Abstract

Tuberculosis is among the world’s deadliest infectious diseases. APS reductase catalyzes the first committed step in bacterial sulfate reduction and is a validated drug target against latent tuberculosis infection. We performed a virtual screening to identify APSR inhibitors. These inhibitors represent the first non-phosphate-based molecules to inhibit APSR. Common chemical features lay the foundation for the development of agents which could shorten the duration of chemotherapy by targeting the latent stage of TB infection.

Despite advances in chemotherapy and the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, tuberculosis (TB) remains a leading infectious killer worldwide.1 Although drugs exist to treat TB, they are not effective against bacilli that persist in a dormant or latent state within host lesions.2 As a result, current treatments for TB require a cocktail of three to five drugs for at least six months, a regime that many patients are unable or unwilling to follow.3 The lengthy and complex therapy also contributes to the development of drug-resistant TB, which is even more difficult and expensive to treat. Of the 9 million known cases of TB worldwide, as many as 2 percent could be extensively drug-resistant.4 This statistic raises the specter of virtually untreatable strains of TB and represents a severe public health problem. For these reasons, there is an urgent need for drugs that target the latent phase of TB infection.

To this end, microbial sulfate metabolism represents a promising new area for TB therapy.5 Reduction of inorganic sulfate is the means by which bacteria produce sulfide, the oxidation state of sulfur required for the synthesis of essential biomolecules including amino acids, proteins, and metabolites.5,6 APS reductase (APSR, encoded by cysH) catalyzes the first committed step in bacterial sulfate reduction.7 In this reaction adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (APS) is reduced to sulfite and adenosine-5′-phosphate (AMP).7 Consistent with its important metabolic role APSR was identified in a screen for essential genes in M. bovis BCG and cysH is actively expressed during the dormant phase of M. tuberculosis and in the environment of the host macrophage.5 Most recently, Senaratne et al. demonstrated that APSR is required for survival in the latent phase of TB infection.8 APSR is not found in humans and thus, represents a unique target for antibacterial therapy. Recognizing its value as novel antibiotic target, in 2006 Chartron et al. reported the three-dimensional (3D) crystal structure of Pseudomonas aeruginosa APSR in complex with APS substrate.9 P. aeruginosa and M. tuberculosis APSR are related by high sequence homology (27,2% of sequence identity and 41,4% of sequence similarity), particularly in residues that line the active site (Supporting Information). In this structure, APS is situated in a deep active site cavity with the phosphosulfate extending toward the protein surface.

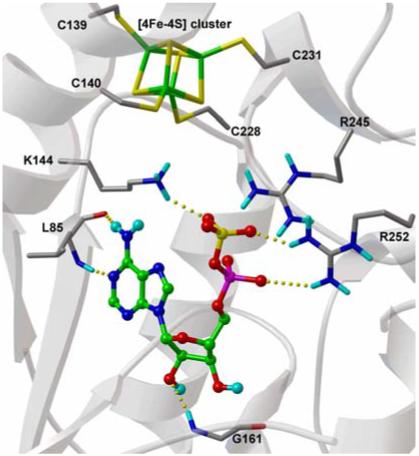

Conserved and semi-conserved residues participate in four main-chain hydrogen bonds with adenine and the ribose O2′ hydroxyl (Figure 1). Interaction between the phosphosulfate and APSR occurs via strictly conserved residues K144, R242 and R245 (Figure 1). The phosphosulfate is also positioned opposite an [4Fe-4S] cofactor and C140. However, the substrate is not in direct contact with the [4Fe-4S] cluster; the sulfate oxygens are 7Å from the closest iron atom and 6Å from the closest cysteine sulfur atom.

Figure 1.

Experimental binding conformations of APS in APSR structure. Substrate is displayed with carbon atoms in green, and key binding site residues are labelled. Hydrogen bonds are represented with dashed yellow lines.

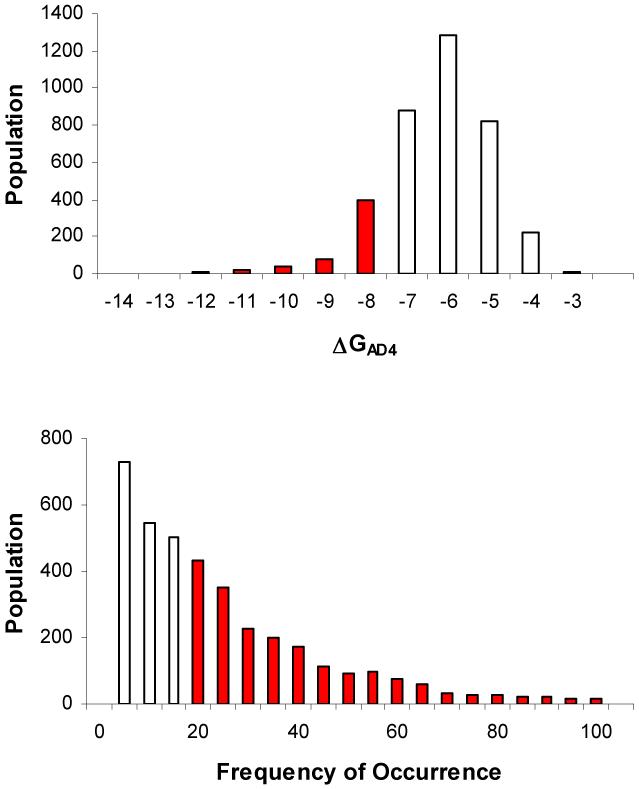

To date, only nucleotide-based inhibitors have been reported for APSR, and these are expected to have limited bioavailability.10 Solution of the P. aeruginosa APSR structure in complex with substrate affords a new opportunity for the discovery of inhibitors, particularly in the application of high-throughput docking of molecular databases to identify lead compounds. To this end, we have taken an approach that combines computational docking methods with biochemical evaluation. The new version of AutoDock (AD4)11 was used to conduct virtual ligand screening (VLS) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Diversity Set12 against the P. aeruginosa APSR crystal structure (PDB code 2GOY).Initial docking calculations were performed using APS substrate to evaluate APSR as a structural model for VLS. The docked conformation determined by AD4 with the lowest predicted binding energy (-9.46 kcal/mol; ΔGAD4) was in excellent agreement with the bound conformation observed for APS in the crystal structure (RMSD 0.7 Å); the calculated positions of the adenine ring, ribose sugar and phosphosulfate group were almost identical to those found in the crystal structure. Based on these encouraging results, VLS calculations were performed with the APSR crystal structure using the database of compounds in the NCI Diversity Set. The VLS results were sorted on the basis of their predicted binding free energies (ΔGAD4), which ranged from -3.16 to -13.76 kcal/mol, and according to the cluster size for each docking conformation. Solutions with a predicted binding free energy greater than -8.0 kcal/mol and a cluster size lower than 20 out of 100 individuals were discarded.

Cluster size is included in these criteria as an empirical measure of the configurational entropy, as shown in previous work.10 Based on these criteria, 14.8% of the solutions had energies lower than -8.0 kcal/mol, 43.3% had a cluster population higher than 20 individuals and 10.0% (192 compounds) met both these criteria (Figure 2). The predicted binding conformations for these 192 solutions were visually inspected. Compounds that were not predicted to interact with important residues such as K234, R242 or R245 were removed from consideration. After this final step, 42 compounds corresponding to 2% of the original NCI Diversity Set were selected for further analysis. When ordered from NCI (The NCI/DTP Open Chemical Repository), three of these compounds were not available, so 39 compounds were obtained for biochemical testing. Assessment of the 39 top-ranked compounds from the VLS as potential inhibitors of APSR was performed using a standard radioactive assay, measuring APSR reduction of 35S-labeled APS substrate. The compounds that exhibited significant inhibitory activity (more than 50% inhibition) are listed in Table 1, along with the AD4 binding energies and measured activities. Three compounds from this set, tested at 100 μM, inhibited APSR activity by more than 50%: 133896, 327704, and 348401 (Table 1). In particular, 348401 resulted in more than 90% inhibition (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Results of the VS (using AD4) of the NCI Diversity Set against APSR. a) Bars represent numbers of Diversity Set compounds with predicted free energies of binding in the indicated 1 kcal/mol bins. Red bars highlight the energies of those compounds having a ΔGAD4 lower than -8 kcal/mol. b) Bars represent the population of the frequency of occurrence of the largest cluster for each docked ligand. Red bars highlight a frequency of occurrence higher than 20 out of 100.

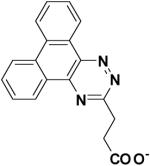

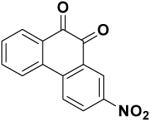

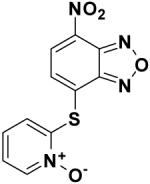

Table 1.

Structures, AutoDock Binding Energies and Activities of APSR First Generation Inhibitor Compounds

| Chemical Structure | NSC Number | ΔGAD4 (kcal/mol) | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

16211 | -8.72 | 180.35 |

|

133896 | -8.75 | 37.11 |

|

327704 | -8.21 | 46.85 |

|

348401 | -9.63 | 15.19 |

|

9746 | -9.34 | 127.19 |

Compounds listed in Table 1 were predicted to have the similar affinities for APSR (see Table 1, ΔGAD4), however the experimental binding constants span a range of 6.81 to 48.11 uM. This is not unexpected, since the computed binding energies in calibration experiments typically have errors in the range of 2 kcal/mol, which corresponds roughly to a 30-fold difference in predicted binding constants. The above mentioned compounds, representing the most potent inhibitors from our screen, were investigated further and were found to produce concentration-dependent inhibition of APSR activity without promiscuous inhibition. Data were fit to a competitive inhibition model (R2 ≥ 0.98) and the inhibition constant (Ki) was determined for each compound in Table 1. Under the conditions employed for these assays the Ki was equal to the dissociation constant (Kd) of each compound (Supporting Information). Dissociation constants for the most potent inhibitors in Table 1 ranged from 15-50 μM.

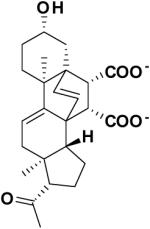

Second-generation lead compounds were identified by docking and assaying compounds from similarity searches, based on chemical structures and substructures of the Diversity Set leads. This search was performed using the Enhanced NCI Database Browser, a Web-based graphical user interface with a large number of possible query types and output formats. 890 out of 250,000 compounds were identified in the Open NCI database with at least 80% Tanimoto similarity and docked. The 40 highest-scoring solutions, ranked according to the criteria outlined above, were experimentally evaluated using our biochemical assay. Five compounds were identified with dissociation constants less than 50 μM, with 4 similar to primary lead 133896 (60826, 55545, 57476, and 23180) and one similar to primary lead 348401 (228155).

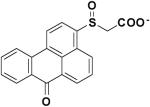

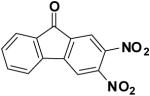

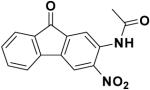

The similarity search based on the parent compound 133896 identified three new leads (60826, 55545, and 57476) with a 9-fluorenone core structure and activity against APSR and the 9-fluorenone core structure (Table 2). The dihydrophenanthrendione 23180 was the most potent inhibitor identified in this study, with a dissociation constant of less than 10 μM. Visual inspection of the predicted binding pose for 23180 (Figure 3a) reveals that the aromatic polycyclic scaffold inserts into a profound gorge (referred to as L1) and makes favorable hydrophobic contacts with the side chains of residues L90 and I98. Additional interactions include the nitro functional group in proximity to positively charged active site residues K144 and R245 (referred to as P1) as well as hydrogen bonding from the carbonyl oxygens in the aromatic moiety to the backbone amide of L85 and side-chain of S62.

Table 2.

Structures, AutoDock Binding Energies and Activities of APSR Second Generation Inhibitor Compounds

| Chemical Structure | NSC Number | ΔGAD4 (Kcal/mol) | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

60826 | -8.46 | 31.79 |

|

55545 | -8.23 | 48.11 |

|

57476 | -8.60 | 44.59 |

|

23180 | -8.94 | 6.81 |

|

228155 | -8.7 | 19.51 |

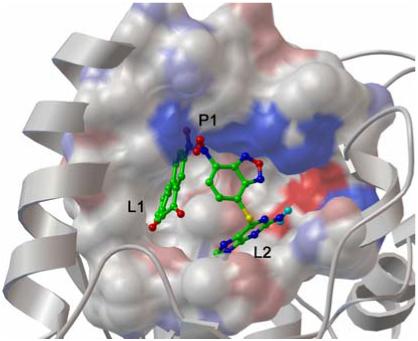

Figure 3.

Docked conformations of NSC23180 (a) and NSC348401 (b) in APSR structure. Ligands are displayed as in Figure 1. Hydrogen bonds are represented with dashed yellow lines.

Similar binding poses and interactions are predicted for compounds 133896, 60826, 55545, and 57476. However, these molecules have one less carbonyl oxygen in the aromatic moiety relative to the dihydrophenanthrendione chemical scaffold.

As a result, the 9-fluorenone-derived compounds are not predicted to form a hydrogen bond with S62 and could account for the difference in potency between the two structural cores. We also note that neither 9-fluorenone nor 2-nitro-9-fluorenone, which are closely related to 133896, exhibited significant activity against APSR. Rather, our data indicate that a H-bond acceptor group is required at position 3 or 4 of the 9-fluoronone scaffold to acquire inhibitor potency (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Previous studies show that compound 23180 can inactivate the tyrosine phosphatase CD45 via a catalytic and oxygen-dependent reaction (Kinactivation 4300 M-1s-1).13 Although the precise mechanism remains unknown, inactivation of CD45 by 23180 is correlated with oxidation of a catalytic cysteine residue to sulfinic and sulfonic acid. To test whether 23180 inhibited APSR in a similar fashion control experiments were performed. Unlike CD45, preincubation of APSR with 23180 did not result in enzyme inactivation and C256 was not covalently modified (Supporting Information).

Compound 327704 is structurally unrelated to other inhibitor cores identified by these studies. Nonetheless, this compound is also predicted to interact with the L1 pocket via its polycyclic aromatic ring and the P1 region through the polar carboxylate group.

Compounds 348401 and 228155 contain a benzoxadiazole moiety. This functional group adopts the same binding pose in both compounds and is oriented in a way that maximizes electrostatic interactions with R242 and K144 (Figure 3b). Each benzoxadiazole is distinguished by a pendant thioaryl group, which is embedded in a hydrophilic cleft (referred as L2) and forms two hydrogen bonds to the side chains of D66 and E65. The low micromolar activity of 348401 and 228155, combined with the ability to chemically derivatize the purine scaffold, suggests that this compound class may be a promising lead.

Interestingly, though compounds 23180 and 348401 both contain a polycyclic aromatic ring they are not predicted to adopt the same binding position and interact with similar residues (Figure 4). Rather, 23180 is positioned deep inside the L1 cavity, flanked by the [4Fe-4S] cluster while 34801 occupies the shallower and more polar L2 region of the active site, which is consistent with the more polar nature of the ring in this compound. Nevertheless, both classes of inhibitors are predicted to interact with the conserved positively charged residues that border both clefts in the P1 site. These observations suggest that a ligand, which can occupy both L1/L2 clefts and bears polar hydrogen bond accepting groups to interact with the P1 site, may exhibit higher activity against APSR. We are currently testing this model and the results of these studies will be reported in due course.

Figure 4.

Binding pose of both NSC23180 and NSC348401 in the APSR binding site. Ligands and residues belonging to the P1 site and are depicted in capped sticks colored by atom types. Residues belonging to the L1 and L2 sites are depicted as MSMS surface colored by atom type with charged atoms in bright colors and uncharged atom in pale colors, the protein secondary structure (white ribbon) is also depicted.

In conclusion, we have applied virtual ligand screening of compounds from the NCI database to identify low micromolar inhibitors of M. tuberculosis APSR, a validated target against latent TB infection. The molecules described here are the first non-phosphate-based inhibitors of this enzyme and may form the basis for development of an APSR inhibitor pharmacophore. Further studies on the inhibitors identified here should also shed light into the mechanism, targeting, and therapeutic potential of this enzyme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Garrett M. Morris, Ruth Huey, and Louis Noodleman for valuable discussions. This work was funded in part by grants R01GM069832 and P41 RR08605 from The National Institutes of Health. This is manuscript #19523 from the Scripps Research Institute

Abbreviations

- APS

Adenosine 5′-Phosphosulfate

- APSR

Adenosine 5′-Phosphosulfate Reductase

- AD4

AutoDock4

- VLS

virtual ligand screening

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

References

- (1).(a) Corbett EL, Watt CJ, Walker N, Maher D, Williams BG, Raviglione MC, Dye C. The growing burden of tuberculosis: global trends and interactions with the HIV epidemic. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003;163:1009–1021. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.9.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione MC, WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. JAMA. 1999;282:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kochi A. The global tuberculosis situation and the new control strategy of the World Health Organization. 1991. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001;79:71–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Flynn JL, Chan J. Tuberculosis: latency and reactivation. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:4195. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4195-4201.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang Y. Persistent and dormant tubercle bacilli and latent tuberculosis. Front. Biosci. 2004;9:1136–1156. doi: 10.2741/1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Espinal MA. The global situation of MDR-TB. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2003;83:44–51. doi: 10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).World Health Organization 2003 http://www.who.int/gtb/

- (5).Bhave DP, Muse WB, III, Carroll KS. Drug targets in mycobacterial sulfur metabolism. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:140–158. doi: 10.2174/187152607781001772.and references within.

- (6).(a) Mougous JD, Green RE, Williams SJ, Brenner SE, Bertozzi CR. Sulfotransferases and sulfatases in mycobacteria. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:767–776. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schelle MW, Bertozzi CR. Sulfate metabolism in mycobacteria. Chembiochem. 2006;7:1516–1524. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Williams SJ, Senaratne RH, Mougous JD, Riley LW, Bertozzi CR. 5′-adenosinephosphosulfate lies at a metabolic branch point in mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32606–32615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Carroll KS, Gao H, Chen H, Leary JA, Bertozzi CR. Investigation of the iron-sulfur cluster in Mycobacterium tuberculosis APS reductase: implications for substrate binding and catalysis. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14647–14657. doi: 10.1021/bi051344a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Senaratne RH, De Silva AD, Williams SJ, Mougous JD, Reader JR, Zhang T, Chan S, Sidders B, Lee DH, Chan J, Bertozzi CR, Riley LW. 5′-Adenosinephosphosulphate reductase (CysH) protects Mycobacterium tuberculosis against free radicals during chronic infection phase in mice. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59:1744–1753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Chartron J, Carroll KS, Shiau C, Gao H, Leary JA, Bertozzi CR, Stout CD. Substrate Recognition, Protein Dynamics, and Iron-Sulfur Cluster in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Adenosine 5′-Phosphosulfate Reductase. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;364:152–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Chang MW, Belew RK, Carroll KS, Olson AJ, Goodsell DS. Empirical entropic contributions in computational docking: Evaluation in APS reductase complexes. J. Comput. Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1002/jcc.20936. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Huey R, Morris GM, Olson AJ, Goodsell DS. A semiempirical free energy force field with charge-based desolvation. J. Comput. Chem. 2007;28:1145–1152. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12). http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/dscb/diversity_explanation.html.

- (13).Wang Q, Dubé D, Friesen RW, LeRiche TG, Bateman KP, Trimble L, Sanghara J, Pollex R, Ramachandran C, Gresser MJ, Huang Z. Catalytic Inactivation of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase CD45 and Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B by Polyaromatic Quinones. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4294–4303. doi: 10.1021/bi035986e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.