Abstract

The hormone leptin crosses the blood brain barrier and regulates numerous neuronal functions, including hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Here we show that application of leptin resulted in the reversal of long-term potentiation (LTP) at hippocampal CA1 synapses. The ability of leptin to depotentiate CA1 synapses was concentration dependent and it displayed a distinct temporal profile. Leptin-induced depotentiation was not associated with any change in the paired pulse facilitation ratio or the coefficient of variation (CV), indicating a postsynaptic locus of expression. Moreover, the synaptic activation of NMDA receptors was required for leptin-induced depotentiation as the effects of leptin were blocked by the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist, D-aminophosphovaleric acid (D-AP5). The signaling mechanisms underlying leptin-induced depotentiation involved activation of the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, calcineurin, but were independent of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK). Furthermore, leptin-induced depotentiation was accompanied by a reduction in AMPA receptor rectification indicating that loss of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors underlies this process. These data indicate that leptin reverses hippocampal LTP via a process involving calcineurin-dependent internalization of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors which further highlights the key role for this hormone in regulating hippocampal synaptic plasticity and neuronal development.

Keywords: Leptin, synaptic plasticity, depotentiation, AMPA receptor, hippocampus, calcineurin

Introduction

Activity-dependent forms of hippocampal synaptic plasticity such as long term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) are thought to be cellular correlates of learning, memory and cognition. Although LTP and LTD result in persistent changes in the efficacy of excitatory synaptic transmission, LTP can be readily reversed shortly after LTP induction; a process known as depotentiation. For instance, application of theta burst stimuli, low frequency stimulation or metabotropic glutamate receptor activation results in the reversal of LTP (Bashir and Collingridge, 1994; Huang & Hsu, 2001; Huang et al, 2001). Similarly, transient exposure to anoxic stimuli for 1-2 min after the induction of LTP prevents the expression of LTP (Arai et al, 1990). More recent studies have demonstrated that the trophic factor, neuregulin-1 has the capacity to depotentiate LTP at hippocampal CA1 synapses by reducing the cell surface expression of AMPA receptors (Kwon et al, 2005). The ability of hippocampal synapses to depotentiate is thought to act as a break mechanism to prevent saturation of potentiated synapses, which in turn is likely to enhance the efficiency of information storage within neuronal networks (Huang and Hsu, 2001).

Several lines of evidence indicate that the anti-obesity hormone, leptin has widespread actions in the CNS. In particular several studies have shown that leptin markedly influences NMDA receptor-dependent hippocampal synaptic plasticity as well as hippocampal-dependent learning and memory (Farr et al, 2006; Harvey, 2007). Indeed, rodents with dysfunctional leptin receptors display impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity and deficits in spatial memory tasks (Li et al, 2002). Direct application of leptin into the hippocampus also improves performance in specific memory tasks (Farr et al, 2006). At the cellular level, leptin facilitates LTP at hippocampal CA1 synapses (Shanley et al, 2001) whereas under conditions of enhanced excitability leptin evokes a novel form of NMDA receptor-dependent LTD (Durakoglugil et al, 2005). In addition, leptin promotes rapid changes in neuronal structure including alterations in dendritic morphology and synaptic density, which are likely to contribute to leptin-driven changes in synaptic efficacy (O'Malley et al, 2007). However, little is known about the effects of leptin on potentiated synapses. Here we provide the first compelling evidence that leptin rapidly reverses LTP at hippocampal CA1 synapses. Reversal of LTP by leptin is both concentration- and time-dependent, and is not associated with any change in the paired-pulse ratio or coefficient of variance (CV), suggesting a postsynaptic locus of expression. Leptin-induced depotentiation is NMDA receptor-dependent and is mediated by a calcineurin-dependent process. Moreover, leptin-induced depotentiation is accompanied by change in the rectification properties of AMPA receptors indicating that this process involves changes in GluR2 content of AMPA receptors at hippocampal CA1 synapses.

Materials and Methods

Hippocampal slice preparation

Young Sprague Dawley male rats (14-20 days old) were killed by cervical dislocation in accordance with Schedule 1 of the U.K. Government Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. After decapitation the brain was removed and placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) consisting of (mM): NaCl 124; KCl 3; NaHCO3 26; NaH2PO4 1.25; MgSO4 1; CaCl2 2; D-glucose 10 (bubbled with 95% O2/ 5% CO2; pH 7.4). Transverse hippocampal slices (400 μm) were cut using a Vibratome or DSK tissue slicer (Intracel, Royston, UK) and were maintained in oxygenated aCSF at room temperature (21-22°C) for an hour before use.

Electrophysiological recordings

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made at 33°C from hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons visually identified with an Olympus BX51 (Olympus, Southall, UK) microscope using differential interference contrast optics. Evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) were obtained using pipettes comprising (mM): 130 Cs+ methanesulphonate, 5 NaCl, 5 HEPES, 1 EGTA, 5 Mg-ATP, 1 CaCl2 and 5 QX-314, pH 7.3. Synaptic currents were evoked by single shock electrical stimulation at a frequency of 0.0333 Hz using a bipolar stimulating electrode placed on Schaffer collateral-commissural fibers, and cells were voltage-clamped at −60 mV. All recordings were performed in the presence of picrotoxin (50 μM) to block GABAA receptor-mediated currents, whereas intracellular cesium ions blocked GABAB receptor-mediated currents. Whole-cell recordings were made using an Axopatch 200B patch clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and data were filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. Electrical signals were recorded and analysed on- and off-line using LTP software (Courtesy of Dr Bill Anderson, University of Bristol, UK; Anderson and Collingridge, 2001). Whole-cell access resistances were in the range 7–15 MΩ prior to electrical compensation by 65–80%. Access resistance was continuously monitored and experiments abandoned if changes >20% were encountered. LTP was evoked by either 3 trains, 250 ms apart, 20-40 stimulations at 200Hz, or by a pairing protocol (0 mV, 50-100 pulses at 0.5-1.5Hz). For the paired-pulse facilitation studies, two consecutive stimuli with an inter-stimulus interval of 50 ms were delivered. The paired pulse ratio was calculated as the ratio of the amplitude of the second EPSC to the first EPSC. To ensure measurement of the second EPSC was not contaminated by residual current of the first EPSC, the residual component was removed by extrapolation of the first EPSC and using this point to calculate the peak using MiniAnalysis 5.6.25 programme (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA). The coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated as described previously (Kullman, 1994). Briefly, the mean and SD were calculated for the EPSC amplitudes recorded during successive 5 min epochs (SDEPSC and meanEPSC). For each 5 min epoch the SD of the background noise was also calculated using a period immediately before electrical stimulation (SDnoise). The CV for each 5min epoch was calculated as (SDEPSC-SDnoise)/meanEPSC. In order to calculate the amount of rectification of AMPA receptor-mediated EPSC, 0.1 mM spermine was included in the whole cell patch pipette. Cells were depolarized to a positive potential (+40 mV) for 2 min (4 successive stimulations) prior to the induction of LTP and at 5 min, 30 min and 45 min after LTP induction. The rectification indices were calculated by plotting the initial slope of the average EPSC at −60mV, 0mV and + 40 mV and taking the ratio of the slope of the lines connecting values at 0 to +40 and at −60 to 0 mV.

Materials

Human recombinant leptin (R & D Systems; 95-98% purity) was prepared as a stock solution and was diluted in normal aCSF. SP600126, D-APV, spermine, cypermethrin, Philanthotoxin-433 and picrotoxin were all obtained from Tocris Cookson (Avonmouth, UK).

Analysis

In all experiments, the peak amplitude of EPSCs was monitored continuously. For studies comparing the actions of leptin and all other agents on EPSCs, the mean amplitude (average of 5 min recording) of EPSCs obtained during the 5 min period immediately prior to leptin and/or agent addition was compared to that after 10-15 min after exposure to leptin. Statistical significance of mean data was assessed with the unpaired Student's t test or repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni's test as appropriate. n signifies the number of times a given experiment was performed, with each experiment using a slice from a different animal. Experimental and corresponding control experiments were interleaved throughout.

Results

Leptin reverses the expression of hippocampal LTP

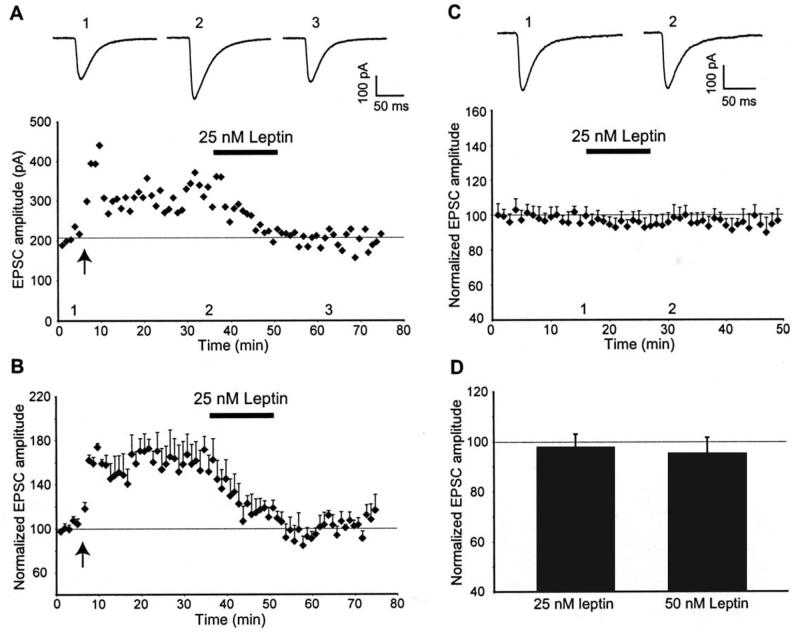

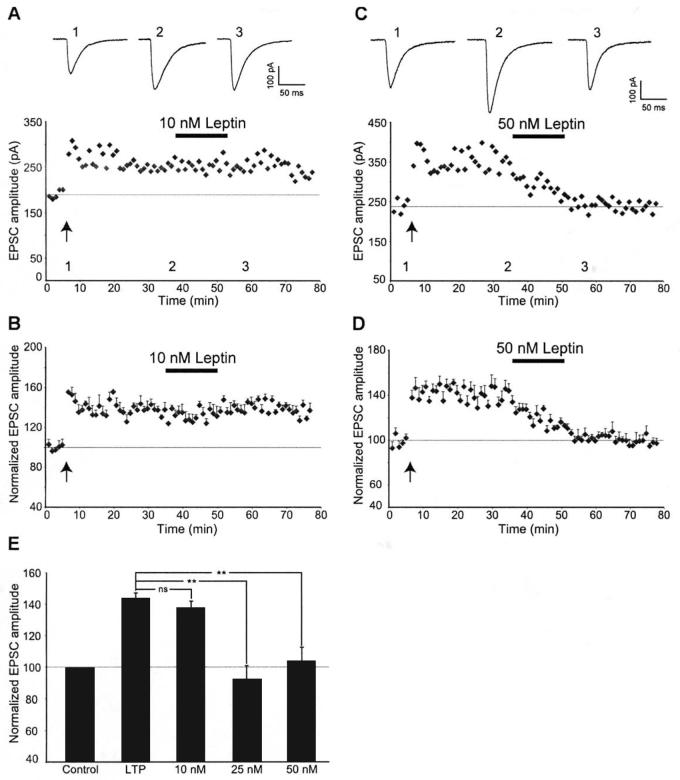

Our previous studies have demonstrated that leptin evokes a novel form of hippocampal LTD at naïve CA1 synapses (Durakoglugil et al, 2005). However it is not known if leptin has the ability to depress potentiated hippocampal synapses. In order to examine this, we initially confirmed that the high frequency stimulation (HFS) protocol resulted in robust LTP. The amplitude of EPSCs measured 25-30 min after high frequency stimulation was 150 ± 1.6% of baseline (n=12). Perfusion of hippocampal slices with leptin (25-50 nM; 15 min), 30 min after the induction of LTP, resulted in a rapid and concentration-dependent reversal of LTP (n=9; Figs 1A,B&2E). Thus the amplitude of EPSCs were significantly reduced, compared to control slices, after 10 min exposure to 25 nM leptin (to 112 ± 6.2% of baseline; n=5). Maximal depotentiation was obtained within at least 5 min of leptin washout (92.5 ± 8.3% of baseline; n=5; p>0.05 relative to basal synaptic transmission). Similarly application of 50 nM leptin for 15 min, 30 min after LTP induction, resulted in a significant reduction in EPSC amplitude to 118 ± 14% of baseline after 10 min exposure to leptin and the level of depression was maximal within 5 min of leptin washout (to 103 ± 9%, n=7; P>0.05 relative to basal synaptic transmission). In contrast, application of a lower concentration of leptin (10 nM; 15 min), 30 min after LTP induction had no effect on the expression of LTP (n=4; Fig 2A,B&E). The effects of leptin on basal transmission were also examined (Fig 1C&D) and we found that application of 25 nM leptin (15 min) or 50 nM leptin (for 15 min) evoked a small but not significant reduction in the amplitude of EPSCs (25 nM leptin: 97 ± 5.3% of baseline; n=7; P>0.05, 50 nM Leptin: 95 ± 6.6% of baseline; n=5; P>0.05). Thus these data indicate that leptin, at concentrations that do not significantly affect basal synaptic transmission, reverses the expression of hippocampal LTP in a concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 1. Leptin reverses hippocampal LTP.

A, Plot of EPSC amplitude against time from an individual hippocampal slice. Application of high frequency stimulation at the time indicated by the arrow resulted in robust LTP. Subsequent application of leptin (25 nM) for the time indicated by the bar resulted in a reversal of synaptic transmission to pre-LTP levels. Above the plot are the corresponding averaged EPSCs obtained from the same experiment under control conditions (1), following induction of LTP (2) and after exposure to leptin (3). B, Plot of pooled data illustrating the normalized EPSC amplitude against time. Treatment of slices with leptin (25nM), 30 min after the induction of LTP rapidly reversed synaptic transmission to pre-LTP levels C, Plot of pooled data illustrating normalized EPSC amplitude against time. In contrast, application of leptin (25 nM) for the time indicated by the bar had no significant effect on basal synaptic transmission. Examples of the averaged synaptic currents obtained in the absence (1) and presence of leptin (2) are depicted above the plot. D, Histogram of the pooled data illustrating the relative depressions of basal synaptic transmission induced by application of either 25nM or 50 nM leptin, respectively.

Figure 2. Leptin depotentiates hippocampal synapses in a concentration-dependent manner.

A, Plot of EPSC amplitude against time from an individual experiment. Application of leptin (10 nM), 30 min after LTP induction failed to influence the magnitude of potentiated synapses. Above the plot are the corresponding EPSCs obtained from the same experiment under control conditions (1), following induction of LTP (2) and after exposure to 10 nM leptin (3). B, Plot of pooled data illustrating the normalized EPSC amplitude against time. C, Plot of EPSC amplitude against time from an individual experiment. In contrast, application of leptin (50 nM) 30 min after the induction of LTP readily reversed synaptic currents to pre-LTP levels. Above the plot are the corresponding traces of EPSCs obtained in control conditions (1), following induction of LTP (2) and after exposure to 50 nM leptin (3). D, Plot of the pooled data of normalized EPSC amplitude against time. Application of leptin (50 nM), 30 min after the induction of LTP, resulted in robust depotentiation of hippocampal synapses. E, Histogram of the pooled data depicting the relative synaptic depressions induced by application of 10 nM, 25 nM and 50 nM leptin, respectively. In this and subsequent figures, *, ** and *** represent P<0.05, P<0.01 and P<0.001, respectively.

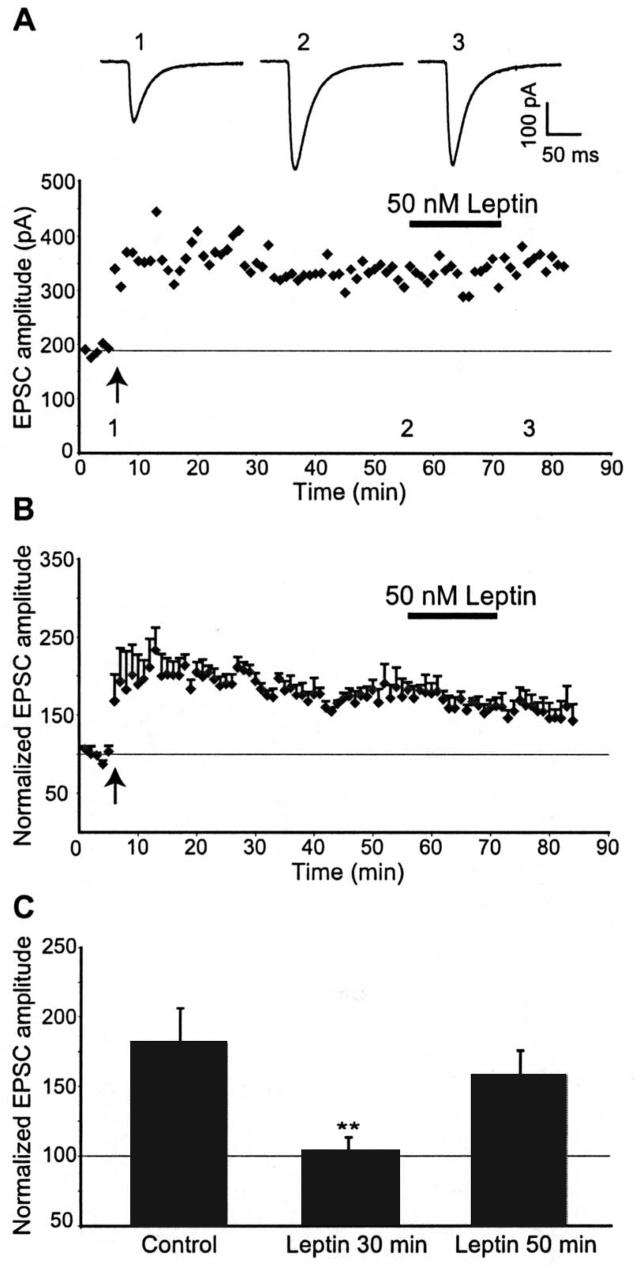

Leptin evokes a time-dependent reversal of LTP

Previous studies have shown that the capacity of potentiated synapses to depotentiate generally occurs within a specific time window and in general LTP is difficult to reverse more than 30 min after the induction of LTP (Staubli & Chun, 1996; Huang & Hsu, 2001). Thus in the next series of experiments we determined if leptin-induced depotentiation was time-dependent by comparing the degree of synaptic depression induced following perfusion of slices with leptin (50 nM) either 30 min or 50 min after LTP induction. Application of leptin up to 30 min after LTP induction completely reversed the expression of LTP (n=7), whereas leptin failed to influence the efficacy of potentiated synapses when applied after 50 min (Fig 3A,B&C), such that EPSCs were potentiated to 180 ± 25% of baseline (25 min after HFS) and subsequent addition of leptin 50 min after HFS did not significantly alter the magnitude of LTP (157 ± 17% of baseline; n=4; P>0.05). These data indicate not only that the ability of leptin to depotentiate hippocampal CA1 synapses occurs within a limited time window but also suggest that after 50 min LTP has stabilized by mechanisms rendering it leptin-insensitive.

Figure 3. The synaptic depotentiation induced by leptin is time-dependent.

A, Plot of EPSC amplitude against time from an individual experiment. Exposure of hippocampal slices to 50 nM leptin, 50 min after the LTP induction, failed to alter the magnitude potentiated synapses. Above the plot are representative examples of EPSCs obtained in control conditions (1), after the induction of LTP (2) and following addition of 50 nM leptin, 50 min after LTP induction (3). B, Plot of the pooled data illustrating the normalized EPSC amplitude against time. Leptin failed to induce synaptic depotentiation, 50 min after LTP induction. C, Histogram of the pooled data illustrating the relative synaptic depressions, obtained after 10-15 min exposure to leptin (50 nM) when applied either 30 min or 50 min after the induction of LTP. Leptin depotentiated synapses 30 min after LTP induction, but was without effect 50 min after LTP induction.

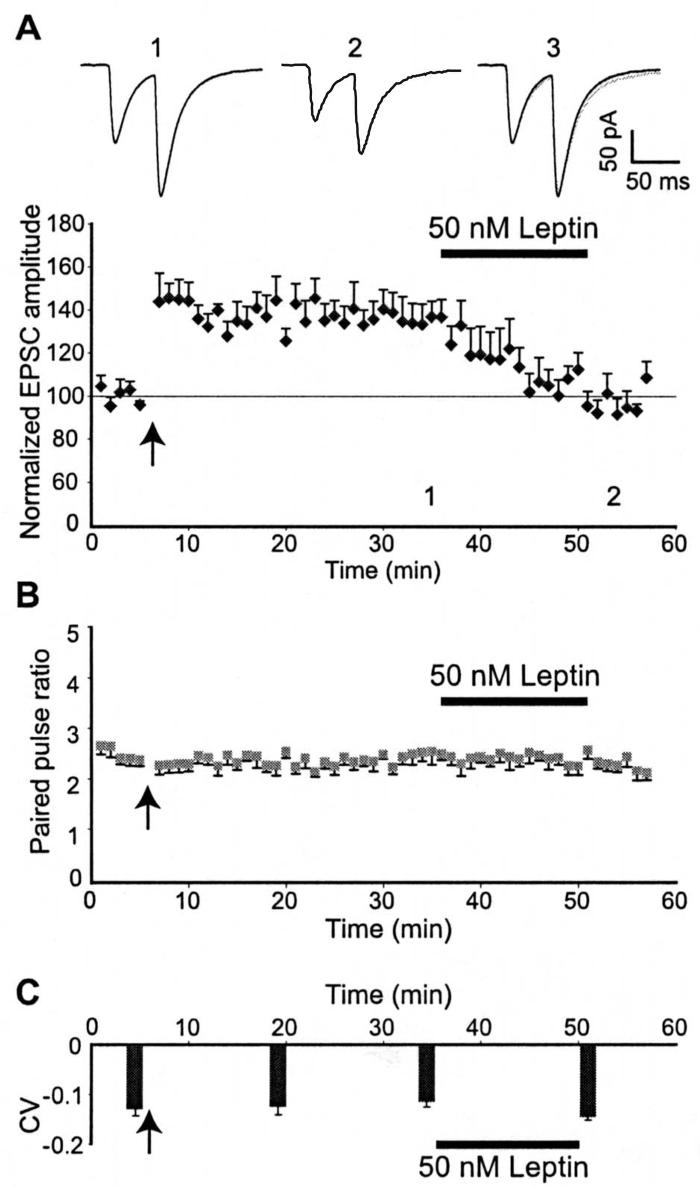

Leptin-induced depotentiation has a postsynaptic locus of expression

A number of studies have demonstrated that depotentiation of hippocampal CA1 synapses by theta burst stimulation, metabotropic glutamate receptors or neuregulin-1 has a postsynaptic locus of expression (Zho et al, 2002; Kwon et al, 2005). As leptin receptors are expressed both pre- and postsynaptically in hippocampal neurons (Shanley et al, 2002), it is feasible that leptin reversal of LTP could be expressed at either locus. Thus, in order to examine the site of leptin-induced depotentiation, a paired pulse stimulation protocol was used such that two consecutive stimuli were delivered with an inter-stimulus interval of 50 ms. In agreement with previous studies (Manabe et al, 1993), the induction of LTP at hippocampal CA1 synapses was not associated with any change in the paired-pulse facilitation ratio (PPR). Moreover, the reversal of LTP induced by application of 50 nM leptin (for 15 min), 30 min after LTP induction, was not associated with any significant change in the PPR (n=6; Fig 4B). Thus, the average PPR obtained 5 min after washout of leptin was 2.39 ± 0.15, which was not significantly different from the paired-pulse ratio obtained following LTP induction (2.42 ± 0.17; n=6; P>0.05). The coefficient of variance (CV) was also analyzed for these experiments (Fig 4C). In accordance with previous studies (Manabe et al, 1993), the induction of LTP was not accompanied by any significant change in the CV of the first EPSC of the pair (Fig 4C). Furthermore, the CV was unchanged following leptin-induced depotentiation such that the CV values obtained under control conditions, following LTP induction and after reversal of LTP by leptin were −0.13 ± 0.01, −0.12 ± 0.01 and −0.14 ± 0.06, respectively (n=6; P>0.05). Thus these data demonstrate that leptin-induced depotentiation is not associated with changes in PPR or CV, indicating that this process is likely to be postsynaptic in origin.

Figure 4. Leptin-induced depotentiation has a postsynaptic locus of expression.

A, B, Leptin-induced depotentiation was not associated with any change in the paired-pulse facilitation ratio. A, Plot of the pooled data depicting the normalized EPSC amplitude against time. Application of leptin (50 nM) 30 min after LTP induction depressed synaptic transmission to pre-LTP levels. B, Plot of the pooled data showing the mean paired-pulse ratio against time for the experiments shown in A. Leptin-induced depotentiation is not associated with any change in paired-pulse ratio. Above the plots are representative pairs of EPSCs evoked with a 50 ms inter-stimulus interval after LTP induction (1) and following application of leptin (50 nM; 2). In 3 the first EPSC in 2 has been scaled to match the size of the first EPSC in 1. C, Plot of the pooled data illustrating the mean coefficient of variation (CV) against time for the experiments depicted in A. The reversal of LTP induced by leptin is not associated with any change in the CV.

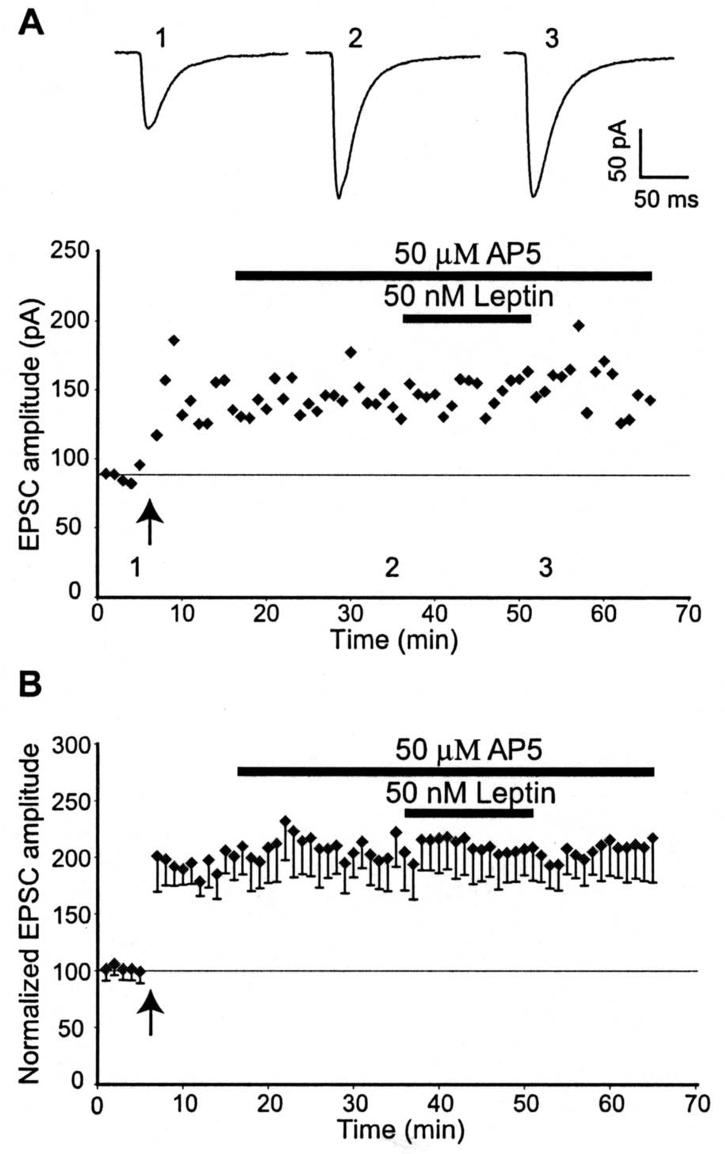

Leptin-induced depotentiation is NMDA receptor-dependent

Previous studies have shown that the induction of depotentiation by either low frequency stimulation (LFS) or DHPG is NMDA receptor-dependent (Massey et al, 2004; Huang et al, 2001). Moreover, our studies have shown that the facilitation of hippocampal LTP, induction of LTD as well as the dendritic morphogenesis induced by leptin are all NMDA dependent processes (Shanley et al, 2001; Durakoglugil et al, 2005; O'Malley et al, 2007). Thus, in order to assess the role of NMDA receptors, the effects of the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist D-AP5 on the development of leptin-induced depotentiation were examined. In these studies, D-AP5 (50 μM) was applied to the aCSF 20 min after the induction of LTP, which had no effect on the magnitude of LTP per se (n=7). However, subsequent addition of leptin (50 nM) after at least 10 min exposure to D-AP5 failed to reverse LTP such that the amplitude of EPSCs was 206 ± 29% of baseline and 199 ± 20% of baseline (n=7; P>0.05; Fig 5A&B), in the absence and following 15 min exposure to leptin, respectively. These data suggest that the ability of leptin to reverse hippocampal LTP requires the synaptic activation of NMDA receptors.

Figure 5. Leptin-induced depotentiation requires NMDA receptor activation.

A, Plot of EPSC amplitude against time for an individual experiment. Application of the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist D-AP5 (50 μM), after LTP induction, blocked the ability of leptin (50 nM) to reverse hippocampal LTP. Top, representative traces of averaged EPSCs in control conditions (1), in the presence of D-AP5 (2) and in the combined presence of D-AP5 and leptin (3). B, Summary data showing that blockade of NMDA receptors inhibits leptin-induced depotentiation (n=7).

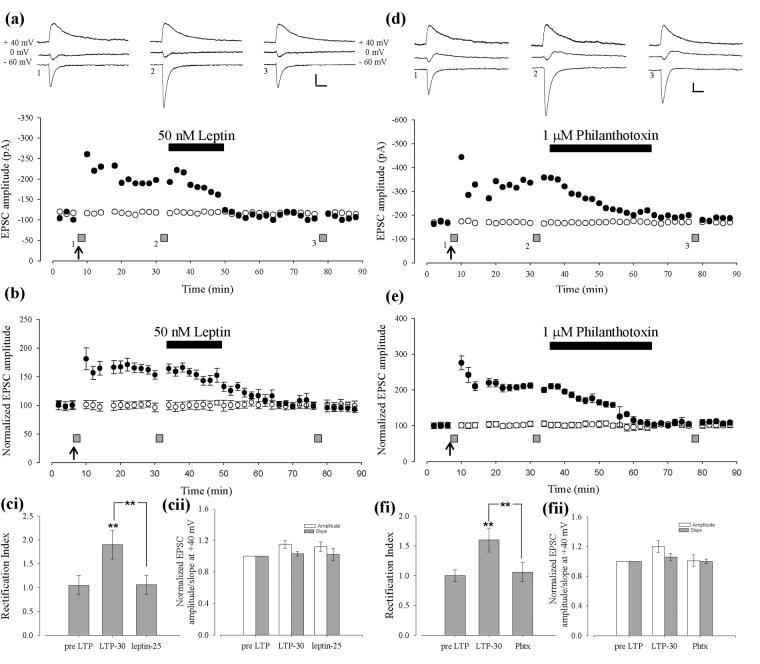

Leptin-induced depotentiation involves changes in the GluR2 content of hippocampal synapses

It is well documented that AMPA receptor trafficking is pivotal for activity-dependent hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Collingridge et al, 2004). Moreover, previous studies have shown that internalization of synaptic AMPA receptors underlies the synaptic depotentiation induced by low frequency stimuli (Zhu et al, 2005), metabotropic glutamate receptors (Zho et al, 2002) and neuregulin-1 (Kwon et al, 2005) at hippocampal CA1 synapses. It is known that GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors display pronounced inward rectification due to voltage-dependent block of the channel pore by polyamines (Bowie et al, 1995; Kamboj et al, 1995; Koh et al, 1995). Moreover, several lines of evidence indicate that the subunit composition of AMPA receptors changes during certain forms of hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Ho et al, 2007; Plant et al, 2006; Lu et al, 2007; Guire et al, 2008; Williams et al, 2007; Bagal et al, 2005: but see Adesnik and Nicoll 2007; Gray et al, 2007). Thus, in order to determine if leptin-induced depotentiation is due to alterations in the GluR2 content of synaptic AMPA receptors, the rectification properties of evoked EPSCs were monitored before and after application of leptin during whole cell recordings with spermine (0.1mM)-containing pipettes. In agreement with previous studies (Plant et al, 2006), 5 min after the induction of LTP the rectification index was increased from 1.05 ± 0.20 to 2.14 ± 0.19 (n=6; P<0.01).

Moreover 30 min after LTP induction the rectification index was maintained at an elevated level 1.91 ± 0.29 (n=6; P<0.01; Fig 6Ci). Subsequent application of leptin (50nM), 30 min after the induction of LTP, resulted in a reversal of potentiated EPSCs from 164.3 ± 8.1% to 98.2 ± 7.0 % of control (n=6; Fig 6B); an effect that was accompanied by a reduction in the rectification index to 1.06 ± 0.18 (n=6; P<0.05; Fig 6Ci). In an independent control pathway within the same experiments, there was no significant change in rectification index when measured at the same time points as the test pathway (data not shown). In control slices, LTP of EPSCs was accompanied by an increase in AMPA receptor rectification (to 2.63 ± 0.5); an effect that was maintained for up to 45 min after LTP induction (2.41 ± 0.4; n=8). The change in the rectification index caused by leptin suggests that the synaptic depression is associated with alterations in the GluR2 content of synaptic AMPA receptors. To test this further, the effects of the polyamine toxin, Philanthotoxin-433 (Koh et al, 1995; Toth and McBain, 1998), which blocks calcium-permeable GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors, were examined. Application of Philanthotoxin-433 (1 μM), 30 min after the induction of LTP, resulted in a significant reduction in EPSC amplitude from 208.2 ± 7.3% of baseline (25 min after LTP induction) to 107.1 ± 6.3% of baseline (n=6; P<0.01; 30 min after application of Philanthotoxin-433; Fig 6D,E). In contrast, philanthotoxin-433 had no effect on basal synaptic transmission (Fig 6D,E). Within this same set of experiments, LTP was associated with an increase in rectification (from 1.12 ± 0.1 to 1.61 ± 0.1; n=6; P<0.01) whilst philanthotoxin induced depotentiation was associated with a return to basal levels of rectification (1.06 ± 0.2; n=6). These data provide additional support that leptin-induced depotentiation is associated with a reduction in the proportion of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors at hippocampal CA1 synapses.

Figure 6. Leptin-induced depotentiation involves a change in the GluR2 content of hippocampal synapses.

A, Representative experiment plotting EPSC amplitude against time in which leptin depotentiates after LTP. Individual EPSC traces are shown in the upper panel taken from the time points indicated. The scale bars represent 50pA and 50ms respectively. Two independent pathways were stimulated, the test pathway (i.e. which received the LTP inducing stimuli at the time point indicated by the arrow) represented by the filled circles and the control pathway by the open circles. Cells were depolarized to +40 mV and then 0 mV at the times indicated by the filled bars and all recordings included spermine in the internal pipette solution. B, Pooled data of the above experiment (A). Ci, Pooled rectification indices from the same set of experiments depicted in B. Cii, Pooled initial slope measurements at +40 mV (filled bars; representing the AMPA receptor mediated component of the EPSC) and the amplitude (open bars; representing the NMDA receptor mediated component of the EPSC) from the same set of experiments depicted in B. D, Representative experiment plotting EPSC amplitude against time in which philanthotoxin depotentiates after LTP (layout and representation as above). E, Pooled data of the experiment shown in D. Fi, Pooled rectification indices from the same set of experiments depicted in E. Fii, Pooled initial slope measurements and amplitude measurements from the experiments depicted in E (layout and representation as in Cii).

During this set of experiments we also measured the NMDA receptor-mediated component of the EPSC at +40 mV. We found that there was a small, but non-significant increase in this component (15 ± 5%; n=12; P>0.05; Fig 6Cii & Eii) after LTP induction, and this was maintained during leptin application (16 ± 7%; n=6; P>0.05).

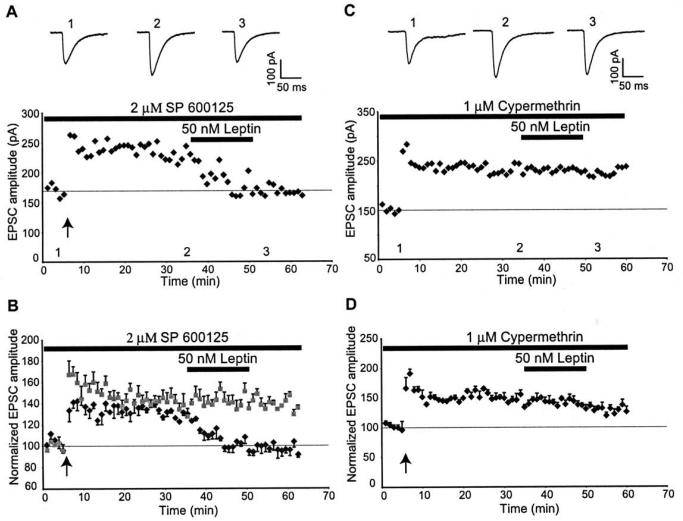

Calcineurin, but not JNK, activation is required for leptin-induced depotentiation

There is growing evidence that leptin, like other cytokines, has the ability to activate the stress activated protein kinase c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK; Shen et al, 2005; Onuma et al, 2003). In addition recent studies have shown that JNK activation promotes removal of AMPA receptors which in turn underlies depotentiation of hippocampal CA1 synapses (Zhu et al, 2005). Thus in the next series of experiments, the role of JNK in leptin-induced depotentiation was examined. In these studies slices were incubated with SP600125, an inhibitor of JNK, for at least 45 min prior to the depotentiation experiments. In control slices, exposure to SP600125 (2 μM) per se had no effect on the expression of LTP such that 30 min after high frequency stimulation the amplitude of EPSCs was 138 ± 9.0% of baseline (n=4; P<0.01; Fig 7B). Moreover, in slices incubated with the JNK inhibitor, the ability of leptin to depotentiate hippocampal CA1 synapses was unaffected such that after LTP induction, addition of leptin (50 nM: 15 min) result in a robust depression of EPSCs to pre-LTP levels (98.4 ± 5.8% of baseline; n=5; P>0.05 relative to baseline; Fig 7A&B). These data indicate that the leptin-induced depotentiation is mediated by a JNK-independent process.

Figure 7. The synaptic depotentiation induced by leptin is mediated by a calcineurin-dependent process.

A,B. JNK activation does not mediate leptin-induced depotentiation. A, Representative experiment illustrating the effects of leptin on potentiated synapses in the presence of the JNK inhibitor, SP 600125 (2 μM). Top, Example traces from the same experiment in A are shown for the time points indicated. B, Pooled and normalized data from all experiments in SP 600125-treated slices. Inhibition of JNK had no effect on LTP per se (grey diamond; n=4) or on the ability of leptin to depotentiate hippocampal synapses (black diamond; n=5). C,D, Leptin reversal of hippocampal LTP involves a calcineurin-sensitive process. C, Representative experiment demonstrating that inhibition of calcineurin attenuates the reversal of LTP by leptin. Top, Example traces from the same experiment in C are shown for the time points indicated. D, Pooled and normalized data from all experiments.

As a number of studies have identified a role for calcineurin in depotentiation of hippocampal LTP (Zhuo et al, 1999; Jouvenceau et al, 2003; Kang-Park et al, 2003), the possible role of this serine/threonine protein phosphatase was also examined. In control slices, application of the calcineurin inhibitor, cypermethrin (1 μM) had no effect on EPSC amplitude per se (n=4; Fig 7C&D). However, in slices exposed to cypermethrin, the ability of leptin to reverse hippocampal LTP was markedly attenuated such that application of leptin, 30 min after LTP induction, resulted in a reduction in EPSC amplitude from 145.6 ± 7.0 to 131.8 ± 5.2% of baseline (n=4; P>0.05; Fig 7C&D). Thus, these data indicate that a calcineurin-dependent process mediates leptin-induced depotentiation.

Discussion

There is growing evidence that, in addition to its prominent role in regulating energy homeostasis, the hormone leptin markedly influences hippocampal synaptic plasticity (see Harvey et al, 2006 for review). In the present study we provide the first compelling evidence that leptin has the capacity to reverse LTP at hippocampal CA1 synapses. The synaptic depotentiation induced by leptin was concentration-dependent as low concentrations of leptin failed to influence the magnitude of LTP, whereas at higher concentrations leptin readily reversed LTP at hippocampal CA1 synapses. Leptin-induced depotentiation was also time-dependent as leptin reliably reversed the potentiation of synapses 30 min, but not 50 min, after the induction of LTP. This time-dependency displays similarities to the depotentiation induced by neuregulin-1 as LTP was reversed 30 min, but not 50 min, after induction by neuregulin-1 (Kwon et al, 2005). In contrast, mGluRs can depotentiate hippocampal CA1 synapses an hour or more after LTP induction (Fitzjohn et al, 1998; Bashir and Collingridge, 1994; Delgado and O'Dell, 2005), suggesting that the cellular mechanisms underlying this process are distinct to those utilized by leptin. It is well documented that synaptic plasticity is strongly influenced by prior synaptic activity (known as metaplasticity; Abraham, 2008). The inability of leptin to depress potentiated synapses 50 min after LTP induction, suggests that a persistent change in the physiological or biochemical state of potentiated synapses has occurred that has altered the ability of leptin to reverse LTP. Although the cellular mechanisms underlying this metaplastic change are not known, it is feasible that alterations in NMDA receptor function or key signaling molecules plays a role in this process.

In this study the synaptic activation of NMDA receptors was required for leptin-induced depotentiation as the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist D-AP5 prevented the reversal of LTP by leptin. In addition, leptin-induced depotentiation was not associated with any significant change in the PPF ratio or the CV indicating that this phenomenon is likely to have a postsynaptic locus of expression. It is well established that trafficking of AMPA receptors into and out of the postsynaptic membrane is pivotal for various forms of activity-dependent hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Collingridge et al, 2004). Moreover, several lines of evidence indicate that changes in the molecular composition of AMPA receptors also occur during hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Isaac et al, 2007). Indeed recent studies indicate that hippocampal LTP is accompanied by a transient, rapid increase in the density of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors (Plant et al, 2006). In agreement with this, our present data show that LTP is associated with an initial increase in the rectification of AMPA receptors 5 min after LTP induction which is consistent with an increase in the proportion of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors at synapses. However, in contrast to Plant et al, (2006), the change in GluR2 content of AMPA receptors was sustained for the duration of recordings following LTP induction. These data indicate that under our recording conditions, LTP is associated with a robust, sustained increase in the density of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors at hippocampal CA1 synapses. Subsequent application of leptin, 30 min after LTP induction, resulted in reversal of LTP with a concomitant reduction in AMPA receptor rectification to pre-LTP levels. Moreover, application of Philanthotoxin-433, a selective inhibitor of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors, mimicked the effects of leptin on potentiated synapses indicting that leptin-induced depotentiation is associated with loss of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors from hippocampal CA1 synapses. Interestingly, the reversal of hippocampal LTP by either neuregulin-1β or mGluRs is reported to involve the selective internalization of GluR1-containing AMPA receptors (Kwon et al, 2005; Zho et al, 2002), whereas the synaptic removal of AMPA receptors with long cytoplasmic termini (GluR1, GluR2L) underlies the synaptic depotentiation induced by low frequency.

We have shown previously that NMDA receptor activation is a pre-requisite for the facilitation of hippocampal LTP and the novel form of hippocampal LTD induced by leptin (Shanley et al, 2001; Durakoglugil et al, 2005). NMDA receptor activation is also required for leptin receptor-dependent alterations in hippocampal dendritic morphology (O'Malley et al, 2007). In this study the ability of leptin to depotentiate hippocampal synapses was also NMDA receptor-dependent as D-AP5 completely blocked the ability of leptin to reverse LTP. Moreover, as a small increase in NMDA receptor currents was observed in the potentiated, but not control pathway, and this effect was maintained in the presence of leptin, it is likely that enhanced NMDA receptor activation is required for leptin-induced depotentiation. It is well documented that NMDA receptor activation promotes internalization of GluR1 subunits (Lee et al, 1998; Biou et al, 2008), and we have shown previously that leptin facilitates NMDA receptor-mediated responses in the hippocampus (Shanley et al, 2001). Thus it is feasible that leptin enhances NMDA receptor function which in turn promotes the removal of GluR1 subunits from hippocampal synapses. However, the cell signaling pathways linking leptin receptor activation to GluR1 internalisation are not entirely clear. A recent study has implicated the MAP kinase, JNK in NMDA receptor-dependent removal of AMPA receptors from synapses during hippocampal depotentiation (Zhu et al, 2005). Although leptin is capable of activating JNK in other cell types (Shen et al, 2005; Ogunwobi et al, 2006), the synaptic depotentiation induced by leptin in this study is unlikely to involve a JNK-dependent process as inhibition of JNK failed to alter the ability of leptin to reverse hippocampal LTP. The phosphorylation status of GluR1 is also critical for AMPA receptor trafficking and in particular dephosphorylation of serine 845 on GluR1 is pivotal for NMDA receptor-dependent internalization of AMPA receptors (Lee et al, 1998; Man et al, 2007). Furthermore, recent studies have implicated calcineurin (protein phosphatase 2B) in NMDA receptor-dependent endocytosis of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors (Biou et al, 2008; Beattie et al, 2000; Ehlers 2000). Thus it is possible that leptin promotes internalization of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors via activating calcineurin or another protein phosphatase. Consistent with this, the ability of leptin to depotentiate hippocampal synapses in this study was markedly attenuated following inhibition of calcineurin. The involvement of calcineurin in leptin-induced depotentiation parallels the role of this protein phosphatase in the synaptic depotentiation induced by low frequency stimulation (Zhuo et al, 1999; Jouvenceau et al, 2003). In contrast, however, calcineurin plays no role in mGluR-mediated depotentiation (Zho et al, 2002).

Several lines of evidence indicate that de novo LTD and depotentiation are distinct phenomenon. Indeed, in calcineurin Aα-knockout mice, depotentiation is absent whereas robust NMDA receptor-dependent LTD is observed (Zhuo et al, 1999). Recent studies have shown that activation of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors underlies de novo LTD whereas NR2A-containing NMDA receptors are implicated in depotentiation (Massey et al, 2004; Liu et al, 2004). There is also evidence that hippocampal LTD and depotentiation, by activating disparate signaling cascades, result in dephosphorylation of distinct sites on GluR1 (Lee et al, 2000). This has lead to the hypothesis that activation of different NMDA receptor subunits triggers the activation of divergent signaling cascades (Bayer et al, 2001; Li et al, 2002), which in turn underlies different forms of NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity. In support of this possibility, leptin evokes a novel form of NMDA receptor-dependent de novo hippocampal LTD (Durakoglugil et al, 2005); a phenomenon that requires the activation of signaling cascades that are distinct to those implicated in leptin-induced depotentiation. Indeed, in contrast to the present findings, leptin-induced LTD is negatively regulated by PI 3-kinase and protein phosphatases 1/2A (Durakoglugil et al, 2005). Thus it is feasible that leptin, by activating NMDA receptors composed of distinct subunit combinations, evokes different forms of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. However, the exact molecular composition of the NMDA receptors underlying leptin-induced LTD and depotentiation remain to be determined.

The hormone leptin circulates in the plasma in amounts proportional to body adiposity and it is transported to most brain regions via saturable transport across the blood brain barrier. Leptin mRNA and protein have also been identified in many brain regions, including the hippocampus (Morash et al, 1999), suggesting that leptin may be released locally in the CNS. Evidence is accumulating that leptin markedly influences the cellular events underlying learning and memory. Indeed leptin promotes the induction of hippocampal LTP (Shanley et al, 2001), evokes a novel form of LTD (Durakoglugil et al, 2005) and it rapidly alters the morphology of hippocampal dendrites (O'Malley et al, 2007). The ability of leptin to depotentiate hippocampal CA1 synapses provides additional evidence in support of a role for this hormone in regulating hippocampal synaptic plasticity. It is known that depotentiation results in the resetting of potentiated synapses which in turn increases the likelihood of subsequently generating LTP. Thus it is feasible that leptin, by depotentiating hippocampal CA1 synapses, indirectly facilitates the induction of LTP and thereby is likely to enhance the efficiency of information storage in the network.

Cognitive deficits have been reported in leptin-insensitive rodents (Li et al, 2002) and are also prevalent in diseases associated with leptin resistance such as type II diabetes (Gispen and Biessels, 2000). Alterations in leptin levels may also play a role in neurodegenerative conditions as Alzheimer's disease patients have depressed levels of this hormone (Power et al, 2001). Moreover in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease, leptin significantly attenuates amyloid β levels (Fewlass et al, 2004) and it facilitates memory processing (Farr et al, 2006). Thus as obesity and obesity-related diseases such as type II diabetes are associated with leptin resistance at the level of the blood brain barrier, leptin resistance is likely to contribute to the reported cognitive impairments in diabetes and certain neurodegenerative disorders. Thus the capacity of leptin to depotentiate hippocampal CA1 synapses has important implications not only for normal CNS function but also for CNS-driven diseases linked to leptin resistance.

Acknowledgements

This worked is supported by The Wellcome Trust (075821) and Medical Research Scotland.

References

- Abraham WC. Metaplasticity: tuning synapses and networks for plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9(5):387. doi: 10.1038/nrn2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adesnik H, Nicoll RA. Conservation of glutamate receptor 2-containing AMPA receptors during long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:4598–602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0325-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WW, Collingridge GL. The LTP Program: a data acquisition program for on-line analysis of long-term potentiation and other synaptic events. J. Neurosci Methods. 2001;108:71–83. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai A, Larson J, Lynch G. Anoxia reveals a vulnerable period in the development of long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 1990;511:353–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90184-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagal AA, Kao JP, Tang CM, Thompson SM. Long-term potentiation of exogenous glutamate responses at single dendritic spines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14434–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501956102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir ZI, Collingridge GL. An investigation of depotentiation of long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Exp. Brain Res. 1994;100:437–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02738403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer KU, De Koninck P, Leonard AS, Hell JW, Schulman H. Interaction with the NMDA receptor locks CaMKII in an active conformation. Nature. 2001;411:801–5. doi: 10.1038/35081080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie EC, Carroll RC, Yu X, Morishita W, Yasuda H, von Zastrow M, Malenka RC. Regulation of AMPA receptor endocytosis by a signaling mechanism shared with LTD. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:1291–300. doi: 10.1038/81823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biou V, Bhattacharyya S, Malenka RC. Endocytosis and recycling of AMPA receptors lacking GluR2/3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:1038–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711412105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie D, Mayer ML. Inward rectification of both AMPA and kainate subtype glutamate receptors generated by polyamine-mediated ion channel block. Neuron. 1995;15:453–462. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Wang YT. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:952–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado JY, O'Dell TJ. Long-term potentiation persists in an occult state following mGluR-dependent depotentiation. Neuropharmacol. 2005;48:936–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durakoglugil M, Irving AJ, Harvey J. Leptin induces a novel form of NMDA receptor-dependent long-term depression. J. Neurochem. 2005;95:396–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers MD. Reinsertion or degradation of AMPA receptors determined by activity-dependent endocytic sorting. Neuron. 2000;28:511–25. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr SA, Banks WA, Morley JE. Effects of leptin on memory processing. Peptides. 2006;27:1420–5. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fewlass DC, Noboa K, Pi-Sunyer FX, Johnston JM, Yan SD, Tezapsidis N. Obesity-related leptin regulates Alzheimer's Abeta. FASEB J. 2004;18:1870–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2572com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzjohn SM, Bortolotto ZA, Palmer MJ, Doherty AJ, Ornstein PL, Schoepp DD, Kingston AE, Lodge D, Collingridge GL. The potent mGlu receptor antagonist LY341495 identifies roles for both cloned and novel mGlu receptors in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacol. 1998;37:1445–58. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gispen WH, Biessels GJ. Cognition and synaptic plasticity in diabetes mellitus. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:542–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EE, Fink AE, Sariñana J, Vissel B, O'Dell TJ. Long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region does not require insertion and activation of GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;98:2488–92. doi: 10.1152/jn.00473.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guire ES, Oh MC, Soderling TR, Derkach VA. Recruitment of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors during synaptic potentiation is regulated by CaM-kinase I. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:6000–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0384-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvenceau A, Billard JM, Haditsch U, Mansuy IM, Dutar P. Different phosphatase-dependent mechanisms mediate long-term depression and depotentiation of long-term potentiation in mouse hippocampal CA1 area. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;18:1279–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey J. Leptin regulation of neuronal excitability and cognitive function. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2007;7:643–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey J, Solovyova N, Irving A. Leptin and its role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006;45:369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho MT, Pelkey KA, Topolnik L, Petralia RS, Takamiya K, Xia J, Huganir RL, Lacaille JC, McBain CJ. Developmental expression of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors underlies depolarization-induced long-term depression at mossy fiber CA3 pyramid synapses. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:11651–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2671-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Hsu KS. Progress in understanding the factors regulating reversibility of long-term potentiation. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;12:51–68. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2001.12.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Liang YC, Hsu KS. Characterization of the mechanism underlying the reversal of long term potentiation by low frequency stimulation at hippocampal CA1 synapses. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48108–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JT, Ashby M, McBain CJ. The role of the GluR2 subunit in AMPA receptor function and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54:859–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj SK, Swanson GT, Cull-Candy SG. Intracellular spermine confers rectification on rat calcium-permeable AMPA and kainate receptors. J. Physiol. 1995;486:297–303. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang-Park MH, Sarda MA, Jones KH, Moore SD, Shenolikar S, Clark S, Wilson WA. Protein phosphatases mediate depotentiation induced by high-intensity theta-burst stimulation. J. Neurophysiol. 2003;89:684–90. doi: 10.1152/jn.01041.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh DS, Burnashev N, Jonas P. Block of native Ca(2+)-permeable AMPA receptors in rat brain by intracellular polyamines generates double rectification. J Physiol. 1995;486:305–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM. Amplitude fluctuations of dual-component EPSCs in hippocampal pyramidal cells: implications for long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1994;12:111–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon OB, Longart M, Vullhorst D, Hoffman DA, Buonanno A. Neuregulin-1 reverses long-term potentiation at CA1 hippocampal synapses. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:9378–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2100-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Kameyama K, Huganir RL, Bear MF. NMDA induces long-term synaptic depression and dephosphorylation of the GluR1 subunit of AMPA receptors in hippocampus. Neuron. 1998;21:1151–62. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Barbarosie M, Kameyama K, Bear MF, Huganir RL. Regulation of distinct AMPA receptor phosphorylation sites during bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Nature. 2000;405:955–9. doi: 10.1038/35016089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Chen N, Luo T, Otsu Y, Murphy TH, Raymond LA. Differential regulation of synaptic and extra-synaptic NMDA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:833–4. doi: 10.1038/nn912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XL, Aou S, Oomura Y, Hori N, Fukunaga K, Hori T. Impairment of long-term potentiation and spatial memory in leptin receptor-deficient rodents. Neurosci. 2002;113:607–15. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Wang Y, Sheng M, Auberson YP, Wang YT. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2004;304:1021–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1096615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Allen M, Halt AR, Weisenhaus M, Dallapiazza RF, Hall DD, Usachev YM, McKnight GS, Hell JW. Age-dependent requirement of AKAP150-anchored PKA and GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors in LTP. EMBO J. 2007;26:4879–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man HY, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Huganir RL. Regulation of {alpha}-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor trafficking through PKA phosphorylation of the Glu receptor 1 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:3579–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611698104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe T, Wyllie DJ, Perkel DJ, Nicoll RA. Modulation of synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation: effects on paired pulse facilitation and EPSC variance in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1451–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey PV, Johnson BE, Moult PR, Auberson YP, Brown MW, Molnar E, Collingridge GL, Bashir ZI. Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in cortical long-term potentiation and long-term depression. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:7821–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1697-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morash B, Li A, Murphy PR, Wilkinson M, Ur E. Leptin gene expression in the brain and pituitary gland. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5995–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunwobi O, Mutungi G, Beales IL. Leptin stimulates proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in Barrett's esophageal adenocarcinoma cells by cyclooxygenase-2-dependent, prostaglandin-E2-mediated transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4505–16. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley D, MacDonald N, Mizielinska S, Connolly CN, Irving AJ, Harvey J. Leptin promotes rapid dynamic changes in hippocampal dendritic morphology. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007;35:559–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuma M, Bub JD, Rummel TL, Iwamoto Y. Prostate cancer cell-adipocyte interaction: leptin mediates androgen-independent prostate cancer cell proliferation through c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42660–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power DA, Noel J, Collins R, O'Neill D. Circulating leptin levels and weight loss in Alzheimer's disease patients. Dement. Geriatr. 2001;12:167–70. doi: 10.1159/000051252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant K, Pelkey KA, Bortolotto ZA, Morita D, Terashima A, McBain CJ, Collingridge GL, Isaac JT. Transient incorporation of native GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors during hippocampal long-term potentiation. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:602–4. doi: 10.1038/nn1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley LJ, Irving AJ, Harvey J. Leptin enhances NMDA receptor function and modulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:RC186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley LJ, O'Malley D, Irving AJ, Ashford ML, Harvey J. Leptin inhibits epileptiform-like activity in rat hippocampal neurones via PI 3-kinase-driven activation of BK channels. J. Physiol. 2002;545:933–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Sakaida I, Uchida K, Terai S, Okita K. Leptin enhances TNF-alpha production via p38 and JNK MAPK in LPS-stimulated Kupffer cells. Life Sci. 2005;77:1502–15. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stäubli U, Chun D. Factors regulating the reversibility of long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:853–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00853.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth K, McBain CJ. Afferent specific innervation of two distinct AMPA receptor subtypes on single hippocampal interneurones. Nat. Neurosci. 1998;1:572–8. doi: 10.1038/2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Guévremont D, Mason-Parker SE, Luxmanan C, Tate WP, Abraham WC. Differential trafficking of AMPA and NMDA receptors during long-term potentiation in awake adult animals. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:14171–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2348-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zho WM, You JL, Huang CC, Hsu KS. The group I metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine induces a novel form of depotentiation in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:8838–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08838.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Pak D, Qin Y, McCormack SG, Kim MJ, Baumgart JP, Velamoor V, Auberson YP, Osten P, van Aelst L, Sheng M, andZhu JJ. Rap2-JNK removes synaptic AMPA receptors during depotentiation. Neuron. 2005;46:905–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M, Zhang W, Son H, Mansuy I, Sobel RA, Seidman J, Kandel ER. A selective role of calcineurin aalpha in synaptic depotentiation in hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1999;96:4650–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]