Abstract

In this study we provide evidence that the transcription factor BCL11B represses expression from the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) in T lymphocytes through direct association with the HIV-1 LTR. We also demonstrate that the NuRD corepressor complex mediates BCL11B transcriptional repression of the HIV-1 LTR. In addition, BCL11B and the NuRD complex repressed TAT-mediated transactivation of the HIV-1 LTR in T lymphocytes, pointing to a potential role in initiation of silencing. In support of all the above results, we demonstrate that BCL11B affects HIV-1 replication and virus production, most likely by blocking LTR transcriptional activity. BCL11B showed specific repression for the HIV-1 LTR sequences isolated from seven different HIV-1 subtypes, demonstrating that it is a general transcriptional repressor for all LTRs.

Keywords: HIV, HIV-1 subtypes, LTR, TAT, BCL11B, NuRD complex, T lymphocytes, transcriptional repression

Introduction

Expression of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) genes is controlled by the 5’ long terminal repeat (LTR) and by viral and host transcription factors which bind to DNA response elements localized within this region (Greene, 1990; Klotman et al., 1991; Pereira et al., 2000). The viral transactivator protein Tat plays a critical role in activation of transcription from the LTR (Gaynor, 1995; Jeang, Shank, and Kumar, 1988; Kao et al., 1987; Pereira et al., 2000). In addition, numerous cellular transcription factors were found to regulate transcription from the LTR, including Sp1 (Demarchi et al., 1993; Garcia et al., 1987; Kamine, Subramanian, and Chinnadurai, 1991; Schwartz et al., 2000), NF-kB (Bounou, Dumais, and Tremblay, 2001; Demarchi et al., 1993; Mukerjee et al., 2007; Perkins et al., 1993; Podolin and Prystowsky, 1991), NFAT (Demarchi et al., 1993; Giffin et al., 2003), HMG protein (Sheridan et al., 1995), C/EBP (Dumais et al., 2002; Henderson, Zou, and Calame, 1995; Mukerjee et al., 2007), AP-1, Ets-1, LEF-1, and YY1 (cited in (Gaynor, 1992; Pereira et al., 2000). Nuclear hormone receptors, including COUP-TF, were also demonstrated to participate in the transcriptional activation from the LTR (Rohr et al., 2000; Schwartz et al., 2000).

Participation of cellular transcriptional regulators in HIV-1 silencing is of major interest, as this process can be implicated in virus latency. Previously, HMGB1 (Naghavi et al., 2003) and BCL11B (CTIP2) (Marban et al., 2005; Marban et al., 2007; Rohr et al., 2003) were found to repress transcription from the LTR. However, the studies on BCL11B-mediated transcriptional repression of the LTR were conducted by overexpressing BCL11B in microglial cells (Marban et al., 2005; Marban et al., 2007; Rohr et al., 2003). Microglial cells are immune cells of myeloid origin present in the central nervous system (Hickey and Kimura, 1988). In the immune system BCL11B is specifically and restrictively expressed in T lymphocytes (Cismasiu et al., 2005; Cismasiu et al., 2006; Wakabayashi et al., 2003a; Wakabayashi et al., 2003b). CD4+ T lymphocytes are an important target for HIV-1 infection and the role of BCL11B in transcriptional control of HIV-1 LTR in these cells has not been addressed before.

BCL11B is a C2H2 zinc finger transcriptional regulator required for T cell development, both at beta selection checkpoint at the DN3 stage (Wakabayashi et al., 2003b), and in positive selection of double positive (DP) thymocytes (Albu et al., 2007). Additionally, BCL11B was demonstrated to be a crucial survival factor for both double negative (DN) and DP thymocytes (Albu et al., 2007; Wakabayashi et al., 2003b)

At molecular level BCL11B has been shown previously to elicit transcriptional repression when tethered to promoters through the COUP-TF nuclear receptors and heterologous DNA binding domains (Avram et al., 2000) or through direct binding of its own response elements (Avram et al., 2002; Cismasiu et al., 2005). We previously demonstrated, using unbiased approaches, that the endogenous BCL11B complexes are associated with the corepressor complex NuRD in CD4+ T lymphocyte, and that these complexes harbor histone eacetylase (HDAC) activity sensitive to trichostatin A (TSA), an inhibitor of the NuRD HDACs (Cismasiu et al., 2005). We also demonstrated that the NuRD components MTA1 and MTA2 directly interact with BCL11B, allowing the recruitment of the NuRD complex to targeted promoters (Cismasiu et al., 2005).

As CD4+ T lymphocytes represent a major target for HIV infection, as well as a source of virus (Dalgleish et al., 1984), it is of interest whether BCL11B regulates LTR activity in these cells as well. In this study, we provide evidence that the HIV-1 LTR is a target for BCL11B transcriptional repression and that the NuRD components MTA1, and to al lesser extent MTA2, augmented the transcriptional repression of the HIV-1 LTR by BCL11B. In addition, BCL11B-NuRD complex repressed the transactivation mediated by TAT on HIV-LTR, results which support the implication of BCL11B-NuRD complex in initiation of silencing of HIV-LTR. Endogenous BCL11B and the NuRD complex were found to associate with the integrated HIV-1 LTR in CD4+ T lymphocytes, therefore directly implicating BCL11B and the NuRD complex in the transcriptional repression of HIV-1 gene expression in T lymphocytes. Importantly, this study also demonstrates that the BCL11B-mediated transcriptional repression of the LTR is well-conserved over different HIV-1 subtypes, and further, suggests that the interaction of BCL11B with the LTR could be exploited for a novel anti-retroviral therapy.

Results

Enhanced expression of BCL11B in Jurkat T lymphocytes represses transcription from the LTR

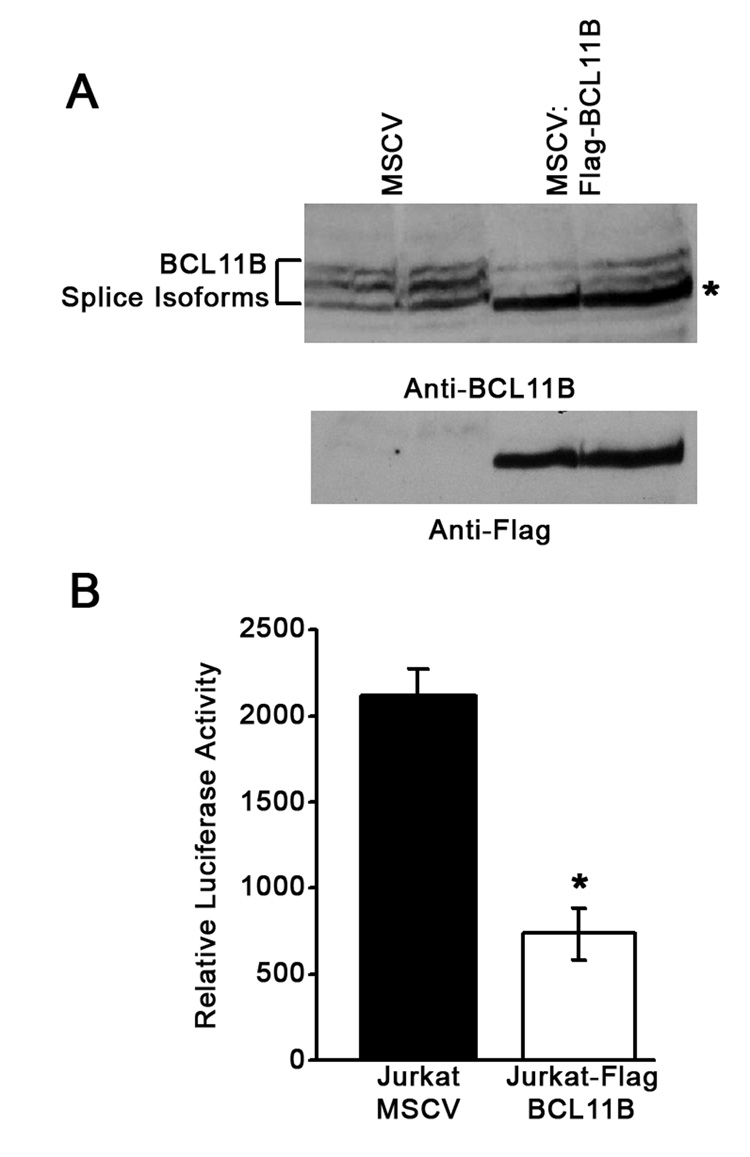

BCL11B was previously demonstrated to repress expression from the HIV-1 LTR, when overexpressed in microglial cells (Marban et al., 2005; Marban et al., 2007; Rohr et al., 2003). However, BCL11B has restricted expression to T lymphocytes within the immune system, and its expression is excluded from B lymphocyte or myeloid lineages (Cismasiu et al., 2005; Cismasiu et al., 2006; Wakabayashi et al., 2003a; Wakabayashi et al., 2003b). How BCL11B acts on the HIV-1 LTR in T lymphocytes has never been addressed. To determine whether BCL11B is implicated in the transcriptional regulation of LTR in human T lymphocytes, we employed the Jurkat T cells stably transduced with retroviruses expressing GFP (Jurkat) and Flag-BCL11BIRES-GFP (Jurkat-BCL11B) (Cismasiu et al., 2006). Populations of cells were sorted based on GFP expression, expanded and tested for the presence of Flag-BCL11B (Fig. 1A). Jurkat-BCL11B and Jurkat cells were further transfected with HIV-1 LTR-Luciferase construct. Results revealed that overexpression of BCL11B significantly repressed the expression from the HIV-1 LTR (Fig. 1B), demonstrating that BCL11B plays a role in the repression of HIV-1 LTR expression in T cells.

Figure 1. Sustained BCL11B expression in Jurkat cells represses the HIV-1 LTR activity.

(A) Western blot analysis of nuclear extracts from Jurkat cells stably transduced with retroviruses expressing GFP (MSCV) and the small splice variant of BCL11B (asterisk), Flag-BCL11B-IRES-GFP, (MSCV:Flag-BCL11B) (Cismasiu et al., 2006). (B) Jurkat-MSCV and Jurkat MSCV:Flag-BCL11B cells were transfected with the HIV-1 LTR-Luciferase construct, and the cellular extracts were subsequently analyzed for luciferase activity as previously described (Cismasiu et al., 2006). The asterisk indicates significant statistical difference (P<0.05) between Jurkat-MSCV and Jurkat MSCV:Flag-BCL11B. This is a representative experiment of three with similar results.

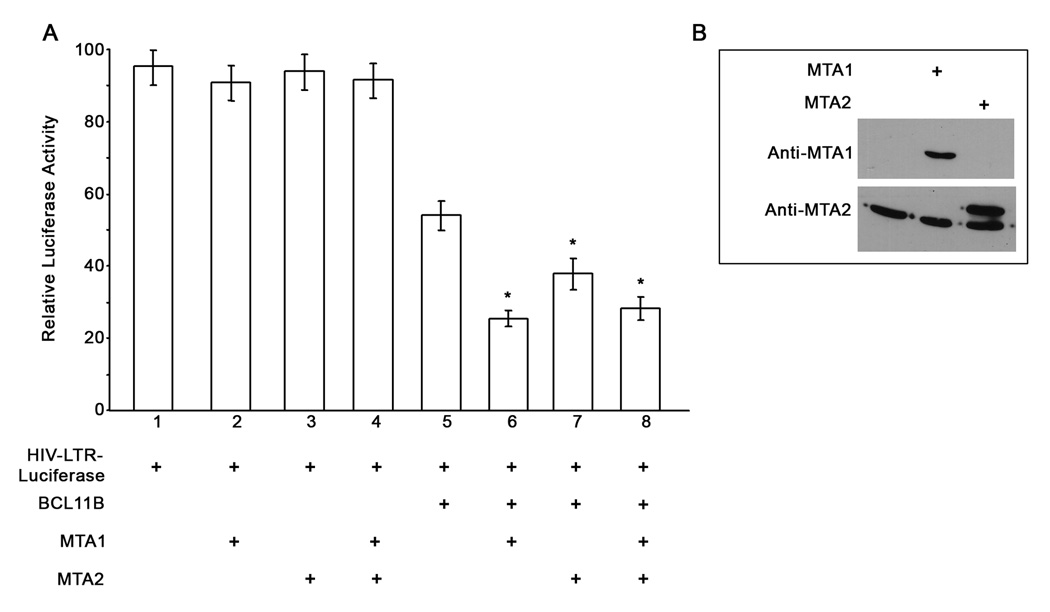

Repression mediated by BCL11B on the HIV-1 LTR is augmented by the NuRD component MTA1, and to a lesser extent by MTA2

We previously demonstrated that BCL11B and the NuRD complex associate in Jurkat T lymphocytes (Cismasiu et al., 2005). We also demonstrated that the NuRD components MTA1 and MTA2 mediate the interaction of BCL11B with the NuRD complex (Cismasiu et al., 2005). To demonstrate that the NuRD complex functionally participates in the transcriptional repression mediated by BCL11B we conducted luciferase reporter assays in which HeLa cells were transfected with HIV-LTR-reporter, BCL11B and the components of the NuRD complex MTA1 and MTA2 (Cismasiu et al., 2005). BCL11B repressed the HIV-1 LTR reporter activity (Fig. 2, lane 5). MTA1 (Fig. 2, lane 6), and to a lesser extent MTA2 (Fig. 2, lane 7), augmented the repression function of BCL11B on HIV LTR activity. However the effect was not synergistic (Fig. 2, lane 8). The LTR repression was dependent on the presence of BCL11B, as neither MTA1 nor MTA2 alone (Fig. 2, lanes 2, 3 and 4), repressed the HIV-LTR at significant levels.

Figure 2. Transcriptional repression of the HIV-1 LTR by BCL11B is augmented by MTA1, and to a lesser extent by MTA2 of the NuRD complex.

(A) Luciferase assays from HeLa cells transfected with HIV-1 LTR-Luciferase and β-gal (lanes 1–8), BCL11B (lanes 5–8), MTA1 (lanes 2, 4, 6 and 8) and MTA2 (lanes 3, 4, 7 and 8). This is a representative experiment of three with similar results. The asterisks indicate that the samples in lanes 6, 7 and 8 are statistically different (P<0.05) from the sample in lane 5. (B) Western blot analysis of nuclear extracts of HeLa cells trasfected with either MTA1 or MTA2.

These results taken together implicate BCL11B and the NuRD complex in silencing of HIV expression.

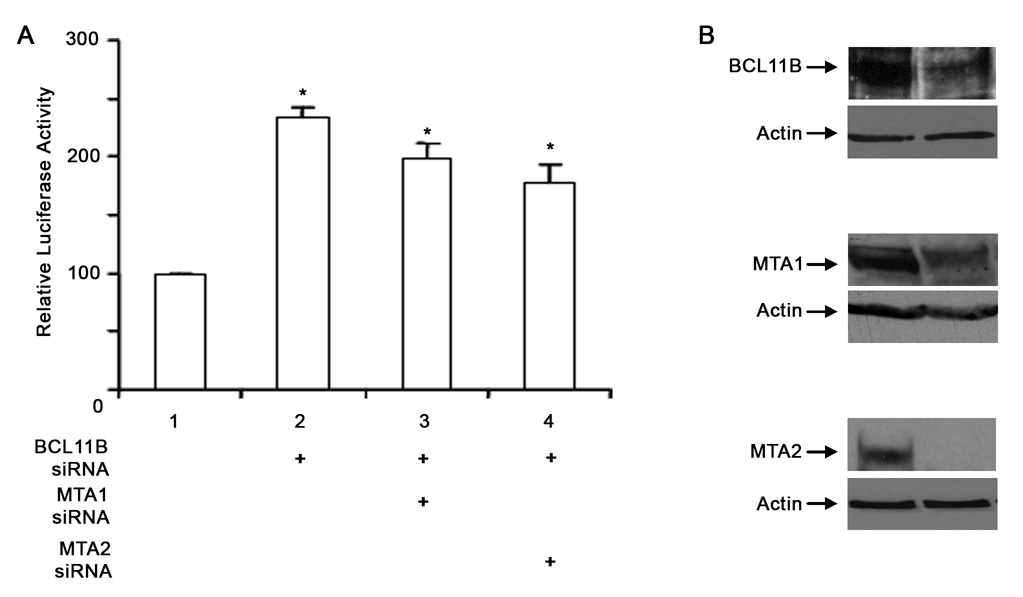

Knockdown of BCL11B and MTAs results in derepression of HIV-LTR

To further demonstrate that endogenous BCL11B plays a role in the repression of HIV-1 LTR, 1G5 Jurkat cells, endogenously expressing BCL11B and containing an HIV-LTR-luciferase expression cassette integrated into the genome (Aguilar-Cordova et al., 1994), were transfected with BCL11B siRNA. Knockdown of BCL11B (Fig. 3B) resulted in significant derepression of HIV-1 LTR (Fig. 3A), demonstrating that endogenous BCL11B plays a role in silencing of this promoter. Further, knockdown of MTA1 or MTA2 (Fig. 3B) also resulted in derepression of HIV-1 LTR (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Knockdown of BCL11B results in derepression of HIV-LTR.

(A) 1G5 Jurkat cells, containing the HIV-LTR-luciferase expression cassette stably integrated into the genome, were transfected with the indicated siRNAs and the extracts were analyzed for luciferase activity. The Y-axis represents percent derepression of luciferase activity in siRNA samples (lanes 2, 3 and 4) relative to control siRNA (lane 1). The asterisks indicate that the samples in lanes 2, 3 and 4 are statistically different (P<0.05) from the sample in lane 1. (B) Western blot analysis of nuclear extracts from 1G5 Jurkat cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs.

These results taken together show that endogenous BCL11B and the NuRD complex exert a silencing effect on the HIV-1 LTR.

BCL11B and MTA1 inhibit HIV-LTR transactivation mediated by TAT

Because HIV TAT plays a critical role in transcription from the HIV-LTR (Benkirane et al., 1998; Jeang, Shank, and Kumar, 1988; Kao et al., 1987; Nekhai and Jeang, 2006), we investigated the impact of BCL11B and the associated NuRD complex on HIV-LTR transactivation by TAT, to determine whether BCL11B and the associated NuRD complex can initiate silencing in conditions when HIV-LTR is activated by TAT. For this purpose 1G5 Jurkat cells were co-transfected with HIV TAT, BCL11B, MTA 1 or MTA 2. Our results show that BCL11B significantly repressed TAT-mediated transcriptional activation of the HIV-1 LTR (Fig. 4). MTA1 significantly augmented the repression mediated by BCL11B (Fig. 4), while MTA2 failed to significantly augment the BCL11B-mediated repression of HIV-LTR (Fig. 4). These results, as well as the data above and bellow, suggest that MTA1 is the preferred partner of BCL11B in the transcriptional repression of HIV-LTR, as previously suggested by our published data (Cismasiu et al., 2005).

Figure 4. BCL11B and MTA1 inhibit TAT-mediated transactivation of HIV-1 LTR.

1G5 Jurkat cells were co-transfected with HIV Tat, BCL11B, MTA 1 and MTA 2 plasmids as indicated. Cells were collected at 48 hours post-transfection and analyzed for luciferase activity. The Y-axis represents percent inhibition of luciferase activity relative to the Tat alone (lane 1). The asterisks indicate that the samples in lanes 2 and 3 are statistically different (P<0.05) from the sample in lane 1.

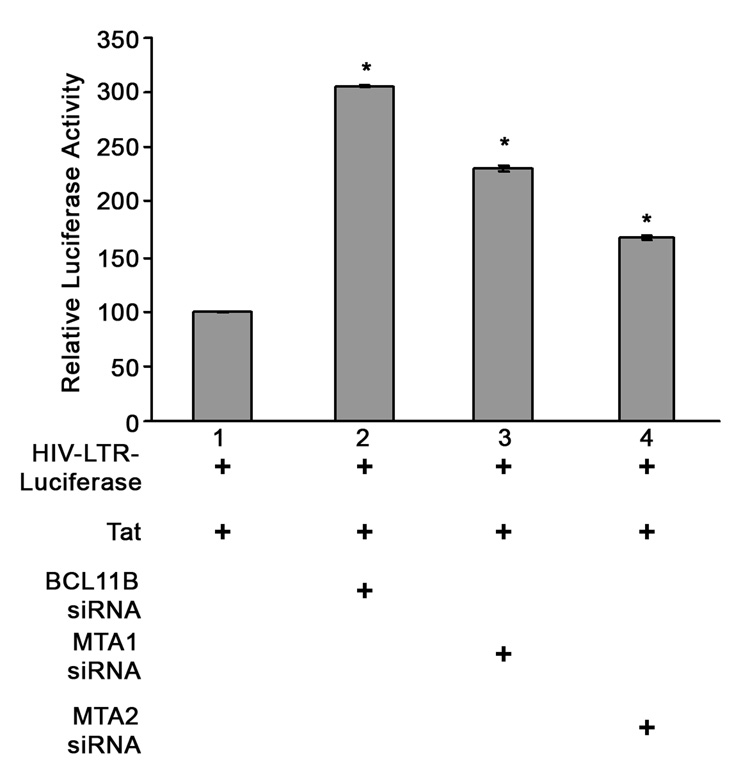

To demonstrate that indeed the endogenous BCL11B plays a role in the repression of HIV-1 LTR when activated by TAT, 1G5 Jurkat cells were transfected with TAT and BCL11B siRNA. Knockdown of BCL11B resulted in significant increase of TAT-mediated transactivation of HIV-1 LTR (Fig. 5), demonstrating that endogenous BCL11B plays a role in initiation of silencing of TAT-activated HIV-LTR. Knockdown of MTA1 or MTA2 also resulted in significant increase of TAT-mediated transactivation of HIV-1 LTR, revealing that the NuRD complex plays a role in initiation of silencing from TAT-activated HIV-LTR (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Knockdown of BCL11B and the NuRD components MTA1 and MTA2 reduces the transactivation of HIV-LTR by TAT.

1G5 Jurkat cells were transfected with TAT and the indicated siRNAs, harvested at 48 hours post-transfection and analyzed for luciferase activity. The Y-axis represents percent luciferase activity of specific siRNA samples (lanes 2, 3 and 4) versus siRNA control (lane 1). The asterisks indicate that the samples in lanes 2, 3 and 4 are statistically different (P<0.05) from the sample in lane 1.

These results taken together show that BCL11B and the NuRD complex play a role in initiation of silencing of TAT-activated HIV-LTR, in addition to exerting a silencing effect on the HIV-1 LTR in the absence of TAT.

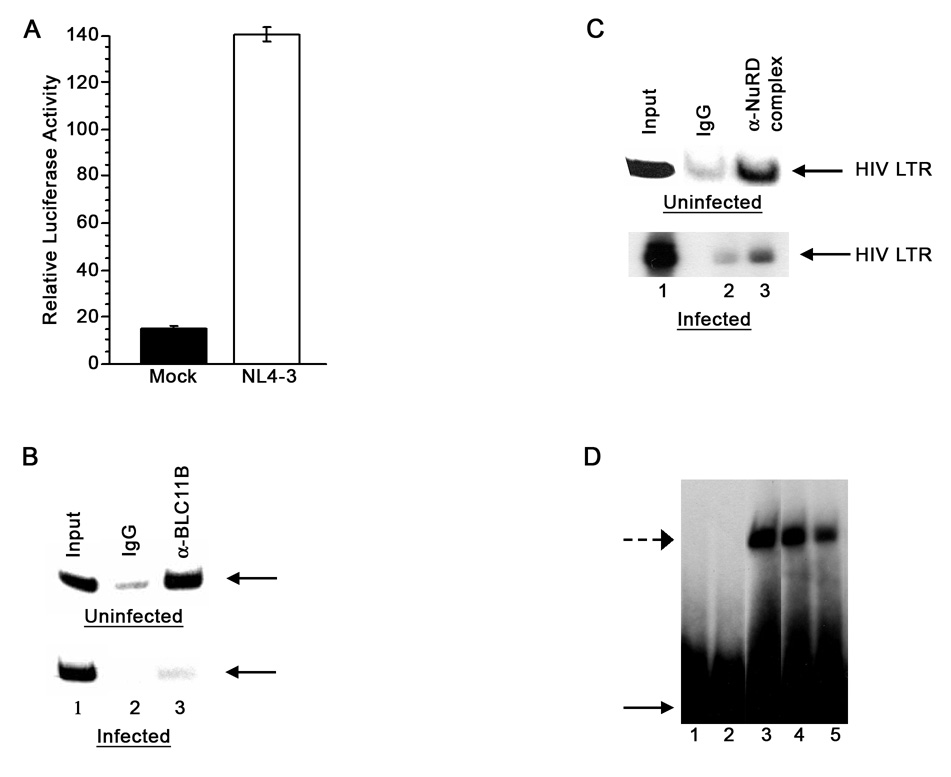

BCL11B and the NuRD complex associate with the integrated HIV-LTR in Jurkat T lymphocytes

Following infection, the HIV-1 DNA is integrated into the host genome and the HIV-1 LTR is organized into chromatin (reviewed in (He, Ylisastigui, and Margolis, 2002; Marzio and Giacca, 1999)). Chromatinization of the HIV-1 LTR creates a transcriptionally inactive state, which contributes to the establishment and maintenance of latency in the absence of any stimulation (He, Ylisastigui, and Margolis, 2002; Lusic et al., 2003). We therefore investigated whether endogenous BCL11B is present on the integrated HIV-1 LTR in 1G5 Jurkat T lymphocytes and consequently participates in the silencing of the promoter. In the absence of any stimulation, the activity of this promoter is reduced, however it increases significantly as a result of viral infection ((Aguilar-Cordova et al., 1994) and Fig. 6A,). Immunoprecipitation of the crosslinked extracts from uninfected 1G5 cells with anti-BCL11B (B26-44) antibodies significantly enriched the HIV-1 LTR, (Fig. 6B upper panel). Immunoprecipitation of the crosslinked extracts from infected cells resulted in significantly less enrichment of the HIV-1 LTR (Fig. 6B, lower panel), compared to uninfected cells. Therefore, these results suggest that BCL11B is predominantly associated with the silenced HIV-1 LTR from uninfected cells, however a small fraction of BCL11B still remains associated with the HIV-LTR even in infected cells.

Figure 6. Endogenous BCL11B and the NuRD complex associate with the HIV-1 LTR in Jurkat 1G5 cells and BCL11B directly binds HIV-1 LTR in vitro.

(A) 1G5 Jurkat cells were infected with NL4-3 (white bar) or mock (black bar) and the luciferase activity was evaluated at three days after infection. (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation with anti-BCL11B antibody (B26-44) (lane 3) or IgG (lane 2) of nuclear extracts from uninfected (upper panel) or infected (lower panel) Jurkat 1G5 cells. (C) Chromatin immunoprecipitations with the NuRD antibodies anti-HDAC2 and -MTA1 (lane 3) or IgG (lane 2) from uninfected (upper panel) and infected (lower panel) 1G5 nuclear extracts. In B and C lane 1 represents the input which in all cases was 0.2%. (D) Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA): [32P]HIV-1 LTR fragment (HIV LTR −326 - +62) probe was incubated with GST (lane 2) or GST-BCL11B 356–812 (lanes 3– 5) in the presence of cold BCL11B response element oligos (lane 4) or noncompetitive oligos (lane 5). BCL11B-[32P] HIV-1 LTR complexes are indicated by an interrupted arrow and the free probe is indicated by a continuous arrow.

Because BCL11B is known to associate with the NuRD complex we wanted to investigate whether the NuRD complex is also present on the HIV-1 LTR promoter. We therefore conducted immunoprecipitation of the crosslinked extracts from uninfected 1G5 cells with the NuRD complex antibodies and our results show that the HIV-LTR was highly enriched in the NuRD-IP-ed complex from uninfected, and to a lesser extent from infected cells (Fig. 6C). These results therefore show that the NuRD complex is also present on HIV-1 LTR, predominantly in uninfected cells, but a fraction still remains on the promoter even in infected cells.

All these data taken together show that BCL11B and the NuRD complex are associated with the HIV-1 LTR, predominantly in uninfected cells, however a small fraction is also associated with the HIV-1 LTR in infected cells.

BCL11B directly binds the HIV-1 LTR

The HIV-1 LTR contains several BCL11B consensus response elements. We already demonstrated by ChIP assays the association of BCL11B with the HIV-1 LTR, however another transcription factor may mediate this interaction. We therefore investigated whether BCL11B may exert its transcriptional repression function on HIV-1 expression by direct binding to the HIV-1 LTR. To test the direct binding of BCL11B to the HIV-1 LTR we employed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) using bacterially expressed and purified GST-BCL11B. The results clearly showed that GST-BCL11B 356–812, which contains the carboxyl zinc fingers involved in DNA binding (Fig. 6, lane 3), but not GST (Fig. 6, lane 2), bound the HIV-1 LTR, but not a control nonspecific DNA of a similar size covering the BCL11B ORF (data not shown). Addition of excess cold BCL11B RE oligo competitor abolished binding (Fig. 6, lane 5), while addition of a nonspecific oligo did not have any effect (Fig. 6, lane 4), demonstrating the specificity of binding. These results taken together clearly show that BCL11B directly binds to the HIV-1 LTR in vitro, therefore suggesting that the HIV-1 LTR may potentially be a direct target for BCL11B.

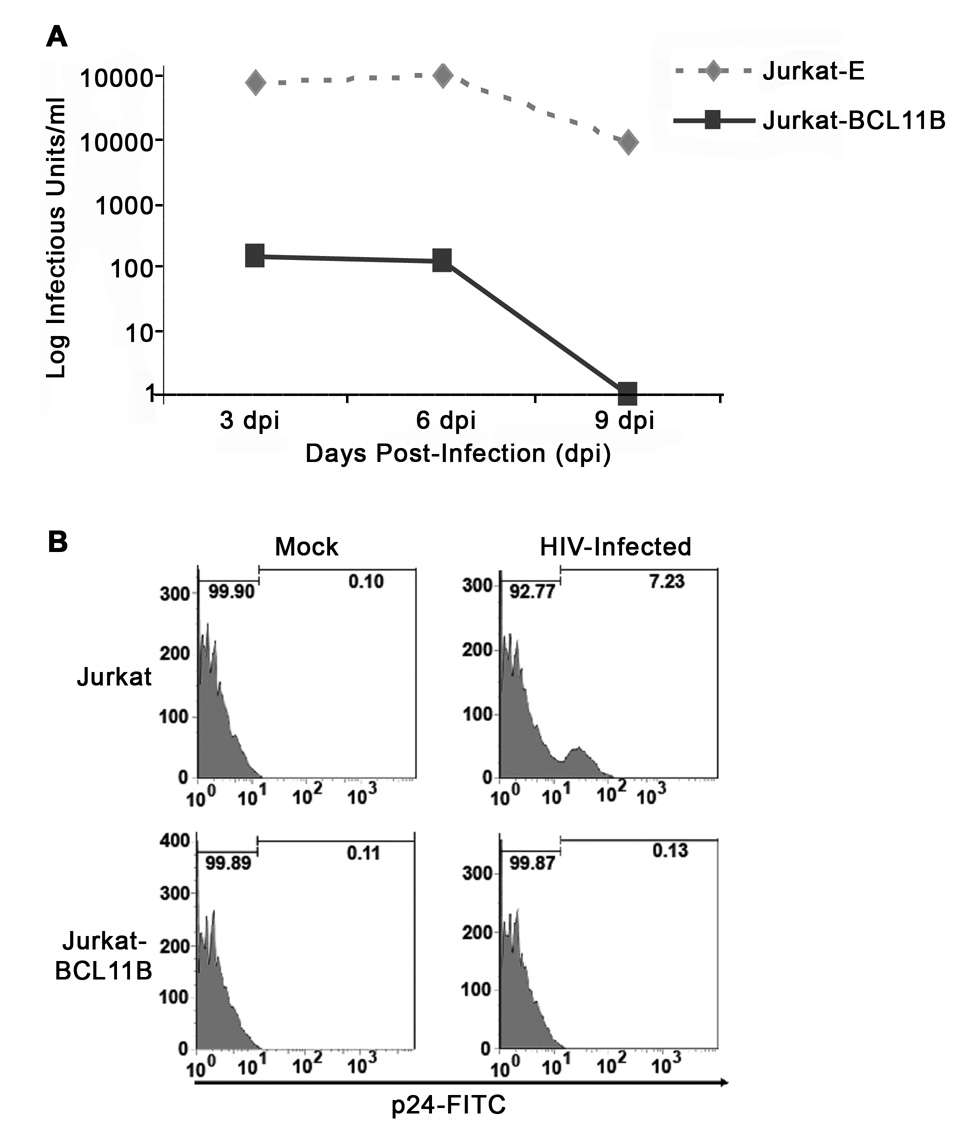

Overexpression of BCL11B inhibits viral replication of infectious HIV-1

To demonstrate that transcriptional repression mediated by BCL11B translates into inhibition of infectious virion production, we conducted experiments testing whether BCL11B inhibits viral replication of infectious HIV-1 in T cells. Jurkat and Jurkat-BCL11B cells were infected with HIVNL4-3, and the infected cell culture medium was analyzed for the amount of infectious virus produced at various times post-infection (Fig. 7A). In addition, at peak virus production, the infected cell populations were analyzed for intracellular expression of p24 virus capsid protein, as a measure of virus production by individual cells (Fig. 7B). Our results demonstrate that overexpression of BCL11B strongly inhibited HIVNL4-3 virus replication and production, and rendered the Jurkat-BCL11B cells much less permissive for productive infection compared to Jurkat cells, suggesting that LTR transcriptional repression by BCL11B results in reduced viral replication and production.

Figure 7. T cells overexpressing BCL11B are non-permissive for HIVNL4-3 infection.

(A) Jurkat and Jurkat-BCL11B cells were infected at an MOI=0.1 and subsequently analyzed for infectious virus production by GHOST assay at the indicated time points post-infection, (B) as well as for intracellular p24 virus capsid protein expression by flow cytometry at 6 days post-infection. Graphs shown are representative of 3 independent infection experiments with similar results.

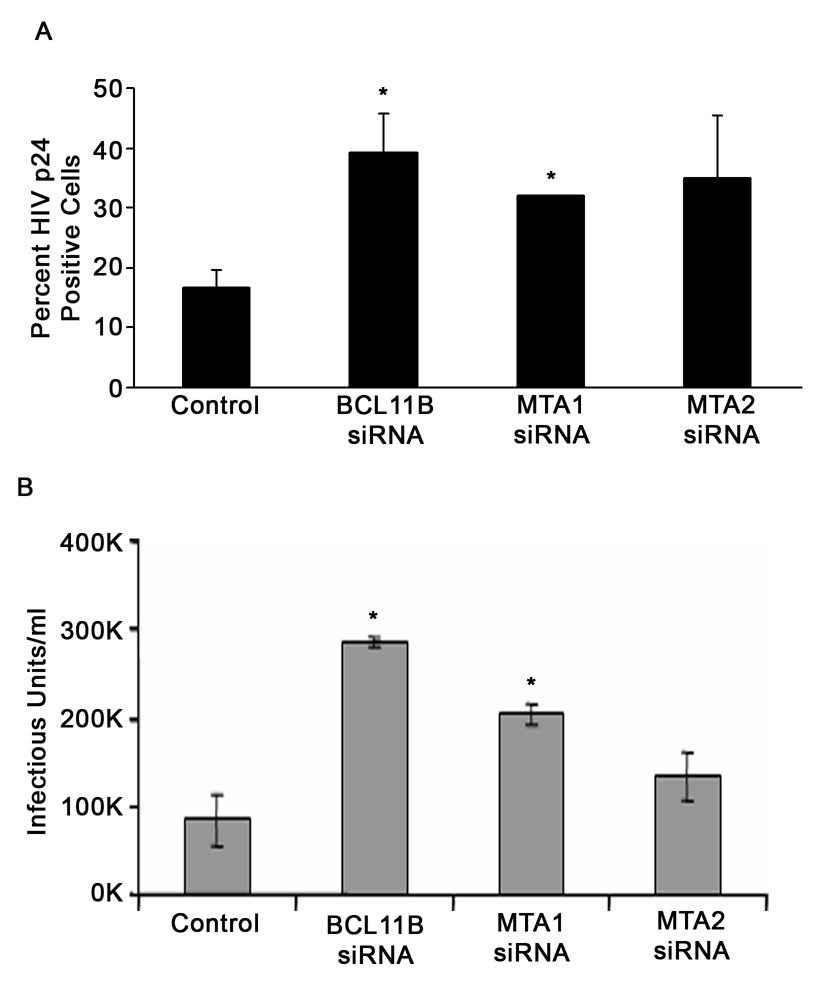

Knockdown of BCL11B and MTA1 enhances viral replication and production

Conversely, when BCL11B was downregulated by siRNA prior to HIV-1 infection, the infected cell populations showed higher intracellular expression of p24 virus capsid protein compared to siRNA control, indicating that in the absence of BCL11B viral replication is enhanced (Fig. 8A). In addition, knockdown of MTA1, but not MTA2, resulted in significant increase in the intracellular levels of p24 virus capsid protein in infected cells, demonstrating that the reduction of MTA1 of the NuRD also favors viral replication. In addition, the infected cell culture medium was analyzed for the amount of infectious virus produced post-infection and the results show that knockdown of BCL11B and MTA1, but not MTA2, led to a significant increase of the amount of virus in the media (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. Knockdown of BCL11B enhances HIV-1 replication in a spreading infection.

(A) siRNA-transfected SUPT-1 cells were infected with HIV-NL4-3 (MOI=0.1) and infected cell populations were analyzed by flow cytometry for percent of cells positive for intracellular p24 expression at 5 days post-infection. The asterisks indicate that BLC11B siRNA and MTA1 siRNA samples are statistically different (P<0.05) from control siRNA sample. (B) Cell-free supernatants from the cultures in panel A were collected at 5 days post-infection and used to infect GHOST cells. The numbers of EGFP-expressing cells were counted, and the infectious virus titer of each culture was calculated. The asterisks indicate that BLC11B siRNA and MTA1 siRNA samples are statistically different (P<0.05) from control siRNA sample.

These results taken together suggest that the LTR transcriptional repression by endogenous BCL11B and the NuRD complex translates in control of viral replication and virus production.

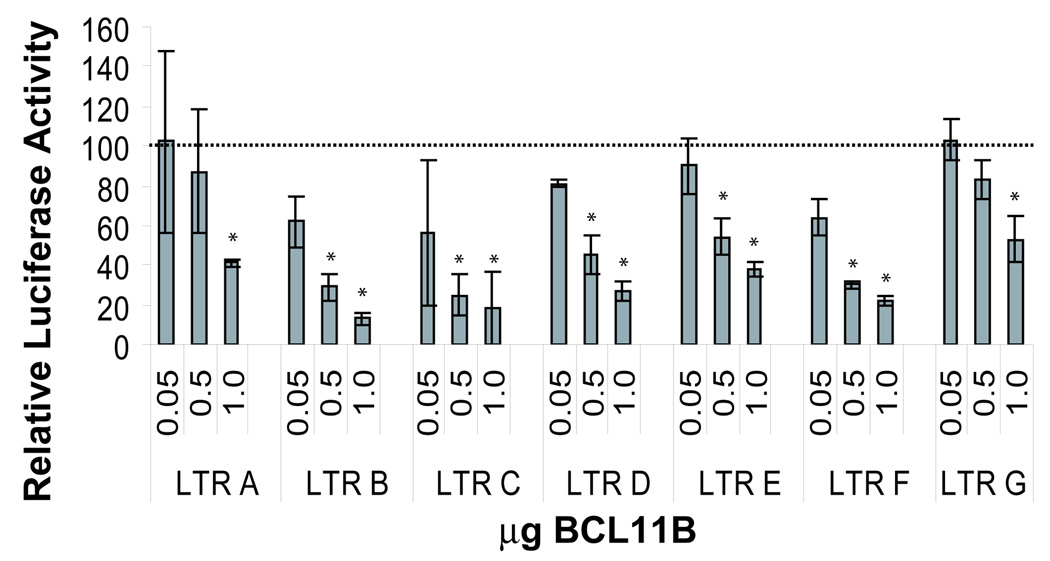

BCL11B represses LTR sequences of seven HIV-1 subtypes

As BCL11B consensus sites in the U3 modulatory region of the HIV-1 LTR are conserved throughout different HIV-1 subtypes (data not shown), we wanted to determine whether BCL11B transcriptional repression is conserved within the isolated subtypes. For this purpose HeLa cells were co-transfected with each of the A-G LTR-luciferase constructs, and increasing amounts of BCL11B DNA, and analyzed for LTR activity by luciferase assays. BCL11B showed specific transcriptional repression for LTRs A-G with no effect on the basal control promoter (pGL3) expression (Fig. 9). All subtypes tested were sensitive to concentration-dependent BCL11B repression, presenting statistically significant repression at higher concentrations of BCL11B, and suggesting that BCL11B is a general transcriptional repressor for all tested HIV-1 LTRs.

Figure 9. BCL11B represses LTR (A–G) activity in a dose-dependent manner.

Luciferase assays from HeLa cells transfected with 0.5 µg HIV-LTR (A–G)-luciferase DNA and either 0.05, 0.5, or 1 µg of BCL11B DNA. The luciferase activity was normalized to the activity of each LTR construct in the absence of any added BCL11B DNA. The asterisks indicate that the samples transfected with specific amounts of BCL11B are statistically different compared to the corresponding sample lacking BCL11B. The graph is representative of 3–5 independent experiments.

Discussion

It has been established by previous studies that following infection of susceptible cells, HIV-1 DNA is integrated into the host genome and the LTR is organized into chromatin (reviewed in (He, Ylisastigui, and Margolis, 2002; Marzio and Giacca, 1999)). Transcription of the HIV-1 provirus is regulated by viral and cellular transcription factors, which bind to sites in the HIV-1 LTR (reviewed in (Pereira et al., 2000)). However, chromatinization of the HIV-1 LTR creates a transcriptionally inactive state of the proviral promoter, which contributes to the establishment and maintenance of latency in the absence of any stimulation (He, Ylisastigui, and Margolis, 2002; Lusic et al., 2003). Based on the data reported here BCL11B and the NuRD complex may play a role in the generation of a silenced state of chromatin on the integrated HIV-1 promoter in T lymphocytes, and potentially on other integrated retroviral promoters. Though BCL11B and the NuRD complex are predominantly present on the HIV-LTR in the absence of infection, a small fraction of BCL11B-NuRD complex is still present on the promoter in conditions of infection. Knockdown of endogenous BCL11B and MTA1 resulted in increased activity of the TAT transactivator, and also enhanced virus replication and production in a spreading infection, thus supporting the role of endogenous BCL11B and NuRD complex in the repression of TAT-mediated transactivation from HIV-1 LTR in T cells, and in initiating of HIV-1 LTR silencing in T lymphocytes. Moreover, in conditions when the integrated promoter was activated by TAT, the addition of BCL11B repressed the TAT-mediated transactivation, suggesting again that BCL11B-NuRD complex is capable of initiating silencing in T lymphocytes. In conclusion, our results suggest that BCL11B acts on the HIV-1 LTR by two mechanisms. Under conditions conducive to LTR activation, such as during infection, a small fraction of BCL11B-NuRD complex is associated with the HIV-1 LTR. This small fraction is not sufficient to completely block the expression of the promoter when Tat is present. However, the complex does exert a level of control on TAT-mediated LTR transactivation, demonstrated by the fact that knockdown of BCL11B results in enhancement of transactivation mediated by TAT. The small fraction of BCL11B-NuRD complex present on the promoter under conditions favoring activation may play a role in “priming” the promoter for silencing. Thus, binding of additional BCL11B can initiate silencing by recruitment of more NuRD complex, which our results suggest is likely to occur through a mechanism by which BCL11B directly binds to the promoter. It is unlikely that BCL11B directly competes with TAT in binding the same response elements on the HIV-1 LTR, as the consensus binding sites of BCL11B do not resemble the Tar loop, which is the binding site of TAT (Avram et al., 2002), but rather through creation of unfavorable conditions for TAT binding. The increase in recruitment of the NuRD complex by BCL11B to the HIV-1 LTR results in subsequent deacetylation of histones and very likely restricts the association of both viral and cellular transcriptional activators with the promoter. The NuRD complex possesses both histone deacetylase and ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling activities (Xue et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1999), which allow the generation of a transcriptionally nonpermissive environment on targeted promoters (Liu and Bagchi, 2004; Xue et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1999). During conditions favoring silencing, a larger fraction of BCL11B-NuRD complex is associated with HIV-1 LTR, likely playing a role in maintaining HIV-1 LTR silencing. These two roles of endogenous BCL11B-NuRD complex in HIV-1 transcriptional silencing in T lymphocytes come in addition to the BCL11B-mediated inhibition of TAT transactivation function through redistribution to the heterochromatin compartment in microglial cells as a result of BCL11B overexpression (Rohr et al., 2003). Overall, our results suggest a preference of BCL11B to use MTA1-NuRD complex, as previously suggested by our published data (Cismasiu et al., 2005).

In HeLa cell models, other transcription factors such as YY1 and LSF were previously shown to cooperatively recruit HDAC1 to the integrated HIV-1 LTR which resulted in decreased expression from the HIV-1 LTR, hence implicating histone deacetylation in transcriptional repression of the integrated provirus and establishment of latency (Coull et al., 2000; He and Margolis, 2002). In microglial cells in conditions of overexpression of BCL11B, repression of HIV-1 LTR was found to directly recruit HDAC deacetylases without the requirement of the NuRD complex (Marban et al., 2007). However our results in T lymphocytes, which, unlike microglial cells, normally express BCL11B, demonstrate the presence of the NuRD complex on the HIV-1 LTR.

Here we implicate the NuRD complex in association with BCL11B in silencing of HIV-1 gene expression in T lymphocytes, and potentially in silencing of other viruses. In this respect it is of interest that individual components of the NuRD complex were previously found to regulate viral activities by association with viral proteins. For example, HDAC1 was shown to associate with the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) Tax oncoprotein, to negatively regulate viral gene expression (Ego, Ariumi, and Shimotohno, 2002). Other examples include the human papilloma virus E7 protein, which was shown to associate with Mi2 of the NuRD complex to promote cell growth (Brehm et al., 1999), and the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C, which was shown to associate with HDAC1 in relation to viral latency (Radkov et al., 1999).

Viral strains belonging to several major subtypes (A–G) isolated from various infected populations worldwide have LTR sequences which differ by 5–20%, which may account for differences in their transctiptional activity (De Arellano, Soriano, and Holguin, 2005; Jeeninga et al., 2000). These LTR sequence differences may account for differences in clinical outcome (De Arellano, Soriano, and Holguin, 2005; Hiebenthal-Millow et al., 2003; Jeeninga et al., 2000; Naghavi et al., 1999; van Opijnen et al., 2004). Our results demonstrate that BCL11B represses expression from all seven LTR subtypes sequences tested, suggesting that BCL11B is a general transcriptional repressor for all major HIV-1 LTRs and may be involved in HIV-1 latency. Though consensus BCL11B binding sites exist in all of the subtypes studied, there are also variations, which may account for the slight differences in the transcriptional repression observed among the subtypes. The BCL11B-mediated transcriptional repression across many virus subtypes demonstrates a global LTR transcriptional repression activity for BCL11B, and suggests a possible novel therapeutic approach against HIV-1 disease. Since BCL11B expression is limited to T lymphocytes and neurons, it may be possible to augment current HAART therapies by development of a small molecule to stabilize BCL11B and NuRD complex binding to the LTR, and thus increase the transcriptional repression and implicitly inhibition of replication mediated by this host factor. Alternatively, if BCL11B is involved in virus latency, a periodic inhibition of BCL11B binding might decrease the pool of latently infected cells during chronic HIV infection.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

BCL11B, MTA1 and MTA2 clones were previously described (Cismasiu et al., 2005). pBlue3’LTR-luc containing LAI 3’ HIV-1 LTR (Klaver and Berkhout, 1994) was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, (Division ofAIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, NIH).

Cell culture, transfections and reporter assays

Jurkat cells were obtained from ATCC. The following cell lines were obtained though the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, NIH): Jurkat 1G5 cells (Aguilar-Cordova et al., 1994), Sup-T1 T cells (Smith et al., 1984) and GHOST-X4/R5 cells (Morner et al., 1999). Jurkat, Sup-T1 and A293T cells were grown as previously described (Cismasiu et al., 2005; Duus et al., 2001). Transfections and reporter assays were conducted as previously described (Cismasiu et al., 2005; Cismasiu et al., 2006).

siRNA silencing experiments

Control, BCL11B, MTA 1 or MTA2 siRNAs and their transfection were previously described (Cismasiu et al., 2005; Cismasiu et al., 2006). HIV-1NL4-3 stocks were produced by transfection of A293T cells, as previously described (Duus et al., 2001). Jurkat/Jurkat-BCL11B and Sup-T1 cells were infected with stock virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 0.1, or mock-infected for 2 hours, grown in fresh medium and analyzed at specific time points post-infection. Productively infected cells were analyzed for intracellular p24 by flow cytometry, and infectious virus release was analyzed by GHOST assay. GHOST cell HIV-1 Titer Assay was conducted as previously described (Morner et al., 1999).

Antibodies

Anti-BCL11B (B26-44), MTA1 and MTA2 antibodies were previously described (Cismasiu et al., 2005; Cismasiu et al., 2006) Anti-p24 clone KC57 conjugated to FITC was from Beckman Coulter.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

1G5 Jurkat cells containing the HIV-1 LTR-Luciferase integrated into the genome (Aguilar-Cordova et al., 1994) were used for ChIP assays which were conducted as previously described (Cismasiu et al., 2005; Cismasiu et al., 2006). In the case of the NuRD complex ChIP, prior to crosslinking with formaldehyde, the cells were crosslinked with dimethyl 3,3’-dithiobispropionimidate (DTBP) (Pierce), to assure crosslinling of the proteins in the complex. DTBP, an imidoester crosslinker with longer effective distance than formaldehyde, efficiently crosslinks proteins and was previously used successfully to crosslink components of the NuRD complex (Fujita et al., 2003; Fujita and Wade, 2004). The following primers crossing HIV-LTR −326 through +62 were used for amplification of the HIV-1 LTR: forward: 5’-cactgacctttggatggtgc-3’ and reverse: 5’-aggcttaagcagtgggttcc-3’.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

DNA binding experiments were conducted as previously described (Avram et al., 2002; Cismasiu et al., 2006). GST fusion proteins were expressed in the BL21 (DE3) plysS strain of E. coli and purified on glutathione Sepharose-4B (Pharmacia) using standard techniques.

Statistical Analysis

The Student T-test was used for statistical analysis and differences were considered significant when P values were <0.05.

Acknowledgements

We greatly acknowledge Dr. Paul Wade (Emory University) for antibodies against MTA2 and for advice with double crosslinking. The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program: pBlue3’LTR-luc from Dr. Reink Jeeninga and Dr. Ben Berkhout, Jurkat 1G5 cells from Drs. Estuardo Aguilar-Cordova and John Belmont, GHOST cells from Dr. Vineet N. Kewal Ramani and Dr. Dan R. Littman and Sup-T1 cells from Dr. James Hoxie. We thank Dr. Paul Higgins, Dr. John Schwarz and Dr. Jonathan Harton (AMC) for reading the manuscript and helpful suggestions. We thank Ms. Debbie Moran and Mr. Adrian Avram for help with preparation of the figures. This work was supported by National Institute of Health, NIAD (R01 AI067846 to DA).

Abbreviations Used

- BCL11B

B-cell CLL/lymphoma 11B

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- HDAC

histone deacetylase complex

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus 1

- LTR

long terminal repeat

- NuRD

Nucleosome Remodeling and Deacetylase

- MTA1

metastasis associated 1

- MTA2

metastasis associated 2

- TSA

trichostatin A

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguilar-Cordova E, Chinen J, Donehower L, Lewis DE, Belmont JW. A sensitive reporter cell line for HIV-1 tat activity, HIV-1 inhibitors, and T cell activation effects. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10(3):295–301. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albu DI, Feng D, Bhattacharya D, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Liu P, Avram D. BCL11B is required for positive selection and survival of double-positive thymocytes. J Exp Med. 2007;204(12):3003–3015. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avram D, Fields A, Pretty On Top K, Nevrivy DJ, Ishmael JE, Leid M. Isolation of a novel family of C(2)H(2) zinc finger proteins implicated in transcriptional repression mediated by chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF) orphan nuclear receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(14):10315–10322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avram D, Fields A, Senawong T, Topark-Ngarm A, Leid M. COUP-TF (chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor)-interacting protein 1 (CTIP1) is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. Biochem J. 2002;368(Pt 2):555–563. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkirane M, Chun RF, Xiao H, Ogryzko VV, Howard BH, Nakatani Y, Jeang KT. Activation of integrated provirus requires histone acetyltransferase. p300 and P/CAF are coactivators for HIV-1 Tat. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(38):24898–24905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounou S, Dumais N, Tremblay MJ. Attachment of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) particles bearing host-encoded B7-2 proteins leads to nuclear factor-kappa B- and nuclear factor of activated T cells-dependent activation of HIV-1 long terminal repeat transcription. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(9):6359–6369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm A, Nielsen SJ, Miska EA, McCance DJ, Reid JL, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. The E7 oncoprotein associates with Mi2 and histone deacetylase activity to promote cell growth. Embo J. 1999;18(9):2449–2458. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cismasiu VB, Adamo K, Gecewicz J, Duque J, Lin Q, Avram D. BCL11B functionally associates with the NuRD complex in T lymphocytes to repress targeted promoter. Oncogene. 2005;24(45):6753–6764. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cismasiu VB, Ghanta S, Duque J, Albu DI, Chen HM, Kasturi R, Avram D. BCL11B participates in the activation of IL2 gene expression in CD4+ T lymphocytes. Blood. 2006;108(8):2695–2702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JJ, Romerio F, Sun JM, Volker JL, Galvin KM, Davie JR, Shi Y, Hansen U, Margolis DM. The human factors YY1 and LSF repress the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat via recruitment of histone deacetylase 1. J Virol. 2000;74(15):6790–6799. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6790-6799.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish AG, Beverley PC, Clapham PR, Crawford DH, Greaves MF, Weiss RA. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature. 1984;312(5996):763–767. doi: 10.1038/312763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Arellano ER, Soriano V, Holguin A. Genetic analysis of regulatory, promoter, and TAR regions of LTR sequences belonging to HIV type 1 Non-B subtypes. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21(11):949–954. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarchi F, D'Agaro P, Falaschi A, Giacca M. In vivo footprinting analysis of constitutive and inducible protein-DNA interactions at the long terminal repeat of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67(12):7450–7460. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7450-7460.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumais N, Bounou S, Olivier M, Tremblay MJ. Prostaglandin E(2)-mediated activation of HIV-1 long terminal repeat transcription in human T cells necessitates CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) binding sites in addition to cooperative interactions between C/EBPbeta and cyclic adenosine 5'-monophosphate response element binding protein. J Immunol. 2002;168(1):274–282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duus KM, Miller ED, Smith JA, Kovalev GI, Su L. Separation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication from nef-mediated pathogenesis in the human thymus. J Virol. 2001;75(8):3916–3924. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3916-3924.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ego T, Ariumi Y, Shimotohno K. The interaction of HTLV-1 Tax with HDAC1 negatively regulates the viral gene expression. Oncogene. 2002;21(47):7241–7246. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita N, Jaye DL, Kajita M, Geigerman C, Moreno CS, Wade PA. MTA3, a Mi-2/NuRD complex subunit, regulates an invasive growth pathway in breast cancer. Cell. 2003;113(2):207–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita N, Wade PA. Use of bifunctional cross-linking reagents in mapping genomic distribution of chromatin remodeling complexes. Methods. 2004;33(1):81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JA, Wu FK, Mitsuyasu R, Gaynor RB. Interactions of cellular proteins involved in the transcriptional regulation of the human immunodeficiency virus. Embo J. 1987;6(12):3761–3770. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02711.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor R. Cellular transcription factors involved in the regulation of HIV-1 gene expression. Aids. 1992;6(4):347–363. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199204000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor RB. Regulation of HIV-1 gene expression by the transactivator protein Tat. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;193:51–77. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78929-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giffin MJ, Stroud JC, Bates DL, von Koenig KD, Hardin J, Chen L. Structure of NFAT1 bound as a dimer to the HIV-1 LTR kappa B element. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10(10):800–806. doi: 10.1038/nsb981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene WC. Regulation of HIV-1 gene expression. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:453–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Margolis DM. Counterregulation of chromatin deacetylation and histone deacetylase occupancy at the integrated promoter of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) by the HIV-1 repressor YY1 and HIV-1 activator Tat. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(9):2965–2973. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.9.2965-2973.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Ylisastigui L, Margolis DM. The regulation of HIV-1 gene expression: the emerging role of chromatin. DNA Cell Biol. 2002;21(10):697–705. doi: 10.1089/104454902760599672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson AJ, Zou X, Calame KL. C/EBP proteins activate transcription from the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat in macrophages/monocytes. J Virol. 1995;69(9):5337–5344. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5337-5344.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey WF, Kimura H. Perivascular microglial cells of the CNS are bone marrow-derived and present antigen in vivo. Science. 1988;239(4837):290–292. doi: 10.1126/science.3276004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiebenthal-Millow K, Greenough TC, Bretttler DB, Schindler M, Wildum S, Sullivan JL, Kirchhoff F. Alterations in HIV-1 LTR promoter activity during AIDS progression. Virology. 2003;317(1):109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeang KT, Shank PR, Kumar A. Transcriptional activation of homologous viral long terminal repeats by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 or the human T-cell leukemia virus type I tat proteins occurs in the absence of de novo protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(21):8291–8295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeeninga RE, Hoogenkamp M, Armand-Ugon M, de Baar M, Verhoef K, Berkhout B. Functional differences between the long terminal repeat transcriptional promoters of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes A through G. J Virol. 2000;74(8):3740–3751. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3740-3751.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamine J, Subramanian T, Chinnadurai G. Sp1-dependent activation of a synthetic promoter by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(19):8510–8514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao SY, Calman AF, Luciw PA, Peterlin BM. Anti-termination of transcription within the long terminal repeat of HIV-1 by tat gene product. Nature. 1987;330(6147):489–493. doi: 10.1038/330489a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaver B, Berkhout B. Comparison of 5' and 3' long terminal repeat promoter function in human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1994;68(6):3830–3840. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3830-3840.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotman ME, Kim S, Buchbinder A, DeRossi A, Baltimore D, Wong-Staal F. Kinetics of expression of multiply spliced RNA in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of lymphocytes and monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(11):5011–5015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XF, Bagchi MK. Recruitment of distinct chromatin-modifying complexes by tamoxifen-complexed estrogen receptor at natural target gene promoters in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(15):15050–15058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusic M, Marcello A, Cereseto A, Giacca M. Regulation of HIV-1 gene expression by histone acetylation and factor recruitment at the LTR promoter. Embo J. 2003;22(24):6550–6561. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marban C, Redel L, Suzanne S, Van Lint C, Lecestre D, Chasserot-Golaz S, Leid M, Aunis D, Schaeffer E, Rohr O. COUP-TF interacting protein 2 represses the initial phase of HIV-1 gene transcription in human microglial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(7):2318–2331. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Marban C, Suzanne S, Dequiedt F, de Walque S, Redel L, Van Lint C, Aunis D, Rohr O. Recruitment of chromatin-modifying enzymes by CTIP2 promotes HIV-1 transcriptional silencing. Embo J. 2007;26(2):412–423. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzio G, Giacca M. Chromatin control of HIV-1 gene expression. Genetica. 1999;106(1–2):125–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1003797332379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morner A, Bjorndal A, Albert J, Kewalramani VN, Littman DR, Inoue R, Thorstensson R, Fenyo EM, Bjorling E. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) isolates, like HIV-1 isolates, frequently use CCR5 but show promiscuity in coreceptor usage. J Virol. 1999;73(3):2343–2349. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2343-2349.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukerjee R, Sawaya BE, Khalili K, Amini S. Association of p65 and C/EBPbeta with HIV-1 LTR modulates transcription of the viral promoter. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100(5):1210–1216. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi MH, Nowak P, Andersson J, Sonnerborg A, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Vahlne A. Intracellular high mobility group B1 protein (HMGB1) represses HIV-1 LTR-directed transcription in a promoter- and cell-specific manner. Virology. 2003;314(1):179–189. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00453-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi MH, Schwartz S, Sonnerborg A, Vahlne A. Long terminal repeat promoter/enhancer activity of different subtypes of HIV type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15(14):1293–1303. doi: 10.1089/088922299310197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekhai S, Jeang KT. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of HIV-1 gene expression: role of cellular factors for Tat and Rev. Future Microbiol. 2006;1:417–426. doi: 10.2217/17460913.1.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira LA, Bentley K, Peeters A, Churchill MJ, Deacon NJ. A compilation of cellular transcription factor interactions with the HIV-1 LTR promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(3):663–668. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.3.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins ND, Edwards NL, Duckett CS, Agranoff AB, Schmid RM, Nabel GJ. A cooperative interaction between NF-kappa B and Sp1 is required for HIV-1 enhancer activation. Embo J. 1993;12(9):3551–3558. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolin PL, Prystowsky MB. The kinetics of vimentin RNA and protein expression in interleukin 2-stimulated T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(9):5870–5875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radkov SA, Touitou R, Brehm A, Rowe M, West M, Kouzarides T, Allday MJ. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. J Virol. 1999;73(7):5688–5697. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5688-5697.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr O, Lecestre D, Chasserot-Golaz S, Marban C, Avram D, Aunis D, Leid M, Schaeffer E. Recruitment of Tat to heterochromatin protein HP1 via interaction with CTIP2 inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in microglial cells. J Virol. 2003;77(9):5415–5427. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5415-5427.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr O, Schwartz C, Hery C, Aunis D, Tardieu M, Schaeffer E. The nuclear receptor chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor interacts with HIV-1 Tat and stimulates viral replication in human microglial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(4):2654–2660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C, Catez P, Rohr O, Lecestre D, Aunis D, Schaeffer E. Functional interactions between C/EBP, Sp1, and COUP-TF regulate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gene transcription in human brain cells. J Virol. 2000;74(1):65–73. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.65-73.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan PL, Sheline CT, Cannon K, Voz ML, Pazin MJ, Kadonaga JT, Jones KA. Activation of the HIV-1 enhancer by the LEF-1 HMG protein on nucleosome-assembled DNA in vitro. Genes Dev. 1995;9(17):2090–2104. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.17.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SD, Shatsky M, Cohen PS, Warnke R, Link MP, Glader BE. Monoclonal antibody and enzymatic profiles of human malignant T-lymphoid cells and derived cell lines. Cancer Res. 1984;44(12 Pt 1):5657–5660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Opijnen T, Jeeninga RE, Boerlijst MC, Pollakis GP, Zetterberg V, Salminen M, Berkhout B. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes have a distinct long terminal repeat that determines the replication rate in a host-cell-specific manner. J Virol. 2004;78(7):3675–3683. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3675-3683.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi Y, Inoue J, Takahashi Y, Matsuki A, Kosugi-Okano H, Shinbo T, Mishima Y, Niwa O, Kominami R. Homozygous deletions and point mutations of the Rit1/Bcl11b gene in gamma-ray induced mouse thymic lymphomas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003a;301(2):598–603. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)03069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi Y, Watanabe H, Inoue J, Takeda N, Sakata J, Mishima Y, Hitomi J, Yamamoto T, Utsuyama M, Niwa O, Aizawa S, Kominami R. Bcl11b is required for differentiation and survival of alphabeta T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2003b;4(6):533–539. doi: 10.1038/ni927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Wong J, Moreno GT, Young MK, Cote J, Wang W. NURD, a novel complex with both ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling and histone deacetylase activities. Mol Cell. 1998;2(6):851–861. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Ng HH, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Bird A, Reinberg D. Analysis of the NuRD subunits reveals a histone deacetylase core complex and a connection with DNA methylation. Genes Dev. 1999;13(15):1924–1935. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]