Abstract

Background

The relationship between mental and physical disorders is well established, but there is less consensus as to the nature of their joint association with disability, in part because additive and interactive models of co-morbidity have not always been clearly differentiated in prior research.

Method

Eighteen general population surveys were carried out among adults as part of the World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative (n=42 697). DSM-IV disorders were assessed using face-to-face interviews with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI 3.0). Chronic physical conditions (arthritis, heart disease, respiratory disease, chronic back/neck pain, chronic headache, and diabetes) were ascertained using a standard checklist. Severe disability was defined as on or above the 90th percentile of the WMH version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS-II).

Results

The odds of severe disability among those with both mental disorder and each of the physical conditions (with the exception of heart disease) were significantly greater than the sum of the odds of the single conditions. The evidence for synergy was model dependent: it was observed in the additive interaction models but not in models assessing multiplicative interactions. Mental disorders were more likely to be associated with severe disability than were the chronic physical conditions.

Conclusions

This first cross-national study of the joint effect of mental and physical conditions on the probability of severe disability finds that co-morbidity exerts modest synergistic effects. Clinicians need to accord both mental and physical conditions equal priority, in order for co-morbidity to be adequately managed and disability reduced.

Keywords: Co-morbidity, disability, interaction, mental, physical

Introduction

Disability, encompassing impairments, activity limitations and/or participation restrictions (WHO, 2001), is an important consequence of both physical and mental disorders. Those studies that have assessed the relative level of disability associated with physical and mental conditions have found mental disorders to be at least as disabling as common chronic physical conditions (Wells et al. 1989b; Hays et al. 1995; Armenian et al. 1998; Ormel et al. 1998; Moussavi et al. 2007; Ormel et al. in press). However, mental and physical disorders are known to co-occur at greater than chance levels (Wells et al. 1989a; Dew, 1998; Buist-Bouwman et al. 2005; Scott et al. 2006b, 2007). This begs the question as to the nature of their joint impact on disability.

A useful distinction has been drawn by Schettini Evans & Frank (2004) between additive and interactive models of co-morbidity. An additive model suggests that the individual components of co-morbid disorders have independent effects on functioning, which occur together in linear combination (that is, the combined effect is approximately equal to the sum of the parts). An interactive model suggests that co-morbidity is associated with significantly greater (or lower) levels of dysfunction than predicted by a simple sum of the disabling effects of the individual disorders. The implication of the interactive model is that the presence of one disorder alters the association of the other disorder with disability.

The investigation of this topic has not been extensive thus far and has produced divergent results. Some studies have researched the joint effects of mental and physical disorder on disability and found them to be greater than the effects of either condition alone but have not been conclusive about whether the nature of the joint effect is additive or synergistic (Druss et al. 2000; Sareen et al. 2006; Moussavi et al. 2007). Other research that has distinguished between additive and synergistic models has concluded that mental and physical conditions have mostly additive effects on disability (Wells et al. 1989b; Ormel et al. 1998; Buist-Bouwman et al. 2005), although a few studies have found synergistic effects (Kessler et al. 2001, 2003; Egede, 2004; Schmitz et al. 2007). By contrast, Merikangas et al. (2007) recently observed a number of significant interactions between mental and physical conditions in predicting days out of role that were nearly all negative.

A contributor to the divergent findings is the fact that researchers have used either linear regression (which uses an additive scale) or logistic regression (which uses a multiplicative scale) to assess interaction effects. The underlying model of how mental and physical disorders might combine is an additive one (Ahlbom & Alfredsson, 2005), and the interaction of risk factors should therefore be assessed as a departure from additivity not multiplicativity (Ahlbom & Alfredsson, 2005; Andersson et al. 2005). The use of logistic regression is more likely to result in no interactions or negative interactions relative to using linear regression, unless the logistic regression is adapted to produce output needed for assessment of the interaction on an additive scale (Ahlbom & Alfredsson, 2005; Andersson et al. 2005; Schmitz et al. 2007).

The World Mental Health (WHM) Survey Initiative (Kessler & Ustun, 2004) is a consortium of general population surveys carried out in developing and developed countries. The surveys used standardized diagnostic assessment of mental disorders and also collected information on chronic physical disease prevalence and functional disability. This provides the opportunity to address this research question on a cross-national basis. In this paper we compare four groups in terms of their association with disability: those with mental disorder in the absence of a given physical disorder, those with the physical disorder in the absence of mental disorder, those with both, and those with neither. Six common physical conditions were investigated: arthritis, heart disease, respiratory disease, chronic back and neck pain, chronic headache, and diabetes. The mental disorders investigated included those in the depressive-anxiety spectrum. The objective was to ascertain whether the joint effect of mental and physical conditions on the probability of severe disability is significantly greater than, or approximately equal to, the sum of the individual effects.

Method

Samples

Eighteen surveys were carried out in 17 countries in the Americas (Colombia, Mexico, the USA), Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain, Ukraine), the Middle East (Israel, Lebanon), Africa (Nigeria, South Africa), Asia (Japan, separate surveys in Beijing and Shanghai in the People’s Republic of China) and the South Pacific (New Zealand). All surveys were based on multi-stage, clustered, area probability household samples. All interviews were carried out face-to-face by trained lay interviewers. Sample sizes range from 2372 (The Netherlands) to 12992 (New Zealand) with a total of 85 088 respondents. Response rates range from 45.9% (France) to 87.7% (Colombia), with a weighted average response rate of 70.8%.

Internal subsampling was used to reduce respondent burden by dividing the interview into two parts. Part 1 included the core diagnostic assessment of mental disorders. Part 2 included additional information relevant to a wide range of survey aims, including assessment of chronic physical conditions. All respondents completed Part 1. All Part 1 respondents who met criteria for any mental disorder and a probability sample of other respondents also completed Part 2. Part 2 respondents were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection for Part 2 of the interview to adjust for differential sampling. Analyses in this article were based on the weighted Part 2 subsample (n=42 697). Additional weights were used to adjust for differential probabilities of selection within households, adjust for non-response and to match the samples to population socio-demographic distributions.

Training and field procedures

The central WMH staff trained bilingual supervisors in each country. The World Health Organization (WHO) translation protocol was used to translate instruments and training materials. Some surveys were carried out in bilingual (Belgium) or multilingual form (Ukraine, Israel, Nigeria). Other surveys were carried out exclusively in the country’s offcial language. Persons who could not speak these languages were excluded. Quality control protocols, described in more detail elsewhere (Kessler et al. 2004), were standardized across countries to check on interviewer accuracy and to specify data cleaning and coding procedures. The institutional review board of the organization that coordinated the survey in each country approved and monitored compliance with procedures for obtaining informed consent and protecting human subjects.

Mental disorder status

All surveys used the WMH Survey version of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI, now CIDI 3.0; Kessler & Ustun, 2004), a fully structured diagnostic interview, to assess disorders and treatment. Disorders were assessed using the definitions and criteria of DSM-IV (APA, 1994). CIDI organic exclusion rules were imposed (the diagnosis was not made if the respondent indicated that their episodes of depressive symptoms were always due to physical illness or injury or use of medication, drugs or alcohol). This paper includes 12-month anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and social phobia) and depressive disorders (dysthymia and major depressive disorder). Anxiety and depressive disorders were aggregated into a single category, on the basis of prior findings from the WMH surveys that anxiety disorders and depressive disorders have equal and independent relationships with a wide range of chronic physical conditions (Scott et al. 2007). This approach keeps manageable the number of analyses that need to be carried out to answer the research question in a cross-national framework.

Chronic physical conditions

Physical conditions were assessed with a standard chronic disorder checklist (NCHS, 1994). Prior research has demonstrated reasonable correspondence between self-reported chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease and asthma, and general practitioner records (Kriegsman et al. 1996).

For the chronic pain conditions reported here (back or neck pain, headaches), respondents were asked if they had ever had chronic back or neck problems or frequent or severe headaches, and additionally, whether they had experienced these symptoms in the past 12 months (for Nigeria, Lebanon, China and Ukraine respondents were only asked if they had experienced these pain problems in the past 12 months). For the other conditions, respondents were asked if they had ever been told by a doctor that they had heart disease, asthma or other respiratory disease, or diabetes. The question about arthritis was asked in two different ways, depending on country. In Nigeria, Lebanon, China and Ukraine, respondents were asked if they had experienced arthritis or rheumatism in the past 12 months. The remaining surveys asked about arthritis in the same format as for heart disease, respiratory disease and diabetes. For those conditions where both lifetime or 12-month prevalences were available (the chronic pain conditions), the 12-month prevalence was used in these analyses on the assumption that it would be more closely associated with the current disability measure.

Disability

This was assessed with the WMH Survey version of the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS-II), referred to here as the WMH WHODAS. This instrument assesses disability in several domains: role impairment, mobility, self-care, social functioning and cognitive functioning. It was administered as a generic section to all participants in the Part 2 subsample, asking about disability in the past 30 days attributable to health, emotional or mental health problems. More detail on the WMH WHODAS is provided elsewhere (Scott et al. 2006a; Von Korff et al. in press). As well as domain scores, a global score can be calculated as an aggregation of domain scores; the global score is used in this paper, given the large number of surveys included. The global score does to some extent obscure domain-specific differences in the disability associated with mental and physical conditions; these can be observed in a separate report on the New Zealand survey (Scott et al. 2006a).

Higher global scores (on a 0–100 scale) indicate greater disability. Disability was dichotomized for the current analyses; it was calculated on a country-specific basis and defined as a score on or above the 90th percentile of the WMH WHODAS distribution in each country (i.e. capturing the most disabled 10% of the population). We dichotomized the WMH WHODAS scores because their skewed distribution meant that a mean score was not a good characterization of central tendency in the general population. The decision to use the 90th percentile as the cut-point, rather than some other percentile, was somewhat arbitrary, but was based on looking at the distributions of each of the surveys, and consideration of the percentage of the samples with significant disability (which we took to indicate more clinically relevant impairment). The 95th percentile appeared to be too high a threshold and the 85th percentile too low.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of a WMH WHODAS score on or above the 90th percentile was calculated for those with a given physical condition (in the absence of mental disorder), for those with mental disorder (in the absence of the physical condition), for those with both mental disorder and the physical condition, and for those with neither, on a country-by-country basis. These prevalence estimates do not control for age and sex differences across the disorder groups.

Because the tests for additive interactions were to be run on the combined data set, we first ran a check on whether pooling the data would obscure significant variability between countries. Separate logistic regression models were run for each physical condition, for each country, estimating the age- and sex-adjusted odds of severe disability among those with mental disorder (in the absence of a given physical disorder) and the given physical disorder (in the absence of mental disorder). We assessed whether the heterogeneity of the odds ratio estimates across surveys was greater than expected by chance (DerSimonian & Laird, 1986), using an ± of p<0.01. None of the tests were found to be significant (data available on request).

To assess the interaction between mental disorder and a given physical condition on an additive scale but using logistic regression modelling (Andersson et al. 2005), the two risk factors (mental disorder and a given physical condition) were coded into three dummy variables: (i) those with mental disorder in the absence of the physical condition (MD), (ii) those with a given physical condition in the absence of mental disorder (PC), and (iii) those with both mental disorder and the physical condition (MD+PC). The group with neither mental disorder nor the physical condition was the common reference category. These dummy variables were entered simultaneously into logistic regression models predicting the odds of a WMH WHODAS score on or above the 90th percentile, controlling for age, sex and education (with the exception that France did not collect information on education). A separate model was run for each of the six physical conditions. We assessed whether the odds of disability for the MD+PC group were significantly greater than the sum of the odds for MD and PC by calculation of a ‘synergy index’ (SI):

If there is no synergistic effect, SI=1, and a value significantly greater than 1 indicates a positive synergistic effect (Andersson et al. 2005).

A series of conventional logistic regression models were also run testing for interactions between mental disorder and each physical condition on a multiplicative scale.

For countries in which the cross-classification of mental disorder and the physical condition had a null cell, the odds ratio was not calculated. Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals for the odds ratios were estimated using the Taylor Series Linearization (Wolter, 1985) with SUDAAN software (SUDAAN, 2002) to adjust for clustering and weighting.

Results

Sample characteristics

The combined sample of those who completed the longer version of the interview (Part 1+Part 2) including the physical condition checklist was 42 697. The Part 2 sample in each country ranged in size from the smaller Asian surveys in Japan (887), Beijing (914) and Shanghai (714), to the larger samples in New Zealand (7312), the USA (5692), Israel (4859) and South Africa (4315). The proportion of the sample that was age 60 or greater was higher in the developed countries than the developing countries, and the percentage with 12 or more years of education was also generally higher in the developed countries. Further detail on sample characteristics is provided elsewhere (Scott et al. 2007).

Disability prevalence by disorder

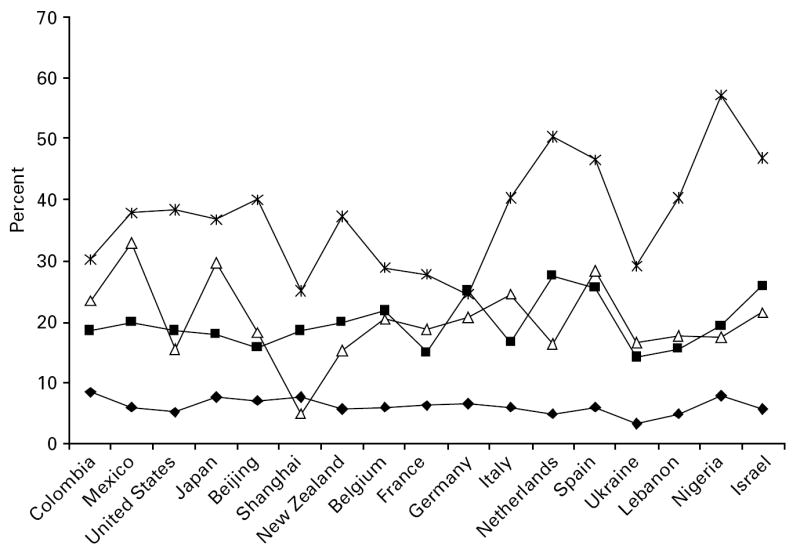

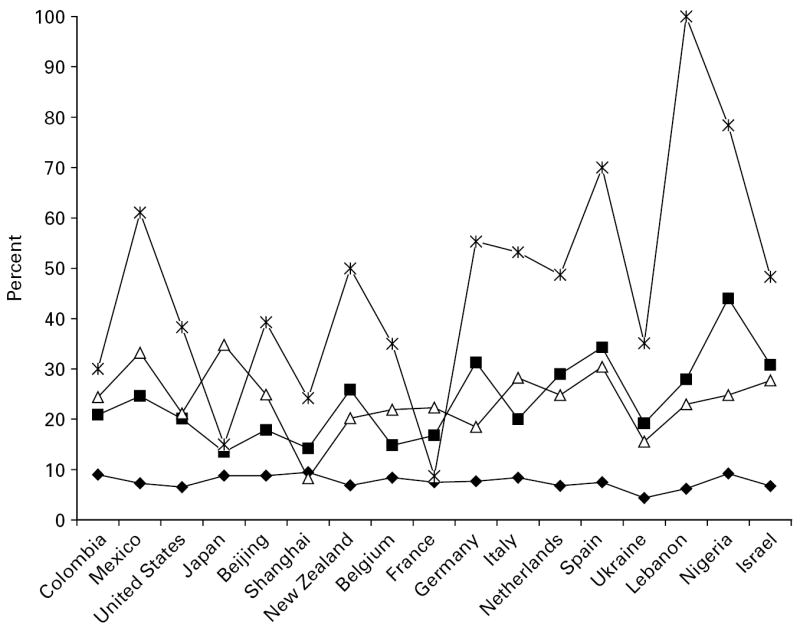

The prevalence of a disability score in the top 10% of the WMH WHODAS distribution was calculated for mental disorder and each of the physical condition groups, but by way of illustration only the results for back or neck pain and for heart disease are shown (Figs 1 and 2). These are reasonably indicative of the results obtained for the other four physical conditions (available on request). Generally speaking, those without either the physical or the mental condition were least likely to be represented among the most disabled 10%, whereas those with both mental disorder and the physical condition were most likely to be among the most disabled. It is important to note that these descriptive results are not adjusted for age and sex, which makes the distinctions between the four groups in terms of their disability status less clear-cut. It is also clear that there is a good deal of variability across countries. Although there are likely to be some substantive reasons for this, it is also partly a function of the fact that some of the surveys had low prevalences of mental disorders, and so of the co-morbidities, leading to potentially unstable estimates. For this reason the estimates based on the pooled dataset are likely to be the more reliable.

Fig. 1.

Percentage with a score in the top 10% of the WMH WHODAS distribution by mental disorder (–Δ–), chronic back or neck pain (–■–), both (– –) or neither (–◆–) (not adjusted for age or sex).

–) or neither (–◆–) (not adjusted for age or sex).

Fig. 2.

Percentage with a score in the top 10% of WMH WHODAS distribution by mental disorder (–Δ–), heart disease (–■–), both (– –) or neither (–◆–) (not adjusted for age or sex).

–) or neither (–◆–) (not adjusted for age or sex).

Pooled estimates

The results of the additive interaction models are shown in Table 1. The odds of severe disability in the three groups (MD, PC and MD+PC), plus the synergy index, are displayed for the six physical conditions. Three observations can be made. First, a comparison of first two columns of data indicates that the odds of severe disability were generally greater for mental disorder (in the absence of a given physical condition) than they were for any of the physical conditions (in the absence of mental disorder). Second, the odds of disability were always greater for those with both mental disorder and the physical condition, relative to either condition alone. Third, for all conditions except heart disease, there was a significant synergistic effect; that is, the odds of severe disability were significantly greater than the sum of the odds for the single conditions (equivalent to a positive interaction on an additive scale).

Table 1.

Odds of WMH WHODAS disability score ≥90th percentile, adjusted for age, sex and education, pooled data (n=42 697)

| Physical condition (PC)a |

Mental disorder (MD)b |

Mental disorder+physical condition (MD+PC) |

Synergy index (SI)c |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical condition | OR (95% CI)d | OR (95% CI)d | OR (95% CI)d | SI (95% CI) |

| Diabetes | 1.8 (1.5–2.1)* | 3.8 (3.5–4.2)* | 8.8 (6.9–11.1)* | 2.2 (1.6–2.9)* |

| Respiratory disease | 2.0 (1.7–2.3)* | 3.9 (3.6–4.3)* | 6.1 (5.0–7.4)* | 1.3 (1.0–1.7)* |

| Headache | 2.4 (2.1–2.7)* | 3.8 (3.5–4.2)* | 6.6 (5.8–7.6)* | 1.3 (1.1–1.6)* |

| Heart disease | 2.7 (2.3–3.2)* | 4.0 (3.7–4.3)* | 6.9 (5.7–8.4)* | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) |

| Arthritis | 2.5 (2.2–2.8)* | 4.0 (3.5–4.4)* | 8.1 (7.0–9.3)* | 1.6 (1.3–1.9)* |

| Back or neck pain | 3.4 (3.0–3.8)* | 4.0 (3.6–4.5)* | 9.2 (8.1–10.4)* | 1.5 (1.3–1.8)* |

WMH WHODAS, World Mental Health version of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

PC=the specified physical condition in the absence of mental disorder.

MD=either a 12-month depressive or 12-month anxiety disorder, or both, in the absence of the specified physical condition.

SI=[ORMD+PC − 1]/[(ORMD − 1)+(ORPC − 1)]. If there is no synergistic effect, SI=1, and a value significantly greater than 1 indicates a positive synergistic effect.

Common reference group: those with neither mental disorder nor the specified physical condition.

p<0.05.

When the interaction of mental disorder with the physical condition on disability was assessed within multiplicative models, no evidence of positive synergistic effects was found (data not shown; available on request). In sum, we observed combined effects of mental and physical conditions on disability that were greater than additive, but less than multiplicative.

Discussion

This first global investigation of the relationship between depressive/anxiety disorders and six chronic physical conditions with severe disability produced three key findings. First, those with mental disorders are more likely to be severely disabled than those with the physical conditions investigated here. Second, those with co-morbid mental and physical conditions are more likely to be severely disabled than those with either condition alone. Third, mental–physical co-morbidity exerts a small degree of synergistic effect, with the odds of severe disability among those with both mental disorder and a physical condition being significantly (albeit modestly) greater than the sum of the odds of the single conditions, with the exception of mental disorder–heart disease co-morbidity.

The finding of a synergistic effect of mental and physical co-morbidity adds to other evidence of this phenomenon (Kessler et al. 2001, 2003; Egede, 2004; Schmitz et al. 2007), although, as noted above, at least as many studies have found only additive effects. There are many methodological differences across studies that may account for the discrepancy between additive and synergistic findings, but one we noted earlier is that studies using logistic regression, when this is adapted to assess interactions additively (e.g. Egede, 2004; Schmitz et al. 2007; and the current study), are more likely to observe synergistic effects than when interactions are tested using multiplicative models (e.g. Stein et al. 2006). This can be observed directly in the current study in that the evidence for synergy was model dependent: it was observed in the additive interaction models but not in models assessing multiplicative interactions.

The particular contribution the current study makes is that it is the first study sampling from both developing and developed countries to specifically investigate the nature of the joint effect of mental and physical conditions on disability. Additionally, this study used a measure of severe disability, rather than any disability days (which can be influenced by brief, inconsequential illness), encompassed the full adult age range and used diagnoses of depression and anxiety disorders based on the full CIDI, rather than a short form or a scale measure of depression symptomatology. The degree of synergistic effect we observed was generally lower than that found by Schmitz et al. (2007), particularly for the joint effect of heart disease and depression. It seems probable that this is, at least in part, a function of the differences between the studies in terms of the methodological features just mentioned.

There are a number of ways in which the co-occurrence of mental and physical conditions could have synergistic effects on disability. One of these is through an underlying shared pathophysiology, such as that associated with the functioning of the autonomic nervous system [through the sympathetic–adrenal–medullary (SAM) system] and the neuroendocrine system [through the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical (HPA) axis]. Disturbances in both of these systems have been associated with depression and anxiety disorders (Heim & Nemeroff, 1999; McEwen, 2003; Goodyer, 2007) and with a range of physical disorders mediated by metabolic, cardiovascular and immune systems (McEwen, 1998; Chrousos & Kino, 2007; Cohen et al. 2007). Allostatic load refers to the cumulative biological wear and tear that occurs through sustained output of glucocorti-coids and catecholamines associated with chronic or repeated malfunction of the HPA and SAM axes (McEwen, 1998, 2003, 2007). Karlamanagla et al. (2002) found that a summary measure of allostatic load predicted functional decline independently of individual physiological markers, lifestyle and demographic variables, and baseline levels of functioning. Allostatic load may therefore be one mechanism through which the combined effect of different morbidities on functioning may be greater than the sum of the individual effects.

A second possible mechanism is through the frequently observed bi-directionality of relationship between co-morbid mental and physical disorders (Cohen & Rodriguez, 1995; Dew, 1998; Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2002). Bi-directionality may operate to compound both mental and physical components of the co-morbidity. Depression, for example, may facilitate the development of diabetes through the metabolic effects of overexposure to glucocorticoids as outlined above, but then the resulting disability and lifestyle changes required by the advent of diabetes can maintain or exacerbate the depression. Hence, a self-perpetuating feedback loop between mental and physical disorders can develop; their co-morbidity then operates to increase the morbidity of each disorder, and so too the associated disability.

Other mechanisms for a synergistic effect of mental–physical co-morbidity on disability include the possibility that depression may exacerbate the disabling effect of a chronic physical condition through its influence on treatment adherence and health behaviours (Cohen & Rodriguez, 1995; Ciechanowski et al. 2000; Evans et al. 2005). Depression can also interfere with the psychological capacity to adjust to physical conditions (Sharpe & Curran, 2006) and can affect the perception and appraisal of pain, and the ability to cope with it (Campbell et al. 2003; Van Puymbroeck et al. 2007). Finally, it is possible that mental co-morbidity is a marker of physical condition severity, and it is the severity of the condition that increases the associated disability relative to those physical conditions occurring in the absence of mental disorder (Stein et al. 2006).

This topic has important clinical ramifications. Schettini Evans & Frank (2004) take the view that if two conditions have additive effects on disability, this indicates that both need to be targeted for treatment to reduce their joint disability burden, and if two conditions have synergistic effects, novel treatments need to be designed and targeted to particular co-morbidities. We are uncertain that the synergistic effects of co-morbid disorders means that novel treatments have to be designed, but we do consider that these and other similar results present a strong case for the need to treat both conditions. Although this may seem a common-sense conclusion, it is apparently not always the one adopted by clinicians when confronted with mental–physical co-morbidity. For example, some physicians in medical settings take the view that mental disorder is an understandable consequence of physical disease that does not require a specific treatment focus (Evans et al. 2005). Similarly, some mental health clinicians consider that ‘living with a mental illness is generally such a struggle that physical health is of lesser importance’ (Hyland et al. 2003).

These findings need to be interpreted within the context of the study limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the surveys means that it cannot be assumed that the disability measured here is a consequence of either the mental or the physical conditions reported. A second limitation is that the physical conditions were ascertained by a standard check-list, rather than a physician’s examination, which contrasts with the detailed assessment of mental disorders. One of the effects of this limited assessment is that we have no information on severity, which means we cannot draw conclusions about its contribution to the finding of synergy. While acknowledging the limitation of self-report, methods research indicates that self-report of diagnosis generally shows good agreement with medical records data (Kehoe et al. 1994; NCHS, 1994; Kriegsman et al. 1996), and the presence of depressive or anxiety symptoms has not been found to bias or inflate the self-report of diagnosed physical conditions (Kolk et al. 2002).

A third limitation is that the analyses of each physical condition did not control for co-morbidity with other physical conditions. Additionally, mental disorders not included in the depression-anxiety spectrum were not controlled for in the analyses. This may mean that the distinctions between the groups are less clear-cut than their labelling implies, but it seems unlikely to have affected the pattern of results.

Fourth, the cutpoint for defining disability (on or above the 90th percentile of the WMH WHODAS for each country) may not mean the same thing in different countries. The proportion of each country with any disability on the WMH WHODAS showed considerable cross-national variation (Von Korff et al. in press), so it is possible that the nature of the disability experienced by the 10% most disabled in a given population would also vary. Other results from the WMH surveys show marked cross-national differences in prevalences of mental disorders (Demyttenaere et al. 2004), and it is not currently possible to disentangle differences in prevalence from reporting differences as a function of differing conceptualizations of mental disorder. Despite these limitations to cross-national comparisons, in the present study there was a general tendency for those with both conditions to be more likely to be severely disabled relative to either condition alone; a pattern that occurred in the majority of countries. Moreover, the heterogeneity analyses did not indicate significant variability in pooled estimates across countries.

In conclusion, this first cross-national study of the joint effect of mental and physical conditions on the probability of severe disability adds to a growing body of studies in finding that co-morbidity exerts modest synergistic effects, such that the combined disabling effect of mental and physical conditions is somewhat greater than the summed effects of the individual conditions. There are a number of mechanisms, biological, behavioural and psychological, that could account for these results. Clinicians need to rise to the challenge of according both mental and physical conditions equal priority, in order for co-morbidity to be adequately managed and disability reduced.

Acknowledgments

The surveys discussed in this article were carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R01-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Bristol–Myers Squibb. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. The Chinese World Mental Health Survey Initiative is supported by the Pfizer Foundation. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection, with supplemental support from the Saldarriaga Concha Foundation. The ESEMeD project is funded by the European Commission (Contracts QLG5-1999-01042; SANCO 2004123), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CIBER CB06/02/0046, RETICS RD06/0011 REM-TAP), and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The Israel National Health Survey is funded by the Ministry of Health with support from the Israel National Institute for Health Policy and Health Services Research and the National Insurance Institute of Israel. The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (LEBANON) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from Janssen Cilag, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Novartis. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544-H), with supplemental support from the PanAmerican Health Organization (PAHO). Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) is supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council, and the Health Research Council. The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) is supported by the WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria), and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. The South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH) is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. The Ukraine Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption (CMDPSD) study is funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (RO1-MH61905). The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest None.

References

- Ahlbom A, Alfredsson L. Interaction: a word with two meanings creates confusion. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;20:563–564. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-4410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson T, Alfredsson L, Kallberg H, Zdravkovic S, Ahlbom A. Calculating measures of biological interaction. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;20:575–579. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-7835-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Armenian HK, Pratt LA, Gallo J, Eaton WW. Psychopathology as a predictor of disability: a population-based follow-up study in Baltimore, Maryland. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;148:269–275. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist-Bouwman MA, de Graaf R, Vollebergh WAM, Ormel J. Comorbidity of physical and mental disorders and the effect on work-loss days. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;111:436–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LC, Clauw DJ, Keefe FJ. Persistent pain and depression: a biopsychosocial perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GP, Kino T. Glucocorticoid action networks and complex psychiatric and/or somatic disorders. Stress. 2007;10:213–219. doi: 10.1080/10253890701292119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:3278–3285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298:1685–1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Rodriguez MS. Pathways linking affective disturbances and physical disorders. Health Psychology. 1995;14:374–380. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.5.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, De Girolamo G, Morosini P, Polidori G, Kikkawa T, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Takashima T, Uda H, Karam EG, Fayad JA, Karam AN, Mneimneh ZN, Medina Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, De Graaf R, Ormel J, Gureje O, Shen Y, Huang Y, Zhang M, Alonso J, Haro JM, Vilagut G, Bromet EJ, Gluzman S, Webb C, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, Anthony JC, Von Korff MR, Wang PS, Brugha TS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Lee S, Heeringa S, Pennell BE, Zaslavsky AM, Ustun TB, Chatterji S. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dew MA. Psychiatric disorder in the context of physical illness. In: Dohrenwend BP, editor. Adversity, Stress and Psychopathology. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. pp. 177–218. [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Marcus SC, Rosenheck RA, Olfson M, Tanielian MA, Pincus HA. Understanding disability in mental and general medical conditions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1485–1491. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.9.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egede LE. Diabetes, major depression, and functional disability among US adults. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:421–428. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, Golden JM, Ranga Rama Krishnan K, Nemeroff CB, Bremner JD, Carney RM, Coyne JC, Delong MR, Frasure-Smith N, Glassman AH, Gold PW, Grant I, Gwyther L, Ironson G, Johnson RL, Kanner AM, Katon WJ, Kaufmann PG, Keefe FJ, Ketter T, Laughren TP, Leserman J, Lyketsos CG, McDonald WM, McEwan BS, Miller AH, Musselman D, O’Connor C, Petitto JM, Pollock BG, Robinson RG, Roose SP, Rowland J, Sheline Y, Sheps DS, Simon G, Spiegel D, Stunkard A, Sunderland T, Tibbits P, Valvo WJ. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer IM. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis: cortisol, DHEA and mental and behavioral function. In: Steptoe A, editor. Depression and Physical Illness. Cambridge University Press; London: 2007. pp. 280–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K. Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:11–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The impact of early adverse experiences on brain systems involved in the pathophysiology of anxiety and affective disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:1509–1522. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland B, Judd F, Davidson S, Jolley D, Hocking B. Case managers’ attitudes to the physical health of their patients. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;37:710–714. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2003.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla AS, Singer BH, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Seeman TE. Allostatic load as a predictor of functional decline: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2002;55:696–710. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe R, Wu S-Y, Leske MC, Chylack LT. Comparing self-reported and physician reported medical history. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1994;139:813–818. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Bergland P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, Jin R, Pennell B-E, Walters EE, Zaslavsky A, Zheung H. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Greenberg PE, Mickelson KD, Meneades LM, Wang PS. The effects of chronic medical conditions on work loss and work cutback. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2001;43:218–225. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ormel J, Demler O, Stang PE. Comorbid mental disorders account for the role impairment of commonly occurring chronic physical disorders: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003;45:1257–1266. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000100000.70011.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun B. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: new perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:83–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolk AM, Hanewald GJ, Schagen S, Gijsbers van Wijk CM. Predicting medically unexplained physical symptoms and health care utilization. A symptom-perception approach. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;52:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, Van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1996;49:1407–1417. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Mood disorders and allostatic load. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:200–207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews. 2007;87:873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Ames M, Cui L, Stang PD, Ustun B, Von Korff M, Kessler R. The impact of comorbidity of mental and physical conditions on role disability in the US adult household population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1180–1188. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCHS. Evaluation of National Health Interview Survey diagnostic reporting. Vital and Health Statistics. Series 2. 1994;120:1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Kempen GIJM, Deeg DJH, Brilman EI, Sonderen E, Relyveld J. Functioning, wellbeing, and health perception in late middle-aged and older people: comparing the effects of depressive symptoms and chronic medical conditions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998;46:39–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Petukhova M, Chatterji S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bromet EJ, Burger H, Demyttenaere K, de Girolamo G, Haro JM, Hwang I, Karam E, Kawakami N, Lepine JP, Medina-Mora ME, Posada-Villa J, Sampson N, Scott KM, Ustun B, Von Korff M, Williams D, Zhang M, Kessler RC. Disability and treatment of specific mental and physical disorders across the world: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. British Journal of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039107. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Jacobi F, Cox BJ, Belik S-L, Clara I, Stein MB. Disability and poor quality of life associated with comorbid anxiety disorders and physical conditions. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:2109–2116. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.19.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schettini Evans A, Frank SJ. Adolescent depression and externalizing problems: testing two models of comorbidity in an inpatient sample. Adolescence. 2004;39:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz N, Wang J, Malla A, Lesage A. Joint effect of depression on chronic conditions on disability: results from a population-based study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:332–338. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31804259e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Bruffaerts R, Tsang A, Ormel J, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Benjet C, Bromet E, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Gasquet I, Gureye O, Haro JM, He Y, Kessler RC, Levinson D, Mneimneh ZN, Oakley Browne MA, Posada-Villa J, Stein DJ, Takeshima T, Von Korff M. Depression-anxiety relationships with chronic physical conditions: results from the World Mental Health surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;103:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, McGee M, Wells J, Oakley Browne M. Disability in Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006a;40:889–895. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Oakley Browne MA, McGee MA, Wells JE. Mental-physical comorbidity in Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006b;40:882–888. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe L, Curran L. Understanding the process of adjustment to illness. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:1153–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, Belik S-L, Sareen J. Does co-morbid depressive illness magnify the impact of chronic physical illness: a population-based perspective. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:587–596. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUDAAN. SUDAAN software, version 8.0.1. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van Puymbroeck CM, Zautra AJ, Harakas PP. Chronic pain and depression: twin burdens of adaptation. In: Steptoe A, editor. Depression and Physical Illness. Cambridge University Press; London: 2007. pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Crane PK, Ormel J, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, de Graaf R, Huang Y, Iwata N, Karam EG, Kovess V, Lara C, Levinson D, Posada-Villa J, Scott KM, Vilagut G. Modifications to the WHODAS-II for the World Mental Health Surveys: lessons learned. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology in press. [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Golding JM, Burnam MA. Affective, substance use, and anxiety disorders in persons with arthritis, diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, or chronic lung conditions. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1989a;11:320–327. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(89)90119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989b;262:914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]