Abstract

Motivation: While text mining technologies for biomedical research have gained popularity as a way to take advantage of the explosive growth of information in text form in biomedical papers, selecting appropriate natural language processing (NLP) tools is still difficult for researchers who are not familiar with recent advances in NLP. This article provides a comparative evaluation of several state-of-the-art natural language parsers, focusing on the task of extracting protein–protein interaction (PPI) from biomedical papers. We measure how each parser, and its output representation, contributes to accuracy improvement when the parser is used as a component in a PPI system.

Results: All the parsers attained improvements in accuracy of PPI extraction. The levels of accuracy obtained with these different parsers vary slightly, while differences in parsing speed are larger. The best accuracy in this work was obtained when we combined Miyao and Tsujii's Enju parser and Charniak and Johnson's reranking parser, and the accuracy is better than the state-of-the-art results on the same data.

Availability: The PPI extraction system used in this work (AkanePPI) is available online at http://www-tsujii.is.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/-100downloads/downloads.cgi. The evaluated parsers are also available online from each developer's site.

Contact: yusuke@is.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

1 INTRODUCTION

Text mining has recently emerged as a way to harvest specific pieces of information from the rapidly growing body of biomedical literature. While the use of shallow text processing techniques is now common for tasks such as the identification of proteins and other entities in biomedical papers (Kim et al., 2004; Yeh et al., 2005), researchers are now addressing more complex tasks, such as the identification of protein–protein interactions (PPI), using advanced natural language parsing approaches that analyze the syntactic and semantic structure of text (Bunescu et al., 2005; Hirschman et al., 2007; Nédellec, 2005; Pyysalo et al., 2007a). However, parsing natural language is an intricate endeavor, where a wide range of possible approaches and open research questions exist, making the choice of a natural language parsing component a burden for researchers without close familiarity with current trends in natural language processing (NLP). Through a series of experiments, we investigate different aspects of state-of-the-art parsing approaches that affect practical performance of information extraction in biomedical papers. Although accuracy figures for different parsers are commonly reported in the NLP literature, such figures are usually computed using artificial metrics that, while useful for parser development, may not be indicative of overall task performance when the parser is used as a component in a biomedical text mining system.

Due to the creation of biomedical treebanks (Kulick et al., 2004; Tateisi et al., 2005) and rapid progress of data-driven parsers (Nivre et al., 2007), there are now fast, robust and accurate syntactic parsers for text in the biomedical domain. Recent research shows that the accuracy for parsing of biomedical text is now in the 80–90% range (Clegg and Shepherd, 2007; Pyysalo et al., 2007b; Sagae et al., 2008a). However, to be of interest outside the parsing or computational linguistics communities, such accurate syntactic analysis must be shown to improve the performance of overall systems that perform meaningful tasks with biomedical data. This has started to happen, for example, in the task of automatically identifying PPI described in scientific papers. Intuitively, syntactic relationships between words should be valuable in determining possible interactions between entities present in text. Recent PPI extraction systems have confirmed this intuition (Airola et al., 2008; Erkan et al., 2007; Fundel et al., 2007; Katrenko and Adriaans, 2006; Kim et al., 2008; Miyao et al., 2008; Sætre et al., 2007; Sagae et al., 2008b).

While, it is now relatively clear that syntactic parsing is useful in information extraction from the large natural language corpora in bioinformatics, several questions remain regarding the benefits and costs of different parsing approaches and different syntactic representations: how syntactic analyses should be used in a practical setting, whether further improvements in parsing technologies will result in further improvements in practical systems, and how much effort should be spent on comparing and benchmarking parsers for biomedical data. We attempt to shed some light on these matters by performing a comparative evaluation of state-of-the-art syntactic parsers based on different frameworks: dependency parsing, phrase structure parsing and deep parsing. Our approach to parser evaluation is to measure accuracy improvement in the task of identifying PPI information in biomedical papers, by incorporating the output of different parsers as statistical features in a machine learning classifier (Erkan et al., 2007; Katrenko and Adriaans, 2006; Sætre et al., 2007; Yakushiji et al., 2005). PPI identification is an informative task for parser evaluation, since it is a biomedical information extraction application of practical utility, and because recent studies have shown the effectiveness of syntactic parsing in this task. Since our evaluation method is applicable to any parser output, and is grounded in a real application, it allows for a fair comparison of syntactic parsers based on different frameworks. In addition, we present experiments that show the relationship of the accuracy of parsers and the accuracy of the larger PPI system that includes the parser. We investigate the effects of domain-specific treebank size (the amount of available manually annotated training data for syntactic parsers) and final system performance, and obtain results that should be informative to researchers in bioinformatics who deal with natural language, as well as to members of the parsing community who are interested in the practical impact of parsing research in biomedical applications.

2 NATURAL LANGUAGE PARSERS

This article focuses on eight representative parsers that are classified into three parsing frameworks: dependency parsing, phrase structure parsing and deep parsing.

2.1 Dependency parsing

Dependency parsing has recently been extensively studied in parsing research, partly because the shared tasks of CoNLL 2006 and 2007 focused on data-driven dependency parsing (Nivre et al., 2007). The aim of dependency parsing is to compute a tree structure of a sentence, where nodes are words and edges represent the relationships among the words.

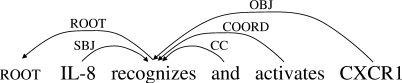

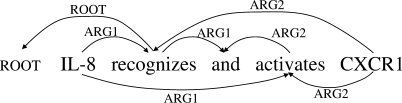

Figure 1 shows a parsing result for the sentence ‘IL-8 recognizes and activates CXCR1’, in the dependency tree format used in the 2006 and 2007 CoNLL shared tasks on dependency parsing (which we call the ‘CoNLL’ format). An advantage of dependency parsing is that dependency trees are a reasonable approximation of the semantics of sentences, and are readily usable in NLP applications. For example, the subject and the object of ‘recognizes’ are explicitly represented in this format. Furthermore, the efficiency of dependency parsing compares favorably to phrase structure parsing or deep parsing. While a number of methods have been proposed for dependency parsing, this article focuses on the following two representative parsers.

Fig. 1.

CoNLL-X dependency tree (CoNLL).

MST: McDonald and Pereira's (2006) dependency parser (http://sourceforge.net/projects/mstparser) based on Eisner's (1996) algorithm for projective dependency parsing.

KSDEP: Sagae and Tsujii's (2007) dependency parser, (http://www.cs.cmu.edu/sagae/parser/), based on a probabilistic shift-reduce algorithm.

2.2 Phrase structure parsing

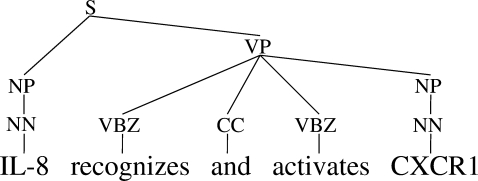

Owing largely to the Penn Treebank (Marcus et al., 1994), the mainstream of data-driven parsing research has been dedicated to phrase structure parsing. These parsers output Penn Treebank-style phrase structure trees (which we call the ‘PTB’ format), as shown in Figure 2. While most state-of-the-art phrase structure parsers are based on probabilistic context-free grammars (PCFGs), the parameterization of the probabilistic model of each parser varies. In this work, we chose the following four parsers.

Fig. 2.

Penn Treebank-style phrase structure tree (PTB).

NO-RERANK: Charniak's (2000) parser, based on a lexicalized PCFG model of phrase structure trees (http://bllip.cs.brown.edu/resources.shtml). The probabilities of CFG rules are parameterized on carefully hand-tuned information, such as lexical heads and symbols of ancestor/sibling nodes.

RERANK: Charniak and Johnson's (2005) reranking parser. The reranker of this parser receives n-best1 parse results from NO-RERANK, and selects the most likely parse result by using a maximum entropy model with manually engineered features.

BERKELEY: Berkeley's parser (Petrov and Klein 2007) (http://nlp.cs.berkeley.edu/Main.html#Parsing). The parameterization of this parser is optimized automatically by assigning latent variables to each non-terminal node and estimating the parameters of the latent variables by the expectation maximization algorithm.

STANFORD: Stanford's unlexicalized parser (Klein and Manning, 2003) (http://nlp.stanford.edu/software/lex-parser.shtml). Unlike NO-RERANK, probabilities are not parameterized on lexical heads.

Since the PTB format does not directly represent the grammatical functions between words, it is difficult to use it directly in applications. In Figure 2, it is not clear how the syntactic arguments (e.g. the subject and the object) of verbs are identified. An ordinary solution is the conversion of PTB trees into some form of dependency-based representations. This article adopts three representations that can be converted from PTB trees.

CoNLL: while this representation is the default output for dependency parsers, it can also be obtained from the PTB format by applying constituent-to-dependency conversion (http://nlp.cs.lth.se/pennconverter/).(Johansson and Nugues, 2007). It should be noted, however, that this conversion cannot work perfectly with automatic parsing, because the conversion program relies on additional information (function tags and empty categories) of the original Penn Treebank, which are not produced by the parsers listed above.

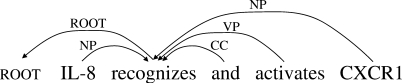

HD: dependency trees of syntactic heads (Fig. 3). We first determine lexical heads of non-terminal nodes by using Collins' head detection algorithm (http://www.cis.upenn.edu/dbikel/software.html (Bikel, 2004). We then convert lexicalized trees into dependencies between lexical heads. This format can represent dependency relations similar to CoNLL, although relation types are not sufficient to identify important grammatical relations. For example, in Figure 3, the subject and the object relations are assigned the same relation types, NP, and are not distinguishable.

Fig. 3.

Head dependencies (HD).

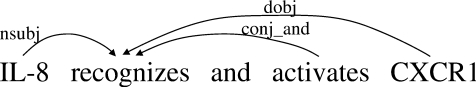

SD: the Stanford dependency format (Fig. 4). This format was originally proposed for extracting dependency relations useful for practical applications (de Marneffe et al., 2006). A program to convert PTB is attached to the Stanford parser. Although the concept looks similar to CoNLL, this representation does not necessarily form a tree structure, and is designed to express more fine-grained relations, such as apposition. In Figure 4, ‘nsubj’ and ‘dobj’ indicate the nominal subject and direct object, which are more fine-grained relation types than CoNLL dependencies. Research groups for biomedical NLP recently adopted this representation for corpus annotation (Pyysalo et al., 2007a) and parser evaluation (Clegg and Shepherd, 2007; Pyysalo et al., 2007b).

Fig. 4.

Stanford dependencies (SD).

2.3 Deep parsing

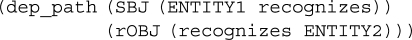

Deep parsing aims to compute in-depth syntactic and semantic structures based on syntactic theories, such as HPSG (Pollard and Sag, 1994). Recent research developments have allowed for efficient and robust deep parsing of real-world texts (Miyao and Tsujii, 2008). Deep parsers can compute theory-specific syntactic/semantic structures, and predicate argument structures (PAS) that are often used in parser evaluation and applications. PAS is a graph structure that represents the relations among words (Fig. 5). The concept is therefore similar to CoNLL dependencies, though PAS expresses deeper relations, such as long distance dependencies, and may include shared structures. For example, the subject (ARG1) and the object (ARG2) of ‘activates’ are explicitly represented in Figure 5, while not in the other formats.

Fig. 5.

Predicate argument structure (PAS).

In this work, we used two variants of the Enju parser (Miyao and Tsujii, 2008) (http://www-tsujii.is.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/enju/).

ENJU: an HPSG-based parser derived from the Penn Treebank.

ENJU-GENIA: a variant of ENJU, which is adapted to biomedical texts, by the method of (Hara et al. 2007).

In addition to the PAS format, the PTB format can also be created from Enju's output by using tree structure matching (Matsuzaki and Tsujii, 2008), but this conversion is imperfect because the forms of PTB and Enju's output are not entirely compatible. We can also obtain the CoNLL.HD and SD formats, because they can be converted from PTB. That is, five parse representations are available for the Enju parser.

3 METHODS

In our approach to parser evaluation, we measure the accuracy of a PPI extraction system, in which the parser output is embedded as statistical features of a machine learning classifier. We run the classifier with features of every possible combination of a parser and a parse representation, by applying conversions between representations when necessary.

3.1 PPI extraction

PPI extraction is an information extraction task to identify protein pairs that are mentioned as interacting in biomedical papers. Because the number of biomedical papers is growing rapidly, it is becoming difficult for biomedical researchers to find all papers relevant to their research; thus, there is an emerging need for reliable text mining technologies, such as automatic PPI extraction from texts.

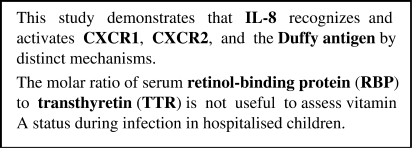

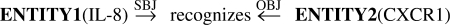

Figure 6 shows two sentences that include protein names: the former sentence mentions a protein interaction, while the latter does not. Given a protein pair, PPI extraction is a task of binary classification; for example, 〈IL-8, CXCR1〉 is a positive example, and 〈RBP, TTR〉 is a negative example. Recent studies on PPI extraction demonstrated that syntactic/semantic relationships between target proteins are effective features for machine learning classifiers (Erkan et al., 2007; Katrenko and Adriaans, 2006; Sætre et al., 2007). For the protein pair IL-8 and CXCR1 in Figure 6, a dependency parser outputs a dependency tree; partly shown in Figure 1. From this dependency tree, we can extract the dependency path shown in Figure 7, which appears to be a strong clue in knowing that these proteins are mentioned as interacting.

Fig. 6.

Sentences including protein names.

Fig. 7.

Dependency path.

We follow the PPI extraction method of (Sætre et al. 2007), which is based on support vector machines with SubSet Tree Kernels (Moschitti, 2006), while using different parsers and parse representations. Two types of features are incorporated in the classifier. The first is bag-of-words features, which are regarded as a strong baseline for PPI extraction systems. Lemmas of words before, between and after the pair of target proteins are included, and a linear kernel is used for these features. This kernel is included in all our models. The other type of feature is parser output features. For dependency-based parse representations, a dependency path is encoded as a flat tree as depicted in Figure 8 (prefix ‘r’ denotes reverse relations). Because a tree kernel measures the similarity of trees by counting common subtrees, it is expected that the system finds effective subsequences of dependency paths. For the PTB representation, we directly encode phrase structure trees.

Fig. 8.

Tree representation of a dependency path.

We also measure the accuracy obtained by the ensemble of two parsers/representations. This experiment indicates differences or overlaps in the information conveyed by two different parsers or parse representations.

3.2 Conversion of parser output representations

It is widely believed that the choice of the representation format for parser output may greatly affect the performance of applications, although this has not been extensively investigated. We should, therefore, evaluate the parser performance in multiple parse representations. In this article, we create multiple parse representations by converting each parser's default output into other representations when possible. This experiment can also be considered to be a comparative evaluation of parse representations, thus providing an indication for selecting an appropriate parse representation for similar information extraction and text mining tasks.

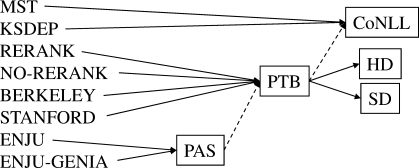

Table 1 lists the formats for parser output used in this work, and Figure 9 shows our scheme for representation conversion. Although only CoNLL is available for dependency parsers, we can create four representations for the phrase structure parsers, and five for the deep parsers. Dotted arrows in Figure 9 indicate imperfect conversion, in which the conversion inherently introduces errors, and may decrease the accuracy. We should, therefore, take caution when comparing the results obtained by imperfect conversion.

Table 1.

Parser output representations

| CoNLL | Dependency trees used in CoNLL 2006 and 2007 |

| PTB | Penn Treebank-style phrase structure trees |

| HD | Dependency trees of lexical heads |

| SD | Stanford dependency graphs |

| PAS | Predicate argument structures |

Fig. 9.

Conversion of parser output representations.

3.3 Parser retraining with GENIA

The domain of our target text is different from the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) portion of the Penn Treebank, which is the de facto standard data for parser training. Because all the parsers listed in Section sec:syntactic_parsers were originally trained with the WSJ data (except for ENJU-GENIA), we retrain the parsers with the GENIA Treebank2 (8127 sentences), which is a treebank of biomedical paper abstracts annotated according to the guideline of the Penn Treebank (Tateisi et al., 2005). Since all these parsers have programs for training with a PTB-style treebank, we use those programs for retraining with default parameter settings.

In preliminary experiments, we found that dependency parsers attain higher dependency accuracy when trained only with GENIA. We therefore use only GENIA as the training data for the retraining of dependency parsers. For the other parsers, we use the concatenation of WSJ and GENIA for the retraining, while the reranker of RERANK was not retrained due to the high cost. Also for the training of ENJU-GENIA, the same set of the WSJ and GENIA was used.

Since all the parsers except NO-RERANK and RERANK require an external POS tagger, geniatagger.(Tsuruoka et al., 2005) is used with these parsers.

3.4 Evaluating the relationships between parser accuracy, treebank size and PPI accuracy

In addition to investigating the impact of different parsers and different syntactic representations on PPI identification accuracy, we also examine how the parse accuracy of a single parser affects the PPI accuracy. To this end, we retrain one of the parsers (KSDEP) with varying amounts of training text, resulting in several different versions of the same parser, having different levels of accuracy. This allows us to establish a relationship between the accuracy of the parser and the amount of training data used to create the parser. When the parser is used as a component in the PPI identification system, we can determine the relationship between the size of the dataset used to train the parser, the parser's accuracy, and the overall PPI system's accuracy. This provides a rough guide for what level of accuracy to expect in the PPI task when a new parser is used, as long as the accuracy of the parser is known.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Data

In the following experiments, we used AIMed (Bunescu and Mooney, 2004), which is a popular dataset for the evaluation of PPI extraction systems. The data consists of 225 biomedical paper abstracts (1970 sentences), which are sentence-split, tokenized and annotated with proteins and PPIs. We use the gold protein annotations given in the data, and multi-word protein names are concatenated and treated as single words. The accuracy is measured by abstract-wise 10-fold cross-validation and the one-answer-per-occurrence criterion (Giuliano et al., 2006). A prediction threshold for the support vector machine (SVM) is moved to adjust the balance of precision and recall, and the maximum f-score is reported for each experiment.

4.2 Comparison of accuracy improvements

Table 2 shows the time used by each parser for parsing the entire AIMed corpus, and the PPI accuracy obtained by using the output from each parser with different parse representation. The row ‘baseline’ indicates the accuracy obtained with bag-of-words features only.

Table 2.

Parsing time and accuracy (precision/recall/f -score) on the PPI task

| Time (s) | CoNLL | PTB | HD | SD | PAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST | 425 | 49.1/65.6/55.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| KSDEP | 111 | 51.6/67.5/58.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| NO-RERANK | 1372 | 53.9/60.3/56.8 | 51.3/54.9/52.8 | 53.1/60.2/56.3 | 54.6/58.1/56.2 | N/A |

| RERANK | 2125 | 52.8/61.5/56.6 | 48.3/58.0/52.6 | 52.1/60.3/55.7 | 53.0/61.1/56.7 | N/A |

| BERKELEY | 1198 | 52.7/60.3/56.0 | 48.0/59.9/53.1 | 54.9/54.6/54.6 | 50.5/63.2/55.9 | N/A |

| STANFORD | 1645 | 49.3/62.8/55.1 | 44.5/64.7/52.5 | 49.0/62.0/54.5 | 54.6/57.5/55.8 | N/A |

| ENJU | 727 | 54.4/59.7/56.7 | 48.3/60.6/53.6 | 56.7/55.6/56.0 | 54.4/59.3/56.6 | 52.0/63.8/57.2 |

| ENJU-GENIA | 821 | 56.4/57.4/56.7 | 46.5/63.9/53.7 | 53.4/60.2/56.4 | 55.2/58.3/56.5 | 57.5/59.8/58.4 |

| Baseline | 48.2/54.9/51.1 | |||||

Table 2 clearly shows that all the parsers achieved better results than the baseline, demonstrating contributions of these parsers to PPI extraction. Differences among parsers are relatively smaller than the differences from the baseline, proving that dependency parsing, phrase structure parsing and deep parsing perform equally well in this task. Among these parsers, KSDEP and ENJU-GENIA performed better than the other parsers, and NO-RERANK.RERANK and ENJU come next.

While the accuracy level of PPI extraction is similar, parsing speed differs considerably for different parsing frameworks. The dependency parsers are much faster than the other parsers, while the phrase structure parsers are relatively slower, and the deep parsers are in between. It is noteworthy that the dependency parsers achieved comparable accuracy with the other parsers, while they are more efficient.

The experimental results also demonstrate that the PTB format is worse than the other representations with respect to contributions to accuracy improvements. Although phrase structure parsers are popular in the NLP community, dependency-based formats are shown to contribute more to this task, probably because they express syntactic/semantic relations among words more explicitly, as shown in Figure 7. The conversion from PTB to dependency-based representations is, therefore, desirable for this task, although it is possible that better results might be obtained with PTB if a different feature extraction mechanism is used. Among dependency-based representations.HD is slightly worse, indicating that surface syntactic relations are insufficient for this task. It should be noted that CoNLL attained competitive or superior performance to HD and SD in spite of the imperfect conversion from PTB to CoNLL. This might be a reason for the high performances of the dependency parsers that directly compute CoNLL dependencies. The results for ENJU-CoNLL and ENJU-PAS show that PAS contributes to a larger accuracy improvement than the CoNLL representation. This result implies that, deep relations, such as long-distance dependencies, might contribute to accuracy improvements, although this does not necessarily mean the superiority of PAS to CoNLL, because two imperfect conversions, i.e.PAS-to-PTB and PTB-to-CoNLL, are applied for creating ENJU-CoNLL.

4.3 Parser ensemble results

Table 3 shows the accuracy obtained with ensembles of two parsers/representations (excluding the PTB format). Bracketed figures denote improvements from the accuracy with only the single best (of the two) parser/representation used. The results show that the task accuracy improves when using a double parser/representation ensemble. Interestingly, the accuracy improvements are observed even for ensembles of different representations from the same parser. This indicates that a single parse representation is insufficient for expressing the true potential of a parser. Effectiveness of combining two parsers is also attested by the fact that it resulted in larger improvements. Especially, large improvements were observed when ENJU-PAS is combined with another parser/representation. This indicates that the ENJU-PAS format expresses different information from others, and differences in information conveyed by these parsers/representations complementarily contributed to accuracy improvement. The best accuracy was achieved by the combination of ENJU-PAS and RERANK-CoNLL. Further investigation of the sources of these improvements will illustrate the advantages and disadvantages of these parsers and representations, leading us to better parsing models and a better design for parse representations.

Table 3.

Results of parser/representation ensemble (f -score)

| RERANK CoNLL | HD | SD | ENJU CoNLL | HD | SD | PAS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KSDEP | CoNLL | 58.5 (+0.2) | 57.1 (-1.2) | 58.4 (+0.1) | 58.5 (+0.2) | 58.0 (-0.3) | 59.1 (+0.8) | 59.0 (+0.7) |

| RERANK | CoNLL | 56.7 (+0.1) | 57.1 (+0.4) | 58.3 (+1.6) | 57.3 (+0.7) | 58.7 (+2.1) | 59.5 (+2.3) | |

| HD | 56.8 (+0.1) | 57.2 (+0.5) | 56.5 (+0.5) | 56.8 (+0.2) | 57.6 (+0.4) | |||

| SD | 58.3 (+1.6) | 58.3 (+1.6) | 56.9 (+0.2) | 58.6 (+1.4) | ||||

| ENJU | CoNLL | 57.0 (+0.3) | 57.2 (+0.5) | 58.4 (+1.2) | ||||

| HD | 57.1 (+0.5) | 58.1 (+0.9) | ||||||

| SD | 58.3 (+1.1) |

4.4 The impact of treebank size and parser accuracy

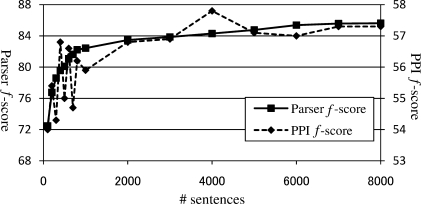

Figure 10 shows the parse accuracy for KSDEP and the accuracy of PPI extraction, when the parser is trained with varying amounts of data. This figure demonstrates that increasing the size of the parser training set contributes to increasing parse accuracy. Training the parser with only 100 sentences results in parse accuracy of about 72.5%. Accuracy rises sharply with additional training data until the size of the training set reaches about 1000 sentences (about 82.5% accuracy). From there, accuracy climbs consistently, but slowly, until 85.6% accuracy is reached with 8000 sentences of training data.

Fig. 10.

Parser training set size (number of sentences) versus parse accuracy and PPI extraction accuracy (f-score).

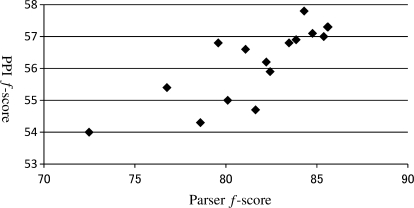

Figure 10 also shows the relationship between the amount of parser training data and the accuracy of PPI extraction. This shows that the accuracy of PPI extraction generally increases with the use of more sentences to train the parser. Although it may appear that further increasing the training data for the parser may not improve the PPI extraction accuracy, we see that the two curves match each other to a large extent. This is supported by the strong correlation between parse accuracy and PPI accuracy, shown in Figure 11. While this suggests that training the parser with a larger treebank may result in improved accuracy in PPI extraction, we observe that a 1% absolute improvement in parser accuracy corresponds roughly to a 0.25 improvement in PPI extraction accuracy. Our results suggest that to obtain even a 1% improvement in parser accuracy by using more parser training data, the size of the treebank used for training would have to increase greatly.

Fig. 11.

Parser accuracy (f-score) versus PPI extraction accuracy (f-score).

4.5 Comparison with previous results on PPI extraction

PPI extraction experiments on AIMed have been reported repeatedly, although the figures cannot be compared directly because of the differences in data preprocessing and the number of target protein pairs (Airola et al., 2008; Sætre et al., 2007). Table 4 compares our best result with previously reported accuracy figures. Among these, (Giuliano et al. 2006) and (Mitsumori et al. 2006) do not rely on natural language parsing, while the former applied SVMs with kernels on surface strings and the latter is similar to our baseline method. (Bunescu and Mooney 2005) applied SVMs with subsequence kernels to the same task, although they provided only a precision–recall graph, and its maximum f-score is around 50. Since we did not run experiments on protein-pairwise cross-validation, our system cannot be compared directly to the results reported by (Erkan et al. 2007) and (Katrenko and Adriaans 2006), but (Sætre et al. 2007) presented better results than theirs using protein-pairwise cross-validation.

Table 4.

Comparison with previous results on PPI extraction (f -score)

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have presented our attempts to evaluate contributions of natural language parsers and their representations to PPI extraction. The basic idea is to measure the accuracy improvements of the PPI extraction task by incorporating the parser output as statistical features of a machine learning classifier. Experiments showed that state-of-the-art parsers improved PPI extraction accuracy, and the obtained accuracy is better than previously reported accuracy on the same data. These parsers attain accuracy levels that are on par with each other, while parsing speed differs considerably. We also observed that a 1% absolute improvement in parser accuracy corresponds roughly to a 0.25% point improvement in PPI extraction accuracy.

A shortcoming of our experiments is that there is no guarantee that the results obtained with our PPI extraction system can be generalized to other dataset and tasks. Although we cannot assert the superiority of parsers/representations under arbitrary cricumstances with only the results presented here, our methodology lays the foundation for future task-based evaluations using different PPI dataset and possibly other information extraction tasks. Such evaluations are indispensable for a more general understanding of the performance characteristics of different parsers in specific applications in bioinformatics, and our methodology provides a template for how these evaluations may be conducted.

Funding: This work was partially supported by Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (MEXT, Japan); Genome Network Project (MEXT, Japan); Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (MEXT, Japan).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Footnotes

1We set n=50 in this article.

2The domains of GENIA and AIMed are not exactly the same, because they are collected independently from PubMed.

References

- Airola A, et al. Proceedings of BioNLP. Columbus; 2008. A graph kernel for protein-protein interaction extraction. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bikel DM. Intricacies of Collins' parsing model. Comput. Linguist. 2004;30:479–511}. [Google Scholar]

- Bunescu R, Mooney RJ. Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Barcelona: 2004. Collective information extraction with relational markov networks. pp. 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Bunescu RC, Mooney RJ. Proceedings of the 19th Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Vancouver: 2005. Subsequence kernels for relation extraction. [Google Scholar]

- Bunescu RC, et al. Comparative experiments on learning information extractors for proteins and their interactions. Artif. Intell. Med. 2005;33:139–155. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charniak E. Proceedings of the First Conference on North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Seattle: 2000. A maximum-entropy-inspired parser. pp. 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Charniak E, Johnson M. Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Ann Arbor; 2005. Coarse-to-fine n-best parsing and MaxEnt discriminative reranking. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg AB, Shepherd AJ. Benchmarking natural-language parsers for biological applications using dependency graphs. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Marneffe M-C, et al. Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation. Genoa: 2006. Generating typed dependency parses from phrase structure parses. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner JM. Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. Copenhagen: 1996. Three new probabilistic models for dependency parsing: an exploration. [Google Scholar]

- Erkan G, et al. Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning. Prague: 2007. Semi-supervised classification for extracting protein interaction sentences using dependency parsing. [Google Scholar]

- Fundel K, et al. RelEx — relation extraction using dependency parse trees. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:365–371. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano C, et al. Proceedings of the 11th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Trento; 2006. Exploiting shallow linguistic information for relation extraction from biomedical literature. [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, et al. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Parsing Technology. Prague: 2007. Evaluating impact of re-training a lexical disambiguation model on domain adaptation of an HPSG parser. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman L, et al., editors. Proceeding of Second BioCreative Challenge Evaluation Workshop. Madrid: Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson R, Nugues P. Proceedings of the 16th Nordic Conference of Computational Linguistics. Tartu: 2007. Extended constituent-to-dependency conversion for English. [Google Scholar]

- Katrenko S, Adriaans P. Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Knowledge Discovery and Emergent Complexity in Bioinformatics. Ghent: 2006. Learning relations from biomedical corpora using dependency trees. pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-D, et al. Proceedings of the Joint Workshop on Natural Language Processing in Biomedicine and its Applications. Geneva: 2004. Introduction to the bio-entity recognition task at JNLPBA. pp. 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, et al. Kernel approaches for genic interaction extraction. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:118–126. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D, Manning CD. Proceedings of the 41st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Sapporo: 2003. Accurate unlexicalized parsing. [Google Scholar]

- Kulick S, et al. Proceedings of Biolink 2004: Linking Biological Literature, Ontologies and Databases. Granada: 2004. Integrated annotation for biomedical information extraction. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus M, et al. Building a large annotated corpus of English: The Penn Treebank. Comput. Linguist. 1994;19:313–330. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki T, Tsujii J. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Computational Linguistics. Manchester: 2008. Comparative parser performance analysis across grammar frameworks through automatic tree conversion using synchronous grammars. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Pereira F. Proceedings of the 11th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Trento: 2006. Online learning of approximate dependency parsing algorithms. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsumori T, et al. Extracting protein-protein interaction information from biomedical text with SVM. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2006;E89-D:2464–2466. [Google Scholar]

- Miyao Y, Tsujii J. Feature forest models for probabilistic HPSG parsing. Comput. Linguist. 2008;34:35–80. [Google Scholar]

- Miyao Y, et al. Proceedings of the 46th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Columbus; 2008. Task-oriented evaluation of syntactic parsers and their representations. [Google Scholar]

- Moschitti A. Proceedings of the 11th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Trento: 2006. Making tree kernels practical for natural language processing. [Google Scholar]

- Nédellec C. Proceedings of the Fourth Learning Language in Logic Workshop. Bonn: 2005. Learning language in logic — genic interaction extraction challenge. [Google Scholar]

- Nivre J, et al. Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning. Prague: 2007. The CoNLL 2007 shared task on dependency parsing. pp. 915–932. [Google Scholar]

- Petrov S, Klein D. Proceedings of the Human Language Technologies: The Annual Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Rochester: 2007. Improved inference for unlexicalized parsing. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard C, Sag IA. Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pyysalo S, et al. BioInfer: a corpus for information extraction in the biomedical domain. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007a;8:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyysalo S, et al. Proceedings of BioNLP. Prague: 2007b. On the unification of syntactic annotations under the Stanford dependency scheme: a case study on BioInfer and GENIA. pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sætre R, et al. Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Languages in Biology and Medicine. Singapore: 2007. Syntactic features for protein-protein interaction extraction. [Google Scholar]

- Sagae K, Tsujii J. Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning. Prague: 2007. Dependency parsing and domain adaptation with LR models and parser ensembles. [Google Scholar]

- Sagae K, et al. the Workshop on Automated Syntatic Annotations for Interoperable Language Resources. Hong Kong: 2008a. Challenges in mapping of syntactic representations for framework-independent parser evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Sagae K, et al. Proceedings of the ACL-08 workshop on Software Engineering, Testing, and Quality Assurance for Natural Language Processing. Columbus; 2008b. Evaluating the effects of treebank size in a practical application for parsing. [Google Scholar]

- Tateisi Y, et al. Proceedings of the Second International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing: Companion Volume Including Posters/Demos and Tutorial Abstracts. Jeju; 2005. Syntax annotation for the GENIA corpus. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruoka Y, et al. 10th Panhellenic Conference on Informatics. Volos: 2005. Developing a robust part-of-speech tagger for biomedical text. [Google Scholar]

- Yakushiji A, et al. First International Symposium on Semantic Mining in Biomedicine. Hinxton: 2005. Biomedical information extraction with predicate-argument structure patterns. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh A, et al. BioCreAtIvE task 1A: gene mention finding evaluation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6(Suppl. 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]