization of 13C2-oxalate permitted an assessment of gastrointestinal oxalate absorption. Four sequential 2 h urine collections were then obtained together with a blood sample at the midpoint of each collection. They consumed 200 ml of distilled water per hour over the 8 h period following the loads during which they fasted from food. After this 8 h period they resumed their controlled diet, drank 2 liters of water ad libitum, and collected two other urine samples: 8–14 h post load and 14–24 h post load. Similar load studies were conducted on days 11, 14 and 17. The subjects were also maintained on the metabolic diet on the days between these loads.

Assays

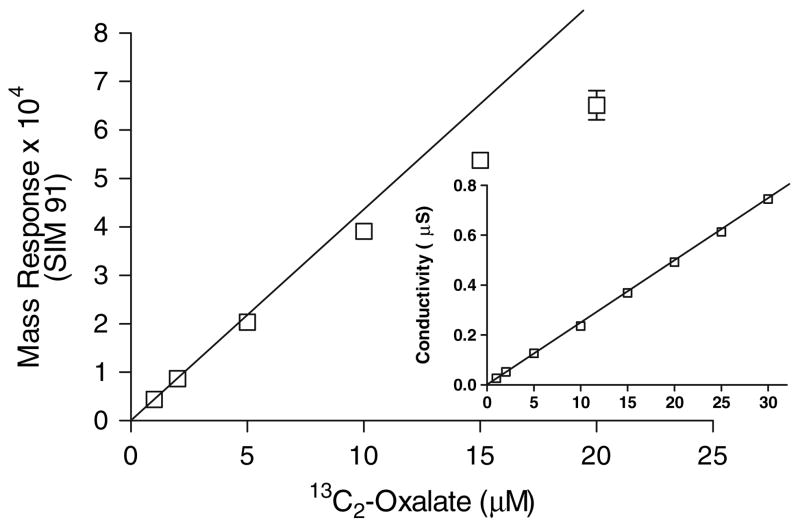

Total urine oxalate and plasma oxalate were determined by ion chromatography, as previously described [5]. Urine 13C2-oxalate was determined by ion chromatography coupled with electrospray mass spectrometry (IC-MS) [Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA]. The IC portion of IC-MS used a 2 mm i.d. IonPac AS11-HC column and sodium hydroxide as the mobile phase. The limit of detection, defined as the mean blank signal plus ten times the standard deviation of the blank, for 13C2-oxalate by conductivity and mass detection was 1 pmole (0.1 μM) and 0.4 pmole (0.04 μM), respectively. The mass and conductivity response at varying concentrations of 13C2-oxalate is shown in Fig. 2. As shown in Fig. 2, a limitation of mass detection by IC-MS was a loss of linear mass response above oxalate concentrations of 4 μM. Thus, accurate mass quantification of 13C2-oxalate was achieved by diluting each urine appropriately to ensure the total oxalate level was below 4 μM. The low limit of detection achieved with mass detection (0.04 μM) allowed urines to be diluted extensively and still give accurate determinations of 13C2-oxalate. The intra-sample assay and inter-sample assay variability (n = 6) for mass detection of 13C2-oxalate was 5.1 and 5.9% (SD/mean), respectively. The mean recovery of 50 μM added 13 C2-oxalate to four different urines from subjects who had ingested different 13 C2-oxalate loads was 101 ± 9%, range 93–109%. 12C- and 13C2-oxalate was measured in each urine sample. 13C2-oxalate determinations were corrected for the natural abundance of the 13C2 and 18O isotopes (0.8%).

Fig. 2.

Mass and conductivity (inset) response at varying concentrations of 13C2-oxalate by IC-MS. SIM 91 refers to the molecular weight of 13C2-oxalate minus 1. Mass response departs from linearity after 4 μM, whereas conductivity detection is linear past 30 μM. The results are the mean ± SD of triplicate injections

Calcium, magnesium, phosphate, uric acid, citrate, and urea were measured in urine samples as previously described [6]. These measurements provided a means of assessing subject compliance with the dietary protocol, and allowed calcium oxalate crystallization indices to be calculated for the 8 mmole load as described by Tiselius [7]. Creatinine was measured in all urine samples as previously described [6]. Urinary isoprostanes were measured by LC/MS/MS, as described by Li et al. [8]. The urinary excretion of N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (NAG) and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) was measured as previously described [9] except that urinary inhibitors of enzyme activity were removed by centrifugal filtration using Ultra-free-MC filters (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA) with a 10,000 nominal molecular weight limit.

Statistical analyses

Results are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified. The figures contain unadjusted means and SEM. The primary analysis used a mixed model analysis of variance approach using SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), as previously described [3]. A two-tailed t test was used to determine the significance of differences in urinary excretions on self-selected diets.

Results

The mean urinary excretions of the two groups when consuming self-selected diets are shown in Table 1. Urinary calcium excretion was significantly higher in the stone forming group, two subjects having hypercalciuria.

Table 1.

A comparison of the mean 24 h urinary excretions of the normal subjects (n = 6) and stone formers (n = 6) on self-selected diets. For each individual the mean ± SD of four collections was used for the comparisons

| Normals | Stone formers | Significance (P value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (ml) | 1,724 ± 466 | 1,919 ± 783 | NS |

| Oxalate (mg) | 24.8 ± 5.2 | 24.7 ± 7.6 | NS |

| Calcium (mg) | 89 ± 59 | 245 ± 91 | 0.02 |

| Citrate (mg) | 495 ± 133 | 360 ± 173 | NS |

NS not significant

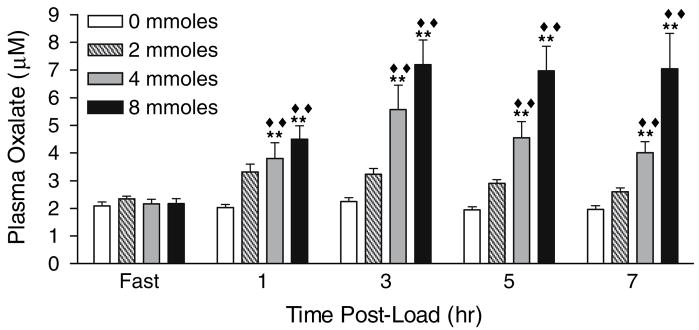

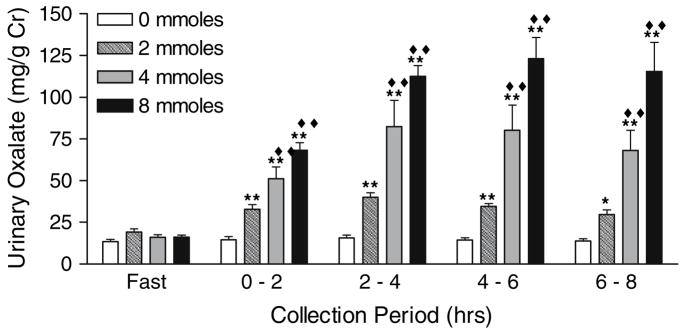

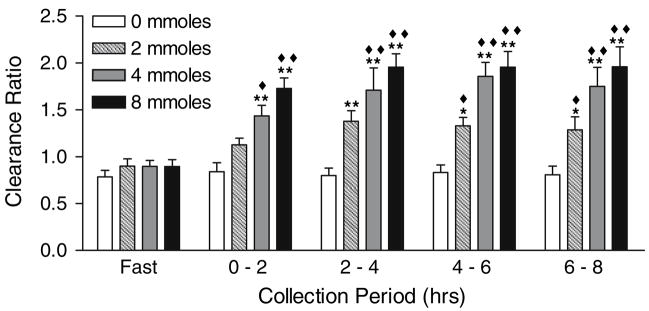

Table 2 illustrates that there were no differences between N and SF in their renal handling of oxalate, as measured by the urinary excretion of oxalate (P = 0.96) and the ratio of oxalate to creatinine clearance (P = 0.34). Within each group, significant changes were observed in plasma oxalate, urinary oxalate and the clearance ratio of oxalate to creatinine after each oxalate load, but not with the 0 mmole load. Because of the lack of a significant difference between N and SF, results of renal oxalate handling were pooled to enhance the detection of significant changes and these are shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5. Significant changes in urinary oxalate excretion and clearance ratios were observed following the 2, 4 and 8 mmole loads. Significant changes in plasma oxalate only occurred following the 4 and 8 mmole loads. Time and dose dependent increases were observed for all parameters, with a maximal response reached 2–4 h post-load. With the 8 mmole load, the level reached in the 2–4 h collection was maintained through the 6–8 h collection. Creatinine clearances and urinary volumes were similar throughout all study periods (data not shown).

Table 2.

Renal handling of soluble oxalate loads, as measured by the peak (2–4 h) urinary excretion of oxalate and ratio of oxalate to creatinine clearance in comparison to fasting values

| Oxalate load (mmoles) | Collection period (h) | Urinary oxalate (mg/g creatinine) |

Clearance ratio |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | SF | N | SF | ||

| 0 | Fast | 14.94 ± 4.08 | 12.44 ± 3.88 | 0.83 ± 0.30 | 0.76 ± 0.06 |

| 2–4 | 17.40 ± 6.43 | 13.54 ± 3.73 | 0.81 ± 0.22 | 0.79 ± 0.17 | |

| 2 | Fast | 19.96 ± 9.03 | 18.53 ± 2.91 | 0.87 ± 0.32 | 0.93 ± 0.10 |

| 2–4 | 34.6 ± 11.71 | 43.73 ± 4.61 | 1.22 ± 0.25 | 1.54 ± 0.19 | |

| 4 | Fast | 14.34 ± 2.94 | 17.26 ± 6.83 | 0.79 ± 0.17 | 1.00 ± 0.08 |

| 2–4 | 79.51 ± 43.39 | 85.46 ± 67.67 | 1.66 ± 0.92 | 1.76 ± 0.32 | |

| 8 | Fast | 17.17 ± 4.88 | 15.01 ± 4.09 | 0.81 ± 0.26 | 1.00 ± 0.10 |

| 2–4 | 103.88 ± 10.63 | 119.85 ± 26.60 | 1.90 ± 0.33 | 2.00 ± 0.24 | |

Results are expressed as mean values ± SD. N, six subjects with no history of nephrolithiasis. SF six stone formers who had passed at least 1 stone that on analysis contained >50% Ca Ox

Fig. 3.

Plasma oxalate concentrations following oxalate loads. Filled double diamonds denote P < 0.0001 for the comparison of load values at each time point with the 0 mmole load. Double asterisks denote P < 0.0001 for the comparison of load values with their corresponding fasting value. Data are a combination of results from six stone formers and six non-stone formers

Fig. 4.

Urinary oxalate excretion relative to that of creatinine following oxalate loads. Filled double diamonds denotes P < 0.0001 for the comparison of load values at each collection period with the 0 mmole load. Single asterisk denotes P < 0.01 for the comparison of load values with their corresponding fasting value, and double asterisks denotes P < 0.0001. Data are a combination of results from six stone formers and six non-stone formers

Fig. 5.

The ratio of oxalate clearance to creatinine clearance following oxalate loads. Filled diamond denotes P < 0.01 for the comparison of load values at each collection period with the 0 mmole load, and Filled diamonds denotes P < 0.0001. Single asterisk denotes P < 0.01 for the comparison of load values with their corresponding fasting value, and double asterisks denote P < 0.0001. Data are a combination of results from six stone formers and six non-stone formers

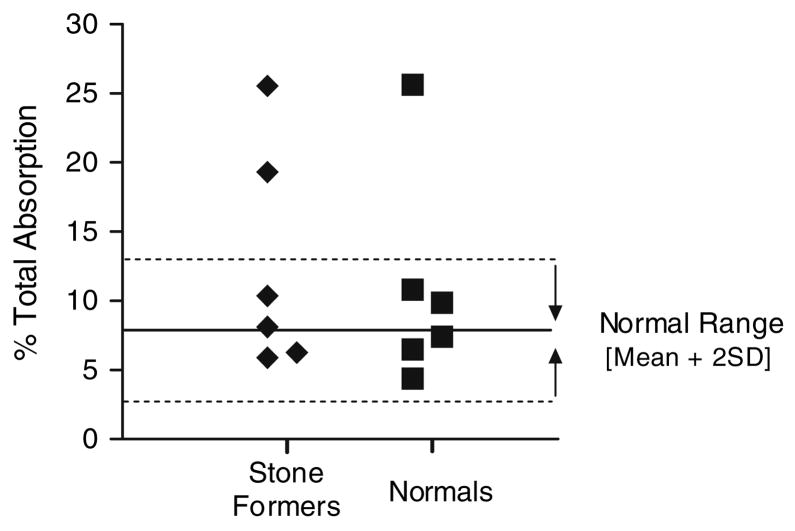

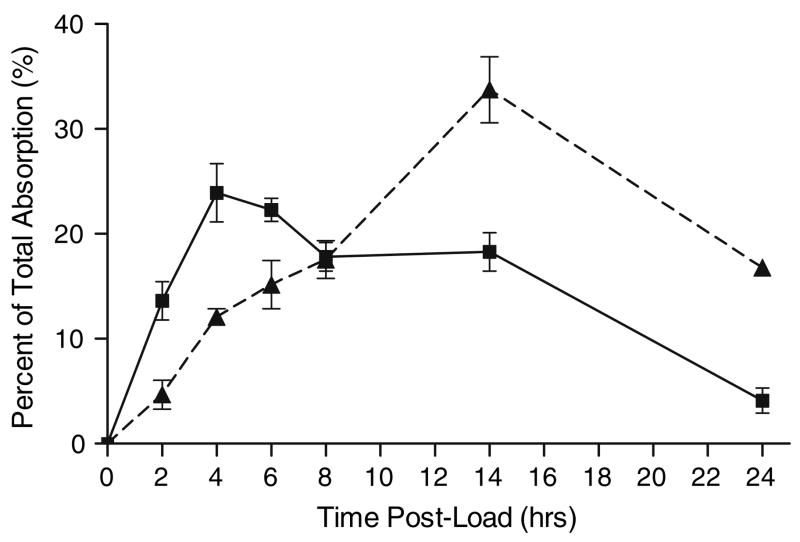

The 13C2-oxalate absorption studies demonstrated that the majority of SF and N had similar absorption patterns. Mean absorptions with 2, 4 and 8 mmole loads are shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference between SF and N (P = 0.86). A review of the individual 13C2-oxalate absorption data demonstrated that the absorption of three male subjects, 1 N and 2 SF, was 3 SD above the mean of the other nine individuals with the 8 mmole load (Fig. 6). Enhanced absorption was observed with the 4 mmole load in two of these three subjects, but none with the 2 mmole oxalate load suggesting a weak dose response effect. The time course of absorption on the 8 mmole load is depicted in Fig. 7 where the means of the nine individuals and the three with enhanced absorption are plotted. This demonstrates a clear difference during the 8–24 h interval suggesting greater oxalate absorption in the large intestine in the three with enhanced absorption. The mean 13C2-oxalate percent absorption during the 8–24 h interval in the three individuals with enhanced absorption and the remaining nine subjects was 11.2 ± 2.3 and 3.1 ± 1.3 %, respectively. Total urinary oxalate in this interval was also much higher in the three individuals, 142.8 ± 75.1 mg oxalate compared with 33.6 ± 13.9 mg in the other nine subjects. These three individuals had normal oxalate excretions on self-selected diets, however, 26.5 ± 4.1 mg, compared with 24.2 ± 6.9 mg in the other nine subjects.

Table 3.

Total absorption of 13C2-oxalate in 24 h after ingestion of varying loads of sodium oxalate

| Oxalate load (mmoles) |

13C2-oxalate absorption (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| N | SF | |

| 2 | 7.47 ± 1.52 | 8.37 ± 2.53 |

| 4 | 9.56 ± 4.32 | 10.08 ± 7.85 |

| 8 | 11.64 ± 8.41 | 12.03 ± 7.59 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. N, six subjects with no history of nephrolithiasis. SF, six stone formers who had passed at least 1 stone that on analysis contained >50% Ca Ox

Fig. 6.

Absorption of 13C2-oxalate 24 h after ingestion of an 8 mmole soluble oxalate load for six non-stone formers (filled square) and six stone formers (filled diamond)

Fig. 7.

Normalized pattern of 13C2-oxalate absorption over time after ingestion of an 8 mmole soluble oxalate load for a group of nine individuals with a normal pattern of oxalate absorption (filled square) compared to a group of three subjects who showed enhanced absorption (--filled triangle--)

Mean calcium oxalate crystallization indices, as described by Tiselius [7], calculated for the 8 mmole load were 0.55 ± 0.37 for the N group and 0.73 ± 0.55 for the SF group, demonstrating that the urine was under saturated with respect to calcium oxalate. This undersaturation was most likely related to the vigorous hydration subjects received. Urinary excretions from subjects receiving the 8 mmole oxalate load were examined for changes in the excretion of isoprostanes and the proximal tubule-derived enzymes, NAG and GGT. Changes in the excretion of these parameters were not evident after this load in either N or SF subjects (Table 4), or when comparing the three individuals who showed enhanced absorption with the other nine individuals (data not shown).

Table 4.

Excretion of markers of proximal tubular injury and oxidative stress following an 8 mmole oxalate load in normal subjects and stone formers. iPF2α -III, 5-epi-8, 12-iso-iPF2α VI, and 8,12-iso-iPF2α-VI are isoprostanes, non-enzymatic oxidation products of arachi-donic acid and indicators of oxidative stress

| Sample (h) | iPF2α-III (ng/mg Cr) | 5-epi-8,12-iso-iPF2α-VI (ng/mg Cr) | 8,12-iso-iPF2α-VI (ng/mg Cr) | NAG (U/g Cr) | GGT (U/g Cr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normals | |||||

| Fast | 2.73 ± 2.18 | 10.7 ± 6.9 | 8.1 ± 5.5 | 3.27 ± 0.75 | 3.95 ± 3.57 |

| 0–2 | 1.96 ± 0.75 | 12.8 ± 5.6 | 9.4 ± 6.0 | 4.41 ± 1.27 | 5.32 ± 3.11 |

| 2–4 | 3.41 ± 3.08 | 9.1 ± 6.7 | 11.7 ± 9.2 | 4.18 ± 1.49 | 4.48 ± 2.25 |

| 4–6 | 2.44 ± 2.03 | 11.4 ± 7.2 | 9.8 ± 5.8 | 3.90 ± 1.33 | 4.67 ± 2.73 |

| 6–8 | 1.56 ± 1.42 | 7.9 ± 6.1 | 10.2 ± 5.9 | 3.58 ± 1.71 | 5.07 ± 3.10 |

| 8–16 | 2.27 ± 1.39 | 12.6 ± 8.3 | 10.6 ± 7.4 | 4.35 ± 1.79 | 3.86 ± 2.35 |

| 16–24 | 2.63 ± 2.06 | 13.8 ± 9.5 | 9.3 ± 6.8 | 3.37 ± 1.27 | 4.42 ± 2.87 |

| Stone formers | |||||

| Fast | 3.41 ± 1.80 | 14.9 ± 8.0 | 12.1 ± 8.5 | 3.58 ± 1.02 | 3.13 ± 1.52 |

| 0–2 | 2.95 ± 1.88 | 14.3 ± 10.7 | 11.9 ± 6.1 | 4.03 ± 1.49 | 4.20 ± 1.43 |

| 2–4 | 2.71 ± 2.17 | 10.2 ± 6.1 | 10.2 ± 7.0 | 4.20 ± 2.46 | 4.17 ± 1.92 |

| 4–6 | 3.02 ± 1.46 | 13.8 ± 8.7 | 13.8 ± 9.6 | 3.77 ± 2.39 | 4.14 ± 1.93 |

| 6–8 | 1.86 ± 0.97 | 12.8 ± 8.3 | 11.0 ± 8.8 | 3.72 ± 2.24 | 3.17 ± 1.77 |

| 8–16 | 2.72 ± 1.49 | 11.0 ± 7.2 | 9.7 ± 6.5 | 4.41 ± 1.95 | 3.30 ± 1.80 |

| 16–24 | 1.45 ± 1.03 | 15.6 ± 9.2 | 11.6 ± 8.2 | 4.18 ± 2.25 | 4.72 ± 1.65 |

NAG and GGT are proximal tubule-derived enzymes and their increase in urine is an early sign of renal injury. Data are expressed as mean ± SD

Discussion

The intestinal absorption of dietary oxalate and its renal handling may influence calcium oxalate kidney stone formation. Renal filtration and secretion of oxalate could lead to calcium oxalate crystallization and crystal growth in the nephron or collecting system. Two studies have pointed to an altered renal handling of oxalate in stone formers. A study of renal oxalate handling in 11 normal individuals and 17 stone formers suggested that stone formers may have a net secretion of oxalate during a 24 h period whereas a slight reabsorption of oxalate may occur in normal individuals [10]. However, their calculations were not dynamic, based on a 24 hr urine collection and a single plasma oxalate measurement. Another study identified a similar pattern in a 2 h fasting urine and accompanying blood sample [11]. There was no dietary control in either of these studies. In our study, diet was controlled, and renal handling of oxalate was longitudinally assessed. Plasma oxalate, urinary oxalate excretion, and the clearance ratio all increased similarly with increasing doses of oxalate in both groups. The results are similar to our earlier study of normal subjects, but demonstrate the same response in stone forming subjects [3]. Renal oxalate secretion after a single oxalate load was evident in all collections up to 8 h. This implies that after an oxalate rich meal the kidney could be secreting oxalate for an extended period of time. While it would be interesting to assess longer time points of collection in order to accurately determine the half life of absorbed oral oxalate loads, this is not practical as it would be difficult for the patients to remain fasting. The use of an oxalate-free diet to circumvent the latter has limitations as there may be effects of food ingestion on endogenous oxalate synthesis.

We again found no differences in the urinary excretion of isoprostanes, NAG and GGT, after the highest oxalate load in normal subjects. In addition, this was also observed in stone formers. These results indicate that renal tubular injury and oxidative stress did not occur in this experimental setting. We believe that the proximal tubular cells were transiently exposed to high concentrations of oxalate, which were not significantly attenuated by the vigorous hydration. The influence of hydration would most likely impact the distal nephron. Potential injury to this part of the nephron was not addressed in this study. These results suggest that transient exposure of the kidney to high levels of oxalate may not be overtly harmful, but we can not rule out that more chronic exposures may produce the renal damage reported by others in model systems [12–14].

Several studies, but not all, have indicated that stone formers may absorb more oxalate than non-stone formers, as reviewed by Hesse et al. [15]. A limitation of many of these studies is that dietary oxalate and other nutrients were not controlled. Recently, Voss et al. [16] assessed the prevalence of oxalate hyperabsorption in 120 healthy volunteers and 120 recurrent calcium oxalate stone formers on controlled diets. They showed a significantly higher mean intestinal 13C2-oxalate absorption in the recurrent idiopathic calcium oxalate stone formers (10.2 ± 5.2%) compared with 120 healthy volunteers (8.0 ± 4.4%). A small number of individuals, only stone formers, absorbed greater than 20% of the oxalate load. Further study of this phenotype is warranted to determine the mechanisms of hyperabsorption. In the present study, the intestinal handling of oxalate appeared to be of two distinct types, normal and enhanced absorption. However, the small number of subjects precludes any conclusions about the influence of enhanced oxalate absorption on stone formation. Four of six SF and five of six N had similar responses to the 8 mmole oxalate load with a mean absorption of 7.7 ± 2.2%. The peak in oxalate absorption occurred 2–4 h after the oxalate load in these individuals, which is compatible with a significant amount of the absorption occurring in the small intestine. Three individuals showed enhanced absorption with the 8 mmole load, mean absorption of 23.5 ± 3.6%. The 8–24 h interval was discriminatory in these subjects, suggesting greater oxalate absorption in the large intestine. The results also suggest a dose dependent response. No subject in our study with enhanced oxalate absorption excreted more than 40 mg oxalate/day during the four 24 h urine specimens collected on self-selected diets. There are possible reasons for this including low endogenous oxalate synthesis, consumption of a low oxalate diet, an increased ratio of dietary divalent cations to oxalate limiting the absorption of oxalate, or that enhanced absorption is triggered by high doses of oxalate. All ten subjects tested for O. formigenes, including the three individuals who showed enhanced absorption, were found not to be colonized with this organism based on the PCR test utilized. This suggests enhanced absorption was not strongly linked with the absence of O. formigenes in our study. This colonization rate is low, but consistent with our recent observations in a much larger cohort from our geographic area (R. P. Holmes and H. Sidhu, unpublished observations).

Because of our primary interest in renal oxalate excretion in this study, we did not target patients with hyperoxaluria, but recognize that this group would be interesting to investigate in view of our results and those of others on intestinal oxalate absorption. This is supported by Krishnamurthy et al. [17] who reported that idiopathic calcium oxalate stone formers with hyperoxaluria had a more pronounced urinary oxalate excretion after a 5 mmole oral oxalate load than patients with normal oxalate excretion.

The sample size in each group of our study was limited to six individuals. We recognize that such a group size can only provide preliminary results on any potential differences between SF and N and only allow major differences in renal and intestinal handling to be possibly observed. To detect minor differences between N and SF a much larger sample size (50–100) would be required to have sufficient power to identify aberrations in 5–10% of the idiopathic calcium oxalate stone forming population, and the study protocol significantly modified to facilitate recruitment and lower costs.

In summary, this study demonstrates similar time and dose dependent responses in plasma oxalate, oxalate excretion and secretion in N and SF cohorts administered soluble oral oxalate loads. There was no evidence of proximal tubular injury or oxidative stress after the most robust oxalate load. A minority of individuals demonstrated enhanced oxalate absorption, which was most apparent after the 8 mmole load. These individuals may have secreted oxalate for an extended period of time following the 8 mmole load, yet no increase in injury markers was evident. Our study suggests that discrimination between normal absorbers and those with enhanced absorption may be due to events in the large colon. Therefore, factors influencing such a response will be important to characterize.

Acknowledgments

The skilful assistance of Mike Samuel in the Biochemistry Mass Spectrometry Facility with the analysis of isoprostanes was greatly appreciated. The assistance by Cralen Davis in the Department of Public Health Sciences is gratefully acknowledged. The authors gratefully acknowledge Martha Kennedy and Persida Tahiri for technical assistance.

This research was supported in part by NIH grants RO1 DK62284 and MO1 RR07122.

Abbreviations

- SF

Stone formers

- N

Normal individuals

- NAG

N-Acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (NAG)

- GGT

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase

Contributor Information

John Knight, Department of Urology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA, e-mail: jknight@wfubmc.edu.

Ross P. Holmes, Department of Urology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA

Dean G. Assimos, Department of Urology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Medical Center Blvd, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA

References

- 1.Goodman HO, Holmes RP, Assimos DG. Genetic factors in calcium oxalate stone disease. J Urol. 1995;153:301. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holmes RP, Goodman HO, Assimos DG. Contribution of dietary oxalate to urinary oxalate excretion. Kid Int. 2001;59:270. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes RP, Ambrosius WT, Assimos DG. Dietary oxalate loads and renal oxalate handling. J Urol. 2005;174:943. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169476.85935.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes RP, Kennedy M. Estimation of the oxalate content of foods and daily oxalate intake. Kid Int. 2000;57:1662. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagen L, Walker VR, Sutton RA. Plasma and urinary oxalate and glycolate in healthy subjects. Clin Chem. 1993;39:134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes RP, Goodman HO, Hart LJ, Assimos DG. Relationship of protein intake to urinary oxalate and glycolate excretion. Kid Int. 1993;44:366. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiselius HG. Aspects on estimation of the risk of calcium oxalate crystallization in urine. Urol Int. 1991;47:255. doi: 10.1159/000282232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H, Lawson JA, Reilly M, Adiyaman M, Hwang S-W, Rokach J, Fitzgerald GA. Quantitative high performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometric analysis of the four classes of F2-isoprostanes in human urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assimos DG, Boyce WH, Furr EG, Espeland MA, Holmes RP, Harrison LH, Kroovand RL, McCullough DL. Selective elevation of urinary enzyme levels after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. J Urol. 1989;142:687. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson DM, Liedtke RR, Smith LH. Oxalate clearances in calcium oxalate stone forming patients. In: Ryall R, Bais R, Marshall VR, Rofe AM, Smith LH, Walker VR, editors. Urolithiasis II. Plenum Press; New York: 1994. p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwille PO, Manoharan M, Rumenapf G, Wolfel G, Berens H. Oxalate measurement in the picomol range by ion chromatography: values in fasting plasma and urine of controls and patients with idiopathic calcium urolithiasis. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1989;27:87. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1989.27.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green MJ, Freel RW, Hatch M. Lipid peroxidation is not the underlying cause of renal injury in hyperoxaluric rats. Kid Intl. 2005;68:2629. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonassen JA, Cao LC, Honeyman T, Scheid CR. Mechanisms mediating oxalate-induced alterations in renal cell functions. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2003;13:55. doi: 10.1615/critreveukaryotgeneexpr.v13.i1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan SR. Renal tubular damage/dysfunction: key to the formation of kidney stones. Urol Res. 2006;34:86. doi: 10.1007/s00240-005-0016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hesse A, Schneeberger W, Engfeld S, Unruh GEV, Sauerbruch T. Intestinal hyperabsorption of oxalate in calcium oxalate stone formers: application of a new test with [13C2]oxalate. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:S329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voss S, Hesse A, Zimmermann DJ, Sauerbruch T, von Unruh GE. Intestinal Oxalate absorption is higher in idiopathic calcium oxalate stone formers than in healthy controls: measurements with the [13C2]Oxalate absorption test. J Urol. 2006;175:1711. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)01001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnamurthy M, Hruska KA, Chandhoke PS. The urinary response to an oral oxalate load in recurrent calcium stone formers. J Urol. 2003;169:2030. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000062527.37579.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]