Summary

Chloroma, also called Granulocytic Sarcoma or Myeloid Sarcoma, is a rare malignant extra-medullary neoplasm of myeloid precursor cells. It is usually associated with myeloproliferative disorders but its appearance may precede the onset of leukaemia. Chloroma may be found in several extracranial sites. Involvement of the head and neck region is uncommon. Differential diagnosis is often difficult and includes acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, large cell NHL, lymphoblastic lymphoma and Ewing’s sarcoma. The case is presented of a maxillo-ethmoidal chloroma occurring in a case of poor prognosis acute myeloid leukaemia, emphasizing the clinical and cyto-histological features and problems concerning differential diagnosis.

Keywords: Paranasal sinuses, Malignant tumours, Chloroma, Myeloid leukaemia

Riassunto

Il Cloroma, anche detto Sarcoma mieloide o Sarcoma granulocitico, è un raro tumore maligno extramidollare costituito da cellule immature della serie granulocitaria. È usualmente associato ad un disordine mieloproliferativo ma può anche precedere l’inizio di una leucemia. Le localizzazioni extracraniche del cloroma sono molteplici, ma l’interessamento dei distretti cervico-facciali è poco comune. La diagnosi differenziale citoistologica può talvolta essere complessa, potendosi confondere con la leucemia linfobla-stica acuta, con il sarcoma di Ewing e con diversi quadri di linfoma linfoblastico e a grandi cellule. Gli Autori descrivono un caso di cloroma etmoido-mascellare in corso di leucemia mieloide acuta, ad esito infausto, sottolineando gli aspetti citoistologici e clinici ed enfatizzando le problematiche di diagnosi differenziale.

Introduction

Chloroma is a rare malignant extra-medullary neoplasm of myeloid precursor cells. It was described for the first time by Burns in 1811 1 and, later, called Chloroma by King in 1853 2 on account of its green colour which is believed to be caused by myelo-peroxidase, an enzyme present in the myeloid cells. In 1966, it was included in the Rapaport classification and almost three decades later was called Granulocytic Sarcoma or Myeloid Sarcoma according to the WHO classification 3.

This disorder often occurs in concomitance with an acute myeloid leukaemia and other myelo-proliferative disorders such as polycythemia vera (PV) and myeloid metaplasia 3 4. On the other hand, it rarely develops in patients with no symptoms of leukaemia, either in the peripheral blood or in bone marrow. In most of these patients, following the occurrence of chloroma, an overt acute myeloid leukaemia develops within 1 and 49 months. In any event, the presence of a chloroma is certainly the sign of poor prognosis 5–8.

A case of maxillo-ethmoidal chloroma is described which developed during the course of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), focusing on the clinical and cytohistological findings and emphasizing the difficulties concerning differential diagnosis.

Case Report

A 72-year-old female with M0 FAB AML under chemotherapy with hydroxycarbamide came to our attention at the Division of ENT, in August 2003, on account of right facial swelling and fever. The patient had been diagnosed, 12 months previously, with M0 FAB acute myloblastic leukaemia and treated with only hydroxycarbamide.

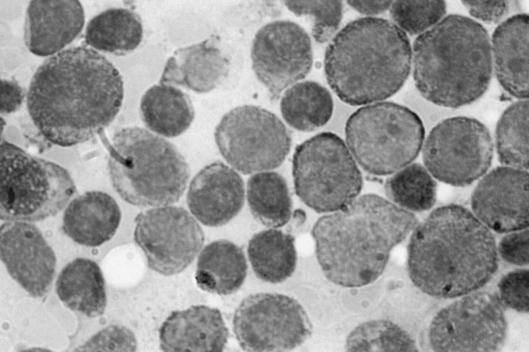

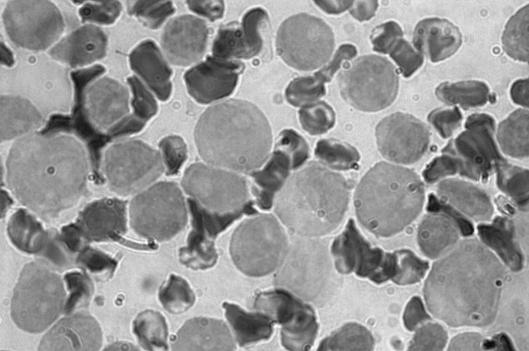

The diagnosis of AML was made from results of bone marrow aspirate that showed abundant cells presenting a homogeneous infiltrate of small and middle blastic cells, with little basophil cytoplasm without granules, and a nucleus with loose chromatin and prominent nucleoli (Fig. 1) and immunophenotypic study either on peripheral blood or on marrow (that confirmed the diagnosis of M0 FAB acute myeloblastic leukaemia with evident immature myeloblasts positive for CD13, CD34, CD117, partially positive for CD33 and negative for CD7, with Perox-negative stain) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Acute myeloblastic leukaemia M0 FAB (McGrunwald-Giemsa x100): bone marrow aspirate shows homogeneous infiltrate of small and middle blastic cells, with little basophil cytoplasm without granules, and nucleus with loose chromatin and prominent nucleoli.

Fig. 2.

Acute myeloblastic leukaemia M0 FAB with Perox-negative stain.

The physical examination showed hepatosplenomegaly. ENT examination showed a remarkable phlogistic swelling of the eyelid and of the right side of the face, with involvement of orbit, nasal cavity and maxillary sinus. The right nasal cavity was occupied by a solid, greyish, non-bleeding tissue. The posterior portion of the rhino-mesopharynx was covered by a purulent secretion. There were neither appreciable anomalies of the pharyngeal-laryngeal areas, nor cervical lymphadenopathy. The patient was admitted to our Department. Laboratory tests showed a remarkable leucocytosis (105.500) composed of immature myeloid elements (blasts) and by some polychromatophilic erythroblasts, a remarkable anaemia (haemoglobin 8.1 g/dl, erythrocytes 2,740,000, haematocrit 24.4%), hyperglycaemia (326) and hyperazotaemia (63). An urgent cerebral and maxillo-facial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the presence of solid pathological tissue filling the right maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses, almost the entire homolateral nasal cavity including the front part of the orbit, between the medial wall and the eye; that tissue, the diameter of which did not exceed 2.5 cm, showed disappearing borders and displaced the eye and the medial right muscle laterally (Figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 3.

Coronal contrast-enhanced CT scan demonstrated non-specific isodense opacity in right nasal cavity, maxillary and ethmoidal sinuses. Orbit is displaced laterally by the lesion.

Fig. 4.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan demonstrated non-specific isodense opacity in right nasal cavity and ethmoidal sinuses. Lesion infiltrates right medial muscle.

Ophthalmologic examination confirmed exophthalmus in the right eye with increased intra-ocular pressure (18 mm/Hg) associated with eyelid swelling and reduced eye motility.

Intravenous antibiotic (cefotaxime 6 g, 3 times a day, amikacine 3 g, 3 times a day), antimycotic (fluconazole 400 mg/d) and steroid treatment (betamethasone 8 mg bid) was started; 5 units of packed red cells were infused. Hydroxycarbamide was increased to 2 g/d.

As an empyema of the maxillary sinus and anterior ethmoidal cells was likely to be present, a surgical transnasal and transmaxillary approach (according to Caldwell-Luc) was performed. Following a Caldwell-Luc surgical procedure and emptying of the right rhino-ethmoidal areas through the nasal way a large amount of greyish, non-bleeding necrotic-like parenchymatous tissue was removed. The pathologic examination was positive for a secondary extra-medullary location of AML or chloroma. Most of the tissue was narcotized; however, in the area in which the necrosis was less evident, an intra-vascular and interstitial infiltrate was present composed of round-shaped cells, not cohesive, with a reniform nucleus, mainly positive for CD34 and MPO. A different level of maturation between marrow blast and extra-nodal blast can be taken into account to explain the different peroxidase pattern.

No cytogenetic studies were carried out either on the bone marrow or on the neoplastic cells.

Despite medical and surgical treatment, the patient’s clinical conditions gradually deteriorated, fever increased, anuria occurred and the patient died 10 days after being hospitalised.

Discussion

Chloromas are rare extra-medullary neoplasms with an incidence between 3 and 4.7% of the myelo-proliferative diseases 9 10. In about 70% of cases, they occur during the course of AML or chronic myelo-proliferative disorders such as PV or agnogeneic myeloid metaplasia, because of the capacity of immature myeloid cells to massively invade the extra-medullary organs. Several factors may contribute to the development of an extra-medullary disease, namely cytogenetic abnormalities and the cellular surface markers. In fact, chloromas develop mostly concomitantly with the FAB subtype M5a, M5b M4 and M2 of the AML 9.

The incidence of chloromas is between 3-9.1% of all AML 4 11 12, preferentially in young patients or in children with no difference between sexes 13. The organs most frequently involved are bones and periosteum probably due to the anatomical proximity with the bone marrow. In fact, from the bone marrow, through the Haversian canals, the tumoural cells can infiltrate the periosteum, particularly of the skull, sternum, ribs, orbit, spine, sacrum and proximal portions of the long bones. From here, the chloroma cells spread to the blood invading any organs. The most common sites of tumour invasion are the peritoneum, pericardium, bronchus, bladder, mediastinum, kidneys and lung 4 14–18.

The frequency of the head and neck region varies, according to the literature, between 12% 7 and 48% 19. In this region, the most frequently affected sites are the soft palate, the rhinopharynx, orbit, salivary glands, scalp and face 7. Uncommon sites of chloroma localization are: the jaw 20 21, facial nervus 22, lips 23, nasal cavity 24, maxilla 25 and temporal bone 22.

The clinical manifestations of a chloroma are aspecific, consisting only in local pain and a local mass effect. In the case of rhinosinusal involvement, the epistaxis may be supported by several factors, particularly thrombocytopenia and ischaemic necrosis of the nasal mucosa secondary to leukaemic infiltrate. Furthermore, persistent infection of the upper respiratory ways may be observed which shows a poor response to standard medical treatment 26. Macroscopic examination of a chloroma is characterized by a greenish mass due to the presence of the myeloperoxidase enzyme in the immature granulocytic cells. Very rarely, myeloperoxidase is absent and then the mass is not characterized by the classic green colour that gives it its name 27.

As far as concerns cytologic findings, the chloroma is composed of dyshomogeneous cells with few cytoplasm elements, round to oval nuclei, a sharply delimited nuclear membrane, finely granular chromatin and prominent nucleoli 28. When there is no concomitant leukaemia, diagnosis of chloroma may be difficult. Routine histological examination of these tumours shows a pleomorphic infiltrate of primitive cells of varying size and nuclear configuration 29. Haematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining does not identify granulocytic cells and the neoplasm may appear histologically as a sheet of round monomorfe cells with no recognizable pattern. The most frequent finding is a widespread infiltrate of mononucleate and granulocytic cells, variably mature, among which the typical eosinophilic myelocytes 9.

The histological differential diagnosis may be difficult due to the poorly differentiated myeloblasts or in the absence of the greenish colour. The tumours that can be confused with chloroma are histiocytic lymphoma, poorly differentiated lymphoblastic lymphoma, lymphoma with large cells, Ewing sarcoma, some acute lymphocytic leukaemia as well as primitive neuroepithelial tumours 5 30. However, fundamental for diagnosis, apart from the microscopic examination, is immunochemical staining. Use of staining with naphtol-ASD-chloro-acetate esterase (CAE) and with anti-lysozyme immunoperoxidase allows us to obtain a correct diagnosis of 75% and 85%, respectively. It is, in fact, known that mature and immature granulocytic cells, with the exception of myeloblasts, show a positive activity to the chloro-acetate esterase. This staining is useful to distinguish chloroma from histiocytic and non-histiocytic lymphoma 31. All granulocytic cells, including myeloblasts and myelocytes, stain positive for lysozyme, whereas the lymphocytes are negative 7. Furthermore, granulocytic cells are different from the monocyte due to the negligible reaction to the staining with the alpha-naphtol-acetate esterase 32. In our case, a different level of maturation between marrow blast and extra-nodal blast can be taken into account to explain the different peroxidase pattern.

It is sometimes mandatory, on account of the very heterogeneous morphological characteristics of some chloroma, to use additional diagnostic techniques, such as ultrastructural studies by means of electron microscopy. More recently, analysis of the chromosomal translocations and the use of more refined immuno-histochemical staining have been adopted in the classification of these neoplasms in order to correlate the morphological characteristics to the clinical behaviour 5 6 19 25.

CT and MR are not considered essential for diagnosis since they do not show specific signs for chloroma. In the CT scan, a massive tumour occupying the nasal cavities and the paranasal sinuses may be associated with the infiltrate of a particular bone with erosion of the structures of the maxilla 25. In the intracranial chloroma, the CT scan shows isodense, or slightly hyperdense, lesions in relation to the surrounding cerebral parenchyma, with homogeneous “enhancement”, generally without calcifications; in this case, differential diagnosis with meningioma, the lymphomas and metastatic tumours is necessary 33 34. MR scan of an intracranial chloroma involving the orbit and/or the paranasal sinuses shows the presence of the hypointense lesions on T1-weighted images and the isointense lesions on T2-weighted images, in relation to the white matter 13 35.

The prognosis of acute, non-lymphocytic leukaemia that is associated with chloroma, even if poor, has decisively improved thanks to the development of more adequate and effective associations of chemotherapeutic drugs 25 36. Chloromas are radiosensitive and local radiotherapy can be associated with chemotherapy. The earlier detection of extra-medullary granulocytic sarcomas could better define the real prognosis of these rare neoplasms 36.

References

- 1.Burns A. Observations of surgical anatomy. In: Burns A, editor. Head and neck. Edinburgh: Thomas Royce and Company 1811, p. 364-6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.King A. A case of chloroma. Monthly J Med 1853;17:97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rappaport H. Tumors of the hematopoietic system. In: Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institutes of Pathology 1966, p. 241-3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassichis B, McClay J, Wiatrak B. Chloroma of the masseteric muscle. Int J Ped Otorhinolaryngol 2000;53:57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alessi DM, Karin R, Abemayor E, Crockett DM. Granulocytic sarcomas of the head and neck. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 1988;114:1467-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansi JL, Selby PJ, Carter RL, Powles RL, McElwain. Granulocytic sarcoma: a diagnosis to be considered in unusual lymphoma syndromes. Postgrad Med J 1987;63:447-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieman RS, Barcos M, Berard C. Granulocytic sarcoma: A clinicopathologic study of 61 biopsied cases. Cancer 1981;48:1426-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;11:121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrd JC, Edenfield WJ, Shields DJ, Dawson NA. Extramedullary myeloid tumors in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: a clinical review. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:1800-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uyesugi WI, Watabe J, Petermann G. Orbital and facial granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma): a case report. Pediatr Radiol 2000;30:276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lukes RJ, Collins RD. Tumors of the hematopoietic system. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology 1992, p. 332-3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Books HW, Evans AE, Glass RM, Pang EM. Chloromas of the head and neck in childhood. The initial manifestations of myeloid leukemia in three patients. Arch Otolaryngol 1974;100:306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao SC, Yuh WT, Sato Y, Barloon TJ. Intracranial granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma): MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomog 1987;11:938-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris DW, Ostlere LS, Rustin MHA. Cutaneous granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) presenting as the first sign of relapse following autologous bone marrow transplantation for acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Dermatol 1992;127:182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menasce LP, Banerjee SS, Beckett E. Extra-medullary myeloid tumor (granulocytic sarcoma) is often misdiagnosed: a study of 26 cases. Histopathol 1999;34:391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nounou R, Al-Zahrani HH, Ajarim DS, Martin J, Iqbal A, Naufal R, et al. Extramedullary myeloid cell tumours localised to the mediastinum. A rare clinicopathological entity with unique karyotypic features. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:221-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Paz R, Canales MA, Hernandez-Navarro F. Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) of the lung. Br J Haematol 2003;120:176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park HJ, Jeong DH, Song HG, Lee GK, Han GS, Cha SH, et al. Myeloid sarcoma of both kidneys, the brain, and multiple bones in a nonleucemic child. Yonsei Med J 2003;44:740-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller S, Sangster G, Crocker J. An immunohistochemical and clinicopathological study of granulocytic sarcoma (‘chloroma’). Hematol Oncol 1986;4:101-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conran MJC, Keohane C, Kearney PJ. Chloroma of the mandible: a problem of diagnosis and management. Acta Paediatr Scand 1982;71:1041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reichart PA, Roemeling R, Krech R. Mandibular myelosarcoma (chloroma): Primary oral manifestation of promyelocytic leukemia. Oral Surg 1984;58:424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman P, Johnson SAN. Mastoid chloroma as relapse in acute myeloid leukemia. J Laryngol Otol 1980;94:1423-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadick N, Edlin D, Myskowski PL. Granulocytic sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1984;120:1341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prades JM, Alaani A, Mosnier JF, Dummollard JM, Martin C. Granulocytic sarcoma of the nasal cavity. Rhinology 2002;40:159-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takaue Y, Culbert SJ, Van Eys J, Dalton WT Jr, Cork A, Trujillo JM. Spontaneous cure of end-stage acute nonlymphocytic leukemia complicated with chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Cancer 1986;58:1101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanford DM, Becker GD. Acute leukemia presenting as nasal obstruction. Arch Otolaryngol 1967;85:102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pui MH, Fletcher BD, Langston JW. Granulocytic sarcoma in childhood leukemia: imaging features. Radiology 1994;190:698-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mockli G. Granulocytic sarcoma presenting as a retroperitoneal lymph node mass. A case report with diagnosis by fine needle aspiration biopsy and flow cytometry. Acta Cytol 1997;41:1525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pehner LP. Soft-tissue sarcomas of childhood: the differential diagnostic dilemma of the small blue cell. NCI Monogr 1981;56:43-59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fellbaum C, Hansmann ML. Immunohistochemical differential diagnosis of granulocytic sarcoma and malignant lymphomas on formalin fixed material. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Histopathol 1990;416:351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dreizen S, McCredie KB, Keating MJ. Mucocutaneous granulocytic sarcomas of the head and neck. J Oral Pathol 1987;16:57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Arch Dermatol 1987;123:251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sowers JJ, Moody DM, Naidich TP, Ball MR, Laster DW, Leeds NE. Radiographic features of granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma). J Comput Assist Tomog 1979;2:226-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bulas RB, Laine FJ, Das Narla L. Bilateral orbital granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma) preceding the blast acute phase of acute myelogenous leukemia: CT findings. Pediatr Radiol 1995;25:488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freedy RM, Miller KD Jr. Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma): sphenoidal sinus and paraspinal involvement as evaluated by CT and MR. Am J Neuroradiol 1991;12:259-62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deme S, Deodhare SS, Tucker WS, Bilbao JM. Granulocytic sarcoma of the spine in nonleukemic patients: report of three cases. Neurosurgery 1997;40:1283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]