Abstract

Signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT1) signaling mediate most biological functions of IFNα, IFNβ and IFNγ although recent studies indicate that IFNγ can alter expression of several genes via a STAT1-independent pathway. STAT1 is critical for immunity against a variety of intracellular pathogens and some studies show that pathogens evade host immunity by interfering with STAT1 signaling. Here, we have investigated the role of STAT1 in host defense against pulmonary Francisella novicida infection using STAT1−/− mice. In addition, we examined the effect of F. novicida on STAT1 signaling in macrophages and on their ability to activate antigen-specific T cells. Both wild-type (WT) and STAT1−/− BALB/c mice were susceptible to aerosol challenge with 103 F. novicida and displayed 100% mortality. However, STAT1−/− mice developed more severe pneumonia, liver pathology and succumbed to infection faster than WT mice. The lungs, liver and hearts from F. novicida-infected STAT1−/− mice also contained more bacteria than WT mice at the time of death. In vitro studies showed that F. novicida suppressed IFNγRα (alpha subunit of IFNγ receptor) and MHC class II expression, down-regulated IFNγ-induced STAT1 activation and reduced nuclear binding of STAT1 in RAW264.7 macrophages. Furthermore, F. novicida-infected BMDM loaded with ovalbumin (OVA) were less efficient in activating OVA-specific CD4+ T cells in vitro. These findings demonstrate that STAT1-mediated signaling participates in the host defense against pulmonary F. novicida infection but it is not sufficient to prevent mortality associated with this infection. Moreover, our results show that F. novicida attenuates STAT1-mediated IFNγ signaling in macrophages and impairs their ability to activate antigen-specific CD4+ T cells.

Keywords: Francisella novicida, IFNγ, STAT1

Introduction

Signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT1) signaling mediate most of the biological functions of both type I and II IFN and have been shown to be important in host resistance to many intracellular pathogens. IFNγ stimulation results in activation of the Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT signal transduction pathway. IFNγ binds its receptor composed of the heterodimeric subunits, IFNγ receptor (IFNγR) α and IFNγRβ, whose cytoplasmic domains contain tyrosine activation motifs (ITAMs) and are in weak association with inactive JAK1 and JAK2. IFNγ binding results in receptor oligomerization and JAK phosphorylation. Active JAKs then phosphorylate the ITAMs of the IFNγRs, which recruit STAT1 molecules from the cytoplasm for subsequent phosphorylation. Phosphorylated STAT1 molecules dimerize and translocate into the nucleus where they activate transcription of specific genes by binding to γ activation sequences (GAS) in the DNA (1, 2). Disruption of this pathway is a common mechanism utilized by several intracellular pathogens for evading the host immune response. Mycobacterium avium, for example, inhibits STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling by down-regulating IFNγR expression, which results in reduced expression of IFNγ-inducible genes like class II transcriptional activator (CIITA) (3). However, the role of STAT1-mediated signaling during infection with the intracellular pathogen, Francisella, remains unknown.

Although the natural incidence of pulmonary tularemia is extremely low, the high infectivity, rapid dissemination and the severity of the disease caused by Francisella tularensis, has lead to its classification as a CDC Category A agent (4). Aerosol exposure of mice to Francisella novicida, a subspecies of F. tularensis that is non-pathogenic for humans, results in a fatal pneumonia that mimics the symptoms and pathology of the respiratory disease caused by F. tularensis in both humans and mice. Studies using an aerosol model have shown that the pathology and immune responses that result from aerosol infection with F. tularensis differ drastically from other means of generating a systemic infection (5, 6). Despite this, many aspects of the host immune response to primary pulmonary tularemia remain to be studied.

Macrophages serve as primary target cells for F. tularensis infection, as well as the main effector cells in host defense against this pathogen. It is well established that IFNγ plays a pivotal role in control of Francisella infection by activating macrophages to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and exert bactericidal activity. Several studies have shown that mice lacking IFNγ, either due to gene knockout or treatment with neutralizing antibodies, results in increased susceptibility to intra-dermal infection with the live vaccine strain (LVS) of F. tularensis (7, 8). Moreover, in vitro addition of rIFNγ stimulates macrophage production of nitric oxide (NO), which results in inhibition of LVS growth (9). However, Polsinelli et al. (10) have reported NO-independent killing of LVS by alveolar macrophages following IFNγ stimulation. Despite the importance of IFNγ in host defense to tularemia, it is unclear what role STAT1-dependent signaling plays in Francisella-infected macrophages.

The importance of T cell-mediated immune responses for resolution of secondary Francisella infection and development of protective immunity are well established, but the role of antigen-specific T cells following primary infection remains unclear. Only one in vivo study has addressed the role of CD8+ T cells following primary intra-nasal infection with LVS, demonstrating that IL-12 and IFNγ are required for survival of respiratory tularemia (11). Another recent in vitro study by Woolard et al. (12) describes a macrophage-dependent mechanism by which LVS modulates the host adaptive immune response to infection. They have shown that LVS-infected macrophages secrete prostaglandin E2, which blocks T cell proliferation. However, the response of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells to primary F. novicida infection is still undefined.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of STAT1-mediated signaling after primary infection with F. novicida. We have found that STAT1−/− mice are more susceptible to aerosol infection with F. novicida and are less able to control bacterial burdens and pathology in their organs than wild-type (WT) mice. Our in vitro results indicate that F. novicida disrupts STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling in macrophages, which leads to reduced MHC class II expression and decreased antigen-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation.

Methods

Animals

Sex-matched WT BALB/c (purchased from Harlan), DO.11 and STAT1−/− mice (8−10 weeks old) were housed and maintained under institutional guidelines for animal research at the Ohio State University. DO.11 transgenic mice express TCRs that specifically recognize OT2, a fragment from the ovalbumin (OVA) protein, expressed in the context of MHC class II molecules. Ten mice per group were used for survival experiments.

Bacteria and aerosol infection

WT and mutant strains of F. novicida U112 (JSG1819) were obtained from the laboratory of John Gunn at the Ohio State University. Francisella novicida was subcultured from Mueller–Hinton broth (BD, Sparks, MD, USA) freezer stocks supplemented with 20% glycerol and 0.1% cysteine onto chocolate II agar plates (BD) and grown for 24−48 h before use. Francisella novicida stocks were animal passaged every 3 months to maintain maximum virulence. Kanamycin was used for selection of pmrA mutants, while erythromycin was used for selection of mglA mutants. During aerosol infection, mice were anesthetized and infected by delivering 103 F. novicida colony-forming unit (CFU) in 50 μl directly into the trachea using a MicroSprayer™ aerosolizer, model A1C (Penn-Century, Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA) (13). Mortality was monitored and organs were harvested from deceased mice from each group for quantification of bacterial load and histopathology.

Quantification of organ burdens.

Bacterial loads in the lungs, liver and heart were determined at the time of death in WT and STAT1−/− mice following F. novicida infection as already described. Briefly, tissues from each group were pooled, homogenized and plated in 100-fold serial dilutions on cysteine heart agar (Research Products International Corp., Mt Prospect, IL, USA) supplemented with 2% bovine hemoglobin (BD). Organ homogenates were diluted in sterile 1× PBS, pH 7.4 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), supplemented with 2% heat-inactivated FCS. Colonies were counted after 24 h of incubation at 37°C.

Histopathology

Francisella novicida-infected lungs, livers and hearts from WT and STAT1−/− mice were excised and fixed in 10% formalin for 4 days. The tissues were processed and embedded in paraffin, and 4- to 8-μm sections were cut. The sections were hydrated and stained by routine hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Preparation of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM)

DO.11 mice were sacrificed and their femurs were harvested, cleaned of tissue and flushed with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 U penicillin ml−1, 100 μg streptomycin ml−1 and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (cRPMI). Erythrocytes were depleted with ammonium–chloride–potassium lysis buffer. Cells were washed and incubated in flasks containing cRPMI supplemented with 20% CSF-1. BMDM were used for experimentation after 5−7 days.

Isolation of Primed T cells

DO.11 mice were injected intra-peritoneally with 2 ml of [12 μg ml−1] OVA (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) at least 2 weeks prior to T cell harvest for priming. Spleens from the primed DO.11 mice were excised, pulverized and strained in RPMI supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 U penicillin ml−1, 100 μg streptomycin ml−1 and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol without serum. RBCs were lysed using 2-ml hemolytic solution per spleen and the remaining splenocytes were passed through a nylon wool column (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA, USA) for at least 1 h. T cells were collected from the column and the concentration was adjusted to 3–5 × 106 T cells ml−1.

Antigen-presenting cell assay

In all, 96-well plates were seeded with 7.5 × 104 DO.11 BMDM in cRPMI and incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. DO.11 BMDM, activated by exposure to [100 U ml−1] IFNγ for 48 h, were infected with F. novicida [multiplicity of infection (MOI) 25:1 bacteria per macrophage] for 2 h at 37°C and then exposed to [1500 μg ml−1], [1000 μg ml−1] or [500 μg ml−1] OVA for another 2 h at 37°C. T cells were added to the BMDM and supernatants were collected after both 24- and 72-h incubations and IL-2 production was measured with ELISA (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA).

Cell culture and in vitro infection of RAW264.7 cells

The macrophage cell line RAW264.7 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in suspension in cRPMI at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 in 75-cm2 cell culture flasks. Macrophages were seeded in six-well plates at 4 × 106 cells per well. Cells were cultured overnight. RAW264.7 macrophages were infected with F. novicida (MOI 25:1) for 4 h, incubating at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. After incubation, extracellular F. novicida was removed with a 30-min gentamicin treatment [100 μg ml−1] and washing with 1× PBS. RAW264.7 cells were treated with IFNγ [100 U ml−1] for 15 or 30 min for western blot experiments and 30 or 60 min for electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) experiments.

Flow cytometry

For flow cytometric analysis, RAW264.7 macrophages were infected with F. novicida as described above and stimulated with IFNγ [100 U ml−1] for either 4 or 12 h following infection. In total, 1−2 × 106 cells were stained with PE-conjugated antibodies for MHC class II molecules purchased from BD PharMingen. Flow cytometry analysis was then performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuestPro software (Becton Dickinson).

Cytoplasmic and nuclear extractions

Following treatment with IFNγ, RAW264.7 cells were solubilized in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 20 μg ml−1 Protease Arrest (GenoTech, St Louis, MO, USA). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 4°C at 14 000 × g for 15 min. The cytoplasmic supernatant was removed and stored at −80°C; the nuclear pellet was re-suspended in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 25% glycerol, 0.4 M NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, and centrifuged at 14 000 × g for 15 min. Total protein concentrations for both cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were determined by Bradford method using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA).

Western blotting

Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE (40 μg of protein was loaded into each well) using 8% acrylamide mini-gels (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA, USA), followed by transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Membranes were blocked in milk protein blocker (GenoTech) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 1.5 h and incubated with primary antibodies overnight. The detection step was performed with peroxidase-coupled anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (GenoTech; 1:5000). Primary antibodies were polyclonal anti-phospho STAT1 (dilution 1:2000), total STAT1 (dilution 1:2000) and IFNγRα (dilution 1:750). All antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and diluted in 5% milk protein blocker (GenoTech) suspension prepared in TBS with 0.1% Tween 20. Blots were developed with the femtoLUCENT detection system (GenoTech).

EMSA

EMSA were performed in 20-μl binding reactions containing 3.5 μg of nuclear extract, 100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 100 mM MgCl2, 50% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 μg poly(dI-dC) and 50 000 counts per minute of [32P]deoxycytidine triphosphate-labeled GAS probe radiolabeled by filling with Klenow DNA polymerase. The GAS probe used (5′-AGCCATTTCCAGGAATCGAAA-3’) contains the optimum GAS sequence (TTCCAGGAA) for STAT1 DNA binding (14). After 20-min incubation at room temperature, the binding reactions were subjected to electrophoresis on 5% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels in 5× TBE. Gels were subsequently dried and analyzed by autoradiography. In supershift assays, 1 μg of STAT1 mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was incubated with binding reactions for 20 min prior to addition of radiolabeled GAS probe.

Statistical analysis

A Kaplan–Meier curve was constructed from survival data of WT BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice and a log-rank test was applied to determine the statistical significance of survival differences between the two strains of mice. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Survival, organ burdens and pathology in WT and STAT1−/− mice after F. novicida infection

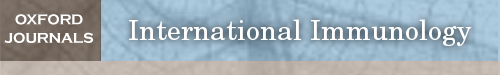

In order to determine how STAT1−/− and WT BALB/c control mice would respond to aerosol infection with 103 F. novicida, we compared survival, organ bacterial burdens and pathology. STAT1−/− mice succumbed to aerosol infection significantly sooner than their WT counterparts (Fig. 1A). Bacterial burdens were measured in their lungs, livers and hearts at the time of death and STAT1−/− mice showed higher bacterial loads in all organs, though liver burdens were not significant (Fig. 1B–D). We also compared the development of pathology in the lungs, livers and hearts of STAT1−/− and WT mice at the time of death. STAT1−/− mice developed more severe pneumonia and showed more inflammatory infiltration and formation of microabscesses in the liver compared with WT mice (Fig. 1H and I). Interestingly, the pericardial calcification, which we have reported previously and is evident in the hearts of WT mice, is absent in STAT1−/− mice (Fig. 1G and J). Together, these results show that STAT1−/− mice are more susceptible to aerosolized F. novicida infection than WT BALB/c mice. This difference in susceptibility could be due to the inability of STAT1−/− mice to control bacterial burdens and pathology in their organs compared with WT mice.

Fig. 1.

Survival curves (A), organ burdens (B–D) and histopathology of lungs, livers and hearts (E–J) from BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice following aerosolized Francisella novicida infection. (A) The survival of WT BALB/c (dotted line) and STAT1−/− (solid line) mice infected with 103 CFU of aerosolized F. novicida were compared. Groups of 10 BALB/c and 10 C57BL/6 mice were monitored in this experiment. Statistical significance was determined using a log-rank test, P < 0.001. Organ burdens in the lungs, livers and hearts of WT BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice were determined at 24-h intervals following aerosol infection with 103 CFU of F. novicida (B–D). Histological analysis of F. novicida-infected lung, liver and heart tissue from WT BALB/c (E–G) and STAT1−/− (H–J) mice are shown. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of all three organs is shown for BALB/c and STAT1−/− mice at day 4 post-infection. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments.

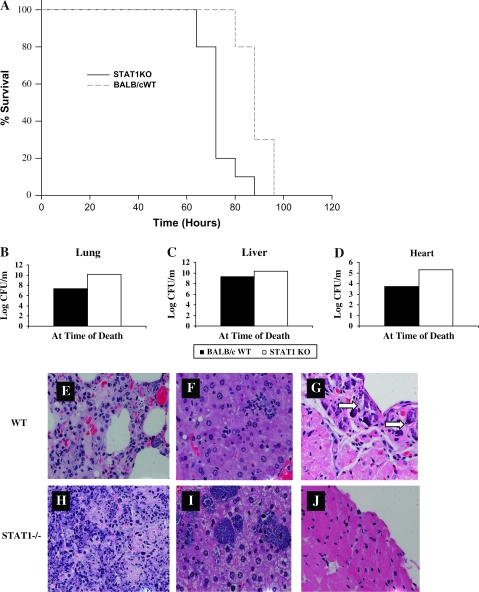

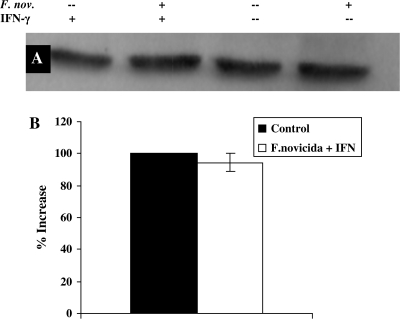

Expression of IFNγRα in macrophages following F. novicida infection

After finding that STAT1−/− mice are significantly more susceptible to aerosolized F. novicida infection than WT mice, we wanted to determine the role of STAT1-dependent signaling in macrophages during infection. Activation of the STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling cascade in macrophages begins when IFNγ binds to the alpha chain of the IFNγR. Therefore, we measured the amount of IFNγRα expression in RAW264.7 macrophages following F. novicida infection. Macrophages were infected for 4 h with F. novicida, stimulated for 15 min with [100 U ml−1] IFNγ and cytoplasmic extracts were collected and used for western blotting with anti-IFNγRα. When compared with uninfected controls that were stimulated with IFNγ, RAW264.7 macrophages infected with F. novicida showed a 31% decrease in IFNγRα expression (Fig. 2). However, IFNγRβ expression remained equivalent to that observed in control cells (data not shown). This data suggest that F. novicida disrupts this signaling pathway by specific reduction in IFNγRα, but not IFNγRβ, expression.

Fig. 2.

Effect of Francisella novicida infection on expression of IFNγRα on RAW264.7 macrophages. RAW267.4 macrophages were infected for 4 h with F. novicida at 25:1 bacteria per macrophage. Cells were stimulated with [100 U ml−1] IFNγ for 15 min. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed for IFNγRα (A) by western blot. The blots shown represent one of three experiments with similar results. (B) Densitometry analysis was plotted as percentage increase in IFNγRα expression relative to control cells (the percentage increase in expression in control cells is taken as 100) when stimulated with IFNγ. Data shown in the graphs are combined from three independent experiments and shown as mean percentage increase (±SEM). Student's t-test was used to determine that differences between groups were statistically significant, P < 0.03).

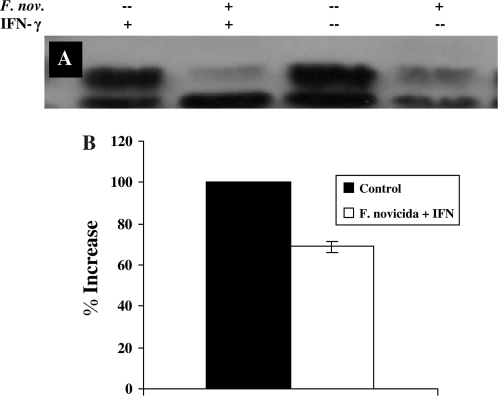

STAT1 expression and phosphorylation after F. novicida infection

Phosphorylation and translocation of STAT1 molecules into the nucleus is required for maximum expression of IFNγ-inducible genes in macrophages. In order to determine if reduced IFNγRα expression affects downstream activation of STAT1 in F. novicida-infected macrophages, we used western blotting to quantify both the total and phosphorylated STAT1 protein after treatment with IFNγ. Total STAT1 protein expression was statistically the same in both infected and uninfected RAW264.7 macrophages (Fig. 3A and C). However, phosphorylation of STAT1 was markedly reduced in F. novicida-infected RAW cells, showing a 40% decrease in phosphorylation compared with uninfected, IFNγ-stimulated macrophages (Fig. 3B and D). Therefore, we found that reduced receptor expression correlates with decreased phosphorylation and subsequent activation of STAT1 molecules.

Fig. 3.

Effect of Francisella novicida infection on phosphorylation of STAT1 in RAW264.7 macrophages. RAW267.4 macrophages were infected for 4 h with F. novicida at 25:1 bacteria per macrophage. Cells were stimulated with [100 U ml−1] IFNγ for 15 min. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed for total STAT1 (A) and phospho-STAT1 (B) expression by western blot. The blots shown represent one of three experiments with similar results. (C) Densitometry analysis was plotted as percentage increase in either total or phospho-STAT1 expression relative to control cells (the percentage increase in expression in control cells is taken as 100) when stimulated with IFNγ. Data shown in the graphs are combined from three independent experiments and shown as mean percentage increase (±SEM). Student's t-tests were used to determine that differences in phosphorylation of STAT1 between groups were statistically significant, P < 0.04, while total STAT1 expression was not, P < 0.42.

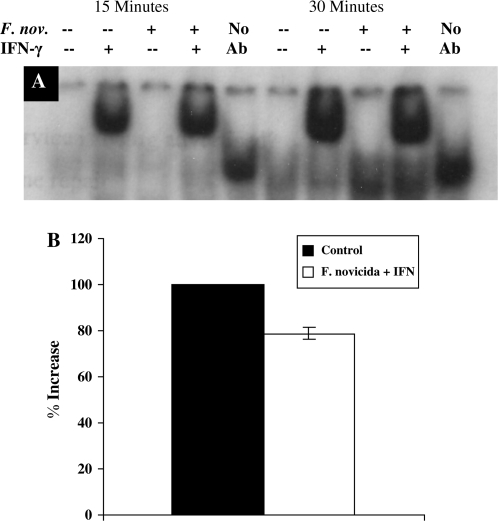

STAT1 binding to DNA following F. novicida infection

We have shown that F. novicida infection decreases expression of IFNγRα and reduces phosphorylation of STAT1, but it remained unclear whether reduced phosphorylation of STAT1 would result in less binding of STAT1 to GAS elements in the DNA. To determine if F. novicida infection affected STAT1–DNA binding, nuclear extracts were prepared and used for EMSAs. After 30 min of IFNγ stimulation, there was a 21% decrease in STAT1 supershift in F. novicida-infected cells compared with uninfected controls, while at 60 min following IFNγ stimulation, this STAT1 binding to DNA was equal to that of uninfected controls (Fig. 4). These data indicate that STAT1 binding to GAS in the DNA are reduced in macrophages infected with F. novicida.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of STAT1-DNA binding in Francisella novicida-infected and -uninfected RAW264.7 macrophages. (A) RAW264.7 cells were infected for 4 h with F. novicida at 25:1 bacteria per macrophage and then stimulated with [100 U ml−] IFNγ for 30 and 60 min. Nuclear extracts were prepared and incubated with [32P]-labeled GAS sequence and binding was assayed by EMSA gels. Nuclear extracts were pre-incubated with anti-STAT1 mAb for 20 min before addition of the radiolabeled probe to identify the STAT1 protein. These results are representative of two experiments. (B) Densitometry analysis was plotted as percentage increase in STAT1 supershift relative to control cells (the percentage increase in supershift in control cells is taken as 100) when stimulated with IFNγ. Data shown in the graphs are combined from three independent experiments and shown as mean percentage increase (±SEM). Student's t-test was used to determine that differences between groups were statistically significant, P < 0.04.

Expression of suppressors of cytokine signaling-3 in macrophages following F. novicida infection

Though we have already found that F. novicida infection down-regulates expression of IFNγRα in macrophages, we wanted to determine if suppression of STAT1 signaling via suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) 3 was also occurring. Therefore, we performed western blots, probing with SOCS3 antibodies, in order to ascertain if expression of this molecule was increased during infection. We found no significant differences in SOCS3 expression between F. novicida-infected and -uninfected controls (Fig. 5). Therefore, F. novicida infection of RAW264.7 macrophages does not disrupt STAT1-dependent signaling by increasing activity of the phosphatase, SOCS3.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Francisella novicida infection on expression of SOCS3 in RAW264.7 macrophages. RAW267.4 macrophages were infected for 4 h with F. novicida at 25:1 bacteria per macrophage. Cells were stimulated with [100 U ml−1] IFNγ for 15 min. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed for SOCS3 (A) by Western blot. The blots shown represent one of two experiments with similar results. (B) Densitometry analysis was plotted as percentage increase in SOCS3 expression relative to control cells (the percentage increase in expression in control cells is taken as 100) when stimulated with IFNγ. Data shown in the graphs are combined from two independent experiments and shown as mean percentage increase (±SEM).

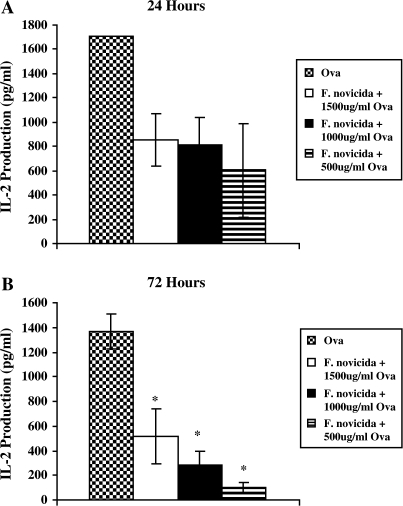

IL-2 production by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells stimulated by F. novicida-infected and -uninfected BMDMs

OVA-primed T cells from DO.11 mice were exposed to both F. novicida-infected and -uninfected, IFNγ-activated BMDM. At 24 and 72 h after T cell addition to this antigen-presenting cell (APC) assay, supernatants were collected and IL-2 production was measured using ELISA. At 72 h, IL-2 production was significantly decreased in T cells that were exposed to F. novicida-infected macrophages regardless of the concentration of OVA pre-treatment (Fig. 6B). Similar trends in IL-2 production were seen at 24 h, though this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 6A). However, previous studies using high-dose (MOI 50:1 or 500:1) LVS-infected J774.A1 cells have indicated that significant apoptosis occurs after 24 h of infection (15). In order to insure that differences in IL-2 production between infected and uninfected controls were not simply due to increased apoptosis in F. novicida-infected APCs, we determined the amount of dead BMDMs using trypan blue exclusion. Using IFNγ-activated BMDM, we found no significant increase in F. novicida-induced apoptosis up to 72-h post-infection (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that antigen-specific CD4+ T cells produce less IL-2 when exposed to F. novicida-infected BMDM.

Fig. 6.

Effect of Francisella novicida infection on IL-2 production by OVA-primed DO.11 T cells. OVA-primed T cells were harvested from the spleens and lymph nodes of DO.11 mice and were exposed to IFNγ-activated BALB/c BMDM that were infected with F. novicida (MOI 25:1) for 2 h and treated with OVA for 2 h prior to T cell addition. IL-2 production was measured in the supernatants after 24 (A) and 72 (B) h of infection by ELISA. Data show the mean (±SEM) of triplicate samples from two pooled wells per group from two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using Student's t-test. *P < 0.05 was considered significant and is denoted by an asterisk.

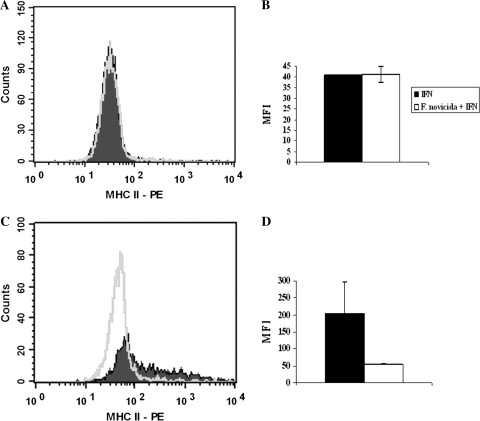

MHC class II expression on macrophages after F. novicida infection

Antigen-specific CD4+ T cells recognize antigen in the context of MHC class II molecules, which is normally increased on macrophages as a result of activation of the STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling pathway. Therefore, we quantified the amount of MHC class II molecule surface expression following IFNγ treatment in uninfected and F. novicida-infected macrophages in order to determine if infection was interfering with antigen presentation. RAW264.7 macrophages were infected with F. novicida for 4 h, stimulated with [100 U ml−1] of IFNγ for either 4 or 12 h and flow cytometry was used to detect the amount of surface expression of MHC class II molecules on the macrophages. No significant difference in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) between infected and uninfected cells was seen at 4 h, but a drop of nearly 50% in MFI was observed after 12 h in RAW macrophages infected with F. novicida (Fig. 7). These results suggest that F. novicida-infected macrophages express less MHC class II molecules on their surface after 12 h compared with uninfected macrophages.

Fig. 7.

Quantification of MHC II expression on the surface of Francisella novicida-infected RAW264.7 macrophages using flow cytometry. RAW264.7 macrophages were infected with F. novicida for 4 h and then stimulated with [100 U ml−1] IFNγ for either 4- or 12-h intervals. Following stimulation, RAW264.7 macrophages were stained with anti-MHC II conjugated to PE and surface expression of MHC II was quantified using flow cytometry. Histograms of MHC II expression 4 (A) and 12 (B) h after IFNγ stimulation and graphs of the MFIs 4 (C) and 12 (D)-h post-stimulation are shown. Data show the mean (±SEM) from two independent experiments.

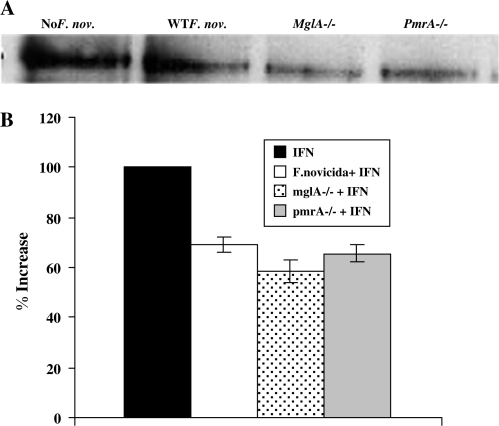

Expression of IFNγRα in macrophages following infection with F. novicida mglA and pmrA mutants

In order to determine which F. novicida genes are involved in down-regulation of STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling, we obtained two mutant strains of F. novicida, which lack transcriptional regulators that independently control Francisella pathogenicity island (FPI) gene expression. Macrophages were infected for 4 h with WT F. novicida or mglA-/- or pmrA F. novicida mutants and subsequently stimulated for 15 min with [100 U ml1] IFNγ. Cytoplasmic extracts were collected and used for western blotting with anti-IFNγRα. When compared with uninfected controls that were stimulated with IFNγ alone, RAW264.7 macrophages infected with WT F. novicida and both mutant strains showed a similar decrease in IFNγRα expression (Fig. 8). These results indicate that FPI genes regulated by either MglA or PmrA are not responsible for down-regulating IFNγRα expression as receptor expression was not restored in their absence.

Fig. 8.

Effect of mglA−/− and pmrA−/− Francisella novicida mutant infection on expression of IFNγRα on RAW264.7 macrophages. RAW267.4 macrophages were infected for 4 h with WT F. novicida, mglA−/− F. novicida or pmrA−/− F. novicida at 25:1 bacteria per macrophage. Cells were stimulated with [100 U ml−1] IFNγ for 15 min. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed for IFNγRα (A) expression by western blot. The blots shown represent one of two experiments with similar results. (B) Densitometry analysis was plotted as percentage increase in IFNγRα expression relative to control cells (the percentage increase in expression in control cells is taken as 100) when stimulated with IFNγ. Data shown in the graphs are combined from three independent experiments and shown as mean percentage increase (±SEM).

Discussion

The results of this investigation demonstrate that STAT1−/− mice are more susceptible to aerosolized F. novicida infection than WT BALB/c controls, which is likely related to the inability of STAT1−/− mice to control bacterial growth and pathology in their organs. We have also shown that Francisella interferes with STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling in macrophages by specifically down-regulating IFNγRα expression and ultimately decreasing MHC class II surface expression. Moreover, we have demonstrated for the first time that antigen-specific CD4+ T cells produce less IL-2 when stimulated by F. novicida-infected BMDM.

Several previous in vivo studies of F. tularensis infection have shown the importance of IFNγ signaling. Increased susceptibility to intra-dermal LVS infection has been observed in mice, which lack the IFNγ gene or have been treated with neutralizing antibodies for IFNγ (7, 8). Moreover, rIFNγ stimulation of alveolar macrophages has been shown to inhibit LVS growth and increase antimicrobial activity in vitro, which suggests that this signaling pathway might also be important during aerosol infection (10). Our findings support this by showing that STAT1−/− mice are more susceptible to aerosol F. novicida infection than WT mice and develop greater organ burdens and pathology. Our in vitro data show that F. novicida disrupts STAT1-dependent IFNγ in macrophages, but does not completely inhibit STAT1 activity, which could explain why STAT−/− mice that lack this signaling pathway are even more susceptible than WT mice. Based on these data, we conclude that STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling is necessary for the immune response to primary F. novicida aerosol infections, but is not sufficient to prevent mortality.

Many intracellular pathogens target the STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling pathway in macrophages in order to avoid host immune responses and prevent antigen presentation. Mycobacterium avium has been shown to inhibit IFNγ-inducible gene expression in macrophages by down-regulating both subunits of the IFNγR (3). Moreover, both Leishmania donovani and Leishmania mexicana have been shown to disrupt STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling (16–18). In fact, L. donovani-infected monocytes exhibited reduced MHC class II protein expression and tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1 (16, 17). Our results show that F. novicida interferes with this signaling cascade by specifically reducing expression of the ligand-binding portion or α-subunit of the IFNγR. We conclude that this reduction of IFNγRα expression in macrophages hinders downstream signaling and gene expression as we also found decreased STAT1 phosphorylation and STAT1 binding to GAS in DNA. These findings suggest that reduced IFNγRα expression in macrophages decrease MHC class II antigen presentation, which results in insufficient CD4+ T cell response to primary F. novicida infection.

IL-2 production by activated CD4+ T cells in response to MHC class II-presented antigen is required for proliferation and development of an adaptive immune response to infection. Our results indicate that F. novicida infection of macrophages decreases surface expression of MHC class II molecules and ultimately leads to reduced antigen-specific CD4+ T cell response. Other intracellular pathogens, like Mycobacterium bovis BCG, have been shown to interfere with MHC class II expression and antigen processing in IFNγ-activated alveolar macrophages (19). Similarly, M. avium has also been shown to decrease expression of IFNγ-inducible genes, including MHC class II gene Eβ and CIITA (3). This is the first time that Francisella sp. have been shown to interfere with MHC class II expression and diminished antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses following primary infection.

Although we have shown down-regulation of IFNγRα expression following F. novicida infection to be a major cause for the attenuation of STAT1-dependent IFNγ signaling, it is possible that increased expression of phosphatases, like the SOCS, could also contribute to decreased phosphorylation. In fact, another intracellular pathogen, Listeria monocytogenes, has been shown to disrupt STAT-mediated signaling in macrophages by inducing SOCS3 expression (20). Here, we have shown that F. novicida infection does not increase SOCS3 expression using western blotting. Therefore, we conclude that the decreased STAT1 phosphorylation and DNA binding observed after F. novicida infection is due entirely to decreased expression of IFNγRα and not to increased SOCS3 phosphatase activity.

One question that remains is how F. novicida disrupts the IFNγ signaling pathway in macrophages. MglA is the global transcriptional regulator of FPI genes, which has been shown to encode proteins necessary for type IV secretion system components, virulence and intramacrophage survival (21–23). In addition, an orphan response regulator of FPI genes, designated PmrA, has been identified and F. novicida pmrA mutants are defective in intramacrophage growth (24). Therefore, we investigated the role of FPI proteins in disruption of IFNγ signaling in macrophages using both mglA and pmrA F. novicida mutants. Western blot experiments for IFNγRα in both F. novicida mutants show decreases in IFNγRα expression similar to WT F. novicida, which suggests that down-regulation of this receptor subunit is not controlled by FPI proteins regulated by either MglA or PmrA. However, our results with these mutants do not rule out the possibility that downstream effects such as STAT1 phosphorylation or STAT1–DNA binding are occurring normally. In addition, further study will be required to elucidate the proteins responsible for this signaling cascade disruption and is currently underway in our laboratory.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that STAT1−/− mice are more susceptible to primary aerosol F. novicida infection than WT BALB/c mice. We have shown in vitro that F. novicida disrupts STAT1-mediated IFNγ signaling in macrophages, decreases surface expression of MHC class II molecules and reduces proliferation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. We have demonstrated that F. novicida-infected RAW264.7 macrophages down-regulate IFNγRα expression, which ultimately reduces expression of downstream proteins like MHC class II molecules. Together, these findings demonstrate that STAT1-mediated signaling participates in the host defense against pulmonary F. novicida infection but is not sufficient to prevent mortality associated with this infection. Moreover, our results show that F. novicida attenuates STAT1-mediated IFNγ signaling in macrophages and impairs their ability to activate antigen-specific CD4+ T cells.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Allergy and Infections Diseases (NIAID) Regional Center of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (RCE) Program. We acknowledge membership in and support from the Region V ‘great Lakes’ RCE (NIH award 1-U54-AI-057153); NIH/University of Minnesota PRCE Research Grant and Tzagournis Medical Research Fund (to A.R.S.).

Acknowledgments

We thank John Gunn Laboratory for generously providing the F. novicida strains used in these studies, as well as Nrusingh Mohapatra for sharing his technical expertise. We would also like to thank Bill Lafuse and Fatoumata Sow for technical help with the EMSAs and Joseph Barbi for his expert advice regarding flow cytometry experiments. The authors would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Nicole Achkar and Nicole Stauffer for technical assistance and animal care.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- CIITA

class II transcriptional activator

- CFU

colony-forming unit

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- FPI

Francisella pathogenicity island

- GAS

γ activation sequences

- IFNγR

IFNγ receptor

- ITAMs

immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs

- JAK

Janus kinase

- LVS

live vaccine strain

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NO

nitric oxide

- OVA

ovalbumin

- STAT1

signal transducer and activator of transcription-1

- SOCS

suppressors of cytokine signaling

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- WT

wild type

References

- 1.Decker T, Stockinger S, Karaghiosoff M, Muller M, Kovarik P. IFNs and STATs in innate immunity to microorganisms. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:1271. doi: 10.1172/JCI15770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decker T, Kovarik P, Meinke A. Gas elements: a few nucleotides with a major impact on cytokine-induced gene expression. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 1997;17:121. doi: 10.1089/jir.1997.17.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussain S, Zwilling BS, Lafuse WP. Mycobacterium avium infection of mouse macrophages inhibits IFN-γ Janus kinase-STAT signaling and gene induction by down-regulation of the IFN-γ receptor. J. Immunol. 1999;163:2041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dennis DT, Inglesby DA, Henderson JG, et al. Tularemia as a biological weapon-medical and public health management. JAMA. 2001;285:2763. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlan JW, KuoLee R, Shen H, Webb A. Different host defences are required to protect mice from primary systemic vs. pulmonary infection with the facultative intracellular bacterial pathogen, Francisella tularensis LVS. Microb. Pathog. 2002;32:127–134. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2001.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen H, Chen W, Conlan JW. Susceptibility of various mouse strains to systemically- or aerosol-initiated tularemia by virulent type A Francisella tularensis before and after immunization with the attenuated live vaccine strain of the pathogen. Vaccine. 2003;22:2116. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkins KL, Rhinehart-Jones TR, Culkin SJ, Yee D, Winegar RK. Minimal requirements for murine resistance to infection with Francisella tularensis LVS. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:3288. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3288-3293.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leiby DA, Fortier AH, Crawford RM, Schreiber RD, Nacy CA. In vivo modulation of the murine immune response to Francisella tularensis LVS by administration of anticytokine antibodies. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:84. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.84-89.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortier AH, Polsinelli T, Green SJ, Nacy CA. Activation of macrophages for destruction of Francisella tularensis; identification of cytokines, effector cells and effector molecules. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:817. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.817-825.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polsinelli T, Meltzer MS, Fortier AH. Nitric oxide-independent killing of Francisella tularensis by IFN-γ-stimulated murine alveolar macrophages. J. Immunol. 1994;153:1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duckett NS, Olmos S, Durrant DM, Metzger DW. Intranasal interleukin-12 treatment for protection against respiratory infection with the Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:2306. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2306-2311.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolard MD, Wilson JE, Hensley LL, et al. Francisella tularensis-infected macrophages release prostaglandin E2 that blocks T cell proliferation and promotes a Th2-like response. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2065. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck SE, Laube BL, Barberena CI, et al. Deposition and expression of aerosolized rAAV vectors in the lungs of Rhesus macaques. Mol. Ther. 2002;6:546. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horvath CM, Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr A STAT protein domain that determines DNA sequence recognition suggests a novel DNA-binding domain. Genes Dev. 1995;9:984. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai X-H, Golovliov I, Sjostedt A. Francisella tularensis induces cytopathogenicity and apoptosis in murine macrophages via a mechanism that requires intracellular bacterial multiplication. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:4691. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4691-4694.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwain WC, McMaster WR, Wong N, Reiner NE. Inhibition of expression of major histocompatibility complex II molecules in macrophages infected with Leishmania donovani occurs at the level of gene transcription via a cyclic AMP-independent mechanism. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:2115. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.2115-2120.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nanadan D, Reiner NE. Attenuation of γ interferon-induced tyrosine phosphorylation in mononuclear phagocytes infected with Leishmania donovani: selective inhibition of signaling through Janus kinases and Stat1. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:4495. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4495-4500.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhardwaj N, Rosas LE, Lafuse WP, Satoskar AR. Leishmania inhibits STAT1-mediated IFN-γ signaling in macrophages: increased tyrosine phosphorylation of dominant negative STAT1β by Leishmania mexicana. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005;35:75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fulton SA, Reba SM, Pai RK, et al. Inhibition of major histocompatibility complex II expression and antigen processing in murine alveolar macrophages by Mycobacterium bovis BCG and the 19-kilodalton mycobacterial lipoprotein. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:2101. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2101-2110.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoiber D, Stockinger S, Steinlein P, Kovarik J, Decker T. Listeria monocytogenes modulates macrophage cytokine responses through STAT serine phosphorylation and the induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J. Immunol. 2001;166:466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nano FE, Zhang N, Cowley SC, et al. A Francisella tularensis pathogenicity island required for intramacrophage growth. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:6430. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.19.6430-6436.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Bruin OM, Ludu JS, Nano FE. The Francisella pathogenicity island protein IglA localizes to the bacterial cytoplasm and is needed for intracellular growth. BMC Microbiol. 2007;17:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brotcke A, Weiss DS, Kim CC, et al. Identification of MglA-regulated genes reveals novel virulence factors in F. tularensis. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:6642. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01250-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohapatra NP, Soni S, Bell BL, et al. Identification of an orphan response regulator required for the virulence of Francisella spp. and transcription of pathogenicity island genes. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:3305. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00351-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]