Abstract

Using 323 matched parties of birth mothers and adoptive parents, this study examined the association between the degree of adoption openness (e.g., contact and knowledge between parties) and birth and adoptive parents’ post-adoption adjustment shortly after the adoption placement (6 to 9 months). Data from birth fathers (N=112), an understudied sample, also were explored. Openness was assessed by multiple informants. Results indicated that openness was significantly related to satisfaction with adoption process among adoptive parents and birth mothers. Increased openness was positively associated with birth mothers’ post-placement adjustment as indexed by birth mothers’ self reports and the interviewers’ impression of birth mothers’ adjustment. Birth fathers’ report of openness was associated with their greater satisfaction with the adoption process and better post-adoption adjustment.

Keywords: openness, adoption, adjustment, birth parent, adoptive parent

For much of the 20th century, societal expectations of ‘parenting’ consisted of rearing one’s own biological child. Advanced fertility donor methods to assist in reproductive success were yet to be developed, and adoptions were generally closed or “confidential” in nature and characterized by secrecy. These more secretive and closed adoption practices were conceived to protect all three parties of the adoption triad – birth parents, adoptive parents, and the child (Bussiere, 1998; Silverstein & Demick, 1994). Confidential adoptions were thought to ensure birth parents’ rights of privacy, shielding unwed mothers from the stigma of “illegitimacy”. These practices also were believed to protect adopted children from social ridicule and to shelter adoptive parents from the humiliation of their infertility (Bussiere, 1998). Since the 1970s, however, there has been a gradual shift in societal practices and views around ‘parenting’, with fertility donor methods becoming developed, and open adoptions becoming the norm (Grotevant, McRoy, Elde, & Fravel, 1994). In contrast to closed adoption, open adoption is characterized by contact and communication between birth and adoptive parents (Grotevant & McRoy, 1998). As stigma surrounding non-marital births diminished and unwed parenthood became increasingly accepted, it is now quite common for birth and adoptive families to have some degree of post-placement contact with one another. The degree of openness, however, varies widely, ranging from the exchange of a few photos mediated through an adoption agency to frequent visits and information exchanges (Grotevant & McRoy, 1998).

The implications of varying degrees of openness in adoption to the post-placement adjustment of birth and adoptive parents remain a subject of much debate (Miall & March, 2005). Opponents of open adoption maintain that continued contact between the adopted child and birth parents impedes the attachment and bonding between adoptive parents and their adopted child. According to their view, adoptive parents in open adoption feel less in control and less secure in their parental role with a lingering presence of the birth parents (Kraft, Palombo, Woods, Mitchell, & Schmidt, 1985). Open adoption also was assumed to interfere with the grieving process that is essential for the mental health of the birth mother by not allowing her to experience a finality of the separation and a full mourning experience to eventually gain perspective (Kraft et al., 1985).

Proponents of open adoption see things quite differently. They suggest that adoptive parents in open adoption benefit significantly from information about birth parents through ongoing contact with them. Openness in adoption also allows adoptive parents to gain knowledge about their child’s medical and mental health histories, ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and reasons for adoption (Campbell, Silverman, & Patti, 1991; Siegel, 2003). Open adoption, therefore, makes adoptive parents feel more, rather than less, secure in their parental role because adoptive parents feel that birth parents have given them explicit consent to parent the child (Siegel, 2003). Open adoption also helps to mitigate birth mothers’ feelings of pain and loss, resulting in less destructive behavior and greater emotional well-being (Baran, Pannor, & Sorosky, 1976; Groth, Bonnardel, Davis, Martin, & Vousden, 1987). Moreover, birth mothers who are involved in open adoption are more likely to feel assured of the child’s welfare because the direct contact they have with the adoptive parents typically fosters trust that their child is in a safe and caring home (Pannor & Baran, 1984). In contrast, closed adoptions are viewed as confining; birth mothers often feel isolated, have unresolved feeling of guilt and self-blame, and feel uncertain of the well-being of the child (DeSimone, 1996; Logan, 1996; Silverman, Campbell, Patti, & Style, 1988; Silverstein & Demick, 1994). Thus, greater certainty of the child’s well-being may not only alleviate the birth mother’s grief, but also may contribute to her sense of pride regarding the decision (Lancette & McClure, 1992).

Open adoption also can be viewed as a form of what Granovetter (1973) called “weak ties” whereby adoptive and birth parents are connected through special interpersonal relationships that arise out of special circumstances of adoption. Establishing supportive relationships outside of birth parents’ immediate social networks in the form of continued exchanges and contact may be especially important for their post–placement adjustment. Birth parents, particularly birth mothers, are often socially isolated after placement (DeSimone, 1996; Logan, 1996; Silverman et al., 1988; Silverstein & Demick, 1994). Although some limited evidence suggests that birth fathers found adoptions processes challenging (e.g., Baumann, 1999; Clapton, 2002; Deykin, Patti, & Ryan, 1988; Reitz & Watson, 1992), birth fathers also may benefit from having “weak ties” to the adoptive families. Such “weak ties” may provide birth parents’ assurance and certainty about their adopted child. Open adoption, therefore, forges a new form of relationship in which birth and adoptive parents have a “shared fate” to the benefit of the parties involved (Kirk, 1964).

The Existing Empirical Evidence

Although researchers have begun to examine empirically the benefits and consequences of open adoption (e.g., Berry, 1993; Berry, Dylla, Barth, & Needell, 1998; Grotevant et al., 1994; Von Korff, Grotevant, & McRoy, 2006), data remain scarce and the existing research has often yielded inconsistent results. For example, Blanton and Deschner (1990) reported that birth mothers using open adoption felt more socially isolated, had more somatic complaints, felt more despair, and expressed more dependency than birth mothers involved in confidential adoption. In contrast, more recent work suggests that open adoption may reduce stress for all involved parties (Grotevant & McRoy, 1998), particularly birth mothers (DeSimone, 1996; Logan, 1996; Silverstein & Demick, 1994). In Siegel’s (2003) study of adoptive parents who were interviewed seven years after the initial placement of the adopted child, although adoptive parents were more likely to report that the adopted child was “better off” with ongoing contact with the birth parents, some adoptive parents felt more pressure as a parent in an open adoption than they suspected they would in a closed adoption. Most of the empirical work, particularly those supporting the position of closed adoption, has used small samples or been more qualitative in nature. Although more recent work has begun to document the benefits of contacts between adoptive and birth families (Berry, 1993; Grotevant & McRoy, 1998), the issue of the costs and benefits associated with open and closed adoption remains to be determined.

The most systematic studies of openness come from recent survey data collected from two different sources, from California (Berry, 1993; Berry et al., 1998) and from the Minnesota-Texas Adoption Project (MTAP: Grotevant & McRoy, 1998; Grotevant et al., 1994; McRoy, Grotevant, & White, 1988). Based on a survey of 1,396 adoptive parents in California, Berry (1993) found that adoptive parents were most likely to report high levels of satisfaction with adoption when the level of openness was consistent with their initial adoption plan. In a prospective study of 764 adoptive families, however, Berry et al. (1998) did not find openness to be a significant predictor of satisfaction and adjustment among adoptive parents four years after the initial placement of the child. In a series of studies, researchers from the MTAP also reported similarities and differences in adoptive parents across varying levels of openness (e.g., Grotevant & McRoy, 1998; Grotevant et al., 1994; McRoy et al., 1988; Von Korff et al., 2006; Wrobel, Ayers-Lopez, Grotevant, McRoy, & Friedrick, 1996). In general, these investigators found that adoptive parents in open adoption were satisfied with the adoption process (Grotevant et al., 1994) and that adopted children in open adoption did not experience more difficulties compared to adoptees in mediated or closed adoptions (Von Korff et al., 2006). Holleinstein, Leve, Scaramella, Milfort, and Neiderhiser (2003) also found evidence to suggest open adoption was beneficial; information about birth parents favorably influenced adoptive parents’ perception of the birth parents.

Methodological Issues

Some methodological difficulties remain in the conduct of adoption research, however. First, most of the previous studies on openness in adoption have been based on relatively small samples of either adoptive or birth families, making generalization of the findings difficult. Families and individuals involved in adoption, particularly birth parents, are considered to be hard-to-reach populations. Despite the fact that birth mothers represent an important component of the “adoption triangle” (Sorosky, Baran, & Pannor, 1978), they often remain “anonymous” or “hidden” and difficult to study, largely due to the sensitive and stigmatizing nature of adoption and relinquishment (March, 1995). Including birth mothers in studies of satisfaction with openness is critically important because a significant number of birth mothers have been found to have trouble “putting the experience behind them” or “moving on with their lives” (Fravel, McRoy, & Grotevant, 2000) following the placement of the child. Even less is known about the birth fathers of adopted children (Brodzinsky, 2005; Miall & March, 2005a). Indeed, Sachedev (1991) called birth fathers “a neglected element in the adoption equation” (p. 131). Many adoption studies have examined birth and adoptive parents separately. However, a clearer picture would emerge if information were obtained about openness and post-adoption adjustment from all parties involved. In this study, the effect of openness on post-placement adjustment was examined using a large sample of both adoptive and birth parents recruited across the United States.

Second, when larger samples have been available, previous studies have tended to rely only on a single source of information to assess the levels of openness. A common and best known practice has been to categorize adoption into three levels -- confidential (closed), mediated (semiopen), and fully disclosed (open) (see Grotevant & McRoy, 1998). While the use of a single source of information is helpful to obtain the informant’s experience and perception toward adoption process, such experience may not necessarily be shared by the other parties involved. The present study used a comprehensive approach to assessing the levels of openness by directly examining perceived degree of openness, the amount of actual contact, and the degree of knowledge about each other, as reported by each participating adoptive and birth parent. This comprehensive assessment approach to the construct of openness provides more reliable information on the effects of openness.

Third, in most previous studies that investigate the effect of openness in adoption, assessments of adoptive or birth parents were conducted with varying lengths of time since placement. Such a practice makes deriving clear inferences difficult because the effect of openness on adoptive and birth parents may vary depending on how long ago the placement occurred. In other words, the length of time since placement may very well be a confounding factor. The current study assessed participants at a relatively uniform length of time, birth parents at approximately 6-months and adoptive parents at approximately 9-months after placement. This methodological adjustment should allow for more rigorous inferences about the effect of openness.

To summarize, the present study was designed to examine the associations between openness in adoption and post-adoption adjustment of birth and adoptive parents while overcoming some of the methodological issues in previous studies. Specifically, measures of openness were obtained from both birth and adoptive parents at a fixed time period, when adopted children were 6–9 months of age. Higher levels of openness were hypothesized to be significantly and positively related to post-adoption well-being as measured by participants’ satisfaction with the adoption process and post-adoption adjustment.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

The Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS) is an ongoing, longitudinal multi-site study of adopted children, adoptive families, and birth parents. The primary goal of the EGDS is to examine the effects of genotype-environment interaction and correlation on the social and emotional development of infants and toddlers. The EGDS drew its sample from 33 adoption agencies in 10 states in three regions: Northwest, Southwest, and Mid-Atlantic. These agencies reflect the full range of US adoption agencies: public, private, religious, secular, those favoring open adoptions, and those favoring closed adoptions. Each agency recorded the demographic information from all clients who met our recruitment criteria (domestic adoption placement to a non-relative within 90 days of birth). More information about the sample and recruitment methods can be found in the article by Leve et al. (2007).

By April 2007, the EGDS recruited 531 birth mothers and 380 adoptive families (both/either adoptive mothers and adoptive fathers). Of these, 359 linked adoption triads (i.e., birth mothers, adoptive parents, and adopted child) were identified. This study is based on the first wave of data obtained from 323 matched adoptive parents and birth mothers who provided complete information on the study variables used here (i.e., indices of adoption openness and adjustment variables).

Because the sample was recruited from three different geographical regions, we examined regional differences in sample demographic characteristics (i.e., age, income, education of birth and adoptive parents). Only two significant regional differences were found: adoptive fathers’ education was slightly higher in the Northwest site than in the Southwest site and birth mothers’ household income was slightly higher in the Mid-Atlantic site than the Southwest site. Comparison of the participants who were included in and excluded from this study revealed no significant differences in terms of demographic variables such as income, education, and age.

A unique feature of the present study is the inclusion of birth fathers. Due to the challenges associated with recruiting this population, data from only 112 birth fathers who were linked to their adoption triads (i.e., adoptive parents, birth mothers, and the adopted child) were collected by April 2007. Given their smaller sample size, results for birth fathers are reported in a subsidiary analysis. Though preliminary, these data begin to fill a critical void in the literature.

Ninety-four percent of adoptive mothers and 92 percent of adoptive fathers in this sample were Caucasian. These estimates for Caucasians are higher than the Census 2000 national estimates of adoptive parents’ race/ethnicity composition (71% of adoptive parents were non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic, see Kreider, 2003 for details). Among birth mothers, 77% were Caucasian, 11% were African American, 4% were Hispanic American, and 8% were other racial/ethnic background. Eighty-four percent of the birth fathers were Caucasian, 6% were African American, 4% were Hispanic American, and 5% had other racial/ethnic background. The mean ages at the time of placement were 37.04 (SD=5.46), 38.01 (SD=6.00), 24.3 (SD=6.09), and 25.10 (SD=7.14) for adoptive mothers, adoptive fathers, birth mothers, and birth fathers, respectively. Nearly half of the adoptive parents were characterized as affluent and had annual gross household income that exceeded $100,000. More than 70% of adoptive parents had completed college education or advanced to further education. College degree was the mode of education level for both adoptive mothers and fathers (45.6%, 39.3%, respectively). On average, birth mothers’ and birth fathers’ personal income were $7,416 and $13,515, respectively. High school degree was the mode of birth mothers’ and fathers’ educational attainment (32.6%, 45.95%). Forty-three percent (n = 139) of the adopted children involved in the target sample of adoptive and birth parents were female. Fifty-nine percent of the adopted children were Caucasian, 20% were mixed races, 11% were African American, and 10% were unknown.

Birth parents participated in a 2-hour interview in their home or in another location convenient for them at approximately 6-months post-placement (when the child was 6 months old). Adoptive parents participated in a 2 ½ hour interview in their home at 9-months post-placement (when the child was 9 months old). Participants were paid for volunteering their time to the study. For both the birth- and adoptive-parent assessment, computer-assisted interview questions were asked by the interviewer to the participant, and each participant independently completed a set of questionnaires. Domains assessed for both adoptive and birth parents included personality, psychosocial adjustment, life events, and the adoption placement. In addition, adoptive parents were observed in a series of interaction tasks with their child (e.g., teaching and temperament tasks). Interviewers completed a minimum of 40 hours of training including a two-day group session, pilot interviews, and videotaped feedback, prior to administering interviews with study participants. All interviews were audio recorded and feedback was provided by a trained evaluator for a random selection of 15% of the interviews to ensure adherence to the study’s standardized interview protocols.

Measures

Measuring Openness in Adoption

Openness in adoption was measured using three subscales independently reported by each birth and adoptive parent: perceived openness, actual contact between adoptive and birth parents, and the amount of knowledge of one another between birth and adoptive parents. This measurement strategy is consistent with Grotevant and McRoy’s (1998) conceptualization of openness as “a spectrum involving different degrees and modes of contact and communication between adoptive family members and a child’s birth mother” (p. 2). The measure of openness differs from the tripartite categorical classification of closed, semi-open, and open adoption in Grotevant and McRoy (1998) and reflects a continuum of openness. Each of these subscales is described below.

Perceived Openness

Birth mothers and fathers individually reported, on a 7-point scale ranging from very closed (1) to very open (7), their overall ratings on the degree of openness they experienced in their adoption process. Interviewers gave a detailed description of the response options. For instance, the interviewers provided birth parents a definition of “very closed (1)” as “you have no information about the adoptive parents”, “open (5)” as “you have 1 to 3 visits per year and communicate semi-regularly by phone, letters, or emails with the adoptive family, and “very open (7)” as “you have visits with the family at least once a month and communicate several times a month by phone, letters, or emails”.

Adoptive parents responded to a question, “how open would you describe the adoption right now?” They were presented with 3 initial choices to narrow down the openness options (1 = closed or somewhat closed; 2= somewhat open; and 3 = pretty open). “Closed or somewhat closed” was defined as “no direct contact with a birth parent” and “pretty open” as “somewhat regular contact with a birth parent”. Adoptive parents were then followed up with more detailed questions depending on their answer to this initial question. If they chose “closed or somewhat closed”, they were asked to provide more detailed description of their adoption experience, using three-point response scale from “very closed”, “closed”, and “semi open”. The definitions of response options (i.e., “very closed”, “closed”, and “semi open”) were explicitly provided to enhance participants’ understanding of the concept. If they chose “somewhat open” as their answer to the initial question, adoptive parents were asked to indicate their adoption experience in more details using three-point scale from “semi open”, “moderately open”, and “open”. Those who chose “pretty open” in the initial question were asked to describe their experience using three-point scale consisting of “open”, “quite open”, and “very open”. Summarizing these items allowed a 7-point scale of openness, ranging from very closed (1), closed (2), semi open (3), moderately open (4), open (5), quite open (6), to very open (7). This response scale corresponds to the response scale presented to birth parents.

Contact

Birth mothers and birth fathers individually reported on how much contact they had with the adoptive parents. Adoptive mothers and fathers reported separately on how much contact they had with the birth mother and birth father because unlike adoptive parents, most birth parents were not a couple. To measure the birth mother-report of their contact with the adoptive parents and the birth father-report of their contact with the adoptive parents, each birth parent was asked to indicate how often the adoptive parents engaged in four different types of contact with him/her on a 5-point scale ranging from never (1) to daily (5): sent or gave their photos, exchanged letters or emails, talked with him/her on the phone, and had face-to-face contact (αs = .74 for both birth parents). For the adoptive father- and adoptive mother-reports of their contact with the birth mother, each adoptive parent responded to the same four items as above to describe their engagement in keeping contact with the birth mother plus two additional items rated on the same 5-point scale: how often the birth mother sent them e-mails/letters and how often the birth mother sent presents to the child (αs = .80 and .79 for adoptive fathers and mothers, respectively). For the adoptive father- and mother-reports of their contact with the birth father, each adoptive parent again responded to the same six questions to report how often the birth father keep contact with him/her (αs = .87 and .86 for adoptive fathers and mothers, respectively). Higher scores in these scales indicated more frequent contact between adoptive families and birth parents.

Knowledge

Birth mothers and birth fathers reported how much knowledge they had with the adoptive mother and father. On a 4-point scale ranging from nothing (1) to a lot (4), birth mothers indicated the extent to which they knew about five aspects of each adoptive parent: his/her physical health, mental health, ethnic and cultural background, his/her reasons for adoption, and their extended family’s health history. These items created scales of birth mothers’ knowledge about the adoptive father (α= .85) and their knowledge about the adoptive mother (α= .82). Birth fathers answered to the same set of questions that measured birth fathers’ knowledge about the adoptive father (α=.90) and their knowledge about the adoptive mother (α= .88). Similarly, adoptive mothers and fathers independently answered the same questions that assessed adoptive mothers’ and fathers’ knowledge about the birth mother (αs = .80 for both adoptive parents) and their knowledge about the birth father (αs = .87 and .86 for the adoptive father- and mother-reports, respectively). Higher scores indicated more knowledge about the other party.

Aggregated Openness Measure

The perceived openness, contact, and knowledge subscales were combined to create an aggregated openness measure for each informant (i.e., adoptive fathers, adoptive mothers, birth mothers, and birth fathers). This procedure created six aggregated openness measures: adoptive father- and mother-reported openness with respect to the birth mother (both αs=.74), birth mother-report of openness (α=.78), adoptive father- and mother-reported openness with respect to the birth fathers (αs=.61 and .59, respectively), and birth fathers-report of openness (α=.86). Each subscale was standardized before aggregating because the measures of perceived openness, contact, and knowledge had different response formats.

One possible confound in the study is selection effect. That is, more troubled birth and adoptive parents may choose closed adoption because they are less willing to share their information to other families involved in adoption. To address this issue, associations between depression, anxiety, and annual income of birth and adoptive parents and their reports of openness were examined. No significant correlations of self-reported depression and anxiety and annual income with the degree of openness in any parties involved in adoption were found. Interestingly, however, adoptive mother-report of openness was positively related to their report of anxiety (r = 0.12, p<.05), suggesting that adoptive mothers in more open adoptions tended to be more anxious, contrary to the direction of expectation for selection effects.

Satisfaction with the adoption process

Previous studies have shown that the degree of openness is associated with satisfaction with the adoption process (Berry, 1993; Grotevant et al., 1994). To measure levels of satisfaction, birth mothers and fathers independently used a 4-point scale ranging from very dissatisfied (1) to very satisfied (4) to report on their satisfaction with: (a) the amount of information about the adoptive mother, (b) the amount of information about the adoptive father, (c) the amount of contact with the adoptive family, and (d) the levels of openness of the adoption plan. Responses of these 4 items were internally consistent (αs = .80 and .89 for birth mothers and fathers, respectively), and were thus combined. In a similar fashion, adoptive fathers and mothers independently completed items using the same 4-point scale regarding their satisfaction with: (a) the amount of information about the birth mother, (b) the amount of information about the birth father, (c) the amount of contact with the birth mother, (d) the amount of contact with the birth father, and (e) the levels of openness of the adoption plan. These items were combined to form a scale of adoptive fathers’ and mothers’ satisfaction (both as =.64). Higher scores indicated higher satisfaction with the adoption process.

Post-adoption adjustment

Two indices were used to assess birth parents’ adjustment. First, on a 5-point scale ranging from improved a lot (1) to a lot worse (5), a birth parent indicated the extent to which going through adoption affected his/her: (a) quality of romantic relationship, (b) financial well being, (c) physical health, (d) mental and emotional health, (e), friendships, (f) relationships with his/her spouse/partner, (g) general satisfaction with life, (h) satisfaction with physical appearance, (i) relationship with his/her parents, (j) sense of control over his/her life, and (k) ability to plan for his/her future (αs = .78 and .84 for birth mothers and fathers, respectively). The responses were reverse-coded and summed so that the higher scores indicated better post-adoption adjustment.

Second, trained interviewers provided ratings of each birth parent. After completing a 2-hour in person interview, interviewers completed 16 items regarding their impressions of the birth parents’ adjustment using a 4-point scale, ranging from very true (1) to not true (4). Sample items included, “respondent seemed anxious”, “respondent did or said things to clearly indicate depression or sadness”, “respondent seemed irritable or hostile”, and “respondent seemed to feel well”. Items were coded such that higher scores indicated better adjustment of birth parents in the eyes of interviewers. Observers’ subjective impression of participants has been found to be reliable and valid, and shown to be a useful and cost-effective supplement to naturalistic observation procedures (Weinrott, Reid, Bauske, & Brummett, 1981). Interviewers’ impression demonstrated reasonably high internal consistency in the present study (αs=.86 and .88 for birth mothers and fathers, respectively). In terms of convergent validity, although no comparable measure of self-reported global well-being was collected in this study, modest associations would be anticipated between this measure and global self-worth as assessed by the Harter Adult Self-Perception Profile (Messer & Harter, 1986). Analyses indicated that interviewer ratings of birth mothers were marginally, yet positively associated with the self-reported global self worth subscale (r = .10, p < .10). For birth fathers, this correlation was non-significant (r = .08, ns).

Adoptive parents’ post-adoption adjustment was measured somewhat differently. First, adoptive parents completed items regarding the extent to which the adoption process affected (a) quality of their relationship, (b) their relationship with their other children, (c) physical health, (d) mental and emotional health, (e) friendships, (f) relationships with in-laws, (g) general satisfaction with life, (h) social life, (i) relationship with his/her parents, (j) career or professional life. Items were rated on a scale ranging from a lot worse (1) to improved a lot (5). The items were added to form a scale of adoptive parents’ adjustment to the adoption process (αs = .62 and .70 for adoptive fathers and mothers, respectively). Second, using the same 5-point response scale, adoptive parents also were asked how much each of the ten domains of the adoptive process improved after having the adopted child. We summed the items to create a scale of adoptive parents’ adjustment after welcoming the adopted child to their home (αs = .73 and .74 for adoptive fathers and mothers). For both scales, higher scores indicated better post-adoption adjustment.

Covariates

Several demographic (i.e., household income and education) and possible confounding variables were included in the analyses. One potential confounding variable in predicting adoptive parents’ post-adoption satisfaction and adjustment is the presence of biological children in the adoptive family. Of the 323 adoptive families, 53 (16%) had at least one biological child. There was no significant difference between adoptive families with and without biological children of their own in terms of adoptive fathers’ satisfaction and adjustment indices. However, compared to adoptive mothers who had biological children of their own, adoptive mothers who did not have any biological child were more likely to report that the experience of adoption process and welcoming the adopted child to the home positively affected their adjustment (Fs=5.79, 7.41, ps<s.01, respectively). We thus included the presence of biological child in adoptive family in the model for adoptive mothers.

Another covariate that requires attention is the level of choice/control each adoptive party had in deciding the level of openness in adoption. For instance, adoptive and birth parents who had choices in selecting the level of openness may feel more satisfied with the adoption process. In this study, adoptive and birth parents were asked to respond to a question of “How much choice did you have regarding level of openness?” Their responses were scaled to a 3-point response ranging from no control (either agency has a pre-establishing policy on the level of openness, or other birth/adoptive parents decided), some control (negotiated with the parties involved in the adoption), to full control (the respondent decided the level of openness). Higher scores indicated higher levels of control/choice the respondent had in determining the openness level. The level of choice in deciding the openness level was not associated with satisfaction or adjustment indices among adoptive parents and birth mothers. For birth fathers, however, it was positively associated with satisfaction (r = .23, p < .05), showing that birth fathers reported higher satisfaction toward the adoption process when they had higher levels of control in deciding the levels of openness. Thus, this covariate was included in the birth fathers’ model in predicting their satisfaction with the adoption process.

Overview of Analyses

We first examined descriptive statistics of the study variables. We then reported bivariate correlations between the degrees of openness reported by three distinctive informants (i.e., adoptive fathers and mothers, and birth mothers) and their adjustment indices. Next, we performed a series of structural equation modeling to test whether openness in adoption was associated with post-placement adjustment of adoptive fathers, mothers, and birth mothers. As a subsidiary analysis, we examined bivariate correlations between openness in adoption and birth fathers’ post-adoption psychological adjustment. The analysis of the birth father sample was conducted separately from the above-mentioned analyses for adoptive parents and birth mothers due to the smaller sample size.

Results

Descriptive and Correlational Analyses

Means and standard deviations of the study variables are presented in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, the means for openness were above 4.5 in a 7-point scale for all adoptive parties, showing that, on average, the sample perceived their adoption processes to be slightly open. Table 2 describes the frequency of this 7-point perceived openness scale. For all four parties, the modes and medians were 5 with slightly negatively skewed distributions (skewness = −.22, −.27, −.34, and −.50 for adoptive fathers, adoptive mothers, birth mothers, and birth fathers, respectively). These descriptive statistics indicate that the adoption practices in our sample were slightly skewed toward being more open. Only one adoptive mother, one birth mother, and seven birth fathers perceived their adoptions as “very closed.” Approximately 62% of adoptive fathers, 64% of adoptive mothers, 71% of birth mothers, and 57% of birth fathers perceived their adoptions to be “open” to “very open.” However, as evident from Table 2, substantial variation in their responses was evident.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of the Study Variables

| Adoptive Father |

Adoptive Mother |

Birth Mother |

Birth Father |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Measures of openness of adoption processa | ||||||||

| Openness of adoption process | 4.60 | 1.31 | 4.69 | 1.30 | 5.06 | 1.32 | 4.50 | 1.54 |

| Knowledge about birth mothers | 16.27 | 2.66 | 16.52 | 2.69 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Knowledge about birth fathers | 10.24 | 4.27 | 10.37 | 4.35 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Knowledge about adoptive mothers | -- | -- | -- | -- | 14.01 | 3.91 | 12.52 | 4.84 |

| Knowledge about adoptive fathers | -- | -- | -- | -- | 13.97 | 4.00 | 12.44 | 4.57 |

| Contact with birth mothers | 12.16 | 3.09 | 12.48 | 3.14 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Contact with birth fathers | 7.73 | 2.56 | 7.71 | 2.49 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Contact with adoptive parents | -- | -- | -- | -- | 17.39 | 4.41 | 15.21 | 4.31 |

| Satisfaction toward adoption process | 15.77 | 2.57 | 15.18 | 2.67 | 13.89 | 2.76 | 12.96 | 3.37 |

| Measures of post-adoption adjustment | ||||||||

| Improved well-being after adopting the child | 31.42 | 4.26 | 31.85 | 4.72 | 33.39b | 6.18 | 34.34b | 5.85 |

| Post-adoption adjustment | 31.89 | 4.40 | 33.31 | 5.05 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Interviewer's impression of well-being | -- | -- | -- | -- | 14.22 | 1.73 | 13.77 | 1.69 |

Note . n=323 for adoptive fathers, adoptive mothers, and birth mothers. n=112 for birth fathers.

The descriptive statistics for the measures of openness shown in Table 1 is based on raw scores. In the subsequent analyses, these measures were standardized and aggregated.

These means are not readily comparable to the means for adoptive parents due to the differences in the possible ranges of the scales.

Table 2.

Frequency in the Measure of Openness in Adoption Process by Informants

| Adoptive Father |

Adoptive Mother |

Birth Mother |

Birth Father |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| "very closed" | 1 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.31 | 1 | 0.31 | 7 | 6.48 |

| 2 | 21 | 6.54 | 16 | 4.97 | 10 | 3.11 | 5 | 4.63 | |

| 3 | 56 | 17.45 | 54 | 16.77 | 32 | 9.94 | 12 | 11.11 | |

| 4 | 44 | 13.71 | 43 | 13.35 | 50 | 15.53 | 22 | 20.37 | |

| 5 | 132 | 41.12 | 131 | 40.68 | 115 | 35.71 | 37 | 34.26 | |

| 6 | 44 | 13.71 | 50 | 15.53 | 60 | 18.63 | 15 | 13.89 | |

| "very open" | 7 | 24 | 7.48 | 27 | 8.39 | 54 | 16.77 | 10 | 9.26 |

| missing | 2 | 1 | 1 | 215 | |||||

Table 3 presents correlations among the aggregated measure of openness, satisfaction with the adoption process, and post-adoption adjustment among adoptive parents and birth mothers. The correlations indicate that the degree of openness in the adoption process was significantly related to satisfaction with the adoption process. This pattern was consistent regardless of who reported satisfaction or openness. Interestingly, openness was not significantly associated with adoptive fathers’ post-adoption adjustment or improved well-being after adopting the child. For adoptive mothers, openness was modestly associated with improved wellbeing after adoption of the child. However, no significant association between openness and adoptive mothers’ post-adoption adjustment emerged. For birth mothers, openness was positively correlated with their post-adoption adjustment and interviewers’ impression of their well-being.

Table 3.

Zero-order Correlation Coefficients between Degree of Openness and Post-adoption Satsifaction and Adjustment

| Adoptive Father |

Adoptive Mother |

Birth Mother |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opennessa | Satisfaction | Adjustmentb | Improved Well-beingc | Satisfaction | Adjustmentb | Improved Well-beingc | Satisfaction | Adjustment | Positive Impression |

| Adoptive Father | 0.16 ** | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.20 ** | 0.05 | 0.11 * | 0.14 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.15 ** |

| Adoptive Mother | 0.14 ** | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.22 ** | 0.06 | 0.12 * | 0.12 * | 0.19 ** | 0.15 ** |

| Birth Mother | 0.12 * | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.14 ** | 0.06 | 0.09 + | 0.31 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.13 ** |

Note. p<.10

p <.05

p <.01

N=323 matched adoptive families and birth mothers.

Openness is a combination of three subscales (i.e., openness, contact, and knowledge).

Post-adoption adjustment after going through adoption process.

Well-being after adopting the child.

We also computed correlations among the observed variables that together formed a latent construct in subsequent structural equation modeling analyses (not shown). Two observed variables of adoptive parents’ post-adoption adjustment (i.e., adjustment after going through the adoption process and improved well-being after adopting the child) were highly correlated (rs = .84 and .78 for adoptive fathers and adoptive mothers, respectively), suggesting that it is reasonable to form a latent construct from these two measures of adjustment. The correlations among the indices of openness reported by three different informants (i.e., adoptive fathers, adoptive mothers, and birth mothers) ranged from .66 to .81, showing a reasonable agreement. However, birth fathers’ report of openness did not produce such a high convergence with adoptive parents’ report of openness with birth fathers (rs =.56 and .45, p < .01, with adoptive fathers’ and mothers’ report of openness, respectively). Given the smaller sample size of birth fathers and a moderate agreement between adoptive parents’ and their report of openness, we decided to conduct a separate, subsidiary analysis for birth fathers.

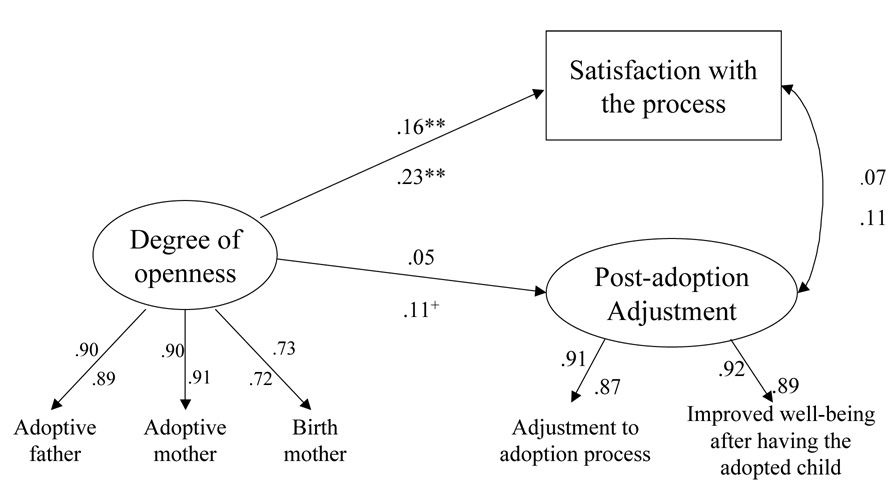

The Effect of Openness in Adoption on Adoptive Parents’ Post-Adoption Adjustment and Satisfaction

The hypothesis regarding the link between openness in adoption process and post-placement adjustment among birth and adoptive parents was tested using LISREL 8.72 (Joreskog & Sorborm, 2005). The results of the structural equation models for both adoptive fathers and mothers are shown in Figure 1. The coefficients presented in Figure 1 are based on standardized solutions. Although not shown in the figure, adoptive parents’ household income was controlled in the analyses. Adoptive parents’ income was not significantly associated with either their post-adoption adjustment or their satisfaction with adoption process. Additionally, for the adoptive mothers’ model, the presence of a biological child of their own in adoptive families, which was not significantly associated with outcomes, was also controlled. As shown in Figure 1, openness reported by three independent reporters loaded significantly on a latent construct (λs = .72 to .91). The loadings of two indicators assessing adoptive parents’ post-adoption adjustment also were significant for both adoptive-father and adoptive-mother models (λs = .87 to .92).

Figure 1.

Structural equation model of the link between openness in the adoption process and adoptive parents’ post-adoption adjustment.

Note. ** p<.01. + p<.10. Coefficients above denote loadings for adoptive fathers, and below for adoptive mothers. Although not shown, adoptive parents’ household income was controlled for both models and the presence of biological children for the adoptive mothers’ model.

As expected, a statistically significant path from openness to satisfaction emerged (βs = .16 and .23, ps<.01, for adoptive fathers and mothers, respectively), indicating that adoptive parents were more satisfied when there was more contact and communication with the birth mother. The coefficient for the path between openness and adoptive fathers’ post-adoption adjustment did not reach statistical significance. For the adoptive mother model, the association between openness and post-adoption adjustment was only marginally significant (β = .11, p<.10). The fit of two models was satisfactory, χ2 (12) = 7.07, RMSEA=.00, GFI = .99, for adoptive fathers; χ2 (18) = 15.30, RMSEA=.00, GFI = .99, for adoptive mothers.

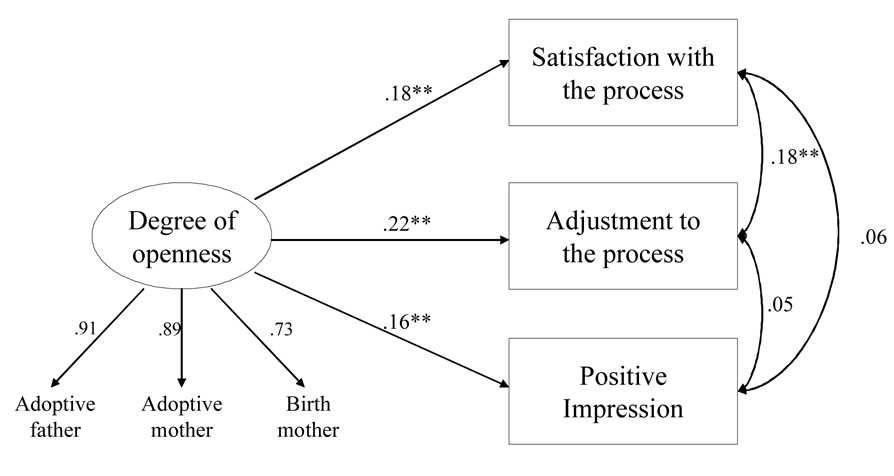

The Effect of Openness on Birth Mothers’ Post-Adoption Adjustment and Satisfaction

The results for birth mothers are presented in Figure 2. Although birth mothers’ income and educational level were controlled in these analyses, they are not included in the figure for the parsimony of graphical presentation. The paths from birth mothers’ income and education to three outcome variables were not statistically significant, except that birth mothers’ income was positively associated with interviewers’ impression of birth mothers’ well-being (β = .15, p<.01).

Figure 2.

Structural equation model of the link between openness in the adoption process and birth mothers’ post-adoption adjustment.

Note. ** p<.01. Although not shown, birth mothers’ income and education were controlled.

Estimation of this model yielded a good fit to the data, χ2 (12) = 38.12, RMSEA=.08, GFI = .97. Consistent with the results for adoptive parents, openness was positively and significantly associated with birth mothers’ satisfaction with adoption process (β = .18, p<.01). Also consistent with expectations, openness was positively associated with birth mothers’ post-adoption adjustment (β = .22, p<.01). The finding of an association between openness and adjustment was further strengthened by the significant path from openness and interviewers’ impression of birth mothers’ well-being (β = .16, p<.01). Taken together, these results suggest that birth mother’s post-adoption adjustment was enhanced when she kept in contact with adoptive parents.

A Subsidiary Analysis for Openness and Birth Fathers’ Adjustment

To supplement the findings for birth mothers, we examined the associations between birth fathers’ adjustment and openness in adoption. This analysis was conducted separately from other analyses because (a) there were only 112 participating birth fathers, as opposed to 323 birth mothers who were linked to the other members of adoption triads and (b) birth father-reported openness does not converge with that of other informants. Table 4 presents the correlations between the four indices of openness and birth fathers’ post-adoption adjustment. As mentioned earlier, because the preliminary analyses showed that the levels of choice/control birth fathers had in determining the degree of openness was positively associated with birth fathers’ satisfaction toward the adoption experience (r = .23, p < .05), we included it as a covariate upon computing the coefficients for birth fathers’ satisfaction. The results indicated that birth father-report of openness was positively correlated with his satisfaction with the adoption process (r = .41, p < .01) and post-adoption adjustment (r = .25, p<.01). However, this pattern of results was not apparent when adoptive parent-reports of openness were used. None of the openness indices was significantly associated with interviewers’ impression of birth fathers. Thus, the overall pattern of findings appeared to be quite different from that of birth mothers.

Table 4.

Correlation Coefficients between Degree of Openness and Birth Fathers' Post-adoption Satsifaction and Adjustment

| Birth Father |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | Satisfactiona | Adjustment | Positive Impression | |

| Adoptive Father | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.09 | |

| Adoptive Mother | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.06 | |

| Birth Father | 0.41** | 0.25** | 0.01 | |

Note. p <.01

N=112. The coefficients were computed based on pairwise deletion. Openness is a combination of three subscales (i.e., percieved openness, contact, and knowledge).

The levels of choice birth fathers had in deciding the degree of openness in adoption were statsitically controlled in computing coefficients between openness indices and satisfaction.

Discussion

Recent advances in assisted reproductive technologies and the availability of adoption placements have expanded the definition of what it means to be a parent. For some, it means a newfound ability to rear a child from birth onward; for others, it means the gift of giving life to another through an adoption placement or through assisted reproductive technologies (e.g., embryo, egg, insemination donation, or surrogacy). However, despite varied routes to parenthood, little is known about how the ongoing relationship between rearing and biological parents relates to their own psychosocial adjustment. Using a sample of matched birth and adoptive parents, this study examined the relationship between levels of adoption openness and post-placement satisfaction and adjustment among them. The results that emerged from this study are fairly straightforward: For adoptive parents and birth mothers, the degree of openness in the adoption was significantly and positively associated with satisfaction with the adoption process shortly after the adoptive placement. Increased openness was also significantly related to better post-placement adjustment of birth mothers. The finding that birth mothers who were involved in more open adoptions had better post-placement adjustment outcomes was further strengthened by interviewers’ reports of their impression of birth mothers’ well-being.

These results are in contrast to some earlier claims that open adoption would increase distress among birth and adoptive parents (e.g., Blanton & Deschner, 1990; Kraft et al., 1985), but are consistent with more recent findings by Grotevant and McRoy’s (1998) that voluntary open adoption tends to reduce the stress for all parents involved in adoption process. Although straightforward, these results have significant implications to adoption practices and offer some important information about settling the controversy of open vs. closed adoption. Our findings provide a formal evaluation of open adoption practices, showing that satisfaction with the adoption process for adoptive and birth parents, and post-adoption well-being of birth mothers are indeed higher when adoption process is more open.

Consistent with Kirk’s (1964) expectation, this study shows the beneficial effect of a new form of relationship that was forged in open adoption. In this special relationship, birth and adoptive parents come together to have what Kirk (1964) called “shared fate” to the benefit of the parties involved. The results reported here also provide evidence for the strength of what Granovetter (1973) termed “weak ties” where adoptive and birth parents are linked through special interpersonal relationships established by open adoption. The benefits to birth mothers appear to arise from exchanges and contacts with adoptive parents that provide informal sources of social supports. Assurance, security, and knowledge about the birth parents and the adopted child gained through open contacts with birth parents appear to enhance the adoptive parents’ satisfaction.

The robust associations between openness and post-adoption adjustment among adoptive parents did not emerge, however. Openness was not associated with post-adoption adjustment for adoptive fathers, and only modestly with adoptive mothers. Quite possibly, the advantages and disadvantages for adoptive parents in open adoption might cancel each other out. For instance, results obtained from the interviews with adoption agency personnel (Grotevant & McRoy, 1998) and a community survey (Miall & March, 2005b) documented both advantages and disadvantages of open adoption for adoptive parents. The advantages included adoptive parents’ increased sense of entitlement to the adopted child, reduced fear of birth parents, benefits of knowing the medical and psychological background of the child. Disadvantages included adoptive parents’ feeling threatened by birth parents, the possible complexity and challenge created by contacts, and adoptive parents’ fear of interference by birth parents in raising the child. Indeed, McRoy and Grotevant (1988) reported that while adoptive parents in open adoption were, in general, satisfied with the amount of contact with the birth parent, adoptive parents in direct contact with birth mothers did express some concerns about the maturity of birth mothers and the amount of time and energy that contact with them demanded. Perhaps increased contact with birth parents also increases the demands for adoptive parents’ time and energy during a time when adoptive parents, many of whom are first time parents, are busy adapting to the parental role. Although adoptive parents in open adoption felt that openness was in the best interests of the children, 9-months post-placement may well be a highly challenging time for them. At this time, their adjustment and well-being may be more affected by how they adapt to their lives of raising the adopted child than by the degree of contact with birth mothers. Indeed, a recent report by Gross, Shaw, Burwell, & Nagin (in press) showed child effects on maternal depression during the first 18 months of life.

The methodological advances made in this study are noteworthy. First, this study has made a contribution to the assessment of openness construct by showing utility of a multi-informant strategy. The multi-informant assessment strategy turned out to be very informative. Unlike many multi-agent measures, a fairly high agreement in openness emerged across informants. Such high convergent validity increases confidence in the results reported here. Second, openness was measured on a continuum instead of using a tripartite categorization. As pointed out by Brodzinsky (2005), continuous measures that including information sharing, contact, and communication should provide more fine-grained assessment of the subtle variation in the continuum of openness in adoption.

This study is among the first with a relatively large sample that includes both adoptive and birth parents linked through the adopted child to examine associations between openness and adjustment of birth and adoptive parents. A design that includes both birth mothers and birth fathers provides a more complete picture of the parties involved in the adoption processes. Previous research has tended to focus on adopted children and their adoptive parents (Brodzinsky & Schechter, 1990; Grotevant & McRoy, 1998; Smith & Brodzinsky, 2002). Few studies have investigated the post-adoption adjustment of birth mothers who represent an important component of the “adoption triangle” (Sorosky et al., 1978). Understanding variation in post-adoption adjustment among birth fathers as well as the divergent trajectories of health of this “hidden” population has special relevance to preventive intervention efforts targeted at this at-risk population.

Finally, the possible confound of length of time since adoption was minimized by assessing our participants at a fairly uniform point in time (approximately 6 months for birth parents and 9 months for adoptive parents) since placement. This advance is not trivial, as it is the case that post-placement adjustment varies with length of time since placement. Although collecting data in a narrow window of time is challenging, the efforts are worthwhile because it provides more rigorous inference about the association.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

Some caveats of the present study must be noted. First of all, cross-sectional data that are collected shortly after adoptive placement (6 to 9 months) were used, which does not allow for a long-term investigation of the adjustment of birth and adoptive parents or the changing nature of openness over time. Because openness in adoption fluctuates with time as life circumstances and psychological state of both birth and adoptive families change (Grotevant, Perry, & McRoy, 2005), future studies would benefit from considering the longitudinal effects and long-term trend of openness on birth and adoptive parent adjustment. Second, this study focused only on the post-placement adjustment of birth and adoptive parents. Future studies examining the effects of openness on adopted children would enhance our understanding of the total benefits associated with open adoption. Third, although the contribution of birth fathers is not trivial, the smaller sample size posed analytical challenges and prevented the full evaluation of the study hypotheses. Fourth, although there is substantial variation in the degree of openness, the current sample had relatively open adoption experiences. Quite possibly, adoptive and birth parents who selected more open adoption practices would feel more satisfied with greater openness in adoption. This possibility should be considered when interpreting the results reported in this paper and planning future research studies. Fifth, as with many other studies, the presence of selection bias cannot be entirely eliminated. Although we examined a set of adoptive and birth parents’ characteristics that could potentially bias the levels of openness and satisfaction, it is still possible that some potential confounds were overlooked. The results should be view as preliminary before rigorous randomized trials are conducted. Sixth, birth and adoptive parents usually entered the adoption process with certain expectations about openness. It is likely that whether their expectations about openness were met or violated would affect their levels of satisfaction. Future research is likely to benefit from addressing whether a match or mismatch between their expected openness and actual openness accounts for the link between openness and satisfaction. Finally, readers are reminded that the magunitude of the standardized coefficients were small. It should be emphasized, however, that because of complexity in human behaviors and emotions, effects size are necessarily small in outcomes with multiple determinants (Ahadi & Diener, 1989). Nevertheless, given the methodological strengths such as use of multiple measures and infomants for both predictors and criterion variables, the significant findings raise our confidence in the results.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant 5-R01-HD 042608 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (David Reiss, MD, PI). Writing of this manuscript was partially supported by the Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota and by the College of Agriculture and Environmental Science of University of California, Davis. We would like to thank the birth and adoptive parents who participated in this study and the adoption agencies who help with our recruitment of the participants. Thanks also are due to Rand D. Conger who is part of the investigative team. Special thanks to Katie R. Schilling for her thorough review of the literature on birth mothers.

References

- Ahadi S, Diener E. Multiple determinants and effect size. Journal of Personality and social Psychology. 1989;56:398–406. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baran A, Pannor R, Sorosky AD. Open adoption. Social Work. 1976;21(2):97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann C. Adoptive fathers and birthfathers: A study of attitudes. Child and Adolescent Social Work. 1999;16:373–391. [Google Scholar]

- Berry M. Adoptive parents perceptions of, andcomfort with open adoption. Child Welfare. 1993;72:231–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M, Dylla DJC, Barth RP, Needell B. The role of open adoption in the adjustment of adopted children and their families. Children and Youth Services Review. 1998;20:151–171. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton TL, Deschner J. Biological mothers grief: The postadoptive experience in open versus confidential adoption. Child Welfare. 1990;69:525–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky DM. Reconceptualizing openness in adoption: Implications for theory, research, and practice. In: Brodzinsky DM, Palacios J, editors. Psychological issues in adoption. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2005. pp. 145–166. [Google Scholar]

- Brodzinsky DM, Schechter MD. The psychology of adoption. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bussiere A. The development of adoption law. Adoption Quarterly. 1998;1:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LH, Silverman PR, Patti PB. Reunions between adoptees and birth parents: The adoptees experience. Social Work. 1991;36:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapton G. Birth fathers and their adoption experiences. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingley Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- DeSimone M. Birth mother loss: Contributing factors to unresolved grief. Clinical Social Work Journal. 1996;24:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Deykin EY, Patti PB, Ryan J. Fathers of adopted children: A study of the impact of child surrender on birth fathers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1988;58:240–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1988.tb01585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fravel DL, McRoy RG, Grotevant HD. Birthmother perceptions of the psychologically present adopted child: Adoption openness and boundary ambiguity. Family Relations. 2000;49:452–433. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter MS. The strength of weak ties. The American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78:1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Gross H, Shaw DS, Burwell RA, Nagin DS. Transactional processes in child disruptive behavior and maternal depression: A longitudinal study from early childhood to adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000091. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, McRoy RG. Openness in adoption: Exploring family connections. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, McRoy RG, Elde CL, Fravel DL. Adoptive family system dynamics: Variations by level of openness in the adoption. Family Process. 1994;33:125–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1994.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD, Perry YV, McRoy RG. Openness in adoption: Outcomes for adolescents within their adoptive kinship networks. In: Brodzinsky DM, Palacios J, editors. Psychological issues in adoption: Research and practice. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2005. pp. 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Groth M, Bonnardel D, Davis DA, Martin JC, Vousden HE. An agency moves toward open adoption of infants. Child Welfare. 1987;66:247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T, Leve LD, Scaramella L, Milfort R, Neiderhiser JM. Openness in adoption, knowledge of birthparent information, and adoptive family adjustment. Adoption Quarterly. 2003;7:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog K, Sorborm J. LISREL (Version 8.72) Scientific Software International, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk HD. Shared fate: A theory of adoption and mental health. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft AD, Palombo J, Woods PK, Mitchell D, Schmidt AW. Some theoretical considerations on confidential adoptions, Part I: The birth mother. Child and Adolescent Social Work. 1985;1:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM. U.S. Census Bureau; Adopted children and stepchildren 2000: Census 2000 special reports (No. CENSR-GRV) 2003

- Lancette J, McClure BA. Birthmothers: Grieving the loss of a dream. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 1992;14:84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Ge X, Scaramella L, Conger RD, Reid JB, et al. The Early Growth and Development Study: A prospective adoption design. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:84–95. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J. Birth mothers and their mental health: Uncharted territory. British Journal of Social Work. 1996;26:609–625. [Google Scholar]

- March K. Perception of adoption as social stigma: Motivation for search and reunion. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:653–660. [Google Scholar]

- McRoy RG, Grotevant HD, White KL. Openness in adoption: New practices, new issues. New York: Praeger; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Messer B, Harter S. Manual for the adult self-perception profile. Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Miall CE, March K. Community attitudes toward birth fathers' motives for adoption placement and single parenting. Family Relations. 2005a;54:535–546. [Google Scholar]

- Miall CE, March K. Open adoption as a family form: Community assessments and social support. Journal of Family Issues. 2005b;26:380–410. [Google Scholar]

- Pannor R, Baran A. Open adoption as standard practice. Child Welfare. 1984;63:245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz M, Watson KW. Adoption and the family system: Strategies for treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev P. The birth father: A neglected element in the adoptin equation. Families in Society. 1991;72:131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DH. Open adoption of infants: Adoptive parents' feelings seven years later. Social Work. 2003;48:409–419. doi: 10.1093/sw/48.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman PR, Campbell LH, Patti PB, Style CB. Reunions between adoptees and birth parents: The birth parents' experience. Social Work. 1988;33:523–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein DR, Demick J. Toward an organizational-relational model of open adoption. Family Process. 1994;33:111–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1994.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DW, Brodzinsky DM. Coping with birthparent loss in adopted children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2002;43:213–223. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorosky AD, Baran A, Pannor R. The adoption triangle: The effects of the sealed record on adoptees, birth parents, and adoptive parents. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff L, Grotevant HD, McRoy RG. Openness arrangements and psychological adjustment in adolescent adoptees. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:531–534. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrott MR, Reid JB, Bauske BW, Brummett B. Supplementing naturalistic observations with observer impressions. Behavioral Assessment. 1981;3:151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel GM, Ayers-Lopez S, Grotevant HD, McRoy RG, Friedrick M. Openness in adoption and the level of child participation. Child Development. 1996;67:2358–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]