Abstract

Summary: With their many replicates and their random layouts, Illumina BeadArrays provide greater scope fordetecting spatial artefacts than do other microarray technologies. They are also robust to artefact exclusion, yet there is a lack of tools that can perform these tasks for Illumina. We present BASH, a tool for this purpose. BASH adopts the concepts of Harshlight, but implements them in a manner that utilizes the unique characteristics of the Illumina technology. Using bead-level data, spatial artefacts of various kinds can thus be identified and excluded from further analyses.

Availability: The beadarray Bioconductor package (version 1.10 onwards), www.bioconductor.org

Contact: andy.lynch@cancer.org.uk

Supplementary information: Additional information and a vignette are included in the beadarray package.

1 INTRODUCTION

The existence of spatial artefacts in microarray imaging, and steps to identify, correct or remove them is an area of much research. Some methods are applied directly to intensity measurements using loess surfaces (Neuvial et al., 2006) or sliding windows (Song et al., 2007), while others work with deviations from average intensities calculated from replicate arrays (Reimersand Weinstein, 2005; Stokes et al., 2007a; Suárez-Fariñas et al., 2005; Upton and Lloyd, 2005), mismatch probes (Li and Wong, 2001) or replicate probes (Yuan and Irizarry, 2006). Opinions differ over whether to adjust affected probes by a bias correction step, to replace affected probes by imputed values or to simply exclude such probes.

Illumina microarrays consist of a random arrangement of beads, where each bead type (i.e. beads carrying the same probe) occurs on the array many times (typically approximately 30 times). The benefit of bead-level data for the detection of spatial artefacts on Illumina arrays has been known for some time (Dunning et al., 2006, 2007), however for Illumina microarrays there has been little work performed in this area. Illumina do remove ‘outliers’, but there is no spatial element to this step. Stokes et al. (2007b) have adapted their earlier work to address Illumina BeadArrays, but do not provide a tool for easy utilization.

Our preference is to adapt the Harshlight (Suárez-Fariñas et al., 2005) concept to Illumina data, and to this end we present BASH ‘BeadArray Subversion of Harshlight’ which forms part of the beadarray (Dunning et al., 2007) Bioconductor package.

2 METHODS

Harshlight, as applied to Affymetrix data, constructs an ‘Error Image’ for each array using the median values from replicate arrays. Three types of defect are then identified: ‘Compact’ defects where large numbers of outlying values form a connected cluster, ‘Diffuse’ defects where regions contain more outliers than would be anticipated by chance and ‘Extended’ defects that reflect a chip-wide instability (perhaps a severe gradient across the microarray). With BASH we seek to perform a similar function for Illumina BeadArrays, but taking both account and advantage of the unique characteristics of Illumina BeadArray technologies.

Illumina arrays use a hexagonal (not rectangular) grid, with concave edges and missing observations, and we must first identify this grid. BASH requires knowledge of the direct neighbours of a bead, and the identities of other ‘nearby’ beads. To avoid computationally intensive calculations at each step, the network of neighbours is fitted just once, and all later steps of BASH use this network to define their neighbourhoods. A bead's neighbours are defined as the n closest beads (3≤n≤6) for the largest n where the distance of the n-th farthest neighbour is less than  times the distance to the (n−1)-th farthest. This network generation routine is useful for many purposes and we provide direct access to it as a separate function.

times the distance to the (n−1)-th farthest. This network generation routine is useful for many purposes and we provide direct access to it as a separate function.

Compact defects are identified much as in Harshlight: outliers are identified, connected clusters of size greater than a specified minimum are labelled as compact defects and then an expansion and contraction step fills in any gaps. BASH differs from Harshlight in the compact defect step in three important ways: (i) the outliers are calculated within an array from the replicate beads, rather than from replicate arrays; (ii) the minimum size is specified rather than being estimated from simulated data; and (iii) the compact defect step is iterated rather than being performed once.

We do not estimate the minimum size from simulated data because content and layout varies between BeadArrays. To simulate data for each array would impose an unnecessary computational burden when, due to the redundancy built in to the Illumina platform, we can be conservative with our choice. BASH's iterative compact step is desirable because outliers are defined within an array using a threshold (by default Illumina's three median absolute deviations, MADs, from the median rule) rather than calling a fixed percentage of the beads as outliers based on errors calculated between arrays. Removing compact defects with BASH changes the rest of the ‘error’ values on the array, since estimated medians and MADs will change. Also, since we do not force a percentage of points on the array to be called as outliers, then we can be confident that the iterative process will terminate in reasonable time (although a maximum number of iterations can be specified). This approach allows for the detection of less-obvious compact defects that would otherwise have been overshadowed by more prominent defects.

The error images that we generate for use in BASH are all calculated within an array. The default BASH error image returns, on the log2 scale, the residual intensities after subtracting the median intensity for the appropriate bead-type. However, other filters can be applied to the error image including a local median subtraction, a local mean subtraction and a local MAD scaling. The appropriateness of these filters varies between technologies. In particular they have not proved useful for the arrays on a Sentrix Array Matrix, as these are too small to observe large gradients. Such filters are, though, useful for the larger BeadArrays, where low-frequency trends are observed, and in particular for the diffuse defect step.

Diffuse defects are areas containing unexpected numbers of (not necessarily connected) outliers. Compact defects should always be removed before running this step, and not subject to a contiguity test as performed in Harshlight, as BASH's within array calculation allows prominent compact defects to overshadow diffuse defects. The extended defect score is calculated much as Harshlight's, save for the use of our own definition of neighbourhood and error, but with BASH it can be used as a guide for manual intervention rather than automatically discarding the array. Large compact defects may drive such scores, or a spatial normalization may help to rectify the problem (perhaps manually removing the edges of the array where spatial normalization would be less robust). Alternatively, if the trend is approximately linear across the array, then we may simply observe increased variance in our estimates but little or no bias. Such an array can be down-weighted in an analysis (Dunning et al., 2008) rather than discarded.

BASH has been coded in R and C and is implemented in beadarray. Typically it takes less than 5 min per strip, and runs in <2.5 GB of RAM. A GUI for the manual drawing/editing of masks is also provided, for those occasions where the results of BASH are deemed undesirable. The BASH process returns, for each array, a list indicating beads that should be masked in all future summary and analysis steps. Due to the generally high levels of redundancy within the Illumina platform, we choose not to impute or correct observations within artefacts, but discard them knowing that we should still be able to estimate most of the properties that we desire. The representation of data in beadarray now allows for such information and the functions in beadarray will ignore beads that are so masked.

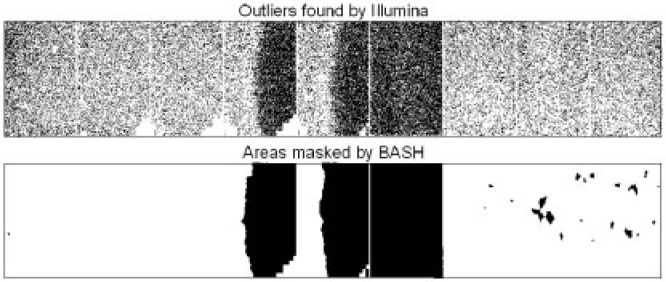

Figure 1 presents BASH's results for one strip of an Illumina HumanWG-6 V3.0 BeadArray. Illumina's approach identifies 81 166 (of 1 042 243) beads as outliers, while BASHmasks 272 440, picking up many beads that Illumina missed in the affected regions. Of the many outliers outside of the artefacts, some may still be excluded in our analysis, but only if they are still outliers after artefact removal. All strips on this array have technical replicates, and forthis example BASH reduces the squared differences between the twin strips, summed over bead typeswith a RefSeq match, by 36%.

Fig. 1.

Outlier detection in a HumanWG 6 microarray and the areas masked for removal by BASH (the segmental structure of the strip is visible).

3 DISCUSSION

BASH can be applied in a number of ways: as part of an automated preprocessing pipeline, to process arrays with apparent spatial artefacts, or merely to identify suspect arrays. BASH may require some initial tuning when dealing with a new technology or new laboratory, but has many adjustable parameters for doing so. There is scope for future improvement of BASH, such as incorporating transformations other than log2, or explicitly incorporating prior beliefs about the locations, sizes and shapes of defects. Additionally, questions such as ‘what is the best way to identify defects on two-colour Illumina platforms?’ remain to be answered, although BASH allows for flexibility in this regard.

Spatial defects in Illumina arrays have not been widely reported because the majority of Illumina data are examined only at the summary level. Our example shows the value of doing more than just accepting Illumina's outliers and provides an additional incentive to work at the bead level, which brings with it many additional benefits. BASH requires at least a list of bead locations, identities and intensities, and users may have to adjust their scanner settings to obtain this information. BASH does not need to be perfect to be useful. Removing some defects is better than not removing any, and removing some ‘good’ beads should not be catastrophic due to the redundancy on the platform.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank colleagues at the CRI for access to motivating data sets.

Funding: The University of Cambridge, Cancer Research UK; Hutchison Whampoa Limited.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Dunning M, et al. Quality control and low-level statistical analysis of Illumina BeadArrays. REVSTAT. 2006;4:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning MJ, et al. Beadarray: R classes and methods for Illumina bead-based data. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2183–2184. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning MJ, et al. Statistical issues in the analysis of Illumina data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuvial P, et al. Spatial normalization of array-CGH data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:264. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers M, Weinstein JN. Quality assessment of microarrays: visualization of spatial artifacts and quantitation of regional biases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JS, et al. Microarray blob-defect removal improves array analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:966–971. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes TH, et al. chip artifact CORRECTion (caCORRECT): a bioinformatics system for quality assurance of genomics and proteomics array data. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2007a;35:1068–1080. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9313-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes TH, et al. Extending microarray quality control and analysis algorithms to Illumina chip platform. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2007b;2007:4637–4640. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4353373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. ‘Harshlighting’ small blemishes on microarrays. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton GJG, Lloyd JC. Oligonucleotide arrays: information from replication and spatial structure. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4162–4168. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan DS, Irizarry RA. High-resolution spatial normalization for microarrays containing embedded technical replicates. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:3054–3060. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]