Abstract

Calcineurin inhibitors are potent inhibitors of T-cell-receptor mediated activation of the adaptive immune system. The effects of this class of drug on the innate immune response system are not known. Keratinocytes are essential to innate immunity in skin and rely on toll-like receptors (TLRs) and antimicrobial peptides to appropriately recognize and respond to injury or microbes. In this study we examined the response of cultured human keratinocytes to pimecrolimus. We observed that pimecrolimus enhances distinct expression of cathelicidin, CD14, and human β-defensin-2 and β-defensin-3 in response to TLR2/6 ligands. Some of these responses were further enhanced by 1,25 vitamin D3. Pimecrolimus also increased the functional capacity of keratinocytes to inhibit growth of Staphylococcus aureusand decreased TLR2/6-induced expression of IL-10 and IL-1β. Furthermore, pimecrolimus inhibited nuclear translocation of NFAT and NF-κB in keratinocytes. These observations uncover a previously unreported function for pimecrolimus in cutaneous innate host defense.

INTRODUCTION

Topical immunomodulators, such as the macrolactam ascomycin pimecrolimus, are effectively used for treating atopic dermatitis and other inflammatory skin diseases (Grassberger et al., 2004; Novak et al., 2005; Stuetz et al., 2006). These drugs bind to immunophilins, inhibit the serine/threonine phosphatase calcineurin, and subsequently prevent nuclear translocation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT). As a consequence of the inhibition of NFAT, the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines is suppressed in T cells (Dumont, 2000). It is this inhibitory action on the function of T cells that has been presumed to explain clinical effectiveness. Recent advances in the understanding of the innate immune functions of the skin have opened new avenues to further study the mechanism(s) of action of calcineurin inhibitors on the physicochemical and immunological barrier function of the epidermis. The effects of pimecrolimus on keratinocyte driven innate immune responses constitute an area of interest.

Immunophilins, calcineurin, and NFAT are also expressed in the cells of the innate immune system, including epidermal keratinocytes (Al-Daraji et al., 2002), but their function is incompletely understood. An important innate immune function of keratinocytes is their capacity to provide a chemical barrier against infection by production of peptides with antimicrobial activity. All epithelial and many non-epithelial cells produce these antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). In keratinocytes, AMPs such as cathelicidins and β-defensins have been studied most extensively as effectors of innate immune protection (Frohm et al., 1997; Turner et al., 1998; Agerberth et al., 2000; Di Nardo et al., 2003; Zanetti, 2005). Cathelicidins and human β-defensins (HBDs) have broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and additional immunomodulatory functions. The clinical importance of AMPs has been made evident from studies showing that they are essential in inflammatory processes such as infection, wound healing, psoriasis, and rosacea (Ong et al., 2002; Heilborn et al., 2003; Schauber et al., 2007; Yamasaki et al., 2007). Deficiency of AMPs is observed in patients with atopic dermatitis and Kostmann syndrome, and this lack of appropriate AMP production leads to bacterial and viral superinfections (Ong et al., 2002; Pütsep et al., 2002).

Superinfections seen in atopic dermatitis patients are frequently caused by Staphylococcus aureus (Leung et al., 2004), a Gram-positive bacterium that activates the Toll-like receptor-2(TLR2)-signaling pathway. TLR activation has been demonstrated to induce innate immune response in epidermal keratinocytes and can be potent stimuli of cytokine release and HBD production, but stimulate cathelicidin expression only weakly (Kumar et al., 2006; Schauber et al., 2006; Sumikawa et al., 2006; Schlee et al., 2007). In human keratinocytes, optimal cathelicidin expression requires activity of 1,25-(OH)2 vitamin D3 (1,25D3) (Wang et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2006; Schauber et al., 2007).

Recent studies attempting to understand better the elements that control innate immune functions such as AMP production have shown that innate and adaptive immune responses are controlled by distinct, and sometimes contrasting, mechanisms. We also know now that many cell types express NFAT and, therefore, may also be targeted by calcineurin inhibitors (Ho et al., 1994; Aramburu et al., 1995; Monticelli et al., 2004; Goodridge et al., 2007). For example, recent findings reported that calcineurin inhibition had unexpected effects on natural killer cells, showing that calcineurin inhibition enhances, rather than suppressing, cytotoxic natural killer cell function (Wang et al., 2007). Therefore, on the basis of the complex, and incompletely understood, mechanism for regulation of AMP expression, we investigated the effects of pimecrolimus on AMP expression and function, expression of TLRs, and cytokine production by human keratinocytes. To our knowledge, it is previously unreported that pimecrolimus can amplify innate immune functions of keratinocytes by affecting distinct AMP expression and pathogen recognition in the presence of TLR ligands and/or 1,25D3. Our observations uncover previously unknown functions for pimecrolimus in cutaneous innate host defense and further highlight the complexity of the innate and adaptive immunoregulatory systems in the skin.

RESULTS

Pimecrolimus enhances antimicrobial peptide expression in human keratinocytes

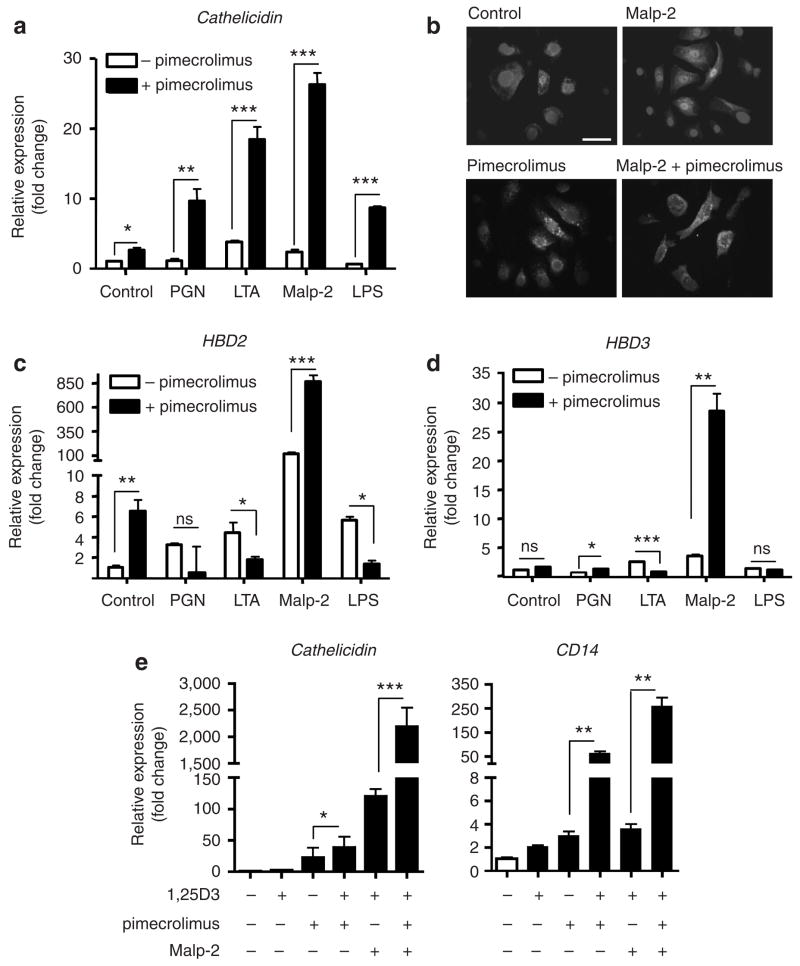

Calcineurin inhibitors such as pimecrolimus suppress multiple components associated with the immune function of leukocytes, but it is unknown whether this also inhibits the innate immune responses of epithelia, such as expression of AMPs or signaling by TLRs. To test whether pimecrolimus influences AMP production following TLR activation, NHEKs were stimulated with TLR ligands in the presence or absence of pimecrolimus. Normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) incubated with TLR2 and TLR4 responded with an increase in cathelicidin mRNA in response to pimecrolimus (Figure 1a). The combination of Malp-2 (a selective TLR2/6 ligand) and pimecrolimus induced strongest expression of cathelicidin among all TLR ligands tested. The increase in cathelicidin mRNA induced by Malp-2 and pimecrolimus was accompanied by an increase in the expression of cathelicidin protein as determined by immunfluorescence (Figure 1b). Other microbial products that can stimulate NHEK, such as poly-I:C (TLR3 ligand), staphylococcal enterotoxin B, or staphylococcus protein A, did not change cathelicidin gene expression of NHEKs with or without the presence of pimecrolimus (data not shown).

Figure 1. Pimecrolimus enhances antimicrobial peptide and CD14 expression in human keratinocytes.

Expression of mRNA for (a) cathelicidin, (c) HBD2, and (d) HBD3 was evaluated in NHEKs that were stimulated with TLR ligands in the presence or absence of pimecrolimus (10 nM) for 24 hours. Peptidoglycan (1 μgml−1), lipoteichoic acid (10 μgml−1), Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1), or lipopolysaccahride (0.1 μgml−1) were used for selective TLR activation. (b) Protein expression of cathelicidin was evaluated in NHEKs grown on chamber slides. Cells were stimulated with the vehicle (control), Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1), pimecrolimus (10 nM), or their combination. Cells were stained with anti-LL-37 antibody and nuclei were detected with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Bar=50 μm (a, c, d, e). (e) Expression of mRNA for cathelicidin or CD14 in presence of low dose 1,25OH vitamin D (1 nM) combined with pimecrolimus (10 nM) and/or Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1). mRNA abundance was evaluated by real-time qPCR and was normalized to that of vehicle-treated controls. Data are means of triplicates (+SD) from a single experiment representative of at least two. Significances were calculated by unpaired Student’s t-test, with *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001.

To test whether other antimicrobial peptides produced by NHEKs were also affected by pimecrolimus treatment, HBD2 and HBD3 mRNA expression was analysed. Pimecrolimus in combination with the TLR2/6 ligand Malp-2 significantly enhanced HBD2 expression, whereas addition of pimecrolimus downregulated lipoteichoic acid- and lipopolysaccharide-induced HBD2 gene expression (Figure 1c). Pimecrolimus also increased HBD3 expression in the presence of peptidoglycan and Malp-2, whereas presence of pimecrolimus slightly, but significantly, downregulated lipoteichoic acid-induced expression of this AMP. Thus, results shown here demonstrate that pimecrolimus affects distinct TLR responses and results in different AMP innate immune responses in keratinocytes.

Pimecrolimus increases TLR and CD14 expression in human keratinocytes

Of the compounds tested, TLR2/6 ligands were seen to induce the greatest increase of AMPs in NHEKs treated with pimecrolimus. The expression of TLR2, CD14 (a TLR2 and TLR4 co-recognition molecule; Jiang et al., 2005), and cathelicidin has also been found to be enhanced by 1,25D3 (Wang et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2006; Schauber et al., 2007). Analysis of cathelicidin and CD14 showed pimecrolimus enhanced the 1,25D3 induction of these genes (Figure 1e). Therefore, we explored next the effects of pimecrolimus on the expression of selective TLRs in keratinocytes and included 1,25D3 as a stimulus. NHEKs were treated with pimecrolimus (10 nM) and 1,25D3 (1 nM), and transcript abundance of TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, and CD14 was analyzed by reverse transcriptase–PCR (qPCR). Treatment of NHEKs with pimecrolimus alone resulted in a significant increase in TLR6 and CD14 as compared with that in vehicle-treated controls. Combination of 1,25D3 and pimecrolimus significantly increased TLR2 and resulted in pronounced upregulation of CD14. The increase in CD14 mRNA abundance by 1,25D3 and pimecrolimus was accompanied by an increase in CD14 protein expression as determined by western blot analysis (Figure 2b and c).

Figure 2. Pimecrolimus enhances TLR and CD14 expression in keratinocytes.

NHEKs were stimulated with vehicle control, low-dose 1,25D3 (1 nM), pimecrolimus (10 nM), or the combination of 1,25D3 and pimecrolimus for 24 hours. (a) Gene expression of TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, and the TLR cofactor CD14 was analyzed by real-time qPCR. (b) Western blotting of CD14 protein expression (upper blot) in NHEKs stimulated with vehicle (lane 1), 1,25D3 (1 nM, lane 2), pimecrolimus (10 nM, lane 3), or the combination of 1,25D3 and pimecrolimus (lane 4) for 24 hours. Membranes were reprobed for loading control with an anti-α-tubulin antibody (lower blot). (c) Protein abundance of CD14 seen in western blot was quantified by densitometry. (d) Pimecrolimus enhanced cathelicidin and CD14 gene expression in the presence of low-dose 1,25D3 (1 nM) or the combination of 1,25D3 and the TLR2, TLR6 ligand Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1) for 24 hours. Significances were calculated by unpaired Student’s t-test, with *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001. ND, not detectable.

To further explore the significance of the increased responsiveness to TLR2 stimulation, and amplify the response, cathelicidin and CD14 expression was examined in the presence of pimecrolimus in combination with 1,25D3 and/or Malp-2 (Figure 2d). Pimecrolimus (10 nM) increased cathelicidin expression approximately 40-fold in the presence of 1,25D3 (1 nM), and this was further enhanced when combinations of 1,25D3 and Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1) were used. Similar results were observed for CD14 expression and showed an approximately 100-fold increase in the presence of 1,25D3 and pimecrolimus (Figure 2d).

Pimecrolimus enhances 1,25D3-induced cathelicidin mRNA in a dose-dependent manner

To examine the dose responsiveness of NHEKs to pimecrolimus, cells were stimulated with a low dose of 1,25D3 (1 nM) in the presence of a wide range of concentrations of pimecrolimus. Cathelicidin and CD14 expression increased in a dose-dependent manner, with maximum response in the range of 1 to 50 nM pimecrolimus (Figure 3a and b). Doses below or above this range had lesser effect. To determine whether pimecrolimus induced cell cytotoxicity, cell death was determined by lactate dehydrogenase release and annexin V/propidium iodide staining. Pimecrolimus did not induce cell cytotoxicty as evaluated by either assay (data not shown). Other calcineurin inhibitors, including FK506 and cyclosporin, also induced a dose-dependent increase in the expression of cathelicidin when stimulated by 1,25D3. Here, the maximal inducing effect on cathelicidin gene expression was found between 0.1 and 1 nM for FK506, and between 10 and 50 pg ml−1 for cyclosporine A (Figure 3c and d). Thus, the results presented here suggest that immunophillin binding drugs stimulate the innate immune AMP response of keratinocytes in a dose-dependent manner. This enhancing effect on the innate immune response was unexpected given the well-established immunosuppresive action of these molecules on adaptive immune responses.

Figure 3. Dose-dependent effect of pimecrolimus, FK506, and cyclosporin A on cathelicidin and CD14 expression in keratinocytes.

(a, b) Cathelicidin and CD14 expression was evaluated in NHEKs that were stimulated with increasing concentrations of pimecrolimus in the presence or absence of 1,25D3 (1nM) for 24 hours. Cathelicidin transcript levels were also evaluated in NHEKstreated with two other calcineurin inhibitors, FK506 (c) and cyclosporin A (d). mRNA abundance was evaluated by real-time qPCR and was normalized to that of vehicle-treated controls. Data are means of triplicates (+SD) from a single experiment representative of two independent experiments.

Differential effects of pimecrolimus on Malp-2-induced cytokine expression from human keratinocytes

Since much of the prior characterization of the immunosuppressive effects of immunophilin-binding or calcineur-ininhibiting molecules has focused on T-cell cytokine and chemokine responses, we next sought to evaluate the effects of these drugs on these events in human keratinocytes; Malp-2 is a TLR2/6-dependent microbial stimulus inducing a cytokine response in keratinocytes. Therefore, NHEKs were treated with the vehicle, Malp-2, pimecrolimus, or the combination of Malp-2 and pimecrolimus, and expression of IL-10, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 (CXCL8) was determined by qPCR. In contrast to enhanced AMP response, pimecrolimus suppressed the expression of IL-10 and IL-1β when stimulated by Malp-2 (Figure 4a). Similarly to these results, cell stimulation, including FK506 and cyclosporin A, also resulted in a decrease of IL-1β when stimulated by Malp-2 (Figure 4b). On the other hand, IL-6 and IL-8 expression was not inhibited and a small increase was detected. Expression of IL-4 and IL-17 was undetectable by qPCR in NHEKs (data not shown). Thus, these findings show that pimecrolimus selectively affects cytokine production in human keratinocytes, and these effects differ from the effects on AMPs and TLR expression.

Figure 4. Differential effect of pimecrolimus, FK506, and cyclosporin A on cytokine expression of human keratinocytes.

Transcript abundance of IL-10, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 was analyzed by real-time qPCR. (a) NHEKs were stimulated with vehicle, Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1), or the combination of Malp-2 and pimecrolimus (10 nM) for 24 hours. Similar experiments were performed using (b) FK506 and (c) cyclosporin A. Data are means of triplicates (+SD) from a single experiment representative of two independent experiments. Significances were calculated by unpaired Student’s t-test, with *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001.

Pimecrolimus enhances the ability of human keratinocytes to kill S. aureus

To determine whether the increase in AMP and TLR expression induced by pimecrolimus results in a change in the functional capacity of NHEK to kill bacteria, we next measured the antimicrobial killing activity of NHEKs against S. aureus. Total AMP activity was assessed by preparing lysates of NHEKs following treatment with test stimuli and then adding these lysates to actively growing cultures of S. aureus strain Δmprf. Pimecrolimus treatment significantly increased the antimicrobial activity of keratinocytes treated with 1,25D3 or Malp-2 (Figure 5a). As pimecrolimus is a derivate of the macrolactam ascomycin, we also examined whether pimecrolimus alone had antimicrobial activity in this assay. Pimecrolimus did not inhibit bacterial growth when added alone to bacterial cultures (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. Antimicrobial activity of human keratinocytes increases with pimecrolimus.

(a) NHEKs were stimulated with vehicle, pimecrolimus (10 nM), 1,25D3 (1 nM), Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1), or the combination thereof for 24 hours. Cell lysates were prepared as described under Materials and Methods, then added to approximately 20×103 CFUs S. aureus ΔmPRF. Bacterial growth was monitored over time by measurement of absorbance of culture at OD600. Data after 8 hours incubation are displayed. (b) To determine whether pimecrolimus itself has antimicrobial activity, it was directly incubated with bacterial cultures of S. aureus ΔmPRF and bacterial growth was monitored over time by OD600. Data are means of triplicates (+SD) from one experiment. Significances were calculated by unparied Student’s t-test, with *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Pimecrolimus inhibits Malp-2-induced nuclear translocation of NFAT and NF-κB in human keratinocytes

In T cells, the classical mechanism suggested for the immunosuppressive effects of calcineurin inhibition is through inhibition of NFAT translocation into the nucleus (Clipstone and Crabtree, 1992). The function of NFAT in keratinocytes has not been studied well. Therefore, we evaluated whether pimecrolimus inhibits nuclear translocation of NFAT and also examined the response of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), a transcription factor important to the immune response of many cell types, including keratinocytes (Karin, 2006; Rebholz et al., 2007). NHEKs were grown on chamber slides and localization of either NFAT or NF-κB was evaluated directly by immunostaining. In vehicle-treated NHEKs, staining of NFAT and NF-κB was observed in the cytoplasm of cells, with a perinuclear localization. Cells treated with Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1) alone showed increased nuclear staining of NFAT (Figure 6a) and NF-κB (Figure 6b). Pimecrolimus inhibited nuclear translocation of both NFAT and NF-κB following Malp-2 stimulation. Pimecrolimus at a concentration of 10 nM did not induce detectable changes in the cytoplasmic localization of NFAT or NF-κB in the absence of Malp-2.

Figure 6. Pimecrolimus suppresses NFAT and NF-κB nuclear translocation in human keratinocytes.

NHEKs grown on chamber slides were pretreated with the vehicle alone or with various concentrations of pimecrolimus for 30 minutes before stimulation with vehicle or Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1) for 16 hours. NHEKs were fixed and stained with an (a) anti-NFAT1 or (b) anti-NF-κB antibody as described under Materials and Methods to evaluate the pattern intracellular localization. Bar=50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Pimecrolimus cream (1%) is a topical formulation of a macrolactam ascomycin. It is used for treatment of atopic dermatitis. The mechanism of action of pimecrolimus in atopic dermatitis is not fully understood. It has been demonstrated that pimecrolimus binds with high affinity to macrophilin-12 (FK506-binding protein-12) and inhibits the activity of the calcium-dependent phosphatase, calcineurin. As a consequence, it inhibits T-cell activation by blocking the transcription of early cytokines. In particular, pimecrolimus inhibits at nanomolar concentrations IL-2 and IFN-γ (Th1-type) and IL-4 and IL-10 (Th2 type) cytokine synthesis in human T cells. In addition, pimecrolimus prevents release of inflammatory cytokines and mediators from mast cells in vitro after stimulation by antigen/IgE. While the preceding inhibitory effects have been observed, the clinical significance of these observations in atopic dermatitis is not known.

Recent advances in our understanding of the immune defense system of the skin inspired this investigation into the response of keratinocytes to pimecrolimus. Here we report the results of a series of first studies on the effect of this calcineurin inhibitor on keratinocyte-driven antimicrobial and other innate immune responses. Unexpectely, low concentrations of pimecrolimus enhanced expression of activation markers of the innate immune response in human keratinocytes. Specifically, expression of AMPs stimulated by 1,25D3 and/or Malp-2, and CD14 expression were enhanced. Pimecrolimus treatment resulted in an increase in the capacity of keratinocytes to suppress the growth of S. aureus. These findings are consistent with the notion of distinct regulatory systems governing adaptive and innate immune responses, namely: enhancement of innate immune response while “silencing” an adaptive immune response.

Pimecrolimus is used as an immunosuppressive drug for treatment of atopic dermatitis and other inflammatory skin diseases. However, to our knowledge, the effects of pimecrolimus on innate immune responses have never been studied. The goal of this study was to identify how pimecrolimus affects innate antimicrobial host defence mechanisms of keratinocytes. Pimecrolimus enhanced AMP expression stimulated by 1,25D3 and/or Malp-2, increased CD14 expression, and resulted in an increase in the capacity of keratinocytes to suppress the growth of S. aureus. These findings are contrary to expectations for a drug with potent immunosuppressive action on T cells, but not inconsistent with the distinct regulatory systems that have been uncovered for adaptive and innate immune responses. Our findings highlight the unique regulatory mechanisms that are active in epithelial antimicrobial function and suggest that the accepted model for action of topical immunomodulating drugs should be revisited.

Results presented here suggest that pimecrolimus can amplify multiple and distinct innate immune responses in keratinocytes. Host defense events that were measured included the expression of three independently regulated antimicrobial peptides, the expression of the pattern recognition receptor CD14, and the total antimicrobial activity of keratinocyte lysates. Pimecrolimus enhanced all of these indicators when present in combination with TLR2/6 ligand and/or in the presence of 1,25D3. TLR2 activation and the vitamin D pathway have been linked by recent findings that TLR2,6 stimulation in keratinocytes initiates the production of active 1,25D3 through upregulation of the converting enzyme CYP27B1 and subsequent 1-hydroxylation of stored 25D3. Our current findings demonstrate that the combination of pimecrolimus and 1,25D3 resulted in a stronger AMP response than that by pimecrolimus and Malp-2 alone. Thus, these findings suggest that pimecrolimus might also be involved in 1,25D3 signaling, or that the actions of pimecrolimus may modify genes also regulated by 1,25D3. A possible explanation for this might be found in revealing the genomic effects mediated by 1,25D3. Genomic effects of 1,25D3 are mediated by its nuclear hormone receptor, the vitamin D receptor, which acts as a transcription factor by binding to vitamin D-responsive elements in the promoter of responsive genes (Nagpal et al., 2005). Vitamin D-receptor ligand interaction mediates the regulation of transcription in at least three different ways: (1) it can positively regulate the expression of certain genes by binding to vitamin D-responsive elements, (2) it can negatively regulate the expression of other genes by binding to negative vitamin D-responsive elements, or (3) it can inhibit the expression of some genes by antagonizing the action of certain transcription factors, such as NFAT and NF-κB (Nagpal et al., 2005). The latter mechanism is thought to be mediated by competition of vitamin D receptor with NFAT for binding to the composite NFAT1-activator protein-1 enhancer motif and consequent interaction with c-Jun (Alroy et al., 1995; Takeuchi et al., 1998; Towers and Freedman, 1998). Also, it has been shown recently that 1,25D3 can affect NF-κB activity by inhibiting de novo synthesis of the NF-κB p50 protein and its precursor p105 in human lymphocytes (Yu et al., 1995), and by downregulation of c-Rel and Rel B in dendritic cells (Xing et al., 2002). Involvement of NFAT and/or NF-κB in 1,25D3-mediated effects may be part of a pathway by which 1,25D3 exerts its effects by targeting transcription factors other than the vitamin D receptor. Thus, inhibition of the NFAT- and NF-κB-signaling pathway by pimecrolimus might lead to enhancement of 1,25D3-mediated innate immune responses as those observed in this study.

As to the molecular mechanism of action in human keratinocytes, the data suggest that the stimulatory effects of pimecrolimus are due to NFAT and/or NF-κB acting as negative regulators of cathelicidin transcription and certain TLR-signaling events. In line with this hypothesis are findings that the human cathelicidin promoter has putative NFAT- and NF-κB-binding sites (Pestonjamasp et al., 2001). Precedence exists for negative regulatory elements in the cathelicidin promoter (Wu et al., 2002). In contrast to this, it has been reported that defensin’s expression can be induced by NF-κB activation (Wehkamp et al., 2004, 2006).

Recently, it has been reported that pimecrolimus and tacrolimus can induce release of the neuropeptides substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide from nerve fibers, which in turn leads to degranulation of mast cells (Stander et al., 2007). The authors suggest that pathways others than NFAT inhibition could be affected by pimecrolimus and tacrolimus. Similar pathways could be also affected in keratinocytes leading to amplification of the innate immune response. Hence, it remains to be determined which elements affected by pimecrolimus are involved in governing innate immune responses in keratinocytes. Candidates for analysis, therefore, include the immunophilins, calcineurin, NFAT, NF-κB, or other >hitherto unknown elements.

In conclusion, the observations presented in this study reveal a previously unknown observation in the regulation of innate immune function, suggest new areas for investigation of the mechanism of TLR and AMP responses, and might lead to new treatments. Various calcineurin inhibitors have proven clinical utility as therapeutic agents against inflammation and autoimmunity. Antimicrobial peptides can suppress the function of dendritic cell and are also important modifiers of the cutaneous inflammation and immune defense (Davidson et al., 2004; Bowdish et al., 2005; Di Nardo et al., 2007; Lande et al., 2007; Yamasaki et al., 2007). It is intriguing to speculate that part of the therapeutic benefit of these drugs has been though unrecognized effects on the function of the innate immune system. Targeted treatment of keratinocytes may offer opportunities for anti-infective therapy in combination with inhibition of inflammation. Future work is required to extend the current findings to in vivo systems and further define the signaling system responsible for these observations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and stimuli

Normal human keratinocytes were grown in serum-free EpiLife cell culture media (Cascade Biologics, Portland, OR) containing 0.06mM Ca2+ and 1× EpiLife defined growth supplement with the addition of 50Uml−1 penicillin and 50 μgml−1 streptomycin at 37 °C under standard tissue culture conditions. Cell cultures were maintained for up to four passages in this media and media changes were performed every other day. Cells at a confluence of 60–80% were stimulated with 1,25D3 (Sigma, St Louis, MO), pimecrolimus (Novartis, East Hanover, NJ), FK506 (Sigma), cyclosporin A (Sigma), Malp-2 (0.1 μgml−1; Alexis, Carlsbad CA), peptidoglycan (1 μgml−1; Invivogen, Sorrento Valley, CA), lipoteichoic acid (10 μgml−1; Sigma), poly-I:C (25μgml−1; Amersham, Piscataway, NJ), lipopolysaccharide (0.1 μgml−1; Sigma), Staphylococcus eneterotoxin B (10 ng ml−1; Sigma), or Staphylococcus protein A (10 μgml−1; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA).

Real-time qPCR

After cell stimulation, total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1 μg RNA was reverse transcribed using iScript (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The expression of cathelicidin was evaluated using an FAM-CAGAGGATTGTGACTTCA-MGB probe, using primers 5′-CTTCACCAGCCCGTCCTTC-3′ and 5′-CCA GGACGACACAGCAGTCA-3′. For expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, a VIC-CATCCATGACAACTTTGGTA-MGB probe with primers 5′-CTTAGCACCCCTGGCCAAG-3′ and 5′-TGGTCATGAGTCCTTCCACG-3′ was used as described (Schauber et al., 2006). Predeveloped Taqman assay probes (Applied Biosystems ABI, Foster City, CA) were used for analyzing the expression of HBD2, HBD3, CD14, TLR1, TLR2, TLR6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-4, and IL-17. All analyses were performed in triplicate, and were independent cell stimulation experiments performed with an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence detection system. Fold induction relative to the vehicle-treated control was calculated using 2(−ΔΔCt) method, where ΔCt=ΔCt(stimulant)−ΔCt(vehicle), ΔCt=Ct(target gene)−Ct(GAPDH), and Ct is the cycle at which detection threshold is crossed.

Fluorescence immunohistochemistry

NHEKs were grown on chamber slides and stimulated with pimecrolimus, Malp-2, their combination, or the vehicle. After acetone fixation and subsequent washings in phosphate-buffered saline, slides were blocked in 3% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 minutes at room temperature and stained with a polyclonal rabbit anti-hCAP-18/LL-37, or a polyclonal chicken anti-hCAP18/LL-37, a rabbit anti-NFAT (upstate), or a rabbit anti-NF-κB (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) antibody or preimmune serum. After washings in phosphate-buffered saline, slides were reprobed with secondary antibodies (FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-chicken antibody). After subsequent washings with phosphate-buffered saline, slides were mounted in ProLong Anti-Fade reagent containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and evaluated with an Olympus BX41 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) at an original magnification of ×400 or ×600.

Western blot

Keratinocytes were stimulated for 24 hours with pimecrolimus or 1,25D3, their combination, or the vehicle and subsequently lysed in ice-cold radio-immunoprecipitation buffer containing proteinase inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis IN). After centrifugation, equal amounts of protein were mixed with loading buffer (0.25 M Tris HCl, 10% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5% β-mercaptoethanol) and loaded onto a 16% Tris-Tricine gel (GeneMate, Kaysville, UT). After separation, proteins were blotted onto a polyvinylidene diflouride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and blocked in 5% milk (Bio-Rad) in TBS 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 hour at room temperature. After washings in TBS 0.1% Tween-20, membranes were stained with a mouse monoclonal anti-CD14 antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), washed again in TBS 0.1% Tween-20, and reprobed with a horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit antibody (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Stained protein was visualized with the Western Lightning system (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA). Densitometric analyses were performed using ImageJ version 1.37r.

Antimicrobial assay

Antimicrobial activity of stimulated and unstimulated epithelial cells was determined using a modified protocol described earlier (Schauber et al., 2006). Cells were grown and stimulated in media without antibiotics, harvested in 100 μl sterile H2O, and sonicated on ice for 20 minutes. Cell lysates were centrifuged and supernatants were used for antimcrobial assays. For solution killing assays, S. aureus ΔmprF (Peschel et al., 2001) was grown in tryptic soy broth (Sigma) overnight and then subcultured in 20% tryptic soy broth, 25mM NaHCO3, 1mM NaHPO4 until log phase. Approximately 20,000 bacteria (OD600 1.0 corresponds to 3.75×109 CFUs ml−1) were incubated with equal protein concentrations of cell lysates at 37 °C in 20% tryptic soy broth, 25mM NaHCO3, and 1mM NaHPO4. Bacterial growth over time was determined by optical density at 600 nm. To test whether pimecrolimus itself has antimicrobial activity, S. aureus ΔmprF was directly incubated with pimecrolimus at a dose up to 10 μM and bacterial growth was determined over time as described.

Cytotoxicity assays

A cytotoxicity detection kit based on measurement of lactate dehydrogenase activity (Roche) was used according the manufacturers’ instructions. Apoptotic and necrotic cells were quantified by annexin V and propidium iodide staining with fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a VA Merit award and NIH Grants AI052453 and AR45676 to RLG, a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to JS (ENG Scha 979/3-1), and a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to ASB (Bu 2212/1-1).

Abbreviations

- 1,25D3

1,25-(OH)2 vitamin D3

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- HBD

human β-defensin

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cells

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- qPCR

reverse transcriptase–PCR

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Footnotes

Part of this work was presented at the Society for Investigative Dermatology Annual Meeting, May 2007 (Büchau et al., 2007)

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

This study was funded, in part, by a grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

References

- Agerberth B, Charo J, Werr J, Olsson B, Idali F, Lindbom L, et al. The human antimicrobial and chemotactic peptides LL-37 and alpha-defensins are expressed by specific lymphocyte and monocyte populations. Blood. 2000;96:3086–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Daraji WI, Grant KR, Ryan K, Saxton A, Reynolds NJ. Localization of calcineurin/NFAT in human skin and psoriasis and inhibition of calcineurin/NFAT activation in human keratinocytes by cyclosporin A. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:779–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alroy I, Towers TL, Freedman LP. Transcriptional repression of the interleukin-2 gene by vitamin D3: direct inhibition of NFATp/AP-1 complex formation by a nuclear hormone receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5789–99. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramburu J, Azzoni L, Rao A, Perussia B. Activation and expression of the nuclear factors of activated T cells, NFATp and NFATc, in human natural killer cells: regulation upon CD16 ligand binding. J Exp Med. 1995;182:801–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowdish DM, Davidson DJ, Scott MG, Hancock RE. Immunomodulatory activities of small host defense peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1727–32. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.1727-1732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchau AS, Schauber J, Au N, Stütz A, Gallo RL. Pimecrolimus enhances innate immune function of normal human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:130. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Clipstone NA, Crabtree GR. Identification of calcineurin as a key signalling enzyme in T-lymphocyte activation. Nature. 1992;357:695–7. doi: 10.1038/357695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson DJ, Currie AJ, Reid GS, Bowdish DM, MacDonald KL, Ma RC, et al. The cationic antimicrobial peptide LL-37 modulates dendritic cell differentiation and dendritic cell-induced T cell polarization. J Immunol. 2004;172:1146–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo A, Braff MH, Taylor KR, Na C, Granstein RD, McInturff JE, et al. Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides block dendritic cell TLR4 activation and allergic contact sensitization. J Immunol. 2007;178:1829–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo A, Vitiello A, Gallo RL. Cutting edge: mast cell antimicrobial activity is mediated by expression of cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide. J Immunol. 2003;170:2274–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont FJ. FK506, an immunosuppressant targeting calcineurin function. Curr Med Chem. 2000;7:731–48. doi: 10.2174/0929867003374723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohm M, Agerberth B, Ahangari G, Stahle-Backdahl M, Liden S, Wigzell H, et al. The expression of the gene coding for the antibacterial peptide LL-37 is induced in human keratinocytes during inflammatory disorders. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15258–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge HS, Simmons RM, Underhill DM. Dectin-1 stimulation by Candida albicans yeast or zymosan triggers NFAT activation in macrophages and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:3107–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassberger M, Steinhoff M, Schneider D, Luger TA. Pimecrolimus—an anti-inflammatory drug targeting the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:721–30. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilborn JD, Frohm Nilsson M, Kratz G, Weber G, Sorensen O, Borregaard N, et al. The cathelicidin anti-microbial peptide LL-37 is involved in re-epithelialization of human skin wounds and is lacking in chronic ulcer epithelium. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:379–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AM, Jain J, Rao A, Hogan PG. Expression of the transcription factor NFATp in a neuronal cell line and in the murine nervous system. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Georgel P, Du X, Shamel L, Sovath S, Mudd S, et al. CD14 is required for MyD88-independent LPS signaling. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:565–70. doi: 10.1038/ni1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Zhang J, Yu FS. Toll-like receptor 2-mediated expression of beta-defensin-2 in human corneal epithelial cells. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:380–9. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, Chatterjee B, Wang YH, Homey B, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature. 2007;449:564–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, Howell MD, Nomura I, Hamid QA. New insights into atopic dermatitis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:651–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI21060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monticelli S, Solymar DC, Rao A. Role of NFAT proteins in IL13 gene transcription in mast cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36210–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal S, Na S, Rathnachalam R. Noncalcemic actions of vitamin D receptor ligands. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:662–87. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak N, Kwiek B, Bieber T. The mode of topical immunomodulators in the immunological network of atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:160–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong PY, Ohtake T, Brandt C, Strickland I, Boguniewicz M, Ganz T, et al. Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1151–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschel A, Jack RW, Otto M, Collins LV, Staubitz P, Nicholson G, et al. Staphylococcus aureus resistance to human defensins and evasion of neutrophil killing via the novel virulence factor MprF is based on modification of membrane lipids with L-lysine. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1067–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.9.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestonjamasp VK, Huttner KH, Gallo RL. Processing site and gene structure for the murine antimicrobial peptide CRAMP. Peptides. 2001;22:1643–50. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00499-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pütsep K, Carlsson G, Boman H, Andersson M. Deficiency of antibacterial peptides in patients with morbus Kostmann: an observation study. Lancet. 2002;360:1144–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebholz B, Haase I, Eckelt B, Paxian S, Flaig MJ, Ghoreschi K, et al. Crosstalk between keratinocytes and adaptive immune cells in an IkappaBalpha protein-mediated inflammatory disease of the skin. Immunity. 2007;27:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauber J, Dorschner R, Yamasaki K, Brouha B, Gallo R. Control of the innate epithelial antimicrobial response is cell-type specific and dependent on relevant microenvironmental stimuli. Immunology. 2006;118:509–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauber J, Dorschner RA, Coda AB, Buchau AS, Liu PT, Kiken D, et al. Injury enhances TLR2 function and antimicrobial peptide expression through a vitamin D-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:803–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI30142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlee M, Wehkamp J, Altenhoefer A, Oelschlaeger TA, Stange EF, Fellermann K. Induction of human beta-defensin 2 by the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is mediated through flagellin. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2399–407. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01563-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stander S, Stander H, Seeliger S, Luger TA, Steinhoff M. Topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus transiently induce neuropeptide release and mast cell degranulation in murine skin. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:1020–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuetz A, Baumann K, Grassberger M, Wolff K, Meingassner JG. Discovery of topical calcineurin inhibitors and pharmacological profile of pimecrolimus. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141:199–212. doi: 10.1159/000095289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumikawa Y, Asada H, Hoshino K, Azukizawa H, Katayama I, Akira S, et al. Induction of beta-defensin 3 in keratinocytes stimulated by bacterial lipopeptides through toll-like receptor 2. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1513–21. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi A, Reddy GS, Kobayashi T, Okano T, Park J, Sharma S. Nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) as a molecular target for 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-mediated effects. J Immunol. 1998;160:209–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towers TL, Freedman LP. Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene transcription is directly repressed by the vitamin D3 receptor. Implications for allosteric influences on nuclear receptor structure and function by a DNA element. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10338–48. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J, Cho Y, Dinh NN, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI. Activities of LL-37, a cathelin-associated antimicrobial peptide of human neutrophils. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2206–14. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Grzywacz B, Sukovich D, McCullar V, Cao Q, Lee AB, et al. The unexpected effect of cyclosporin A on CD56+CD16− and CD56+CD16+ natural killer cell subpopulations. Blood. 2007;110:1530–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-048173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T-T, Nestel F, Bourdeau V, Nagai Y, Wang Q, Liao J, et al. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J Immunol. 2004;173:2909–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehkamp J, Harder J, Wehkamp K, Wehkamp-von Meissner B, Schlee M, Enders C, et al. NF-kappaB- and AP-1-mediated induction of human beta defensin-2 in intestinal epithelial cells by Escherichia coli Nissle 1917: a novel effect of a probiotic bacterium. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5750–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5750-5758.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehkamp K, Schwichtenberg L, Schroder JM, Harder J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa- and IL-1beta-mediated induction of human beta-defensin-2 in keratinocytes is controlled by NF-kappaB and AP-1. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:121–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Ross CR, Blecha F. Characterization of an upstream open reading frame in the 5′ untranslated region of PR-39, a cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide. Mol Immunol. 2002;39:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing N, ML LM, Bachman LA, McKean DJ, Kumar R, Griffin MD. Distinctive dendritic cell modulation by vitamin D(3) and glucocorticoid pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:645–52. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki K, Di Nardo A, Bardan A, Murakami M, Ohtake T, Coda A, et al. Increased serine protease activity and cathelicidin promotes skin inflammation in rosacea. Nat Med. 2007;13:975–80. doi: 10.1038/nm1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu XP, Bellido T, Manolagas SC. Downregulation of NF-kappa B protein levels in activated human lymphocytes by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10990–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti M. The role of cathelicidins in the innate host defenses of mammals. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2005;7:179–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]