Abstract

Post-harvest withering of grape berries is used in the production of dessert and fortified wines to alter must quality characteristics and increase the concentration of simple sugars. The molecular processes that occur during withering are poorly understood, so a detailed transcriptomic analysis of post-harvest grape berries was carried out by AFLP-transcriptional profiling analysis. This will help to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of berry withering and will provide an opportunity to select markers that can be used to follow the drying process and evaluate different drying techniques. AFLP-TP identified 699 withering-specific genes, 167 and 86 of which were unique to off-plant and on-plant withering, respectively. Although similar molecular events were revealed in both withering processes, it was apparent that off-plant withering induced a stronger dehydration stress response resulting in the high level expression of genes involved in stress protection mechanisms, such as dehydrin and osmolite accumulation. Genes involved in hexose metabolism and transport, cell wall composition, and secondary metabolism (particularly the phenolic and terpene compound pathways) were similarly regulated in both processes. This work provides the first comprehensive analysis of the molecular events underpinning post-harvest withering and could help to define markers for different withering processes.

Keywords: AFLP-TP, gene expression, grape berry withering, on- and off-plant withering processes

Introduction

The study of grape development and post-harvest maturation is of great interest to plant biologists, providing particular insight into the genetic and environmental factors controlling berry ripening and the organoleptic properties of wine (Conde et al., 2007; Deluc et al., 2007; Grimplet et al., 2007; Pilati et al., 2007). Berries for sweet dessert wines (e.g. Recioto, Vin Santo) and dry fortified wines (e.g. Amarone) undergo a phase of post-harvest dehydration which can last up to 3 months, where metabolism is modified significantly and the sugar content increases (Kays, 1997). In post-harvest berries, the rate of water loss induces cell wall enzyme activity, increases respiration and ethylene production, and causes the loss of volatiles and changes in polyphenol levels (Hsiao, 1973; Bellincontro et al., 2004; Costantini et al., 2006). Air drying and its impact on turgor pressure also leads to major changes in fruit structure and texture, such as softening, a change in superficial cell architecture, the reduction of intercellular space, and cell squeezing (Ramos et al., 2004).

Studies of metabolic changes in Malvasia, Trebbiano, and Sangiovese grapes during post-harvest drying revealed that berry cells undergo an initial water stress response at 10–12% weight loss, characterized by the accumulation of abscisic acid (ABA), proline, and lipoxygenase. A second dramatic change in metabolism occurs at >19% weight loss, characterized by the accumulation of proline and an increase in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) activity. This two-step metabolism leads initially to the formation of C6 compounds, ethanol and acetaldehyde, which subsequently decrease due to the formation of ethyl acetate (volatile acidity) (Costantini et al., 2006).

At the molecular level, very little is known about the post-harvest phase of fruit ripening, and the only previous studies in grape relate to the modulation of stilbene synthase and phenylalanine ammonia lyase genes (Versari et al., 2001; Tonutti et al., 2004). The aim of this study was to determine whether the known enzymatic and hormonal activities in withering grape berries reflect changes at the mRNA level. Gene expression profiles characterizing the on- and off-plant withering process in Vitis vinifera cv. Corvina were studied by amplified fragment length polymorphism-transcriptional profiling (AFLP-TP).

Materials and methods

Plant material and total RNA extraction

Clusters of Vitis vinifera cv. Corvina (clone 48) were harvested over the course of the 2003 growing season from an experimental vineyard in the Verona Province (San Floriano, Verona, Italy). Berries were sampled at eight time points from early fruitset until the completion of withering (Table 1). The post-harvest ripening phase was analysed by sampling clusters directly from plants (on-plant withering) or by collecting clusters picked from the plant on the same date (off-plant withering) and stored in a special, naturally-ventilated room or ‘fruttaio’ lacking a controlled environment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sampling time-points and corresponding physiological data

| Sampling time point | Days before or after ripening | Per cent weight | Brix degree |

| Post fruit-set; PFS | –92 d | ||

| Pre-véraison; PRV | –65 d | ||

| Véraison; V | –41 d | ||

| Ripening; R | 0 | 100% | 22.10° |

| Off-plant withering I; WI | +22 d | 83.20% | 28.60° |

| Off-plant withering II; WII | +41 d | 77.40% | 30.00° |

| Off-plant withering III; WIII | +74 d | 70.20% | 32.20° |

| Off-plant withering IV; WIV | +99 d | 67.30% | 32.80° |

| On-plant withering I; WI | +22 d | 101.10% | 24.80° |

| On-plant withering II; WII | +41 d | 98.20% | 26.20° |

| On-plant withering III; WIII | +74 d | 97.60% | 26.10° |

Eight clusters were collected for each sampling time-point (about 1 kg). Five hundred berries were sampled from different positions of the eight clusters, discarding rotten or small undeveloped berries. Skin and flesh of 100 berries were separated, discarding seeds, and immediately frozen. The 400 remaining berries were weighted; weight percentages of on- and off-plant withering samples were calculated in comparison to the weight of the ripening sample (Table 1). The sugar content of the juice obtained from ripening and on- and off-plant withering berries was measured using a bench refractometer PR-32 (Atago Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Total RNA was extracted from skin and flesh samples according to Rezaian and Krake (1987).

AFLP-TP analysis

AFLP-based transcript profiling (AFLP-TP) (Breyne et al., 2003) was carried out starting from 10 μg of total RNA (half from the skin and half from the flesh) and using restriction enzymes BstYI and MseI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA). For pre-amplification, a MseI primer without a selective nucleotide was combined with a BstYI primer containing a T or a C as a selective nucleotide at the 3′ end. The pre-amplified samples were diluted 600-fold and 5 μl were used for the final selective amplifications with a BstT/C primer with one more selective nucleotide (BstT0: 5′-GAC TGC GTA GTG ATC T-3′ and BstC0: 5′-GAC TGC GTA GTG ATC C-3′) and an MseI primer (Mse0: 5′-GAT GAG TCC TGA GTA A-3′) with two selective nucleotides. All 128 possible primer combinations were used. Selective γ[33P]ATP-labelled amplification products, were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel using the Sequigel system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Dried gels were exposed to Biomax films (Kodak, Rochester, NY). The mean number of fragments amplified with one primer combination was 75.

Differentially-expressed transcripts were identified by visual inspection of autoradiographic films and their profiles were visually scored (on a scale from −2 to 2; see Supplementary Table S2 at JXB online). Hierarchical clustering was carried out using a complete linkage algorithm and the Pearson correlation as a distance measure (Michael Eisen, Stanford University) (http://rana.lbl.gov/EisenSoftware.htm). Bands corresponding to differentially-expressed transcripts were excised from the gels and eluted in 100 μl distilled water. DNA was re-amplified under the conditions described above and purified on MultiScreen plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) prior to sequencing (BMR Genomics) (http://bmr.cribi.unipd.it). The tag sequences were used for BLASTN and BLASTX (Altschul et al., 1990) searches against the DFCI Grape Gene Index database (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/cgi-bin/tgi/gimain.pl?gudb=grape) and the non-redundant UNIPROT database (http://www.expasy.uniprot.org), respectively, using an E-value cut-off of 5×10−4. Gene Ontology terms (http://www.geneontology.org) were assigned to each sequence using the BLASTN and BLASTX results.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

The transcriptional profiles of six AFLP-TP tags were analysed by real-time RT-PCR experiments using the SYBR® Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the Mx3000P Real-Time PCR system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Gene-specific primers were designed for the six tags using the sequence information of the same tags and of the corresponding TC. A primer pair was also designed for TC55334, encoding an actin protein. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online. The real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed in a 25 μl reaction volume using a final primer concentration of 300 nM and cDNA synthesized from 40 ng of total RNA, in three replicates for each reaction. The PCR began with a 50 °C hold for 2 min and a 95 °C hold for 10 min followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 20 s. Non-specific PCR products were identified by the dissociation curves. The amplification efficiency was calculated from raw data using LingRegPCR software (Ramakers et al., 2003). The relative expression ratio value was calculated for development time points and withering time points relative to the first sampling time point (post-fruit-set; PFS) according to the Pfaffl equation (Pfaffl, 2001). SE values were calculated according to Pfaffl et al. (2002).

Results and discussion

AFLP-TP analysis

AFLP-TP, a gel-based transcript profile method, is a genome-wide transcriptional analysis with some advantageous features over microarrays. No prior sequence information is required for AFLP-TP analysis, the low start-up cost and its high specifity allow analysing the expression profile of genes with high homology (Vuylsteke et al., 2007). The procedure of purification, amplification, and sequecing of tags required by AFLP-TP analysis is time-consuming, labour-intensive and cannot be automated. However, the gene discovery possibility of AFLP-TP is still an important advantage which can complement the recently obtained genomic informations (French-Italian Public Consortium for Grapevine Genome Characterization, 2007; Velasco et al., 2007). For these reasons, an AFLP-TP analysis was used to obtain a large-scale description of the transcriptional changes of grapevine berries during withering, a process uncharacterized up to now. Other aspects of grape berry development have been investigated by microarray analysis, such berry ripening under normal and water stress conditions (Terrier et al., 2005; Waters et al., 2005; Deluc et al., 2007; Grimplet et al., 2007; Pilati et al., 2007; Lund et al., 2008).

Eight sampling times were chosen during the 2003 Vitis vinifera cv. Corvina growing season, four covering the entire period of berry development (Table 1) and up to four covering the subsequent 99 d post-ripening period (Table 1). In the latter case, two different withering processes, one on-plant and one off-plant, were considered. For the on-plant withering process, only the first three sampling points were used, due to the poor quality of the berries at the final stage (Table 1).

The kinetics of the withering processes was monitored by evaluating weight loss and the sugar content of berry juice (Table 1). For on-plant withering, a negligible weight loss was recorded (Table 1) because grape clusters connected to the shoot are not subjected to intense dehydration. The observed increase in sugar concentration is mainly due to the over-ripening process (Table 1).

During the 2003 growing season, temperature values higher than the seasonal average values and lower rainfall were recorded in the sampling area. These climatic conditions influenced berry development and resulted in the anticipated ripening. Similar conditions, recorded for the autumn season, could have affected withering and, in particular, dehydration, which characterizes the off-plant withering process.

AFLP-TP analysis was performed mixing an equal amount of total RNA extracted from skin and flesh tissues for each sampling time-point, to overcome problems related to RNA extraction efficiency. RNA yields from skin and flesh tissues could be negatively affected by polyphenol and sugar contents which, moreover, change during the berry development and withering processes. Because RNA extracted from whole berries derives from unknown quantities of skin and flesh RNAs and because these can be differently affected by the extraction procedure during the analysis, it was decided to mix equal amounts of skin and flesh RNAs and to maintain the same total RNA quantity over the whole experiment. Although this procedure can introduce some bias, it is believed that these are preferable to the analysis of an unknown and varying RNA content of samples.

The expression of approximately 9600 transcripts, representing almost one-third of the protein-coding genes predicted in the grapevine genome (French-Italian Public Consortium for Grapevine Genome Characterization, 2007), was analysed using 128 different BstYI+1/MseI+2 primer combinations for selective amplification. Among these transcripts, 2093 were found to be differentially expressed during berry development and/or withering. The differentially expressed tags were excised from the gels, and 1829 were successfully re-amplified by PCR using the appropriate selective AFLP-TP primers (data not shown). The PCR products yielded 1267 good-quality sequences which were used for BLASTN and BLASTX searches against the DFCI Grape Gene Index database (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/cgi-bin/tgi/gimain.pl?gudb=grape) and the UNIPROT database (http://www.expasy.uniprot.org), respectively (see Supplementary Table S2 at JXB online). Gene Ontology terms were assigned to the sequences and were used to organize them into major functional categories (see Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). No matches were found for 225 sequences.

Cluster analysis

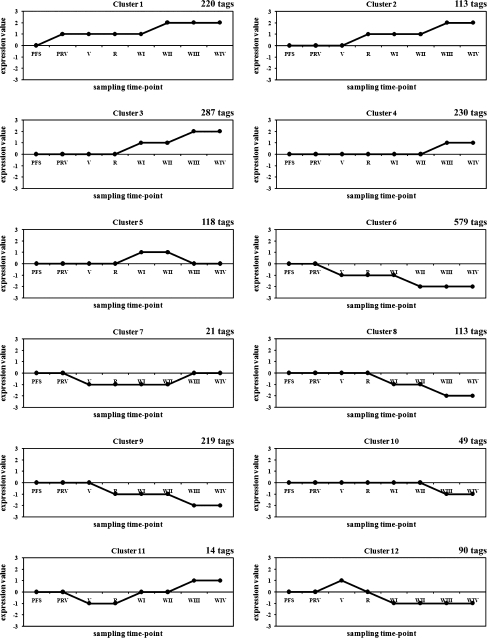

The expression profiles of the 2093 differentially-expressed transcripts were visually scored relative to the first sampling time point which was arbitrarily attributed a zero value. Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed using a Pearson correlation (uncentred) distance and complete linkage clustering based on the scores from the four developmental and four post-harvest (off-plant withering) sampling points. Twelve main clusters were identified and their mean expression profiles are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Expression profiles of the 12 main clusters. The number of AFLP-TP tags belonging to each cluster is reported. For each cluster, the graph reports the mean expression values calculated using expression values of all tags in the cluster over the four development sampling time-points (PFS, PRV, V, and R) and the off-plant withering sampling time-points (WI, WII, and WIII).

Clusters 1 (10.51%) and 2 (6.36%) represent genes induced in early and late development, respectively, whereas clusters 3 (13.71%) and 4 (10.99%) represent genes specifically induced during early and late withering, respectively. Cluster 5 (5.64%) represents genes that are expressed transiently during withering. Clusters 6 (27.66%) and 9 (10.46%) represent genes that are repressed during early and late development, whereas clusters 8 (6.36%) and 10 (2.34%) represent genes that are specifically repressed during early and late withering, respectively. Cluster 7 (1.00%) represents genes that are transiently repressed during ripening and the first stage of withering. Cluster 11 (0.67%) represents genes that are repressed during late berry development but induced at the onset of withering. Finally, cluster 12 (4.3%) is the reciprocal of cluster 11, i.e. genes up-regulated in late development but repressed during withering.

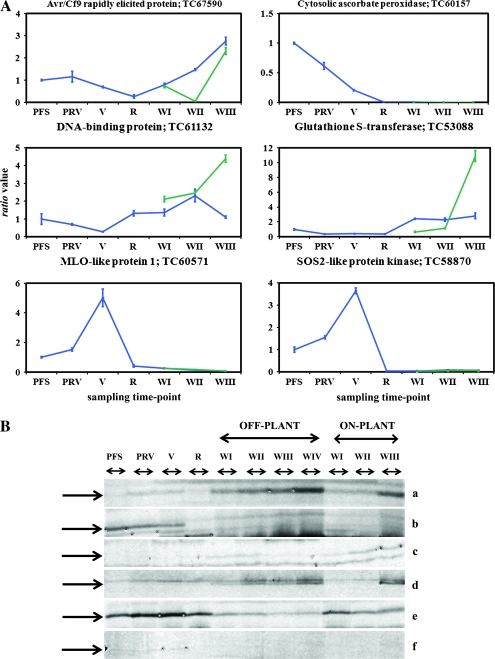

Real-time RT-PCR experiments

The expression profiles of six randomly-selected differentially-expressed genes were confirmed by real-time RT-PCR experiments using the same RNA samples. The analysis was carried out for the four developmental time points (PFS, PRV, V, R) and for the three time points common to both withering processes (WI, WII, WIII) (Fig. 2). The six tags represented an avr9/cf-9 rapidly-elicited protein, a cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase, a DNA-binding protein, a glutathione S-transferase, a MLO-like protein, and an SOS2-like protein kinase. The real-time RT-PCR expression profiles were similar to the profiles obtained by AFLP-TP (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

(A) Real-time RT-PCR expression profiles of six AFLP-TP tags. Gene expression profiles expressed as a ratio value for each sampling time point relative to the post-fruit set (PFS) (±SE, n=3 technical replicates). Solid blue line: gene expression profile for development (PFS, PRV, V, and R) and for the off-plant withering sampling time points (WI, WII, WIII) (circles). Dotted green line: expression profile for the on-plant withering sampling time points (WI, WII, WIII) (triangles). (B) AFLP-TP expression profiles for the six tags analysed by real-time RT-PCR: (a) Avr9/Cf9 rapidly elicited protein, (b) cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase, (c) DNA-binding protein, (d) glutathione S-transferase, (e) MLO-like protein 1, (f) SOS2-like protein kinase. The expression profiles include the four development sampling time-points (PFS, PRV, V, R), the four off-plant sampling time-points (WI, WII, WIII, and WIV) and the three on-plant sampling time-points (WI, WII, and WIII). The off-plant WIV was not analysed by real-time RT-PCR.

Changes in gene expression during off-plant withering

AFLP-TP analysis of grape samples allowed us to identify a number of transcripts specifically modulated during the post-harvest withering process, i.e. those in clusters 3 and 4 (induced during early and late withering, respectively) and clusters 8 and 10 (repressed during early and late withering, respectively). These genes accounted for 33.4% of all differentially expressed transcripts, with an approximate 3:1 ratio of up-regulated to down-regulated genes. For each cluster, a list of tags with homology to sequences with known functions was prepared (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5).

Table 2.

Annotated cDNA-AFLP-TP tags from cluster 3

| Description | Accessiona | E-valueb |

| Secondary metabolic process: phenylpropanoid biosynthetic process | ||

| 4-Coumarate-CoA ligase-like | TC57438 | 6.16E-34 |

| Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | TC66528 | 3.13E-78 |

| Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | TC66528 | 1.83E-77 |

| Secondary metabolic process: lignan metabolic process | ||

| Polyphenol oxidase | TC58764 | 5.46E-68 |

| Polyphenol oxidase | TC58764 | 8.80E-65 |

| Secondary metabolic process: stilbene metabolic process | ||

| Resveratrol synthase | TC52907 | 9.45E-52 |

| Stilbene synthase | TC53668 | 7.85E-10 |

| Stilbene synthase | TC59572 | 2.64E-97 |

| Stilbene synthase | TC52790 | 2.22E-49 |

| Secondary metabolic process: flavonoid metabolic process | ||

| Chalcone-flavonone isomerase | TC55034 | 2.60E-06 |

| Secondary metabolic process: terpenoid metabolic process | ||

| Limonoid UDP-glucosyltransferase | TC65435 | 1.20E-06 |

| Response to stimulus | ||

| Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase | TC51718 | 2.78E-102 |

| Gag-pol polyprotein | TC69867 | 1.08E-35 |

| Glutathione S-transferase GST24 | TC53088 | 6.02E-64 |

| MLO-like protein 6 (AtMlo6) | Q94KB7 | 2.82E-15 |

| MutT domain protein-like | TC67034 | 1.05E-11 |

| Reverse transcriptase | TC51865 | 4.30E-05 |

| Non-LTR retroelement reverse transcriptase | CD007484 | 6.00E-11 |

| Sorbitol related enzyme | TC58983 | 8.86E-28 |

| SRE1a | TC61558 | 4.92E-07 |

| Metabolic process: transcription | ||

| AREB-like protein | TC52653 | 1.54E-32 |

| bZIP transcription factor | TC54438 | 3.29E-19 |

| DNA-binding protein | TC61132 | 2.72E-34 |

| MYBR2 | TC61058 | 7.06E-59 |

| NAM-like protein | TC69267 | 1.77E-10 |

| Transcription factor IIA | TC65001 | 1.15E-69 |

| Metabolic process: translation | ||

| 26S proteosome regulatory subunit | Q6Z8F7 | 1.96E-04 |

| 4.5S. 5S. 16S, and 23S mRNA | TC70523 | 9.94E-37 |

| 60S acidic ribosomal protein | TC60834 | 8.79E-24 |

| Hamamelis virginiana large subunit 26S ribosomal RNA gene | TC65768 | 1.89E-18 |

| Ribosomal S29-like protein | TC65685 | 8.25E-06 |

| RNA binding | TC69367 | 5.46E-26 |

| Metabolic process: protein metabolic process | ||

| COP9 signalosome complex subunit 3 | Q8W575 | 3.51E-03 |

| COP9 signalosome complex subunit 7 | TC52949 | 1.70E-08 |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase | Q8GT86 | 5.73E-06 |

| Phosphatase | TC60297 | 1.49E-58 |

| Proteasome subunit beta type 7-A precursor | TC68818 | 8.50E-06 |

| Ubiquitin | TC53245 | 3.66E-46 |

| Ubiquitin | TC52385 | 3.25E-38 |

| Cellular component organization and biogenesis | ||

| Histone H2A.3 | TC54193 | 2.40E-08 |

| Myosin-like protein | TC57562 | 2.63E-24 |

| Structural maintenance of chromosomes | Q6Q1P4 | 4.55E-04 |

| Topoisomerase-like protein | Q8LDN5 | 6.00E-04 |

| Transport | ||

| ADP, ATP carrier | TC67277 | 7.19E-20 |

| Cytochome b5 | TC52244 | 1.10E-08 |

| Cytochrome B561-like. partial | TC58099 | 1.30E-65 |

| Cytochrome oxidase | TC62100 | 2.00E-06 |

| Cytochrome P450 mono-oxygenase CYP83C | TC61438 | 4.09E-51 |

| Mitochondrial carrier protein | TC63333 | 4.21E-07 |

| Potassium transport 7 | Q9FY75 | 7.77E-23 |

| Probable oxidoreductase At4g09670 | TC63817 | 1.87E-08 |

| Ras-related protein RAB8-5 | TC60446 | 9.08E-31 |

| Syntaxin 43 | TC52593 | 4.69E-08 |

| Metabolic process | ||

| Acetyltransferase | Q9ASS8 | 5.44E-08 |

| Acyl-coenzyme A oxidase, peroxisomal precursor | TC58112 | 2.63E-65 |

| α-Glucan phosphorylase, H isozyme | TC53692 | 3.14E-14 |

| 4.5-DOPA dioxygenase extradiol-like protein. putative | Q6L3J4 | 7.41E-12 |

| γ-Glutamylcysteine synthetase | TC56558 | 1.32E-15 |

| Inositol 1.3.4-trisphosphate 56-kinase | Q1S3P6 | 2.33E-04 |

| Invertase inhibitor-like protein | Q9LSN2 | 3.83E-05 |

| Ketol-acid reductoisomerase, chloroplast precursor | TC68860 | 5.29E-61 |

| Lysophospholipase-like protein | TC56357 | 1.29E-63 |

| NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase PSST subunit | TC64663 | 9.00E-81 |

| Poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase | TC56033 | 1.70E-04 |

| Plastid α-amylase | Q5BLY1 | 1.16E-16 |

| S-adenosyl methionine synthase | TC67664 | 3.10E-05 |

| Solanesyl diphosphate synthase | TC55340 | 5.20E-35 |

| Biological process | ||

| ATP binding | TC63053 | 2.73E-68 |

| Cellular retinaldehyde-binding/triple function. C terminal | TC55679 | 4.28E-30 |

| Cig3 | Q8W417 | 2.01E-59 |

| DNA-binding protein-like | CB009535 | 4.13E-26 |

| Kelch repeat containing F-box protein family-like | TC57688 | 2.96E-18 |

| KH domain-containing protein | TC63964 | 3.30E-07 |

| Latency associated nuclear antigen | TC71005 | 2.18E-40 |

| Legumin-like protein | TC52209 | 1.31E-64 |

| Legumin-like protein | TC52209 | 1.26E-62 |

| NADPH-ferrihaemoprotein reductase | CD007176 | 1.50E-06 |

| RING finger-like protein | CB920519 | 3.18E-38 |

| Ring finger family protein | TC56727 | 7.72E-60 |

| Surfeit 1 homologue | TC70786 | 3.20E-05 |

| Zinc finger protein | Q0KIL9 | 5.56E-16 |

Accession number (DFCI Grape Gene Index, UNIPROT ID).

E-value from BLASTN and BLASTX searches.

Table 3.

Annotated cDNA-AFLP-TP tags from cluster 4

| Description | Accessiona | E valueb |

| Secondary metabolic process: phenylpropanoid biosynthetic process | ||

| 4-Coumarate-CoA ligase-like protein | TC57438 | 3.40E-30 |

| Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | TC69585 | 9.91E-32 |

| Secondary metabolic process: lignan metabolic process | ||

| Dirigent-like protein pDIR14 | TC62196 | 2.02E-55 |

| Secretory laccase | TC54354 | 1.54E-19 |

| Secondary metabolic process: stilbene metabolic process | ||

| Resveratrol synthase | TC52907 | 7.14E-47 |

| Stilbene synthase | NP1227286 | 7.56E-52 |

| Stilbene synthase | TC59572 | 6.24E-99 |

| Stilbene synthase | TC60946 | 3.05E-04 |

| Secondary metabolic process: terpenoid metabolic process | ||

| Limonoid UDP-glucosyltransferase | TC65435 | 1.30E-09 |

| Response to stimulus | ||

| Avr9/Cf-9 rapidly elicited protein | CA813698 | 1.79E-46 |

| Dehydrin 1a | TC61998 | 3.14E-32 |

| Disease resistance response protein | Q9LID5 | 5.29E-35 |

| Syringolide-induced protein | Q8S901 | 6.16E-08 |

| Metabolic process: transcription | ||

| Ethylene response factor | TC52148 | 6.60E-74 |

| Ethylene-responsive element binding protein | TC62980 | 1.25E-04 |

| Eukaryotic initiation factor 4B | Q9M7E8 | 6.90E-26 |

| RING finger-like protein | CB920519 | 1.25E-17 |

| SUPERMAN-like zinc finger protein | TC60860 | 8.85E-16 |

| WRKY6 | TC59548 | 4.10E-08 |

| Metabolic process: translation | ||

| 26S ribosomal RNA | TC70629 | 2.03E-24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S12 | Q9XHS0 | 6.27E-09 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L3 | O65076 | 4.64E-17 |

| Hamamelis virginiana large subunit 26S ribosomal RNA gene | TC65768 | 6.70E-12 |

| Protein synthesis initiation factor 4G | TC67911 | 1.23E-80 |

| Ribosomal protein L3 | Q1RYN6 | 4.39E-17 |

| S15 ribosomal protein | Q8L4R2 | 5.00E-04 |

| Metabolic process: protein metabolic process | ||

| 22.0 kDa class IV heat shock protein precursor | P30236 | 3.09E-04 |

| PLANT UBX DOMAIN-CONTAINING PROTEIN 2 | TC67882 | 5.00E-14 |

| SKP1 | TC57098 | 2.92E-33 |

| Ubiquitin-protein ligase | TC64169 | 3.03E-69 |

| Cellular component organization and biogenesis | ||

| H4 NEUCR Histone H4 | TC52370 | 8.27E-29 |

| Transport | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase | TC55957 | 4.45E-51 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | CB006657 | 4.90E-08 |

| Chloroplast outer membrane protein | Q56WJ7 | 3.00E-10 |

| Copper-transporting P-type ATPase | TC64839 | 4.10E-11 |

| Hexose transporter | Q3L7K6 | 9.00E-12 |

| Major facilitator superfamily MFS 1 | TC61509 | 8.98E-27 |

| Secretion protein HlyD | TC60298 | 9.43E-39 |

| Secretory carrier-associated membrane protein 1 | TC52744 | 5.01E-05 |

| Sucrose transporter-like protein | TC51830 | 3.18E-22 |

| Metabolic process | ||

| Dopamine β-mono-oxygenase N-terminal domain-containing protein | TC62500 | 8.00E-09 |

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | TC54602 | 3.55E-77 |

| LEDI-5c protein | TC61395 | 9.25E-31 |

| Lipoxygenase | Q8GSM3 | 2.03E-04 |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase, cytosolic | TC52072 | 9.61E-102 |

| Plastidic aldolase NPALDP1 | TC59070 | 5.66E-22 |

| Ribose-5-phosphate isomerase | TC59181 | 8.03E-91 |

| Transaldolase | Q8H706 | 3.39E-16 |

| Trehalose-phosphate phosphatase | TC67690 | 1.50E-06 |

| Biological regulation | ||

| Response regulator 6 (TypeA response regulator 9) | TC62852 | 5.97E-41 |

| Biological process | ||

| Calcium-binding allergen | TC63220 | 4.05E-31 |

| Germin-like protein | TC52213 | 2.10E-06 |

| L. esculentum protein with leucine zipper | TC54217 | 2.00E-36 |

Accession number (DFCI Grape Gene Index, UNIPROT ID).

E-value from BLASTN and BLASTX searches.

Table 4.

Annotated cDNA-AFLP-TP tags from cluster 8

| Description | Accessiona | E-valueb |

| Secondary metabolic process: flavonoid metabolic process | ||

| Anthocyanidin-3-glucoside rhamnosyltransferase | TC70498 | 6.46E-37 |

| Response to stimulus | ||

| TMV response-related gene product | TC57457 | 1.00E-40 |

| Thioredoxin domain-containing protein 9 | TC56954 | 5.48E-76 |

| Metabolic process: transcription | ||

| HMG-I and HMG-Y, DNA-binding | Q1RZ01 | 4.61E-06 |

| MYB-like DNA-binding domain protein | TC52565 | 1.89E-08 |

| Putative VP1/ABI3 family regulatory protein | O04346 | 1.03E-11 |

| Similarity to metallothionein-I gene transcription activator | Q9FLM8 | 7.38E-06 |

| Metabolic process: translation | ||

| 30S ribosomal protein S16 | TC53443 | 4.62E-06 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L12 | TC52607 | 7.57E-37 |

| Metabolic process: protein metabolic process | ||

| Pepsin A | TC58741 | 1.15E-43 |

| Probable prefoldin subunit 5 | TC58696 | 5.13E-72 |

| Putative tyrosine phosphatase | Q5ZEJ0 | 3.53E-22 |

| S-locus receptor-like kinase RLK14 | CB971388 | 7.50E-06 |

| Transport | ||

| ADP ribosylation factor 002 | TC51848 | 1.18E-68 |

| Putative cytochrome b5 | O22704 | 2.79E-25 |

| Receptor-like protein kinase-like | TC54030 | 9.74E-71 |

| Metabolic process | ||

| Acyl-ACP thioesterase | TC60833 | 6.76E-17 |

| α-Glucan water dikinase | TC54189 | 2.23E-45 |

| ATP/GTP nucleotide-binding protein | Q9FII8 | 4.00E-06 |

| β-Mannan endohydrolase | TC67062 | 2.80E-05 |

| B-keto acyl reductase | TC53435 | 9.70E-10 |

| C-type cytochrome biogenesis protein | TC68921 | 8.01E-08 |

| CDP-diacylglycerol–glycerol-3-phosphate 3-phosphatidyltransferase | TC64058 | 4.87E-06 |

| Diaminopimelate decarboxylase | TC68200 | 2.71E-64 |

| HMG-CoA synthase 2 | TC68763 | 1.22E-22 |

| Ketol-acid reductoisomerase, chloroplast precursor | TC68860 | 4.77E-61 |

| Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase | TC59981 | 9.30E-31 |

| Molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis | TC70221 | 9.50E-43 |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | TC60028 | 5.57E-41 |

| Photosystem I reaction center subunit N, chloroplast precursor | TC53444 | 2.58E-56 |

| Pyrophosphate-dependent phosphofructo-1-kinase | TC70414 | 1.91E-100 |

| Ribonuclease HII | Q53QG3 | 2.41E-06 |

| Transaldolase ToTAL2 | TC59186 | 1.24E-14 |

| Biological process | ||

| CaLB protein | P92940 | 1.00E-07 |

| Cellular retinaldehyde-binding/triple function, C terminal | TC55679 | 3.20E-14 |

| Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor | TC52886 | 1.27E-50 |

| DREPP4 | TC70411 | 3.58E-37 |

| Fasciclin-like AGP-12 | TC51953 | 1.50E-30 |

| Nucleotide binding | TC67441 | 7.32E-08 |

| RNA binding | TC62986 | 7.15E-68 |

| tRNA-Ala tRNA-Ile 16S rRNA tRNA-Val rps12 rps7 ndhB | TC60315 | 6.60E-36 |

| WD-40 repeat family protein-like | TC52339 | 2.41E-32 |

Accession number (DFCI Grape Gene Index, UNIPROT ID).

E-value from BLASTN and BLASTX searches.

Table 5.

Annotated cDNA-AFLP-TP tags from cluster 10

| Description | Accessiona | E-valueb |

| Response to stimulus | ||

| Putative metallophosphatase | Q8VXF6 | 5.33E-25 |

| Thioredoxin-like protein | TC63581 | 1.84E-43 |

| Metabolic process: transcription | ||

| MADS-box transcripion factor | TC51812 | 2.76E-04 |

| Metabolic process: protein metabolic process | ||

| Serine/threonine protein phosphatase BSL2 homologue | Q2QM47 | 1.40E-12 |

| Cellular component organization and biogenesis | ||

| Actin-like | TC58881 | 3.14E-09 |

| Cellulose synthase-like protein CslG | TC55634 | 1.56E-13 |

| Transport | ||

| ATP synthase γ chain | TC68806 | 3.78E-76 |

| Metabolic process | ||

| Acyl-CoA thioesterase | TC55739 | 1.29E-48 |

| Carbonate dehydratase | O81875 | 8.36E-10 |

| Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine | Q84XV9 | 1.42E-20 |

| Pyruvate kinase | TC60979 | 1.01E-55 |

| S-adenosyl methionine synthase-like | TC62371 | 7.03E-20 |

| Biological process | ||

| Coenzyme Q biosynthesis protein | TC70287 | 1.71E-23 |

| Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase | CB918027 | 1.74E-14 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1-like | TC62660 | 3.06E-33 |

| Neurofilament-H related protein | CD801715 | 6.50E-07 |

Accession number (DFCI Grape Gene Index, UNIPROT ID).

E-value from BLASTN and BLASTX searches.

Analysis of the AFLP-TP transcripts specifically modulated during berry dehydration allowed a model for the molecular processes that take place after berry picking to be formulated.

Phenolic compounds

Among the AFLP tags induced by withering, there were three transcripts with homology to two different phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) genes (TC69585; TC66528), and two tags encoding 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL)-like proteins (TC57438) (Tables 2, 3). Therefore, berry dehydration appears to induce general phenylpropanoid metabolism, which generates precursors for many different categories of phenolic compounds. Eight tags corresponding to STS genes (TC52790, TC52907, TC53668, TC59572, TC60946, NP1227286) were induced by withering (Tables 2, 3) suggesting a strong stilbene production. Stilbenes are synthesized constitutively in seeds and are also produced in berry skin during development, and in response to biotic or abiotic stresses (Soleas et al., 1997). Significant resveratrol accumulation occurs during the post-harvest drying of berries of many grape cultivars, and this has already been linked to the high-level expression of stilbene synthase (STS) (Celotti et al., 1998; Tornielli, 1998; Versari et al., 2001). Given that STS is also induced during on-plant withering (see Supplementary Table S2 at JXB online), these results indicate that the induction of the expression of many STS genes is a characteristic of the berry post-ripening phase.

Among the up-regulated withering-specific transcripts, one chalcone isomerase (CHI) gene (TC55034) and two tags homologous to polyphenol oxidase (TC52784) (Table 2) were identified (Table 2). The transcriptional profile of the first gene suggests an activation of the flavonoid pathway during the withering process, while the transcriptional profile of the second one indicates a probable oxidation/polymerization of phenolic compounds.

Few previous studies have considered the production of phenolics in grape skin during the post-harvest drying process, and there is some conflict about the abundance of such compounds, with some reports citing a general reduction (Di Stefano et al., 1997; Borsa and Di Stefano, 2000) and others a general increase (Bellincontro et al., 2004; Tornielli et al., 2005). Taken together, these results suggest that, in addition to the stilbene synthesis, some classes of flavonoids may also be produced during the withering process.

Small- and large-scale gene expression studies have already been performed on grapes under preharvest water-deficit stress (Castellarin et al., 2007a, b; Grimplet et al., 2007). Preharvest water-deficit stress does not necessary cause a cell osmotic stress in berry tissues which is likely to occur during the post-harvest dehydration process analysed in this work. Although physiological events associated with pre- and post-harvest developmental stages are different, a similar positive modulation of genes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway in lignin and stilbene biosynthesis was observed in skin tissues of ripening berries in response to water-deficit stress (Grimplet et al., 2007), and during berry post-harvest withering. On the other hand, preharvest water stress accelerated ripening and induced the expression of flavonoid structural genes during berry development (Castellarin et al., 2007a, b), while the water stress caused by dehydration characterizing the off-plant withering had a minor influence on the flavonoid pathway.

Terpenoid compounds

Terpenoids contribute to the aroma of grapes and their products including wine (Lund and Bohlmann, 2006). AFLP-TP showed that two transcripts with homology to a limonoid UDP-glucosyltransferase (TC65435) were induced during the post-harvest drying (Tables 2, 3). In citrus fruits, limonoid UDP-glucosyl transferase catalyses the conversion of bitter tasting limonin to limonoid glucoside (Kita et al., 2000). There is no evidence for the presence of limonin in grape berries, but it is possible that this gene is involved in the modification of other terpenes or in the production of secondary metabolites and hormones (Kita et al., 2000).

A tag representing hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase (TC68763) was shown to be repressed during withering (Table 4). This enzyme is involved in the synthesis of hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA), which can be converted into isoprenoids via the mevalonate pathway (Sirinupong et al., 2005). These data suggest that the late terpene biosynthetic pathway is up-regulated whereas the production of terpene precursors is inhibited. A repression at ripening of a transcript encoding a key enzyme of the non-mevalonate IPP biosynthetic pathway, the 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase was reported in grape berries under water-deficit stress (Grimplet et al., 2007).

Cell wall metabolism

Previous reports have described the expression patterns of cell wall-modifying enzymes during berry development and ripening, as well as concomitant changes in cell wall composition (Nunan et al., 1998, 2001; Vidal et al., 2001; Doco et al., 2003; Grimplet et al., 2007). There is no direct evidence for modification of the berry cell wall structure and composition during off-plant drying, but the increase in polyphenolic compounds reported in some studies (Tornielli et al., 2005; Pinelo et al., 2006) might depend on cell wall degradation. AFLP-TP analysis revealed the down-regulation of only two withering-specific tags putatively involved in cell wall metabolism, encoding a cellulose synthase (TC55634) and a β-mannan endohydrolase (TC67062) (Tables 4, 5).

Response to stress

It has recently been shown that berry ripening results in the accumulation of transcripts related to biotic and abiotic stress responses (Deluc et al., 2007; Pilati et al., 2007). Among the withering-specific AFLP-TP tags, there were transcripts encoding a gag-pol polyprotein (TC69867), a non-LTR reverse transcriptase (CD007484), and a reverse transcriptase (TC51865) (Table 2). These data suggest that an increase in transposable element activity is one component of the stress response to berry withering. Many transposable elements have been identified in the grapevine genome (Verriès et al., 2000; Pelsy et al., 2002; Pereira et al., 2005; French-Italian Public Consortium for Grapevine Genome Characterization, 2007; Velasco et al., 2007) and cis-acting sequences in the LTR of elements Tnt1, Tto1, and Vine-1 could be involved in the activation of defence genes in response to stress conditions (Grandbastien, 1998; Verriès et al., 2000).

Dehydration is likely to be the major stress factor affecting grape berries after harvest, since they lose over 30% of their weight through evaporation during off-plant ripening (Table 1). The up-regulation of DHN1a, encoding dehydrin 1a (TC61998), and of a trehalose-phosphate phosphatase mRNA (TC67690) (Table 3), supports this theory, since plant dehydrins counteract the water stress that occurs in cold, frost, drought, and saline conditions (Sanchez-Ballesta et al., 2004; Rorat, 2006). In Vitis riparia and in V. vinifera, DHN1a is induced in response to cold, drought, and ABA treatment (Xiao and Nassuth, 2006). This gene could protect the berry during the late withering stages, together with the increased production of trehalose by trehalose-phosphate phosphatase (Table 3) since increased trehalose levels protect Escherichia coli from stress including drought (Garg et al., 2002). The up-regulation of a sorbitol related enzyme (TC58983) (Table 2) could positively affect the synthesis of this sugar with a protective role against water stress in plant (Tao et al., 1995).

One transcript encoding a lipoxygenase (Q8GSM3), an enzyme involved in the synthesis of C6 volatile compounds and signalling molecules that respond to stress (Croft et al., 1993), was isolated among the tags specifically induced in late withering (Table 3). During Malvasia grape berry drying, an increase in lipoxygenase activity and the concomitant production of C6 compounds such as hexen-1-ol, hexanal, and (E)-hex-2-enal was reported (Costantini et al., 2006).

It has been suggested that grape ripening, unlike tomato and strawberry, is not accompanied by the induction of oxidative stress response genes (Terrier et al., 2005). However, an oxidative burst characterized by H2O2 accumulation duration véraison and by the modulation enzymes that scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) was recently described during berry development (Pilati et al., 2007). The AFLP-TP analysis identified two tags, encoding a cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase (TC51718) and a glutathione S-transferase (TC53088), which were up-regulated during post-harvest drying (Table 2). This suggests that the post-ripening phase is characterized by oxidative stress and the corresponding response. Such response may not require the involvement of two thioredoxin-like proteins given that the corresponding transcripts (TC56954; TC63581) were down-regulated during withering (Tables 4, 5).

Despite the absence of pests and diseases, several genes involved in biotic stress responses were also induced during withering, including the STS genes discussed above. Other early-induced genes identified by AFLP-TP analysis included transcripts homologous to Arabidopsis thaliana MLO-like protein 6 (Q94KB7) and potato systemic acquired resistance-related protein SRE1a (TC61558) (Table 2). The involvement of MLO proteins in resistance to powdery mildew was reported in barley (Peterhänsel and Lahaye, 2005). Delayed induction was observed for other defence gene tags including those related to A. thaliana Avr9/Cf-9 rapidly elicited protein (CA813698) (Durrant et al., 2000), soybean syringolide-induced protein (Q8S901) which is induced in soybean cells treated with Pseudomonas syringae elicitors (Hagihara et al., 2004) and an A. thaliana disease resistance response protein (Q9LID5) (Table 3). A TMV response-related gene product (TC57457) was shown to be repressed during withering (Table 4).

Genes related to the general stress response, such as a sorbitol related enzyme, an Avr9/Cf-9 rapidly elicited protein, and a disease resistance gene were also induced in ripening berries of grape plants in water-deficit conditions (Grimplet et al., 2007).

Carbohydrate transport and metabolism

Our AFLP-TP experiment showed that VvHT5 (Q3L7K6), which encodes a hexose transporter (HT) located in the plasma membrane (Hayes et al., 2007), is up-regulated late in the withering process (Table 3). This indicates that hexose transport, reported to be strongly active during ripening (Hayes et al., 2007), is probably also active during withering. Such activity may be responsible for the transport of sugars in different subcellular compartments.

The solute concentration in ripening berries increases in part due to water loss (Costantini et al., 2006; Di Stefano et al., 1997), but reactions related to hexose aerobic/anaerobic respiration, hexose conversion to malate, gluconeogenesis, and malate respiration might also increase during post-harvest drying (Zironi and Ferrarini, 1987; Bellincontro et al., 2006; Chkaiban et al., 2007).

The analysis showed that transcripts encoding glycolytic enzymes like aldolase (TC54602; TC59070) and phosphoglycerate kinase (TC52072) were up-regulated (Table 3), whereas a pyruvate kinase (TC60979) was repressed (Table 5) along with phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (TC60028), which is involved in gluconeogenesis (Table 4). Taken together these results suggest that hexoses could be metabolized via the pyruvate pathway or conversion into malate, even if no transcripts directly involved in the latter pathway were identified, while de novo synthesis of such compounds seems to be inhibited.

Ethylene metabolism

Berry development is characterized by a weak spike in ethylene production around véraison with a concomitant increase in the activity of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid oxidase, the enzyme responsible for the last step of ethylene biosynthesis (Chervin et al., 2004). Exogenous ethylene application affects the production of phenols and anthocyanins, and influences the aromatic quality of Aleatico berries, so ethylene is likely to be involved in the post-harvest withering process (Bellincontro et al., 2006). AFLP-TP analysis revealed the up-regulation of S-adenosyl methionine synthase (TC67664) (Table 2), which supports such a role.

Grimplet et al. (2007) also provides evidence of the induction of genes involved in ethylene biosynthesis and signalling in grape berry development and ripening under water-deficit stress conditions.

Transcription factors

Several transcription factor genes matched to the withering-specific AFLP-TP tags (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5). These included an up-regulated transcript related to a tobacco bZIP transcription factor (TC54438) (Table 2) that binds in vitro to G-box elements in the promoters of phenylpropanoid biosynthetic genes (Heinekamp et al., 2002). The putative grapevine homologue could potentially bind similar elements upstream of grapevine genes, such as those identified in the Vst1 and DFR promoters (Schubert et al., 1997; Gollop et al., 2002). Another induced transcript was homologous to the apple MYBR2 factor (TC61058) (Table 2). In plants, MYB proteins regulate different cellular and developmental processes including secondary metabolism, cellular morphogenesis, and the response to growth regulators (Martin and Paz-Ares, 1997). In grapevine, the role of MYB proteins in the regulation of phenylpropanoid synthesis has been considered (Deluc et al., 2006, 2008; Bogs et al., 2007; Walker et al., 2007). The up-regulation of a transcript displaying homology to the Nicotiana attenuata WRKY6 factor (TC59548) was also observed (Table 3). This could be linked to the activation stress response genes, as observed in numerous plant species in the case of wounding, pathogen infection or abiotic stress (Ulker and Somssich, 2004).

Among the withering-specific genes, the transcript for grapevine MADS1 (TC51812) was repressed (Table 5). This MADS-box transcription factor may play a role in flower development before fertilization and in berry development after fertilization (Boss et al., 2001).

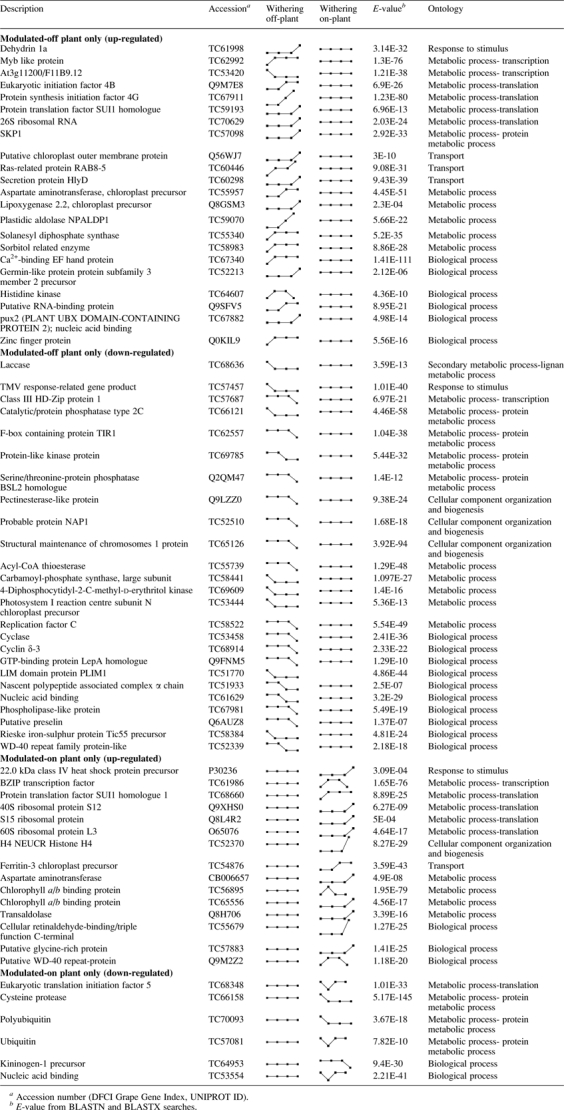

On-plant and off-plant withering processes

Transcriptional modulation during grape berry post-harvest ripening was also studied in bunches that were left attached to the plant in the vineyard. AFLP-TP analysis was carried out on overripe berries and the results were compared with those obtained from the off-plant withering in order to highlight major differences caused by attachment to the shoot.

Off-plant withered berries were characterized by significant water loss and increased sugar concentration, whereas there was negligible water loss and little sugar accumulation in the on-plant berries (Table 1). A comparative analysis of AFLP-TP expression profiles from the three shared sampling time points identified 167 transcripts that were modulated only during off-plant withering, while another 86 transcripts were modulated only during the on-plant process. Thus, only 253 tags with different transcription profile were detected on the whole. This comparative analysis suggests that common transcriptional changes characterize the two kinds of withering processes. This seems surprising for a non-climacteric fruit such as grape berry, in which the occurrence of different processes on-plant and off-plant could be hypothesized. Differences in gene expression seem to be due mainly to dehydration stress, occurring in the off-plant withering process. A list of tags homologous to sequences with a known function is provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Annotated AFLP-TP tags specific for on-plant and off-plant withering

|

One notable difference between the two processes was the higher level of VvDHN1a in off-plant withered berries, which almost certainly reflects off-plant water loss and the role of VvDH1a in dehydration stress. A similar profile was observed for a transcript with homology to a tomato enzyme involved in sorbitol biosynthesis (Ohta et al., 2005). There were no major differences in genes involved in cell wall metabolism. However, tags encoding a pectinesterase-like protein (Q9LZZ0) and a laccase (TC68636) were down-regulated specifically in off-plant withered berries (Table 6).

Pectinesterase is involved in the process of fruit softening during ripening (Prasanna et al., 2007), and this would appear less important in off-plant withered berries as would the polymerization of monolignols by laccase (Sterjiades et al., 1992). Possible down-regulation of cell wall lignification during the off-plant process is also supported by the repression of a tag homologous to a poplar Class III HD-Zip protein 1 (TC57687) (Table 6) which plays a role in wood formation (Ko et al., 2006). A putative glycine-rich protein was up-regulated in the on-plant withered berries, and such proteins also play a role in cell wall structure (Mousavi and Hotta, 2005).

In off-plant withered berries, a tag with homology to the A. thaliana NAP1 (TC52510) protein was repressed (Table 6). NAP1 helps to regulate the activity of the ARP3/3 complex, which controls actin polymerization, suggesting that on-plant withering may require the preservation of actin polymers (Brembu et al., 2004).

With respect to energy metabolism, transcripts involved in photosynthesis were down-regulated in off-plant withered berries, for example, the photosystem I reaction centre subunit N chloroplast precursor (TC53444). However, a tag matching solanesyl diphosphate synthase (TC55340) was up-regulated (Table 6). In A. thaliana, this enzyme is involved in the synthesis of the isoprenoid component of plastoquinone and ubiquinone (Jun et al., 2004), which take part in photosynthetic electron transfer in the chloroplast and respiratory electron transfer in the mitochondrion (Jun et al., 2004). Chlorophyll a/b binding proteins (TC56895; TC65556) were up-regulated in on-plant withered berries (Table 6).

There were some differences between the two processes in terms of protein synthesis, with both induction and repression noted for tags corresponding to various ribosomal proteins and translation factors (Table 6). However, on-plant withering appeared to repress genes involved in protein recycling, such as polyubiquitin (TC70093) and ubiquitin (TC57081) (Table 6).

In terms of secondary metabolism, only genes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis showed any major differences between the post-harvest drying processes with the repression of a tag encoding a 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase (TC69609), an enzyme belonging to the mevalonate-independent pathway, in off-plant withered grapes (Table 6).

Conclusion

AFLP-TP analysis allowed genes to be identified whose steady-state mRNA levels were modulated during post-harvest withering, painting a broad picture of the transcriptional events underpinning post-harvest berry withering in the Corvina variety. The results must be evaluated considering the 2003 growing season as particularly hot and dry. Dehydration, the main stress that occurs during off-plant withering, triggers a number of different responses including the activation of canonical stress-response genes, the accumulation of osmolytes and the mobilization of transposable elements. The berry withering process could also be characterized in terms of the synthesis of phenolic and terpene compounds, ethylene biosynthesis, and hexose catabolism via the pyruvate pathway. Genes were also identified whose expression differed according to the type of withering process (on or off the vine), indicating that off-plant withering induced a deeper form of dehydration stress and induced the high level expression of stress response genes such as those encoding dehydrins and osmolyte biosynthetic enzymes. This experiment has made a significant contribution to understanding the molecular basis of grape berry withering and may help to identify useful markers for different withering processes.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data can be found at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Major functional categories of the differentially-expressed AFLP-TP tags.

Table S1. Sequences of real-time RT-PCR primers.

Table S2. Complete list of the AFLP-TP transcripts modulated during berry development, off-plant and on-plant withering.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Project ‘BACCA’ granted by the ORVIT Consortium, by the Project ‘Centro di Genomica Funzionale Vegetale’ granted by CARIVERONA Bank Foundation, and by the Project: ‘Structural and functional characterization of the grapevine genome (Vigna)’ granted by the Italian Ministry of Agricultural and Forestry Policies (MIPAF). LM is supported by a grant from Pasqua Vini e Cantine. The authors thank the ‘Centro Sperimentale Provinciale per la Vitivinicoltura’ Provincia di Verona for allowing us to sample material from their vineyard.

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellincontro A, De Santis D, Botondi R, Villa I, Mencarelli F. Different post-harvest dehydration rates affect quality characteristics and volatile compounds of Malvasia, Trebbiano and Sangiovese grape for wine production. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2004;84:1791–1800. [Google Scholar]

- Bellincontro A, Fardelli A, De Santis D, Rotondi R, Mencarelli F. Post-harvest ethylene and 1-MCP treatments both affect phenols, anthocyanins, and aromatic quality of Aleatico grapes and wine. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2006;12:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bogs J, Jaffé FW, Takos AM, Walker AR, Robinson SP. The grapevine transcription factor VvMYBPA1 regulates proanthocyanidin synthesis during fruit development. Plant Physiology. 2007;143:1347–1361. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.093203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsa D, Di Stefano R. Evoluzione dei polifenoli durante l'appassimento di uve a frutto colorato. Rivista Viticoltura Enolologia. 2000;4:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Boss PK, Vivier M, Matsumoto S, Dry IB, Thomas MR. A cDNA from grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.), which shows homology to AGAMOUS and SHATTERPROOF, is not only expressed in flowers but also throughout berry development. Plant Moecularl Biology. 2001;45:541–553. doi: 10.1023/a:1010634132156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brembu T, Winge P, Seem M, Bones AM. NAPP and PIRP encode subunits of a putative wave regulatory protein complex involved in plant cell morphogenesis. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:2335–2349. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.023739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breyne P, Dreesen R, Cannoot B, Rombaut D, Vandepoele K, Rombauts S, Vanderhaeghen R, Inzé D, Zabeau M. Quantitative cDNA-AFLP analysis for genome-wide expression studies. Molecular Genetics and Genomics: MGG. 2003;269:173–179. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0830-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellarin SD, Matthews MA, Di Gaspero G, Gambetta GA. Water deficits accelerate ripening and induce changes in gene expression regulation flavonoid biosynthesis in grape berries. Planta. 2007b;227:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0598-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellarin SD, Pfeiffer A, Sivilotti P, Degan M, Peterlunger E, Di Gaspero G. Transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in ripening fruit of grapevine under seasonal water deficit. Plant, Cell and Enviroment. 2007a;30:1381–1399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celotti E, Ferrarini R, Conte LS, Giulivo C, Zironi R. Modifiche del contenuto di resveratrolo in uve di vitigni della Valpolicella nel corso della maturazione e dell'appassimento. Vignevini. 1998;5:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chervin C, El-Kereamy A, Roustan JP, Latché A, Lamon J, Bouzayen M. Ethylene seems required for the berry development and ripening in grape, a non-climacteric fruit. Plant Science. 2004;167:1301–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Chkaiban L, Botondi R, A de Santis D, Kefalas P. Influence of post-harvest water stress on lipoxygenase and alcohol dehydrogenase activities, and on the composition of some volatile compounds of Gewürztraminer grapes dehydrated under controlled and uncontrolled thermohygrometric conditions. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2007;13:142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Conde C, Silva P, Fontes N, Dias ACP, Tavares RM, Sousa MJ, Agasse A, Delrot S, Geros H. Biochemical changes throughout grape berry development and fruit and wine quality. Food. 2007;1:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini V, Bellincontro A, De Santis D, Botondi R, Mencarelli F. Metabolic changes of Malvasia grapes for wine production during post-harvest drying. Journal of Agriultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54:3334–3340. doi: 10.1021/jf053117l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft K, Juttner F, Slusarenko AJ. Volatile products of the lipoxygenase pathway evolved from Phaseolus vulgaris (L.) leaves inoculated with Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola. Plant Physiology. 1993;101:13–24. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deluc L, Barrieu F, Marchive C, Lauvergeat V, Decendit A, Richard T, Carde JP, Mérillon JM, Hamdi S. Characterization of a grapevine R2R3-MYB transcription factor that regulates the phenylpropanoid pathway. Plant Physiology. 2006;140:499–511. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.067231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deluc L, Bogs J, Walker AR, Ferrier T, Decendit A, Merillon JM, Robinson SP, Barrieu F. The transcription factor VvMYB5b contributes to the regulation of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in developing grape berries. Plant Physiology. 2008 doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118919. 10.1104/pp.108.118919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deluc LG, Grimplet J, Wheatley MD, Tillett RL, Quilici DR, Osbone C, Schooley DA, Schlauch KA, Cushman JC, Cramer GR. Trancriptomic and metabolite analyses of Cabernet Sauvignon grape berry development. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:429. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano R, Borsa D, Gentilini N, Corino L, Tronfi S. Evoluzione degli zuccheri, degli acidi fissi e dei composti fenolici dell'uva durante l'appassimento in fruttaio. [Evolution of sugars, acids and phenolic compounds of grape during drying in fruttaio] Rivista Viticoltura Enologia. 1997;1:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Doco T, Williams P, Pauly M, O'Neill MA, Pellerin P. Polysaccharides from grape berry cell wall. II. Structural characterization of the xyloglucan polysaccharides. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2003;53:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Durrant WE, Rowland O, Piedras P, Hammond-Kosack KE, Jones JD. cDNA-AFLP reveals a striking overlap in race-specific resistance and wound response gene expression profiles. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:963–977. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French-Italian Public Consortium for Grapevine Genome Characterization. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg AK, Kim JK, Owens TG, Ranwala AP, Choi YD, Kochian LV, Wu RJ. Trehalose accumulation in rice plants confers high tolerance levels to different abiotic stresses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2002;99:15898–15903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252637799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollop R, Even S, Colova-Tsolova V, Perl A. Expression of the grape dihydroflavonol reductase gene and analysis of its promoter region. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53:1397–1409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandbastien MA. Activation of plant retrotrasposons under stress conditions. Trends Plant Science. 1998;3:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Grimplet J, Deluc LG, Tillett RL, Wheatley MD, Schlauch KA, Cramer GR, Cushman JC. Tissue-specific mRNA expression profiling in grape berry tissues. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara T, Hashi M, Takeuchi Y, Yamaoka N. Cloning of soybean genes induced during hypersensitive cell death caused by syringolide elicitor. Planta. 2004;218:606–614. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1136-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MA, Davies C, Dry IB. Isolation, functional characterization, and expression analysis of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) hexose transporters: differential roles in sink and source tissues. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:1985–1997. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinekamp T, Kuhlmann M, Lenk A, Strathmann A, Dröge-Laser W. The tobacco bZIP transcription factor BZI-1 binds to G-box elements in the promoters of phenylpropanoid pathway genes in vitro, but it is not involved in their regulation in vivo. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2002;267:16–26. doi: 10.1007/s00438-001-0636-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao TC. Plant responses to water stress. Annual Review of Plant Physiology. 1973;24:519–570. [Google Scholar]

- Jun L, Saiki R, Tatsumi K, Nakagawa T, Kawamukai M. Identification and subcellular localization of two solanesyl diphosphate synthases from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2004;45:1882–1888. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kays SJ. Stress in harvested products. In: Kays SJ, editor. Post-harvest physiology in perishable plants products. Exon Press; 1997. pp. 335–408. [Google Scholar]

- Kita M, Hirata Y, Moriguchi T, Endo-Inagaki T, Matsumoto R, Hasegawa S, Suhayda CG, Omura M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel gene encoding limonoid UDP-glucosyltransferase in Citrus. FEBS Letters. 2000;469:173–178. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JH, Prassinos C, Han KH. Developmental and seasonal expression of PtaHB1, a Populus gene encoding a class III HD-Zip protein, is closely associated with secondary growth and inversely correlated with the level of microRNA (miR166) The New Phytologist. 2006;169:469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund ST, Bohlmann J. The molecular basis for wine grape quality: a volatile subject. Science. 2006;311:804–805. doi: 10.1126/science.1118962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund ST, Peng FY, Nayar T, Reid KE, Schlosser J. Gene expression analyses in individual grape (Vitis vinifera L.) berries during ripening initiation reveal that pigmentation intensity is a valid indicator of developmental staging within the cluster. Plant Molecular Biology. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9371-z. 10.1007/s11103–008–9371-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Paz-Ares J. MYB transcription factors in plants. Trends in Genetics. 1997;13:67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(96)10049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi A, Hotta Y. Glycine-rich proteins: a class of novel proteins. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2005;120:169–174. doi: 10.1385/abab:120:3:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunan KJ, Davies C, Robinson SP, Fincher GB. Expression patterns of cell wall modifying enzymes during grape berry. Planta. 2001;214:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s004250100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunan KJ, Sims IM, Bacic A, Robinson SP, Fincher GB. Changes in cell wall composition during ripening of grape berries. Plant Physiology. 1998;118:783–792. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.3.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta K, Moriguchi R, Kanahama K, Yamaki S, Kanayama Y. Molecular evidence of sorbitol dehydrogenase in tomato, a non-Rosaceae plant. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2822–2828. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelsy F, Merdinoglu D. Complete sequence of Tvv1, a family of Ty 1 copia-like retrotransposons of Vitis vinifera L., reconstituted by chromosome walking. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2002;105:615–621. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-0969-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira HS, Barão A, Delgado M, Morais-Cecílio L, Viegas W. Genomic analysis of Grapevine Retrotransposon 1 (Gret 1) in Vitis vinifera. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2005;111:871–878. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterhänsel C, Lahaye T. Be fruitful and multiply: gene amplification inducing pathogen resistance. Trends in Plant Science. 2005;10:257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilati S, Perazzolli M, Malossini A, Cestaro A, Demattè L, Fontana P, Dal Ri A, Viola R, Velasco R, Moser C. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of grapevine berry ripening reveals a set of genes similarly modulated during three seasons and occurrence of an oxidative burst at veraison. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:428. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinelo M, Arnous A, Meyer AS. Upgrading of grape skins: significance of plant cell-wall structural components and extraction techniques for phenol release. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2006;17:579–590. [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna V, Prabha TN, Tharanathan RN. Fruit ripening phenomena-an overview. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2007;47:1–19. doi: 10.1080/10408390600976841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers C, Ruijter JM, Deprez RH, Moorman AF. Assumption-free analysis of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) data. Neuroscience Letters. 2003;339:62–66. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos IN, Silva CLM, Sereno AM, Aguilera JM. Quantification of microstructural changes during first stage air drying of grape tissue. Journal of Food Engineering. 2004;62:159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaian MA, Krake LR. Nucleic acid extraction and virus detection in grapevine. Journal of Virological Methods. 1987;17:277–285. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(87)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorat T. Plant dehydrins: tissue location, structure and function. Cellular and Molecular Biology Letters. 2006;11:536–556. doi: 10.2478/s11658-006-0044-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Ballesta MT, Rodrigo MJ, Lafuente MT, Granell A, Zacarias L. Dehydrin from citrus, which confers in vitro dehydration and freezing protection activity, is constitutive and highly expressed in the flavedo of fruit but responsive to cold and water stress in leaves. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2004;52:1950–1957. doi: 10.1021/jf035216+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert R, Fischer R, Hain R, Schreier PH, Bahnweg G, Ernst D, Sandermann H., Jr An ozone-responsive region of the grapevine resveratrol synthase promoter differs from the basal pathogen-responsive sequence. Plant Molecular Biology. 1997;34:417–426. doi: 10.1023/a:1005830714852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirinupong N, Suwanmanee P, Doolittle RF, Suvachitanont W. Molecular cloning of a new cDNA and expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase gene from Hevea brasiliensis. Planta. 2005;221:502–512. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleas GJ, Diamandis EP, Goldberg DM. Resveratrol: a molecule whose time has come? And gone? Clinical Biochemistry. 1997;30:91–113. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(96)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterjiades R, Dean JF, Eriksson KE. Laccase from sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) polymerizes monolignols. Plant Physiology. 1992;99:1162–1168. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.3.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R, Uratsu SL, Dandekar AM. Sorbitol synthesis in transgenic tobacco with apple cDNA encoding NADP-dependent sorbitol-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1995;36:525–532. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a078789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrier N, Glissant D, Grimplet J, et al. Isogene specific oligo arrays reveal multifaceted changes in gene expression during grape berry (Vitis vinifera L.) development. Planta. 2005;222:832–847. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonutti P, Tornelli GB, Cargnello G. Proceedings of an international conference on viticultural zoning. Cape-Town (South Africa): 2004. Characterization of ‘territories’ throughout the production of wine obtained with withered grapes: the cases of ‘Terra della Valpolicella’ (Verona) and ‘Terra del Piave’ (Treviso) in Northern Italy. November 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tornielli GB. Evoluzione di alcuni composti fenolici durante la maturazione e appassimento dell'uva. PhD thesis. Padua University, Italy; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tornielli GB, Spinelli P, Simonato B, Ferrarini R. American Society for Enology and Viticulture 56th Annual Meeting. Effect of different environmental conditions on berry polyphenols during post-harvest dehydration of grapes. Seattle (Washington-US), June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ulker B, Somssich IE. WRKY transcription factors: from DNA binding towards biological function. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2004;7:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco R, Zharkikh A, Troggio M, et al. A high quality draft consensus sequence of the genome of a heterozygous grapevine variety. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verriès C, Bès C, This P, Tesnière C. Cloning and characterization of Vine-1, a LTR-retrotransposon-like element in Vitis vinifera L., and other Vitis species. Genome. 2000;43:366–376. doi: 10.1139/g99-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versari A, Parpinello GP, Tornielli GB, Ferrarini R, Giulivo C. Stilbene compounds and stilbene synthase expression during ripening, wilting, and UV treatment in grape cv. Corvina. Journal of Agriultural and Food Chemistry. 2001;49:5531–5536. doi: 10.1021/jf010672o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal S, Williams P, O'Neill MA, Pellerin P. Polysaccharides from grape berry cell wall. I. Tissue distribution and structural characterization of the pectic polysaccharides. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2001;45:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Vuylsteke M, Peleman JD, van Eijk MJ. AFLP-based transcript profiling (cDNA-AFLP) for genome-wide expression analysis. Nature Protocols. 2007;2:1399–1413. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AR, Lee E, Bogs J, McDavid DA, Thomas MR, Robinson SP. White grapes arose through the mutation of two similar and adjacent regulatory genes. The Plant Journal. 2007;49:772–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters DLE, Holton TA, Ablett EM, Lee LS, Henry RJ. cDNA microarray analysis of developing grape (Vitis vinifera cv. Shiraz) skin. Functional and Integrative Genomics. 2005;5:40–58. doi: 10.1007/s10142-004-0124-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Nassuth A. Stress- and development-induced expression of spliced and unspliced transcripts from two highly similar dehydrin 1 genes in V. riparia and V. vinifera. Plant Cell Reports. 2006;25:968–977. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zironi R, Ferrarini R. La surmaturazione delle uve destinate alla vinificazione. Vignevini. 1987;4:31–45. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.