Abstract

Human serum transferrin (hTF) is a bilobal glycoprotein that transports iron to cells. At neutral pH, diferric hTF binds with nM affinity to the transferrin receptor (TFR) on the cell surface. The complex is taken into the cell where, at the acidic pH of the endosome (~pH 5.6), iron is released. Since iron coordination strongly quenches the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of hTF, the increase in the fluorescent signal reports the rate constant(s) of iron release. At pH 5.6, the TFR considerably enhances iron release from the C-lobe (with little effect on iron release from the N-lobe). The recombinant soluble TFR is a dimer with 11 tryptophan residues per monomer. In the hTF/TFR complex these residues could contribute to and compromise the readout ascribed to iron release from hTF. We report that compared to FeC hTF alone, the increase in the fluorescent signal from the preformed complex of FeC hTF and the TFR at pH 5.6 is significantly quenched (75%). To dissect the contributions of hTF and the TFR to the change in fluorescence, 5-hydroxytryptophan was incorporated into each using our mammalian expression system. Selective excitation of the samples at 280 or 315 nm shows that the TFR contributes little or nothing to the increase in fluorescence when ferric iron is released from FeC hTF. Quantum yield determinations of TFR, FeC hTF and the FeC hTF/TFR complex strongly support our interpretation of the kinetic data.

Keywords: Metalloproteins, protein-receptor interaction, tryptophan analogues, tryptophan fluorescence, stopped-flow kinetics, BHK cells

1. Introduction

Human serum transferrin (hTF) is an ~80 kDa bilobal iron binding glycoprotein that delivers iron to cells by means of receptor mediated endocytosis. The N- and C-lobes are homologous globular domains each capable of binding an atom of ferric iron (Fe3+) in a cleft formed by two subdomains (N1–N2 and C1–C2) in each lobe [1]. At the neutral pH of ~7.4, diferric hTF (Fe2 hTF) preferentially binds with nM affinity to the extracellular portion of the membrane spanning hTF receptor (TFR) on the cell surface. At this pH, the two monoferric species bind less tightly than Fe2 hTF and apo hTF binds very poorly [2]. In normal, healthy individuals, ~30% of the circulating hTF is iron saturated [3]. At the acidic pH of the endosome (~5.6) iron is released from Fe2 hTF and delivered to the cell; at low pH, apo hTF remains bound to the TFR and is returned to the cell surface where it diffuses into the plasma to transport more ferric iron [4].

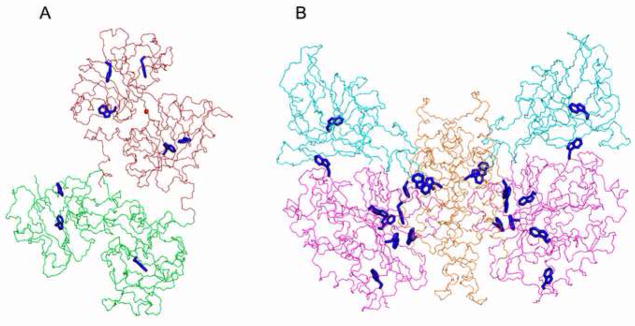

Iron coordination by hTF produces a ligand to metal charge transfer band, centered at ~470 nm, which is responsible for the characteristic salmon pink color of hTF. This coordination also disrupts the π to π* transition of the two liganding tyrosine residues (Tyr95 and Tyr188 in the N-lobe and Tyr426 and Tyr517 in the C-lobe) resulting in an increase in the absorbance at 280 nm and creating a shoulder that extends to ~ 410 nm [5]. This shoulder overlaps with the fluorescent signal of the tryptophan residues causing a significant decrease in the intrinsic fluorescence of Fe2 hTF (~70 %) compared to apo hTF [6]. These findings served as a basis for the development of various assays to accurately measure the uptake or release of iron from hTF. Although monitoring the decrease in the visible absorbance spectrum has been extensively used to measure the rate constant(s) for iron release, the most sensitive assays measure the increase in the intrinsic fluorescent signal when the iron is removed by a chelator. Recently, recombinant production of the isolated N-lobe and of full length hTF (modified by mutation to prevent iron binding in one or both lobes) has allowed a more precise assignment of the contributions of each lobe to the spectral properties of hTF [7–9]. The change in the intrinsic fluorescent signal is attributed to the eight Trp residues in hTF (three in the N-lobe and five in the C-lobe, Fig. 1 A). The sensitivity of this approach has proved to be especially critical to the measurement of the rate of iron release from hTF bound to TFR isolated from placenta [10], both because of the limited amount of TFR and its poor solubility at low pH [11]. Work from Aisen and colleagues has established the vital role of the TFR in assuring that iron is released at the appropriate time and in the appropriate place [12–14]. Thus at pH 7.4, the presence of the TFR actually slows the release of iron from each lobe of hTF, while at pH 5.6 the TFR considerably accelerates iron release from the C-lobe of hTF (with little effect on the N-lobe) [15–17].

Fig. 1.

A. Structure of monoferric C-lobe hTF [42] depicting the 8 tryptophan residues, shown in blue. N-lobe is colored green, C-lobe is colored dark red. The bound iron is shown in red. B. Structure of sTFR (1CX8) depicting the 22 tryptophan residues in the dimer (blue). The subdomains are colored as follows, helical (orange), apical (magenta) and protease-like (teal). Figure was made using PyMol.

Availability of a recombinant form of the soluble hTF binding portion of the TFR (sTFR) has simplified iron release assays by eliminating the need for detergent [17–19]. Additionally, relatively large amounts of sTFR can be produced to allow a more extensive determination of the role of the TFR in iron release from the two lobes as a function of pH and salt [17]. Such work is essential to fully understand the complexities of iron release from hTF in order to be able to modify its properties in a clinical setting. The interaction of hTF with its specific receptor controls iron distribution throughout the body. Owing to the fact that iron deficiency and excess are directly related to specific human diseases, understanding this process at the molecular level should result in a more comprehensive understanding of iron metabolism [20].

In measuring iron release from the hTF/sTFR complex by fluorescence, a key issue is whether the sTFR might contribute to the increase in the fluorescent signal. Since there are 11 Trp residues per monomer of sTFR (Fig. 1B), this is both a valid and a very important question. If (as is highly likely), one or more of the 11 Trp residues in the sTFR undergoes a pH induced change in its local environment, it would result in an increase (or a decrease) in the intrinsic fluorescent signal which could compromise an accurate determination of the rate of iron release from hTF. This potential problem has never been addressed experimentally. The crystal structure of the sTFR dimer reveals that each monomer is comprised of: 1) a protease-like domain (resembling amino and carboxypeptidases, residues 122–188 and 384–606), 2) an apical domain (residues 189–383) and 3) a helical domain (residues 607–760), which spontaneously associates with another monomer to form the dimer (Fig. 1B) [21]. Six of the eleven Trp residues reside in the protease-like domain, four are found in the helical domain and one is located in the apical domain (Table 1). A cryo-EM model of the TF/sTFR complex suggests that the C1 subdomain of TF binds to the helical domain of the sTFR [22]. Additionally, the N-lobe appears to make contact with both the helical domain and the protease-like domain through the N1 and N2 subdomains. We note that placement of the two lobes of TF into the cryo-EM density map required a 9 Å movement of the N-lobe relative to the C-lobe. In a remarkable study, thirty different mutants of the TFR were evaluated to determine the effect of a particular mutation on binding of Fe2 hTF, apo hTF and the HFE protein as a function of pH [23]. Relevant to the current work, two of the four Trp residues examined affected the binding affinity. The W124A sTFR mutant showed a 15-fold reduction in binding affinity of Fe2 hTF to sTFR at pH 7.4, but no change in binding of apo hTF at pH 6.3. Conversely, the W641A mutant resulted in a 55-fold reduction in affinity for apo hTF at pH 6.3 without any effect on the binding of Fe2 hTF at pH 7.4 [23]. Of great significance, a double sTFR mutant in which Trp641and Phe760 were each replaced with alanine reduced binding and abolished receptor stimulated iron release at pH 5.6 from full length hTF that binds iron only in the C-lobe (FeC hTF) [23].

Table 1.

Analysis of Trp residue locations/environment in the crystal structure of the sTFR (1CXS) [21].

| Residue # | Domain | Environment | Tested Experimentally[22] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trp124 | Protease-like | Solvent exposed | Yes, involved in binding hTF @ pH 7.4 |

| Trp 182 | Protease-like | Burieda | No |

| Trp 357 | Apical | Solvent exposed | No |

| Trp 412 | Protease-like | Solvent exposed | No |

| Trp 453 | Protease-like | Burieda | No |

| Trp 466 | Protease-like | Burieda | No |

| Trp 528 | Protease- | Solvent exposed | Yes, no effect |

| Trp 641 | Helical | Solvent exposed | Yes, involved in binding to C-lobe of hTF @ pH 6.3 and 5.6 [15] |

| Trp 702 | Helical | Buried | Yes, no effect |

| Trp 740 | Helical | Buried between monomers | No |

| Trp 754 | Helical | Burieda | No |

Trp residues 182, 453, 466 and 754 (from opposite monomer) are buried and clustered together

One approach to dissect the spectral properties of one protein in a complex with another protein is to substitute an unnatural amino acid analogue with unique spectral properties for the native amino acid [24]. Native Trp contains two overlapping electronic π-π* transitions between 240–290 nm (1La and 1Lb) [25]. Experimental and theoretical predictions show that the 1La transition is the dominant fluorescing state of Trp in proteins [26, 27]. This transition gives rise to the sensitivity of Trp residues to changes in their local environment due to the large dipole change upon excitation. L-5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) is a Trp analogue with an absorbance spectrum that is significantly red-shifted compared to native Trp [28]. This extended shoulder results from the shift of the 1Lb transition of 5-HTP to lower energy which allows it to be selectively excited at wavelengths ≥310 nm and distinguished from native Trp [29]. To elucidate whether or not the sTFR is contributing to the increase in the fluorescent signal ascribed to the release of iron from hTF, we have incorporated 5-HTP in place of Trp in both FeC hTF and also in recombinant sTFR. This was accomplished using our mammalian BHK cell expression system. The steady-state spectral properties of FeC hTF and sTFR with and without the 5-HTP substitution are reported. When excited at 280 nm, iron release from native and 5-HTP FeC hTF (in the absence of sTFR) both yield similar rate constants indicating that the presence of the hydroxyl group on the Trp residues does not interfere with this process. The presence of 5-HTP in sTFR appears to have some effect on receptor stimulated iron release. However, we demonstrate that the increase in the intrinsic fluorescent signal observed at pH 5.6 for the hTF/sTFR complex can be assigned to iron removal from hTF with minimal contributions from the sTFR, thereby validating the Trp fluorescence iron release assay for the hTF/sTFR complex.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Custom made Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-Ham F-12 nutrient mixture (lacking L-Trp, L-Arg, L-Lys, L-His, L-Met, L-Phe and L-Tyr), antibiotic-antimycotic solution (100X), 5-HTP, all the L-amino acids mentioned above and trypsin solution were from the GIBCO-BRL Life Technologies Division of Invitrogen. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Norcross, GA) and was tested prior to use to ensure adequate growth of our BHK cells. Ultroser G (UG) is a serum replacement from Pall BioSepra (Cergy, France). Ni-NTA resin was purchased from Qiagen. Corning expanded surface roller bottles and Dynatech Immunolon 4 Removawells were obtained from Fisher Scientific. The Hi-Prep 26/60 Sephacryl S-200HR and S-300HR columns were from Amersham Pharmacia. Guanidine hydrochloride (GdHCl) was from Pierce. Centricon 30 microconcentrators and YM-30 ultrafiltration membranes were from Millipore/Amicon. All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2. Protein production and purification

The DNA manipulations used to generate FeC hTF and the sTFR have been described in detail previously [8, 17]. To produce recombinant samples with 5-HTP substituted for Trp, BHK cells transfected with the pNUT plasmid containing the appropriate cDNA sequence were placed into four expanded surface roller bottles [30]. Briefly, adherent BHK cells were grown in DMEM-F12 containing 10% FBS. This medium was changed twice at two day intervals, followed by addition of DMEM-F12 containing the serum substitute UG (1%) and 1 mM butyric acid (BA). The presence of 1 mM BA has been shown to increase the production of recombinant protein from BHK cells [8]. After one or two changes in this medium, 200 mL of DMEM-F12 containing 5-HTP (9.0 mg/L), with BA and UG was added to each roller bottle twice at two day intervals. (Note that the DMEM-F12 was made complete by addition of the other 6 missing L-amino acids). Addition of culture medium containing 5-HTP results in a significant deterioration of the cells. In order to maximize the incorporation, medium containing 5-HTP was added when production of FeC hTF or sTFR was highest as determined by a competitive immunoassay using specific monoclonal antibodies to either hTF or sTFR [31]. The hexa His-tagged recombinant proteins in the medium were captured by passage over a Ni-NTA column followed by final purification on a gel filtration column (S-200HR for hTF and S-300HR for sTFR) [8, 17]. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of SDS was used to verify the homogeneity of the all of the recombinant proteins.

FeC hTF/sTFR complexes were prepared by adding a slight molar excess of sTFR to FeC hTF and reducing to a concentration of 10 mg/mL (with respect to FeC hTF) using a YM30 Centricon microconcentrator. Alternatively, the complex was made with a small molar excess of FeC hTF and isolated by passage over an S-300 column. The four possible combinations of FeC hTF and sTFR were made ranging from both in native form to both labeled with 5-HTP.

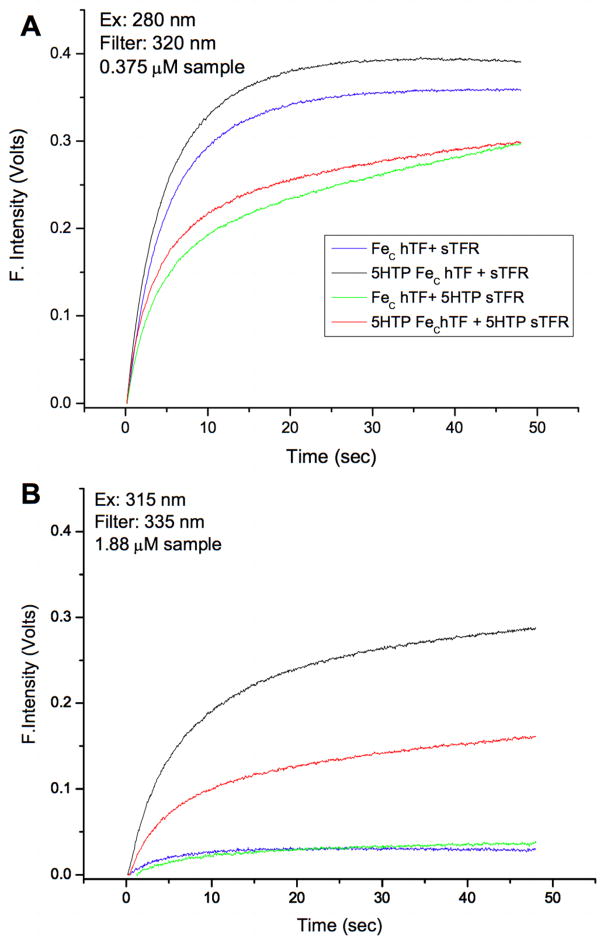

2.3. Kinetics of iron release

Kinetic assays in the absence or presence of sTFR were carried out using an Applied Photophysics (AP) SX.18MV stopped-flow spectrofluorometer as previously described [9, 17]. A monochromator was used for excitation wavelength selection (280 nm for native Trp and 315 nm for 5-HTP excitation), with a bandpass of 9.3 nm. A 320 nm cut-on filter was used to monitor native Trp fluorescence while a 335 nm cut-on filter was used to monitor emission from 5-HTP labeled samples. One syringe contained 375 nM of complex with respect to FeC hTF or 5-HTP FeC hTF for 280 nm excitation (or 1.88 μM for 315 nm excitation) in 1.0 mL of 300 mM KCl (pH ~6.8). The other syringe contained 200 mM MES, pH 5.6 with 300 mM KCl and 8 mM EDTA. Data was collected for 50 seconds (complex) or 500 seconds (FeC hTF alone); a total of at least six kinetic traces were combined and averaged. Data was analyzed using Origin 7.5 software and fitting to either a single exponential function (y = A1*exp(−x/t1) + y0) or a double exponential function (y = A1*exp(−x/t1) + A2*exp(−x/t2) + y0).

2.4. Quantum Yields of Native Tryptophan Samples

Quantum yields of native hTF, sTFR and the hTF/sTFR complex were determined in comparison to an L-tryptophan standard (Φ = 0.14) using a Quantamaster-6 Spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International, South Brunswick, NJ) [9, 32]. L-tryptophan (10 μM) and protein samples (~ 0.5 μM) were added to a cuvette containing either 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 (FeC hTF) or 100 mM MES, pH 5.6, 300 mM KCl and 4 mM EDTA (Apo hTF) and equilibrated at 25°C for 20 minutes. Samples were excited at 280 nm, with 1 nm excitation slits. Emission scans were recorded and integrated between 305–400 nm (4 nm emission slits) with a 320 nm cut-on filter in front of the emission monochromator and PMT.

2.5. Steady-State Fluorescence Scans

Corrected steady-state fluorescence spectra were obtained for native apo hTF, 5-HTP apo hTF, native sTFR or 5-HTP sTFR (~2 μM). In each case, sample was added to a cuvette (1.8 mL final volume) containing 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 and gently stirred with a small magnetic stir bar. FeC hTF was generated by adding a slight molar excess of Fe-NTA to the apo sample and equilibrating for 20 minutes. Native and 5-HTP labeled hTF and sTFR constructs were excited at 280 and 315 nm, respectively. Slit widths of 1 nm (excitation) and 0.5 nm (emission, 2 nm for 315 nm excitation) were used. In the case of excitation at 280 nm, emission scans were collected between 305–400 nm; for excitation at 315 nm emission between 325–400 nm was recorded. Excitation scans were then collected by setting the emission wavelength to the λmax and scanning between 250–330 nm.

2.6. Determination of 5-HTP incorporation

Incorporation of 5-HTP was estimated by comparative analysis of absorbance spectra as described [33] on a Varian Cary 100 with temperature control. The absorbance spectrum (269–324 nm) of FeC hTF and the sTFR (each at a concentration of 10 μM) and of 5-HTP alone (100 μM) was recorded in 6 M GdHCl (see below).

3. Results

3.1. Kinetics of iron release from native FeC hTF and FeC hTF/sTFR

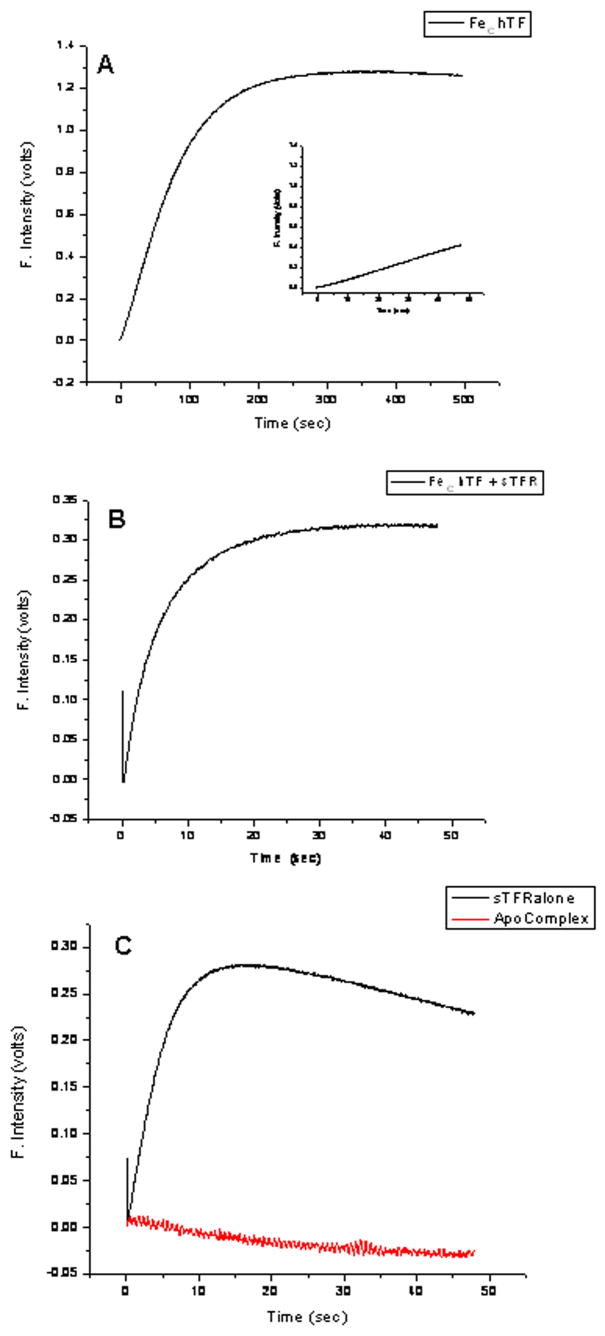

Our standard protocol for monitoring iron release involves rapid mixing (by means of a stopped-flow device) of low pH buffer, salt and a chelator with FeC hTF or the FeC hTF/sTFR complex. Typical results are shown in Fig. 2A and 2B. It is immediately clear that both the change in fluorescence and the time scale of iron release between these two samples are drastically different in spite of the fact that the same amount of FeC hTF is present in each. Binding of FeC hTF to the sTFR results in a ~75 % reduction in the change (1.25 volts versus 0.31 volts) during iron release with a 10-fold reduction in the time needed to assure complete iron removal. Of interest is the appearance of a new feature in the beginning of the kinetic trace of the complex (Fig. 2B); an initial small drop in the intensity of the fluorescence (within the first 0.2 sec) is followed by the large increase that plateaus (0.31 volts) by ~25 seconds (and is ascribed to iron release). Examination of the change in fluorescence of sTFR alone under our standard conditions (Fig. 2C, black curve), shows that the initial decrease in the scan of the complex can be assigned to the sTFR. To validate this assignment we monitored the change in the fluorescent signal of FeC hTF on the same timescale. As shown in the inset of Fig. 2A, the initial decrease is completely absent. The time-based change in fluorescence of the sTFR alone shows a significant initial increase in the signal (0.28 volts) that peaks at ~15 sec and is followed by a slow but steady decrease in the signal. Since it is known that the sTFR is not very stable at low pH and tends to aggregate in the absence of hTF [11], aggregation might lead to quenching of the fluorescent signal, although other explanations, such as photobleaching may be are equally possible. Regardless, there is a falling off of the signal. Significantly, apo hTF bound to sTFR yields no change in signal at low pH (Fig. 2C, red curve).

Fig. 2.

Stopped flow time-based change in fluorescence of A. FeC hTF in the absence of sTFR. Inset is iron release on the same timescale as B and C. (Note that the initial quench in fluorescence is not present). B. FeC hTF/sTFR complex. C. sTFR in the absence of hTF (black curve). sTFR in the presence of apo hTF (red curve). All samples are in 100 mM MES, pH 5.6, containing 300 mM KCl and 4 mM EDTA. Excitation at 280 nm, emission using a 320 nm cut-on filter. NOTE differences in X and Y scales.

3.2. Quantum yield determination

To further measure the effect of binding of FeC hTF to the sTFR on the change in the fluorescent signal, the quantum yields (Φ) of FeC hTF alone, the sTFR alone and the FeC hTF/sTFR complex at both pH 7.4 and pH 5.6 were determined. These pH values were selected to simulate the iron-bound serum hTF and the apo conformation within the endosome. Significantly, all of the samples show at least some increase in the Φ at pH 5.6 compared to pH 7.4 varying from 20% for the sTFR alone to 100% for hTF alone (Table 2). The Φ of the sTFR at both pH values is considerably higher than the Φ of the FeC hTF alone or in the complex. For example, at pH 7.4, the Φ is 233% and 43% higher for sTFR alone in comparison to FeC hTF or the FeC hTF/sTFR complex, respectively. At pH 5.6, the Φ is 100% and 33% higher for sTFR alone compared to FeC hTF or the FeC hTF/sTFR complex.

Table 2.

Quantum yields (Φ) of FeC hTF, sTFR and FeC hTF/sTFR complex as a function of pH and the presence or absence of irona

| Starting Sample | Φ, Fe HEPES, pH 7.4 | Φ, apo MES, pH 5.6b | % diff. ΦHEPES and ΦMESc |

|---|---|---|---|

| FeC hTF | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 100 |

| sTFR | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 20 |

| FeC hTF/sTFR | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 29 |

Values were determined by comparison to a known standard (L-Trp) and calculated as described [32].

Samples were incubated in buffer for 20 minutes in the presence of EDTA and KCl.

Percent difference is calculated using 100 * [ΦHEPES - ΦMES]/ΦHEPES

Given the large effect of binding of FeC hTF to the sTFR on the change in the fluorescent signal and the fact that a fluorescent signal is observed for the sTFR alone as a function of the change in pH (Fig. 2A–C), we needed a means to definitively dissect the contribution of each. Therefore 5-HTP labeled FeC hTF and sTFR were produced in our BHK cell expression system. Substituting 5-HTP for L-Trp in the medium resulted in an immediate and substantial decrease in protein production relative to the production of native FeC hTF and sTFR (~6–8 mg/L maximum versus ~50 mg/L for FeC hTF and ~35 mg/L for sTFR [8, 17]). Nevertheless, in each case, enough 5-HTP labeled protein (~3 mg) was recovered to carry out both the spectral measurements and the iron release experiments.

3.3. Determination of the incorporation of 5-HTP

The percent of 5-HTP incorporated into FeC hTF and sTFR was estimated from equation (1) [33]:

| (1) |

where, SNA 5-HTP, SNA 5-HTP-protein, and SNA-protein represent the area under the curve of the normalized absorbance (NA) spectra of 5-HTP, 5-HTP-protein and native protein. The incorporation of 5-HTP in FeC hTF and sTFR was calculated to be 20 and 26%, respectively. The transcriptional process in BHK cells could only result in random incorporation of 5-HTP into at the 8 positions in hTF and the 11 positions in the sTFR. Since the Trp residues are well distributed in the primary sequences, site specific incorporation is not reasonable (or even feasible) in this mammalian expression system. We note that two strategies to improve the level of incorporation did not enhance our percentage of incorporation: 1) Inclusion of a four hour wash-in period with complete medium containing 5-HTP prior to the batch that was collected and processed, and 2) addition of 80% 5-HTP and 20% L-Trp to the complete medium instead of 100% 5-HTP.

3.4. Corrected excitation and emission spectra of proteins containing 5-HTP

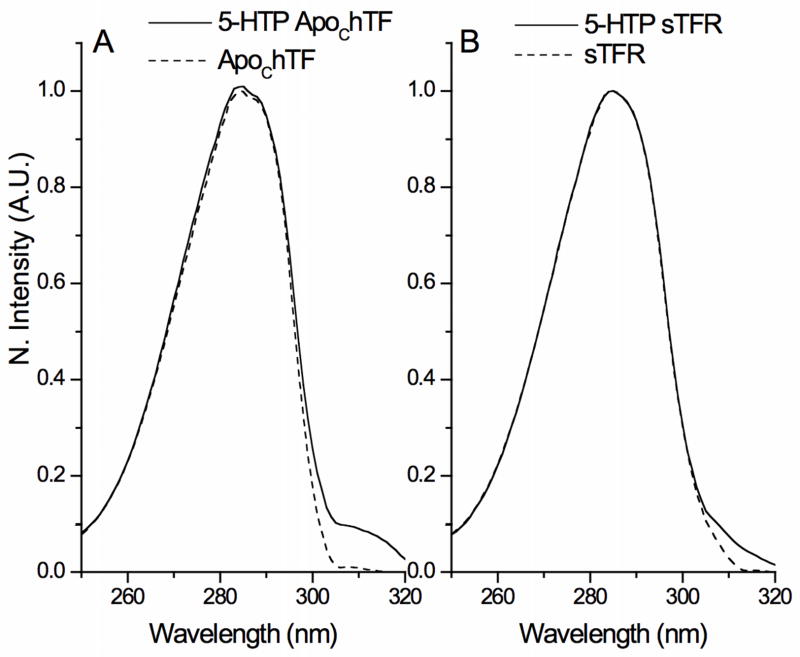

Overlaid excitation spectra for native and 5-HTP apo hTF and for native and 5-HTP sTFR are presented in Fig. 3A and 3B, respectively. The red-shifted excitation spectrum typical of 5-HTP with a peak centered ~315 nm is clearly visible in the spectrum of apo hTF (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the excitation spectrum of native sTFR shows a substantial signal above 300 nm (Fig. 3B) and incorporation of 5-HTP sTFR shows only a modest increase in excitation above 310 nm.

Fig. 3.

Normalized and corrected excitation spectra of native and 5-HTP proteins. A. Apo hTF and B. sTFR in 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 at 25°C.

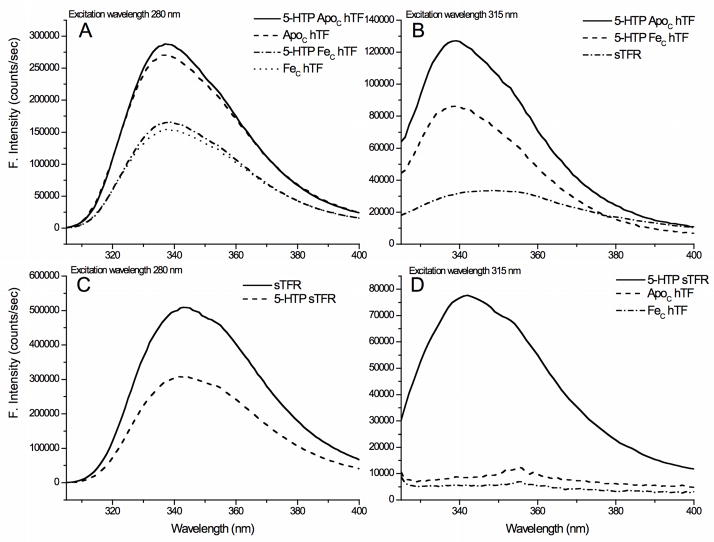

The fluorescence spectra for the various samples excited at 280 and 315 nm are presented in Fig. 4. At 280 nm, both native and 5-HTP FeC hTF have nearly identical emission maxima/intensities (337 nm) and each shows a 75% increase in the fluorescent signal when iron is removed (Fig. 4A). At 315 nm, 5-HTP hTF has a 47% increase in the fluorescent signal when iron is removed. Upon excitation at 315 nm, the intensities of 5-HTP apo and 5-HTP FeC hTF are 4.3 and 2.8 times the intensity of the native sTFR (Fig. 4B), indicating that it should be feasible to selectively monitor iron release from FeC hTF in the kinetic assays. Excitation of 5-HTP sTFR at 280 nm reveals a 1.6 fold decrease in the emission intensity as well as a small blue shift (~ 4 nm) in comparison to native sTFR (Fig. 4C). When excited at 315 nm, 5-HTP sTFR has >7 times the fluorescence intensity of either native apo or FeC hTF (Fig. 4D). Collectively these data indicate that there is a large enough difference between the 5-HTP labeled and native FeC hTF and sTFR to allow selective excitation and emission of the individual proteins in a complex and to assign the source of the increase in the fluorescent signal upon iron release.

Fig. 4.

A. Fluorescence emission spectrum of native and 5-HTP apo hTF and FeC hTF with excitation at 280 nm. B. Fluorescence emission spectrum of 5-HTP apo hTF, FeC hTF, and native sTFR with 315 nm excitation wavelength. C. Fluorescence emission of native and 5-HTP sTFR with excitation at 280 nm. D. Fluorescence emission of native apo hTF, FeC hTF and 5-HTP sTFR with 315 nm excitation wavelength. All emission spectra have been corrected for instrument response.

3.5. The origin of the fluorescent signal change in the FeC hTF/sTFR complex

To dissect the contribution of FeC hTF and sTFR to the increase in fluorescence intensity when bound to each other, we made all possible combinations of native and 5-HTP labeled complexes and then excited the samples at both 280 and 315 nm. Significantly, we observe very similar rate constants for iron release from native and 5-HTP FeC hTF in the absence of sTFR (kobsC1 0.58 versus 0.72 min-1, Table 3). As expected for the control sample containing native FeC hTF and native sTFR, a strong signal is observed when the complex is excited at 280 nm (Fig. 5A-blue curve). Furthermore, 5-HTP FeC hTF in the presence of native sTFR yields an equivalently strong signal (Fig. 5A-black curve). The two complexes containing the 5-HTP sTFR (Fig. 5A-green and red curves) have lower fluorescent changes.

Table 3.

Kinetics of Iron Release from FeC hTF in the absence and presence of the sTFR determined at pH 5.6 (100 mM MES, 4 mM EDTA, 300 mM KCl) at 25°C. Kinetic curves are presented in Fig. 5A and B.

| Protein | kobsC1 (min−1) Ex: 280 nm | kobsC2 (min−1) Ex: 280 nm | kobsC1 (min−1) Ex: 315 nm | kobsC2 (min−1) Ex: 315 nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeC hTF | 0.58 ± 0.08 | Weak signal | ||

| 5-HTP FeC hTF | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | ||

| FeC hTF + sTFR | 21.5 ± 2.6 | 7.7 ± 0.9 | Weak signal | |

| 5-HTP FeC hTF + sTFR | 25.8 ± 3.6 | 8.3 ± 0.9 | 14.1 ± 2.0 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

| FeC hTF + 5-HTP sTFR | 16.9 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 1.3 | Weak signal | |

| 5-HTP FeC hTF + 5-HTP sTFR | 18.1 ± 1.7 | 4.0 ± 1.6 | 22.4 ± 6.2 | 3.4 ± 1.9 |

Fig. 5.

Iron release from native and 5-HTP labeled FeC hTF/sTFR complexes. A. 280 excitation and B. 315 excitation. All samples were assayed in 100 mM MES, pH 5.6 containing 300 mM KCl and 4 mM EDTA. In fitting each curve the small initial drop in the fluorescence intensity was removed.

As previously reported in studies that used a steady-state method to monitor iron release, the single rate constant from the FeC hTF/sTFR complex was enhanced compared to FeC hTF alone [23]. In the current work, use of a more sensitive instrument with stopped flow capability has provided much better kinetic data due to a significant improvement in the signal to noise ratio. In contrast to the previous report [23], in the current work the kinetic curves for the complex fit best to a double-exponential function yielding two rate constants. Significantly, both rate constants are faster than kobsC1 for the FeC hTF alone (Table 3). The important finding is that the rate constants for kobsC1 from all of the complexes are comparable (Table 3); in contrast, kobsC2 for two of the complexes (FeC hTF/5-HTP sTFR and 5-HTP FeC hTF/5-HTP sTFR) show a 2–4 fold decrease. The fact that the fluorescent signal does not convincingly plateau in either of these complexes probably accounts for the difference in the second rate constant.

In terms of dissecting and assigning the change in the fluorescent signal, the crucial experiments are those in which the complexes are excited at 315 nm (Fig. 5B). (Note that in order to increase the signal we needed to use 5-fold higher concentration of sample). The most intense signal comes from the complex of 5-HTP FeC hTF bound to sTFR (Fig. 5B-black curve). The complex with 5-HTP FeC hTF and 5-HTP sTFR also yields a reasonably strong signal (Fig. 5B- red curve). In contrast, the complexes with native FeC hTF bound to either native or 5-HTP labeled sTFR give very low signals (Fig. 5B- blue and green curves). The results of kinetic analysis of the data in Fig. 5A and 5B are presented in Table 3. We obtain similar rate constants for iron release from the various complexes when excited at 280 nm (320 nm cut-on filter) and when excited at 315 nm (335 nm cut-on filter). Again the second rate is more altered than the first.

4. Discussion

Basic tenets of the TF system are that: 1) At neutral pH, diferric and monoferric hTF bind to the TFR with nM affinity, 2) at the low pH within the endosome (pH ~5.6), iron is released and apo hTF remains bound to the TFR with nM affinity and, 3) delivery of iron to cells involves a drop in pH during receptor mediated endocytosis in which the TFR accelerates iron release from the C-lobe as a function of the decrease in pH (with little effect on the rate of iron release from the N-lobe).

An interesting observation, not previously reported, is that there is a 75% decrease in the change in the fluorescence intensity when iron is released from FeC hTF bound to the sTFR relative to the change in fluorescence intensity when iron is released from FeC hTF alone (Fig. 2A and 2B). This decrease may result from the increase in the overall fluorescence contributed by the TFR which might result in a smaller observed change. Alternatively, we suggest that conformational changes in FeC hTF induced by the TFR may lead to lower fluorescence efficiencies from one or more of the Trp residues in FeC hTF from the interaction in the complex. As a result of exposure to pH 5.6, we also report for the first time the fact that the sTFR alone has a small but reproducible drop in the fluorescence intensity followed by an increase and then a gradual decrease (Fig. 2C). As described below, we observe the initial drop in the complex but the other changes are apparently masked when hTF binds to sTFR as indicated by the red curve in Fig 2C. The change in the fluorescence intensity observed upon iron release from FeC hTF alone (Fig. 2A) is attributed to the conformational changes around one or more of the five Trp residues in this lobe and the loss of energy transfer from Trp to the ligand to metal charge transfer band. In the Zuccola structure [42], Trp344 and Trp358 in the CI subdomain lie ~16 and 20 Å from the iron center; in the CII subdomain Trp460 is closest to the iron (~13 Å), while Trp441 and Trp550 are at a distance of 18 and 19 Å, respectively (Fig 1). The reduction in the fluorescence intensity observed when FeC hTF is bound to sTFR (Fig. 2B) is tentatively assigned to the conformational changes that hTF, and probably the sTFR, undergo when bound to each other (see below).

The unexpected changes in the fluorescence intensity for the sTFR alone (Fig. 2C) as a result of lowering the pH to 5.6 obviously cannot be ascribed to iron release. We hypothesize that the initial decrease in the fluorescent signal results from rapid protonation of residues located near Trp residues in the sTFR. Since it is well documented that protonated histidine residues reduce Trp fluorescence by serving as electron-transfer quenchers [34, 35], we examined the crystal structure of sTFR for the presence of His residues in proximity to Trp residues. A single His residue in each of the three domains of the sTFR is close to a Trp-residue: His234 in the apical domain is within 5 Å of Trp357, His699 in the helical domain is 3.4 Å away from Trp702 and His186 in the protease-like domain is 6.5 Å from Trp466. Obviously, the change in pH from 7.4 to 5.6 is more likely to result in the protonation of His residues than any other amino acids.

With regard to the pH-induced increase in the intrinsic fluorescent signal following the initial decrease (Fig. 2C), it is well known that Trp-to-Trp energy transfer can have an effect on the efficiency of Trp fluorescence [36]. Trp residues 182, 453, 466, and 754 are within ~6 Å of each other (Table 1). Additionally Trp641 and Trp740 are 5 Å apart. This proximity means that these two clusters of Trp residues could participate in homo-FRET interactions. Conformational changes as a result of lower pH could change the orientation of one or more of the Trp residues and decrease the efficiency of energy transfer (thereby increasing the intrinsic fluorescence). We also note that increases in the intrinsic fluorescence of Trp can result from changes in the charge transfer state between the Trp ring and the amide backbone [26, 27]. The charge transfer state is very sensitive to the local environment with the rotameric conformation of the Trp residue(s) to the amide backbone and charged side chains near the Trp ring contributing the most. Movement of negatively charged residues away from the indole ring and/or of positively charged residues toward the indole ring both result in an increase in the intrinsic fluorescence of Trp. Specifically, Trp412 in the protease-like domain is 5.4 Å from Glu156 and Trp466 in the same domain is 5 Å from Asp184. Similarly, Trp124 in the protease-like domain is within 4.2 Å of Lys600 and Trp412 is 5.3 Å from Lys193. Since the pH change from 7.4 to 5.6 would not be expected to change the charge of either the negatively or positively charged residues, only a pH induced change in conformation in the region in which they reside would result in an increase in the intrinsic fluorescence.

In the hTF/TFR complex, dynamic movements of each partner are likely to be limited by the strong affinity with which they interact. In order for the C-lobe of hTF (which rotates 54° to open the cleft and release the iron) to remain bound to the sTFR at low pH, one would predict that that there may well be some compensatory movement by the TFR. It is known that the presence of the TFR induces long range conformational changes within the C-lobe of hTF to stabilize the apo form [16]. Specifically, a hydrophobic patch on the TFR (comprising Trp641 and Phe760) interacts with His349 in the C-lobe of hTF to accelerate pH induced iron release [16]. Restrictions in the conformational changes in each could contribute to the lower fluorescence change during iron removal. Weakened iron coordination could lead to some reduction in the quenching of one or more of the five Trp residues in the C-lobe. Another possibility derives from the quantum yield information in Table 2. The interaction of FeC hTF with the sTFR results in a non additive change in the quantum yield for the complex, indicating that Trp residues within each binding partner are quenched by the interaction.

To determine the contributions of each protein to the change in the intrinsic fluorescent signal, we incorporated the Trp analog 5-HTP into FeC hTF and sTFR to allow specific excitation above 300 nm [32]. The most common strategy to incorporate 5-HTP into proteins has been to use a bacterial expression system in combination with Trp auxotrophs and to target a single Trp residue (well summarized in two reviews [24, 37]). The level of incorporation of 5-HTP in the earlier work varied from less than 20% up to ~95% [24]. A mammalian expression system is mandatory to obtain functional (properly folded) hTF because of its 19 disulfide bonds. A single report using mammalian cells (human derived 293T) adopted a unique approach to substitute 5-HTP for the single Trp residue in the T4 fibritin domain [38].

Because BHK cells do not produce endogenous Trp, the sole source of this (and other essential amino acids) is the tissue culture medium. In this regard, the system acts like a “mammalian Trp auxotroph” in which the cells have access only to the substituted amino acid in the medium. The BHK cell system has been used successfully to incorporate 5-fluorotryptophan into the N-lobe of hTF at a level of ~15% [39] and to label hTF with selenomethionine (~89% incorporation) [40]. In the current study we undertook the ambitious goal of labeling both FeC hTF with eight Trp residues (~20% incorporation) and sTFR with 11 residues per monomer (~26% incorporation) with 5-HTP. Although these levels are relatively low, excitation of the various samples at 315 nm demonstrates that the 5-HTP samples provide a selective optical signal (Fig. 4A-D). All possible combinations of labeled and native FeC hTF and sTFR constructs were made. Overall the kinetic data (Fig. 5A and 5B) offer compelling evidence that, with selective excitation, the signal change observed upon lowering the pH is derived solely from the loss of iron from FeC hTF with little or no contribution from sTFR. The rate constants derived from the kinetic curves for loss of iron from FeC hTF alone (whether native or 5-HTP labeled) are within experimental error when excited at 280 nm (Table 3). Additionally the rate constants for the various complexes are also very similar (Table 3). There is a slight decrease in the rate constants (0.55 fold kobsC1 and 0.34 fold kobsC2) for 5-HTP hTF with native sTFR when excited at 280 or 315 nm. We attribute these variations to the differences in the size of the side chain (5-HTP) which is being selectively excited at 315 nm and its unique spectral properties compared to native Trp [41]. These results provide confidence that the incorporation of 5-HTP does not compromise the overall structure and that the source of the intrinsic change in fluorescence is receptor stimulated loss of iron from FeC hTF.

We note that the actual events giving rise to kobsC1 and kobsC2 are currently under investigation. Although we suggest that the faster rate corresponds to pH induced conformational changes within FeC hTF, stimulated by the sTFR, and that the second rate corresponds to actual iron release, more experiments are required to confirm this suggestion. The important finding is that the rates for all of the complexes (regardless of their source) are similar. Additionally, although the enhancement is lower than previously reported [16], the difference is explained by the fact that the quality of the data is much improved by use a stopped flow instrument.

In summary, our results allow us to conclude that when FeC hTF is bound to the sTFR the increase in the fluorescence intensity that we observe for the sTFR alone in response to lowering the pH is abolished (Fig. 2C and 5B). We report for the first time the quenching of the intrinsic fluorescent signal when FeC hTF is bound to the sTFR and the observation of a pH-induced small initial decrease in the signal assigned to the sTFR. We and others can now pursue studies to characterize the interaction of hTF and the sTFR as a function of pH and salt concentration with confidence that we are measuring rate constant(s) from hTF.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by USPHS Grant R01 (DK 21739) to A.B.M. Support for N.G.J and S.L.B came from Hemostasis and Thrombosis Training Grant (5T32HL007594), issued to Dr. K. G. Mann at The University of Vermont by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

The abbreviations used are

- hTF

human serum transferrin

- Fe2 hTF

diferric human serum transferrin

- apo hTF

human serum transferrin lacking iron

- FeC hTF

recombinant monoferric hTF with iron in the C-lobe, (Y95F/Y188F mutations preclude binding in the N-lobe), which has an N-terminal hexa His tag and is non-glycosylated

- TFR

transferrin receptor

- sTFR

soluble portion of the transferrin receptor expressed as a recombinant entity

- 5-HTP

L-5-hydroxytryptophan

- DMEM-F12

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium-Ham F-12 nutrient mixture

- BA

butyric acid

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- UG

Ultroser G a serum substitute

- GdHCl

guanidine HCl

- BHK cells

baby hamster kidney cells

Footnotes

The results were presented by NGJ as a poster at the 7th International Weber Symposium on Innovative Fluorescence Methodologies in Biochemistry and Medicine in Kauai, HI, June 6–12, 2008.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aisen P, Enns C, Wessling-Resnick M. Chemistry and biology of eukaryotic iron metabolism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:940–959. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason AB, Halbrooks PJ, James NG, Connolly SA, Larouche JR, Smith VC, MacGillivray RTA, Chasteen ND. Mutational analysis of C-lobe ligands of human serum transferrin:insights into the mechanism of iron release. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8013–8021. doi: 10.1021/bi050015f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams J, Moreton K. The distribution of iron between the metal-binding sites of transferrin in human serum. Biochem J. 1980;185:483–488. doi: 10.1042/bj1850483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klausner RD, Ashwell G, van Renswoude J, Harford JB, Bridges KR. Binding of apotransferrin to K562 cells: explanation of the transferrin cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:2263–2266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patch MG, Carrano CJ. The origin of the visible absorption in metal transferrins. Inorg Chim Acta. 1981;56:L71–L73. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehrer SS. Fluorescence and absorption studies of the binding of copper and iron to transferrin. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:3613–3617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He QY, Mason AB, Templeton DM. Molecular aspects of release of iron from transferrins, Molecular and Cellular Iron Transport. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York: 2002. pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mason AB, Halbrooks PJ, Larouche JR, Briggs SK, Moffett ML, Ramsey JE, Connolly SA, Smith VC, MacGillivray RTA. Expression, purification, and characterization of authentic monoferric and apo-human serum transferrins. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;36:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James NG, Berger CL, Byrne SL, Smith VC, MacGillivray RTA, Mason AB. Intrinsic fluorescence reports a global conformational change in the N-lobe of human serum transferrin following iron release. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10603–10611. doi: 10.1021/bi602425c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egan TJ, Zak O, Aisen P. The anion requirement for iron release from transferrin is preserved in the receptor-transferrin complex. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8162–8167. doi: 10.1021/bi00083a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turkewitz AP, Schwartz AL, Harrison SC. A pH-dependent reversible conformational transition of the human transferrin receptor leads to self-association. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:16309–16315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bali PK, Aisen P. Receptor-modulated iron release from transferrin: Differential effects on N- and C-terminal sites. Biochemistry. 1991;30:9947–9952. doi: 10.1021/bi00105a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bali PK, Zak O, Aisen P. A new role for the transferrin receptor in the release of iron from transferrin. Biochemistry. 1991;30:324–328. doi: 10.1021/bi00216a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aisen P. Entry of iron into cells: A new role for the transferrin receptor in modulating iron release from transferrin. Ann Neurol. 1992;32(Suppl):S62–S68. doi: 10.1002/ana.410320711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halbrooks PJ, He QY, Briggs SK, Everse SJ, Smith VC, MacGillivray RTA, Mason AB. Investigation of the mechanism of iron release from the C-lobe of human serum transferrin: Mutational analysis of the role of a pH sensitive triad. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3701–3707. doi: 10.1021/bi027071q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giannetti AM, Halbrooks PJ, Mason AB, Vogt TM, Enns CA, Bjorkman PJ. The molecular mechanism for receptor-stimulated iron release from the plasma iron transport protein transferrin. Structure. 2005;13:1613–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrne SL, Leverence R, Klein JS, Giannetti AM, Smith VC, MacGillivray RTA, Kaltashov IA, Mason AB. Effect of glycosylation on the function of a soluble, recombinant form of the transferrin receptor. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6663–6673. doi: 10.1021/bi0600695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett MJ, Lebron JA, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure of the hereditary haemochromatosis protein HFE complexed with transferrin receptor. Nature. 2000;403:46–53. doi: 10.1038/47417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zak O, Aisen P. Iron release from transferrin, its C-lobe, and their complexes with transferrin receptor: Presence of N-lobe accelerates release from C-lobe at endosomal pH. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12330–12334. doi: 10.1021/bi034991f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Andrews NC. Balancing acts: molecular control of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2004;117:285–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrence CM, Ray S, Babyonyshev M, Galluser R, Borhani DW, Harrison SC. Crystal structure of the ectodomain of human transferrin receptor. Science. 1999;286:779–782. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng Y, Zak O, Aisen P, Harrison SC, Walz T. Structure of the human transferrin receptor-transferrin complex. Cell. 2004;116:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannetti AM, Snow PM, Zak O, Bjorkman PJ. Mechanism for Multiple Ligand Recognition by the Human Transferrin Receptor. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:341–350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross JB, Szabo AG, Hogue CW. Enhancement of protein spectra with tryptophan analogs: fluorescence spectroscopy of protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1997;278:151–190. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)78010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valeur B, Weber G. Resolution of the fluorescence excitation spectrum of indole into the 1La and 1Lb excitation bands. Photochem Photobiol. 1977;25:441–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1977.tb09168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callis PR. 1La and 1Lb transitions of tryptophan: applications of theory and experimental observations to fluorescence of proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1997;278:113–150. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)78009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Callis PR, Liu T. Quantitative prediction of fluorescence quantum yields for tryptophan in proteins, Journal of Physical Chemistry B-Materials, Surfaces. Interfaces & Biophysical. 2004;108:4248–4259. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong CY, Eftink MR. Biosynthetic incorporation of tryptophan analogues into staphylococcal nuclease: effect of 5-hydroxytryptophan and 7-azatryptophan on structure and stability. Protein Sci. 1997;6:689–697. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogue CW, Rasquinha I, Szabo AG, MacManus JP. A new intrinsic fluorescent probe for proteins. Biosynthetic incorporation of 5-hydroxytryptophan into oncomodulin. FEBS Lett. 1992;310:269–272. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81346-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason AB, He QY, Halbrooks PJ, Everse SJ, Gumerov DR, Kaltashov IA, Smith VC, Hewitt J, MacGillivray RTA. Differential effect of a His tag at the N-and C-termini: Functional studies with recombinant human serum transferrin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9448–9454. doi: 10.1021/bi025927l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mason AB, He QY, Adams TE, Gumerov DR, Kaltashov IA, Nguyen V, MacGillivray RTA. Expression, purification, and characterization of recombinant nonglycosylated human serum transferrin containing a C-terminal hexahistidine tag. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;23:142–150. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3. Springer; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fortes de Valencia F, Paulucci AA, Quaggio RB, Rasera da Silva AC, Farah CS, de Castro Reinach F. Parallel Measurement of Ca2+ Binding and Fluorescence Emission upon Ca2+ Titration of Recombinant Skeletal Muscle Troponin C. Measurement of Sequential calcium binding to the regulatory sites. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11007–11014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Liu B, Yu HT, Barkley MD. The Peptide Bond Quenches Indole Fluorescence. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:9271–9278. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, Barkley MD. Toward understanding tryptophan fluorescence in proteins. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9976–9982. doi: 10.1021/bi980274n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moens PD, Helms MK, Jameson DM. Detection of tryptophan to tryptophan energy transfer in proteins. The Protein Journal. 2004;23:79–83. doi: 10.1023/b:jopc.0000016261.97474.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Correa F, Farah CS. Using 5-hydroxytryptophan as a probe to follow protein-protein interactions and protein folding transitions. Protein and Peptide Letters. 2005;12:241–244. doi: 10.2174/0929866053587057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z, Alfonta L, Tian F, Bursulaya B, Uryu S, King DS, Schultz PG. Selective incorporation of 5-hydroxytryptophan into proteins in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8882–8887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307029101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luck LA, Mason AB, Savage KJ, MacGillivray RTA, Woodworth RC. 19 F NMR Studies of the Recombinant Human Transferrin N -Lobe and Three Single Point Mutants. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry. 1997;35:477–481. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wally J, Halbrooks PJ, Vonrhein C, Rould MA, Everse SJ, Mason AB, Buchanan SK. The crystal structure of iron-free human serum transferrin provides insight into inter-lobe communication and receptor binding. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24934–24944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604592200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Twine SM, Szabo AG. Fluorescent amino acid analogs. Methods Enzymol. 2003;360:104–127. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)60108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuccola HJ. The crystal structure of monoferric human serum transferrin. Georgia Institute of Technology; Atlanta, GA: 1993. [Google Scholar]