Abstract

Both genetic and epigenetic alterations contribute to Facio-Scapulo-Humeral Dystrophy (FSHD), which is linked to the shortening of the array of D4Z4 repeats at the 4q35 locus. The consequence of this rearrangement remains enigmatic, but deletion of this 3.3-kb macrosatellite element might affect the expression of the FSHD-associated gene(s) through position effect mechanisms. We investigated this hypothesis by creating a large collection of constructs carrying 1 to >11 D4Z4 repeats integrated into the human genome, either at random sites or proximal to a telomere, mimicking thereby the organization of the 4q35 locus. We show that D4Z4 acts as an insulator that interferes with enhancer–promoter communication and protects transgenes from position effect. This last property depends on both CTCF and A-type Lamins. We further demonstrate that both anti-silencing activity of D4Z4 and CTCF binding are lost upon multimerization of the repeat in cells from FSHD patients compared to control myoblasts from healthy individuals, suggesting that FSHD corresponds to a gain-of-function of CTCF at the residual D4Z4 repeats. We propose that contraction of the D4Z4 array contributes to FSHD physio-pathology by acting as a CTCF-dependent insulator in patients.

Author Summary

Facio-Scapulo-Humeral Dystrophy (FSHD) is the third most common myopathy with an autosomal-dominant mode of inheritance. FSHD is caused by contraction of an array of repeated sequences, D4Z4, in the terminal region of chromosome 4 (4q35 locus). This genetic disease is not caused by classical mutations within the sequence of a gene but rather is associated with a change in the organization of the chromatin fiber. Because of the complexity of the region implicated in the disease, the exact pathogenic mechanism is still unclear. Our goal was to engineer genomic tools that would reproduce the organization of the chromosomal region linked to FSHD in order to understand the biological function of the D4Z4 repeat using cellular models. We have identified a new mechanism for the regulation of the D4Z4 array depending on both the number of repeats and the presence of CTCF and A-type Lamins. Our work reveals that D4Z4 acts as a potent insulator element that protects from the influence of repressive chromatin in patient cells but not in controls. Besides the importance of these findings for the understanding of this complex muscular dystrophy, our work also uncovers a new insulator element that regulates chromatin in human cells.

Introduction

The subtelomeric regions that lie between the telomeres and the proximal gene-rich regions display a variable size distribution and contribute to genome evolution but also human disorders [1]. In the Facio-Scapulo-Humeral Dystrophy (FSHD), the contraction of an array of macrosatellite elements at the 4q35 locus is associated with pathological cases [2]. Normal 4q35 chromosome end carries 11 to up to 100–150 integral copies of the 3.3 kb D4Z4 sequence while in FSHD patients, the pathogenic allele has only 1 to 10 repeats [3],[4]. This autosomal dominant disorder is the third most common myopathy, clinically described as a progressive and asymmetric weakening of the muscles of the face, scapular girdle and upper limbs [5]. The nature and function of the genes causing the pathology are still controversial [6],[7],[8]. Indeed, the pathogenic alteration does not reside within a specific gene but the FSHD-associated gene(s) might be rather regulated in cis or trans by chromatin modifications and epigenetic alterations linked to the number of repeats [9]. Several molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain FSHD pathogenesis [9],[10] such as the implication of position effect variegation (PEV) or telomeric position effect (TPE) [9],[10]. However, these hypotheses have never been formally demonstrated.

D4Z4 belongs to a family of repetitive DNA sequences present at different loci in the human genome including the 10qter, which is 98% homologous to the 4q35 region. The array of D4Z4 on chromosome 10 is also polymorphic but is not associated with any disease [11],[12]. Intriguingly, the main difference between the 10qter and the 4q35 locus resides in their respective subnuclear positioning [13],[14] suggesting that the FSHD pathogenesis might result from inappropriate chromatin interactions [15] depending on the number of D4Z4 elements in a particular subnuclear context.

In order to understand the molecular mechanisms leading to FSHD, we investigated the functional properties of the D4Z4 subtelomeric repeat by engineering different cellular models that mimic the basic organization of the 4q35 locus. We found that a single D4Z4 behaves as a potent insulator interfering with enhancer-promoter communication and shielding from chromosomal position effect (CPE). This last property depends upon CTCF and A-type Lamins. Intriguingly, both CTCF binding and insulation activity are lost upon multimerization of the repeats suggesting that FSHD results from an inappropriate insulation mechanism and a CTCF-gain of function. The implication for FSHD pathogenesis is discussed.

Results

D4Z4 Behaves as an Insulator Element

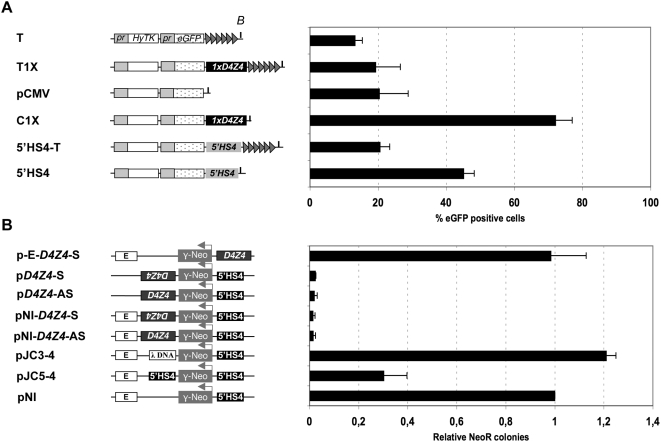

In order to investigate the function of the D4Z4 subtelomeric repeat in the protection against CPE or TPE, we first asked whether a single repeat interferes in cis with the expression of an eGFP reporter gene using constructs stably integrated into the C33A human cells either randomly or at chromosome ends after telomeric fragmentation (Figure S1A). Chromosomal or Telomeric position effects (CPE or TPE respectively) are monitored by flow cytometry analysis (FACS) and manifest as variability from population to population in the percentage of cells expressing the eGFP reporter. In cells stably transfected with the T construct, telomere proximity reduces the percentage of eGFP positive cells compared to the pCMV vector that integrates randomly (Figure 1A, Figure S1B) both in polyclonal populations of transfected cells and in isolated clones as previously published [16],[17]. When inserted between a de novo formed telomere and eGFP, a single D4Z4 has little effect on the expression of the reporter gene as indicated by the slight increase in eGFP positive cells in the population of cells carrying the T1X compared to cells containing the T construct (Figure 1A, Figure S1B). By contrast, D4Z4 significantly increases the expression of the reporter construct inserted randomly in the genome (C1X vs pCMV, Figure 1A, p<0.0001 using a Student's t-test, Figure S1B). This effect is not attributable to an increased distance between the genomic environment at the site of integration and the reporter gene since progressive silencing is also observed after insertion of 3.5 kb of heterologous DNA (data not shown). Importantly, this potent effect of D4Z4 on the expression of eGFP is not dependent upon the cell type since similar results were obtained in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells (TE671) and mouse myoblasts (C2C12) (Figure S1C). This first observation suggests that D4Z4 acts either as an enhancer or an insulator by activating the eGFP reporter gene or protecting its expression from surrounding sequences. By cloning the D4Z4 element upstream of the eGFP reporter or upstream of the HyTK resistance gene, we showed that D4Z4 does not enhance the eGFP expression and concluded that it may act as an insulator (Figure S2).

Figure 1. A single D4Z4 acts as a boundary that interferes with position effect and enhancer-promoter communication.

A. The different constructs carry a hygromycin resistance gene fused to the herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase suicide gene (HyTK, white box) and an eGFP reporter gene (speckled box), each driven by a CMV promoter (pr). In the T construct, a telomere seed (grey triangles) is added downstream of the eGFP reporter gene in order to create a de novo telomere after random integration followed by a telomeric fragmentation [47]. A single D4Z4 repeat (black box) is cloned downstream of the eGFP gene in pCMV construct (C1X) or between eGFP and the telomere seed in T construct (T1X). We further compared D4Z4 with the canonical chicken 5′ HS4 boundary [19] by cloning this latest sequence into the vectors used for de novo telomere seeding (5′HS4-T) or for random integration (5′HS4). Each constructs were linearized and transfected into the human cervical carcinoma cells (C33A). The level of eGFP was measured by flow cytometry (FACS) for an extended period of time in the presence or absence of Hygromycin B (Figure S1A). Histograms show the average percentage of eGFP positive cells from day 18 to day 29 of three independent transfections ±S.D. shown by error bars, when eGFP expression reaches a plateau (Figure S1B). The integrity of each construct was verified in stable populations of cells (Figure S1D). B. In order to evaluate the enhancer blocking activity of D4Z4, we used the test previously described [19]. The K562 human erythroleukemia cell line was stably transfected with the constructs shown on the left. Each construct carries the neomycin resistance gene driven by the human A β-globin promoter (γ-Neo) flanked with the mouse 5′HS2 enhancer (E). Most constructs contain the 5′HS4 insulator upstream of the promoter in order to block from the influence of regulatory elements at the site of integration. For each assay, colony number was normalized to the un-insulated control (pNI). Data are the average of three independent transfections. The mean values with S.D. are plotted. As controls, the following constructs, kindly provided by Dr. G. Felsenfeld, were used: pNI, no insert; pJC3-4, 2.3 kb of λ DNA; pJC5-4, chicken β-globin 1.2 kb 5′HS4 insulator [19].

Insulators are DNA sequences with two distinct properties. They can protect expression from the spreading of silent chromatin and CPE and they can uncouple promoter transcriptional activity from silencer and enhancer elements when inserted in between [18]. In order to discriminate between chromatin insulation and enhancer blocking activity for D4Z4, we performed enhancer blocking assays [19] by cloning D4Z4 in sense (pNI-D4Z4-S) and antisense (pNI-D4Z4-AS) orientation into the pNI vector between the enhancer and the reporter (Figure 1B). D4Z4 reduced the colony number in an orientation-independent way suggesting that it interferes with transcriptional enhancement. In order to distinguish insulation from repression, the right β-globin insulator (5′HS4) protecting from the influence of regulatory elements at the site of integration was replaced by D4Z4 (p-E-D4Z4-S). In this configuration, the number of G418-resistant colonies is similar to the control indicating that D4Z4 is not a repressor but showing that it protects the γ-Neo gene from the influence of repressive chromatin at the site of integration also in this context. Lastly, we tested the ability of D4Z4 to enhance gene expression by removing the 5′ HS2 enhancer (E) in sense (pD4Z4-S) and antisense (pD4Z4-AS) constructs. In this assay, D4Z4 does not activate γ-Neo expression. We conclude from these experiments that a single D4Z4 is unable to activate or repress the expression of a reporter gene in a sense or antisense orientation, while it is able to block enhancer-promoter communications (Figure 1B). Overall, our findings indicate that D4Z4 acts both as a transcriptional insulator (boundary element) protecting against the repressive influence of various chromosomal contexts and as an enhancer insulator interfering with enhancer-promoter communication. The 5′ HS4 insulator of the chicken b-globin locus [19] behaves similarly in our randomly integrated construct settings, albeit at a lower efficiency against CPE (Figure 1A).

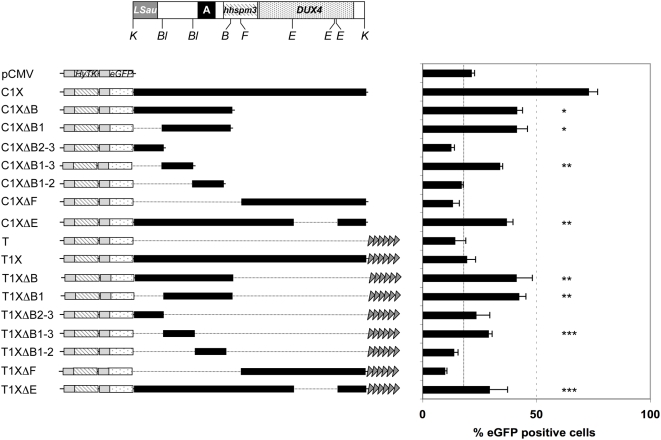

Next, we mapped the portion of D4Z4 responsible for this insulation activity by studying eGFP expression in constructs encompassing various truncated forms of D4Z4. Approximately half of the anti-silencing activity of D4Z4 is present within a 432-bp region (position 382 to 814, C1XΔB1-3, Figure 2, p<0.0001 compared to pCMV using a Student's t-test,) called hereafter the proximal insulator. Interestingly, in contrast to the full-length D4Z4 element, this proximal insulator also counteracts TPE suggesting an antagonistic effect between the proximal insulator and a distal silencer in a telomeric context (T1XΔB1-3, Figure 2). In agreement with this possibility, a construct containing the distal sequence (position 1549 to 3303) inserted either randomly (C1XDF) or terminally (T1XDF) is more repressed than the control eGFP. Moreover, a D4Z4 sequence deleted of a distal 623 bp fragment (DE, deletion from position 2269 to 2892) recapitulates the insulator activity of the 1–1381 proximal fragment (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mapping of the regulatory fragments within D4Z4.

A. Schematic representation of the D4Z4 element from position 1 to 3303 given relative to the two flanking KpnI sites (K) (to scale). The different regions within D4Z4 are indicated: LSau repeat (position 1–340), Region A (position 869–1071), hhspm3 (position 1313–1780), DUX4 ORF (position 1792–3063). The different restriction sites used for the cloning of D4Z4 subfragments are indicated (B: BamHI; Bl: BlpI; F: FseI; E: EheI). B. Different fragments obtained after digestion of D4Z4 were cloned downstream of the eGFP reporter (“C” constructs) or between the reporter gene and the telomeric seed (“T” constructs). Linearized plasmids were transfected into C33A cells and the percentage of eGFP positive cells was monitored by flow cytometry for an extended period of time. The histogram represents the mean value of the percentage of eGFP positive cells from day 18 to day 29 when eGFP expression reaches a plateau±S.D shown by error bars. Fragments DB2-3 (position 1 to 382), DB1-2 (position 814 to 1381) and DF (position 1549 to 3303) do not abrogate TPE or CPE while fragment DB1 (position 1 to 1381), DB1-3 (position 382 to 814) and DE (deleted of a distal 623 bp fragment from position 2269 to 2892) protect from CPE and TPE. Asterisks denote statistically significant values relative to control vectors (pCMV or T) (Student's t test). * p<0.001; **p<0.005; *** p<0.05.

Thus, we conclude that much of the insulator activity against CPE and TPE is concentrated in the 432-bp proximal insulator while a silencer might be present in the distal portion of D4Z4.

CTCF Binds to the Insulator Portion of D4Z4

Since in human cells, most insulators are bound by the multivalent CTCF protein [20],[21], we searched in silico for CTCF binding sites across the 3.3 kb D4Z4 sequence using the consensus binding site at the chicken β-globin locus [22],[23]. Remarkably, the best matches were found within the proximal insulator, at position 468–481 and 476–489 (Figure S3A). Gel retardation assays were carried out to determine whether the sequence containing these two overlapping sites is capable of binding to CTCF (Figure S3B). The mobility was compared to the chicken β-globin FII 5′HS4 site [22],[23] and we showed that both fragments produced a DNA-protein complex when incubated with nuclear extracts. These complexes can be disrupted by incubation with excess of unlabelled probes corresponding to the chicken b-globin FII or mouse TAD1 [24] CTCF sites suggesting that CTCF specifically binds to the 5′ end of D4Z4 (Figure S3B).

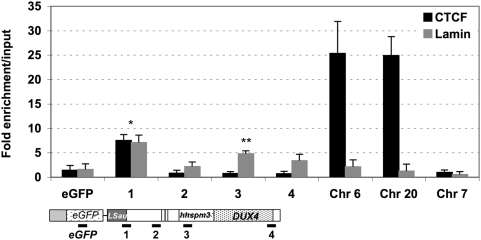

Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments (ChIP) reveal a nearly 8-fold enrichment for CTCF at this proximal insulator compared to an unrelated gene (Figure 3). Under these ChIP conditions, other known CTCF sites [25] on chromosomes 6 and 20 show a high level of enrichment, while no enrichment was observed for D4Z4 regions located distally to the insulator, the adjacent eGFP gene or for an unrelated region on chromosome 7 (Figure 3). Importantly, this enrichment is lost in CTCF-depleted cells (Figure S3C, D).

Figure 3. CTCF and A-type Lamins bind to D4Z4 in vivo.

We searched in silico for CTCF binding sites across the 3.3 kb D4Z4 sequence (Genbank accession number AF117653) using the consensus binding site at the chicken β-globin locus [22],[23]. Two sites were identified at the 5′ end of D4Z4 and the binding was investigated by ChIP using antibodies to CTCF. We also investigated the involvement of A-type Lamins using specific antibodies. Enrichment of the immunoprecipitated DNA fraction with antibodies compared to input DNA was determined after real-time Q-PCR amplification (y-axis) for different primer pairs. Values were normalized to the Histone H4 internal standard. Each bar is the average of at least three independent experiments with the S.D. shown by error bars. “eGFP” amplifies the eGFP sequence. The position of the primers within D4Z4 is indicated (sets 1–4). Using high-throughput analysis, numerous CTCF binding sites were recently identified and many of these sites also correspond to Cohesins enrichment [25]. We then asked if Cohesins/CTCF complex also contains A-Type Lamins and amplified DNA immunoprecipitated with Lamins A/C antibodies with primers corresponding to chromosome 6 (Chr 6). We observed a strong enrichment for CTCF but not Lamins at this site suggesting that CTCF/Cohesins and CTCF/Lamins bind distinct sites. A sequence on chromosome 20 (Chr 20) was reported as a site for CTCF only and does not bind A-type Lamins. Chr 7 primers are CTCF-negative control. Asterisks denote statistically significant values (** p<0.001; *p<0.005; Student's t test).

CTCF Is Necessary but not Sufficient for D4Z4 Insulation

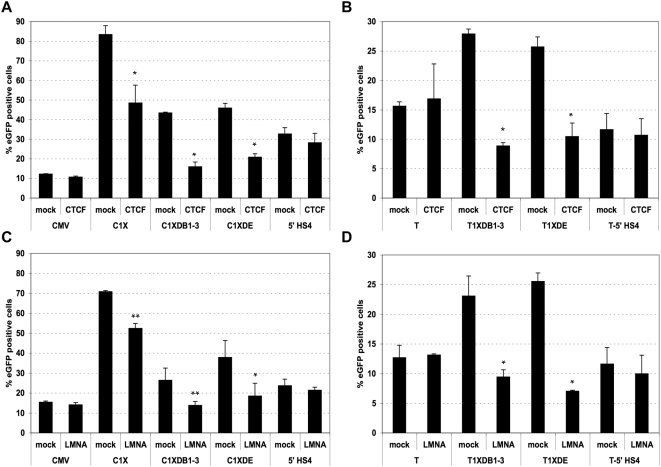

Then, we tested the putative effect of CTCF on the insulator activity of D4Z4 by transfecting the cells with different siRNAs that inhibit the expression of the CTCF gene (Figure S4A). The percentage of eGFP positive cells and intensity of fluorescence decrease in C1X cells subjected to a CTCF knock-down (KD) (Figure 4A) and in cells containing short fragments encompassing the proximal D4Z4 insulator fragment either at the telomere (Figure 4B) or at random sites (Figure 4A, Figure S4C) suggesting that the knock-down of CTCF alters the anti-silencing properties of D4Z4. Of note, the effect of CTCF depletion observed with different siRNAs renders unlikely an off-target activity and does not significantly increases apoptosis in the time frame of the assay (Figure S4B). Moreover, it is also specific for CTCF since the reduced levels of another factor reported to bind to D4Z4, YY1 [7], or proteins involved in the insulation properties of the chicken 5′HS4, USF1 and 2 [26], have no effect on eGFP expression (Figure S4E). Noteworthy, at the chicken 5′ HS4 insulator, CTCF is only involved in the enhancer blocking activity [27] and consistently, CTCF depletion does not modify the expression of the eGFP reporter protected by this insulator in our system suggesting that the mechanisms involved in the regulation of the 5′HS4 insulator and D4Z4 are different.

Figure 4. Depletion in CTCF or A-type Lamins abrogates D4Z4 anti-silencing activity.

The involvement of CTCF and A-type lamins in the insulating activity of D4Z4 was studied by knocking-down their expression. A. Different populations of cells transfected with randomly integrated constructs were transfected with siRNA against CTCF (CTCF) or negative control siRNA (mock) and the level of eGFP was monitored by FACS. The mean value±S.D of three independent experiments are presented. B. Telomeric constructs harboring protection against TPE (T1XDB1-3, T1XDE) and control (T, T-5′ HS4) were transiently transfected with pools of siRNA against CTCF. The expression of the eGFP reporter gene was analyzed by FACS. C. D. The different constructs allowing the protection against CPE (C1X, C1XDB1-3, C1XDE, pCMV-5′ HS4) (panel C) or protection against TPE (T1XDB1-3, T1XDE) (panel D) were transiently transfected with siRNA against Lamins A/C and the expression of the eGFP reporter gene was measured by FACS. Asterisks denote statistically significant values relative to control siRNA (Student's t test). **p<0.01; *p<0.001.

Finally, there is no effect of CTCF KD in cells carrying a D4Z4-less construct (pCMV), showing that depletion of this protein does not alter the expression of our eGFP reporter in general but specifically impairs the insulator activity of D4Z4 (Figure 4A).

Overall, these results show that CTCF is required for the insulation activity of D4Z4. Nevertheless, if CTCF is necessary for this property, it does not appear to be sufficient, since truncated forms of D4Z4 containing the 5′ CTCF site only partially recapitulate the anti-silencing function of the whole repeat.

A-Type Lamins Bind to D4Z4 and Contribute to Its Insulation Activity

Since the localization of the 4q35 locus at the nuclear periphery is compromised in cells carrying a homozygous mutation of the LMNA gene [13], we hypothesized that A-type Lamins may contribute to D4Z4 functions and we investigated this possibility by transfecting pools of siRNAs in different populations (Figure 4C,D). Depletion of A-type Lamins (Figure S4D) decreases the percentage of eGFP positive cells and intensity of fluorescence in cells carrying a randomly inserted eGFP reporter protected by the D4Z4 insulator (C1X, C1XDB1-3; C1XDE cells, Figure 4C, Figure S4C). Interestingly, decreased insulation is also observed in cells containing the proximal D4Z4 insulator element at chromosome ends (T1XDB1-3, T1XDE, Figure 4D) suggesting that A-type Lamins are necessary for the proper anti-silencing function of D4Z4 and participate in the protection against TPE in the absence of the distal silencer element. However, LMNA knock-down does not change the level of eGFP in the absence of D4Z4 (T construct) or in the presence of the 5′-HS4 insulator at chromosome ends (5′ HS4-T, Figure 4D). This effect is not merely the consequence of disruption of the nuclear periphery or depletion of components of the lamina since the knock-down of B-type Lamins (LMNB) or the Lamin A-associated protein, BAF1 has not effect on eGFP expression (Figure S4E). Then, we investigated by ChIP whether A-type Lamins associate with D4Z4-tagged telomeres in our cellular model. We found that Lamins A/C are specifically enriched along the D4Z4 repeat with a peak at the proximal insulator sequence where CTCF is bound (Figure 3) and concluded from this analysis that D4Z4 interacts with A-type Lamins. These results show that Lamins A/C are involved in the anti-silencing activity of D4Z4 and uncovers the involvement of both CTCF and A-type Lamins in the regulation of an insulator in human cells.

The Multimerization of D4Z4 Suppresses Protection against Silencing and CTCF Binding

Since D4Z4 is repeated in tandem at several chromosomal loci, including the 4q subtelomeres where it is linked to FSHD, we explored whether the multimerization of D4Z4 alters its properties. At telomeres, adding up to 12 copies of D4Z4 slightly weakens telomeric silencing suggesting that a large D4Z4 array may act as a fuzzy boundary shielding from the repressive effect of telomeric chromatin when D4Z4 directly abuts the telomere (Figure 5A). However, this situation might not directly reflect the natural genomic context since the distance between D4Z4 and the telomere is estimated to be around 25–50 kb and other subtelomeric sequences might also exert an effect on the D4Z4 arrays.

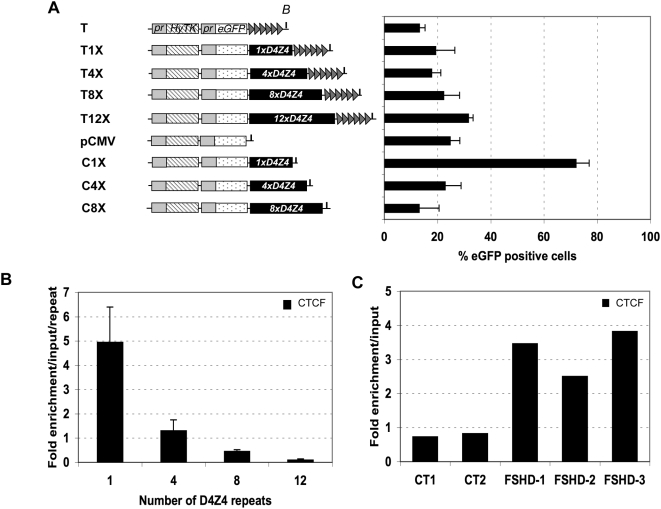

Figure 5. The multimerization of D4Z4 abrogates CTCF binding and insulation activity.

A. The expression of eGFP was measured by FACS on populations of cells transfected with telomeric constructs carrying 0, 1, 4, 8 or 12 copies of D4Z4 downstream of the telomeric seed (T, T1X, T4X, T8X, T12X) or internal constructs (pCMV, C1X, C4X, C8X) containing respectively 0, 1, 4 or 8 copies of D4Z4. The integrity of each construct was verified in stable populations of cells after either random integration or telomeric fragmentation (Figure S1D). Histograms show the average percentage of eGFP positive cells from day 18 to day 29±S.D. shown by error bars, when eGFP expression reaches a plateau. In the different constructs containing D4Z4 inserted at random sites (C4X, C8X), the level of eGFP is proportionally decreased when the number of repeats is increased suggesting that the repeated element loses its anti-CPE activity upon multimerization. On the opposite, eGFP level is slightly increased at telomeres (see main text). B. The binding of CTCF was investigated by ChIP on the different populations of cells carrying different number of D4Z4 element downstream of the eGFP reporter gene. Input DNA and DNA fraction immunoprecipitated with antibodies to CTCF were amplified by a real-time Q-PCR method (x-axis) using primers encompassing the 5′ CTCF site. The y-axis shows the fold enrichment of CTCF in the bound fraction versus input chromatin. Each data point is the average of at least three independent experiments with the S.D. shown by error bars. C. ChIP analysis of CTCF binding in two different control (CT1 and CT2, >11 D4Z4 repeats) and three different myoblasts from FSHD patients (FSHD1, 5 repeats; FSHD 2, 6 repeats; FSHD 3, 7 repeats).

We showed that adding up to 8 D4Z4 elements progressively abolishes the insulation activity in randomly integrated constructs suggesting that the repeated element looses its anti-silencing activity upon multimerization (Figure 5A). Consistent with this hypothesis, loss of anti-silencing correlates with the loss of CTCF binding (Figure 5B) and a slight increase in the trimethylation of lysine 9 residues on histone H3 tails, a mark of silenced chromatin (Figure S5). Impressively, the gain in CTCF binding was also observed in myoblasts from FSHD patients compared to controls suggesting that the binding of CTCF to the D4Z4 repeats is a molecular marker of FSHD muscle (Figure 5C). We propose that reduction of the D4Z4 array in FSHD patients allows the binding of CTCF and provokes changes in the biological function of D4Z4 that switches from a repressor to an insulator protecting the expression of the FSHD gene(s).

Discussion

By analyzing the behavior of the D4Z4 subtelomeric element in various chromosomal settings, we demonstrated that this repeat behaves as a CTCF and A-type Lamins-dependent transcriptional insulator. These features are specific for D4Z4 since they are not shared by the CTCF-dependent 5′HS4 b-globin insulator where CTCF only shields against enhancer-promoter communication [27]. As a single repeat, D4Z4 binds to CTCF and A-type Lamins, behaves as a transcriptional insulator, preventing both the communication between a cis-regulatory element and a promoter (enhancer blocking activity) and protecting against chromosomal position effect (anti-silencing activity) (Figure 6). Upon multimerization of D4Z4, CTCF binding is impaired. Thus, the experiments presented here reveal a novel mode of chromatin regulation controlled by the number of D4Z4 repeats. Furthermore, our data uncover a novel property for A-type Lamins in the protection against CPE in human cells as observed in Drosophila [28],[29],[30] and suggested by the previous co-purification of A-type Lamins and CTCF in HeLa cells [31].

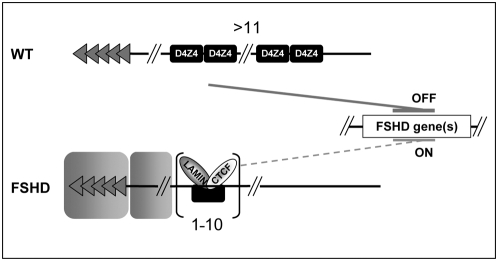

Figure 6. Model explaining the role of the D4Z4 insulator and its implication in the epigenetic alteration of FSHD.

In normal cells, the multimerization of D4Z4 compromises CTCF binding and the boundary activity is counteracted (upper panel). In this conformation, the D4Z4 array might repress gene expression either at the 4q35 locus or at a long distance from the array. In patients, D4Z4 acts as an insulator that protects the expression of different loci from repressive structures such as the 4q terminus or other subtelomeric surrounding sequences. This boundary activity depends upon CTCF and Lamins A/C (lower panel). The exclusion of CTCF from multiple repeats and the presence of a silencer element within D4Z4 [7] might suggest that the D4Z4 array behaves as a silencer. However, the presence of up to 12 copies of the repeat does not repress the expression of the neighboring eGFP reporter in our experimental settings where the D4Z4 array directly flanks the telomere and argues against the hypothesis that multiple D4Z4 repress in cis the expression of genes. An alternative explanation is that multiple D4Z4 cooperates with other elements of the 4q region to form a silencer, as suggested by the link between D4Z4 array contraction and a particular allele of 4q35 in patients [37].

The association between the CTCF-dependent 5′ HS4 insulator and the nucleolus [31] and recent data showing that Cohesins [25],[32] or Emerin and B-type Lamins [33] can colocalize with CTCF throughout the genome, suggest that this protein interacts with different key components of the nuclear architecture to mediate transcriptional insulation and organization of human chromosomes. In agreement with the possible existence of different classes of CTCF-dependent insulators, we have been unable to detect a significant enrichment of Lamins A/C at the CTCF sites at chromosomes 6 and 20 (Figure 3) and the KD of nucleolin or SCC1 [25] has no effect on the antisilencing activity of D4Z4 (Figure S6). Together with a recent publication on an unrelated macrosatellite repeat on the X chromosome [34], our work further extends the notion that CTCF is implicated in the functional organization of the genome by showing that it interacts also with repeated elements and suggests a genome-wide role in the formation of chromatin boundaries at the transition between transcribed regions and silenced chromatin through the association with different specialized complexes and may thereby direct the corresponding chromosome segment to specialized subnuclear compartments.

Importantly, we showed that CTCF is specifically recruited to the 4q35 region of FSHD patients. Similar observations were made by G. Fillipova & colleagues (personnal communication). The relationship between a reduced number of D4Z4 sequences and a gain-of-function of a CTCF-dependent insulation activity suggests an alternative mechanism for FSHD physiopathology based on a switch of activity from a repressor to an insulator element (Figure 6). Indeed, most FSHD patients have less than 11 copies of D4Z4 at 4q35 and the severity of the disease negatively correlates with the number of residual repeats [35],[36]. The shortening of the array would both eliminate the silencer properties of D4Z4 [7] and unmask an insulator function that may protect the FSHD genes from silencing emanating either from the 4q terminus or the β-satellite-rich region on the 4qA allele that was reported to co-segregate with the disease [37],[38]. Noticeably, in the human genome, β-satellite elements are often found in the vicinity of D4Z4 repeats [39] raising the possibility for a role of the D4Z4 insulator as a barrier between euchromatin and heterochromatin-like sequences. Since the D4Z4 array is hypermethylated when present in high copy number [40] and since CTCF binding can be compromised by DNA methylation [22],[41] or block the spreading of this DNA modification [21], a likely hypothesis is that CTCF binding modulates the biological function of D4Z4 in cooperation with changes in the pattern of DNA methylation. However, in agreement with previous observation [42],[43], the silencing activity observed upon multimerization of D4Z4 does not seem to be associated with a massive heterochromatinization of the array of repeats (Figure S5). Therefore, we propose a model in which the loss of CTCF binding changes the spatial configuration of the region rather than the condensation of the chromatin of the locus.

Our results also implicate CTCF and A-type Lamins as important players in FSHD. In agreement with this notion, patients with FSHD display some clinical and transcriptional resemblances to Emery-Dreifuss, a muscular dystrophy linked to mutation in the LMNA gene [44], suggesting that the affinity of D4Z4 for A-type lamins might contribute to the epigenetic regulation of the 4q35 locus by providing the proper subnuclear environment for the regulation of the gene(s) causing the dystrophy. Together with the matrix attachment sites at the 4q35 locus [15], the subnuclear localization of the 4q35 locus at the edge of the nucleus [13],[14] and the positioning activity of D4Z4 at the nuclear periphery (Ottaviani et al., submitted), the association of D4Z4 to these two proteins might create functional domains involved in insulation mechanisms. Although one cannot exclude that soluble lamins A/C are bound to D4Z4, one can speculate that depending on the position of the locus at the nuclear periphery, the lamina may either provide a high concentration of regulatory factors or favor looping between distant sequences. With respect to FSHD, the corollary of this hypothesis is that the pathogenic 4q35 allele carrying a shortened D4Z4 array might be repositioned along the inner nuclear envelope from a repressive to a permissive compartment modulating thereby the microenvironment of the genes causing the disease.

Thus, beyond the importance of a better characterization of D4Z4 for its relevance to the peculiar Facio-Scapulo-Humeral dystrophy, this work reveals the existence of a human insulator element that depends on both CTCF and A-type Lamins. In addition, this work suggests that the mosaic nature of human subtelomeres might directly influence the higher-order organization of the corresponding chromosome end. This may serve as a paradigm for our understanding of numerous pathologies linked to subtelomeres such as idiopathic mental retardation.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinky. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. All patients provided written informed content for the collection of samples and subsequent analysis.

Cellular Models

The pCMV and pCMVTelo plasmids are described in Koering et al [17]. Experimental details and characterization of the cell lines are given in Text S1.

RNA Interference

We used pre-annealed small interfering RNAs (siRNAs): siGENOME SMARTpool reagent, human CTCF (M-020165-01); human LMNA (NM_170707) (Dharmacon), Silencer™ Negative Control #1 siRNA (Ambion). Transfections were performed with DharmaFECT 1™ (Dharmacon) with 200 pmoles siRNA for 2×105cells. Efficient knock-down was determined by quantitative RT-PCR or Western blot. See Text S1.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

In vivo protein-DNA cross-linking was carried out as described [24]. Nucleoprotein complexes were sonicated to reduce DNA fragments to 400–600 bp using a Bioruptor sonifier (Diagenode). Immunoprecipitation was performed with a rabbit polyclonal anti-CTCF (Upstate Biotechnologies, ref 07-729) or a goat polyclonal anti-Lamins A/C (Santa Cruz, ref SC6215, [45],[46]). After immunoprecipitation, DNA samples were quantified using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop technologies) and enrichment of the immunoprecipitated fraction was quantified by Real Time Q-PCR (Text S1).

Supporting Information

Contraction of the D4Z4 array unmasks a boundary activity. A. Description of the seeding constructs and procedure. Telomere seeding is based on the non-targeted introduction of cloned telomeres into mammalian cells. The constructs carry a hygromycin resistance gene fused to the herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase suicide gene (HyTK), an eGFP reporter gene, both driven by CMV promoters. We inserted D4Z4 between the reporter and the telomere in order to investigate the effect of D4Z4 on gene expression. The transfection of constructs linearized downstream of a 1.2 kb (TTAGGG)n seed of human telomeric repeats (BstXI site, B) allows de novo telomere formation at the integration site while constructs lacking these repeats integrate randomly in the host genome. Conditions of transfection of the C33A cell line were optimized in order to have a single integration of the transgene per cell. Successful de novo formation of eGFP-tagged telomeres and single integration was confirmed in the polyclonal population of transfected cells and in a set of clones by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on metaphase spreads (as illustrated in photographs 1, 2 for telomeric insertion and in photographs 3, 4 for internal integration) and by detection of a diffuse hybridization signal in Southern blot (data not shown). In agreement with previous data, the rate of de novo telomere formation in stably transfected cells is very high in the C33A cells reaching 80–90% of the hygromycin resistant cells for the T and T1X constructs. We also confirmed by Multiplex FISH analysis that in the presence of D4Z4, the constructs do not integrate at preferential sites (Ottaviani et al., Submitted). Three days after transfection, Hygromycin B was added to the medium. Then, cells were grown for an extended time in selective medium. The percentage of eGFP-positive cells and the average level of eGFP were monitored by Flow Cytometry (FACS) every 3 days for up to 90 days. B. Kinetics of the expression of eGFP. After 10–12 days, the percentage of eGFP-positive cells decreases in cells containing the T construct that plateaus at 10–20%. A low eGFP expression is also observed in cells carrying a single D4Z4 element at a subtelomeric position (T1X). On the opposite, the level of eGFP is high in C1X cells and remains constant throughout the course of the assays. C. The pCMV and C1X constructs were transfected into C2C12 mouse myoblasts or a human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line (TE671) and the level of eGFP was monitored by FACS for up to 30 days. As previously described for C33A cells, D4Z4 protects the expression of the eGFP from CPE in the different cell types tested indicating that insulation mediated by D4Z4 is not dependent upon the cell type. D. The integrity of each construct was verified by Quantitative PCR from genomic DNA of hygromycin resistant cells using different set of primers. The Ct values obtained for each construct were normalized to the H4 promoter as an internal control and compared to the values obtained for the T construct containing only the resistance gene, eGFP reporter and the telomere seed. Untransfected C33A cells were used as negative control (data not shown). For each primer set, the average fold-increase from 3 independent cell populations (±S.D. shown by error bars) is indicated in representative populations of cells. The eGFP sequence and the 3′ end of the construct can be detected in the different populations while the number of D4Z4 increases in cells transfected with vectors containing multiple copies of the repeats.

(0.7 MB TIF)

D4Z4 does not enhance eGFP expression. In order to test the role of D4Z4 in the control of gene expression, the repeat was cloned upstream of the pCMV promoter driving the eGFP reporter (1XC construct) or upstream of the pCMV promoter driving the HyTK resistance gene (X1C construct) and compared to the pCMV control vector or the C1X construct. When present upstream of the eGFP reporter or the HyTK gene, D4Z4 does not enhance the expression of the reporter indicating that D4Z4 does not act as a transcriptional enhancer in these situations.

(8.3 MB TIF)

CTCF binds to D4Z4 in vitro. To determine whether the candidate CTCF binding sequences (A) are capable of binding to CTCF, gel retardation assays were carried out (B). The mobility was compared to the chicken b globin FII 5′HS4 site. The FII (lane 1) and D4Z4 CTCF site (lane 5) can be supershifted by incubation with a CTCF antibody (star). We also used unlabelled oligonucleotides corresponding to known CTCF binding sites for competition assays. C33A nuclear extracts were incubated either with labeled FII (lanes 1–4) or 468-S labeled oligonucleotides (lanes 5–8) and molar excess of FII (lanes 3, 7) or TAD1 site at the mouse TCRα-Dad1 locus [24] (lanes 4, 8). Molar excess of unlabeled FII or TAD1 can displace the binding of CTCF from the labeled D4Z4 sequence whereas mutant versions of FII cannot (data not shown) suggesting that the sites at position 468–481 and 476–489 of D4Z4 bind CTCF. C. Different primer sets spanning the construct were used to amplify input DNA and DNA fraction immunoprecipitated with antibodies to CTCF by a real-time Q-PCR method. The y-axis shows the fold enrichment of CTCF in the bound fraction versus input chromatin. Each data point indicates the average of at least three independent experiments with the S.D. shown by error bars. A significant enrichment of more than 7-fold was observed with primers encompassing the putative CTCF binding site showing that CTCF interacts with the D4Z4 repeat in vivo (black bars). This enrichment is lost when chromatin immunoprecipitation is performed on cells transfected with siRNA against CTCF (grey bars). D. Schematic representation of D4Z4 with the position of the primers used for ChIP quantification.

(8.3 MB TIF)

Validation of CTCF and A-type Lamins knock-down. A. C1X and pCMV cell populations were transfected with pools of siRNA against CTCF (pool CTCF), 3 different siRNAs (CTCF 1, 2, 3) or negative control siRNA (sineg) and quantification of CTCF and eGFP mRNA was performed by reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR amplification. The values were normalized to the b-Actin standard. The percentage of CTCF or eGFP mRNA for cells treated with CTCF siRNA vs control cells is indicated. B. CTCF is a versatile protein that regulates numerous pathways in human cells. In order to verify that the KD of CTCF does not affect cell viability and subsequently, eGFP level, cell populations were incubated with BrdU 7 days after transfection and cell cycle was analyzed by flow cytometry. No significant difference could be observed in cells transfected with negative control siRNA (mock) compared to CTCF siRNA (CTCF). C. A population of cells stably transfected with the CDE construct were transiently transfected with negative control siRNA (mock) or siRNA against CTCF or A-type Lamins (LMNA). The percentages of eGFP positive cells were determined by FACs three days after transfection. The leftward shift peak in cells transfected with siRNA to CTCF or LMNA indicates that the intensity of the eGFP is decreased in the pool of eGFP positive cells compared to control cells. D. Different cell populations were transfected with pools of siRNA against products of the LMNA gene. Depletion in A and C type lamins was controlled by western blot on whole cell extracts 4 days (1T) or 7 days (1T+3 days) after a first transient transfection or 4 days after a second transfection (2T) and compared to the level of both proteins in mock-treated cells. A goat polyclonal antibody was used for western blot and ChIP experiments. The total amount of protein in each extract was compared by using an anti-actin antibody E. The specificity of the CTCF and Lamins effects on the activity of D4Z4 was compared to the effect of YY1 that was previously reported to bind to D4Z4 [7], USF1 and 2 that participate in the insulator activity of the chicken 5′HS4 insulator [26] and components of the nuclear Lamina, Lamin B or BAF1. Therefore, T1XDE cells were transiently transfected with pools of siRNA against the different genes or negative control siRNA (mock). The % of eGFP positive cells was determined by FACS 3 to 7 days after transfection and we did not observe a significant decrease in eGFP level in the different populations of transfected cells. Similar results were observed for the other constructs harboring insulator activity.

(0.4 MB TIF)

Loss of CTCF binding only slightly increases the trimethylation of H3 K9 residues. Above the threshold of 11 copies, the D4Z4 array is methylated at the DNA level suggesting that long stretches of D4Z4 become more condensed. CTCF might be important in the control of the chromatin structure and we wanted to test if the loss of CTCF binding that we observed upon D4Z4 multimerization is accompanied by an increase in the trimethylation lysine 9 residues on histone H3 tails. Therefore, ChIP was performed with anti-Me3-H3K9 in cells stably transfected with different D4Z4 vectors. Values were normalized to the histone H4 promoter as a standard and enrichments of the immunoprecipitated DNA compared to input DNA are presented (y-axis).

(1.1 MB TIF)

Cohesins do not participate in the D4Z4 insulator activity. Recently, high throughput techniques allowed the identification of numerous binding sites for Cohesins [25],[32],[51] throughout the human genome. Interestingly, many of these sites also correspond to CTCF sites suggesting that the two proteins might be involved in insulation activity. In order to see whether Cohesins also contribute to D4Z4 activity we transfected the T1XΔE cells with siRNA against SCC1 [25] and measured the expression of eGFP 3 to 7 days after transfection. We did not observe a significant difference after transfection of these siRNA suggesting that Cohesins do not contribute to the activity of D4Z4.

(1.1 MB TIF)

Supplementary information.

(0.09 MB DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Filippova and S. van der Maarel for sharing unpublished results and for discussion. We are grateful to Ms Severine Delplace for the preparation of myoblasts and indebted to the patients for their cooperation. We thank Dr. Gary Felsenfeld for the kind gift of the pNI, pJC5-4 and pJC3-4 vectors and discussion. We acknowledge the facilities of the IFR 128 for Flow Cytometry. We are grateful to Nicolas Lévy, Gisèle Bonne, Evani-Viegas Pequignot, Rossella Tupler, the members of the FSHD consortium coordinated by the Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM) and the members of the laboratory for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

The work in EG's lab was supported by grants from AFM, Programme Emergence de la Région Rhône-Alpes and Lyon Science Transfert (to FM) and Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (Equipe labellisée). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ottaviani A, Gilson E, Magdinier F. Telomeric position effect: From the yeast paradigm to human pathologies? Biochimie. 2008;90:93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wijmenga C, Hewitt JE, Sandkuijl LA, Clark LN, Wright TJ, et al. Chromosome 4q DNA rearrangements associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1992;2:26–30. doi: 10.1038/ng0992-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winokur ST, Bengtsson U, Feddersen J, Mathews KD, Weiffenbach B, et al. The DNA rearrangement associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy involves a heterochromatin-associated repetitive element: implications for a role of chromatin structure in the pathogenesis of the disease. Chromosome Res. 1994;2:225–234. doi: 10.1007/BF01553323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Deutekom JC, Wijmenga C, van Tienhoven EA, Gruter AM, Hewitt JE, et al. FSHD associated DNA rearrangements are due to deletions of integral copies of a 3.2 kb tandemly repeated unit. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:2037–2042. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.12.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tawil R, Figlewicz DA, Griggs RC, Weiffenbach B. Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: a distinct regional myopathy with a novel molecular pathogenesis. FSH Consortium. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:279–282. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixit M, Ansseau E, Tassin A, Winokur S, Shi R, et al. DUX4, a candidate gene of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, encodes a transcriptional activator of PITX1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18157–18162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708659104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabellini D, Green MR, Tupler R. Inappropriate gene activation in FSHD: a repressor complex binds a chromosomal repeat deleted in dystrophic muscle. Cell. 2002;110:339–348. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rijkers T, Deidda G, van Koningsbruggen S, van Geel M, Lemmers RJ, et al. FRG2, an FSHD candidate gene, is transcriptionally upregulated in differentiating primary myoblast cultures of FSHD patients. J Med Genet. 2004;41:826–836. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.019364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Maarel SM, Frants RR. The D4Z4 repeat-mediated pathogenesis of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:375–386. doi: 10.1086/428361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabellini D, Green MR, Tupler R. When enough is enough: genetic diseases associated with transcriptional derepression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewitt JE, Lyle R, Clark LN, Valleley EM, Wright TJ, et al. Analysis of the tandem repeat locus D4Z4 associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1287–1295. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.8.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyle R, Wright TJ, Clark LN, Hewitt JE. The FSHD-associated repeat, D4Z4, is a member of a dispersed family of homeobox-containing repeats, subsets of which are clustered on the short arms of the acrocentric chromosomes. Genomics. 1995;28:389–397. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masny PS, Bengtsson U, Chung SA, Martin JH, van Engelen B, et al. Localization of 4q35.2 to the nuclear periphery: is FSHD a nuclear envelope disease? Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1857–1871. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tam R, Smith KP, Lawrence JB. The 4q subtelomere harboring the FSHD locus is specifically anchored with peripheral heterochromatin unlike most human telomeres. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:269–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrov A, Pirozhkova I, Carnac G, Laoudj D, Lipinski M, et al. Chromatin loop domain organization within the 4q35 locus in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy patients versus normal human myoblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6982–6987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baur JA, Zou Y, Shay JW, Wright WE. Telomere position effect in human cells. Science. 2001;292:2075–2077. doi: 10.1126/science.1062329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koering CE, Pollice A, Zibella MP, Bauwens S, Puisieux A, et al. Human telomeric position effect is determined by chromosomal context and telomeric chromatin integrity. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:1055–1061. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.West AG, Gaszner M, Felsenfeld G. Insulators: many functions, many mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2002;16:271–288. doi: 10.1101/gad.954702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung JH, Whiteley M, Felsenfeld G. A 5′ element of the chicken beta-globin domain serves as an insulator in human erythroid cells and protects against position effect in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;74:505–514. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80052-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaszner M, Felsenfeld G. Insulators: exploiting transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nrg1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Filippova GN. Genetics and epigenetics of the multifunctional protein CTCF. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;80:337–360. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(07)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell AC, Felsenfeld G. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature. 2000;405:482–485. doi: 10.1038/35013100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell AC, West AG, Felsenfeld G. The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell. 1999;98:387–396. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81967-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magdinier F, Yusufzai TM, Felsenfeld G. Both CTCF-dependent and -independent insulators are found between the mouse T cell receptor alpha and Dad1 genes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25381–25389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wendt KS, Yoshida K, Itoh T, Bando M, Koch B, et al. Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature. 2008;451:796–801. doi: 10.1038/nature06634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West AG, Huang S, Gaszner M, Litt MD, Felsenfeld G. Recruitment of histone modifications by USF proteins at a vertebrate barrier element. Mol Cell. 2004;16:453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Recillas-Targa F, Pikaart MJ, Burgess-Beusse B, Bell AC, Litt MD, et al. Position-effect protection and enhancer blocking by the chicken beta-globin insulator are separable activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6883–6888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102179399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerasimova TI, Byrd K, Corces VG. A chromatin insulator determines the nuclear localization of DNA. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Capelson M, Corces VG. Boundary elements and nuclear organization. Biol Cell. 2004;96:617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerasimova TI, Lei EP, Bushey AM, Corces VG. Coordinated control of dCTCF and gypsy chromatin insulators in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 2007;28:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yusufzai TM, Tagami H, Nakatani Y, Felsenfeld G. CTCF tethers an insulator to subnuclear sites, suggesting shared insulator mechanisms across species. Mol Cell. 2004;13:291–298. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parelho V, Hadjur S, Spivakov M, Leleu M, Sauer S, et al. Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell. 2008;132:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, Meuleman W, Faza MB, et al. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nature06947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chadwick BP. DXZ4 chromatin adopts an opposing conformation to that of the surrounding chromosome and acquires a novel inactive X specific role involving CTCF and anti-sense transcripts. Genome Res. 2008 doi: 10.1101/gr.075713.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lunt PW, Jardine PE, Koch MC, Maynard J, Osborn M, et al. Correlation between fragment size at D4F104S1 and age at onset or at wheelchair use, with a possible generational effect, accounts for much phenotypic variation in 4q35-facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD). Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:951–958. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.5.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tawil R, Forrester J, Griggs RC, Mendell J, Kissel J, et al. Evidence for anticipation and association of deletion size with severity in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. The FSH-DY Group. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:744–748. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lemmers RJ, de Kievit P, Sandkuijl L, Padberg GW, van Ommen GJ, et al. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy is uniquely associated with one of the two variants of the 4q subtelomere. Nat Genet. 2002;32:235–236. doi: 10.1038/ng999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas NS, Wiseman K, Spurlock G, MacDonald M, Ustek D, et al. A large patient study confirming that facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) disease expression is almost exclusively associated with an FSHD locus located on a 4qA-defined 4qter subtelomere. J Med Genet. 2007;44:215–218. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.042804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meneveri R, Agresti A, Della Valle G, Talarico D, Siccardi AG, et al. Identification of a human clustered G+C-rich DNA family of repeats (Sau3A family). J Mol Biol. 1985;186:483–489. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Overveld PG, Enthoven L, Ricci E, Rossi M, Felicetti L, et al. Variable hypomethylation of D4Z4 in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:569–576. doi: 10.1002/ana.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hark AT, Schoenherr CJ, Katz DJ, Ingram RS, Levorse JM, et al. CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature. 2000;405:486–489. doi: 10.1038/35013106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang G, Yang F, van Overveld PG, Vedanarayanan V, van der Maarel S, et al. Testing the position-effect variegation hypothesis for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy by analysis of histone modification and gene expression in subtelomeric 4q. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2909–2921. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsumagari K, Qi L, Jackson K, Shao C, Lacey M, et al. Epigenetics of a tandem DNA repeat: chromatin DNaseI sensitivity and opposite methylation changes in cancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2196–2207. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bakay M, Wang Z, Melcon G, Schiltz L, Xuan J, et al. Nuclear envelope dystrophies show a transcriptional fingerprint suggesting disruption of Rb-MyoD pathways in muscle regeneration. Brain. 2006;129:996–1013. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li H, Watford W, Li C, Parmelee A, Bryant MA, et al. Ewing sarcoma gene EWS is essential for meiosis and B lymphocyte development. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1314–1323. doi: 10.1172/JCI31222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen LY, Liu D, Songyang Z. Telomere maintenance through spatial control of telomeric proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5898–5909. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00603-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farr CJ, Stevanovic M, Thomson EJ, Goodfellow PN, Cooke HJ. Telomere-associated chromosome fragmentation: applications in genome manipulation and analysis. Nat Genet. 1992;2:275–282. doi: 10.1038/ng1292-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vilquin JT. Myoblast transplantation: clinical trials and perspectives. Mini-review. Acta Myol. 2005;24:119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Espada J, Ballestar E, Fraga MF, Villar-Garea A, Juarranz A, et al. Human DNA methyltransferase 1 is required for maintenance of the histone H3 modification pattern. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37175–37184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loukinov DI, Pugacheva E, Vatolin S, Pack SD, Moon H, et al. BORIS, a novel male germ-line-specific protein associated with epigenetic reprogramming events, shares the same 11-zinc-finger domain with CTCF, the insulator protein involved in reading imprinting marks in the soma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6806–6811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092123699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stedman W, Kang H, Lin S, Kissil JL, Bartolomei MS, et al. Cohesins localize with CTCF at the KSHV latency control region and at cellular c-myc and H19/Igf2 insulators. Embo J. 2008;27:654–666. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Contraction of the D4Z4 array unmasks a boundary activity. A. Description of the seeding constructs and procedure. Telomere seeding is based on the non-targeted introduction of cloned telomeres into mammalian cells. The constructs carry a hygromycin resistance gene fused to the herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase suicide gene (HyTK), an eGFP reporter gene, both driven by CMV promoters. We inserted D4Z4 between the reporter and the telomere in order to investigate the effect of D4Z4 on gene expression. The transfection of constructs linearized downstream of a 1.2 kb (TTAGGG)n seed of human telomeric repeats (BstXI site, B) allows de novo telomere formation at the integration site while constructs lacking these repeats integrate randomly in the host genome. Conditions of transfection of the C33A cell line were optimized in order to have a single integration of the transgene per cell. Successful de novo formation of eGFP-tagged telomeres and single integration was confirmed in the polyclonal population of transfected cells and in a set of clones by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) on metaphase spreads (as illustrated in photographs 1, 2 for telomeric insertion and in photographs 3, 4 for internal integration) and by detection of a diffuse hybridization signal in Southern blot (data not shown). In agreement with previous data, the rate of de novo telomere formation in stably transfected cells is very high in the C33A cells reaching 80–90% of the hygromycin resistant cells for the T and T1X constructs. We also confirmed by Multiplex FISH analysis that in the presence of D4Z4, the constructs do not integrate at preferential sites (Ottaviani et al., Submitted). Three days after transfection, Hygromycin B was added to the medium. Then, cells were grown for an extended time in selective medium. The percentage of eGFP-positive cells and the average level of eGFP were monitored by Flow Cytometry (FACS) every 3 days for up to 90 days. B. Kinetics of the expression of eGFP. After 10–12 days, the percentage of eGFP-positive cells decreases in cells containing the T construct that plateaus at 10–20%. A low eGFP expression is also observed in cells carrying a single D4Z4 element at a subtelomeric position (T1X). On the opposite, the level of eGFP is high in C1X cells and remains constant throughout the course of the assays. C. The pCMV and C1X constructs were transfected into C2C12 mouse myoblasts or a human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line (TE671) and the level of eGFP was monitored by FACS for up to 30 days. As previously described for C33A cells, D4Z4 protects the expression of the eGFP from CPE in the different cell types tested indicating that insulation mediated by D4Z4 is not dependent upon the cell type. D. The integrity of each construct was verified by Quantitative PCR from genomic DNA of hygromycin resistant cells using different set of primers. The Ct values obtained for each construct were normalized to the H4 promoter as an internal control and compared to the values obtained for the T construct containing only the resistance gene, eGFP reporter and the telomere seed. Untransfected C33A cells were used as negative control (data not shown). For each primer set, the average fold-increase from 3 independent cell populations (±S.D. shown by error bars) is indicated in representative populations of cells. The eGFP sequence and the 3′ end of the construct can be detected in the different populations while the number of D4Z4 increases in cells transfected with vectors containing multiple copies of the repeats.

(0.7 MB TIF)

D4Z4 does not enhance eGFP expression. In order to test the role of D4Z4 in the control of gene expression, the repeat was cloned upstream of the pCMV promoter driving the eGFP reporter (1XC construct) or upstream of the pCMV promoter driving the HyTK resistance gene (X1C construct) and compared to the pCMV control vector or the C1X construct. When present upstream of the eGFP reporter or the HyTK gene, D4Z4 does not enhance the expression of the reporter indicating that D4Z4 does not act as a transcriptional enhancer in these situations.

(8.3 MB TIF)

CTCF binds to D4Z4 in vitro. To determine whether the candidate CTCF binding sequences (A) are capable of binding to CTCF, gel retardation assays were carried out (B). The mobility was compared to the chicken b globin FII 5′HS4 site. The FII (lane 1) and D4Z4 CTCF site (lane 5) can be supershifted by incubation with a CTCF antibody (star). We also used unlabelled oligonucleotides corresponding to known CTCF binding sites for competition assays. C33A nuclear extracts were incubated either with labeled FII (lanes 1–4) or 468-S labeled oligonucleotides (lanes 5–8) and molar excess of FII (lanes 3, 7) or TAD1 site at the mouse TCRα-Dad1 locus [24] (lanes 4, 8). Molar excess of unlabeled FII or TAD1 can displace the binding of CTCF from the labeled D4Z4 sequence whereas mutant versions of FII cannot (data not shown) suggesting that the sites at position 468–481 and 476–489 of D4Z4 bind CTCF. C. Different primer sets spanning the construct were used to amplify input DNA and DNA fraction immunoprecipitated with antibodies to CTCF by a real-time Q-PCR method. The y-axis shows the fold enrichment of CTCF in the bound fraction versus input chromatin. Each data point indicates the average of at least three independent experiments with the S.D. shown by error bars. A significant enrichment of more than 7-fold was observed with primers encompassing the putative CTCF binding site showing that CTCF interacts with the D4Z4 repeat in vivo (black bars). This enrichment is lost when chromatin immunoprecipitation is performed on cells transfected with siRNA against CTCF (grey bars). D. Schematic representation of D4Z4 with the position of the primers used for ChIP quantification.

(8.3 MB TIF)

Validation of CTCF and A-type Lamins knock-down. A. C1X and pCMV cell populations were transfected with pools of siRNA against CTCF (pool CTCF), 3 different siRNAs (CTCF 1, 2, 3) or negative control siRNA (sineg) and quantification of CTCF and eGFP mRNA was performed by reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR amplification. The values were normalized to the b-Actin standard. The percentage of CTCF or eGFP mRNA for cells treated with CTCF siRNA vs control cells is indicated. B. CTCF is a versatile protein that regulates numerous pathways in human cells. In order to verify that the KD of CTCF does not affect cell viability and subsequently, eGFP level, cell populations were incubated with BrdU 7 days after transfection and cell cycle was analyzed by flow cytometry. No significant difference could be observed in cells transfected with negative control siRNA (mock) compared to CTCF siRNA (CTCF). C. A population of cells stably transfected with the CDE construct were transiently transfected with negative control siRNA (mock) or siRNA against CTCF or A-type Lamins (LMNA). The percentages of eGFP positive cells were determined by FACs three days after transfection. The leftward shift peak in cells transfected with siRNA to CTCF or LMNA indicates that the intensity of the eGFP is decreased in the pool of eGFP positive cells compared to control cells. D. Different cell populations were transfected with pools of siRNA against products of the LMNA gene. Depletion in A and C type lamins was controlled by western blot on whole cell extracts 4 days (1T) or 7 days (1T+3 days) after a first transient transfection or 4 days after a second transfection (2T) and compared to the level of both proteins in mock-treated cells. A goat polyclonal antibody was used for western blot and ChIP experiments. The total amount of protein in each extract was compared by using an anti-actin antibody E. The specificity of the CTCF and Lamins effects on the activity of D4Z4 was compared to the effect of YY1 that was previously reported to bind to D4Z4 [7], USF1 and 2 that participate in the insulator activity of the chicken 5′HS4 insulator [26] and components of the nuclear Lamina, Lamin B or BAF1. Therefore, T1XDE cells were transiently transfected with pools of siRNA against the different genes or negative control siRNA (mock). The % of eGFP positive cells was determined by FACS 3 to 7 days after transfection and we did not observe a significant decrease in eGFP level in the different populations of transfected cells. Similar results were observed for the other constructs harboring insulator activity.

(0.4 MB TIF)

Loss of CTCF binding only slightly increases the trimethylation of H3 K9 residues. Above the threshold of 11 copies, the D4Z4 array is methylated at the DNA level suggesting that long stretches of D4Z4 become more condensed. CTCF might be important in the control of the chromatin structure and we wanted to test if the loss of CTCF binding that we observed upon D4Z4 multimerization is accompanied by an increase in the trimethylation lysine 9 residues on histone H3 tails. Therefore, ChIP was performed with anti-Me3-H3K9 in cells stably transfected with different D4Z4 vectors. Values were normalized to the histone H4 promoter as a standard and enrichments of the immunoprecipitated DNA compared to input DNA are presented (y-axis).

(1.1 MB TIF)

Cohesins do not participate in the D4Z4 insulator activity. Recently, high throughput techniques allowed the identification of numerous binding sites for Cohesins [25],[32],[51] throughout the human genome. Interestingly, many of these sites also correspond to CTCF sites suggesting that the two proteins might be involved in insulation activity. In order to see whether Cohesins also contribute to D4Z4 activity we transfected the T1XΔE cells with siRNA against SCC1 [25] and measured the expression of eGFP 3 to 7 days after transfection. We did not observe a significant difference after transfection of these siRNA suggesting that Cohesins do not contribute to the activity of D4Z4.

(1.1 MB TIF)

Supplementary information.

(0.09 MB DOC)