Abstract

In translational bypassing, a peptidyl-tRNA::ribosome complex skips over a number of nucleotides in a messenger sequence and resumes protein chain elongation after a “landing site” downstream of the bypassed region. The present experiments demonstrate that the complex “scans” processively through the bypassed region. This conclusion rests on three observations. (i) When two potential “landing sites” are present, the protein sequence of the product shows that virtually all ribosomes land at the first and virtually none at the second. (ii) In such a sequence with two landing sites, the presence of a terminator triplet in phase in the coding region immediately after the first landing site drastically reduces the efficiency of bypassing. (iii) Internally complementary sequences that can form a stable stemloop in the bypassed region significantly reduce the efficiency of bypassing. We analyze bypassing from a given “takeoff” site to “landing sites” at different distances downstream so as to derive estimates of the frequency of ribosome takeoff and of the stability of the bypassing complex.

In “translational bypassing,” a ribosome skips over a number of nucleotides in a messenger sequence so as to join the information from two noncontiguous ORFs into the sequence of a single, continuous polypeptide chain (reviewed in ref. 1). The prototypical case has been the translation of the phage T4 gene 60 mRNA coding for a topoisomerase subunit, which involves the bypassing of a 50-nt untranslated segment (or “coding gap”) between a GGA “takeoff” triplet and a GGA “landing site” triplet. (In the text, we use boldface to show RNA triplets and normal type for triplets or other sequences in DNA.) This case of bypassing depends on very specific features of the sequence (1-3): (i) identity of the takeoff and landing site triplets, implying that peptidyl-tRNA is what makes the trip; (ii) optimum spacing of the takeoff and landing sites; (iii) a terminator triplet immediately 3′ of the takeoff triplet; (iv) a stem-loop of optimal stability and placement in the region after the takeoff site; and (v) a particular amino acid sequence of the peptide encoded in a region 5′ of the takeoff site. The role of these sequence elements and of participating factors has been investigated in detail (1, 4-6).

The sequence rules governing this kind of bypass event seem very constraining. We have reported on a type of bypass event that seems to be subject to more relaxed rules and may therefore occur on a wide variety of sequences. This is a bypass induced by ribosome pausing at a “hungry” codon calling for an aminoacyl-tRNA in short supply (7, 8). We showed that this kind of bypass shared with the gene 60 case only the requirement for synonymous takeoff and landing sites. Otherwise, it could be demonstrated over various coding gap distances (from 7 to at least 40 nt), and seemed largely independent of the sequence in the coding gap and upstream of it (7). In those experiments and the present ones, we inhibited the activation of isoleucine with isoleucine-hydroxamate (ILHX), thus inducing ribosomes to pause at a hungry AUA codon immediately following a UUC takeoff site. Protein sequencing of the product established the occurrence of bypassing from the takeoff site to synonymous landing sites located at various downstream positions (7).

The data reported previously demonstrate that the ribosome::peptidyl-tRNA complex departs from the takeoff codon and resumes protein chain elongation immediately after the synonymous landing site codon. It seems intuitively likely that the complex slides through the intervening or coding gap region while remaining associated with the mRNA and influenced by elements in its sequence, a model Herr et al. (1) refer to as “scanning.” However, it remains conceivable that the ribosome::peptidyl-tRNA complex detaches completely from the message and somehow hops over the coding gap to reengage at the landing site, a theoretical possibility that the authors of the aforementioned review term “bridging.”

In the present communication, we report on experiments designed to distinguish between these two formal models by showing that the ribosome::peptidyl-tRNA complex can interact with elements in the bypassed region and that it encounters these elements sequentially along the length of the coding gap. Our results demonstrate that the complex does scan through the coding gap sequence, although in a mode that precludes normal translation. We have also examined the effect near the landing site of the tetranucleotide AGCT, hypothesized to be a frame-keeping motif (9), and found that it has no effect on bypassing efficiency in our example. Further consideration of the bypassing phenomenon leads to the hypothesis that codon::anticodon matching in the P-site strongly influences the ability of the adjacent A-site to accept aminoacyl-tRNA.

Materials and Methods

All bypass reporter constructs were made by force-cloning appropriate oligonucleotides with HindIII and BamHI overhangs into plasmid pEK-0F, as described (7). Reporter plasmids were transfected into host strain C92 (relA spoT) carrying the O6 deletion of the early part of lacZ (10), and selected and analyzed as described (7, 11). To confirm the engineered lacZ sequences of the constructs, ≈600-bp PCR products were amplified (using primers flanking the oligonucleotide insert) and sequenced at the University of Washington Biochemistry DNA Sequencing Facility. Cultivation of cells (M63-glucose minimal medium, 37°C, forced aeration) was as described except that there were no amino acid supplements. The lac promoter was induced in log-phase cultures at an OD690 of ≈0.2 by the addition of 2 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 2.5 mM cAMP, and subcultures were grown in parallel in the absence and presence of 72 μg/ml ILHX to inhibit isoleucine-tRNA charging. In all experiments, the glucose concentration was 0.07%, which limits growth in ILHX to about one doubling (an increase of ≈40 μg/ml protein from the point at which we induce); inhibited cultures were followed long enough to confirm growth inhibition, typically 3-fold, and then allowed to continue bubbling overnight, during which glucose was exhausted and growth ceased, and the cultures were harvested the next morning. Samples were processed for enzyme and protein assay, and for β-galactosidase purification and amino acid sequence analysis, as described by Barak et al. (11). Enzyme and protein assays, and calculations, were as described by Lindsley et al. (8). One enzyme unit corresponds to the quantity of enzyme that yields a rate of change of optical density at 420 nm of 1.0 per minute under the specified assay conditions; milli-enzyme units are presented for convenience. Predicted secondary structures in mRNA, and their stabilities, were generated by rnastructure Version 3.71 software (12).

Results

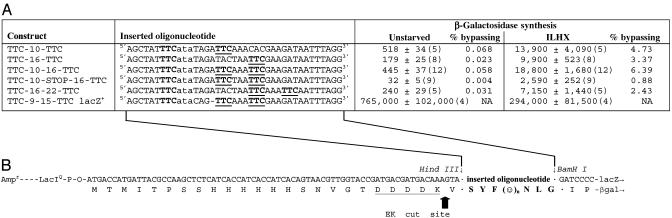

Bypassing on Sequences with Two In-Frame Landing Sites. To discriminate between “scanning” and “bridging,” we have asked how the bypassing process responds to certain kinds of sequence information within the coding gap. In the first such test, we examined starvation-inducible bypassing on a sequence with two potentially productive landing sites. Fig. 1 shows that bypassing from a TTC takeoff site occurs at similar frequencies whether a single TTC landing site is located 10 or 16 nt downstream, corresponding to 3-5% of the lacZ+ control. To determine whether the ribosome::peptidyl-tRNA complex passes through position 10 on the way to position 16, we made the third construct listed in Fig. 1 A, possessing both of these landing sites. Starvation-induced bypassing on this construct occurred with an efficiency (6.4%) that was slightly higher than, but in fact not statistically distinguishable from, that on the construct with a single landing site 10 nt after the takeoff site (Fig. 1). To determine which landing sites were used when these two were available, we determined the amino acid sequence of the protein generated through starvation-induced bypassing.

Fig. 1.

Bypassing efficiencies of constructs with one or two in-frame landing sites. (A) Shown are the oligonucleotide inserts cloned into the lacZ gene of the vector to make each construct and its rate of reporter β-galactosidase synthesis. The oligonucleotide inserts (shown as coding strand only) were ligated between the HindIII and BamHI sites, replacing a 20-mer of the pEK-0f vector, as described in Materials and Methods. The TTC takeoff and landing site triplets are shown in bold type, with the latter underlined; the hungry ata codon (coding for isoleucyl-tRNA) is shown in lowercase; a dash is used as a spacer between contiguous nucleotides in the lacZ+ control construct, to keep all sequences aligned. ILHX refers to subcultures subjected to 72 μg/ml ILHX to partly inhibit the attachment of isoleucine to its cognate tRNAs. β-Galactosidase synthesis was measured over about one mass doubling after induction. It is expressed as induced specific activity or increase in β-galactosidase activity divided by increase in protein, in milli-enzyme units/mg protein; the averages of the number of replicate experiments shown in parentheses, ± SEMs, are tabulated. [The minor difference in ILHX-stimulated β-galactosidase between TTC-10-TTC (13,900) and TTC-10-16-TTC (18,800) is not significant (t = 1.33, P = 0.20).] The % bypassing is the induced specific activity of the bypass reporter divided by the corresponding value in the lacZ+ construct (TTC-9-15-TTC lacZ+), which has a sequence closely similar to the bypass reporters but codes in-frame for β-galactosidase. (B) Shown is the relevant region of the vector's lacZ gene (coding strand), with lines from A indicating the insertion of the oligonucleotides into the cloning sites. The translation product shown below has the enterokinase (EK) recognition sequence underlined and the cleavage site marked by an arrow. The translation product of the inserted oligo (boldface) always includes S-Y-F, then a variable sequence of n amino acids symbolized as ()n, and then N, L, and a G encoded at the BamHI site.

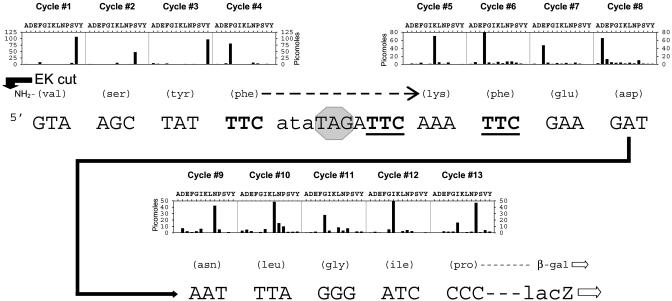

If the complex hops or “bridges” to independent landing sites, then the resulting protein should be a mixture of two species, reflecting independent landings, some at position 10 and some at position 16. The protein sequence signal in that case would be uniform up to the F at the takeoff site, but, after that, it would show two predominant species, corresponding to the two landing sites. However, if the complex slides or scans through the bypassed region, then it must reach position 10 first. If the efficiency of landing is high, then the protein sequence should resume uniformly at the codon following that at position 10. The protein sequence data shown in Fig. 2 unequivocally favor the second interpretation. A secondary signal of protein that resumed chain elongation at position 16 would be detectable if it represented as much as 10% of the total, and no such signal is apparent. We conclude that essentially all of the ribosomes resume protein chain elongation at position 10 rather than position 16, as they would naturally do if they moved through the coding gap and therefore always encountered position 10 first.

Fig. 2.

Amino acid sequence of the bypass region of β-galactosidase encoded by a bypass reporter with two landing sites. A 2-liter culture of cells harboring construct TTC-10-16-TTC was subjected to ILHX inhibition for approximately one doubling. The β-galactosidase was purified, cut with enterokinase (EK), separated by PAGE, and blotted to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane as described (7). The blotted protein was subjected to automated Edman sequence analysis at the Molecular Genetics Instrumentation Facility of the University of Georgia. Shown is the nucleotide sequence of the DNA-coding strand starting at the 3′ (or C-terminal) side of the region encoding the EK cleavage site. The hungry ata codon, subject to aminoacyl-tRNA limitation, is shown in lowercase; there are no other ata codons in the lacZ-coding sequence. The TTC takeoff site and both TTC landing sites are shown in bold type, with the latter underlined; and the terminator blocking the initial reading frame is overlaid by a hexagonal “stop” sign. The amino acid encoded is specified in parentheses above each relevant triplet. The cycle bar plot presents lag-corrected pmols, summed from three sequencing runs on two independent blots. Each cycle of the cycle bar plot is aligned over the triplet encoding that cycle's amino acid signal, with a dashed arrow over the coding gap. The amino acid signal begins with the valine residue on the C-terminal side of the EK cleavage site.

This interpretation predicts that a terminator codon placed after the landing site at position 10 should abolish bypassing in a two-landing-site construct. In fact, bypassing on this construct (the fourth entry in Fig. 1 A) was not quite abolished altogether, but it was reduced from 6.4% to 0.88%. This large reduction supports the conclusion from protein sequencing that the great majority of ribosomes resume chain elongation at the first of the two landing triplets. The small residual activity suggests that a small minority of ribosomes, of the order of 14%, either can pass through a landing site triplet (without resuming chain elongation and then land at a more distal landing triplet) or can hop or bridge directly from the takeoff site to the more distal landing site. A third possibility is that all of the ribosome::peptidyl-tRNA complexes did land at position 10, but that the immediately following terminator induced 14% of them to bypass a second time to the distal landing site. The protein sequence of the residual enzyme produced in construct TTC-10-STOP-16-TTC was determined (not shown); it lacked any of the amino acids encoded between the takeoff site and the distal landing site at position 16, which is consistent with any of these three explanations.

To test the generality of preferential landing at the first of two landing sites, we also constructed TTC-16-22-TTC (Fig. 1), and purified the β-galactosidase produced during ILHX-inhibited growth. The amino acid sequence of this protein (not shown) demonstrated that essentially 100% of the landings were at position 16, and again no secondary signal of landings at the second site, that at position 22, were detectable.

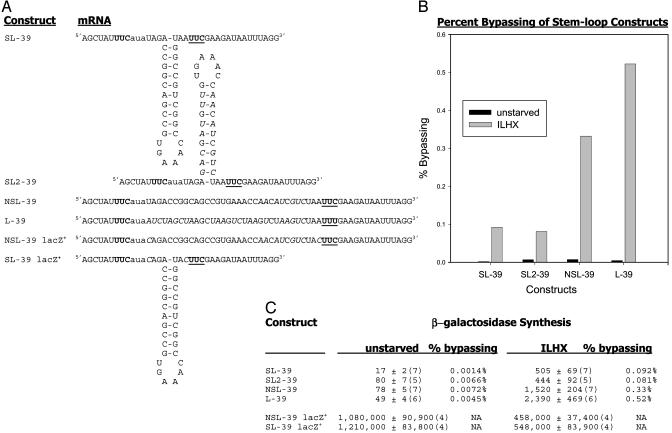

The Effect of Secondary Structure in the Coding Gap. If the ribosome::peptidyl-tRNA does scan through the bypass region, its progress might be affected by noncoding structural features of the region's sequence, such as a stable stem/loop. We therefore compared the efficiency of bypassing in the set of constructs shown in Fig. 3. One, termed SL-39, has internally complementary sequences in the 39-nt coding gap so as to form a very stable stem/loop (-24 kcal, according to the rnastructure program). A second construct, NSL-39, differs from SL-39 at seven positions in the downstream arm of the stem so that no stable secondary structure can be formed. Next, we changed the upstream part of the stem to nucleotides complementary to those in the downstream arm region of NSL-39 so as to generate a new stem/loop construct named SL2-39; this construct forms a stem/loop(-16 kcal) in the same position as SL39, but of very different sequence. For bypass constructs SL-39 and NSL-39, we made corresponding lacZ+ controls, as shown in Fig. 3. Finally, we indicate the sequence of L-39, on which we reported earlier (7). In this construct, there is also no expected secondary structure, but the coding gap sequence is very different from that of NSL-39. Fig. 3C reports enzyme synthesis in all these constructs, both the very low values during normal growth and the much higher values during isoleucyl-tRNA limitation to stimulate bypassing at the hungry AUA codon.

Fig. 3.

The effect of secondary structure on bypassing. (A) Shown is the RNA transcript of the inserted oligonucleotide portion of the lacZ gene of each construct, to display predicted mRNA secondary structures. The takeoff and landing UUC codons are shown in bold type, with the latter underlined; the hungry aua codon is in lowercase. In the sequence of each construct after SL-39, bases that differ from SL-39 are in italic type. (B) Displayed are the percent bypassing, defined as the induced specific activity of the bypass reporter under the specified condition divided by that of the corresponding lacZ+. Filled bars, unstarved controls; gray bars, ILHX inhibited. (C) The mean induced specific activities of β-galactosidase are as in Fig. 1 for each case analyzed, with SEM; the number of replicates is in parentheses. The significance of the differences between the ILHX-specific activities was evaluated by t test. For the difference between SL-39 and NSL-39, t = -4.7 and P < 0.005; for the difference between SL2-39 and NSL-39, t = -4.2 and P < 0.002. The modest difference between the two constructs with no stem/looop, L-39 and NSL-39, is not significant: t = 1.795 and P = 0.10.

It can be seen that starvation-induced enzyme synthesis in both SL-39 and SL2-39 was >3.0 times lower than it was in NSL-39, a highly significant difference (see the statistics quoted in the legend to Fig. 3). However, in the corresponding lacZ+ controls, there is no significant difference between the SL and the NSL constructs. It follows that the stem/loop sequence does not detectably affect lacZ expression or normal translation. Rather, the effect on enzyme synthesis encoded by the bypass reporters must reflect an effect on the bypassing process specifically. Fig. 3B displays the bypassing efficiencies, defined as enzyme synthesis in a bypass construct divided by that in the corresponding lacZ+ construct under the same conditions. Note the large difference between the starvation-induced bypassing efficiencies of both stem/loop constructs, on the one hand, and NSL39, on the other.

We conclude that productive bypassing is markedly reduced by some aspect of the sequence difference between both of the SL constructs and NSL-39. The difference from NSL-39 that both SL constructs share is, of course, the presence of a stem/loop. The identical, low-bypassing efficiencies of the two SL constructs suggest that the existence of a stem/loop, rather than its precise sequence, is what matters.

Other features of the coding gap sequence seem much less relevant. The two constructs without a stem/loop, NSL39 and L39, differ from each other at 22 of 39 positions in the coding gap. Nonetheless, they both display high bypassing efficiencies, not statistically distinguishable from one another, but much higher than that of the two SL constructs which contain a stem/loop.

Is AGCT a Frame-Keeping Marker? Henaut et al. (9), on the basis of genomic survey information, have suggested that the tetranucleotide motif AGCT might be a framekeeping signal in translation. Our system provides one way to test this proposal. The sequence on which we first demonstrated a highly efficient, 16-nt bypass had, as it happens, an AGCT in the coding gap, 2 nt before the landing site. To test whether the motif plays any role in correct landing, we have made another construct in which the AGCT tetranucleotide was replaced by GAGT. As Table 1 shows, the bypassing efficiency on the two sequences showed no significant difference. We made another pair of constructs in which the takeoff/landing site pair are TAC, one of which has AGCT 2 nt upstream of the landing site while the other has GAGT at the same position. These two constructs also showed identical bypassing efficiency (Table 1).

Table 1. Activity of bypass constructs with and without AGCT tetranucleotide.

| β-Galactosidase synthesis

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Inserted oligonucleotide | Unstarved | ILHX |

| L-16 (+ AGCT) | 5′-AGCTATTTCataATCT [AGCT] AATTTGAAGATAATTTAGG-3′ | 214 ± 15 (4) | 17,400 ± 1,280 (4) |

| L-16 (no AGCT) | 5′-AGCTATTTCataATCT [GAGT] AATTTGAAGATAATTTAGG-3′ | 278 ± 31 (4) | 27,200 ± 4,460 (4) |

| TAC-16-TAC (+ AGCT) | 5′-AGCTATTACataATCT [AGCT] AATACGAAGATAATTTAGG-3′ | 348 ± 34 (15) | 21,800 ± 4,510 (10) |

| TAC-16-TAC (no AGCT) | 5′-AGCTATTACataATTT [GAGT] GATACGAAGATAATTTAGG-3′ | 272 ± 23 (5) | 20,700 ± 2,690 (4) |

The bypass sequences shown are the coding strands of the oligonucleotides. The TTC takeoff and TTT landing sites are shown in boldface, with the latter underlined, and the hungry ata codon is in lowercase; the AGCT tetranucleotide and the GAGT replacing it are bracketed. Induced specific activies of β-galactosidase are as in Fig. 1. β-Galactosidase synthesis is expressed as induced specific activity or increase in β-galactosidase activity divided by increase in protein, in milli-enzyme units/mg protein; the averages of the number of replicate experiments shown in parentheses, ± SEMs, are tabulated.

Discussion

Our findings argue that the ribosome::peptidyl-tRNA complex gets from the takeoff site to the landing site by scanning processively through the untranslated coding gap. When two productive, landing triplets in frame with the reporter lacZ sequence are available, the protein sequence shows that all of the ribosomes resume protein chain elongation at the first landing triplet and virtually none at the second; this finding argues that no ribosomes can reach the second landing triplet that have not already interacted with the first, i.e., processivity. The finding also indicates that very few ribosomes scan past a productive landing site. Precisely the same conclusions follow from the much diminished bypassing we detected in a two-landing site construct with a terminator codon after the first landing site. It showed an 86% reduction in bypassing, suggesting that the efficiency of landing at the first, nonproductive landing site was 0.86 among scanning ribosomes. However, the residual 14% activity measured in this construct did not show up as a 14% secondary signal in the protein sequence data (Fig. 2), which, of course, comes from a two-landing-site construct without the terminator. We speculate that the presence of a terminator triplet immediately after the first landing site stimulated an additional hop to the second landing site at a low frequency, similar to the original description of low-level bypassing by Weiss et al. (13). In any case, this is a minor discrepancy, and the strong conclusion from both experiments remains that very few ribosomes go past a potential landing site to reach a second one. In other words, once a scanning peptidyl-tRNA::ribosome complex reaches a cognate landing site, the probability that it will resume protein chain elongation there rather than continue scanning is at at least 0.86 and probably closer to 1.0.

Let us consider the probabilities that enable bypassing over a distance of n nucleotides. First, a ribosome::peptidyl-tRNA complex must disengage from the messenger at the takeoff site; call that probability PT. Once a complex has disengaged, it must survive in a state capable of resuming protein chain elongation as it moves through n nucleotides; call that probability PS,n. Finally, the scanning ribosome must resume chain elongation (i.e., land) at the specified landing site rather than continue scanning, probability PL. Thus, the joint probability of successful bypassing from a given takeoff site to a given landing site n nucleotides downstream is

|

1 |

As we have seen above, PL is close to 1.0 for the present case. We find that PB,n decreases with n, reflecting the instability of the scanning complex. Let us make the simplest assumption that the inactivation of the complex as it traverse n nucleotides of coding gap is a first-order decay process with a decay constant proportional to the number of nucleotides. (This formulation is equivalent to assuming a random inactivation with a probability proportional to the number of nucleotides.) In other words, PS,n = e-kn. Therefore,

|

2 |

Because all our constructs have precisely the same takeoff sequence, they must share the same value of PT. As a result of this identity, we can estimate both PT and k from the decline in PB,n in our constructs with different values of n.

PB,n for L-39 (in which we earlier demonstrated the bypass through direct amino acid sequencing) is 0.0057 (Fig. 3). PB,n for TTC-10-16-TTC (in which the present sequence data demonstrate that all landings were at position 10) is 0.064 (Fig. 1). Therefore,

|

3 |

Solving the two simultaneous equations yields PT = 0.15, and k = 0.084. Thus, our ILHX inhibition regime induces ≈15% of the peptidyl-tRNA::ribosome complexes that encounter the hungry codon to take off, and, as they move through the coding gap, they are inactivated at an average rate of about one hit per 12 nt moved. In the case of the background, unstarved bypassing, we do not have direct protein sequence data to confirm that enzyme activity reflects the expected bypass event. Nonetheless, assuming that it does, we can solve the corresponding pair of simultaneous equations for the background values of PB, which are 0.000045 and 0.00058, respectively. The solutions are PT = 0.0014 and k = 0.088. Thus, ILHX inhibition increases the probability of takeoff 100-fold, but, as one would expect, has no effect on k.

The inactivating hits subsumed in the PS,n (or e-kn) term comprise all events that disqualify the complex from resuming protein chain elongation at a potential landing site. We assume that most hits are simple dissociation of the peptidyl-tRNA from the ribosome; the continuous generation of peptidyl-tRNA (detected after thermal inactivation of peptidyl-hydrolase) has long been known to occur (14). An unknown proportion of the hits may be scavenging of the peptidyl-tRNA::ribosome complex by the SsrA-RNA system (refs. 15 and 16, and reviewed in ref. 17) whereas another unknown proportion undoubtedly reflects unproductive landings at noncognate, out-of-frame landing sites (refs. 1 and 5, and J.G. and D.L., unpublished experiments). Menninger (14) has estimated the rates of dissociation of various peptidyl-tRNAs during translation as lying between 0.00013 and 0.004 per elongation cycle. Our estimate that the peptidyl-tRNA::ribosome complex decays with a probability of ≈0.084 per nucleotide moved implies that the bypassing complex is much less stable than the translating ribosome.

What determines the stability of the bypassing complex? The experiments of Fig. 3 demonstrate that secondary structure in the coding gap has a systematic effect. On the other hand, sequence differences other than secondary structure seem to have little or no effect. There is no difference in bypassing efficiency between SL-39 and SL2-39, which have stems of different sequence; nor is there much difference between the high-bypassing efficiencies of NSL-39 and L-39, which have very different sequences in the coding gap, but no secondary structure. In our previous report (7), we found identical bypassing efficiencies over a 22-nt coding gap in two constructs that differed at six positions in the gap. In other experiments, we have found identical bypassing efficiencies over a 16-nt coding gap in constructs differing by as many as five positions (unpublished experiments). Taken together, these comparisons strongly suggest that primary sequence in the bypass region has little effect on the efficiency of bypassing (and therefore the stability of the bypassing complex) unless it permits a secondary structure to form.

Most likely, stem/loop structures simply decrease the rate of ribosome movement through the coding gap, thereby allowing more time for the peptidyl-tRNA::ribosome complex to dissociate. We might note that the same stem/loop that diminished bypassing had no effect on normal lacZ expression and enzyme synthesis from a lacZ+ control sequence. Thus, if the translating ribosome is slowed down by secondary structure while traversing this region of this message, the decrease is too small relative to the transit time for the entire coding sequence to affect protein yield significantly. This observation comes as no surprise, inasmuch as the 39-nt region in question represents <1.5% of the entire length of the lacZ-coding sequence. In a bypass reporter, in contrast, the 39-nt distance becomes critical precisely because of the instability of the bypassing complex: it must get through the coding gap before peptidyl-tRNA dissociates (or SsrA RNA is recruited) to resume translation at the landing site.

The present results seem to differ strikingly from the T4 gene 60 system, wherein a stem/loop structure stimulates rather than diminishes bypassing. In the gene 60 case, however, the bypassing signal must include a terminator sequence (UAG C) that is poorly recognized by release factor 1, as well as the stem/loop located immediately 3′-ward. These two elements may have their joint effect by forcing the ribosome to pause at the UAG without binding a release factor (1). In our experiments, we dictate a ribosome pause at the hungry AUA codon by limiting the charging of cognate isoleucyl-tRNA. A ribosome pause dictated by limiting the availability of a specific tRNA isoacceptor stimulates bypassing as well (8), presumably by the same mechanism. We have elsewhere shown that bypassing can be stimulated not only at a hungry AUA codon, but also at other hungry codons, including AUC (unpublished experiments), AAG (ref. 7 and unpublished experiments), and AGA (8). It remains to be discovered precisely how a paused peptidyl-tRNA::ribosome with an empty A-site becomes prone to bypassing or frame-shifting.

The present results also address a suggestion made by Danchin and colleagues (9). They found some association between the tetranucleotide AGCT and sites of translational initiation, frameshifting, or potential “hopping” (i.e., bypassing) in the genomes of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. They accordingly suggested that this tetranucleotide may represent a frame-keeping signal. Most of our constructs have an AGCT (for historical reasons) in the coding gap region 2 nt upstream of the landing site. However, when we changed the first 3 nt of this quadruplet in two different 16-nt bypass reporters, there was no significant effect on bypassing efficiency. In our previous report, there was also no difference in bypassing efficiency between two 22-nt bypass reporters (L-22 and L-22′), which also differed in regard to the AGCT tetranucleotide. These comparisons all imply that an AGCT near upstream of the landing site plays no role in successful bypassing and is therefore unlikely to be a general framekeeping motif.

Some years earlier, Trifonov (18) observed a moderate bias in coding sequences toward the periodical pattern G-nonG-N and suggested that this periodicity might function as a framekeeping or frame-monitoring code. However, Curran and Gross's direct experimental test of the conjecture with frameshift reporters showed that reading frame maintenance was independent of G-nonG-N periodicity (19). This experience, like our negative results on AGCT, argues against simple, embedded framekeeping periodicities. But the phenomenon of bypassing, itself, as well as related information on frameshifting, implies that the maintenance of the reading frame depends on a different kind of information.

Both our results and those on the T4 gene 60 case (1) agree that the scanning complex resumes protein chain elongation efficiently only after a proper landing site, i.e., only after a triplet complementary to the anticodon of the wandering peptidyl-tRNA. Given our evidence that the peptidyl-tRNA::ribosome complex does pass through the coding gap, this specificity pointedly raises the question: why does the bypassing ribosome not resume protein chain elongation at other triplets along the way to its landing site? The simplest explanation is that the “A-site” binds ternary complex well only when peptidyl-tRNA in the adjacent “P-site” is juxtaposed to a fully complementary triplet. An interaction of this sort has been suggested before, on the basis of relatively small effects observed in vitro (20, 21). It seems to us that the high selectivity of bypassing ribosomes for a landing site synonymous with the takeoff site leads to a similar conclusion, and on much stronger grounds. [This conclusion is to be distinguished from the “three-site allosteric model,” which postulates that the accuracy of aminoacyl-tRNA selection at the A-site is conformationally coupled to the E-site's occupancy by deacylated tRNA (22, 23). Indeed, one wonders how the E-site would be defined for a bypassing ribosome::peptidyl-tRNA complex traveling many nucleotides downstream of the messenger triplet located at what is normally described as the E-site.]

This implied relationship between P-site pairing and A-site function might be another facet of the discovery by Farabaugh, Björk, and colleagues (24-28) that aberrant pairing in the P-site underlies frameshifting in a number of cases. Such aberrant pairing would be experienced by the bypassing peptidyl-tRNA from the time it disengages from the takeoff codon until it pairs with a cognate landing codon. Conversely, programmed frame-shifting is virtually limited to unusual sequences at which the peptidyl-tRNA retains cognate pairing with the new, shifted triplet in the mRNA sequence (24, 28). In the same vein, starvation-inducible frameshifting is most efficient at unusual sites that have the same characteristic (11, 24, 29). However, at most sequences, a slip of the peptidyl-tRNA in either direction would lead to improper pairing in the P-site and therefore, by our hypothesis, diminished affinity for aminoacyl-tRNA in the adjacent A-site. This relationship between P-site pairing and A-site availability itself is a framekeeping mechanism: the specificity of bypassing suggests that codon::anticodon pairing after translocation controls the ribosome's ability to continue translating, so as to avert reading frame errors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant RO1 GM 13626 from the National Institutes of Health.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviation: ILHX, isoleucine-hydroxamate.

References

- 1.Herr, A. J., Atkins, J. F., Gesteland, R. F. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 343-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang, W. M., Ao, S. Z., Casjens, S., Orlandi, R., Zeikus, R., Weiss, R., Winge, D. & Fang, M. (1988) Science 239, 1005-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss, R. B., Huang, W. M. & Dunn, D. M. (1990) Cell 62, 117-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herr, A. J., Wills, N. M., Nelson, C. C., Gesteland, R. F. & Atkins, J. F. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 311, 445-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herr, A. J., Nelson, C. C., Wills, N. M., Gesteland, R. F. & Atkins, J. F. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 309, 1029-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herr, A. J., Gesteland, R. F. & Atkins, J. F. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 2671-2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallant, J. A. & Lindsley, D. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13771-13776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindsley, D. L., Gallant, J. & Guarneros, G. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 48, 1267-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henaut, A., Lisacek, F., Nitschke, P., Moszer, I. & Danchin, A. (1998) Electrophoresis 19, 515-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton, W. A., Beckwith, J. R., Zipser, D. & Brenner, S. (1965) J. Mol. Biol. 14, 290-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barak, Z., Lindsley, D. & Gallant, J. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 256, 676-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathews, D. H., Sabina, J., Zuker, M. & Turner, D. H. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 288, 911-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss, R. B., Dunn, D. M., Atkins, J. F. & Gesteland, R. F. (1987) Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 52, 687-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menninger, J. R. (1978) J. Biol. Chem. 253, 6808-6813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keiler, K. C., Waller, P. R. & Sauer, R. T. (1996) Science 271, 990-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roche, E. D. & Sauer, R. T. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4579-4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muto, A., Ushida, C. & Himeno, H. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 25-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trifonov, E. N. (1987) J. Mol. Biol. 194, 643-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran, J. F & Gross, B. L. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 235, 389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergemann, K., Nierhaus, K. H. (1984) Biochem. Int. 8, 121-126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato, M., Nishikawa, K., Uritani, M., Miyazaik, M. & Takemura, S. (1990) J. Biochem. 107, 242-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nierhaus, K. (1990) Biochemistry 29, 4997-5008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nierhaus, K. H. (1993) Mol. Microbiol. 9, 661-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farabaugh, P. J. (1997) Programmed Alternative Reading of the Genetic Code (R. G. Landes, Austin, TX).

- 25.Quian, Q., Li, J. N., Zhao, H., Hagervall, T. G., Farabaugh, P. J. & Björk, G. R. (1998) Mol. Cell 1, 471-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farabaugh, P. J. & Björk, G. R. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 1427-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundararajan, A., Michaud, W. A., Qian, Q., Stahl, G. & Farabaugh, P. J. (1999) Mol. Cell 4, 1005-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farabaugh, P. J. (2000) Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 64, 131-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolor, K., Lindsley, D. & Gallant, J. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 230, 1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]