Abstract

Motivation: High-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) is among the most widely used technologies in metabolomics. Metabolites participate in almost all cellular processes, but most metabolites still remain uncharacterized. Determination of the sum formula is a crucial step in the identification of an unknown metabolite, as it reduces its possible structures to a hopefully manageable set.

Results: We present a method for determining the sum formula of a metabolite solely from its mass and the natural distribution of its isotopes. Our input is a measured isotope pattern from a high resolution mass spectrometer, and we want to find those molecules that best match this pattern. Our method is computationally efficient, and results on experimental data are very promising: for orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometry, we correctly identify sum formulas for >90% of the molecules, ranging in mass up to 1000 Da.

Availability: SIRIUS is available under the LGPL license at http://bio.informatik.uni-jena.de/sirius/

Contact: anton.pervukhin@minet.uni-jena.de

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

High-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) allows determining the mass of sample molecules with very high accuracy (1–5 p.p.m.), and has become one preferred method of analyzing metabolites. The output of a mass spectrometer, after preprocessing, consists of peaks that ideally correspond to the masses of the sample molecules and their abundance. This brings into play the natural isotopic distributions of the elements: several peaks in the output correspond to the same type of sample molecule, reflecting its isotope pattern. In this article, we use this isotope pattern to identify the sample molecule by determining its molecular formula or sum formula, i.e. the number of atoms of each element.

The term “metabolite” is usually restricted to small molecules that are intermediates and products of the metabolism. These small molecules participate in almost all cellular processes such as signal transduction, stress response, catabolism, or anabolism. Today, databases mostly contain primary metabolites directly relevant for growth, development, and reproduction of a cell or an organism. In contrast, most of the metabolites not directly involved in the aforementioned functions are yet uncharacterized. The majority of known metabolites have mass <1000 Da: 96.5% of sum formulas in the KEGG COMPOUND database (Kanehisa et al., 2006) fall into this mass range. To identify a sample metabolite, its mass spectrum is compared to spectra in a reference database. This method is limited to identifying metabolites and chemical compounds that have been included in some reference mass spectra library. Hence, de novo interpretation of metabolite mass spectra is highly sought.

Our input is a list of masses M0,…,MK with intensities f0,…,fK, normalized such that ∑ifi =1. We extract this data from a high-resolution mass spectrum in a preprocessing step, and assume that it corresponds to the isotope pattern of a sample molecule. Note that for molecular mixtures, separating isotopic peaks that belong to different molecules is mostly trivial in this case. Our goal is to find the molecule, or rather its sum formula, whose isotope pattern best matches the input. In the following, we use ‘molecule’ and ‘sum formula’ interchangeably. We stress that this method cannot be used as-is to identify peptides or amino acid compositions, because certain sum formulas correspond to multiple peptides.

To resolve the sum formula, Kind and Fiehn (2006) suggest to proceed as follows: first, compute all sum formulas that share monoisotopic mass with the input mass spectrum. For every such candidate molecule, simulate its isotope pattern, and match and rank it against the input isotope pattern. Several experimental studies using this setup have been reported in the literature, the most prominent by Iijima et al. (2008) who claim to have discovered almost 500 novel metabolites in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Zhang et al. (2005) address a related problem for analyzing peptides, but this approach heavily builds on several ad hoc rules regarding admissible sum formulas and uses a heuristic search. Böcker and Rasche (2008) present a method for the automated interpretation of metabolite tandem mass spectra but ignore isotope patterns.

In this article, we present efficient algorithms for all steps of the analysis pipeline suggested above. We limit our presentation to the elements most abundant in living beings, but note that our methods also work for other sets of elements. We first show how to use integer decomposition techniques (Böcker and Lipták, 2007) for decomposing real-valued masses, with large improvements over naïve approaches. Second, we present a method for rapid computation of isotope distributions and mean masses of isotope peaks, improving on previously best known results (Rockwood et al., 2004). Fast simulation of isotope patterns is vital due to the large search space. Third, we show how to rapidly match and rank such simulated spectra against the measured spectrum. We then report on the application of our method to high-resolution mass spectra. Finally, we present the software tool SIRIUS (Sum formula Identification by Ranking Isotope patterns Using mass Spectrometry) that implements all of the above algorithms and combines them with an easy-to-use graphical user interface.

2 ISOTOPES AND ISOTOPE PATTERNS

The elements most abundant in living beings are hydrogen (H), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), phosphor (P) and sulfur (S). Atoms with the same number of protons but different number of neutrons are called isotopes of the element. Each of these isotopes occurs in nature with a certain abundance, and we limit our attention to these naturally occurring isotopes. The superscript preceding a symbol denotes the mass number of the atom: the number of protons plus the number of neutrons. The mass of an atom is measured in Dalton (Da). An atom's mass is roughly but not exactly equal to its mass number, the difference being due to the binding energy in the atom's nucleus. The masses of the different isotopes and their abundance are known up to very high precision (Audi et al., 2003) (see Table 1 for the six elements described above). Note that unlike their mass, natural abundances of isotopes are not physical constants. Values may slightly vary depending on, say, the continent where a sample was taken.

Table 1.

Natural isotopic distribution: relative abundance of isotopes and their masses in Dalton

| Element | Isotope | mass | Mass difference | Abundance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 1H | 1.007825 | 99.985 | |

| 2H | 2.014102 | +1.006277 | 0.015 | |

| Carbon | 12C | 12.0 | 98.890 | |

| 13C | 13.003355 | +1.003355 | 1.110 | |

| Nitrogen | 14N | 14.003074 | 99.634 | |

| 15N | 15.000109 | +0.997035 | 0.366 | |

| Oxygen | 16O | 15.994915 | 99.762 | |

| 17O | 16.999132 | +1.004217 | 0.038 | |

| 18O | 17.999161 | +2.004246 | 0.200 | |

| Phosphor | 31P | 30.973762 | 100 | |

| Sulfur | 32S | 31.972071 | 95.020 | |

| 33S | 32.971459 | +0.999388 | 0.750 | |

| 34S | 33.967867 | +1.995796 | 4.210 | |

| 36S | 35.967081 | +3.995010 | 0.020 |

The nominal mass (also called nucleon number) of a molecule is the sum of protons and neutrons of the constituting atoms. The mass of the molecule is the sum of masses of these atoms. Clearly, nominal mass and mass depend on the isotopes the molecule consists of, thus on the isotope species of the molecule. The isotope species where each atom is the isotope with the lowest nominal mass is called monoisotopic. Likewise, the mass of the monoisotopic species is called the monoisotopic mass of the molecule. Mass defects and, hence, differences from the ideal mass depend on the elemental composition of a molecule. For example, sucrose (C12H22O11) has monoisotopic mass 342.116215 Da; whereas, the short peptide Leu-Asn-Pro (C15H26N4O5) has monoisotopic mass 342.190321, while both molecules have monoisotopic nominal mass 342.

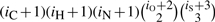

The number of distinct isotope species for a molecule with iH hydrogen, iC carbon, iN nitrogen, iO oxygen, iP phosphor and iS sulfur atoms is  . This follows because for an element E with r isotope types, a molecule El consisting of l atoms of the element has

. This follows because for an element E with r isotope types, a molecule El consisting of l atoms of the element has  different isotope species. The probability that a certain isotope species occurs can be computed by multiplying the probabilities of the underlying isotopes.

different isotope species. The probability that a certain isotope species occurs can be computed by multiplying the probabilities of the underlying isotopes.

Even with high-resolution MS, it is often impossible to resolve isotope species with identical nominal mass. Instead, these isotope species appear as one single peak in the MS output. For this reason, we merge isotope species with identical nominal mass; we refer to the resulting distribution as the molecule's isotopic distribution.

For each element E we define two discrete random variables, denoted XE and YE, representing the mass and the mass number, respectively. For example, XC with state space {12, 13.003355}, YC with state space {12,13} and ℙ(XC = 12) = ℙ(YC = 12) = 0.98890, ℙ(XC = 13.003355)=ℙ(YC = 13) = 0.01110 are the random variables of carbon. Given a molecule consisting of l atoms, we assign to the i-th atom, i=1,…,l, two random variables Xi and Yi, where Xi ∼ XE and Yi ∼ YE, with E being the corresponding element. Now we can represent the molecule's mass distribution by the random variable X := X1 +…+ Xl, and its nominal mass distribution, or isotopic distribution, by Y := Y1 + … + Yl. In an ideal mass spectrum, normalized peak intensities correspond to the isotopic distribution of the molecule. Note that X and Y are correlated, since XE can be viewed as a function of YE and E.

We refer to the peak at the monoisotopic mass as the monoisotopic peak, which is followed by the +1, +2, … peaks. What is the mass of the +k peak, which is a superposition of several isotope species? It is reasonable to assume that its mass is the mean mass of all isotope species that add to its intensity (Rockwood et al., 2004): for a molecule with monoisotopic nominal mass N, let X = X1 + ··· + Xl be the mass distribution and Y = Y1 + ··· + Yl be the isotopic distribution. The mean peak mass of the +k peak is then mk = 𝔼(X | Y=N+k). We refer to the isotopic distribution together with the mean peak masses as the molecule's isotope pattern.

3 METHODS AND ALGORITHMS

3.1 Real-valued decompositions

We first concentrate on the problem of decomposing the monoisotopic mass M0. We want to find all molecules with monoisotopic mass in the interval [l,u] ⊆ ℝ where l:=M0−ε and u:=M0+ε for some measurement inaccuracy ε. Formally, we search for all solutions of the integer knapsack equation (Kellerer et al., 2004)

| (1) |

where aj, j=1,…,n are real-valued monoisotopic masses of elements satisfying aj ≧ 0. We search for all solution vectors c = (c1,…,cn) such that all cj are non-negative integers. We may assume a1 < a2 < … < an.

A straightforward solution is to enumerate all vectors c with c1=0 and ∑j aj cj ≤ u and next to test if there is some c1 ≧ 0 such that ∑j aj cj ∈ [l,u]. This results in Θ(M0n-1) running time, for constant element masses. Alternatively, we can compute all potential decompositions up to some upper bound U during preprocessing, sort them with respect to mass and use binary search; this results in Θ(Un) space requirement. These approaches are unfavorable in theoretical complexity as well as in practice: for the elements CHNOPS there exist more than 7 × 109 molecular formulas with mass ≤1500 Da.

In the remainder of this section, we transform the integer knapsack problem with real-valued coefficients into a problem instance with integer coefficients. We will show in the next section how to efficiently solve such instances. Choosing a blowup factor b ∈ ℝ, corresponding to precision 1/b, we can round coefficients by ϕ(x) := ⌈ bx ⌉, so  and l′ := ϕ(l), u′ := ϕ(u) form an integer knapsack. Precision 1/b is merely a parameter of the decomposition algorithm and in principle independent of the measurement mass accuracy ε. To avoid rounding error accumulation, precision is usually set one to two orders of magnitude smaller than the measurement accuracy. Now, certain solutions c of the integer coefficient knapsack are no solutions of the real-valued coefficient knapsack and vice versa. We can easily sort out false positive solutions by checking (1), resulting in additional running time. We now concentrate on the more intriguing problem of false negative solutions that are missed by the integer coefficient knapsack.

and l′ := ϕ(l), u′ := ϕ(u) form an integer knapsack. Precision 1/b is merely a parameter of the decomposition algorithm and in principle independent of the measurement mass accuracy ε. To avoid rounding error accumulation, precision is usually set one to two orders of magnitude smaller than the measurement accuracy. Now, certain solutions c of the integer coefficient knapsack are no solutions of the real-valued coefficient knapsack and vice versa. We can easily sort out false positive solutions by checking (1), resulting in additional running time. We now concentrate on the more intriguing problem of false negative solutions that are missed by the integer coefficient knapsack.

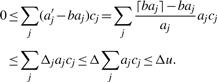

Clearly ∑j aj cj ≧ l implies  since all

since all  are integers. We have to increase the upper bound u′ to guarantee that all solutions of (1) are generated. We define relative rounding errors

are integers. We have to increase the upper bound u′ to guarantee that all solutions of (1) are generated. We define relative rounding errors

and note that  . Let Δ = Δ(b) := max {Δj}. If c satisfies ∑j aj cj ≤ u then

. Let Δ = Δ(b) := max {Δj}. If c satisfies ∑j aj cj ≤ u then  : clearly,

: clearly,  and our claim follows from

and our claim follows from

|

One can easily check that this bound is tight. So, we re-define the integer interval by u′ := ⌊bu + Δ u ⌋. Without rounding correction we have to decompose (u−l) b integers, but rounding correction forces us to decompose an additional Δ u integers, independent of the interval size u−l. As an example, consider the elements CHNOPS and blowup factor b = 105, then Δ(b) = ΔH (b) = 0.492936. So for M0 = 1000, we have to decompose an additional 492 integers. Clearly, increasing b usually decreases Δ(b). We stress that the running time of this approach is dominated by the number of decompositions of these integers, and not by the number of integers itself.

3.2 Integer decompositions

Assume that both the element masses a1,…,an and the query mass m are positive integers. We are looking for all non-negative integer vectors (c1,…,cn) satisfying (1) (with l = u = m). This is a well-studied problem, referred to in its different variants as Coin Change Problem, Change Making Problem or Money Changing Problem, and can be solved with a simple dynamic programming algorithm in pseudo-polynomial time (Martello and Toth, 1990). The main disadvantage of this approach is rather large memory requirement, which again depends on the maximal mass U we want to decompose.

Böcker and Lipták (2007) present an algorithm for determining all such decompositions with running time O(na1 · γ(m)) and space O(na1), where a1 is the smallest mass and γ(m) the number of decompositions of mass m. We briefly sketch the algorithm. Given integer masses a1 ≤ … ≤ an, a data structure of size na1, referred to as Extended Residue Table (ER table), is computed in a preprocessing step. Entry ER(r,i), for r=0,…, a1−1 and i=1,…,n, is the smallest number congruent r modulo a1 which is decomposable over a1,…,ai. Thus, the last column ER(·,n) of the table gives, for each residue r, the smallest number congruent r modulo a1 that is decomposable over a1,…,an. Computation time is O(na1). All decompositions of the query m are then recursively generated, limiting the number of unsuccessful paths by using information from the ER table. As a result, the running time of the algorithm is proportional only to the size of the table na1 and the number of decompositions γ(m), and does not depend directly on the input m. For decomposing molecule masses, this decomposition technique has several advantages over classical dynamic programming, such as improved running times and preprocessing independent of the largest mass we want to decompose in the future. Regarding the application of decomposing molecule masses, this approach uses only one fifteenth of memory and shows better running times.

The number of decompositions γ(m) for an integer mass m over coprime integers a1,…,an asymptotically behaves like a polynomial of degree n−1 in m (Wilf, 1990). Following Beck et al. (2001), we can approximate the number of molecules over the elements CHNOPS with real mass in the interval [M,M+ϵ] by

| (2) |

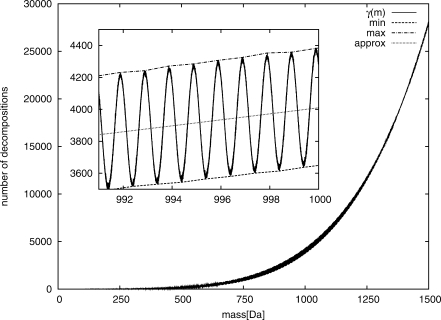

We can also approximate the number of molecules with mass up to M by integrating (2). In Figure 1, we plot the number of decompositions for masses of up to 1500 Da over the elements CHNOPS.

Fig. 1.

Number of decompositions over the elements CHNOPS for intervals of width 0.001 Da. Minima and maxima taken in intervals of width 1 Da. True number of decompositions in comparison with approximate (2) (approx). As is shown in the inlay, γ(m) varies with a periodic function of period ∼1 Da.

3.3 Simulating isotope patterns

We first observe that for elements CHNOPS, all molecules have isotopic distributions that decrease rapidly with increasing mass. In particular, we can restrict ourselves to computing the first K non-zero values of the distribution, for rather small K such as K=10. For example, amongst 11 479 entries in the KEGG COMPOUND database with mass ≤3000 Da, no molecule has intensity of the +10 peak larger than 0.00007.

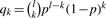

The atoms hydrogen, carbon and nitrogen have only two natural isotopes. Thus, the isotopic distribution of a molecule El consisting of l identical atoms of type E with E ∈ {H,C,N} follows a binomial distribution: let qk denote the probability that El has nominal mass N+k, where N is the monoisotopic nominal mass of El. Then,  , where p is the probability of the monoisotopic isotope. The values of the qk can be computed iteratively, since

, where p is the probability of the monoisotopic isotope. The values of the qk can be computed iteratively, since  for k≧ 0, thus computation time is O(K).

for k≧ 0, thus computation time is O(K).

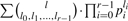

Where an element E has r>2 isotopes (such as oxygen and sulfur), the isotopic distribution of El can in theory be computed as follows: let pi for i=0,…,r−1 denote the probability of occurrence of the i-th isotope. Then, the probability that El has nominal mass N+k is  , where the sum runs over all l0,…,lr−1 ≧ 0 satisfying

, where the sum runs over all l0,…,lr−1 ≧ 0 satisfying  and

and

(Hsu, 1984). However, this computation is infeasible in practice.

(Hsu, 1984). However, this computation is infeasible in practice.

Given two discrete random variables Y and Y′ with state spaces Ω,Ω′ ⊆ ℕ, we can compute the distribution of the random variable Z := Y+Y′ by folding the distributions,

If we restrict ourselves to the first K values of this distribution, we can compute it in time O(K2). Kubinyi (1991) suggests to compute the isotopic distributions of oxygen Ol and sulfur Sl by successive folding of the respective distribution: using a Russian multiplication scheme for the folding, this results in an algorithm with running time O(K2 log l). In applications, we do not compute these distributions on the fly but during preprocessing, for all l≤L fixed. This results in O(KL) memory for every such element, where l is small: The 128 oxygen atoms already have mass of about 2048 Da, exceeding the relevant mass range. For molecules consisting of different elements, we first compute or look up the isotopic distributions of the individual elements, and then combine these distributions by folding in O(n · K2) time.

Using Fourier transforms of isotope distributions, we can multiply Fourier transforms instead of folding these distributions (Rockwood and Van Orden, 1996). Doing so we can eventually replace the K2 factor in the algorithm's running time by a KlogK factor. As we limit our attention to small K such as K=10, this will not result in a speedup of the algorithm in practice. Also, this approach may face the problem of numerical errors.

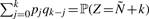

We now come to the more challenging problem of efficiently computing the mean peak masses of a distribution. Doing so using the definition mk =𝔼(X | Y=N+k) is highly inefficient, because we have to sum up over all isotope species. Pruning strategies have been developed to speed up computation (Yergey, 1983), but pruning leads to a loss of accuracy (Rockwood et al., 2004). We now present a simple recurrence for computing these masses analogous to the folding of distributions: let Y = Y1 + ··· + Yl and  be isotopic distributions of two molecules with monoisotopic nominal masses N and N′, respectively. Let pk := ℙ(Y = N+k) and qk := ℙ(Y′ = N′′k) denote the corresponding probabilities, mk and

be isotopic distributions of two molecules with monoisotopic nominal masses N and N′, respectively. Let pk := ℙ(Y = N+k) and qk := ℙ(Y′ = N′′k) denote the corresponding probabilities, mk and  the mean peak masses of the +k peaks. Consider the random variable Z = Y + Y′ with monoisotopic nominal mass Ñ = N+N′.

the mean peak masses of the +k peaks. Consider the random variable Z = Y + Y′ with monoisotopic nominal mass Ñ = N+N′.

Theorem 1. —

The mean peak mass

of the +k peak of the random variable Z = Y + Y′ can be computed as:

(3)

Note that  . Since by independence, ℙ(Y1=N1,…,Yl=Nl) = ∏i ℙ(Yi=Ni), the theorem follows by rearranging summands. We omit the formal proof.

. Since by independence, ℙ(Y1=N1,…,Yl=Nl) = ∏i ℙ(Yi=Ni), the theorem follows by rearranging summands. We omit the formal proof.

The theorem allows us to ‘fold’ mean peak masses of two distributions to compute the mean peak masses of their sum. This implies that we can compute mean peak masses as efficiently as the distribution itself. This improves on the previously best known method (Rockwood et al., 2004), replacing the linear running time dependence on the number of atoms by its logarithm.

3.4 Scoring candidate molecules

We want to discriminate between (tens of thousands of) candidate molecules generated by decomposing the monoisotopic mass. To this end, we compare the simulated isotopic distribution with the measured peaks. Matching peak pairs between the spectra is trivial for this application.

Zhang and Chait (2000) and Zhang et al. (2002) suggest to use Bayesian Statistics to evaluate mass spectra matches:

| (4) |

where 𝒟 is the data (the measured spectrum), ℳi are the models (the candidate molecules) and ℬ stands for any prior background information.

Regarding this background information, we set the prior probability ℙ(ℳj | ℬ) to zero for all molecules but the decompositions of the monoisotopic mass. We also assign prior probability zero to molecular formulas that cannot correspond to a molecule, because of chemical considerations: Senior's third theorem states that the sum of valences has to be greater than or equal to twice the number of atoms minus one (Senior, 1951). Molecules violating Seniors third theorem are rare, particularly for natural compounds: in the KEGG COMPOUND database, <0.16% of substances violate this rule. We also filter out radicals with odd sum of valences. We refrain from using further priors such as the hetero-to-carbon ratio (Kind and Fiehn, 2007) because this might rather reproduce what is already known.

Next, we assign probabilities to the observed masses and intensities. Assuming independence (in particular from background information) we calculate

| (5) |

Here, ℙ(Mj|mj) is the probability to observe peak j at mass Mj when its true mass is mj, and ℙ(fj|pj) is the probability to observe peak j with intensity fj when its true intensity is pj. Clearly, the independence of peak intensities is violated because these intensities sum to one, but this product can be seen as a rough estimate of the true probability.

Mass spectrometrists assume that the mass error of a device is roughly normally distributed with mean zero. If the mass accuracy α of the measurement (in p.p.m.) is given, then we can set the standard deviation  for peak j, assuming that >99.7% of measurements fall into the specified mass range. But we also observe that peaks of low intensity show less mass accuracy than those with high intensity, which can be attributed to the difficulties of separating a peak of low intensity from the background noise. Our data indicate a roughly linear dependence between peak intensity and mass accuracy. To this end, two mass accuracies α1 (at full intensity) and α0 (at minimal intensity) are provided by the user, and we set

for peak j, assuming that >99.7% of measurements fall into the specified mass range. But we also observe that peaks of low intensity show less mass accuracy than those with high intensity, which can be attributed to the difficulties of separating a peak of low intensity from the background noise. Our data indicate a roughly linear dependence between peak intensity and mass accuracy. To this end, two mass accuracies α1 (at full intensity) and α0 (at minimal intensity) are provided by the user, and we set

We want to estimate the probability that, given a peak with true mass Mj, a peak at mass Mj is observed in the measured spectrum: more precisely, the probability of observing a mass difference of |Mj−mj| or larger. We can compute this probability using the complementary error function ‘erfc’:

| (6) |

with  .

.

Even for high-resolution MS, spectra show a systematic mass shift due to calibration inaccuracies. We can easily eliminate this shift for all masses but the monoisotopic mass: we do not compare masses of the +1, … peaks directly but instead the difference to the monoisotopic peak, Mj − M0 versus mj − m0 for j ≧ 1.

Regarding peak intensities, we have to cope with a systematic error in the measured spectra: we observe in our data that peaks of low intensity are under-estimated in the measured spectrum, whereas peaks of high intensity are over-estimated, (Supplementary Fig. 1). We ascribe this problem to inaccurate peak intensity determination: vendor software estimates peak intensities as signal-to-noise ratio or height above some baseline. The baseline, in turn, is determined using several ad hoc rules, and its estimate can be inaccurate. Unfortunately, such inaccuracies have unequal effects on peaks of different intensities. We correct this error by adding some user-defined parameter off to the measured intensities fi, and by subsequent re-normalization. We found that for both of our datasets, the same parameter off = +0.02 leads to excellent results.

Computation of ℙ(fj|pj) is done analogously to that of ℙ(Mj|mj). Our data indicates that after correction, log ratios between measured and predicted peak intensity log (fj/pj) roughly follow a normal distribution. Again, precision parameters β1 (at full intensity) and β0 (at minimal intensity) are provided by the user (in percent). We compute

as our precision interval, such that >99.7% of log intensity ratios log (fj/pj) fall into the range  . Now, ℙ(fj|pj) can be estimated analogously to (6).

. Now, ℙ(fj|pj) can be estimated analogously to (6).

4 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

4.1 Datasets

To evaluate our method we used two datasets measured on two instruments. Mass spectra with single charge were measured from several organic (macro)molecules, composed of the elements CHNOPS. For every such spectrum, the sum formula of the sample molecule is known. The spectra were acquired over a period of 2 years; the molecules range in mass from 117 Da to ∼1000 Da. Peak detection and estimation of peak masses and intensities were conducted using vendor software.

The first dataset consists of 153 mass spectra. Electrospray ionization (ESI) experiments were performed using the Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR) mass spectrometer APEX III (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). The FT-MS was equipped with a 7.0 T, 160 mm bore superconducting magnet, infinity cell and interfaced to an external (nano)ESI ion source. All mass spectra were externally mass calibrated. The five analysis parameters were chosen as α1 = 3, α0 = 6, β1 = 10, β0 = 90 and off = +0.02.

The second dataset consists of 86 mass spectra. ESI experiments were performed using the oa-TOF mass spectrometer MicrOTOF (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). Quasi-internal mass calibration was used, by measurement of an infused calibrant prior to the compound of interest. For the oa-TOF analysis, we set α1 = 5, α0 = 6.5, β1 = 10, β0 = 90 and again off = +0.02.

4.2 Identification accuracy

Every input ‘mass spectrum’ consists of masses M0,…,Mk and intensities f0,…,fk. For every such spectrum, we computed all molecules such that the monoisotopic mass M0 has relative mass difference of at most α1 p.p.m. Next, we discarded molecules violating Senior's third theorem and radicals with odd sum of valences. For each remaining molecule, we computed its theoretical isotopic distribution (with K=10) and compared it to the measured isotopic distribution. We ranked the molecules according to resulting probabilities. We did not use any other background information to identify the molecule.

For the 153 mass spectra in our FT-ICR dataset, 89 resulted in a correct identification; in 86% of the mass spectra, the correct interpretation was found in the TOP 10 explanations. There is a clear correlation between mass and identification accuracy, confer Table 2. For mass spectra ≤700 Da, the true interpretation was always found in the TOP 10 explanations, except in one case where it had rank 13. For 86 mass spectra in the oa-TOF dataset, the correct sum formula was found in the TOP 10 interpretations in all but two cases. Moreover, 79 out of 86 compounds were correctly identified, which correspond to an identification rate of >90%, (Table 2). Better identification results on the oa-TOF dataset with lower mass accuracy show the crucial importance of including intensity measurements into the candidate evaluation. We note that the intensity accuracy of the oa-TOF instrument is significantly higher than that of the FT-ICR. We have also tested the variation of identification rates with different scoring parameters: identification results are relatively stable for small disturbances of parameter values, see supplementary material. Parameter estimation could be automated using a small training set. We are planning to include this feature in future implementations.

Table 2.

Number of correct sum formulas at certain positions of the output list, for the FT-ICR dataset and the oa-TOF dataset

| Mass range | No. sp. | Rank in output list |

No. sum formulas |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3–5 | 6–10 | 11+ | Int. | Real | Chem. | Time | ||

| FT-ICR dataset | ||||||||||

| 200–300 | 13 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 37.2 | 8.6 | 1.5 |

| 300–400 | 37 | 28 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 200 | 109 | 10.4 | 4.3 |

| 400–500 | 57 | 39 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 579.5 | 318.2 | 22.8 | 13.5 |

| 500–600 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1800.4 | 990.3 | 59.6 | 40.1 |

| 600–700 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2668.5 | 1454 | 37.3 | 55 |

| 700–800 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8797.8 | 4812 | 247 | 232 |

| 800–900 | 14 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 14781.6 | 8101 | 534.6 | 485 |

| 900–1000 | 16 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 | 31805.7 | 17448 | 1570 | 1281 |

| Mass range | No. sp. | Rank |

No. sum formulas |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2–6 | 11+ | Int. | Real | Chem. | Time | ||

| oa- TOF dataset | ||||||||

| 100–200 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 11.3 | 7.4 | 1.9 | 0 |

| 200–300 | 21 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 60.1 | 40.1 | 4.6 | 1.4 |

| 300–400 | 27 | 26 | 1 | 0 | 297.8 | 199.7 | 22.6 | 8.1 |

| 400–500 | 15 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 725.6 | 484.1 | 32.4 | 17.3 |

| 500–600 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1479.1 | 988.9 | 54.3 | 36 |

| 600–700 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4600 | 3080 | 276 | 130 |

| 700–800 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 10336 | 6909 | 578 | 461 |

| 800–900 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 18172.3 | 12146 | 914.3 | 757 |

We report the number of spectra in this mass range (no. sp.), as well as the average number of sum formulas over all molecules in the mass range (no. sum formulas). We distinguish between the number of integer decompositions (int.), the number of real decompositions (real) and the number of those sum formulas that pass Senior's third theorem (chem.). Finally, we give the average running time in milliseconds per spectrum (time).

4.3 Running times

We analyzed all 239 mass spectra on a Pentium M 1.5 GHz processor with blowup b = 5 × 104, using only a few Megabyte of memory. This results in running times of <1.3s per spectrum for the complete analysis of one mass spectrum. Clearly, running times depend on molecule masses, see again Table 2. Increasing the blowup beyond 5 × 104 increased running times, presumably because the smaller table can be kept in the processor cache.

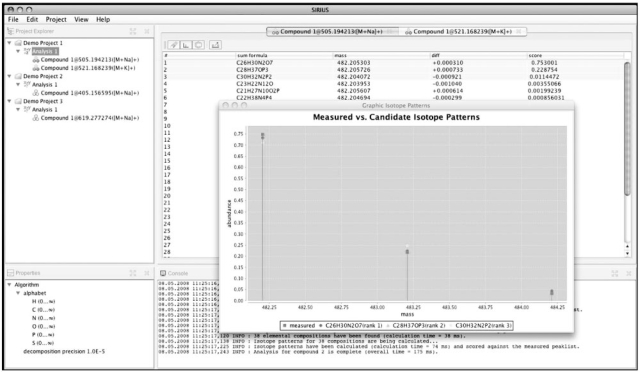

5 IMPLEMENTATION

We have developed a java-based graphical tool called SIRIUS. At the SIRIUS core lie efficient algorithms for generating all elemental compositions for a given mass and error, calculating isotope patterns for all chemically relevant compositions, and matching and ranking the candidate molecules against the input spectrum. SIRIUS combines these algorithms with a powerful graphical user interface. An extensive management system allows simplified data handling and offers an easy way to integrate new algorithms and data structures into the framework. Through a user-friendly interface, SIRIUS allows the user to import datasets in most common mass spectrometry file formats. It supports automatic recognition of molecular ion adducts present in the input spectrum, handy visualization of identified sum formulas and their isotope patterns and customizable export of identification results to common human-readable file formats. Finally, the software provides a basic functionality to search for sum formulas identified by the algorithm in NCBI PubChem Database.1

Preparation of a new analysis run can be divided into the following steps: initializing input data and instrument parameters, setting up algorithm parameters and extracting isotope patterns from the input peaklist. Input peaklist and machine settings can be reused for multiple analyses on the same data. SIRIUS provides the user with reasonable default values for algorithm parameters. The program also offers to save all algorithm and mass spectrometer settings. To this end, SIRIUS creates a persistent workspace that can be used to store local settings and to automatically reload them on request.

We use the ProteomeCommons.org IO Framework (Falkner et al., 2007) to import mass spectrometry data, which allows reading most MS data formats including mzData and mzXML. We parse the peaklist and divide it into signal groups related to different compounds. A peaklist can also contain several signal groups belonging to the same compound, modified by different molecular ion adducts. Identifying modifications is done by calculating mass differences between monoisotopic peak masses. In view of the small number of adducts, we apply a simple exhaustive search to find all matching mass differences. If there is no prior knowledge on the source of modification, the user can choose one or more adduct types for an isotope pattern.

The output of the algorithm is a list of candidate sum formulas for each compound. Sum formulas are listed in the summary table, sorted in decreasing order of likelihoods. To view an entry in more detail, the user can select and compare theoretical and measured isotope patterns visually, (Fig. 2). Analysis results can be exported to the application workspace and opened for further evaluation. Export file formats include plain text, PDF and XML documents.

Fig. 2.

Screenshot of the SIRIUS software, available from http://bio.informatik.uni-jena.de/sirius.

6 CONCLUSION

We presented an approach to determine the sum formula of an unknown metabolite solely from its high-resolution isotope pattern. Our approach allows us to reduce the number of potential sum formulas to only a few candidates; in many cases we were able to determine the correct molecular formula. The approach is time- and memory-efficient and can be executed on a regular desktop PC. We further presented methods for the efficient simulation of isotope patterns. This is vital for larger molecules where the search space increases rapidly.

Results on experimental data clearly show the potential of our approach, in particular for oa-TOF data. In our evaluation, we have deliberately ignored some information such as prior probability of the elements or hetero-to-carbon ratio (Kind and Fiehn, 2007). We believe that such information should rather be used in a ‘post-processing’ step by an expert, instead of automatically filtering out certain sum formulas a priori. Finally, we introduced a user-friendly software called SIRIUS, which implements all of the methods presented.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Additional programming by Martin Engler. We thank Dr H. Luftmann, Universität Münster, Organisch-Chemisches Institut, for making available the oa-TOF dataset and an anonymous referee for helpful comments.

Funding: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BO 1910/1 to A.P.); Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, within the group ‘Combinatorial Search Algorithms in Bioinformatics’ (to Z.L.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- Audi G, et al. The AME2003 atomic mass evaluation (ii): Tables, graphs, and references. Nucl. Phys. A. 2003;729:129–336. [Google Scholar]

- Beck M, et al. The polynomial part of a restricted partition function related to the frobenius problem. Electron. J. Comb. 2001;8:N7. [Google Scholar]

- Böcker S, Lipták Z. A fast and simple algorithm for the Money Changing Problem. Algorithmica. 2007;48:413–432. [Google Scholar]

- Böcker S, Rasche F. Towards de novo identification of metabolites by analyzing tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:I49–I55. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkner JA, et al. Proteomecommons.org io framework: reading and writing multiple proteomics data formats. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:262–263. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CS. Diophantine approach to isotopic abundance calculations. Anal. Chem. 1984;56:1356–1361. [Google Scholar]

- Iijima Y, et al. Metabolite annotations based on the integration of mass spectral information. Plant J. 2008;54:949–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, et al. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucl. Acids Res. 2006;34:D354–D357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerer H, et al. Knapsack Problems. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kind T, Fiehn O. Metabolomic database annotations via query of elemental compositions: mass accuracy is insufficient even at less than 1 ppm. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind T, Fiehn O. Seven golden rules for heuristic filtering of molecular formulas obtained by accurate mass spectrometry. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubinyi H. Calculation of isotope distributions in mass spectrometry: a trivial solution for a non-trivial problem. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1991;247:107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Martello S, Toth P. Knapsack Problems: Algorithms and Computer Implementations. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood AL, Van Orden SL. Ultrahigh-speed calculation of isotope distributions. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:2027–2030. doi: 10.1021/ac951158i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood AL, et al. Isotopic compositions and accurate masses of single isotopic peaks. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectr. 2004;15:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior J. Partitions and their representative graphs. Am. J. Math. 1951;73:663–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wilf H. Generating functionology. New York: Academic Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yergey JA. A general approach to calculating isotopic distributions for mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Phys. 1983;52:337–349. doi: 10.1002/jms.4498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, et al. Predicting molecular formulas of fragment ions with isotope patterns in tandem mass spectra. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2005;2:217–230. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2005.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, et al. ProbID: a probabilistic algorithm to identify peptides through sequence database searching using tandem mass spectral data. Proteomics. 2002;2:1406–1412. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200210)2:10<1406::AID-PROT1406>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Chait BT. ProFound: an expert system for protein identification using mass spectrometric peptide mapping information. Anal. Chem. 2000;72:2482–2489. doi: 10.1021/ac991363o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.