Summary

Background:

In East Africa, visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is endemic in parts of Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya and Uganda. It is caused by Leishmania donovani and transmitted by the sandfly vector Phlebotomus martini. In the Pokot focus, reaching from western Kenya into eastern Uganda, formulation of a prevention strategy has been hindered by the lack of knowledge on VL risk factors as well as by lack of support from health sector donors. The present study was conducted to establish the necessary evidence-base and to stimulate interest in supporting the control of this neglected tropical disease in Uganda and Kenya.

Methods:

A case-control study was carried out from June to December 2006. Cases were recruited at Amudat hospital, Nakapiripirit district, Uganda, after clinical and parasitological confirmation of symptomatic VL infection. Controls were individuals that tested negative using a rK39 antigen-based dipstick, which were recruited at random from the same communities as the cases. Data were analysed using conditional logistic regression.

Results:

93 cases and 226 controls were recruited into the study. Multivariate analysis identified low socio-economic status and treating livestock with insecticide as risk factors for VL. Sleeping near animals, owning a mosquito net and knowing about VL symptoms were associated with a reduced risk of VL.

Conclusions:

VL affects the poorest of the poor of the Pokot tribe. Distribution of insecticide-treated mosquito nets combined with dissemination of culturally appropriate behaviour-change education is likely to be an effective prevention strategy.

Keywords: Visceral leishmaniasis, risk factors, Uganda, Kenya, case-control study, prevention

Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a chronic, systemic disease characterized by fever, (hepato)splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, pancytopenia, weight loss, weakness and, if left untreated, death. The disease is usually caused by Leishmania donovani or L. infantum, protozoan parasites transmitted to human and animal hosts by the bite of phlebotomine sandflies.1

East Africa is one of the world's main endemic areas for VL, which over the last 20 years has seen a dramatic increase in the number of VL cases, due to a complexity of factors.2 Several studies have convincingly shown that malnutrition, HIV and genetic susceptibility are individual risk factors for VL.3,4 However, data on socio-economic, behavioural and entomological risk factors for VL are comparatively scarce, and in East Africa, no study, to our knowledge, has investigated risk factors for VL. This severely hampers efforts to prevent and control the disease in the region. To fill this knowledge gap, we carried out a case-control study to identify individual and household level risk factors for VL in an endemic focus in eastern Uganda/north-western Kenya.

Materials and methods

Study area

The study was conducted in Pokot territory, an area of roughly 100 by 30 kilometres, covering West Pokot District, north-western Kenya, and Pokot County in Nakapiripirit District, eastern Uganda. The area is situated in the lowlands (<1800 m) of the Rift Valley. There are 384,760 inhabitants registered in West Pokot district and 74,641 in Pokot County5; the majority of which are Pokot pastoralists. People live in compounds (manyattas), surrounded by a thick fence of Acacia branches, that contain several family households. Most households keep domestic animals that are usually kept in corrals near family houses.

The population is provided with health care by three hospitals (Amudat in Uganda, and Kapenguria and Ortum in Kenya) and a number of smaller health posts. Since 2000, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, Swiss Section) has provided free VL diagnosis and treatment at Amudat hospital. No other reliable diagnostic or treatment facility was available in the region until November 2006 when MSF started activities at Kacheliba health centre, Kenya. A recent KAP study in the study area indicated that 95% of individuals had heard of VL, known locally as ‘termes’, meaning enlarged spleen.6 Most individuals regarded VL as a potentially fatal disease, were aware of its main clinical signs and knew that drug treatment is available and effective. VL in Pokot territory is caused by L. donovani and infection is transmitted by the sandfly Phlebotomus martini,7 one of the main vectors of VL in East Africa. 8,9,10

Case definition and recruitment

Cases were individuals that reported to the out-patients department of Amudat hospital with suspected clinical VL, i.e. a history of prolonged fever (2 weeks or more) associated with clinical splenomegaly or wasting, that was subsequently confirmed using a rK39 antigen-based dipstick (IT-Leish, DiaMed AG, Switzerland). In Uganda, this dipstick has high sensitivity and specificity.11 Because VL treatment is provided free of charge by MSF and awareness of VL among the local population is apparently high,12 many individuals with symptoms of VL present voluntarily at the outpatients department. For logistical reasons, only cases living in communities within 80 km from Amudat town were included in the analysis. Confirmed cases were admitted to the VL ward and treated with daily intramuscular injections of meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime®, Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France) at 20 mg/kg per day for 30 days according to standard MSF treatment protocol.13

Controls were individuals who had been selected at random from the same communities as the cases. Two controls were matched according to village and frequency-matched according to age group (<5, 5-14, 15-24, 25-40 and 40+ years) and sex to every case. In each community, households were randomly sampled along perpendicular transects with the survey team starting from a central point, randomly selecting the direction by spinning a bottle. When walking along transects, the first household encountered was selected and the household head invited to participate. In Amudat town, every fifth household encountered was selected. If houses were empty or potential controls absent at the time of the visit, an appointment was made for a return visit. A list of family members was made and one individual was randomly selected from the list by rolling a die. If the individual had no signs or recent history of VL, a dipstick test was conducted. If individuals were dipstick-positive, another household member was randomly selected and tested. Household visits were repeated until the required number of controls in each village was recruited.

Among both cases and controls, a rapid diagnostic test for malaria was performed using the Paracheck Pf test (Orchid Biomedical Systems, Goa, India) for the presence of Plasmodium falciparum. In Uganda, this test has a sensitivity and specificity >98%.14 Haemoglobin concentration (Hb) was estimated to an accuracy of 1 g/L using a portable haemoglobinometer (Hemocue Ltd, Sheffield, UK). Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using an electronic balance (Soehnle, Leifheit AG, Nassau, Germany) and height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Leicester Height Measure, Child Growth Foundation, London, UK).

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Uganda National Council of Science and from the ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK. Individuals were informed of the study's purpose and methodology and were made aware that participation was voluntary and that they were able to withdraw from the study at any time. For study subjects, consent was obtained from all adult subjects and from parents or guardians of children by use of a written consent form; ascent was obtained from children.

Household surveys

A pre-tested standardized household questionnaire was administered to each case or their guardian at Amudat hospital. Cases were accompanied home by a surveyor to verify the accuracy of the information provided in the questionnaire. All controls were interviewed at home. For young children included in the study it was common that a parent or guardian responded to the majority of questions. The questionnaire recorded details on socioeconomic characteristics, including ownership of selected household assets, animal ownership and household construction. Information was also collected on knowledge of VL and the behaviour of subjects. In this context we defined ‘sleeping near animals’ as being within 5 – 15 metres from livestock kept outdoors within the confines of the manyatta. The list of household assets and indicators were selected based on published literature and discussions with key local informants.

Data analysis

Anthropometric indices were calculated using Anthro 1.02 software (CDC, Atlanta, GA, U.S.A.), which uses the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reference values.15 Three anthropometric indices - height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-age (WAZ) and weight-for-height (WHZ) - were expressed as differences from the median in standard deviation units or z-scores. Individuals were classified as stunted, underweight and wasted if HAZ, WAZ and WHZ were more than 2 standard deviations (s.d.) below the NCHS median respectively. Anaemia was defined as a haemoglobin level <130 g/L for men, <120 g/L for non-pregnant women, <120 g/L for children aged 12-13 years, <115 g/L for children aged 5-11 years and <110 g/L for children aged less than five years. 16 Severe anaemia was defined as a haemoglobin level <70g/L.

Information on ownership of household assets was used to construct a socio-economic status (SES) index using the method of Filmer & Pritchett,17 which has been shown to reliably measure economic status without the necessity of direct income or expenditure information. Principal component analysis was used to determine the weights for an index of asset variables in order to calculate the SES index for each household. The resultant SES index was divided into quintiles, so that each household could be stratified into five socio-economic groups.17

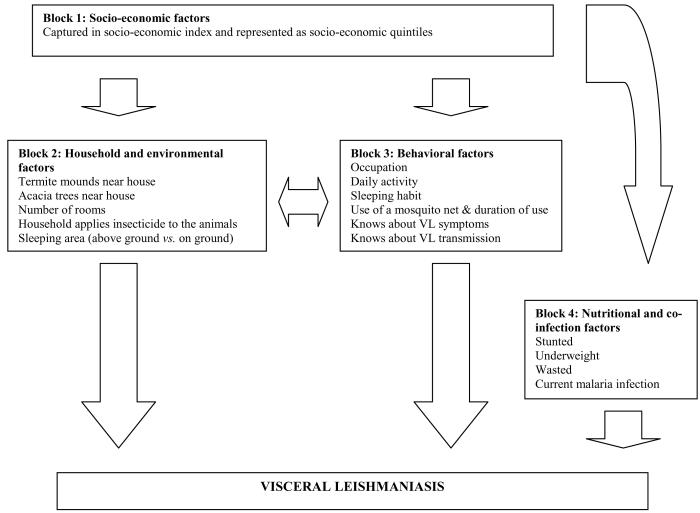

Univariate analysis of all risk factors was conducted using conditional logistic regression adjusting for age group and sex, with controls being matched to cases by village. Associations are shown as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. Variables with a P value of < 0.1 in the univariate analyses were included in a conditional logistic regression model for multivariate analysis adjusting for age group and sex, and matching by village. For our analysis we adopted a conceptual framework which takes account of the hierarchical relationships between biological, social and environmental risk factors.18 Figure 1 presents our conceptual framework whereby variables at the top influence the variables below them and comprises four blocks: i) socio-economic factors; ii) household and environmental factors; iii) behavioural factors; and iv) nutritional and co-infection factors. Socio-economic factors affect a number of household and environmental factors, including crowding, household location, as well as affecting a number of behavioural factors, such as sleeping patterns and mosquito net usage. All of these factors affect host-sandfly contact. Socio-economic factors also affect nutritional status, which in turn affects disease susceptibility. In addition, household and environmental factors may exert their effect through behavioural factors; for example household crowding may influence sleeping habits. In the multivariable analysis, socio-economic status (defined by the SES index) was first included in the model and subsequently adjusted for statistically significant variables of the remaining blocks. A backward elimination process was conducted for each block and only significant variables were carried forward to the next block. Thus, the final model presents the variables significant in each block. Likelihood ratio tests were used to assess for interaction between variables. Colinearity was verified by Spearman correlation among covariates and a correlation coefficient of < 0.7 was considered important. On this basis, there was no evidence of colinearity. Variables with missing data were very few (<2%), but where data were missing, the case-control pairs affected were removed. All analyses were done in STATA 9.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA)

Figure 1.

Framework for socio-economic, household/environmental, behavioral and nutritional/co-infection variables and being infected with visceral leishmaniasis in the Pokot county, East Africa. This approach distinguishes between distal and proximate factors: distal factors rarely have a direct effect on disease outcomes but operate through a number of inter-related proximate determinants which in turn affects directly risk of disease. For example, socio-economic status does not affect directly the risk of VL but may affect VL indirectly through, for example, (i) the likelihood of sleeping outdoors or ownership of bed net, both of which influence in turn the risk of exposure to biting by sandflies or (ii) individual nutritional status which influences susceptibility to disease.

Note: Cases were matched to controls by village; sex and age were controlled for in the analysis. These demographic factors are thus not included in the above analysis framework.

Results

A total of 93 cases from Amudat hospital and 226 community controls were recruited between June and September 2006. All of the cases and all but three of the controls belonged to the Pokot tribe. The median age of cases was 11 years (Inter-quartile range: 8-16) and 59.1% were male. The majority (56.3%) of adult cases (≥15 years) were pastoralists, came from Kenya (75.0%) and had lived in their community for two years or more (78.1%). Cases were from the arid lowlands (elevation <1800 m) of the region, running north-south along the Rift Valley. The nutritional status of cases was extremely poor: 51.6% of all cases were severely anaemic and 48.4% were moderately anaemic; among children, 23.9% were classified as stunted, 50.0% were underweight and 20.5% wasted (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association between visceral leishmaniasis and between socioeconomic, household/environmental, behavioral and nutritional/co-infection variables1 in the Pokot county, East Africa.

| Factors | Category | Prevalence of risk factor |

Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

Case |

|||||

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

|

Socio-economic status index of household | ||||||

| First quintile (poorest) | 32 | 14.2 | 31 | 34.8 | 1 | |

| Second quintile | 43 | 19.1 | 20 | 22.5 | 0.40 (0.18 – 0.90) | |

| Third quintile | 45 | 20.0 | 17 | 19.1 | 0.26 (0.11 – 0.62) | |

| Fourth quintile | 46 | 20.4 | 14 | 15.7 | 0.19 (0.08 – 0.46) | |

| Fifth quintile (least poor) | 59 | 26.2 | 7 | 7.9 | 0.08 (0.03 – 0.23) | |

|

Household and environmental factors | ||||||

| Termite hill near house | No | 28 | 12.4 | 4 | 4.3 | 1 |

| Yes | 198 | 87.6 | 89 | 95.7 | 2.06 (0.68 – 6.23) | |

| Acacia tree near house | No | 40 | 17.7 | 17 | 18.3 | 1 |

| Yes | 186 | 82.3 | 76 | 81.7 | 0.85 (0.39 – 1.83) | |

| Number of rooms | 1 | 183 | 81.0 | 89 | 95.7 | 1 |

| > 1 | 43 | 19.0 | 4 | 4.3 | 0.16 (0.05 – 0.48) | |

| Household applies insecticide to livestock |

No | 105 | 54.7 | 33 | 37.5 | 1 |

| Yes | 87 | 45.3 | 55 | 62.5 | 2.10 (1.17 – 3.80) | |

| Type of sleeping area | Bed | 157 | 69.5 | 57 | 61.3 | 1 |

| Ground | 64 | 28.3 | 29 | 31.2 | 1.32 (0.74 – 2.33) | |

| Changes depending on season | 5 | 2.2 | 7 | 7.5 | 4.38 (1.24 – 15.49) | |

| Sleeps near animals | No | 40 | 17.7 | 18 | 19.4 | 1 |

| Yes | 186 | 82.3 | 75 | 80.6 | 0.10 (0.51 – 1.95) | |

| Behavioural factors | ||||||

| Occupation | Pastoralist | 96 | 42.5 | 40 | 43.0 | 1 |

| Farmer | 29 | 12.8 | 13 | 14.0 | 1.38 (0.58 – 3.28) | |

| Too young to have a specific occupation or going to school |

94 | 41.6 | 37 | 39.8 | 0.76 (0.39 – 1.49) | |

| Other occupations2 | 7 | 3.1 | 3 | 3.2 | 1.18 (0.27 – 5.19) | |

| Daily activity | Herding animals | 69 | 30.5 | 32 | 34.4 | 1 |

| Watering animals | 26 | 11.5 | 6 | 6.5 | 0.59 (0.17 – 2.00) | |

| Housework/digging | 32 | 14.2 | 20 | 21.5 | 1.68 (0.66 – 4.28) | |

| Going to school/playing | 90 | 39.8 | 35 | 37.6 | 0.82 (0.40 – 1.67) | |

| Teaching or business activity | 9 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Sleeping habit | Sleeps indoors all of the year | 196 | 86.7 | 65 | 69.9 | 1 |

| Sleeps outside during some months |

8 | 3.5 | 10 | 10.8 | 4.75 (1.65 – 13.67) | |

| Sleeps outside all of the year | 22 | 9.7 | 18 | 19.4 | 3.69 (1.67 – 8.19) | |

| Has a mosquito net | No | 125 | 55.3 | 74 | 79.6 | 1 |

| Yes | 101 | 44.7 | 19 | 20.4 | 0.18 (0.09 – 0.37) | |

| Knows VL symptoms | No | 169 | 74.8 | 80 | 86.0 | 1 |

| Yes | 57 | 25.2 | 13 | 14.0 | 0.41 (0.19 – 0.86) | |

| Knows about VL transmission |

No | 216 | 95.6 | 91 | 97.9 | 1 |

| Yes | 10 | 4.4 | 2 | 2.1 | 0.50 (0.11 – 2.36) | |

| Nutritional and co-infection factors | ||||||

| Stunted3 | No | 91 | 61.1 | 54 | 76.1 | 1 |

| Yes | 58 | 38.9 | 17 | 23.9 | 0.39 (0.19 – 0.81) | |

| Underweight3 | No | 75 | 50.3 | 35 | 50.0 | 1 |

| Yes | 74 | 49.7 | 35 | 50.0 | 0.79 (0.43 – 1.47) | |

| Wasted3 | No | 55 | 78.6 | 31 | 79.5 | 1 |

| Yes | 15 | 21.4 | 8 | 20.5 | 0.67 (0.20 – 2.24) | |

| Malaria | Negative | 188 | 83.6 | 87 | 93.6 | 1 |

| Positive | 37 | 16.4 | 6 | 6.4 | 0.26 (0.09 – 0.72) | |

A number of factors originally included in the questionnaire were equally common among cases and controls and were thus not included in the analysis: i) sharing the sleeping areas with other people, ii) having had a VL case in the household; iii) having suffered from other diseases in the last year; iv) whether the head of household was alive; v) the number of household members; vi) whether or not the household was part of a manyatta (traditional compound); vii) whether the manyatta was shared with other families; viii) the number of openings (doors and windows) of the dwelling; and ix) whether the household kept animals. Also, almost none of the respondents reported the use of any methods of protection from insect bites apart from mosquito nets.

Businessman, driver, teacher

The anthropometric indices - height-for-age (stunted) weight-for-age (underweight) and weight-for-height (wasted) - were expressed as differences from the median of U.S. National Center for Health Statistics reference values in standard deviation units or z-scores.

Of the cases, 26.9%, 40.9% and 20.4% reported that they had noticed signs of VL one, two or three months before reporting to Amudat hospital, respectively. The other cases (11.8%) had waited >3 months to report for diagnosis and treatment at the hospital. 47.3% of patients stated that they had consulted a traditional healer prior to this and been treated with herbs. A small proportion (8.6%) of cases had gone to a pharmacy or attempted treatment at home, with medication such as paracetamol or antimalarials.

Table 1 summarizes the univariate analysis of the association between each of the main risk factors and VL, and demonstrates that low socio-economic status, as defined by our SES index, was a risk factor for VL. Two out of six variables in the household and environmental block were also identified as risk factors: whether households occupied only one room or whether they applied insecticide to their domestic animals. In the behavioural block, sleeping outside during some or all of the year was associated with an increased risk of VL. In the same block, having a mosquito net and knowing the signs and symptoms of VL were associated with a protective effect. In the nutritional and co-infection block, being stunted or infected with P. falciparum were identified as risk factors.

The multivariate analysis demonstrates that four variables were associated with an altered risk of VL after adjusting for age group and sex (Table 2). Application of insecticide to livestock was the most important risk factor for VL, with estimated odds ratios of 4.06 (95% CI: 1.96 – 8.41). Socio-economic status and sleeping near animals were negatively associated with VL risk. Knowing about the symptoms of VL and having a mosquito net were also associated with a decreased risk of VL. We found no strong evidence of interaction/effect modification between variables as indicated by the likelihood ratio tests.

Table 2.

Results from multivariable conditional logistic regression model of the odds ratios, together with 95% confidence intervals, for the risk of visceral leishmaniasis

| Variable | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Socio-economic status | ||

| First quintile (poorest) | 1 | |

| Second quintile | 0.36 (0.14 – 0.94) | |

| Third quintile | 0.19 (0.06 – 0.58) | |

| Fourth quintile | 0.12 (0.04 – 0.39) | |

| Fifth quintile (least poor) | 0.17 (0.05 – 0.65) | |

| Sleeps near animals | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.22 (0.06 – 0.58) | |

| Household applies insecticide to livestock |

||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 4.06 (1.96 – 8.41) | |

| Knows VL symptoms | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.29 (0.11 – 0.76) | |

| Has a mosquito net | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.39 (0.16 – 0.95) | |

Discussion

The age and sex distribution of our cases were representative of the cases treated in Amudat hospital from 2000 through 2004:19 14.0% below five years of age; 51.6% aged 5-14 years; 34.4% aged 15 years and over; and 59.1% males. The age distribution is also similar to other epidemiological studies conducted in East Africa 3, 20-23 A smaller proportion of cases came from Uganda than was treated by MSF over the last years (18.3% vs. 30.3%).

Our study highlights the burden of VL in local communities: we dramatically show that VL is a disease of the poorest of the poor,24 with decreasing socio-economic status associated with an increased risk of VL. Our findings complement observations in India and Nepal where VL risk was associated with illiteracy 25 and whether household heads were labourers;26 other studies, however, found no association between VL risk and individual socio-economic factors (e.g. ownership of land, radio or bicycle, electricity).27-30 As reported from other VL-endemic areas 31,32 it is probable that VL in Pokot territory is also poverty promoting because patients and their families are significantly impacted by the disease through productivity losses due to hospitalization.

We demonstrate that VL risk in Pokot territory is dependent on increased potential exposure to the sandfly vector. Evidence for indoor transmission comes from the decreased risk for persons inhabiting households that have more than one room or for persons that own a mosquito net, both representing a physical barrier that reduces the probability of sandflies' encountering a human blood meal. Termite mounds and acacia forests have anecdotally been associated with VL,10,33-36 because they provide ideal conditions for sandflies to prosper and breed.10,37,38 In our study proximity of termite mounds and acacia trees were not associated with increased risk of VL, probably because both were extremely common throughout affected communities (Table 1).

Studies in Nepal demonstrated that cattle and buffalo ownership significantly reduced VL risk,26 hinting that these may have a zooprophylactic effect due to their importance as a sandfly feeding source. Confirming these findings we show that sleeping in a manyatta where animals were kept was found to be protective (Table 2). It also confirms entomological data that suggests that P. martini is zoophilic rather than anthropophilic (i.e. feeding on animals rather than humans), with goats probably providing the preferred source of bloodmeals.9,39 Interestingly, our findings reveal that household insecticide application on animals increased the risk of VL in Pokot territory, indicating that sandflies potentially shift their host-seeking behaviour. Insecticide application may not kill sandflies attempting to feed on animals, but could be acting as a repellent that forces them to feed on hosts not treated with an insecticide, such as humans. Though we are not aware of any study reporting such behaviour in phlebotomine sandflies, studies evaluating the protective efficacy of insecticide-treated nets on malaria incidence have reported shifts in host feeding patterns amongst Anopheles mosquitoes.40

A finding that is in contrast to previous data 12 is that knowledge about VL symptoms and transmission was poor, with only 21.9% and 3.8% of surveyed individuals responding affirmatively, respectively (Table 1). Those individuals that did say they knew about VL symptoms, however, had a decreased risk of VL. It might be assumed that people who know of the severity and potential impact of VL will use protective measures. We found strong evidence for this in our study population, where 52.9% of people who knew about VL symptoms owned a net, compared to only 33.3% of people that did not know the symptoms (χ2=8.87, p=0.003).

There are potentially a number of caveats in our analyses. First, it was logistically not feasible to test all control household members for Leishmania infection. If asymptomatic individuals are infectious to the sandfly vector, this may dilute the effect of an association between any of the risk factors investigated and VL. However, to date no evidence exists demonstrating that individuals with asymptomatic L. donovani infection are infectious to sandflies nor do we actually know whether transmission in the Pokot territory is anthroponotic (i.e. humans are the main reservoir host). Second, the difficult field conditions meant that, besides malnutrition, we were unable to assess host genetics and immunosupression (e.g. HIV), known VL risk factors. Third, some of the factors investigated may be a proxy indicator for poverty in our study population (e.g. presence of animals, occupation) and, hence, may be confounded by poverty/SES; the number of regression analyses that were carried out will also have increased the odds of finding a significant association between poverty proxies and VL. However, we do not believe that there was significant confounding, because we consistently showed that the overall socio-economic status was associated with greater risk of disease.

Conclusion

Here we report the findings of the first case-control study of VL to be conducted in Africa. Our findings clearly indicate that low socio-economic status and application of insecticide to livestock are the major risk factors for VL in the Pokot tribe of eastern Uganda and western Kenya. In turn, sleeping in a compound with animals, knowing about VL symptoms and owning a mosquito net reduce the likelihood of being infected. Knowledge of the signs and transmission of VL seems to be considerably lower than previously thought. Based on our findings, a prevention and control strategy should be implemented that aims at high coverage with and usage of long-lasting insecticide treated nets (LLINs) and early reporting of all symptomatic cases to Kacheliba health centre. This will require commitment from health sector donors to finance the procurement of LLINs, their distribution, as well as the development and implementation of culturally appropriate behaviour-change education activities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Caryn Bern (Centre of Disease Control and Prevention) and Patrice Piola (Epicentre) for sharing their case-report forms with us. We also thank the study participants and the staff of MSF and Amudat hospital. We are very grateful to Dr Graham Root and staff of the Malaria Consortium Africa for their invaluable support to this study. Advice on data analysis was kindly provided by Peter Smith and Simon Cousins (LSHTM). This project was supported financially by the Sir Halley Stewart Trust. SB is supported by a Wellcome Trust Advanced Training Fellowship (073656).

References

- 1.Davies C, Kaye P, Croft S, Sundar S. Leishmaniasis: new approaches to disease control. BMJ. 2003;326:377–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7385.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reithinger R, Brooker S, Kolaczinski J. Visceral leishmaniasis in eastern Africa – current status. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.06.001. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucheton B, Kheir MM, El-Safi SH, et al. The interplay between environmental and host factors during an outbreak of visceral leishmaniasis in eastern Sudan. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:1449–57. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohamed HS, Ibrahim ME, Miller EN, et al. SLC11A1 (formerly NRAMP1) and susceptibility to visceral leishmaniasis in The Sudan. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:66–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of District Medical Officer of Health . Pokot County - Final report on meninigitis outbreak Nakapiripirit district. Office of District Medical Officer of Health; West Pokot: Mar, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Médecins sans Frontières . Perception of kala azar among Pokot communities in Amudat, Uganda. Final Report by Epicentre and MSF Switzerland; Apr, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson J. Kala-azar Entomology Study. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; London, U.K.: 2004. Masters Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gebre-Michael T, Lane RP. The roles of Phlebotomus martini and P. celiae (Diptera: Phlebotominae) as vectors of visceral leishmaniasis in the Aba Roba focus, southern Ethiopia. Med Vet Entomol. 1996;10:53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1996.tb00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perkins PV, Githure JI, Mebrahtu Y, Kiilu G, Anjili C, Ngumbi PS, Nzovu J, Oster CN, Whitmire RE, Leeuwenburg J, et al. Isolation of Leishmania donovani from Phlebotomus martini in Baringo district, Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1988;82:695–700. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(88)90204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robert LL, Schaefer KU, Johnson RN. Phlebotomine sandflies associated with households of human visceral leishmaniasis cases in Baringo District, Kenya. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;88:649–57. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1994.11812917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chappuis F, Mueller Y, Nuimfack A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of two rK39 antigen-based dipsticks and the Formol Gel test for the rapid diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in northeastern Uganda. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5973–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.5973-5977.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Médecins sans Frontières . Perception of kala azar among Pokot communities in Amudat, Uganda. Final Report by Epicentre and MSF Switzerland; Apr, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Médecins sans Frontières . MSF Manual for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Visceral Leishmaniasis (Kala-Azar) under Field Conditions. MSF-Holland; Amsterdam: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guthmann JP, Ruiz A, Priotto G, Kiguli J, Bonte L, Legros D. Validity, reliability and ease of use in the field of five rapid tests for diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum in Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96:254–57. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan KM, Gorstein J. ANTHRO. Software for Calculating Pediatric Anthropometry. WHO; Atlanta: CDC & Geneva: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO . Iron deficiency anaemia. Assessment, prevention, and control. A guide for programme manager. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filmer D, Pritchett L. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data – or tears: an application to educational enrolment in states of India. Demography. 2001;38:115–32. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MT. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:224–227. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières) MSF kala-azar project in Pokot area: summary report of medical activities period: 2000-2004. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jahn A, Lelmett JM, Diesfeld HJ. Seroepidemiological study on kala-azar in Baringo District, Kenya. J Trop Med Hyg. 1986;89:91–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaefer KU, Kurtzhals JA, Sherwood JA, Githure JI, Kager PA, Muller AS. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis in Baringo District, Rift Valley, Kenya. A literature review. Trop Geogr Med. 1994;46:129–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaefer KU, Kurtzhals JA, Gachihi GS, Muller AS, Kager PA. A prospective seroepidemiological study of visceral leishmaniasis in Baringo District, Rift Valley Province, Kenya. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:471–75. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boussery G, Boelaert M, Van Peteghem J, Ejikon P, Henckaerts K. Visceral leishmaniasis (kala azar) outbreak in Somali refugees and Kenyan shepherds, Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:603–4. doi: 10.3201/eid0707.010746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvar J, Yactayo S, Bern C. Leishmaniasis and poverty. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:552–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ranjan A, Sur D, Singh VP, et al. Risk factors for Indian kala-azar. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:74–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bern C, Joshi AB, Jha SN, et al. Factors associated with visceral leishmaniasis in Nepal: bed-net use is strongly protective. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:184–88. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.63.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bern C, Hightower AW, Chowdhury R, et al. Risk factors for kala-azar in Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:655–62. doi: 10.3201/eid1105.040718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnett PG, Singh SP, Bern C, Hightower AW, Sundar S. Virgin soil: the spread of visceral leishmaniasis into Uttar Pradesh, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:720–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno EC, Melo MN, Genaro O, et al. Risk factors for Leishmania chagasi infection in an urban area of Minas Gerais State. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:456–63. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822005000600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schenkel K, Rijal S, Koirala S, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in southeastern Nepal: a cross-sectional survey on Leishmania donovani infection and its risk factors. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1792–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahluwalia IB, Bern C, Costa C, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: consequences of a neglected disease in a Bangladeshi community. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69:624–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anoopa Sharma D, Bern C, Varghese B, et al. The economic impact of visceral leishmaniasis on households in Bangladesh. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:757–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan JR, Mbui J, Rashid JR, et al. Spatial clustering and epidemiological aspects of visceral leishmaniasis in two endemic villages, Baringo district, Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:308–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.El-Hassan AM, Zijlstra EE, editors. Leishmaniasis in Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95(Suppl 1):1–75. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elnaiem DE, Mukhawi AM, Hassan MM, et al. Factors affecting variations in exposure to infections by Leishmania donovani in eastern Sudan. East Mediterr Health J. 2003a;9:827–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heisch RB, Guggisberg CAW, Teesdale C. Studies in leishmaniasis in East Africa. I>> Sandflies of the Kitui kala-azar area in Kenya, with descriptions of six new species. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1956;50:209–226. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(56)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basimike M, Mutinga MJ. Studies on the vectors of leishmaniasis in Kenya: phlebotomine sandflies of Sandai location, Baringo district. East Afr Med J. 1997;74:582–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamilton JG, El Naiem DA. Sugars in the gut of the sandfly Phlebotomus orientalis from Dinder National Park, Eastern Sudan. Med Vet Entomol. 2000;14:64–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ngumbi PM, Lawyer PG, Johnson RN, Kiilu G, Asiago C. Identification of phlebotomine sandfly bloodmeals from Baringo District, Kenya, by direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Med Vet Entomol. 1992;6:385–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1992.tb00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takken W. Do insecticide-treated bednets have an effect on malaria vectors? Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:1022–1030. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]