Abstract

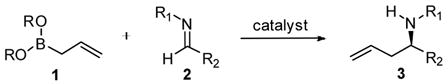

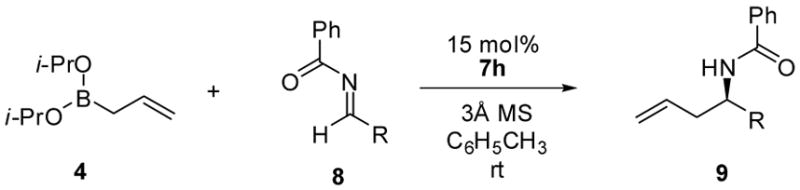

Chiral BINOL-derived diols catalyze the enantioselective asymmetric allylboration of acyl imines. The reaction requires 15 mol% of (S)-3,3′-Ph2-BINOL as the catalyst and allyldiisopropoxyborane as the nucleophile. The reaction products are obtained in good yields (75 – 94%) and high enantiomeric ratios (95:5 – 99.5:0.5) for aromatic and aliphatic imines. High diastereoselectivities (dr > 98:2) and enantioselectivities (er > 98:2) are obtained in the reactions of acyl imines with crotyldiisopropoxyboranes. This asymmetric transformation is directly applied to the synthesis of maraviroc, the selective CCR5 antagonist with potent activity against HIV-1 infection. Mechanistic investigations of the allylboration reaction including IR, NMR, and mass spectrometry study indicate that acyclic boronates are activated by chiral diols via exchange of one of the boronate alkoxy groups with activation of the acyl imine via hydrogen bonding.

Introduction

Chiral homoallylic amines are valuable building blocks for use in synthesis.1 They have found use as precursors for β-amino acids2 and heterocycles.3 Chiral homoallylic amines have also served as key intermediates in complex natural product synthesis and pharmacologically relevant compounds. 4 In addition, the structural motif is also present in a variety of bioactive molecules with wide-ranging biological properties.5

The asymmetric allylation of imines provides direct access to chiral homoallylic amines.6 Significant progress has been made in the development of practical approaches to these building blocks using chiral allylmetal reagents such as allyl silanes, 7 allyl boronates,8 and boranes,9 as well as diastereoselective allylmetal additions to chiral imines. 10 Innovative catalytic approaches include the development of chiral main group Cu- 11 and Zn-promoted12 reactions as well as Pd-13 and Zr-mediated14 allylmetal

|

(1) |

additions to imines and, more recently, allyindium reagents generated in the presence of BINOL-derived15 and chiral thiourea catalysts 16 which result in enantioselective additions to hydrazones. Despite these creative efforts, the catalytic asymmetric allylation of imines remains a considerable challenge; enantioselective additions to aliphatic imines and diastereoselective additions using substituted allylmetal reagents remain notably difficult using current methods. In an effort to develop a practical approach towards this structural class, we have expanded the scope of the asymmetric allylboration of C=X bonds17 catalyzed by chiral diols to include imines (eq 1). Herein we report the enantioselective allylboration of acyl aldimines promoted by BINOL-derived catalysts.

Results and Discussion

Asymmetric Allylboration of Acyl Imines

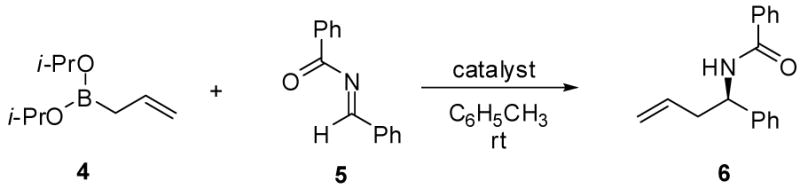

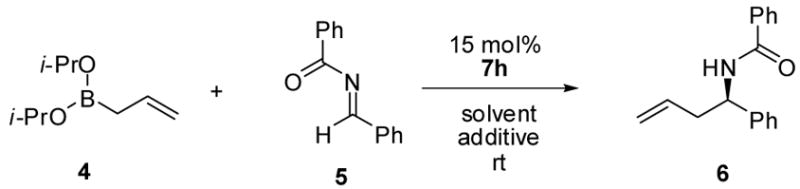

We initiated our investigation by evaluating the reaction of allyldiisopropoxyborane 4 with a variety of N-benzylidene derivatives, including benzamide 5, N-benzylidene benzamine, N-benzylidene-4-methoxyaniline, N-benzylidene-p-toluenesulfon-amide and N-benzylidene-P,P-diphenylphosphinic amide, in toluene at room temperature and 20 mol% (S)-BINOL 7e as catalyst. Benzamide 5 displayed the best reactivity and selectivity, and afforded the desired product in 80% yield and in an enantiomeric ratio (er) of 70:30. Other imines generally afforded the corresponding products in lower yield and er.

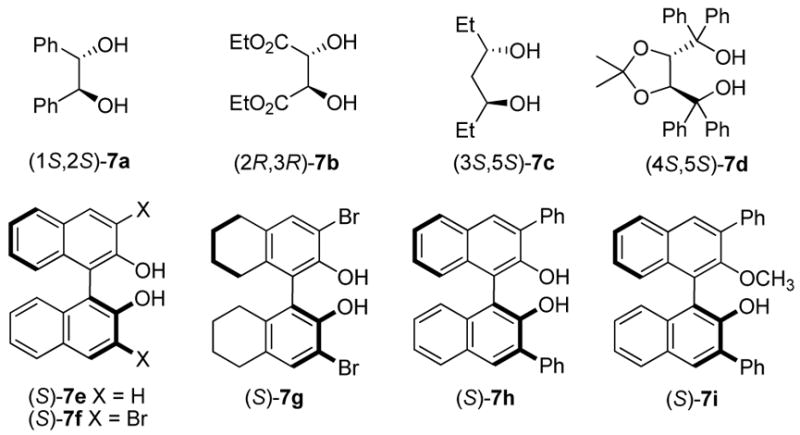

The allylboration reaction of imine 5 was investigated in the absence and presence of chiral diol catalysts. The reaction performed in the absence of diol afforded the homoallylic amide 6 in ≤ 5% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Chiral diols such as (S,S)-1,2-diphenylethane diol 7a, (+)-diethyl tartrate 7b and (S,S)-3,5-heptanediol 7c gave only negligible increases in yield over the uncatalyzed reaction (entries 2 – 4). However, the use of 15 mol% (+)-TADDOL 7d in the reaction resulted in higher yield (entry 5, 51% yield) but in racemic form. Alternatively, 15 mol% (S)-BINOL afforded 6a in 68:32 er and 76% isolated yield. The use of BINOL-derived catalysts bearing substitution at the 3,3′-positions, 7f – 7h, yielded the product in higher enantioselectivities (entries 7 – 9) with (S)-3,3′-Ph2-BINOL 7h affording the highest er (96:4) and yield. Reducing the catalyst loading resulted in diminished enantioselectivity (entries 10 & 11). Use of the BINOL-derived methyl ether 7i as the catalyst in the allylation reaction afforded the homoallylic amide in significantly lower yield and er, highlighting the importance of the diol functionality of the catalyst.

Table 1.

Asymmetric Allylboration of Acyl Iminesa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst | mol%b | % yieldc | erd |

| 1 | - | - | <5 | - |

| 2 | 7a | 15 | <5 | 50:50 |

| 3 | 7b | 15 | <5 | 55:45 |

| 4 | 7c | 15 | 10 | 60:40 |

| 5 | 7d | 15 | 51 | 50:50 |

| 6 | 7e | 15 | 76 | 68:32 |

| 7 | 7f | 15 | 81 | 93:7 |

| 8 | 7g | 10 | 60 | 96.5:3.5 |

| 9 | 7h | 15 | 85 | 96:4 |

| 10 | 7h | 10 | 80 | 95:5 |

| 11 | 7h | 5 | 60 | 90:10 |

| 12 | 7i | 15 | 21 | 55:45 |

Reactions were run with 0.125 mmol borane, 0.125 mmol acyl imine, 15 mol % catalyst and in toluene (0.1 M) for 16 h under Ar, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Catalyst concentration used relative to imine.

Isolated yield.

Enantiomeric ratios determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

During the course of our studies to optimize the reaction conditions, a significant solvent effect was observed. Electron donating solvents resulted in slower reaction rates and lower enantioselectivities. One reason for this may be due to the interruption of hydrogen bonding or ligand exchange between boronate 4 and diol 7h in Lewis basic solvents (Table 2, entries 1 & 2). Polar non-coordinating solvents gave faster rates and higher selectivities (entries 3 & 4). However, the key observation was the addition of 3Å molecular sieves. Their inclusion in the reaction was found to prevent decomposition of the hydrolytically unstable acyl imine from trace amounts of water (entry 6). While the size of molecular sieves increased, the beneficial effect diminished (entries 7 & 8).

Table 2.

Asymmetric Allylboration of Acyl Iminesa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | solvent | additive | % yieldb | erc |

| 1 | THF | - | 32 | 58:42 |

| 2 | Et2O | - | 28 | 60:20 |

| 3 | CH2Cl2 | - | 75 | 92:8 |

| 4 | C6H5CH3: C6H5CF3 3:1 | - | 77 | 92:8 |

| 5 | C6H5CH3 | - | 81 | 93:7 |

| 6 | C6H5CH3 | 3Å MS | 87 | 99:1 |

| 7 | C6H5CH3 | 4Å MS | 85 | 97:3 |

| 8 | C6H5CH3 | 5Å MS | 83 | 90:10 |

Reactions were run with 0.125 mmol borane, 0.125 mmol acyl imine, 15 mol % catalyst and in toluene (0.1 M) for 16 h under Ar, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Isolated yield.

Enantiomeric ratios determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

We next evaluated other types of imines in order to further explore the scope and limitations of the asymmetric allylboration. The reaction of methyl benzylidine carbamate 10a yielded only 13% desired product in 57:43 er (Table 4, entry 1). The carbamoyl imine decomposed via alcoholysis during the course of the reaction. Yields improved with larger carbamates but did not achieve significantly better levels of enantioselectivity (entries 2 & 3). We also investigated how the electronic character of the benzoyl group influenced the reaction. Substitution at the para-position with electron-donating groups resulted in slower reaction rates than electron-withdrawing subsitution but in all cases the enantioselectivities were high (entries 5 – 9). Substitution at the ortho-position resulted in significant erosion of the er (entry 10). The cinnamoyl imine and cyclohexyl carboxamide imine were also found to be good substrates in the allylboration reaction under optimized condition. The substrate generality of the asymmetric reaction led us to explore the synthetic utility of this methodology.

Table 4.

Asymmetric Allylboration of Benzoyl Iminesa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | product | % yieldb | erc |

| 1 | CH3O | 11a | 13 | 57:43 |

| 2 | t-BuO | 11b | 25 | 65:35 |

| 3 | CH2=CHCH2O | 11c | 41 | 65:35 |

| 4 | CH3 | 11d | 52 | 70:30 |

| 5 | p-(CH3)2N-C6H4 | 11e | 76 | 97:3 |

| 6 | p-CH3O-C6H4 | 11f | 80 | 97.5:2.5 |

| 7 | p-Br-C6H4 | 11g | 83 | 96.5:3.5 |

| 8 | p-F-C6H4 | 11h | 84 | 97.5:2.5 |

| 9 | p-NO2-C6H4 | 11i | 92 | 99.5:0.5 |

| 10 | o-F-C6H4 | 11j | 83 | 69:31 |

| 11 | (E)-PhCH=CH | 11k | 82 | 95:5 |

| 12 | c-C6H11 | 11l | 83 | 97:3 |

Reactions were run with 0.125 mmol borane, 0.125 mmol acyl imine, 15 mol % catalyst and 3Å molecular sieves in toluene (0.1 M) for 24 h under Ar, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Isolated yield.

Enantiomeric ratios determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

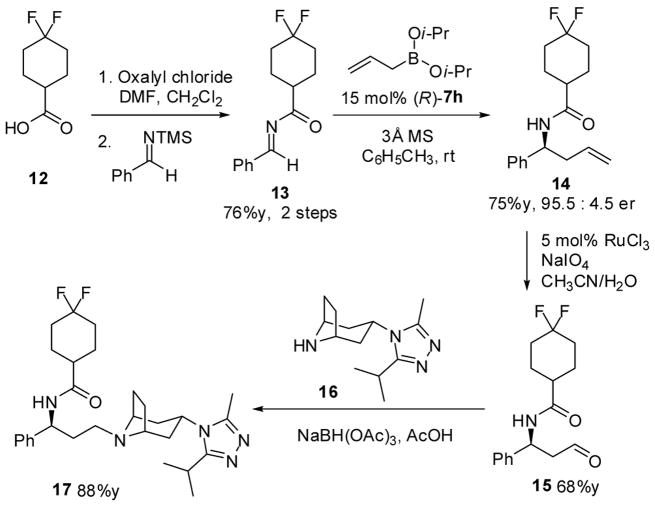

Synthesis of Maraviroc

Traditional HIV chemotherapy has relied heavily on the disruption of viral replication.18 Targeting protease inhibitors and reverse transcriptase inhibitors have increased the lifetime of HIV-infected patients; however, this heavy reliance on the targeting of viral machinery has increased resistance to these drugs.19 Recently, a new CCR5 entry inhibitor, Maraviroc, has been fast-tracked through clinical trials after showing high success rates.20 CCR5 entry inhibitors are a new compound class in HIV therapy that targets the human protein responsible for recognition of the virus.

A recent report describing the synthesis of maraviroc highlights the use of β-phenylalanine acid as the source of chirality for the synthesis. 21 Our approach toward the synthesis of maraviroc relied on the asymmetric allylation of difluorocyclohexane carboximide imine 13 (Scheme 1). Starting from the corresponding acid, the acyl chloride was accessed by treatment with oxalyl chloride and catalytic DMF. The crude acid chloride was mixed with freshly distilled silyl imine and then refluxed for 3h. Removal of the solvent and volatiles afforded the acyl amine as a viscous oil. Allylation of the imine under standard reaction conditions gave the homoallylic amide in good yield and selectivity (75% yield, 95.5:4.5 er). Oxidation of the olefin with RuCl3 and NaIO4 in a solution of acetonitrile and H2O (6:1) cleanly gave the aldehyde22 and reductive amination with the tropane yielded maraviroc. The route, while only a few steps shorter than the β-amino acid approach, limits the use of amine protecting group manipulation.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Maraviroc

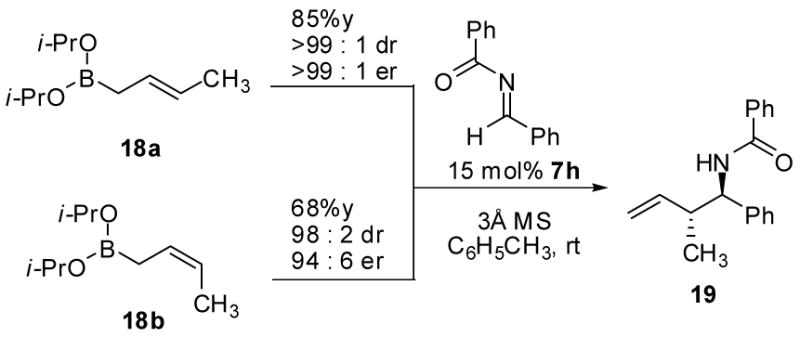

Crotylboration of Acyl Imine

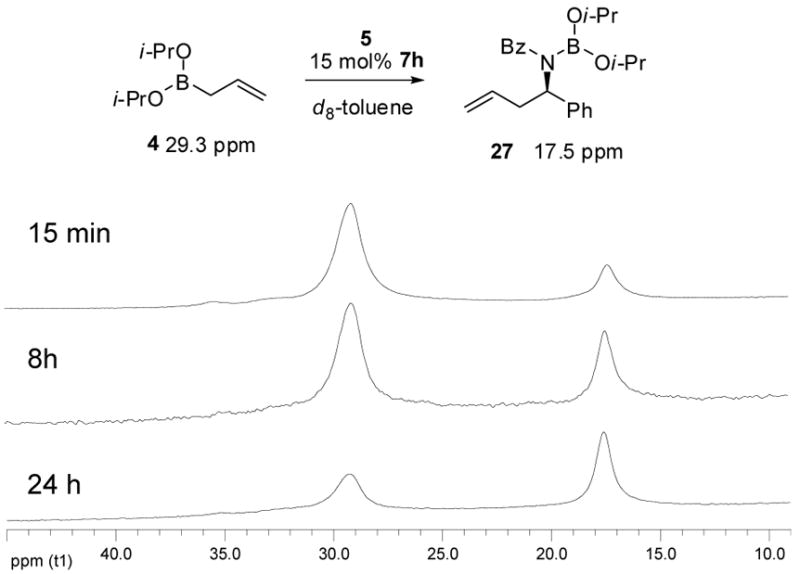

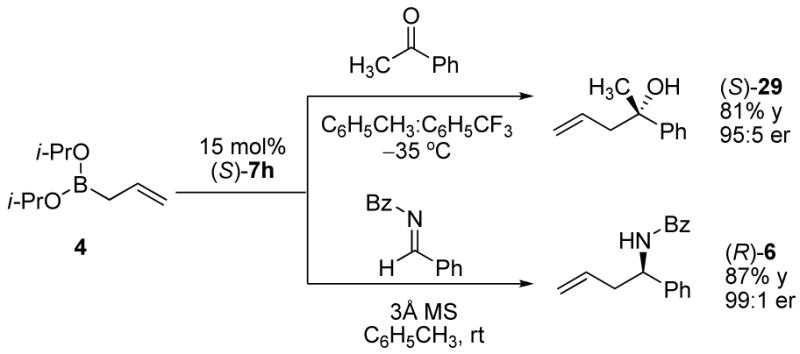

The asymmetric crotylboration of benzoyl imine 5 yielded an interesting result (Scheme 1). The use of (E)-crotylborane 18a in the reaction resulted in the formation of the anticipated anti-addition product 19 in high dr and er (99:1). However, using (Z)-crotylboronate 18b in the reaction also resulted in the formation of 19 in lower yields (68%) and er (94:6). To determine the relative configuration, the benzoyl group was removed via DIBAL-H reduction followed by acid hydrolysis to afford the known homoallylic amine in 82% yield (Scheme 3). Benzylidine 20 was observed as intermediate in this two step process. The spectroscopic data of amine 21 proved to be identical with previously reported data. 21,23

Scheme 3.

Removal of the N-Benzoyl Group

Mechanistic Studies

Recent studies involving the catalytic activation of allylboronates have described interesting modes by which the addition to π systems may be accomplished. Beyond the most studied types of Lewis acid activation of carbonyl groups,1c,24 Hall25 and Miyaura26 have used Lewis- and Brønsted acids to activate the boronate through Lewis acid coordination to the boronate oxygen,27 Shibasaki illustrated how allylboronates may be used as allyl donors for in situ formation of chiral Cu-allyl species,10d and Morken recently described the conjugate addition of allylboronates to benzylidene ketones catalyzed by Ni(0) and Pd(0) complexes.28 An alternative type of boron activation that we have used for the enantioselective addition of allylboronates to ketones17 and Chong has employed for the asymmetric conjugate addition of organoboronates to benzylidene ketones 29 is via exchange of the alkoxy boronate ligands to create a more activated allylboronate species. Our mechanistic studies focused on characterizing the boronate species under catalytic conditions, determining the role for the BINOL catalyst, and following the course of the reaction spectroscopically. Key aspects of the asymmetric allylboration reaction catalyzed by diols include the type of boronate used in the reaction, the diol functionality of the catalyst, and the type of imine used in the reaction. Consistent with our previous work, pinacol, ethylene glycol, and 1,3-propane diol derived allylboronates suffered from slow reaction rates, low yields and enantioselectivities, whereas, diisopropoxy boronate 4 afforded the best results. Similar to our previous studies, the diol functionality of the catalyst was crucial. The allylboration of imine 5 using monomethylated-BINOL catalyst 7i resulted in significantly lower yields and low er (Table 1, entry 12). Finally, the nature of the imine also proved to be important. Acyl imines were found to be important for rate and selectivity (Table 4). Carbamoyl derived imines were found to be less reactive and less selective. Benzyl and aryl imines were also not good substrates for the reaction affording the corresponding homoallylic amine in poor enantioselectivities and in low to moderate yields (< 3:2 er, < 40% yield). These observations highlight the important characteristics of the imine for achieving good yield and high enantioslectivity.

Boronate Ligand Exchange

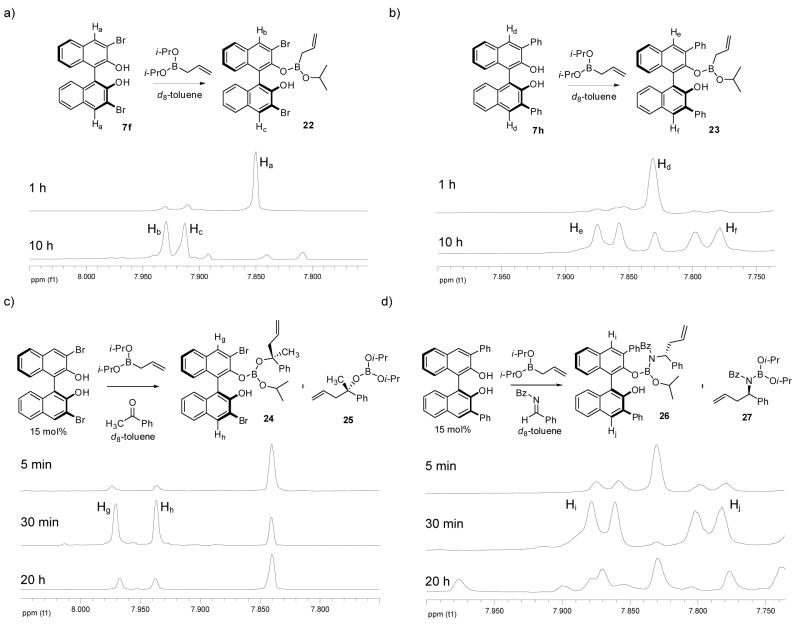

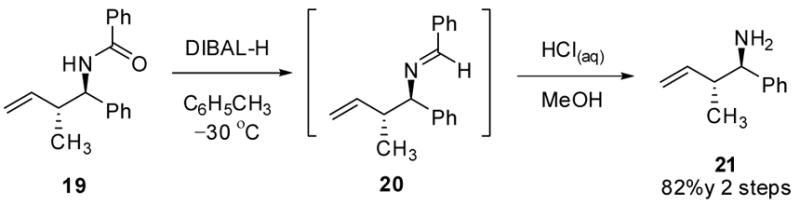

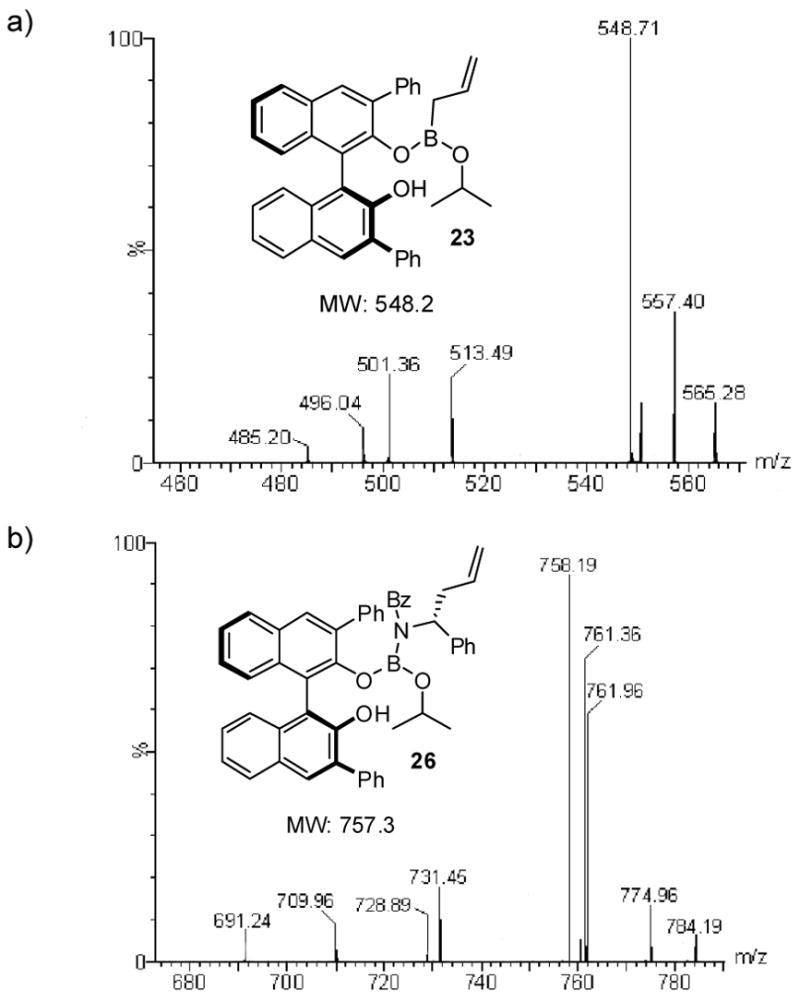

Our initial experiments focused on characterizing the boronate species under the catalytic reaction conditions. NMR and electron spray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) experiments were conducted at room temperature of BINOL-derived diols and boronates in the presence and absence of imines. In the reaction of 4 with (S)-3,3′-Br2-BINOL 7f (1:1) monitored by 1H NMR, Hb and Hc at 4 and 4′ positions of 7f after 10 hours indicated loss of C2 symmetry via exchange of one isopropoxy ligand on the boronate resulting in the formation of a dissymmetrical boronate complex 22 (Figure 2a), the active complex in the asymmetric allylboration of ketones.17 A similar observation is made in the reaction of 4 with 7h (Figure 2b). Resonances corresponding to He and Hf in boronate 23 result from coupling to the 3- and 3′-phenyl ring of the catalyst associated complex. Both exchange reactions indicate formation of a single isopropoxide exchange event.

Figure 2.

1H-NMR studies for the formation of BINOL-boronate complex: (a) 7f + allylboronate 4. (b) 7h + allylboronate 4. (c) 7f + allylboronate 4 + acetophenone. (d) 7h + allylboronate 4 + acyl imine 5.

The exchange reaction was also monitored by ESI mass spectrometry. ESI-MS is a relatively mild process that can lead to the qualitative analysis of fleeting structures.30 With this in mind we analyzed the mixture of BINOL 7h and boronate 4 that was allowed to equilibrate at rt for 4 hours into a MicroMass ZQ 2000 mass spectrometer in positive electrospray ionization mode. Under these conditions the mass of complex 22 was observed (Figure 3a) without any detectable formation of the corresponding cyclic boronate.

Figure 3.

ESI mass spectrometry study of boronate intermediates. (a) 7h + allylboronate 4 for 4 h. (b) 7h + allylboronate 4 + acyl imine 5.

Spectroscopic Characterization of the Reaction

We next set out to further characterize the course of the reaction and the role of the diol catalyst by spectroscopic methods. 1H NMR revealed the same exchange process in the asymmetric allylboration of acetophenone and acyl imine 5 (Figures 2c & 2d). Interestingly, the rate of ligand exchange was significantly enhanced in the presence of an electrophile with complex formation occurring within 30 min. In both the reaction of the ketone and the acyl imine, the predominant resting state of the diol appeared to be the product associated complexes 24 and 26. Further characterization of intermediate 26 during the course of the reaction was performed using 11B NMR (Figure 4). Disappearance of allyldiisopropoxy borane 4 at 29 ppm with concomitant appearance of product 27 at 17 ppm was observed. However, because of the resolution afforded by 11B NMR, it was difficult to observe other species that may be present at low concentrations such as intermediate 26. ESI-MS of the crude reaction mixture did reveal the presence of intermediate 26 (Figure 3b) as the predominant intermediate incorporating the diol catalyst.

Figure 4.

11B-NMR studies of asymmetric allylboration reaction. 7h + allylboronate 4 + acyl imine 5.

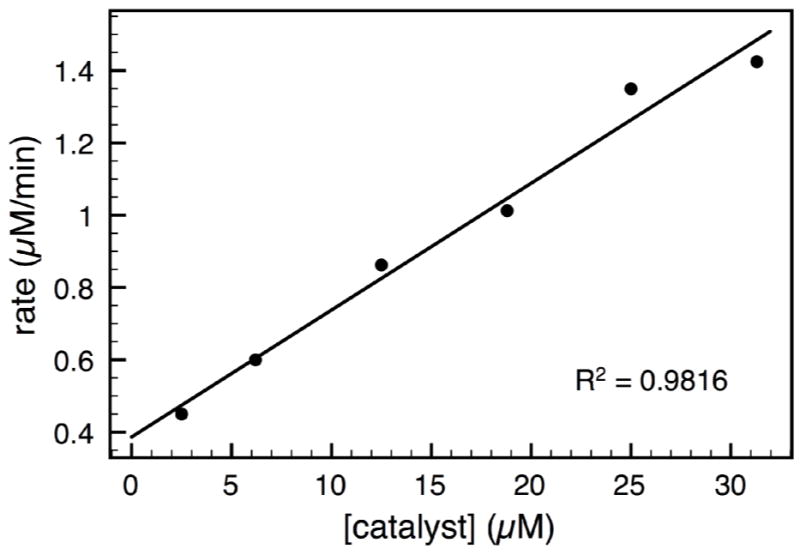

The dependence of catalyst 7h concentration on the initial rate of the reaction was determined by in situ IR monitoring. Using a Mettler Toledo-AutoChem ReactIR 4000, the appearance of product amide 6a at 1428 cm−1 was monitored during the course of the reaction over a > 10-fold range of catalyst concentrations (Figure 5). The linear dependence of observed rates on catalyst concentration is consistent with a model involving an active diol-associated complex 23. The similar dependence on catalyst was observed for the asymmetric allylboration of acetophenone.17

Figure 5.

Plot of the observed rate versus [catalyst 7h] in the reaction of boronate 4 with imine 5 at rt. The linear relationship indicates a first-order dependence.

Model for Selectivity

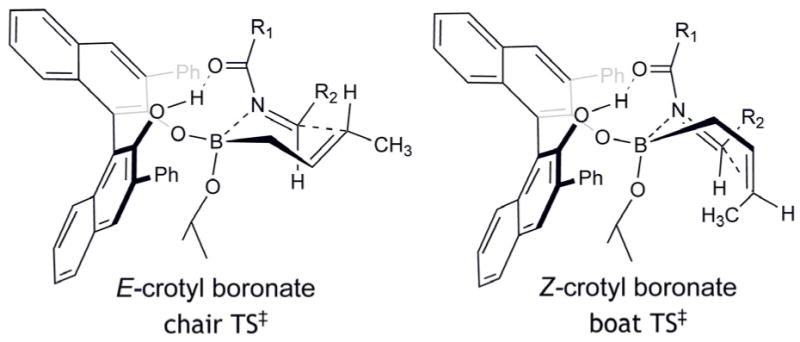

In the asymmetric allylboration of ketones, the (S)-homoallylic alcohol is the major enantiomer isolated from the reaction catalyzed by (S)-7h (Scheme 4). However, using the same catalyst in the allylboration of imine 5, the (R)-homoallylic amide 6 was isolated. We postulate that the switch in enantiofacial selectivity is due to an alternative mechanism for activation of the boronate involving a different conformation than that proposed for the asymmetric allylboration of ketones. Another intriguing aspect of the allylboration of imines is the addition of crotyl boronates (Scheme 2). Unlike the high levels of diastereocontrol exhibited by the crotylation of ketones, under similar conditions both E- and Z-crotyl boronates afforded the same diastereomer. The E-crotyl boronate afforded the product in high er and dr whereas the Z-crotyl boronate afforded the product in similarly high dr but lower er. The high degree of anti-selectivity afforded by the E-crotylboronate can be rationalized via a chair transition state (Figure 6).31 However, the anti-selectivity afforded by the Z-crotyl boronate must then arise from the corresponding boat transition state; a preferred conformer due to the pseudo-trans diaxial interaction of the methyl group of the Z-boronate and acyl substituent of the imine arising from the chair transition state. We propose that the enantiofacial selectivity is the result of catalyst coordination to the Z-conformer of the acyl imine. While the predominant form of the imine is the E-configuration, the more reactive Z-conformer has been proposed by Corey32 and others33 for reactions with imines due to steric interactions that arise from boronate reagent coordination. In our proposed model for selectivity, the hydrogen-bonding character of the diol-boronate complex facilitates coordination of the imine acyl functionality and could potentially be important for E/Z isomerization. Our proposed model illustrates coordination to the Z-imine by the boronate complex resulting in the observed re enantiofacial selectivity of the allylboration reaction.

Scheme 4.

Enantiofacial Selectivity in Asymmetric Allylboration of Ketones and Acyl Imines

Scheme 2.

Asymmetric Crotylboration of Benzoyl Imine

Figure 6.

Proposed Transition States

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a highly enantioselective allylboration of acyl imines catalyzed by chiral BINOL-derived catalysts. The reaction is highly selective for aryl as well as aliphatic acyl imines. The asymmetric synthesis of the anti HIV-1 compound maraviroc was accomplished using the asymmetric allylboration reaction. The reaction of crotyl boronates affords the corresponding anti product in high diastereoselectivity. Mechanistic studies strongly suggest facile exchange between the boronate and catalyst giving rise to the active allylation reagent. Ongoing studies include expansion of the scope and utility of the reaction.

Experimental Section

Procedure for Enantioselective Allylation of Acyl Imines Catalyzed by Diols

A 50 mL oven dried round bottom flask was charged with stir bar and flushed with Ar. To the flask was added N-benzylidenebenzamide 5 (104 mg, 0.5 mmol), 3Å molecular sieves (500 mg), and (S)-3,3′-Ph2-BINOL 7h (33 mg, 0.05 mol). The flask was fitted with a septum and placed under an atmosphere of Ar. To the flask was added toluene (3.0 mL) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature. Allyldiisopropoxyborane 4 in a toluene solution (500 μL, 0.50 mmol, 1 M solution) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 hours. The reaction was diluted with ether (10 mL) and water (10 mL). The biphasic mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 minutes. The organic layer was separated and dried over Na2SO4. The organic layer was isolated by filtration and the filtrate was concentrated in vacuo at 20 °C. The residue was purified by flash chromatography over silica gel (elution with 95:5 – 9:1, hexanes:EtOAc) to afford the homoallylic amide as a white solid (109 mg, 85% yield). The enantiomeric ratio of the product was determined to be 99:1 by chiral HPLC analysis. tR minor: 5.9 min, tR major: 9.1 min, [Chiralcel®OD column, 24cm × 4.6 mm I.D., hexanes:IPA 90:10, 1.5 mL/min].

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures and HPLC analysis for compounds 9a – 9p, 11e – 11l, 19 (PDF); complete reference 20(b). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Figure 1.

Chiral Diols.

Table 3.

Asymmetric Allylboration of Benzoyl Iminesa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | product | % yieldb | erc |

| 1 | Ph | 9a | 87 | 99:1 |

| 2 | p-CH3-C6H4 | 9b | 83 | 98:2 |

| 3 | p-Br-C6H4 | 9c | 86 | 97.5:2.5 |

| 4 | p-CH3O-C6H4 | 9d | 85 | 95:5 |

| 5d | p-F-C6H4 | 9e | 94 | 98:2 |

| 6d | o-F-C6H4 | 9f | 91 | 95.5:4.5 |

| 7d | m-CF3-C6H4 | 9g | 89 | 97.5:2.5 |

| 8 | 2-C4H3O | 9h | 83 | 96:4 |

| 9 | 2-C4H3S | 9i | 81 | 95:5 |

| 10 | 2-naphthyl | 9j | 88 | 96:4 |

| 11 | (E)-PhCH=CH | 9k | 82 | 95.5:4.5 |

| 12 | PhCH2CH2 | 9l | 83 | 99.5:0.5 |

| 13 | c-C6H11 | 9m | 80 | 98:2 |

| 14 | t-Bu | 9n | 81 | 99.5:0.5 |

| 15 | BnOCH2 | 9o | 84 | 96.5:3.5 |

| 16 | (Z)-EtCH=CH(CH2)2 | 9p | 82 | 95.5:4.5 |

Reactions were run with 0.5 mmol 4, 0.5 mmol imine, and 15 mol % catalyst and 3Å molecular sieves in toluene for 36 h under Ar, followed by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Isolated yield.

Determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Reactions were run at 10 °C for 48 h.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge CEM Corporation (Matthews, NC) for assistance with microwave instrumentation and Symyx, Inc. (Santa Clara, CA) for chemical reaction planning software support. SL gratefully acknowledges a graduate research fellowship from Merck Research Laboratories – Boston. This research was supported by a gift from Amgen, Inc., an NSF CAREER grant (CHE-0349206), and the NIH (P50 GM067041 and R01 GM078240)

References

- 1.Reviews: Denmark SE, Almstead NG. In: Modern Carbonyl Chemistry. Otera J, editor. Wiley-VHC; Weinheim: 2000. Chapter 10.Puentes CO, Kouznetsov V. J Heterocycl Chem. 2002;39:595–614.Ding H, Friestad GK. Synthesis. 2005:2815–2829.

- 2.(a) Laschat S, Kunz H. J Org Chem. 1991;56:5883–5889. [Google Scholar]; (b) Robl JA, Cimarusti MP, Simpkins LM, Brown B, Ryono DE, Bird JE, Asaad MM, Schaeffer TR, Trippodo NC. J Med Chem. 1996;39:494–502. doi: 10.1021/jm950677a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Felpin FX, Girard S, Vo-Thanh G, Robins RJ, Villieras J, Lebreton J. J Org Chem. 2001;66:6305–6312. doi: 10.1021/jo010386b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee CLK, Lui HY, Loh TP. J Org Chem. 2004;69:7787–7789. doi: 10.1021/jo048903o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Goodman M, Del Valle JR. J Org Chem. 2004;69:8946–8945. doi: 10.1021/jo0485738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Kim G, Chu-Moyer MY, Danishefsky SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:2003–2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Mitchell HJ, van Delft FL, Rubsam F, Rodriguez RM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:1871. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wright DL, Schulte JP, II, Page MA. Org Lett. 2000;2:1847–1850. doi: 10.1021/ol005903b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xie W, Zou B, Pei D, Ma D. Org Lett. 2005:2775–2777. doi: 10.1021/ol050991r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) White JD, Hansen JD. J Org Lett. 2005;70:1963–1977. doi: 10.1021/jo0486387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Lloyd HA, Horning EC. J Org Chem. 1960;25:1959–1962. [Google Scholar]; (b) Doherty AM, Sircar I, Kornberg BE, Quin J, III, Winters RT, Kaltenbronn JS, Taylor MD, Batley BL, Rapundalo SR, Ryan MJ, Painchaud CA. J Med Chem. 1992;35:2–14. doi: 10.1021/jm00079a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schmidt U, Schmidt J. Synthesis. 1994:300–304. [Google Scholar]; (d) Barrow RA, Moore RE, Li LH, Tius MA. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:3339–3351. [Google Scholar]; (e) Janjic JM, Mu Y, Kendall C, Stephenson CRJ, Balachandran R, Raccor BS, Lu Y, Zhu G, Xie W, Wipf P, Day BW. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Suvire FD, Sortino M, Kouznetsov VV, Vargas MLY, Zacchino SA, Cruz UM, Enriz RD. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:1851–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reviews: Kleinman EF, Volkmann RA. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 2. Pergamon; New York: 1991. 975 pp.Yamamoto Y, Asao N. Chem Rev. 1993;93:2207–2293.Enders D, Reinhold U. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1997;8:1895–1946.Bloch R. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1407–1438. doi: 10.1021/cr940474e.Alvaro G, Savoia D. Synlett. 2002:651–673.Friestad GK, Mathies AK. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:2541–2569. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.06.117.

- 7.(a) Panek JS, Jain NF. J Org Chem. 1994;59:2674–2675. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schaus JV, Jain NF, Panek JS. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:10263–10274. [Google Scholar]; (c) Berger R, Rabbat P, Leighton J. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9596–9597. doi: 10.1021/ja035001g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Berger R, Duff K, Leighton J. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5686–5687. doi: 10.1021/ja0486418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Chataigner I, Zammattio F, Lebreton J, Villiéras J. Synlett. 1998:275–276. [Google Scholar]; (b) Watanabe K, Kuroda S, Yokoi A, Ito K, Itsuno S. J Organomet Chem. 1999;581:103–107. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sugiura M, Hirano K, Kobayashi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7182–7183. doi: 10.1021/ja049689o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wu TR, Chong JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9646–9647. doi: 10.1021/ja0636791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Ramachandran PV, Burghardt TE. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:4387–4395. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Canales E, Hernandez E, Sodequist JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8712–8713. doi: 10.1021/ja062242q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Cook GR, Maity BC, Karbo R. Org Lett. 2004;6:1741–1743. doi: 10.1021/ol0496172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miyabe H, Yamaoka Y, Naito T, Takemoto Y. J Org Chem. 2004;69:1415–1418. doi: 10.1021/jo035442i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Vilaivan T, Winotapan C, Banphavichit V, Shinada T, Ohfune Y. J Org Chem. 2005;70:3464–3471. doi: 10.1021/jo0477244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Friestad GK, Korapala CS, Ding H. J Org Chem. 2006;71:281–289. doi: 10.1021/jo052037d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Fang X, Johannsen M, Yao S, Gathergood N, Hazell RG, Jorgensen KA. J Org Chem. 1999;64:4844–4849. doi: 10.1021/jo990238+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ferraris D, Young B, Cox C, Dudding T, Drury WJ, III, Ryzhkov L, Taggi AE, Lectka T. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:67–77. doi: 10.1021/ja016838j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kiyohara H, Nakamura Y, Matsubara R, Kobayashi S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:1615–1617. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wada R, Shibuguchi T, Makino S, Oisaki K, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7687–7691. doi: 10.1021/ja061510h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamada T, Manabe K, Kobayashi S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:3927–3930. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Nakamura H, Nakamura K, Yamamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4242–4243. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fernandes RA, Stimac A, Yamamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14133–14139. doi: 10.1021/ja037272x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yamamoto Y, Fernandes R. J Org Chem. 2004;69:735–738. doi: 10.1021/jo035453b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gastner T, Ishitani H, Akiyama R, Kobayashi S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:1896–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Cook GR, Kargbo R, Maity B. Org Lett. 2005;7:2767–2770. doi: 10.1021/ol051160o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kargbo R, Takahashi Y, Bhor S, Cook GR, Lloyd-Jones GC, Shepperson IR. J Am Chem Soc. 2007:3846–3847. doi: 10.1021/ja070742t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan KL, Jacobsen EN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:1315–1317. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lou S, Moquist PN, Schaus SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12660–12661. doi: 10.1021/ja0651308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richman DD. Nature. 2001;410:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/35073673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Fumero E, Podzamczer D. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:1077–1084. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ickovics JR, Meade CS. AIDS Care. 2002;14:309–318. doi: 10.1080/09540120220123685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Wood A, Armour D. Prog Med Chem. 2005;43:239–271. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6468(05)43007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dorrr P, et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4721–4732. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4721-4732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Price D, Gayton S, Selby MD, Ahman J, Haycock-Lewandowski S, Stammen BL, Warren A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:5005–5007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plietker B. Synthesis. 2005;15:2453–2472. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang D, Zhang C. J Org Chem. 2001;66:4814–4818. doi: 10.1021/jo010122p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramachandran PV, Burghardt TE, Bland-Berry L. J Org Chem. 2005;70:7918. doi: 10.1021/jo0508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Denmark SE, Weber EJ. Helv Chim Acta. 1983;66:1655–1660. [Google Scholar]; (b) Keck GE, Savin KA, Cressman ENK, Abbott DE. J Org Chem. 1994;59:7889–7896. [Google Scholar]; (c) Thomas EJ. Chem Commun. 1997:411–418. [Google Scholar]; (d) Marshal JA, Gill K, Seletsky BM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:953–956. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000303)39:5<953::aid-anie953>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Kennedy JWJ, Hall DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11586–11587. doi: 10.1021/ja027453j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rauniyar V, Hall DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4518–4519. doi: 10.1021/ja049446w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yu SH, Ferguson MJ, McDonald R, Hall DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12808–12809. doi: 10.1021/ja054171l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rauniyar V, Hall DG. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:2426–2428. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyaura N, Ahiko T, Ishiyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12414–12415. doi: 10.1021/ja0210345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rauniyar V, Hall DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4518–4519. doi: 10.1021/ja049446w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sieber JD, Liu S, Morken JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2214–2215. doi: 10.1021/ja067878w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Wu TR, Chong JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3244–3245. doi: 10.1021/ja043001q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu TR, Chong JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4908–4909. doi: 10.1021/ja0713734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Cole RB. Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Wiley; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]; (b) Henderson W, Nicholson BK, McCaffrey LJ. Polyhedron. 1998;17:4291–4313. [Google Scholar]; (c) Colton R, Agostino AD, Traeger JC. Mass Spectrom Rev. 1995;14:79–106. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cech NB, Enke CG. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2001;20:362–387. doi: 10.1002/mas.10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto Y, Komatsu T, Maruyama K. J Org Chem. 1985;50:3115–3121. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corey EJ, Decicco CP, Newbold RC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:5287–5290. [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Roush WR. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, editors. Vol. 2. Pergamon; New York: 1991. p. 1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Alvaro G, Boga C, Savoia D, Umano-Ronchi A. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1;1996:875–882. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures and HPLC analysis for compounds 9a – 9p, 11e – 11l, 19 (PDF); complete reference 20(b). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.