Abstract

Background

The Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE) is widely used in Japan and the U.S.A. for cognitive screening in the clinical setting and in epidemiological studies. A previous Japanese community study reported distributions of the MMSE total score very similar to that of the U.S.A.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Monongahela Valley Independent Elder's Study (MoVIES), a representative sample of community-dwelling elderly people aged 65 and older living near Pittsburgh, U.S.A., and from the Tajiri Project, with similar aims in Tajiri, Japan. We examined item-by-item distributions of the MMSE between two cohorts, comparing (1) percentage of correct answers for each item within each cohort, and (2) relative difficulty of each item measured by Item Characteristic Curve analysis (ICC), which estimates log odds of obtaining a correct answer adjusted for the remaining MMSE items, demographic variables (age, gender, education) and interactions of demographic variables and cohort.

Results

Median MMSE scores were very similar between the two samples within the same education groups. However, the relative difficulty of each item differed substantially between the two cohorts. Specifically, recall and auditory comprehension were easier for the Tajiri group, but reading comprehension and sentence construction were easier for the MoVIES group.

Conclusions

Our results reaffirm the importance of validation and examination of thresholds in each cohort to be studied when a common instrument is used as a dementia screening tool or for defining cognitive impairment.

Keywords: MMSE, cross-cultural comparison, community-based study

Introduction

When different populations are examined using a common instrument, whether for clinical or research purposes, the assumption is often made that performance on that test is distributed similarly and that the same screening thresholds are equally valid in all settings. This assumption becomes riskier with increasing diversity between or within populations.

The Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975), a well-known brief screening scale for global cognition or general mental status, is widely used in Japan in both clinical and research settings, including epidemiological studies. The town of Tajiri in northern Japan was the location of the first community-based study of the MMSE in older Japanese adults, reported a decade ago (Ishizaki et al., 1998). That study reported that despite the differences in language and culture, median MMSE scores were remarkably similar between Japan and other countries. In the current study, we examined the issue in greater detail, comparing the item-by-item responses in MMSE between two cohorts: one from the Monongahela Valley Independent Elder's Study (MoVIES; Ganguli et al., 2000), a representative sample of community-dwelling elderly aged 65 and older living near Pittsburgh, U.S.A., and another from the Tajiri Project (Ishizaki et al., 1998), which aimed to interview all the residents aged 65 and older living in Tajiri. Baseline assessments were conducted in 1987 for the MoVIES cohort, and in 1991 for the Tajiri cohort. The main aims of the current analyses were to determine the item-by-item distributions of MMSE and whether relative difficulty to complete each item was similar between the two cohorts.

Methods

Data

DATA FOR THE U.S.A

The MoVIES Project (Ganguli et al., 1993; 2000) was a prospective epidemiological study of dementia beginning in 1987. Located in a largely rural area of southwestern Pennsylvania, formerly home to the steel industry, the population is largely blue-collar and of mostly European descent. The MoVIES cohort comprised an age-stratified random sample of 1422 persons, and 259 volunteers from the same area, giving a total sample size of 1681. Entry criteria were community residence at baseline, age 65 or older, fluency in English, and education at least through grade 6 to permit the interpretability of the neuropsychological tests. Here, we used only the random sample of 1422 at baseline. From those, 1383 subjects (97.3%) with complete MMSE data were used for the current study. Study approval was received from the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Pittsburgh and Oregon State University for the specific study reported here.

DATA FOR JAPAN

The Tajiri Project was conducted by Tohoku University and the Tajiri Project for Stroke, Dementia, and Bedridden Prevention organized by Tajiri town government. The baseline study was conducted from May to August 1991 in the town of Tajiri, located in a typical agricultural area in the northern part of Japan. Of the 2516 elderly aged 65 and older residing in the town in 1991 and contacted by this study, 2266 respondents (90%) completed the interview (Ishizaki et al., 1998). Since the MoVIES sample excluded those with less than 6th grade education, we excluded the corresponding group (i.e. less than elementary school education) from the Tajiri cohort for the current analyses. This resulted in 1966 subjects in the Tajiri cohort (86.7% of the original sample). We obtained permission from the Tajiri government, which owns the dataset, to analyze the data on MMSE total score, sub-item scores, age, sex, and education levels of the baseline participants. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Tohoku University, University of Pittsburgh and Oregon State University.

Statistical methods

The distribution of MMSE total scores was compared between the two groups, and separately for each education group. The Tajiri Project participants went through the old Japanese educational system where elementary school consists of 6 years, followed by the upper elementary school (total of 8 years of education), middle school (total of 10 years of education), high school (total of 14 years of education), and college (total of 16 years of education) upon graduation. For current analyses, education was categorized as less than 10 years versus 10 and more years in both cohorts.

Second, the proportions of those with the maximum score for each sub-item in MMSE between the two cohorts were examined using Pearson χ2 statistics. The sub-items examined are:

Orientation to time (year, season, month, day, date)

Orientation to place (prefecture, town, name of building, floor, region in Tajiri; state, county, city/town, floor, name of the place in MoVIES)

Registration: repeat three words

Attention: serial subtraction of 7 from 100, five consecutive responses

Recall: recall the three words registered in Item 3

Naming: name two objects

Repetition: repeat a phrase

Auditory comprehension/command: follow a three-stage oral command

Reading comprehension: read and obey a written command

Sentence construction: write a sentence

Constructional praxis: copy a figure (intersecting pentagons).

Third, we compared the difficulty of items for two groups using Item Characteristics Curve analysis (ICC; Hambleton et al., 1991). We used logistic regression models where the log of odds of success (getting a correct answer) was estimated as a function of ability (indicated by the modified sum of MMSE item scores described later), age, sex and education (less than 10 years of education vs. 10 and more years of education), and interactions of the latter three variables and cohort (MoVIES vs. Tajiri). The following items in MMSE have continuous scales: Registration (range: 0-3), attention (0-7), recall (0-3), naming (0-3), and auditory comprehension (0-3). Individual item scores for orientation time (year, season, month, day, date) and place (prefecture, town, name of building, floor, region) were not entered into the Tajiri database; thus, total scores (ranges from 0 to 5) are available for the orientation items. For continuous outcomes, ordinal logistic regression is commonly used in the differential item functioning study (Crane et al., 2004). However, preliminary analysis showed that ordinal logistic regression models for our data do not satisfy the proportional odds assumption for any outcomes examined here. Therefore, for the current analyses, we dichotomized the continuous scores at the medians, as follows: orientation to time (4/5), orientation to place (4/5), registration (2/3), attention (3/4), recall (2/3), naming (1/2), and auditory comprehension (2/3). The correct answer receives one point for each item. For example, a score of 4 or more on the attention subtest (serial subtraction) was treated as correct on this item and was rescored as1. We have 11 items, which made the maximum MMSE ability score (relative difficulty levels) used for ICC range from 0 to 10.

We estimated the following model:

| (1). |

Based on the above model, we estimated the ability for each cohort when the probability of getting a correct answer is 50% - i.e. the difficulty level of an item at which half the group answers the item correctly.

Results

Median scores were very similar between the two samples in each education group (Table 1). However, the distribution differed for younger age groups (65-69 and 70-74) with 10 years or more of education. In this sample, the majority of the Tajiri cohort had an education of less than 10 years (86.2%), while the majority of the MoVIES cohort had an education of 10 or more years (71.7%).

Table 1.

MMSE scores by age and education groups: MoVIES (1989-1991) and Tajiri (1991) studies.

| AGE GROUP |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEARS OF EDUCATION | 65-69 | 70-74 | 75-79 | 80-84 | 85 + |

| > 6 yrs and < 10 yrs [% among each cohort] | |||||

| Tajiri N = 1624 | |||||

| [82.6%] | N = 524 | N = 454 | N = 315 | N = 225 | N = 106 |

| Median | 28 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 23 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.70 (1.93) | 25.80 (3.90) | 25.59 (4.05) | 23.42 (5.22) | 21.84 (6.54) |

| Range | 6-30 | 8-30 | 8-30 | 4-30 | 1-30 |

| MoVIES, N = 392 | |||||

| [28.3%] | N = 66 | N = 109 | N = 117 | N = 71 | N = 29 |

| Median | 27 | 26 | 26 | 24 | 23 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.60 (1.93) | 25.63 (3.02) | 25.04 (3.38) | 23.45 (4.23) | 22.20 (5.10) |

| Range | 20-30 | 12-30 | 11-30 | 11-30 | 3-30 |

| P-value* | NS | NS | 0.02a | NS | NS |

| 10 yrs or more | |||||

| Tajiri N = 342 | |||||

| [17.4%] | N = 123 | N = 98 | N = 68 | N = 39 | N = 14 |

| Median | 29 | 29 | 28 | 26 | 25 |

| Mean (SD) | 28.30 (2.03) | 27.63 (3.20) | 27.02 (3.99) | 25.20 (4.67) | 22.71 (7.03) |

| Range | 18-30 | 9-30 | 1-30 | 9-30 | 11-30 |

| MoVIES N = 991 | |||||

| [71.7%] | N = 383 | N = 335 | N = 185 | N = 55 | N = 33 |

| Median | 28 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 26 |

| Mean (SD) | 27.62 (2.18) | 27.16 (2.50) | 26.33 (3.50) | 26.63 (2.54) | 24.42 (4.25) |

| Range | 5-30 | 9-30 | 3-30 | 20-30 | 9-29 |

| P-value* | <0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.03a | NS | NS |

Mann-Whitney nonparametric test.

Not significant at p = 0.005, Bonferroni p value correcting for the number of comparisons in the above analysis. NS Not significant.

In each cohort, we examined the percentage of those with maximum or perfect scores on each sub-scale of the MMSE (Tables 2 and 3). Significantly higher proportions of individuals in the Tajiri cohort attained the maximum score on the following items: delayed recall across all age groups in both education groups; auditory comprehension/command item across all age groups in the lower education group and also in all age groups except the oldest age group in the higher education group. On the other hand, significantly higher proportions of individuals in the MoVIES cohort had maximum scores for the following items: sentence construction item across all age groups in both education groups, reading comprehension among all age groups in the lower education group, and among those younger than age 75 in the higher education group.

Table 2.

Proportion of those with perfect scores in each sub-item in MMSE: 6 ≤ years of education < 10

| AGE GROUP |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65-69 |

70-74 |

75-79 |

80-84 |

85 + |

|||||||

| SUBITEMS | TAJIRI (N) | 524 | 454 | 315 | 225 | 106 | |||||

| (MAXIMUM SCORE) | MOVIES (N) | 66 | 109 | 117 | 71 | 29 | |||||

| p-value | p-value | p-value | p-value | p-value | |||||||

| 1. Orientation Time (5) | Tajiri | 91.6 | 85.9 | 81.0 | 61.8 | 58.5 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 75.8 | <0.001* | 72.5 | <0.001 | 82.1 | NS | 67.6 | NS | 55.2 | NS | |

| 2. Orientation Place (5) | Tajiri | 89.7 | 86.8 | 78.1 | 66.2 | 60.4 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 97.0 | NS | 99.1 | <0.001* | 94.9 | <0.001* | 87.3 | <0.001* | 82.8 | 0.025 | |

| 3. Registration (3) | Tajiri | 96.4 | 92.3 | 91.4 | 84.4 | 84.0 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 98.5 | NS | 95.4 | NS | 94.9 | NS | 87.3 | NS | 79.3 | NS | |

| 4. Attention (5) | Tajiri | 50.2 | 39.9 | 42.9 | 29.8 | 25.5 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 30.3 | 0.002 | 30.3 | NS | 31.6 | 0.034 | 25.4 | NS | 27.6 | NS | |

| 5. Recall (3) | Tajiri | 91.2 | 83.5 | 83.2 | 76.4 | 67.0 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 31.8 | <0.001* | 24.8 | <0.001* | 23.9 | <0.001* | 14.1 | <0.001* | <0.001 | <0.001* | |

| 6. Naming (3) | Tajiri | 95.6 | 96.5 | 94.3 | 94.7 | 94.3 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 100.0 | NS | 99.1 | NS | 100.0 | 0.008 | 100.0 | 0.047 | 96.6 | NS | |

| 7. Repetition (1) | Tajiri | 83.4 | 78.9 | 75.2 | 64.4 | 60.4 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 62.1 | <0.001* | 69.7 | 0.042 | 51.3 | <0.001* | 47.9 | 0.013 | 51.7 | NS | |

| 8. Auditory | Tajiri | 95.8 | 95.8 | 95.89 | 92.9 | 90.6 | |||||

| Comprehension (3) | Mo VIES | 72.7 | <0.001* | 67.0 | <0.001 | 63.3 | <0.001* | 52.1 | <0.001* | 48.3 | <0.001 |

| 9. Reading | Tajiri | 84.9 | 82.2 | 82.9 | 73.3 | 68.9 | |||||

| Comprehension (1) | Mo VIES | 98.5 | 0.002 | 99.1 | <0.001* | 92.3 | 0.013 | 90.1 | 0.003 | 89.7 | 0.025 |

| 10. Sentence | Tajiri | 65.7 | 63.4 | 64.1 | 42.2 | 37.7 | |||||

| Construction (1) | Mo VIES | 100.0 | <0.001* | 94.5 | <0.001 | 96.6 | <0.001* | 93.0 | <0.001* | 82.8 | <0.001 |

| 11. Constructional | Tajiri | 85.5 | 81.7 | 71.4 | 59.1 | 45.3 | |||||

| Praxis (1) | Mo VIES | 81.8 | NS | 78.9 | NS | 70.9 | NS | 57.8 | NS | 44.8 | NS |

Significant at p value of 0.0009, Bonferroni p value correcting for the number of comparisons in the above analysis.

Table 3.

Proportion of those with perfect scores in each sub-item in MMSE: years of education ≥ 10

| AGE GROUP |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65-69 |

70-74 |

75-79 |

80-84 |

85 + |

|||||||

| SUBITEMS | TAJIRI (N) | 123 | 98 | 68 | 39 | 14 | |||||

| (maximum Score) | MOVIES (N) | 383 | 335 | 185 | 55 | 33 | |||||

| p-value | p-value | p-value | p-value | p-value | |||||||

| 1. Orientation Time (5) | Tajiri | 95.1 | 85.7 | 89.7 | 74.4 | 57.1 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 83.6 | <0.001 | 77.6 | NS | 75.1 | 0.012 | 74.6 | NS | 66.7 | NS | |

| 2. Orientation Place (5) | Tajiri | 98.4 | 92.9 | 92.7 | 87.2 | 64.3 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 98.2 | NS | 96.4 | NS | 95.7 | NS | 98.2 | 0.032 | 84.9 | NS | |

| 3. Registration (3) | Tajiri | 98.4 | 99.0 | 97.1 | 94.9 | 85.7 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 98.2 | NS | 98.5 | NS | 96.8 | NS | 100.0 | NS | 81.8 | NS | |

| 4. Attention (5) | Tajiri | 72.4 | 61.2 | 54.4 | 35.9 | 42.9 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 53.0 | <0.001* | 47.2 | 0.014 | 43.8 | NS | 56.4 | NS | 36.4 | NS | |

| 5. Recall (3) | Tajiri | 94.3 | 90.8 | 91.2 | 84.6 | 57.1 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 51.7 | <0.001* | 40.9 | <0.001 | 32.4 | <0.001* | 29.1 | <0.001* | 21.2 | 0.016 | |

| 6. Naming (3) | Tajiri | 96.8 | 95.9 | 97.1 | 94.9 | 92.9 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 99.2 | 0.04 | 100.0 | <0.001 | 99.5 | NS | 100.0 | NS | 97.0 | NS | |

| 7. Repetition (1) | Tajiri | 95.9 | 88.8 | 85.3 | 84.6 | 57.1 | |||||

| Mo VIES | 81.7 | <0.001* | 77.0 | 0.011 | 68.7 | 0.008 | 74.6 | NS | 51.5 | NS | |

| 8. Auditory | Tajiri | 95.1 | 95.9 | 98.5 | 92.3 | 78.6 | |||||

| Comprehension (3) | Mo VIES | 75.2 | <0.001* | 76.1 | <0.001* | 62.7 | <0.001* | 65.5 | 0.002 | 57.6 | NS |

| 9. Reading | Tajiri | 90.2 | 89.8 | 92.7 | 87.2 | 78.6 | |||||

| Comprehension (1) | Mo VIES | 98.4 | <0.001* | 99.4 | <0.001 | 95.7 | NS | 92.7 | NS | 93.9 | NS |

| 10. Sentence | Tajiri | 76.4 | 76.5 | 73.5 | 74.4 | 50.0 | |||||

| Construction (1) | Mo VIES | 99.2 | <0.001* | 97.9 | <0.001* | 96.2 | <0.001* | 96.4 | 0.002 | 97.0 | <0.001* |

| 11. Constructional | Tajiri | 91.9 | 91.8 | 86.8 | 79.5 | 57.1 | |||||

| Praxis (1) | Mo VIES | 90.3 | NS | 86.6 | NS | 82.7 | NS | 80 | NS | 66.7 | NS |

Significant at p-value of 0.0009, Bonferroni p value correcting for the number of comparisons in the above analysis.

Table 4 shows the relative difficulty score for each item, using the ICC analyses. The score indicates ability level at which the probability of a correct response was 0.5, using the cut-offs described above (indicated also in parenthesis in Table 4). P-values in Table 4 correspond to those of β2 in Equation 1 above (group effect adjusted for confounders). Supporting our descriptive findings above, we found large differences for recall, auditory comprehension, sentence construction and reading comprehension. For the Tajiri cohort, recall and auditory comprehension were relatively easy (i.e. required a lower ability score) while for the MoVIES cohort, reading comprehension and sentence construction were relatively easy. Only three items - registration, naming, and constructional praxis - showed no significant differences in relative ability scores between two groups.

Table 4.

Relative difficulty* of each sub-item of Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE) (maximum score = 10)

| MOVIES N =1383 (1) | TAJIRI N =1966 (2) | DIFFERENCE IN REQUIRED ABILITY SCORE (1)-(2) | DIFFERENCE IN TWO GROUPS P-VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Orientation Time (obtaining score of 5) | 4.50 | 3.15 | 1.35 | <0.001 |

| 2. Orientation Place (obtaining score of 5) | 0.78 | 3.88 | -3.10 | <0.001 |

| 3. Registration (obtaining score of 3) | 0.82 | 2.05 | -1.03 | NS |

| 4. Attention (Serial Sevens) (obtaining score ≥ 4) | 7.21 | 8.29 | -1.23 | <0.001 |

| 5. Recall (obtaining score of 3) | 10a | 3.57 | 6.43 | <0.001 |

| 6. Naming (obtaining score of 3) | 0a | 0a | 0 | NS |

| 7. Repetition (obtaining score of 1) | 6.31 | 4.64 | 1.67 | <0.001 |

| 8. Auditory Comprehension (obtaining score of 1) | 0 | 4.03 | -4.03 | <0.001 |

| 9. Reading Comprehension (obtaining score of 3) | 6.16 | 0.51 | 5.65 | <0.001 |

| 10. Sentence Construction (obtaining score of 1) | 0a | 6.83 | -6.83 | <0.001 |

| 11. Constructional Praxis (obtaining score of 1) | 4.32 | 4.20 | 0.12 | NS |

Difficulty is measured by estimating the ability level at which 50% of the participants could correctly answer an item in each cohort. Higher score means that item is more difficult.

Ability scores range from 0 to 10. The estimated score beyond the range was truncated. NS Not significant.

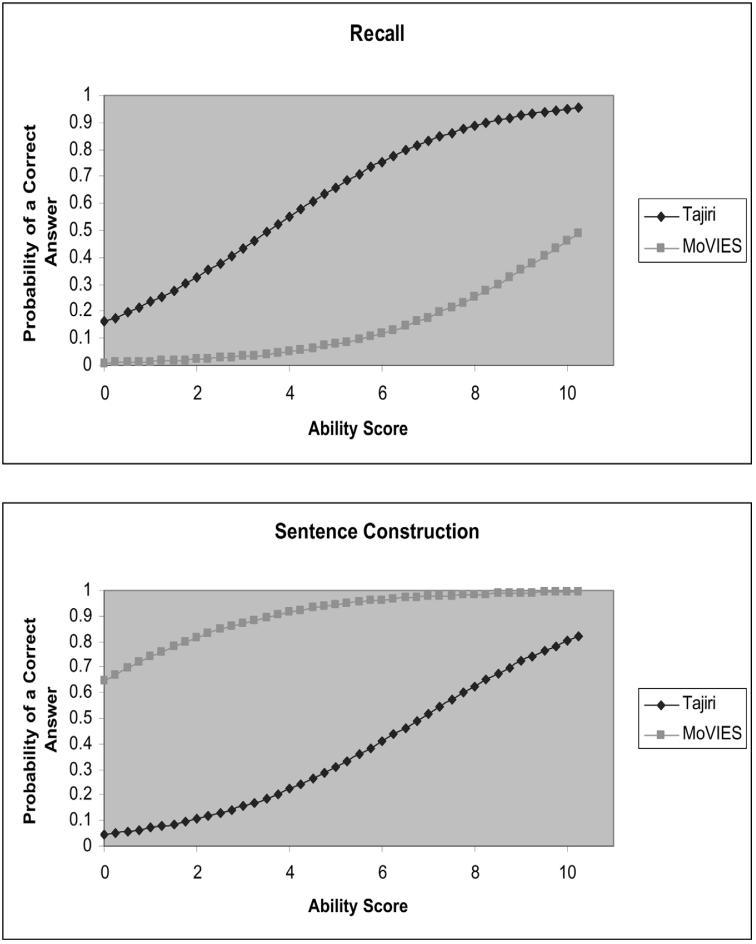

Figure 1 shows the probability of a correct answer for each ability score for recall and sentence construction. In Tajiri, almost everyone who was correct on all other items also obtained a full score on recall (i.e. probability of a correct answer on recall reaches 1 for those with ability scores of 10). However, in MoVIES, only half of those who were correct on all other items had correct answers on the recall item (i.e. probability of a correct answer in recall was about 0.5 for those with ability score of 10). The opposite was true for sentence construction; even those with a very low ability score could get a correct answer in this item among the MoVIES cohort, but in Tajiri, the probability of a correct answer in sentence construction was about 80%, even for those who were correct in all other items.

Figure 1.

Probability of a correct answer in recall (obtaining score of 3) and in sentence construction (obtaining score of 1) by ability scores for two cohorts.

Discussion

The distribution of item scores on the MMSE were very different in our Japanese and American cohorts, although median scores were very similar as previously reported (Ishizaki et al., 1998). Japanese elderly participants in the Tajiri cohort performed better on the verbal memory (“delayed recall”) despite the fact that the proportion of individuals with maximum scores on “registration” was similar between the two cohorts (i.e. participants in both cohorts encoded/registered the three words to a similar extent). Japanese elderly participants also performed better on the verbal comprehension item shown in “auditory comprehension/command”, which requires retention of a three-step command. American elderly in the Monongahela Valley cohort had superior performance in processing written (or visually presented) information shown in “reading comprehension”, and were more likely to write a sentence successfully.

The poorer performance in “sentence construction” and “reading comprehension” among the Tajiri cohort could be partly explained by the linguistic features specific to Japanese and the related scoring method; the basic Japanese word order is subject-object-verb and these components are connected by postpositions which are suffixed to the words that they modify. For example, “I like apples” can be said in Japanese “Watashi-waringo-ga-sukidesu”. Here, “Watashi” is “I”, ringo is “apple”, sukidesu is “like”. However, unlike in English, two prepositions (“wa” and “ga” here) are necessary in Japanese to complete the sentence. Additionally Japanese characters consist of three types of letters: Kanji (Chinese characters with each character representing a certain meaning), Hiragana (indicates only phonetic sounds) and Katakana (indicates phonetic sounds for imported or foreign words). In the Tajiri study, using an incorrect Kanji character or making a mistake in Kanji figures, or missing prepositions were counted as errors and only one error was allowed to score for “sentence construction.” In contrast, the MoVIES study followed the American scoring convention: as long as a subject and verb were present in a sentence, this test item was scored as correct and spelling mistakes were disregarded. Since the Japanese language has more components to be considered for scoring (prepositions, characters), “sentence construction” might have been a harder task for the Tajiri subjects, compared with the participants in the MoVIES study. In fact, in a different study, Tajiri researchers (Akanuma et al., 2004) found that those with very mild Alzheimer's disease were more likely to miss/forget prepositions when they were asked to write a sentence, compared with the group without dementia. They speculated that this could reflect declining attention associated with dementia pathology (Platel et al., 1993; Neils et al., 1995; Croisile et al., 1996). In other words, writing a complete Japanese sentence could be more sensitive to cognitive decline than writing an English sentence. The use of Kanji characters would have also adversely affected the ability to read and follow the command as shown by poorer scores among the Tajiri group in “reading comprehension.” Future studies requiring MMSE equivalence between the U.S.A. and Japan should consider allowing more errors in “sentence construction” among Japanese participants (e.g. errors in Chinese characters and missing prepositions), and using only Hiragana (non-Chinese characters) for “reading command.”

The better performance in recall among the Tariji participants was somewhat unexpected; the Tajiri cohort had over 90% participation among the residents in Tajiri town who were age eligible, while in MoVIES, the participation rate was approximately 60%. Therefore we expected that the Tajiri cohort was more likely to include those with dementia or questionable dementia and thus have lower scores in recall items. In a study comparing MMSE item scores between patients with Alzheimer's disease in the U.K. and U.S.A. (Gibbons et al., 2002), U.K. patients had more relative difficulty in registering and recalling the three objects. The authors of the study suggested as a partial reason that it was more difficult to create a single visual image of the three objects used by the U.K. patients (tree/clock/boat) than the three objects used by the U.S. patients (apple/penny/table), which may have made them harder to remember. In the Japanese version of MMSE, the three words used were cherry blossom/cat/train (Sakura, Neko, and Densha, respectively in Japanese) and it is unlikely that these words were easier to visualize than the three words used in MoVIES (apple/penny/table).

The better performance in recall among the Tajiri group could suggest that the participants in the Tajiri cohort had a lower prevalence of dementia or cognitive impairment compared with the participants in MoVIES. The overall prevalence of dementia in Tajiri was 8.5% (Meguro et al., 2002), using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) while that of MoVIES was 6.4% using DSM-III-R criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). These comparisons do not suggest lower dementia prevalence in the Tajiri cohort. More recently published data (Meguro et al., 2007) showed that the Tajiri cohort had a much lower incidence of dementia than that found in the MoVIES cohort (Ganguli et al., 2000). However, the MoVIES study used two-year follow up while the Tajiri study used five-year follow up and might have underestimated dementia cases among those who died between assessments. This makes difficult a fair comparison of incidence rates between the two cohorts.

In addition to recall, the Tajiri cohort showed better performance on the three-step auditory comprehension item. Auditory comprehension is sensitive to test administration artifacts such as whether the interviewer handed the paper towards the right hand as opposed to the middle (neutral position), whether they emphasized the word “right”, or whether the instruction was to place the paper on the table vs. on the floor. However, we pursued this matter with the neuropsychologists who trained the interviewers for each site and could not find any significant administration differences in these aspects. It is possible that better performance on this item may be related to this cohort's better memory as demonstrated on the recall item.

A potential limitation is that the prevalence of vision or hearing impairment which could affect certain items was not examined. However, the proportion of those with a maximum score for “registration” was similar between the two cohorts. This suggests that the difference in the prevalence of hearing impairment should not have influenced the recall scores to a large extent. Both cohorts were recruited from geographically circumscribed regions, and, while representative of those regions, results may not be generalizable to other regions. We are reporting here a post-hoc comparison of two separate studies that were conducted independently, and whose designs were not harmonized at the time they were implemented. Comparing the MMSE items of the two cohorts was not the original aim of either study, but our main objective here is to demonstrate potential cultural and linguistic issues which could affect the test results differently in two countries. As noted, the Tajiri study did not enter individual item score for the time and place orientation subtests. Also, we could not use ordinal logit models for any items with continuous scores due to the violation of proportional odds assumptions. Treating the scores as categorical rather than continuous variables may have resulted in loss of some information.

Cultural effects on MMSE test results have been previously examined for various countries and ethnic groups (e.g. Ganguli et al., 1995; Mungas et al., 2000; de Silva and Gunatilake, 2002; Stewart et al., 2002; Crane et al., 2006; Jones, 2006; Morales et al., 2006; Ramirez et al., 2006; Inzelberg et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2007; Kohn et al., 2008). To facilitate cross-cultural comparisons in cognitive functions between Japanese and U.S. cohorts and those among Japanese-Americans, the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI; Teng et al., 1994) was developed and used in past epidemiological studies (e.g. Yamada et al., 1999; Graves et al., 1999; Bond et al., 2005). However, to our knowledge, ours is the first study to compare item-by-item scores in the MMSE between the U.S.A. and Japan, using representative cohorts of community-dwelling elderly people.

In summary, our study showed that even though the median score is similar between the two groups, the distribution of item-by-item scores can vary significantly. The results of this study reaffirm the importance of validation and careful examination of cut-points within each cohort when the MMSE is used as a dementia screening tool or for identifying those with cognitive impairments.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported partly by the National Institute on Aging in the United States (K01AG023014, R01AG07562, and K24AG023014), and the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Public Welfare Work on Elderly: 1992-1992, and the Uehiro Foundation on Ethics and Education in Japan. We greatly appreciate the time and efforts of the participants in the two studies examined in this paper. We thank Dr. Katherine Wild at Oregon Health and Science University for her helpful comments. Part of this study was presented at the 60th Annual Gerontological Society of America Meeting in San Francisco (November 2007).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None.

References

- Akanuma K, Meguro K, Hashimoto R, Ishii H. Spontaneous writing in very mild Alzheimer's disease: analysis of MMSE by older residents in a community. Higher Brain Research. 2004;24:360–367. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd edn, revised American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GE, Burr RL, McCurry SM, Rice MM, Borenstein AR, Larson EB. Alcohol and cognitive performance: a longitudinal study of older Japanese Americans. The Kame Project. International Psychogeriatrics. 2005;17:653–668. doi: 10.1017/S1041610205001651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, van Belle G, Larson EB. Test bias in a cognitive test: differential item functioning in the CASI. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;23:241–256. doi: 10.1002/sim.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, et al. Differential item functioning related to education and age in the Italian version of the Mini-mental State Examination. International Psychogeriatrics. 2006;18:505–515. doi: 10.1017/S1041610205002978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croisile B, Brabant MJ, Carmoi T, Lepage Y, Aimard G, Trillet M. Comparison between oral and written spelling in Alzheimer's disease. Brain and Language. 1996;54:361–387. doi: 10.1006/brln.1996.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva HA, Gunatilake SB. Mini-mental State Examination in Sinhalese: a sensitive test to screen for dementia in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;17:134–139. doi: 10.1002/gps.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, et al. Sensitivity and specificity for dementia of population-based criteria for cognitive impairment: the MoVIES project. Journal of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 1993;48:M152–161. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.m152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, et al. A Hindi version of the MMSE: the development of a cognitive screening instrument for a largely illiterate rural elderly population in India. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1995;10:367–377. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, Dodge HH, Chen P, Belle S, DeKosky ST. Ten-year incidence of dementia in a rural elderly US community population: the MoVIES Project. Neurology. 2000;54:1109–1116. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons LE, et al. Cross-cultural comparison of the Mini-mental State Examination in United Kingdom and United States participants with Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;17:723–728. doi: 10.1002/gps.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves AB, Rajaram L, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, McCurry SM, Larson EB. Cognitive decline and Japanese culture in a cohort of older Japanese Americans in King County, WA: the Kame Project. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1999;54:S154–161. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.3.s154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton RK, Swaminathan H, Rogers HJ. Fundamentals of Item Reponse Theory. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Inzelberg R, et al. Education effects on cognitive function in a healthy aged Arab population. International Psychogeriatrics. 2007;19:593–603. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206004327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki J, et al. A normative, community-based study of Mini-mental State in elderly adults: the effect of age and educational level. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1998;53:P359–363. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.6.p359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RN. Identification of measurement differences between English and Spanish language versions of the Mini-mental State Examination: detecting differential item functioning using MIMIC modeling. Medical Care. 2006;44:S124–133. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245250.50114.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R, Vicente B, Rioseco P, Saldivia S, Torres S. The Mini-mental State Examination: age and education distribution for a Latin American population. Aging and Mental Health. 2008;12:66–71. doi: 10.1080/13607860701529999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguro K, et al. Prevalence of dementia and dementing diseases in Japan: the Tajiri Project. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2002;16:261–269. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguro K, et al. Incidence of dementia and associated risk factors in Japan: the Osaki-Tajiri Project. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2007;260:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales LS, Flowers C, Gutierrez P, Kleinman M, Teresi JA. Item and scale differential functioning of the Mini-mental State Exam assessed using the Differential Item and Test Functioning (DFIT) framework. Medical Care. 2006;44:S143–151. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245141.70946.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungas D, Reed BR, Marshall SC, Gonzalez HM. Development of psychometrically matched English and Spanish language neuropsychological tests for older persons. Neuropsychology. 2000;14:209–223. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.14.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neils J, Roeltgen DP, Greer A. Spelling and attention in early Alzheimer's disease: evidence for impairment of the graphemic buffer. Brain and Language. 1995;49:241–262. doi: 10.1006/brln.1995.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TP, Niti M, Chiam PC, Kua EH. Ethnic and educational differences in cognitive test performance on Mini-mental State Examination in Asians. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:130–139. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000235710.17450.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platel H, et al. Characteristics and evolution of writing impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia. 1993;31:1147–1158. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(93)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M, Teresi JA, Holmes D, Gurland B, Lantigua R. Differential item functioning (DIF) and the Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE): overview, sample, and issues of translation. Medical Care. 2006;44:S95–S106. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000245181.96133.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R, Johnson J, Richards M, Brayne C, Mann A. The distribution of Mini-mental State Examination scores in an older UK African-Caribbean population compared to MRC CFA study norms. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;17:745–751. doi: 10.1002/gps.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng EL, et al. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. International Psychogeriatrics. 1994;6:45–58. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001602. discussion 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, et al. Prevalence and risks of dementia in the Japanese population: RERF's adult health study Hiroshima subjects. Radiation Effects Research Foundation. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47:189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb04577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]