Abstract

Motivation: Yeast two-hybrid screens are an important method to map pairwise protein interactions. This method can generate spurious interactions (false discoveries), and true interactions can be missed (false negatives). Previously, we reported a capture–recapture estimator for bait-specific precision and recall. Here, we present an improved method that better accounts for heterogeneity in bait-specific error rates.

Result: For yeast, worm and fly screens, we estimate the overall false discovery rates (FDRs) to be 9.9%, 13.2% and 17.0% and the false negative rates (FNRs) to be 51%, 42% and 28%. Bait-specific FDRs and the estimated protein degrees are then used to identify protein categories that yield more (or fewer) false positive interactions and more (or fewer) interaction partners. While membrane proteins have been suggested to have elevated FDRs, the current analysis suggests that intrinsic membrane proteins may actually have reduced FDRs. Hydrophobicity is positively correlated with decreased error rates and fewer interaction partners. These methods will be useful for future two-hybrid screens, which could use ultra-high-throughput sequencing for deeper sampling of interacting bait–prey pairs.

Availability: All software (C source) and datasets are available as supplemental files and at http://www.baderzone.org under the Lesser GPL v. 3 license.

Contact: joel.bader@jhu.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Two-hybrid experiments have been widely used to identify pairwise protein–protein interactions. Genome-wide screens have been performed for viruses (Uetz et al., 2006), yeast (Ito et al., 2001; (Uetz et al., 2000), worm (Li et al., 2004), fly (Giot et al., 2003) and recently human (Rual et al., 2005; Stelzl et al., 2005). Related split-ubiquitin screens have been developed for membrane proteins (Johnsson and Varshavsky, 1994; Stagljar et al., 1998). Protein-fragment complementation assays can provide higher resolution structural information (Tarassov et al., 2008). These screens provide valuable insights into how proteins are organized into pathways and functional networks.

Interactions identified by two-hybrid experiments can have low reproducibility and low coverage (Bader and Chant, 2006). High-confidence datasets from two experiments for yeast (Ito et al., 2001; Uetz et al., 2000) have only 9% overlap. Independent datasets reported for human (Rual et al., 2005; Stelzl et al., 2005) have almost no overlap. False positives and false negatives can both be responsible for small overlap, but are confounding factors whose contributions can be difficult to deconvolute. Furthermore, false positives and false negatives arise for both technical and biological reasons.

False positives include both ‘technical’ false positives, those that are not reliably recovered under identical experimental conditions, and ‘biological’ false positives, which are reliably recovered in a particular experimental system but do not occur in vivo. Methods that rely on data from a single type of experiment inherently lack the information to distinguish between biological false positives and true positives. The analysis presented here is developed for data from two-hybrid screens alone and only detects technical false positives. Previous studies suggest that biological false positives may be rare, as interactions reliably identified in high-throughput two-hybrid screens are of similar quality as interactions from small-scale experiments (Rual et al., 2005). The probability that a non-interacting protein is scored as positive is termed the false positive rate. An alternative statistic is the false discovery rate (FDR), the fraction of scored positives that are true negatives.

Similarly, false negatives may have technical or biological origins. Technical false negatives in the two-hybrid screens considered here are due to under-sampling: clones corresponding to the true interaction exist, but were missed due to a stochastic sampling process. Biological false negatives are systematically absent from screening data. These may be due to requirements for temperature, pH, cofactors, scaffold proteins or post-translational modifications.

Estimates of the false discovery and false negative rates (FNRs) in yeast and human interactomes can be based on intersections of independent datasets (Hart et al., 2006). However, because the assays have little overlap, the estimates have large variances. Overlap methods are restricted to global estimates of the rates, which provide limited information in understanding protein-specific problems. More recent work has used a multinomial model for node degree in the presence of false positives and false negatives, but is not directly applicable to pooled screens where clones are sampled to identify interacting pairs (Scholtens et al., 2008).

An important related problem is the degree distribution of interaction partners. Statistical models of degree distributions can be sensitive to a few observations of high-degree proteins in the tail of a distribution. In other contexts, spurious observations at the tail of a distribution have led to faulty conclusions of power-law (PL) behavior. For example, initial studies of animal foraging patterns characterized the distributions as PL Lévy walks (Viswanathan et al., 1996). The same authors recently revisited these datasets and concluded that the PL were erroneous, with the actual distributions having exponential truncation (Edwards et al., 2007).

A capture–recapture estimator was recently proposed by some of us (Huang et al., 2007). This framework differs from the classical capture–recapture method in that it models the captured species as a mixture of true positives and false positives, whereas the classical theory admits only true positives. In a two-hybrid screen, a bait protein is used as a query to sample its interaction partners. False positive interaction partners may arise as spurious interactions and true interaction partners may be missed due to insufficient sampling depth. The number of the missing true-interaction partners can be estimated using the k-sample capture–recapture method (Jolly, 1965; Seber, 1965) and the number of false positives can be estimated from the likelihood function based on a binomial distribution once the FDR is known. The estimates for the two quantities have to be done jointly because the known number of interactions from the two-hybrid screen is a mixture of both true interactions and false positives. Expectation maximization (EM) solves this joint estimation problem (Dempster et al., 1977).

In the true biological system, different baits probably have different FDRs. Thus, the previous capture–recapture model permitted baits to have different FDRs: in addition to a null model with a uniform FDR, a scaled error rate model reflected mass balance between true positives and false positives, and a two-component mixture error rate model assumed a mixture of ‘good’ baits and ‘bad’ baits. The two-component mixture was found to be the best fitting model for experimental data from yeast (Ito et al., 2001), worm (Li et al., 2004) and fly (Giot et al., 2003).

A natural and important question to ask is whether the heterogeneity in FDRs is limited to a two-component mixture, or whether more components would provide an improved description and improved estimates of bait-specific error rates. The biological significance is that protein properties associated with high error rates could be identified and used to improve screening protocols and also improve confidence values ascribed to screening results.

Here, we investigate this question. Although one approach would be to systematically add additional mixture components, this would lead to more parameters, risking over-fitting. We take an alternate approach by proceeding directly to what is essentially an infinite-component mixture model in which error rates in the range 0–1 are modeled by a two-parameter beta distribution. Depending on the choices of both the parameters, beta distributions can be unimodal, U-shaped, strictly increasing/decreasing or uniform. EM can be used to determine the beta distribution parameters jointly with posterior estimates of bait-specific FDRs.

This work first uses standard model selection criteria to demonstrate that the beta distribution error rate model improves inference within the capture–recapture framework. With the updated estimates of the FDRs and FNRs for each protein, we perform stringent tests to identify protein characteristics that correlate with elevated or reduced FDRs and protein degrees. Estimated error rates are compared with previous methods based on overlap of datasets, including a recently available screen of yeast (Yu et al., 2008).

2 METHODS

2.1 Data sources

Datasets were collected from two-hybrid screens for yeast (Ito et al., 2001), worm (Li et al., 2004) and fly (Giot et al., 2003). Many two-hybrid screens, including those for human (Rual et al., 2005; Stelzl et al., 2005), have not released clone-level information and thus cannot be analyzed by these methods.

2.2 Overview of the model and definitions

Consider a particular protein j used as one of the N baits in a two-hybrid screen against a pool of Γ possible preys. A total of nj clones have been sampled, out of which wj unique preys are found to interact with bait j. Among the wj interaction partners of bait j, sj have been sampled once and wj–sj have been sampled at least twice. Any interaction partner that appears twice is virtually assured to be a true positive; thus, we treat pairs that interact reproducibly in vitro as true positives. As noted in the Section 1, this treatment addresses only technical false positives, as opposed to biological false positives that are observed systematically in vitro but do not occur in vivo. Based on this assumption, we assume fj out of sj singletons are false positives and all the interactions that have been sampled more than once (there are wj–sj of them) are true positives. For a given FDR αj and interaction degree distribution parameters Φ, the joint distribution of the total number of true interactions (kj) and the number of false positives in the sampled interactions (fj) is

| (1) |

in which ℕ is a normalization constant:

| (2) |

Pr(kj|Φ) is the prior distribution of the protein interaction degree. Pr(fj|sj,nj,αj) and Pr(kj|wj,fj,nj) are the probabilities that bait j has fj false positives and kj true interaction partners.

For convenience, we define xj=observed variables (sj,wj,nj);yj=hidden variables (kj,fj); and Q=parameters for the degree distribution and error rate. Standard EM methods may be used to identify the parameters  that maximize the probability of the observed variables (see Supplementary Methods). Posterior means of the hidden variables are then

that maximize the probability of the observed variables (see Supplementary Methods). Posterior means of the hidden variables are then

|

(3) |

The logarithmic transform in the degree estimates improves stability for long-tailed distributions. FNRs are defined as  .

.

2.3 Beta distribution

FDRs can be modeled as samples from a beta distribution, a standard generative model for probabilities because its values are in the range 0–1. It is also a natural conjugate prior for a binomial distribution. The beta error rate model has two non-negative shape parameters, β1 and β2. The distribution of the FDR αj conditioned on the two parameters is

| (4) |

with normalization Beta(β1,β2)=Γ(β1)Γ(β2)/Γ(β1+β2).

When β1, β2, and the degree distribution parameters have been determined, posterior estimates are obtained from the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE),  .

.

Model selection used log-likelihood from 10-fold cross-validation, the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) of the likelihood of the full data, and BIC of 100 bootstrap replicates of the full data to assess stability. Full details of EM update equations and model selection criteria are available (see Supplementary Methods).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Model selection

Our previous report, with full details of model selection by cross-validation log-likelihood, BIC and bootstrap replicates, demonstrated that the two-component error model was superior to both the single and scaled error rate models, and that the truncated PL (TPL) generally dominated the purely scale-free PL distribution (Huang et al., 2007). These model selection criteria have demonstrated that the beta error model is markedly superior to the two-component mixture for all three organisms tested (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). The beta error rate model, in combination with the TPL degree distribution, has the best log likelihood and the best BIC score for all three organisms. Of the 100 bootstrap replicates, 96 choose beta and TPL as the best prior combination for yeast and all choose this model for both worm and fly. The remaining four replicates for yeast chose the beta error model with the PL distribution. The fitted parameters for this model are presented (Table 1). These results again confirm the conclusion that protein interaction degree distributions are not scale-free, but instead are subject to exponential or similar truncation.

Table 1.

Network properties and parameter estimations for the beta error rate model with TPL degree distributions

| Properties | Yeast | Worm | Fly |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network | |||

| N | 1532 | 729 | 3639 |

|

7.65 | 20.08 | 14.79 |

|

2.97 | 5.55 | 5.69 |

|

1.97 | 3.71 | 3.57 |

| Parameter | |||

| ɛ | 1.61729 | 0.84128 | 0.62162 |

| c | 0.00354 | 0.06187 | 0.11412 |

| β1 | 0.76185 | 1.39727 | 0.76634 |

| β2 | 9.21670 | 8.43195 | 4.26594 |

|

0.09930 | 0.13187 | 0.16999 |

| Estimates | |||

|

4.49 | 5.02 | 4.43 |

|

0.76 | 2.65 | 2.51 |

| FNR (%) | 51 | 42 | 28 |

| FDR per unique interaction (%) | 26 | 48 | 44 |

| FDR per singleton (%) | 39 | 71 | 70 |

| Bootstrap wins | 96/100 | 100/100 | 100/100 |

N is the number of baits.  is the average number of preys sampled per bait,

is the average number of preys sampled per bait,  is the average number of unique preys and

is the average number of unique preys and  is the average number of singletons.

is the average number of singletons.  is the estimated number of preys per bait and

is the estimated number of preys per bait and  is the estimated number of false positives per bait. The FDR per clone (

is the estimated number of false positives per bait. The FDR per clone ( ) is

) is  , the FDR per unique interaction is

, the FDR per unique interaction is  and the FDR per singleton is

and the FDR per singleton is  .

.

3.2 False discovery rate

The overall FDRs estimated using the beta error rate model increase to 9.9% (yeast), 13.2% (worm) and 17.0% (fly) from 9.3%, 12.2% and 15.7% estimated using the two-component mixture error model. This small increase may indicate an improved estimate of the high FDR component in the two-component mixture model.

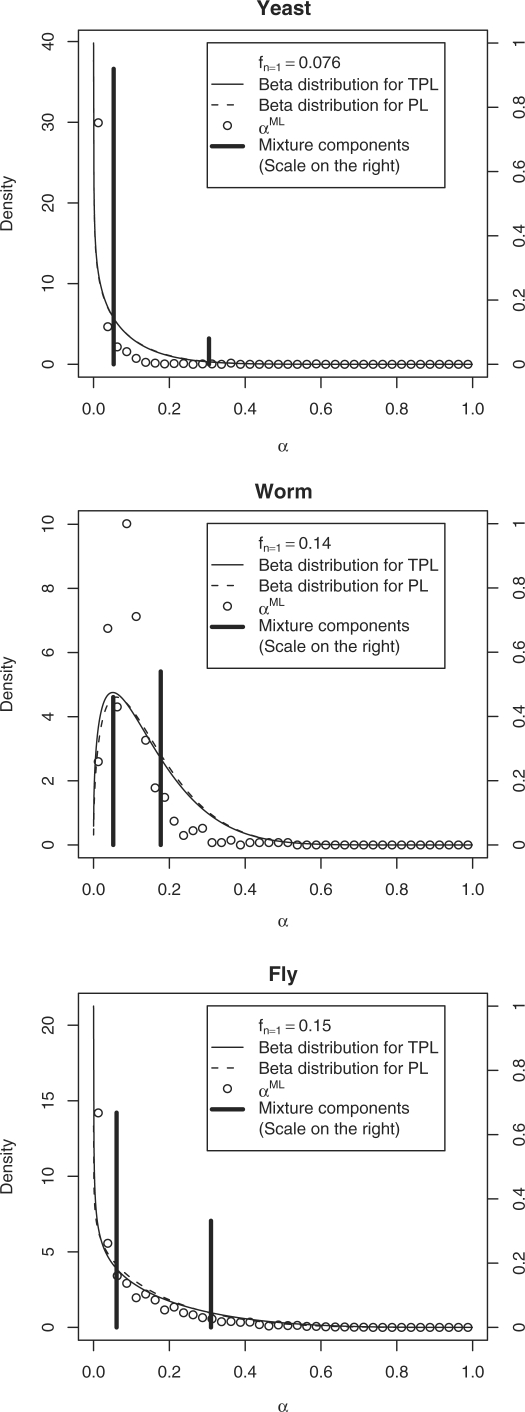

The FDRs for individual baits are indeed quite disperse, demonstrating why the beta distribution improves on a two-component mixture model (Fig. 1). These results are significant because they provide the first picture of the shape of the FDR distribution, as opposed to a lumped mean.

Fig. 1.

The distributions of FDRs for baits are displayed for Beta/TPL (solid line), Beta/PL (dashed line) and Mixture/TPL (black impulses) for yeast (A), worm (B) and fly (C). Posterior maximum likelihood estimates are displayed for the Beta/TPL model (open circles). Baits with a single clone do not contribute to the estimator and are not included in the histograms.

The beta distribution is strictly decreasing for the yeast and fly but peaked for the worm, consistent with MLE estimates. The distribution of FDRs for worm, worm open reading frame (ORF) and cDNA collections are also peaked (Supplementary Fig. S1), suggesting that this is an intrinsic property of the worm screens. One possibility is that this screen was more stringent in eliminating auto-activators. In agreement with previous analysis (Huang et al., 2007), the ORF collection has a lower FDR than the cDNA collection in worm.

These results indicate that a vast majority of baits perform well in the assays, with a small number of baits contributing a proportionally larger number of spurious interactions. Because the error-rates are bait specific, we can proceed to attempt to identify systematic characteristics leading to spurious interactions.

3.2.1 Gene annotation

The Gene Ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al., 2000) provides a controlled vocabulary to describe gene attributes in any organism. Attributes such as membrane localization have been suggested to influence performance of a protein in a two-hybrid screen. Access to posterior estimates of the FDR permits a robust non-parametric test (Wilcoxon-signed rank test) to identify classes of proteins with elevated or reduced FDRs. Two-sided P-values were corrected for multiple testing by multiplying by the number of GO terms tested (Bonferroni method).

GO terms having significantly higher or lower FDRs were identified (Supplementary Table S2). The non-parametric test yields fewer significant findings than a previous parametric test based on estimates of the number of false positives, rather than on the FDR directly (Huang et al., 2007). There are two main differences in methods: use of a beta versus mixture model for FDRs, and use of a non-parametric Wilcoxon test versus a parametric binomial test for significance. We find that the smaller number of significant findings is due to the use of the non-parametric test, rather than a difference in FDR estimates (Supplementary Fig. S4). The categories that trigger only the parametric test are enriched for singleton interactions, which may violate the assumptions of the parametric test due to correlations between baits (each is assigned the bulk parameter value). The newer non-parametric test may be more robust to this effect.

Despite these differences, major conclusions are still valid. Grouped by biological processes, the cellular metabolic process (worm) and the regulation of metabolic process (yeast) show elevated FDRs. Molecular functions involved in protein binding and transcription regulator activity, particularly RNA polymerase II transcription factor activity (yeast), also have elevated FDRs.

Proteins involved in fly multicellular organismal process and development are newly identified to have a high FDR. Sequence-specific DNA binding is also found to have an elevated FDR. These proteins include transcription factors, whose auto-activation within the two-hybrid system may trigger false positive findings. Thus, a possible explanation of these results is that auto-activators were not sufficiently characterized and removed from the bait collection.

Although nuclear membrane proteins (yeast) show a high FDR, proteins that are intrinsic to membranes, particularly those integral to membranes (fly), show a low FDR. A closer examination indicates that nuclear pore proteins, pore complex members (cellular component) and proteins involved in the nuclear import (biological process) have high FDRs. On the other hand, integral membrane proteins do not have higher FDRs as a group. These results suggest that large pore complexes may be generally ‘sticky’, perhaps to provide general affinity for many types of proteins.

3.2.2 Promiscuous and chaste domains

A protein domain is a fragment of amino sequence that may appear in multiple proteins and function independently of the rest of amino acid chains. We tested the hypothesis that some protein domains may yield more false positive interactions than others. The PFAM database (Bateman et al., 2004) was used to characterize protein domains. We define the FDR of each domain as a collection of the FDRs of the proteins having this domain. We used a similar approach as we analyzed the GO terms to test whether some domains consistently yield more (or fewer) false positive interactions than others.

The only significant PFAM domain was the Homeobox domain (PF00046), which occurs in 29 fly bait proteins. The mean FDRs are 16% and 7.9% for proteins with and without this domain, respectively. Homeobox domains are transcriptional regulators that operate differential genetic programs along the animal anterior–posterior axis. This result is consistent with the GO term result that proteins which are transcription regulators or those involved in multicellular organismal development are more likely to yield false positives.

3.2.3 Hydrophobic interactions and protein length

The GO term analysis suggested proteins that are integral to membranes have a low FDR. We assessed this hypothesis by testing for the significant correlations between the FDRs and the hydrophobicity of proteins. Hydrophobicity scales were denoted Kyte–Doolittle (Kyte and Doolittle, 1982), Eisenberg (Eisenberg et al., 1984), Cornette (Cornette et al., 1987) and Rose (Rose et al., 1985). For each protein, we summed the hydrophobic values of each amino acid residue to obtain a summary value for the entire protein chain. We then tested the significance of a linear model that the FDRs depend on the hydrophobicity values (Supplementary Table S4). We also reported the significance level of a reference model testing the linear correlation between the rank orders of both variables.

We observed negative correlations between the FDRs and hydrophobicity values, indicating that proteins having high hydrophobicity scores are less likely to generate false positive interactions. This result agrees with our finding in the GO analysis that membrane intrinsic and integral proteins tend to have smaller FDRs. Although the correlations are very weak from the magnitude of the slope and the R2-values, they are significant across all the hydrophobicity scales and all the three species. One explanation for the weak correlation is that the entire length of the protein is used for the hydrophobicity score, which dilutes the magnitude of correlation by the variance of the sequence as a whole. As discussed in the GO term analysis, membrane proteins with chains exposed in cytoplasm or nucleus, such as nuclear pore proteins, have high FDRs.

We did not find significant correlations between the FDRs and the protein lengths for yeast and worm. However, we do see a significant correlation for fly. The test using rank orders shows significant correlations for all three organisms.

3.3 False negative rates

Statistical tests indicate that the TPL distribution is superior to other tested degree distributions for yeast, worm and fly. Although TPL was the best-fit model for worm and fly in Huang et al., (2007), its estimated parameters changed in this work because of the updated FDRs. Therefore, the projected average number of interaction partners per bait has dropped to 4.5, 5.0 and 4.4 from 4.8, 5.9 and 5.0 for yeast, worm and fly, respectively. The FNRs are 51%, 42% and 28% for yeast, worm and fly, respectively. In addition to the global analysis of the protein degrees, we also investigated protein characteristics that correlate with more or fewer interaction partners.

3.3.1 Gene annotations and protein domains

Proteins involved in organ development and multicellular organismal processes have roughly 20% more interaction partners than proteins not involved in the processes (Supplementary Table S3), a statistically significant difference (P-values=0.048 and 0.049 after multiple-testing correction). In terms of molecular function, proteins that selectively bind identical proteins, such as homodimers, have on average 1.33 fewer interaction partners (corrected P-value=0.0005). The protein binding category, the parent category of the identical protein binding, is surprisingly found to have fewer interaction partners than average. Around 82% of fly proteins are associated with this category and they have 0.32 fewer interaction partners than proteins not associated with this category (corrected P-value=0.046).

We did not find any PFAM protein domains that are significantly associated with greater or fewer interaction partners.

3.3.2 Hydrophobic interactions and protein length

We found significant but weak correlations between the hydrophobicity scales and the interaction degrees in worm and fly (Supplementary Table S4). All four hydrophobicity scales indicate that hydrophobic proteins tend to have fewer interaction partners. One possibility is that the hydrophobic proteins are mis-folded in the two-hybrid screens and lose their binding functions. In addition, hydrophobic proteins may have fewer available binding domains because a significant proportion of the protein sequence is membrane-bound.

The correlation between the hydrophobicity scales and the protein degrees is not significant for yeast. This may be due to fewer hydrophobic proteins in yeast compared with worm and fly, which reduces the significance even if the effect size is identical. Yeast has 50% and 83% fewer transmembrane proteins compared with fly and worm (Krogh et al., 2001).

Protein length is not significantly correlated with protein interaction degree for yeast and worm based on linear correlation, but a more robust rank-order test does show weak but significant positive correlation. The linear correlation for fly is significant but weak, with R2-value of 0.006.

3.4 Correlations among counts and error rates

We tested for correlations among  , n, αML and

, n, αML and  . We used

. We used  instead of w because

instead of w because  has been corrected for the false positives. The estimated true number of interactions (

has been corrected for the false positives. The estimated true number of interactions ( is strongly correlated with the observed number (

is strongly correlated with the observed number ( (Supplementary Fig. S2). The R2-values are 0.592, 0.474 and 0.628 for yeast, worm and fly, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). The true number of interactions also correlates very weakly with the number of clones (n). This correlation may be caused by the dependence of the number of observed interactions on the number of clones.

(Supplementary Fig. S2). The R2-values are 0.592, 0.474 and 0.628 for yeast, worm and fly, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). The true number of interactions also correlates very weakly with the number of clones (n). This correlation may be caused by the dependence of the number of observed interactions on the number of clones.

The estimated αML depends on both the observed ( and the true number of interactions (

and the true number of interactions ( . The dependence of the FDR on the number of clones (n) is significant in this work, although this correlation is much weaker than other correlations.

. The dependence of the FDR on the number of clones (n) is significant in this work, although this correlation is much weaker than other correlations.

3.5 Comparison with published estimates

Previous estimates of error rates have compared Y2H datasets to gold standards from annotations (Sprinzak et al., 2003), experimental structures (Edwards et al., 2002) and independent datasets (Hart et al., 2006). The estimates for the FDR range from 50% to 90% and the estimates for the FNR range from 43% to 90% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison with previous studies using computational predictions, overlap with gold standards and capture–recapture theory

| Method | FNR (%) | FDR (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast | |||

| Prediction | – | 72–84 | (Deane et al., 2002) |

| Overlap | >70 | >50 | (von Mering et al., 2002) |

| Overlap | 43–71 | – | (Edwards et al., 2002)a |

| Overlap | 76–96 | – | (Edwards et al., 2002)b |

| Overlap | – | 50 | (Sprinzak et al., 2003) |

| Overlap | 80–85 | – | (Salwinski et al., 2004) |

| Overlap | 50 | 70–90 | (Hart et al., 2006) |

| Recap | 52 | 24 | (Huang et al., 2007) |

| Overlap | 62 | 52 | This workc |

| Recap | 51 | 26 | This work |

| Worm | |||

| Prediction | 22–100 | – | (Salwinski et al., 2004) |

| Recap | 47 | 44 | (Huang et al., 2007) |

| Recap | 42 | 48 | This work |

| Fly | |||

| Prediction | 74–96 | – | (Salwinski et al., 2004) |

| Recap | 32 | 41 | (Huang et al., 2007) |

| Recap | 28 | 44 | This work |

aEstimated using crystal structure data.

bEstimated using MIPS complexes data.

cOverlap from comparison with data from Yu et al. (2008).

Bold values indicate results from this work.

A recent high-quality two-hybrid screen is now available for the yeast proteome (Yu et al., 2008). We report overlap-based error rates using this new data as a gold standard (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S6). The overall FDR and FNRs estimated from the comparison are 52% and 62%, respectively, compared with 26% and 51% from capture–recapture.

Comparing the capture–recapture estimates with estimates from overlap identifies four GO Slim categories for baits with significantly lower capture–recapture FDRs: cytoplasm and membrane fraction from the cellular component ontology, and membrane organization/biogenesis and transport from the biological process hierarchy (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Table S7). A similar analysis identifies categories with baits having lower FNRs according to capture–recapture (Supplementary Table S7).

The discrepancy in estimated error rates is due in part to systematic differences between the interactions observed in the two screens. There are 78 interactions in Ito et al., (2001) with three or more clones that do not appear in Yu et al., (2008), even though these interactions were tested. These interactions are scored as true positives based on capture–recapture, but as false positives based on overlap. An analysis of the annotations of these proteins immediately identifies 12 of these 78 interactions as highly likely true positives (Supplementary Table S8), and thus false negatives in the more recent dataset. These results indicate that estimates of false positive and FNRs from overlap may be biased by systematic differences between screens.

4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Protein interaction screens do not work uniformly well for each protein. This work develops a statistical model for heterogeneous FDRs for proteins used in two-hybrid screens. The model uses the beta distribution as a prior distribution for FDRs. Statistical model selection criteria decisively choose this model over a simpler dichotomous categorization into good and bad proteins.

The bait-specific FDRs can then be used to identify classes of proteins that perform better or worse on average in two-hybrid screens. One consistent finding is that normalized libraries of cloned ORFs perform better than cDNA libraries. This may be due to better normalization of individual preys, better DNA quality or both. For application to cDNA libraries, accounting for heterogeneous mRNA abundance may improve error rate estimates. We do not pursue this direction because cloned ORFs have been used exclusively in the most recent screens.

Posterior estimates of FDRs permit tests of hypotheses that hydrophobic or promiscuous domains lead to non-specific interactions. Similarly, estimates of true interaction counts permit tests of hypotheses that classes of proteins are hubs. Evidence for these hypotheses is limited. Proteins involved in transcription regulations and cellular metabolic processes have a high FDR, in accord with previous work. Fly proteins that are involved in multicellular organismal process and development, and sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins are also found to be error-prone, possibly due to auto-activation rather than non-specific interactions. While proteins that function in membrane pores have high FDRs, intrinsic membrane proteins have reduced FDRs. Although previous work found a larger number of protein categories to have elevated FDRs (Huang et al., 2007, p. 497), the current work is based on non-parametric tests that are likely to be more robust.

Several model selection criteria indicate that protein interaction degree distributions are not scale free; exponential truncation provides a superior fit. Analysis of protein interaction degrees indicates that proteins involved in fly developmental processes and multicellular organismal processes are likely to have more interaction partners, while proteins involved in binding identical proteins, such as homodimers, are likely to have fewer interaction partners. Hydrophobic proteins also generally have fewer interaction partners.

The statistical methods described here will be relevant for future two-hybrid screens. Ultra-high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies, such as 454 (Margulies et al., 2005), Illumina (Hillier et al., 2008) and ABI SOLiD (Valouev et al., 2008) have the potential to sample far deeper into bait–prey clones. Bayesian methods for error rate estimation can also be used to improve data integration from multiple independent screens, as has been reported for studies of co-complex membership (Gilchrist et al., 2004).

Improved pooling strategies may also increase the efficiency of two-hybrid screens (Thierry-Mieg and Bailly, 2008), with a move to smaller pools and redundancy for error checking. To take advantage of smaller pool sizes (including direct tests of each pair) and increased bi-directional coverage, the probability that a specific interaction is true would become a latent variable conditioning both the bait–prey and prey–bait observations, as opposed to the uni-directional methods described here. These additional variables would add to the computational complexity, but not necessarily to the number of free parameters in a model. Extensions of this capture–recapture theory are therefore feasible and relevant to future studies of protein–protein interactions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge helpful discussions with Bruno Jedynak and with Christopher Wiggins at an IPAM workshop.

Funding: National Science Foundation (grant no. NSF CAREER 0546446); National Institutes of Health U54RR020839.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader JS, Chant J. Systems biology. When proteomes collide. Science. 2006;311:187–188. doi: 10.1126/science.1123221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornette JL, et al. Hydrophobicity scales and computational techniques for detecting amphipathic structures in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;195:659–685. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane CM, et al. Protein interactions: two methods for assessment of the reliability of high throughput observations. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:349–356. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m100037-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, et al. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AM, et al. Bridging structural biology and genomics: assessing protein interaction data with known complexes. Trends Genet. 2002;18:529–536. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02763-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AM, et al. Revisiting Levy flight search patterns of wandering albatrosses, bumblebees and deer. Nature. 2007;449:1044–1048. doi: 10.1038/nature06199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, et al. Analysis of membrane and surface protein sequences with the hydrophobic moment plot. J. Mol. Biol. 1984;179:125–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist MA, et al. A statistical framework for combining and interpreting proteomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:689–700. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giot L, et al. A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2003;302:1727–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.1090289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GT, et al. How complete are current yeast and human protein-interaction networks? Genome Biol. 2006;7:120. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-11-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier LW, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and variant discovery in C. elegans. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, et al. Where have all the interactions gone? Estimating the coverage of two-hybrid protein interaction maps. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, et al. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:4569–4574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson N, Varshavsky A. Split ubiquitin as a sensor of protein interactions in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:10340–10344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly GM. Explicit estimates from capture-recapture data with both death and immigration-stochastic model. Biometrika. 1965;52:225–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, et al. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, et al. A map of the interactome network of the metazoan C. elegans. Science. 2004;303:540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1091403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M, et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose GD, et al. Hydrophobicity of amino acid residues in globular proteins. Science. 1985;229:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.4023714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rual JF, et al. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein–protein interaction network. Nature. 2005;437:1173–1178. doi: 10.1038/nature04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salwinski L, et al. The Database of Interacting Proteins: 2004 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D449–D451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtens D, et al. Estimating node degree in bait-prey graphs. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:218–224. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seber GA. A note on the multiple-recapture census. Biometrika. 1965;52:249–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinzak E, et al. How reliable are experimental protein–protein interaction data? J. Mol. Biol. 2003;327:919–923. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagljar I, et al. A genetic system based on split-ubiquitin for the analysis of interactions between membrane proteins in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5187–5192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzl U, et al. A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome. Cell. 2005;122:957–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarassov K, et al. An in vivo map of the yeast protein interactome. Science. 2008;320:1465–1470. doi: 10.1126/science.1153878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierry-Mieg N, Bailly G. Interpool: interpreting smart-pooling results. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:696–703. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz P, et al. Herpesviral protein networks and their interaction with the human proteome. Science. 2006;311:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1116804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz P, et al. A comprehensive analysis of protein–protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2000;403:623–627. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valouev A, et al. A high-resolution, nucleosome position map of C. elegans reveals a lack of universal sequence-dictated positioning. Genome Res. 2008;18:1051–1063. doi: 10.1101/gr.076463.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan GM, et al. Levy flight search patterns of wandering albatrosses. Nature. 1996;381:413–415. doi: 10.1038/nature06199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mering C, et al. Comparative assessment of large-scale data sets of protein–protein interactions. Nature. 2002;417:399–403. doi: 10.1038/nature750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, et al. High-quality binary protein interaction map of the yeast interactome network. Science. 2008;322:104–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1158684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.