Abstract

Background

Barbershops constitute potential sites for community health promotion programs targeting hypertension (HTN) in African American men but such programs previously have not been formally evaluated.

Methods

A randomized trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00325533) will test whether a continuous HTN detection and medical referral program conducted by influential peers (barbers) in a receptive community setting (barbershops) can promote treatment-seeking behavior and thus lower blood pressure (BP) among the regular customers with HTN. Barbers will offer a BP check with each haircut and encourage appropriate medical referral using real stories of other customers modeling the desired behaviors. A cohort of 16 barbershops will go through a pre-test/post-test group-randomization protocol. Serial cross-sectional data collection periods (10 weeks each) will be conducted by interviewers to obtain accurate snap-shots of HTN control in each barbershop before and after 10 months of either barber-based intervention or no active intervention. The primary outcome is BP control: BP <135/85 mm Hg (non-diabetics) and <130/80 mm Hg (diabetics) measured in the barbershop during the 2 data collection periods. The multilevel analysis plan utilizes hierarchical models to assess the effect of covariates on HTN control and secondary outcomes while accounting for clustering of observations within barbershops.

Conclusions

By linking community health promotion to the healthcare system, this program could serve as a new model for HTN control and cardiovascular risk reduction in African American men on a nationwide scale.

Keywords: Population science, special populations, blood pressure measurement/monitoring, African Americans, hypertension

Hypertension (HTN) is more prevalent, more severe, and causes more disability and death from myocardial infarction, stroke, and end-stage renal disease in African Americans than all other racial/ethnic groups in the United States, particularly before age 65.1–3 Despite some recent improvement, HTN control rates remain lower in African Americans than in the general population, with recommended blood pressure (BP) treatment goals being achieved in less than one-third of the ~15 million African Americans with HTN.1,2

Compared with African American women, men have less frequent contact with the healthcare system and thus lower rates of HTN detection, treatment, and control.2,4–8 Despite comparable levels of healthcare access, hypertensive men are less likely than women to perceive the need for a regular physician—a prerequisite for early diagnosis and effective medical treatment of HTN.8 Thus, novel HTN outreach programs are needed to better convey preventive cardiology messages to large segments of the at-risk male population who have not engaged the healthcare system.8–12

Previous HTN screening and medical referral programs targeting African American men have utilized sporting events and barbershops.13,14 The African American-owned barbershop holds particular appeal as a cultural institution that draws a loyal male clientele and provides an open forum for discussion of any number of topics—including health—with influential peers.13,15–17 Despite such appealing features, these HTN outreach programs never have been formally evaluated.

In 2 non-randomized feasibility trials, we recently found that an enhanced intervention program of continuous blood pressure (BP) monitoring and peer-based health messaging in a barbershop can (1) increase medical referrals and lower BP more than standard screening and health education, and (2) be implemented by barbers rather than research personnel.10 Based on these encouraging feasibility data, we subsequently designed a group randomized trial. This report describes the novel community-based intervention administered by barbers and the rigorous study design that will be used to formally evaluate its effectiveness.

Study objectives

The study is designed to critically evaluate the effectiveness of a barber-based intervention for HTN utilizing state-of-the-art clinical trial methodology. The primary objective is to test whether HTN control rates will increase more in barbershops randomized to an enhanced HTN detection, referral, and follow-up program administered by barbers than in barbershops randomized to standard HTN screening and health education. An additional objective is to test for an intervention effect on the customers’ healthcare-seeking attitudes and behaviors leading to HTN control.

Study Sites

Study sites will be 16 African American-owned barbershops located in Dallas County, Texas. All barbershops will have been in business for 10 or more years (to ensure stability) and will have a large African American male clientele (to permit stable estimates of HTN control).

Study Participants

All participants will be African American men, 18 years of age or older, who patronize any participating barbershop. The study has been approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both UT Southwestern and the Temple University Institute for Survey Research, which will conduct the field interviews.

Study Design

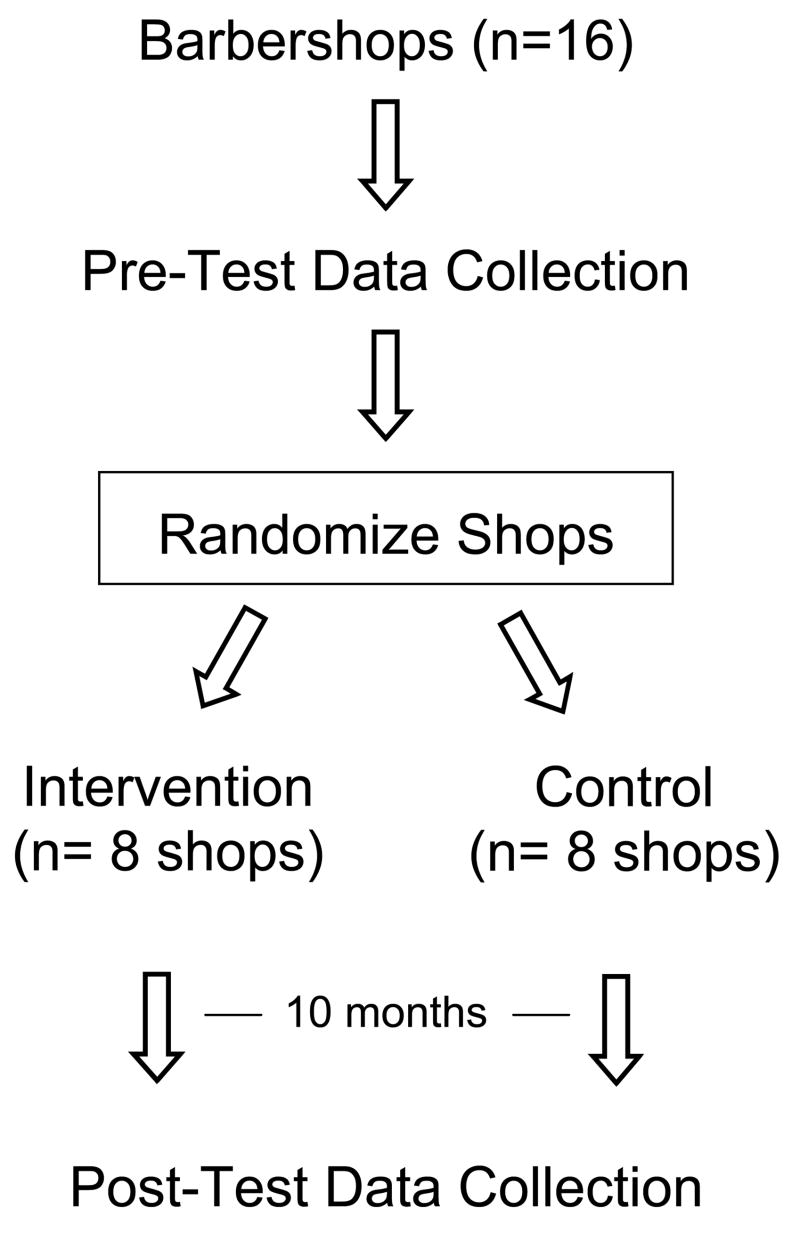

The study design is depicted in Figure 1. A cohort of 16 previously unstudied barbershops will go through a pre-test/post-test group-randomization protocol. Serial cross-sectional data collection periods (each lasting 10 weeks) will be conducted by trained African American field interviewers to obtain accurate snap-shots of HTN control in each of the 16 barbershops before and after 10 months of either barber-based intervention (n=8 shops) or a contemporaneous inactive control period (n=8 shops).

Figure 1.

Overall study design.

During each data collection period, interviewers will screen all adult male customers in each barbershop for HTN. Men meeting preset screening criteria will receive an incentive for returning on a separate day to complete a second set of BP measurements, a computer-assisted health questionnaire, and a detailed prescription medication list.

With this design, the barbershop (not the individual customer) is the unit of randomization. Shops will be enrolled in blocks of 4, stratified by their baseline HTN control rates, and then randomly allocated to either intervention or control conditions for a balanced design.

Group randomization is necessitated by the infeasibility of isolating the intervention to specific customers within the barbershop as well as the expectation that barbershop customers selected from the same barbershop will be more similar than customers selected at random.18–21 The group randomization design also neatly handles attrition and addition of customers during the trial, unavoidable complications of cohort designs.

Barber-Based Intervention

Conceptual Model

The intervention is informed by a prior community-level needs assessment, which was recently published.8,22 Despite comparable levels of healthcare access and perceived healthcare discrimination among hypertensive African American men and women in Dallas County, we found that men were far less likely to perceive a need for on-going healthcare with a regular physician.8 Even among those who have been engaged in the healthcare system, hypertensive men often may not realize that continued BP monitoring and adjustment in medication are needed to reduce the health risks associated with HTN. Accordingly, we developed a behavior theory-based intervention conducted by barbers—influential peers who will continually monitor their customers’ BP, facilitate medical referral, and deliver health messages designed to personalize the risk associated with elevated BP and make risk reduction socially desirable.

The theoretical underpinning is adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s AIDS Community Demonstration Projects—a rare example of a community-level health promotion program that achieved positive measurable outcomes.23,24 Here we incorporated the following elements of that program into our behavioral model of cardiovascular risk reduction from HTN: (1) in-depth assessment of the needs of the target population to sharply define specific behavioral objectives, (2) focus on making risk avoidance socially desirable, (3) mobilization of trusted community peers to administer the intervention, (4) utilization of peer-experience (role model) stories as the primary medium for health messaging, and (5) provision of medical equipment in daily life.23,25,26

Protocol for the Intervention Barbershops

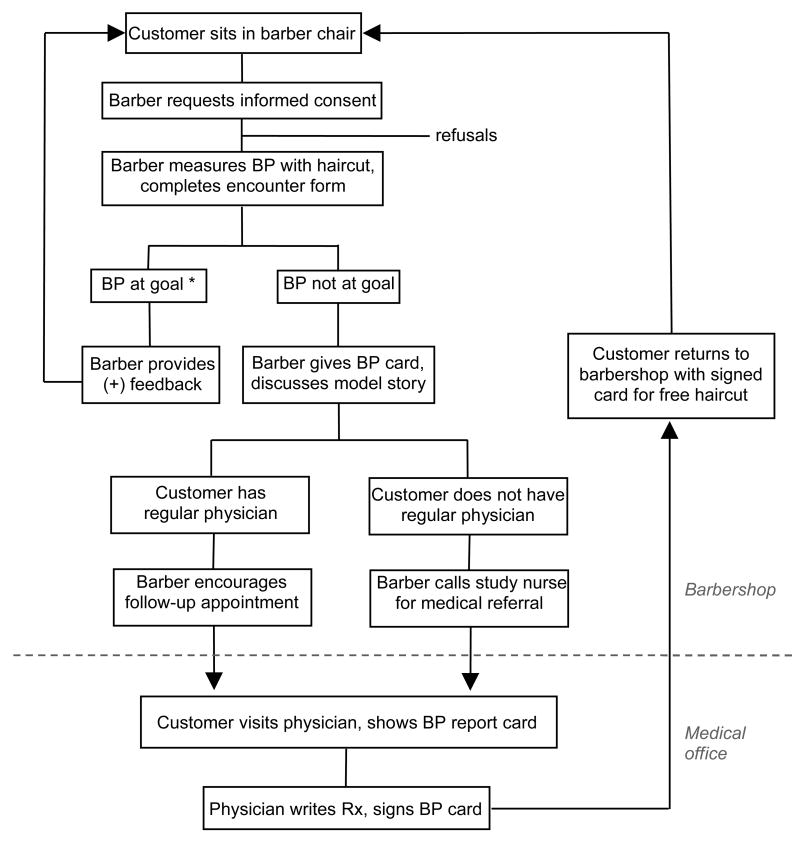

Barbers will be trained, equipped, and paid to conduct the intervention protocol depicted in Figure 2. All of their adult African American male customers will be eligible to participate in this continuous on-site BP monitoring and medical referral program. Barbers will be taught to offer a BP check with each haircut, to measure and interpret BP, to complete written encounter forms, and to discuss role model stories—real stories of other male customers modeling the desired changes in health behavior.10,23

Figure 2. Overview of barber-based intervention protocol.

BP, blood pressure; Rx, prescription for antihypertensive medication

* BP at goal is defined as < 135/85 mmHg (for non-diabetics) and < 130/80 mmHg (for diabetics).

The role model stories will constitute pivotal intervention tools and will be prominently displayed as large posters in the barbershops. They will depict 1 of 4 desired health behaviors: (1) participating in the BP monitoring program, (2) seeking a regular physician for untreated HTN, (3) seeking follow-up with an established physician for inadequately treated HTN, and (4) medication adherence.

These stories are meant to model the process of adopting one of these new behaviors. This process typically involves several steps: recognizing personal risk, considering the behavior change, overcoming barriers to adopting it, receiving social support for initial attempts at the new behavior, successfully adopting the behavior described, and maintaining the behavior change.23 The stories will come from interviews of fellow customers of a given barbershop; in the context of this study, each barbershop is considered as its own community. Each story will model (1) one specific behavior, (2) a barrier to change, (3) the principal perceptual factor(s) that facilitated the change, and (4) a positive outcome. According to the behavior theory,23,25,26 facilitating factors include perceived personal health risks, social norms, social support, self-efficacy, and environmental facilitators (i.e., a BP monitor at each barber station).

In addition to the model stories, the other principal intervention tools will be wallet-size BP report cards by which the barbers provide their hypertensive customers (and the physicians) with on-going feedback—accurate out-of-office BP readings—about the need to initiate or intensify antihypertensive medication.10

If a customer with elevated BP has a regular physician, the barber will refer him back to his established physician. If a customer with elevated BP does not have a regular physician, the barber will call the study nurse to make a medical referral appropriate to the customer’s health insurance. Uninsured customers will be referred to community health centers or providers that offer discounted rates to uninsured patients.

The study will not provide free medical care or free transportation. However, hypertensive subjects will be provided a free haircut (~$12/each) for each valid BP report card signed by their physician and returned to their barber. Financial incentives to the barbers will be as follows: $3/recorded BP, $10/phone call in which the barber enables a customer with elevated BP to speak directly with the study nurse about medical referral before leaving the barbershop, and $50/BP report card signed by a physician and returned to the barber.

Protocol for the Control Barbershops

Prior to randomization, in all 16 barbershops the 10-week pre-test data collection process itself will constitute a form of intervention—HTN screening that is more prolonged than a standard community screening event. Each time a customer enters one of the participating barbershops during the 10-week period, he will be exposed to field interviewers who will be measuring BP and interviewing subjects about HTN. Furthermore, hypertensive customers will be given written documentation of their BP readings, with interpretation and standard recommendations for medical follow-up; this information will be provided twice to each subject who completes all phases of baseline data collection.

After randomization, shops in the control arm will be provided with a continual supply of the American Heart Association brochure on High Blood Pressure in African Americans (product code 50–1466).

Study Measures

BP measurement

All BPs will be measured in the barbershops with a validated electronic oscillometric monitor (Welch Allyn, Series #52,000, Arden, N.C.)27 using an appropriately-sized arm cuff with the participant seated comfortably in a barber chair. During the 10-week data collection periods, the field interviewers will try to obtain 2 sets of BP measurements on separate days on each hypertensive male customer. Each time they will measure 6 consecutive readings after 5 minutes of rest; the last 5 readings will be averaged to obtain a mean value, which will be used in calculation of the primary outcome.

During the intervention, the participating barbers will measure 3 consecutive readings toward the end of a haircut and enter the 3rd reading on an encounter form as process data.

Survey Instrument

During each 10-week data collection period, the field interviewers will administer a structured computer-assisted face-to-face health interview in 2 parts. The first part, a brief screening module, will be administered to all adult male patrons to identify potential hypertensive subjects. The second part, a more comprehensive health interview, will be administered to those who are hypertensive at screening. This ~15 minute interview will provide detailed information on each hypertensive participant about numerous factors that might influence HTN awareness, treatment, and control. These will include demographic characteristics, barbershop patronage, health care access and utilization, medical history, HTN knowledge, family history, smoking history, alcohol use, stages of change related to key behavioral outcomes, perceived discrimination in the healthcare setting, and perceived health. The instrument will be adapted from that used in the Dallas Heart Study22 with modifications informed by pilot data.10 The instrument will include validated scales to assess medication adherence, health-related quality of life, and perceived stress.23,28–30 It also will include comprehensive medication lists—with detailed information about medication type, dosage and frequency—compiled by direct inspection of prescription drug labels rather than relying on self-report. Subjects who are hypertensive at screening will be asked to bring all their prescription pill bottles to the field interviewers during their next visit to the barbershop.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome will be the change in HTN control rate. Using the currently recommended cutoff values for out-of-office BP,31 HTN will be defined as having a current prescription for antihypertensive medication or having a measured BP ≥ 135/85 mmHg (BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg for men with diabetes) on 2 separate days. At each end of the study, the HTN control rate will be calculated for each barbershop as the percentage of hypertensive customers with BP < 135/85 mm Hg (BP < 130/80 mmHg for those with diabetes).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes will include HTN treatment rates, and systolic and diastolic BP. The behavioral assessments of health care utilization, stages of change related to healthcare seeking, medication adherence, knowledge about BP, and health perceptions will also be considered secondary outcomes.

Statistical Considerations

Sample Size and Power

The primary observation in each barbershop is the difference between pre-test and post-test HTN control rates. This quantity will be comprised of a fixed intervention effect and a random effect. Estimates of the detectable intervention effect follow from assigning variance values to the random effect.

The random effect has two components, 1) the joint effect of barbershop and time, and, 2) the average effect of customers within a barbershop. The variance of the joint effect of barbershop and time is , where is the barbershop component of variance estimated from a pilot study10, and ρb is the repeat-measure correlation of barbershops. The variance of the average effect of customers within a barbershop is 2μ(1−μ)/m, where μ and m are the HTN control rate and number of hypertensive customers of the barbershop, respectively. Based on data from a large epidemiological study in Dallas (Dallas Heart Study) 22, the HTN control rate at baseline is expected in the range 15–20%. The intervention is expected to raise this 10–15%. A conservative value of μ, for the purpose of estimating detectable differences, is therefore 35%.

Table I shows the intervention effect detectable with 80% power and two-tailed 5% significance level for a range of barbershop repeat-measure correlations from 0 to 0.5. The study was designed for 8 shops per arm with the aim of enrolling additional shops permitted by the availability of funding to account for attrition of study sites.

Table I.

Minimum Detectable Improvements in HTN Control Rate

| over-time correlation* | 8 barbershops per study-arm | 12 barbershops per study-arm |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15.5% | 12.3% |

| 0.1 | 15.0% | 11.9% |

| 0.2 | 14.6% | 11.6% |

| 0.3 | 14.1% | 11.2% |

| 0.4 | 13.6% | 10.8% |

| 0.5 | 13.1% | 10.4% |

Percentages are mean differences in HTN control rates between intervention and control barbershops in an experimentally controlled nested cross-sectional design. Calculations assume 100 hypertensive customers per barbershop, 80% power, and 2-sided 5% significance level.

Over-time correlation refers to repeat-measure correlation of HTN control rate in a given barbershop

Analysis Plan

Primary Analysis

The primary hypothesis is that HTN control rates will increase more in the intervention barbershops than in the control barbershops. The pretest-posttest control group design will allow us to calculate the change in HTN control rate for each barbershop in the study. We will compare intervention barbershops to control barbershops on changes in HTN control rates using a t test at a 2-sided, 5% significance level. Specifically, we will test the effect of study-arm × time in a general linear model of HTN control rate. At the barbershop level, the HTN control rate, being a mean value, will be approximately normally distributed and will be treated as a continuous outcome.

The primary analysis will include all customers who participate in either the pre-test or post-test data collections. In the primary intention-to-treat analysis, customers will be assigned to the barbershop in which they complete the pre-test data collection.

Some subjects may patronize barbershops in both study arms but we anticipate that the number of such subjects will be negligible. Our feasibility studies predict that < 10% of the customers will patronize more than one barbershop. The number of study sites in either arm will be small (< 5%) compared to the total number of African American-owned barbershops in Dallas County, thus reducing the probability that a customer of a control barbershop also will be a customer of an active barbershop. The few subjects who patronize more than one study barbershop will not be excluded from the primary analysis in accordance with intention-to-treat. However, such subjects will be removed from secondary cohort-level analyses described below.

Secondary Analyses

While the primary analysis will be performed at the level of barbershops, a secondary analysis of the primary hypothesis will be performed at the customer level to allow adjustment for customer intervention exposure along with other covariates such as age, body mass index, diabetes, family history of HTN, healthcare access, smoking habits, and baseline perceived need of a regular physician. Intervention exposure for each customer will be calculated as the percentage of total haircuts accompanied by a BP measurement. The adjusted model will account for the hierarchical nesting of barbershops within recruitment blocks and customers within barbershops imposed by the study design. Specifically, we will test the effect of study-arm × time in a generalized linear model of HTN control rate with fixed effects of study-arm, time, and study-arm × time and random effects of recruitment blocks and barbershops within recruitment blocks. At the customer level, HTN control will be treated as a dichotomous outcome. Capability for generalized linear mixed modeling is provided by the SAS GLIMMIX procedure.

Intervention effects on unadjusted HTN treatment rates, and mean systolic and diastolic BPs will be tested using general linear models, treating both outcomes as continuous at the barbershop level. The adjusted analyses must be performed at the customer level, using a generalized linear mixed model of HTN treatment and linear mixed models of systolic and diastolic BP, adjusting for the same fixed effects as in the analysis of HTN control. Capability for linear mixed modeling is provided by the SAS MIXED procedure.

The significance of intervention exposure on the primary and secondary outcomes will be evident from the adjusted models. However, the extent to which successful implementation of the intervention is concentrated among specific barbers will not. To explore this possibility, we will rank barbers by improvement in the HTN control rates of their customers and see whether this ranking corresponds with their degree of participation in the intervention. Barber participation will be measured by completed encounter forms collected during the intervention and normalized to the size of their clientele as determined from the pre-test and post-test data collections. We will use a Jonckheere-Terpstra test32 to determine the significance of the doubly-ordered trend.

Summary statistics will be used to examine behavioral outcomes. Formal analyses and hypothesis tests in support of these summaries will be conducted as necessary.

Finally, we will analyze the primary outcome on the cohort of regular customers who were present for both the pre-test and 10 month follow-up post-test data collections. Men patronizing more than one barbershop will be excluded from this analysis. This restricted analysis also will be performed within a generalized linear model of HTN control, but an additional random effect of recruitment block × barbershop × customer must be included to account for the repeated measure of customers within barbershops within recruitment blocks. Fixed effects will include study-arm, time, study-arm × time, and, for adjusted analyses, customer intervention exposure, age, body mass index, diabetes, family history of HTN, healthcare access, smoking habits, and baseline perceived need of a regular physician.

DISCUSSION

This study will address an important health disparity—excessive and premature cardiovascular disability and death among African American men from undetected, untreated, or under-treated HTN.3,8 Yet, few previous health promotion trials have specifically addressed HTN control in African American men.33–35 Our study is responsive both to the 2nd goal of Healthy People 2010 (to eliminate health disparities related to race or ethnicity) and to the NIH program announcement on Health Promotion Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Males (PA-03-170). The pre-test data alone should provide additional information about factors associated with healthcare utilization and HTN control among a large community-based sample of African American men.

The study has several innovative features. First, the intervention program will enable barbers to become health educators and help combat the epidemic of HTN and cardiovascular disease in their community. Barbers are uniquely positioned to administer the intervention because they are trusted, influential peers whose historical predecessors were barber-surgeons. 9,10,17,36 More broadly, this novel approach will shift more of the responsibility for HTN control to the lay community and it will link community health promotion to the healthcare system. Second, the conceptual model is behavior-theory based; this model has proven effective in avoidance of HIV infection but previously has not been tested for control of HTN or other cardiovascular risk factors.23 Third, previous health promotion trials have randomized medical clinics, hospitals, schools, and worksites.24 However, we know of no such trials that ever randomized barbershops. The rigorous group randomization design is critically important to evaluate the effectiveness of this attractive, but as yet unproven, intervention program.

The study also has potential limitations. First, pre- and post-test data collections will be subject to non-participation bias, which will be minimized by an effective incentive—free haircuts. Accurate measurements of total shop business will be used to estimate the effect of residual non-participation on the primary and secondary outcome variables. Second, barbers may vary in the degree to which they administer the intervention. Thus, the study will provide financial incentives to barbers and account for intervention implementation and exposure in secondary analyses. Third, the intervention will focus on the customers and not on their physicians. Our premise is that increasing customer demand for better blood pressure will have a positive impact on physician prescribing behavior.

If encouraging findings of recent non-randomized feasibility studies10 are replicated in the group randomized trial, this innovative bio-behavioral approach could serve as a new model to help manage other cardiovascular risk factors and other chronic diseases that disproportionately affect African American men. The potential public health impact of this community-based research is high, with thousands of African American-owned barbershops nationwide.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

This work is funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (RO-1 HL080582), the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, unrestricted educational grants from Pfizer, Inc., and Biovale, Inc., and the Aetna Foundation Regional Health Disparity Program. The sponsors were not involved in the design and conduct of the studies, the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data, and played no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Douglas JG, Bakris GL, Epstein M, et al. Management of high blood pressure in African Americans: consensus statement of the Hypertension in African Americans Working Group of the International Society on Hypertension in Blacks. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(5):525–541. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hertz RP, Unger AN, Cornell JA, et al. Racial disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, and management. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(18):2098–2104. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.18.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2006 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113(6):e85–151. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.171600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN. Characteristics of patients with uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(7):479–486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotchen JM, Shakoor-Abdullah B, Walker WE, et al. Hypertension control and access to medical care in the inner city. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(11):1696–1699. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.11.1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieto FJ, Alonso J, Chambless LE, et al. Population awareness and control of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(7):677–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavlik VN, Hyman DJ, Vallbona C, et al. Hypertension awareness and control in an inner-city African-American sample. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11(5):277–283. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Victor RG, Leonard D, Hess PL, et al. Factors Associated with Hypertension Awareness, Treatment, and Control in Dallas County, Texas. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1285–1293. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferdinand KC. Lessons learned from the Healthy Heart Community Prevention Project in reaching the African American population. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1997;8(3):366–371. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess PL, Reingold JS, Jones J, et al. Barbershops as hypertension detection, referral, and follow-up centers for black men. Hypertension. 2007;49(5):1040–1046. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.080432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madigan ME, Smith-Wheelock L, Krein SL. Healthy hair starts with a healthy body: hair stylists as lay health advisors to prevent chronic kidney disease. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(3):A64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaya FT, Gu A, Saunders E. Addressing cardiovascular disparities through community interventions. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):138–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong BW. Community programs to increase hypertension control. J Natl Med Assoc. 1989;81(Suppl):13–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong BW. Community-based hypertension control programs that work. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1997;8(4):409–415. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferdinand KC. The Healthy Heart Community Prevention Project: a model for primary cardiovascular risk reduction in the African-American population. J Natl Med Assoc. 1995;87(8 Suppl):638–641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitka M. Efforts needed to foster participation of blacks in stroke studies. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1311–1312. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy M. Barbershop talk: The other side of black men. Merrifield; 1998.

- 18.Murray DM, Feldman HA, McGovern PG. Components of variance in a group-randomized trial analysed via a random-coefficients model: the Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (REACT) trial. Stat Methods Med Res. 2000;9(2):117–33. doi: 10.1177/096228020000900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray DM, Varnell SP, Blitstein JL. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials: a review of recent methodological developments. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):423–432. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray DM, Blitstein JL, Hannan PJ, et al. Sizing a trial to alter the trajectory of health behaviours: methods, parameter estimates, and their application. Stat Med. 2007;26(11):2297–2316. doi: 10.1002/sim.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens J, Murray DM, Catellier DJ, et al. Design of the Trial of Activity in Adolescent Girls (TAAG) Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26(2):223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, et al. The Dallas Heart Study: a population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(12):1473–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Community-level HIV intervention in 5 cities: final outcome data from the CDC AIDS Community Demonstration Projects. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(3):336–345. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merzel C, D’Afflitti J. Reconsidering community-based health promotion: promise, performance, and potential. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):557–74. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mittelmark MB, Hunt MK, Heath GW, et al. Realistic outcomes: lessons from community-based research and demonstration programs for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. J Public Health Policy. 1993;14(4):437–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones CR, Taylor K, Poston L, et al. Validation of the Welch Allyn ‘Vital Signs’ oscillometric blood pressure monitor. J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15(3):191–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, Jr, et al. Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(8):1003–1012. doi: 10.1023/a:1026179517081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mancia G, De BG, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 ESH-ESC Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: ESH-ESC Task Force on the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2007;25(9):1751–1762. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f0580f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SAS Online Documentation. [Accessed May 29, 2008];Jonckheere-Terpstra Test. Available at http://support.sas.com/onlinedoc/913/getDoc/en/statug.hlp/freq_sect25.htm.

- 33.Dennison CR, Post WS, Kim MT, et al. Underserved urban african american men: hypertension trial outcomes and mortality during 5 years. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20(2):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill MN, Bone LR, Hilton SC, et al. A clinical trial to improve high blood pressure care in young urban black men: recruitment, follow-up, and outcomes. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12(6):548–54. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill MN, Han HR, Dennison CR, et al. Hypertension care and control in underserved urban African American men: behavioral and physiologic outcomes at 36 months. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16(11 Pt 1):906–913. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)01034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobson J. Barber into surgeon. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1974;54(2):84–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]