Born in Genoa in 1782 (and not 1784, as erroneously held in some biographies), Nicolò Paganini (Fig. 1), left an undeniable mark, not only on the history of instrumental music, but also on social life at the beginning of the 19th Century. He was, indeed, the most sincere expression of synthesis between genius and nonconformist. Intelligence manifested at a very early age, with a history very similar, from this point of view, to that of Mozart, and he very soon became the idle of the masses passing from one success to another, throughout the capitals of Europe. Romantic ideals profoundly permeated not only his activity as an exceptional performer and bright composer, but also his entire existence as an artist and man. Paganini’s life was, in fact, truly hectic, undisciplined and vagabond which certainly contributed to the onset of the many morbid events that affected him, particularly in later life when the universal fame, already reached and consolidated, would have allowed him to lead a much quieter life (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Nicolò Paganini in a portrait (by Julien).

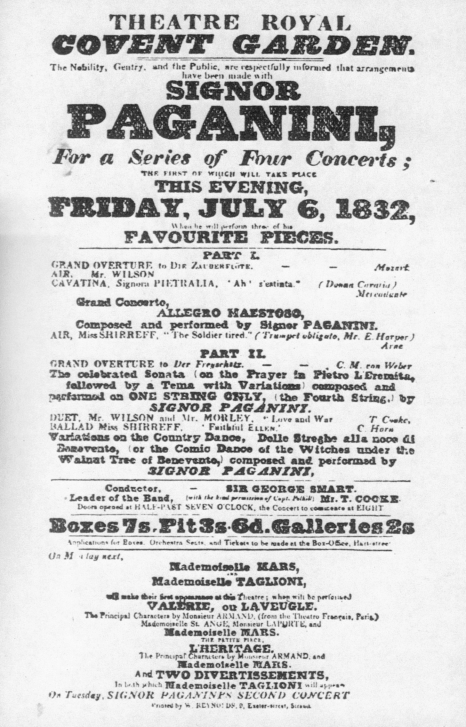

Fig. 2.

Announcement of a concert by Paganini at Covent Garden, London in 1832.

His inability to restrain himself was essentially due to a constant state of hyperactivity, pride and ambition, always endeavouring to exceed himself and to the awareness that he could arouse, as if by magic, applause for every performance, from a delirious audience. It is well known that at the height of every musical performance, he might break one, two or, perhaps, even three strings of his violin, continuing to play the same extremely difficult music with only one string. In 1832, he even managed to give 65 concerts, in 30 different European cities, in only three months. This exceptional strain forced him, in his latter years, to observe periods of inactivity in order to cure and improve his health which was becoming more and more precarious. Of the various morbid manifestations affecting Paganini, one in particular, saddened and tormented the latter years of his life: a severe form of dysphonia which prevented him from speaking. The great composer Héctor Berlioz, in his memoirs, recalls a meeting with Paganini, in December 1838: “Due to this laryngeal disorder, he had completely lost his voice and only his son … could hear, or rather guess, his words …” Achille, his legitimate son, who was 13 years old, at the time, would place his ear to his father’s mouth, acting, in fact, as his interpreter (Fig. 3): a heartbreaking situation that continued until the death of the great artist, in Nice, on May 15th, 1840. Due to the lack of vocal expression, it was impossible for Paganini to make confession before his death. Thus, the ecclesiastic authorities chose to condemn this event and rumours followed concerning his behaviour, considered to be virtually heretic, for which his burial, in consecrated ground, was delayed for very many years.

Fig. 3.

Achille Paganini as a child (by Neil).

As far as concerns the causes of the very severe dysphonia, two hypotheses have been advanced, at various times: the first, that this was a case of a laryngeal lesion resulting from syphilis: the other, that it was a lesion arising from tuberculosis. Neither of these, however, was supported by any reliable elements proving the diagnosis. The suspicion that Paganini was suffering from a syphilis infection was expressed by doctors in Prague who, in 1828, had operated on Paganini for necrotizing osteitis of the jaw (which, moreover, healed). This theory was supported by François Magendie who, in 1835, diagnosed rectal stenosis and by Guillaume who in 1839 successfully treated him for an ulcerative lesion in the velum palatinum. These hypotheses were not supported by the local evolution of the lesions, nor by the onset of other tertiary localizations. It would, therefore, be unwise, given the lack of other parameters, to suggest a laryngeal disorder of this type.

The diagnosis of tubercular laryngitis, instead, would appear more feasible, a theory repeated in most biographies and confirmed by significant clinical elements such as fever and cough which tormented the patient for many years, and also two severe episodes of hemoptysis which occurred in 1833 and 1840. On the other hand, Paganini himself in 1833 wrote to his friends telling them he was suffering from a “disease on his chest” and diagnosis of TB of the lungs was confirmed by doctors who were treating the patient between 1836 and 1837, such as, for example, Borda from Pavia and Spitzer in Marseilles.

More recently, an interesting new theory has been put forward in the attempt to explain the dysphonia of this great violinist: recurrent paralysis caused by an abnormal dilatation of the arch of the aorta. It is well known that often anatomical cardiovascular changes, particularly of the aorta, are present in patients with Marfan’s syndrome, a syndrome that has often been held to account for the particular conformation and mobility of Paganini’s hand which was able to achieve such exceptional performances of infinite technical quality. Indeed, the typical characteristics of this pathological condition (a tall thin body, particularly long thin arms and hands, abnormal movements as far as concerns articulation) would be perfectly in keeping with the somatic characteristics of Nicolò Paganini (Fig. 4a, b).

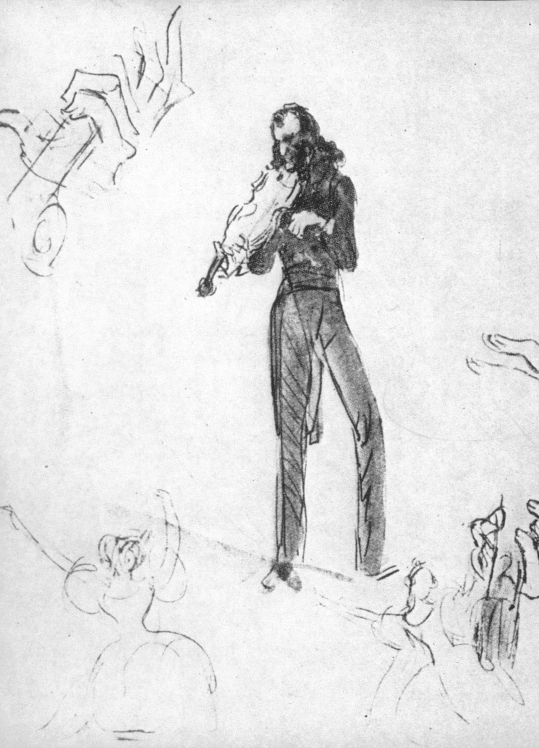

Fig. 4a, b.

Position of Paganini’s hands and body during a concert in 1830, captured by L.P.A. Burmeister, who according to Heine was the only painter to have reproduced the exact physionomy of the artist.

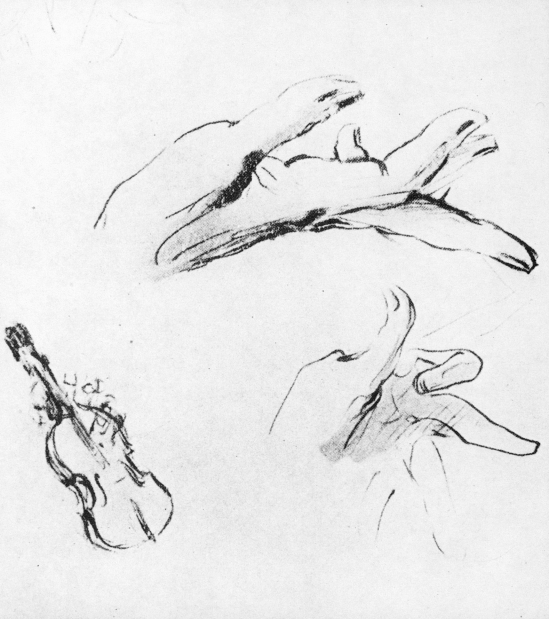

In 1831, the Parisian physician Francesco Bennati, well-known to specialists in laryngological disorders as one of the first to focus studies on the singing voice, when examining the patient was most surprised to find considerable lassitude of the ligaments as well as the extraordinary articular mobility especially of the wrist and hands of the famous violinist from Genoa (Fig. 5). The American Schonfeld (1956) was the first to advance the hypothesis that Paganini was affected by the syndrome that Marfan had described in 1896. This hypothesis was later accepted also by other scientists such as Paolo Mantero (1994) and Giovanni Brigato (2003). Based on these elements, the dysphonia has been interpreted as a consequence of recurrent paralysis due to aortic ectasia, even if to justify such a severe vocal disorder, one should suspect bilateral chord paralysis in abduction.

Fig. 5.

Cast of Paganini’s right hand.

There can be no doubt that the abnormal anatomy of the ligaments and articulation of the hand had been a very definite advantage and certainly not restraint for the instrumental skills of the virtuoso Paganini.

References

- 1.Bennati F. Notice physiologique sur Niccolò Paganini. Revue de Paris 1831;1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berlioz H. Memoires. Paris; 1870. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berri P. Il calvario di Paganini. Savona; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brigato G. Paganini, il suo violino, la sua malattia. Realtà Nuova 2003;4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Contestabile GC. Vita di Nicolò Paganini. Milano; 1936. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neil E. Nicolò Paganini. Genova; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vyborny Z. Paganini sconosciuto: lettere dalla Francia. Rassegna Archivio di Stato 1961;3. [Google Scholar]