Summary

Neural crest stem cells (NCSCs) persist in peripheral nerves throughout late gestation but their function is unknown. Current models of nerve development only consider the generation of Schwann cells from neural crest, but the presence of NCSCs raises the possibility of multilineage differentiation. We performed Cre-recombinase fate mapping to determine which nerve cells are neural crest derived. Endoneurial fibroblasts, in addition to myelinating and non-myelinating Schwann cells, were neural crest derived, whereas perineurial cells, pericytes and endothelial cells were not. This identified endoneurial fibroblasts as a novel neural crest derivative, and demonstrated that trunk neural crest does give rise to fibroblasts in vivo, consistent with previous studies of trunk NCSCs in culture. The multilineage differentiation of NCSCs into glial and non-glial derivatives in the developing nerve appears to be regulated by neuregulin, notch ligands, and bone morphogenic proteins, as these factors are expressed in the developing nerve, and cause nerve NCSCs to generate Schwann cells and fibroblasts, but not neurons, in culture. Nerve development is thus more complex than was previously thought, involving NCSC self-renewal, lineage commitment and multilineage differentiation.

Keywords: Neural crest stem cell, Peripheral nerve development, Fate-mapping

Introduction

Current models of peripheral nerve development address the generation of Schwann cells from restricted neural crest progenitors. The undifferentiated neural crest cells in the embryonic day 14 (E14) peripheral nerve have been described as ‘Schwann cell precursors’ that undergo overt differentiation to Schwann cells over the next few days of development (Jessen et al., 1994). These Schwann cell precursors were assumed to be glial-restricted (Jessen and Mirsky, 1992; Mirsky and Jessen, 1996). We have more recently discovered that multipotent neural crest stem cells (NCSCs) persist in the E14-E17 peripheral nerve (Bixby et al., 2002; Morrison et al., 1999). The persistence of NCSCs raises the question of whether the neural crest gives rise to additional nerve cell types in addition to Schwann cells. If so, nerve development is much more complex than was previously thought, involving NCSC self-renewal (Morrison et al., 1999), lineage commitment and multilineage differentiation.

Circumstantial evidence suggests that NCSCs give rise to more than just Schwann cells in developing nerves. Culture of single cells from the developing sciatic nerve yields several different types of colonies, including multilineage NCSC colonies (containing neurons, Schwann cells and myofibroblasts), colonies that contain only Schwann cells and myofibroblasts, colonies that contain only Schwann cells, and colonies that contain only myofibroblasts (Morrison et al., 1999). This raises the possibility that NCSCs give rise to restricted progenitors within the nerve, which in turn differentiate into Schwann cells and fibroblasts. If single sciatic nerve NCSCs are subcloned after proliferating in culture they generate additional NCSCs, as well as colonies that contain only Schwann cells and myofibroblasts, colonies that contain only Schwann cells, and colonies that contain only myofibroblasts (Morrison et al., 1999). Nerve NCSCs may undergo progressive restrictions in vitro and in vivo to form both Schwann cells and fibroblasts.

Recent fate-mapping studies in vivo have raised questions about whether the fate of neural progenitors in vivo can be accurately predicted based on their function in culture (Gabay et al., 2003). Because culture conditions often dysregulate progenitor patterning in an unphysiological way (Anderson, 2001), neural progenitors might readily generate cell types in culture that they would never generate in vivo. In this regard, the ability of nerve (and other trunk) NCSCs to generate myofibroblasts in culture (Morrison et al., 1999) appeared to contrast with the failure to observe a contribution of trunk neural crest cells to fibroblast-type derivatives in vivo (Le Douarin, 1982). This raises the question of whether the potential of nerve NCSCs to make fibroblasts in culture is ever expressed in vivo. More generally, it is important to begin to assess the fate of neural stem cell populations during normal development, in addition to examining the developmental potential of these cells in culture.

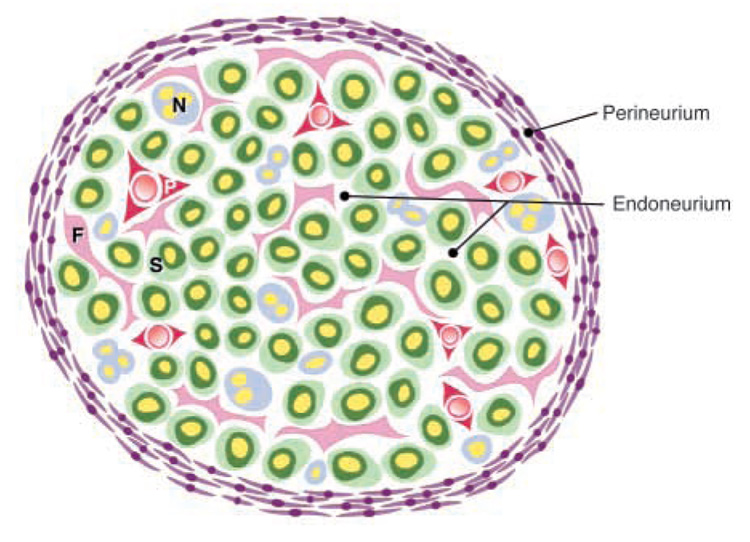

If NCSCs differentiate into both Schwann cells and fibroblasts within nerves, what is the ultimate fate of the fibroblasts? There are a variety of cell types present within peripheral nerves in addition to Schwann cells, including perineurial cells, pericytes and endoneurial fibroblasts (Fig. 1). The embryonic origins of perineurial cells, pericytes and endoneurial fibroblasts are uncertain and controversial. Based on morphological criteria, some investigators have argued that perineurial cells are neural crest derived (Hirose et al., 1986), while others have argued they are not (Low, 1976). The observation that embryonic fibroblasts from the cranial periosteum could form perineurial cells in culture supported a mesodermal origin for these cells (Bunge et al., 1989). Although pericytes have been presumed to be mesodermally derived, the vascular smooth muscle around the cardiac outflow tracts is neural crest derived (Jiang et al., 2000; Kirby and Waldo, 1995), and so some vascular smooth muscle cells in other locations might also be neural crest derived. Little is known about the properties of endoneurial fibroblasts or their embryonic origin.

Fig. 1.

Peripheral nerve anatomy. Perineurial cells form a sheath around the nerve (the perineurium; purple) that separates the endoneurial environment from the epineurial environment (outside the nerve bundle). Within the endoneurium, there are Schwann cells that myelinate axons (S; green cells surrounding yellow axons), non-myelinating Schwann cells that are associated with multiple axons (N; blue cells), endoneurial fibroblasts (F; pink cells), and pericytes (P; red) that surround small blood vessels. A single layer of endothelial cells also surrounds the blood vessels (not shown). Perineurial cells are distinguished based on their position and their characteristic flattened morphology. Pericytes are distinguished by their expression of SMA. Schwann cells are distinguished by their association with axons, their expression of glial markers such as S100β, and their basal lamina. Endoneurial fibroblasts lack a basal lamina, often have long interdigitating processes, are not associated with axons, and fail to express SMA or S100β in vivo.

We have used Cre-recombinase fate mapping (Chai et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2000; Yamauchi et al., 1999; Zinyk et al., 1998) to examine which cells in peripheral nerve are neural crest derived (see Fig. S1 in supplementary material). Nerve sheath perineurial cells, vascular pericytes and endothelial cells were not neural crest derived. By contrast, endoneurial fibroblasts were neural crest derived, identifying a previously unrecognized, non-glial neural crest-derivative. Both Schwann cells and endoneurial fibroblasts appeared to arise from a common desert hedgehog (Dhh)-expressing progenitor population within the nerve environment, and nerve NCSCs strongly expressed Dhh, suggesting that nerve NCSCs give rise to both Schwann cells and endoneurial fibroblasts. To begin to identify the signals within the nerve environment that promote multilineage differentiation from NCSCs, we found that the combination of neuregulin, Delta and Bmp4 promoted the generation of Schwann cells and myofibroblasts, but not neurons, from nerve NCSCs in culture. Moreover, in the presence of these factors, cells with myofibroblast morphology tended to express Thy1, as well as other markers of endoneurial fibroblasts. This suggests that nerve development is substantially more complicated than was previously thought, as NCSCs self-renew, undergo restriction to form non-neuronal progenitors, then commit and differentiate into both Schwann cell and endoneurial fibroblast lineages.

Materials and methods

X-gal staining of embryos

E13.5 embryos were dissected in D-PBS then fixed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde, 1.25 mM EGTA and 2mM MgCl2 in PBS for 25 minutes on a rocker. Embryos were rinsed for 3×15 minutes in wash buffer (0.02% Igepal and 2 mM MgCl2 in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer), then incubated in 2 mM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactoside (X-gal; Molecular Probes, Eugene OR, USA), 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide and 5 mM potassium ferricyanide in wash buffer at 37°C for 8–16 hours on a rocker. Embryos were rinsed for 3×15 minutes in wash buffer and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde before imaging. Embryos were then embedded in OCT and cryosectioned. Sections were post-stained in X-gal as well. For postnatal tissues, the tissues were first dissected out of the pups, and then stained and sectioned using similar methods.

Tissue preparation for light and electron microscopy

P11 mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and perfused through the heart with 0.25% glutaraldehyde in D-PBS. Sciatic nerves were dissected and fixed for an additional 15–20 minutes in 0.25% glutaraldehyde. Nerves were then rinsed twice in PBS and stained in either 2 mM X-gal (for light microscopy) or 2 mM 5-bromo-3-indolyl-β-D-galactoside (bluo-gal; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad CA, USA; for electron microscopy). X-gal and bluo-gal were dissolved in D-PBS with 20 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 20 mM potassium ferricyanide, 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.3% Triton-X, as previously described (Weis et al., 1991). The staining was done for 6–10 hours at 37°C. For light microscopy, nerves were removed from the X-gal buffer, rinsed in PBS, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour, cryoprotected in 15% sucrose, and embedded in gelatin. Frozen sections were cut on a Leica 3050S cryostat. For electron microscopy, nerves were removed from the bluo-gal buffer, rinsed in PBS, then postfixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4°C. Nerves were then rinsed in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer and refixed in 1% OsO4 (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington PA, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. The nerves were rinsed in sodium phosphate buffer then dehydrated in an ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 95% and 100% ethanol) before infiltrating and embedding in Spurr resin (Bozzola and Russell, 1992). Semithin sections (1 µm) were cut with a glass knife. Thin sections (70 nm) were cut with a diamond knife and examined without further staining to facilitate visualization of the bluo-gal crystals. Some sections were stained with uranyl acetate to reveal the basal lamina. Note that the presence of the Triton-X detergent in the bluo-gal buffer resulted in poor preservation of myelin sheaths. However, the Triton-X was required for effective bluo-gal staining.

Immunohistochemistry for confocal microscopy

Sciatic nerves were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, cryoprotected, and embedded in gelatin. Cross-sections of P11 sciatic nerves were cryosectioned at 10–12 µm thickness, collected on pre-cleaned superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific, Chicago IL, USA), dried for 1–2 hours and stored at −20°C. Slides were allowed to thaw, then were washed in PBS for 5 minutes, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, rinsed for 3×10 minutes in PBS, and blocked in 10% goat serum/0.2% Triton-X in PBS for 1 hour. Slides were incubated in primary antibodies in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. We used rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (1:1000; 5′-3′, Boulder CO, USA), with anti-smooth muscle action (1:200; Sigma, St Louis MO, USA) and anti-PECAM (1:300; Pharmingen, San Diego CA, USA), or anti-S100β (1:1000; Sigma). Slides were washed for 4×15 minutes in 2% goat serum/0.2% Triton-X in PBS then incubated with secondary antibodies diluted 1:200 in blocking solution for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Slides were washed for 4×15 minutes in the dark, then mounted in Prolong anti-fade (Molecular Probes) and analyzed on a Zeiss 510 laser confocal microscope.

Cell culture

Timed pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington MA, USA). E14.5 rat gut and sciatic nerve NCSCs were isolated by flow cytometry and cultured under standard conditions, as previously described (Bixby et al., 2002). Briefly, dissociated cells from the sciatic nerve and gut were stained with antibodies against the neurotrophin receptor p75 (192Ig) and α4 integrin (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose CA, USA). The p75+α4 + population was sorted into ‘standard medium’ at clonal density. The standard culture medium contained DMEM-low (Gibco, product 11885-084, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 15% chick embryo extract (Stemple and Anderson, 1992), 20 ng/ml recombinant human bFGF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN, USA), 1% N2 supplement (Gibco), 2% B27 supplement (Gibco), 50 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, 35 mg/ml (110 nM) retinoic acid (Sigma), penicillin/streptomycin (Biowhittaker, Walkersville, MD, USA) and 20 ng/ml IGF1 (R&D Systems). Some cultures were supplemented with 50 ng/ml Bmp4 (R&D Systems), 65 ng/ml Nrg1 (gift of CeNeS Pharmaceuticals, Norwood MA, USA), and Delta-Fc or Fc. Note that Delta-Fc and Fc were prepared and added to culture as described previously (Morrison et al., 2000b). All cultures were maintained in gas-tight chambers (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar CA, USA) containing decreased oxygen levels, as previously described, to enhance the survival of NCSCs (Morrison et al., 2000a). After 6 or 14 days, cultures were fixed in acid ethanol (5% glacial acetic acid in 100% ethanol) for 20 minutes at −20°C, washed, blocked and triply labeled for peripherin (Chemicon AB1530; Temecula CA, USA), GFAP (Sigma G-3893) and alpha SMA (Sigma A-2547), as described (Shah et al., 1996).

E13.5 mouse sciatic nerves were dissected and dissociated from timed pregnant transgenic mice. Unfractionated cells were plated at clonal density and cultured under standard conditions. The medium for the culture of mouse cells was the same as the medium used for rat cells except that 3:5 mixture of Neurobasal(Gibco):DMEM was used instead of DMEM. Cultures were fixed with 0.25% glutaraldehyde for 5 minutes and stained with X-gal.

Results

Previous studies have used Wnt1-Cre to fate map neural crest derivatives in mice (Chai et al., 2000; Hari et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2000). We mated Wnt1-Cre with loxpRosa conditional reporter mice and systematically examined the β-galactosidase (β-gal) expression pattern in the trunk and hindlimbs of the progeny. No β-gal expression was observed in Wnt1-Cre−loxpRosa+ littermate controls (see Fig. S2A–D in supplementary material). Consistent with the previous studies (Hari et al., 2002; Jiang et al., 2000), we found extensive expression of β-gal in expected neural crest derivatives of Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ mice (see Fig. S2E–J in supplementary material), but not in non-neural crest derivates such as hematopoietic cells, endothelium, skeletal muscle, cartilage and epithelium (see Fig. S2E–J). These other tissues were capable of expressing the β-gal reporter, as they readily stained with X-gal in Rosa26 fetuses (that constitutively express β-gal) and in CMV-Cre+loxpRosa+ fetuses (CMV-Cre activates reporter expression in all cells) (see Fig. S2K–N in supplementary material).

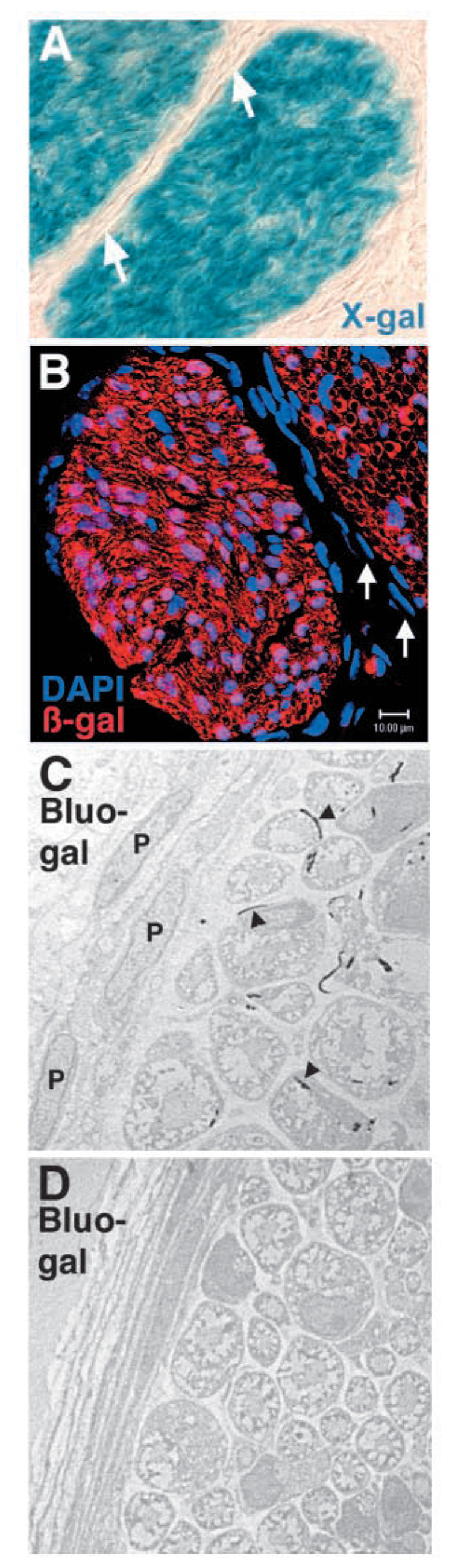

Perineurial cells are not neural crest derived

To explore the fates of neural crest cells in the developing nerve, we first examined whether perineurial cells in Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ pups expressed β-gal. Perineurial cells separate distinct bundles of nerve fibers within a nerve, and regulate diffusion and cell movement between the epineurial and endoneurial environments (Peters et al., 1976) (Fig. 1). We examined whether perineurial cells express β-gal in sciatic nerves by X-gal staining, immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy. In each case there was a distinct absence of β-gal expression in the perineurium (Fig. 2), despite the fact that perineurial cells readily expressed β-gal in positive control nerves from Rosa26 pups (see Fig. S3 in supplementary material) and CMV-Cre+loxpRosa+ pups (data not shown). Upon examining transverse sections through bluo-gal-stained nerves by electron microscopy (Weis et al., 1991), we rarely observed any bluo-gal staining within perineurial cells (see below), despite observing bluo-gal staining in the majority of Schwann cells within the same sections (Fig. 2C; Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Perineurial cells are not neural crest derived. Sciatic nerves from Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ mouse pups were dissected and processed for X-gal staining (A), immunohistochemistry (B), or electron microscopy (C,D), at either postnatal day 3 (A) or 11 (B–D). According to each technique the perineurial cells failed to express β-gal and therefore were not neural crest derived. Sections through X-gal stained (A) or anti-β-gal antibody stained (B) nerves consistently exhibited strong staining throughout the endoneurial space, but the flattened layers of perineurial cells that distinguish different bundles of axons were notable for their lack of X-gal or anti-β-gal antibody staining (arrows, A,B). We also failed to observe X-gal staining in perineurial cells from P0-Cre+β-actin-lacZ+ mice or Wnt1-Cre+β-actin-lacZ+ mice (data not shown). Note that the red fluorescent cell in the perineurial layer (bottom right corner; B) was an autofluorescent blood cell within a blood vessel (see Fig. S4 in supplementary material). Bluo-gal forms an electron dense precipitate that is visible as small black crystals (arrowheads, C) by electron microscopy after digestion by β-galactosidase (Weis et al., 1991). Bluo-gal staining was consistently absent from perineurial cells (P; panel C), but was visible in most Schwann cells (to the right of the perineurial cells in panel C). The myelin sheaths within the Schwann cells appear light and fragmented because bluo-gal staining required fixation conditions that did not effectively preserve myelin. Note the lack of bluo-gal staining in a nerve section from a control littermate (D).

Table 1.

Frequency of neural crest-derived (β-gal expressing, bluo-gal+) Schwann cells, endoneurial fibroblasts, and perineurial cells by electron microscopic examination of bluo-gal-stained sciatic nerves from P11 Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ pups

| Total cells examined | Bluo-gal+ by electron microscopy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Myelinating Schwann cells | With nuclei visible | 321 | 95.3% |

| Only processes visible | 2832 | 61.4% | |

| Non-myelinating Schwann cells | With nuclei visible | 135 | 87.4% |

| Only processes visible | 567 | 68.3% | |

| Endoneurial fibroblasts | 219 | 86.3% | |

| Perineurial cells | 180 | 3.3% |

The data represent sections derived from five mice in three independent experiments. Sciatic nerves from five littermate control mice (Wnt1-Cre−loxpRosa+ were also examined in detail by electron microscopy to determine whether there was any background bluo-gal staining. In these control sections, 117 non-myelinating Schwann cells, 693 myelinating Schwann cells, 46 fibroblasts and 73 perineurial cells were examined, but none exhibited detectable bluo-gal staining.

After examining many fields of view from multiple sections of multiple nerves by electron microscopy, a total of six perineurial cells out of 180 examined appeared to be labeled by bluo-gal (Table 1). However, in each case the labeling was questionable, and not as distinct as that observed among Schwann cells or endoneurial fibroblasts (see below). In five out of six cases, the potentially bluo-gal-positive perineurial cells were present at the interface of the perineurium and the endoneurium. Although it is possible that a minor subpopulation of perineurial cells on the endoneurial surface of the perineurium is neural crest derived, the data suggest that almost all, if not all, perineurial cells are derived from sources other than the neural crest.

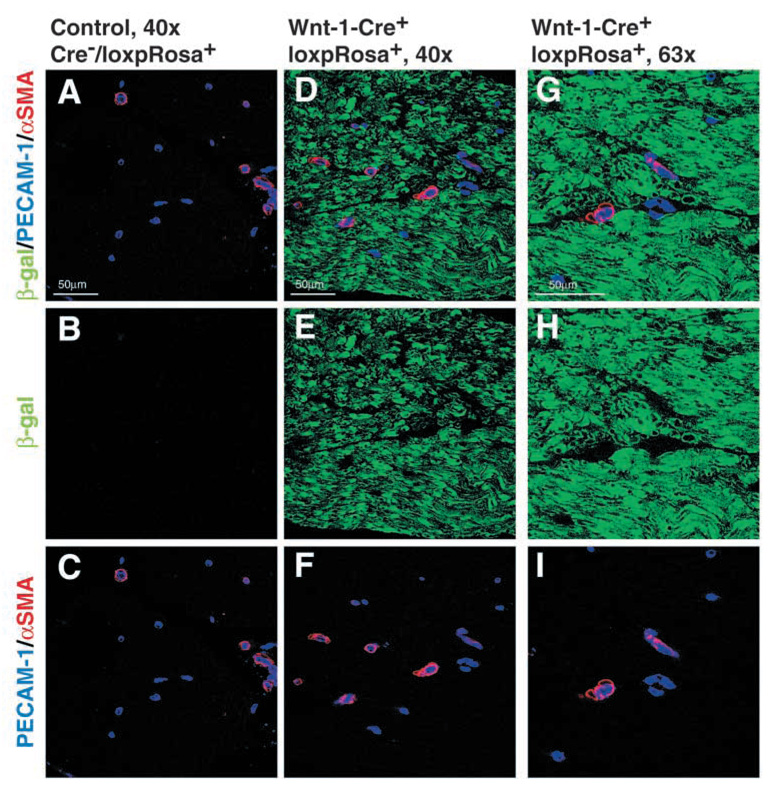

Pericytes and endothelial cells are not neural crest derived

To assess whether the pericytes and endothelial cells that are present around small blood vessels in the endoneurium (Fig. 1) were neural crest derived, we performed immunohistochemistry using antibodies against the endothelial marker PECAM1, the pericyte marker SMA and β-gal in sciatic nerve sections from Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ pups. Neither PECAM1+ endothelial cells nor SMA+ pericytes co-labeled with antibodies against β-gal, despite widespread β-gal expression by other cells within the nerve (Fig. 3). Pericytes expressed β-gal in nerve sections from positive control Rosa26 pups (see Fig. S3 in supplementary material), and endothelial cells from Rosa26 mice widely express β-gal (Jackson et al., 2001). This indicates that pericytes and endothelial cells within the sciatic nerve are not neural crest derived.

Fig. 3.

Pericytes and endothelial cells within the sciatic nerve are not neural crest derived. Sciatic nerves were dissected from P11 Wnt1-Cre−loxpRosa+ and Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ pups, and immunohistochemically stained for β-gal (green), the endothelial marker PECAM1 (blue), and the pericyte marker SMA (red). Although most cells in the endoneurial space were β-gal+, both the PECAM1+ endothelial cells and the SMA+ pericytes consistently failed to co-label with β-gal.

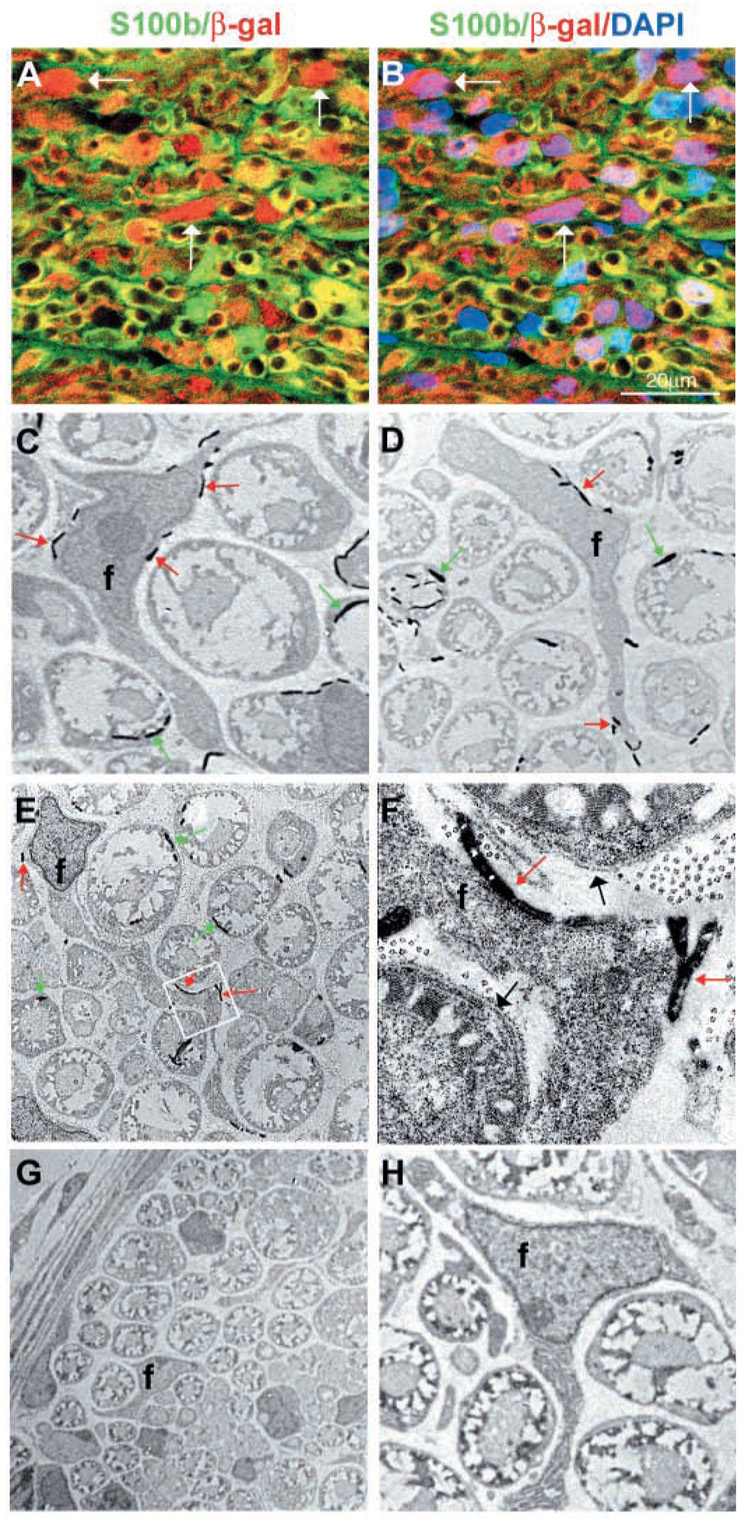

Endoneurial fibroblasts are neural crest derived

Within fully developed peripheral nerves, S100β is expressed by Schwann cells but not by endoneurial fibroblasts (Hirose et al., 1986; Jaakkola et al., 1989; Peltonen et al., 1987; Siironen et al., 1992). We therefore stained sciatic nerve sections from P11 Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ pups with antibodies against S100β and β-gal. The sections contained S100β−β-gal+ endoneurial cells that were not associated with axons (Fig. 4A,B), in addition to S100β+β-gal+ cells that were associated with axons (Schwann cells). The S100β− cells appeared to correspond to endoneurial fibroblasts, as no other S100β− cell type is prevalent enough within the sciatic nerve to account for these cells. Their expression of β-gal indicated that they were neural crest derived.

Fig. 4.

Endoneurial fibroblasts are neural crest derived. Sciatic nerves were dissected from P11 Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ pups and processed for immunohistochemistry (A,B), or electron microscopy (C–H). Nerves were stained with antibodies against β-gal (red) to identify neural crest-derived cells, and S100β (green) to identify Schwann cells. The same field of view is shown in A and B, with DAPI staining (blue) added to panel B. In addition to β-gal+S100β+ glia (green or yellow), we also observed β-gal+S100β− endoneurial cells (white arrows) that were neither associated with axons nor blood vessels. By electron microscopy, we consistently observed endoneurial fibroblasts stained with bluo-gal, indicating neural crest-derivation (C–F). (C,D) Bluo-gal-stained endoneurial fibroblasts (f), surrounded by myelinating Schwann cells, most of which are also stained with bluo-gal. Red arrows indicate bluo-gal crystals in the fibroblast; green arrows indicate bluo-gal crystals in Schwann cells. (E) A lower magnification image of a large bluo-gal stained fibroblast, with a very long process, surrounded by Schwann cells. The boxed area is shown at a higher magnification in F. Note the presence of a basal lamina around the Schwann cells (black arrows), but the lack of a basal lamina around the fibroblast process. (G,H) Low and high power images of sections through control littermates that lack any bluo-gal staining in perineurial cells (G), Schwann cells (G,H) or fibroblasts (H).

To definitively assess whether endoneurial fibroblasts are neural crest derived, we examined bluo-gal-stained sciatic nerve sections by electron microscopy. Endoneurial fibroblasts are defined based on several characteristics that can be observed by electron microscopy, including their endoneurial localization, lack of myelin, failure to associate with axons, lack of a basal lamina, and long angular processes (Peters et al., 1976). In particular, the lack of a basal lamina around endoneurial fibroblasts definitively distinguishes these cells from Schwann cells, perineurial cells and pericytes, which do have a basal lamina. We found that endoneurial fibroblasts identified by electron microscopy were consistently bluo-gal stained (Fig. 4C–F). Of 219 fibroblasts observed by electron microscopy, 86% were bluo-gal+ (Table 1). As this is a similar rate of bluo-gal+ staining to that observed among Schwann cells, we conclude that all or nearly all endoneurial fibroblasts in vivo are neural crest derived.

NCSCs undergo multilineage differentiation within the nerve environment in vivo

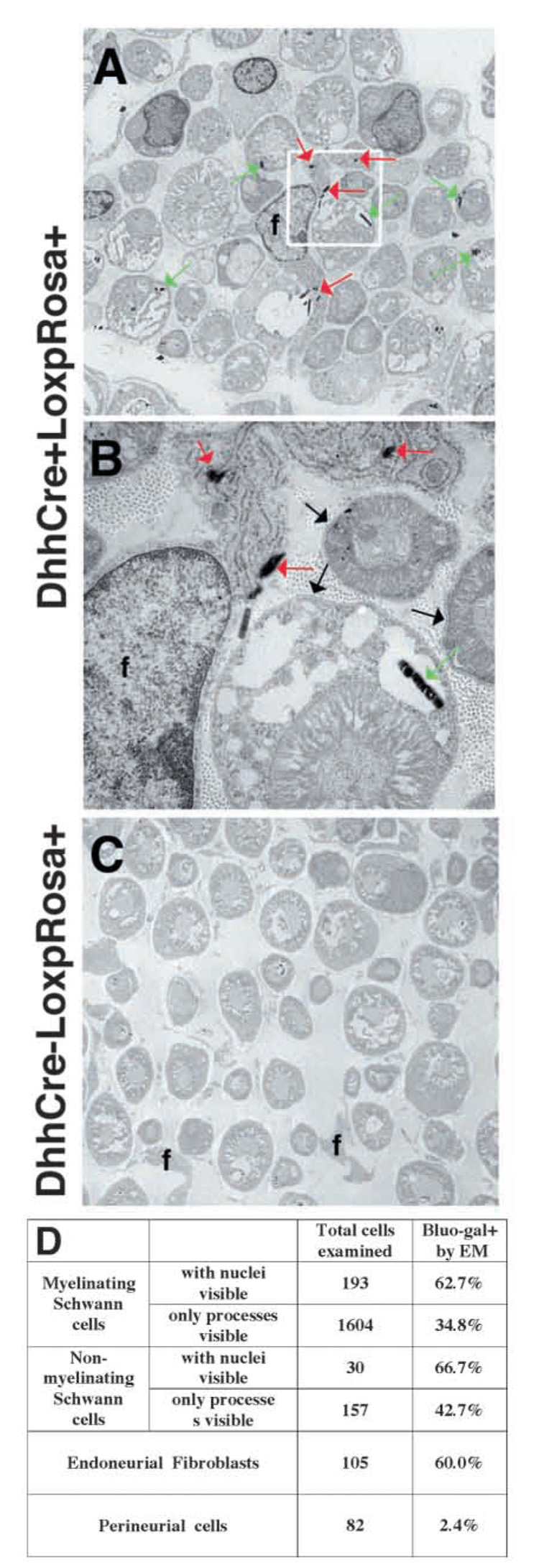

The data above raise the possibility that NCSCs differentiate into Schwann cells and endoneurial fibroblasts after migrating into the developing nerve. However, it remains possible based on the in vivo fate mapping experiments that endoneurial fibroblasts arise from a neural crest lineage that is independent of NCSCs, or that segregates prior to their migration into the nerve. To address these possibilities, we examined the fates of desert hedgehog (Dhh)-Cre expressing neural crest progenitors in vivo. Dhh is not expressed by migrating neural crest cells, or by neural crest progenitors that colonize ganglia, but is expressed in neural crest progenitors within developing peripheral nerves (Bitgood and McMahon, 1995; Jaegle et al., 2003; Parmantier et al., 1999). The Bluo-gal-staining pattern in Dhh-Cre+loxpRosa+ fetuses was consistent with the expected Dhh expression pattern, labeling only developing nerves (Jaegle et al., 2003) and not migrating neural crest cells (see Fig. S5 in supplementary material). We examined Bluo-gal-stained sections through the sciatic nerves of P11 Dhh-Cre+loxpRosa+ mice and littermate controls by electron microscopy (Fig. 5). Within postnatal nerves, we observed Bluo-gal staining in 60% of endoneurial fibroblasts and 63–67% of Schwann cells (Fig. 5A–D). Only 2.4% of perineurial cells appeared to label with Bluo-gal. These data indicate that Dhh-expressing neural crest progenitors within the nerve give rise to both Schwann cells and endoneurial fibroblasts, in remarkably similar proportions.

Fig. 5.

Dhh-Cre expressing progenitors give rise to endoneurial fibroblasts as well as Schwann cells in nerves. Sciatic nerves were dissected from P11 Dhh-Cre+LoxpRosa+ (A,B) pups as well as Dhh-Cre−LoxpRosa+ (C) littermate controls, processed for bluo-gal staining, and examined by electron microscopy. Endoneurial fibroblasts (f) were identified by their angular shape, long processes (A), and lack of a basal lamina (B). Red arrows indicate bluo-gal crystals in an endoneurial fibroblast; green arrows indicate bluo-gal crystals in Schwann cells. B shows the inset from panel A at a higher magnification to demonstrate the presence of a basal lamina on Schwann cells (black arrows), and the absence of a basal lamina on the fibroblast. Bluo-gal crystals were never observed in littermate control nerves (C). Endoneurial fibroblasts expressed β-gal at a similar frequency to Schwann cells, whereas perineurial cells were nearly all negative (D).

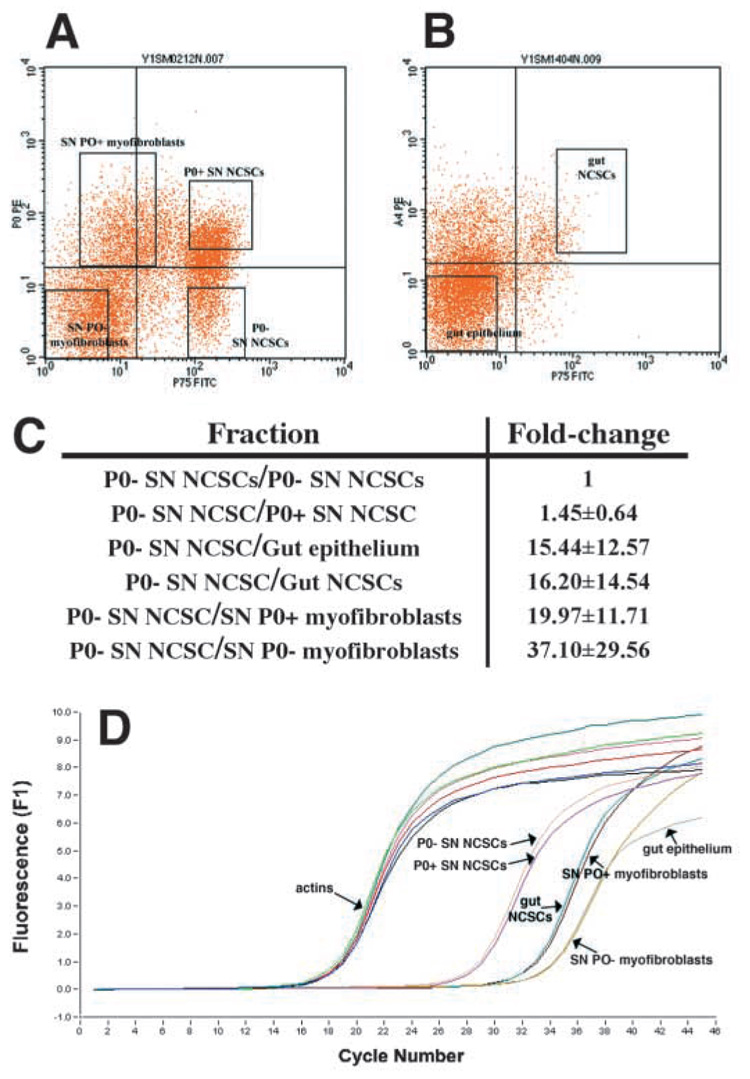

Markers to isolate different neural crest progenitor populations by flow-cytometry from developing mouse nerves do not yet exist. Therefore, to assess whether fibroblast progenitors and glial progenitors independently begin expressing Dhh within the nerve, or whether Dhh is expressed only by a common progenitor, we examined the levels of Dhh expression, by real-time RT-PCR, in the following progenitor populations isolated from rat sciatic nerve: p75+P0− NCSCs, p75+P0+ NCSCs, p75−P0+ fibroblast progenitors, and p75−P0− fibroblast progenitors (Fig. 6). As negative controls, we also examined Dhh expression in p75+α4+ gut NCSCs and p75−α4− gut epithelial progenitors, because no β-gal expression was observed within the guts of Dhh-Cre+loxpRosa+ fetuses (see Fig. S5D in supplementary material). We found that p75+P0− nerve NCSCs expressed the highest levels of Dhh, followed by slightly lower levels in p75+P0+ NCSCs (Fig. 6). By contrast, gut epithelial cells, and gut NCSCs expressed Dhh at approximately 15-fold lower levels. p75−P0+ and p75−P0− fibroblast progenitors expressed 20- to 40-fold lower levels of Dhh (Fig. 6C). Because no reporter gene expression was observed within the guts of Dhh-Cre+loxpRosa+ mice, this low level of Dhh expression appears to be inconsistent with reporter gene recombination within fibroblast-restricted progenitors. These data suggest that the only cells within the E14.5 nerve that express significant levels of Dhh are NCSCs. Therefore, the reporter gene is most likely recombined within Dhh-expressing NCSCs after they migrate into the nerve, and these cells probably give rise to restricted glial progenitors, as well as to fibroblast progenitors.

Fig. 6.

Dhh expression by progenitor populations in the developing nerve. We isolated p75+P0 − NCSCs (A; 83% of these cells formed multilineage colonies, and 6% formed colonies that contained myofibroblasts and glia in a clonal analysis), p75+P0 + NCSCs (A; 74% of these cells formed multilineage colonies, and 12% formed myofibroblasts and glia), p75−P0 + myofibroblast progenitors (A; 97% of these cells formed myofibroblast-only colonies) and p75−P0 − myofibroblast progenitors (A; 99% of these cells formed myofibroblast-only colonies) from E14.5 rat sciatic nerve (Morrison et al., 1999). Only small numbers of restricted glial progenitors (that form glial-only colonies in culture) are present in the E14.5 sciatic nerve, but the frequency of these cells increases from E15.5 to E17.5, as NCSCs undergo glial restriction (Morrison et al., 1999). As negative controls, we also isolated p75+α4+ gut NCSCs (B; 76% of these cells formed multilineage colonies) and p75−α4− gut epithelial progenitors (B; none of these cells gave rise to colonies that contained neural cells, although they did give rise to fibroblasts in culture). By quantitative (real-time) RT-PCR, we found that nerve p75+P0 − NCSCs expressed the highest levels of Dhh, followed by slightly lower levels in p75+P0 + NCSCs (1.45-fold lower), gut epithelial cells (15-fold lower), gut NCSCs (16-fold lower), and nerve myofibroblasts (20 to 40-fold lower) (C). As no reporter gene expression was observed within the intestines of Dhh-Cre+loxpRosa+ mice, the low level of Dhh expression in nerve myofibroblasts appears to be inconsistent with reporter gene activation within these cells. D shows a representative experiment in which cDNA was random primed and normalized based on β-actin content, and then Dhh expression levels were compared between samples. We confirmed that each reaction product was homogeneous based on the melting curve, and that a single product was generated of the expected size (data not shown). Sequencing of the Dhh band confirmed that the correct sequence had been amplified.

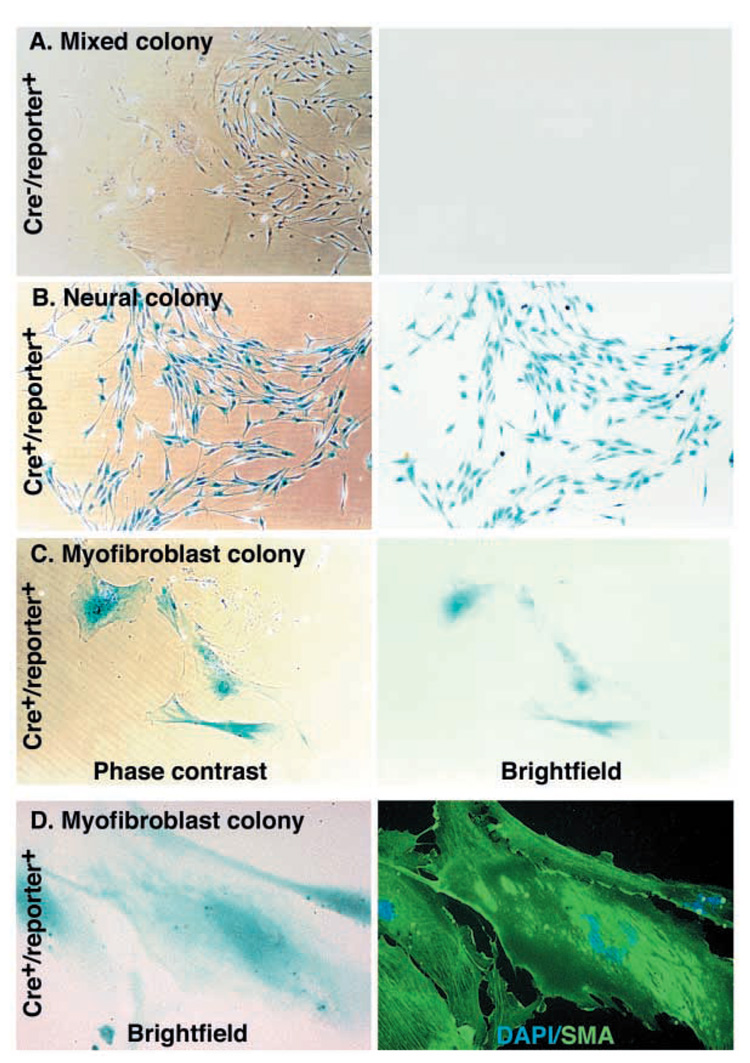

Some nerve progenitors that form myofibroblast colonies in culture are neural crest derived

To test whether some of the fibroblast progenitors from the developing nerve that form myofibroblast-only colonies in culture might be neural crest derived, we dissociated sciatic nerves from E13.5 Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ or Wnt1-Cre+β-actin-flox/stop-β-gal+ (Zinyk et al., 1998) mouse fetuses, and cultured them at clonal density. The mouse sciatic nerve cells formed three types of colonies: mixed colonies that contain neural (i.e. neuronal and glial) cells and myofibroblasts (Fig. 7A), neural colonies (Fig. 7B), and myofibroblast-only colonies (Fig. 7C,D). The myofibroblast-only colonies could be distinguished by their flat morphology (Fig. 7C), their SMA expression (Fig. 7D) and their failure to express p75 (not shown), just as was observed among rat myofibroblast-only colonies (Morrison et al., 1999). The neural colonies (that contained cells with the appearance and marker expression of neural crest progenitors or glia, but not myofibroblasts) could be distinguished based on their higher density, smaller angular cells (Fig. 7B), p75 expression and failure to express SMA (data not shown), just as was observed previously among rat neural progenitors from the sciatic nerve (Morrison et al., 1999).

Fig. 7.

Some myofibroblast progenitors are neural crest derived. Wnt1-Cre mice were mated with β-actin-flox/stop-β-gal conditional reporter mice. Sciatic nerves were dissected from the fetuses at E13.5, dissociated and cultured at clonal density. Some cells formed mixed colonies containing neural cells as well as myofibroblasts (A), whereas other colonies contained only neural cells (B), or only myofibroblasts (C). Neural cells were p75+ (not shown), had a characteristically spindly morphology, and grew in relatively dense colonies (B). Myofibroblasts were p75−SMA+, were characteristically large and flat, and grew in small, dispersed colonies (C,D). The cultures were stained with X-gal to identify neural crest-derived cells (blue product). Colonies from Cre−reporter+ littermate controls were never X-gal+ (A; Table 2), but neural colonies from Cre+reporter+ mice were usually X-gal+ (B; Table 2), as would be expected. Myofibroblast colonies from Cre+reporter+ mice were sometimes X-gal+, indicating neural crest derivation (C). Similar results were obtained using Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ mice, in which some nerve cells formed β-gal+SMA+ myofibroblast colonies (D; see Table 2 for quantification).

Virtually all the neural progenitors cultured from the sciatic nerves of Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ or Wnt1-Cre+β-actin-flox/stop-β-gal+ embryos expressed β-gal (Table 2, Fig. 7B), consistent with the strong X-gal staining previously observed within sections though nerves (see Fig. S2E–J in supplementary material). Twelve percent of myofibroblast-only progenitors also expressed β-gal, indicating that some of these progenitors were neural crest derived. In such colonies, all of the cells typically stained with X-gal (Fig. 7C). We never observed X-gal staining of cells cultured from littermate controls that lacked Cre and/or the reporter transgene (Fig. 7A, Table 2). These data suggest that the myofibroblast progenitors in sciatic nerve are heterogeneous, containing a subpopulation of neural crest-derived cells.

Table 2.

A minority of myofibroblast progenitors from the sciatic nerve is neural crest derived

| Mating | Genotype of pups | X-gal+ neural colonies | X-gal+ myofibroblast colonies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt1-Cre×loxpRosa | Littermate controls | 0±0% | 0±0% |

| Cre+, reporter+ | 98±6% | 12±10% | |

| Wnt1-Cre×β-actin-flox/stop-β-gal | Littermate controls | 0±0% | 0±0% |

| Cre+, reporter+ | 79±18% | 10±20% | |

| P0-Cre×β-actin-flox/stop-β-gal | Littermate controls | 0±0% | 0±0% |

| Cre+, reporter+ | 52±33% | 2±2% | |

| CMV-Cre×β-actin-flox/stop-β-gal | Littermate controls | 0±0% | 0±0% |

| Cre+, reporter+ | 83±24% | 88±10% |

Sciatic nerves were dissected from individual E13.5 pups, dissociated and cultured at clonal density under standard conditions (Morrison et al., 1999). After 5–6 days, the cultures were stained with X-gal, and the percentages of β-gal-expressing neural or myofibroblast colonies were counted. Because the CMV promoter is widely expressed in the early embryo, it serves as a positive control for reporter activation, demonstrating that the great majority of neural and myofibroblast progenitors were capable of expressing β-gal. Statistics represent mean±s.d. for at least three pups per treatment.

The β-actin-flox/stop-β-gal conditional reporter [β-gal expressed under the control of the β-actin promoter (Zinyk et al., 1998)] was less penetrant than the loxpRosa reporter, as a lower and more variable proportion of neural crest-derived cells expressed β-gal (data not shown). Nonetheless we obtained similar results. 79% of neural progenitors and 10% of myofibroblast-only progenitors expressed β-gal (Table 2). We also mated the β-actin conditional reporter with P0-Cre, which also specifically marks neural crest derivatives (Crone et al., 2003; Yamauchi et al., 1999). P0-Cre and the β-actin reporter led to the least efficient marking of neural crest-derived cells. Often only a minority of cells within nerves and ganglia stained with X-gal (data not shown). Nonetheless, we obtained qualitatively similar results, with 52% of neural colonies and 2% of myofibroblast colonies expressing β-gal (Table 1). Thus a minority of myofibroblast progenitors were neural crest derived irrespective of Cre or the reporter transgene used.

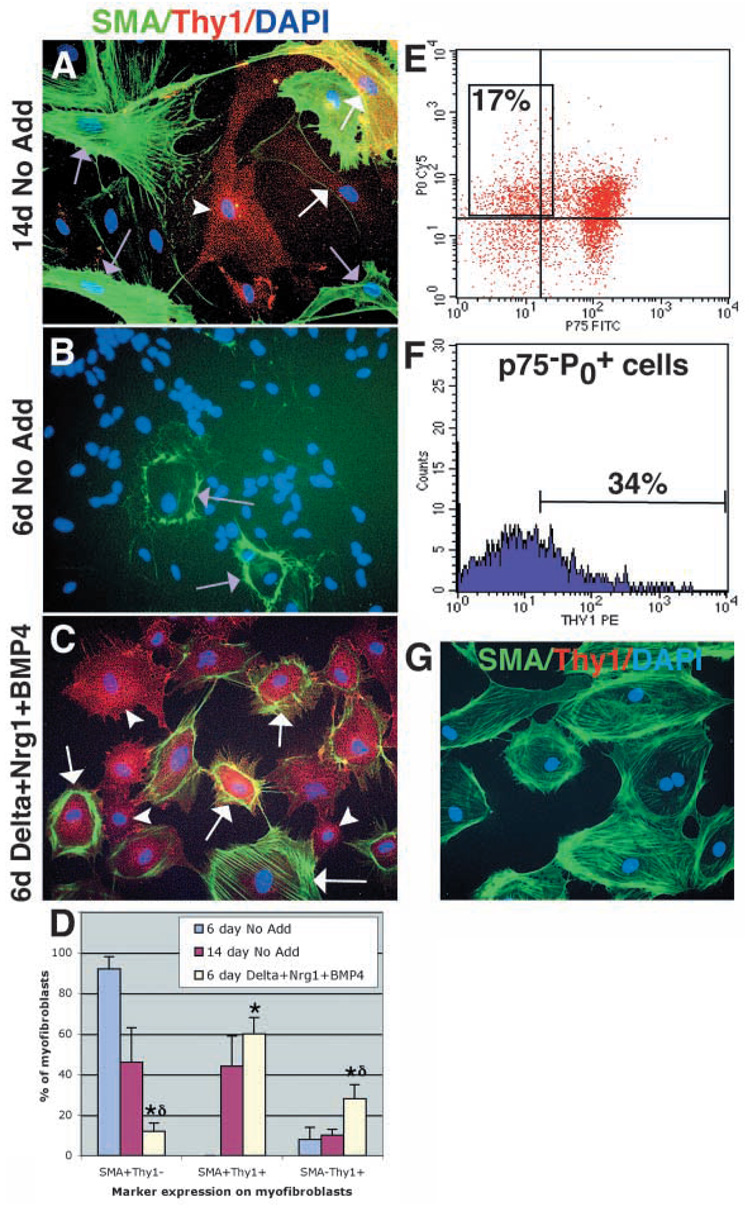

Common expression of Thy1 suggests a link between myofibroblasts in culture and endoneurial fibroblasts in vivo

The above experiments demonstrated that a small percentage of myofibroblast-committed progenitors that can be cultured from sciatic nerve are neural crest derived, and that endoneurial fibroblasts arise from the neural crest in vivo. These observations suggested that neural crest-derived cells that differentiate in vitro as myofibroblasts were fated to form endoneurial fibroblasts in vivo. However, the marker that we have used to identify myofibroblasts in culture, SMA (Fig. 7), is not expressed by endoneurial fibroblasts in vivo. Thus, we wondered whether myofibroblasts are capable of expressing markers of endoneurial fibroblasts. All myofibroblasts in culture expressed fibronectin, collagen and vimentin (data not shown), which are also expressed by endoneurial fibroblasts in vivo (Jaakkola et al., 1989; Peltonen et al., 1987). A more selective marker of nerve fibroblasts is Thy1 (Assouline et al., 1983; Brockes et al., 1979; Morris and Beech, 1984; Vroemen and Weidner, 2003). We found that although 46±17% (mean±s.d.) of the cells with myofibroblast morphology that arose within nerve NCSC colonies in 14-day standard cultures were SMA+Thy1−, a similar proportion (44±15%) were SMA+Thy1+, and 10±3% were SMA−Thy1+ (Fig. 8A). Thus a high proportion of SMA+ myofibroblasts also expressed Thy1, and some myofibroblasts acquire a SMA−Thy1+ phenotype similar to endoneurial fibroblasts in vivo (Morris and Beech, 1984).

Fig. 8.

NCSC-derived myofibroblasts express the endoneurial fibroblast marker Thy1, and the generation of these cells is enhanced by Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta. (A,D) After 14 days in standard medium, nerve NCSCs give rise to myofibroblasts that are either SMA+Thy1− (purple arrows; 46±17% of cells with myofibroblast morphology), SMA+Thy1+ (white arrows; 44±15%), or SMA−Thy1+ (white arrowhead; 10±3%). Note that these colonies also contain large numbers of neurons and glia that are not visible in this field of view. After only 6 days in standard medium (B,D), NCSCs give rise to colonies containing mainly undifferentiated cells, as well as small numbers of myofibroblasts, which are mostly (92±6%) SMA+Thy1− (purple arrows). (C,D) In 6 day cultures supplemented with Delta, Nrg1 and Bmp4, nerve NCSCs give rise to larger numbers of myofibroblast cells, that include a higher frequency of SMA+Thy1+ cells (white arrows; 60±8%), and SMA−Thy1+ cells (white arrowhead; 28±7%) and a lower frequency of SMA+Thy1− cells (not shown; 12±4%). *P<0.05, relative to 6 day No Add (standard medium without Delta, Nrg1 or Bmp4 added);∂ indicates P<0.05, relative to 14 day No add (D). (E) Neural crest-derived myofibroblast progenitors can be isolated from acutely dissociated fetal rat sciatic nerve as p75−P0 + cells. (F) On average, 40±11% of these p75−P0 + cells express Thy1 in vivo. (G) 100% of the colonies that arose in culture from these p75−P0+Thy1+ cells were myofibroblast-only, and about 83% of these colonies consisted exclusively of SMA+Thy1− cells.

We next asked whether the Thy1+ population of sciatic nerve cells contains neural crest-derived, myofibroblast-only progenitors, and, if so, whether these cells express SMA in culture. We initially addressed this question using cells isolated from E14 rat embryonic sciatic nerve, the system in which NCSCs and their derivatives have been most extensively characterized (Morrison et al., 1999). Although Cre/lox-based fate mapping is not available in the rat, the peripheral myelin protein P0 is a highly specific marker of neural crest origin. Flow cytometric fractionation of E14 rat sciatic nerve cells labeled with antibodies to p75, P0 and Thy1 revealed that many myofibroblast-only progenitors were found in the p75−P0+fraction (Fig. 6), and that 42±13% of p75−P0 + cells were also Thy1+ (Fig. 8E,F). Importantly, culture of p75−P0+Thy1+ cells indicated that they exclusively formed myofibroblast-only colonies. Eighty-three percent of these colonies contained only SMA+Thy1− cells, while the remaining colonies also contained variable proportions of SMA+Thy1+ cells. These data suggest that neural crest-derived cells that generate myofibroblast-only cells in vitro are initially Thy1+ in vivo, but rapidly downregulate this marker in vitro and begin expressing a SMA+ myofibroblast phenotype.

To test whether endoneurial fibroblasts in postnatal mouse nerves also formed SMA+ myofibroblast colonies in culture, we sorted and cultured Thy1+ and Thy1− cells from the sciatic nerves of postnatal Wnt1-Cre+loxpRosa+ mice. Most of the cells that formed β-gal-expressing myofibroblast-only colonies in culture came from the Thy1+ cell fraction, and virtually all of the cells in such colonies expressed SMA after 5 to 7 days of culture (not shown). Interestingly, expression of SMA in culture was again associated with downregulation of Thy1 expression. As the only neural crest-derived fibroblasts in the nerve are endoneurial fibroblasts, these data suggest that Thy1+ endoneurial fibroblasts downregulate Thy1 expression and form SMA+ myofibroblast colonies in culture. Consistent with this, a variety of fibroblasts have been observed to adopt a SMA+ myofibroblast phenotype in culture and after injury in vivo (Sappino et al., 1990). Together these results suggest that the neural crest-derived myofibroblasts that arise in culture correspond to cells that acquire an endoneurial fibroblast fate in vivo.

The regulation of fibroblast and Schwann cell differentiation from NCSCs

To begin to study the mechanism by which the nerve environment regulates fibroblast and Schwann cell differentiation from nerve NCSCs, we investigated whether known factors from the nerve environment could account for this multilineage differentiation. First, the factors would have to cause individual sciatic nerve NCSCs to form Schwann cells and myofibroblasts, but not neurons, as sciatic nerve NCSCs do not give rise to neurons in the nerve (Bixby et al., 2002). Second, these factors would have to be permissive for neurogenesis from gut NCSCs, as gut NCSCs consistently form neurons when transplanted into developing peripheral nerves, and fail to form glia in most cases (Bixby et al., 2002). Neuregulin (Nrg1) (Dong et al., 1995), Delta, and Bmp4 are known to be expressed in developing peripheral nerves (Bixby et al., 2002), so we examined how this combination of factors affected the differentiation of NCSCs.

In standard medium (No Add; Table 3), 73% of sciatic nerve NCSC colonies were multilineage (Table 3). Addition of the immunoglobulin Fc domain protein [a negative control for the addition of Delta-Fc (Morrison et al., 2000b)] did not affect differentiation when compared with standard medium. Bmp4 by itself significantly promoted neurogenesis, whereas Delta-Fc and GGF by themselves significantly promoted gliogenesis (Bixby et al., 2002; Morrison et al., 2000b; Morrison et al., 1999; Shah et al., 1996; Shah et al., 1994). Note that plating efficiencies (the percentage of cells that survived to form colonies) varied among treatments because Nrg1 promotes the survival of nerve NCSCs (Morrison et al., 1999). Most colonies contained neurons in the combination of Bmp4 with Nrg1 (Shah and Anderson, 1997). The combination of Bmp4 and Delta-Fc promoted glial and myofibroblast differentiation by nerve NCSCs, as had been previously observed (Morrison et al., 2000b). Despite the fact that each individual factor promoted only neurogenesis or gliogenesis, the combination of Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc generated the highest proportion of colonies (52%) that contained both myofibroblasts and glia (M+G; Table 3; see Fig. S6 in supplementary material). Almost all remaining colonies in this treatment contained only glia (G-only) or only myofibroblasts (M-only). This demonstrates that the combination of Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc caused sciatic nerve NCSCs to differentiate into glia and myofibroblasts (see Fig. S6), consistent with the possibility that these factors in the nerve environment promote the differentiation of Schwann cells and endoneurial fibroblasts from NCSCs.

Table 3.

The combination of Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc cause sciatic nerve NCSC to give rise to glia and myofibroblasts but cause gut NCSCs to give rise to neurons and myofibroblasts

| Plating efficiency |

Colonies containing the indicated cell types (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N+M+G | N+G | N+M | N-only | M+G | M-only | G-only | U-only | ||

| SN NCSCs | |||||||||

| No add | 24±9§ | 73±15§ | 9±6§ | 0±0 | 1±2 | 7±4§ | 5±7§ | 6±7§ | 0±1 |

| Fc | 21±10§ | 72±7§ | 3±3§ | 2±4 | 3±6 | 10±9§ | 3±5§ | 7±8 | 0±0 |

| Nrg1 | 65±19* | 2±1*,§ | 3±5§ | 0±0 | 0±0 | 15±9*,§ | 7±5§ | 66±16*,§ | 7±5* |

| Delta-Fc | 17±5§ | 0±0* | 0±0* | 0±0 | 0±0 | 32±18*,§ | 13±4*,§ | 48±15*,§ | 7±6* |

| Bmp4 | 31±11§ | 4±4*,§ | 1±2* | 17±9*,§ | 42±17*,§ | 8±11§ | 11±6§ | 7±5§ | 9±6*,§ |

| Bmp4+Nrg1 | 70±13*,§ | 18±14*,§ | 4±2§ | 21±6*,§ | 16±9*,§ | 11±5§ | 18±11* | 7±2§ | 5±4* |

| Bmp4+Delta-Fc | 26±14§ | 0±0* | 0±0* | 2±5 | 1±2 | 30±13*,§ | 38±16* | 24±15* | 6±5* |

| Bmp4+Delta-Fc +Nrg1 | 50±12* | 0±1* | 0±0* | 0±0 | 0±0 | 52±13* | 27±11* | 17±10* | 3±4 |

| Gut NCSCs | |||||||||

| No add | 82±10 | 75±6 | 6±8 | 4±2 | 1±1 | 4±2 | 11±5 | 0±1 | 0±1 |

| Bmp4+Delta-Fc +Nrg1 | 74 ±16 | 2±2* | 0±0 | 30±14* | 24±14* | 4±4 | 35±7* | 1±1 | 4±4* |

E14.5 sciatic nerve and gut NCSCs were isolated by flow-cytometry as p75+α4+ cells, and cultured at clonal density for either 14 days (No add, Fc, GGF and Delta treatments) or 6 days (all other treatments), depending on the time required for the majority of cells to differentiate in each treatment. The cultures were stained with antibodies against peripherin to identify neurons (N), GFAP to identify glia (G), and SMA to identify myofibroblasts (M). All statistics represent mean±s.d. for four to 10 independent experiments

P<0.05 relative to No add

P<0.05 relative to Bmp4+Delta−Fc+Nrg1). U-only colonies did not stain for any of the differentiation markers but frequently had the appearance of G-only colonies, consistent with our previous observation that G-only colonies sometimes do not stain with GFAP (Morrison et al., 2000b).

U, unstained.

In contrast to their effect on nerve NCSCs, the combination of Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc caused gut NCSCs to give rise almost exclusively to neurons and myofibroblasts (Table 3; see Fig. S6 in supplementary material). This is consistent with the observation that gut NCSCs give rise to neurons, but usually do not give rise to glia when they engraft in developing peripheral nerves (Bixby et al., 2002). This further supports the idea that Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc regulate differentiation in the developing nerve environment in vivo.

To test whether these factors caused sciatic nerve NCSCs to undergo lineage restriction, we cultured nerve NCSCs (isolated by flow-cytometry) at clonal density either in standard medium, or in medium supplemented with Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc, for 7 days, and then subcloned the colonies into secondary cultures that contained standard medium. After 14 days, we examined the composition of the secondary colonies. Of 22 colonies that were subcloned from standard medium, 19 gave rise to multilineage secondary colonies, averaging 63±73 multilineage secondary colonies per primary colony, in addition to various other types of secondary colonies. This indicates that in standard medium NCSCs give rise to colonies that retain substantial numbers of multipotent progenitors. By contrast, colonies cultured in medium supplemented with Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc for 7 days never gave rise to multilineage secondary colonies or any secondary colonies that contained neurons. Rather all 35 colonies subcloned from this treatment gave rise to M+G, G-only, and/or M-only colonies. This indicates that the combination of Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc caused nerve NCSCs to undergo lineage restriction in culture to form progenitors that lacked neuronal potential, but retained glial and/or myofibroblast potential.

Bmp4+Nrg1+Delta-Fc promote the acquisition of an endoneurial fibroblast phenotype

If these factors promote the differentiation of NCSCs into endoneurial fibroblasts in vivo, then they would be expected to increase the proportion of myofibroblasts that acquire a SMA−Thy1+ phenotype in culture. To test this, we cultured NCSCs under standard conditions or in the presence of standard medium supplemented by Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc for 6 days, and then stained with antibodies against Thy1 and SMA. Under standard conditions, only 37% of colonies contained myofibroblasts after 6 days (averaging 5.9/colony) and 92±6% of cells with myofibroblast morphology were SMA+Thy1−, indicating poor differentiation toward an endoneurial fibroblast phenotype (Fig. 8B,D). However, after 6 days in Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc, 94% of colonies in these experiments contained myofibroblasts (as well as glia in most cases). and the number of myofibroblasts per colony was greatly increased (averaging 1073/colony). Almost 90% of cells with a myofibroblast morphology expressed Thy1 under these conditions. Of these, approximately one-third were SMA−, and two-thirds were SMA+ (Fig. 8C,D). All of these values were significantly different from what was observed in standard medium (P<0.05). These data suggest that, in addition to increasing the proportion of NCSCs that form myofibroblasts and glia in culture, the combination of Bmp4, Nrg1 and Delta-Fc also dramatically increases the number of myofibroblasts that express Thy1.

Discussion

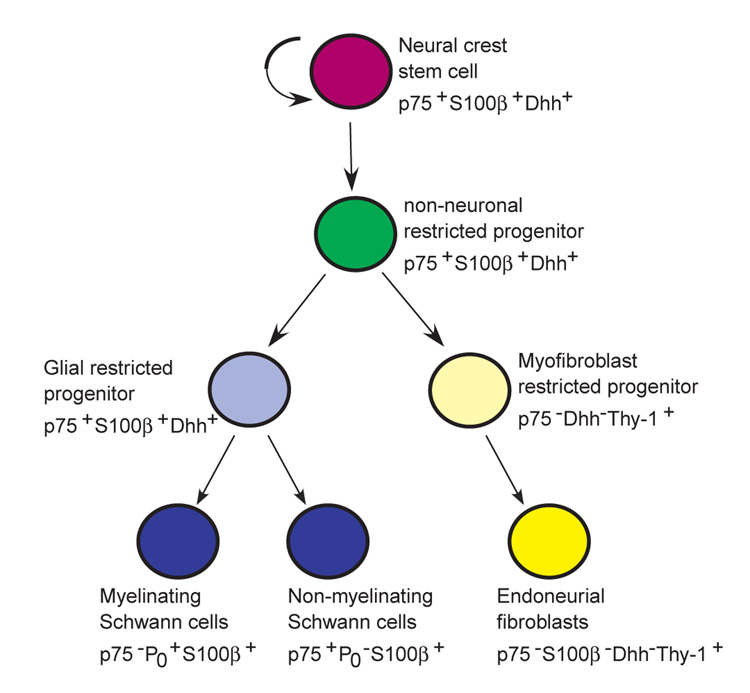

NCSCs cultured from sciatic nerve generate glia and myofibroblasts, in addition to neurons, but it has been assumed that the only neural crest-derived cells with their cell bodies in peripheral nerves are Schwann cells. We have mapped the fate of neural crest-derived cells in peripheral nerve using a Cre/lox-based approach (Zinyk et al., 1998), and a series of promoters specific to neural crest cells and their derivatives to drive Cre expression (Chai et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2000). Our results indicate that endoneurial fibroblasts in addition to myelinating and non-myelinating Schwann cells derive from the neural crest (Table 1, Fig 4, Fig 5). By contrast, other nerve cell types including perineurial cells, pericytes and endothelial cells, were not crest derived (Fig 2, Fig 3). Consistent with these observations, some of the myofibroblast progenitors cultured from freshly dissociated sciatic nerve were neural crest derived (Table 2, Fig. 7). Many of these neural crest-derived myofibroblast progenitors expressed Thy1 in vivo, a marker of nerve fibroblasts including endoneurial fibroblasts (Morris and Beech, 1984). Because endoneurial fibroblasts are the only non-glial neural crest-derivative in the sciatic nerve these data suggest that the myofibroblasts that arise in culture from nerve NCSCs or from freshly dissociated nerve cells correspond to cells that are fated to form endoneurial fibroblasts in vivo (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Model of peripheral nerve development. NCSCs self-renew in peripheral nerves to generate additional NCSCs (Morrison et al., 1999), as well as undergoing restriction under the influence of Nrg1, Delta and Bmp4. The resulting restricted progenitors lack neuronal potential (non-neuronal) but undergo lineage commitment to form both glial and myofibroblast progenitors. Glial progenitors differentiate to form both myelinating and non-myelinating Schwann cells, and myofibroblast progenitors differentiate to form endoneurial fibroblasts. It is likely that Nrg1, Delta and Bmp4 play multiple roles by having different effects on different cells within these lineages. For example, Nrg1 promotes the survival and glial restriction of NCSCs (Morrison et al., 1999; Shah et al., 1994), whereas it promotes the survival, proliferation and maturation of glial progenitors/Schwann cells (Dong et al., 1995), and the proliferation but not the survival of myofibroblast progenitors (Morrison et al., 1999).

Schwann cell and fibroblast lineage segregation probably occurs within peripheral nerve

To test whether endoneurial fibroblasts arise in vivo from multipotent progenitors within the nerve environment, or whether they arise from an independent lineage of progenitors, or prior to their migration into the nerve, we used Dhh-Cre to fate map nerve progenitors. Dhh is not expressed by migrating neural crest cells, or by neural crest progenitors that colonize ganglia, but is turned on in neural crest progenitors within developing peripheral nerves (Bitgood and McMahon, 1995; Jaegle et al., 2003; Parmantier et al., 1999) (see Fig. S5 in supplementary material). Both Schwann cells and endoneurial fibroblasts arose from Dhh-Cre expressing progenitors within the nerve (Fig. 5). To test whether they arose from a common progenitor, or whether they might have arisen from independent lineages that simultaneously expressed Dhh upon entry into the nerve environment, we examined Dhh expression in NCSCs, and myofibroblast progenitors isolated from the developing sciatic nerve (Fig. 6). We found that only NCSCs within the nerve expressed significant levels of Dhh. Myofibroblast progenitors expressed Dhh at levels that were equal to or lower than those observed in gut NCSCs and gut epithelial progenitors, which failed to activate reporter gene expression. These results suggest that myofibroblast progenitors arise from Dhh-expressing NCSCs within developing nerves.

The fact that similar percentages of Schwann cells and endoneurial fibroblasts expressed β-gal, whether the fate mapping was performed using Wnt1-Cre (Table 1) or Dhh-Cre (Fig. 5), also supports the conclusion that these cell populations originated from a common progenitor within the nerve. Wnt1 is expressed at the onset of neural crest migration, whereas Dhh is not expressed until days later in developing peripheral nerves. If Schwann cells and endoneurial fibroblasts arose from independent lineages of progenitors, these independent lineages would have to simultaneously begin expressing Wnt1, and then later simultaneously express Dhh. Moreover, the levels of expression of these genes would also have to be similar in both lineages to account for the similar degrees of recombination in both cell types. A more parsimonious explanation is that these lineages arise from a common progenitor that does not undergo lineage commitment until after migrating into the developing nerve.

Implications for models of nerve development

The finding that NCSCs undergo multilineage differentiation in developing peripheral nerves indicates that nerve development is more complex than was previously thought. Prior models of neural crest differentiation in the nerve considered only the overt differentiation of Schwann cells from Schwann cell precursors (Jessen et al., 1994; Jessen and Mirsky, 1992; Mirsky and Jessen, 1996). In the context of such models, genes that regulate neural development were assumed to play a role in this differentiation process. We find that NCSCs self-renew within developing peripheral nerves (Morrison et al., 1999), undergo restriction to form non-neuronal progenitors, make a fate choice between the glial and myofibroblast lineages, and then differentiate into Schwann cells and endoneurial fibroblasts (Fig. 9). The existence of these partially restricted, and glial and myofibroblast committed progenitors in vivo is supported by the ability to culture glia+myofibroblast (G+M) colonies, glia-only (G-only) colonies, or myofibroblast-only (M-only) colonies directly from freshly dissociated sciatic nerve (Morrison et al., 1999). Progenitors that form each of these colony types also arise from individual sciatic nerve NCSCs upon subcloning in culture (Morrison et al., 1999). It will be necessary to consider the functions of genes that are expressed by neural progenitors in the nerve in terms of NCSC self-renewal, lineage restriction, lineage commitment, and differentiation.

These results are also of general importance to understanding neural development, as they demonstrate that trunk neural crest cells actually adopt a myofibroblast fate in vivo. Previously, neural crest cells were known to form smooth muscle in the cardiac outflow tracts but more caudal trunk neural crest cells were not thought to adopt similar fates. As a result, although trunk NCSCs, including sciatic nerve NCSCs, have been defined partly based on their ability to form myofibroblasts (in addition to neurons and glia) in culture (Bixby et al., 2002; Morrison et al., 1999; Shah et al., 1996), it was unclear whether this myofibroblast capacity was actually used in vivo. This question has gained added importance with the demonstration in the developing spinal cord that separate populations of progenitors form oligodendrocytes and motoneurons, as compared to astrocytes and interneurons (Gabay et al., 2003). This suggests that although stem cells from the spinal cord have been defined based on their ability to form neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, there may not be a single cell population in vivo that actually forms all of these cell types in the spinal cord. The finding that the trunk neural crest gives rise to endoneurial fibroblasts (Fig. 4), in addition to neurons and glia (see Fig. S2 in supplementary material), demonstrates that the ability of these cells to form myofibroblasts does not result from reprogramming in culture. It is thus of interest to study the fibroblast/glial fate decision in addition to studying the neuron/glia fate decision by NCSCs.

The mechanism by which nerve NCSCs undergo multilineage differentiation appears to involve the combinatorial action of Bmp4, Delta, and Nrg1 on the NCSCs. Each of these factors is expressed in developing peripheral nerves in vivo (Bixby et al., 2002; Dong et al., 1995). Together these factors cause sciatic nerve NCSCs to form glia and myofibroblasts, but not neurons, in culture (Table 3, see Fig. S6 in supplementary material), even though individually the factors promote neuronal or glial fate determination (Morrison et al., 2000b; Morrison et al., 1999; Shah et al., 1996; Shah et al., 1994). In cultures supplemented with Bmp4, Delta and Nrg1, sciatic nerve NCSCs formed glia+myofibroblast (G+M) colonies, glia-only (G-only) colonies, and myofibroblast-only (M-only) colonies (Table 3), consistent with the possibility that these factors regulate the differentiation of NCSCs in developing nerves. Moreover, in the presence of these factors, NCSCs generated much larger numbers of myofibroblasts, and the myofibroblasts were more likely to acquire a Thy1+SMA− phenotype, thus resembling endoneurial fibroblasts (Fig. 8). The involvement of these factors is further supported by the observation that they cause gut NCSCs to give rise to neurons and myofibroblasts, but usually not glia, in culture (Table 3), consistent with the observation that gut NCSCs give rise to neurons but usually not to glia upon transplantation into developing peripheral nerves (Bixby et al., 2002). Thus the combinatorial effects of Bmp4, Delta and Nrg1 on sciatic nerve and gut NCSCs in culture appear to be consistent with the way in which these NCSC populations differentiate in developing nerves in vivo.

The embryonic origin of nerve cell types

The embryonic origin of different nerve cell types has long been controversial but until recent years it was not possible to directly trace the origin of nerve cell types in fate-mapping experiments in vivo. For example, it was debated whether perineurial cells were derived from Schwann cells, endoneurial fibroblasts, or an independent lineage of fibroblasts, based on morphological criteria (Low, 1976; Peltonen et al., 1987; Peters et al., 1976). Our fate mapping experiments demonstrate directly that the vast majority of perineurial cells are not neural crest derived and therefore cannot be lineally related to Schwann cells or endoneurial fibroblasts. Our data leave open the possibility that a small minority of perineurial cells on the endoneurial surface of the perineurium could be neural crest derived. The fibroblasts that give rise to the perineurium (Bunge et al., 1989) may be mesodermally derived, but our data do not address this directly. As nerve pericytes are also not neural crest derived they must invade the endoneurial space along with blood vessels. Whether pericytes are mesodermally-derived or whether they are lineally related to perineurial cells is not addressed by our data. Because Schwann cells secrete signals that regulate the formation of perineurium (Parmantier et al., 1999), nerve development involves a complex interaction of neural crest-derived and non-neural crest-derived progenitors.

Implications for nerve pathologies

Our finding that endoneurial fibroblasts are neural crest derived may also help to understand nerve pathology. Neurofibromas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors often contain fibroblasts in addition to cells that resemble Schwann cells (Serra et al., 2000; Takeuchi and Uchigome, 2001). Some of these fibroblasts derive from surrounding normal tissue rather than arising from the neoplastic clone (Serra et al., 2000). However, neoplastic transformation of NCSCs or non-neuronal restricted nerve progenitors could potentially yield clonal tumors containing both Schwann cells and fibroblasts. Recently, neurofibromas were concluded to arise from Schwann cells, based on their ability to generate neurofibromas following conditional deletion of floxed NF1 using Krox20-Cre (Zhu et al., 2002). However, Krox20 also appears to be expressed by sciatic nerve NCSCs (data not shown), so this conditional deletion strategy would be expected to yield NF1-deficient NCSCs as well as Schwann cells. Our observation that endoneurial fibroblasts are derived from nerve NCSCs raises the possibility that NCSCs are sometimes transformed by NF1 deficiency to form tumors containing clonally-derived Schwann cells and fibroblasts.

Neural differentiation in the nerve thus involves stem cell self-renewal, lineage restriction, lineage commitment and multilineage differentiation. We have begun to elucidate this process by showing that the combination of Bmp4, Delta and Nrg1 promotes glial and fibroblast differentiation by sciatic nerve NCSCs. This changes models of nerve development by broadening the scope of neural crest involvement.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/131/22/5599/DC1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS40750), the Searle Scholars Program, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. N.M.J. was supported by the MSTP, and Cell and Developmental Biology Training Grants (University of Michigan). Thanks to David Adams, Martin White, Anne Marie Deslaurier, and the University of Michigan Flow-Cytometry Core Facility. Flow-cytometry was supported in part by the UM-Comprehensive Cancer NIH CA46592, and the UM-Multipurpose Arthritis Center NIH AR20557. Thanks to Elizabeth Smith in the Hybridoma Core Facility, supported through the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60-DK20572) and the Rheumatic Core Disease Center (1 P30 AR48310). Thanks to Chris Edwards, Dorothy Sorensen and Qian-Chun Yu for assistance with confocal and electron microscopy. Thanks to Andrew McMahon for providing Wnt1-Cre mice; to Philippe Soriano for providing loxpRosa mice; and to K. Sue O’Shea for expert advice on nerve histology.

References

- Anderson DJ. Stem cells and pattern formation in the nervous system: the possible versus the actual. Neuron. 2001;30:19–35. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assouline JG, Bosch EP, Lim R. Purification of rat Schwann cells from cultures of peripheral nerve: an immunoselective method using surfaces coated with anti-immunoglobulin antibodies. Brain Res. 1983;277:389–392. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood MJ, McMahon AP. Hedgehog and Bmp genes are coexpressed at many diverse sites of cell-cell interaction in the mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 1995;172:126–138. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixby S, Kruger GM, Mosher JT, Joseph NM, Morrison SJ. Cell-intrinsic differences between stem cells from different regions of the peripheral nervous system regulate the generation of neural diversity. Neuron. 2002;35:643–656. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzola JJ, Russell LD. Electron microscopy: principles and techniques for biologists. Boston, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Brockes JP, Fields KL, Raff MC. Studies on cultured rat Schwann cells. I. Establishment of purified populations from cultures of peripheral nerve. Brain Res. 1979;165:105–118. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunge MB, Wood PM, Tynan LB, Bates ML, Sanes JR. Perineurium originates from fibroblasts: demonstration in vitro with a retroviral marker. Science. 1989;243:229–231. doi: 10.1126/science.2492115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, Bringas P, Han J, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:1671–1679. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone SA, Negro A, Trumpp A, Giovannini M, Lee K-F. Colonic epithelium expression of ErbB2 is required for postnatal maintenance of the enteric nervous system. Neuron. 2003;37:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielian PS, Echelard Y, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. A 5.5-kb enhancer is both necessary and sufficient for regulation of Wnt-1 transcription in vivo. Dev. Biol. 1997;192:300–309. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Brennan A, Liu N, Yarden Y, Lefkowitz G, Mirsky R, Jessen KR. Neu differentiation factor is a neuron-glia signal and regulates survival, proliferation and maturation of rat Schwann cell precursors. Neuron. 1995;15:585–596. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L, Lowell S, Rubin LL, Anderson DJ. Deregulation of dorsoventral patterning by FGF confers trilineage differentiation capacity on CNS stem cells in vitro. Neuron. 2003;40:485–499. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari L, Brault V, Kleber M, Lee HY, Ille F, Leimeroth R, Paratore C, Suter U, Kemler R, Sommer L. Lineage-specific requirements of beta-catenin in neural crest development. J. Cell Biol. 2002;159:867–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose T, Sano T, Hizawa K. Ultrastructural localization of S-100 protein in neurofibroma. Acta Neuropathol. 1986;69:103–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00687045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya M, Lee SMK, Johnson JE, McMahon AP, Takada S. Wnt signalling required for expansion of neural crest and CNS progenitors. Nature. 1997;389:966–970. doi: 10.1038/40146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola S, Peltonen J, Riccardi V, Chu M-L, Uitto J. Type 1 neurofibromatosis: selective expression of extracellular matrix genes by Schwann cells, perineurial cells, and fibroblasts in mixed cultures. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;84:253–261. doi: 10.1172/JCI114148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JA, Majka SM, Wang HG, Pocius J, Hartley CJ, Majesky MW, Entman ML, Michael LH, Hirschi KK, Goodell MA. Regeneration of ischemic cardiac muscle and vascular endothelium by adult stem cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:1395–1402. doi: 10.1172/JCI12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaegle M, Ghazvini M, Mandemakers W, Piirsoo M, Driegen S, Levavasseur F, Raghoenath S, Grosveld F, Meijer D. The POU proteins Brn-2 and Oct-6 share important functions in Schwann cell development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1380–1391. doi: 10.1101/gad.258203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Schwann cells: early lineage, regulation of proliferation and control of myelin formation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1992;2:575–581. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(92)90021-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR, Brennan A, Morgan L, Mirsky R, Kent A, Hashimoto Y, Gavrilovic J. The Schwann cell precursor and its fate: a study of cell death and differentiation during gliogenesis in rat embryonic nerves. Neuron. 1994;12:509–527. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development. 2000;127:1607–1616. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby ML, Waldo KL. Neural crest and cardiovascular patterning. Circ. Res. 1995;77:211–215. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin NM. The Neural Crest. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Low FN. The perineurium and connective tissue of peripheral nerve. In: Landon DN, editor. The Peripheral Nerve. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 1976. pp. 159–187. [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky R, Jessen KR. Schwann cell development, differentiation and myelination. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1996;6:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RJ, Beech JN. Differential expression of Thy-1 on the various components of connective tissue of rat nerve during postnatal development. Dev. Biol. 1984;102:32–42. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, White PM, Zock C, Anderson DJ. Prospective identification, isolation by flow cytometry, and in vivo self-renewal of multipotent mammalian neural crest stem cells. Cell. 1999;96:737–749. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80583-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Csete M, Groves AK, Melega W, Wold B, Anderson DJ. Culture in reduced levels of oxygen promotes clonogenic sympathoadrenal differentiation by isolated neural crest stem cells. J. Neurosci. 2000a;20:7370–7376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Perez S, Verdi JM, Hicks C, Weinmaster G, Anderson DJ. Transient Notch activation initiates an irreversible switch from neurogenesis to gliogenesis by neural crest stem cells. Cell. 2000b;101:499–510. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmantier E, Lynn B, Lawson D, Turmaine M, Namini SS, Chakrabarti L, McMahon AP, Jessen KR, Mirsky R. Schwann cell-derived desert hedgehog controls the development of peripheral nerve sheaths. Neuron. 1999;23:713–724. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr BA, Shea MJ, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Mouse Wnt genes exhibit discrete domains of expression in the early embryonic CNS and limb buds. Development. 1993;119:247–261. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltonen J, Jaakkola S, Virtanen I, Pelliniemi L. Perineurial cells in culture: an immunocytochemical and electron microscopic study. Lab. Invest. 1987;57:480–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HD. The Fine Structure of the Nervous System: The Neurons and Supporting Cells. Toronto, Canada: W. B: Saunders Company; 1976. Connective tissue sheaths of peripheral nerves; pp. 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Sappino AP, Schurch W, Gabbiani G. Differentiation repertoire of fibroblastic cells: expression of cytoskeletal proteins as marker of phenotypic modulations. Lab. Invest. 1990;63:144–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra E, Rosenbaum T, Winner U, Aledo R, Ars E, Estivill X, Lenard H-G, Lazaro C. Schwann cells harbor the somatic NF1 mutation in neurofibromas: evidence of two different Schwann cell subpopulations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:3055–3064. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.20.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NM, Anderson DJ. Integration of multiple instructive cues by neural crest stem cells reveals cell-intrinsic biases in relative growth factor responsiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11369–11374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NM, Marchionni MA, Isaacs I, Stroobant PW, Anderson DJ. Glial growth factor restricts mammalian neural crest stem cells to a glial fate. Cell. 1994;77:349–360. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NM, Groves A, Anderson DJ. Alternative neural crest cell fates are instructively promoted by TGFβ superfamily members. Cell. 1996;85:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siironen J, Sandberg M, Vuorinen V, Roytta M. Expression of type I and III collagens and fibronectin after transection of rat sciatic nerve. Lab. Invest. 1992;67:80–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemple DL, Anderson DJ. Isolation of a stem cell for neurons and glia from the mammalian neural crest. Cell. 1992;71:973–985. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90393-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi A, Uchigome S. Diverse differentiation in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours associated with neurofibromatosis-1: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Histopathology. 2001;39:298–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vroemen M, Weidner N. Purification of Schwann cells by selection of p75 low affinity nerve growth factor receptor expressing cells from adult peripheral nerve. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2003;124:135–143. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis J, Fine SM, David C, Savarirayan S, Sanes JR. Integration site-dependent expression of a transgene reveals specialized features of cells associated with neuromuscular junctions. J. Cell Biol. 1991;113:1385–1397. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.6.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi Y, Abe K, Mantani A, Hitoshi Y, Suzuki M, Osuzu F, Kuratani S, Yamamura K-I. A novel transgenic technique that allows specific marking of the neural crest cell lineage in mice. Dev. Biol. 1999;212:191–203. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Ghosh P, Charnay P, Burns DK, Parada LF. Neurofibromas in NF1: Schwann cell origin and role of tumor environment. Science. 2002;296:920–922. doi: 10.1126/science.1068452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinyk DL, Mercer EH, Harris E, Anderson DJ, Joyner AL. Fate mapping of the mouse midbrain-hindbrain constriction using a site-specific recombination system. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:665–668. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/131/22/5599/DC1