Abstract

Objective

Myofibrillar myopathies (MFM) are morphologically distinct but genetically heterogeneous muscular dystrophies in which disintegration of Z disks and then of myofibrils is followed by ectopic accumulation of multiple proteins. Cardiomyopathy, neuropathy, and dominant inheritance are frequent associated features. Mutations in αB-crystallin, desmin, myotilin, Zasp, or filamin-C can cause MFM, and were detected in 32/85 patients of the Mayo MFM cohort. Bag3, another Z-disk associated protein, has antiapoptotic properties and its targeted deletion in mice causes fulminant myopathy with early lethality. We therefore searched for mutations in BAG3 in 53 unrelated MFM patients.

Methods

We searched for mutations in BAG3 by direct sequencing and excluded polymorphism using allele-specific PCR in relatives and 200 control subjects. We analyzed structural changes in muscle by histochemistry, immunocytochemistry and electron microscopy, examined mobility of the mutant Bag3 by nondenaturing electrophoresis, and searched for abnormal aggregation of the mutant protein in COS-7 cells.

Results

We identified a heterozygous p.Pro209Leu mutation in three patients. All presented in childhood, had progressive limb and axial muscle weakness, and developed cardiomyopathy and severe respiratory insufficiency in their teens; two had rigid spines and one a peripheral neuropathy. Electron microscopy showed disintegration of Z disks, extensive accumulation of granular debris and larger inclusions, and apoptosis of 8% of the nuclei. On nondenaturing electrophoresis of muscle extracts, the Bag3 complex migrated faster in patient than control extracts, and expression of FLAG-labeled mutant and wild-type Bag3 in COS cells revealed abnormal aggregation of the mutant protein.

Interpretation

We conclude mutation in Bag3 defines a novel severe autosomal dominant childhood muscular dystrophy.

Myofibrillar myopathies (MFMs) represent a morphologically distinct but genetically heterogeneous subset of muscular dystrophies. Cardiomyopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and dominant inheritance are frequent associated features.1–7 The histologic findings are similar in that disintegration of the myofiber Z disk is an early pathologic alteration; this is followed by disintegration of the myofibrils, aggregation of degraded filaments into pleomorphic granular or hyaline inclusions, and ectopic expression of multiple Z-disk related and other proteins in the affected muscle fibers.3,8,9 Mutations in desmin,1,10,11 αB-crystallin,2,12 myotilin,4,5 ZASP,6,13 and filamin C7 have been identified as causes of MFM. Each mutated protein is an integral part of the Z disk or is closely associated with it. Based on the assumption that early structural alteration of the Z-disk heralds a mutation in a Z disk related protein, we traced the disease to a mutation in one of the above proteins in 32 of 85 patients of the Mayo MFM cohort.

In most MFM patients, the disease presents after the fourth decade and evolves slowly, but some patients with desmin mutations present in the first or second decade and experience early mortality due the cardiomyopathy.14 We here trace the cause of MFM in 3 unrelated children to a single missense mutation in the antiapoptotic Bag3 (Bcl-2-associated athanogene-3) protein encoded by BAG3. We considered Bag3 a candidate for MFM because it localizes to and co-chaperones the Z disk, and because its targeted deletion in mice results in a fulminant myopathy with early lethality.15 In Patient 1, electron microscopy observation of nuclear apoptosis, was an additional clue pointing to BAG3 as the candidate gene. The three patients differ from most other MFM patients in the early onset and rapid evolution of their illness and presence of a rigid spine in two.

Bag3, also referred to as CAIR-1 or Bis, is a multidomain co-chaperone protein interacting with many other polypeptides. Like other members of the Bag family, it harbors a C-terminal BAG domain (residues 418-498) which mediates interaction with heat shock protein (Hsp) 70 and the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, and a proline rich domain (residues 302-417) that interacts with WW-domain proteins implicated in signal transduction and with Src-3 homology (SH3)-domain proteins such a phospholipase Cγ-1 which also participates in antiapoptotic pathways (see Fig. 1A). Bag3 also has a unique N-terminal WW domain (residues 21-55) which binds proline-rich sequences. Bag3 forms a stable complex with the small Hsp 8 and thereby participates in the degradation of misfolded or aggregated proteins.16–18 Bag3 is strongly expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscle and at a lower level in other tissues.15 To date, no spontaneous mutation in humans has been described in any member of the Bag family of proteins.

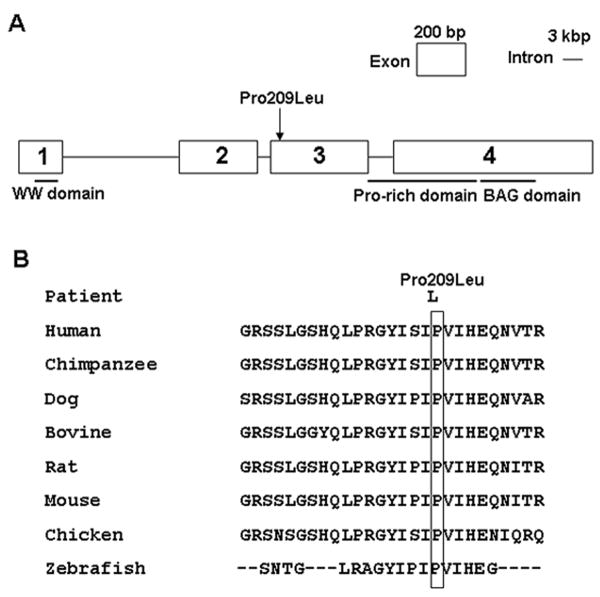

Fig. 1.

(A) Scheme of the genomic structure of BAG3 and the identified mutation. (B) Alignment of amino acid sequences of human, chimpanzee, dog, bovine, rat, mouse, chicken, and zebra fish.

Methods

Patients

Three patients, 1 girl and 2 boys were investigated. Clinically affected limb muscles, grade 3 to 4 on the MRC scale, were biopsied in each patient. Mutation analysis was done on DNA isolated from peripheral blood. All studies were in accord with the guidelines of the Mayo Institutional Review Board.

Mutation Analysis

Polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) primers were designed to analyze all exons and their flanking noncoding regions of BAG3 (GenBank reference number: AC012468). PCR-amplified fragments were sequenced using fluorescently labeled dideoxy terminators. BAG3 nucleotides were numbered according to the mRNA sequence (GenBank reference no: NM_004281). Allele-specific PCR was used to screen for mutations in families of Patient 1 and 2 and in unrelated normal controls.

Histochemistry and Immunostains

Conventional histochemical studies were performed and amyloid deposits were visualized with the Congo red stain and rhodamine optics as described.19

Six to 10-μm-thick cryostat sections were treated with monoclonal antibodies against, myotilin (Novocastra, Bannockburn, IL), desmin (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), αB-crystallin (Stressgen, Ann Arbor, MI), dystrophin (Novocastra), neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) (Cell Sciences, Canton, MA), ubiquitin (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), heat shock proteins 27 (Novocastra) and 8 (GeneTex, San Antonio, TX), and Bcl-2 (Dako). Bag3 was immunolocalized with a polyclonal antibody (gift of Dr. Shinichi Takayama) The immunoreactive sites were then visualized with the immunoperoxidase method as previously described.3 Adjacent sections in the series were stained with trichrome. Controls consisted of replacement of monoclonal antibodies with nonimmune IgG of the same subclass and concentration as the primary antibody. The modified TUNEL method was used to search for apoptotic nuclei at the light microscopy level using the ApopTag Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Chemicon) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy was performed on a muscle specimen fixed at rest length and processed for electron microscopy by standard methods.19

Immunoblot analysis

Native proteins were extracted from muscle of Patient 1 by Native Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and electrophoresed on 4–12% NuPAGE Tris-glycine minigel (Invitrogen) under nondenaturing conditions and blotted on nitrocellulose membrane. The blots were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to Bag3, and then developed by the alkaline phosphatase method as described.12

Expression Studies

Wild-type BAG3 cDNA was cloned directly from a control cDNA into N-terminal FLAG-epitope-tagged pCMV-Tag2 expression vector (Stratagene, Santa Clara CA). We then introduced the 626C>T mutation into Bag3 cDNA in the expression vector using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Presence of the mutation and absence of unwanted mutations were confirmed by sequencing the entire insert.

COS (SV-40 transformed monkey kidney fibroblast)-7 cells (American Type Cell Culture Collection, Rockville, MD). were transfected with mutant or wild type FLAG-tagged BAG3 cDNA using GeneJammer (Stratagene). The transfected cells were visualized with monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and FITC conjugated second antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). The preparations were examined with a Zeiss Axiovert epifluorescence microscope using apotome optics, Axiovision 4.4 software, and a 63x objective (numerical aperture 1.4).

Results

Mutation Analysis

Direct sequencing of all exons and flanking untranslated regions of BAG3 in 53 unrelated MFM patients who carried no mutations in desmin, αB-crystallin, myotilin, ZASP or filamin C revealed a heterozygous p.Pro209Leu (c.626C>T) mutation in exon 3 in 3 patients (Fig. 1A). The mutation is not present in 400 alleles of 200 unrelated controls, in unaffected parents of Patients 1 and 2, and in the unaffected sibling of Patient 2. No DNA was available from asymptomatic parents of Patient 3 and asymptomatic sibling of Patient 1. Thus in each case the mutation likely arose in the parental germline. The mutated proline residue is evolutionarily conserved across vertebrate species (Fig. 1B). The mutation is likely dominant because it exerts its deleterious effects at a heterozygous state, DNA from asymptomatic parents revealed no mutation and, with one possible exception in which hemizygosity was not excluded,10,20 all MFM patients with known mutations were heterozygous, and in all MFM patients in whom a full family history was available, the pattern of inheritance was dominant.

Clinical Features

Patient 1, a 15 year-old-boy, was a toe walker since early childhood. In his early teens, he developed a restrictive cardiomyopathy and received a heart transplant at the age of 13 years. Two years later he had severe diffuse muscle weakness and atrophy, contractures at the knees and ankles, bilateral diaphragm paralysis, respiratory insufficiency, and a 3-fold above normal serum CK level. EMG and nerve conduction studies were unavailable.

Patient 2, a 17-year-old girl, presented at age 13 years with scoliosis, rigid spine, and easy fatigability. By the age of 14 years, she developed restrictive respiratory insufficiency and required assisted ventilation at night. By the age of 15 years, she had hypernasal speech, and axial and moderately severe distal more than proximal muscle weakness. Her spinal stiffness and proximal weakness progressed considerably between the age 15 and 17 years. EMG and nerve conduction studies revealed myopathic motor unit potentials and an axonal and demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. The echocardiogram showed a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The serum CK was elevated 6-fold above the upper limit of normal.

Patient 3, an 11-year-old-boy, was a toe-walker as a toddler. Since the age of 7 years, he had progressive leg weakness and fatigability and a valgus ankle deformity. At the age of 11 years, he had moderate proximal muscle weakness, thoracic scoliosis, and a rigid spine predominantly affecting the cervical region. The echocardiogram showed a restrictive cardiomyopathy with a slightly large left atrium, and trivial pulmonary and mitral regurgitation. The patient’s symptoms progressed rapidly. By the age of 12 years, he had marked weakness of axial and proximal limb muscles, scapular winging, reduced forced vital capacity, and a 15-fold elevation of the serum CK level above the upper limit of normal. EMG and nerve conduction studies were unavailable. In the 13th year of life he developed respiratory insufficiency. He did not tolerate nocturnal ventilatory support and died following a chest infection.

Structural Observations

Routine histochemical studies were performed in each patient. Immunostains and electron microscopy studies were done on a vastus lateralis muscle specimen obtained from Patient 1 at the age of 15 years. The muscle fibers varied pathologically from 10 to more than a 100 μm in diameter. Some of the larger fibers were subdividing by splitting. Some fibers were necrotic and a comparable number of fibers were regenerating. A fair number of fibers harbored internal nuclei. Scattered fibers displayed small vacuoles. Numerous fibers displayed structural alterations consisting of replacement of the normal myofibrillar markings by small dense granules, or larger hyaline masses, or amorphous material that stained blue or blue-red in trichrome sections (Figs. 2A and 2D). The hyaline masses were devoid of oxidative enzyme activity, but were often surrounded by a zone of increased enzyme activity (Fig. 2B). Numerous abnormal fibers displayed intense congophilia (Fig. 2C), consistent with the presence of β-pleated sheets in the accumulating abnormal material. Increases of acid phosphatase occurred in relation to many of the cytoplasmic inclusions. Increases of nonspecific esterase appeared in many small and some larger fibers. There was a mild to moderate increase in perimysial fibrous and fatty connective tissue.

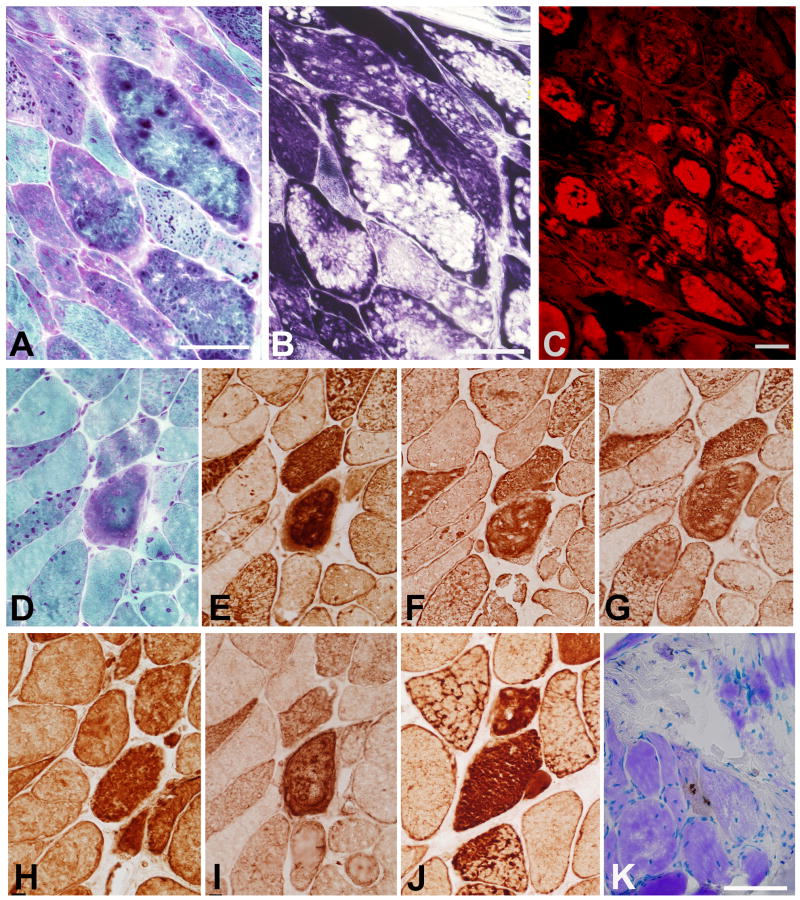

Fig. 2.

(A-C): Characteristic histologic findings in trichrome (A), NADH dehydrogenase (B) and Congo red (C) stained sections. (D-J): sections stained trichromatically (D), and immunoreacted for Bag3 (E), αB-crystallin (F), desmin (G), gelsolin (H), NCAM (I), and heat shock protein 27 (J). Note abnormal accumulation of each protein in the structurally abnormal fibers. (K): Modified TUNEL stain reveals apoptotic nuclei in two adjacent fibers. Panels A and B, and panels D-J are nonconsecutive sections from two different series. For panels (A-C), Bars = 100 μm; for panels (D-K), bar in K = 50 μm.

The abnormal fibers displayed strong ectopic immunoreactivity for Bag3 (Fig. 2E), αB-crystallin (Fig. 2F), desmin (Fig. 2G), gelsolin (Fig. 2H), NCAM (Fig. 2I), myotilin, ubiquitin and dystrophin. In normal muscle, Bag3 was immunolocalized to the Z-disk (colocalizing with myotilin) and the sarcolemma. Similar localization, as well as ectopic localizations were found in other cases of MFM. Bag3 is co-chaperone for other heat shock proteins and has antiapoptotic properties. Therefore we also immunolocalized Hsp 27, another small heat shock protein with antiapoptotic properties present in muscle and other tissues 21 (Fig. 2J), the 22 kDa Hsp B8 which interacts directly with Bag318, and the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-222 in patient and MFM control muscle specimens. We detected strong immunoreactivity for Hsp 27, Hsp B8, and Bcl-2 in abnormal fibers in the patient as well as in other subtypes of MFM.

The modified TUNEL stain revealed apoptotic nuclei in a small proportion of the fibers (Fig. 2K).

Electron microscopy studies revealed that minimally affected myofibers displayed Z disk streaming and accumulation of small pleomorphic dense structures between the myofibrils (Fig. 3A) In more severely affected fibers large lakes of small pleomorphic dense structures surrounded myofibrillar remnants (Fig. 3B and C). Large dense bodies composed of fragmented filaments (Fig. 3B), aggregates of mitochondria, and dilated vesicles (Fig. 3C) were present in places voided by the myofibrils.

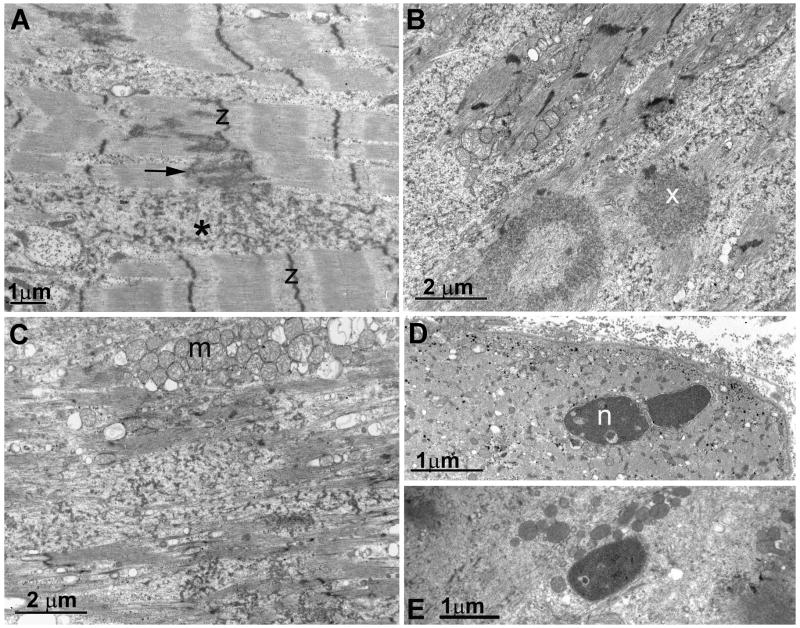

Fig. 3.

Electron microscopy. (A) Z-disk (Z) streaming (arrow) and accumulation of small pleomorphic dense structures between the myofibrils (asterisk). (B) More advanced alterations include disintegration and disarray of the myofibrils, aggregation of fragmented and degraded filaments into dense inclusions (X), and accumulation of granular debris. (C) Further destructive changes result in loss of myofibrillar integrity, appearance of dilated vesicles, and aggregation of mitochondria into clusters (m). (D and E) Apoptotic nuclei (n) in a fiber with dilated vesicles (D), and in a highly degenerate fiber (E).

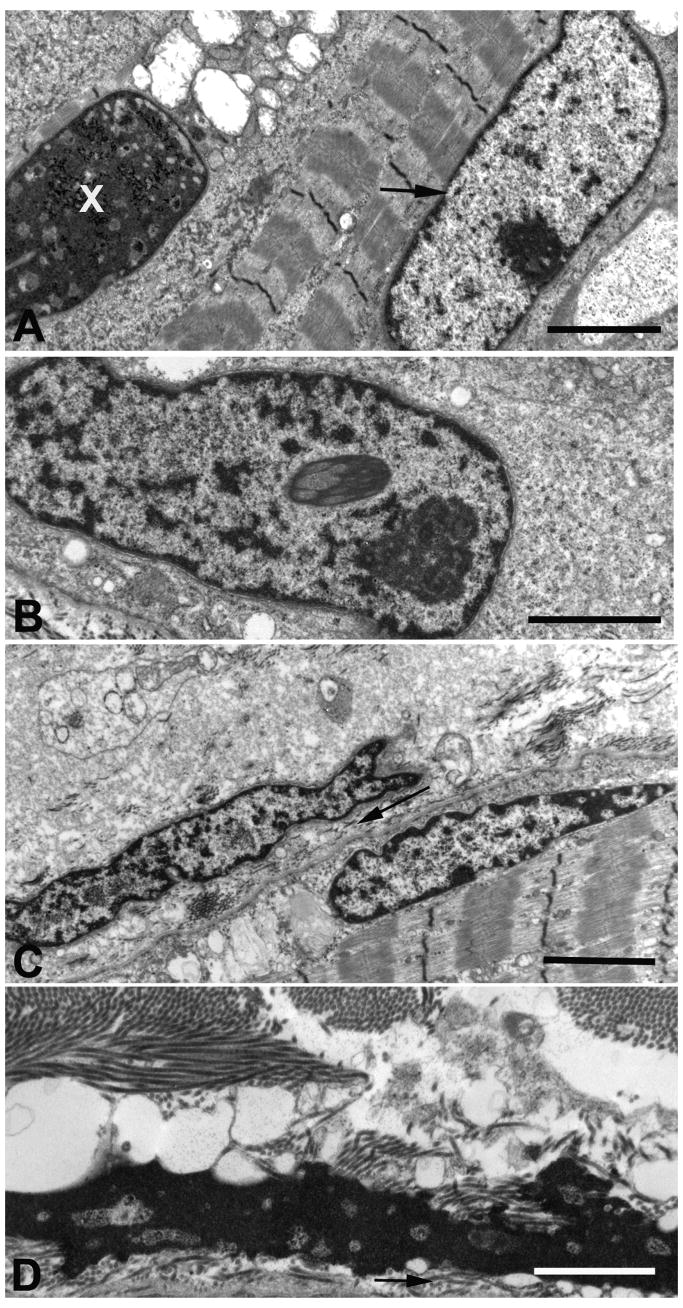

To confirm the presence and more accurately define the frequency of apoptotic nuclei, and of other nuclear alterations, we classified the features of 293 consecutively observed nuclei in the electron microscope: 8% were apoptotic, filled with homogeneous condensed chromatin (Figs. 3D and E, and Fig. 4A and D); 28% were elongated with dispersed chromatin and prominent nucleoli suggesting active transcription23 common to other MFM patients (Fig. 4A); 15% were unusually large and harbored large clumps of heterochromatin (Fig. 4B), 4% were pyknotic (Fig. 4C), and 45% appeared normal. Some pyknotic (Fig. 4C) and apoptotic (Fig. 4D) nuclei were extruded into the extracellular space.

Fig. 4.

Nuclear alterations in Patient 1. (A) Ovoid nucleus with prominent nucleolus suggesting increased transcription (arrow) and apoptotic nucleus (X). (B) Large nucleus harboring clumps of heterochromatin. (C) A superficially positioned shrunken (pyknotic) nucleus in a muscle fiber is positioned under an exocytosed pyknotic nucleus. Arrow points to collagen fibrils in the extracellular space. (D) An exocytosed apoptotic nucleus. Arrow points to collagen in the extracellular space. Bars = 2 μm in (A) and (C) and 1 μm in (B) and (D).

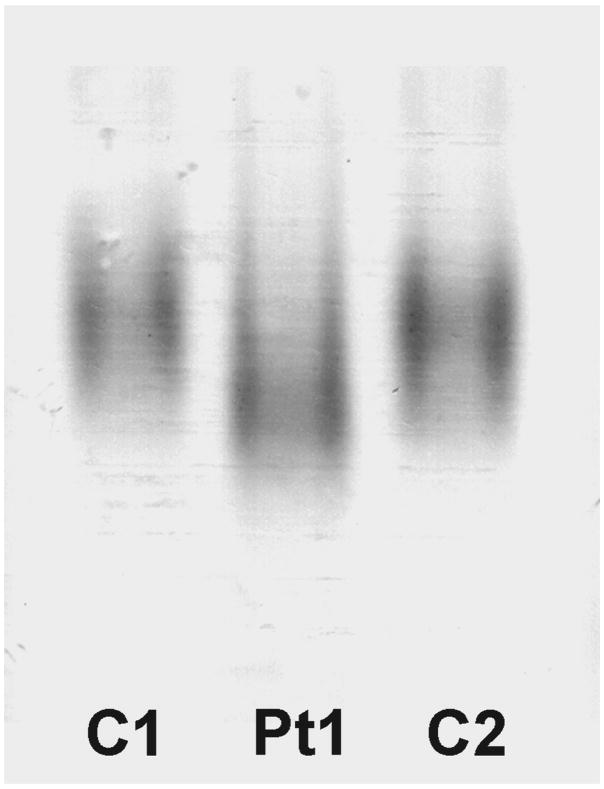

Immunoblot Analysis

To compare Bag3 in patient and control muscles in the native state, we electrophoresed muscle extracts under non-denaturing conditions and probed the immunoblots with an anti-Bag3 antibody. This revealed a wide and faster migrating Bag3-reactive band in the patient than control muscle extract (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Bag3 immunoblot of native muscle extract of Patient 1 and two normal controls electrophoresed under nondenaturing conditions. Patient displays a faster migrating Bag3 band than controls.

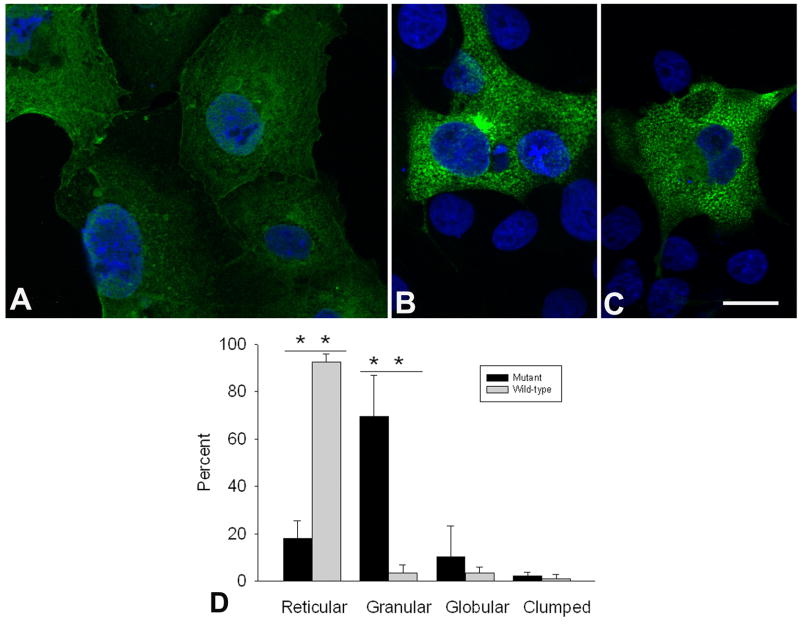

Expression Studies In Cos-7 Cells

Because in a previous study mutant αB-crystallin, another protein with chaperone function for Z-disk related proteins, transfected into COS-7 cells formed coarse granular aggregates,24 we transfected mutant and wild-type Bag3 into COS-7 cells. Wild-type Bag3 appeared predominantly as a delicate filamentous network in most cells (Fig. 6A); in fewer cells, Bag3 appeared in granular, globular, or clumped granular profiles (Fig. 6D). By contrast, mutant Bag3 appeared predominantly in the form of small discrete granules (Fig. 6B and C), with a lesser number of cells harboring other types of profiles (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

(A-C): COS-7 cells transfected with FLAG-labeled wild-type (A) and mutant BAG3 (B and C). The nuclei are stained with DAPI. Wild-type Bag3 localizes to a reticular network of fine filaments; mutant Bag3 localizes predominantly to fine discrete granules. Apotome optics, 0.43 μm slice distance. Bar = 20μm for each panel. (D) Frequencies of COS-7 cells harboring reticular, granular, globular and clumped Bag3-positive profiles. Transfection with the mutant construct results in many more cells harboring granular profiles (P < 0.001), and fewer cells with reticular profiles (P < 0.001), than transfection with the wild type construct. Four-hundred and forty-five cells expressing wild-type Bag3 and 470 cells expressing mutant Bag3, were analyzed. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations.

Discussion

We considered Bag3 a candidate protein for MFM because it localizes to and co-chaperones the Z disk in skeletal and cardiac muscle, and because its targeted deletion in mice causes fulminant myopathy with early mortality. The 3 patients carrying the mutant BAG3 had relentlessly progressive childhood onset muscle weakness culminating in respiratory failure in the second decade, an associated cardiomyopathy, and elevation of the serum CK level. Patients 2 and 3 also had a rigid spine, and Patient 2 had EMG evidence of a peripheral neuropathy. Bag3 is highly expressed in heart as well as in skeletal muscle but no data are available on Bag3 expression in peripheral nerve. The neuropathy in Patient 2 suggests that Bag3 is expressed, even if at a low level, in anterior horn cells, axons or Schwann cells. If Bag3 expression were only axonal, demyelination could be secondary to axonal degeneration.

The light microscopy findings in the 3 patients and the electron microscopy findings in Patient 1 were typical of MFM.3,8,9 Phenotypes of the 3 patients differ from those of other patients in the Mayo MFM cohort in their age of onset, rapid evolution of the illness, and presence of the rigid spine in Patients 2 and 3. In 82 other MFM patients in the Mayo MFM cohort, only 1 presented before the age of 10, the disease typically progressed slowly, mostly over decades, and none had a rigid spine. In the 50 patients investigated in this study who had no Bag3 mutations, the mean, median and range of age of onset was 54.6, 62, and 7–77 years, respectively.

The rigid spine in Patients 2 and 3 was of special interest. It is invariably present in patients with selenoprotein N1 mutations with morphologic features of Mallory body-like inclusions, multiminicore disease, or congenital fiber type disproportion,25 and is common in mutations in FHL1 associated with intracytoplasmic myofiber inclusions that reduce nitro-blue-tetrazolium (NBT) and thus stain strongly with the Menadione-NBT stain.26 Rigidity of the spine can also be observed in myopathies due to mutations in collagen 627, laminA/C,28 emerin,29 and less frequently in other conditions, as in dysferlinopathy.30 Therefore, a rigid spine is not a marker for MFM, but in patients with MFM pathology it can point to a mutation in BAG3; and association of Bag3opathy with a rigid spine widens the clinical spectrum of the rigid spine syndrome.

That parents of each patient were asymptomatic and that tested parents of 2 patients were not carriers of the Bag3 mutation was also of interest. This is likely explained by the early onset and severity of the disease which restricts the reproductive capacity of affected patients.

Nuclear apoptosis had been reported to be absent in MFM patients,31 but in αB-crystallinopathy 8% of the nuclei have pre-apoptotic features12 and in Bag3opathy 8% of the nuclei are frankly apoptotic; moreover, some apoptotic nuclei in Bag3opathy are extruded from the fibers by exocytosis (Fig. 4D). This is an unusual finding we did not observe in other MFM patients. The enhanced nuclear apoptosis in Bag3opathy is consistent with known antiapoptotic effect of Bag317,32,33 and indicates that Pro209 contributes to this effect. In a multinucleated muscle fiber apoptosis of a proportion of the nuclei may not be lethal for the fiber. However, mature muscle fiber nuclei are invariably postmitotic and so continued apoptosis could eventually deplete the complement of nuclei. That 28% of the nuclei show signs of active transcription is consistent with enhanced and ectopic expression of multiple proteins in MFM, and is not specific for Bag3opathy. The cause and significance of the unusually large nuclei harboring large clumps of heterochromatin is presently unclear.

In nondenaturing electrophoresis of patient and control muscle extracts, the Bag3 complex, which is predicted to comprise Bag3 and proteins associating with it, migrates faster for the patient than controls (Fig. 5). The faster migration of the mutant complex could be due to a change in the size or charge. Because a Pro to Leu mutation results in no change in charge, the faster mobility of the mutant complex likely owes to its smaller size. A plausible reason for this is failure of some of the binding partners of Bag3 proteins to associate with the complex. Further studies will be required to examine the molecular composition of the complex in the native state.

Transfection of COS-7 with FLAG-labeled mutant and wild-type Bag-3 revealed a marked tendency of the mutant protein to aggregate into small granules. A likely reason for this is altered folding, and predictably altered function, of the mutant protein.

Although the mutated proline residue at codon 209 does not fall within a previously characterized canonical domains of the protein, the high pathogenicity of the mutation in humans reveals yet another important region of Bag3. Replacement of a proline residue can be especially deleterious because the conformationally restricted rigid imino ring of proline confers structural stability on the polypeptide segment in which it occurs.34 Thus p.Pro209Leu may alter the folding of Bag3; alternatively or additionally, it may allosterically affect the binding properties of the canonical Bag3 domains. Regardless of the exact mechanism by which the Pro209Leu mutation affects the molecular properties of the wild type protein, our findings define a new form of childhood muscular dystrophy and cardiomyopathy, and also the first human disease caused by a spontaneous mutation in the Bag family of proteins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a K08 Grant from NIH Grant NS6277 to DS.

Footnotes

None of the authors have any financial interest pertaining to this work.

References

- 1.Goldfarb LG, Park KY, Cervenákova L, et al. Missense mutations in desmin associated with familial cardiac and skeletal myopathy. Nat Genet. 1998;19:402–403. doi: 10.1038/1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vicart P, Caron A, Guicheney P, et al. A missense mutation in the αB-crystallin chaperone gene causes a desmin-related myopathy. Nat Genet. 1998;20:92–95. doi: 10.1038/1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selcen D, Ohno K, Engel AG. Myofibrillar myopathy. Clinical, morphological, and genetic studies in 63 patients. Brain. 2004;127:439–451. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selcen D, Engel AG. Mutations in myotilin cause myofibrillar myopathy. Neurology. 2004;62:1363–1371. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000123576.74801.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olive M, Goldfarb LG, Shatunov A, et al. Myotilinopathy: refining the clinical and myopathological phenotype. Brain. 2005;128:2315–2326. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selcen D, Engel AG. Mutations in ZASP define a novel form of muscular dystrophy in humans. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:269–276. doi: 10.1002/ana.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vorgerd M, van der Ven PFM, Bruchertseifer V, et al. A mutation in the dimerization domain of filamin C causes a novel type of autosomal dominant myofibrillar myopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:297–304. doi: 10.1086/431959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakano S, Engel AG, Waclawik AJ, et al. Myofibrillar myopathy with abnormal foci of desmin positivity. I. Light and electron microscopy analysis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:549–562. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199605000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Bleecker JL, Engel AG, Ertl BB. Myofibrillar myopathy with abnormal foci of desmin positivity. II. Immunocytochemical analysis reveals accumulation of multiple other proteins. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:563–577. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199605000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munoz-Mármol AM, Strasser G, Isamat M, et al. A dysfunctional desmin mutation in a patient with severe generalized myopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11312–11317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalakas MC, Park KY, Semino-Mora C, et al. Desmin myopathy, a skeletal myopathy with cardiomyopathy caused by mutations in the desmin gene. New Engl J Med. 2000;342:770–780. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003163421104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Selcen D, Engel AG. Myofibrillar myopathy caused by novel dominant negative αB-crystallin mutations. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:804–810. doi: 10.1002/ana.10767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griggs RC, Vihola A, Hackman P, et al. Zaspopathy in a large classic late-onset distal myopathy family. Brain. 2007;130:1477–1484. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroder R, Vrabie A, Goebel HH. Primary desminopathies. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:416–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Homma S, Iwasaki M, Shelton GD, et al. BAG3 deficiency results in fulminant myopathy and early lethality. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:761–773. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takayama S, Reed JC. Molecular chaperone targeting and regulation by BAG family proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:E237–E241. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-e237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doong H, Vrailas A, Kohn EC. What's in the 'BAG'? - a functional domain analysis of the BAG-family proteins. Canc Lett. 2002;188:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carra S, Seguin SJ, Lambert H, et al. HspB8 chaperone activity toward poly(Q)-containing proteins depends on its association with Bag3, a stimulator of macroautophagy. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1437–1444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engel AG. The muscle biopsy. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, editors. Myology. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 681–690. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldfarb LG, Vicart P, Goebel HH, et al. Desmin myopathy. Brain. 2004;127:723–734. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruey JM, Ducasse C, Bonniaud P, et al. Hsp27 negatively regulates cell death by interacting with cytochrome c. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:645–652. doi: 10.1038/35023595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antoku K, Maser RS, Scully WJ, et al. Isolation of Bcl-2 binding proteins that exhibit homology with BAG-1 and suppressor of death domains protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:1003–1010. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson MOJ, Dundr M, Szebeni A. The nucleolus: an old factory with unexpected capabilities. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01738-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon S, Fontaine JM, Martin JL, et al. Myopathy-associated αB-crystallin mutants: abnormal phosphorylation, intracellular location, and interactions with other small heatshock proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34276–34287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schara U, Kress W, Bönnemann CG, et al. The phenotype and long-term follow-up in 11 patients with juvenile selenoprotein N1-related myopathy. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2008;12:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schessl J, Zou Y, McGrath MJ, et al. Proteomic identification of FHL1 as the protein mutated in human reducing body myopathy 2. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:904–912. doi: 10.1172/JCI34450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Visser M, van der Kooi AJ, Jöbsis GJ. Bethlem myopathy. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, editors. Myology. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 1135–1146. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercuri E, Poppe M, Quinlivan R, et al. Extreme variability of phenotype in patients with an identical missense mutation in the Lamin A/C gene: From congenital onset with severe phenotype to milder classic Emery-Dreifuss variant. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:690–694. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maraldi NM, Merlini L. Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. In: Engel AG, Franzini-Armstrong C, editors. Myology. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 1027–1037. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagashima T, Chuma T, Mano Y, et al. Dysferlinopathy associated with rigid spine syndrome. Neuropathology. 2004;24:341–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2004.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amato AA, Jackson CE, Lampkin S, et al. Myofibrillar myopathy: No evidence of apoptosis by TUNEL. Neurology. 1999;52:861–863. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.4.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao Q, Ozawa F, Friess H, et al. The anti-apoptotic protein BAG-3 is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer and induced by heat stress in pancreatic cancer cell lines. FEBS Lett. 2003;503:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonelli P, Petrella A, Rosati A, et al. BAG3 protein regulates stress-induced apoptosis in normal and neoplastic leukocytes. Leukemia. 2004;18:358–360. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peralvarez-Marin A, Lorenz-Fonfria VA, Simon-Vazquez R, et al. Influence of proline on the thermostability of the active site and membrane arrangement of transmembrane proteins. Biophys J. 2008 doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136747. Epub 7/25/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]