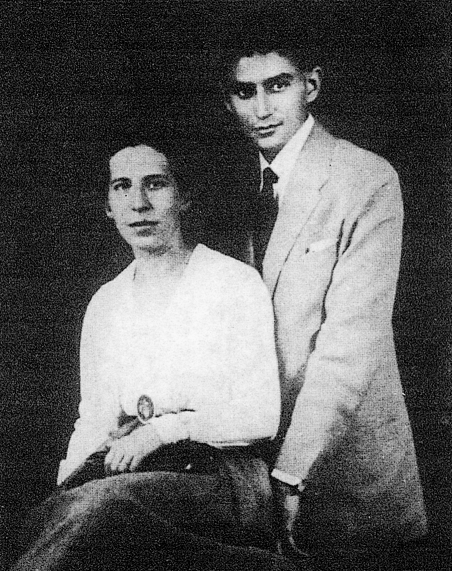

Franz Kafka was born in Prague, 13th July 1883, into a family of German Jews. The family was of German culture but as they belonged to the Ghetto, they were excluded from relationships with the German minority in Prague. Franz Kafka’s father ruled the family with great Authority. “Faced with intolerance and the tyranny of my parents, I live with my family more as a stranger than a foreigner” he writes, and, in fact, he was doubly aware of feeling a foreigner, within his family and in his own City (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Franz Kafka.

In 1901, after having attended the Chemistry Course for two weeks and that of Germanic studies for six months, he decided to transfer to the Faculty of Law, considered to be less exacting, and which allowed him to find a job and to start his writing. He gained his degree at the German University, in Prague, on 18th June, l906. It was at about that time that the early signs of lung tuberculosis became apparent which eventually led to his early death at just 41 years old.

Two years after gaining his degree, he was offered a contract with Arbeiter-Unfall Versicherungs Anstalt (Institute of Insurance for Accidents at Work, at the Prague Office of “Assicurazioni di Trieste”) which allowed him to be free in the afternoon and to dedicate his time to writing. Unfortunately, due to fatigue, he had to rest and, therefore, he did most of his intellectual work at night. He began to suffer from insomnia and became intolerant to noise. Changes occurred in his clinical picture, with onset of furuncolosis, asthenia, constipation as well as neuro-vegetative disorders. He turned to “crude-vegetarian” treatment. In 1912, he wrote to his friend Max Brod telling him that he had come very close to suicide. In 1909 and 1913, he spent some time in Riva del Garda in a Clinic which was well known for the treatment of neuro-asthenia, assimilation disorders, as well as heart and lung diseases. A few years later, his nerves had gone completely to pieces, he suffered from severe and frequent headaches and lived in a state of deep depression, with a tendency to self destruction. On August 9th l917, tuberculosis was clearly evident, becoming manifest with haemoptysis. He spoke of the onset as follows: “It was about 4 o’clock in the morning. I woke up and was surprised by the strange amount of saliva in my mouth, I spat it out then decided to turn on the light. That is how it began. Crleni, I don’t know if that is how it’s written, but it is a suitable expression for this clearing of the throat. I thought it was never going to finish. How was I going to stop this fountain if I had never started it (…) This, then is the situation of this spiritual disease, tuberculosis” 1.

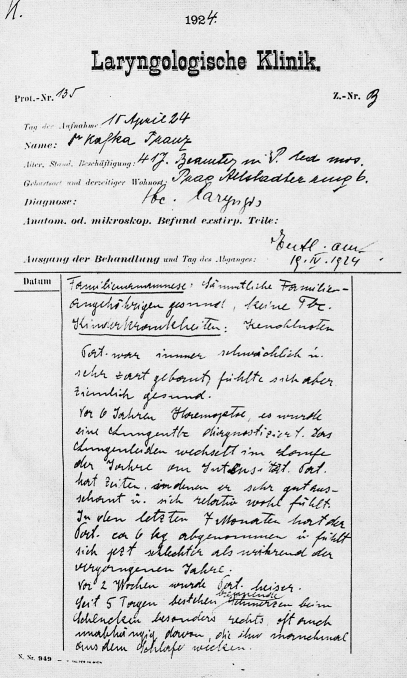

Five years earlier, he had met Felice Bauer (Fig. 2) with whom he corresponded frequently (these were the years of “Metamorphosis” and “The Trial”. In 1919, he meets Julie Wohryzeck, but leaves her after only a few months when he meets Milena Jesenska. His love-life is a reflection of his insecurity, of his state of mind; he dreads losing his freedom, but is afraid, at the same time, of being left on his own.

Fig. 2.

Franz Kafka and Felice Bauer (from Sterpellone).

The tuberculosis becomes more severe and he is then hospitalised in Merano where the fever becomes not only continuous, but also increases, and his cough, dry and annoying. It was in Merano that he began to correspond with Milena Jesenska who was to become a precious source of information regarding his state of physical and mental health. There were now clear signs of “the self-destructive mania, the need to torment and humiliate himself, the sense of personal emptiness and helplessness” 2.

In 1920, he went into a Sanatorium in the mountains. He was suffering so much that he asked Dr. Klopstock to give him a fatal dose of opium: “kill me or else you are a murderer”. But, fortunately he recovered and returned to Prague. Here he meets Dora Dyamant (16th June, 1923) and goes to live with her in Berlin.

In February 1924, his state of health deteriorated and he was taken to the Clinic of Prof. Hajek in Vienna; the tuberculosis had invaded the larynx so he was transferred to the small Sanatorium in Kierling where Prof. Hofmann proceeded with alcoholisation of the superior laryngeal nerve.

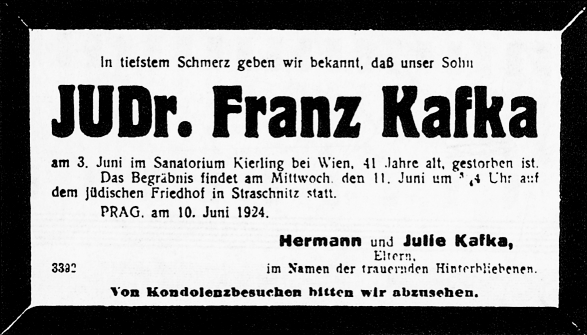

Due to the lack of any aetiological treatment for the Koch bacteria, the only possibility, at that time, was palliative treatment. As far as concerns the specific localisations in the larynx, responsible not only for violent crises of coughing, resembling whooping-cough, but also intense pain due to involvement of the arytenoids, making it difficult both to eat and to sleep, it was decided to proceed with cervical infiltrations of the superior laryngeal nerve with a solution of 1% cocaine, plus alcohol (60-80%) and possibly 1% Stovaine. The infiltrations had a beneficial effect on the symptoms, but had to be repeated every 8-10 days. The patient’s general conditions, however, were so poor that after a few months – 3rd June 1924 – Kafka died (Figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 3.

Copy of the clinical chart of Franz Kafka when he was hospitalised in the ENT Institute, in Vienna, in 1924. Head of the Institute in Lazarettgasse, at that time, was Markus Hajek (from Skopec and Majer).

Fig. 4.

The new Laryngology Clinic in Lazarettgasse one of the most modern in Europe, where Franz Kafka was an inpatient in the Twenties (from Skopec and Majer).

Works of Kafka and his relationship with the disease

First editions

Betrachtung. Leipzig: 1912.

Die Verwandlung. Leipzig: 1915.

In der Strasskolonie (In the Penal Colony). Leipzig: 1919.

Published after Kafka’s death

Der Prozess. Berlin: 1925.

Das Schloss. Munich: 1926.

Amerika. Munich: 1927.

Franz Kafka is a complex, even absurd, Author, difficult to understand unless you are prepared to penetrate the meanders of his personality. Some elements come to light as possible clues of his work. First of all, he is the son of Jews, long since part of the Germanic ambient, thus partly detached from their original traditions, yet not accepted for the very fact that they are Jews. Then, another aspect having a strong influence on the development of young Kafka’s character is the relationship with his family, with a domineering father which would certainly not have contributed favourably to the correct development of a delicate personality. A third factor concerns the onset of psychological disorders which blossom into neurosis, complicated by psychosomatic disorders, associated with an organic disease, tuberculosis of the lungs. Any approach to his works cannot disregard the psychological factors. Kafka is a connoisseur of Freud’s work and he too practices analysis, recalling episodes of his childhood, reconstructing the relationship with his parents, especially his father.

The physical disease does not come into his works whilst the mental disorders are well represented, often by the principal male characters, most of which autobiographical. In fact, the leading figures in Das Schloss, Der Prozess (Fig. 5) or Amerika, are gloomily alone, affected by a sense of guilt which crushes them completely and condemns them to a desolate existence, on the outskirts of society, just like their Creator. Like Him, they share an important characteristic: uncertainty. They are unable to choose, they are condemned to a non-life. Kafka himself in his diaries refers to himself as a non-born, condemned to die, without having lived. His physical illness, on the other hand, is not represented in his works, tuberculosis is never mentioned, even if, reading between the lines, several characters resemble figures condemned to death, but carry on completely ignorant of their fate, sick people who continue on their way, not caring and incurable. Another very important topic, on a par with the disease, is Hebraism which is never explicitly mentioned in any of his works, but which, again reading between the lines, is constantly referred to.

Fig. 5.

Announcement of Kafka’s death.

The key figures in his stories are healthy men, who, however, are weakened by their mental state as, for example, the land-surveyor K. In The Castle: at the very moment when the high government official Brugel can miraculously help him, he is so deprived of energy that he drops fast asleep. The topic of insomnia and the impossibility of being able to sleep is constantly found in his writings. The Kafka characters, like their Author, are never at peace, not even in everyday and the simplest of activities, such as eating and sleeping.

As far as concerns the fact that, in the works of Kafka, no direct mention is made of the disease, it should be pointed out that sometimes the problem of the body as a foreign element, in itself, emerges, as for instance in Metamorphosis, in which the leading character is transformed into a horrendous insect. In other stories, gross figures appear which are enormous in size, like, for example, the father in The Sentence or the singer Brunelda, or vice versa, the thin and tiny people, like the fasting artist, the second self of Kafka who dies of starvation.

The entire work is the translation of the sense of estrangement of Kafka, with respect to the outside world, of his desire and, at the same time, the impossibility to live everyday reality like anybody else, to partake of the enjoyment of affection and the opportunities that life offers. He lives this state of uneasiness, as if guilty, convinced that he is the cause. He escapes, therefore, into his own world, that of literature, living a condition as if alienated by society. “Often his stories and novels show the characteristics of dreams, as if, in the night, whilst he was writing, he had fixed his fantasies, his hallucinations on paper” 3.

As far as concerns the tuberculosis, this was considered as positive, something that created situations allowing him to live an existence in which he feels at ease. It was not the physical disorder that was advanced and severe, but rather the mental disease that, in order not to overcome the individual with the force of torment, found a way of escape in the physical disorder.

Kafka writes to Milena: “There – the brain no longer tolerated the worries and the pain inflicted upon it. He said: I can suffer this no longer; but, if there is still someone who is interested in preserving everything, may he relieve me of some of the weight, and it will be possible to still live for a little while. Then the lungs came forth, that – anyway – had nothing to lose. This negotiation between the brain and the lungs, which, not to my knowledge, was going on, must have been frightening 2”.

And he writes again to Milena: “I am mentally handicapped, the lung disease is none other than an overflow of the mental disease”. Kafka goes as far as defining the lung tuberculosis, from which he is suffering, as spiritual disease 1. Regarding the way in which Kafka interprets the relationship between his physical disease and the mental disease, according to the psychoanalysts, this is an ambiguity which is part of poetic licence. Kafka, like Freud, sees the disease from a psychoanalytical viewpoint, with the only difference that Freud, in his analysis, made use of instruments of a scientific nature, whilst Kafka uses instruments only of a poetic kind.

Kafka is not just an ordinary person, he is different, he lives in a state of anxious solitude, foreign to everyone, he is not “at home” in his own city, nor with his own people, nor within his family, nor will he ever find a woman with whom to share his life. This difference is expressed in the form of a mental disorder. He, therefore, anxiously awaits, and positively accepts, the physical illness, which releases some of the interior suffering onto the body and which underlines his being different, his uniqueness. According to Kafka, someone who is different and a lone wolf cannot be healthy, it has to show also in the body.

The idea of suicide

As already mentioned, Kafka first had the idea of suicide in 1912. Even though he was continuously dissatisfied with himself and his life, due to a constant sense of fault, he would not appear to have seriously contemplated suicide (i.e., a rapid and sudden end to life). The only time he seriously considered this choice was after having quarrelled with his family, when his dearly loved sister Ottla (the only person really able to communicate with him and to peep a little into his soul) took the side of his parents against him. Moreover, throughout his life, the delusions he endured had always been calculated and expected, resulting from his constant state of indecision; they were part of the prolonged and daily sufferance of Kafka, they were not extraordinary and sudden, as in the case of the quarrel with his sister.

Within the context of daily suffering, another form of suicide, less obvious, but no less terrible, surrounds Kafka: the long illness which takes the form of a long and accepted suicide. Kafka, burdened as he is with a sense of guilt, cannot put a sudden end to his life, he has to make amends before he dies. As a result, he no longer adheres to his treatment, he refuses food, at least he eats very little and in a disorganized fashion. In much the same way, he has difficulty in accepting his own body which he often regards as something not belonging to him, that interferes with his problems and his weariness, distracting him from his literary activities. We know from his letters of his fears, not only towards other people’s bodies but, in particular, sexual relationships with women.

The topics death-suffering-amendments were admirably dealt with in one of his most horrific stories: In the Penal Colony. Those condemned to death were submitted to prolonged torture, their skin is cut into with a harrow, the incisions, initially, not being easily deciphered, but with time, they become visible to their eyes, together with the suffering flesh. Now, in agony, they manage to decipher them: it is the explanation of the guilt, which makes them die with the suffering, “intelligence emerges even in the most slow-witted. It begins to spread from the eyes. The sight would be enough to make anyone lie down alongside the condemned person under the harrow”. Perhaps, this is what Kafka hopes to achieve, with his slow and painful suicide: that the truth will emerge, that he will be able to understand the meaning of his life and of his suffering. But this will certainly not happen in the painful agony, as for the commander in the story cited above, he will perish under the harrow and in his eyes “there was no sign of the promised transfiguration”.

Conclusions

Genius and disease are completely distinct. There are people considered a genius but not ill, while there are people who may be ill but not considered a genius. Moreover, frequently, a genius is found to present symptoms of mental disorders. Maybe a genius should be evaluated, in his everyday expressions, using a special measuring device, a device which is not that used to assess the intelligence of ordinary people. The most intriguing question and difficult to answer, is how much does the psychic or organic disorder influence the artistic production of the genius. Certainly, there is some influence, being greater in the case of neurosis than in that of organic disease, since the psychic disorder is closely correlated with the expressive faculty of the Author. The disease conditions the behaviour of the individual: the writer tends to transfer, in his work, the manifestations of the uneasiness which affects him and to present these through a description of his characters.

There are also Authors who are able to produce extraordinary synthesis, between type of diseases and behavioural characteristics of the persons described, the fruit of a very close association between culture and geniality. Human passions and life’s dramas are treated with authentic art which cannot be imitated. Chekhov is an example.

We make every effort to interpret, understand, penetrate, if possible, into the meanders of the tormented brain of the genius in the attempt to grasp the significance of a life that has lived in other spheres, at higher levels of suffering and who, after all, has attempted with his works to transmit to us his sense of solitude and desperation. For this, we admire the genius and, at the same time, we enrich our baggage of humanity.

References

- 1.Brod M. Franz Kafka. Prague; 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hackermüller R. Das Leben, das Mickstörd. Vienna; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinelli Seltzer L. Kafka: introduzione all’opera. In: Wege zur deutschen Literatur – neu. Florence: Bulgarini-Innocenti; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montani L. Kafka e la malattia come significante. In: Il corpo e il testo. Psychomedia (Home page Italiana), Arte e Rappresentazione, Letteratura. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skopec M, Majer EH. History of ORL in Austria. Vienna: Brandstätter; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterpellone L. Franz Kafka. In: Pazienti illustrissimi … Rome: Delfino Ed.; 1985. [Google Scholar]