Abstract

Proteomics holds the promise of evaluating global changes in protein expression and post-translational modification in response to environmental stimuli. However, difficulties in achieving cellular anatomic resolution and extracting specific types of proteins from cells have limited the efficacy of these techniques. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) has provided a solution to the problem of anatomical resolution in tissues. New extraction methodologies have expanded the range of proteins identified in subsequent analyses. This review will examine the application of LCM to proteomic tissue sampling, and subsequent extraction of these samples for differential expression analysis. Statistical and other quantitative issues important for the analysis of the highly complex datasets generated are also reviewed.

Keywords: protein extraction, profiling, 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis, biostatistics, immunofluorescence

1. Introduction

The advances of the genomic revolution have also fueled a burgeoning interest in proteomics, which holds the promise of evaluating global changes in protein expression and function in response to normal or pathological stimuli. However, the far greater complexities of proteomic analyses have hindered the utilization of these techniques. First, while all cells express the same genome, the expressed proteome varies in different cells. Thus, precise anatomical definition and delineation of samples is critical to achieve meaningful results. Also, proteins are not self-replicating templates like DNA, so it is impossible to amplify a protein in vitro using a technique analogous to PCR. Even if one were to amplify mRNA transcripts for each protein, there would be no way of predicting which gene products were expressed under different sets of conditions, and the functionality encoded by post-translational modifications would be completely missed. Therefore, developing methods that extract, separate, detect, and identify a wide range of proteins from small amounts of sample have been of paramount importance.

Many investigators have proposed methods for isolating cells from small, anatomically defined regions. Initially, manual microdissection was attempted. This proved technically difficult and imprecise except in the best of hands. The micropunch dissection technique pioneered by Palkovits represented a major advance [1]. Small areas were punched out of brain tissue samples using a hollow needle. With care in gross dissection and careful attention to anatomical landmarks, precision and reproducibility were improved. However, anatomical relationships were distorted, and resolution was roughly at the level of brain nuclei, not small cell groups. A method for microscope-aided microdissection in the CNS was described by Cuello and colleagues [2]. This method relies on the differential light transmittance of myelinated and unmyelinated tissues in fresh brain slices. Myelination decreases light transmittance, so myelinated tissues appear dark when transilluminated. Unmyelinated tissues appear lighter. This method can provide a surprising degree of anatomical detail and precision, however may not be widely applicable to other tissue types where subregions are not effectively defined by differences in light transmission.

While the techniques developed above can be useful, one limitation they all share is the inability to capture phenotypically defined subsets of cells. Since cells of differing chemical and receptor composition are likely to express different proteomes, as well as respond differently to physiological perturbations, isolating specific subtypes of cells in a region can be of critical importance. Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) is a very powerful way of separating specifically tagged cells [3], but with a total loss of anatomical resolution. This issue is also shared by immunomagnetic separation [4] and micropipet extraction of cellular contents [5].

Over the last several years, LCM has evolved into a practical solution to this conundrum. LCM, invented at the National Institutes of Health (USA) [6], permits the collection of phenotypically defined cells in a precise anatomic context. Subsequent investigations have established the compatibility of this method with downstream protein extraction and arraying technologies. It is now possible to ask highly focused questions using state of the art proteomics technologies.

While it is possible to ask highly specific questions, is it also possible to generate specific, meaningful results? This is dependent on extracting as many proteins as possible from a sample. This step is probably the most critical determinant of experimental success, yet has been given the least amount of attention by current proteomics investigators. The wide range of solubilities and chemical properties of proteins in cells make it difficult to extract all types of proteins with equal efficiency. An additional complicating factor is that investigators wish to study smaller and smaller samples. As sample size decreases, protein diversity will decrease as more proteins fall below the limits of currently available protein identification technologies. Obligate losses of extraction and separation techniques become more of an issue, and there is increased measurement variability when operating so close to detection limits. In spite of these caveats, recent studies have shown that it is possible to obtain useful information from samples as small as single cells [7-9].

The main focus of this review is to describe recent developments and issues in the use and effectiveness of LCM coupled with 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DE), the longest established protein arraying and quantification technology utilized for proteomic analyses. Many investigators have utilized this combination of techniques, and their technical findings will be summarized. Issues that will be addressed include whether LCM affects cellular protein expression patterns, and whether methods of identifying specific cellular subtype interfere with subsequent proteomic analyses. We will also consider the question of how the widest possible range of proteins can be extracted for arraying and quantification. We will also touch upon important experimental design and statistical issues that are of critical importance to fully interpret the complex experimental results generated as well as to avoid the unintentional introduction of bias into these studies. It is our hope that this will provide the reader with an understanding of basic principles and issues so these techniques could be applied to their own experimental questions.

2. Laser Capture Microdissection

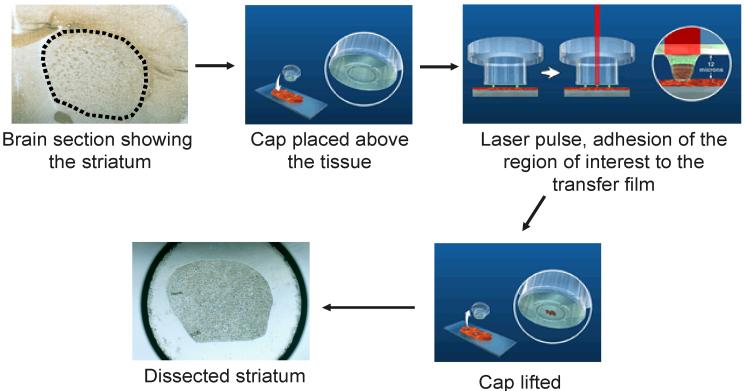

LCM was initially developed at the NIH [6,10]. As initially described, a small infrared laser was aimed at thin, rapidly postfixed tissue sections. A small polymer film attached to a cap overlaying the sample was melted by the heat, and the film adhered to the cells of interest. This process is shown in Figure 1. FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE This development was commercialized, and this type of instrument is now sold by Molecular Devices (www.moleculardevices.com). PALM (www.palm-microlaser.com) developed a competing technology, which used an ultraviolet laser to cut specific tissue areas, then defocused the laser and used the energy generated to “catapult” the tissue upwards to a collector. Leica (www.leica-microsystems.com) modified this concept to use a UV laser to cut tissue attached to the bottom of a slide, which would then drop into a collecting cup. Molecular Machines and Industries (www.molecularmachines.com) uses tissue attached to the bottom of slides, but “sandwiched” above a plastic membrane, which is claimed to minimize the possibility of sample contamination. A typical LCM device is pictured in Figure 2. FIGURE 2 ABOUT HERE These devices are reviewed in more detail in [11-15]. Diverse applications of LCM are reviewed in [16]. Each of the systems can be outfitted with varying degrees of automation, ranging from automatic slide loaders to automatic detection of areas to be dissected by threshold detection of staining intensity. Molecular Devices is also offering an instrument that combines IR laser cell capture with UV laser tissue cutting. Further details can be obtained on the manufacturers' websites listed above.

Figure 1. LCM workflow.

Samples are generally fresh-frozen and sectioned using a cryostat to 5-8 μm thickness. This figures shows a dissection of a brain region known as the striatum. A cap that fits on an eppendorf tube is placed over the sample. A thin film that is melted by the heat of the laser is premounted on the cap. The laser is pulsed over areas of interest, causing the film to melt and cells of interest to adhere to the film. The cap is then lifted from the section, and captured cells subjected to further processing.

Figure 2. An example of a laser capture microscope.

The Arcturus XT is pictured. This instrument is based on the Nikon TE2000U inverted microscope, and has both UV and IR lasers to enable both cutting and adherent LCM. From http://www.moleculardevices.com/pages/instruments/arcturusXT.html

However, before jumping into LCM-based proteomics experiments, there are three important questions to be addressed: First, does the fixation required for microdissection interfere with subsequent proteomic analyses?; Second, does LCM itself interfere with analyses?; and finally, does the tissue staining commonly used for cellular identification and selection affect protein recovery? Fixatives belong to two general classes; precipitating and cross-linking. Cross-linking fixatives generally have little effect on genomic DNA recovery, but have profound effects on RNA [17] and protein [15]. Therefore, precipitating fixatives such as ethanol and methacarn have been preferred for protein work [18,19]. LCM as initially described used rapidly frozen tissue sliced in a cryostat to 5-10 μm thickness, then postfixed in 70% ethanol for 30 sec. This is how we have processed all of our tissue for LCM. Several groups, including our own, have demonstrated that brief ethanol postfixation and LCM using the IR laser method does not adversely affect proteomic profiling by 2DE [20-22]. It has also been shown that paraffin embedding affects proteomic profiling only slightly if tissue is processed properly [18,23]. While the amount of protein lost with paraffin embedding was not detailed, it was still possible to detect differential protein expression in the study by Ahram et al. even though the quality of 2DE was reduced [18]. Several reports have attempted to process crosslinked (formalin fixed) tissues for proteomic studies. The potential advantages of being able to use this approach are enormous, as most pathological tissue specimens are formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections. Recent studies have demonstrated some success in processing such tissues for LC/MS based approaches, western blotting, and 1D electrophoresis [23-26]. A recent study showed that 63% of the peptides identified from a fresh frozen mouse liver sample could be identified using LC-MS/MS after formalin fixation [23]. Detection of differential expression was not assessed. Studies have not yet demonstrated success with 2DE after protein extraction from crosslinked tissues [18]. Intriguing studies have reported the use of the “catapulting” type of LCM on live cells growing in a specially modified culture dish [27-30], although this method does not appear to have developed a wide following. This technique could have tremendous utility for both cell culture and slice preparations.

Tissue staining is used to guide the selection of specific cells or groups of cells during the LCM process. LCM does not permit cover slips on sections, thus some tissues appear extremely dark and ill-defined under the LCM microscope. As a result, higher stain concentrations may be needed to permit visualization over background, and these conditions may not be compatible with 2-DE analysis [31].

One approach to this problem has been to avoid the staining issue entirely, and guide microdissection by staining an adjacent section [22]. This “navigated” approach requires the ability to register the stained image with the unstained sample, but does not lead to substantial protein losses or interfere with subsequent analyses [22,32].

In some cases, staining of the tissue section with stains such as hematoxylin and eosin has been used to guide the dissection process. We have shown that conventional histological staining methods (cresyl violet, hematoxylin/eosin and toluidine blue) and some non-conventional methods (chlorazol black E, Sudan black B) are not compatible with 2-DE-based proteomic analysis of laser-captured brain samples [31]. Similar findings have been observed in other tissues [20,21,33,34]. Hematoxylin alone does not appear to greatly affect proteomic analyses [18,21]. The detrimental effect of histological staining appears to be proportional to the stain concentration and/or incubation time [21,31]. Therefore, depending on the tissue being studied, it may be difficult to adapt histological staining protocols to LCM and 2-DE analysis.

Several groups have investigated the use of immunostaining for sample identification. Initially, fluorescent and enzymatic detection-based immunostaining protocols compatible with LCM were used for mRNA extraction [35,36]. While mRNA recovery appeared to be unaffected by immunostaining, protein expression was not investigated. These protocols also used extremely short incubation times and extremely high antibody titers. Immunogold staining was also evaluated for proteomic analysis of LCM samples [37]. However, this method shares the above drawbacks, needing high antibody titers and short incubation times. This method yielded only 40% protein recovery by weight when compared to unstained, manually dissected samples. We have observed that immunostaining methods based on avidin-biotin complexes and enzymatic detection also give poor protein recovery on 2-DE (L. Moulédous and H. Gutstein, unpublished observations). Therefore, we developed an approach for immunostaining samples using fluorescent secondary antibodies. We achieved 87% protein recovery, as well as using normal antibody titers and incubation times [38]. Visualizing fluorescent dye on a dark background is straightforward and facilitates faster and more effective dissection. The stability of the fluorophores used needs to be taken into consideration when planning dissections to avoid difficulties with photobleaching.

3. Protein Extraction and Separation:

The most sophisticated sample harvesting techniques will have no impact if proteins cannot be extracted from the tissues and the resulting complex protein mixture separated for subsequent quantifications and identifications. As described above, great efforts have been expended to ensure that sample collection methods involving LCM would not interfere with subsequent proteomic analyses. A small but dedicated cadre of investigators has devoted equally robust efforts toward improving protein extractions and separations. Extractions involve both physical and chemical disruption of cells. Most investigators combine mechanical disruption and chemical treatments, as physical cell disruption may improve extraction efficiencies over simple chemical extraction. Extractions have also been categorized in order of increasing severity from “gentle”, which are osmotic, chemical, or enzymatic treatments or to “vigorous”, which are strong physical disruption methods [39].

A wide variety of methods have been employed to physically disrupt cells for protein analysis. Homogenization, ultrasonication, freeze-thawing, pressure cycling, and bead mills have all been employed for protein extraction [40-48]. One method that is effective for a wide range of biological samples is cellular homogenization. There are two basic instrument designs - the blender, which uses freely rotating blades, and the rotor/stator, which uses curved blades on a rotor inside a perforated cylindrical shaft that does not move. Samples are disrupted by mechanical turbulence as well as shearing between rotor and shaft. It is critical that the rotor be properly sized for the specific sample, and that the rotor is capable of a maximum velocity of 10-20 m/sec [43]. Homogenization may not work well for disruption of yeast as well as some microbes.

Ultrasonication is another widely applicable technique. In this method, sonic pressure waves are created that cause bubble formation (“cavitation”) and subsequent collapse, leading to cell lysis. The critical variable is power density at the tip. More power is needed to disrupt high viscosity samples. The addition of small beads can also aid in disruption. Heat generation is a critical concern with ultrasonication, as well as homogenization. Sonicating in short bursts and precise sample temperature control is crucial. Lower temperature also promotes shock front propagation, aiding cell disruption.

Bead mills are also useful for disrupting a large variety of samples. Bead size and composition should be matched to the type of sample being processed [44,47]. The “french press”, where samples are forced through small orifices at high pressures, can also be effective. Temperature control is a concern with this method, as a great deal of heat is generated. Pressure cycling, basically repeated french press cycles in a constant temperature environment, has recently been marketed commercially and warrants further investigation [48]. The old-fashioned “cell bomb” involves saturating the sample with nitrogen at extremely high pressure, forcing more nitrogen gas into the cell. Pressure is suddenly released and nitrogen bubbles are formed, basically giving the sample the “bends” and leading to effective cell disruption. This is the only method that actually cools the sample during disruption due to adiabatic gas expansion. There is no one method of physical disruption that is clearly superior for proteomic studies. The method chosen will depend on the sample being studied and the availability of specific equipment. Direct comparison studies using specific types of samples are needed before more specific recommendations can be made.

Chemical extraction and protein solubilization, the other key element of the protein extraction process, has also improved markedly in the past several years. There are three major goals of this process: first, to minimize interactions between proteins as well as proteins and other substances (e.g., nucleic acids, lipids); second, to remove contaminants and interfering substances; finally to prevent protein precipitation during the separation process [49]. The approaches used depend on (1) whether native conformation or denaturation is required; (2) what types of contaminants need to be removed and (3) the subsequent protein separation methods to be employed. Denaturation improves extraction efficiency by disrupting covalent disulfide bonds and non-covalent interactions, reducing protein-protein interactions. This process destroys secondary and tertiary protein structure and so is not useful for studying protein complexes. The range of extraction solvents used is limited only by the constraints of the subsequent protein separation technology. In general, newer extraction methods involve the use of higher concentrations of chaotropic agents (urea, thiourea) and strong zwitterionic detergents. There are already several excellent reviews available on this subject [49-52]. Various chemical maneuvers can also be performed to lyse cells and aid extractions, such as osmotic shock, membrane solvents, and enzymatic lysis [43,53]. Care must be taken to ensure that the enzymes or solvents used do not modify or destroy proteins of interest. Also, we have observed that modern extraction buffers using strong zwitterionic detergents and chaotropes can inactivate enzymes routinely used in previous protocols.

Once proteins are extracted, the resultant complex mixture needs to be separated for subsequent analysis of abundance and differential expression. Electrophoresis is one of the oldest separation modes [54], and generally employs a gel matrix to assist with the separation [55]. Separating proteins by their isolectric points and then by molecular weight (two-dimensional gel electrophoresis; 2DE) as pioneered by O'Farrell and Klose in the 1970s [56,57] provides the greatest resolution of the electrophoretic methods, capable of resolving hundreds to thousands of individual proteins [58,59]. Traditionally, 2-D analysis has been thought of as a cumbersome, slow, and somewhat variable procedure. However, the introduction of immobilized pH gradient (IPG) technology facilitated reproducibility and sample loading, greatly improving the robustness of this technique [60,61]. Automation of 2-D analysis with robotic instruments has also been reported to improve throughput [62-64]. The amount of starting material needed for 2DE-based proteomic analyses depends on many factors: the starting tissue, fractionation strategy, size of gel being run, staining method, and the robustness of the analytical methods being used. Investigators have loaded anywhere from 10 μg to 1 mg+ of total protein per gel. Using 11 cm IPG strips, we have found that 50 μg of total protein load strikes an ideal balance between protein diversity and time needed to obtain the sample. 50 μg of total protein can easily be microdissected in 2-3 hours.

However, theoretical calculations of protein diversity in complex genomes (based on about 10-15,000 genes expressed in individual cells [65], plus an unknown number of post-translational modifications) is far above the observed resolution of 2DE [66]. Limitations in protein loading capacity and detection sensitivity using standard 2-D gels may also limit the detection of low abundance proteins. Therefore, many investigators employ a variety of methods to reduce sample complexity to help enable more comprehensive detection of a focused subset of the proteome. A commonly suggested first step is fractionation of cells to focus on a specific organelle or region (e.g., mitochondria, synaptosome) of interest [67]. These methods require large amounts of starting material due to losses incurred during fractionation, but are useful when enough tissue is initially available. Another approach to decreasing sample complexity is sequential protein extraction [51,68,69]. For instance, a mild extraction buffer can be used to create an initial fraction, and then stronger detergents and chaotropes can be used to extract less soluble proteins.

Another fractionation strategy commonly combined with 2DE is to reduce the pI range being analyzed by using narrow-range IPG strips [70,71]. This method provides greater resolution of a much smaller subset of the proteome. One potential problem with this approach is the potential for massive protein precipitation due to the presence of proteins outside the pI range of the IPG strip in the sample. This issue has been addressed by Righetti and colleagues with their development of the multi-compartment electrolyzer (MCE) for isoelectric fractionation of complex mixtures [72]. In this method, samples are placed in liquid compartments separated by membranes permeable only to proteins of a specific pI range. Electrophoresis is performed, and proteins migrate in the liquid phase to the appropriate compartment. Sample from each compartment can then be loaded onto IPG strips of the same pI range for 2DE. Reducing the risk of protein precipitation in this manner permits the loading of much higher amounts of total protein and the use of much narrower pI gradients, potentially increasing both resolution and detection of rare proteins.

4. Statistical Considerations

The endpoint of most proteomic studies is the determination of the differences in protein expression between experimental conditions. Generally, proteomics techniques measure differences relative abundance between samples, such as the percent change between the mean relative abundance of a particular spot in two treatment groups. Differences can be quantified either before or after protein identification. The advantage of quantifying before identification (e.g., differences in the intensity of cognate protein spots on 2D gels) is that subsequent protein identification efforts can be focused only on proteins that are differentially expressed. Because proteomic studies are difficult and time consuming, meticulous planning of the experimental design is needed to ensure that systematic bias does not creep into the results. There are analyses illustrating the dangers systematic bias in proteomics studies (see [73-77]). Bias can be avoided by employing standard principles of experimental design, such as blocking and randomization [78]).

Quantification in 2DE experiments usually involves fluorescent and visible stains, as well as radiolabeling. The relationship between spot intensity and protein amount is linear for many of these stains over several orders of magnitude [79,80]. Silver stains do not have as linear of a relationship [81]. Differential in-gel electrophoresis (DIGE) is a method that has been proposed to reduce measurement variability by running both samples from two different treatment groups, and a pooled sample combining the two treatments, on the same gel [82]. There are issues with protein labeling, stain sensitivity and alterations in protein migration that need to be considered in these types of studies. In addition, DIGE limits comparisons to two treatment groups.

Regardless of the protein labeling method, a problematic analytical challenge is detecting protein spots while ignoring artifacts, then matching corresponding spots across multiple gels. If an experiment contains N gels and p protein spots per gel, the analytical goal of this step is to create an N-by-p matrix containing the quantification values for each protein spot on each gel. This matrix can then be analyzed to determine which proteins vary significantly between treatments. Many software packages have been designed in an attempt to automate and objectify spot detection and quantification. Unfortunately, these methods are very labor intensive and error-prone, especially in studies using large numbers of gels (Clark and Gutstein, Proteomics, under review). Errors in spot detection, matching, and boundary determination, are just a sampling of the types of errors that increase the variability of the results, thus reducing the probability of finding statistically significant differences. These problems tend to accumulate with larger studies, which can encourage some investigators to perform smaller studies that are then underpowered for finding realistic-sized differences.

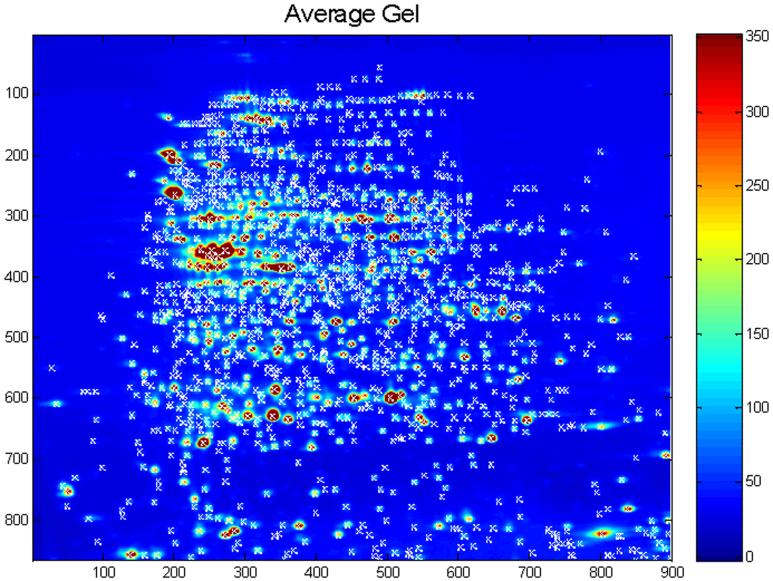

In an attempt to automate and simplify 2DE analysis and reduce measurement error and the introduction of variability, we created a novel approach to preprocessing 2DE data [83]. Unlike current analytical packages, our method quantifies spots by their peak spot intensity values rather than trying to establish and compute spot volumes. The idea is to prevent the introduction of bias and variance that can result from errors in more complex methods. In addition, we align all the gel images and for each pixel value, sum across all gels to create an “average” gel. The advantage of this is that true protein spots will be reinforced while artifacts will be diminished, and noise will be weakened by a factor of . Simulation studies have demonstrated that our method leads to more reliable and precise quantifications [83]. Thus, we can potentially detect and quantify faint spots more reliably, thereby increasing the realized dynamic range of 2DE. A typical average gel is shown in Figure 3. FIGURE 3 ABOUT HERE Similar methods have also been developed to detect and quantify peak values for matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry data [84,85].

Figure 3. Representative Average Gel.

This average gel was created by taking the pixel-wise average over a series of 28 gels previously reported by Nishihara and Champion [116] with feature alignment performed in our laboratory using the TT900 program (Nonlinear Dynamics, Newcastle, UK). “Hotter” colors indicate regions of higher intensity, while “cooler” colors indicate lower intensities. The units of the x and y axes are pixel distance from the origin (upper left corner of the image). White “x's” mark the 1380 spots detected using the Pinnacle method. These represent local maxima in both the x- and y-directions with intensities greater than the 75th percentile intensity on the average gel. Figure from [83].

Once gel images have been preprocessed, and an N×p matrix of relative quantifications generated, the next critical step is to identify which proteins are significantly changed by treatment or disease condition. These significantly regulated proteins may be useful as potential biomarkers. Statistical tests must be used to define significant changes, not simply ad hoc criteria such as a certain fold-change. Appropriately used statistical tests account for measurement variability, while fold-change does not. The test that is appropriate is dependent upon the number of experimental groups and the study design. For instance, if there are two experimental groups, a t-test (or nonparametric rank-sum test if normality cannot be assumed) can be done for each protein spot, then all spots with sufficiently small p-values noted as significant.

The critical question is what is the appropriate p-value cutoff to choose to define statistical significance? Proteomics experiments analyze hundreds to thousands of proteins simultaneously. A number of these spot comparisons will have small p-values even if the differences are not truly significant. For example, for every 1000 protein spots, we would expect about 50 p-values less than 0.05 by random chance alone. This conundrum is known as the multiplicity or multiple testing problem. The classical approach to dealing with this issue is the Bonferroni correction, which uses a cutoff of .05/p to define statistical significance, where p is the number of protein spots. Bonferroni controls the rate of false positives very well but results in a large number of false negatives, so may be too conservative for most proteomic studies. A relatively new concept that has been proposed as a more reasonable way to define significance is to control the false discovery rate (FDR) [86]. Setting the FDR to .05 means that we expect 5% or fewer of the spots declared significantly different to be false positives. A number of procedures have been developed to define FDR [86-97], although a clear method of choice has yet to emerge. Typically, controlling the FDR at .05 leads to p value cutoffs that are less than .05, but much larger than the Bonferroni value of .05/p. Since we still expect that 1 out of every 20 proteins declared significant are false positives, it is important to subsequently validate results with less complex methods, such as Western blotting. Some false positives must be accepted so we have enough power to identify relevant changes.

Prior to undertaking proteomic studies, power calculations should be performed to determine appropriate sample sizes and replicate samples needed for a particular study. Recently, various methods have been developed to perform these calculations when FDR is used to account for multiple comparisons [98-102]. The calculations depend on technical reproducibility and between-subject variability, as well as the desired effect sizes. Preliminary studies should be performed to estimate these parameters prior to undertaking definitive studies. The use of smaller and smaller samples will also affect the statistical properties of proteomic studies. Technical variability is likely to increase, which can reduce statistical power. This can be mitigated by performing larger studies, either using more experimental subjects or more replicates per subject. Studies determining the effects of altering sample size and number of replicates per sample on experimental power have been performed [103].

Another important design consideration is whether or not to pool samples. Pooling samples increases the protein load on each gel, which may reduce technical variability, but it also results in a loss of information about each sample, since it is not possible to correlate protein expression with individual variability. While sometimes necessary in order to obtain enough total protein to produce reliable results, pooling should be avoided whenever possible since it results in a loss of statistical power. When pooling samples, the key sample size factor is the number of pools, not the number of subjects [104]. For example, if for a given experimental condition, we run a total of rg gels on np pools, with each pool containing protein from rs subjects, then given the biological variability σ2b and technical variability σ2t, the standard error for the estimate of the mean protein expression level is (np)-1(σ2brs+σ2t/rg). This standard error is minimized as we maximize the number of pools run. A disastrous design would be to combine all cases into one pool and then all controls into another pool, then to run replicate gels from each pool. If this is done, there is no valid way to perform statistical tests to detect group differences. The variability across replicate gels would only capture technical variability and there would be no way to estimate biological variability. Thus, if pooling is necessary, the maximum number of “pools” should be run to maximize statistical power. Statistical consequences of pooling have been discussed in the context of microarrays [104], and many of these principles apply to proteomic studies.

5. Five Year View

The developmental pace of proteomic technologies promises to increase even more rapidly over the next five years. Further developments and refinements to the various LCM technologies should further facilitate effective sampling of specific cellular phenotypes from tissue in a rapid, automated fashion. One such promising development is expression microdissection [105]. In this method, cells of interest on a section are identified using immunohistochemistry. Ethylene polyvinyl acetate film is then placed on top of the section. The laser energy passes through this film and is preferentially absorbed by the immunostained areas. This melts the film over the regions of interest, permitting selective, high-throughput microdissection [105].

Modifications and improvements to other emerging technologies mentioned in the Introduction should also provide new alternatives for precise cellular sampling in an anatomic context. “Gentle flow” cell sorting is a modification of flow cytometry that permits the sorting of small objects (microorganisms, tissue slices) containing features of interest [13]. New advances in optical tweezer methods should enable the application of this technology to cellular and subcellular sampling in a precise anatomical context [106]. Combination of dielectrophoresis with novel optical technologies also holds promise [107,108], but will require that cells of interest have different electrophoretic properties than all other cells in the sample.

Improvements will also occur in existing extraction and separation techniques [45]. More efficient detergent and chaotrope combinations will undoubtedly be described and new equipment to reduce variability and increase sample throughput developed. Stains of increasing sensitivity should permit deeper analysis of the proteome [34,80]. A resurgence of interest in the greater detection sensitivity afforded by radiolabeling protein samples [109] (initially described in O'Farrell's initial report on 2DE [57]) should also prove useful. However, in addition to these incremental improvements, breakthrough developments in nanotechnology could revolutionize protein extraction and arraying [110,111]. Miniaturization of the extraction process using microfluidic devices holds the promise of more focused, yet deeper proteome coverage from small samples [112]. Recent work has been able to detect specific rare proteins from single cells [113]. Also, the confluence of novel nano-imaging techniques and microfluidic approaches may impact the field in exciting and unanticipated ways [114].

Parallel advances in analytical and statistical methods will also be needed to keep up with technological capabilities. The analysis of all high-dimensional data sets, whether protein or nucleic acid based, are works in progress. Simplification, standardization, and streamlining of analytical processes are needed, and efforts in this area are ongoing [83,115]. Better characterization of the structure of large proteomic datasets should also lead to improved, more powerful analysis methods and statistical designs. These tools should be adaptable to a wide range of technologies, and coupled with ongoing improvements in sampling the proteome, should enable the detection of more true proteomic changes between normal and pathological states.

This is an exciting time to be in the field of proteomics. While the past five years have brought tremendous advances, the next five years look equally promising. New developments should allow us to ask questions we can currently only dream of addressing.

6. Key Issues

LCM permits the sampling of small groups of cells in a precise anatomical context

Tissue processing and fixation conditions are critical for the success of subsequent proteomic analyses

Methods used to identify specific cellular subtypes for LCM need to be compatible with downstream extraction and arraying methods

No single extraction method is superior; rather, extractions need to be tailored to the type and amount of tissue as well as subsequent separation techniques

2DE is a robust and viable method for protein separation

Studies must be carefully designed and controlled to avoid the introduction of bias

P value comparisons are not enough. Multiple comparison corrections must be used.

Future developments should dramatically improve both depth and accuracy of proteomic analyses

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for grant support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, The National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (USA).

The authors are grateful for grant support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grants AA13886 and AA16157 to HBG), The National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant DA18310, Neuroproteomics Center on Cell–Cell Signaling), and the National Cancer Institute (Grant CA107304 to Jeffrey S Morris). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

- 1.Palkovits M, Eskay RL. Distribution and possible origin of β-endorphin and ACTH in discrete brainstem nuclei of rats. Neuropeptides. 1987:123–137. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(87)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuello AC, Carson S. Microdissection of fresh rat brain tissue slices. In: Cuello AC, editor. Brain Microdissection Techniques. John Wiley and Sons; Chichester: 1983. pp. 37–126. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen M, Estevez A, Yin X, et al. A primary culture system for functional analysis of C. elegans neurons and muscle cells. Neuron. 2002:33–4. 503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safarik I, Safarikova M. Use of magnetic techniques for the isolation of cells. Journal of Chromatography B, Biomedical Sciences & Applications. 1999;722(12):33–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eberwine J, Yeh H, Miyashiro K, et al. Analysis of gene expression in single live neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3010–3014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emmert-Buck MR, Bonner RF, Smith PD, et al. Laser capture microdissection. Science. 1996;274(5289):998–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hummon AB, Amare A, Sweedler JV. Discovering new invertebrate neuropeptides using mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25(1):77–98. doi: 10.1002/mas.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubakhin SS, Churchill JD, Greenough WT, Sweedler JV. Profiling signaling peptides in single mammalian cells using mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2006;78(20):7267–7272. doi: 10.1021/ac0607010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubakhin SS, Greenough WT, Sweedler JV. Spatial profiling with MALDI MS: distribution of neuropeptides within single neurons. Anal Chem. 2003;75(20):5374–5380. doi: 10.1021/ac034498+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonner RF, Emmert-Buck M, Cole K, et al. Laser capture microdissection: molecular analysis of tissue. Science. 1997;278(5342):1481, 1483. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ball HJ, Hunt NH. Needle in a haystack: Microdissecting the proteome of a tissue. Amino Acids. 2004;27(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00726-004-0104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornea A, Mungenast A. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 2002. Comparison of current equipment; pp. 3–12. [1] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **13.Eisenstein M. Cell sorting: Divide and conquer. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1179–1185. doi: 10.1038/4411179a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A succinct and current review of many emerging cell separation and detection technologies

- 14.Eltoum IA, Siegal GP, Frost AR. Microdissection of histologic sections: past, present, and future. Advances in anatomic pathology. 2002;9(5):316–322. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rekhter MD, Chen J. Molecular analysis of complex tissues is facilitated by laser capture microdissection: Critical role of upstream tissue processing. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2001;35(1):103–113. doi: 10.1385/CBB:35:1:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *16.Conn PM, editor. Laser Capture Microscopy and Microdissection. Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- A useful, slightly dated book covering many aspects of LCM

- 17.Goldsworthy SM, Stockton PS, Trempus CS, Foley JF, Maronpot RR. Effects of fixation on RNA extraction and amplification from laser capture microdissected tissue. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 1999;25(2):86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahram M, Flaig MJ, Gillespie JW, et al. Evaluation of ethanol-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues for proteomic applications. Proteomics. 2003;3(4):413–421. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200390056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shibutani M, Uneyama C, Miyazaki K, Toyoda K, Hirose M. Methacarn Fixation: A Novel Tool for Analysis of Gene Expressions in Paraffin-Embedded Tissue Specimens. Lab Invest. 2000;80(2):199–208. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *20.Banks RE, Dunn MJ, Forbes MA, et al. The potential use of laser capture microdissection to selectively obtain distinct populations of cells for proteomic analysis - Preliminary findings. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(45):689–700. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990101)20:4/5<689::AID-ELPS689>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The initial description of the application of LCM to proteomic studies

- 21.Craven RA, Totty N, Harnden P, Selby PJ, Banks RE. Laser capture microdissection and two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis: evaluation of tissue preparation and sample limitations. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(3):815–822. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64904-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.Moulédous L, Hunt S, Harcourt R, Harry J, Williams K, Gutstein H. Navigated laser capture microdissection as an alternative to direct histological staining for proteomic analysis of brain samples. Proteomics. 2003;3(May):610–615. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demonstration that fixiation and LCM have no significant effect on 2DE

- 23.Hood BL, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD. Unravelling the proteome of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Briefings in Functional Genomics and Proteomics. 2006;5(2):169–175. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/ell017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker KF, Schott C, Hipp S, et al. Quantitative protein analysis from formalin-fixed tissues: implications for translational clinical research and nanoscale molecular diagnosis. The Journal of Pathology. 2007;211(3):370–378. doi: 10.1002/path.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeda K, Monden T, Kanoh T, et al. Extraction and Analysis of Diagnostically Useful Proteins from Formalin-fixed, Paraffin-embedded Tissue Sections. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1998;46(3):397–404. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi S-R, Liu C, Balgley BM, Lee C, Taylor CR. Protein Extraction from Formalin-fixed, Paraffin-embedded Tissue Sections: Quality Evaluation by Mass Spectrometry. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2006;54(6):739–743. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5B6851.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langer S, Geigl JB, Ehnle S, Gangnus R, Speicher MR. Live cell catapulting and recultivation does not change the karyotype of HCT116 tumor cells. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2005;161(2):174–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer A, Stich M, Brocksch D, Schutze K, Lahr G. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; 2002. Going in vivo with laser microdissection; pp. 25–33. [3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stich M, Thalhammer S, Burgemeister R, et al. Live cell catapulting and recultivation. Pathology Research and Practice. 2003;199(6):405–409. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogel A, Horneffer V, Lorenz K, Linz N, Hu?ttmann G, Gebert A. Principles of Laser Microdissection and Catapulting of Histologic Specimens and Live Cells. Methods in Cell Biology. 2007:153–205. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)82005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moulédous L, Hunt S, Harcourt R, Harry J, Williams KL, Gutstein HB. Lack of compatibility of histological staining methods with proteomic analysis of laser-capture microdissected brain samples. Journal of Biomolecular Techniques. 2002;13:258–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong MH, Saam JR, Stappenbeck TS, Rexer CH, Gordon JI. Genetic mosaic analysis based on cre recombinase and navigated laser capture microdissection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(23):12601–12606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230237997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craven R, Banks R. Laser capture microdissection and proteomics: Possibilities and limitation. Proteomics. 2001;1:1200–1204. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200110)1:10<1200::AID-PROT1200>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sitek B, Luttges J, Marcus K, et al. Application of fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis saturation labelling for the analysis of microdissected precursor lesions of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proteomics. 2005;5(10):2665–2679. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fend F, Emmert-Buck MR, Chuaqui R, et al. Immuno-LCM: Laser capture microdissection of immunostained frozen sections for mRNA analysis. American Journal of Pathology. 1999;154(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65251-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murakami H, Liotta L, Star R. IF-LCM: laser capture microdissection of immunofluorescently defined cells for mRNA analysis. Kidney International. 2000;58(3):1346–1353. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Craven RA, Totty N, Harnden P, Selby PJ, Banks RE. Laser capture microdissection and 2D polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis: evaluation of tissue preparation and sample limitations. American Journal of Pathology. 2002;160(3):815–822. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64904-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *38.Moulédous L, Hunt S, Harcourt R, Harry J, Williams K, Gutstein H. Proteomic analysis of immunostained, laser-capture microdissected samples. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:296–302. doi: 10.1002/elps.200390026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A protocol for cell subtype detection without significant protein losses

- **39.Scopes RK. In: Protein Purification: Principles and Practice. Cantor CR, editor. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- The “bible” of protein purification

- 40.Belo I, Santos JA, Cabral JM, Mota M. Optimization study of Escherichia coli TB1 cell disruption for cytochrome b5 recovery in a small-scale bead mill. Biotechnology Progress. 1996;12(2):201–204. doi: 10.1021/bp950085l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butt RH, Coorssen JR. Pre-extraction Sample Handling by Automated Frozen Disruption Significantly Improves Subsequent Proteomic Analyses. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5(2):437–448. doi: 10.1021/pr0503634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flanagan RJ, Morgan PE, Spencer EP, Whelpton R. Micro-extraction techniques in analytical toxicology: short review. Biomedical Chromatography. 2006;20(67):530–538. doi: 10.1002/bmc.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **43.Hopkins TR. Physical and chemical cell disruption for the recovery of intracellular proteins. Bioprocess Technology. 1991;12:57–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A well written review explaining the basic types of cellular disruption and their mechanisms, with many classical references,

- 44.Melendres AV, Honda H, Shiragami N, Unno H. A kinetic analysis of cell disruption by bead mill. The influence of bead loading, bead size and agitator speed. Bioseparation. 1991;2(4):231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *45.Raynie DE. Modern extraction techniques. Analytical chemistry. 2004;76(16):4659–4664. doi: 10.1021/ac040117w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A wide ranging review of extraction techniques, including those not currently used in proteomic studies

- 46.Schutte H, Kula MR. Pilot- and process-scale techniques for cell disruption. Biotechnology & Applied Biochemistry. 1990;12(6):599–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schutte H, Kula MR. Separation processes in biotechnology. Bead mill disruption. Bioprocess Technology. 1990;9:107–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smejkal GB, Robinson MH, Lawrence NP, Tao F, Saravis CA, Schumacher RT. Increased protein yields from Escherichia coli using pressure-cycling technology. Journal of Biomolecular Techniques: JBT. 2006;17(2):173–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **49.Rabilloud T. Solubilization of proteins for electrophoretic analyses. Electrophoresis. 1996;17(5):813–829. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150170503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A seminal and comprehensive review of protein extraction and solubilization

- 50.Deutscher MP. Maintaining protein stability. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herbert B. Advances in protein solubilsation for two-dimensional electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:660–663. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990101)20:4/5<660::AID-ELPS660>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santoni V, Rabilloud T, Doumas P, et al. Solubilization of proteins in 2-D electrophoresis. An outline. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;112:9–19. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-584-7:9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asenjo JA, Andrews BA. Enzymatic cell lysis for product release. Bioprocess Technology. 1990:143–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tiselius A. A new apparatus for electrophoretic analysis of colloidal mixtures. Transactions of the Faraday Society. 1937;33:524–531. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andrews AT. Electrophoresis : Theory, Techniques, and Biochemical and Clinical Applications [Second Edition] Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- **56.Klose J. Protein mapping by combined isoelectric focusing and electrophoresis of mouse tissues. A novel approach to testing for induced point mutations in mammals. Humangenetik. 1975;26(3):231–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00281458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **57.O'Farrell PH. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975;250(10):4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The initial descriptions of 2DE. Well worth reading

- 58.Wheeler CH, Berry SL, Wilkins MR, et al. Characterisation of proteins from two-dimensional electrophoresis gels by matrix-assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry and amino acid compositional analysis. Electrophoresis. 1996;17(3):580–587. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150170329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harper S, Mozdanowski J, Speicher D. Two dimensional gel electrophoresis. In: Coligan J, Dunn B, Ploegh, Speicher D, Wingfield P, editors. Current Protocols in Protein Science. John Wiley and Sons; Philadelphia: 1998. pp. 10.14.11–10.14.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blomberg A, Blomberg L, Norbeck J. Interlaboratory reproducibility of yeast protein patters analyzed by immobilized pH gradient two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 1995;16:1935–1945. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501601320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan JX, Sanchez JC, Rouge V, Williams KL, Hochstrasser DF. Modified immobilized pH gradient gel strip equilibration procedure in SWISS-2DPAGE protocols. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(45):723–726. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990101)20:4/5<723::AID-ELPS723>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilkins MR, Gasteiger E, Gooley AA, et al. High-throughput mass spectrometric discovery of protein post-translational modifications. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1999;289(3):645–657. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Williams KL. Genomes and proteomes: towards a multidimensional view of biology. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(45):678–688. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990101)20:4/5<678::AID-ELPS678>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walsh BJ, Molloy MP, Williams KL. The Australian Proteome Analysis Facility (APAF): assembling large scale proteomics through integration and automation. Electrophoresis. 1998;19(11):1883–1890. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150191106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hastie ND, Bishop JO. The expression of three abundance classes of messenger RNA in mouse tissues. Cell. 1976;9(4 PT 2):761–774. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anderson L. From genome to proteome: Looking at a cell's proteins. Science. 1995;270(20 October):369–371. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *67.Pasquali C, Fialka I, Huber LA. Subcellular fractionation, electromigration analysis and mapping of organelles. Journal of Chromatography B. 1999;722:89–102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A review of classical subcellular fractionation techniques

- 68.Jarrold B, DeMuth J, Greis K, Burt T, Wang F. An effective skeletal muscle prefractionation method to remove skeletal proteins for optimized two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:2269–2278. doi: 10.1002/elps.200410367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Molloy MP, Herbert BR, Walsh BJ, et al. Extraction of membrane proteins by differential solubilization for separation using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:837–844. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gorg A, Obermaier C, Boguth G, et al. The current state of two-dimensional electrophoresis with immobilized pH gradients. Electrophoresis. 2000;21(6):1037–1053. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000401)21:6<1037::AID-ELPS1037>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *71.Gorg A, Weiss W, Dunn MJ. Current two-dimensional electrophoresis technology for proteomics. Proteomics. 2004;4:3665–3685. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A well written overview of recent improvements in 2DE

- 72.Herbert B, Righetti PG. A turning point in proteome analysis: Sample prefractionation via multi-compartment electrolyzers with isoelectric membranes. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:3639–3648. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200011)21:17<3639::AID-ELPS3639>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baggerly KA, Edmonson SR, Morris JS, Coombes KR. High-resolution serum proteomic patterns for ovarian cancer detection. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004;11(4):583–584. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00868. author reply 585-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baggerly KA, Morris JS, Coombes KR. Reproducibility of SELDI-TOF protein patterns in serum: comparing datasets from different experiments. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(5):777–785. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baggerly KA, Morris JS, Edmonson SR, Coombes KR. Signal in noise: evaluating reported reproducibility of serum proteomic tests for ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(4):307–309. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baggerly KA, Coombes KR, Morris JS. Are the NCI/FDA Ovarian Proteomic Data Biased? A Reply to Producers and Consumers. Cancer Informatics. 2005;1(1):9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **77.Hu J, Coombes KR, Morris JS, Baggerly KA. The importance of experimental design in proteomic mass spectrometry experiments: some cautionary tales. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2005;3(4):322–331. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/3.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilling tales that should be read by everyone in the field

- 78.Box GEP, Hunter WG, Hunter JS. Statistics for Experimenters: An Introduction to Design, Data Analysis, and Model Building. 2nd ed. Wiley; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patton WF. A thousand points of light: the application of fluorescence detection technologies to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and proteomics. Electrophoresis. 2000;21(6):1123–1144. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000401)21:6<1123::AID-ELPS1123>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *80.Patton WF. Detection technologies in proteome analysis. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;771(12):3–31. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive review of protein detection methods by one of the giants in the field

- 81.Merril CR. Gel-staining techniques. Methods in Enzymology. 1990;182:477–488. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Friedman DB. Quantitative proteomics for two-dimensional gels using difference gel electrophoresis. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;367:219–240. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-275-0:219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *83.Morris JS, Clark BN, Gutstein HB. A Fast, Automatic and Accurate Method for Detecting and Quantifying Protein Spots in 2-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis Data. Bioinformatics. 2007 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm590. under revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A novel approach to gel analysis that greatly simplifies the process

- 84.Coombes KR, Tsavachidis S, Morris JS, Baggerly KA, Hung MC, Kuerer HM. Improved peak detection and quantification of mass spectrometry data acquired from surface-enhanced laser desorption and ionization by denoising spectra with the undecimated discrete wavelet transform. Proteomics. 2005;5(16):4107–4117. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Morris JS, Coombes KR, Koomen J, Baggerly KA, Kobayashi R. Feature extraction and quantification for mass spectrometry in biomedical applications using the mean spectrum. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):1764–1775. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *86.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B: Methodological. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- One of the initial descriptions of FDR

- 87.Benjamini Y, Liu W. A step-down multiple hypotheses testing procedure that controls the false discovery rate under independence. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 1999;82:163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Datta S, Datta S. Empirical Bayes screening of many p-values with applications to microarray studies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):1987–1994. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Efron B. Large-scale simultaneous hypothesis testing: The choice of a null hypothesis. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2004;99:96–104. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Genovese C, Wasserman L. Operating characteristics and extensions of the false discovery rate procedure. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B: Statistical Methodology. 2002;64:499–517. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ishwaran H, Rao JS. Detecting differentially expressed genes in microarrays using Bayesian model selection. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2003;98:438–455. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Newton MA, Noueiry A, Sarkar D, Ahlquist P. Detecting differential gene expression with a semiparametric hierarchical mixture method. Biostatistics. 2004;5(2):155–176. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/5.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pounds S, Cheng C. Improving false discovery rate estimation. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(11):1737–1745. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pounds S, Morris SW. Estimating the occurrence of false positives and false negatives in microarray studies by approximating and partitioning the empirical distribution of p-values. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(10):1236–1242. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Storey JD. A direct approach to false discovery rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B: Statistical Methodology. 2002;64:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Storey JD. The positive false discovery rate: A Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. The Annals of Statistics. 2003;31:2013–2035. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yekutieli D, Benjamini Y. Resampling-based false discovery rate controlling multiple test procedures for correlated test statistics. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 1999;82:171–196. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hu J, Zou F, Wright FA. Practical FDR-based sample size calculations in microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 21(15)(2005):3264–3272. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jung SH. Sample size for FDR-control in microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(14):3097–3104. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li SS, Bigler J, Lampe JW, Potter JD, Feng Z. FDR-controlling testing procedures and sample size determination for microarrays. Stat Med. 2005;24(15):2267–2280. doi: 10.1002/sim.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu P, Hwang JT. Quick calculation for sample size while controlling false discovery rate with application to microarray analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(6):739–746. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pounds S, Cheng C. Sample size determination for the false discovery rate. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(23):4263–4271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **103.Hunt SMN, Thomas MR, Sebastian LT, et al. Optimal replication and the importance of experimental design for gel-based quantitative proteomics. Journal of Proteome Research. 2005;4(3):809–819. doi: 10.1021/pr049758y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An important investigation of the relative importance of group size vs. technical replicates on the power to detect significant differences

- **104.Kendziorski C, Irizarry RA, Chen KS, Haag JD, Gould MN. On the utility of pooling biological samples in microarray experiments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(12):4252–4257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500607102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A seminal paper detailing the benefits and pitfalls of sample pooling

- **105.Tangrea MA, Chuaqui RF, Gillespie JW, et al. Expression Microdissection: Operator-Independent Retrieval of Cells for Molecular Profiling. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology. 2004;13(4):207–212. doi: 10.1097/01.pdm.0000135964.31459.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An exciting advance that could enable high-throughput LCM

- *106.Grier DG. A revolution in optical manipulation. Nature. 2003;424:810–816. doi: 10.1038/nature01935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A well-written and relatively recent review on optical technologies for cellular manipulation

- 107.Chiou PY, Ohta AT, Wu MC. Massively parallel manipulation of images and microparticles using optical images. Nature. 2005;436:370–372. doi: 10.1038/nature03831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hu X, Bessette PH, Qian J, Meinhart CD, Daugherty PS, Soh HT. Marker-specific sorting of rare cells using dielectrophoresis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(44):15757–15761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507719102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Neubauer H, Clare SE, Kurek R, et al. Breast cancer proteomics by laser capture microdissection, sample pooling, 54-cm IPG IEF, and differential iodine radioisotope detection. Electrophoresis. 2006;27(9):1840–1852. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cai L, Friedman N, Xie XS. Stochastic protein expression in individual cells at the single molecule level. Nature. 2006;440:358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature04599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ivanov YD, Govorun VM, Bykov VB, Archakov AI. Nanotechnologies in proteomics. Proteomics. 2006;6:1399–1414. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200402087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **112.Hong JW, Quake SR. Integrated nanoliter systems. Nature Biotechnology. 2003;21(10):1179–1183. doi: 10.1038/nbt871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A well-written introduction to the world of microfluidics by one of the leaders of the field

- 113.Huang B, Wu H, Bhaya D, et al. Counting low-copy number proteins in a single cell. Science. 2007;315:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1133992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *114.Psaltis D, Quake SR, Yang C. Developing opticofluidic technology through the fusion of microfluidics and optics. Nature. 2006;442:381–386. doi: 10.1038/nature05060. More exciting possibilities generated by synergistically exploiting the strengths of two emerging technologies. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **115.Dowsey AW, Dunn MJ, Yang GZ. ProteomeGRID: Towards a highthroughput proteomics pipeline through opportunistic cluster image computing for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Proteomics. 2004;4(12):3800–3812. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A promising technique to help objectively and rapidly analyze large 2D gel series

- 116.Nishihara JC, Champion KM. Quantitative evaluation of proteins in one- and two-dimensional polyacrylamide gels using a fluorescent stain. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:2203–2215. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200207)23:14<2203::AID-ELPS2203>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]