Abstract

Background

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) is highly metastatic. We have recently reported that activation of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK signaling pathway in MTC cells results in morphologic changes. We hypothesized that Raf-1--induced morphologic changes could be associated with alterations in cell--cell contact molecules, thereby affecting the metastatic potential of MTC cells.

Methods

An estradiol (E2)-inducible Raf-1 MTC cell line (TT-raf) was utilized in this study. Western blot analysis was used to confirm the Raf-1/MEK/ERK pathway activation and to measure levels of essential cell–cell contact molecules. Assays for cell adhesion and migration were performed to investigate the cell motility.

Results

E2 treatment of TT-raf cells resulted in the Raf-1/MEK/ERK pathway activation as evidenced by increased levels of phospho-MEK1/2 and -ERK1/2. This resulted in significant reductions in levels of essential cell–cell contact molecules including E-cadherin, β-catenin, and occludin. Importantly, activation of the Raf-1/ MEK/ERK pathway and the associated decrease in essential cell–cell contact molecules dramatically inhibited the abilities of adhesion and migration in MTC cells. Furthermore, treatment of Raf-1–activated cells with U0126, a specific inhibitor of MEK, abrogated these Raf-1–induced effects indicating that the suppression of the metastatic phenotype in MTC cells is a MEK-dependent pathway.

Conclusion

These data suggest that the Raf-1/MEK/ERK pathway regulates essential cell--cell contact molecules and metastatic phenotype of MTC cells. Thus, these findings provide further insight into the key steps in the metastatic progression of MTC.

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) is a relatively rare neuroendocrine tumor, accounting for 3–5% of all thyroid malignancy and causing significant morbidity and mortality.1 Surgery is the only potentially curative therapy for patients with MTC, but complete operative resection is often impossible owing to widespread metastases.2 This emphasizes the need for the development of new treatment strategies.

We have previously reported that the Raf-1 signaling pathway plays important roles in MTC biology.3 More recently, we observed that Raf-1 activation results in dramatic changes in MTC cellular appearance, causing the cells to become flatter and develop distinct margins with gaps between adjacent cells.4 Given our previous findings and recent observations, we hypothesized that Raf-1–induced morphologic changes could be associated with alterations in essential cell–cell contact molecules, thereby affecting metastatic potential. In this study, we investigated the role of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK signaling pathway in the regulation of essential cell–cell contact molecules and the metastatic phenotype of MTC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Human MTC cells (TT) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va) and maintained in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md) supplemented with 18% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Life Technologies). TT-raf cells were kindly provided by Dr B. Nelkin (The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md) and maintained in RPMI 1640 as described.5 The expression of Δraf-1:ER protein and activation of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK signaling pathway in the stably transfected cells, TT-raf, have been characterized previously. 6 To induce Raf-1 activity in TT-raf cells, 1 µmol/L β-estradiol (E2) was added to the medium; an equivalent dilution of ethanol, the carrier for the E2, was used to treat control cells. For the MEK inhibitor studies, cells were pretreated with 10 µmol/L 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis[2-aminophenylthio] butadiene (U0126; Sigma-Aldrich) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour before the addition of E2 or ethanol. All cells were maintained in 5% CO2 in air at 37°C in a humidified incubator.

Western blot analysis

The cell lysates were prepared as described previously.7 Total protein concentration was quantified with a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, Ill). Denatured cellular extracts (20–40 µg) were resolved by 8% or 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif), blocked in milk and incubated with appropriate antibodies. Antibodies were diluted as follows: ERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2, phospho-MEK1/2, E-cadherin, β-catenin (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, Mass), occludin (1:200; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, Calif), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH; 1:10,000; Trevigen, Gaithersburg, Md). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) was used as secondary antibody. For protein visualization of the signal, the membranes were visualized with the Immunstar kit (Bio-Rad).

Cell adhesion assays

Fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted to 10 µg/mL in serum-free medium (SFM) and dispensed to 12-well plates that were then incubated at room temperature for at least 1 hour to allow adsorption. The plates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), blocked with 0.2% heat-inactivated bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour and then washed with SFM (2 × 10 minutes). Cultured cells were detached from culture plates with 0.1% trypsin and 0.53 mmol/L ethylene diamine triacetic acid, suspended in SFM containing 0.25 mg/mL of soybean trypsin inhibitor and then centrifuged. The cells were resuspended in SFM, plated onto fibronectin-coated plates, and incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C. The wells were washed with PBS and the numbers of adherent cells per high-power microscope field were counted. All experiments were conducted in quadruplicate.

Migration assays

The assays were conducted using 8.0-µm pore size and 6.5-mm diameter transwell filters (Costar, Cambridge, Mass). The undersurface of the polycarbonate membrane of the chamber was coated with fibronectin (10 µg/mL in PBS; 2 hours at 37°C). The membrane was washed in PBS to remove excess ligand, and the lower chamber was filled with 500 µL of 10% fetal bovine serum--containing medium. Cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 per well in SFM in the upper chamber of the insert, and cells were allowed to migrate through the fibronectin-coated chamber for 8 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2. Nonmigrated cells on the upper membrane were removed with a cotton swab. Migrated cells were fixed for 5 minutes in methanol, stained with 0.6% hematoxylin and 0.5% eosin, and then counted. All experiments were conducted in quadruplicate.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc testing (SPSS software version 10.0; SPSS, Chicago, Ill) was used for statistical comparisons. P < .05 was considered significant. Data are presented as mean values ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Raf-1 activation decreases expression of essential cell--cell contact molecules in MTC cells

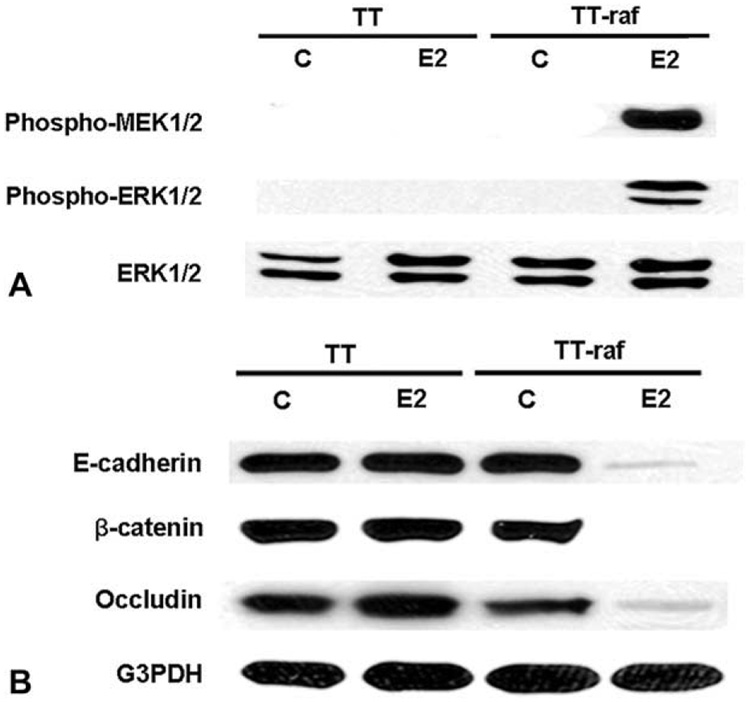

TT and TT-raf cells were treated with E2 or ethanol (control), and the total cellular extracts were isolated and analyzed by Western blot for downstream targets of the Raf-1 signaling pathway. Inactive, unphosphorylated ERK1/2 was present at high levels, whereas there were no detectable levels of phosphorylated MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 in TT and TT-raf cells at baseline (Fig 1, A). However, treatment of TT-raf cells with E2 resulted in Raf-1 activation manifested by a marked increase in the levels of phosphorylated MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 within 48 hours (Fig 1, A). Because Raf-1 activation led to MTC cellular morphology changes,4 we analyzed the effect of Raf-1 activation in TT cells on the expression of essential cell–cell contact molecules by Western blot. As shown in Fig 1, B, cell–cell contact molecules such as E-cadherin, β-catenin, and occludin were present at high levels in TT and TT-raf cells at baseline. E2-treated TT cells also had high levels of these proteins. However, treatment of TT-raf cells with E2 led to a significant reduction in the expression of these cell–cell contact molecules.

Fig. 1. Raf-1 activation decreases the levels of cell–cell contact molecules in MTC cells.

TT and TT-raf cells were treated with ethanol (C) and estradiol (E2) for 48 hours, and the total cellular extracts were analyzed by Western blot to examine activation of the Raf-1 signaling pathway. Total ERK1/2 and G3PDH were used to confirm equal protein loading. (A) Treatment of TT-raf cells with E2 led to high levels of phospho-MEK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2, confirming the Raf-1 signaling pathway activation. (B) Treatment of TT-raf cells with E2 resulted in a significant decrease in the expression of E-cadherin, β-catenin, and occluding.

Raf-1 activation suppresses adhesion and migration of MTC cells

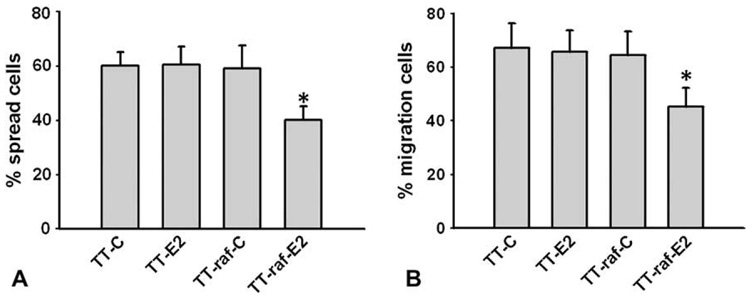

Although Raf-1 activation resulted in a broad decrease in the expression of essential cell--cell contact molecules, the affects of these alterations on cellular adhesion, migration and metastatic potential remain unresolved. Because fibronectin is among the best characterized proteins of the extracellular matrix,8,9 we utilized the fibronectin adhesion-promoting peptide to access the effect of Raf-1 activation on cell adhesion in MTC cells. TT and TT-raf cells were treated with E2 or ethanol (control) for 48 hours. The cells were detached and plated on fibronectin-coated plates and observed for spreading. By 90 minutes, about 60% of the control-treated or E2-treated TT cells spread onto fibronectin. Control-treated TT-raf cells had similar levels of cell adhesion. In contrast, E2-induced Raf-1 activation in TT-raf cells led to a reduction in cell spreading (Fig 2, A). Next we examined the adhesion-mediated migration property of MTC cells by transwell experiments. TT and TT-raf cells treated with E2 or control for 48 hours were seeded into the upper chambers of the inserts and allowed to migrate through the fibronectin-coated chambers for 8 hours. As shown in Fig 2, B, the cell migration rate of control-treated TT cells was about 68%. E2-treated TT and control-treated TT-raf cells had similar levels of migration. In contrast, E2-treated TT-raf cells showed a significant decrease in cell migration. Taken together, these data indicated that Raf-1 activation suppressed adhesion and migration in MTC cells.

Fig. 2. Raf-1 activation suppresses adhesion and migration of MTC cells.

TT and TT-raf cells were treated with ethanol (C) and estradiol (E2) for 48 hours, and assays for cell adhesion and migration were performed. ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc testing was used for statistical comparisons. *P < .05 was considered significant. Data are presented as mean values ± standard deviation. (A) Detached cells were plated on fibronectin (FN)-coated plates for 90 minutes and spreading cells were counted. Treatment of TT-raf cells with E2 led to a significant reduction in cell s0preading. (B) The cells were seeded in the upper chamber of the insert and allowed to migrate through the fibronectin-coated chamber for 8 hours. Treatment of TT-raf cells with E2 resulted in significant decrease in cell migration.

Raf-1--induced effects in MTC cells through a MEK-dependent pathway

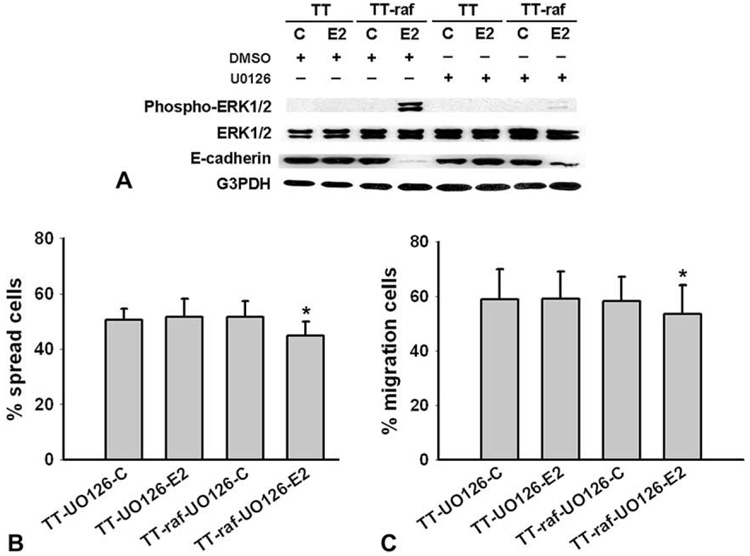

To examine whether or not Raf-1--induced effects in TT cells were dependent on MEK activation, TT and TT-raf cells were incubated for 1 hour in the presence of the MEK inhibitor U0126 (10 µmol/l) and subsequently treated with either E2 or control for 48 hours. As shown in Fig 3, A, treatment with U0126 dramatically inhibited ERK1/2 phosphorylation in E2-treated TT-raf cells. Importantly, absence of phosphorylated ERK1/2 was associated with reexpression of E-cadherin. To substantiate the results obtained with U0126, we examined whether blocking MEK phosphorylation prevented the Raf-1–induced reduction in cell adhesion. As shown in Fig 3, B, the levels of cell spreading were unaffected by the addition of U0126 in control-treated or E2-treated TT cells or control-treated TT-raf cells. However, the presence of U0126 prevented the Raf-1–induced adhesion suppression in E2-treated TT-raf cells. Similar effects of U0126 were also observed in migration assays. U0126 had no effect on cell migration in control-treated TT cells, E2-treated TT cells, or control-treated TT-raf cells (Fig 3, C). As predicted, U0126 blocked the Raf-1–induced reduction in migration in TT-raf cells treated with E2 (Fig 3, C). These results demonstrated that U0126 abrogated the Raf-1–induced decrease in adhesion and migration, indicating that these Raf-1–induced effects were through an MEK-dependent pathway.

Fig. 3. The MEK inhibitor U0126 blocks Raf-1–induced effects in MTC cells.

TT and TT-raf cells were incubated for 1 h in the absence or presence of MEK inhibitor U0126 (10 µmol/L) and were subsequently treated with either estradiol (E2) or ethanol (C) for 48 hours. (A) Western blot revealed that U0126 blocked ERK1/2 phosphorylation, and led to the reexpression of E-cadherin in E2-treated TT-raf cells. Total ERK1/2 and G3PDH were used to confirm equal protein loading. (B) U0126 blocked Raf-1–induced adhesion suppression in E2-treated TT-raf cells. (C) U0126 blocked the Raf-1–induced reduction in migration in E2-treated TT-raf cells. ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc testing were used for statistical comparisons. *P < .05 was considered significant. Data are presented as mean values ± SD.

DISCUSSION

Tumor metastases form after a variety of adhesive interactions between cancer cells and host tissues, which may be mediated by cell contact molecules.10 Reduced expression of ≥1 essential cell–cell contact molecules has been associated with extended invasive and progressive behavior of cancer cells in lung cancer, melanoma, colorectal cancer, epithelial ovarian carcinoma, and breast ductal carcinomas.11–15 However, several studies show that elevated expression of cell–cell contact molecules promotes cell motility in some other cell types, such as human ovarian carcinoma cells.16 In this study, we found that metastatic MTC cells had high levels of E-cadherin as well as β-catenin and occludin. However, activation of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK signaling pathway markedly decreased the expression of essential components of cell–cell contacts including E-cadherin, β-catenin, and occludin. E-cadherin, which is the prototypical member of the classic cadherin family, is a major component of the adherens junction (AJ), where it provides cell–cell adhesion between molecules on adjacent cells.17 At the AJ, β-catenin attaches to the C-terminal region of E-cadherin and then to α-catenin, through which the complex is linked to the actin cytoskeleton.17 Formation of the AJ through E-cadherin is also associated with the formation and localization of the tight junction proteins, such as the integral membrane protein occludin.18 Therefore, Raf-1–induced reduction in expression of E-cadherin, β-catenin, and occludin suggested that the Raf-1/MEK/ERK signaling pathway plays an important role in the regulation of cell–cell contacts in MTC cells. Loss of these cell–cell contact molecules may prevent tumor cells adhere to the endotheliumand penetrate the endothelial junction in metastatic target organs. This notion is supported by the findings that Raf-1 activation also inhibits adhesion and migration in MTC cells. Furthermore, we found that U0126 abrogated these Raf-1–mediated reductions in E-caderin expression, cell adhesion, and migration, indicating that these effects are MEK dependent. Recently, we have reported that in vivo activation of Raf-1 inhibits tumor growth and development in a xenograftmodel of human MTC.19 These results provide additional evidence that the Raf-1/MEK/ERK pathway plays an important role in the regulation of MTC tumor development.

In conclusion, this is the first description suggesting that the Raf-1/MEK/ERK pathway regulates the expression of components of cell--cell contacts in MTC cells. Importantly, activation of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK pathway and the associated decrease in cell--cell contact molecules dramatically inhibited the abilities of adhesion and migration in MTC cells. Furthermore, MEK inhibitor U0126 blocked these Raf-1--mediated reductions in adhesion and migration, indicating that the suppression of the metastatic phenotype in MTC cells is MEK dependent. These findings provide further insight into the key steps in the metastatic progression of MTC.

DISCUSSION

Dr Kepal Patel (New York, NY)

As we heard earlier today, the MAPK pathway seems to be upregulated and involved in invasion and migration of papillary thyroid carcinoma. I guess you are suggesting the counterintuitive, that it actually decreases the invasion with Raf-1 activation.

Dr Li Ning (Madison, Wis)

Although Raf-1 acts as an oncogene in other types of cancer cells, in neuroendocrine tumor cells, it acts as a tumor suppressor. Therefore, we explored the mechanism of growth inhibition. In this study, we found that Raf-1 activation decreased the invasion experiments in fibronectin treated plates.

Dr Lawrence T. Kim (Little Rock, Ark)

I am a little bit puzzled. You showed the data about the adherens junctions proteins, but I think of those mostly associated with epithelial cells and not with cells like these. And also the behavior data you showed us, the migration and adhesion I think of being associated with integrin and you use the transwell plates with fibronectin and so forth, which is an integrin. What is the relationship? Did you look integrin protein levels and at what levels were activity? Also, what led you to look at the adherens junctions at all?

Dr Li Ning (Madison, Wis)

We had earlier published Raf-1 activation leads to change in the morphology of the cells. In carcinoid cells, we observed distinct cellular border and in medullary cells we observed rounding of the cells after Raf-1 activation. This observation leads us to look for the levels of cytoskeletal proteins such as adherens junctions proteins. However, we have not looked at the levels of integrin in this study and we speculate that the levels may be down in Raf-1–activated cells.

Dr Bhuyanejh Singh (New York, NY)

Very provocative findings, and some things that are counterintuitive in terms of some of the results that you see. I think Dr Patel brought up the issue of BRAF mutation. It certainly mutated in a lot of neuroendocrine tumors, melanoma being the prototype for looking for BRAF mutation, and in those systems it actually acts as an oncogene. So, the first question is, how is it in different tumor systems that you think that it is inactivating the invasion pathway? The other thing is, usually loss of adhesion is associated with increased invasion rather than decreased invasion, and so you are making at these cells less adherent to the local architecture. Why do you think that you are then seeing less invasion in these cells rather than more invasion in these cells?

Dr Li Ning (Madison, Wis)

We are also puzzled by the finding that Raf-1 activation reduces neuroendocrine markers and growth in neuroendocrine tumors. We have seen other similar pathway such as Notch is inactivated in these tumor types. Overexpression of Raf-1 or Notch1 (both are oncogenes in other tumors) in these cells lead to a reduction in tumor growth. We have published TT-raf murine xenograft model in which activation of the Raf-1–signaling pathway immediately after the injection of cells subcutaneously did not develop any tumor. Also, activation of Raf-1 after the tumor development lead to significant tumor growth reduction compared to control tumors. Perhaps this indicates that once the Raf-1 pathway is activated, the cells are not able to make any solid tumor. In the present study, Raf-1 activation decreases the cell invasion and we speculate that the cells are not able to attach to the membrane after invasion and, therefore, we observed fewer cells in the transwell studies.

Dr W. Bradford Carter (Tampa, Fla)

Two points. One is, Denilla showed very nicely 20-some years ago that you have to have some adhesion or the cell can’t migrate. So, I am wondering if you consider this adhesion in migration strategy farther down-stream until you have actually lost enough of the adhesive molecules that it can actually migrate. So, I agree with the other comments that it is something you need to justify. The other thing is that usually we think of the E-cadherin in the epithelial to mesenchymal transition for tumors. And that is all regulated through some transcriptional regulators—specifically twist, snail, and slug have been commonly used. And I am curious whether you have looked at those transcription regulators and are they in this pathway, and how do they affect the promoter for your E-cadherin?

Dr Li Ning (Madison, Wis)

We are aware that cell migration requires adhesion. The present study reports the preliminary experiments to understand the mechanism of growth inhibition. We are in the process of developing an in vivo animal metastasis model. This model will shed some lights on the adhesion and migration status of the cells after Raf-1 activation. The answer to your last question is we have not yet studied transcriptional regulators of E-cadherin and other cytoskeletal proteins after activating the Raf-1 pathway.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the American Cancer Society Research Scholars Grant 05-08301TBE; National Institutes of Health RO1 CA109053; NIH-R21CA117117; American College of Surgeons George H.A. Clowes Jr. Memorial Research Career Development Award; Vilas Foundation Research Grant; Carcinoid Cancer Foundation Research Award; Doctors Cancer Foundation Award and the Society of Surgical Oncology Clinical Investigator Award.

The authors thank Mrs. Mary A. Ndiaye and Mr. Eric Wendt for editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball DW. Medullary thyroid cancer: monitoring and therapy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H, Roberts JR, Ball DW, Eisele DW, Baylin SB, Udelsman R, et al. Effective long-term palliation of symptomatic, incurable metastatic medullary thyroid cancer by operative resection. Ann Surg. 1998;227:887–895. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199806000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunnimalaiyaan M, Chen H. The Raf-1 pathway: a molecular target for treatment of select neuroendocrine tumors? Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:139–142. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200602000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sippel RS, Carpenter JE, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Chen H. The role of human achaete-scute homolog-1 in medullary thyroid cancer cells. Surgery. 2003;134:866–871. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00418-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H, Carson EB, Baylin SB, Nelkin BD, Ball DW. Differentiation of medullary thyroid cancer by C-Raf-1 silences expression of the neural transcription factor human achaete-scute homolog-1. Surgery. 1996;120:168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson EB, McMahon M, Baylin SB, Nelkin BD. Ret gene silencing is associated with Raf-1-induced medullary thyroid carcinoma cell differentiation. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2048–2052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ning L, Greenblatt DY, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Chen H. Suberoyl bis-hydroxamic acid activates Notch1 signaling and induces apoptosis in medullary thyroid carcinoma cells. Oncologist. 2008;13:98–104. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2007-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engbring JA, Kleinman HK. The basement membrane matrix in malignancy. J Pathol. 2003;200:465–470. doi: 10.1002/path.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim Y, Park H, Jeon J, Han J, Kim J, Jho EH, et al. Focal adhesion kinase is negatively regulated by phosphorylation at tyrosine 407. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10398–10404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voura EB, Sandig M, Siu CH. Cell–cell interactions during transendothelial migration of tumor cells. Microsc Res Tech. 1998;43:265–275. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19981101)43:3<265::AID-JEMT9>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bremnes RM, Veve R, Hirsch FR, Franklin WA. The E-cad-herin cell–cell adhesion complex and lung cancer invasion, metastasis, and prognosis. Lung Cancer. 2002;36:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGary EC, Lev DC, Bar-Eli M. Cellular adhesion pathways and metastatic potential of human melanoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:459–465. doi: 10.4161/cbt.1.5.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hlubek F, Spaderna S, Schmalhofer O, Jung A, Kirchner T, Brabletz T. Wnt/FZD signaling and colorectal cancer morphogenesis. Front Biosci. 2007;12:458–470. doi: 10.2741/2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu C, Cipollone J, Maines-Bandiera S, Tan C, Karsan A, Auersperg N, et al. The morphogenic function of E-cad-herin-mediated adherens junctions in epithelial ovarian carcinoma formation and progression. Differentiation. 2008;76:193–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park D, Kåresen R, Axcrona U, Noren T, Sauer T. Expression pattern of adhesion molecules (E-cadherin, alpha-, beta-, gamma-catenin and claudin-7), their influence on survival in primary breast carcinoma, and their corresponding axillary lymph node metastasis. APMIS. 2007;115:52–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong A, Maines-Bandiera SL, Roskelley CD, Auersperg N. An ovarian adenocarcinoma line derived from SV40/E-cad-herin-transfected normal human ovarian surface epithelium. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:430–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Angst BD, Marcozzi C, Magee AI. The cadherin superfamily. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:625–626. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halbleib JM, Nelson WJ. Cadherins in development: cell adhesion, sorting, and tissue morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3199–3214. doi: 10.1101/gad.1486806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaccaro AM, Chen H, Kunnimalaiyaan M. In-vivo activation of Raf-1 inhibits tumor growth and development in a xeno-graft model of human medullary thyroid cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:849–853. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000217424.36961.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]